FRANCISCO PIZARRO.

FRANCISCO PIZARRO.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Spanish Pioneers, by Charles F. Lummis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Spanish Pioneers Author: Charles F. Lummis Release Date: July 6, 2010 [EBook #33095] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SPANISH PIONEERS *** Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

FRANCISCO PIZARRO.

FRANCISCO PIZARRO.

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1914

Copyright

By Charles F. Lummis

a.d. 1893

TO

ONE OF SUCH WOMEN AS MAKE HEROES AND

KEEP CHIVALRY ALIVE IN OUR LESS

SINGLE-HEARTED DAYS:

ELIZABETH BACON CUSTER

| a | the | sound of | ah | |

| e | " | " | ay | |

| i | " | " | ee | |

| j | " | " | h | |

| o | " | " | oh | |

| u | " | " | oo | |

| h | is | silent | ||

| ll | is | sounded like | lli | in million |

| ñ | " | " | ny | in lanyard |

| hua | " | " | wa | in water |

The views presented in this book have already taken their place in historical literature, but they are certainly altogether new ground for a popular work. Because it is new, some who have not fully followed the recent march of scientific investigation may fear that it is not authentic. I can only say that the estimates and statements embodied in this volume are strictly true, and that I hold myself ready to defend them from the standpoint of historical science.

I do this, not merely from the motive of personal regard toward the author, but especially in view of the merits of his work, its value for the youth of the present and of the coming generations.

AD. F. BANDELIER.

It is because I believe that every other young Saxon-American loves fair play and admires heroism as much as I do, that this book has been written. That we have not given justice to the Spanish Pioneers is simply because we have been misled. They made a record unparalleled; but our text-books have not recognized that fact, though they no longer dare dispute it. Now, thanks to the New School of American History, we are coming to the truth,—a truth which every manly American will be glad to know. In this country of free and brave men, race-prejudice, the most ignorant of all human ignorances, must die out. We must respect manhood more than nationality, and admire it for its own sake wherever found,—and it is found everywhere. The deeds that hold the world up are not of any one blood. We may be born anywhere,—that is a mere accident;[Pg 12] but to be heroes we must grow by means which are not accidents nor provincialisms, but the birthright and glory of humanity.

We love manhood; and the Spanish pioneering of the Americas was the largest and longest and most marvellous feat of manhood in all history. It was not possible for a Saxon boy to learn that truth in my boyhood; it is enormously difficult, if possible, now. The hopelessness of trying to get from any or all English text-books a just picture of the Spanish hero in the New World made me resolve that no other young American lover of heroism and justice shall need to grope so long in the dark as I had to; and for the following glimpses into the most interesting of stories he has to thank me less than that friend of us both, A. F. Bandelier, the master of the New School. Without the light shed on early America by the scholarship of this great pupil of the great Humboldt, my book could not have been written,—nor by me without his generous personal aid.

C. F. L.

I. The Broad Story.

CHAPTER PAGE

I. The Pioneer Nation 17

II. A Muddled Geography 25

III. Columbus the Finder 36

IV. Making Geography 43

V. The Chapter of Conquest 56

VI. A Girdle Round the World 71

VII. Spain in the United States 78

VIII. Two Continents Mastered 90

II. Specimen Pioneers.

I. The First American Traveller 101

II. The Greatest American Traveller 117

III. The War of the Rock 125

IV. The Storming of the Sky-City 135

V. The Soldier Poet 144

VI. The Pioneer Missionaries 149

VII. The Church-builders in New Mexico 158

VIII. Alvarado's Leap 170

[Pg 14]IX. The American Golden Fleece 181

III. The Greatest Conquest.

I. The Swineherd of Truxillo 203

II. The Man Who Would Not Give Up 215

III. Gaining Ground 225

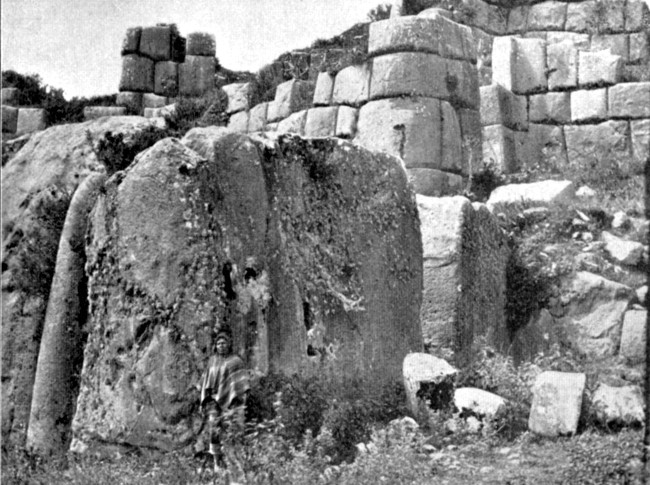

IV. Peru As It Was 238

V. The Conquest of Peru 246

VI. The Golden Ransom 257

VII. Atahualpa's Treachery and Death 265

VIII. Founding a Nation.—the Siege of Cuzco 275

IX. The Work of Traitors 284

It is now an established fact of history that the Norse rovers had found and made a few expeditions to North America long before Columbus. For the historian nowadays to look upon that Norse discovery as a myth, or less than a certainty, is to confess that he has never read the Sagas. The Norsemen came, and even camped in the New World, before the year 1000; but they only camped. They built no towns, and practically added to the world's knowledge nothing at all. They did nothing to entitle them to credit as pioneers. The honor of giving America to the world belongs to Spain,—the credit not only of discovery, but of centuries of such pioneering as no other nation ever paralleled in any land. It is a fascinating story, yet one to which our histories have so far done scant justice. History on true principles was an unknown science until within a century; and public opinion has long been hampered by the narrow statements and false conclusions[Pg 18] of closet students. Some of these men have been not only honest but most charming writers; but their very popularity has only helped to spread their errors wider. But their day is past, and the beginnings of new light have come. No student dares longer refer to Prescott or Irving, or any of the class of which they were the leaders, as authorities in history; they rank to-day as fascinating writers of romance, and nothing more. It yet remains for some one to make as popular the truths of American history as the fables have been, and it may be long before an unmistaken Prescott appears; but meantime I should like to help young Americans to a general grasp of the truths upon which coming histories will be based. This book is not a history; it is simply a guideboard to the true point of view, the broad idea,—starting from which, those who are interested may more safely go forward to the study of details, while those who can study no farther may at least have a general understanding of the most romantic and gallant chapter in the history of America.

We have not been taught how astonishing it was that one nation should have earned such an overwhelming share in the honor of giving us America; and yet when we look into the matter, it is a very startling thing. There was a great Old World, full of civilization: suddenly a New World was found,—the most important and surprising discovery in the whole annals of mankind. One would naturally suppose that the greatness of such a discovery would stir the intelligence of all the civilized nations about equally, and[Pg 19] that they would leap with common eagerness to avail themselves of the great meaning this discovery had for humanity. But as a matter of fact it was not so. Broadly speaking, all the enterprise of Europe was confined to one nation,—and that a nation by no means the richest or strongest. One nation practically had the glory of discovering and exploring America, of changing the whole world's ideas of geography, and making over knowledge and business all to herself for a century and a half. And Spain was that nation.

It was, indeed, a man of Genoa who gave us America; but he came as a Spaniard,—from Spain, on Spanish faith and Spanish money, in Spanish ships and with Spanish crews; and what he found he took possession of in the name of Spain. Think what a kingdom Ferdinand and Isabella had then besides their little garden in Europe,—an untrodden half world, in which a score of civilized nations dwell to-day, and upon whose stupendous area the newest and greatest of nations is but a patch! What a dizziness would have seized Columbus could he have foreseen the inconceivable plant whose unguessed seeds he held that bright October morning in 1492!

