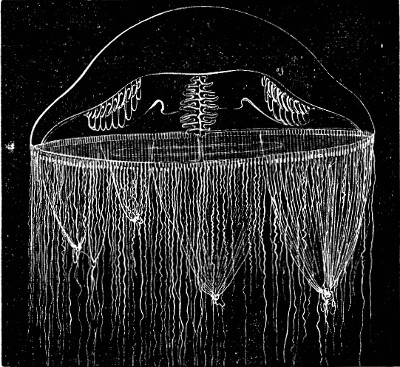

Ptychogena lactea.

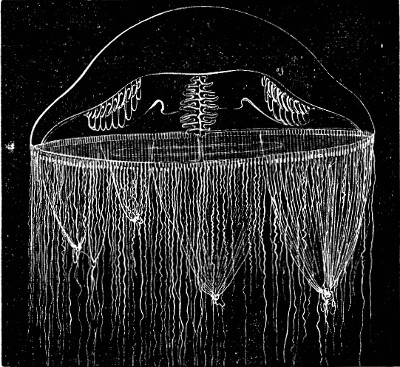

Ptychogena lactea.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 16, No. 98, December, 1865, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 16, No. 98, December, 1865 Author: Various Release Date: June 28, 2010 [EBook #33009] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ATLANTIC MONTHLY, DECEMBER 1865 *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections.)

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1865, by Ticknor and Fields, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Transcriber's Note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of contents has been created for the HTML version.

GRIFFITH GAUNT; OR, JEALOUSY.

THE PARTING OF HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE.

WILLIAM BLACKWOOD.

THE CHIMNEY-CORNER.

THE FORGE.

KING JAMES THE FIRST.

THE SLEEPER.

DOCTOR JOHNS.

BOOKS FOR OUR CHILDREN.

DIOS TE DE.

MODE OF CATCHING JELLY-FISHES.

ADELAIDE ANNE PROCTER.

BEYOND.

CLEMENCY AND COMMON SENSE.

REVIEWS AND LITERARY NOTICES.

"Then I say, once for all, that priest shall never darken my doors again."

"Then I say they are my doors, and not yours, and that holy man shall brighten them whenever he will."

The gentleman and lady, who faced each other pale and furious, and interchanged this bitter defiance, were man and wife, and had loved each other well.

Miss Catharine Peyton was a young lady of ancient family in Cumberland, and the most striking, but least popular, beauty in the county. She was very tall and straight, and carried herself a little too imperiously; yet she would sometimes relax and all but dissolve that haughty figure, and hang sweetly drooping over her favorites; then the contrast was delicious, and the woman fascinating.

Her hair was golden and glossy, her eyes a lovely gray; and she had a way of turning them on slowly and full, so that their victim could not fail to observe two things: first, that they were grand and beautiful orbs; secondly, that they were thoughtfully overlooking him, instead of looking at him.

So contemplated by glorious eyes, a man feels small and bitter.

Catharine was apt to receive the blunt compliments of the Cumberland squires with this sweet, celestial, superior gaze, and for this and other imperial charms was more admired than liked.

The family estate was entailed on her brother; her father spent every farthing he could; so she had no money, and no expectations, except from a distant cousin,—Mr. Charlton, of Hernshaw Castle and Bolton Hall.

Even these soon dwindled. Mr. Charlton took a fancy to his late wife's relation, Griffith Gaunt, and had him into his house, and treated him as his heir. This disheartened two admirers who had hitherto sustained Catharine Peyton's gaze, and they retired. Comely girls, girls long-nosed, but rich, girls snub-nosed, but winning, married on all sides of her; but the imperial beauty remained Miss Peyton at two-and-twenty.

She was rather kind to the poor; would give them money out of her slender purse, and would even make clothes for the women, and sometimes read to them: very few of them could read to themselves in that day. All she required in return was, that they should be Roman Catholics, like herself, or at least pretend they might be brought to that faith by little and little.

She was a high-minded girl, and could be a womanly one,—whenever she chose.

She hunted about twice a week in the season, and was at home in the saddle, for she had ridden from a child; but so ingrained was her character, that this sport, which more or less unsexes most women, had no perceptible effect on her mind, nor even on her manners. The scarlet riding-habit and little purple cap, and the great, white, bony horse she rode, were often seen in a good place at the end of a long run; but, for all that, the lady was a most ungenial fox-huntress. She never spoke a word but to her acquaintances, and wore a settled air of dreamy indifference, except when the hounds happened to be in full cry, and she galloping at their heels. Worse than that, when the dogs were running into the fox, and his fate certain, she had been known to rein in her struggling horse, and pace thoughtfully home, instead of coming in at the death, and claiming the brush.

One day, being complimented at the end of a hard run by the gentleman who kept the hounds, she turned her celestial orbs on him, and said,—

"Nay, Sir Ralph, I love to gallop; and this sorry business gives me an excuse."

It was full a hundred years ago. The country teemed with foxes; but it abounded in stiff coverts, and a knowing fox was sure to run from one to another; and then came wearisome efforts to dislodge him; and then Miss Peyton's gray eyes used to explore vacancy, and ignore her companions, biped and quadruped.

But one day they drew Yewtree Brow, and found a stray fox. At Gaylad's first note he broke cover, and went away for home across the open country. A hedger saw him steal out, and gave a view halloo; the riders came round helter-skelter; the dogs in cover one by one threw up their noses and voices; the horns blew, the canine music swelled to a strong chorus, and away they swept across country,—dogs, horses, men; and the Deuse take the hindmost!

It was a gallant chase, and our dreamy virgin's blood got up. Erect, but lithe and vigorous, and one with her great white gelding, she came flying behind the foremost riders, and took leap for leap with them. One glossy, golden curl streamed back in the rushing air; her gray eyes glowed with earthly fire; and two red spots on the upper part of her cheeks showed she was much excited, without a grain of fear. Yet in the first ten minutes one gentleman was unhorsed before her eyes, and one came to grief along with his animal, and a thorough-bred chestnut was galloping and snorting beside her with empty saddle. Presently young Featherstone, who led her by about fifteen yards, crashed through a high hedge, and was seen no more, but heard wallowing in the deep, unsuspected ditch beyond. There was no time to draw bridle. "Lie still, Sir, if you please," said Catharine, with cool civility; then up rein, in spur, and she cleared the ditch and its muddy contents, alive and dead, and away without looking behind her.

On, on, on, till all the pinks and buckskins, erst so smart, were splashed with clay and dirt of every hue, and all the horses' late glossy coats were bathed with sweat and lathered with foam, and their gaping nostrils blowing and glowing red; and then it was that Harrowden Brook, swollen wide and deep by the late rains, came right between the fox and Dogmore Underwood, for which he was making.

The hunt sweeping down a hillside caught sight of Reynard running for the brook. They made sure of him now. But he lapped a drop, and then slipped in, and soon crawled out on the other[Pg 643] side, and made feebly for the covert, weighted with wet fur.

At sight of him, the hunt hallooed and trumpeted, and came tearing on with fresh vigor.

But when they came near the brook, lo, it was twenty feet wide, and running fast and brown. Some riders skirted it, looking for a narrow part. Two horses, being spurred at it, came to the bank, and then went rearing round on their heels, depositing one hat and another rider in the current. One gallant steed planted his feet like a tower, and snorted down at the water. One flopped gravely in, and had to swim, and be dragged out. Another leaped, and landed with his feet on the other bank, his haunches in the water, and his rider curled round his neck, and glaring out between his retroverted ears.

But Miss Peyton encouraged her horse with spur and voice, set her teeth, turned rather pale this time, and went at the brook with a rush, and cleared it like a deer. She and the huntsman were almost alone together on the other side, and were as close to the dogs as the dogs were to poor Pug, when he slipped through a run in a quickset hedge, and, reducing the dogs to single file, glided into Dogmore Underwood, a stiff hazel coppice of five years' growth.

The other riders soon straggled up, and then the thing was to get him out again. There were a few narrow roads cut in the underwood; and up and down these the huntsman and whipper-in went trotting, and encouraged the stanch hounds, and whipped the skulkers back into covert. Others galloped uselessly about, pounding the earth, for daisy-cutters were few in those days; and Miss Peyton relapsed into the transcendental. She sat in one place, with her elbow on her knee, and her fair chin supported by two fingers, as undisturbed by the fracas of horns and voices as an equestrian statue of Diana.

