The Project Gutenberg EBook of Sigurd Our Golden Collie and Other Comrades of the Road, by Katharine Lee Bates This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sigurd Our Golden Collie and Other Comrades of the Road Author: Katharine Lee Bates Release Date: July 11, 2010 [EBook #33134] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE *** Produced by Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE

AND

OTHER COMRADES OF THE ROAD

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fairy Gold

The Retinue and Other Poems

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

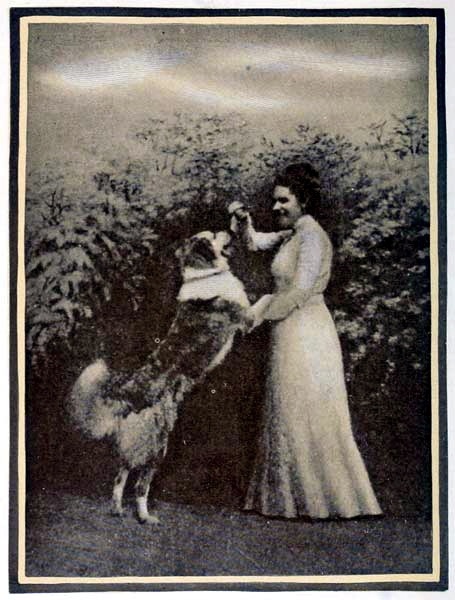

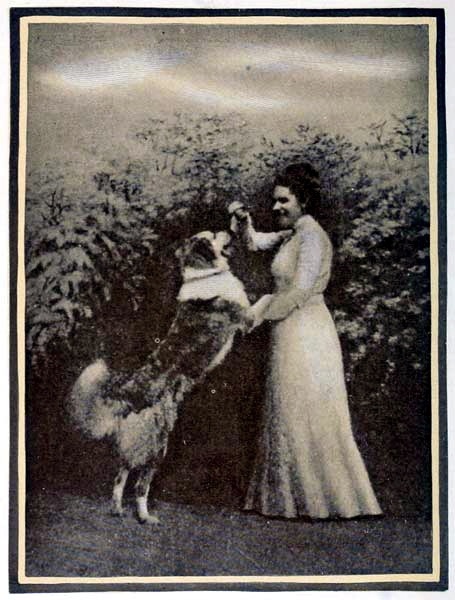

JOY OF LIFE AND SIGURD

SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE

AND

OTHER COMRADES of the ROAD

By

KATHARINE LEE BATES

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

Copyright, 1919,

By

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

First printing November, 1919

Second printing March, 1920

Printed in the United States of America

INSCRIBED

TO

THE ONE WHOM SIGURD LOVED BEST

A few of the sketches and poems in this volume have already appeared in print. Acknowledgments are due to The Christian Endeavor World, Life, The Outlook and Scribner's Magazine.

CONTENTS

I

SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE

| PAGE | |

| Vigi | 3 |

| Puppyhood | 5 |

| The Dogs of Bethlehem | 28 |

| Growing Up | 30 |

| Laddie | 55 |

| The Call of the Blood | 57 |

| Sigurd's Meditations in the Church Porch | 89 |

| Adventures | 90 |

| The Heart of a Dog | 120 |

| Home Studies | 121 |

| The Pleaders | 144 |

| College Career | 146 |

| To Sigurd | 174 |

| Farewells | 177 |

| To Joy-of-Life | 215 |

II

OTHER COMRADES OF THE ROAD

| The Pinegrove Path | 218 |

| Robin Hood | 219 |

| Why the Spire Fell | 246 |

| An Easter Chick | 248 |

| How Birds Were Made | 270 |

| Taka and Koma | 272 |

| Warbler Weather | 288 |

|

Summer Residents at a Wisconsin Lake.

By Katharine Coman |

290 |

| The Jester | 304 |

| Emilius | 305 |

| Hudson's Cat | 322 |

| Catastrophes | 324 |

| To Hamlet | 349 |

| Hamlet and Polonius | 350 |

SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE

AND

OTHER COMRADES OF THE ROAD

I

SIGURD OUR GOLDEN COLLIE

VIGI

Wisest of dogs was Vigi, a tawny-coated hound

That King Olaf, warring over green hills of Ireland, found;

His merry Norse were driving away a mighty herd

For feasts upon the dragonships, when an isleman dared a word:

"From all those stolen hundreds, well might ye spare my score."

"Ay, take them," quoth the gamesome king, "but not a heifer more.

Choose out thine own, nor hinder us; yet choose without a slip."

The isleman laughed and whistled, his finger at his lip.

Oh, swift the bright-eyed Vigi went darting through the herd

And singled out his master's neat with a nose that never erred,

And drave the star-marked twenty forth, to the wonder of the king,

Who bought the hound right honestly, at the price of a broad gold ring.

If the herddog dreamed of an Irish voice and of cattle on the hill,

He told it not to Olaf the King, whose will was Vigi's will,

But followed him far in faithful love and bravely helped him win

His famous fight with Thorir Hart and Raud, the wizard Finn.

Above the clamor and the clang shrill sounded Vigi's bark,

And when the groaning ship of Raud drew seaward to the dark,

And Thorir Hart leapt to the land, bidding his rowers live

Who could, Olaf and Vigi strained hard on the fugitive.

'Twas Vigi caught the runner's heel and stayed the windswift flight

Till Olaf's well-hurled spear had changed the day to endless night

For Thorir Hart, but not before his sword had stung the hound,

Whom the heroes bore on shield to ship, all grieving for his wound.

Now proud of heart was Vigi to be borne to ship on shield,

And many a day thereafter, when the bitter thrust was healed,

Would the dog leap up on the Vikings and coax with his Irish wit

Till 'mid laughter a shield was leveled, and Vigi rode on it.

PUPPYHOOD

"Only the envy was, that it lasted not still, or, now it is past, cannot by imagination, much less description, be recovered to a part of that spirit it had in the gliding by."

—Jonson's Masque of Hymen.

Sigurd was related to Vigi only by the line of Scandinavian literature. The Lady of Cedar Hill was enjoying the long summer daylights and marvelous rainbows of Norway, when word reached her that her livestock had been increased by the advent of ten puppies, and back there came for them all, by return mail, heroic names straight out of that splendid old saga of Burnt Njal.

But this is not the beginning of the story. Indeed, Sigurd's story probably emerges from a deeper distance than the story of mankind. Millions of glad creatures, his tawny ancestors, ranged the Highlands, slowly giving their wild hearts to the worship of man, and left no pedigree. The utmost of our knowledge only tells us that Sigurd's sire, the rough-coated collie Barwell Ralph (pronounced Rāfe), born September 3, 1894, was the son of Heather Ralph, a purple name with wind and ripples in it, himself the son of the sonorous Stracathro Ralph, whose parents were Christopher, a champion of far renown, and Stracathro Fancy; and of lovely Apple Blossom, offspring of Metchley Wonder and Grove Daisy. Ralph's mother of blessed memory was Aughton Bessie; her parents were Edgbarton Marvel, son of that same champion Christopher and Sweet Marie, and Wellesbourne Ada, in proudest Scotch descent from Douglas and Lady.

Sigurd's mother, Trapelo Dora, born May 16, 1900, was also a sable and white rough collie. Her sire, Barwell Masterpiece, son of Rightaway and Caermarther Lass, had for dashing grandsires Finsbury Pilot and Ringleader, and for gentle grandams, Miss Purdue and Jane. Her mother, Barwell Queenie, came of the great lineage of Southport Perfection and numbered among her ancestors a Beauty, a Princess and a Barwell Bess.

Those ten puppies, poor innocents, had something to live up to.