It was Spain, too, that sent out the accidental Florentine whom a German printer made godfather of a half world that we are barely sure he ever saw, and are fully sure he deserves no credit for. To name America after Amerigo Vespucci was such an ignorant injustice as seems ridiculous now; but, at all events, Spain sent him who gave his name to the New World.[Pg 20]

Columbus did little beyond finding America, which was indeed glory enough for one life. But of the gallant nation which made possible his discovery there were not lacking heroes to carry out the work which that discovery opened. It was a century before Anglo-Saxons seemed to waken enough to learn that there really was a New World, and into that century the flower of Spain crowded marvels of achievement. She was the only European nation that did not drowse. Her mailed explorers overran Mexico and Peru, grasped their incalculable riches, and made those kingdoms inalienable parts of Spain. Cortez had conquered and was colonizing a savage country a dozen times as large as England years before the first English-speaking expedition had ever seen the mere coast where it was to plant colonies in the New World; and Pizarro did a still greater work. Ponce de Leon had taken possession for Spain of what is now one of the States of our Union a generation before any of those regions were seen by Saxons. That first traveller in North America, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca, had walked his unparalleled way across the continent from Florida to the Gulf of California half a century before the first foot of our ancestors touched our soil. Jamestown, the first English settlement in America, was not founded until 1607, and by that time the Spanish were permanently established in Florida and New Mexico, and absolute masters of a vast territory to the south. They had already discovered, conquered, and partly colonized[Pg 21] inland America from northeastern Kansas to Buenos Ayres, and from ocean to ocean. Half of the United States, all Mexico, Yucatan, Central America, Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, Chile, New Granada, and a huge area besides, were Spanish by the time England had acquired a few acres on the nearest edge of America. Language could scarcely overstate the enormous precedence of Spain over all other nations in the pioneering of the New World. They were Spaniards who first saw and explored the greatest gulf in the world; Spaniards who discovered the two greatest rivers; Spaniards who found the greatest ocean; Spaniards who first knew that there were two continents of America; Spaniards who first went round the world! They were Spaniards who had carved their way into the far interior of our own land, as well as of all to the south, and founded their cities a thousand miles inland long before the first Anglo-Saxon came to the Atlantic seaboard. That early Spanish spirit of finding out was fairly superhuman. Why, a poor Spanish lieutenant with twenty soldiers pierced an unspeakable desert and looked down upon the greatest natural wonder of America or of the world—the Grand Cañon of the Colorado—three full centuries before any "American" eyes saw it! And so it was from Colorado to Cape Horn. Heroic, impetuous, imprudent Balboa had walked that awful walk across the Isthmus, and found the Pacific Ocean, and built on its shores the first ships that were ever made in the Americas, and sailed that unknown sea, and had[Pg 22] been dead more than half a century before Drake and Hawkins saw it.

England's lack of means, the demoralization following the Wars of the Roses, and religious dissensions were the chief causes of her torpidity then. When her sons came at last to the eastern verge of the New World they made a brave record; but they were never called upon to face such inconceivable hardships, such endless dangers as the Spaniards had faced. The wilderness they conquered was savage enough, truly, but fertile, well wooded, well watered, and full of game; while that which the Spaniards tamed was such a frightful desert as no human conquest ever overran before or since, and peopled by a host of savage tribes to some of whom the petty warriors of King Philip were no more to be compared than a fox to a panther. The Apaches and the Araucanians would perhaps have been no more than other Indians had they been transferred to Massachusetts; but in their own grim domains they were the deadliest savages that Europeans ever encountered. For a century of Indian wars in the east there were three centuries and a half in the southwest. In one Spanish colony (in Bolivia) as many were slain by the savages in one massacre as there were people in New York city when the war of the Revolution began! If the Indians in the east had wiped out twenty-two thousand settlers in one red slaughter, as did those at Sorata, it would have been well up in the eighteen-hundreds before the depleted colonies could have untied the[Pg 23] uncomfortable apron-strings of the mother country, and begun national housekeeping on their own account.

When you know that the greatest of English text-books has not even the name of the man who first sailed around the world (a Spaniard), nor of the man who discovered Brazil (a Spaniard), nor of him who discovered California (a Spaniard), nor of those Spaniards who first found and colonized in what is now the United States, and that it has a hundred other omissions as glaring, and a hundred histories as untrue as the omissions are inexcusable, you will understand that it is high time we should do better justice than did our fathers to a subject which should be of the first interest to all real Americans.

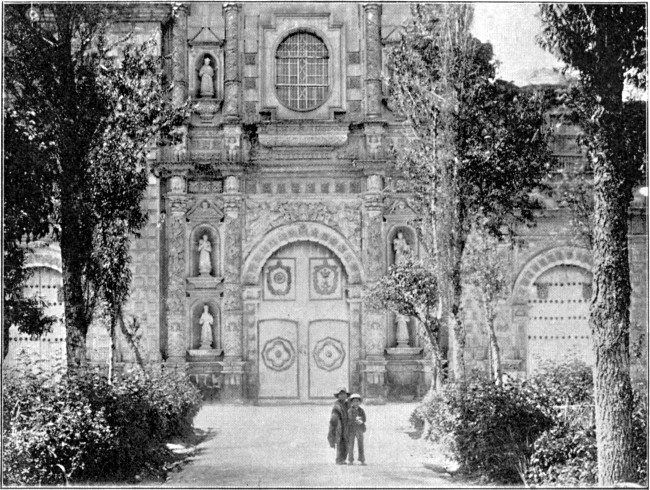

The Spanish were not only the first conquerors of the New World, and its first colonizers, but also its first civilizers. They built the first cities, opened the first churches, schools, and universities; brought the first printing-presses, made the first books; wrote the first dictionaries, histories, and geographies, and brought the first missionaries; and before New England had a real newspaper, Mexico had a seventeenth-century attempt at one!

One of the wonderful things about this Spanish pioneering—almost as remarkable as the pioneering itself—was the humane and progressive spirit which marked it from first to last. Histories of the sort long current speak of that hero-nation as cruel to the Indians; but, in truth, the record of Spain in[Pg 24] that respect puts us to the blush. The legislation of Spain in behalf of the Indians everywhere was incomparably more extensive, more comprehensive, more systematic, and more humane than that of Great Britain, the Colonies, and the present United States all combined. Those first teachers gave the Spanish language and Christian faith to a thousand aborigines, where we gave a new language and religion to one. There have been Spanish schools for Indians in America since 1524. By 1575—nearly a century before there was a printing-press in English America—many books in twelve different Indian languages had been printed in the city of Mexico, whereas in our history John Eliot's Indian Bible stands alone; and three Spanish universities in America were nearly rounding out their century when Harvard was founded. A surprisingly large proportion of the pioneers of America were college men; and intelligence went hand in hand with heroism in the early settlement of the New World.

The least of the difficulties which beset the finders of the New World was the then tremendous voyage to reach it. Had that three thousand miles of unknown sea been the chief obstacle, civilization would have overstepped it centuries before it did. It was human ignorance deeper than the Atlantic, and bigotry stormier than its waves, which walled the western horizon of Europe for so long. But for that, Columbus himself would have found America ten years sooner than he did; and for that matter, America would not have waited for Columbus's five-times-great-grandfather to be born. It was really a strange thing how the richest half of the world played so long at hide-and-seek with civilization; and how at last it was found, through the merest chance, by those who sought something entirely different. Had America waited to be discovered by some one seeking a new continent, it might be waiting yet.

Despite the fact that long before Columbus vagrant crews of half a dozen different races had already reached the New World, they had left[Pg 26] neither mark on America nor result in civilization; and Europe, at the very brink of the greatest discovery and the greatest events in history, never dreamed of it. Columbus himself had no imaginings of America. Do you know what he started westward to find? Asia.

The investigations of recent years have greatly changed our estimates of Columbus. The tendency of a generation ago was to transform him to a demigod,—an historical figure, faultless, rounded, all noble. That was absurd; for Columbus was only a man, and all men, however great, fall short of perfection. The tendency of the present generation is to go to the other extreme,—to rob him of every heroic quality, and make him out an unhanged pirate and a contemptible accident of fortune; so that we are in a fair way to have very little Columbus left. But this is equally unjust and unscientific. Columbus in his own field was a great man despite his failings, and far from a contemptible one.

To understand him, we must first have some general understanding of the age in which he lived. To measure how much of an inventor of the great idea he was, we must find out what the world's ideas then were, and how much they helped or hindered him.

In those far days geography was a very curious affair indeed. A map of the world then was something which very few of us would be able to identify at all; for all the wise men of all the earth knew less of the world's topography than an eight-year old[Pg 27] schoolboy knows to-day. It had been decided at last that the world was not flat, but round,—though even that fundamental knowledge was not yet old; but as to what composed half the globe, no man alive knew. Westward from Europe stretched the "Sea of Darkness," and beyond a little way none knew what it was or contained. The variation of the compass was not yet understood. Everything was largely guess-work, and groping in the dark. The unsafe little "ships" of the day dared not venture out of sight of land, for there was nothing reliable to guide them back; and you will laugh at one reason why they were afraid to sail out into the broad western sea,—they feared that they might unknowingly get over the edge, and that ship and crew might fall off into space! Though they knew the world was roundish, the attraction of gravitation was not yet dreamed of; and it was supposed that if one got too far over the upper side of the ball one would drop off!

