The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 8, Slice 10, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 8, Slice 10

"Echinoderma" to "Edward"

Author: Various

Release Date: January 17, 2011 [EBook #34992]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 8, SL 10 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

ECHINODERMA.1 The ἐχινόδερμα, or “urchin-skinned” animals, have long been a favourite subject of study with the collectors of sea-animals or of fossils, since the lime deposited in their skins forms hard tests or shells readily preserved in the cabinet. These were described during the 18th and first half of the 19th centuries by many eminent naturalists, such as J.T. Klein, J.H. Linck, C. Linnaeus, N.G. Leske, J.S. Miller, L. v. Buch, E. Desor and L. Agassiz; but it was the researches of Johannes Müller (1840-1850) that formed the groundwork of scientific conceptions of the group, proving it one of the great phyla of the animal kingdom. The anatomists and embryologists of the next quarter of a century confirmed rather than expanded the views of Müller. Thus, about 1875, the distinction of Echinoderms from such radiate animals as jelly-fish and corals (see Coelentera), by their possession of a body-cavity (“coelom”) distinct from the gut, was fully realized; while their severance from the worms (especially Gephyrea), with which some Echinoderrns were long confused, had been necessitated by the recognition in all of a radial symmetry, impressed on the original bilateral symmetry of the larva through the growth of a special division of the coelom, known as the “hydrocoel,” and giving rise to a set of water-bearing canals—the water-vascular or ambulacral system. There was also sufficient comprehension of the differences between the main classes of Echinoderms—the sea-urchins or Echinoidea, the starfish or Asteroidea, the brittle-stars and their allies known as Ophiuroidea, the worm-like Holothurians, the feather-stars and sea-lilies called Crinoidea, with their extinct relatives the sac-like Cystidea, the bud-formed Blastoidea, and the flattened Edrioasteroidea—while within the larger of these classes, such as Echinoidea and Crinoidea, fair working classifications had been established. But the study that should elucidate the fundamental similarities or homologies between the several classes, and should suggest the relations of the Echinoderma to other phyla, had scarcely begun. Indeed, the time was not ripe for such discussions, still less for the tracing of lines of descent and their embodiment in a genealogical classification. Since then exploring expeditions have made known a host of new genera, often exhibiting unfamiliar types of structure.

Among these the abyssal starfish and holothurians described by W.P. Sladen and H. Théel respectively, in the Report of the “Challenger” Expedition, are most notable. The sea-urchins, ophiuroids and crinoids also have yielded many important novelties to A. Agassiz (“Challenger,” “Blake,” and “Albatross” Expeditions), T. Lyman (“Challenger”), Sladen (“Astrophiura,” Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist., 1879), F.J. Bell (numerous papers in Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. and in Proc. Zool. Soc.), E. Perrier (“Travailleur” and “Talisman,” Cape Horn and Monaco Expeditions), P.H. Carpenter “Challenger” Reports), and others. The anatomical researches of these authors, as well as those of S. Lovén (“On Pourtalesia” and “Echinologica,” published by the Swedish Academy of Science), H. Ludwig (Morphologische Studien, Leipzig, 1877-1882), O. Hamann (Histologie der Echinodermen, Jena, 1883-1889), L. Cuénot (“Études morphologiques,” Arch. Biol., 1891, and papers therein referred to), P.M. Duncan (“Revision of the Echinoidea,” Journ. Linn. Soc., 1890), H. Prouho (“Sur Dorocidaris,” Arch. Zool. Exper., 1888), and many more, need only be mentioned to recall the great advance that has been made. In physiology may be instanced W.B. Carpenter’s proof of the nervous nature of the chambered organ and axial cords of crinoids (Proc. Roy. Soc., 1884), the researches of H. Durham (Quart. Journ. Micr. Sci., 1891) and others into the wandering cells of the body-cavity, and the study of the deposition of the skeletal substance (“stereom”) by Théel (in Festskrift för Lilljeborg, 1896). Knowledge of the development has been enormously extended by numerous embryologists, e.g. Ludwig (op. cit.), E.W. MacBride (“Asterina gibbosa,” Quart. Journ. Micr. Sci., 1896), H. Bury (Quart. Journ. Micr. Sci., 1889, 1895), Seeliger (on “Antedon,” Zool. Jahrb., 1893), S. Goto (“Asterias pallida,” Journ. Coll. Sci. Japan, 1896), C. Grave (“Ophiura,” Mem. Johns Hopkins Univ., 872 1899), Théel (“Echinocyamus,” Nov. Act. Soc. Sci. Upsala, 1892), R. Semon (“Synapta,” Jena. Zeitschr., 1888), and Lovén (opp. citt.); and though the theories based thereon may have been fantastic and contradictory, we are now near the time when the results can be co-ordinated and some agreement reached. But the scattered details of comparative anatomy are capable of manifold arrangement, while the palimpsest of individual development is not merely fragmentary, but often has the fragments misplaced. The morphologist may propose classifications, and the embryologist may erect genealogical trees, but all schemes which do not agree with the direct evidence of fossils must be abandoned; and it is this evidence, above all, that gained enormously in volume and in value during the last quarter of the 19th century. The Silurian crinoids and cystids of Sweden have been illustrated in N.P. Angelin’s Iconographia crinoideorum (1878); the Palaeozoic crinoids and cystids of Bohemia are dealt with in J. Barrande’s Système silurien (1887 and 1899); P.H. Carpenter published important papers on fossil crinoids in the Journal of the Geological Society, on Cystidea in that of the Linnean Society, 1891, and, together with R. Etheridge, jun., compiled the large Catalogue of Blastoidea in the British Museum, 1886; O. Jaekel, in addition to valuable studies on crinoids and cystids appearing in the Zeitschrift of the German Geological Society, has published the first volume of Die Stammesgeschichte der Pelmatozoen (Berlin, 1899), a richly suggestive work; the Mesozoic Echinoderms of France, Switzerland and Portugal have been made known by P. de Loriol, G.H. Cotteau, J. Lambert, V. Gauthier and others (see Paléontologie française, Mém. Soc. paléontol. de la Suisse, Trabalhos Comm. Geol. Portugal, &c.); a beautiful and interesting Devonian fauna from Bundenbach has been described by O. Follmann, Jaekel, and especially B. Stürtz (see Verhandl. nat. Vereins preuss. Rheinlande, Paläont. Abhandl., and Palaeontographica); while the multitude of North American palaeozoic crinoids has been attacked by C. Wachsmuth and F. Springer in the Proceedings (1879, 1881, 1885, 1886), of the Philadelphia Academy and the Memoirs (1897) of the Harvard Museum.

The vast mass of material made known by these and many other distinguished writers has to be included in our classification, and that classification itself must be controlled by the story it reveals. Thus it is that a change, characteristic of modern systematic zoology, is affecting the subdivisions of the classes. It is not long since the main lines of division corresponded roughly to gaps in geological history: the orders were Palaeocrinoidea and Neocrinoidea, Palechinoidea and Euechinoidea, Palaeasteroidea and Euasteroidea, and so forth. Or divisions were based upon certain modifications of structure which, as we now see, affected assemblages of diverse affinity: thus both Blastoidea and Euechinoidea were divided into Regularia and Irregularia; the Holothuroidea into Pneumophora and Apneumona; and Crinoids were discussed under the heads “stalked” and “unstalked.” The barriers between these groups may be regarded as horizontal planes cutting across the branches of the ascending tree of life at levels determined chiefly by our ignorance; as knowledge increases, and as the conception of a genealogical classification gains acceptance, they are being replaced by vertical partitions which separate branch from branch. The changes may be appreciated by comparing the systematic synopses at the end of this article with the classification adopted in 1877 in the 9th edition of the Ency. Brit. (vol. vii.), or in any zoological text-book contemporary therewith. In the present stage of our knowledge these minor divisions are the really important ones. For, whereas to one brilliant suggestion of far-reaching homology another can always be opposed, by the detailed comparison of individual growth-stages in carefully selected series of fossils, and by the minute application to these of the principle that individual history repeats race history, it actually is possible to unfold lines of descent that do not admit of doubt. The gradual linking up of these will manifest the true genealogy of each class, and reconstruct its ancestral forms by proof instead of conjecture. The problem of the interrelations of the classes will thus be reduced to its simplest terms, and even questions as to the nature of the primitive Echinoderm and its affinity to the ancestors of other phyla may become more than exercises for the ingenuity of youth. Work has been and is being done by the laborious methods here alluded to, and though the diversity of opinion as to the broader groupings of classification is still restricted only by the number of writers, we can point to an ever-increasing body of assured knowledge on which all are agreed. Unfortunately such allusion to these disconnected certainties as alone might be introduced here would be too brief for comprehension, and we are forced to select a few of the broader hypotheses for a treatment that may seem dogmatic and prejudiced.

