The Project Gutenberg EBook of Napoleon's Young Neighbor, by Helen Leah Reed This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Napoleon's Young Neighbor Author: Helen Leah Reed Release Date: January 22, 2011 [EBook #35037] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NAPOLEON'S YOUNG NEIGHBOR *** Produced by Heather Clark, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

This book, chronicling some little known passages in the last few years of Napoleon, is based on the "Recollections of Napoleon at St. Helena," by Mrs. Abell (Elizabeth Balcombe), published in 1844 by John Murray.

Her little book is written in an old-fashioned and quiet style, and the present writer, without altering any words of Napoleon's, has, so far as possible, given a vivid form to conversations and incidents related undramatically and has rearranged incidents that Mrs. Abell told without great attention to chronology. The writer has also added many pages of matter (with close reference to the best authorities) in order to make the whole story of Napoleon clear to those who are not familiar with it.

PREFACE

CHAPTER I. Great News

CHAPTER II. A Distinguished Tenant

CHAPTER III. From Waterloo to St. Helena

CHAPTER IV. Napoleon at The Briars

CHAPTER V. Betsy's Ball-Gown

CHAPTER VI. A Horse Tamer

CHAPTER VII. Off for Longwood

CHAPTER VIII. The Governor's Rules

CHAPTER IX. All Kinds of Fun

CHAPTER X. The Serious Side

CHAPTER XI. The Emperor's Visitors

CHAPTER XII. Thoughtless Betsy

CHAPTER XIII. Longwood Days

CHAPTER XIV. The Parting

CHAPTER XV. The Panorama

CHAPTER XVI. The Last Pictures

BOOKS BY HELEN LEAH REED

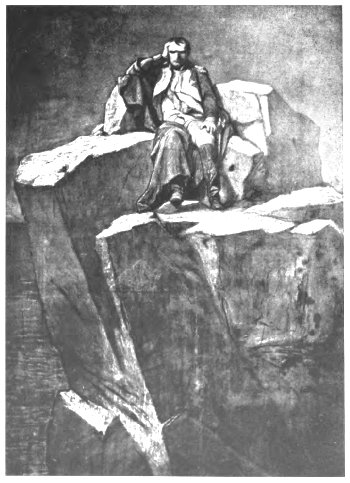

The Embarkation on Board the Bellerophon

Far south in the Atlantic there is an island that at first sight from the deck of a ship seems little more than a great rock. In shape it is oblong, with perpendicular sides several hundred feet high. It is called St. Helena because the Portuguese, who discovered it in 1502, came upon it on the birthday of St. Helena, Constantine's mother. To describe it as the geographies might, we may say that it lies in latitude 15° 55' South, and in longitude 5° 46' West. It is about ten and a half miles long, six and three-quarters miles broad, and its circumference is about twenty-eight miles. The nearest land is Ascension Island, about six hundred miles away, and St. Helena is eleven hundred miles from the Cape of Good Hope.

From the sea St. Helena is gloomy and forbidding. Masses of volcanic rock, with sharp and jagged peaks, tower up above the coast, an iron girdle barring all access to the interior. A hundred years ago its sides were without foliage or verdure and its few points of landing bristled with cannon. Jamestown, the only town, named for the Duke of York, lies in a narrow valley, the bottom of a deep ravine. Precipices overhang it on every side; the one on the left, rising directly from the sea, is known as Rupert's Hill, that on the right as Ladder Hill. A steep and narrow path cuts along the former, and a really good road winds zigzag along the other to the Governor's House. Opposite the town is James's Bay, the principal anchorage, where the largest ships are perfectly safe.

The town really consists of a small street along the beach, called the Marina, which extends about three hundred yards to a spot where it branches off into two narrower roads, one of which is now called Napoleon Street. In 1815 there were about one hundred and sixty houses, chiefly of stone cemented with mud, for lime is scarce on the island. Among its larger buildings were a church, a botanical garden, a tavern, barracks, and, high on the left, the castle, the Governor's town residence.

About a mile and a half from the town there stood in the early part of the past century a cottage built in the style of an Indian bungalow. It was placed rather low, with rooms mainly on one floor. A fine avenue of banyan trees led up to the house, and around it were tall evergreens and laces, pomegranates and myrtles, and other tropical trees. Better than these, however, in the eyes of the dwellers at The Briars were the great white-rose bushes, like the sweetbriar of old England. From these the house took its name, and thus the family in it seemed less far away from their old home.

In a grove near the house were trees of every description, grapes of all kinds and citron, orange, shaddoc, guava, and mango trees in the greatest abundance. The surplus raised in the garden beyond what the family could use brought its owner several hundred pounds a year. The little cottage was shut in on one side by a hedge of aloes and prickly pear and on the other by high cliffs and precipices. From one of these cliffs, not far from the house, fell a waterfall, not only beautiful to the eye but on a hot day refreshing to the mind with its cool splash and tinkle.

The owner of The Briars at this time was an Englishman named Balcombe, who was in the service of the government. Besides his servants his household consisted of his wife, his daughters Jane and Betsy, in their early teens, and two little boys much younger. They formed a happy, contented household, living a simple, quiet life, and though the parents were sometimes homesick, the children were very fond of their island abode.

One evening in the middle of October, 1815, the Balcombe children were having a merry time with their parents, when a servant, entering, announced the arrival of two visitors.

"It is the captain of the Icarus," said Mr. Balcombe, turning to his wife, "and another naval officer."

"The man-of-war that came in to-day?" asked one of the children. "We heard the alarm sound from Ladder Hill."

"Yes, yes, my dear." Then, turning to a servant, "Show them in."

As the gentlemen entered the room, it was plain that they had something of importance to communicate.

"Sir," said the senior officer to Mr. Balcombe, after the first greetings, "I come to tell you that the Icarus is sent ahead of the Northumberland to announce that the Northumberland is but a few days' sail from St. Helena."

"Yes," responded Mr. Balcombe politely, wondering why this announcement should be made so seriously.

"Sir George Cockburn," continued the other, "commands the Northumberland, and in his care is Napoleon Bonaparte, whom he brings to St. Helena as a prisoner of state."

Mr. Balcombe started to speak; his expression was one of annoyance. He was not fond of practical jokes. His wife leaned back in her chair, gazing incredulously at the speaker. The children laughed. The officer's story was too absurd. Then one of the little boys began to cry. In their play the older children were in the habit of frightening the others with the name of Napoleon Bonaparte. It was alarming to hear that the terrible Napoleon was to come to live on their peaceful island.

Before Mr. Balcombe could express his surprise, the officer repeated:

"Yes, Napoleon Bonaparte, the enemy of England."

"But how can that be?" asked Mr. Balcombe, hardly understanding. "Bonaparte was on Elba months ago; what has England to do with him now?"

"Surely—" began the captain; then recalling himself, "but I forgot how far St. Helena is from the rest of the world. After Napoleon escaped from Elba in February, he gathered a great army. But the Allies, with our Iron Duke at the head, met him near Brussels, and there in June was fought the great battle of Waterloo. Thousands were killed, brave English as well as French. That battle marked the downfall of Napoleon, and soon he was England's prisoner."

Mr. and Mrs. Balcombe, as well as their children, listened eagerly, absorbed in a story they now heard for the first time.

"So they send him here?" It was Mr. Balcombe who first spoke.

"Yes; no spot in Europe can hold him. Even on Elba he had begun to establish a kingdom. He reached beyond that little island, and now he has had his Waterloo."

"It is clear, then," said Mr. Balcombe, "why they have sent him here. This is a natural fortress and it belongs to England."

"Yes," said the officer; "England knows that here, in her keeping, Bonaparte will never again escape to torment the world."

After a few more words of explanation on the one hand and of surprise on the other, the visitors withdrew.

Of those who had listened to the officer young Elizabeth, or Betsy as she was commonly called, was the most disturbed. She shivered and turned pale, and her mother, noticing her agitation, soon sent her to bed. There she silently wept herself to sleep and her dreams were filled with visions of that dreadful ogre, Bonaparte. It was not a very long time since she had really believed Napoleon to be a huge monster, a kind of Polyphemus with one large, flaming eye in the middle of his forehead and with long teeth protruding from his mouth, with which he devoured bad little girls.