Still, it was a matter of general belief that there was land in that unknown sea. That idea had been growing for more than a thousand years,—for by the second century it began to be felt that there were islands beyond Europe. By Columbus's time the map-makers generally put on their rude charts a great many guess-work islands in the Sea of Darkness. Beyond this swarm of islands was supposed to lie the east coast of Asia,—and at no enormous distance, for the real size of the world was underestimated by one third. Geography was in its mere[Pg 28] infancy; but it was engaging the attention and study of very many scholars who were learned for their day. Each of them put his studious guessing into maps, which varied astonishingly from one another.

But one thing was accepted: there was land somewhere to the west,—some said a few islands, some said thousands of islands, but all said land of some sort. So Columbus did not invent the idea; it had been agreed upon long before he was born. The question was not if there was a New World, but if it was possible or practicable to reach it without sailing over the jumping-off place or encountering other as sad dangers. The world said No; Columbus said Yes,—and that was his claim to greatness. He was not an inventor, but an accomplisher; and even what he accomplished physically was less remarkable than his faith. He did not have to teach Europe that there was a new country, but to believe that he could get to that country; and his faith in himself and his stubborn courage in making others believe in him was the greatness of his character. It took less of a man to make the final proof than to convince the public that it was not utter foolhardiness to attempt the proof at all.

Christopher Columbus, as we call him (as Colon[1] he was better known in his own day), was born in Genoa, Italy, the son of Dominico Colombo, a wool-comber, and Suzanna Fontanarossa. The year of his birth is not certain; but it was probably about[Pg 29] 1446. Of his boyhood we know nothing, and little enough of all his early life,—though it is certain that he was active, adventurous, and yet very studious. It is said that his father sent him for awhile to the University of Pavia; but his college course could not have lasted very long. Columbus himself tells us that he went to sea at fourteen years of age. But as a sailor he was able to continue the studies which interested him most,—geography and kindred topics. The details of his early seafaring are very meagre; but it seems certain that he sailed to England, Iceland, Guinea, and Greece,—which made a man then far more of a traveller than does a voyage round the world nowadays; and with this broadening knowledge of men and lands he was gaining such grasp of navigation, astronomy, and geography as was then to be had.

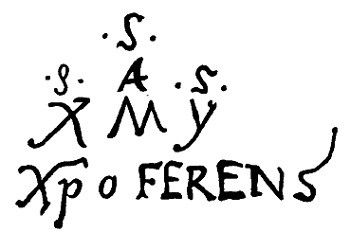

Autograph of Christopher Columbus.

Autograph of Christopher Columbus.

It is interesting to speculate how and when Columbus first conceived an idea of such stupendous importance. It was doubtless not until he was a mature and experienced man, who had become not only a skilled sailor, but one familiar with what other sailors had done. The Madeiras and the Azores had been discovered more than a century. Prince Henry, the Navigator (that great patron of early exploration), was sending his crews down the west coast of[Pg 30] Africa,—for at that time it was not even known what the lower half of Africa was. These expeditions were a great help to Columbus as well as to the world's knowledge. It is almost certain, too, that when he was in Iceland he must have heard something of the legends of the Norse rovers who had been to America. Everywhere he went his alert mind caught some new encouragement, direct or indirect, to the great resolve which was half unconsciously forming in his mind.

About 1473 Columbus wandered to Portugal; and there formed associations which had an influence on his future. In time he found a wife, Felipa Moñiz, the mother of his son and chronicler Diego. As to his married life there is much uncertainty, and whether it was creditable to him or the reverse. It is known from his own letters that he had other children than Diego, but they are left in obscurity. His wife is understood to have been a daughter of the sea-captain known as "The Navigator," whose services were rewarded by making him the first governor of the newly discovered island of Porto Santo, off Madeira. It was the most natural thing in the world that Columbus should presently pay a visit to his adventurous father-in-law; and it was, perhaps, while in Porto Santo on this visit that he began to put his great thoughts in more tangible shape.

With men like "the world-seeking Genoese," a resolve like that, once formed, is as a barbed arrow,—difficult to be plucked out. From that day on he[Pg 31] knew no rest. The central idea of his life was "Westward! Asia!" and he began to work for its realization. It is asserted that with a patriotic intention he hastened home to make first offer of his services to his native land. But Genoa was not looking for new worlds, and declined his proffer. Then he laid his plans before John II. of Portugal. King John was charmed with the idea; but a council of his wisest men assured him that the plan was ridiculously foolhardy. At last he sent out a secret expedition, which after sailing out of sight of shore soon lost heart and returned without result. When Columbus learned of this treachery, he was so indignant that he left for Spain at once, and there interested several noblemen and finally the Crown itself in his audacious hopes. But after three years of profound deliberation, a junta[2] of astronomers and geographers decided that his plan was absurd and impossible,—the islands could not be reached. Disheartened, Columbus started for France; but by a lucky chance tarried at an Andalusian monastery, where he won the guardian, Juan Perez de Marchena, to his views. This monk had been confessor to the queen; and through his urgent intercession the Crown at last sent for Columbus, who returned to court. His plans had grown within him till they almost overbalanced him, and he seems to have forgotten that his discoveries were only a hope and not yet a fact. Courage and persistence he certainly had; but we could wish that now he had[Pg 32] been a trifle more modest. When the king asked on what terms he would make the voyage, he replied: "That you make me an admiral before I start; that I be viceroy of all the lands that I shall find; and that I receive one tenth of all the gain." Strong demands, truly, for the poor wool-comber's son of Genoa to speak to the dazzling king of Spain!

Ferdinand promptly rejected this bold demand; and in January, 1492, Columbus was actually on his way to France to try to make an impression there, when he was overtaken by a messenger who brought him back to court. It is a very large debt that we owe to good Queen Isabella, for it was due to her strong personal interest that Columbus had a chance to find the New World. When all science frowned, and wealth withheld its aid, it was a woman's persistent faith—aided by the Church—that saved history.

There has been a great deal of equally unscientific writing done for and against that great queen. Some have tried to make her out a spotless saint,—a rather hopeless task to attempt in behalf of any human being,—and others picture her as sordid, mercenary, and in no wise admirable. Both extremes are equally illogical and untrue, but the latter is the more unjust. The truth is that all characters have more than one side; and there are in history as in everyday life comparatively few figures we can either deify or wholly condemn. Isabella was not an angel,—she was a woman, and with failings, as every woman has. But she was a remarkable woman and a great one, and worthy our respect as well as[Pg 33] our gratitude. She has no need to fear comparison of character with "Good Queen Bess," and she made a much greater mark on history. It was not sordid ambition nor avarice which made her give ear to the world-finder. It was the woman's faith and sympathy and intuition which have so many times changed history, and given room for the exploits of so many heroes who would have died unheard of if they had depended upon the slower and colder and more selfish sympathy of men.

Isabella took the lead and the responsibility herself. She had a kingdom of her own; and if her royal husband Ferdinand did not deem it wise to embark the fortunes of Arragon in such a wild enterprise, she could meet the expenses from her realm of Castile. Ferdinand seems to have cared little either way; but his fair-haired, blue-eyed queen, whose gentle face hid great courage and determination, was enthusiastic.

The Genoan's conditions were granted; and on the 17th of April, 1492, one of the most important papers that ever held ink was signed by their Majesties, and by Columbus. If you could see that precious contract, you would probably have very little idea whose autograph was the lower one,—for Columbus's rigmarole of a signature would cause consternation at a teller's window nowadays. The gist of this famous agreement was as follows:—

1. That Columbus and his heirs forever should have the office of admiral in all the lands he might discover.[Pg 34]

2. That he should be viceroy and governor-general of these lands, with a voice in the appointment of his subordinate governors.

3. That he should reserve for himself one tenth part of the gold, silver, pearls, and all other treasures acquired.

4. That he and his lieutenant should be sole judges, concurrent with the High Admiral of Castile, in matters of commerce in the New World.

5. That he should have the privilege of contributing one eighth to the expenses of any other expedition to these new lands, and should then be entitled to one eighth of the profits.

It is a pity that the conduct of Columbus in Spain was not free from a duplicity which did him little credit. He entered the service of Spain, Jan. 20, 1486. As early as May 5, 1487, the Spanish Crown gave him three thousand maravedis (about $18) "for some secret service for their Majesties;" and during the same year, eight thousand maravedis more. Yet after this he was secretly proffering his services again to the King of Portugal, who in 1488 wrote Columbus a letter giving him the freedom of the kingdom in return for the explorations he was to make for Portugal. But this fell through.

Of the voyage itself you are more likely to have heard,—the voyage which lasted a few months, but to earn which the strong-hearted Genoese had borne nearly twenty years of disheartenment and opposition. It was the years of undaunted struggling to convert the world to his own unfathomed wisdom[Pg 35] that showed the character of Columbus more fully than all he ever did after the world believed him.

