The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Social Gangster, by Arthur B. Reeve This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Social Gangster Author: Arthur B. Reeve Illustrator: Will Foster Release Date: August 19, 2010 [EBook #33466] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SOCIAL GANGSTER *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CHAPTER I. The Social Gangster

CHAPTER II. The Cabaret Rouge

CHAPTER III. The Fox Hunt

CHAPTER IV. The Tango Thief

CHAPTER V. The "Thé Dansant"

CHAPTER VI. The Serum Diagnosis

CHAPTER VII. The Diamond Queen

CHAPTER VIII. The Anesthetic Vaporizer

CHAPTER IX. The Twilight Sleep

CHAPTER X. The Sixth Sense

CHAPTER XI. The Infernal Machines

CHAPTER XII. The Submarine Bell

CHAPTER XIII. The Super-Toxin

CHAPTER XIV. The Secret Agents

CHAPTER XV. The Germ of Anthrax

CHAPTER XVI. The Sleepmaker

CHAPTER XVII. The Inter-Urban Handicap

CHAPTER XVIII. The Toxin of Fatigue

CHAPTER XIX. The X-Ray Detective

CHAPTER XX. The Mechanical Connoisseur

CHAPTER XXI. The Radiograph Witness

CHAPTER XXII. The Absolute Zero

CHAPTER XXIII. The Vacuum Bottle

CHAPTER XXIV. The Solar Plexus

CHAPTER XXV. The Demon Engine

CHAPTER XXVI. The Electrolysis Clew

CHAPTER XXVII. The Perpetual Motion Machine

CHAPTER XXVIII. The Cancer House

CHAPTER XXIX. The Quack Doctors

CHAPTER XXX. The Filterable Virus

CHAPTER XXXI. The Voodoo Mystery

CHAPTER XXXII. The Fluoriscine Test

CHAPTER XXXIII. The Respiration Calorimeter

CHAPTER XXXIV. The Evil Eye

CHAPTER XXXV. The Buried Treasure

CHAPTER XXXVI. The Weed of Madness

"I'm so worried over Gloria, Professor Kennedy, that I hardly know what I'm doing."

Mrs. Bradford Brackett was one of those stunning women of baffling age of whom there seem to be so many nowadays. One would scarcely have believed that she could be old enough to have a daughter who would worry her very much.

Her voice trembled and almost broke as she proceeded with her story, and, looking closer, I saw that, at least now, her face showed marks of anxiety that told on her more than would have been the case some years before.

At the mention of the name of Gloria Brackett, I saw that Craig was extremely interested, though he did not betray it to Mrs. Brackett. Already, with my nose for news I had scented a much bigger story than any that had been printed. For the Bracketts had lately been more or less in the news of the day.

Choking back a little suppressed sob in her throat, Mrs. Brackett took from a delicate gold mesh bag and laid on the desk before Kennedy a small clipping from the "Lost and Found" advertisements in the Star. It read:

"REWARD of $10,000 and absolutely no questions asked for the return of a diamond necklace of seventy-one stones which disappeared from a house at Willys Hills, Long Island, last Saturday or Sunday.

"La Rue & Co., Jewelers,

"—— Fifth Avenue."

I recognized the advertisement as one that had occasioned a great deal of comment on the Star, due to its peculiar nature. It had been a great mystery, perhaps much more so than if the advertisement had been worded and signed in the usual way.

I knew also that the advertisement had created a great furore of excitement and gossip at the fashionable North Shore Hunt Club of which Bradford Brackett was Master of Fox Hounds.

"At first," explained Mrs. Brackett nervously, "La Rue & Co. were able to keep the secret. They even refused to let the police take up the case. But as public interest in the advertisement increased at last the secret leaked out—at least that part of it which connected our name with the loss. That, however, seemed only to whet curiosity. It left everybody wondering what was back of it all. That's what we've been trying to avoid—that sort of publicity."

She paused a moment, but Kennedy said nothing, evidently thinking that the best safety valve for her overwrought feelings would be to let her tell her story in her own way.

"Why, you know," she resumed rapidly, to hide her agitation, "the most ridiculous things have been said. Some people have even said that we lost nothing at all, that it was all a clever attempt at notoriety, to get our names in the papers. Some have said it was a plan to collect the burglary insurance. But we are wealthy. They didn't stop to think how inconceivable that was. We have nothing to lose, even if the necklace is never heard of again."

For the moment her indignation had got the better of her worry. Most opinions, I recalled, had been finally that the disappearance was mixed up with some family affairs. At any rate, here was to be the real story at last. I dissembled my interest. Mrs. Brackett's indignation was quickly succeeded by the more poignant feelings that had brought her to Kennedy.

"You see," she continued, now almost sobbing, "it is really all, I fear, my own fault. I didn't realize that Gloria was growing so fast and so far out of my life. I've let her be brought up by governesses and servants. I've sent her to the best schools I could find. I thought it was all right. But now, too late, I realize that it is all wrong. I haven't kept close enough to her."

She was rattling on in this disjointed manner, getting more and more excited, but still Kennedy made no effort to lead the conversation.

"I didn't think Gloria was more than a child. But—why, Mr. Kennedy, she's been going, I find, to these afternoon dances in the city and out at a place not far from Willys Hills."

"What sort of places?" prompted Kennedy.

"The Cabaret Rouge," answered Mrs. Brackett, flashing at us a look of defiance that really masked fear of public opinion.

I knew of the place. It had an extremely unsavory reputation. In fact there were two places of the same name, one in the city and the other out on Long Island.

Mrs. Brackett must have seen Kennedy and me exchange a look askance at the name.

"Oh, it's not a question of morals, alone," she hastened. "After all, sometimes common sense and foolishness are fair equivalents for right and wrong."

Kennedy looked up quickly, genuinely surprised at this bit of worldly wisdom.

"When women do stupid, dangerous things, trouble follows," she persisted, adding, "if not at once, a bit later. This is a case of it."

One could not help feeling sorry for the woman and what she had to face.

"I had hoped, oh, so dearly," she went on a moment later, "that Gloria would marry a young man who, I know, is devoted to her, an Italian of fine family, Signor Franconi—you must have heard of him—the inventor of a new system of wireless transmission of pictures. But with such a scandal—how can we expect it? Do you know him?"

"Not personally, though I have heard of him," returned Kennedy briefly.

Both Craig and myself had been interested in reports of his invention, which he called the "Franconi Telephote," by which he claimed to be able to telegraph either over wires or by wireless light and dark points so rapidly and in such a manner as to deceive the eye and produce at the receiving end what amounted to a continuous reproduction of a picture at the transmitting end. At least, in spite of his society leanings, Franconi was no mere dilettante inventor.

"But—the necklace," suggested Craig, after a moment, for the first time interrupting the rather rambling trend of Mrs. Brackett's story, "what has this all to do with the necklace?"

She looked at him almost despairingly. "I don't really care for a thousand such necklaces," she cried. "It is my daughter—her good name—her—her safety!"

Suddenly she had become almost hysterical as she thought of the real purpose of her visit, which she had not yet been able to bring herself to disclose even to Kennedy. Finally, with an effort, she managed to control herself and go on.

"You see," she said in a low tone, almost as if she were confessing some fault of her own, "Gloria has been frequenting these—recherché places, without my knowledge, and there she has become intimate with some of the fastest of the fast set.

"You ask about the necklace. I don't know, I must admit. Has some one of her friends taken advantage of her to learn our habits and get into the house and get it? Or, have they put her up to getting it?"

The last query was wrung from her as if by main force. She could not even breathe it without a shudder. "When the necklace was stolen," she added tremulously, "it must have been an inside job, as you detectives call it. Mr. Brackett and I were away at the time at a week-end party. We supposed Gloria was visiting some friends in the city. But since then we have learned that she motored out with some of her dance-crazed acquaintances to the Cabaret Rouge, not far from Willys Hills. It must have been taken then—by some of them."

The recital to comparative strangers, even though they were to be trusted to right the wrong, was more than she could bear. Mrs. Brackett was now genuinely in tears, her shoulders trembling under the emotion, as she bowed her head. Her despair and self-accusation would really have moved anyone, much less were needed to enlist Kennedy. He said nothing, but his look of encouragement seemed to nerve her up again to go on. She forced back her feelings heroically.

