The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Drama of Glass, by Kate Field This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Drama of Glass Author: Kate Field Release Date: November 17, 2010 [EBook #34348] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DRAMA OF GLASS *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

PUBLISHED BY THE

LIBBEY GLASS CO.

The Drama of Glass was an inspiration born in the brain of Kate Field, as she watched the busy workmen, who with trained eyes and skillful hands, wrought out the products of one of America's great industries that found a temporary home in the World's Fair at Chicago.

It is an addition to the long list of brilliant writings of this versatile woman, whose literary labors have made her memory so dear to the thousands of Americans who have found in them the reflection of her own individuality.

The story of an art that is as old as the building of the City of Babylon, that formed a part in the life of Egypt, that was interwoven in the history of Rome, and that[Pg 6] gave a reputation to a nation, is re-told by Miss Field.

From the beginning of the art, wrapped in mystery and legend, step by step her story has become history. She has carried it as far as the World's Fair, and it has devolved upon Mr. Thos. M. Willey to complete what she so well begun.

Have you ever thought what a drama glass plays in the history of the world? It is a drama even in the French acceptation of the word, which infers not only intense action, but death. Can there be more intense action than that of fire, and is not glass the own child of fire and death?

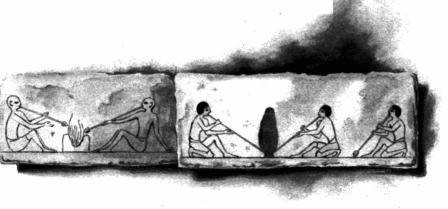

The origin of glass is lost in myth and romance. Nobody knows how it was born, but there are as many traditions as there are cities claiming to be Homer's birthplace. Pliny says that the discovery of glass was due to substituting cakes of nitre for stones as supports for cooking pots.

According to his story, certain Phœnician merchants landed on the coast of Palestine and cooked their food in pots supported on cakes of nitre taken from their cargo.

Great was the wonder of these Phœnicians—the Yankees of antiquity, the builders of Tyre and Sidon, the inventors of the alphabet—on beholding solid matter changed to a strange fluid, which voluntarily mingled with its nearest neighbor, the sand, and made a transparent material now called glass.

This story is too pretty to spoil, and those of us who prefer romance to science will believe it, though Menet the chemist positively declares that to produce such a fluid would require a heat from 1800 to 2700 degrees Fahrenheit. Under the circumstances narrated by Pliny, such[Pg 11] a tremendously high temperature was impossible. Science often interferes with romance, and were not truth better even than poetry, science would be a nuisance in literature.

An art that Hermes taught to Egyptian chemists like good wine needs no bush, yet on its brilliant crest may be found the splendid quarterings not only of Egypt, but of Gaul, Rome, Byzantium, Venice, Germany, Bohemia, Great Britain, and last but not least the United States.

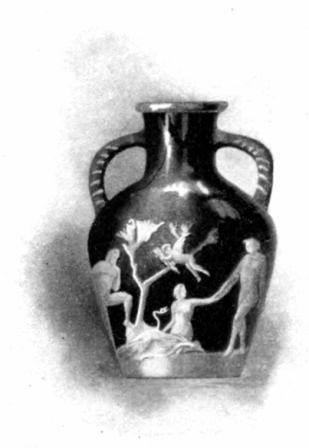

He was a poor man, who, in Seneca's day, had not his house decorated with various designs in glass; while Scaurus, the Aedile, a superintendent of public buildings in ancient Rome, actually built a theatre seating forty thousand persons, the second story of which was made of glass. That[Pg 12] masterpiece of ancient manufacture, the Portland Vase, was taken from the tomb of the Roman Emperor Alexander Severus, and should bear his name rather than that of the Duchess of Portland, who purchased it from the Barberini family after it had stood three hundred years in their famous Roman gallery.

In the thirteenth century Venice reigned supreme in glass making. No one knows how long the City of Doges might have monopolized certain features of this art but for a woman who could not keep a secret from her lover. Marietta was the daughter of Beroviero, one of the most famous glass makers of the fifteenth century. Many were his receipts for producing colored glass, and as he had faith in his own flesh and blood he confided these precious receipts to his daughter. Alas, for poor Beroviero! Marietta, after the manner of women, loved a man,[Pg 13] one Giorgio, an artisan in her father's employ. History does not tell, but I have no doubt that Giorgio wheedled the secret out of his sweetheart.