She sat so still and so long at a corner of the underwood that at last the harassed fox stole out close to her with lolling tongue and eye askant, and took the open field again. She thrilled at first sight of him, and her cheeks burned; but her quick eye took in all the signs of his distress, and she sat quiet, and watched him coolly. Not so her horse. He plunged, and then trembled all over, and planted his fore-feet together at this angle \, and parted his hind-legs a little, and so stood quivering, with cocked ears, and peeped over a low paling at the retiring quadruped, and fretted and sweated in anticipation of the gallop his long head told him was to follow. He looked a deal more statuesque than any three statues in England, and all about a creature not up to his knee.—And by the bye: the gentlemen who carve horses in our native isle, did they ever see one,—out of an omnibus?—The whipper-in came by, and found him in this gallant attitude, and suspected the truth, but, observing the rider's tranquil position, thought the fox had only popped out and then in again. However, he fell in with the huntsman, and told him Miss Peyton's gray had seen something. The hounds appeared puzzled; and so the huntsman rode round to Miss Peyton, and, touching his cap, asked her if she had seen nothing of the fox.

She looked him dreamily in the face.

"The fox?" said she; "he broke cover ten minutes ago."

The man blew his horn lustily, and then asked her reproachfully why she had not tally-hoed him, or winded her horn: with that he blew his own again impatiently.

Miss Peyton replied, very slowly and pensively, that the fox had come out soiled and fatigued, and trailing his brush. "I looked at him," said she, "and I pitied him. He was one, and we are many; he was so little, and we are so big; he had given us a good gallop; and so I made up my mind he should live to run another day."

The huntsman stared stupidly at her for a moment, then burst into a torrent of oaths, then blew his horn till it was hoarse, then cursed and swore till he was hoarse himself, then to his horn again, and dogs and men came rushing to the sound.[Pg 644]

"Couple up, and go home to supper," said Miss Peyton, quietly. "The fox is half-way to Gallowstree Gorse; and you won't get him out of that this afternoon, I promise you."

As she said this, she just touched her horse with the spur, leaped the low hedge in front of her, and cantered slowly home across country. She was one that seldom troubled the hard road, go where she would.

She had ridden about a mile, when she heard a horse's feet behind her. She smiled, and her color rose a little; but she cantered on.

"Halt, in the king's name!" shouted a mellow voice; and a gentleman galloped up to her side, and reined in his mare.

"What! have they killed?" inquired Catharine, demurely.

"Not they; he is in the middle of Gallowstree Gorse by now."

"And is this the way to Gallowstree Gorse?"

"Nay, Mistress," said the young man; "but when the fox heads one way and the deer another, what is a poor hunter to do?"

"Follow the slower, it seems."

"Say the lovelier and the dearer, sweet Kate."

"Now, Griffith, you know I hate flattery," said Kate; and the next moment came a soft smile, and belied this unsocial sentiment.

"Flattery?" said the lover. "I have no tongue to speak half your praises. I think the people in this country are as blind as bats, or they'd"——

"All except Mr. Griffith Gaunt; he has found a paragon, where wiser people see a wayward, capricious girl."

"Then he is the man for you. Don't you see that, Mistress?"

"No, I don't quite see that," said the lady, dryly.

This cavalier reply caused a dismay the speaker never intended. The fact is, Mr. George Neville, young, handsome, and rich, had lately settled in the neighborhood, and had been greatly smitten with Kate. The county was talking about it, and Griffith had been secretly on thorns for some days past. And now he could hide his uneasiness no longer; he cried out, in a sharp, trembling voice,—

"Why, Kate, my dear Kate! what! could you love any man but me? Could you be so cruel? could you? There, let me get off my horse, and lie down on this stubble, and you ride over me, and trample me to death. I would rather have you trample on my ribs than on my heart, with loving any one but me."

"Why, what now?" said Catharine, drawing herself up; "I must scold you handsomely"; and she drew rein and turned full upon him; but by this means she saw his face was full of real distress; so, instead of reprimanding him, she said, gently, "Why, Griffith, what is to do? Are you not my servant? Do not I send you word, whenever I dine from home?"

"Yes, dearest; and then I call at that house, and stick there till they guess what I would be at, and ask me, too."

Catharine smiled, and proceeded to remind him that thrice a week she permitted him to ride over from Bolton, (a distance of fifteen miles,) to see her.

"Yes," replied Griffith, "and I must say you always come, wet or dry, to the shrubbery-gate, and put your hand in mine a minute. And, Kate," said he, piteously, "at the bare thought of your putting that same dear hand in another man's, my heart turns sick within me, and my skin burns and trembles on me."

"But you have no cause," said Catharine, soothingly. "Nobody, except yourself, doubts my affection for you. You are often thrown in my teeth, Griffith,—and" (clenching her own) "I like you all the better, of course."

Griffith replied with a burst of gratitude; and then, as men will, proceeded to encroach.

"Ah," said he, "if you would but pluck up courage, and take the matrimonial fence with me at once."

Miss Peyton sighed at that, and drooped a little upon her saddle. After a pause, she enumerated the "just impediments."[Pg 645] She reminded him that neither of them had means to marry on.

He made light of that; he should soon have plenty; Mr. Charlton has as good as told him he was to have Bolton Hall and Grange: "Six hundred acres, Kate, besides the park and paddocks."

In his warmth he forgot that Catharine was to have been Mr. Charlton's heir. Catharine was too high-minded to bear Griffith any grudge; but she colored a little, and said she was averse to come to him a penniless bride.

"Why, what matters it which of us has the dross, so that there is enough for both?" said Griffith, with an air of astonishment.

Catharine smiled approbation, and tacitly yielded that point. But then she objected the difference in their faith.

"Oh, honest folk get to heaven by different roads," said Griffith, carelessly.

"I have been taught otherwise," replied Catharine, gravely.

"Then give me your hand and I'll give you my soul," said Griffith Gaunt, impetuously. "I'll go to heaven your way, if you can't go mine. Anything sooner than be parted in this world or the next."

She looked at him in silence; and it was in a faint, half apologetic tone she objected, that all her kinsfolk were set against it.

"It is not their business; it is ours," was the prompt reply.

"Well, then," said Catharine, sadly, "I suppose I must tell you the true reason: I feel I should not make you happy; I do not love you quite as you want to be loved, as you deserve to be loved. You need not look so; nothing in flesh and blood is your rival. But my heart bleeds for the Church; I think of her ancient glory in this kingdom, and, when I see her present condition, I long to devote myself to her service. I am very fit to be an abbess or a nun,—most unfit to be a wife. No, no,—I must not, ought not, dare not, marry a Protestant. Take the advice of one who esteems you dearly; leave me,—fly from me,—forget me,—do everything but hate me. Nay, do not hate me; you little know the struggle in my mind. Farewell; the saints, whom you scorn, watch over and protect you! Farewell!"

And with this she sighed, and struck her spur into the gray, and he darted off at a gallop.

Griffith, little able to cope with such a character as this, sat petrified, and would have been rooted to the spot, if he had happened to be on foot. But his mare set off after her companion, and a chase of a novel kind commenced. Catharine's horse was fresher than Griffith's mare, and the latter, not being urged by her petrified master, lost ground.

But when she drew near to her father's gate, Catharine relaxed her speed, and Griffith rejoined her.

She had already half relented, and only wanted a warm and resolute wooer to bring her round. But Griffith was too sore, and too little versed in woman. Full of suspicion and bitterness, he paced gloomy and silent by her side, till they reached the great avenue that led to her father's house.

And while he rides alongside the capricious creature in sulky silence, I may as well reveal a certain foible in his own character.

This Griffith Gaunt was by no means deficient in physical courage; but he was instinctively disposed to run away from mental pain the moment he lost hope of driving it away from him. For instance, if Catharine had been ill and her life in danger, he would have ridden day and night to save her,—would have beggared himself to save her; but if she had died, he would either have killed himself, or else fled the country, and so escaped the sight of every object that was associated with her and could agonize him. I do not think he could have attended the funeral of one he loved.

The mind, as well as the body, has its self-protecting instincts. This of Griffith's was, after all, an instinct of[Pg 646] that class, and, under certain circumstances, is true wisdom. But Griffith, I think, carried the instinct to excess; and that is why I call it his foible.