"We put the advertisement that way because—well, now you understand why," she resumed; then anticipating our question, added, "But there has been no response."

I knew from her tone that even to herself she would not admit that Gloria might have been guilty. Yet subconsciously it must have been in her mind and she knew it was in ours. Her voice broke again.

"Mr. Brackett has repeatedly ordered Gloria to give up her fast acquaintances. But she defies him. Even to my pleadings she has turned a deaf ear."

It was most pathetic to watch the workings of the mother's face as she was forced to say this of her daughter. All thought of the necklace was lost, now.

"I—I want my daughter back," she almost wailed.

"Who are these rapid youngsters?" asked Craig gently.

"I don't know all of them," she replied. "There is young Rittenhouse Smith; he is one. The Rittenhouse Smiths, you know, are a very fine family. But young 'Ritter,' as the younger set call him, is wild. They've had to cut his allowance two or three times, I believe. Another of them is Rhinelander Brown. I don't think the Browns have much money, but it is a good family. Oh," she added with a faint attempt at a smile, "I'm not the only mother who has heart-aches. But the worst of it is that there are some professionals with whom they go—a dancer, Rex Du Mond, and a woman named Bernice Bentley. I don't know any more of them, but I presume there is a regular organization of these social gangsters."

"Did Signor Franconi—ever go with them?" asked Craig.

"Oh, mercy, no," she hastened.

"And they can't seem to break the gang up," ruminated Craig, evidently liking her characterization of the group.

She sighed deeply and wiped away another tear. "I've done what I could with Gloria. I've cut her allowance—but it has done no good. I'm losing my hold on her altogether. You—you will help me—I mean, help Gloria?" she asked eagerly, leaning forward in an appeal which must have cost her a great deal, so common is the repression of such feelings in women of her type.

"Gladly," returned Kennedy heartily. "I will do anything in my power."

Proud though she was, Mrs. Brackett could scarcely murmur her thanks.

"Where can I see Gloria?" asked Kennedy finally.

She shook her head. "I can't say. If you want to, you may see her tomorrow, though, at the drag hunt of the club. My husband says he is not going to take Gloria's actions without a protest. So he has peremptorily ordered her to attend the meet of the Hunt Club. We thought it would get her away, at least for a time, from her associates, though I must say I can't be sure that she will obey."

I thought I understood, partly at least. Bradford Brackett's election as M. F. H. had been a crowning distinction in his social career and he did not propose to have Gloria's escapades spoil the meet for him. Perhaps he thought this as good an occasion as any to use his power to force her back into the circle to which she rightfully belonged.

Mrs. Brackett had risen. "How can I ever thank you?" she exclaimed, extending her hand impulsively. "I know nothing has been changed—yet. But already I feel better."

"I shall do what I can; depend on me," reiterated Kennedy modestly. "If I can do nothing before, I shall be out at the Hunt Club tomorrow—perhaps I shall be there anyhow."

"This is a most peculiar situation," I remarked a few minutes later, as Mrs. Brackett was whisked away from the laboratory door in her motor.

"Indeed it is," returned Kennedy, pacing up and down, his face wrinkled with thought. "I don't know whether I feel more like a detective or a spiritual adviser." He pulled out his watch. "Half-past four," he considered. "I'd like to have a look at that Cabaret Rouge here in town."

It was a perfect autumn afternoon, one of those days when one who is normal feels the call to get out of doors and enjoy what is left of the fine weather before the onset of winter. We strode along in the bracing air until at last we turned into Broadway at the upper end of what might be called "Automobile Row." Motor cars and taxicabs were buzzing along in an endless stream, most of them filled with women, gowned and bonneted in the latest mode.

Before the garish entrance of the Cabaret Rouge they seemed to pile up and discharge their feminine cargoes. We entered and were quickly engulfed in the tide of eager pleasure seekers. A handsome and judicious tip to the head waiter secured us a table at the far end of a sort of mezzanine gallery, from which we could look down over a railing at the various groups at the little white tables below. There we sat, careful to spend the necessary money to entitle us to stay, for to the average New Yorker the test seems to be not so much what one is getting for it as how much money is spent when out for a "good time."

Smooth and glittering on the surface, like its little polished dancing floor in the middle of the squares of tables downstairs, the Cabaret Rouge, one could see, had treacherous undercurrents unsuspected until an insight such as we had just had revealed them.

The very atmosphere seemed vibrant with laughter and music. A string band played sharp, staccato, highly accentuated music, a band of negroes as in many of the showy and high-priced places where a keen sense of rhythm was wanted. All around us women were smoking cigarettes. Everywhere they were sipping expensive drinks. Instinctively one felt the undertow in the very atmosphere.

I wondered who they were and where they all came from, these expensively dressed, apparently refined though perhaps only veneered girls, whirling about with the pleasantest looking young men who expertly guided them through the mazes of the fox-trot and the canter waltz and a dozen other steps I knew not of. This was one of New York's latest and most approved devices to beguile the languid afternoons of ladies of leisure.

"There she is," pointed out Kennedy finally. "I recognize her from the pictures I've seen."

I followed the direction of his eyes. The music had started and out on the floor twisting in and out among the crowded couples was one pair that seemed to attract more attention than the rest. They had come from a gay party seated in a little leather cozy corner like several about the room, evidently reserved for them, for the cozy corners seemed to be much in demand.

Gloria was well named. She was a striking girl, not much over nineteen surely, tall, lissome, precisely the figure that the modern dances must have been especially designed to set off. I watched her attentively. In fact I could scarcely believe the impression I was gaining of her.

Already one could actually see on her marks of dissipation. One does not readily think of a girl as sowing her wild oats. Yet they often do. This is one of the strange anomalies of the new freedom of woman. A few years ago such a place would have been neither so decent nor attractive. Now it was superficially both. To it went those who never would have dared overstep the strictly conventional in the evil days when the reformer was not abroad in the land.

I watched Gloria narrowly. Clearly here was an example of a girl attracted by the glamor of the life and flattery of its satellites. What the end of it all might be I preferred not to guess.

Craig was looking about at the variegated crowd. Suddenly he jogged my elbow. There, just around the turn of the railing of the gallery, sat a young man, dark of hair and eyes, of a rather distinguished foreign appearance, his face set in a scowl as he looked down on the heads of the dancers. One could have followed the tortuous course of Gloria and her partner by his eyes, which the man never took off her, even following her back to the table in the corner when the encore of the dance was finished.

The young man's face at least was familiar to me, though I had not met him. It was Signor Franconi, quietly watching Gloria and her gay party.

After a few moments, Craig rose, paid his check, and moved over to the table where Franconi was sitting alone. He introduced himself and Franconi, with easy politeness, invited us to join him.

I studied the man's face attentively. Signor Franconi was still young, in spite of the honors that had been showered on him for his many inventions. I had wondered before why such a man would be interested in a girl of Gloria's evident type. But as I studied him I fancied I understood. To his serious mind it was just the butterfly type that offered the greatest relief. An intellectual woman would have been merely carrying into another sphere the problems with which he was more than capable of wrestling. But there was no line of approval in his fine face of the butterfly and candle-singeing process that was going on here. I must say I heartily liked him.

"What are you working on now?" asked Kennedy as a preliminary step to drawing him out against the time when we might become better acquainted and put the conversation on a firmer basis.

"A system of wireless transmission of pictures," he returned mechanically. "I think I have vastly improved the system of Dr. Korn. You are familiar with it, I presume?"

Kennedy nodded. "I have seen it work," he said simply.

That telephotograph apparatus, I remembered, depended on the ability of the element selenium to vary the strength of an electric current passing through it in proportion to the brightness with which the selenium is illuminated.

"That system," he resumed, speaking as though his mind was not on the subject particularly just now, "produces positive pictures at one end of the apparatus by the successive transmission of many small parts separately. I have harnessed the alternating current in a brand-new way, I think. Instead of prolonging the operation, I do it all at once, projecting the image on a sheet of tiny selenium cells. My work is done. Now the thing to do is to convince the world of that."