Although Betsy had outgrown this first idea of Napoleon, implanted in her young brain by careless servants, she was still afraid of the Conqueror. It is true that she realized he was not an ogre, but a human being; that is to say, the very worst human being that had ever lived. She knew this must be so, for she had heard sensible grown-up persons speak of him in this way, even her own father and mother. What wonder, then, that her dreams should be disturbed by thoughts of the misery that must come to St. Helena with such a man as Napoleon living on the island?

The next morning after the visit of the officer from the Icarus, the little girl rose early. She was far from cheerful as she looked about her on the lovely garden and grove. A wave of hot anger passed over her. Why should that terrible man be permitted to land and destroy all this beauty, as he would, of course, on the first opportunity?

From the garden she looked toward the rugged mountain, known as Peak's Hill, which shut off the valley from the south. Her father had spoken of the island as a natural fortress. Except for the mountains the Government would never have thought of sending the dreadful Napoleon to St. Helena. So she hated the mountains and cliffs.

Perhaps, however, even at that moment when she dreaded the coming of the exiled Emperor, Betsy may have recalled her own first impressions of St. Helena and cast a half-pitying thought toward the great man who now saw in its rocky heights only his prison wall.

One day Betsy's mother had reminded the young girl of the bitter tears she shed when she had first seen the island.

"You were a silly girl to cry when you first came in sight of land," said her mother, recalling the circumstance.

"Yes, but some had told me that the island was really the head of a great negro that was only waiting for the breakfast bell; then it would devour me first, and later the rest of the passengers and crew."

"Well, I am glad you told me your fears."

"So am I, for you showed me that these things could not be true."

"Yet I remember," responded Betsy's mother, "that you would not take your head from my lap until eight bells had sounded. For some reason the nearness of breakfast made you believe that danger was over."

"But you can't say that I made much fuss when I really was in the power of a negro," rejoined Betsy; "for I can well remember how strange it seemed when I was lifted in a basket, and told that a big negro was to carry me out to The Briars. At first I was a little frightened, for I had never seen a black man before, but he spoke so pleasantly when he put me down to rest, even though grinning from ear to ear, that I decided he would not harm me."

"You saw at once that he was good natured."

"Yes, and he asked me so kindly if I were comfortable in my little nest, that I trusted him. I was as proud as a peacock when he said he was honored in being allowed to carry me, because usually he had nothing but vegetables in his basket. When we reached The Briars I told father I had had a delightful ride, and so he gave the negro a little present that made him grin more than ever, and he went off singing merrily at the top of his voice."

Thus Betsy recalled her first impression of St. Helena.

If Mr. Balcombe and the rest of the family at The Briars were surprised at the news of Napoleon's approach, people on the island in general were equally astonished. No communication had reached Governor Wilks, no letter of instructions as to what should be done with the illustrious prisoner.

The captain of the Icarus could only tell the residents of St. Helena that Napoleon was near and that the Second Battalion of the Fifty-third Regiment had embarked with the squadron. Even in those days, when there were no cables to flash the news of coming events, when there were no swift steamboats to act as heralds, it seems strange that in more than seven months no news of the escape from Elba had reached the little island.

Now, when the people of St. Helena heard the news, they were greatly disturbed. They were afraid that the coming of Napoleon might cause changes in their government, and they were so fond of the Governor that they did not wish to lose him.

Their fears were well grounded, for when Sir George Cockburn landed it was found that he had received an appointment that gave him the chief civil and military power on the island, while Governor Wilks took secondary rank. Later it was learned that on account of the distinction of the prisoner, a governor of higher rank than Colonel Wilks would be sent from England to supersede him, a governor who held his appointment directly from the Crown.

Two or three days after the visit of the officer to The Briars, Betsy and her brothers and sister were in a state of great excitement.

"Ah, I hope papa will not be killed," cried little Alexander.

"How silly you are!" responded the older Jane. "Why should he be killed?"

"Because Napoleon is such a monster. If he should suddenly take out his sword—"

"Yes, or open his mouth and swallow papa, how terrible it would be!" added Betsy mockingly.

"Of course Bonaparte is a monster, but he would never dare hurt any one on this island, especially an Englishman. Don't worry. Papa will come home safely enough, but I wish he would hurry, so we could hear all about the wretch."

Later in the day the children gathered eagerly around their father, who had returned from his visit to the ships.

"Oh, papa, what was he like?" asked each in turn.

"Who, Napoleon?"

"Of course. We wish to hear about him. Didn't you see him? Didn't you see anybody there?"

"I could hardly visit a fleet without seeing some one."

"Is it a large fleet?"

"Yes, it would be called large in any part of the world."

"How large is it?"

"Besides the Northumberland there are several other men-of-war, and the transports with the Fifty-third Regiment."

"But did you see Napoleon?" asked one of the children, returning to the subject of greatest interest.

"I did not see General Bonaparte," replied the father, pausing to see the effect of his words on the children. Then, as he noted their expression of disappointment, he quickly added: "But I saw some of the others,—some of his suite."

"Oh, tell us about it!"

"There is little to tell. After paying my respects to Sir George Cockburn, I was introduced to Madame Bertrand and Madame Montholon, and then to the rest of Napoleon's suite."

"What were they like?" asked one of the girls eagerly, as if she expected her father to describe a group of strange beings.

"Like any travellers, my child, who had had a long voyage, from the effects of which they were anxious to rest."

"Oh, I wish you had seen Napoleon!"

"I am likely to see him soon, and you may, also, as he is to land to-night."

At this news the children were silent. To have Napoleon on the island was not a pleasant prospect. They were not so sure now that they cared to see him.

"But where will he live, papa, when he comes ashore?" ventured Jane at last. "Will they put him in a dungeon?"

"Certainly not, my child. He is to live at Longwood, but as the house needs to be put in repair, he will stay for a while with Mr. Porteous."

"When will he come ashore?" asked Betsy timidly. Now that her father had spoken so reassuringly of Napoleon, she was curious to see him, at least from a safe distance.

"He will land to-night,—after dark, I imagine, to escape the gaze of the crowd;" and their father, turning from the children, went toward the house.

As he left them, the young people began an animated discussion of Napoleon. They were already getting used to the idea that he was to live on St. Helena and that he was an ordinary human being, not unlike the British officials of high rank sent out by the Crown.

"As he cannot possibly hurt us, why shouldn't we go to the valley to see him land?" asked Betsy.

"Why shouldn't we?" echoed Jane. So it happened, when they had asked their parents, that the older children were permitted to go to Jamestown to see Napoleon land. When they reached the wharf it was dusk and crowds of people were gathered on every side.

"I did not know there were so many people on the island," whispered Betsy, as she pressed closer to her sister. "Do you suppose he will be in the first boat?"

"I don't know. But see, it is coming!"

"Yes, little ladies," said a bystander, "Bonaparte will surely be in the first boat."

"Here it is, here it is," cried Betsy. "Look, Jane, look!"

Even as she spoke, the passengers from the longboat were coming ashore, and although it was seven o'clock in the evening, there was still enough light to enable the watchers to see the figures of those who were landing.

The girls strained their eyes. Three men marched slowly up from the ship's boat. "See," cried Betsy, "probably Napoleon is in the middle."

"That little man, and in an overcoat!"

"Yes, for there is something flashing, probably a diamond."

"A man with a diamond! How foolish!" objected Jane.

"But it is, indeed it is!"

"I wish people wouldn't crowd so."

"They've got to move back. I'm glad of it. The sentries are standing with fixed bayonets to keep more people from rushing down from the town."

If Napoleon had landed earlier in the day, he would have been greeted by an even greater crowd, for people had been gathering on the Marina from the earliest hours; but disappointed that he was not to land until after sunset, most of them had gone home. Still, however, a large enough crowd had gathered to make it necessary for the sentries to use some force to keep them in order.

In spite of the crowd, the sisters felt that they had been rewarded for their trouble, for when they reached home they learned that the little man in the green coat was indeed the dreaded monster.