But their sire, Ralph, cared nothing for his distinguished progenitors, not even for that prize grandmother who had sold for eight hundred pounds, in comparison with the Lady of Cedar Hill, whom he frankly adored. His most blissful moments were those in which he was allowed to sit up on the lounge beside her, his paw in her palm, his head on her shoulder, his brown eyes rolling up to her face with a look of liquid ecstasy. He had been the guardian of Cedar Hill several years when Dora arrived. Shipped from those same Surrey kennels in which Ralph uttered his first squeal, her long journey over sea and land had been a fearsome experience. When the expressman dumped a travelworn box, labeled Live Dog, in the generous country house hall, and proceeded with some nervousness to knock off the slats, the assembled household grouped themselves behind the most reassuring pieces of furniture for protection against the outrush of a ferocious beast. But the delicate little collie that shot forth was herself in such terror that even the waiting dish of warm milk and bread, into which she splashed at once, could not allay her panic. From room to room she raced, hiding under sofas and behind screens, finding nothing that gave her peace, not even when she came up against a long mirror and fronted her own reflection, another scared little collie, which she tried to kiss with a puzzled tongue against the glass. Then in sauntered the lordly Ralph, whose indignant growl at the intruder died in his astonished throat as Dora confidingly flung herself upon him, leaping up and clinging to his well-groomed neck with grimy forelegs quivering for joy. Ralph was a dog who prided himself on his respectability. Affronted, shocked, he shook off this impudent young hussy, but homesick little Dora would not be repelled. Here, at last, was something she recognized, something that belonged to her lost world of the kennels. Let Ralph be as surly as he might, he had her perfect confidence from the outset, while the winsome Lady of Cedar Hill had to coax for days before Dora would make the first timid response to these strange overtures of human friendship.

As for Ralph, he decided to tolerate the nuisance and in course of time found her gypsy pranks amusing, even although she treated him with increasing levity. As he took his prolonged siesta, she would frisk about him, biting first one ear and then the other, till at last he would rise in magnificent menace and go chasing after her, his middle-aged dignity melting from him in the fun of the frolic, till his antics outcapered her own.

Dora's wits were brighter than his. If the Lady of Cedar Hill, after tossing a ball several times to the further end of the hall, for them to dash after in frantic emulation and bring back to her, only made a feint of throwing it, Ralph would hunt and hunt through the far corners of the room, while Dora, soon satisfying herself that the ball was not there, would dance back again and nose about the hands and pockets of her mistress, evidently concluding that the ball had not been thrown. Or if a door were closed upon them, Ralph would scratch long and furiously at its lower edge, while Dora, finding such efforts futile, would spring up and strike with her paw at the knob.

The date made momentous by the arrival of the ten puppies was August 20, 1902. The Lady of Cedar Hill, home from the Norland, found Dora full of the prettiest pride in her fuzzy babies, while Ralph, stalking about in jealous disgust, did his best to convey the impression that those troublesome absurdities were in no way related to him. This was not so easy, for they, one and all, were smitten with admiration of their august father and determination to follow in his steps. No sooner did Ralph, after casting one glare of contempt upon his family, stroll off nonchalantly toward the famous Maze, the Mecca of all the children in the neighboring factory town, than a line of eager puppies went waddling after. Glancing uneasily back, Ralph would give vent to a fierce paternal snarl, whereat squat on their stomachs would grovel the train, every puppy wriggling all over with delicious fright. But no sooner did Ralph proceed, with an attempt to resume his careless bachelor poise, than again he found those ten preposterous puppies panting along in a wavy procession at his very heels.

Only one of the puppies failed to thrive. Fragile little Kari, inappropriately named for one of the most terrible of the Vikings, died at the end of three months. But Helgi and Helga, Hauskuld and Hildigunna, Hrut, Unna and Flosi, Gunnar and Njal, waxed in size, activity and naughtiness until, in self-defense, the Lady of Cedar Hill began to give them away to her fortunate friends. Joy-of-Life was invited over to make an early choice. As Wellesley is not far from Cedar Hill, whose mistress she dearly loved, she went again and again, studying the youngsters with characteristic earnestness. They were nearly full-grown before she drove me over to confirm her election. The dogs were called up to meet us, and the lawn before the house looked to my bewildered gaze one white and golden blur of cavorting collies.

"Are they all here?" I asked, after vain efforts to count the heads in that whirl of perpetual motion.

"All but the barn dog," replied the Lady of Cedar Hill. "He is kept chained for the present, until he gets wonted to his humble sphere, but we will go down and call on him."

He saw us first. An excited bark made me aware of a young collie, almost erect in the barn door, tugging madly against his chain. The Lady of Cedar Hill, with a loving laugh, ran forward to release him. His gambol of gratitude nearly knocked her down, but before she had recovered her balance he was too far away for rebuke, romping, bounding, wheeling about the meadow, such a glorious image of wild grace and rapturous freedom that our hearts gladdened as we looked.

"But he is the most beautiful of all," I exclaimed.

"Oh, no," said the instructed Lady of Cedar Hill, "not from the blue-ribbon point of view." And she went on to explain that Njal, the biggest of the nine, was quite too big for a collie of such distinguished pedigree. His happy body, gleaming pure gold in the sun, with its snowy, tossing ruff, was both too tall and too long. His white-tipped tail was too luxuriantly splendid. The cock of his shining ears was not in the latest kennel style. His honest muzzle was a trifle blunt. He was, in short, lacking in various fine points of collie elegance, and so, while his dainty, aristocratic brothers and sisters were destined to be the ornaments of gentle homes, Njal was relegated to a life of service, in care of the cattle, and to that end had been for the month past kept in banishment at the barn.

But Njal had persistently rebelled against his destiny. He declined to explore the barn, always straining at the end of his chain in the doorway, watching with wistful eyes the frolics of his mother, hardly more than a puppy herself, with her overwhelming children. She seemed to have forgotten that Njal was one of her own. He would not make friends with the dairymen nor with the coachman, and though he showed an occasional interest in the horses, he utterly ignored the cows and calves whose guardian he was intended to be. Even now, in defiance of social distinctions, he dashed into the house, which, as we came hurrying up behind him, resounded with the reproachful voices of the maids.

"Njal, get out! You know you're not allowed in here."

"Njal, jump down off that bed this minute. The impudence of him!"

"Njal, drop that ball. It doesn't belong to you. Be off to the barn."

The maids, aided by Njal's brothers and sisters, who struck me as officious, had just succeeded in chasing him out as we came to the door, but he flashed past us, tail erect, enthusiastically bent on greeting his glorious sire, who was majestically pacing up to investigate this unseemly commotion.

"Poor Njal! Even more than the rest, he idolizes his father," said the Lady of Cedar Hill, as Ralph met his son with a growl and a cuff.

Crestfallen at last, Njal trotted back to his mistress and stood gazing up at her with great, amber eyes, that held, if ever eyes did, wounded love and a beseeching for comfort. She stroked his head, but bade one of the maids fetch a leash and take him back where he belonged.

I glanced at Joy-of-Life. That glance was all she had been waiting for.

"Njal is my dog," she said.

"What! Not Njal!" protested the Lady of Cedar Hill. "Why, in the count of collie points——"

"But I'm not looking for a dog to keep me supplied with blue ribbons. I want a friend. Njal has a soul."

The Lady of Cedar Hill bent a doubtful glance on me.

"Oh, we've just settled that," smiled Joy-of-Life. "She would rather have him than all the other eight."

So it was that on the last day of June, 1903, we drove again to Cedar Hill to bring our collie home.

"It's a queer choice," laughed our hostess, as she poured tea, "but at least you need not put yourselves out for him. He is used to the barn, and a box of straw in your cellar will be quite good enough for Njal."

She rang for more cream. No maid appeared. Surprised, she rang again, sharply. Still no response. One of the ever numerous guests rose and went out to the kitchen. She came back laughing.

"All the maids are kneeling around Njal, disputing as to whose ribbon becomes him best and worshiping him as if he were the golden calf. And really William has given an amazing shine to that yellow coat of his. It is astonishing what a splendid fellow the barn-puppy has grown to be."

In came Jane with the cream, blushing for her delay, but lingering to see what reception would be given the collie who walked politely a step or two behind.

Groomed till he shone, his new leather collar adorned with a flaring orange-satin bow, Njal entered with the quiet stateliness of one to drawing-rooms born, widely waving his tail in salutation to the entire company. But it was to the Lady of Cedar Hill that he went and against her side that he pressed close, while his questioning eyes passed from face to face, for he seemed already aware of an impending change in his fortunes.

The phaeton was brought to the door. Joy-of-Life and I took our places, and the Lady of Cedar Hill, who gave her puppies away right royally, passed in a new leash and complete box of brushes. Then the coachman lifted Njal, an armful of sprawling legs, and deposited him at our feet. The collie sat upright, making no effort to escape. But as his mistress perched on the carriage step to give him a good-bye hug, his eyes looked back into hers so wistfully, and yet so trustfully, that one of the maids in the background was heard to sniff.

"Be a good doggie," the beloved voice adjured him, "and don't give your new ladies any trouble on the long drive."