"Then you have the telephote in actual operation?" asked Kennedy.

"Yes," he replied. "I have a little station down on the shore of the south side of the island." He handed us a card on which he wrote the address at South Side Beach. "That will admit you there at any time, if I should not be about. I am testing it out there—have several instruments on transatlantic liners. We think it may be of use in war—sending plans, photographs of spies—and such things."

He stopped suddenly. The music had started again and Gloria was again out on the dancing floor. It was evident that at this very important time in his career Franconi's mind was on other things.

"Everyone seems to become easily acquainted with everyone else here," remarked Craig, bending over the rail.

"I suppose one cannot dance without partners," returned Franconi absently.

We continued to watch the dancers. I knew enough of these young fellows, merely by their looks, to see that most of them were essential replicas of one type. Certainly most of them could have qualified as social gangsters, without scruples, without visible means of support, without character or credit, but not without a certain vicious kind of ambition.

They seemed to have an unlimited capacity for dancing, freak foods, joy rides, and clothes. Clothes were to them what a jimmy is to a burglar. Their English coats were so tight that one wondered how they bent and swayed without bursting. Smart clothes and smart manners such as they affected were very fascinating to some women.

"Who are they all, do you suppose?" I queried.

"All sorts and conditions," returned Kennedy. "Wall Street fellows whose pocketbooks have been thinned by dull times on the Exchange; actors out of engagements, law clerks, some of them even college students. They seem to be a new class. I don't think of any other way they could pick up a living more easily than by this polite parasitism. None of them have any money. They don't get anything from the owner of the cabaret, of course, except perhaps the right to sign checks for a limited amount in the hope that they may attract new business. It's grafting, pure and simple. The women are their dupes; they pay the bills—and even now and then something for 'private lessons' in dancing in a 'studio.'"

Franconi was dividing his attention between what Kennedy was saying and watching Gloria and her partner, who seemed to be a leader of the type I have just described, tall and spare as must be the successful dancing men of today.

"There's a fellow named Du Mond," he put in.

"Who is he?" asked Craig, as though we had never heard of him.

"To borrow one of your Americanisms," returned Franconi, "I think he's the man who puts the 'tang' in tango. From what I hear, though, I think he borrows the 'fox' from fox-trot and plucks the feathers from the 'lame duck.'"

Kennedy smiled, but immediately became interested in a tall blonde girl who had been talking to Du Mond just before the dancing began. I noticed that she was not dancing, but stood in the background most of the time giving a subtle look of appraisal to the men who sat at tables and the girls who also sat alone. Now and then she would move from one table to another with that easy, graceful glide which showed she had been a dancer from girlhood. Always after such an excursion we saw other couples who had been watching in lonely wistfulness, now made happy by a chance to join the throng.

"Who is that woman?" I asked.

"I believe her name is Bernice Bentley," replied Franconi. "She's the—well, they call her the official hostess—a sort of introducer. That's the reason why, as you observed, there is no lack of friendliness and partners. She just arranges introductions, very tactfully, of course, for she's experienced."

I regarded her with astonishment. I had never dreamed that such a thing was possible, even in cosmopolitan New York. What could these women be thinking of? Some of them looked more than capable of taking care of themselves, but there must be many, like Gloria, who were not. What did they know of the men, except their clothes and steps?

"Soft shoe workers, tango touts," muttered Kennedy under his breath.

As we watched we saw a slender, rather refined-looking girl come in and sit quietly at a table in the rear. I wondered what the official introducer would do about her and waited. Sure enough, it was not long before Miss Bentley appeared with one of the dancing men in tow. To my surprise the "hostess" was coldly turned down. What it was that happened I did not know, but it was evident that a change had taken place. Unobtrusively Bernice Bentley seemed to catch the roving eye of Du Mond while he was dancing and direct it toward the little table. I saw his face flush suddenly and a moment later he managed to work Gloria about to the opposite side of the dancing floor and, though the music had not stopped, on some pretext or other to join the party in the corner again.

Gloria did not want to stop dancing, but it seemed as if Du Mond exercised some sort of influence over her, for she did just as he wished. Was she really afraid of him? Who was the little woman who had been like a skeleton at a feast?

Almost before we knew it, it seemed that the little party had tired of the Cabaret Rouge. Of course we could hear nothing, but it seemed as if Du Mond were proposing something and had carried his point. At any rate the waiter was sent on a mysterious excursion and the party made as though they were preparing to leave.

Little had been said by either Franconi or ourselves, but it was by a sort of instinct that we, too, paid our check and moved down to the coat room ahead of them. In an angle we waited, until Gloria and her party appeared. Du Mond was not with them. We looked out of the door. Before the cabaret stood a smart hired limousine which was evidently Gloria's. She would not have dared use her own motor on such an excursion.

They drove off without seeing us and a moment later Du Mond and Bernice Bentley appeared.

"Thank you for the tip," I heard him whisper. "I thought the best thing was to get them away without me. I'll catch them in a taxi later. You're off at seven? Ritter will call for you? Then we'll wait and all go out together. It's safer out there."

Just what it all meant I could not say, but it interested me to know that young Ritter Smith and Bernice Bentley seemed on such good terms. Evidently the gay party were transferring the scene of their gayety to the country place of the Cabaret Rouge. But why?

We parted at the door with Franconi, who repeated his invitation to visit his shop down at the beach.

I started to follow Franconi out, but Kennedy drew me back. "Why did you suppose I let them go?" he explained under his breath, as we retreated to the angle again. "I wanted to watch that little woman who came in alone."

We had not long to wait. Scarcely had Du Mond disappeared when she came out and stood in the entrance while a boy summoned a taxicab for her.

Kennedy improved the opportunity by calling another for us and by the time she was ready to drive off we were able to follow her. She drove to the Prince Henry Hotel, where she dismissed the machine and entered. We did the same.

"By the way," asked Kennedy casually, sauntering up to the desk after she had stopped to get her keys and a letter, "can you tell me who that woman was?"

The clerk ran his finger down the names on the register. At last he paused and turned the book around to us. His finger indicated: "Mrs. Katherine Du Mond, Chicago."

Kennedy and I looked at each other in amazement. Du Mond was married and his wife was in town. She had not made a scene. She had merely watched. What could have been more evident than that she was seeking evidence and such evidence could only have been for a court of law in a divorce suit? The possibilities which the situation opened up for Gloria seemed frightful.

We left the hotel and Kennedy hurried down Broadway, turning off at the office of a young detective, Chase, whom he used often on matters of pure routine for which he had no time.

"Chase," he instructed, when we were seated in the office, "you recall that advertisement of the lost necklace in the Star by La Rue & Co.?"

The young man nodded. Everyone knew it. "Well," resumed Kennedy, "I want you to search the pawnshops, particularly those of the Tenderloin, for any trace you can find of it. Let me know, if it is only a rumor."

There was nothing more that we could do that night, though Kennedy found out over the telephone, by a ruse, that, as he suspected, the country place of the Cabaret Rouge was the objective of the gay party which we had seen.

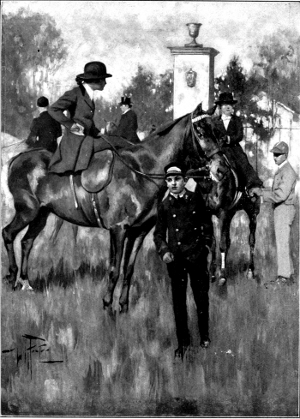

The next day was that of the hunt and we motored out to the North Shore Hunt Club. It was a splendid day and the ride was just enough to put an edge on the meet that was to follow.

We pulled up at last before the rambling colonial building which the Hunt Club boasted as its home. Mrs. Brackett was waiting for us already with horses from the Brackett stables.

"I'm so glad you came," she greeted us aside. "Gloria is here—under protest. That young man over there, talking to her, is Ritter Smith. 'Rhine' Brown, as they call him, was about a moment ago—oh, yes, there he is, coming over on that chestnut mare to talk to them. I wanted you to see them here. After the hunt, if you care to, I think you might go over to the Cabaret Rouge out here. You might find out something."