The difficulties of securing official consent and permission being thus at last overcome, there was only the obstacle left of getting an expedition together. This was a very serious matter; there were few who cared to join in such a foolhardy undertaking as it was felt to be. Finally, volunteers failing, a crew had to be gathered forcibly by order of the Crown; and with his não the "Santa Maria," and his two caravels the "Niña" and the "Pinta," filled with unwilling men, the world-finder was at last ready.

Columbus sailed from Palos, Spain, on Friday, August 3, 1492, at 8 a. m., with one hundred and twenty Spaniards under his command. You know how he and his brave comrade Pinzon held up the spirits of his weakening crew; and how, on the morning of October 12, they sighted land at last. It was not the mainland of America,—which Columbus never saw until nearly eight years later,—but Watling's Island. The voyage had been the longest west which man had yet made; and it was very characteristically illustrative of the state of the world's knowledge then. When the variations of the magnetic needle were noticed by the voyagers, they decided that it was not the needle but the north star that varied. Columbus was perhaps as well informed as any other geographer of his day; but he came to the sober conclusion that the cause of certain phenomena must be that he was sailing over a bump on the globe! This was more strongly brought out in his subsequent voyage to the Orinoco, when he detected even a worse earth-bump, and concluded that the world must be pear-shaped! It is interesting to remember that but for an accidental[Pg 37] change of course, the voyagers would have struck the Gulf Stream and been carried north,—in which case what is now the United States would have become the first field of Spain's conquest.

The first white man who saw land in the New World was a common sailor named Rodrigo de Triana, though Columbus himself had seen a light the night before. Although it is probable—as you will see later on—that Cabot saw the actual continent of America before Columbus (in 1497), it was Columbus who found the New World, who took possession of it as its ruler under Spain, and who even founded the first European colonies in it,—building, and settling with forty-three men, a town which he named La Navidad (the Nativity), on the island of San Domingo (Española, as he called it), in December, 1492. Moreover, had it not been that Columbus had already found the New World, Cabot never would have sailed.

The explorers cruised from island to island, finding many remarkable things. In Cuba, which they reached October 26, they discovered tobacco, which had never been known to civilization before, and the equally unknown sweet potato. These two products, of the value of which no early explorer dreamed, were to be far more important factors in the money-markets and in the comforts of the world than all the more dazzling treasures. Even the hammock and its name were given to civilization by this first voyage.

In March, 1493, after a fearful return voyage,[Pg 38] Columbus was again in Spain, telling his wondrous news to Ferdinand and Isabella, and showing them his trophies of gold, cotton, brilliant-feathered birds, strange plants and animals, and still stranger men,—for he had also brought back with him nine Indians, the first Americans to take a European trip. Every honor was heaped upon Columbus by the appreciative country of his adoption. It must have been a gallant sight to see this tall, athletic, ruddy-faced though gray-haired new grandee of Spain riding in almost royal splendor at the king's bridle, before an admiring court.

The grave and graceful queen was greatly interested in the discoveries made, and enthusiastic in preparing for more. Both intellectually and as a woman, the New World appealed to her very strongly; and as to the aborigines, she became absorbed in earnest plans for their welfare. Now that Columbus had proved that one could sail up and down the globe without falling over that "jumping-off place," there was no trouble about finding plenty of imitators.[3] He had done his work of genius,—he was the pathfinder,—and had finished his great mission. Had he stopped there, he would have left a much greater name; for in all that came after he was less fitted for his task.

A second expedition was hastened; and Sept. 25, 1493, Columbus sailed again,—this time taking fifteen hundred Spaniards in seventeen vessels, with[Pg 39] animals and supplies to colonize his New World. And now, too, with strict commands from the Crown to Christianize the Indians, and always to treat them well, Columbus brought the first missionaries to America,—twelve of them. The wonderful mother-care of Spain for the souls and bodies of the savages who so long disputed her entrance to the New World began early, and it never flagged. No other nation ever evolved or carried out so noble an "Indian policy" as Spain has maintained over her western possessions for four centuries.

The second voyage was a very hard one. Some of the vessels were worthless and leaky, and the crews had to keep bailing them out.

Columbus made his second landing in the New World Nov. 3, 1493, on the island of Dominica. His colony of La Navidad had been destroyed; and in December he founded the new city of Isabella. In January, 1494, he founded there the first church in the New World. During the same voyage he also built the first road.

As has been said, the first voyages to America were little in comparison with the difficulty in getting a chance to make a voyage at all; and the hardships of the sea were nothing to those that came after the safe landing. It was now that Columbus entered upon the troubles which darkened the remainder of a life of glory. Great as was his genius as an explorer, he was an unsuccessful colonizer; and though he founded the first four towns in all the New World, they brought him only ill. His colonists[Pg 40] at Isabella soon grew mutinous; and San Tonias, which he founded in Hayti, brought him no better fortune. The hardships of continued exploration among the West Indies presently overcame his health, and for nearly half a year he lay sick in Isabella. Had it not been for his bold and skilful brother Bartholomew, of whom we hear so little, we might not have heard so much of Columbus.

By 1495, the just displeasure of the Crown with the unfitness of the first viceroy of the New World caused Juan Aguado to be sent out with an open commission to inspect matters. This was more than Columbus could bear; and leaving Bartholomew as adelantado (a rank for which we now have no equivalent; it means the officer in chief command of an expedition of discoverers), Columbus hastened to Spain and set himself right with his sovereigns. Returning to the New World as soon as possible, he discovered at last the mainland (that of South America), Aug. 1, 1498, but at first thought it an island, and named it Zeta. Presently, however, he came to the mouth of the Orinoco, whose mighty current proved to him that it poured from a continent.

Stricken down by sickness, he returned to Isabella, only to find that his colonists had revolted against Bartholomew. Columbus satisfied the mutineers by sending them back to Spain with a number of slaves,—a disgraceful act, for which the times are his only apology. Good Queen Isabella was so indignant at this barbarity that she ordered the poor Indians to be[Pg 41] liberated, and sent out Francisco de Bobadilla, who in 1500 arrested Columbus and his two brothers, in Española, and sent them in irons to Spain. Columbus speedily regained the sympathy of the Crown, and Bobadilla was superseded; but that was the end of Columbus as viceroy of the New World. In 1502 he made his fourth voyage, discovered Martinique and other islands, and founded his fourth colony,—Bethlehem, 1503. But misfortune was closing in upon him. After more than a year of great hardship and distress, he returned to Spain; and there he died May 20, 1506.

The body of the world-finder was buried in Valladolid, Spain, but was several times transferred to new resting-places. It is claimed that his dust now lies, with that of his son Diego, in a chapel of the cathedral of Havana; but this is doubtful. We are not at all sure that the precious relics were not retained and interred on the island of Santo Domingo, whither they certainly were brought from Spain. At all events, they are in the New World,—at peace at last in the lap of the America he gave us.

Columbus was neither a perfect man nor a scoundrel,—though as each he has been alternately pictured. He was a remarkable man, and for his day and calling a good one. He had with the faith of genius a marvellous energy and tenacity, and through a great stubbornness carried out an idea which seems to us very natural, but to the world then seemed ridiculous. As long as he remained in the profession[Pg 42] to which he had been reared, and in which he was probably unequalled at the time, he made a wonderful record. But when, after half a century as a sailor, he suddenly turned viceroy, he became the proverbial "sailor on land,"—absolutely "lost." In his new duties he was unpractical, headstrong, and even injurious to the colonization of the New World. It has been a fashion to accuse the Spanish Crown of base ingratitude toward Columbus; but this is unjust. The fault was with his own acts, which made harsh measures by the Crown necessary and right. He was not a good manager, nor had he the high moral principle without which no ruler can earn honor. His failures were not from rascality but from some weaknesses, and from a general unfitness for the new duties to which he was too old to adapt himself.

We have many pictures of Columbus, but probably none that look like him. There was no photography in his day, and we cannot learn that his portrait was ever drawn from life. The pictures that have come down to us were made, with one exception, after his death, and all from memory or from descriptions of him. He is represented to have been tall and imposing, with a rather stern face, gray eyes, aquiline nose, ruddy but freckled cheeks, and gray hair, and he liked to wear the gray habit of a Franciscan missionary. Several of his original letters remain to us, with his remarkable autograph, and a sketch that is attributed to him.

[3] As he himself complains: "The very tailors turned explorers."