The next morning Betsy rose early. The night before the family had sat up later than their custom, talking about the arrival of the ship and the distinguished prisoners.

"Are General Bertrand and Count Montholon prisoners too?" asked one of the girls.

"No, my dear; I understand that they are at liberty to leave St. Helena whenever they wish. Of course while they are here they must obey whatever rules are made for them, but they would not be here if they had not chosen to share the fate of Napoleon."

"That is very noble," said Jane, "to leave one's home for the sake of such a man as Napoleon;" and the conversation changed into a discussion of the reasons that had induced those Frenchmen to follow their leader. The next morning Betsy awoke feeling that something unusual had happened.

Her little brothers plied her and Jane with questions about the landing of the Frenchmen.

"I wish we lived close to the town," complained Alexander, "that we might hear more about Napoleon."

"Look, look!" cried Betsy, before the little fellow had finished speaking. "What is that on the side of the mountain?"

Following the direction of her finger, the other children broke into excited cries. "The French, it must be the French! There are horses with men on them. There, see the swords flash! They must be guarding a prisoner."

"Oh, I suppose it is a prisoner. But what is that white thing?"

"It is a plume; you can see that for yourself. Let us get a spyglass."

For some time the children watched the little procession curving around the mountain-side, high above them.

"It makes me think of a great serpent winding along," said Betsy.

"It doesn't look like a serpent, through the glass. There are five men on horseback. One of them has a cocked hat. It must be Napoleon, though he wears no greatcoat."

"They're going to Longwood. That's what it is. Papa says he's to live there. I wonder how he'll like it after all his palaces in Europe."

"I'm glad he won't live near us. I should never dare leave the house, if he lived near."

"Who's he?"

"Napoleon, of course."

The morning passed. The children thought of little but Napoleon. They talked to each other of his victories and were proud that Englishmen had overthrown him.

Early in the afternoon two gentlemen called, Dr. Warden of the Northumberland and Dr. O'Meara of the garrison.

"Oh, have you seen him?"

"Seen whom?"

"Why, Napoleon; don't tease us,—Napoleon Bonaparte."

"Well, then, since you are so curious, yes, we have seen him." Dr. Warden smiled, for he was surgeon of the ship that had brought Napoleon.

"Oh, was he perfectly awful? Weren't you frightened?"

"If we were frightened, I tried not to show it. Napoleon seemed harmless. He did not even try to bayonet us," replied Dr. O'Meara.

"But how did he look?"

"He hadn't horns or hoofs; at least, we didn't see them, and on the whole he was charming, though he seemed tired. You girls will like him."

"Oh, no!" cried Betsy. "I shake and shiver whenever I think of him. If ever I look at him it will be only at a distance, but I could never, never speak to him."

"Mark my words, you will change your mind, Miss Betsy," cried one of the two as he turned away.

About four o'clock that same afternoon, when it was approaching dusk in the little valley, one of the children reported that the same horsemen they had seen in the morning were again winding around the mountain.

Soon the whole family gathered outside, and as they looked, to their great astonishment they observed the procession halt at the mountain pass above the house, and then, after a few minutes' pause, begin to descend the mountain toward the cottage.

"Oh, mamma, do you suppose they are coming here? I must go and hide myself," cried the excitable Betsy.

"No, my dear, you will do nothing of the kind. I am surprised that a great girl should be so foolish."

"But Napoleon is coming, don't you understand, Napoleon. I could not bear to look at him."

"You will look at him and speak to him, if he comes here. It will be a good chance for you to put your French to use."

Poor Betsy! Up to this time she had been proud of the French acquired during a visit to England a few years before, which she had conscientiously kept up by conversation with a French servant.

It seemed hard that she was now to be called on to do a disagreeable thing just because of this accomplishment. Of course she could not disobey her mother, and in spite of her fright she really had some curiosity to see the distinguished guest.

Not long after the party first came in sight, the French and their escort were at the gate of The Briars. As there was no carriage road to the house, all, except Napoleon, got off their horses. He rode over the grass, while his horse's feet cut into the turf. His horse was jet black, with arched neck, and as he pranced along he seemed to feel conscious of his own importance in carrying so distinguished a man as the Emperor.

"He's handsome," whispered Jane to Betsy.

"The horse?"

"No, Napoleon; just look at those jewels and ribbons on his coat—and I never saw so beautiful a saddlecloth. It is embroidered with gold."

Before more could be said, Mr. and Mrs. Balcombe were moving forward to meet Sir George Cockburn and his distinguished companion. The sisters closely followed their parents, and after the older people had been presented to Napoleon the turn of the girls came. Betsy, looking up, was impressed by the charm of Napoleon's smile. She saw that his hair was brown and silky fine; his eyes were a brilliant hazel. She also noticed one slight defect,—that his even teeth were dark, the result, she afterwards learned, of his habit of using much licorice.

The children at first were surprised to find Napoleon neither as tall nor as impressive as he had appeared on horseback. When they looked in his face they decided that he was very attractive, and when he spoke his smile and kindly manner at once won their hearts. From that moment Betsy forgot that she had ever considered him an ogre. To herself she called him the handsomest man she had ever seen.

"This is a most beautiful situation," he said to Betsy's mother. "One could be almost happy here!" he added with a sigh.

"Then perhaps you will honor us with a visit until Longwood is ready," interposed Mr. Balcombe. "I understand that you prefer this to the town, and I have already put some rooms at Sir George Cockburn's disposal."

"I do prefer it."

"Then the rooms are at your service."

Strange language this to a prisoner,—the children may have thought as they listened,—to give him a choice of abode. Later they learned why their father had put the matter in this way. They heard how wretched it made the Emperor to think of returning to the small house where he had lodged in the town and where people stared into the windows, as if he were some kind of wild animal. When he found that Longwood would not be ready for him for several weeks, he had at once declared his unwillingness to return to Jamestown. The glimpse of The Briars that he had had from a distance pleased him greatly, and he had asked if it might not be possible to lodge him there. Mr. Balcombe, as an official of the Government, having placed some rooms at the disposal of the Admiral, Sir George Cockburn, was now anxious to put Napoleon at his ease about occupying them.

The Balcombe children were greatly stirred up when they found that Napoleon was to be their neighbor, for the rooms to be assigned him were near, but not in, the main house. Their fear of the Emperor had almost wholly disappeared.

Continuing to praise the view, Napoleon asked that some chairs be brought out on the lawn.

"Come, Mademoiselle," he said to Betsy in French, "sit by me and talk. You speak French?"

"Yes, sir," replied Betsy with apparent calmness, though her heart was beating violently.

"Who taught you?"

"I learned in England, when I was at school."

"That is well, and what else did you study? Geography, I hope."

"Yes, sir."

"Then you can tell me what is the capital of France?"

"Paris, monsieur."

"Of Italy?"

"Rome."

"Of Russia?"

"St. Petersburg."

He looked up quickly. "St. Petersburg now; it was Moscow."

Then he asked, sternly and abruptly, "Qui l'a brulé?" ["Who burned it?"]

Betsy trembled. There was something terrifying now in his expression, as well as in the tones of his voice. She could not find words to reply as she recalled what she had heard about the burning of the great Russian city and the question as to whether the French or the Russians had set it on fire.

"Qui l'a brulé?" repeated Napoleon.

But there was a twinkle in his eye and a smile in his voice that encouraged Betsy to venture a stammering "I don't know, sir."

"Oui, oui," he responded, laughing heartily. "Vous savez très bien. C'est moi qui l'a brulé." ["Yes, yes, you understand well. It is I who burned it."]

Then Betsy ventured further:

"I believe, sir, the Russians burned it to get rid of the French."

Again Napoleon laughed and, instead of being angry, seemed pleased that the little girl knew something about the Russian campaign.

Now while Napoleon was sitting in the garden or walking about the beautiful grounds, all was confusion and excitement within The Briars. Betsy's mother, like any other good English housewife, was naturally somewhat taken aback at having suddenly to make plans to entertain Napoleon and part of his suite. Even though the English Government might pay for his board, she must still regard him as her guest, and in the small time at her disposal do all that she could to make him comfortable.