She was evidently quite proud of her handsome daughter and that anything should come up to smirch her name cut her deeply.

The Hunt Club was a swagger organization, even in these degenerate days when farmers will not tolerate broken fences and trampled crops, and when democratic ideas interfere sadly with the follies of the rich. In a cap with a big peak, a scarlet hunting coat and white breeches with top boots, Brackett himself made a striking figure of M. F. H.

There were thirty or forty in the field, the men in silk hats. For the most part one could not see that the men treated Gloria much differently. But it was evident that the women did. In fact the coldness even extended to her mother, who would literally have been frozen out if it had not been for her quasi-official position. I could see now that it was also a fight for Mrs. Brackett's social life.

As we watched Gloria, we could see that Franconi was hovering around, unsuccessfully trying to get an opportunity to say a word to her alone. Just before we were off a telegram came to her, which she read and hastily stuffed into a pocket of her riding habit.

But that was all that happened and I fell to studying the various types of human nature, from the beginner who rode very hard and very badly and made himself generally odious to the M. F. H., to the old seasoned hunter who talked of the old days of real foxes and how he used to know all the short cuts to the coverts.

It was a keen, crisp day. Already a man had been over the field pulling along the ground a little bag of aniseed, and now the hunt was about to start.

Noses down, sterns feathering zigzag over the ground, sniffing earth and leaves and grass, the hounds were brought up. One seemed to get a good whiff of the trail and lifted his head with a half yelp, half whine, high pitched, frenzied, never-to-be-forgotten. Others joined in the music. "Gone away!" sounded a huntsman as if there were a real fox. We were off after them. Drag hounds, however, for the most part run mute and very fast, so that that picturesque feature was missing. But the light soil and rail fences of Long Island were ideal for drag hunting. Nor was it so easy as it seemed to follow. Also there was the spice of danger, risk to the hunters, the horses and the dogs.

We went for four or five miles. Then there was a check for the stragglers to come up. Some had fresh mounts, and all of us were glad of the breathing space while the M. F. H. "held" the hounds.

While we waited we saw that Mrs. Brackett was riding about quickly, as if something were on her mind. A moment she stopped to speak to her husband, then galloped over to us.

Her face was almost white. "Gloria hasn't come up with the rest!" she exclaimed breathlessly.

Already Brackett had told those about him and all was confusion. It was only a moment when the members of the hunt were scouring the country over which we had passed, with something really definite to find.

Kennedy did not pause. "Come on, Walter," he shouted, striking out down the road, with me hard after him.

We pulled up before a road-house of remarkable quaintness and luxury of appointment, one of the hundreds about New York which the automobile has recreated. Before it swung the weathered sign: Cabaret Rouge.

To our hurried inquiries the manager admitted that Du Mond had been there, but alone, and had left, also alone. Gloria had not come there.

A moment later sounds of hoofs on the hard road interrupted us and Ritter Smith dashed up.

"Just overtook a farmer down the road," he panted. "Says he saw an automobile waiting at the stone bridge and later it passed him with a girl and a man in it. He couldn't recognize them. The top was up and they went so fast."

Together we retraced the way to the stone bridge. Sure enough, there on the side of the road were marks where a car had pulled up. The grass about was trampled and as we searched Kennedy reached down and picked up something white. At least it had been white. But now it was spotted with fresh blood, as though someone had tried to stop a nose-bleed.

He looked at it more closely. In the corner was embroidered a little "G."

Evidently there had been a struggle and a car had whizzed off. Gloria was gone. But with whom? Had the message which we had seen her read at the start been from Du Mond? Was the plan to elope and so avoid his wife? Then why the struggle?

Absolutely nothing more developed from the search. An alarm was at once sent out and the police all over the country notified. There was nothing to do now but wait. Mrs. Brackett was frantic. But it was not now the scandal that worried her. It was Gloria's safety.

That night, in the laboratory, Kennedy took the handkerchief and with the blood on it made a most peculiar test before a strange-looking little instrument.

It seemed to consist of a little cylinder of glass immersed in water kept at the temperature of the body. Between two minute wire pincers or serres, in the cylinder, was a very small piece of some tissue. To the lower serre was attached a thread. The upper one was attached to a sort of lever ending in a pen that moved over a ruled card.

"Every emotion," remarked Kennedy as he watched the movement of the pen in fine zigzag lines over the card, "produces its physiological effect. Fear, rage, pain, hunger are primitive experiences, the most powerful that determine the actions of man. I suppose you have heard of the recent studies of Dr. Walter Cannon of Harvard of the group of remarkable alterations in bodily economy under emotion?"

I nodded and Kennedy resumed. "On the surface one may see the effect of blood vessels contracting, in pallor; one may see cold sweat, or the saliva stop when the tongue cleaves to the roof of the mouth, or one may see the pupils dilate, hairs raise, respiration become quick, or the beating of the heart, or trembling of the muscles, notably the lips. But one cannot see such evidences of emotion if he is not present at the time. How can we reconstruct them?"

He paused a moment, then resumed. "There are organs hidden deep in the body which do not reveal so easily the emotions. But the effect often outlasts the actual emotion. There are special methods by which one can study the feelings. That is what I have been doing here."

"But how can you?" I queried.

"There is what is called the sympathetic nervous system," he explained. "Above the kidney there are also glands called the suprarenal which excrete a substance known as adrenin. In extraordinarily small amounts adrenin affects this sympathetic system. In emotions of various kinds a reflex action is sent to the suprarenal glands which causes a pouring into the blood of adrenin.

"On the handkerchief of Gloria Brackett I obtained plenty of comparatively fresh blood. Here in this machine I have between these two pincers a minute segment of rabbit intestine."

He withdrew the solution from the cylinder with a pipette, then introduced some more of the dissolved blood from the handkerchief. The first effect was a strong contraction of the rabbit intestine, then in a minute or so the contractions became fairly even with the base line on the card.

"Such tissue," he remarked, "is noticeably affected by even one part in over a million of adrenin. See. Here, by the writing lever, the rhythmical contractions are recorded. Such a strip of tissue will live for hours, will contract and relax beautifully with a regular rhythm which, as you see, can be graphically recorded. This is my adrenin test."

Carefully he withdrew the ruled paper with its tracings.

"It's a very simple test after all," he said, laying beside this tracing another which he had made previously. "There you see the difference between what I may call 'quiet blood' and 'excited blood.'"

I looked at the two sets of tracings. Though they were markedly different, I did not, of course, understand what they meant. "What do they show to an expert?" I asked, perplexed.

"Fear," he answered laconically. "Gloria Brackett did not go voluntarily. She did not elope. She was forced to go!"

"Attacked and carried off?" I queried.

"I did not say that," he replied. "Perhaps our original theory that her nose was bleeding may be correct. It might have started in the excitement, the anger and fear at what happened, whatever it was. Certainly the amount of adrenin in her blood shows that she was laboring under strong enough emotion."

Our telephone rang insistently and Kennedy answered it. As he talked, although I could hear only one side of the conversation, I knew that the message was from Chase and that he had found something important about the missing necklace.

"What was it?" I asked eagerly as he hung up the receiver.

"Chase has traced the necklace," he reported; "that is, he has discovered the separate stones, unset, pawned in several shops. The tickets were issued to a girl whose description exactly fits Gloria Brackett."

I could only stare at him. What we had all feared had actually taken place. Gloria must have taken the necklace herself. Though we had feared it and tried to discount it, nevertheless the certainty came as a shock.

"Why should she have taken it?" I considered.

"For many possible reasons," returned Kennedy. "You saw the life she was leading. Her own income probably went to keeping those harpies going. Besides, her mother had cut her allowance. She may have needed money very badly."

"Perhaps they had run her into debt," I agreed, though the thought was disagreeable.

"How about that other little woman we saw?" suggested Kennedy. "You remember how Gloria seemed to stand in fear of Du Mond? Who knows but that he made her get it to save her reputation? A girl in Gloria's position might do many foolish things. But to be named as co-respondent, that would be fatal."