While Columbus was sailing back and forth between the Old World and the new one which he had found, was building towns and naming what were to be nations, England seemed almost ready to take a hand. All Europe was interested in the strange news which came from Spain. England moved through the instrumentality of a Venetian, whom we know as Sebastian Cabot. On the 5th of March, 1496,—four years after Columbus's discovery,—Henry VII. of England granted a patent to "John Gabote, a citizen of Venice," and his three sons, allowing them to sail westward on a voyage of discovery. John, and Sebastian his son, sailed from Bristol in 1497, and saw the mainland of America at daybreak, June 24, of the same year,—probably the coast of Nova Scotia,—but did nothing. After their return to England, the elder Cabot died. In May, 1498, Sebastian sailed on his second voyage, which probably took him into Hudson's Bay and a few hundred miles down the coast. There is little probability in the theory that he ever saw any part of what is now the United States. He was a northern rover,—so thoroughly so, that the three[Pg 44] hundred colonists whom he brought out perished with cold in July.

England did not treat her one early explorer well; and in 1512 Cabot entered the more grateful service of Spain. In 1517 he sailed to the Spanish possessions in the West Indies, on which voyage he was accompanied by an Englishman named Thomas Pert. In August, 1526, Cabot sailed with another Spanish expedition bound for the Pacific, which had already been discovered by a heroic Spaniard; but his officers mutinied, and he was obliged to abandon his purpose. He explored the Rio de la Plata (the "Silver River") for a thousand miles, built a fort at one of the mouths of the Paraña, and explored part of that river and of the Paraguay,—for South America had been for nearly a generation a Spanish possession. Thence he returned to Spain, and later to England, where he died about 1557.

Of the rude maps which Cabot made of the New World, all are lost save one which is preserved in France; and there are no documents left of him. Cabot was a genuine explorer, and must be included in the list of the pioneers of America, but as one whose work was fruitless of consequences, and who saw, but did not take a hand in, the New World. He was a man of high courage and stubborn perseverance, and will be remembered as the discoverer of Newfoundland and the extreme northern mainland.

After Cabot, England took a nap of more than half a century. When she woke again, it was to find[Pg 45] that Spain's sleepless sons had scattered over half the New World; and that even France and Portugal had left her far behind. Cabot, who was not an Englishman, was the first English explorer; and the next were Drake and Hawkins, and then Captains Amadas and Barlow, after a lapse of seventy-five and eighty-seven years, respectively,—during which a large part of the two continents had been discovered, explored, and settled by other nations, of which Spain was undeniably in the lead. Columbus, the first Spanish explorer, was not a Spaniard; but with his first discovery began such an impetuous and unceasing rush of Spanish-born explorers as achieved more in a hundred years than all the other nations of Europe put together achieved here in America's first three hundred. Cabot saw and did nothing; and three quarters of a century later Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake—whom old histories laud greatly, but who got rich by selling poor Africans into slavery, and by actual piracy against unprotected ships and towns of the colonies of Spain, with which their mother England was then at peace—saw the West Indies and the Pacific, more than half a century after these had become possessions of Spain. Drake was the first Englishman to go through the Straits of Magellan,—and he did it sixty years after that heroic Portuguese had found them and christened them with his life-blood. Drake was probably first to see what is now Oregon,—his only important discovery. He "took possession" of Oregon for England, under the name of[Pg 46] "New Albion;" but old Albion never had a settlement there.

Sir John Hawkins, Drake's kinsman, was, like him, a distinguished sailor, but not a real discoverer or explorer at all. Neither of them explored or colonized the New World; and neither left much more impress on its history than if he had never been born. Drake brought the first potatoes to England; but the importance even of that discovery was not dreamed of till long after, and by other men.

Captains Amadas and Barlow, in 1584, saw our coast at Cape Hatteras and the island of Roanoke, and went away without any permanent result. The following year Sir Richard Grenville discovered Cape Fear, and there was an end of it. Then came Sir Walter Raleigh's famous but petty expeditions to Virginia, the Orinoco, and New Guinea, and the less important voyages of John Davis (in 1585-87) to the Northwest. Nor must we forget brave Martin Frobisher's fruitless voyages to Greenland in 1576-81. This was the end of England in America until the seventeenth century. In 1602 Captain Gosnold coasted nearly our whole Atlantic seaboard, particularly about Cape Cod; and five years later yet was the beginning of English occupancy in the New World. The first English settlement which made a serious mark on history—as Jamestown did not—was that of the Pilgrim Fathers in 1602; and they came not for the sake of opening a new world, but to escape the intolerance of the old. In fact, as Mr. Winsor has pointed out, the Saxon never took any particular interest in America until it began to be understood as a commercial opportunity.

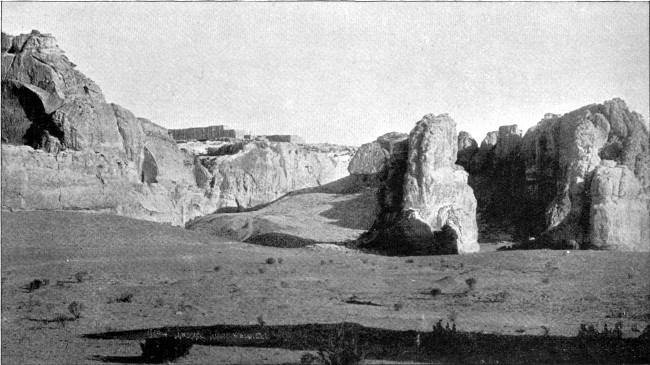

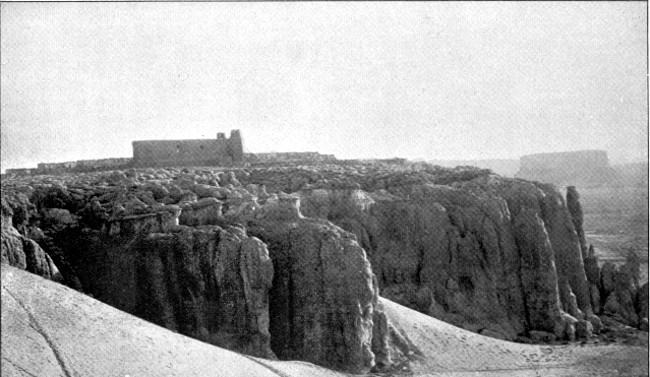

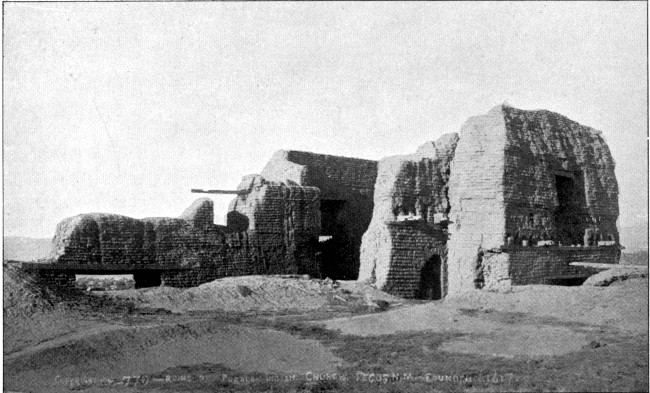

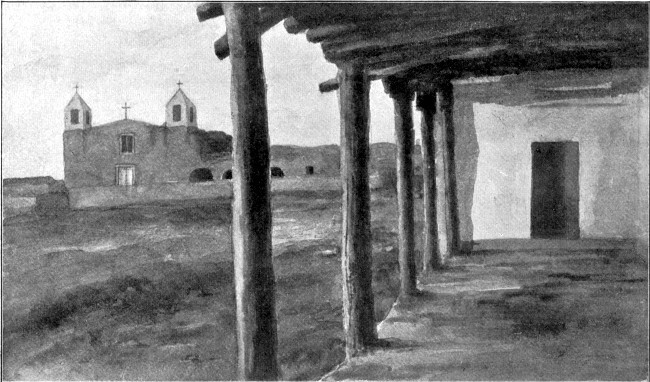

ONE OF THE MOQUI TOWNS.

ONE OF THE MOQUI TOWNS.But when we turn to Spain, what a record is that of the hundred years after Columbus and before Plymouth Rock! In 1499 Vincente Yañez de Pinzon, a companion of Columbus, discovered the coast of Brazil, and claimed the new country for Spain, but made no settlement. His discoveries were at the mouths of the Amazon and the Orinoco; and he was the first European to see the greatest river in the world. In the following year Pedro Alvarez Cabral, a Portuguese, was driven to the coast of Brazil by a storm, "took possession" for Portugal, and founded a colony there.