|

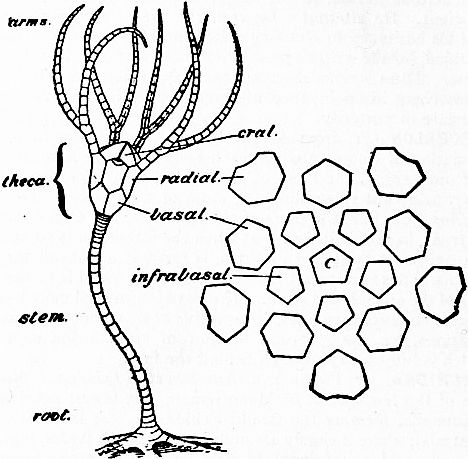

| Fig. 1.—Diagram of a simple form of Crinoid, with five arms, each forking once; the one nearest the observer is removed to expose the tegmen of five orals. This crinoid has only two circlets of plates in the cup, but the cup analysed in the adjoining diagram has in addition infrabasals and a centrale C. |

|

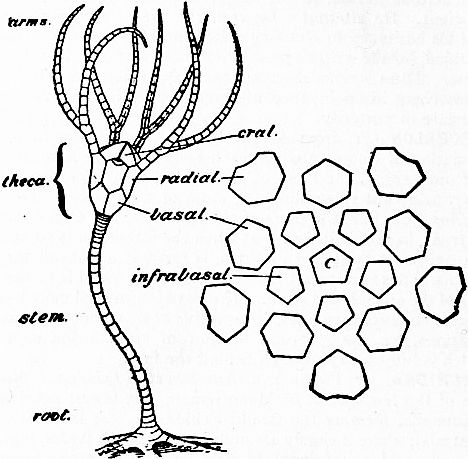

| Fig. 2.—An early stage in the development of Antedon, showing the foot-plate or “dorso-central” fp at the end of the stem col. Some of the thecal plates, infrabasals I B, basals B, and orals O are forming around the body-cavities r.pc and l.pc; p is the water-pore. (After Seeliger.) |

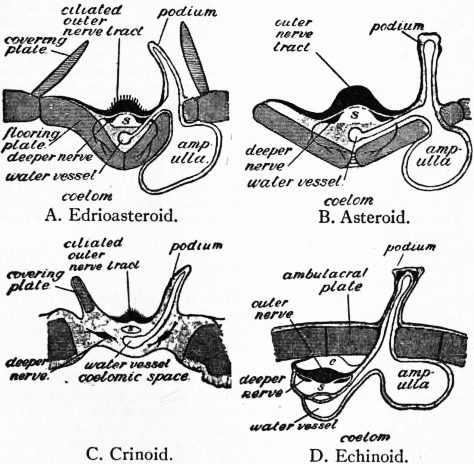

Calycinal Theory.—The theory which had most influence on the conceptions of Echinoderms in the two concluding decades of the 19th century was that of Lovén, elaborated by P.H. Carpenter, Sladen and others. This, which may be called the calycinal theory, will be appreciated by comparing the structure of a simple crinoid with that of some other types. A crinoid reduced to its simplest elements consists of three principal portions—(i.) a theca or test enclosing the viscera; (ii.) five arms stretching upwards or outwards from the theca, sometimes single, sometimes branching; (iii.) a stem stretching downwards from the theca and attaching it to the sea-floor (see fig. 1). That part of the theca below the origins of the free arms is called the “dorsal cup”; the ventral part above the origins of the arms, serving as cover to the cup, is known as the “tegmen.” All these parts are supported by plates or ossicles of crystalline carbonate of lime. The cup, in its simplest form, consists of two circlets of five plates. Each plate of the upper circlet supports an arm, and is called a “radial”; the plates of the lower circlet, the “basals,” rest on the stem and alternate with those of the upper circlet, i.e. are interradial in position. Some crinoids have yet another circlet below these, the constituent plates of which are called “infrabasals,” and are situated radially. The tegmen in most primitive forms, as well as in the embryonic stages of the living Antedon (fig. 2), consists of five large triangular plates, alternating with the radials, and called “orals,” because they roof over the mouth. In addition to these three or four circlets of plates, two other elements were once supposed essential to the ideal crinoid: the dorso-central and the oro-central. The former term was applied to a flattened plate observed in the embryonic stage of a single genus (Antedon) at that end of the stem attached to the sea-floor, and comparable to the foot of a wine-glass (fig. 2). In some crinoids which have no trace of a stem (e.g. Marsupites) a pentagonal plate is found at the bottom of the cup, where the stem would naturally have arisen (“centrale” in fig. 1); and since it was believed that the stem always grew by addition of ossicles immediately below the infrabasals, it was inferred that this pentagonal plate was the centro-dorsal in its primitive position, as though the wine-glass had been evolved from a tumbler by pulling the bottom out to form the foot. The oro-central was, it must be admitted, a theoretical conception due to a desire for symmetry, and was not confirmed by anything 873 better than some erroneous observations on certain fossils, which were supposed to show a plate at the oral pole between the five orals; but this plate, so far as it exists at all, is now known to be nothing but an oral shifted in position. The theory was that all the plates just described, and more particularly those of the cup, which were termed “the calycinal system,” could be traced, not merely in all crinoids, but in all Echinoderms, whether fixed forms such as cystids and blastoids, or free forms such as ophiuroids and echinoids, even—with the eye of faith—in holothurians. It was admitted that these elements might atrophy, or be displaced, or be otherwise obscured; but their complete and symmetrical disposition was regarded as typical and original. Thus the genera exhibiting it were regarded as primitive, and those orders and classes in which it was least obscured were supposed to approach most nearly the ancestral Echinoderm. Every one knows that an “apical system,” composed of two circlets known as “genitals” or basals and “oculars” or radials, occurs round the aboral pole of echinoids (fig. 3, A), and that a few genera (e.g. Salenia, fig. 3, B) possess a sub-central plate (the “suranal”), which might be identified with the centro-dorsal. It is also the case that many asterids (fig. 3, D) and ophiurids (fig. 3, C) have a similar arrangement of plates on the dorsal (i.e. aboral) surface of the disk. Accepting the homology of these apical systems with the calycinal system, the theory would regard the aboral pole of a sea-urchin or starfish as corresponding in everything, except its relations to the sea-floor, with the aboral pole of a fixed echinoderm.

|

| Fig. 3.-Supposed calycinal systems of free-moving Echinoderms. A, regular sea-urchin (Cidaris); B, sea-urchin with a suranal plate (Salenia); C, developing ophiurid (Amphiura); D, young starfish (Zoroaster). |

The theory has been vigorously opposed, notably by Semon (op. cit.), who saw in the holothurians a nearer approach to the ancestral form than was furnished by any calyculate echinoderm, and by the Sarasins, who derived the echinoids from the holothurians through forms with flexible tests (Echinothuridae, which, however, are now known to be specialized in this respect). The support that appeared to be given to the theory by the presence of supposed calycinal plates in the embryo of echinoids and asteroids has been, in the opinion of many, undermined by E.W. MacBride (op. cit.), who has insisted that in the fixed stage of the developing starfish, Asterina, the relations of these plates to the stem are quite different from those which they bear in the developing and adult crinoid. But, however correct the observations and the homologies of MacBride may be, they do not, as Bury (op. cit.) has well pointed out, afford sufficient grounds for his inference that the abactinal (i.e. aboral) poles of starfish and crinoids are not comparable with one another, and that all conclusions based on the supposed homology of the dorso-central of echinoids and asteroids with that of crinoids are incorrect. Bury himself, however, has inflicted a severe blow on the theory by his proof that the so-called oculars of Echinoidea, which were supposed to represent the radials, are homologous with the “terminals” (i.e. the plates at the tips of the rays) in Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea, and therefore not homologous with the radially disposed plates often seen around the aboral pole of those animals. For, if these radial constituents of the supposed apical system in an ophiurid have really some other origin, why can we not say the same of the supposed basals? Indeed, Bury is constrained to admit that the view of Semon and others may be correct, and that these so-called calycinal systems may not be heirlooms from a calyculate ancestor, but may have been independently developed in the various classes owing to the action of similar causes. That this view must be correct is urged by students of fossils. Palaeontology lends no support to the idea that the dorso-central is a primitive element; it exists in none of the early echinoids, and the suranal of Saleniidae arises from the minor plates around the anus. There is no reason to suppose that the central apical plate of certain free-swimming crinoids has any more to do with the distal foot-plate of the larval Antedon stem than has the so-called centro-dorsal of Antedon itself, which is nothing but the compressed proximal end of the stem. As for the supposed basals of Echinoidea, Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea, they are scarcely to be distinguished among the ten or more small plates that surround the anus of Bothriocidaris, which is the oldest and probably the most ancestral of fossil sea-urchins (fig. 5). A calycinal system may be quite apparent in the later Ophiuroidea and in a few Asteroidea, but there is no trace of it in the older Palaeozoic types, unless we are to transfer the appellation to the terminals. Those plates are perhaps constant throughout sea-urchins and starfish (though it would puzzle any one to detect them in certain Silurian echinoids), and they may be traced in some of the fixed echinoderms; but there is no proof that they represent the radials of a simple crinoid, and there are certainly many cystids in which no such plates existed. Lovén and M. Neumayr adduced the Triassic sea-urchin Tiarechinus, in which the apical system forms half of the test, as an argument for the origin of Echinoidea from an ancestor in which the apical system was of great importance; but a genus appearing so late in time, in an isolated sea, under conditions that dwarfed the other echinoid dwellers therein, cannot seriously be thought to elucidate the origin of pre-Silurian Echinoidea, and the recent discovery of an intermediate form suggests that we have here nothing but degenerate descendants of a well-known Palaeozoic family (Lepidocentridae). But to pursue the tale of isolated instances would be wearisome. The calycinal theory is not merely an assertion of certain homologies, a few of which might be disputed without affecting the rest: it governs our whole conception of the echinoderms, because it implies their descent from a calyculate ancestor—not a “crinoid-phantom,” that bogey of the Sarasins, but a form with definite plates subject to a quinqueradiate arrangement, with which its internal organs must likewise have been correlated. To this ingenious and plausible theory the revelations of the rocks are more and more believed to be opposed.