There was not much comfort to be had by either alternative, and we sat for a moment regarding each other in silence.

Suddenly the door opened. Mrs. Brackett entered. Never have I seen a greater contrast in so short a time than that between the striking society matron who first called on us and the broken woman now before us. She was a pathetic figure as Kennedy placed an easy chair for her.

"Why, what's the matter?" asked Kennedy. "Have you heard anything new?"

She did not answer directly, but silently handed him a yellow slip of paper. On a telegraph blank were written simply the words, "Don't try to follow me. I've gone to be a war nurse. When I make good I will let you know. Gloria."

We looked at each other in blank amazement. That was hardly an easy way to trace her. How could one ever find out now where she was, in the present state of affairs abroad, even supposing it were not a ruse to cover up something?

Somehow I felt that the message did not tell the story. Where was Du Mond? Had he fled, too,—perhaps forced her to go with him when Mrs. Du Mond appeared? The message did not explain the struggle and the fear.

"Oh, Mr. Kennedy," pleaded Mrs. Brackett, all thought of her former pride gone, as she actually held out her hands imploringly and almost fell on her knees, "can't you find her—can't you do something?"

"Have you a photograph of Gloria?" he asked hurriedly.

"Yes," she cried eagerly, reaching into her mesh bag and drawing one out. "I carry it with me always. Why?"

"Come," exclaimed Kennedy, seizing it. "It occurs to me that it is now or never that this device of Franconi's must prove that it is some good. If she really went, she wasted no time. There's just a bare chance that the telephote has been placed on some of these vessels that are carrying munitions abroad. Franconi says that he has developed it for its war value."

As fast as Mrs. Brackett's chauffeur could drive us, we motored down to South Side Beach and sought out the little workshop directly on the ocean where Franconi had told us that we should always be welcome.

He was not there, but an assistant was. Kennedy showed him the card that Franconi had given us.

"Show me how the machine works," he asked, while Mrs. Brackett and I waited aside, scarcely able to curb our impatience.

"Well," began the assistant, "this is a screen of very minute and sensitive selenium cells. I don't know how to describe the process better than to say that the tones of sound, the human voice, have hundreds of gradations which are transmitted, as you know, by wireless, now. Gradations of light, which are all that are necessary to produce the illusion of a picture, are far simpler than those of sound. Here, in this projector—"

"That is the transmitting part of the apparatus?" interrupted Kennedy brusquely. "That holder?"

"Yes. You see there are hundreds of alternating conductors and insulators, all synchronized with hundreds of similar receivers at the—"

"Let me see you try this photograph," interrupted Kennedy again, handing over the picture of Gloria which Mrs. Brackett had given him. "Signor Franconi told me he had the telephote on several outgoing liners. Let me see if you can transmit it. Is there any way of sending a wireless message from this place?"

The assistant had shoved the photograph into the holder from which each section was projected on the selenium cell screen.

"I have a fairly powerful plant here," he replied.

Quickly Kennedy wrote out a message, briefly describing the reason why the picture was transmitted and asking that any station on shipboard that received it would have a careful search made of the passengers for any young woman, no matter what name was assumed, who might resemble the photograph.

Though nothing could be expected immediately at best, it was at least some satisfaction to know that through the invisible air waves, wirelessly, the only means now of identifying Gloria was being flashed far and wide to all the big ships within a day's distance or less on which Franconi had established his system as a test.

The telephote had finished its work. Now there was nothing to do but wait. It was a slender thread on which hung the hope of success.

While we waited, Mrs. Brackett was eating her heart out with anxiety. Kennedy took the occasion to call up the New York police on long distance. They had no clew to Gloria. Nor had they been able to find a trace of Du Mond. Mrs. Du Mond also had disappeared. At the Cabaret Rouge, Bernice Bentley had been held and put through a third degree, without disclosing a thing, if indeed she knew anything. I wondered whether, at such a crisis, Du Mond, too, might not have taken the opportunity to flee the country.

We had almost given up hope, when suddenly a little buzzer on the telephote warned the operator that something was coming over it.

"The Monfalcone," he remarked, interpreting the source of the impulses.

"We gathered breathlessly about the complicated instrument as, on a receiving screen composed of innumerable pencils of light polarized and acting on a set of mirrors, each corresponding to the cells of the selenium screen and tuned to them, as it were, a thin film or veil seemed gradually to clear up, as the telephote slowly got itself into equilibrium at both ends of the air line. Gradually the face of a girl appeared.

"Gloria!" gasped Mrs. Brackett in a tone that sounded as if ten years had been added to her life.

"Wait," cautioned the operator. "There is a written message to follow."

On the same screen now came in letters that Mrs. Brackett in her joy recognized the message: "I couldn't help it. I was blackmailed into taking the necklace. Even at the hunt I received another demand. I did not mean to go, but I was carried off by force before I could pay the second demand. Now I'm glad of it. Forgive us. Gloria."

"Us?" repeated Mrs. Brackett, not comprehending.

"Look—another picture," pointed Kennedy.

We bent over as the face of a man seemed to dissolve more clearly in place of the writing.

"Thank God!" exclaimed Mrs. Brackett fervently, reading the face by a sort of intuition before it cleared enough for us to recognize. "He has saved her from herself!"

It was Franconi!

Slowly it faded and in its place appeared another written message.

"Recalled to Italy for war service. I took her with me by force. It was the only way. Civil ceremony in New York yesterday. Religious will follow at Rome."

"My husband has such a jealous disposition. He will never believe the truth—never!"

Agatha Seabury moved nervously in the deep easy chair beside Kennedy's desk, leaning forward, uncomfortably, the tense lines marring the beauty of her fine features.

Kennedy tilted his desk chair back in order to study her face.

"You say you have never written a line to the fellow nor he to you?" he asked.

"Not a line, not a scrap,—until I received that typewritten letter about which I just told you," she repeated vehemently, meeting his penetrating gaze without flinching. "Why, Professor Kennedy, as heaven is my witness, I have never done a wrong thing—except to meet him now and then at afternoon dances."

I felt that the nerve-racked society woman before us must be either telling the truth or else that she was one of the cleverest actresses I had ever seen.

"Have you the letter here?" asked Craig quickly.

Mrs. Seabury reached into her neat leather party case and pulled out a carefully folded sheet of note paper.

It was all typewritten, down to the very signature itself. Evidently the blackmailer had taken every precaution to protect himself, for even if the typewriting could be studied and identified, it would be next to impossible to get at the writer through it and locate the machine on which it was written among the thousands in the city.

Kennedy studied the letter carefully, then, with a low exclamation, handed it over to me, nodding to Mrs. Seabury that it was all right for me to see it.

"No ordinary fellow, I'm afraid," he commented musingly, adding, "this thief of reputations."

I read, beginning with the insolent familiarity of "Dear Agatha."

"I hope you will pardon me for writing to you," the letter continued, "but I find that I am in a rather difficult position financially. As you know, in the present disorganized state of the stock market, investments which in normal times are good are now almost valueless. Still, I must protect those I already have without sacrificing them.

"It is therefore necessary that I raise fifty thousand dollars before the end of the week, and I know of no one to appeal to but you—who have shared so many pleasant stolen hours with me.

"Of course, I understand all that you have told me about Mr. Seabury and his violent nature. Still, I feel sure that one of your wealth and standing in the community can find a way to avoid all trouble from that quarter. Naturally, I should prefer to take every precaution to prevent the fact of our intimacy from coming to Mr. Seabury's knowledge. But I am really desperate and feel that you alone can help me.

"Hoping to hear from you soon, I am,

"Your old tango friend,

"H. Morgan Sherburne."

I fairly gasped at the thinly veiled threat of exposure at the end of the note from this artistic blackmailer.

She was watching our faces anxiously as we read.

"Oh," she cried wildly, glancing from one to the other of us, strangers to whom in her despair she had been forced to bare the secrets of her proud heart, "he's so clever about it, too. I—I didn't know what to do. I had only my jewels. I thought of all the schemes I had ever read, of pawning them, of having paste replicas made, of trying to collect the burglary insurance, of—"

"But you didn't do anything like that, did you?" interrupted Craig hastily.