Once possessed of these receipts he published and sold them for a large sum, then turning on the man he had betrayed he demanded faithless Marietta in marriage. Thus it came to pass that the ignoble love of a weak woman for a dishonorable man helped to change the fortunes of Venice. The world gained by the destruction of a monopoly, one more[Pg 14] proof of the poet's dictum that "all partial evil is universal good."

It was in the middle of this same fifteenth century that a number of Venetian glass makers were imprisoned in London because they could not pay the heavy fine imposed by the Venetian Council for plying their art in foreign lands. "Let us work out our fine," pleaded these victims of prohibition. Their prayer was warmly seconded by England's king, whose intercession was by no means disinterested. Yielding to royal desire, Venice freed these artisans, and thus glass making was established in Great Britain. Beyond the point of reason all prohibitory laws fail sooner or later. Go to the bottom of slang, and as a rule you will find it based on rugged truth. When in the breezy vernacular of this republic a human being is[Pg 15] credited with "sand" or is accused of being entirely destitute of it, he rises to high esteem or falls beneath contempt. Possessing "sand" he can command success; without it he is a poor creature. For the origin of this slang we turn to glass making, the excellence of which depends upon sand.

If Bohemia succeeded finally in making clearer and whiter glass than Venice, it was because Bohemia produced better sand. When the town of Murano furnished the world with glass, its population was thirty thousand. That number has dwindled to four thousand. Bohemian glass stood unrivaled until England discovered flint or lead glass; now, the world looks to the United States for rich cut glass, the highest artistic expression of modern glass.

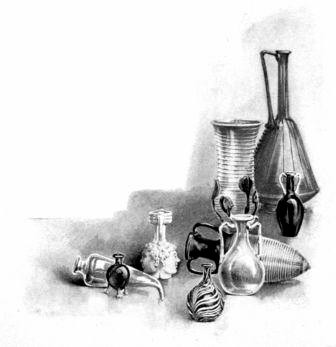

Where does America begin its evolution in glass? Before the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock. In 1608, within a mile of[Pg 16] the English settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, a glass house was built in the woods. Curiously enough it was the first factory built upon this continent. This factory began with bottles, and bottles were the first manufactured articles that were exported from North America.

In those early days glass beads were in great demand. Indians would sell their birthright for a mess of them, so when the first glass house fell to pieces, a second took its place for the purpose of supplying the Indians with beads.

A few years later common glass was made in Massachusetts. It appears from the records of the town[Pg 17] of Salem that the glass makers could not have been very successful, as that town loaned them thirty pounds in money which was never paid back.

During the time of the Dutch occupation of Manhattan Island, when New York was known as New Amsterdam, a glass factory was built near Hanover Square, but not until after the Revolution came and went did glass making really take root in American soil. In July, 1787, the Massachusetts Legislature gave to a Boston glass company the exclusive right to make glass in that State for fifteen years. This company prospered and was the first successful glass manufacturing company in the United States. Then followed others that were successful. As early as 1865 there was manufactured, in the vicinity of Boston, glass that was the equal of the best flint glass manufactured in England. Two hundred and fifty[Pg 18] years from the time the first rough bottles were exported from Virginia to England seems a long time to us, but how short a time it really is in the life of this ancient art—this drama of glass.

It is always interesting to trace the history of a great industry. Like the oak, it begins with a small seed that hardly knows its own mind, and is often more surprised than the rest of the world at the result of earnest effort. See what apothecaries did for Italy. Mediæval art and the Medicis go hand in hand. The drama of glass in the United States may have as significant a mission, for it is singularly true that James Jackson Jarves, son of Deming Jarves, the pioneer glass manufacturer of New England, was almost the first American to give his life to the study of old masters and to[Pg 22] devote his fortune to collecting their works. The Jarves gallery now belongs to Yale University.