|

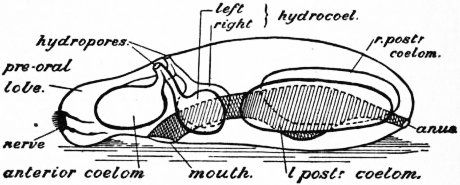

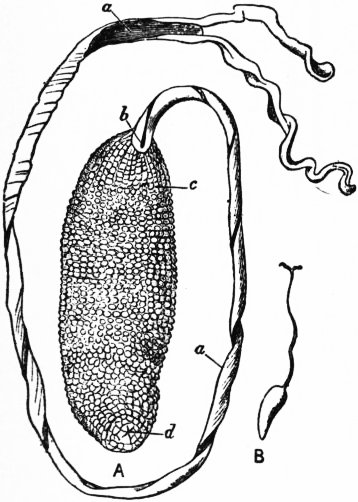

| Fig. 4.—The Pentactula stage in the development of Synapta. |

|

T, The five interradial tentacles. M, The water-pore, leading by the stone-canal stc to the water-ring, from which hangs a Polian vesicle pb. oc, Supposed otocysts. m, Longitudinal muscles. sk, Calcareous spicules. st, Stomach. (After Semon.) |

Pentactaea Theory.—In opposition to the calycinal theory has been the Pentactaea theory of R. Semon. There have always been many zoologists prepared to ascribe an ancestral character to the holothurians. The absence of an apical system of plates; the fact that radial symmetry has not affected the generative organs, as it has in all other recent classes; the well-developed muscles of the body-wall, supposed to be directly inherited from some worm-like ancestor; the presence on the inner walls of the body in the family Synaptidae of ciliated funnels, which have been rashly compared to the excretory organs (nephridia) of many worms; the outgrowth from the rectum in other genera of caeca (Cuvierian organs and respiratory trees), which recall the anal glands of the Gephyrean worms; the absence of podia (tube-feet) in many genera, and even of the radial water-vessels in Synaptidae; the absence of that peculiar structure known in other echinoderms by the names “axial organ,” “ovoid gland,” &c.; the simpler form of the larva—all these features have, for good reason or bad, been regarded as primitive. Some of the more striking of these features are confined to Synaptidae; in that family too the absence of the radial water-vessels from the adult is correlated with continuity of the circular muscle-layer, while the gut runs almost straight from the anterior mouth to the posterior anus. Early in the life-history of Synapta occurs a stage with five tentacles around the mouth, and into these pass canals from the water-ring, the radial canals to the body-wall making a subsequent, and only temporary, appearance (fig. 4). Semon called this stage the Pentactula, and supposed that, in its early history, the class had passed through a similar stage, which he called the Pentactaea, and regarded as the ancestor of all Echinoderms. It has since been proved that the five tentacles with their canals are interradial, so that one can scarcely look on the Pentactula as a primitive stage, while the apparent simplicity of the Synaptidae, at least as compared with other holothurians, is now believed to be the result of regressive 874 changes. The Pentactaea, at all events as it sprang from the brain of Semon, must pass to the limbo of mythological ancestors.

Pelmatozoic Theory.—The rejection of the calycinal and Pentactaea theories need not scatter our conceptions of Echinoderm structure back into the chaos from which they seemed to have emerged. The idea of a calyculate ancestor, though by no means connoting fixation, turned men’s minds in the direction of the fixed forms, simply because in them the calyx was best developed. The Pentactaea again suggested a search for some primitive type in which quinqueradiate symmetry was exhibited in circumoral appendages, but had not affected the nervous, water-vascular, muscular or skeletal systems to any great extent, and the generative organs not at all. Study of the earliest larval stages has always led to the conclusion that the Echinoderms must have descended from some freely-moving form with a bilateral symmetry, and, connecting this with the ideas just mentioned, we reach the conception that this supposed bilateral ancestor (or Dipleurula) may have become fixed, and may have gradually acquired a radial symmetry in consequence of its sedentary mode of life. The different extent of quinqueradiate symmetry in the different classes would thus depend on the period at which they diverged from the sedentary stock. The tracing of this history, and the explanation of the general characters of Echinoderms and of the differentiating features of the classes in accordance therewith, constitutes the Pelmatozoic theory.

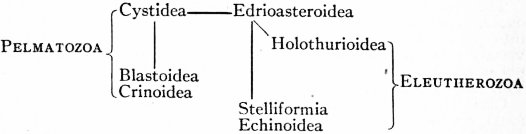

The word “Pelmatozoa” literally means “stalked animals,” but the name is now used to denote all Cystidea, Blastoidea, Crinoidea and Edrioasteroidea, as opposed to the other classes, which may be called Eleutherozoa. Many Pelmatozoa have, it is true, no stalk, while some are freely-moving, but all agree in the possession of certain characters obviously connected with a fixed mode of life. Thus, the mouth is central and turned away from the sea-floor; the animal does not seize its food by tentacles, limbs or jaws, neither does it move in search of it, but a series of ciliated grooves which radiate from the mouth sweep along currents of water, in the eddies of which minute food-particles are caught up and carried down into the gullet; the undigested food is driven out through an anus which is on the upper or oral side of the theca, but as far distant as practicable from the mouth and ciliated grooves. Such characters are found in any primitive, sedentary group. More peculiarly Echinoderm features, in which the Pelmatozoan nature is manifest, are the enclosing of the viscera in a calcified and plated theca, for protection against those enemies from which a fixed animal cannot flee; the development, at the aboral pole of this theca, of a motor nerve-centre giving off branches to the stroma connecting the various plates of the theca and of its brachial, anal, and columnar extensions, and thus co-ordinating the movements of the whole skeleton; the absence of suckers from the podia, which, when present, are respiratory, not locomotor, in function. There are other features of most, if not all, Pelmatozoa that appear to be due to a fixed existence; but those are also found in the Eleutherozoa. The Pelmatozoic theory thus regards the Pelmatozoa as the more ancestral forms, and the Pelmatozoan stage as one that must have been passed through by all Echinoderms during their evolution from the Dipleurula. It might be possible to prove the origin of all classes from Pelmatozoa, without thereby explaining the origin of such fundamental features as radial symmetry, the developmental metamorphosis, and the torsion that affects both gut and body-cavities during that process; but the acceptance of a Dipleurula as the common ancestor necessitates an explanation of these features. Such explanation is an integral part of the Pelmatozoic theory, but is provided by no other.