"Catharine," said he, resolutely, "let me ride by your side to the house for once; for I read your advice my own way, and I mean to follow it: after to-day you will be troubled with me no more. I have loved you these three years, I have courted you these two years, and I am none the nearer; I see I am not the man you mean to marry: so I shall do as my father did, ride down to the coast, and sell my horse, and ship for foreign parts."

"Oh, as you will," said Catharine, haughtily: she quite forgot she had just recommended him to do something of this very kind.

Presently she stole a look. His fine ruddy cheek was pale; his manly brown eyes were moist; yet a gloomy and resolute expression on his tight-drawn lips. She looked at him sidelong, and thought how often he had ridden thirty miles on that very mare to get a word with her at the shrubbery-gate. And now the mare to be sold! The man to go broken-hearted to sea,—perhaps to his death! Her good heart began to yearn.

"Griffith," said she, softly, "it is not as if I were going to wed anybody else. Is it nothing to be preferred by her you say you love? If I were you, I would do nothing rash. Why not give me a little time? In truth, I hardly know my own mind about it two days together."

"Kate," said the young man, firmly, "I am courting you this two years. If I wait two years more, it will be but to see the right man come and carry you in a month; for so girls are won, when they are won at all. Your sister that is married and dead, she held Josh Pitt in hand for years; and what is the upshot? Why, he wears the willow for her to this day; and her husband married again, before her grave was green. Nay, I have done all an honest man can to woo you; so take me now, or let me go."

At this, Kate began to waver secretly, and ask herself whether it would not be better to yield, since he was so abominably resolute.

But the unlucky fellow did not leave well alone. He went on to say,—

"Once out of sight of this place, I may cure myself of my fancy. Here I never could."

"Oh," said Catharine, directly, "if you are so bent on being cured, it would not become me to say nay."

Griffith Gaunt bit his lip and hung his head, and made no reply.

The patience with which he received her hard speech was more apparent than real; but it told. Catharine, receiving no fresh positive provocation, relented again of her own accord, and, after a considerable silence, whispered, softly,—

"Think how we should all miss you."

Here was an overture to reconciliation. But, unfortunately, it brought out what had long been rankling in Griffith's mind, and was in fact the real cause of the misunderstanding.

"Oh," said he, "those I care for will soon find another to take my place! Soon? quotha. They have not waited till I was gone for that."

"Ah, indeed!" said Catharine, with some surprise; then, like the quick-witted girl she was, "so this is what all the coil is about."

She then, with a charming smile, begged him to inform her who was his destined successor in her esteem. Griffith colored purple at her cool hypocrisy, (for such he considered it,) and replied, almost fiercely,—

"Who but that young black-a-viséd George Neville, that you have been coquetting with this month past,—and danced all night with him at Lady Munster's ball, you did."

Catharine blushed, and said, deprecatingly,—

"You were not there, Griffith, or to be sure I had not danced with him."

"And he toasts you by name, wherever he goes."

"Can I help that? Wait till I toast[Pg 647] him, before you make yourself ridiculous, and me very angry—about nothing."

Griffith, sticking to his one idea, replied, doggedly,—

"Mistress Alice Peyton shilly-shallied with her true lover for years, till Richard Hilton came, that was not fit to tie his shoes; and then"——

Catharine cut him short,—

"Affront me, if nothing less will serve; but spare my sister in her grave."

She began the sentence angrily, but concluded it in a broken voice. Griffith was half disarmed; but only half. He answered, sullenly,—

"She did not die till she had jilted an honest gentleman and broken his heart, and married a sot, to her cost. And you are of her breed, when all is done; and now that young coxcomb has come, like Dick Hilton, between you and me."

"But I do not encourage him."

"You do not discourage him," retorted Griffith, "or he would not be so hot after you. Were you ever the woman to say, 'I have a servant already that loves me dear'? That one frank word had sent him packing."

Miss Peyton colored, and the water came into her eyes.

"I may have been imprudent," she murmured. "The young gentleman made me smile with his extravagance. I never thought to be misunderstood by him, far less by you." Then, suddenly, as bold as brass,—"It's all your fault; if he had the power to make you uneasy, why did you not check me before?"

"Ay, forsooth, and have it cast in my teeth I was a jealous monster, and played the tyrant before my time. A poor fellow scarce knows what to be at that loves a coquette."

"Coquette I am none," replied the lady, bridling magnificently.

Griffith took no notice of this interruption. He proceeded to say that he had hitherto endured this intrusion of a rival in silence, though with a sore heart, hoping his patience might touch her, or the fire go out of itself. But at last, unable to bear it any longer in silence, he had shown his wound to one he knew could feel for him, his poor friend Pitt. Pitt had then let him know that his own mistake had been over-confidence in Alice Peyton's constancy.

"He said to me, 'Watch your Kate close, and, at the first blush of a rival, say you to her, Part with him, or part with me.'"

Catharine pinned him directly.

"And this is how you take Joshua Pitt's advice,—by offering to run away from this sorry rival."

The shrewd reply, and a curl of the lip, half arch, half contemptuous, that accompanied the thrust, staggered the less ready Griffith. He got puzzled, and showed it.

"Well, but," stammered he at last, "your spirit is high; I was mostly afeard to put it so plump to you. So I thought I would go about a bit. However, it comes to the same thing; for this I do know,—that, if you refuse me your hand this day, it is to give it to a new acquaintance, as your Alice did before you. And if it is to be so, 'tis best for me to be gone: best for him, and best for you. You don't know me, Kate; for, as clever as you are, at the thought of your playing me false, after all these years, and marrying that George Neville, my heart turns to ice, and then to fire, and my head seems ready to burst, and my hands to do mad and bloody acts. Ay, I feel I should kill him, or you, or both, at the church-porch. Ah!"

He suddenly griped her arm, and at the same time involuntarily checked his mare.

Both horses stopped.

She raised her head with an inquiring look, and saw her lover's face discolored with passion, and so strangely convulsed that she feared at first he was in a fit, or stricken with death or palsy.

She uttered a cry of alarm, and stretched forth her hand towards him.

But the next moment she drew it back from him; for, following his eye, she discerned the cause of this ghastly look. Her father's house stood at the end of[Pg 648] the avenue they had just entered; but there was another approach to it, namely, by a bridle-road at right angles to the avenue or main entrance; and up that bridle-road a gentleman was walking his horse, and bid fair to meet them at the hall-door.

It was young Neville. There was no mistaking his piebald charger for any other animal in that county.

Kate Peyton glanced from lover to lover, and shuddered at Griffith. She was familiar with petty jealousy; she had even detected it pinching or coloring many a pretty face that tried very hard to hide it all the time. But that was nothing to what she saw now: hitherto she had but beheld the feeling of jealousy; but now she witnessed the livid passion of jealousy writhing in every lineament of a human face. That terrible passion had transfigured its victim in a moment: the ruddy, genial, kindly Griffith, with his soft brown eye, was gone; and in his place lowered a face older, and discolored, and convulsed, and almost demoniacal.

Women (wiser, perhaps, in this than men) take their strongest impressions by the eye, not ear. Catharine, I say, looked at him she had hitherto thought she knew,—looked and feared him. And even while she looked and shuddered, Griffith spurred his mare sharply, and then drew her head across the gray gelding's path. It was an instinctive impulse to bar the lady he loved from taking another step towards the place where his rival awaited her.

"I cannot bear it," he gasped. "Choose you now, once for all, between that puppy there and me": and he pointed with his riding-whip at his rival, and waited with his teeth clenched for her decision.

The movement was rapid, the gesture large and commanding, and the words manly: for what says the fighting poet?—

Miss Peyton drew herself up and back by one motion, like a queen at bay; but still she eyed him with a certain respect, and was careful now not to provoke nor pain him needlessly.

"I prefer you,—though you speak harshly to me, Sir," said she, with gentle dignity.

"Then give me your hand, with that man in sight, and end my torments; promise to marry me this very week. Ah, Kate, have pity on your poor, faithful servant, who has loved you so long!"

"I do, Griffith, I do," said she, sweetly; "but I shall never marry now. Only set your mind at rest about Mr. Neville there. He has never asked me, for one thing."

"He soon will, then."

