DESIGNED AND ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR GODEY'S LADY'S BOOK.

DESIGNED AND ENGRAVED EXPRESSLY FOR GODEY'S LADY'S BOOK.

Project Gutenberg's Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. XLII., May 1851, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Godey's Lady's Book, Vol. XLII., May 1851 Author: Various Release Date: September 23, 2010 [EBook #33983] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GODEY'S LADY'S BOOK, MAY 1851 *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Rose Koven, Emmy and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net Music by Linda Cantoni

| A Hindoo Belle, by J. E. P., | 322 |

| A Spring Carol, by Mrs. A. A. Barnes, | 326 |

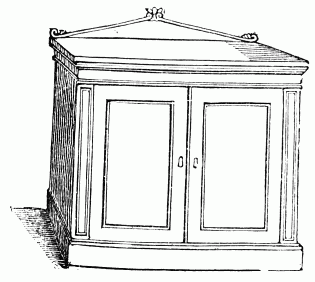

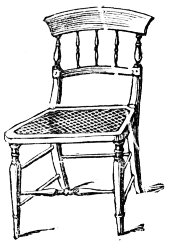

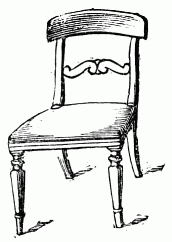

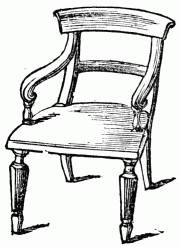

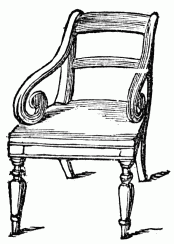

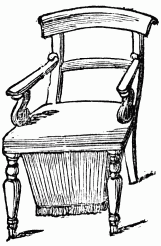

| Cottage Furniture, | 329 |

| Develour, by Professor Charles E. Blumenthal, | 51, 102, 182, 257, 323, 377 |

| Editors' Table, | 65, 134, 201, 266, 330, 391 |

| Editors' Book Table, | 66, 135, 202, 267, 332, 392 |

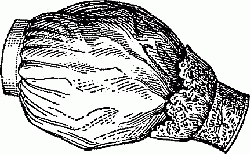

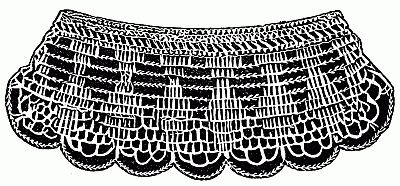

| Etruscan Lace Cuff, | 328 |

| Fashions, | 70, 140, 205, 270, 336, 396 |

| Flowers, by G. H. Cranmer, | 284 |

| Garden Decorations, | 251, 282, 372 |

| Good For Evil, by Angele de V. Hull, | 252, 285 |

| Home; or, the Cot and the Tree, by Robert Johnson, | 295 |

Incidents in the Life of Audubon, by the author of "Tom Owens, the Bee Hunter," | 306 |

| Knitted Flowers, | 61, 199, 263, 328, 386 |

| Model Cottages, | 4, 126, 283 |

| Moral Courage, by Alice B. Neal, | 316, 367 |

| Publisher's Department, | 269, 334, 394 |

| Sonnet, by Mrs. L. S. Goodman, | 281 |

| Sonnets, by William Alexander, | 42, 75, 169, 215, 277, 390 |

| Spring, by Fanny Fales, | 292 |

| Spring—a Ballad, by Mary Spenser Pease, | 278 |

Susan Clifton; or, the City and the Country, by Professor Alden, | 29, 93, 170, 246, 302, 360 |

| Taking Care of Number One, by T. S. Arthur, | 320 |

| The Judge; a Drama of American Life, by Mrs. Sarah J. Hale, | 21, 88, 154, 237, 298 |

| The Language of Flowers, by Jno. B. Duffey, | 277 |

| The Last of the Tie-Wigs, by Jared Austin, | 296 |

| The Tiny Glove—a May-Day Story, by Blanche, | 280 |

| The Young Enthusiasts, by Frank I. Wilson, | 309, 346 |

| To A. E. B., or Her who Understands it, by Adaliza Cutter, | 297 |

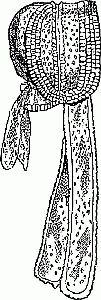

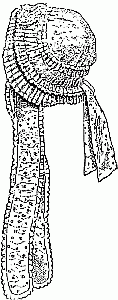

| Undersleeves and Caps, | 327 |

| Various Useful Receipts, | 69, 139, 205, 270, 335, 396 |

| Women of the Revolution, by Mrs. E. F. Ellet, | 293 |

| Ye Come to me in Dreams, by Nilla, | 279 |

Bright, gladsome May-day!—the fairest maiden in all the train of the merry "Queen of Seasons." May-day! what happy scenes this word recalls—the day of all days for childhood's pleasures! I see the little darlings tripping along the streets of my native town with baskets on their chubby arms, smiles on their lips, and happiness in their eyes, soon clustered in merry groups on some favorite spot in the suburbs, laughing and chatting, arranging their pic-nic dinners, or sporting beneath the shady trees.

But to my story. A mile or two from the village of A. were collected some fifty or sixty little girls and boys, for the purpose of celebrating their annual holiday. The May-pole, bedecked with flowers of every hue and form, towered aloft, and around its base they frisked and gamboled like so many little fairies. Some were "wafted in the silken swing" high up among the boughs of the beech and elm; others sought the brink of the rippling rivulet, and amused themselves with ruffling its smooth surface or looking at their mirrored faces. Far down the streamlet, and alone, was quietly seated a little girl, weaving into garlands the buds and blossoms which grew around her in wild profusion, caroling with a bird-like voice snatches of some favorite air, ever and anon raising her violet eyes and looking round her in wondrous delight. Her childish face was strikingly beautiful; around her small perfect mouth there rested an angel smile, and her short brown curls were parted on a forehead of matchless contour.

She wove and sang, and smiled a sunny smile, and seemed wholly unconscious of a pair of bright black eyes fixed upon her from the opposite bank. At length she turned, as if to listen; and soon upon the air floated distinctly sounds of "Alice! little Alice!" and she bounded away to her playmates. No sooner had she disappeared than the owner of the black eyes—a boy, seemingly of twelve years, clad in a green jacket ornamented with silver buttons, loose white trowsers, and wide-brimmed straw hat, which but partly concealed his glossy black hair—sprang across the water and possessed himself of the tiny glove which lay forgotten on the bank, and which had once covered the hand of "little Alice."

"Alice, my dove, you have brought but one glove from the May frolic."

"I lost the other one yesterday. I don't think I forgot it May-day, mamma."

"Well, dear, go put this one away until you find the mate."

"Yes, mamma."

'Tis night in a boarding-school. The doors of many small rooms open on the dreary hall, and the glimmering light through the key-holes tells of the fair students within. One is partly open, and through it we see two young girls standing near a toilet: one is drawing a comb through a mass of rich brown curls, which stray in playful wantonness about her snowy shoulders. The other is rummaging amid the elegant trifles which decorate the table.

"Alice," she began, "many, many times have I seen this beautiful little glove among trumpery, and often thought I'd beg of you its history, but always forgot it. Tell me now whose hand it once imprisoned."

"Mine, Kate, mine. When a little child of eight years old I lost the fellow, and put this one away until I should find it. Years have rolled away; but it speaks so eloquently of a happy May-day I then enjoyed, that I have never been able to part with it, and still treasure it as an index to the bright scenes of the past."

Again I beg the reader to pass over two years—short to you who possess health and plenty, long to those in disease and want—and come with me to the heights of the Alleghanies, crowded with stately trees all covered with snow and ice, with here and there thick clambering evergreens, looking all the richer for their bright unsullied winter caps. Slowly and laboriously do the wheels of a heavy traveling carriage wind along the rugged ascent, while the heaving flanks and dilated nostrils of the noble steeds bear witness to the toilsome pathway. Muffled in cloaks and furs, we scarcely recognize, in the inmates of the coach, our two school-girls, lately emancipated from their narrow cell and the thraldom of school-laws. We would willingly linger to admire with them the grandeur and sublimity of these props of heaven; but we will not attempt a description of that which was among the mightiest works of Him, the Almighty; so we pass over the perilous and impressive journey, nor pause until, again in her own village, again on the steps of her dearly loved home, Alice Clayton is pressed to her mother's bosom.[281]

Now under her father's roof, she has become the glad child again. We see her first with her companion, Kate Earle, wandering about the spacious drawing-rooms, now tastefully arranging the folds of the heavy satin curtains, or decorating the tables with rich bouquets; then trying the full, clear tones of the piano; and at last, taking a delighted survey of the whole, she trips away into the long dining-hall, contemplates a moment the iced pyramids, foamy floats, transparent jellies, &c., then, arm in arm, they seek their chamber, and are soon busily engaged in the witching duties of the toilet.