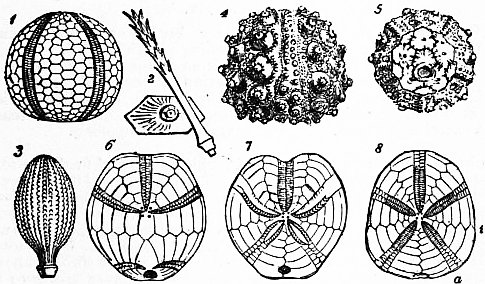

The evidence for the Pelmatozoic theory is supplied by palaeontology, embryology, the comparative anatomy of the classes, and a consideration of other phyla. Palaeontology, so far as it goes, is a sure guide, but some of the oldest fossiliferous rocks yield remains of distinctly differentiated crinoids, asteroids and echinoids, so that the problem is not solved merely by collecting fossils. Two lines of argument appear fruitful. First, a comparison of the relative numbers of the representatives of the various classes at different epochs; according to this they may be placed in the following order, with the oldest first: Cystidea, Crinoidea, Blastoidea, Asteroidea, Ophiuroidea, Echinoidea. As for Holothuroidea, the fossil evidence allows us to say no more than that the class existed in early Carboniferous times, if not before. The second method is to work out by slow and sure steps the lines of descent of the different families, orders, and classes, and so either to arrive at the ancestral form of each class, or to plot out the curve of evolution, which may then legitimately be projected into “the dark backward and abysm of time.” In this way the many highly modified orders of Cystidea may be traced back to a simple, many-plated ancestor with little or no radiate symmetry (see below). All the complicated structures of Blastoidea are evolved from a fairly simple type, which in its turn is linked on to one of the cystid orders. That the crinoids are all deducible from some such simple form as that above described under the head “calycinal theory,” is now generally admitted. Although, in the extreme correlation of the radial food-grooves, nerves, water-vessels, and so forth, with a radiate symmetry of the theca, such a type differs from the Cystidea, while in the possession of jointed processes from the radial plates, bearing the grooves and the various body-systems outwards from the theca, it differs from all other Echinoderms, nevertheless ancient forms are known which, if they are not themselves the actual links, suggest how the crinoid type may have been evolved from some of the more regular cystids. The fourth class of Pelmatozoa—the Edrioasteroidea—differs from the others in the structure of its ambulacra. As in all Pelmatozoa these seem to have borne ciliated food-grooves protected by movable covering-plates (fig. 11). Beneath each food-groove was a radial water-vessel and probably a nerve and blood-vessel, all which structures passed either between certain regularly arranged thecal plates, or along a furrow floored by those plates, which were then in two alternating series. The important and distinctive feature is the presence of pores between the flooring-plates, on either side of the groove; and these, we cannot doubt, served for the passage of podia. Thus in a highly developed edrioasteroid, such as Edrioaster itself (fig. 11), there was a true ambulacrum, apparently constructed like that of a starfish, but differing in the possession of a ciliated food-groove protected by covering-plates. The simpler forms of Edrioasteroidea, with their more sac-like body and undifferentiated plates, may well have been derived from early Cystidea of yet simpler structure, and there seems no reason to follow Jaekel in regarding the class as itself the more primitive. Turning to fossil Asteroidea, we find the earlier ophiurids scarcely distinguishable from the asterids, while in the alternation of the ambulacrals, which undoubtedly correspond to the flooring-plates of Edrioaster, both groups approach the Pelmatozoan type. These facts have been expressed by Sturtz in his names Encrinasteriae and Ophio-encrinasteriae. There is no difficulty in deducing the highly differentiated asterids and ophiurids of a later day from these simpler types. The evolution of the modern Echinoidea from their Palaeozoic ancestors is also well understood, but in this case the ancestral form to which the palaeontologist is led does not at first sight present many resemblances to the Pelmatozoa. It is, however, characterized by simplicity of structure, and a short description of it will serve to clear the problem from unnecessary difficulties. Bothriocidaris (fig. 5), a small echinoid from the Ordovician rocks of Esthonia, is in essential structure just the form demanded by comparative palaeontology to make a starting-point. It is spheroidal, with the mouth and anus at opposite poles; there are five ambulacra, and the ambulacral plates are large, simple and alternating, each being pierced by two podial pores which lie in a small oval depression; the ambulacrals next the mouth form a closed ring of ten plates; the interambulacrals lie in single columns between the ambulacra, and are separated from the mouth-area by the proximal ambulacrals just mentioned, and sometimes by the second set of ambulacrals also; the ambulacra end in the five oculars or terminals, which meet in a ring around the anal area and have no podial pores, but one of them serves as a madreporite; within this ring is a star-shaped area filled with minute irregular plates, none of which can safely be selected as the homologues of the so-called basals or genitals of later forms; within the ring of ambulacrals around the mouth are five somewhat pointed plates, which Jaekel regards as teeth, but which can scarcely be homologous with the interradially placed teeth of later echinoids, since they are radial in position; small spines are present, especially around the podial pores. The position of the pores near the centre of the ambulacrals in Bothriocidaris need not be regarded as primitive, since other early Palaeozoic genera, not to mention the young of living forms, show that the podia originally passed out between the plates, and were only gradually surrounded by their substance; thus the original structure of the echinoid ambulacra differed from that of the early asteroid in the position of the radial vessels and nerves, which here lie beneath the plates instead of outside them. To this point we shall recur; palaeontology, though it suggests a clue, does not furnish an actual link either between Echinoidea and Asteroidea, or between those classes and Pelmatozoa.

|

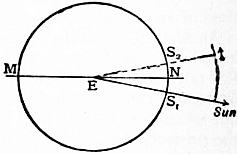

| Fig. 5.—Bothriocidaris globulus. A, from the side; B, the plates around the aboral pole. (After Jaekel.) The short spines which were attached to the tubercles are not drawn. |

The argument from embryology leads further back. First, as already mentioned, it outlines the general features of the Dipleurula; secondly, it indicates the way in which this free-moving form became fixed, and how its internal organs were modified in consequence; but when we seek, thirdly, for light on the relations of the classes, we find the features of the adult coming in so rapidly that such intermediate stages as may have existed are either squeezed out or profoundly modified. The difficulty of rearing the larvae in an 875 aquarium towards the close of the metamorphosis may account for the slight information available concerning the stages that immediately follow the embryonic. Another difficulty is due to the fact that the types studied, and especially the crinoid Antedon, are highly specialized, so that some of the embryonic features are not really primitive as regards the class, but only as regards each particular genus. Thus inferences from embryonic development need to be checked by palaeontology, and supplemented by comparison of the anatomy of other living genera.

Minute anatomical research has also aided to establish the Pelmatozoic theory by the gradual recognition in other classes of features formerly supposed to be confined to Pelmatozoa. Thus the elements of the Pelmatozoan ventral groove are now detected in so different a structure as the echinoid ambulacrum, while an aboral nervous system, the diminished representative of that in crinoids, has been traced in all Eleutherozoa except Holothurians. The broader theories of modern zoology might seem to have little bearing on the Echinoderma, for it is not long since the study of these animals was compared to a landlocked sea undisturbed by such storms as rage around the origin of the Vertebrata. This, however, is no more the case. The conception of the Dipleurula derives its chief weight from the fact that it is comparable to the early larval forms of other primitive coelomate animals, such as Balanoglossus, Phoronis, Chaetognatha, Brachiopoda and Bryozoa. So too the explanation of radial symmetry and torsion of organs as due to a Pelmatozoic mode of life finds confirmation in many other phyla. Instead of discussing all these questions separately, with the details necessary for an adequate presentation of the argument, we shall now sketch the history of the Echinoderms in accordance with the Pelmatozoic theory. Such a sketch must pass lightly over debatable ground, and must consist largely of suggestions still in need of confirmation; but if it serves as a frame into which more precise and more detailed statements may be fitted as they come to the ken of the reader, its object will be attained.

Evolution of the Echinoderms.—It is reasonable to suppose that the Coelomata—animals in which the body-cavity is divided into a gut passing from mouth to anus and a hollow (coelom) surrounding it—were derived from the simpler Coelentera, in which the primitive body-cavity (archenteron) is not so divided, and has only one aperture serving as both mouth and anus. We may, with Sedgwick, suppose the coelom to have originated by the enlargement and separation of pouches that pressed outwards from the archenteron into the thickened body-wall (such structures as the genital pouches of some Coelentera, not yet shut off from the rest of the cavity), and they would probably have been four in number and radially disposed about the central cavity. The evolution of this cavity into a gut is foreshadowed in some Coelentera by the elliptical shape of the aperture, and by the development at its ends of a ciliated channel along which food is swept; we have only to suppose the approximation of the sides of the ellipse and their eventual fusion, to complete the transformation of the radially symmetrical Coelenterate into a bilaterally symmetrical Coelomate with mouth and anus at opposite ends of the long axis. We further suppose that of the four coelomic pouches one was in front of the mouth, one behind the anus, and one on each side. Such an animal, if it ever existed, probably lived near the surface of the sea, and even here it may have changed its medusoid mode of locomotion for one in the direction of its mouth. Thus the bilateral symmetry would have been accentuated, and the organism shaped more definitely into three segments, namely (1) a preoral segment or lobe, containing the anterior coelomic cavity; (2) a middle segment, containing the gut, and the two middle coelomic cavities; (3) a posterior segment, containing the posterior coelomic cavity, which, however, owing to the backward prolongation of the anus, became divided into two—a right and left posterior coelom. Each of these cavities presumably excreted waste products to the exterior by a pore. There was probably a nervous area, with a tuft of cilia, at the anterior end; while, at all events in forms that remained pelagic, the ciliated nervous tracts of the rest of the body may be supposed to have become arranged in bands around the body-segments. Such a form as this is roughly represented to-day by the Actinotrocha larva of Phoronis, the importance of which has been brought out by Masterman. But only slight modifications are required to produce the Tornaria larva of the Enteropneusta and other larvae, including the special type that is inferred from the Dipleurula larval stages of recent forms to have characterized the ancestor of the Echinoderms. We cannot enter here into all the details of comparison between these larval forms; amid much that is hypothetical a few homologies are widely accepted, and the preceding account will show the kind of relation that the Echinoderms bear to other animals, including what are now usually regarded as the ancestors of the Chordata (to which back-boned animals belong), as well as the nature of the evidence that their study has been, or may be, made to yield. How the hypothetical Dipleurula became an Echinoderm, and how the primitive Echinoderms diverged in structure so as to form the various classes, are questions to which an answer is attempted in the following paragraphs:—

|

| Fig. 6.—Diagrammatic reconstruction of Dipleurula. The creature is represented crawling on the sea-floor, but it may equally well have been a floating animal. The ciliated bands are not drawn. |