"No, no," she cried. "I thought if I did, then it wouldn't be long before this Sherburne would be back again for more. Oh," she almost wailed, dabbing at the genuine tears with her dainty lace handkerchief while her shoulders trembled with a repressed convulsive sob, "I—I am utterly wretched—crushed."

"The scoundrel!" I muttered.

Kennedy shook his head at me slowly. "Calling names won't help matters now," he remarked tersely. Then in an encouraging tone he added, "You have done just the right thing, Mrs. Seabury, in not starting to pay the blackmail. The secret of the success of these fellows is that their victims prefer losing jewelry and money to going to the police and having a lot of unpleasant notoriety."

"Yes, I know that," she agreed hastily, "but—my husband! If he hears, he will believe the worst, and—I—I really love and respect Judson—though," she added, "he might have seen that I liked dancing and—innocent amusements of the sort still. I am not an old woman."

I could not help wondering if the whole truth were told in her rather plaintive remark, or whether she was overplaying what was really a minor complaint. Judson Seabury, I knew from hearsay, was a man of middle age to whom, as to so many, business and the making of money had loomed as large as life itself. Competitors had even accused him of being ruthless when he was convinced that he was right, and I could well imagine that Mrs. Seabury was right in her judgment of the nature of the man if he became convinced for any reason that someone had crossed his path in his relations with his wife.

"Where did you usually—er—meet Sherburne?" asked Craig, casually guiding the conversation.

"Why—at the Vanderveer—always," she replied.

"Would you mind meeting him there again this afternoon so that I could see him?" asked Kennedy. "Perhaps it would be best, anyhow, to let him think that you are going to do as he demands, so that we can gain a little time."

She looked up, startled. "Yes—I can do that—but don't you think it is risky? Do you think there is any way I can get free from him? Suppose he makes a new demand. What shall I do? Oh, Professor Kennedy, you do not, you cannot know what I am going through—how I hate and fear him."

"Mrs. Seabury," reassured Craig earnestly, "I'll take up your case. Clever as the man is, there must be some way to get at him."

Sherburne must have exercised a sort of fascination over her, for the look of relief that crossed her face as Kennedy promised to aid her was almost painful. As often before, I could scarcely envy Kennedy in his ready assumption of another's problems that seemed so baffling. It meant little, perhaps, to us whether we succeeded. But to her it meant happiness, perhaps honor itself.

It was as though she were catching at a life line in the swirling current of events that had engulfed her. She hesitated no longer.

"I'll be there—I'll meet him—at four," she murmured, as she rose and made a hurried departure.

For some time after she had gone, Kennedy sat considering what she had told us. As for myself, I cannot say that I was thoroughly satisfied that she had told all. It was not to be expected.

"How do you figure that woman out?" I queried at length.

Kennedy looked at me keenly from under knitted brows. "You mean, do I believe her story—of her relations with this fellow, Sherbourne?" he returned, thoughtfully.

"Exactly," I assented, "and what she said about her regard for her husband, too."

Kennedy did not reply for a few minutes. Evidently the same question had been in his own mind and he had not reasoned out the answer. Before he could reply the door buzzer sounded and the colored boy from the lower hall handed a card to Craig, with an apology about the house telephone switchboard being out of order.

As Kennedy laid the card on the table before us, with a curt "Show the gentleman in," to the boy, I looked at it in blank amazement.

It read, "Judson Seabury."

Before I could utter a word of comment on the strange coincidence, the husband was sitting in the same chair in which his wife had sat less than half an hour before.

Judson Seabury was a rather distinguished looking man of the solid, business type. Merely to meet his steel gray eye was enough to tell one that this man would brook no rivalry in anything he undertook. I foresaw trouble, even though I could not define its nature.

Craig twirled the card in his fingers, as if to refresh his mind on a name otherwise unfamiliar. I was wondering whether Seabury might not have trailed his wife to our office and have come to demand an explanation. It was with some relief that I found he had not.

"Professor Kennedy," he began nervously, hitching his chair closer, without further introduction, in the manner of a man who was accustomed to having his own way in any matter he undertook, "I am in a most peculiar situation."

Seabury paused a moment, Kennedy nodded acquiescence, and the man suddenly blurted out, "I—I don't know whether I'm being slowly poisoned or not!"

The revelation was startling enough in itself, but doubly so after the interview that had just preceded.

I covered my own surprise by a quick glance at Craig. His face was impassive as he narrowly searched Seabury's. I knew, though, that back of his assumed calm, Craig was doing some rapid thinking about the ethics of listening to both parties in the case. However, he said nothing. Indeed, Seabury, once started, hurried on, scarcely giving him a chance to interrupt.

"I may as well tell you," he proceeded, with the air of a man who for the first time is relieving his mind of something that has been weighing heavily on him, "that for some time I have not been exactly—er—easy in my mind about the actions of my wife."

Evidently he had arrived at the conclusion to tell what worried him, and must say it, for he continued immediately: "It's not that I actually know anything about any indiscretions on Agatha's part, but,—well, there have been little things—hints that she was going frequently to thés dansants, and that sort of thing, you know. Lately, too, I have seen a change in her manner toward me, I fancy. Sometimes I think she seems to avoid me, especially during the last few days. Then again, as this morning, she seems to be—er—too solicitous."

He passed his hand over his forehead, as if to clear it. For once he did not seem to be the self-confident man who had at first entered our apartment. I noticed that he had a peculiar look, a feeble state of the body which he was at times at pains to conceal, a look which the doctors call, I believe, cachectic.

"I mean," he added hastily, as if it might as well be said first as last, "that she seems to be much concerned about my health, my food—"

"Just what is it that you actually know, not what you fear?" interrupted Kennedy, perhaps a little brusquely, at last having seen a chance to insert a word edgewise into the flow of Seabury's troubles, real or imaginary.

Seabury paused a moment, then resumed with a description of his health, which, to tell the truth, was by no means reassuring.

"Well," he answered slowly, "I suffer a good deal from such terrible dyspepsia, Professor Kennedy. My stomach and digestion are all upset—bad health and growing weakness—pain, discomfort—vomiting after meals, even bleeding. I've tried all sorts of cures, but still I can feel that I am still losing health and strength, and, so far, at least, the doctors don't seem to be doing me much good. I have begun to wonder whether it is a case for the doctors, after all. Why, the whole thing is getting on my nerves so that I'm almost afraid to eat," he concluded.

"You have eaten nothing today, then, I am to understand?" asked Craig when Seabury had finished with his minute and puzzling account of his troubles.

"Not even breakfast this morning," he replied. "Mrs. Seabury urged me to eat, but—I—I couldn't."

"Good!" exclaimed Kennedy, much to our surprise. "That will make it just so much easier to use a test I have in mind to determine whether there is anything in your suspicions."

He had risen and gone over to a cabinet.

"Would you mind baring your arm a moment?" he asked Seabury.

With a sharp little instrument, carefully sterilized, Craig pricked a vein in the man's arm. Slowly a few drops of darkened venous blood welled out. A moment later Kennedy caught them in a sterile test tube and sealed the tube.

Before our second visitor could start again in retailing his suspicions which now seemed definitely, in his own mind at least, directed in some way against Mrs. Seabury, Kennedy skillfully closed the interview.

"I feel sure that the test I shall make will tell me positively, soon, whether your fears are well grounded or not, Mr. Seabury," he concluded briefly, as he accompanied the man out into the hall to shake hands farewell with him at the elevator door. "I'll let you know as soon as anything develops, but until we have something tangible there is no use wasting our energies."

I felt, however, that Seabury accepted this conclusion reluctantly, in fact with a sort of mental reservation not to cease activity himself.

The remainder of the forenoon, and for some time during the early afternoon, Craig plunged into one of his periods of intense work and abstraction at the laboratory.

It was, indeed, a most unusual and delicate test which he was making. For one thing, I noticed that he had, in a sterilizer, some peculiar granular tissue that had been sent to him from a hospital. This tissue he was very careful to cleanse of blood and then by repeated boilings prepare for whatever use he had in mind.