If he promised, he certainly kept his word. All the way he sat quietly where he had been put, erect and alert, watching the road and bestowing a very special regard on every dog and cat we passed. When we reached our modest home, he jumped out at our bidding, entered the open door and proceeded steadily from room to room, looking long out of each window as if hoping to find a familiar view. We had been warned that strange surroundings would probably affect his appetite, but Njal was far too sensible a collie to disdain a good dinner. He took to his puppy-biscuit and gravy with such a relish that, in an incredibly short period, the empty dish was dancing on the gravel under the hopeful insistence of his tongue. Homesickness, however, came on with the dusk. He gazed longingly from the piazza down the road, and when we attempted to introduce him to the cellar and his waiting box of plentiful clean straw, he resisted in a sudden agony of fright.

Njal had known nothing of cellars, and the terror with which that unnatural, lonesome hollow under ground affected him lasted for two full years. Then a visiting nephew, boy-wise in the ways of animals, romping with him, purposely scampered back and forth through the cellar, running in at one door and out at the other, so that the dog, in the ardor of the chase, had traversed that realm of awful chill and gloom before he realized where he was. Later on, one torrid afternoon, I carried a bone down cellar and, sitting on a log beside it, chanted its praises until, tempted beyond endurance, Njal came tumbling headlong downstairs and fell upon it. For a little while longer, he would not stay in the cellar without companionship, but at last his dread was so entirely overcome that, in the midsummer heats, the cellar, and especially, to our regret, the coal bin, was his favorite resort.

But on this first night he would have none of it. We were reluctant to use force and compromised on the bathroom. Here he obediently lay down and bore his lot in silence till dead of night, when at last the rising tide of desolation so overswelled his puppy heart that a sudden wail, which would have done credit to a banshee, woke everybody in the house.

The second evening he made his own arrangements. Our academic home was simple in its appointments,—so simple that Joy-of-Life and I often merrily quoted to each other the comment of a calling freshman:

"When I'm old, I mean to have a dear little house just like this one, all furnished with nothing but books."

The barn-dog inspected our chambers and promptly decided that only the best was good enough for him. This approved bower was then occupied by the Dryad, over whose couch was appropriately spread a velvety green cover, a foreign treasure of her own, marvelous for many-hued embroidery. As bedtime came on, Njal disappeared and was nowhere to be found, until the Dryad's pealing laugh brought us to her room, where a ball of golden collie, even the tail demurely tucked in, was sleeping desperately hard in the middle of the choice coverlet. One anxious eye blinked at us and then shut up tighter than ever. Njal was so determined not to be budged that the tender-hearted Dryad took his part and pleaded against our amateur efforts at discipline.

"Poor puppy! Let him be my room-mate tonight. He's so new and scared. He can sleep over there on the lounge under that farthest window and he will not bother me one bit."

Njal consented to this transfer, but in the small hours homesickness again swept his soul and he jumped up beside the Dryad, to whom he nestled close. The night was excessively hot, and the morning found a pallid lady snatching a belated nap on the lounge under the far window, while Njal remained in proud possession of the bed.

Joy-of-Life thereafter insisted on leashing him at night in the lower hall, where we would spread out for him the Thunder-and-Lightning Rug, an embarrassing gift for which we had never before been able to find a use. There he would contentedly take his post, the conscious guardian of the house, his white and yellow in vivid contrast to the black and scarlet of the rug, and his blue-figured Japanese bowl of water within easy reach. This disposition of our problem worked both well and ill, since Njal found distraction from his diminishing attacks of nostalgia in trying with his sharp white teeth the toughness of the leashes which succeeded one another in costly succession. But as a watch dog he took himself most seriously, though not greatly to the furtherance of our repose. From the depths of slumber he would leap up with a dynamic bark, accompanied by a bass growl, as if there were two of him, spinning around and around upon his leash, until we all rose from our beds, grasping electric torches, and sped downstairs to behold a fat beetle scuttling off across the floor or to hear the receding scamper of a mouse behind the wainscot. On the night before the Fourth, outraged by such a racket as he had never heard before, our ten-months-old protector succeeded in making more noise than all the horns, torpedoes and firecrackers in our patriotic neighborhood.

We celebrated the national holiday by changing his name, which sounded in the mouth of the mocker too much like miaul, to that of the shining hero of the Volsunga Saga. Joy-of-Life hesitated a little lest the Lady of Cedar Hill should deem her own Norse hero, Burnt Njal, "gentle and generous," treated with discourtesy, but I pleaded that in all likelihood our home would never again be blessed with anything so young and so yellow, so altogether fit to bear the honors of the Golden Sigurd. The collie readily accepted his new name, but never forgot the old, and even to the last year of his sunny life, if the word Njal were spoken, however softly, would glance up with bright recognition.

Sigurd bore himself through that first July with such civility and dignity that we did not dream how homesick he really was,—that towering puppy, who looked absurdly tall as we took him out to walk on his latest leash. He submitted to this needless indignity as he submitted to the long chain that bound him to the piazza railing, with magnanimous forbearance. We had used a rope at first, but he felt it a point of honor to gnaw this apart, coming cheerfully to meet us with a section of our clothesline trailing from his collar. Through these first weeks he had much to occupy his mind and tax his fortitude in the engine whistles and rumble of trains, the whirr of electric cars, Cecilia's energetic broom that threatened to brush him off the piazza, the manners of the market-man, who, unlearned in Norse mythology, injuriously called him Jigger, and divers other perils and excitements. His ears were forever on the cock and his tail busy with the agitated utterance of his changing emotions. When we ventured, after a little, to let him run loose, he investigated the immediate territory but kept within call, bounding to meet us as we came out to look for him. The first time that he actually ventured off on an independent quest, he came tearing back after forty minutes' absence as if he had been putting a girdle round the earth, insisting on a complete and repeated family welcome as well as a second breakfast. My first vivid sense of the comfort of having a dog smote me on the edge of a tired evening, when, trudging home from a long day in one of the Boston libraries, a sudden nose was thrust into my hand and a gleaming shape leapt up out of the roadside shadows in jubilant welcome. So we supposed our collie was light-hearted.

But one after-sunset hour, when we had feloniously sallied out to strip the flower-beds of an absent neighbor, Sigurd, in amiable attendance, suddenly started, wheeled and was off down the hill like a shimmering arrow of Apollo. How was he aware of her at that distance, in that dusk, the Lady of Cedar Hill? He flung himself like a happy avalanche upon her and poured out all the bewilderment and yearning, the lonesomeness and love of his loyal soul, in a shrill, ecstatic tremolo that we came to designate as "Sigurd's lyric cry." It was reserved for a favored few, objects of romantic devotion; it was rarely vouchsafed to the commonplace members of his own household; but it never failed the Lady of Cedar Hill, though months might elapse between her visits.

On this her first coming, his joy was touching to see. He pressed close to her side as she walked up the hill and after she had seated herself in a piazza chair he tried to climb into her lap as in his fuzzy puppyhood, and succeeded, too, though he hung over her knees like a yellow festoon, his feet touching the floor on either side and his plumy tail fanning her face. Yet when she went away, he made no effort to follow. He watched her intently from the piazza steps as she passed down the hill and turned the corner. When she was out of sight, tail and ears drooped and he came in of his own accord, soberly lying down on the Thunder-and-Lightning Rug, beside his leash. Feelings were all very well in their way, but duty was supreme. He had a house to guard from beetles and other bugbears of the night.

Sigurd was so big and strong that he needed plenty of exercise. Before he came, a spacious "run" had been provided for him on the wild bank, hardly yet redeemed from the forest, back of the house, but this he promptly repudiated for all purposes of frolic. He seemed to regard it as a singing-school, for, dragged out there "to play," he would sit on his haunches and practice dirge-music in howls of intolerable crescendo until a decent respect for the opinions of the neighbors obliged us to bring him in. We called him our gymnasium, walking and romping with him all we could, but our utmost was not enough. So we would drive out, once or twice a week, along the less frequented roads, though automobiles were not so many then, to give the boy a "scimper-scamper." He delighted to accompany the carriage, running alongside with brief dashes down the bank for water or into the woods after a squirrel. When he was tired, he would run close and look up, asking for a lift, but after a few minutes of panting repose, lying across the phaeton in front of our feet, nose and tail in alarming proximity to the wheels, he would want to scramble out and race again.