"No, no; I declare I will be very cool to him, after what you have said to me. But I cannot marry you, neither. I dare not. Listen to me, and do, pray, govern your temper, as I am doing mine. I have often read of men with a passion for jealousy,—I mean, men whose jealousy feeds upon air, and defies reason. I know you now for such a man. Marriage would not cure this madness; for wives do not escape admiration any more than maids. Something tells me you would be jealous of every fool that paid me some stale compliment, jealous of my female friends, and jealous of my relations, and perhaps jealous of your own children, and of that holy, persecuted Church which must still have a large share of my heart. No, no; your face and your words have shown me a precipice. I tremble and draw back, and now I never will marry at all: from this day I give myself to the Church."

Griffith did not believe one word of all this.

"That is your answer to me," said he, bitterly. "When the right man puts the question (and he is not far off) you will tell another tale. You take me for a fool, and you mock me; you are not the lass to die an old maid: and men are not the fools to let you. With faces like yours, the new servant comes before[Pg 649] the old one is gone. Well, I have got my answer. County Cumberland, you are no place for me! The ways and the fields we two have ridden together,—oh, how could I bear their sight without my dear? Why, what a poor-spirited fool I am to stay and whine! Come, Mistress, your lover waits you there, and your discarded servant knows good-breeding: he leaves the country not to spoil your sport."

Catharine panted heavily.

"Well, Sir," said she, "then it is your doing, not mine. Will you not even shake hands with me, Griffith?"

"I were a brute else," sighed the jealous one, with a sudden revulsion of feeling. "I have spent the happiest hours of my life beside you. If I loved thee less, I had never left thee."

He clung a little while to her hands, more like a drowning man than anything else, then let them go, and suddenly shook his clenched fist in the direction of George Neville, and cried out with a savage yell,—

"My curse on him that parts us twain! And you, Kate, may God bless you single, and curse you married! and that is my last word in Cumberland."

"Amen!" said Catharine, resignedly.

And even with this they wheeled their horses apart, and rode away from each other: she very pale, but erect with wounded pride; he reeling in his saddle like a drunken man.

And so Griffith Gaunt, stung mad by jealousy, affronted his sweetheart, the proudest girl in Cumberland, and, yielding to his foible, fled from his pain.

Our foibles are our manias.

Miss Peyton was shocked and grieved; but she was also affronted and wounded. Now anger seems to have some fine buoyant quality, which makes it rise and come uppermost in an agitated mind. She rode proudly into the court-yard of her father's house, and would not look once behind to see the last of her perverse lover.

The old groom, Joe, who had taught her to ride when she was six years old, saw her coming, and hobbled out to hold her horse, while she alighted.

"Mistress Kate," said he, "have you seen Master Griffith Gaunt anywheres?"

The young lady colored at this question.

"Why?" said she.

"Why?" repeated old Joe, a little contemptuously. "Why, where have you been not to know the country is out after un? First comed Jock Dennet, with his horse all in a lather, to say old Mr. Charlton was took ill, and had asked for Master Griffith. I told him to go to Dogmore Copse: 'Our Kate is a-hunting to-day,' says I; 'and your Griffith, he is sure not to be far from her gelding's tail'; a sticks in his spurs and away a goes. What, ha'n't you seen Jock, neither?"

"No, no," replied Miss Peyton, impatiently. "What, is there anything the matter?"

"The matter, quo' she! Why, Jock hadn't been gone an hour when in rides the new footman all in a lather, and brings a letter for Master Griffith from the old gentleman's housekeeper. 'You leave the letter with me, in case,' says I, and I sends him a-field after t' other. Here be the letter."

He took off his cap and produced the letter.

Catharine started at the sight of it.

"Alack!" said she, "this is a heavy day. Look, Joe; sealed with black. Poor Cousin Charlton! I doubt he is no more."

Joe shook his head expressively, and told her the butcher had come from that part not ten minutes ago, with word that the blinds were all down at Bolton Hall.

Poor human nature! A gleam of joy shot through Catharine's heart; this sad news would compel Griffith to stay at home and bury his benefactor; and that delay would give him time to reflect; and, somehow or other, she felt sure it would end in his not going at all.

But these thoughts had no sooner passed through her than she was ashamed of them and of herself. What! welcome[Pg 650] that poor old man's death because it would keep her cross-grained lover at home? Her cheeks burned with shame; and, with a superfluous exercise of self-defence, she retired from Old Joe, lest he should divine what was passing in her mind.

But she was so wrapt in thought that she carried the letter away with her unconsciously.

As she passed through the hall, she heard George Neville and her father in animated conversation. She mounted the stairs softly, and went into a little boudoir of her own on the first floor, and sat down. The house stood high, and there was a very expansive and beautiful view of the country from this window. She sat down by it and drooped, and looked wistfully through the window, and thought of the past, and fell into a sad reverie. Pity began to soften her pride and anger, and presently two gentle tears dimmed her glorious eyes a moment, then stole down her delicate cheeks.

While she sat thus lost in the past, jovial voices and creaking boots broke suddenly upon her ear, and came up the stairs; they jarred upon her; so she cast one last glance out of the window, and rose to get out of their way, if possible. But it was too late; a heavy step came to the door, and a ruddy, Port-drinking face peeped in. It was her father.

"See-ho!" roared the jovial Squire. "I've found the hare on her form; bide thou outside a moment."

And he entered the room; but he had no sooner closed the door than his whole manner changed from loud and jovial to agitated and subdued.

"Kate, my girl," said he, piteously, "I have been a bad father to thee. I have spent all the money that should have been thine; thy poor father can scarce look thee in the face. So now I bring thee a good husband; be a good child now, and a dutiful. Neville's Court is his, and Neville's Cross will be, by the entail; and so will the baronetcy. I shall see my girl Lady Neville."

"Never, papa, never!" cried Kate.

"Hush! hush!" said the Squire, and put up his hand to her in great agitation and alarm; "hush, or he will hear ye. Kate," he whispered, "are you mad? Little I thought, when he asked to see me, it was to offer marriage. Be a good girl now; don't you quarrel with good luck. You are not fit to be poor; and you have made enemies: do but think how they will flout you when I die, and Bill's jade of a wife puts you to the door, as she will. And now you can triumph over them all, my Lady Neville,—and make your poor father happy, my Lady Neville. Enough said, for I promised you; so don't go and make a fool of me, and yourself into the bargain. And—and—a word in your ear: he hath lent me a hundred pounds."

At this climax, the father hung his head; the daughter winced and moaned out,—

"Papa, how could you?"

Mr. Peyton had gradually descended to that intermediate stage of degradation, when the substance of dignity is all gone, but its shadow, shame, remains. He stamped impatiently on the ground, and cut his humiliation short by rushing out of the room.

"Here, try your own luck, youngster," he cried at the door. "She knows my mind."

He trampled down the stairs, and young George Neville knocked respectfully at the door, though it was half open, and came in with youth's light foot, and a handsome face flushed into beauty by love and hope.

Miss Peyton's eye just swept him as he entered, and with the same movement she turned away her fair head and blushing cheek towards the window; yet—must I own it?—she quietly moulded the letter that lay in her lap, so that the address was no longer visible to the new-comer.

(Small secrecy, verging on deceit, you are bred in woman's bones!)

This blushing and averted cheek is one of those equivocal receptions that have puzzled many a sensible man. It is a sign of coy love; it is a sign of[Pg 651] gentle aversion; our mode of interpreting it is simple and judicious: whichever it happens to be, we go and take it for the other.

The brisk, bold wooer that now engaged Kate Peyton was not the man to be dashed by a woman's coyness. Handsome, daring, good-humored, and vain, he had everything in his favor but his novelty.

Look at Kate! her eye lingers wistfully on that disconsolate horseman whose every step takes him farther from her; but George has her ear, and draws closer and closer to it, and pours love's mellow murmurs into it.

He told her he had made the grand tour, and seen the beauties of every land, but none like her; other ladies had certainly pleased his eye for a moment, but she alone had conquered his heart. He said many charming things to her, such as Griffith Gaunt had never said. Amongst the rest, he assured her the beauty of her person would not alone have fascinated him so deeply; but he had seen the beauty of her mind in those eyes of hers, that seemed not eyes, but souls; and begging her pardon for his presumption, he aspired to wed her mind.