Rooms, therefore, must be rearranged and what furniture could be spared from the rest of the house must be put into Napoleon's apartments. So, in the short space of a few hours, the dreaded Emperor of the French, the ogre feared by the children, had become the neighbor, almost the inmate of a happy English household—English, in spite of its distance, many thousands of miles away, from the islands of Great Britain.

It was evening when Napoleon came back to the house with the family. Here again his conversation was chiefly with Betsy, as her fluent French pleased him. Her parents could use the language only with difficulty.

"Do you like music?"

"Yes, sir."

"But I suppose that you are too young to play."

This rather piqued Betsy.

"I can both sing and play."

"Then sing to me."

Thereupon Betsy, seating herself at the little harpsichord, sang in a sweet, full voice "Ye Banks and Braes."

"That is the prettiest English air I have ever heard."

"It is a Scotch air," said Betsy timidly.

"I thought it too pretty to be English. Their music is vile,—the worst in the world. Do you know any French songs? Ah, I wish you could sing Vive Henri Quatre."

"No, sir; I know no French songs."

Upon this the Emperor began to hum the air, and in a fit of abstraction, rising from his chair, marched around the room, keeping time to the tune he was singing.

"Now what do you think of that, Miss Betsy?" he asked abruptly. Betsy hesitated between her love of truth and her desire to please the Emperor.

"I do not think I like it," she said at last, rather gently. "I cannot make out the air."

She might also have added that the great Emperor's voice was far from musical. Neither then nor at other times when he tried to sing could she tell just what tune he thought he was rendering.

When he discussed music she understood him better and she saw that he was a good critic. "French music," he said, "is almost as bad as English. Only Italians know how to produce an opera properly;" and he sighed heavily, remembering perhaps that his own opera days were over.

Not long after Betsy had finished "Ye Banks and Braes," word was brought to Napoleon that his rooms were ready, and with a kindly word or two he bade good night to his young friend.

The little girl's dreams that night were, we can well imagine, quite unlike any she had ever had before. But if she dreamed of the Emperor it is certain that she did not regard him as an ogre. His wonderful personality had gained her heart. Henceforth she was to be his loyal friend as well as his neighbor.

The events that ended in the voyage of the fallen Emperor to St. Helena, if told in full, would make a long story. The battle of Waterloo, however, is a good starting place, the battle that decided the peace of Europe after its long years of war, when the Allied Powers, led by the Duke of Wellington, defeated the French, who had rallied around Napoleon for a last stand.

Napoleon, when he saw that the day was lost for him and the French, fought desperately, hoping perhaps to meet death. But he seemed to have a charmed life, and, though he plunged into the thick of the fight, he was not even wounded.

Some of his friends advised him to continue the struggle, but he saw that this might mean civil war for France as well as a long contest against the Allies. He cared too much for France to drag her into further wars. Some say that in giving up he could not help himself,—that what he did he had to do. Be that as it may, for a second time he signed the Act of Abdication, and after proclaiming his son Napoleon II, he left Paris. First he went to Malmaison, once the beautiful home of Josephine, where a few friends joined him.

When the Allies were approaching Paris, Napoleon offered his services to the Provisional Government, promising to retire when the enemy was driven away. But the men now at the head of affairs at Paris were afraid to give authority of any kind to Napoleon, even for a limited time. He had broken one promise, he might break another, and they refused his offer.

Napoleon now thought of America. Certain Americans in Paris had offered him help. One shipping merchant, a Massachusetts man, had an excellent plan, which, had Napoleon followed it, might have resulted in his reaching America safely. But Napoleon delayed, and although he did not know it at the time, when he left Malmaison for Rochefort on June 29 he was too late. Up to the last he hoped to reach a vessel that would carry him safely to the United States. It is said that he gave up the plan proposed by the American shipping merchant because he would not desert his friends, and for the time there seemed to be no way of providing for them.

It takes strength of mind for a man to decide to live out his destiny rather than run away from life. Napoleon now decided to make the best of things. With British ships practically blockading the coast, he saw that to try to escape was hopeless. He heard with dismay that Paris had surrendered to the Allies, and that the Provisional Government, that might have helped him, had dissolved. His last effort was to suggest sending a flag of truce by Generals Savary and Las Cases to Captain Maitland, commander of the British squadron, asking to be allowed to pass out of the harbor. He gave his word of honor that he would then go directly to America. Captain Maitland replied that even if he himself could grant this request, Napoleon's vessel would be attacked as soon as it had left the harbor. Napoleon at last had to admit that the end had come when the report was brought him that Louis XVIII was again seated on the throne of France. He therefore again sent two officers to Captain Maitland, offering to surrender on condition that no harm should come to his person or property. Another condition was that he should be allowed to live where he pleased in England as a private individual. The officer replied that he could not make terms, but that he would probably take Napoleon and his suite to England as soon as he should receive word from the Prince Regent. This answer was disappointing to Napoleon, but there was nothing now for him to do except to set out for the Bellerophon, Captain Maitland's ship, with the flag of truce.

"I come to claim the protection of your prince and your laws," he said in French, as he advanced on the quarter-deck to meet Captain Maitland.

Soon after this he wrote the following letter in French to the Prince Regent:

Royal Highness:

Exposed to the factions which divide my country and to the enmity of the great Powers of Europe, I have terminated my political career, and I come like Themistocles to throw myself on the hospitality of the British nation. I place myself under the safeguard of their laws and claim protection of your Royal Highness, the most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous of my enemies.

Napoleon.

It is not to be supposed that all this time Napoleon's friends were indifferent to his fate. Those who were near enough to communicate with him made various suggestions.

At Rochefort his brother Joseph offered to disguise himself and change places with him, so that the Emperor might get away in the same vessel in which he himself was preparing to escape. Had Napoleon agreed to this plan, he would probably have been as successful as Joseph in reaching America.

Some young and brave French officers are said to have offered themselves as the crew of a rowing boat to carry Napoleon safely through the blockading fleet. There would have been some risk in carrying out this proposal of stealing through the blockade, but it had a fair chance of success.

There were also swift neutral vessels not far away, on more than one of which he had friends. But although, with three of his suite, he did embark on a Danish ship, on second thoughts he decided not to venture farther, and returned to shore. He might have accepted the suggestion of the captain of a French frigate then at the Ile d'Aix, who begged Napoleon to take the chance of intrusting himself to him. He would, he said, attack a British ship near by, and while the attention of other vessels was fixed on the encounter, a second French frigate with Napoleon on board would carry him far outside the harbor to safety. But this offer, too, was put aside. The admirers of Napoleon, who look back on his days of indecision at Rochefort, wonder at the change in the man, who by his policy of delay brought on himself his sad exile on the barren island.

Yet it is easy to see that even though half willing to try flight, Napoleon really could not bring himself to the position of a fugitive, afraid to face his enemies. It was nobler to confront danger, as he had confronted it often on the battlefield. It was not strange that he should hope to find appreciation of his courage, even in the hearts of his enemies.

It was the fifteenth of July when Napoleon embarked on the Bellerophon, and a week afterwards he was in Plymouth Harbor. Too late, to his great consternation, he found that the British regarded him as a prisoner. He was helpless; he had no weapons but words, for armed vessels surrounded him and the few friends who followed him counted for nothing against his foes.

On the thirtieth of July, General Bonaparte—the British refused him the title of Emperor—was notified that the British Government had chosen St. Helena as his future residence, whither a limited number of his friends might accompany him. On receiving this word, Napoleon's indignation was loudly expressed. He replied, that he was not the prisoner, but the guest of England, and that it was an outrage against him to condemn him to exile into which he would not willingly go. It was at once evident, however, that, willing or unwilling, he must embark for his distant prison. From Plymouth he was taken to Torbay, where, on the eleventh of August, the Bellerophon met the Northumberland, on which the illustrious prisoner was to be taken to St. Helena.