The first time that we took him back to Cedar Hill was a thrilling event for Sigurd. He had been running most of the way and jumped in just before we reached familiar landmarks. As soon as these appeared, all his weariness vanished. Standing erect, eyes shining, ears pricked up, nose quivering, his tail thumping the dashboard with louder and louder blows, he sent his lyric cry like a bugle through the air, heralding our approach so well that all his kindred yet remaining on the estate, as well as his original mistress, her guests and her maids, were drawn up on the lawn and steps to receive us. Sigurd sprang out before the horse had stopped and tore up with a special squeal of filial devotion to greet his sire, Ralph the Magnificent, who was barely restrained by a circle of strenuous hands on his collar from hurling himself in fury on this most obnoxious of his sons. Dora trotted up and sniffed at him with coquettish curiosity, as if wondering who this golden young gallant might be, but her bearing could by no stretch of language by styled maternal. Gunnar, a puppy with every mark of high descent, now installed on the estate as crown prince, was so infected by his father's rage that they both had to be shut up during our stay. Sigurd pranced rapturously all over the place, visiting every scene of his childhood with the conspicuous exception of the barn. He disdained to recognize the cows and gave but a supercilious curl of his tail even to the most affable of the dairymen. A cattle-dog, indeed! He invited himself to tea in the drawing-room and had the further impertinence to take a snooze on Dora's own cushion, close to the skirts of the Lady of Cedar Hill. She doubted whether he would be willing to go back with us, but when the phaeton was driven to the door, Sigurd rushed out to meet it and leapt into his place before we had finished our more ceremonious farewells. We knew then that he was really ours.

THE DOGS OF BETHLEHEM

Many a starry night had they known,

Melampo, Lupina and Cubilōn,

Shepherd-dogs, keeping

The flocks, unsleeping,

Serving their masters for crust and bone.

Many a starlight but never like this,

For star on star was a chrysalis

Whence there went soaring

A winged, adoring

Splendor out-pouring a carol of bliss.

Sniffing and bristling the gaunt dogs stood,

Till the seraphs, who smiled at their hardihood,

Calmed their panic

With talismanic

Touches like wind in the underwood.

In the dust of the road like gold-dust blown,

Melampo, Lupina and Cubilōn

Saw strange kings, faring

On camels, bearing

Treasures too bright for a mortal throne.

Shepherds three on their crooks a-leap

Sped after the kings up the rugged steep

To Bethlehem; only

The dogs, left lonely,

Stayed by the fold and guarded the sheep.

Faithful, grim hearts! The marvelous glow

Flooded e'en these with its overflow,

Wolfishness turning

Into a yearning

To worship the highest a dog may know.

When dawn brought the shepherds, each to his own,

Melampo, Lupina and Cubilōn

Bounded to meet them,

Frolicked to greet them,

Eager to serve them for love alone.

GROWING UP

"His years were full; his years were joyous; why

Must love be sorrow, when his gracious name

Recalls his lovely life of limb and eye?"

—Swinburne's At a Dog's Grave.

Now that we realized not only that we had adopted Sigurd but that Sigurd had adopted us, we entered into an ever deepening enjoyment of our dog. Be it understood that we were teachers, writers, servants of causes, boards, committees, mere professional women, with too little leisure for the home we loved. Had our hurried days given opportunity for the fine art of mothering we would have cherished a child instead of a collie, but Sigurd throve on neglect and saved us from turning into plaster images by making light of all our serious concerns. No academic dignities impressed his happy irreverence.

"What is Sigurd slinging about there on the lawn?" I asked on his first Commencement morning. "It looks as if he had a muskrat by the tail."

Joy-of-Life glanced apprehensively from the window to the bed, on which she had carefully laid out a dean's glistening regalia.

"My cap!" she ejaculated and dashed downstairs and out of the door and away over the grass after a frolicsome bandit who knew of no better use for a mortar-board—perhaps there is none—than to spin it around by its gilt tassel.

He had no regard for manuscript, after a thorough investigation had convinced him that it was not good to eat, and made no scruple of breaking in on our most absorbed moments with an insistent demand for play. Whatever the game might be, he infused it with dramatic quality, turning every romp into a thrilling adventure. He liked to pretend that he was Jack the Giant-Killer and would crouch and growl and bristle and finally hurl himself upon some ogre of a wastepaper basket, overthrowing it in the first onslaught and then worrying its scattered contents with mimic fury. For punishment, we would clap the basket tight over his head, and he would back into a corner, indulging in all sorts of profane remarks while he pawed and shook that insulting helmet off, but carefully, for he clearly understood that, though what it held was subject to his teeth, the basket itself must not be harmed. He pretended to be bitterly outraged by this treatment, but no sooner was the basket in position beside the desk again than he would caper up and gleefully knock it over, promptly presenting his ruffled head to have his punishment repeated.

Apart from our enjoyment of his crimes, it was difficult to punish him, because his sunny spirit turned every fresh experience into fun. He reminded me of a family tradition of an incorrigible baby uncle, whose clerical father, in despair at the child's ability to find amusement under all penal circumstances, stripped him naked and shut him into an empty room to repent of his sins. But when the parental eye condescended to the keyhole, it beheld a rosy cherub with puffed-out cheeks dancing merrily about and blowing a bewildered fly from one end of the chamber to the other.

Sigurd loved nothing better than make-believe discipline,—to be whacked with the feather-duster, "blown away" with the bellows, rolled up in the Sunday newspaper, anything that gave him an excuse for frisking, barking, dodging, scampering, kicking, rolling, tumbling, and rushing in at the last for a hug of assured understanding. We could keep him quiet for hours at a time by putting a cooky or any bit of sweet into a small pasteboard box, tying it up and fitting it into as many more, of increasing sizes, as time and material allowed. Sigurd would watch the process with sparkling eyes and then, taking the packet between his forepaws, settle down to the long task of getting at that cooky. Sometimes he would sigh with weariness or sink his yellow head to the floor in momentary despair. But he never gave up, though he often paused long enough to restore his energies by a nap. Taking the ragged bundle to another part of the room, as if his labors might be assisted by some special quality in a different rug, he would fall upon his puzzle again and not desist until the goal of all that patient endeavor, one morsel of sweetness, gave its brief delight to his triumphant tongue. This device of the boxes was a great resource when rough weather kept us in, for the youngster, who did not yet venture far without us, was incessant in his search for occupation. When this led him into genuine mischief and brought upon him actual rebuke, he took it so to heart that no member of the household, in kitchen or study, could get on with her work for the next half-day, for Sigurd would trot from one to another, with imploring eyes, insisting on shaking paws and being forgiven over and over again.

A most affectionate little fellow he was, and would sit still at my knee by the hour so long as he was occasionally patted and addressed by what he instantly recognized as a pet name,—Opals, or Blessed Buttercup, or Honey of Hybla, or Sulphur of my Soul. Epithets failing, he would touch my foot at intervals with a reminding paw. Then, absorbed in my work, I would absent-mindedly, on the edges of my consciousness, conjure up more titles for him,—Yellowboy, Crocus, Sunflower, Topaz, Mustard, Nugget, Starshine, his appreciative tail thumping the floor at every one. He wanted to be good and was aided by a happy disposition that, when one line of activity was cut off, found prompt solace in another. After a few trials had convinced him that bones, though polished in his most masterly manner and disposed behind doors and under sofa pillows with engaging modesty, were not acceptable ornaments of the house, he so rejoiced in the new-found art of burying them in the earth that, for a time, all his dainties went the same way, and the gardener's hoe would turn up petrified pieces of sponge cake and gingerbread at which Sigurd would sniff in embarrassed reminiscence.