As for myself, I could only stand aside and watch his preparations in silence. Among the many peculiar pieces of apparatus which he had, I recall one that consisted of a glass cylinder with a siphon tube running into it halfway up the outside. Inside was another, smaller cylinder. All about him as he proceeded were glass containers, capillary pipettes, test tubes, Bunsen burners, and dialyzers of porous parchment paper whose wrappers described them as "permeable for peptones, but not for albumins."

Carefully set aside was the blood which he had drawn from Seabury's veins, allowed to stand till the serum separated out from the clot. Next he pipetted it into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged it at high speed, some sixteen thousand revolutions, until the serum was perfectly clear, with no trace of a reddish tint, nor even cloudy. After that he drew off the serum into a little tube, covered it with a layer of a substance called toluol from another sterile pipette, and finally placed it in an incubator at a temperature of about ninety-eight.

It was well along toward four o'clock when he paused as if some mental alarm clock had awakened him to another part of the plan of action he had laid out.

"Walter," he remarked, hastily doffing his stained old laboratory coat, "I think we'd better drop around to the Vanderveer."

Curious as I had been at the preparations he was making in the laboratory, I was still glad at even the suggestion of something that my less learned mind could understand and it was not many seconds before we were on our way.

Through the lobby of the famous new hostelry we slowly lounged along, then down a passage into the tea room, where, in the center of a circle of quaint little wicker chairs and tables, was a glossy dancing floor.

Kennedy selected a table not in the circle, but around an "L," inconspicuously located so that we could watch the dancing without ourselves being watched.

At one end of the room an excellent orchestra was playing. I gazed about, fascinated. At the dancing tea was represented, apparently, much wealth—women whose throats and fingers glittered with gold and gems, men whose very air exuded prosperity—or at least its veneer.

About it all was the glamor of the risqué. One felt a sort of compromising familiarity in this breaking down of old social restraints through the insidious influence of the tea room, with its accompaniments of music and dancing.

"I suppose," remarked Craig after we had for some time settled ourselves and watched the brilliant scene, "that, like many others, Walter, you have often wondered whether these modern dances are actually as stimulating as they seem."

I shrugged my shoulders non-committally.

"Well, there is what psychologists might call a real dance neurosis," he went on, contemplatively, toying with a glass. "In fact few persons can withstand the physical effect of the peculiar rhythm, the close contact, and the sinuous movements—at least where, so to speak, the surroundings are suggestive and the dance becomes less restrained and more sensuous, as it does often in circumstances like these, often among strangers."

The music had started again and one after another couples seemed to float past in unhesitating hesitation—dowager and débutante, dandy and doddering octogenarian.

"Why," he exclaimed, looking out at the whirling kaleidoscope, "here in the most advanced epoch, people of culture and intelligence frankly say they are 'wild' for something primitive."

"Still," I objected, "dancing even in the wild, stimulating emotional manner you see here need not be merely an incitement to love, need it? May it not be a normal gratification of the love instinct—eroticism translated into rhythm? Perhaps it may represent sex, but not necessarily badly."

Kennedy nodded. "Undoubtedly the effect of the dances is in direct ratio to the sexual temperament of the dancer," he admitted.

He paused and again watched the whirl.

"Does Mrs. Seabury herself understand it?" he mused, only half speaking to me. "I'm sure that this Sherburne is clever enough to do so, at any rate."

A hearty round of applause came from the dancers as the music ceased. None left the floor, however, but remained waiting for the encore eagerly, scarcely changing the positions in which they had stopped.

"To my mind," Kennedy resumed, with the music, "several things seem significant. Many people have noticed that after marriage women generally lose much of their ardor for dancing. I feel that it is an unsafe matter on which to generalize, but—well—Mrs. Seabury seems not to have lost it."

"Then," I inquired quickly, "you imply that—she is not really as much in love with her husband as she would have us think—or, perhaps, herself believes?"

"Not quite that," he replied doubtfully. "But I am wondering whether there is such a factor that must be considered."

Before I could answer Kennedy touched my arm. Instinctively I followed the direction of his eye and saw Mrs. Seabury step out on the floor across from us. Without a word from Craig, I realized that the man with her must be Sherburne, our "tango thief."

Fashionably dressed, affable, seemingly superficially, at least, well educated, tall, graceful, with easy manners, I could not help seeing at a glance that he was one of the most erotic dancers on the little floor.

As they passed near us, Mrs. Seabury caught Kennedy's eye in momentary recognition. Her face, flushed with the dance, colored perhaps a shade deeper, but not noticeably to her partner, who was devoting himself wholly and skillfully to leading her in a manner that one could see called forth frequent comment from others, less favored.

As they sat down after this dance and the encore, Craig motioned to the waiter at our table and whispered to him.

A few moments later, a man whom I had seen around the hotel on my infrequent visits, but did not know, slipped quietly into a seat beside Kennedy, even deeper in the shadow of the recess in which we were sitting.

"Walter, I'd like to have you meet Mr. Dunn, the house detective," whispered Kennedy under his breath.

The usual interchange of remarks followed, during which Dunn was evidently waiting for Kennedy to reveal the real purpose of our visit.

"By the way, Dunn," remarked Craig at length, "who is that fellow—over there with the woman in blue—the fellow with the heavy braided coat?"

Dunn craned his neck cautiously, then shrugged his shoulders. "I've seen him here with her before," he remarked. "I don't know him, though. Why?"

Briefly Kennedy sketched such facts of a supposedly hypothetical case as would be likely to secure an opinion from the house man. Dunn narrowed his eyes thoughtfully.

"That's rather a ticklish situation, Kennedy," Dunn remarked when Craig had stated the case, omitting all reference to Seabury's name as well as his suspicions. "Of course," he went on, "I know we've got to protect the name of the hotel. And I know we can't have men meeting our women patrons, doing a gavotte or two—and then fox-trotting them into blackmail."

Dunn stroked his chin thoughtfully. "You see, we can do a great deal to suppress card sharps, agents for fake mining stocks, passers of worthless checks, and confidence men of that sort. But it is not so simple to thwart the vultures who prey on the gullibility and passions of the so-called idle rich."

"There must be something you can do to get it on this fellow, though," persisted Craig.

"Well," considered the house man, "we have what might be called our hotel secret service—several men and women operating entirely apart from the hotel force of detectives who, like myself, are too well known to clever crooks. Nobody knows them, except myself. There's one—that girl over there dancing with that middle-aged man who has mail sent here but doesn't live here. Could they be of use?"

"Just the thing," exclaimed Craig enthusiastically. "Can't you have her get acquainted—just as a precaution—with that man? His name, by the way, I understand is Sherburne."

"I'll do it," agreed Dunn, rising unostentatiously.

Just then I happened to glance across the floor and over the heads of those seated at the tables at a door opposite us. It was my turn hastily to seize Kennedy's elbow.

"Good God!" I exclaimed involuntarily.

There, in the further doorway of the tea room, stood Judson Seabury himself!

Without a word, Craig rose and quickly crossed the dancing floor, stopping before Mrs. Seabury's table. Instead of waiting to be introduced, he sat down deliberately, as though he had been there all the time and had just gone out of the room and come back. He did it all so quickly that he was able in a perfectly natural way to turn and see that Seabury himself had been watching and now was advancing slowly, picking his way among the crowded tables.

From around my corner I saw Craig whisper a word or two to Mrs. Seabury, then rise and meet Seabury less than halfway from the door by which he had been standing.

The tension of the situation was too much for Mrs. Seabury. Confounded and bewildered, she fled precipitately, passing within a few feet of my table. Her face was positively ghastly.

As for Sherburne, he merely sat a moment and surveyed the irate husband with calm and studied insolence at a safe distance. Then he, too, rose and turned deliberately on his heel.

Curious to know how Craig would meet the dilemma, I watched eagerly and was surprised to see Seabury, after a moment's whispered talk, turn and leave the tea room by the same door through which he had entered.

"What did you do?" I asked, as Craig rejoined me a few moments later. "What did you say? My hat's off to you," I added in admiration.

"Told him I had trailed her here with one of my operatives, but was convinced there was nothing wrong, after all," he returned.