As to Amerigo Vespucci, the inconsiderable adventurer whose name so overshadows his exploits, his American claims are extremely dubious. Vespucci was born in Florence in 1451, and was an educated man,—his father being a notary and his uncle a Dominican who gave him a good schooling. He became a clerk in the great house of the Medicis, and in their service was sent to Spain about 1490. There he presently got into the employ of the merchant who fitted out Columbus's second expedition,—a Florentine named Juanoto Berardi. When Berardi died, in 1495, he left an unfinished contract to fit out twelve ships for the Crown; and Vespucci was intrusted with the completion of the contract. There is no reason whatever to believe[Pg 48] that he accompanied Columbus either on the first or the second voyage. According to his own story, he sailed from Cadiz May 10, 1497 (in a Spanish expedition), and reached the mainland eighteen days before Cabot saw it. The statement of encyclopædias that Vespucci "probably got as far north as Cape Hatteras" is ridiculous. The proof is absolute that he never saw an inch of the New World north of the equator. Returning to Spain in the latter part of 1498, he sailed again, May 16, 1499, with Ojeda, to San Domingo, a voyage on which he was absent about eighteen months. He left Lisbon on his third voyage, May 10, 1501, going to Brazil. It is not true, despite the encyclopædias, that he discovered and named the Bay of Rio Janeiro; both those honors belong to Cabral, the real discoverer and pioneer of Brazil, and a man of vastly greater historical importance than Vespucci. Vespucci's fourth voyage took him from Lisbon (June 10, 1503) to Bahia, and thence to Cape Frio, where he built a little fort. In 1504 he returned to Portugal, and in the following year to Spain, where he died in 1512.

These voyages rest only on Vespucci's own statements, which are not to be implicitly believed. It is probable that he did not sail at all in 1497, and quite certain that he had no share whatever in the real discoveries in the New World.

The name "America" was first invented and applied in 1507 by an ill-informed German printer, named Waldzeemüller, who had got hold of Amerigo[Pg 49] Vespucci's documents. History is full of injustices, but never a greater among them all than the christening of America. It would have been as appropriate to call it Walzeemüllera. The first map of America was made in 1500 by Juan de la Cosa, a Spaniard,—and a very funny map it would seem to the schoolboy of to-day. The first geography of America was by Enciso, a Spaniard, in 1517.

It is pleasant to turn from an overrated and very dubious man to those genuine but almost unheard-of Portuguese heroes, the brothers Gaspard and Miguel Corte-Real. Gaspard sailed from Lisbon in the year 1500, and discovered and named Labrador,—"the laborer." In 1501 he sailed again from Portugal to the Arctic, and never returned. After waiting a year, his brother Miguel led an expedition to find and rescue him; but he too perished, with all his men, among the ice-floes of the Arctic. A third brother wished to go in quest of the lost explorers, but was forbidden by the king, who himself sent out a relief expedition of two ships; but no trace of the gallant Corte-Reals, nor of any of their men, was ever found.

Such was the pioneering of America up to the end of the first decade of the sixteenth century,—a series of gallant and dangerous voyages (of which only the most notable ones of the great Spanish inrush have been mentioned), resulting in a few ephemeral colonies, but important only as a peep into the doors of the New World. The real hardships and dangers, the real exploration and conquest of the Americas,[Pg 50] began with the decade from 1510 to 1520,—the beginning of a century of such exploration and conquest as the world never saw before nor since. Spain had it all to herself, save for the heroic but comparatively petty achievements of Portugal in South America, between the Spanish points of conquest. The sixteenth century in the New World was unparalleled in military history; and it produced, or rather developed, such men as tower far above the later conquerors in their achievement. Our part of the hemisphere has never made such startling chapters of conquest as were carved in the grimmer wildernesses to our south by Cortez, Pizarro, Valdivia, and Quesada, the greatest subduers of wild America.

There were at least a hundred other early Spanish heroes, unknown to public fame and buried in obscurity until real history shall give them their well-earned praise. There is no reason to believe that these unremembered heroes were more capable of great things than our Israel Putnams and Ethan Allens and Francis Marions and Daniel Boones; but they did much greater things under the spur of greater necessity and opportunity. A hundred such, I say; but really the list is too long to be even catalogued here; and to pay attention to their greater brethren will fill this book. No other mother-nation ever bore a hundred Stanleys and four Julius Cæsars in one century; but that is part of what Spain did for the New World. Pizarro, Cortez, Valdivia, and Quesada are entitled to be called the Cæsars of the New World; and no other conquests in the history of[Pg 51] America are at all comparable to theirs. As among the four, it is almost difficult to say which was greatest; though there is really but one answer possible to the historian. The choice lies of course between Cortez and Pizarro, and for years was wrongly made. Cortez was first in time, and his operations seem to us nearer home. He was a highly educated man for his time, and, like Cæsar, had the advantage of being able to write his own biography; while his distant cousin Pizarro could neither read nor write, but had to "make his mark,"—a striking contrast with the bold and handsome (for those days) autograph of Cortez. But Pizarro—who had this lack of education as a handicap from the first, who went through infinitely greater hardships and difficulties than Cortez, and managed the conquest of an area as great with a third as many men as Cortez had, and very much more desperate and rebellious men—was beyond question the greatest Spanish American, and the greatest tamer of the New World. It is for that reason, and because such gross injustice has been done him, that I have chosen his marvellous career, to be detailed later in this book, as a picture of the supreme heroism of the Spanish pioneers.

But while Pizarro was greatest, all four were worthy the rank they have been assigned as the Cæsars of America.

Certain it is that the bald-headed little great man of old Rome, who crowds the page of ancient history, did nothing greater than each of those four Spanish heroes, who with a few tattered Spaniards[Pg 52] in place of the iron legions of Rome conquered each an inconceivable wilderness as savage as Cæsar found, and five times as big. Popular opinion long did a vast injustice to these and all other of the Spanish conquistadores, belittling their military achievements on account of their alleged great superiority of weapons over the savages, and taxing them with a cruel and relentless extermination of the aborigines. The clear, cold light of true history tells a different tale. In the first place, the advantage of weapons was hardly more than a moral advantage in inspiring awe among the savages at first, for the sadly clumsy and ineffective firearms of the day were scarcely more dangerous than the aboriginal bows which opposed them. They were effective at not much greater range than arrows, and were tenfold slower of delivery. As to the cumbrous and usually dilapidated armor of the Spaniard and his horse, it by no means fully protected either from the agate-tipped arrows of the savages; and it rendered both man and beast ill-fitted to cope with their agile foes in any extremity, besides being a frightful burden in those tropic heats. The "artillery" of the times was almost as worthless as the ridiculous arquebuses. As to their treatment of the natives, there was incomparably less cruelty suffered by the Indians who opposed the Spaniards than by those who lay in the path of any other European colonizers. The Spanish did not obliterate any aboriginal nation,—as our ancestors obliterated scores,—but followed the first necessarily bloody lesson with humane education[Pg 53] and care. Indeed, the actual Indian population of the Spanish possessions in America is larger to-day than it was at the time of the conquest; and in that astounding contrast of conditions, and its lesson as to contrast of methods, is sufficient answer to the distorters of history.

Before we come to the great conquerors, however, we must outline the eventful career and tragic end of the discoverer of the Pacific Ocean, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. In one of the noblest poems in the English language we read,—

But Keats was mistaken. It was not Cortez who first saw the Pacific, but Balboa,—five years before Cortez came to the mainland of America at all.

Balboa was born in the province of Estremadura, Spain, in 1475. In 1501 he sailed with Bastidas for the New World, and then saw Darien, but settled on the island of Española. Nine years later he sailed to Darien with Enciso, and there remained. Life in the New World then was a troublous affair, and the first years of Balboa's life there were eventful enough, though we must pass them over. Quarrels presently arose in the colony of Darien. Enciso was deposed and shipped back to Spain a prisoner, and Balboa took command. Enciso, upon his arrival in Spain, laid all the blame upon Balboa, and got him condemned by the king for high treason.[Pg 54] Learning of this, Balboa determined upon a master-stroke whose brilliancy should restore him to the royal favor. From the natives he had heard of the other ocean and of Peru,—neither yet seen by European eyes,—and made up his mind to find them. In September, 1513, he sailed to Coyba with one hundred and ninety men, and from that point, with only ninety followers, tramped across the Isthmus to the Pacific,—for its length one of the most frightful journeys imaginable. It was on the 26th of September, 1513, that from the summit of the divide the tattered, bleeding heroes looked down upon the blue infinity of the South Sea,—for it was not called the Pacific until long after. They descended to the coast; and Balboa, wading out knee-deep into the new ocean, holding aloft in his right hand his slender sword, and in his left the proud flag of Spain, took solemn possession of the South Sea in the name of the King of Spain.