Day by day the puppy was learning not only the ways of the house, but what he considered a proper demeanor toward our variety of callers. He took up the domestic routine almost at once and developed such an exact sense of time that we used to call him our four-o'clock. At this merry hour we would drop pens, shut books and take Sigurd to walk,—a duty that he by no means allowed us to forget. At the exact moment his Woof, Woof rang out like a bell into "the still air of delightful studies" and upon his protesting playmates Sigurd would burst like a thunderbolt, catching at our dresses and literally dragging us away from our desks. At mealtimes, too, with inexorable punctuality he herded the family to the dining room. But most of the day he was doing sentry duty on the doorsteps, incidentally offering his comment on every happening of the road and neighborhood. Tramps he abominated and, not content with driving them from our own premises, roared them away from every back door on the hill. His prejudice had to do, apparently, less with their looks and even their smell than with something stealthy and furtive in their approach. Skulking he abhorred. On one occasion he brought pink confusion to the cheeks of a little seamstress who was passing in a bundle at the door while her sheepish young escort hid in the shrubbery. It did not take Sigurd thirty seconds to drive that gawk from cover. To a recognized friend our collie would act as master of ceremonies, bounding down the walk to give him welcome, barking sharply to save him the trouble of ringing the bell, dashing in ahead with the glorious news of the arrival and then scampering back to thrust into the visitor's palm a cordial, clumsy paw, wagging that plumy tail meanwhile with an impetuous swing that sometimes swept before it small articles from cabinet or tea-table. Sometimes he would take a fancy to an utter stranger and greet him as an angel from the blue, singing love-at-first-sight to him at the top of his funny squeal, a four-legged troubadour. College girls he regarded as his natural chums and would frisk about them or leap upon them as the mood took him; middle-aged folk, like his mistresses, were all very well in their serviceable way; but the romance of life centered for Sigurd in old ladies. The whiter the hair, the more beautiful. For them he would spring up on his hind feet and rest his forepaws on their shoulders, pressing his face against their cheeks with such ardor that once, when such an encounter occurred on the street, a gentleman rushed from across the road, with upraised cane, to the rescue.

"Kindly let us alone, sir," crisply rebuked the Lovely Object, her bonnet askew but her face beaming. "This dog and I understand each other and we want no interference."

When a company of callers were seated, Sigurd, in a rapture of hospitality, would hurry again and again around the circle, shaking paws with each in turn and uttering a continuous, soft quaver of welcome, pleasure and pride. Then he would lie down contentedly in the very center of the group, now and then rolling over on his back in the hope that it would occur to somebody to slap his fluffy breast.

At first he often made mistakes in his office of sentinel. It was funny to see him rush madly to the door at a suspicious step and then, abashed by the jocular greeting of some household familiar, drop the rôle of heroic defender and, waving his tail affably but with a certain reserve, push by on the pretense that he was just coming out to take a squint at the weather.

Of sensitive and generous nature, our golden collie was quick to feel the difference between an intentional hurt and an accident. He had been with us only a few weeks when a college colleague, then brightening our table with her presence, started to play stick with him before dinner. Sigurd's way of playing stick was to bring you anything from a clothespin to a beanpole and coax you to throw it for him, holding it up lightly between his teeth for you to take. This time he had a piece of board with jagged ends, and our friend, whose own dog, a monstrously ugly and therefore supremely choice Boston Bull, would hang on to a stick with iron jaws while she tried in vain to wrench it from him, mistook the game. Sigurd held up his stick by one end, deftly balancing it in the air, and she, supposing that he would maintain his grip, rammed it suddenly down his throat. But Sigurd, eager for his run, at once let go, with the result that his throat was rather badly cut. He was surprised into one scream of pain and then silently tore about in circles, his tail low and rigid. His would-be playmate, grieved to the heart, had hurried for his Japanese water-bowl, but Sigurd would touch nothing that she brought. He went, instead, to a natural basin in the rock, always his favorite drinking-cup, where he lapped away at a prodigious rate, leaving a red stain on the water. After this he hid in the bushes, and it was not until dinner was nearly over that Sigurd came trotting in, ears and tail still depressed. Joy-of-Life, with the voice that was healing in itself, called him to her, but he passed us both by, going straight to the comparative stranger who had innocently hurt him. Settling on his haunches beside her chair, Sigurd gazed up mournfully but understandingly into her eyes and offered his magnanimous paw.

"You know I didn't mean to, and you came in to say so and to forgive me, you perfect little gentleman," she exclaimed, shaking the proffered paw as deferentially as if it had been the hand of Socrates. And that was the end of it. Sigurd coughed up a little blood and a few splinters that night, but he always met this lady, on her frequent comings, with a special, quiet courtesy, though he never invited her to a game of stick again.

Sigurd had one playmate who shamefully imposed upon his noble disposition. Nellie was an ancient spaniel, whose black curls were turning a dingy gray. She was our next neighbor and Sigurd's first love. Nellie was too fat and wheezy to romp, but she would sit, blinking approval, the center of a circle whose circumference was made by the golden gambols of our infatuated puppy. Around and around her he would caper, while she yawned and scratched—she was always a vulgar old thing—and took her exercise by proxy. We did not allow Nellie inside the house, to Sigurd's grieved surprise, but his dinner-dish was regularly set out of doors, by the back steps, and Nellie, every now and then, when her own rations had not been satisfactory or when Sigurd had peculiarly toothsome viands on his plate, would take advantage of his chivalry to play on him a low-down trick. Out of sight on the other side of the house, she would raise a wail of feigned distress, whereupon our gallant Volsung, just in the first enjoyment of his food, would lift his head, listen, even drop the piece of meat in his mouth and speed away to her rescue, running down one hill and up another in a vain endeavor to discover the villain of whom she had complained. Meanwhile Nellie, puffing with detestable delight, would waddle around to the doorsteps and gobble up the best of Sigurd's dinner. When she heard him bounding back, she discreetly shuffled off, so that Sigurd's ideal remained unspotted. Dear, faithful lad! To the last of her disgraceful days, he was old Nellie's champion and dupe.

All the while his development was going on apace. When he came to us he was already, like his brothers and sisters, proficient in giving the right paw, and could also, under protest, stand on his hind legs in a corner and "go roly-poly," a senseless performance, that he detested, on floors, but a natural and joyful gymnastic on the grass. He soon added to these accomplishments the agile arts of jumping over a stick and leaping through a hoop, though his tribulations with the hoop were many. He would brandish it over his head, run with it and trip in it, get his legs and body all wound up in it, and finally throw himself upon it and bite it into docility. He readily learned to catch, but his tastes were not extravagant and he would disdainfully drop in the thickets the rubber balls that were bought for him and grub up for himself some crooked branch or tough old chip that suited his purpose better.

Being educators ourselves, we did not think much of education as such and gave little attention to teaching him artificial tricks. Joy-of-Life was in favor of vocational training and decided that he must learn to guard. Her efforts nearly achieved success. For one proud fortnight Sigurd would, at the word of command, lie down and, resisting every temptation to leave his post, watch over a handkerchief or glove or parasol until he was called off by the same voice that had imposed the duty on him. It was I who ruined this excellent attainment by setting him, beside a pansy-bed agleam with sympathetic twinkles, to guard a hoptoad. To Sigurd's dismay and annoyance that brownie of the garden refused to play the game. How could a puppy remain at his post if his post would not remain at the puppy? Sigurd tried to paw the toad back into place, he remonstrated with it in a series of shrill barks and at last, when he heard us laughing at him, he indignantly repudiated, and forever, the whole business of guarding. It was then that Joy-of-Life accused me of being a demoralizing influence and for Sigurd's good reminded me of what I had quite forgotten and he had never known,—that he was not "our puppy" but hers.

"I want," said Joy-of-Life, bending her earnest look upon us both, "that Sigurd should grow up into a good dog, and how can he be a good dog if you turn duty into a joke?"

I felt so guilty that Sigurd hurried over to lick my hand.

"Whose dog are you, Gold of Ophir?" I asked, and Sigurd, with an impartial flourish of his tail, lay down exactly between us.

This delicate question was ultimately decided by no less an arbiter than Mother Goose. In pursuance of the theory that her immortal nonsense songs were written by Oliver Goldsmith—this is what is known as Literary Research—I had obtained leave from a Boston librarian, an indulgent spirit now gone to his reward, to take home for comparison with an accumulation of other texts a unique copy, exquisitely printed on creamy pages with wide margins and choicely bound in white and gold. It was an extraordinary grace of permission and, even in the act of passing that gem of a volume over, the librarian hesitated.

"It must not come to harm," he said, "for it is irreplaceable; but I know how you value books and I believe there are no children, to whom this might be a temptation, under your roof."

"Unfortunately, no; only a puppy."

"We will risk the puppy," he smiled,—but he did not know Sigurd.