William L. Libbey was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and became, in 1850, the confidential clerk of Jarves & Commeraiss, the greatest glass importers of Boston, and whose glass factory in South Boston was the forerunner of the Libbey Works of the Columbian Exposition. Having made a fortune—the fortune his clever son spent in art and bric-a-brac—Deming Jarves sold his glass factory to his trusted clerk in 1855, and for twenty years this Massachusetts industry gained strength and reputation. But the trend of population was westward.

Cheap fuel was necessary to successful glass making. How could New England coal compete with natural gas? So Ohio came to the front. A few years ago Ohio's natural gas became exhausted. Without a day's disturbance petroleum[Pg 23] succeeded gas, and better glass was made than ever, because oil produces a more even temperature. Verily "there is a soul of goodness in things evil." From Massachusetts to Ohio, from coal to gas, from gas to petroleum, what would be the next act in the drama of American glass? What, indeed, but an act the scene of which was laid in the grounds of the World's Fair!

Believing fully in the westward course of empire, Mr. Edward D. Libbey had the inspiration that if Chicago wanted the World's Fair, Chicago would not only have it, but would create such an exposition as had never been seen. So before even the temporary organization was formed in Chicago the Libbey Glass Company filed an application for the exclusive right to manufacture glass at the Columbian Exposition.

The problem of erecting a building that should be architecturally[Pg 24] in keeping with the surroundings, that should afford every possible comfort to the thousands of daily visitors and still be used as a manufactory, was not an easy matter.

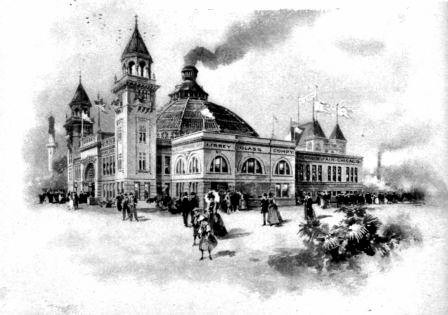

Begun in October, 1892, the admirable building, put up in the Midway Plaisance to show the process of making glass, was finished one week before May 1st following. On that bleak opening day thousands of overshoes were stalled in mud a foot deep before the Administration Building, and the owners went home in some cases almost barefooted.

But there was an expenditure of $125,000 in an idea, and the investors had no reason to fear[Pg 25] weather or neglect. From the opening to the closing of the big front door two million people found their way to this glass house, at which no one threw stones. The trouble was not to get people in, but to keep them out. A mob never benefits itself nor anybody else. To reduce the attendance to reasonable proportions a fee was charged, applicable to the purchase of some souvenir, made perhaps before the buyer's very eyes. Why was this glass house so popular? Because its exhibit displayed the only art industry in actual operation within the Fair grounds.

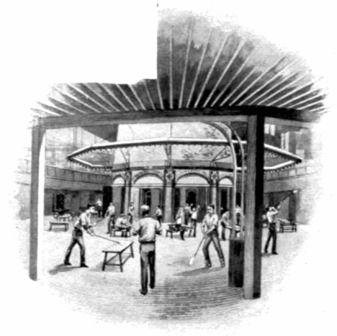

All people like machinery in motion, and the most curious people on earth are Americans. They want to know how things are made, and, like children, are not content until they have laid their hands on whatever confronts them. "Please do not touch" has no terrors for them. In addition to this inborn love of action, there is a fascination[Pg 26] about glass blowing and the fashioning of shapeless matter piping hot from the pot that appeals to men and women of all sorts and conditions. With eyes and mouths wide open, thousands stood daily around the circular factory watching a hundred skilled artisans at work. They looked at the big central furnace, in which sand, oxide of lead, potash, saltpetre and nitrate of soda underwent vitrification; they saw it taken out of the pot a plastic mass, which, through long, hollow iron tubes, was blown and rolled and twisted and turned into things of beauty. Here was a champagne glass, there was a flower bowl; now came a decanter, followed by a jewel basket. A few minutes later jugs and goblets and vases galore passed from the nimble fingers of the artisans to the annealing oven below.

All these creations entered the oven as hot as they came from the last manipulator, but gradually[Pg 27] cooled off to the temperature of the atmosphere. Getting used to the hardships of life requires twenty-four hours, during which the trays on which the glass stands are slowly moved from the hot to the temperate end of the oven. This procession was an object lesson in life as well as in glass. "Make haste slowly or you'll defeat yourself," was the burden of the song those things of beauty sang to themselves and to all who listened.