Night hurries on, and the cold moon looks calmly down the quiet village: but soon, no longer silent, we hear quickened foot-falls, rolling carriages, the hum of busy tongues, and occasionally a silvery laugh floats out upon the cool night air. Before the stately, and now brilliantly-lighted, mansion of Mr. Clayton they pause, ascend the steps, and are lost to view. But we will enter and look upon the happy throng assembled here to welcome back their former playmate, sweet Alice Clayton. Ah, how tenderly she greets them! Now do her soft eyes light up and flash with intense joy as she receives her numberless guests with unaffected grace, presenting many to her visitor, Kate Earle. The music and the dance begin, youth and beauty eagerly join the circle, while the older ones retire to the whist-tables, none marking the speedy flight of the rosy hours. Some are there, strangers to the fair idol of the brilliant concourse: one of these, a youth of striking mien and unusual elegance, is now seeking a presentation from her father. With a good-humored smile, he bows assent, and together they seek our heroine.

"Come, Alice dear, make your prettiest bow to my young friend, Percy Clifford." Then, in a mock whisper, he added, "Guard well your heart," and left her, smiling maliciously at the painful blushes which his remark had summoned to her cheeks.

However, the low, easy tones of Clifford's voice soon reassured her, and a half hour glided away so pleasantly that her father's warning was forgotten, or, if remembered, but too late. I don't mean to say that Alice really gave her heart away before the asking; but that night when she and Kate were repeating the sayings and doings of their late guests, Percy Clifford's name was oftener on her lip, and when, with arms entwined, they slept the sleep of innocence, Perry Clifford's musical voice and captivating smile alone hovered round her pillow.

Again and again they met; already had the finely-modeled features of Alice Clayton gained an indescribable charm from the warm feelings of her pure, ardent heart, which sprang up irresistibly to the surface. No wonder that Percy Clifford yielded to the idolatrous affection which grew and strengthened in his bosom for the fair girl. No wonder that his passion knew no restraint when he pressed his lips on her innocent brow, and drew in his clasp Alice, his betrothed.

"My sweet Alice!—my 'little Alice;' for so I love to call you. The dear name recalls the little brown-haired beauty who sat upon the bank weaving into garlands the bright flowers, none half so lovely as herself, while from the depths of her gentle heart gushed out a song as witching and melodious as the carolings of all the feathered tribe. Then, a boy, did I first gaze enraptured on your infantile beauty; then did my heart unclose to the lovely vision which it has since treasured through years and absence, joy and sorrow. My father always granted my request to prosecute my studies at his country seat near A., and, unknown, unnoticed, I followed you through girlhood, and experienced my first pang when you left me for the distant seminary.

"None can tell the overwhelming sorrow, the keen agony which succeeded your absence; my only solace was to seek the streamlet and mingle my boyish tears with its limpid waters. Again I met you; and I have since wondered how I could so well act the stranger—how I could speak so calmly when my heart was bursting. Soon all doubts and fears were banished—you loved me! I saw it in the tearful eye, the flickering cheek. And now, Alice, dearest one, you are mine! With this, you see this little glove. It will tell you how you have always reigned, as now, in the heart of Percy Clifford."

And how can I describe her joy as, half laughing, half crying, she kissed again and again the little wanderer, and how that night she placed it mated in his hand, emblem of themselves?

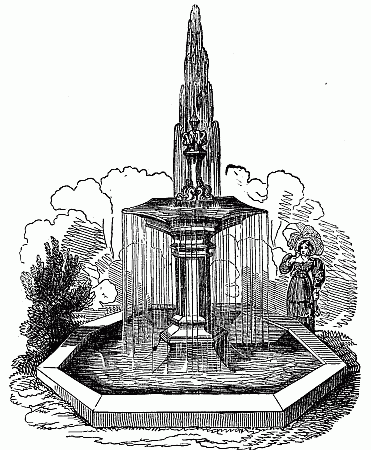

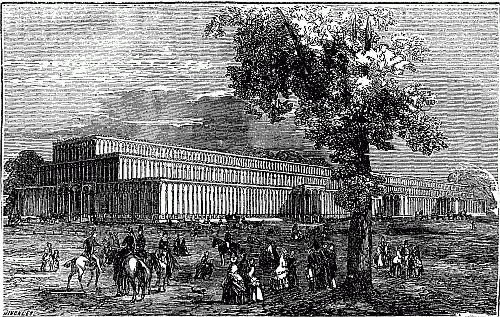

In the present number of the Lady's Book, we give a style of fountains somewhat different from that given in our last.

Should the house be in a style suitable, a drooping fountain, like that shown in the engraving, may be used; and the central part may be altered to suit a Gothic or an Elizabethan house.

Whatever pattern may be adopted, there are certain rules to be attended to in the construction of all fountains, in order to make them play. A fountain may be formed wherever there is either a natural or artificial supply of water some feet higher than the level of the surface on which the fountain is to be placed. This supply of water is called the head, and its height varies according to circumstances. Where a drooping fountain is to be adopted, the head need be very little higher than the joint from which the water is expected to issue; but where the fountain is to form a jet, the head must be six inches, a foot, or more, higher than the height to which the jet is expected to rise; the height required varying according to the diameter of the jet. When the jet is small, say about the eighth of an inch in diameter, the height of the head above that to which the jet of water is expected to rise need not be above six or eight inches.

In the mountainous parts of the country, ornamental fountains may be constructed with very little trouble or expense. The water which flows from springs in hill-sides may be made to form the head. It may be conducted to the fountain through leaden or earthen pipes, or pipes made of any material that is perfectly water-tight. If these pipes be extended to the door of the dwelling, excellent water may be at all times available—thus answering the double purpose of ornament and use.[283]

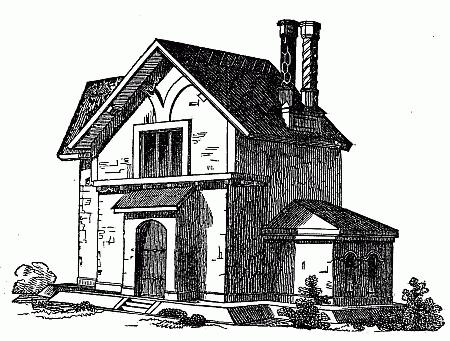

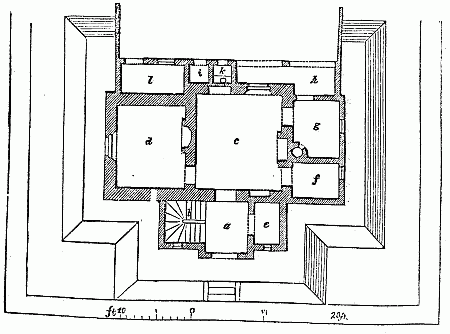

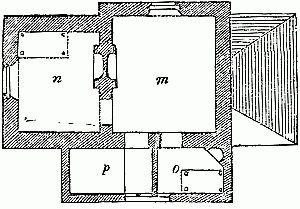

This cottage contains, on the ground floor, an entrance lobby, a; staircase, b; kitchen, c; parlor, d; tool-house, e; pantry and dairy, f; back-kitchen, g; wood-shed, h; dust-hole, i; water-closet, k; and cow-house, with brew-house oven, l.

The cow-house is connected with a court-yard, which contains a shed for hay and straw, piggeries, with a manure-well connected with the water-closet. The platform, on three sides of this dwelling, forms a handsome walk, from which there is a door into the court-yard.

The bed-room floor contains a best bed-room, m;[284] a second bed-room, n; a third bed-room, o; and a stair, p.

General Estimate.—14,904 cubic feet, at 10 cents per foot, $1,490.40; at 5 cents, $745.20.

What a volume of thought and feeling is contained in the simple flower! As the lightnings which flash along the firmament of heaven, or the thunders which startle the silence of eternity, are typical of His anger and might—so are the beauty and simplicity of a flower typical of His purity and mercy.

A flower is no insignificant object. It is fraught with many a deep though mute lesson of wisdom. It teaches us that even itself, the brightest ornament of the vegetable world, must fade away and die—and the life which we prize so highly may be seen, as in a mirror, through its different changes.

The withered leaflet is like unto a crushed and broken heart. Its fading loveliness is like the approach of age as it throws its mantle of wrinkled care over the form of some lovely specimen of humanity. Its sweet fragrance is like the joys and pleasures of our breasts ere they have been contaminated by the rude touches of the world.