The explorers got back to Darien Jan. 18, 1514, and Balboa sent to Spain an account of his great discovery. But Pedro Arias de Avila had already sailed from the mother country to supplant him. At last, however, Balboa's brilliant news reached the king, who forgave him, and made him adelantado; and soon after he married the daughter of Pedro Arias. Still full of great plans, Balboa carried the necessary material across the Isthmus with infinite toil, and on the shores of the blue Pacific put together the first ships in the Americas,—two brigantines. With these he took possession of the[Pg 55] Pearl Islands, and then started out to find Peru, but was driven back by storms to an ignoble fate. His father-in-law, becoming jealous of Balboa's brilliant prospects, enticed him back to Darien by a treacherous message, seized him, and had him publicly executed, on the trumped-up charge of high treason, in 1517. Balboa had in him the making of an explorer of the first rank, and but for De Avila's shameless deed might probably have won even higher honors. His courage was sheer audacity, and his energy tireless; but he was unwisely careless in his attitude toward the Crown.

While the discoverer of the greatest ocean was still striving to probe its farther mysteries, a handsome, athletic, brilliant young Spaniard, who was destined to make much more noise in history, was just beginning to be heard of on the threshold of America, of whose central kingdoms he was soon to be conqueror.

Hernando Cortez came of a noble but impoverished Spanish family, and was born in Estremadura ten years later than Balboa. At the age of fourteen he was sent to the University of Salamanca to study for the law; but the adventurous spirit of the man was already strong in the slender lad, and in a couple of years he left college, and went home determined upon a life of roving. The air was full of Columbus and his New World; and what spirited youth could stay to pore in musty law-books then? Not the irrepressible Hernando, surely.

Accidents prevented him from accompanying two expeditions for which he had made ready; but at last, in 1504, he sailed to San Domingo, in which new colony of Spain he made such a record that Ovando, the commander, several times promoted him, and he earned the reputation of a model soldier.[Pg 57] In 1511 he accompanied Velasquez to Cuba, and was made alcalde (judge) of Santiago, where he won further praise by his courage and firmness in several important crises. Meantime Francisco Hernandez de Cordova, the discoverer of Yucatan,—a hero with this mere mention of whom we must content ourselves,—had reported his important discovery. A year later, Grijalva, the lieutenant of Velasquez, had followed Cordova's course, and gone farther north, until at last he discovered Mexico. He made no attempt, however, to conquer or to colonize the new land; whereat Velasquez was so indignant that he threw Grijalva in disgrace, and intrusted the conquest to Cortez. The ambitious young Spaniard sailed from Santiago (Cuba) Nov. 18, 1518, with less than seven hundred men and twelve little cannon of the class called falconets. No sooner was he fairly off than Velasquez repented having given him such a chance for distinction, and directly sent out a force to arrest and bring him back. But Cortez was the idol of his little army, and secure in its fondness for him he bade defiance to the emissaries of Velasquez, and held on his way.[4] He landed on the coast of Mexico March 4, 1519, near where is now the city of Vera Cruz (the True Cross), which he founded,—the first European town on the mainland of America as far north as Mexico.[Pg 58]

The landing of the Spaniards caused as great a sensation as would the arrival in New York to-day of an army from Mars.[5] The awe-struck natives had never before seen a horse (for it was the Spanish who brought the first horses, cattle, sheep, and other domestic animals to the New World), and decided that these strange, pale new-comers who sat on four-legged beasts, and had shirts of iron and sticks that made thunder, must indeed be gods.

Here the adventurers were inflamed by golden stories of Montezuma,—a myth which befooled Cortez no more egregiously than it has befooled some modern historians, who seem unable to discriminate between what Cortez heard and what he found. He was told that Montezuma—whose name is properly Moctezuma, or Motecuzoma, meaning "Our Angry Chief"—was "emperor" of Mexico, and that thirty "kings," called caciques, were his vassals; that he had incalculable wealth and absolute power, and dwelt in a blaze of gold and precious stones! Even some most charming historians have fallen into the sad blunder of accepting these impossible myths. Mexico never had but two emperors,—Augustin de Iturbide and the hapless Maximilian,—both in this present century; and Moctezuma was neither its emperor nor even its king. The social and political organization of the ancient Mexicans was exactly like that of the[Pg 59] Pueblo Indians of New Mexico at the present day,—a military democracy, with a mighty and complicated religious organization as its "power behind the throne." Moctezuma was merely Tlacatécutle, or head war-chief of the Nahuatl (the ancient Mexicans), and neither the supreme nor the only executive. Of just how little importance he really was may be gathered from his fate.

Having founded Vera Cruz, Cortez caused himself to be elected governor and captain-general (the highest military rank)[6] of the new country; and having burned his ships, like the famous Greek commander, that there might be no retreat, he began his march into the grim wilderness before him.

It was now that Cortez began to show particularly that military genius which lifted him so far above all other pioneers of America except Pizarro. With only a handful of men,—for he had left part of his forces at Vera Cruz, under his lieutenant Escalante,—in an unknown land swarming with powerful and savage foes, mere courage and brute force would have stood him in little stead. But with a diplomacy as rare as it was brilliant, he found the weak spots in the Indian organization, widened the jealous breaches between tribes, made allies of those who were secretly or openly opposed to Moctezuma's federation of tribes,—a league which somewhat resembled the Six Nations of our own history,—and thus vastly reduced the forces to be directly conquered. Having routed the tribes of[Pg 60] Tlacala (pronounced Tlash-cáh-lah) and Cholula, Cortez came at last to the strange lake-city of Mexico, with his little Spanish troop swelled by six thousand Indian allies. Moctezuma received him with great ceremony, but undoubtedly with treacherous intent. While he was entertaining his visitors in one of the huge adobe houses,—not a "palace," as the histories tell us, for there were no palaces whatever in Mexico,—one of the sub-chiefs of his league attacked Escalante's little garrison at Vera Cruz and killed several Spaniards, including Escalante himself. The head of the Spanish lieutenant was sent to the City of Mexico,—for the Indians south of what is now the United States took not merely the scalp but the whole head of an enemy. This was a direful disaster, not so much for the loss of the few men as because it proved to the Indians (as the senders intended it to prove) that the Spaniards were not immortal gods after all, but could be killed the same as other men.

As soon as Cortez heard the ill news he saw this danger at once, and made a bold stroke to save himself. He had already strongly fortified the adobe building in which the Spaniards were quartered; and now, going by night with his officers to the house of the head war-captain, he seized Moctezuma and threatened to kill him unless he at once gave up the Indians who had attacked Vera Cruz. Moctezuma delivered them up, and Cortez at once had them burned in public. This was a cruel thing, though it was undoubtedly necessary to make some[Pg 61] vivid impression on the savages or be at once annihilated by them. There is no apology for this barbarity, yet it is only just that we measure Cortez by the standard of his time,—and it was a very cruel world everywhere then.

It is amusing here to read in pretentious text-books that "Cortez now ironed Montezuma and made him pay a ransom of six hundred thousand marks of pure gold and an immense quantity of precious stones." That is on a par with the impossible fables which lured so many of the early Spaniards to disappointment and death, and is a fair sample of the gilded glamour with which equally credulous historians still surround early America. Moctezuma did not buy himself free,—he never was free again,—and he paid no ransom of gold; while as for precious stones, he may have had a few native garnets and worthless green turquoises, and perhaps even an emerald pebble, but nothing more.

Just at this crisis in the affairs of Cortez he was threatened from another quarter. News came that Pamfilo de Narvaez, of whom we shall see more presently, had landed with eight hundred men to arrest Cortez and carry him back prisoner for his disobedience of Velasquez. But here again the genius of the conqueror of Mexico saved him. Marching against Narvaez with one hundred and forty men, he arrested Narvaez, enlisted under his own banner the welcome eight hundred who had come to arrest him, and hastened back to the City of Mexico.[Pg 62]

Here he found matters growing daily to more deadly menace. Alvarado, whom he had left in command, had apparently precipitated trouble by attacking an Indian dance. Wanton as that may seem and has been charged with being, it was only a military necessity, recognized by all who really know the aborigines even to this day. The closet-explorers have pictured the Spaniards as wickedly falling upon an aboriginal festival; but that is simply because of ignorance of the subject. An Indian dance is not a festival; it is generally, and was in this case, a grim rehearsal for murder. An Indian never dances "for fun," and his dances too often mean anything but fun for other people. In a word, Alvarado, seeing in progress a dance which was plainly only the superstitious prelude to a massacre, had tried to arrest the medicine-men and other ringleaders. Had he succeeded, the trouble would have been over for a time at least. But the Indians were too numerous for his little force, and the chief instigators of war escaped.