Confining our attention to that form of Dipleurula (fig. 6) which, it is supposed, gave rise to the Echinoderma, we infer from embryological data that its special features were as follow:—The anterior coelomic cavity was wholly or partially divided, and from each half a duct led to the exterior, opening at a pore near the middle line of the back. The middle cavities were smaller, and the ducts from them came to unite with those from the anterior cavities, and no longer opened directly to the exterior; whether these cavities were already specialized as water-sacs cannot be asserted, but they certainly had become so at a slightly later stage. The posterior cavities were the largest, but what had become of their original opening to the exterior is uncertain. The genital products were derived from the lining of the coelomic cavities, but it would not be safe to say that any particular region was as yet specialized for generation. The epithelium of the outer surface was probably ciliated, and a portion of it in the preoral lobe differentiated as a sense-organ, with longer cilia and underlying nerve-centre, from which two nerves ran back below the ventral surface. Into the space between the walls of the coelom and the outer body-wall, originally filled with jelly, definite cells now wandered, chiefly derived from the coelomic walls. Some of these cells produced muscles and connective tissue; others absorbed and removed waste products, iron salts, calcium carbonate and the like, and so were ready to be utilized for the deposition of pigment or of skeletal substance. In some of these respects the Dipleurula may have diverged from the ancestor of Enteropneusta and of other animals, but it could not as yet have been recognized as echinodermal by a zoologist, for it presented none of the structural peculiarities of the modern adult echinoderm.

|

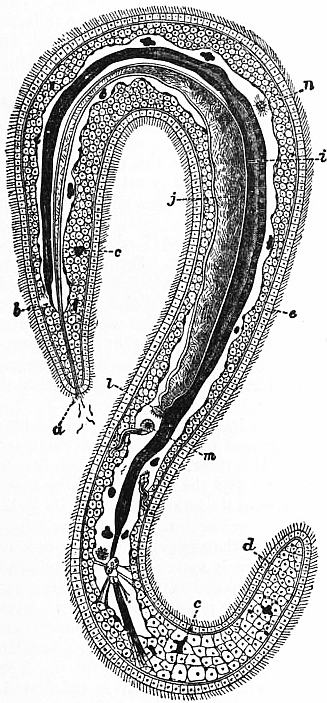

| Fig. 7.—Diagrammatic reconstruction of primitive Pelmatozoön, seen from the side. The plates of the test are not drawn; their probable appearance may be gathered from fig. 8. |

|

| Fig. 8.—Aristocystis bohemicus; side-view of the theca. The internal structure may be gathered from fig. 7. |

|

| Fig. 9.—Fungocystis rarissima, one of the Diploporita, in which the thecal plates bordering the food-grooves are not yet regularly arranged. The brachioles are not drawn. |

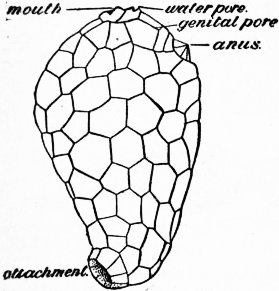

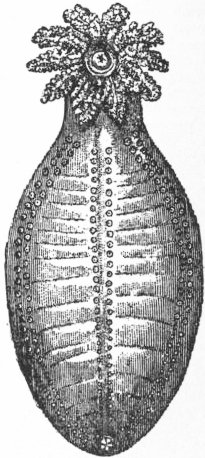

Now ensued the great event that originated the phylum—the discovery of the sea-floor. This being apprehended by the sensory anterior end, it was by that end that the Dipleurula attached itself; not, however, by the pole, since that would have interfered at once with the sensory organ, but a little to one side, the right 876 side being the one chosen for a reason we cannot now fathom; it may be that fixation was facilitated by the presence of the pore on that side, and by the utilization of the excretion from it as a cement. The first result was that which is always seen to follow in such cases—the passage of the mouth towards the upper surface (fig. 7). As it passed up along the left side, the gut caught hold of the left water-sac and pulled it upwards, curving it in the process; this being attached to the left duct from the anterior body-cavity, this structure with its water-pore was also pulled up, and the pore came to lie between mouth and anus. The forward portion of the anterior coelom shared in the constriction and elongation of the preoral lobe; but its hinder portion was dragged up along with the water-pore and formed a canal lying along the outer wall (the parietal canal). As the gut coiled, it pressed inwards the middle of the left posterior coelom of the Dipleurula, and drew the whole towards the mouth, while the corresponding cavity on the right was pressed down by the stomach towards the fixed end of the animal and became involved in the elongation of that region. These changes, which may still be traced in the development of Antedon, resulted in the primitive Pelmatozoön (fig. 7), represented in the rocks by such a genus as Aritocystis (fig. 8). The pear-shaped body is encased in a theca formed by a number of polygonal plates, and is attached by its narrow end. On the broad upper surface are four openings, that nearest the centre being the mouth, which is slit-like, and that nearest the periphery being the anus. The two other openings are minute, and placed between those two; one close to the mouth is almost certainly the water-pore, while that nearer the anus is regarded as a genital aperture. Which of the coelomic cavities this last is connected with is uncertain, for there is considerable doubt as to the origin of the genital glands in the embryonic development of recent echinoderms. It seems clear, however, that there was but a single duct and a single bunch of reproductive cells, as in the holothurians, though perhaps bifurcate, as in some of those animals. The line between mouth and anus, along which these openings are situate, corresponds with the plane of union between the two horns of the curved left posterior coelom, the united walls of which form the “dorsal mesentery.” Since this must have, on our theory, enclosed the parietal canal from the anterior coelom, it is possible that the genital products were developed from the lining cells of that cavity, and that the genital pore was nothing but its original pore not yet united with that from the water-sac. The concrescence of these pores can be traced in other cystids; but as the genital organs became affected by radial symmetry the original function of the duct was lost, and the reproductive elements escaped to the exterior in another way. Aristocystis may have had ciliated food-grooves leading to its mouth, but these have left no traces on the structure of the test. Traces, however, are perceptible in genera believed to be descended from such a simple type, and the majority may be grouped under two heads. One group includes those in which the grooves wander outwards from the mouth over the thecal plates, which gradually become arranged regularly on either side of the grooves, while further extensions ascend from the grooves on small jointed processes called “brachioles” (fig. 9). In the other group the grooves do not tend so much to stretch over the theca as to be raised away from it on relatively larger brachioles, arising close around the mouth (fig. 10).

|

| Fig. 10.—Chirocrinus-alter, one of the Rhombifera, showing the reduced number and regular arrangement of the thecal plates, and the concentration of the brachioles. (Adapted from Jaekel.) |

These two types are, in the main, correlated with two gradual differentiations in the minute structure of the thecal plates. Originally the calcareous substance of the plates (stereom) was pierced by irregular canals, more or less vertical, and containing strands of the soft tissue (stroma) that deposited the stereom, as well as spaces filled with fluid. In the former group (fig. 9) these canals became connected in pairs (diplopores) still perpendicular to the surface, and this structure, combined with that of the grooves, characterizes the order—Diploporita. In the latter group (fig. 10) the canals, that is to say, the stroma-strands, came to lie parallel to the surface and to cross the sutures between the plates, which were thus more flexibly and more strongly united: since the canals crossing each suture naturally occupy a rhombic area, the order is called Rhombifera. At first the grooves were three, one proceeding from each end of the mouth-slit, and the third in a direction opposed to the anus; with reference to the Pelmatozoan structure, the anal side may be termed posterior, and this groove anterior. Eventually each lateral groove forked, so that there were five grooves. These gradually impressed themselves on the theca and influenced the arrangement of the internal organs: it is fairly safe to assume that nerves, blood-vessels and branches from the water-sac stretched out along with these grooves, each system starting from a ring around the gullet. At last a quinqueradiate symmetry influenced the plates of the theca, partly through the development of a plate at the end of each groove (terminal), partly through plates at the aboral pole of the theca (basals and infrabasals) arising in response to mechanical pressure, but soon intimately connected with the cords of an aboral nervous system. Before the latter plates arose, the stem had developed by the elongation and constriction of the fixed end of the theca, the gradual regularization of the plates involved, and their coalescence into rings. The crinoid type was differentiated by the extension of the food-grooves and associated organs along radial outgrowths from the theca itself. These constituted the arms (brachia), and five definite radial plates of the theca were specialized for their support. These radials may be homologous with the terminals already mentioned, but this is neither necessary nor certain. In this development of brachial extensions of the theca the genital organs were involved, and their ripe products formed at the ends of the brachia or in the branches therefrom. The remains of the original genital gland within the theca became the “axial organ” surrounded by the “axial sinus” derived from the anterior coelom, and this again by structures derived from the right posterior coelom, which, as explained above, had been depressed to the aboral pole. These last structures formed a nervous sheath around the axial sinus with its blood-vessels, and became divided into five lobes correlated with the five basals (the “chambered organ”) and forming the aboral nerve-centre. Before these changes were complete the Holothurioidea must have diverged, by the assumption of a crawling existence. Thus in them the mouth and anus reverted to opposite poles, and only the torsion of the gut and coelom, and the radial extensions of the nervous, water-vascular and blood-vascular systems, testified to their Pelmatozoan ancestry. The ciliated grooves, no longer needed for the collection of food, closed over, and are still traceable as ciliated canals overlying the radial nerves. At the same time the thecal plates degenerated into spicules. The Edrioasteroidea followed a different line from that of the cystids above mentioned and their descendants. The theca became sessile, and in its later developments much flattened (fig. 11). Mouth, water-pore and anus remained as in Aristocystis, but the five ciliated grooves radiated from the mouth between the thecal plates rather than over them, and were, as usual, protected by covering-plates. The important feature was the extension of radial canals from the water-sac along these grooves, with branches passing between the flooring-plates of the grooves (fig. 12, A). The resemblance of the flooring-plates to the ambulacral ossicles of a starfish is so exact that one can explain it only by supposing similar relations of the water-canals and their branches (podia). On the thinly plated under surface of well-preserved specimens of Edrioaster are seen five interradial swellings (fig. 11, B). These are likely to have been produced by the ripe genital glands, which may have extruded their products directly through the membranous integument of the under side. No other way out for them is apparent, and it is clear that Edrioaster was not permanently and solidly fixed to the sea-floor.