"You mean," I asked as the result of Craig's quick thinking dawned on me, "that you told him Sherburne was your operative?"

Kennedy nodded. "I want to see him, now, if I can," he said simply.

We paid our check and Kennedy and I sauntered in the direction Sherburne had taken, finding him ultimately in the cafe, alone. Without further introduction Kennedy approached him.

"So—you are a detective?" sneered Sherburne superciliously, elevating his eyebrows just the fraction of an inch.

"Not exactly," parried Kennedy, seating himself beside Sherburne. Then in a tone as if he were willing to get down, without further preliminary, to business, seemingly negotiating, he asked: "Mr. Sherburne, may I ask just what it is on which you base your claim on Mrs. Seabury? Is it merely meeting her here? If that is so you must know that it amounts to nothing—now."

The two men faced each other, each taking the other's measure.

"Nothing?" coolly retorted Sherburne. "Perhaps not—in itself. But—suppose—I—had—"

He said the words slowly, as he fumbled in his fob pocket, then cut them short as he found what he was looking for. Safely, in the palm of his hand, he displayed a latch-key, momentarily, then with a taunting smile dropped it back again into the fob pocket.

"Perhaps she gave it to me—perhaps I was a welcome visitor in her apartment," he insinuated. "How would she relish having that told to Mr. Seabury—backed up by the possession of the key?"

I could not help feeling that for the moment Kennedy was checkmated. Sherburne was playing a desperate game and apparently held the key, however he got it, as a trump card.

"Thank you," was all that Kennedy said, as he rose. "I wanted to know how far you could go. Perhaps we can meet you halfway."

Sherburne smiled cynically. "All the way," he said quietly, as we left the cafe.

In silence Kennedy left the hotel and jumped into a cab, directing the driver to the laboratory, where he had asked Mrs. Seabury to wait for him. We found her there, still much agitated.

Hastily Craig explained to her how he had saved the situation, but her mind was too occupied over something else to pay much attention.

"I—I can't blame you, Professor Kennedy," she cried, choking down a sob in her voice, "but I have just discovered—he has told me that it is even worse than I had anticipated."

We were both following her closely, the incident of the latch-key still fresh in mind.

"Some time ago," she hurried on, "I missed my latch-key. I thought nothing of it at the time—thought perhaps I had mislaid it. But today he told me—just after the dance, even while I was making him think I would pay him the money, because—because I liked him—he told me he had it. The brute! He must have picked my handbag!"

Her eyes were blazing now with indignation. Yet as she looked at us both, evidently the recollection of what had just happened came flooding over her mind, and she dropped her head in her hands in helpless dismay at the new development.

Craig pulled out his watch hastily. "It is about six, Mrs. Seabury," he reassured. "Can you be here at, say, eight?"

"I will be here," she murmured pliantly, realizing her own helplessness.

She had scarcely closed the door when Craig seized the telephone, and hurriedly tried to locate Seabury himself.

"Apparently no trace of him yet," he fumed, as he hung up the receiver. "The first problem is how to get that key."

Instantly I thought of Dunn's secret service girl. Kennedy shook his head doubtfully. "I'm afraid there is no time for that," he answered. "But will you attend to that end of the affair for me, Walter? I have just a little more work here at the laboratory before I am ready. I don't care how you do it, but I want you to convey to Sherburne the welcome news that Mrs. Seabury is prepared to give in, in any way he may see fit, if he will call her up here at eight o'clock."

Kennedy had already plunged back among his beakers and test tubes, and with these slender instructions I sallied forth in my quest of Sherburne. I had little difficulty in locating him and delivering my message, which he received with a satisfaction that invited assault and battery and mayhem. However, I managed to restrain myself and rejoin Craig in the laboratory, shortly after seven o'clock.

I had scarcely had time to assure Kennedy of the success of my mission, when we were surprised to see the door open and Seabury himself appear.

His face was actually haggard. Whether or not he had believed the hastily concocted story of Kennedy at the Vanderveer, his mind had not ceased to work on the other fears that had prompted his coming to us in the first place.

"I've been trying to locate you all over," greeted Craig.

Seabury heaved a sigh and passed his hand, with its familiar motion, over his forehead. "I thought perhaps you might be able to find out something from this stuff," he answered, unwrapping a package which he was carrying. "Some samples of the food I've been getting. If you don't find anything in this, I've others I want tested."

As I looked at the man's drawn face, I wondered whether in fact there might be something in his fears. On the surface, the thing did indeed seem to place Agatha Seabury in a bad light. At the sight of the key in Sherburne's possession I had grasped at the straw that he might have conceived some diabolical plan to get rid of Seabury for purposes of his own. But then, I reasoned, would he have been so free in showing the key if he had realized that it might cast suspicion on himself? I was forced to ask myself again whether she might, in her hysterical fear of exposure by the adroit blackmailer, have really attempted to poison her husband.

It was a desperate situation. But Kennedy was apparently ready to meet it, though he seemed to take no great interest in the food samples Seabury had just brought.

Instead he seemed to rely wholly on the tests he had already begun with the peculiar tissue I had seen him boiling and the blood serum derived from Seabury himself.

Without a word he took three tubes from the incubator, in which I had seen him place them some time before, and, as they stood in a rack, indicated them lightly with his finger.

"I think I can clear part of this mystery up immediately," he began, speaking more to himself than to Seabury and myself. "Here I have a tested dialyzer in which has been placed a half cubic centimeter of pure clear serum. Here is another dialyzer with the same amount of serum, but no tissue, such as Mr. Jameson has seen me place in this first one. Here is still another with the tissue in distilled water, but no blood serum. I have placed all the dialyzers in tubes of distilled water and all are covered with a substance known as toluol and corked to keep them from contamination."

Kennedy held up before us the three tubes and Seabury gazed on them with a sort of fascination, scarcely believing that in them in some way might be contained the verdict on the momentous problem that troubled his mind and might perhaps mean life or death to him.

Carefully Kennedy took from each tube a few cubic centimeters of the dialyzate and into each he poured a little liquid from a tiny vial which I noticed was labelled "Ninhydrin."

"This," he explained as he set down the vial, "is a substance which gives a colorless solution with water, but when mixed with albumins, peptones, or amino-acids becomes violet on boiling. Tube number three must remain colorless. Number two may be violet. Number one may approximate number two or be more deeply colored. If one and two are about the same I call my test negative. But if one is more deeply colored than two, then it is positive. The other tube is the control."

Impatiently we waited as the three tubes simmered over the heat. What would they show? Seabury's eyes were glued on them, his hand trembling in the presence of some unknown danger.

Slowly the liquid in the second tube turned to violet. But more rapidly and more deeply appeared the violet in number one. The test was positive.

"What is it?" gasped Seabury hoarsely, leaning over close.

"This," exclaimed Kennedy, "is the famous Abderhalden test—serum-diagnosis—discovered by Professor Emile Abderhalden of Halle. It rests on the fact that when a foreign substance comes into the blood, the blood reacts, with the formation of a protective ferment produced as a result of physiologic and pathologic conditions.

"For instance," he went on, "a certain albumin always produces a certain ferment. Presence in the blood stream of blood-foreign substances calls forth a ferment that will digest them and split them into molecules. The forces of nature form and mobilize directly in the blood serum.

"Let me get this clearly. Albumin cannot pass through the pores of an animal membrane, since the individual molecules are too large. If, however, the albumin is broken up by a ferment-action, then the molecules become small enough to pass through."

Seabury was listening like a man on whom a stunning blow was about to descend.

"Thus we can tell," proceeded Kennedy, "whether there is such a ferment in blood serum as would be produced by a certain condition, for when the ferment is there blood from the individual possessing it will digest a similar proteid in a dialyzing thimble kept at body temperature.

"Why," cried Kennedy, swept along by the wonder of the thing, "this test opens up a vista of alluring and extensive possibilities. The human organism actually diagnoses its own illnesses automatically. It is infinitely more exact, more rapid, and more certain than all that human art can attain. Each organ contains special ferments in its cells in the most subtle way attuned to the molecular condition of the particular cell substance and with complete indifference to other cells.