Such ideas had often risen in Kate's own mind; but to hear them from a man was new. She looked askant through the window at the lessening Griffith, and thought "how the grand tour improves a man!" and said, as coldly as she could,—

"I esteem you, Sir, and cannot but be flattered by sentiments so superior to those I am used to hear; but let this go no farther. I shall never marry now."

Instead of being angry at this, or telling her she wanted to marry somebody else, as the injudicious Griffith had done, young Neville had the address to treat it as an excellent jest, and drew such comical pictures of all the old maids in the neighborhood that she could not help smiling.

But the moment she smiled, the inflammable George made hot love to her again. Then she besought him to leave her, piteously. Then he said, cheerfully, he would leave her as soon as ever she had promised to be his. At that she turned sullen and haughty, and looked through the window and took no notice of him whatever. Then, instead of being discouraged or mortified, he showed imperturbable confidence and good-humor, and begged archly to know what interesting object was in sight from that window. On this she blushed and withdrew her eyes from the window, and so they met his. On that he threw himself on his knees, (custom of the day,) and wooed her with such a burst of passionate and tearful eloquence that she began to pity him, and said, lifting her lovely eyes,—

"Alas! I was born to make all those I esteem unhappy!" and she sighed deeply.

"Not a bit of it," said he; "you were born, like the sun, to bless all you shine upon. Sweet Mistress Kate, I love you as these country boors can never be taught to love. I lay my heart, my name, my substance, at your feet; you shall not be loved,—you shall be worshipped. Ah! turn those eyes, brimful of soul, on me again, and let me try and read in them that one day, no matter how distant, the delight of my eyes, the joy of all my senses, the pride of Cumberland, the pearl of England, the flower of womankind, the rival of the angels, the darling of George Neville's heart, will be George Neville's wife."

Fire and water were in his eyes, passion in every tone; his manly hand grasped hers and trembled, and drew her gently towards him.

Her bosom heaved; his passionate male voice and touch electrified her, and made her flutter.

"Spare me this pain," she faltered; and she looked through the window and thought, "Poor Griffith was right, after all, and I was wrong. He had cause for jealousy, and CAUSE FOR FEAR."

And then she pitied him who panted at her side, and then she was sorry for him who rode away disconsolate, still lessening to her eye; and what with[Pg 652] this conflict and the emotion her quarrel with Griffith had already caused her, she leaned her head back against the shutter, and began to sob low, but almost hysterically.

Now Mr. George Neville was neither a fool nor a novice, if he had never been downright in love before, (which I crave permission to doubt,) he had gone far enough on that road to make one Italian lady, two French, one Austrian, and one Creole, in love with him; and each of these love-affairs had given him fresh insight into the ways of woman. Enlightened by so many bitter-sweet experiences, he saw at once that there was something more going on inside Kate's heaving bosom than he could have caused by offering her his hand. He rose from his knees and leaned against the opposite shutter, and fixed his eyes a little sadly, but very observantly, on her, as she leaned back against the shutter, sobbing low, but hysterically, and quivering all over.

"There's some other man at the bottom of this," thought George Neville.

"Mistress Kate," said he, gently, "I do not come here to make you weep. I love you like a gentleman. If you love another, take courage, tell me so, and don't let your father constrain your inclinations. Dearly as I love you, I would not wed your person, and your heart another's: that would be too cruel to you, and" (drawing himself up with sudden majesty) "too unjust to myself."

Kate looked up at him through her tears, and admired this man, who could love ardently, yet be proud and just. And if this appeal to her candor had been made yesterday, she would have said, frankly, "There is one I—esteem." But, since the quarrel, she would not own to herself, far less to another, that she loved a man who had turned his back upon her. So she parried.

"There is no one I love enough to wed," said she. "I am a cold-hearted girl, born to give pain to my betters. But I shall do something desperate to end all this."

"All what?" said he, keenly.

"The whole thing: my unprofitable life."

"Mistress Kate," said Neville, "I asked you, was there another man. If you had answered me, 'In truth there is, but he is poor and my father is averse or the like,' then I would have secretly sought that man, and, as I am very rich, you should have been happy."

"Oh, Mr. Neville, that is very generous, but how meanly you must think of me!"

"And what a bungler you must think me! I tell you, you should never have known. But let that pass; you have answered my question; and you say there is no man you love. Then I say you shall be Dame Neville."

"What, whether I will or no?"

"Yes; whether you think you will or no."

Catharine turned her dreamy eyes on him.

"You have had a good master. Why did you not come to me sooner?"

She was thinking more of him than of herself, and, in fact, paying too little heed to her words. But she had no sooner uttered this inadvertent speech than she felt she had said too much. She blushed rosy red, and hid her face in her hands in the most charming confusion.

"Sweetest, it is not an hour too late, as you do not love another," was stout George Neville's reply.

But nevertheless the cunning rogue thought it safest to temporize, and put his coy mistress off her guard. So he ceased to alarm her by pressing the question of marriage, but seduced her into a charming talk, where the topics were not so personal, and only the tones of his voice and the glances of his expressive eyes were caressing. He was on his mettle to please her by hook or by crook, and was delightful, irresistible. He set her at ease, and she began to listen more, and even to smile faintly, and to look through the window a little less perseveringly.

Suddenly the spell was broken for a while.[Pg 653]

And by whom?

By the other.

Ay, you may well stare. It sounds strange, but it is true, that the poor forlorn horseman, hanging like a broken man, as he was, over his tired horse, and wending his solitary way from her he loved, and resigning the field, like a goose, to the very rival he feared, did yet (like the retiring Parthian) shoot an arrow right into that pretty boudoir and hit both his sweetheart and his rival,—hit them hard enough to spoil their sport, and make a little mischief between them—for that afternoon, at all events.

The arrow came into the room after this fashion.

Kate was sitting in a very feminine attitude. When a man wants to look in any direction, he turns his body and his eye the same way, and does it; but women love to cast oblique regards; and this their instinct is a fruitful source of their graceful and characteristic postures.

Kate Peyton was at this moment a statue of her sex. Her fair head leaned gently back against the corner of the window-shutter; her pretty feet and fair person in general were opposite George Neville, who sat facing the window, but in the middle of the room; her arms, half pendent, half extended, went listlessly aslant her, and somewhat to the right of her knees, yet, by an exquisite turn of the neck, her gray eyes contrived to be looking dreamily out of the window to her left. Still in this figure, that pointed one way and looked another, there was no distortion; all was easy, and full of that subtile grace we artists call repose.

But suddenly she dissolved this feminine attitude, rose to her feet, and interrupted her wooer civilly.

"Excuse me," said she, "but can you tell me which way that road on the hill leads to?"

Her companion stared a little at so sudden a turn in the conversation, but replied by asking her, with perfect good-humor, what road she meant.

"The one that gentleman on horseback has just taken. Surely," she continued, "that road does not take to Bolton Hall."

"Certainly not," said George, following the direction of her finger. "Bolton lies to the right. That road takes to the sea-coast by Otterbury and Stanhope."

"I thought so," said Kate. "How unfortunate! He cannot know; but, indeed, how should he?"

"Who cannot know? and what? You speak in riddles, Mistress. And how pale you are! Are you ill?"

"No, not ill, Sir," faltered Kate; "but you see me much discomposed. My cousin Charlton died this day; and the news met me at the very door." She could say no more.

Mr. Neville, on hearing this news, began to make many excuses for having inadvertently intruded himself upon her on such a day; but, in the midst of his apologies, she suddenly looked him full in the face, and said, with nervous abruptness,—

"You talk like a preux chevalier. I wonder whether you would ride five or six miles to do me a service."

"Ay, a thousand!" said the young man, glowing with pleasure. "What is to do?"

Kate pointed through the window.

"You see that gentleman on horseback. Well, I happen to know that he is leaving the country; he thinks that he—that I—that Mr. Charlton has many years to live. He must be told Mr. Charlton is dead, and his presence is required at Bolton Hall. I should like somebody to gallop after him, and give him this letter; but my own horse is tired, and I am tired; and, to be frank, there is a little coolness between the gentleman himself and me. Oh, I wish him no ill, but really I am not upon terms—I do not feel complaisant enough to carry a letter after him; yet I do feel that he must have it. Do not you think it would be malicious and unworthy in me to keep the news from him, when I know it is so?"