|

| Fig. 11.—Edrioaster. A, upper or oral surface of E. Bigsbyi, with the covering-plates on the anterior and left posterior food-grooves, but removed from the others, which show only the flooring-plates, between which are pores; B, under surface of E. Buchianus, with covering-plates on right posterior and right anterior food-grooves (left hand in the drawing). The * denotes the position of the anal interradius. |

Now comes a great change, unfortunately difficult to follow whether in the fossils or in the modern embryos. We suppose some such form as Edrioaster, which appears to have lived near the shore, to have been repeatedly overturned by waves. Those that were able to accommodate themselves to this topsy-turvy 877 existence, by taking food in directly through the mouth, survived, and their podia gradually specialized as sucking feet. Such a form as this, when once its covering-plates had atrophied, would be a starfish without more ado (fig. 12, B); but the sea-urchins present a more difficult problem, on which Bothriocidaris sheds no light. An Upper Silurian echinoid, however, Palaeodiscus, is believed by W.J. Sollas and W.K. Spencer to have had in its ambulacra an inner as well as an outer series of plates. If this be correct, the only change from Edrioaster, as regards the ambulacra, was that in Palaeodiscus the covering-plates could no longer open, but closed permanently over the whole groove, while the podia issued through slits between them. In more typical echinoids the covering-plates alone remained to form the ordinary ambulacral plates, while the flooring-plates disappeared, the canals and other organs remaining as before. In any case we have to admit a closure of the integument over the ciliated groove (fig. 12, D, e) just as in holothurians, since this is necessitated by anatomical evidence. The genital organs in both Asteroidea and Echinoidea would retain the interradial position they first assumed in Edrioaster; and in Echinoidea their primitive temporary openings to the exterior were converted into definite pores, correlated with five interradially placed plates at the aboral pole. The anus also naturally moved to this superior and aboral position. In the Echinoidea the water-canals and associated structures, ending in the terminal plates, stretched right up to these genital plates; but in the Asteroidea they never reached the aboral surface, so that the terminals have always been separated from the aboral pole by a number of plates.

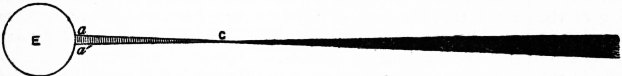

|

| Fig. 12.-Diagrammatic sections across the ambulacra of A, C, Pelmatozoa, and B, D, Eleutherozoa, placed in the same position for comparison. S, Blood-spaces, of which the homology is still uncertain. |

Analysis of Echinoderm Characters.—Regarding the Echinoderms as a whole in the light of the foregoing account, we may give the following analytic summary of the characters that distinguish them from other coelomate animals:—

They live in salt or brackish water; a primitive bilateral symmetry is still manifest in the right and left divisions of the coelom; the middle coelomic cavities are primitively transformed into two hydrocoels communicating with the exterior indirectly through a duct or ducts of the anterior coelom; stereom, composed of crystalline carbonate of lime, is, with few exceptions, deposited by special amoebocytes in the meshes of a mesodermal stroma, chiefly in the integument; reproductive cells are derived from the endothelium, apparently of the anterior coelom; total segmentation of the ovum produces a coeloblastula and gastrula by invagination; mesenchyme is formed in the segmentation cavity by migration of cells, chiefly from the hypoblast. Known Echinoderms show the following features, imagined to be due to an ancestral pelmatozoic stage:—Increase in the coelomic cavities of the left side, and atrophy of those on the right; the dextral coil of the gut, recognizable in all classes, though often obscured; an incomplete secondary bilateralism about the plane including the main axis and the water-pore or its successor, the madreporite, often obscured by one or other of various tertiary bilateralisms; the change of the hydrocoel into a circumoral, arcuate or ring canal; development through a free-swimming, bilaterally symmetrical, ciliated larva, of which in many cases only a portion is transformed into the adult Echinoderm (where care of the brood has secondarily arisen, this larva is not developed). All living, and most extinct, Echinoderms show the following features, almost certainly due to an ancestral pelmatozoic stage:—An incomplete radial symmetry, of which five is usually the dominant number, is superimposed on the secondary bilateralism, owing to the outgrowth from the mouth region of one unpaired and two paired ciliated grooves; these have a floor of nervous epithelium, and are accompanied by subjacent radial canals from the water-ring, giving off lateral podia and thus forming ambulacra, and by a perihaemal system of canals apparently growing out from coelomic cavities. All living Echinoderms have a lacunar, haemal system of diverse origin; this, the ambulacral system, and the coelomic cavities, contain a fluid holding albumen in solution and carrying numerous amoebocytes, which are developed in special lymph-glands and are capable of wandering through all tissues. The Echinoderms may be divided into seven classes, whose probable relations are thus indicated:—

|

Brief systematic accounts of these classes follow:—

Grade A. PELMATOZOA.—Echinoderma with the viscera enclosed in a calcified and plated theca, of which the oral surface is uppermost, and which is usually attached, either temporarily or permanently, by the aboral surface. Food brought to the mouth by a subvective system of ciliated grooves, radiating from the mouth either between the plates of the theca (endothecal), or over the theca (epithecal), or along processes from the theca (exothecal: arms, pinnules, &c.), or, in part, and as a secondary development, below the theca (hypothecal). Anus usually in the upper or oral half of the theca, and never aboral. An aborally-placed motor nerve-centre gives off branches to the stroma connecting the various plates of the theca and of its brachial, anal and columnar extensions, and thus co-ordinates the movements of the whole skeleton. The circumoesophageal water-ring communicates indirectly with the exterior; the podia, when present, are respiratory, not locomotor, in function.

Class I. Cystidea.—Pelmatozoa in which radial polymeric symmetry of the theca is developed either not at all or not in complete correlation with the radial symmetry of the ambulacra (such as obtains in Blastoidea and Crinoidea); in which extensions of the food-grooves are exothecal or epithecal or both combined, but neither endothecal nor pierced by podia (as in some Edrioasteroidea) All Palaeozoic.

This class shows much greater diversity of organization than any other, and the classifications proposed by recent writers, such as E. Haeckel, O. Jaekel and F.A. Bather, start from such different points of view that no discussion of them can be attempted here. Following the narrative given above, we recognize a primitive group—Amphoridea—represented by Aristocystis (fig. 8). From this are derived the orders Diploporita (fig. 9) and Rhombifera (fig. 10) and the class Edrioasteroidea, all which have already been described as steps in the evolution of the phylum. But there were also side-branches leading nowhere, and therefore placed in separate orders—Aporita and Carpoidea.

Order 1. Amphoridea.—Radial symmetry has affected neither food-grooves nor thecal plates; nor, probably, nerves, ambulacral vessels, nor gonads. Canals or folds when present in the stereom are irregular. Families: Aristocystidae (fig. 8); Eocystidae.

Order 2. Carpoidea.—Theca compressed in the oro-anal plane and a bilateral symmetry thus induced, affecting the food-grooves and, usually, the thecal plates and stem. Food-grooves in part epithecal and may be continued on one or two exothecal processes. No pores or folds in the stereom. Families: Anomalocystidae, Dendrocystidae. These correspond to Jaekel’s Carpoidea Heterostelea; he also includes, as Eustelea, our Comarocystidae and Malocystidae.