I carried that book home as carefully as if it had been a nest of humming-bird's eggs. As I used it that evening at my desk, I propped it up at a far distance from any possible spatter of ink. Then I slipped it into a vacant space on the shelf of the revolving bookcase close at hand and, resolving to return it the next morning, turned to a good-night romp with the Volsung. We tried several new games without winning much popular applause. He was a failure as Wolf at the Door, because he barked so gleefully for admittance to the room where Joy-of-Life was brushing her mother's beautiful white hair and was so welcome when he came bursting in; nor did he shine as Mother Hubbard's dog, for his friend in the kitchen, Cecilia, who never let her cupboard go bare, had just filled the doughnut jar. So we practiced in secret for a few minutes on "a poetic recital" of Hickory Dickory Dock and then came forth to electrify the household. Taking a central seat, I repeated those talismanic syllables, at whose sound Sigurd jumped upon me, climbed up till his forepaws rested on the high top of the chair, in graphic illustration of the way the mouse ran up the clock, emitted an explosive bark when, shifting parts at a sudden pinch, he became for an instant the clock striking one, and then scrambled down with alacrity, a motion picture of the retreating mouse. This was no small intellectual exercise for a collie, and at the end of our one and only public performance he broke away and squeezed himself under the sofa, where he lay rubbing his poor, overwrought noddle against the coolest spot on the wall.

His mental energies had revived by morning and apparently he wanted to review his Hickory Dickory Dock, for he was in my study earlier than I and there, from all the rows of books on all the open shelves, he must needs pick out Mother Goose, even that unique copy de luxe. When I came in, there was Sigurd outstretched on his favorite rug, beside my desk, with the book between his forepaws, ecstatically engaged in chewing off one corner.

My gasp of horror brought Joy-of-Life speedily to the scene, and Sigurd, instantly aware that he had committed a transgression beyond precedent, slid unobtrusively away, his penitent tail tucked between his legs. We were too keenly concerned over the injury done to remember to punish him, but no further punishment than our obvious distress was needed. Never again would Sigurd touch a book or anything resembling a book. He had discovered, once for all, that he had no taste for literature.

"What can you do?" asked Joy-of-Life, distractedly trying to wipe that pulpy corner dry with her napkin. "This rich binding is ruined, but the margins are so broad that Sigurd—O Sigurd!—has not quite chewed through to the print."

"Nothing but make confession in sackcloth and ashes and pay what I have to pay," I answered gloomily. Then a wicked impulse prompted me to add:

"Of course, since it's your dog that has done the damage——"

"Sigurd is our dog," hastily interposed Joy-of-Life. "I give you half of him here and now, and we'll divide the damage."

So as I went in to inflict this shock upon the kind librarian I was not without a certain selfish consolation, for if I should have to pay over all my bank account, I would be getting my money's worth. The librarian bent his brows over that mangled volume, listened severely to my abject narration and not until his eye-glasses hopped off his nose did I realize that he was convulsed with laughter.

"What can I do?" I asked, too deeply contrite to resent his mirth.

He wiped his eyes, replaced his glasses, examined the book once more.

"Well!" he replied in a choking voice. "If it were possible to replace this volume, I should have to require you to do so at whatever cost. But there is no other copy to be had. Its æsthetic value is gone beyond repair. The text, fortunately, is intact. We shall have to cut the pages down to the print and bind them into plain covers. A pity, but it can't be helped. The circumstances do not seem to call for a fine, but the rebinding will cost you, I regret to say, twenty-five cents."

Choosing to deal generously with Joy-of-Life, I paid it all.

Although Sigurd's golden coat seemed but the outer shining of the gladness that possessed him, he had his share of the ills that flesh is heir to, the most serious being a well-nigh fatal attack of distemper. With human obtuseness, we did not realize at first that our collie was sick. We heard him making strangling sounds and thought he had swallowed too big a piece of bone. We started out, that Sunday afternoon, on a seven-mile walk, partly for the purpose of exercising Sigurd, and were a bit hurt by his most unwonted lack of enthusiasm. Instead of multiplying the miles by his usual process of racing in erratic circles around and around us and dashing off on far excursions over the fields on either side, he trotted soberly at heel, like the well-trained dog he never was. He moped, tail hanging, ears depressed, and soon began to fall behind. At the halfway turn he lay down and, for a time, flatly refused to budge. We laughed at his new game of Lazy Dog and relentlessly whistled him along. We were almost home, having passed through the village square, Sigurd lagging far in the rear, when a notorious bloodhound, out for his weekly constitutional, broke away from the steel chain by which his master was holding him and charged on our big puppy. Sigurd ran for his life, but the fleeter hound was close upon him. There were knots of men loafing about the square and, waiting for the next trolley car, there stood among them an old dame gayly attired in the colors of her native Erin. Sigurd's limited range of experience had led him to regard men either as secondary creatures who did what they were bid by the all-potent Lady of Cedar Hill or as parlor and piazza, ornaments enveloped in an unpleasant odor of tobacco. His peril called for strong protection, so, as we were still too distant, he took refuge behind the voluminous sea-green skirts of that decent Irish body and, dodging skillfully as she twirled and whirled, kept her as a buffer between himself and his enemy. Screeching to all the saints for deliverance, she was still striving in vain to escape from her awful position, when the owners of the dogs came panting up. The bloodhound's master collared him, none too soon, and beat him so savagely with the chain that we turned away from the sight to sympathize with Sigurd's involuntary defender and help her adjust her grass-green bonnet and veil. As for Sigurd, he had flashed out of the picture, but we found him at home, lying inert, exhausted, refusing water and biscuit, indifferent to bones. He sniffed regretfully at his Sunday dinner, but left it untasted.

An hour or two before dawn, simultaneously awakened by the sound of desperate coughing, Joy-of-Life and I met on the stairs and hurried down to find a croupy puppy, who, in his emergency, had again bitten his leash in two and climbed into his favorite—because forbidden—easy chair. As we leaned over him, Sigurd put up a paw to each of us, his suffering eyes expectant of relief. But we could devise no effectual help, and the veterinary, called in as early as we dared, regarded the invalid as a dangerous animal and handled him so roughly that, the moment Sigurd found himself released, he slipped out of the house and across the road to Nellie. Sorely disappointed in us, he tried to hide his yellow towering bulk on the other side of that grizzled little spaniel and waited, an exile from home, until the doctor had driven away.

For weeks we had a sick collie on our hands. He dreaded food and would squeeze himself into all impossible places when he saw either one of us coming with the prescribed "nourishment." As for medicine, he contracted that autumn an aversion to bottles which he never overcame. Years afterward, if Sigurd, about to enter a room, stopped short on the threshold and turned abruptly away, we looked around for the bottle.

One morning the gasps were very feeble. The veterinary told us the end was at hand. We took our earth-loving collie out from his dark hospital-nook in the house and laid him down among the asters and goldenrods on the wild land at the rear. The Lady of Cedar Hill had come over to see him once more. He was lying so still that we thought he would not move again, but at the sound of that beloved voice Sigurd stirred a feeble tail and breathed a ghostly echo of his lyric cry. Faint and hoarse though it was, there was the old glad recognition in it, and his first mistress, forgetting her intended precautions for the dogs at home, knelt down beside her Njal, comforting him with tender strokes and soft, caressing words. From that hour he began to mend, but so slowly that we were anxious about him all winter. Cruel pains would suddenly dart through him and he could never understand where they came from nor who did it. We would hear the sharp, distinctive cry that meant one of those pangs and then see Sigurd stagger up from his rug or cushion, look at it with deep reproach and cross to the furthest corner of the room. Once such a shoot of pain took him as he was standing by Joy-of-Life's gentle mother, his head propped on her knee, and the air of incredulous grief with which he drew back and gazed at her smote her to the soul. It was a matter of days before he could be coaxed to come to her again.

One of the discoveries of Sigurd's illness was the heart of our Swedish maid, Cecilia. Fresh from Ellis Island, buxom, comely, neat as a scoured rolling-pin, she regarded us with no more feeling than did her molding-board. We introduced her to the ways of an American household; we helped her with the speaking of English; we paid her wages; we were, in short, her Plymouth Rock, on which she stepped to her career in the New World. Best of all, we were palates and stomachs on which to try her sugary experiments, for it was her steadfast ambition to become an artist in dough with the view of securing a lucrative position as a pastry cook. However much we might further her own interests, her imperturbable coolness made it clear that as fellow-creatures we were nothing, but she humored every whim of that sick puppy, even letting him lie in her immaculate pantry when the restless fancy took him. Her love was lasting, too, for although, as soon as we had suffered her apprenticeship and begun to enjoy her perfected craft, she ruthlessly left us for "a hotel yob," she persisted for several years in sending Sigurd a dog-picture postcard every Christmas. We always gave him the cards, telling him they came from his friend Cecilia, and he pawed them politely, but inwardly deemed them a poor substitute for the cakes, tarts, puffs and crinkle-pastes of many curious flavors that had, for one brief season, made our At Homes famous in our "little academe," dropping delicious flakes for a thrifty tongue to garner under the table.