When Cortez came back with his eight hundred strangely-acquired recruits, he found the whole city with its mask thrown off, and his men penned up in their barracks. The savages quietly let Cortez enter the trap, and then closed it so that there was no more getting out. There were the few hundred Spaniards cooped up in their prison, and the four dykes which were the only approaches to it—for the City of Mexico was an American Venice—swarming with savage foes by the countless thousands.[Pg 63]

The Indian makes very few excuses for failure; and the Nahuatl had already elected a new head war-captain named Cuitlahuátzin in place of the unsuccessful Moctezuma. The latter was still a prisoner; and when the Spaniards brought him out upon the housetop to speak to his people in their behalf, the infuriated multitude of Indians pelted him to death with stones. Then, under their new war-captain, they attacked the Spaniards so furiously that neither the strong walls nor the clumsy falconets, and clumsier flintlocks, could withstand them; and there was nothing for the Spaniards but to cut their way out along one of the dykes in a last desperate struggle for life. The beginning of that six days' retreat was one of the bitterest pages in American history. Then was the Noche Triste (the Sad Night), still celebrated in Spanish song and story. For that dark night many a proud home in mother Spain was never bright again, and many a fond heart broke with the crimson bubbles on the Lake of Tezcuco. In those few ghastly hours two thirds of the conquerors were slain; and across more than eight hundred Spanish corpses the frenzied savages pursued the bleeding survivors.

After a fearful retreat of six days, came the important running fight in the plains of Otumba, where the Spaniards were entirely surrounded, but cut their way out after a desperate hand-to-hand struggle which really decided the fate of Mexico. Cortez marched to Tlacala, raised an army of Indians[Pg 64] who were hostile to the federation, and with their help laid siege to the City of Mexico. This siege lasted seventy-three days, and was the most remarkable in the history of all America. There was hard fighting every day. The Indians made a superb defence; but at last the genius of Cortez triumphed, and on the 13th of August, 1521, he marched victorious into the second greatest aboriginal city in the New World.

These wonderful exploits of Cortez, so briefly outlined here, awoke boundless admiration in Spain, and caused the Crown to overlook his insubordination to Velasquez. The complaints of Velasquez were disregarded, and Charles V. appointed Cortez governor and captain-general of Mexico, besides making him Marquis de Oaxaca with a handsome revenue.

Safely established in this high authority, Cortez crushed a plot against him, and executed the new war-captain, with many of the caciques (who were not potentates at all, but religious-military officers, whose hold on the superstitions of the Indians made them dangerous).

But Cortez, whose genius shone only the brighter when the difficulties and dangers before him seemed insurmountable, tripped up on that which has thrown so many,—success. Unlike his unlearned but nobler and greater cousin Pizarro, prosperity spoiled him, and turned his head and his heart. Despite the unstudious criticisms of some historians, Cortez was not a cruel conqueror. He was not only a great[Pg 65] military genius, but was very merciful to the Indians, and was much beloved by them. The so-called massacre at Cholula was not a blot on his career as has been alleged. The truth, as vindicated at last by real history, is this: The Indians had treacherously drawn him into a trap under pretext of friendship. Not until too late to retreat did he learn that the savages meant to massacre him. When he did see his danger, there was but one chance,—namely, to surprise the surprisers, to strike them before they were ready to strike him; and this is only what he did. Cholula was simply a case of the biter bitten.

No, Cortez was not cruel to the Indians; but as soon as his rule was established he became a cruel tyrant to his own countrymen, a traitor to his friends and even to his king,—and, worst of all, a cool assassin. There is strong evidence that he had "removed" several persons who were in the way of his unholy ambitions; and the crowning infamy was in the fate of his own wife. Cortez had long for a mistress the handsome Indian girl Malinche; but after he had conquered Mexico, his lawful wife came to the country to share his fortunes. He did not love her, however, as much as he did his ambition; and she was in his way. At last she was found in her bed one morning, strangled to death.

Carried away by his ambition, he actually plotted open rebellion against Spain and to make himself emperor of Mexico. The Crown got wind of this precious plan, and sent out emissaries who seized[Pg 66] his goods, imprisoned his men, and prepared to thwart his secret schemes. Cortez boldly hastened to Spain, where he met his sovereign with great splendor. Charles received him well, and decorated him with the illustrious Order of Santiago, the patron saint of Spain. But his star was already declining; and though he was allowed to return to Mexico with undiminished outward power, he was thenceforth watched, and did nothing more that was comparable with his wonderful earlier achievements. He had become too unscrupulous, too vindictive, and too unsafe to be left in authority; and after a few years the Crown was forced to appoint a viceroy to wield the civil power of Mexico, leaving to Cortez only the military command, and permission for further conquests. In 1536 Cortez discovered Lower California, and explored part of its gulf. At last, disgusted with his inferior position where he had once been supreme, he returned to Spain, where the emperor received him coldly. In 1541 he accompanied his sovereign to Algiers as an attaché, and in the wars there acquitted himself well. Soon after their return to Spain, however, he found himself neglected. It is said that one day when Charles was riding in state, Cortez forced his way to the royal carriage and mounted upon the step determined to force recognition.

"Who are you?" demanded the angry emperor.

"A man, your Highness," retorted the haughty conqueror of Mexico, "who has given you more provinces than your forefathers left you cities!"[Pg 67]

Whether the story is true or not, it graphically illustrates the arrogance as well as the services of Cortez. He lacked the modest balance of the greatest greatness, just as Columbus had lacked it. The self-assertion of either would have been impossible to the greater man than either,—the self-possessed Pizarro.

At last, in disgust, Cortez retired from court; and on the 2d of December, 1554, the man who had first opened the interior of America to the world died near Seville.

There were some in South America whose achievements were as wondrous as those of Cortez in Mexico. The conquest of the two continents was practically contemporaneous, and equally marked by the highest military genius, the most dauntless courage, the overcoming of dangers which were appalling, and hardships which were wellnigh superhuman.

Francisco Pizarro, the unlettered but invincible conqueror of Peru, was fifteen years older than his brilliant cousin Cortez, and was born in the same province of Spain. He began to be heard of in America in 1510. From 1524 to 1532 he was making superhuman efforts to get to the unknown and golden land of Peru, overcoming such obstacles as not even Columbus had encountered, and enduring greater dangers and hardships than Napoleon or Cæsar ever met. From 1532 to his death in 1541, he was busy in conquering and exploring that enormous area, and founding a new nation amid its fierce tribes,—fighting off not only the vast hordes[Pg 68] of Indians, but also the desperate men of his own forces, by whose treachery he at last perished. Pizarro found and tamed the richest country in the New World; and with all his unparalleled sufferings still realized, more than any other of the conquerors, the golden dreams which all pursued. Probably no other conquest in the world's history yielded such rapid and bewildering wealth, as certainly none was bought more dearly in hardship and heroism. Pizarro's conquest has been most unjustly dealt with by some historians ignorant of the real facts in the case, and blinded by prejudice; but that marvellous story, told in detail farther on, is coming to its proper rank as one of the most stupendous and gallant feats in all history. It is the story of a hero to whom every true American, young or old, will be glad to do justice. Pizarro has been long misrepresented as a blood-stained and cruel conqueror, a selfish, unprincipled, unreliable man; but in the clear, true light of real history he stands forth now as one of the greatest of self-made men, and one who, considering his chances, deserves the utmost respect and admiration for the man he made of himself. The conquest of Peru did not by far cause as much bloodshed as the final reduction of the Indian tribes of Virginia. It counted scarcely as many Indian victims as King Philip's War, and was much less bloody, because more straightforward and honorable, than any of the British conquests in East India. The most bloody events in Peru came after the conquest was over, when the Spaniards[Pg 69] fell to fighting one another; and in this Pizarro was not the aggressor but the victim. It was the treachery of his own allies,—the men whose fames and fortunes he had made. His conquest covered a land as big as California, Oregon, and most of Washington,—or as our whole seaboard from Nova Scotia to Port Royal and two hundred miles inland,—swarming with the best organized and most advanced Indians in the Western Hemisphere; and he did it all with less than three hundred gaunt and tattered men. He was one of the great captains of all time, and almost as remarkable as organizer and executive of a new empire, the first on the Pacific shore of the southern continent. To this greatness rose the friendless, penniless, ignorant swineherd of Truxillo!

Pedro de Valdivia, the conqueror of Chile, subdued that vast area of the deadly Araucanians with an "army" of two hundred men. He established the first colony in Chile in 1540, and in the following February founded the present city of Santiago de Chile. Of his long and deadly wars with the Araucanians there is not space to speak here. He was killed by the savages Dec. 3, 1553, with nearly all his men, after an indescribably desperate struggle.