Order 3. Rhombifera.—Radial symmetry affects the food-grooves and, in the more advanced families, the thecal plates; probably also the nerves and ambulacral vessels, but not the gonads. The food-grooves are exothecal, i.e. are stretched out from the theca on jointed skeletal processes (brachioles). These either are close to the mouth or are removed from it upon a series of ambulacral or sub-ambulacral plates not derived immediately from thecal plates, or are separated from the oral centre by hypothecal passages passing beneath terminal plates. The stereom and stroma become arranged in folds and strands at right angles to the sutures of the thecal plates; in higher forms the stereom-folds are in part specialized as pectini-rhombs. Families: Echinosphaeridae; Comarocystidae; Macrocystellidae; Tiaracrinidae; Malocystidae; Glyptocystidae, with sub-famm. Echinoencrininae, Callocystinae, Glyptocystinae, of which examples are Cheirocrinus (fig. 10) and Cystoblastus from which Jaekel deduces the blastoids; Caryocrinidae.

Order 4. Aporita.—Pentamerous symmetry affects the food-grooves and thecal plates; probably also the nerves and ambulacral vessels, but not the gonads. Food-grooves exothecal and circumoral. The stereom shows no trace of canals, folds, rhombs or diplopores. Family: Cryptocrinidae.

Order 5. Diploporita.—Radial symmetry affects the food-grooves, and by degrees the thecal plates connected therewith, but not the interradial thecal plates; probably also the nerves and ambulacral vessels, but not the gonads. The food-grooves are epithecal, i.e. are extended over the thecal plates themselves without intermediate flooring; they are also prolonged on exothecal brachioles, which line the epithecal grooves. The stereom of the thecal plates may be thrown into folds, but the mesostroma does not so much tend to lie in strands traversing the sutures, nor are pectini-rhombs or pore-rhombs developed; diplopores are always present in the mesostereom, but often restricted to definite tracts or plates, especially in higher forms. Families: Sphaeronidae; Glyptosphaeridae, e.g. Fungocystis (fig. 9); Protocrinidae; Mesocystidae; Gomphocystidae.

The Protocrinidae lead up to Proteroblastus, in which the theca is ovoid, sometimes prolonged into a stem, the plates differentiated into (a) smooth, irregular, depressed interambulacrals, (b) transversely elongate brachioliferous adambulacrals, to which the diplopores, which lie at right angles to the main food-groove, are confined. This leads almost without a break to the Protoblastoidea.

Class II. Blastoidea.—Pelmatozoa in which five (by atrophy four) epithecal ciliated grooves, lying on a lancet-shaped plate (? always), radiate from a central peristome between five interradial deltoid plates, and are edged by alternating side-plates bearing brachioles, to which side-branches pass from the grooves. Grooves and peristome protected by small plates, which can open over the grooves. The generative organs and coelom probably did not send extensions along the rays into the brachioles; but apparently nerves from the aboral centre, after passing through the thecal plates, met in a circumoral ring, from which branches passed into the plate under each main food-groove, and thence supplied the brachioles. The thecal plates, however irregular in some species, always show defined basals and a distinct plate (“radial”) at the end of each ambulacrum; they are in all cases so far affected by pentamerous symmetry that their sutures never cross the ambulacra. All Palaeozoic.

Division A. Protoblastoidea.—Blastoidea without interambulacral groups of hydrospire-folds hanging into the thecal cavity. Families: Asteroblastidae, Blastoidocrinidae. The former might be placed with Diploporita, were it not for a greater intimacy of correlation between ambulacral and thecal structures than is found in Cystidea as here defined. They form a link between the Protocrinidae and—

|

| Fig. 13.—A Eublastoid, Pentremites. |

Division B. Eublastoidea.—Blastoidea in which the thecal plates have assumed a definite number and position in 3 circlets, as follows: 3 basals, 2 large and 1 small; 5 radials, often fork-shaped, forming a closed circlet; 5 deltoids, interradial in position, supported on the shoulders or processes of the radials, and often surrounding the peristome with their oral ends. The stereom of the radials and deltoids on each side of the ambulacra is thrown into folds, running across the radio-deltoid suture, and hanging down into the thecal cavity as respiratory organs (hydrospires).

These are the forms to which the name Blastoidea is usually restricted. They have been divided into Regulares and Irregulares, but it seems possible to group them according to three series or lines of descent, thus:—

Series a. Codonoblastida.—Families: Codasteridae, Pentremitidae (fig. 13).

Series b. Troostoblastida.—Families: Troostocrinidae, Eleutherocrinidae.

Series c. Granatoblastida.—Families: Nucleocrinidae, Orbitremitidae, Pentephyllidae, Zygocrinidae.

Class III. Crinoidea.—Pelmatozoa in which epithecal extensions of the food-grooves, ambulacrals, superficial oral nervous system, blood-vascular and water-vascular systems, coelom and genital system are continued exothecally upon jointed outgrowths of the abactinal thecal plates (brachia), carrying with them extensions of the abactinal nerve-system. The number of these processes is primitively and normally five, but may become less by atrophy. The brachia rise from a corresponding number of thecal plates, “radials (RR).” Below these is always a circlet, or traces of a circlet, of plates alternating with the radials, i.e. interradial, and called “basals (BB).” Through all modifications, which are numerous and vastly divergent, these elements persist. A circlet of radially situate infrabasals (IBB) may also be present. Below BB or IBB there follows a stem, which, however, may be atrophied or totally lost (see fig. 1).

The classification here adopted is that of F.A. Bather (1899), which departs from that of Wachsmuth and Springer mainly in the separation of forms with infrabasals or traces thereof from those in which basals only are present. These two series also differ from each other in the relations of the abactinal nerve-system. O. Jaekel (1894) has divided the crinoids into the orders Cladocrinoidea and Pentacrinoidea, the former being the Camerata of Wachsmuth and Springer (Monocyclica Camerata, Adunata and Dicyclica Camerata of the present classification), and the latter comprising all the rest, in which the arms are either free or only loosely incorporated in the dorsal cup. In minor points there is fair agreement between the American, German and British authors. The families are extinct, except when the contrary is stated.

Sub-class I. Monocyclica.—Crinoidea in which the base consists of BB only, the aboral prolongations of the chambered organ being interradial; new columnals are introduced at the extreme proximal end of the stem.

Order 1. Monocyclica Inadunata.—Monocyclica in which the dorsal cup is confined to the patina and occasional intercalated anals; such ambulacrals or interambulacrals as enter the tegmen remain supra-tegminal and not rigidly united. Families: Hybocrinidae, Stephanocrinidae, Heterocrinidae, Calceocrinidae, Pisocrinidae, Zophocrinidae, Haplocrinidae, Allagecrinidae, Symbathocrinidae, Belemnocrinidae, Plicatocrinidae, Hyocrinidae (recent), Saccocomidae.

Order 2. Adunata.—Monocyclica with dorsal cup primitively confined to the patina and an occasional single anal; tegmen solid; portions of the proximal brachials and their ambulacrals tend to be rigidly incorporated in the theca. Arms fork once to thrice, and bear pinnules on each or on every other brachial. BB fused to 3, 2 or 1. (Eucladocrinus and Acrocrinidae offer peculiar exceptions to this diagnosis.) Families: Platycrinidae, Hexacrinidae, Acrocrinidae.

Order 3. Monocyclica Camerata.—Monocyclica in which the first, and often the succeeding, orders of brachials are incorporated by interbrachials in the dorsal cup, while the corresponding ambulacrals are either incorporated in, or pressed below, the tegmen by interambulacrals; all thecal plates united by suture, somewhat loose in the earliest forms, but speedily becoming close, and producing a rigid theca; mouth and tegminal food-grooves closed; arms pinnulate.

Sub-order i. Melocrinoidea.—RR in contact all round; first brachial usually quadrangular. Families: Glyptocrinidae, Melocrinidae, Patelliocrinidae, Clonocrinidae, Eucalyptocrinidae, Dolatocrinidae.

Sub-order ii. Batocrinoidea.—RR separated by a heptagonal anal; first brachial usually quadrangular. Families: Tanaocrinidae, Xenocrinidae, Carpocrinidae, Barrandeocrinidae, Coelocrinidae, Batocrinidae, Periechocrinidae.

Sub-order iii. Actinocrinoidea.—RR separated by a hexagonal anal; first brachial usually hexagonal. Families: Actinocrinidae, Amphoracrinidae.

Sub-class II. Dicyclica.—Crinoidea in which the base consists of BB and IBB, the latter being liable to atrophy or fusion with the proximale, but the aboral prolongations of the chambered organ are always radial; new columnals may or may not be introduced at the proximal end of the stem.

Order 1. Dicyclica Inadunata.—Dicyclica in which the dorsal cup primitively is confined to the patina and occasional intercalated anals, and no other plates ever occur between RR (Grade: Distincta); Br may be incorporated in the cup, with or without iBr, but never rigidly, and their corresponding ambulacrals remain supra-tegminal (Grade: Articulata); new columnals are introduced at the extreme proximal end of the stem.

Sub-order i. Cyathocrinoidea.—Tegmen stout with conspicuous orals. Families: Carabocrinidae, Palaeocrinidae. Euspirocrinidae, Sphaerocrinidae, Cyathocrinidae, Petalocrinidae, Crotalocrinidae, Codiacrinidae, Cupressocrinidae, Gasterocomidae.