The dew-drop which, at morning's dawn, rests upon the half-oped bud, is like the tear which dims the infant's speaking eye when his childish glee has been reproved by the voice of affection.

A flower represents mankind in the changes of infancy, youth, manhood, and old age. The young bud is infancy; the bursting flower is youth; the flower full blown is manhood, and the withered and tailing leaf is the type of old age.

Its uses are various and manifold. Sometimes the promptings of affection lead us to place it, in its purity and beauty, over the tomb of some beloved friend, where, shedding around its fragrance, it steals upon our senses like the memory of the departed being beneath. Sometimes the hand of pride will pluck it from its stem, to deck the hair of the blooming bride, or add by its odor to the festive scene. And not unfrequently it is the mute bearer of some fond tale of love to the ecstatic sense of her whose heart and feelings are at length justified, by its sweet language, in the thoughts they so long have harbored. It soothes the cares of the troubled soul, and alleviates the pangs of sorrow. It wins upon us by its modest though blooming appearance, and its gentle influence steals into our bosoms and softens our natures.

Study the flowers, and behold the wisdom, the goodness, and mercy of the Almighty. Anatomize them, and behold the innumerable parts which form and make up the whole, and the system and order with which they are joined together.

Refinement dwelleth among the flowers. There the affections of our hearts are given license to rove, and there the enthusiasm of our nature overcomes the diffidence of our feelings. Voluntary homage arises to the Maker of objects so fair and beautiful, and the soul in the contemplation sighs itself away in a delicious reverie. Not less beautifully than truly has it been said:—

Their new home was a little bijou of a cottage, and Cora went to work with a light heart. The furniture was of the very plainest kind; but about the little rooms there was an air of comfort and refinement that told of a woman's careful hand. Here and there hung pictures of her own painting. In each apartment were one or two shelves, neatly stained and varnished, on which were placed a few choice books. On the top stood the nicely-trimmed lamp—thus making feminine ingenuity serve the double purpose of library and bracket. The little octagon work-table, in one corner, held a porcelain vase, daily ornamented with fresh flowers, for in the sunny South the flowers bloom perpetually; and the white counterpane on the small French bedstead in Cora's "spare room," tempted one to long for an invitation from her sweet self to occupy it. How proud and happy her husband felt as together they took their first regular meal after the confusion was over, and Cora's housekeeping began in good earnest!

A few weeks afterwards, she received a box containing her mother's old-fashioned but costly set of China—and her tears fell fast and thick as she looked once more on the well-known cups her childish lips had so often pressed. No gift could have been so precious in her eyes, and she kissed the souvenir of her early days with reverence. Many little trifles had the good mother added to the welcome present—trifles that Cora could not buy, because she could not afford it; and her heart yearned towards her only parent, as she uncovered one after another of the home treasures. An antique-looking silver coffee-pot, with cream-jug and sugar-bowl, made Cora's little table look like the most recherché in the land. Had Laura seen it, she would have cried with spite; for, now that she had driven her sister-in-law from the house, the remembrance of her own cruelty and injustice made her hatred more bitter still. She had but one wish, and that was to see her brother and his innocent wife in actual want!

Even in the street poor Cora was not safe from her violent rage. If by chance they met, Laura's eye would flash, her cheeks grow pale, her lips quiver, and she would pass, followed by Clara and Fanny, with a look of scorn and gesture of defiance, which they would endeavor to imitate as closely as they could, as a token of respect to their now wealthy sister. Their father had long repented of his unkindness, but his weak mind bent to that of Laura; and so they were as strangers—they who should have been as closely united as God had made them! To Lewis they made professions that disgusted him; but, at Cora's request, he still paid Mr. Clavering the respect of calling occasionally. It was an unhappy state of things indeed; but heartless, worldly people have no ties, and easily sever the closest, should they bind inconveniently; so it cost Laura and her sisters neither pang nor remorse to outrage a brother's feelings. Margaret yearned towards Cora, and, as often as she saw her, expressed the same unchanging affection, but dared not openly avow her regret at her absence.

One day, as Cora sat in her room plying her needle, she heard some one enter the back gate. In a moment Maggie was in her arms, weeping and laughing by turns. She had stolen away, and came to spend the whole day.

"Darling Maggie!" said Cora, kissing her again and again, "how kind of you to come! Lewis will be so happy, too!"

"Ah, Cora!" replied Margaret, untying her bonnet, "if you knew what a time I had to get here! We were all invited out to dinner; I positively refused to go—having laid my plans for you, sweetest! Laura was so ill-humored, and the others so intent upon themselves, that they did not remark my eagerness to remain. But they insisted on my going, until I suggested that the carriage would not hold us all, large as it is, and so they drove off to Rivertown in grand style, leaving me at length alone. I danced with joy! I almost screamed. But I kept quiet enough till T knew they were not going to return for some odd glove, a handkerchief, or Fanny's eternal powder bag, and then started off."

"This shall be a jour de fête, then, my own Margaret; and I will put up this work to show you my sweet little home. Oh, Maggie!" continued Cora, clasping her hands, "were it not for the indifference of your father and sisters to my poor Lewis, I would be the happiest woman on the wide earth. He deserves so much affection, for he has given his own so earnestly."

A few tears fell from her eyes, but she brushed them away and smiled again. Margaret sighed, but was silent. This was a subject upon which she never conversed, from her decided disapprobation of the course adopted towards two beings so dearly loved. She remembered, with bitterness and trembling, the thirty-sixth verse of the tenth chapter of St. Matthew: "For a man's enemies shall be they of his own household," and pondered deeply over the means of reconciliation. But to-day she had determined to be happy, and Cora was delighted[286] at her open admiration of their little ménage. The China and silver particularly charmed her—first, with their beauty; and secondly, with the air of luxury they gave her brother's modest table. They were moreover, articles of real value that were Cora's, no matter what the contingency; and Margaret's gentle heart rejoiced at what she termed "their first piece of luck."

How these two chatted! How they valued each moment of the time allowed them! Maggie drew out her thimble and insisted upon being employed, and the hours flew lightly over their heads until noon, when Lewis entered.

"Maggie!" he cried, as she flew out from behind the door where she had concealed herself. "This is indeed a pleasure."

This affectionate greeting made her burst into tears; and she held her head, for a few moments, against his breast.

"How kind of you, dear sister, to brave all, and come to us at last! I wish it were for ever; but we are such ungrateful mortals that we never rest satisfied with present blessings. You have been happy to-day, darling," continued Lewis, as Cora entered. "I can tell that by looking at you."

"Ay, Lewis, as merry as a cricket ever since Maggie came before me, like a good angel, this morning. Do get the girls to go out and spend the day again, my own pet sister, and gleam on Lewis and me before we begin to pine again for one of your soft kisses.".

"I wish you could put me in a cage, like a stray bird," said Margaret, with a smile of love. "I think I should like a jailer like Cora, and be content to stay captive for ever."

But, alas! dinner was over, and they had only the afternoon left them. Maggie remained until it was nearly dusk, that she might get an early cup of tea from Cora's pretty China; then, with Lewis and his wife at her side, sauntered slowly home. The tears sprang into her eyes as she bade them adieu, and she had just rung the bell when the carriage containing her sisters drove up the street. Fortunately, it was too dark for them to recognize her companions, and she succeeded in getting rid of her bonnet and mantle before they had managed to get out, as Laura insisted upon being carried in the parlor by poor Mr. Phillips, because he had taken, at dinner, a little more wine than was positively good for him. But he succeeded, in despite of occasional glimpses of two wives, four sisters-in-law, and two Mr. Claverings. Laura was placed on a sofa, where she lay until after the tea tray was carried out, and then, calling her husband once more, desired to be taken to her room.

Fanny and Clara sat discussing the dinner, the furniture, and the guests, and both seemed rather out of spirits. The old gentleman walked up and down the piazza, thinking deeply, and Margaret alone looked fresh and happy.

"Who was there, Fanny?" asked she, at length.

"Oh, a stupid set! Excepting ourselves and Mr. and Mrs. Denton, there was not a decent creature there. Nearly all married people and old bachelors. I declare, I have no patience with such incongruous assemblies!"

"There was Mrs. Hildreth's brother! He is quite a beau, I'm sure; and Clara expressed unbounded admiration of his mustaches and whiskers a few days since."

"Yes, he was there, and is certainly a very unexceptionable young man. But what is the use of one beau among four girls? The two Clays were there, looking as forlorn as Shakspeare's nightingale: and Clara monopolized Henry Bell, as though he belonged to her."

"Certainly I did," said Clara; "and so would you, if he had given you the chance. Did you ever see such a dress as Betty Clay had on? She looked like a buckwheat cake in it."