If American cut glass has grown beyond compare, it is largely due to the superior intelligence of American artisans. They have the "sand": so, too, have the beautiful hills of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, whence comes the purest quality the whole world has known. The best flint glass exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1867 owed its excellence to the treasure stowed away in Western Massachusetts.

The finest American flint glass of[Pg 28] the Columbian Exposition found its inspiration in the same part of the old Bay State.

Little did those visitors to the Fair know whence came the hot fires of Libbey's Glass House. They little knew that oil was drawn in pipes from Ohio, and that one hundred and fifty barrels of petroleum lay buried under innocent-looking grass, that looked up and asked not to be trodden under foot.

Of course, had lightning struck those two great hidden tanks of liquid dynamite, we should all have been sent to that bourne whence no World's Fair visitor could have returned.

Seventy-five barrels of oil were burned daily on the Midway Plaisance. How many gallons? Three thousand. Multiply one day's fire by one hundred and eighty days and you discover that the drama of glass at the Fair was the death of fifty-four thousand gallons of petroleum.[Pg 29]

Ever since the era of fairy tales the world has heard of glass slippers. Cinderella wore them and great was the romance thereof. But whoever before 1893 heard of a glass dress, and who conceived such a novel idea?

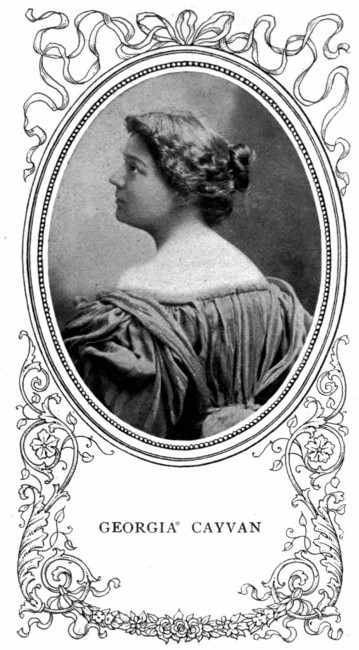

From that memorable day in the Garden of Eden when Eve ate that apple, which may literally be called the fruit of all knowledge, woman has been at the bottom of everything: it was a woman who got it into her head that she wanted a glass dress. How did it happen? Thus: In the middle of May, 1893, women from all parts of the earth took Chicago by storm. Theirs was the first of one hundred congresses, and among[Pg 32] many artists was Georgia Cayvan, whose record on and off the stage does credit to her head and heart. Of course the clever actress visited the Fair and of course she followed the multitude and found herself watching the process of making American glass. It was not long before Miss Cayvan's quick eye was attracted by an exhibit of spun and woven glass lamp shades.

"Do you mean to say those shades are spun out of glass?" she exclaimed; "the material resembles silk."

"Nevertheless it is glass," replied the attendant.

"Is it possible to make a glass dress?"

"Why not? It is not only possible but eminently feasible."

"Would it be very expensive?"

"Twenty-five dollars a yard."

This was a deal of money to invest in an experiment,[Pg 33] as at least twelve yards are needed for a gown, but when a woman wills she wills, especially when she is intimately acquainted with her own mind. Miss Cayvan knows hers perfectly, and in a few minutes she exacted from the Company a promise not only to spin her many yards of glass cloth for a white evening costume, but she obtained from them the exclusive right to wear glass cloth on the stage. "It is agreed," said actress and manufacturer in chorus, and off hied the former to New York, where at the end of four weeks she received her material direct from the Midway Plaisance. How to make it up was the next question, for Madame la Modiste vowed she wouldn't touch such material with scissors and needles.[Pg 34]

As a matter of fact a specialist is needed to cut and sew glass, which differs from other cloths in breaking and wickedly sticking into the hands, so a skillful and artistic young woman employee from Toledo was sent to New York to do what the ordinary seamstress could not. She cut and made the unique costume with which Miss Cayvan sweeps the stage to the edification of feminine and the wonder of masculine eyes.