When Napoleon received Lord Keith and Sir George Cockburn on the deck of the Bellerophon he wore a green coat with red facings, epaulets, white waistcoat and breeches, silk stockings, the star of the Legion of Honor, and a chapeau gris with the tricolored cockade. At first the Emperor spoke bitterly of the action of the British Government, but at last he abruptly asked Lord Keith for his advice. The latter replied it would be best for Napoleon to submit with good grace. Napoleon then agreed to go on board the Northumberland at ten the next morning. Later he recalled his consent and again talked bitterly of his fate, but at last he controlled himself and agreed to submit.

The next day, after all the stores and provisions and the personal belongings of Napoleon and his suite were on board, the Northumberland, with its distinguished prisoner, set sail for St. Helena.

With Napoleon went a fairly large suite, consisting of the following persons:

Grand Mareschal Comte de Bertrand, Madame de Bertrand and three children, one woman servant and her child, one man servant; General Comte de Montholon, Madame de Montholon and a child, one woman servant; Comte de las Cases and his son of thirteen; General Gorgaud; three valets de chambre and three footmen, a cook, a lampiste, an usher, a steward, chef d'office.

Among the things that made up the rather large store of baggage that Napoleon took with him to St. Helena, besides his clothing and more personal belongings, were two table services of silver, a number of articles of gold, a beautiful toilet service of silver, including water basin and ewer, cases of books, and his special beds. Although money could do little for him in his new home, since all his expenses would be met by the British Government, it is known that he had with him a large amount of money.

It is useless now to discuss what would have been the result had his enemies been kinder to Napoleon. If he had been permitted to settle down in England as he wished, as a country gentleman, would this have satisfied him? Even if he had made no attempt to recover the throne of France for himself, might he not have put forth efforts to have his son acknowledged Emperor? At the time of his father's downfall, the little King of Rome was hardly more than a baby, but as years passed on he could never have lived contentedly with his grandfather, the Austrian Emperor, knowing that his father was as near as England. In the name of the young Napoleon, Europe might again have been plunged into a great war.

Yet, without looking toward the future, Great Britain was only too sure that the time had come to punish one who had always been the avowed enemy of England. It is true that England had suffered less than any other of the Powers at the hands of Napoleon, because he had never invaded her territory, but in no country was Napoleon so hated. Thousands of Englishmen had shed their blood in the wars carried on against him by the Allies, and by the mass of the English people he was regarded as a monster. Although the so-called Napoleonic wars had their origin in causes that Napoleon could not have controlled, he was regarded as the one being responsible for the twenty years' upheaval in Europe.

When it was announced that the British Cabinet had decided to send him into exile, many, perhaps the majority, thought the punishment too light. They would have had him treated as a rebel and immediately hanged or beheaded. Yet while the mass of the English people hated Napoleon, Englishmen who had ever met him were apt to be his firm friends, or at least his admirers.

Captain Maitland, of the Bellerophon, said that he had inquiries made of the crew as to their opinion of him, and this was the result: "They may abuse that man as much as they please, but if the people of England knew him as well as we do, they would not touch a hair of his head."

Though Napoleon had surrendered to Great Britain alone, the Allied Powers, desiring Great Britain to be responsible for him, approved her course.

During the voyage of ten weeks toward St. Helena, Napoleon suffered little from sea-sickness after the first few days. He breakfasted in his own cabin at ten or eleven o'clock. Before he dined he generally played a game of chess, and remained at dinner, in compliment to the Admiral, about an hour. After he had his coffee he left the others to walk with Count Bertrand or Count Las Cases on the quarter-deck. He often spoke to those officers who could understand French. At first he showed little interest in the occupations of those about him, but in time he engaged in more general conversation and was especially inclined to talk to Mr. Warden, the Northumberland surgeon, about the prevailing complaints on board the ship and his methods of treating the sick. After a while he turned to his own books and spent most of the day reading or in dictating to Las Cases. On the twenty-third of August the Northumberland crossed the equator. Before this the Admiral had amused himself trying to frighten the French, telling them of the rough ceremony practised by the sailors, who always undertook to present to Neptune all persons on board who had never before crossed the line. It happened, however, that in this instance all made a special effort to be courteous. While the sailors presented to Neptune were shaved with huge razors and a lather of pitch, the French were introduced politely with compliments, and the Emperor was treated especially well.

Napoleon seemed amused by this novel performance, and later he wished to have one hundred napoleons divided among the sailors. He was made, however, to feel his altered position when, after some discussion, the Admiral courteously but decidedly refused his request.

There were probably few on the Northumberland who did not deeply sympathize with the fallen Emperor. On this long, monotonous voyage, when his only amusements were conversation and an occasional evening game of whist with his friends, he seemed to be trying to make the best of the situation.

On the morning when the Northumberland approached St. Helena, the Emperor dressed early, and going up on deck stepped forward on the gangway. It was the fifteenth of October when the ship, after its long voyage, lay at anchor. The Emperor, standing on the gangway with Las Cases behind him, looked through his glass at the shore. Directly in front he saw a little village, surrounded by barren and naked hills, reaching toward the clouds. Wherever he looked, on every platform, at every aperture, on every hill, was a cannon. Las Cases, watching his face intently, could perceive no change of expression, for Napoleon now had full control of himself. Unmoved he could look on the island that was to be his prison, perhaps his grave. He did not stay long on deck, but, turning about, asked Las Cases to lead the way to his cabin. There they went on with their usual occupation, waiting until they should be told that the time for landing had come.

During the long voyage Napoleon had won the regard of most persons on the ship. The Northumberland was terribly crowded, but while others grumbled, he made no complaint of the great discomfort, although he, like the others, was affected by it. Already he had begun to practise that stoicism which, on the whole, was the keynote of his life at St. Helena.

Napoleon quickly fitted himself into his place in his new surroundings. So adaptable was he that the children soon ceased to regard him as a stranger, nor were they inclined to criticise his habits, although in most respects his ways were quite unlike those of the Balcombe family. For example, he did not breakfast as they did. After rising at eight o'clock, he satisfied himself with a cup of coffee and had his first hearty meal, breakfast or luncheon as they variously called it, at one. It was nine o'clock in the evening before he dined, and eleven when he withdrew to his own room.

The Pavilion, the building that chiefly formed his new abode, was a short distance from the main building of The Briars. It had one good room on the ground floor, and two garrets. Napoleon selected this Pavilion, not because it was really more convenient for him, but because by occupying it he would less disturb the Balcombe family than by taking quarters in the main house.

Las Cases and his son were in one of the garrets, and Napoleon's chief valet de chambre and others of his household were in the second. The rooms were so crowded that some of the party had to sleep on the floor of the little hall. The Pavilion had been built by Betsy's father as a ballroom, and had a certain stateliness. The large room opened on a lawn, neatly fenced around, and in the centre of the lawn was a marquee, connected with the house by a covered way. The marquee had two compartments. The inner one was Napoleon's bedroom, and in the other General Gorgaud slept. There was little but the beds in the marquee. General Gorgaud slept on a small tent bed with green silk hangings, which Napoleon had had with him in all his campaigns.

Between the two divisions of the marquee some of the servants of Napoleon had carved a huge crown in the green turf, on which the Emperor was obliged to step as he passed through.

At first Count Bertrand and Count Montholon with their families were lodged at Mr. Porteous's house in the town, where a suitable table was prepared for them in the French style. They could go to The Briars whenever they wished, accompanied by a British officer or Dr. O'Meara, who was appointed physician to Napoleon; or, followed by a soldier, they were permitted to visit any part of the island except the forts and batteries.

A captain of artillery resided at The Briars, and at first a sergeant and soldiers were also stationed there. But the presence of the soldiers was evidently needless, as well as so disagreeable to the family that, on hearing various remonstrances, Sir George Cockburn ordered them away.

But for the presence of the artillery officer, Napoleon during his stay at The Briars might almost have forgotten that he was a prisoner. He and his suite appreciated the unfailing kindness of Mr. Balcombe and his family, who from the first left nothing undone for the comfort of the exiles. During the early days of his stay the dinner for the French people at The Briars was sent out from town, but soon Mr. Balcombe fitted up a little kitchen, connected with the Pavilion, where Napoleon's accomplished cook had every opportunity to display his skill. Very often after dinner Napoleon obligingly went outside for a walk, that his attendants might finish their dinner in the room that he had left.