"And Mrs. Stetson's hair, Clara? Did you notice it? Screwed up behind into an almost invisible little catogan, and put over her ears so tight that she looked as if she had been in the pillory and came out with her ears off."

"Was the dinner in good style?" again inquired Maggie.

"Yes, but too elaborate. Those people that have not always been upper tens think it necessary to crowd their tables, and ruin one's digestive organs. I declare, I thought I should swoon when that last course came in. I was actually crammed with dinner, and looked forward to dessert with a hope of relief!"

"And those two Charlotte Russes! As if one were not enough, with all that ice-cream and jelly! Mrs. Hildreth said, at least half a dozen times, how careful Soufflée was about having sweet cream, in spite of the scarcity and expense. The idea of hinting to guests the cost of their entertainment! These parvenu people are too absurd. I wish they would learn bienséance before they rise."

"So you had a dull day?" said Margaret, thinking of hers.

"Not precisely dull, but tedious. Laura does torment poor Phillips so, that it makes us uncomfortable; and when people have to 'smile and smile,' as we do, to gloss it over, it seems like that intense desire to gap in stupid company, and the struggle to look as though you merely meant to show now very wide awake you were. I do wish Laura would confine her rudeness to ourselves; but no one ever dared tell her so but Lewis, and he will never trouble himself to do it again."

"I wonder what he is doing now!" said Fanny. "I declare, I almost forgot his existence. And that horrid woman, too! She had better do something for herself, before she causes her husband to beg!"

"Depend upon it, Fanny, neither Lewis nor Cora would do that."

"Oh! you are their sworn champion, Margaret, we all know. But you cannot do them any good, child—be sure of it. I wish she would go home, or make Lewis mad, so that he could send her there."[287]

"Fanny!" cried Margaret, shocked, "how unfeeling!"

"Pshaw! Did she not rob us of Lewis? Papa is poorer than ever; and we go about dressed in shabby clothes, through her fault. Lewis used to pay all our little bills, and now——."

"And now," interrupted Margaret, "instead of remembering his generosity with gratitude, you abuse him for trying to be happy according to his own ideas. You almost get on your knees to Laura if she but gives you a cast-off ribbon. Be as full of deference to Lewis for past favors."

"We are obliged to curry favor with Laura," said Clara, lowering her voice. "She has us all pretty much under her control since she promised to live with us after her marriage."

"Excuse me," said Maggie, "but I am not by any means under Laura's dominion. She makes me no presents, and I make her no protestations. I am civil to Mr. Phillips, however—and that is more than you are, Clara."

"I am afraid," said she, laughing, "Laura is so entichée of her love that she does not like us to pay him attention. Cora won her eternal hatred by speaking gently to him."

"How she must abuse us now!" exclaimed Fanny, after a pause. "I expect Lewis is tired of our very names. She was always a vulgar thing, any how."

"Vulgar!" cried Margaret. "You go rather too far, my dear sister. Cora is as far from being vulgar as your own particular self—and you are not sincere when you say so. Moreover, I believe she mentions our family as seldom as possible. I wish that she could forget us, I am sure—for she was brutally treated."

"Do hush, Maggie; here is papa, and you have half persuaded him to think as you do. He seems actually conscience-stricken about Lewis's leaving home. I would not be surprised to find him visiting Cora after a while."

"Where do they live, I wonder?" asked Fanny. "Laura will never let papa know, if she can help it; and they might go to Kamschatka before we Would discover it."

"Come, girls, go to your rooms," said Mr. Clavering, entering. "You talk too much, and too lightly. Go to bed, and sleep if you can. It is more than I have been able to do since you sent my poor boy from his father's house."

The next morning at breakfast Laura seemed a little more amiable, and began discussing plans for the summer excursions. Spring had set in, and many were changing town homes for country ones.

"I vote for Dingleford," said Phillips, with a sudden burst of valor.

"You!" said his wife, with a look of scorn—"you!"

Mr. Phillips retired into himself, like Mr. Jenks of Pickwickian memory, that being the only retirement he was allowed; and Laura went on without further notice.

"We will to Brooksford. The girls can come; for I will pay Clara's expenses, and papa can easily do the rest. I heard the Martins, the Hildreths, and the Fentons say they were going."

"Thank you for my share," said Margaret. "I stay at home; your fashionable friends are my aversion."

"You are so foolish, Maggie! You will never marry in the world."

"Tant mieux, I have no ambition to become madame. My tastes are very simple, indeed. 'Liberty for me!' is my motto."

And it was arranged that Fanny and Clara should accompany Laura to Brooksford to meet their friends, leaving Margaret and her father at home to brave dust, heat, and musketoes as they could.

The old gentleman went to his counting-room to sit and think; Maggie applied herself to some household occupation; Laura retired to her chamber to fret like a peevish child; and Fanny and Clara prepared themselves to go down to the front parlor to receive morning calls.

The bell rang, and the visits began. The consequence of each was easily determined by the reception of the hostess, whose smiles were dispensed more freely to some than to others. Mrs. Markham seemed determined to outstay them all, and, being one of the "ultras," was encouraged to do so. The dinner was once more discussed, as she had been one of the invited, and Clara once more voted it a bore.

"I expected as much when I sent my refusal," said Mrs. Markham. "I hate dinners; they are always dull and stupid. How can it be otherwise when people meet expressly to eat?"

"And Mrs. Hildreth's piano is such an old kettle, too! I felt it almost an insult to be asked to play on it."

"Yes; with such a sweet voice as yours, Clara, you ought to have a perfect instrument. But where is Mrs. Clavering? She seems to have withdrawn herself entirely from the world; we never see her now."

"She is not here," said Clara, coldly. "She does not live with us."

"No! Where is she then?" inquired Mrs. Markham, with more interest than Clara liked. "She is a lovely creature. George fell quite in love with her."

The girls seemed embarrassed; but Fanny's amiable expression advanced to the rescue—

"The fact is, dear Mrs. Markham, we were somewhat disappointed in Lewis's wife. She is very beautiful and accomplished, and, I dare say, means well—in fact, I'm sure that her heart is very good, and all that; but she hurt poor Laura's feelings so dreadfully one day that we really had to notice it in spite of our love for Lewis. It almost breaks my heart to think of it; but Cora was so violent after Laura once advised her, in a mild, sisterly way, to be more economical (she was extravagant), that we felt it our duty to rise against it; and[288] she left the house in great displeasure, making poor Lewis believe, of course, what she liked. I don't think she meant it," continued Fanny; "but it seemed unkind. I do not think she intended to be"—

"Then why did you notice it?" asked Mrs. Markham, abruptly. "I would have found what palliation I could to prevent such a break up of ties."

This was something of a poser, and the two sisters exchanged glances; but Fanny once more exerted her soft tones in behalf of "poor Laura."

"You know we could not hesitate between our own sister and Mrs. Clavering. We could not have her insulted by a stranger, however ignorant she may be of intentional wrong."

"But your brother is—your brother, is he not?"

Here Laura entered, and the conversation was stopped, to the infinite relief of Fanny and Clara, who began to see that there was really nothing to boast of in their treatment of Cora. The truth was, Mrs. Markham had been on the opposite side of the street when they one morning brushed against their sister-in-law with their usual impertinence, and, amused at the scene, she tried to find out the cause of it. On her return home, after her endeavors, she related what she knew to her brother, and made her comments.

"Really, George, the idea of trying to persuade people that Cora Clavering is a monster is, beyond everything, absurd; as if everybody didn't see how unwelcome the poor thing was, how shabbily they served her, and how they tried to hide her when she came among them. Why, they never invited a soul to meet her as a bride; and when I asked for her the day I called, you would have thought I mentioned a troublesome animal."

"She is too pretty, Helen," said her brother. "That Mrs. Phillips is a perfect tartar, and her sisters have no heart for anything but show. They would sell their father for their love of fashion."

"All but Margaret, George."

"All but Margaret; and she is as far above them as heaven is above earth. She must have had some other 'bringing up' than theirs. I would swear that she never ill treated Mrs. Clavering."

"Not she! Maggie loves her devotedly."

"Then that is sufficient proof to me of her perfect innocence and their own falsehood. Mark that, Helen, Margaret's love proves that Mrs. Clavering is worthy of kind and gentle treatment."

One day Cora looked through the blind and saw her father-in-law before the gate. He looked wistfully in, and stood for a few moments with his hand on the latch. She would have gone out to meet him; but, remembering their parting, felt reluctant to expose herself to farther insult. But her heart yearned towards the poor old man, as she looked at his bent form and face of care. He was her husband's father, and as such excited her sympathy. On Lewis's return, she mentioned the circumstance to him.