Young Neville smiled.

"Nay, Mistress, why so many words?[Pg 654] Give me your letter, and I will soon overtake the gentleman: he seems in no great hurry."

Kate thanked him, and made a polite apology for giving him so much trouble, and handed him the letter. When it came to that, she held it out to him rather irresolutely; but he took it promptly, and bowed low, after the fashion of the day. She curtsied; he marched off with alacrity. She sat down again, and put her head in her hand to think it all over, and a chill thought ran through her. Was her conduct wise? What would Griffith think at her employing his rival? Would he not infer Neville had entered her service in more senses than one? Perhaps he would throw the letter in the dirt in a rage, and never read it.

Steps came rapidly, the door opened, and there was George Neville again, but not the same George Neville that went out but thirty seconds before. He stood in the door looking very black, and with a sardonic smile on his lips.

"An excellent jest, Mistress!" said he, ironically.

"Why, what is the matter?" said the lady, stoutly; but her red cheeks belied her assumption of innocence.

"Oh, not much," said George, with a bitter sneer. "It is an old story; only I thought you were nobler than the rest of your sex. This letter is to Mr. Griffith Gaunt."

"Well, Sir!" said Kate, with a face of serene and candid innocence.

"And Mr. Griffith Gaunt is a suitor of yours."

"Say, was. He is so no longer. He and I are out. But for that, think you I had even listened to—what you have been saying to me this ever so long?"

"Oh, that alters the case," said George. "But stay!" and he knitted his brows, and reflected.

Up to a moment ago, the loftiness of Catharine Peyton's demeanor, and the celestial something in her soul-like, dreamy eyes, had convinced him she was a creature free from the small dishonesty and lubricity he had noted in so many women otherwise amiable and good. But this business of the letter had shaken the illusion.

"Stay!" said he, stiffly, "You say Mr. Gaunt and you are out?"

Catharine assented by a movement of her fair head.

"And he is leaving the country. Perhaps this letter is to keep him from leaving the country."

"Only until he has buried his benefactor," murmured Kate, in deprecating accents.

George wore a bitter sneer at this.

"Mistress Kate," said he, after a significant pause, "do you read Molière?"

She bridled a little, and would not reply. She knew Molière quite well enough not to want his wit levelled at her head.

"Do you admire the character of Célimène?"

No reply.

"You do not. How can you? She was too much your inferior. She never sent one of her lovers with a letter to the other to stop his flight. Well, you may eclipse Célimène; but permit me to remind you that I am George Neville, and not Georges Dandin."

Miss Peyton rose from her seat with eyes that literally flashed fire; and—the horrible truth must be told—her first wild impulse was to reply to all this Molière with one cut of her little riding-whip. But she had a swift mind, and two reflections entered it together: first, that this would be unlike a gentlewoman; secondly, that, if she whipped Mr. Neville, however inefficaciously, he would not lend her his piebald horse. So she took stronger measures; she just sank down again, and faltered,—

"I do not understand these bitter words. I have no lover at all; I never will have one again. But it is hard to think I cannot make a friend nor keep a friend,"—and so lifted up her hands, and began to cry piteously.

Then the stout George was taken aback, and made to think himself a ruffian.

"Nay, do not weep so, Mistress Kate," said he, hurriedly. "Come, take courage. I am not jealous of Mr. Gaunt,—a man[Pg 655] that hath been two years dangling after you, and could not win you. I look but to my own self-respect in the matter. I know your sex better than you know yourselves. Were I to carry that letter, you would thank me now, but by-and-by despise me. Now, as I mean you to be my wife, I will not risk your contempt. Why not take my horse, put whom you like on him, and so convey the letter to Mr. Gaunt?"

Now this was all the fair mourner wanted; so she said,—

"No, no, she would not be beholden to him for anything; he had spoken harshly to her, and misjudged her cruelly, cruelly,—oh! oh! oh!"

Then he implored her to grant him this small favor; then she cleared up, and said, Well, sooner than bear malice, she would. He thanked her for granting him that favor. She went off with the letter, saying,—

"I will be back anon."

But once she got clear, she opened the door again, and peeped in at him gayly, and said she,—

"Why not ask me who wrote the letter, before you compared me to that French coquette?"—and, with this, made him an arch curtsy, and tripped away.

Mr. George Neville opened his eyes with astonishment. This arch question, and Kate's manner of putting it, convinced him the obnoxious missive was not a love-letter at all. He was sorry now, and vexed with himself, for having called her a coquette, and made her cry. After all, what was the mighty favor she had asked of him? To carry a sealed letter from somebody or other to a person who, to be sure, had been her lover, but was so no longer,—a simple act of charity and civility; and he had refused it in injurious terms.

He was glad he had lent his horse, and almost sorry he had not taken the letter himself.

To these chivalrous self-reproaches succeeded an uneasy feeling that perhaps the lady might retaliate somehow. It struck him, on reflection, that the arch query she had let fly at him was accompanied with a certain sparkle of the laughing eye, such as ere now had, in his experience, preceded a stroke of the feminine claw.

As he walked up and down, uneasy, awaiting the fair one's return, her father came up, and asked him to dine and sleep. What made the invitation more welcome was, that it in reality came from Kate.

"She tells me she has borrowed your horse," said the Squire; "so, says she, I am bound to take care of you till day-light; and, indeed, our ways are perilous at night."

"She is an angel!" cried the lover, all his ardor revived by this unexpected trait. "My horse, my house, my hand, and my heart are all at her service, by night and day."

Mr. Peyton, to wile away the time before dinner, invited him to walk out and see—a hog, deadly fat, as times went. But Neville denied himself that satisfaction, on the plea that he had his orders to await Miss Peyton's return where he was. The Squire was amused at his excessive docility, and winked, as much as to say, "I have been once upon a time in your plight," and so went and gloried in his hog alone.

The lover fell into a delicious reverie. He enjoyed, by anticipation, the novel pleasure of an evening passed all alone with this charming girl. The father, being friendly to his suit, would go to sleep after dinner; and then, by the subdued light of a wood-fire, he would murmur his love into that sweet ear for hours, until the averted head should come round by degrees, and the delicious lips yield a coy assent. He resolved the night should not close till he had surprised, overpowered, and secured his lovely bride.

These soft meditations reconciled him for a while to the prolonged absence of their object.

In the midst of them, he happened to glance through the window; and he saw a sight that took his very breath away, and rooted him in amazement to the spot. About a mile from the house, a lady in a scarlet habit was galloping[Pg 656] across country as the crow flies. Hedge, ditch, or brook, nothing stopped her an instant; and as for the pace,—

It was Kate Peyton on his piebald horse.

Griffith Gaunt, unknown to himself, had lost temper as well as heart before he took the desperate step of leaving the country. Now his temper was naturally good; and ere he had ridden two miles, he recovered it. To his cost; for the sustaining force of anger being gone, he was alone with his grief. He drew the rein half mechanically, and from a spirited canter declined to a walk.

And the slower he went, the chillier grew his heart, till it lay half ice, half lead, in his bosom.

Parted! oh, word pregnant with misery!

Never to see those heavenly eyes again, nor hear that silver voice! Never again to watch that peerless form walk the minuet; nor see it lift the gray horse over a fence with the grace and spirit that seemed inseparable from it!

Desolation streamed over him at the thought. And next his forlorn mind began to cling even to the inanimate objects that were dotted about the place which held her. He passed a little farm-house into which Kate and he had once been driven by a storm, and had sat together by the kitchen fire; and the farmer's wife had smiled on them for sweethearts, and made them drink rum and milk and stay till the sun was fairly out.

"Ah! good-bye, little farm!" he sighed; "when shall I ever see you again?"

He passed a brook where they had often stopped together and given their panting horses just a mouthful after a run with the harriers.

"Good-bye, little brook!" said he; "you will ripple on as before, and warble as you go; but I shall never drink at your water more, nor hear your pleasant murmur with her I love."

He sighed and crept away, still making for the sea.

In the icy depression of his heart his body and his senses were half paralyzed, and none would have known the accomplished huntsman in this broken man, who hung anyhow over his mare's neck and went to and fro in the saddle.

When he had gone about five miles, he came to the crest of a hill; he remembered, that, once past that brow, he could see Peyton Hall no more. He turned slowly and cast a sorrowful look at it.