Soon after his arrival Napoleon was visited by Colonel Wilks, Governor of St. Helena, Mrs. Wilks, and other officials of the island, and some of the leading citizens and their families. He had not yet begun to seclude himself, and he and his companions seemed to be trying to make the best of their situation. Then and later evening parties were occasionally given by the French without much appearance of restraint. Napoleon accepted no invitations except those given by his friends at The Briars, and in one or two unusual cases, but the others went sometimes to the well-attended balls given by Sir George Cockburn.

Madames Bertrand and Montholon and the rest of Napoleon's suite, for whom there was not room at The Briars, often came to see him there, and remained during the day. To them he was still le grand empereur. His every look was watched, every wish was anticipated, and they showed him great reverence. Some have thought that in dealing with them he insisted too much on the etiquette of a court, but certainly none of the suite complained of formality.

Napoleon was always polite to guests at The Briars, and once went to a large party given by Mr. Balcombe, pleasing every one by his urbanity. When guests were introduced he always asked their profession, and then turned the conversation in that direction. People were always surprised at the extent of his information. Officers and others on the way from China sought introductions and were seldom refused.

Indeed in those first months his attitude to people was very different from what it was later. Not infrequently he himself invited people to dine with him.

Most of Napoleon's suite shared with him a feeling of friendliness for the Balcombe family. Las Cases, however, was always ready to criticise Miss Betsy, whose hoydenish ways he could never understand. One evening, when she was turning over the leaves of Estille's "Floriant," seeing that Gaston de Foix was called General, she asked Napoleon whether he was satisfied with him and whether he had escaped or was still living. This question shocked Las Cases, for it seemed to him extraordinary that a girl should imagine that the famous Gaston de Foix had been a general under Napoleon.

But this was not a very strange mistake for a little English girl to make. It is to be feared that Las Cases always took a certain pleasure in correcting the faults of the young Balcombes, or in reporting them to their parents.

From the first Napoleon claimed more of the society of Betsy than of the other members of the family, and so agreeable were his manners toward her that the little girl soon began to regard him as a companion of her own, with whom she could be perfectly at ease, rather than as one much older.

"His spirits were very good, and he was at times almost boyish in his love of mirth and glee, not unmixed sometimes with a tinge of malice," wrote Betsy years later.

"Jane," said Betsy to her sister, not long after Napoleon's arrival, "the Emperor has invited us to dine with him. What fun it will be!"

"I don't know. I am afraid it will be terribly solemn."

"Oh, no; I am not afraid of that. The Emperor isn't solemn. You ought to get acquainted with him, and you wouldn't think so."

Jane shook her head dubiously.

"I am half afraid of him. I don't see how you can dare to trifle so with him. What were you laughing at yesterday when Lucy was here? I thought the Emperor looked rather silly."

"Well, perhaps he did, if you put it that way," responded the blunt Betsy. "Only Lucy was sillier. I thought she would drag me to the ground when I told her the Emperor was coming across the lawn."

"Then why did you run and bring him up to her? I saw you do it."

"I needn't have done that. I did more harm than good. I told her he wasn't the cruel creature she thought him. But I oughtn't to have told the Emperor she was afraid of him. At least, I wouldn't have done so had I known how he would act, for he brushed up his hair so it stood out like a savage's, and when he came up to Lucy he gave a queer growl so that she screamed until mamma thought she might have hysterics and hurried her out into the house."

"It was ridiculous for a man to act like a child," responded the sedate Jane, who had not acquired Betsy's admiration for Napoleon.

"It was more ridiculous for her to scream. Napoleon laughed so at her that I had to take her part. 'I thought you a kind of an ogre, too,' I said, 'before I knew you.' 'Perhaps you think I couldn't frighten you now,' he answered, 'but see;' and then he brushed his hair up higher and made faces, and he looked so queer that I could only laugh at him. 'So I can't frighten you!' he said, and then he howled and howled, and at last seemed disappointed that I wasn't alarmed. 'It's a Cossack howl,' he explained, 'and ought to terrify you!' To tell you the truth, it was something terrible, but though I didn't like it I wouldn't flinch. Of course it was all in fun, for he is really very kind-hearted," concluded Betsy.

"All the same I don't enjoy the thought of having dinner with him," responded the practical Jane. "I've half a mind not to go."

"Oh, Jane, that would never do! What would the Emperor think? After you have been invited, too. Besides, mother wouldn't let you stay away. An invitation from royalty is a command."

"But Napoleon isn't—"

"Hush," cried Betsy, not wishing to hear her new friend belittled. She always took offence if any one called him prisoner.

In spite of her professed distaste for the dinner, Jane would have been disappointed had she been obliged to stay at home. She set out gayly enough, proud in her secret heart that she was to have the honor of being in the company of the great man.

Nine o'clock, Napoleon's dinner hour, was late for the little girls. As they entered his apartment the Emperor greeted them cordially, meeting them with extended hands, and a moment after, Cipriani, his maître d'hôtel, stood at the door.

"Le diner de votre Majesté est servi." Whereupon Napoleon, with a girl on each side, led the way after Cipriani, who walked backward, followed by the rest of his suite, who were dining with him.

Hardly had they taken their places when Napoleon began to quiz Betsy on the fondness of the English for "rosbif and plum pudding."

"It is better than eating frogs."

"Oh, my dear Mees, how you wrong us!"

"Ah, but see here!" cried Betsy, and she brought him a caricature of a long, lean Frenchman with his mouth open, his tongue out, and a frog on the tip of it, ready to jump down his throat. Under it was written, "A Frenchman's Dinner."

The Emperor laughed loudly at this. "You are impertinent," he cried, pinching Betsy's ear. "I must show this to the petit Las Cases. He will not love you so much for laughing at his countrymen."

Upon this Betsy turned very red. The Emperor had touched a vulnerable point. The young Las Cases, a boy of fourteen, was now at dinner with them, and Napoleon had found that he could easily tease Betsy about him.

"He will not want a wife," continued Napoleon, "who makes fun of him;" and Betsy, inwardly enraged, could only maintain a dignified silence.

The Emperor gazed intently at his young friend, and later, when they rose from the table, he called young Las Cases.

"Come, kiss her; this is your revenge."

Betsy looked about vainly for a means of escape. But the Emperor had already closed his hands over hers, holding them so that she had no chance to get away, while young Las Cases, with a mischievous smile, approached and kissed her.

As soon as her hands were at liberty, Betsy boxed the boy's ears and awaited her chance to pay Napoleon off.

There was no inside hall to go from Napoleon's apartments to the rest of the house, and it was necessary to pass outside along a steep, narrow path, wide enough for only one at a time.

An idea flashed into the mind of mischievous Betsy as Napoleon led the way, followed by Count Las Cases, his son, and last by Jane.

Betsy let the others get ahead of her, and waited when they were about ten yards distant. Then with might and main she dashed ahead, running with full force against the luckless Jane, who fell with extended hand upon young Las Cases. He in turn struck against his father, and the latter, to his dismay, against Napoleon.

The latter could hardly hold his footing, while Betsy in the rear, delighted with the success of her plan, jumped and screamed with pleasure.

The Emperor said nothing, but Las Cases, horror-struck at the insult offered his master, became furiously angry as Betsy's laughter fell on his ear.

Turning back, he caught her roughly by the shoulder and pushed her against the rocky bank. It was now Betsy's turn to be angry.

"Oh, sir, he has hurt me!"

"Never mind," replied Napoleon; "to please you, I will hold him while you punish him."

Thereupon it was young Las Cases's place to tremble. While the great man held him by the hands, Betsy gleefully boxed his ears until he begged for mercy.

"Stop, stop!" he cried.

"No, I will not. This has all been your fault. If you hadn't kissed me—"

"There, there," at last called the Emperor to the boy, "I will let you go, but you must run as fast as you can. If you cannot run faster than Betsy, you deserve to be beaten again."

The young French page did not wait for a second warning, but starting off at a run travelled as fast as he could, with Betsy in full pursuit. Napoleon, watching them, laughed heartily and clapped his hands as the two raced around the grounds. The little encounter amused him, but Las Cases the elder took the matter more seriously.