"I wish he had seen you, dearest; he is sorry for the past, and doubtless wished to come in, but dared not. He and Maggie are alone at the house. I met her to-day, and she told me she was coming soon to see you."

Dear Maggie! She came soon, and announced her approaching marriage with Mrs. Markham's brother, George Seymour. She, whose motto was "Liberty for me!"

"But, you see, Cora, I could not resist George; and all this time I have loved him without being certain how it would terminate. I want to be married in church; so does he; and you and Lewis will come and sit near me. Laura and the girls are coming home for a week, and I want to persuade papa to return with them. He will be so lonely without me! We leave an hour or two after the ceremony."

"And when will you be back?" asked Cora, as the tears fell from her eyes. "How I shall miss you, darling!"

"We are going North to see George's mother, and, of course, will not be back before the fall. You will write constantly, Cora?"

"Of course I shall; it will be one of my pleasures to do so. May you be happy, dear Margaret—God knows you deserve it! Lewis and I will both be at church, dearest, with hearts full of love for you and your future husband."

Margaret blushed, and, kissing her, tripped away with a light heart.

A few days after, she was in church to have her destiny for ever changed. The long bridal veil concealed her sweet face, but her low, distinct tones reached the brother and sister, sending a prayer into the heart of each for that young thing's future.

It was over—Margaret's vows were spoken; her husband led her from the altar with a look of pride, and friends pressed forward to congratulate her. Tenderly met she the warm embrace of the two that loved her so well, and her last words to Cora were a low whisper—

"Take care of my father!"

The others passed their brother's wife unheeded, though they spoke to him a few words. They had ceased to care for him, and he was no more than an acquaintance.

The carriages whirled away, and the bride left her home to learn another's ways and habits. Laura returned to Brooksford with her sisters. They could not remain at home; nor would their father go with them. He tired of the world, and felt how little they cared for his comfort.

Soon he fell ill, and sent for Lewis. Cora was alone when the message came, and flew to see him. She was shocked at the change, and insisted upon removing him to her own home. Once in that dear little room, he seemed better, and, when Lewis came in, fell asleep clasping his hand. Kindly watched Cora by the old man, soothing him, reading to him, and attending to his every want. He seemed so grateful, and would follow her light form with his eyes until the tears flowed from them. But he[289] gained no strength; the doctor shook his head and thought this a bad symptom. He could not "minister to a mind diseased," and the cares of business had shattered that weak spirit. Lewis wrote to his sisters; but they thought he was only too easily alarmed, and wrote in return for further tidings. Their letter came when their father lay speechless in a state of paralysis.

Fanny arrived in haste. Mr. Clavering knew her; but his look turned from her to Cora, who held out her hand to her sister with an expression of earnest sympathy. Fanny saw it, and burst into tears. Lewis led her from the room, and an hysterical fit was the consequence. Her screams reached the old man's ear, for he looked troubled; but Cora signed to the servant to close the door, while she sat down beside him, trying to soothe him into sleep. He soon fell into a quiet slumber, and she then went to Fanny's assistance.

Her quiet but efficient help succeeded in calming her, and together the three watched all night by their father's bed. He looked so pleased as he opened his eyes and saw them together. Cora bent down and kissed him, as she read his look, and once more held out her hand to Fanny. He signed for her to come nearer. She kneeled at his side, and laid her young, sweet cheek to his, and once more he closed his eyes. Towards morning he grew weaker, and a few hours after he had gently breathed his last, Laura, her husband, and Clara arrived.

Their grief was loud and violent, and painful to witness. If any feeling of remorse visited their hearts, none knew it, for no reproach escaped their lips. Fanny alone seemed stricken, and turned to Cora for comfort.

Mr. Clavering was buried by the side of his wife. His children followed him to the grave; but in all that crowd not one mourned him as Cora did. She loved the poor old man that clung to her so like a child; and as she looked at Lewis and beheld his manly grief, she grieved anew over their short separation.

The most becoming mourning was chosen, and the most fashionable bombazine bonnets ordered. Laura and Clara hated black, and thought it a dreadful thing to wear such an uncomfortable dress in the summer. But custom was not to be braved, and they all appeared at church the Sunday after, looking very proper, having asked Cora into their pew. There was no longer an excuse for refusing to speak to her, and they had requested her to appear with them in public once more, thinking, perhaps, that the world would expect it—the world, with its countless eyes, ears, and tongues!

Poor Margaret! Sorrow came soon to disturb her newly-found bliss, and she returned earlier than she had intended, to weep over her father's grave. Her pale face bore witness to her suffering, and Seymour's tenderness alone called her from her indulgence of her grief. How she blessed Cora for her care of her father! How she loved her for her forgiving spirit!

She saw her now almost daily, for they lived so near; and Cora had this one cause for thankfulness as troubles gathered around her little fireside. Lewis had striven with superhuman strength to increase his slender capital, but in vain. Cora, whose stout heart never failed her, retrenched here and there, deprived herself almost of the necessaries of life to try and stay the storm. When her husband remained at the office instead of returning to tea, Cora's evening meal was a slice of dry bread with a cup of weak Bohea. For him she prepared some dish set by from dinner, which she had seen him relish.

Turning down the lamp that the oil might not waste, she would sit wondering how she could help her darling Lewis. She knew how much he would object to have her apply to her mother, and, hating to grieve that tender parent's heart, she wrote cheerfully and hopefully when her heart was weighed down by anxiety. Lewis was growing thin, his buoyant spirit was gone, and she wept over that, indeed. Maggie dreamed not of the cause, but she, too, remarked the change in both, and felt doubly uneasy about these two so dear to her. She questioned Cora closely; but Cora was a sealed book this time. Lewis was peculiarly sensitive upon the subject of his poverty, and could not bear the thoughts of the triumph it would occasion Laura when she knew that his wife was really in distress. Slowly, but alas too surely, the little sum diminished, and Cora would soon lose her dignity of banker. She opened the drawer and counted the remainder with a deep sigh, and began to feel how terrible it was to be poor. Not that she repined for herself—oh no!—but the idea of her husband's wan face was like a dagger in her heart. She looked around her; there was nothing within her modest dwelling that could be parted with, nothing but her mother's gift, and she knew that Lewis would not hear of that. In a few days, she would be forced to tell him that the drawer was empty, and not a cent left to provide for even their scanty wants. She buried her face in her hands.

She did not see the servant enter, and Nora stood some time at the door watching her with a look of sympathy, for she knew a portion of her mistress's sorrow, and felt it, too.

"Won't I put on some more coal, Mrs. Clavering?" at length she asked.

Cora looked up; the fire was quite out, and it was a cold night, but she had not heeded it.

"Never mind, Nora; my husband will soon be home now, and it would be useless. You know he never sits up long after he returns."

"But it is a cold, wet night, ma'am, and Mr. Lewis will want to dry his clothes," persisted Nora.

"Is it a wet night, Nora?"

"Lord bless you, Mrs. Clavering, it has been pouring down rain for an hour past!" and she ran back to the coal house, returning in a second with the scuttle. "You see, ma'am," continued Nora, as she lighted the fire and the cheerful light filled the room, "you thinks too much. I've been here[290] half a dozen times to-night, and seen you a ponderin' on sad things. It won't do, ma'am; thinking don't fatten folks."

Cora smiled, and Nora went on. She was privileged, for she had been a servant in old Mrs. Clavering's family, and at her instance came to live with Cora when her household cares began.

"You see, Miss Cora"—(Nora never said Mrs. Clavering more than once or twice)—"I know what ails you, and you ought not to take on about it so. The darkest hour 's before the dawn, and your dawn an't come yet."

"I wish it were, Nora," said Cora, smiling again. "But there is a hope, at all events, for worse than I am. You say that you know why I am sad, Nora, and I am sure that you feel for one whom you have served so long. Now, is there nothing I can do to help Mr. Clavering that you know of? Nothing that will enable me to keep you? for, as things are now, there is no use in concealing that I could no longer afford to employ a servant, were there no brighter prospect."

"Takes two to make a bargain, Miss Cora, and you couldn't send me off if I didn't choose to go," said Nora, stoutly. "It's a hard thing to see you work, but I s'pose it's got to be. Would you sew, ma'am? I'm sure I could get plenty of that."

"Certainly I would, gladly I would," said Cora, eagerly. "So keep your word, Nora, and bring me something to do as soon as you can. You know how nicely I can do fine work."

But Nora was crying, and went out of the room. Her pride for "the Claverings" was sadly humbled, and her "poor Miss Cora too unhappy!" She kept her promise, however; and long after the portfeuille lay useless in the drawer, Cora's busy fingers earned wherewith to supply the every-day wants of the house. What mattered it if her bonnet grew rusty and her gloves were mended? She was always pretty and neat, and had always that sweet fresh color that a consciousness of right sent to her cheek. The same glad smile ever welcomed her husband, the same rich, clear voice sang the touching songs he loved, and he seemed to catch a portion of her undying spirit.