It was winter, but the afternoon sun had come out bright. The horizontal beams struck full upon the house, and all the western panes shone like burnished gold. Her very abode, how glorious it looked! And he was to see it no more.

He gazed and gazed at the bright house till love and sorrow dimmed his eyes, and he could see the beloved place no more. Then his dogged will prevailed and carried him away towards the sea, but crying like a woman now, and hanging all dislocated over his horse's mane.

Now about half a mile farther on, as he crept along on a vile and narrow road, all woebegone and broken, he heard a mighty scurry of horse's feet in the field to his left; he looked languidly up; and the first thing he saw was a great piebald horse's head and neck in the act of rising in the air, and doubling his fore-legs under him, to leap the low hedge a yard or two in front of him.

He did leap, and landed just in front of Griffith; his rider curbed him so keenly that he went back almost on his haunches, and then stood motionless all across the road, with quivering tail. A lady in a scarlet riding-habit and purple cap sat him as if he had been a throne instead of a horse, and, without moving her body, turned her head swift as a snake, and fixed her great gray eyes full and searching upon Griffith Gaunt.

This active, energetic, and in every way remarkable man, who was not only the originator, proprietor, and purveyor, but the editor,—the actual and only editor,—of "Blackwood's Magazine," up to the day of his death, in 1834, has never been properly understood nor appreciated, either abroad or at home, owing to circumstances the public are unacquainted with.

While exercising despotic power, in all that concerned the management of that bold and saucy and at times unprincipled work, in all that concerned the management or the contributors, and never yielding even to "Old Christopher" himself, who passed for the editor, where any serious question sprang up, he was so careful to keep out of sight himself, and to thrust that old gentleman forward, upon all occasions,—a sort of myth, at the best,—a shadowy, mysterious personage, who deceived nobody, and whom all were glad enough to take on trust, well knowing that Professor Wilson was behind the mask,—that, up to this day, William Blackwood, the little, tough, wiry Scotch bookseller, with a big heart, and a pericardium of net-work,—interwoven steel springs,—has been regarded as the publisher and proprietor only, and Professor Wilson as the editor, and one who would suffer no interference with his prerogative, and "bear no brother near the throne."

To bring about this belief, Blackwood spared no expense of indirect assertion, and no outlay of incidental evidence. Never faltering in his first plan, and never foregoing an opportunity of strengthening the public delusion, what cared he for the reputation of editorship, so long as the great mystery paid? Walter Scott had already shown how profitably and safely such a game might be played, year after year, in the midst of the enemies' camp; and Blackwood was just the man to profit by such experience.

In the Life of Professor Wilson, by his daughter, Mrs. Gordon, edited here by Professor Mackenzie, there might be found enough to disabuse the public upon this point, if it were not read by the lamplight—or twilight—of long-cherished opinions.

But as Blackwood, the shrewd, sharp, wary Scotchman, always talked about "our worthy friend Christopher" as a real, and not a mythological personage,—as if, in short, he were himself and nobody else,—and never of Wilson but as one of the contributors, or as the author of "Margaret Lyndsay" or "The Isle of Palms," and then with a look or a smile which he never explained, and which nobody out of the charmed circle ever understood, no wonder the delusion was kept up to the last.

"All I can say," he once wrote me, while negotiating for more grist,—"all I can say is, that whatever is good in itself we are always happy to receive; the only difficulty is, that our worthy friend Christopher is a very absolute person, and therefore always judges for himself with regard to everything that is offered." Now this—considering that he himself, William Blackwood, was Christopher North, in spirit, if not in substance, and that he himself, and not Wilson, was the autocrat from whose judgment there was no appeal—might pass anywhere, I think, for one of the happiest examples of persevering, impudent mystification ever hazarded by a respectable man, while writing confidentially to another, and quite of a piece with the celebrated Chaldee manuscript.

And now for my acquaintance with the man himself. I was living in Baltimore. I had given up my editorships. I had forsworn poetry and story-telling, (on paper,) and had not only entered upon the profession of the law with encouraging success, but had begun to settle upon my lees.[Pg 661]

One day, while dining with my friend Henry Robinson, who introduced gas into Boston, after a series of disastrous experiments in Baltimore, and the conversation happening to turn upon that subject, we wandered off into the state of English opinions generally. He was an Englishman by birth and early education, though his heart was American to the core. Something was said about the literature of the day, and the question was asked,—"Who reads an American book?" I blazed out, of course, and, after denouncing the "Edinburgh Review," where the impudent question was first broached, accompanied by the suggestion, that, so long as we could "import our literature in bales and hogsheads," we had better not try to manufacture for ourselves, I made up my mind on the spot, and within the next following half-hour at furthest, to carry the war into Africa.

Mr. Walsh,—"Robert Walsh, Junior, Esquire,"—the "American Gentleman," as he called himself in the title-page of his Dictionary,—had acknowledged, while undertaking our vindication, that our American Parnassus was barren, or fruitful only in weeds; and by common consent my countrymen had taken for the highest praise throughout the land what I regarded as at best a humiliating admission from our friends over sea. They had acknowledged, and we were base enough to feel flattered by the acknowledgment, that, although we could not even hope to write English, and were wellnigh destitute of invention, having no materials to work with, and little or no aptitude for anything but the manufacture of wooden nutmegs, horn gun-flints, and cuckoo-clocks, and being always too busy for anything better than dicker and truck in a small way,—the haberdashery of nations,—yet, after all, it might be said of us that we were capital imitators, or thieves and counterfeiters, so that our Brockden Brown was at least the American Godwin,—our Cooper, the American Scott,—our Irving, just flowering in the "Sketch-Book," the American Goldsmith or Addison,—and our Sigourney, the American Hemans.

That my blood boiled in my veins, whenever I thought of this, I must acknowledge; and within three weeks, I believe, I was on my way to London, with a novel in the rough, which, after undergoing many transformations, appeared in that city as "Brother Jonathan,"—the manuscript of "Otho, a Tragedy," wholly recast and rewritten, with "exit omnes," and other monstrous Latin blunders corrected, and, on the whole, very much as it afterwards appeared in "The Yankee,"—and heaps of letters, which I could not well afford to deliver, and therefore threw into the fire: leaving my law business to take care of itself, somewhat after the fashion of that Revolutionary volunteer, "Old Put," who, when he heard the sound of a trumpet and knew the lists were opened, left his plough in the furrow, and the cattle standing in the field. My law-library, and the building I occupied, I passed over to the care of a young man of great promise, just entering the profession, who not only burned up my supply of wood for the year, but failed to pay the rent, and then took the liberty of dying suddenly, poor fellow! without a word of notice to my landlord: so that I was fairly adrift.

On arriving in London, I took lodgings in Warwick Street, Pall Mall, introduced to the landlady by Leslie the painter, and occupying the very chambers where Washington Irving was delivered of the "Sketch-Book": my windows on the first floor looking out on the back entrance of Carlton House, by which the Princess Charlotte had escaped not long before, when she ran away from her father, as my landlady took care to inform me; adding, that, from the very window where we stood, she had seen the little madcap get into the carriage—a common hack, by the way—and go off at full speed.

I lost no time in looking about me, and preparing for a literary campaign, where I might forage upon the enemy, beat up his quarters when I chose,[Pg 662] and, if possible, get possession of a battery or so, and turn the guns upon his camp.

Being pretty well acquainted with the characteristics of all the monthlies and quarterlies, I was not long in determining that "Blackwood" was my point d'appui. The "Old Monthly" was dead asleep, and smouldering in white ashes; the "New Monthly," with Campbell for editor, was unfitted for the job I had in view; the "London," though clever and saucy and stinging, wanted manliness and nerve, and would be sure to fail me at a pinch, now that John Scott was disposed of. And as for the quarterlies, even supposing I could secure a place and keep it, they were all slow coaches, and much too dignified and stately, as they lumbered along the smooth, level turnpikes they were built for, to allow of any dashing or skirmishing from the windows. Even the "Westminster" was untrustworthy, as I afterwards found to my cost.