Betsy wrote, "From that moment Las Cases never liked me, after this adventure, and used to call me a little rude hoyden."

The next afternoon Betsy and Jane joined the Emperor, accompanied by General Gorgaud, in a walk in a meadow.

"Look, Betsy!" cried Jane, "there are the cows I saw the other day. I am half afraid of them."

"Nonsense! How silly!" cried the intrepid Betsy. "Afraid of a cow!" and she repeated her sister's fear to Napoleon. The latter, professing to be surprised and amused at Jane's fears, joined with Betsy in a laugh at her sister's expense. But even the dread of ridicule had little effect on Jane.

"Oh, Betsy," she cried, "I am sure one of those cows is coming at us!"

Looking up, Betsy had to admit that her sister might be right. One of the cows was rushing toward them with her head down, as if ready to attack the party. It was no time for words, and Napoleon, feeling it no disgrace to retreat in the presence of such an enemy, jumped nimbly over a wall and, standing behind it, was thus protected against the enemy.

General Gorgaud did not run, but standing with drawn sword exclaimed, "This is the second time I have saved the Emperor's life."

From behind his wall Napoleon laughed loudly at Gorgaud's boast.

"You ought to have put yourself in the position to repel cavalry," he cried.

"But really, Monsieur," said Betsy, "it was you who terrified the cows, for the moment you disappeared over the wall the animal became calm and tranquil."

"Well, well," cried Napoleon, again laughing, "it is a pity she could not carry out her good intentions. Evidently she wished to save the English Government the expense and trouble of keeping me."

"Betsy," said the sedate Jane a little later, when she had a chance to talk to her sister alone, "you ought not to speak so to the Emperor. You treat him like a child."

"Well, he seems like one of us, doesn't he, Jane? I always feel as if he were one of us, a brother of our own age, and I am sure he is much happier than if we acted as if we were afraid of him. But still, if you like, I will walk very solemnly now."

So Betsy walked along beside her sister with a slow and mincing step, her face as long as if she had lost her best friend. As she approached the Emperor he noticed the change.

"Eh, bien! qu'as tu, Mademoiselle Betsee?" he asked. "Has le petit Las Cases proved inconstant? If he have, bring him to me."

Instantly Betsy's new resolves melted away and for the rest of the walk she and Napoleon were in their usual mood of good comradeship.

The next morning, when Napoleon joined the family circle at The Briars, one of Betsy's little brothers, hardly more than a baby, sat on Napoleon's knee, and began to amuse himself as usual by playing with the glittering decorations and orders that Napoleon wore.

"Come, Mees Betsee," he cried, "there is no pleasing this child. You must come and cut off these jewels to satisfy him."

"Oh, I have something better to do now!" cried little Alexander, jumping from Napoleon's knee and picking up a pack of cards. "Look!" he continued, pointing to the figure of a Grand Mogul on the back of each card, "look, Bony, this is you."

At first the Emperor, with his imperfect knowledge of English, did not exactly understand the child's meaning. When he did, instead of taking offence, he only smiled as he turned to Betsy, saying, "But what does he mean by calling me 'Bony'?"

"Ah," replied Betsy in French, "it is short for Bonaparte." Las Cases, however, trying to improve on the little girl's definition, interpreted the word literally, "a bony person."

Napoleon laughed at this reply, adding, "Je ne suis pas osseux," and this was all. Alexander was not reproved for his familiarity.

It was true that Bonaparte was far from thin or bony, and Betsy had often admired his plump hand, which she had more than once called the prettiest in the world. Its knuckles were dimpled like a baby's, the fingers taper and beautifully formed, and the nails perfect.

"Your hand does not look large and strong enough to hold a sword," she said to him one day.

"Ah, but it is," said one of his suite, who was present. Drawing his own sabre from its scabbard, he pointed to a stain on it, saying, "This is the blood of an Englishman."

"Sheathe your sword," cried the Emperor. "It is bad taste to boast, particularly before ladies. But if you will pardon me," and he looked toward the others in the room, "I will show you a sword of mine."

Then from its embossed sheath Napoleon drew a wonderful sword with a handle in the shape of a golden fleur-de-lis. The sheath itself was hardly less remarkable, made of a single piece of tortoise shell, studded with golden bees.

The children were delighted when the Emperor permitted them to touch the wonderful weapon. It was the most beautiful sword they had ever seen.

As Betsy held the sword in her hands, unluckily she remembered a recent incident in which she had been at a great disadvantage under the Emperor's teasing. Now was her chance to get even with her tormentor.

With her usual heedlessness of consequences she drew out the sword and began to make passes at Napoleon until she had driven him into a corner.

"You must say your prayers," she said, "for I am going to kill you."

"Oh, Betsy, how can you!" remonstrated the more prudent Jane, rushing to the Emperor's assistance. "I will go and tell father."

But Betsy only laughed at her.

"I don't care," she cried. "People tease me when they like. Now it is my turn;" and she continued to thrust the sword dangerously near Napoleon's face, until her strength was exhausted, and her arm fell at her side. Count Las Cases, the dignified chamberlain, who had entered the room during the encounter, looked on indignantly. He did not quite dare to interfere, although his indignation was plainly expressed in his face. Already he had taken a deep dislike to the little girl, and to him the sword incident seemed the climax of her misbehavior. If looks could kill, she would have perished on the spot.

Although the Frenchman's expression had not the power to annihilate Betsy, something in his look warned her that she had gone far enough. Daring though she was, she decided that her wisest course was to give up the weapon. As she handed the sword back to him, Napoleon playfully pinched her ear.

It happened, unluckily, however, that Betsy's ear had been bored only the day before. The pinch consequently caused her some pain. Without venturing to resist the Emperor's touch, she gave a sharp exclamation. She knew that he had not intended to hurt her.

When the little flurry over the sword had ended, Napoleon seemed lost in thought, and the children wondered what he was thinking of. Perhaps the laughing ways of these young people reminded him of his little son, whose growth from babyhood to youth he was destined never to see. Some such thought must have been in his mind when he turned to one of his attendants, saying:

"I believe that these children would like to see some of my bijouterie. Go bring me those miniatures of the King of Rome."

In a short time the messenger returned, laden with little boxes, while the children loudly expressed their delight. They knew the story of the young Napoleon, once the pride of the French nation, on whom had been conferred the title King of Rome. They knew that he had gone to live with the Austrian Emperor, father of his mother, Maria Louisa, and perhaps some of them had heard of his stout resistance to those who came to take him away from his beautiful home, the Tuileries. Already they had seen some of the portraits of the little boy, brought by Napoleon to St. Helena, and they were pleased by the idea of seeing others of the collection.

So they gathered around the Emperor as children will when something interesting is to be shown them.

"How lovely!" cried Jane, gazing at the miniature she was first allowed to hold in her hand.

It was indeed a beautiful picture, showing a baby asleep in his cradle, which was in the shape of a helmet of Mars. Above his head the banner of France was waving and in his tiny right hand was a small globe.

"What does it mean?" asked Betsy, a little timidly now, as she noted the expression of mingled pride and sadness in Napoleon's face.

"Ah, those are the symbols of greatness. He is to be a great warrior and rule the world."

"Yes—in a minute," murmured Betsy, as one of the boys whispered to her to translate "Je prie le bon Dieu pour mon père, ma mère, et ma patrie," inscribed beneath a picture of the child on a snuffbox cover, which showed the little fellow in prayer before a crucifix. Then they both looked at another miniature portraying him riding one lamb, while he was decking another with ribbons.

"Ah!" mused the Emperor again sadly. "Those were real lambs. They were given him by the inhabitants of Paris,—a hint, I suppose, that they would rather have peace than war."

"And this is his mother," continued the Emperor, as a woman, far less handsome than Josephine, was shown in the miniature with the boy, surrounded by a halo of roses and clouds.

"She is beautiful," exclaimed Napoleon; "but I will show you the most beautiful woman in the world."

The girls echoed his words. "I never saw any one so beautiful in my life," cried Betsy, gazing on the portrait of a young, charming woman.