The distemper finally passed off in a trailing effect of St. Vitus' dance, which, again, our afflicted collie could not understand. On our springtide walks, his head, as he trotted in front, would suddenly be twitched to one side, as if we had jerked it by a rein. Apparently he thought we had, for invariably he came running back to see what we wanted of Sigurd.

The final, enduring result of this hard experience was an assured devotion. Sigurd had genially accepted us from the first as his people, but now, through the suffering and weakness, he had come to know us as his very own. The lyric cry still belonged to high romance, but after all those piteous weeks when he found his only comfort in lying close beside our feet—even, in extremity, upon them—he reserved certain welcomes and caresses for us alone. Ours was the long, silent pressure of the golden head against the knee and, in time of trouble, the swift touch of the tongue upon clouded faces, and ours the long, shining, intimate gaze that poured forth imperishable loyalty and love.

LADDIE

Lowly the soul that waits

At the white, celestial gates,

A threshold soul to greet

Belovèd feet.

Down the streets that are beams of sun

Cherubim children run;

They welcome it from the wall;

Their voices call.

But the Warder saith: "Nay, this

Is the City of Holy Bliss.

What claim canst thou make good

To angelhood?"

"Joy," answereth it from eyes

That are amber ecstasies,

Listening, alert, elate,

Before the gate.

Oh, how the frolic feet

On lonely memory beat!

What rapture in a run

'Twixt snow and sun!

"Nay, brother of the sod,

What part hast thou in God?

What spirit art thou of?"

It answers: "Love,"

Lifting its head, no less

Cajoling a caress,

Our winsome collie wraith,

Than in glad faith

The door will open wide,

Or kind voice bid: "Abide,

A threshold soul to greet

The longed-for feet."

Ah, Keeper of the Portal,

If Love be not immortal,

If Joy be not divine,

What prayer is mine?

THE CALL OF THE BLOOD

"Come, brother; away!"

—Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing.

Sigurd was not the only representative of his family in our favored town. His sister Hildigunna, who might well be described in the words applied to Hildigunna of the saga as "one of the fairest," was given to a comparatively remote household in Wellesley Hills from which—alas!—she soon was stolen and spirited away to fates unknown. But his brother Hrut, a name speedily changed by his new owners to Laddie, took up his happy abode at The Orchard, not half a mile from us. These owners, returning from one of their many holidays abroad, had found on shipboard the Lady of Cedar Hill, on her way back from Norway. Of course she told them about the ten puppies and of course she promised them one.

Reared in the best traditions of New England, these travelers had already achieved an ideal success as founders and directors of a famous school for girls and had retired from active labors to a tranquil home whose broad Colonial porches were screened with "white foam flowers" of the clematis. They were Neighbors par excellence, so beloved, so leaned upon, so beset with callers and "old girls," with church committees and town committees, with causes and confidences, that they literally had to go to Europe to secure an occasional rest. And it was charming to see how their modest dignity and winsome graciousness received due meed of honor the Old World over, from titled personages of London to the very cab-drivers of Florence, whom they believed to be "honorable men" and were undoubtedly cheated less for so believing. Hard, shrewd faces of Paris pensions and Swiss hotels softened in their presence, and even the severe old Scotch dame who rated them roundly for gadding about the globe instead of having married and reared a freckled family, like hers, was moved to add: "But I mak nae doobt ye are mooch respectet where ye cam fram." She would have been confirmed in this amiable concession if she could have seen how their return was a village jubilee and how all our accumulated joys and sorrows trooped in at once through their open doors. They were Ladies of rare and precious quality, with a touch of precise, old-fashioned elegance, which made one frank admirer exclaim: "But they are like finest china, like porcelain, like Sèvres. There is nothing so exquisite left on earth. They are classics." Most eminently of all, they were Sisters. A childhood of strange peril and suffering, in which their hearts clung so close together that they grew into one, had fitted naturally dissimilar natures into an utter harmony of desire and deed. Nobody ever thought of one without the other. Not Castor and Pollux shine with a more closely related and serener light.

The Sisters hardly waited for our first tumult of greetings to subside before, on a September afternoon as quietly radiant as their own faces, they drove over to Cedar Hill to see what they described as "ten little fluffy balls, only just large enough to wriggle." The choice of their collie they left to the giver. It was not determined then, but early in April they had a message setting the day on which they were to "come for Hrut." I presume they kissed the telephone. At all events, they went with glad alacrity. As the door opened to admit them, a beautiful little collie, pure white save for touches of a rich golden brown on the ears, on the fall of the tail and on the top of his nobly carried head, ran to meet them and sprang into the outstretched arms of the foremost, cuddling there as if he knew that he had found his Earthly Paradise.

His mistress had followed directly after him, aglow with pride in the grace of his welcome.

"But this one cannot be ours,—he is too lovely," exclaimed the Sister who was already clasping him tight.

"Yes," smiled the Lady of Cedar Hill, "this one is yours," and the puppy acquiesced with wagging tail and lapping tongue and every collie courtesy.

From the first a delicate little fellow, the long drive back made him ill, but he never gave, then or later, the least sign of homesickness, settling at once with aristocratic ease into the comforts and privileges of his new environment and lavishly returning love for love.

The Sisters, as well as the elder Cousin who dwelt with them, were "lovers of all things alive," from bishops and other dignitaries, who paid them appreciative homage, to the South Sea Islanders, of whose costumes they disapproved but to whom, from babyhood up, they had helped send missionaries. The grimiest urchin in town would grin confidentially as he touched his cap to them, and their sympathy overflowed all local limits to childhood everywhere. Little cripples were the special objects of their care and tenderness. Of birds and beasts they were spirited champions. No man dared whip his horse if they were in sight. One of the Sisters had a magic pen, and many of her stories, whimsical and wise, carried an appeal for human gratitude toward the domestic animals who spend their patient strength in human service, and for friendliness toward all these sensitive fellow-creatures, our brief companions on a whirling star. The quadrupeds must have passed on from one to another the glad tidings of these Ladies of Lovingkindness, for many a hungry and thirsty cur sought the hospitalities of their kitchen, and stray cats, forsaken by selfish owners on vacation, used their piazza and even their parlor as a summer hotel. Early one July morning I was starting out for the college grounds on the search for a wretched mongrel that, having appeared from nowhere in the spring term, as dogs will, had become a cheerful hobo of the campus, living sumptuously through unlimited attendance on the out-of-door luncheon parties of the village students. A Commencement auto had broken one of his legs and frightened him into hiding, and now the ebb of all that girl life which had fed and petted him and the disappearance of chance bones from the closed back doors of the dormitories had brought upon the college, I was informed by special delivery letter from an indignant alumna, "the disgrace of leaving one of God's creatures to suffer slow starvation." Old experience led me, before setting forth to the rescue, to telephone the Sisters and ask if they had any news of this divine vagabond.

"Yes, indeed," rang back a cheery voice. "He is breakfasting with us now on the porch. He came limping up the walk just as the bell rang, exactly as if he had been invited. Such a pleasant dog in his manners, though dreadfully thin and—it's not his fault, poor dear—so dirty! I have just been calling Dr. Vet. to come and see what can be done for that poor leg."

Of course Laddie was not their first dog. The checks of the school are still stamped with the head of Don, their black Newfoundland, who had a passion for attending the morning service in the school hall and nipping the heels of the kneeling girls. In the repeating of the Lord's Prayer he would join with a subdued rumble, doubtless acceptable to his Creator, but when shut out from the sacred exercises, he would howl under the windows an anthem of his own that offended both Heaven and earth.

In the inexorable process of the years, Don grew old, becoming a very Uncle Roly-Poly, but he was only loved the more. A cherished legend of the school relates how he was sleeping on his rug by the bed of one of his mistresses on a winter night, dreaming a saintly dream of chasing cats out of Paradise, when some real or fancied noise awoke him and, the faithful guardian of the school, he rushed through the low, open window and out upon the piazza roof, barking his thunderous warning to all trespassers. But he was still so bewildered with sleep that his legs ran faster than his mind and, before he knew it, he had pitched off the edge of that icy roof and was floundering in the snow beneath, the most astonished dog that ever bayed the moon. What happened to him then is supposed to have been related by Don himself:

"My howls dismayed the starry skies,

The Great and Little Dippers, O!