He returned home one evening earlier than usual, and going up to Cora, threw something into her lap.

"That is for the bank, my singing-bird: it is a long time since I made a deposit, is it not? Oh, Cora!" and Lewis's deep voice faltered as he said it—"oh, Cora, if you knew how I dreaded to have you tell me that it was all gone, when I had no more to give! What hours of misery I have endured, my darling, since I came so near actual want! And you, my noble-hearted wife, how bravely you gazed at the coming clouds—how firmly you awaited the storm!"

"And has the storm ceased, Lewis?—is the sunshine returning?"

"There is a glimpse of it shining through the crevice, Cora, and I dare hope for better times, even with no prospects. I feared this, dearest, when my poor father sent me on the wide world with the slender sum I placed in your hands. It must be all gone now; is not your drawer empty? for, with your strict economy, it has lasted beyond my expectations."

Cora smiled, and brought a little chair to sit beside him. Fondly he stroked her shining hair as she leaned her head against him, and all sense of sorrow left his breast as this, his treasure, was so near. Holding one little hand, he watched the arch smile upon those beautiful lips.

"Tell me, rose-bud, how is your bank now? Have you not also dreaded to mention its emptiness to your gloomy husband?"

"I have, indeed, Lewis; but there is something yet in the drawer, and I shall not touch your present supply for a while, as I do not need it."

"You do not need it, Cora! Surely, dearest, you must have used all that I gave you at first; it was not even sufficient for our wants till now; for I have often wondered at your ingenuity in providing as you have. You have not parted with anything you valued, Cora?"

She shook her head—

"Not at all. Do you miss any of my pet china, my silver, or my cherished books?" asked she, laughingly.

"Then how is it, Cora, that you have managed so well?"

"Oh, I was blessed by the fairies at my birth, and am a successful mesmerizer, too. I have the power of making you see more than is before you."

"Let me see your account book, then, queen of spirits. I had no idea that I had married a banshee. Where is your book?"

"I keep my own accounts, Mr. Lewis, so please you. This is a liberty I will not allow." And Cora ran to her drawer and turned the key, thus preventing the discovery of her labor of love.

But she confined herself too closely, and it was not long before her face began to grow pale and her temples throb through the night. Lewis was alarmed, and sent a physician. He prescribed exercise, country air, and quiet; three luxuries of which poor Cora had been deprived for months, and Lewis was more wretched than ever.

In the morning early, before Cora had risen, Nora went to him and told all. Her young lady should not work herself to death; hiding it from Mr. Lewis was a sin, and so she made bold to betray her. Lewis bowed his head and wept; she had, indeed, been firm in adversity; she had, indeed, been true to her word, and kept a stout heart. How he loved her! how willingly he could have knelt before her! The scene that passed between them I could not think of describing; it must be imagined by the kind-hearted reader, by the sacrificing wife, and the grateful, devoted husband. One load was taken from the mind of Lewis, the absence of local disease in his cherished one, and he thankfully turned his thoughts to the Great Source of all his joys, blessing him for the trials he sent that he might be purified.[291] Poor as he was, destitute of expectation as he felt himself to be, he left home with a light heart. His gem, his bright, beautiful Cora was not threatened with a loss of health. She had promised to rest, and now she would find her roses once more.

During all this time, Margaret had watched her brother and sister with intense anxiety, and, suspecting the cause of their altered looks, set her little head to work to find out more. On a visit to Laura, she mentioned Lewis and his appearance of delicate health. Cora's name she never breathed before her hard-hearted persecutor.

"Oh, they are so poor; no wonder!" cried she, with a look of scorn. "I suppose they are starving. I wonder they are not begging."

"God forbid!" said Margaret, earnestly. "Have you heard anything?"

"Yes; Phillips told me Lewis did not make a cent, and wondered how they had lived till now. The other evening, Mr. Layton was here and asked me about Lewis, saying he could not find his house. He wished to offer him the situation of head clerk in the establishment of Layton, Finlay & Co."

"And what did you tell him?" asked Margaret, breathlessly.

"Oh, I told him there was no use in doing anything of the kind, as he would not be able to keep Lewis long, his habits of negligence were so irremediable."

"Great God of heaven!" cried Margaret, starting up and standing before her sister. "You did not tell him that, Laura!"

"Indeed, I did! I have no idea of seeing that wife of his benefited in any way. She married him poor; let her remain so."

Margaret was gone in an instant. She almost flew down the street to her husband's office, and, fortunately, met him on her way. In a few words, she related to him what had passed.

His indignation was not less than hers; and, before a quarter of an hour elapsed, George Seymour was closeted with Mr. Layton, his cheek flushed and his eye bright with excitement, as, without one word of circumlocution, he told the plain, unvarnished truth.

Mr. Layton was much shocked, and hastened to make his offer to Lewis Clavering in "plain black and white." Before night, the note was received, and Lewis and his inimitable Cora had the prospect of comfort and happiness with the surely-coming salary of two thousand a year. Their grateful reception of this intervention in their behalf, their unmurmuring hearts at past suffering, would form a bright example to hundreds possessing perfect independence and no cares.

Laura's disappointment knew no bounds. Margaret's joy was complete. How she and Cora talked over this good fortune, and how silvery and sweet their merry laughter seemed to Lewis and Seymour, who were listening to every word these two said. They were now discussing a marriage on the tapis.

Clara was fortunate enough to secure an offer from a widower with a son older than his future stepmother. But Mr. Penrose was very rich, and could be hid, like Tarpeia of old, under jewels and gold. Clara loathed, and would often turn from him with disgust, as her eye fell upon his great clumsy form "fitting tight" (as the mantua-makers say) to the Louis Quatorze, in which he regularly ensconced himself. His false teeth were unexceptionable; his cheeks round and shiny. He bore one resemblance to poor Uncle Ned:

Margaret ventured a hint upon the disparity of age and disposition, a sad inequality to bring into married life. But Laura talked so loudly in favor of wealth and Mr. Penrose's consequence, that she was forced to be silent. Fanny, too, approved Clara's wisdom and prudence. It was an excellent match; Clara had shown herself a woman of determination, superior to the foolish girls who prated of love and cottages. Let a man be esteemed before he was loved, and there would be no doubt of perfect harmony afterwards.

"So write your cards for the reception-day, Clara, and we will have a grand ball in the evening. You shall be married with éclat becoming your prospects."

"A ball, Laura!" cried Maggie. "Have you forgotten our mourning?"

"No, indeed; I wish I had. But, as we have worn it now nearly a year, I'm going to take the opportunity of leaving it off on Clara's wedding day. So will she and Fan."

"But, Clara," said Maggie, turning to her, "our father has not been dead a year yet! Leave off mourning if you will; but, for mercy's sake, do not outrage decency by going to a ball, even if you have no feeling on the subject."

"I agree with Laura, Margaret. We have been in prison long enough. I do not wish to begin my married life in seclusion. We have had soirées only six or seven times since papa died, and I went to one polka party at Mrs. Hildreth's. I'm sure I have been dull enough to suit any one."

"You do not pay our father the respect that Cora does, and she is only our sister-in-law."

"Don't bring up her name," said Laura; "I hate to hear it. Clara may send her a piece of cake if she likes, but she shall not be asked here; though I'm willing that Lewis should be invited, to show what I think of her."

"They would not come, depend upon it," said Margaret; "nor shall I; so do not expect me. You will be much blamed."[292]

"Pshaw!" said Clara. And so she was married, having issued cards to all her fashionable friends. Her reception-day was very brilliant, the fête the gayest of the season; and the bride and groom left the next afternoon for their wedding tour, amid the applause of the waiters, who regaled themselves on the scraps of the feast and the half bottles of champagne that were left to evaporate.

A year after, no one would have recognized the gay and elegant-looking Clara Clavering in the faded Mrs. Penrose. Her elephantine spouse was not so amiable as before marriage; and the poor wife was heard to say that, after all, wealth was not the principal thing in marriage; she would prefer a competency and happiness.

Laura's health was much impaired by her unceasing fretfulness and ill humor, and eventually her sight became affected. Sitting in a dark room, unable to read or sew, deprived of every amusement, she wept herself blind at last! Reduced to this melancholy state, Cora Clavering once more stepped across the threshold from which she had been so rudely thrust, and offered her aid to the sufferer. Her gentle hand applied the cooling compressions to Laura's swollen lids; her noiseless footstep could cross the room and not disturb her if she slept. That low sweet voice never grated harshly on the sensitive ear of the invalid, and she learned to long for her coming as a captive for freedom. Fanny clung to her as a guardian angel; for from how many heartaches did Cora's presence save her! Margaret watched with her, and together they persuaded Laura to submit to an operation; and she requested that it might not be delayed.