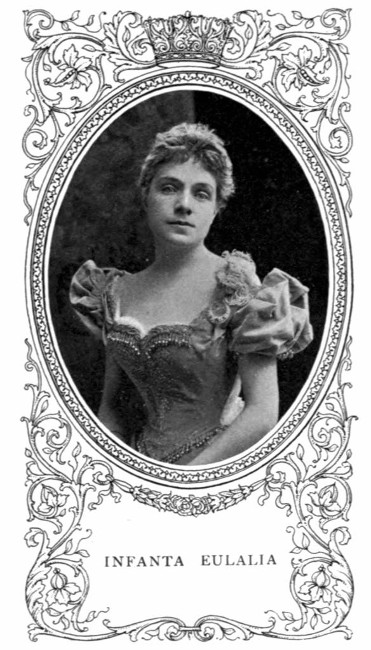

The fame of that glass gown reached the ears of the Infanta Eulalia, who saw it worn by the ingenious actress and determined to inspect its counterpart set up in a case at the World's Fair. The Midway Plaisance was the Princess's favorite resort in Chicago, and she soon turned her steps toward the glass house she had heard so much about. "Where's that dress?" asked the Infanta as she entered the factory. On being conducted to it Eulalia expressed great pleasure, declaring it was the finest thing she had seen at the Fair.

"Would Your Highness wear such a gown were one made expressly for you?" she was asked.[Pg 36]

"Not only would I wear it, but I'd take the greatest delight in telling the story of its manufacture," replied the Princess.

Before sailing away to Spain, Eulalia was fitted for her American glass gown, now wears it, and today there hangs in the Libbey Glass Company's private office the following official certificate:

Royal House of H. R. H. Infante Don Antonio de Orleans

H. R. H. Infante Antonio de Orleans appoints Messrs. Libbey and Company of Toledo, Ohio, cut-glass makers to his royal house, with the use of his royal coat-of-arms for signs, bills and labels. In fulfillment of the command of His Royal Highness I present this certificate, signed in Madrid, July 15th, 1893.

Pedro Jover Fovar

Superintendent of His Royal Highness's Household

Thus for the first time in the history of an industry almost as old as humanity, glass adorns alike the person of a Royal Princess and the person of a charming actress. Produced at the Court of Spain and on the American stage, am I not justified in calling this memory of a far and near past "The Drama of Glass"?

Kate Field

[Pg 37]

In every story told of the sights worth seeing at the Columbian Exposition the factory of the Libbey Glass Company, of Toledo, Ohio, has had an important part. It was more than a mere exhibit; it was a practical education in the art of glass making, which, like an easy lesson that follows step by step, from the mixing of the crude material to the completion of the finest piece of cut glass, impressed itself upon the minds of hundred of thousands of visitors.

Recall in your memory your visit to the World's Fair in 1893. Place yourself[Pg 40] upon the Midway Plaisance, directly opposite the Woman's Building. Does your mind picture a stately, beautiful building, with central dome and graceful towers? This was the building of the glass factory to whom the exclusive right to manufacture and sell its products was awarded over many competitors by the Ways and Means Committee of the World's Columbian Exposition. This concession was given because the plan of the Libbey Glass Company was a plan of broad ideas, fully meeting the requirement that America should show that the whole world followed her in the manufacture of cut glass.

How well that Company fulfilled its mission is known to the two million visitors who passed under the deep-recessed semicircular archway, rich with sculptured ornament, that covered the grand entrance to this palace; within, it was like a theatre, where the scenes in the[Pg 41] beautiful drama of glass were ever changing. Do you remember that the sides, the dome, the ceiling, were all glitter and sheen with the products of this mystic art, and that from thousands of cut-glass pieces, as from brilliant diamonds, sparkled the prismatic hues?

Do you remember the roaring furnace a hundred feet high, the melting pots made of the clays of the Old and the New Worlds, mixed by the bare feet in order that they have the requisite consistency? The products of this factory were born of fire. The plastic molten mass that came from the melting furnace, with its heat of 2200 degrees Fahrenheit, was thirty hours before a mixture called by glass makers a "batch," whose chief ingredient was sand from the hills of Massachusetts.