Sub-order ii. Dendrocrinoidea.—Tegmen thin, flexible, with inconspicuous orals. Families: Dendrocrinidae, Botryocrinidae, Lophocrinidae, Scaphiocrinidae, Scytalecrinidae, Graphiocrinidae, Cromyocrinidae, Encrinidae (preceding families are Distincta; the rest Articulata), Pentacrinidae, including the recent Isocrinus (fig. 14), Uintacrinidae, Marsupitidae, Bathycrinidae (recent).

Order 2. Flexibilia.—Dicyclica in which proximal brachials are incorporated in the dorsal cup, either by their own sides, or by interbrachials, or by a finely plated skin, but never rigidly; plates may occur between RR. Tegmen flexible, with distinct ambulacrals and numerous small interambulacrals; mouth and food-grooves remain supra-tegminal and open. Top columnal a persistent proximale, often fusing with IBB, which are frequently atrophied in the adult.

All the Palaeozoic representatives have non-pinnulate arms, while the Mesozoic and later forms have them pinnulate. There are other points of difference, so that it is not certain whether the latter really descended from the former. But assuming such a relationship we arrange them in two grades.

Grade a. Impinnata.—Families: Ichthyocrinidae, Sagenocrinidae, and Taxocrinidae, perhaps capable of further division.

Grade b. Pinnata.—Families: Apiocrinidae with the recent Calamocrinus, Bourgueticrinidae with recent Rhizocrinus, Antedonidae, Atelecrinidae, Actinometridae, Thaumatocrinidae (these four recent families include free-moving forms with atrophied stem, probably derived from different ancestors), Eugeniacrinidae, Holopodidae (recent), Eudesicrinidae.

|

| Fig. 14.—A living Pentacrinid, Isocrinus asteria; the first specimen found, after Guettard’s figure published in 1761. |

Order 3. Dicyclica Camerata.—Dicyclica in which the first, and usually the second, orders of brachials are incorporated in the dorsal cup by interbrachials, at first loosely, but afterwards by close suture. IBB always the primitive 5. An anal plate always rests on the posterior basal; mouth and tegminal food-grooves closed; arms pinnulate. Families: Reteocrinidae, Dimerocrinidae, Lampterocrinidae, Rhodocrinidae, Cleiocrinidae.

Class IV. Edrioasteroidea.—Pelmatozoa in which the theca is composed of an indefinite number of irregular plates, some of which are variously differentiated in different genera; with no subvective skeletal appendages, but with central mouth, from which there radiate through the theca five unbranched ambulacra, composed of a double series of alternating plates (covering-plates), sometimes supported by an outer series of larger alternating plates (side-plates or flooring-plates). In some forms at least, pores between (not through) the ambulacral elements, or between them and the thecal plates, seem to have permitted the passage of extensions from the perradial water-vessels. Anus in posterior interradius, on oral surface, closed by valvular pyramid. Hydropore (usually, if not always, present) between mouth and anus. Families: Agelacrinidae, Cyathocystidae, Edrioasteridae, Steganoblastidae. All Palaeozoic. The structure and importance of Edrioaster have been discussed above (figs. 11, 12).

Grade B. ELEUTHEROZOA—Echinoderma in which the theca, which may be but slightly or not at all calcified, is not attached by any portion of its surface, but is usually placed with the oral surface downwards or in the direction of forward locomotion. Food is not conveyed by a subvective system of ciliated grooves, but is taken in directly by the mouth. The anus when present is typically aboral, and approaches the mouth only in a few specialized forms. The aboral nervous system, if indeed it be present at all, is very slightly developed. The circumoesophageal water-ring may lose its connexion with the exterior medium; the podia (absent only in some exceptional forms) may be locomotor, respiratory or sensory in function, but usually are locomotor tube-feet.

The classes of the Eleutherozoa probably arose independently from different branches of the Pelmatozoan stem. The precise relation is not clear, but the order in which they are here placed is believed to be from the more primitive to the more specialized.

Class I. Holothurioidea.—Eleutherozoa normally elongate along the oro-anal axis, which axis and the dorsal hydropore lie in the sagittal plane of a secondary bilateral symmetry. The calcareous skeleton, which may be entirely absent, is usually in the form of minute spicules, sometimes of small irregular plates with no trace of a calycinal or apical system; to these is added a ring of pieces radiately arranged round the oesophagus. Ambulacral appendages take the form of: (1) circumoral tentacles, (2) sucking-feet, (3) papillae; of these (1) alone is always present. The gonads are not radiately disposed.

The comparative anatomy of living forms, combined with the evolutionary hypothesis sketched above, suggests that the early holothurians possessed the following characters: subvective grooves entirely closed; 5 radial canals, proceeding from the water-ring, gave off branches furnished with ampullae to the podia on each side of them, the 10 anterior podia being changed into cylindrical tentacles; the transverse muscles of the body-wall formed a circular layer, probably interrupted at the radii (though Ludwig believes the contrary); longitudinal muscles as paired radial bands, without those special retractors for withdrawing the anterior part of the body which occur in many recent forms; a hydropore connected with the water-ring by a canal in the dorsal mesentery; a gonopore behind the hydropore connected by a single duct with a bunch of genital pouches on each side of the mesentery; gut dextrally coiled, with a simple blood-vascular system, and with an enlargement at the anus for respiration, this eventually producing branched caeca called “respiratory trees”; skeleton reduced to a ring of 5 radial and 5 interradial plates round the gullet, and small plates, with a hexagonally meshed network, dispersed through the integument. Such a form gave rise to descendants differing inter se as regards the suppression of the radial canals and of the podia, the form of the tentacles, and the development of respiratory trees. These anatomical facts are represented in the following classification by H. Ludwig:—

Order 1. Actinopoda.—Radial canals supplying tentacles and podia.

| A. With respiratory trees. | |

| (a) With podia { | Fam. 1, Holothuriidae. |

| Fam. 4, Cucumariidae. | |

| Fam. 5, Molpadiidae. | |

| (b) Without podia | |

| B. Without respiratory trees. | |

| (a) With podia | Fam. 2, Elpidiidae. |

| (b) Without podia | Fam. 3, Pelagothuriidae. |

Order 2. Paractinopoda.—Neither radial canals nor podia. Tentacles supplied from circular canal. Fam. Synaptidae.

|

| Fig. 15.—An Aspidochirote Holothurian of the family Holothuriidae, showing the mouth surrounded by tentacles, the anus at the other end of the body, and three of the rows of podia. |

It is admitted, however, that this scheme does not represent the probable descent or relationship of the families. Consideration of the views of Ludwig himself, of H. Östergren, and especially of R. Perrier, suggests the following as a more natural if less obvious arrangement.

Order 1. Aspidochirota.—Tentacles more or less peltate; calcareous ring when present simple and radially symmetrical; no retractors; stone-canal often opens to exterior; genital tubes sometimes restricted to left side in consequence of altered position of gut (Fig. 15.) Families: Elpidiidae (deep-sea forms, with sub-famm. Synallactinae, Deimatinae, Elpidiinae, Psychropotinae), Holothuriidae (shallow water), Pelagothuriidae (pelagic).

Order 2. Dendrochirota.—Tentacles simple or branched, never peltate; calcareous ring well developed, often bilaterally symmetrical; retractor muscles usually present; stone-canal opens internally; genital tubes in right and left tufts.

Sub-order i. Apoda.—No tube-feet or papillae, but tentacular ampullae more or less developed. Mostly burrowers. Families: Synaptidae (sub-famm. Synaptinae, Chirodotinae, Myriotrochinae), Molpadiidae.

Sub-order ii. Eupoda.—Tube-feet present, but tentacular ampullae rudimentary or absent. Families: Cucumariidae (climbers and crawlers), Rhopalodinidae (burrowers).

Class II. Stelliformia (= Asteroidea sensu lato).—Eleutherozoa with a depressed stellate body composed of a central disk, whence radiate five or more rays; this radiate symmetry affects all the systems of organs, including the genital. The radial water-vessels lie in grooves on the ventral side of flooring-plates (usually called “ambulacrals”); they and their podia are limited to the oral surface of the body and their extremities are separated from the 880 apical plates by a stretch of dorsal integument containing skeletal elements; the opening of the water-vascular system (madreporite) is not connected with a definite apical plate or system of plates.

The starfish, brittle-stars and their allies (see Starfish) have for the last fifty years usually been divided into two classes—Asteroidea and Ophiuroidea, each equivalent to the Holothurioidea or Echinoidea. Recently, however, some authors, e.g. Gregory, have attempted to show that these classes cannot be distinguished. It is true that some specialized forms, such as the Brisingidae among starfish, Astrophiura and Ophioteresis among ophiurans, contravene the usual diagnoses; but this neither obscures their systematic position, nor does it alter the fact that since early Palaeozoic times these two great groups of stellate echinoderms have evolved along separate lines. If then we place these groups in a single class, it is not on account of a few anomalous genera, but because the characters set forth above sharply distinguish them from all other echinoderms, and because we have good reason to believe that the ophiurans did not arise independently but have descended from primitive starfish. For that class Bell’s name Stelliformia is selected since it avoids both confusion and barbarism.