But on Cora she leaned for support in the hour of trial, and, clasping her hand firmly, said that she was prepared. Faithful and true, that voice encouraged her through the trying moments. That slender arm supported her head, and seemed so strong; and until the bandages were removed from her eyes, still that slight form glided about to supply her bitter enemy's every want.

But at length Laura could see once more, and light had come, too, upon her darkened soul. Sitting one evening in Cora's little parlor, she glanced around with a look of admiration upon its plain furniture, its absence of luxury, and remembered the perfect content of its happy mistress. While she, surrounded by all that wealth could afford, had made herself and everything around her wretched. Fanny had often dreamed of flying to Cora for shelter from bitter words and reproaches, and Clara had long since ceased to visit the sister from whose lessons she had learned to be that misguided thing, a worldly woman.

"You may well love Cora, Lewis," said Laura, as she saw how fondly he watched her every motion; "she seems to have the secret of exorcising evil spirits, and replacing them with good ones, besides being the best nurse, the best wife, and the most sunshiny soul that ever was on earth."

"Don't flatter me, Laura," said Cora, laughing, and giving Margaret's baby a toss that made the little creature clap its hands with delight. "Lewis told me once he thought he had married a banshee."

"He married what is as rare as a banshee," said Margaret, who had been sitting at Laura's side, knitting a tidy for the arm-chair her skillful fingers had embroidered to embellish Cora's little Eden. "He has the brightest jewel in the world, in a wife that can forgive, forget, and return, without even seeming to be aware of it, 'good for evil.'"

The following letter (never before published) from Mrs. Mercy Warren to Mrs. Lincoln will be found interesting. Mrs. Lincoln was the eldest sister of Josiah Quincy, Jr., to whom allusion is made in the letter. Her husband, a brother of General Lincoln, died before the Revolution, and she resided, during the war, with her father, Josiah Quincy, at Braintree, now Quincy, in the mansion, now the summer residence, of President Quincy. One of her letters to her brother, Samuel Quincy, who left Boston with other loyalists, published in "Curwen's Memoirs" (page 562), is full of eloquence. She afterwards married Ebenezer Storer, of Boston, and died, at the age of ninety, in 1826, a few weeks after the decease of her early friend, John Adams. She was for many years a correspondent of Mrs. Adams, and a life-long friendship subsisted between them. They were often together at the family mansion at Quincy, where, in 1824, she welcomed Lafayette to her father's residence. The present Mrs. Quincy's mother, Mrs. Maria S. Morton, was there on that occasion. This lady had resided at Baskenridge, New Jersey, during a seven years exile from New York, where her husband, an eminent merchant, left part of his property, devoting the profits of the sale of the rest to the cause of American independence. He died during the war, leaving Mrs. Morton with six children. Washington and all his officers were frequent guests at her house, and some of the stirring incidents of the campaign in New Jersey occurred in her immediate neighborhood. She was born at Raub, on the banks of the Rhine, and lived to the age of ninety-three, passing the last twelve years with her daughter. She retained her powers to the last, and often beguiled the attention of President Quincy's children with the narrative of the times when, as he used to say, "the women were all heroines." She died at his residence at Cambridge.

Dear Mrs. Lincoln: If the tenderest sympathy would be any alleviation to your sorrow, when mourning the death of a beloved brother, the ready hand of friendship should soon wipe the starting tear from your eye. Yet, while I wish to console the disappointed father, the weeping sister, and the still more afflicted wife, I cannot restrain the rising sigh within my swollen bosom, nor forbear to mix my tears with theirs, when I consider that, in your valuable brother, America has lost a warm, unshaken friend.[B] Deprived of his assistance when, to all human appearance, had his life been spared, he might have rendered his country very eminent service.

By these dark dispensations of Providence, one is almost led to inquire why the useful, the generous, the spirited patriot is cut off in the morning of his days, while the base betrayer of his country, the incendiary, who blows up the flames of civil discord to gratify his own mad ambition, and sports with the miseries of millions, is suffered to grow gray in iniquity.

But who shall say to the Great Arbiter of life and death, to the righteous Sovereign of the Universe, why hast thou done thus?

Not surely man, whose ideas are so circumscribed, and whose understanding can grasp so little of the Divine government, that we are lost at the threshold, and stand astonished at the displays of Almighty power and wisdom. But shall we not rely on Infinite goodness, however severe may be our chastisement, while in this militant state, not doubting that, when the ball of Time is wound up, and the final adjustment of the wise economy of the universe takes place, virtue, whether public or private, will be crowned with the plaudits of the best of beings; while the vicious man, immured in his cot, or the public plunderer of nations, who riots on the spoils of the oppressed and tramples on the rights of man, will reap the reward of his guilty deeds?

The painful anxiety expressed in your last letter for the complicated distresses of the inhabitants of Boston, is experienced, in a greater or less degree, by every heart which knows anything of the feelings of humanity. But He who is higher than the highest, and "seeth when there is oppression in the city," I trust will deliver us. He has already made a way for the escape of many, and if speedy vengeance does not soon overtake the wretched authors of their calamities, we must consider them as the scourge of God, designed for the correction of a favored people, who have been too unmindful of his goodness; and when they shall be aroused by affliction to a sense of virtue, which stimulated their worthy progenitors to brave the dangers of the sea, and the still greater horrors of traversing a barbarian coast, in quest of Freedom denied them on their native shore, the modern cankerworms will, with the locusts and other devourers which infested[294] the nations of old, be swept, with the besom of destruction, from the face of the American World.

I hope my friend will not again be obliged to leave her habitation for fear of the ravages of an unnatural foe; yet I think we must expect continual alarms through the summer, and happy will it be for the British Empire, of which America is a part, if this contest terminate then. But, whether it be a season of war or the sunshine of peace, whether in prosperity or affliction, be assured Mrs. Lincoln has ever the best wishes of her real friend,

One of the early adventurers in the Valley of Ohio River was Isaac Williams. After he became a resident of the West, he explored its recesses, traveling along the shores of the Mississippi to the turbid waters of the Missouri. In 1775, he married a youthful widow, Rebecca Martin, the daughter of Joseph Tomlinson, of Grave Creek. Her first husband had been a trader with the Indians, and was killed in 1770. She was born in 1754, on the banks of the Potomac, in Maryland, and removed to Grave Creek with her father's family in the first year of her widowhood. Since that time she had lived with her unmarried brothers, keeping house for them, and would remain alone in their dwelling while they were absent on hunting excursions. She was young and sprightly in disposition, and had little knowledge of fear. In the spring of 1774, she paid a visit to her sister, who had married a Mr. Baker, and resided upon the banks of the Ohio, opposite Yellow Creek. It was soon after the celebrated massacre of Logan's relatives at Baker's station. Rebecca made her visit, and prepared to return home as she had come, in a canoe alone, the distance being fifty miles. She left her sister's residence in the afternoon, and paddled her canoe till dark. Then, knowing that the moon would rise at a certain hour, she neared the land, leaped on shore, and fastened her craft to some willows that drooped their boughs over the water. She sought shelter in a clump of bushes, where she lay till the moon cleared the tree tops and sent a broad stream of light over the bosom of the river. Then, unfastening her boat, she stepped a few paces into the water to get into it. But, as she reached the canoe, she trod on something cold and soft, and stooping down discovered, to her horror, that it was a human body. The pale moonlight streamed on the face of a dead Indian, not long killed, it was evident, for the body had not become stiff. The young woman recoiled at first, but uttered no scream, for the instinct of self-preservation taught her that it might be dangerous. She went round the corpse, which must have been there when she landed, stepped into her bark, and reached the mouth of Grave Creek, without further adventure, early the next morning.

In the ensuing summer, one morning while kindling the fire, blowing the coals on her knees, she heard steps in the apartment, and, turning round, saw a very tall Indian standing close to her. He shook his tomahawk at her threateningly, at the same time motioning her to keep silence. He then looked around the cabin in search of plunder. Seeing her brother's rifle hanging on hooks over the fireplace, he seized it and went out. Rebecca showed no fear while he was present; but, immediately on his departure, left the cabin and hid herself in the standing corn till her brother came home.

Her second marriage was performed with a simplicity characteristic of the times. A traveling preacher, who chanced to come into the settlement, performed the ceremony at short notice, the bridegroom presenting himself in his hunting-dress, and the bride in short-gown and petticoat of homespun, the common wear of the country.