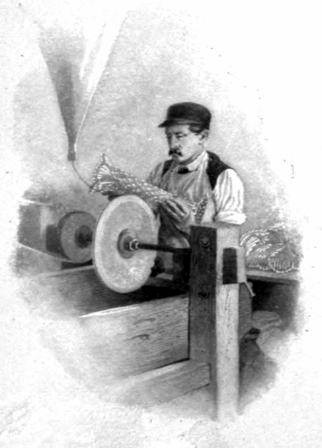

Did you watch the workmen—the "gatherer" and the "blower," with their long, hollow iron pipes? How the "blower," with his trained[Pg 42] fingers, gave an easy, constantly swaying motion to the pipe, into which he blew and expanded the hot glass at its end? The tempering oven, through which all glass productions must pass before they will resist changes in temperature or even stand transportation? Did you follow the process of cutting glass; see the wheels like grindstones, driven by steam power? Wheels of stone that come from England and Scotland, and carry with them the old-country names of Yorkshire Flag, New Castle and Craigleith, stones that are very hard and close-grained, capable of retaining a very sharp edge? Wheels of iron, which are used to cut the design in the rough; wheels of wood, cork, felt, and revolving brush wheels, used in finishing and polishing? Did you know that the trained eye of the cutter and his experience were the only guides he had to secure the requisite depth to his cutting; that he must exercise[Pg 43] great care and judgment, else the vibration of the glass renders it extremely liable to break, and that an intricate design requires many days of constant manipulation?

Did you watch with interest the making of glass cloth, see how the thread of glass was drawn out and wound on the big wheels that revolved hundreds of times a minute? How the glass thread was woven with the silk thread, producing a pliable glass cloth of soft sheen and lustre, that could be folded, pleated and handled in all ways like cloth?

Do you recall the Crystal Art Room? Did you realize that under that ceiling, bedecked with ten thousand dollars' worth of spun glass cloth, was collected the finest display of cut glass the world had ever seen? Do you remember an old glass punch bowl, used in 1840 by Henry Clay, and that near this relic of ancient glassware was another[Pg 44] punch bowl upon which five hundred dollars' worth of labor had been bestowed?

Did you mark the difference, the deep and brilliant cuttings, how effective they were, how they brought out the beauty and richness of the design? Then, when you examined the hundreds of other articles, the sherbet and punch glasses in Roman shapes, the quaint decanters in Venetian forms, the celery trays, flower vases, and the ice-cream sets and cut-glass dishes for every use, you saw the clearness of the glass itself, and that this deep and brilliant cutting of perfect design, that brought out the beauties of the[Pg 45] great punch bowl, was a marked characteristic of the Libbey Cut Glass. Did you not, as an American, feel proud of the progress that your countrymen had made in this old art of glass making?

Since the World's Fair at Chicago, two expositions of the industries of this country, the San Francisco Midwinter Fair and the Atlanta Exposition, have added to the honors and reputation of the cut glass of the Libbey Company. Certain trade-marks and names on silver and china are always looked upon with pleasure and with a feeling that the possessor has the genuine article.

The same thing applies to cut glassware, so as a protection to the public against those who would profit by the reputation of others, the Libbey Glass Company cut their trade-mark—the name Libbey with a sword under it—upon every piece of glass they manufacture.[Pg 46]

Half a century in the life of America has added much to the art upon whose brilliant crest, as Miss Field has said, may be found the splendid quarterings of Egypt, Rome, Venice, Germany and Great Britain, and today the United States stands unrivaled in the manufacture of cut glass.

The honor conferred upon the Libbey Glass Company by the committee, in granting to them the exclusive concession to manufacture and sell American glassware within the grounds of the Exposition during the World's Fair, was a great one.

The honors conferred by the San Francisco and Atlanta Expositions are but added proofs that the selection was a proper one. The Libbey Glass Company thus stands today to represent the best the United States produces in cut glass, and the best the United States produces is the world's best.

Bartlett & Company

The Orr Press

New York

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Drama of Glass, by Kate Field

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DRAMA OF GLASS ***

***** This file should be named 34348-h.htm or 34348-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/3/4/3/4/34348/

Produced by Chris Curnow, Josephine Paolucci and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.