And so I settled down upon "Blackwood," the cleverest and spitefullest of the whole, with Lockhart, "the Scorpion," and Wilson, "the Leopard," for mischief-makers, and "Ebony" for the whipper-in, and "Christopher North" "in golden panoply complete" for collaborateur, a puzzle and a problem to the last. Before I slept, I believe, certainly within a few hours, I wrote a sketch of our five American Presidents, and of the five presidential candidates then actually in the field, and sent it off to Edinburgh with a letter, not for the publisher, not for Blackwood, but for the Editor, saying that I had adopted the name of "Carter Holmes," and writing as a traveller, pretty well acquainted with the United States and with the people thereof. This mask I wore, not with a view to escape responsibility, for I was ready to answer for all I said, but to baffle the curious and the inquisitive. Had I come out boldly as a native American, I knew there was no chance for me in that, or in any other leading British journal.

After a few days, I received the following in reply from Blackwood himself, the Editor, which I give at length.

"April 20, 1824.

"On my return from London a few days ago," says he, "I had the pleasure of receiving yours of the 7th March,—April, I suppose, as it only arrived here on the 10th current.

"I am very sorry that there was not room for your spirited and amusing sketches in this number; but they will appear in our next.

"You are exactly the correspondent that we want, and I hope you will continue to favor us with your communications, and you may depend upon being liberally treated. I do not wish to say much about terms, as I have a perfect horror at the manufacturing system of gentlemen who do articles for periodicals at so much per sheet. I feel confident that you are none of these, but one who, like the friends who have supported my Magazine, writes upon subjects which he takes an interest in, and therefore handles them con amore. It is this system of piece-work which has made most periodicals such commonplace affairs; and it is by keeping free of it that 'Maga' will preserve her name and fame.

"Meantime, I am perfectly sensible that the laborer is worthy of his hire, and that no gentleman need refuse the remuneration he is entitled to. It gives me great pleasure, therefore, to send an honorarium to all my contributors. I may also mention to you that this varies from seven to ten guineas, or perhaps more, per sheet, according to the nature of the articles.

"By way of arles, (Anglicé, earnest,) I annex a draft on Mr. Cadell for five guineas to account.

"With regard to your name, you will do just as you feel most convenient and agreeable. All I shall say is, that whatever is confided to me I keep sacredly to myself.

"I am, Sir,

"Your most obedient servant,

"W. Blackwood."

"Five guineas!" said I to myself,—twenty-five dollars cash, for a paper I had flung off at a single sitting, and which at home would have been thought well paid for with a "Much obliged," or, at most, with a five-dollar bill,—even the great "North American Review" then paying, where it paid at all, only a dollar a page in "that day of small things"; and to work I went forthwith, preparing another article upon another American subject, determined to be in season, and not allow the blaze I had lighted up to go out for want of kindling-stuff. The article, I may say here, created quite a sensation, and was copied into the Continental journals and papers, and even reappeared in the great "European Review," then just established at London, Paris, and Vienna, under the editorship of Alexander Walker, a Scotchman, who began his literary career by undertaking to supply the deficiencies of D'Alembert, while he wrote me about a jeux d'esprit, with all seriousness.

One curious little incident occurs to me here in connection with the signature I had adopted. Perhaps the Spiritualists may be able to account for it. Having finished my second article, and folded it up, and directed it, as before, to the "Editor," and being about to affix the seal,—for wafers were not used by decent people in England, and self-sealing envelopes were unheard of in that day,—I went below, where I heard voices in conversation that I knew, to borrow a seal, not wishing to use mine, which not only bore an eagle's head for a crest, but my initials and the striped shield of my country.

There were present Humphreys, the engraver,—Lady Lilicraft, one of Washington Irving's lay figures, and the cast-off chère amie of an English lordling,—Peter Powell, of whom a word or two hereafter,—Chester Harding,—and the celebrated John Dunn Hunter, whose portrait Harding had just under way.

When I had stated my request, two or three hands, with two or three seals, were instantly reached forth. I took the nearest, and was not a little surprised, on looking at the impression, to find the very initials I needed, in old English. The seal belonged to Chester Harding; and as my nom de plume was "Carter Holmes," the "C. H." seemed quite providential. From that time forward, I continued to use the same seal whenever I found Harding within reach, until, one day, a still stranger "happening" occurred. I was in a hurry, and could not wait. Any seal would do, of course; and the mistress, pitying my perplexity, said there was a seal up-stairs somewhere which might serve my turn, if she could find it. After a short absence, she returned, and, handing me an old-fashioned affair, which I did not stop to look at, I made the impression, and was just about sending off the parcel, when my attention was attracted by the very same initials of "C. H.," as you live! Her husband's name was Charles Halloway, Harding was Chester Harding, and I was "Carter Holmes"!

One word now about another of Irving's associates and playmates,—Peter Powell, whom I often met with at Mrs. Halloway's. You will find him frequently mentioned by name in the "Life and Letters of Washington Irving," as a "fellow of infinite jest and most excellent fancy," and full of the strangest contrivances for "setting the table in a roar"; and more than once, though I do not now remember where, I have met with a grotesque shadow, under a fictitious name,—a sort of Santa Claus or Æsop at large,—either in the "Sketch-Book" or in the "Tales of a Traveller," which I saw at a glance, when I came to know the original, could be no other than Peter Powell himself.

But as Irving did not particularize, I must. Peter would personate a dancing bear; and with the help of a shaggy overcoat pulled up about his ears, and a pair of black kid gloves, he being a small man, hardly taller than a good-sized bear, when standing up with his knees bent, the representation was not only surprisingly faithful, but sometimes absolutely startling.[Pg 664]

He would serve you out with passages from a new opera, taking all the parts himself, either separately or together, and with feet, hands, and voice, a table, a chair, and a paper trumpet extemporized for the occasion from a sheet of music-paper, would almost persuade you that a rehearsal was going on at your elbow.

He would tie a couple of knots in his pocket-handkerchief, throw the rest of it over his hand so as to conceal the action, thrust his left forefinger into the lowest knot for a head, while the uppermost would go for a turban, spread out the middle finger and thumb, covered with the drapery, and make the figure bow and salaam, as if it were alive, to the unspeakable amazement of the little ones. Many years after this, I tried the same trick with the Aztec children, and drove the little monsters half crazy with delight.

He would imitate rooks in their noisiest flights, by putting on a pair of black gloves, and spreading the fingers, and cawing; and butterflies alighting on a flower, by pressing his two hands together where they join the wrist, closing the fingers with a fluttering motion, and moving them this way and that, until it was quite impossible to misunderstand the representation; and he would give you a sailor's hornpipe at the dinner-table, by striping two of his fingers with a pen, drawing a face on the back of his hand, with vest and waistband to explain the trousers, and set you screaming as he went through the steps and flourishes on a plate, with the greatest possible seriousness and propriety.

But enough. Let us now return to Blackwood. For my next paper he paid me ten guineas,—fifty dollars,—and, in reply to certain suggestions of mine, wrote as follows. I give this letter to show how much of a business man he was, and how well fitted for the duties of editorship.

"Edinburgh, 17 May, 1834.

"Dear Sir,—Yours of the 13th makes me feel very much ashamed at having so long delayed answering your two former favors. The truth is, that you have given me such a bill of fare of what you could furnish for our monthly entertainment, I felt it would be necessary to write you more at length than I had leisure for at the time I received your letter; and, like everything that is delayed at the proper moment, every day has presented excuses for procrastination.

"If I had the pleasure of knowing you, I might have been able, as you say, to have given you some hints as to subjects; but in present circumstances, all I have to say is, that whatever is good in itself we are always happy to receive, [&c., &c., as hereinbefore quoted in relation to "Christopher North."] I shall only add, that anything of yours he will be disposed to view with a favorable eye. As to the theatre, exhibitions, &c., the daily papers are so stuffed with notices of them, that even what is good has but a poor chance. However, I do not mean to say that these subjects should be excluded from your communications; all I mean is, that you should just write upon what you yourself feel a strong interest in.

"I would be happy to see your novel, ["Brother Jonathan,"] but it is now too late of thinking to publish at this season. If you will send it, addressed to me, to Mr. Cadell's, with a note, desiring it to be forwarded by first mail-coach, I will receive it quite safely; and I will, in the course of ten days after its reception, write you my sentiments with regard to it. No one shall see it; for in these matters I judge for myself. If you should go to the Continent, perhaps you could leave the manuscript in such a state that it could be printed in your absence.

"I am, dear Sir, yours truly,

"W. Blackwood."