This Rebecca Williams afterwards became famous among the borderers of Ohio River for her medical skill, and the cure of dangerous wounds. She was with Elizabeth Zane at the siege of Fort Henry, at Wheeling, and there exercised the healing art for the benefit of the wounded soldiers. In 1777, the depredations and massacres of the Indians became so frequent that the settlement at Grave Creek was broken up. It was in a dangerous locality, being on the frontier, and lower down the river than any other.

In December, 1777, when the British army was in possession of Philadelphia, and the Americans in winter quarters at Valley Forge, Major Tallmadge was stationed for some time between the two armies, with a detachment of cavalry, for the purpose of observation, and to circumscribe the range of the British foraging parties. The horses of his squad were seldom unsaddled, nor did they often remain all night in the same position, for fear of a visit from the enemy.

At one time the major was informed that a country girl had gone into Philadelphia with eggs, to obtain information. It is supposed she had been employed for that purpose by Washington himself. Desirous of seeing her, Tallmadge advanced towards the British lines, and dismounted at a small tavern called "The Rising Sun," within view of their outposts. In a short time, the young woman came from the city and entered the tavern. She communicated the intelligence she had gained to the major; but their conversation was interrupted by the alarm that the British light horse were approaching. Stepping to the door, Tallmadge saw them riding at full speed chasing in his patroles. No time was to be lost, and he threw himself on his horse. The girl besought him to protect her: he told her to mount behind him, which she did, and they rode three miles at full speed to Germantown. There was much firing of pistols during the ride, and now and then wheeling and charging; but the heroic damsel remained unmoved, nor uttered one[295] expression of fear after she was on horseback. Tallmadge mentions her conduct with admiration in his journal.

On the approach of winter, when the British army retired from the active service of the field, they were usually distributed, while in possession of Long Island, in the dwellings of the inhabitants within the lines. An officer, at first, visited each house, and, in proportion to its size, chalked on the door the number of soldiers it must receive. The first notice the good hostess commonly had of this intrusion was the speech, "Madam, I am come to take a billet on your house." The best mansion was always reserved for the quarters of the officers. In this way were women forced into the society of British officers, and, in order to conciliate their good will and protection, would often invite them to tea, and show them other civilities.

The "New London Gazette," dated November 20, 1776, states that several of the most respectable ladies in East Haddam, about thirty in number, had met at the house of J. Chapman, and, in four or five hours, husked about two hundred and forty bushels of corn. "A noble example," says the journal, "and necessary in this bleeding country, while their fathers and brothers are fighting the battles of the nation."

Lossing records a similar agreement on the part of the Boston women.

The "New York Spectator," April 13th, 1803, forty-seven years old, announces the arrival in New York of Mrs. Deborah Gannett, the "Deborah Samson" whose memoir appeared in a former number of the "Lady's Book." It says: "This extraordinary woman served three years in the army of the United States, and was at the storming of Yorktown under General Hamilton, serving bravely, and as a good soldier. Her sex was unknown and unsuspected, until, falling sick, she was sent to the hospital, and a disclosure became necessary. We understand this lady intends publishing her memoirs, and one or more orations which she has delivered in public upon patriotic subjects. She, last year, delivered an oration in the Theatre at Boston, which excited great curiosity and did her much credit."

This curious confirmation of the account given of her in the memoir alluded to should be a sufficient answer to the ill-natured criticism of the "London Athenæum," which, reviewing "The Women of the American Revolution," endeavors to throw discredit on the whole story, by ridiculing it as utterly improbable and romantic, though the critic does not bring proof to controvert a single statement, nor assign any ground for his doubt but "we surmise."

One of my earliest village reminiscences is a vision of old Captain Garrow, in his old-fashioned, square-skirted coat, plush shorts, silk stockings, shoe buckles, and, to crown the whole, his venerable tie-wig. He was a character, the captain. He was a relic of a past age, an antique in perfect preservation, a study for a novelist or historian. Born in Massachusetts before the rebel times, he had taken an active part in the Revolution; served as commissary, for which his education as a trader had qualified him; and the rank of captain which was attached to the office had given him the title he bore in his old age. When the war was over, his savings (very moderate, indeed, they were, for the captain was as honest as daylight) were invested in a stock of what used to be called English goods, but what are now, through the increase of manufactures in our own country, denominated dry goods; I think it rather fortunate for our village that the worthy captain pitched upon it for his residence, and for the sale of his well-selected English goods. His strict old-fashioned notions of commercial honor and punctuality gave a tone to the whole trade of the place, which lasted for a long time. His modest shop was a pattern of neatness and economy. His punctual attendance at all hours, his old bachelor gallantry to the lady customers, and his perfect urbanity to all, furnished an example to younger traders; while his stiff adherence to the "one price" system, while it saved the labor and vexation of chaffering, gave a stability to his establishment which made it respectable in the view of all sensible people.

Worthy Captain Garrow! well do I remember you at the meridian of your glory, the head "merchant" of our village, the acknowledged arbiter elegantiarum in all matters of chintz and linen, and lace and ribbons, and all the et ceteras of ladies' goods. Your opinion was law; for you were known to be the soul of honor, and your word in all engagements was reckoned as good as another man's bond.

But, in an evil hour, an invasion of Goths and Vandals came down upon us in the shape of cheap English goods' merchants. They inundated the place with gaudy, worthless trash at half price, gave unlimited credit, sold at almost any price you would offer, and seemed only anxious to have all the villagers' names in their books, and to double the consumption of English goods. The consequence was that the thoughtless part of the population deserted[297] the worthy captain's shop, which henceforward received the custom only of the old steady-going people. His ancient-looking wooden tenement, with its weather-beaten sign, was put out of all countenance by the new brick stores, and flaring gilt signs, and plate glass windows of his rivals. The captain, however, foreseeing the result, bore it all with a dignity and quiet worthy of his character. He "guessed" that the importers in Boston and New York were destined to suffer at a future day; and so it turned out; for, after charging many thousand dollars in their books to people who were not very punctual about payment, his rivals, one by one, all failed; their stocks were sold out by the sheriff, and their book debts were handed over to the lawyers by assignees.

After the lapse of a few months, a new swarm of cheap merchants succeeded them, with precisely the same result. Meantime, the captain kept the noiseless tenor of his way, and maintained the original character of his own modest establishment. He had grown rich, but exhibited none of the airs of a presumptuous millionaire. He was too dignified to be insolent.

Well do I remember, on a certain day, when the captain, now quite an old man, was near the close of his career, calling at his shop with my cousin Caroline, commissioned by her mother to purchase with ready money a piece of Irish linen. When she had examined the captain's stock, and was about to make a purchase, she happened casually to remark that Irish linen was sold sometimes at a lower price.

"O yes, my dear," answered the captain—he always called a lady, old or young, "my dear"—"O yes; you can buy Irish linen over the way, where the big sign is, for less money. They will sell it to you, I dare say, at half price, and cheat you at that. But their goods are not like mine. They will generally take less than they ask you at first; but I never have but one price. I was bred a merchant before chaffering came into fashion. You can go and trade with them if you like, however."

Poor Caroline, who had not been aware of the captain's weak point, hastened to apologize, concluded her purchase, and was careful in future to respect the captain's sensitiveness on the subject of cheap goods.

Ere I left my native village to become a wanderer over the wide world, the captain had been gathered to his fathers. Having no relatives, he directed the executors of his will to apply his handsome fortune to the establishment of an asylum for orphans, which still remains a monument of his sterling goodness and public spirit.

Scene I.—Rose Hill. The garden before Prof. Olney's house. Young Henry Bolton and Isabelle; she is weeping. Time morning.

After a partial recovery from the fatigues of the journey to the homestead, Mr. Richard Clifton appeared to be much improved in health, and strong hopes were entertained that his recovery would be complete. He manifested the proper showings of regret for the loss of his companion, though he had felt towards her none of that ardor of affection, and had enjoyed with her none of those felicities which had mingled in his visions of domestic life before he had become a prosperous man of the world. It was sad to have death enter his dwelling; it was sad to be left with no one whom he could call his own. Some of that loneliness which had long preyed upon him was, perhaps, unconsciously set to the loss of her who had filled but a small place in his heart, though she had been the wife of his bosom for a score of years, and had found in him all she expected in a husband; perhaps it would be scarce too much to say—all she desired.

In a few days, he was able to leave his chamber and sit with the family, though his feeble step and sunken eye contrasted strangely with the proud bearing which he exhibited but a few weeks before.

Susan devoted herself to his care, and his attachment for her seemed to increase daily. While her father was busy with the labors of the farm, and her mother was occupied with household cares, she talked with him, read to him, sung to him, and in every way strove to make the time pass pleasantly, and to woo back to his veins the tide of health.