"And you never will," avowed Napoleon.

"The Princess of—" queried one of the French.

"My sister Pauline," said Napoleon, "and you show good taste in admiring her. She is probably one of the loveliest women ever created."

"But now," he continued, when they had seen all the pictures, "let us go down to the cottage and play whist."

Turning reluctantly from the miniatures, the children walked down to the cottage and soon were ready to play.

But the cards did not deal smoothly enough. "Go off there by yourself," said Napoleon to young Las Cases, "and deal until the cards run better. And now, Mees Betsy, tell me about your robe de bal."

Betsy's face flushed with pleasure. "Do you really want to see it? I will go upstairs and get it."

To Betsy the ball to be given soon by Sir George Cockburn was a wonderful affair. It was considered a great event by all the people of the island, but for Betsy it had a special significance, because it would be her very first ball. In England, at her age, her parents would not have thought of letting her go to a ball, but amusements were so few at St. Helena that to keep her home would have seemed cruel.

At first her parents had objected to her going, but when Napoleon saw her in tears one day and learned why, he asked her father to let her go, and thus she gained her father's consent.

It is not strange then that the little girl took a great interest in her gown for the ball, and since she felt indebted to the Emperor for his intercession, she was pleased that he expressed an interest in her costume.

So she ran upstairs light-heartedly to get the new gown, and in a few minutes returned with it on her arm.

"It is very pretty," cried the Emperor, examining the gown critically; and all the others, except the stern Las Cases, had a word of commendation for it.

It was a delicately pretty gown, trimmed with soft roses. Even if it had not been her first ball-gown, Betsy's pride in it would have been justified; but as things were, no cynical person could have found fault with her for picturing to herself what a fine impression she would make at this first appearance at a grown-up function.

The Emperor's praises were particularly gratifying, because he had a way of ridiculing any detail of dress that he did not like.

"Oh, Mees Betsee," he would cry, "why do you wear trousers? You look just like a boy;" and any one who has seen pictures of girls in pantalets will admit that they merited criticism. Or again he would say:

"If I were governor I would make a law against ladies wearing those ugly, short waists. Why do you wear them, Mees Betsee?"

It was, therefore, delightful to the young girl that he approved her ball-gown.

After sufficient praise had been given the dress, the four sat down to play, Napoleon and Jane against Las Cases and Betsy.

"Mademoiselle Betsee," said the Emperor, "I tire of sugar-plums. I bet you a napoleon on the game. What will you put against it?"

"I have no money," replied Betsy, a little shyly for her. "I have nothing worth a napoleon except—oh, yes—my little pagoda. Will that do?"

The Emperor laughed. "Yes, that will do, and I will try to get it."

So they began in merry spirits.

"There, there," cried Betsy after a minute or two, "that isn't fair. You mustn't show your cards to Jane."

"But this is such a good one." Napoleon's eye twinkled.

"Well, it isn't fair," added Betsy with the excitement in her tone often observable in vivacious natures. As the cards were shuffled she repeated, "Remember, you mustn't look at your cards until they are all dealt."

"But it seems so long to wait."

"Then I won't play. You revoked on purpose."

"Did I? Then I must hide my guilt;" and Napoleon mixed all the cards indiscriminately together, while Betsy tried to hold his hands to prevent further mischief, as she pointed out what he had done.

Napoleon, amused by Betsy's indignation, laughed until the tears came.

"Mees Betsy, Mees Betsy, I am surprised. I played so fair, and you have cheated so; you must pay me the forfeit, the pagoda."

"No, Monsieur, you revoked."

"Oh, but Mees Betsy, but you are méchante and a cheat. Ah, but I will keep you from going to the ball!"

While they were playing Betsy had quite forgotten the pretty gown that she had laid carefully on the sofa. Now, all too late, she realized its danger, for the Emperor, suddenly turning toward the sofa, seized it, and before she could stop him ran out of the room with it, toward the Pavilion.

Betsy in alarm quickly followed, but though she went fast, Napoleon went faster, and had locked himself in his room before she reached him.

Poor Betsy was now thoroughly frightened. She was sure that her pretty gown, with its trimmings of soft roses, would be destroyed.

"Oh, give it to me, please!" she cried in English, as she knocked upon his door. But the Emperor made no reply. Then she made her appeal in French, using every beseeching word she knew to get him to return it. Still his only answer was a mocking laugh, repeated several times, and an occasional word of refusal. Nor did any one else come to Betsy's assistance. As short a time as the French had lived at The Briars there was hardly one of them on whom Betsy had not played some trick, and even the members of her own family were unsympathetic when a message was brought her from Napoleon that he intended to keep her dress and that she might as well make up her mind she could not go to the ball.

Poor Betsy! At night, after many wakeful hours, she cried herself to sleep. When morning came things did not seem so black. She felt sure that the Emperor would not do what he had no right to do, keep her pretty dress. He would surely send it back to her. But the morning wore away, and, contrary to his habit, Napoleon did not come near his neighbors of The Briars. Betsy sent several strongly appealing messages, but to them all came only one reply:

"The Emperor is sleeping, and cannot be disturbed."

So strong indeed was the dignity with which Napoleon had hedged himself, that even the daring Betsy did not venture to intrude upon him when he was resting.

Afternoon came, and at last it was almost time to start for the valley. The family were to ride there on horseback, carrying their ball-dresses in tin cases, and they were to dress at the house of a friend.

The horses were brought around, the black boys came up with the tin cases that held the dresses—the dresses of the rest of the party—but nothing of poor Betsy's. The little girl's cup was full to overflowing; she, the courageous, began to cry.

She turned to one of the servants:

"Has my dress been packed?"

"Of course not; we didn't have it to pack."

"Then I cannot go."

Her tears had ceased. She was now too angry to cry longer.

"I will go anyway," she said on second thought. "I will dance in my morning frock, and then you will all feel sorry, for I will tell every one how I have been treated."

At this moment a figure was seen running down the lawn. It was Napoleon, and Betsy gave a scream of delight as she saw that in his arms he carried her dress.

Her face brightened and she hastened to meet him.

"Here, Mees Betsy," he cried; "I have brought your dress. I hope you are a good girl now, and that you will like the ball; and mind you dance with Gorgaud."

"Yes, yes!" said Betsy, too happy to get her dress to oppose any suggestion, although General Gorgaud was no favorite of hers and she had a long-standing feud with him.

"You will find your roses still fresh," said the Emperor. "I ordered them arranged and pulled out, in case any were crushed."

To the little girl's delight, when she examined her gown she found that no harm had been done it, in spite of the rough treatment it had received at Napoleon's hands.

"I wish you were going, sire," she said politely, as he walked beside the horses to the end of the bridle path.

"Ah, balls are not for me," he replied, shaking his head. Then he stopped.

"Whose house is that?" he asked, pointing to a house in the valley far beneath. "It is beautifully situated," he continued; "some time I shall visit it. Come, Las Cases, we must not detain the party."

"We must hurry on," whispered one of those on horseback.

"Good-bye, good-bye," and Napoleon and the elder Las Cases went down the mountain toward the house that he had seen in the distance, while Betsy and the others rode on toward the ball.

Next day Napoleon said that he had been charmed with the beautiful place in the valley that he and Las Cases had visited after he had seen the others ride away to the ball. He had found the owner of the place, Mr. Hodgdon, very agreeable, and at last he had ridden home on an Arab horse that the latter had lent him.

Before Napoleon withdrew within his shell he was not only inclined to receive visitors but to pay visits. Betsy and Jane were riding gayly along one day when they came unexpectedly upon Napoleon, also on horseback.

"Where have you been?" asked the venturesome Betsy.

"To Candy Bay," replied Napoleon, without resenting her inquisitiveness.

"Oh, didn't you think Fairyland just the most perfect place?"

"Yes, indeed, I was delighted with it and with its venerable host, Mr. D. He is a typical Englishman of the highest type."

"Yes, and only think, he is over seventy years old and yet has never left the island. I don't know what St. Helena would do without him," said Jane.

"I call him the good genius of the valley," added Betsy.