Till came an angel in disguise,

In dressing gown and slippers, O!

I staggered up the steepy stair;

She pushed me from behind, Bow wow!

She tended me with mickle care,

O winsome womankind! Bow wow!

She bathed my brow and bruisèd knee.

I only whined the louder, O!

She murmured: 'Homeopathy!

I'll give dear Don a powder,' O!

And may I be a pink-eyed rabbit

If she chose not from her stock, Bow wow!

FOR PERSONS OF A GOUTY HABIT

WHO'VE HAD A NERVOUS SHOCK. Bow wow!"

Other dogs had come after, notably Cardigan, a stately St. Bernard, who made the fatal mistake of biting a pacifist, but Laddie, the only real rival of Don in the Sisters' affections, was the crown of their delight in doghood.

Sigurd had been with us only a few days when we took him over to see his brother, already for nearly three months a resident at The Orchard. We found Laddie, slender, white and dainty, quite at home on the luxurious drawing-room sofa.

"I'm stronger than you," growled Sigurd, but Laddie, always the gentlest and sweetest tempered of collies, acquiesced so pleasantly that it was an amicable meeting. At the first hint of a second growl, Laddie gave up the place of honor to his guest.

Of course we remonstrated, admonished Sigurd and urged the accommodating host, whose good manners delighted the Sisters, to jump back, which he did, tucking himself unobtrusively into the further corner of the sofa. Sigurd immediately claimed that corner, which Laddie yielded to him with unruffled magnanimity, crossing over to the other. Sigurd promptly changed his mind again, pushing Laddie, this time a little inclined to demur, down to the floor. Unable to devise a plan by which he could curl into both corners at once, Sigurd stretched himself out at full length, doing his best to reach from end to end of the sofa, while Laddie, closely copying the attitude of this arrogant big brother, lay along the rug below. Scandalized by Sigurd's conduct, we would have removed him from his usurped throne in short order, but the Sisters, rejoicing in the perfection of Laddie's social graces and secretly convinced of their collie's moral superiority to ours, would not allow any interference with the visiting puppy's comfort.

That freedom of the sofa was precious to Sigurd's pride and by repeated efforts he tried to convince his obtuse mistresses that he was entitled to the same privilege at home. But Joy-of-Life, who did not believe in "pampering pets," stood firm. There was one evening, in particular, when Sigurd jumped up on our living-room lounge some score of times, keeping all the while a challenging eye on her, and just as many times was ignominiously tumbled off. When she finally took possession herself, laughing at his discomfiture, he banged his way out into the kitchen and went down with a thump on the bare floor, hoping that we would hear how hard it was and realize how sorely poor Sigurd was abused. Finding that no apologies were forthcoming, he bounded to the front door, barked his orders to have it opened and shot out into the dark. Within five minutes the familiar tinkle called us to the telephone and over the wire flowed the blithe voice of one of the Sisters.

"I must tell you what a lovely call we are having from dear Sigurd. He barked to come in only a minute ago and went right up to the sofa and took it all for himself—oh, yes, our Cousin had been sitting there with Laddie, but they didn't mind at all—and there he is now, making himself so charmingly at home, the beautiful boy. I do wish you could see him."

"We will," responded Joy-of-Life, and off we started to chastise Young Impudence, whom we had begun to suspect of being a trifle self-willed; but when we arrived the Sisters would by no means consent to his overthrow. So there, while the chat went on, Sigurd lolled and sprawled, yawning, stretching himself to an incredible length, rolling over on his back with paws held high as if to applaud his victory and continually turning up to Joy-of-Life eyes of such sparkling glee that her purposes of discipline melted in mirth.

None the less, she was a match for him, resorting to strategy when she was forbidden the exercise of force. Calling Laddie to her, she began to stroke his nestling head. Instantly Sigurd, with a multitudinous flourish of legs that might have moved a centipede to envy, flung himself off the sofa and roared imperiously at the front door:

"Open this, Somebody, and be quick about it, too. Time to be off. Oh, come along, Folks. You've no need to pat any dog but me. Good-night, Lovely Ladies. S'long, Lad. See you tomorrow in the gloaming."

And unless we kept a strict watch, so he would. How often, while surveying from our west porch, with Sigurd demurely sitting up between us, the last faint flushes of the sunset sky, from across the road there would be suddenly visible against the dusk a presence like a celestial apparition, so white and hushed it was, the shining figure, the lifted, listening head! And in the fraction of a second, even while we were catching at his collar, off would go Sigurd with a great leap, and away the brother collies would tear on a mighty run that kept two households anxious far into the night. There was nothing celestial about their behavior.

These lawless excursions often culminated in garbage-pail raids, debauches from which the young prodigals would sneak home, abashed with nausea. Once in a Commencement season we returned late in the evening, with a guest, from the high solemnity of the President's Reception, to find our hall strewn with Jonah strips of ham-rind and junks of pumpkin. Our guest was a brilliant, worldly being, a very dragon-fly of swiftness and gleam, and there she stood, exquisitely gowned in rose-red under lace whose color was that of moonlight seen through thin clouds, beholding our culprit, who an hour before had been exultantly ranging a world of mysterious and infinite adventure, flattened contritely in the midst of his enormities.

"How human!" was her only comment.

Often they came back injured, with bitten ears, scratched faces, bleeding feet, and pretended to be worse off than they were, so as to divert our reproaches into pity. Sigurd limped home one dawn with a cruelly torn claw and lay all day in a round clothes-basket, to which he had taken a fancy, curled up like a yellow caterpillar and sleeping like a dormouse. But when I was sitting on the piazza steps that evening, putting a fresh bandage on the claw, while Sigurd, almost too feeble to stir, watched the process with pathetic eyes, a blanched sprite glistened by, only a white motion through the dark, and in an instant the invalid had sped away, bandage trailing, to be wicked all over again.

No matter how often the four mistresses agreed that discipline required doors to be shut against the truants till daybreak, on these nights of their escapes ours were light slumbers that a pleading whine too easily broke and many were the tiptoe journeys down derisively creaking stairs to let the wanderers in. The next day such lame, dirty, subdued, meek-minded stay-at-homes as our collies were! It was hard to scold them properly when they rolled over on their backs and presented aching stomachs to be comforted. But sometimes these stampedes took place by day, for whenever they met out-of-doors these brothers, otherwise fairly obedient, would disregard all human commands for the authoritative call of the blood and dart away side by side like arrows shot from a single bow. The sins that neither would commit alone they reveled in without scruple when they were together. From all over town we heard of our paragons as chasing cats, jumping at horses' heads, over-running gardens and upsetting children. One sedate young woman on whom they leaped, entreating her to play with them, sent in a substantial bill to "the owner of the dog that tore my dress." When we inquired whether it was the golden collie or the white that did the damage she coldly replied that "the animals were so mixed up" she couldn't tell whether it was "the brown one or the drab,"—to such a condition had a bath of mud brought our dandies. One mother sternly confronted us with a weepy little boy who complained that "zem two dogs made me frow sticks for 'em all the way home from school an' my arm's most bwoke with tiredness."

I remember clearly one typical escapade. It had snowed for three successive days and nights. Joy-of-Life was away in Washington, reading a learned paper before some convention of economists. Her mother passed the shut-in hours patiently by the fireside, meditating with disapproval on Dante's Inferno which I was reading to her, at intervals, for cheer during her daughter's absence. Sigurd was spoiling for a romp. At last, in desperation, he amused himself by eating everything he came across,—a tube of paste, a roll of tissue paper, one of his own ribbons. I saw the latter end of the ribbon disappearing into his mouth and sprang to seize it, meaning to drag the rest out of his inner recesses, but Sigurd secured it by a furious gulp and capered away in triumph. At last the flakes had ceased falling, the snow plow had struggled through and, yielding to the big puppy's desperate urgency, I took him out to walk, following after the plow between glittering walls as high as my shoulder. At a turn in the road, I caught sight, across the level expanse, of the Younger Sister exercising an invisible Laddie. Suddenly there appeared above the parapet the tips of two golden-brown ears, pricked up in eager inquiry. Sigurd, overtopped by our own wall, could not have seen them, but with one tremendous lurch he was up and out, wallowing madly through the drifts to meet Laddie, who, like a miniature snow plow, was already breaking a way toward him. The collies touched noses and, ranging themselves side by side, plunged off into that blank of white, utterly deaf to the human calls that would check the onward impulse of their sacred brotherhood.