The Project Gutenberg EBook of Adventures of Hans Sterk, by A.W. Drayson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Adventures of Hans Sterk

The South African Hunter and Pioneer

Author: A.W. Drayson

Illustrator: J.B. Zwecker

Release Date: May 27, 2010 [EBook #32559]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ADVENTURES OF HANS STERK ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain A.W. Drayson, R.A.

"Adventures of Hans Sterk"

Preface.

In the history of colonisation there is probably no example on record so extraordinary as that of the emigration from the colony of the Cape of Good Hope, in 1835, of nearly six thousand souls, who, without guides or any definite knowledge of where they were going or what obstacles they would encounter, yet placed their all in the lottery and journeyed into the wilderness.

The cause of this emigration was to avoid what the emigrants considered the oppression of the ruling Government, and the object was to found an independent nationality in the interior of Africa.

These emigrants, shortly after quitting the neighbourhood of the Cape colony, were attacked by the chief of a powerful tribe called the Matabili, into whose country they had trespassed. Severe battles, in which overwhelming numbers were brought against them, were fought by the emigrants, the general results being victory to the white man.

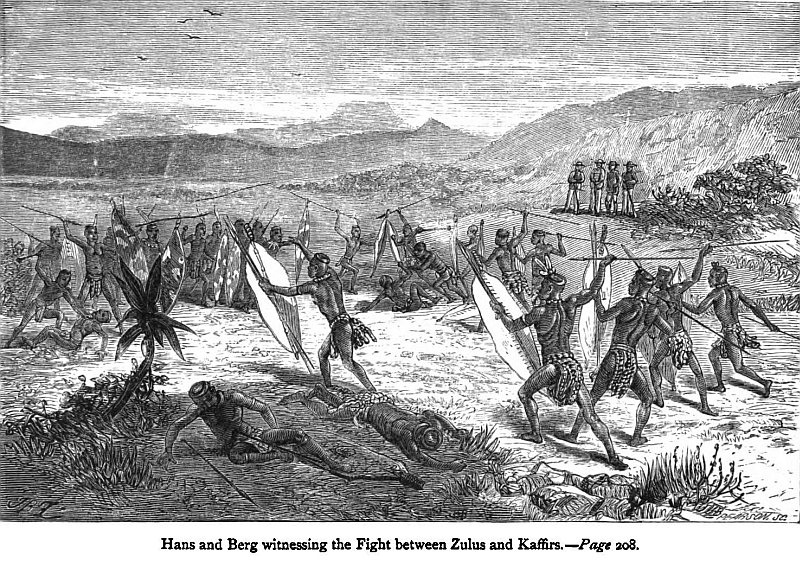

Not satisfied with the situation which these victories might have enabled them to secure, a party of the emigrants journeyed on towards the east, in order to obtain a better position near the present district of Natal. This party were shortly afterwards either treacherously massacred by a Zulu chief named Dingaan, or were compelled to fight for their lives and property during many months.

It is mainly amidst these scenes that the hero of the following tale passed—scenes which brought out many cases of individual courage, daring, and perseverance rarely equalled in any part of the world.

Around the bivouac fire, or in the ride over the far-spreading plains, or whilst resting after a successful hunting track in the tangled forest, the principal events of this tale have been recorded. From Zulu and Boer, English emigrant and Hottentot driver, we have had various accounts, each varying according to the peculiar views of the relater, but all agreeing as regards the main facts here blended and interwoven into a tale.

Chapter One.

Introduction to the Hunters—Death of the Lion—Discovery of the Elephants by Hans Sterk.

Near the outskirts of a far-extending African forest, and close beside some deep shady-pools, the only remnants of a once rapidly flowing river, were seen one glowing summer’s evening, shortly after sunset, a party of some ten men; bronzed workmen-like fellows they were too, their dress and equipment proclaiming them hunters of the first class. This party were reclining on the turf, smoking, or giving the finishing touch to their rifles and smooth-bore guns, which they had been engaged in cleaning. Among this party there were two black men, fine, stalwart-looking fellows, whose calm demeanour and bright steady gazing eyes, proclaimed them men of nerve and energy. One tiny yellow man, a Hottentot, was remarkable among the group on account of his smallness, as he stood scarcely more than five feet in height, whereas all his companions were tall heavy men. A fire was brightly blazing, and several small tin vessels on this fire were steaming as their contents hissed and bubbled. The white men who composed this party were Dutch South African Boers, who were making an excursion into the favourite feeding-grounds of the Elephant, in order to supply themselves with ivory, this valuable commodity being to them a source of considerable wealth.

“It will soon be very dark,” exclaimed Bernhard, one of the Boers, “and Hans will have difficulty in finding our lager; I will go on to the headland and shoot.”

“You may leave Sterk to take care of himself,” said Heinrich, another Boer, “for no man is less likely to lose himself than he is.”

“I will go and shoot at all events,” said Bernhard, “for it can do no harm; and though Hans is quick and keen, watchful and careful, he may for once be overtaken by a fog or the darkness, and he does not well know this country.”

With this excuse for his proceeding, the man called Bernhard grasped his large-bored gun, and ascended a krantz which overhung the resting-place of his party, when, having reached the summit, he placed the muzzle of his gun within a foot of the ground, and fired both barrels in quick succession. This is a common signal amongst African hunters, it being understood to mean, that the resting-place at night is where the double shot is fired from.

There being no reply to this double shot, Bernhard returned to his companions, and the whole party then commenced their evening meal.

“So your sweetheart did not reply to you, Bernhard,” said one of the Boers, “though you did speak so loudly.”

“Hans Sterk is my sworn friend, good and true,” replied Bernhard; “and no man speaks lightly of him before me.”

“Quite right, Bernhard, stand to your friends, and they will stand to you; and Hans is a good friend to all, and few of us have not been indebted to him for some good turn or other; but what is Tembili the Kaffir doing?”

At this remark, all eyes were directed towards one of the Kaffir men, who had risen to his feet, and stood grasping his musket and looking eagerly into the forest near, whilst his dark companion was gazing fixedly in the same direction. It was a fine sight to observe this bronzed son of the desert at home and on the watch, for he did seem at home amidst the scenes around him. After a minute’s intent watching, he raised his hand, and in a low whisper said, “Leuew, Tao,” (the Dutch and Matabili names for a lion). “Leuew!” exclaimed each Boer, as he seized his weapons, which were close at hand and stood ready for an emergency.

“Make up the fire, Piet,” said Heinrich: “let us illuminate the visitor.” And a mass of dried grass and sticks thrown on the fire caused a brilliant flame, which lighted up the branches and creepers of the ancient forest.

As the flame rose and the sticks crackled, a low grumbling growl came from the underwood in the forest, which at once indicated to the hunters that the Kaffir’s instincts had not misled him, but that a lion was crouching in the bush near.

“Fire a shot, Karl,” said one of the Dutchmen; “drive him away with fear; we must not let him remain near us.” And Karl, aiming among the brushwood, fired. Amidst the noise and echoes of the Boer’s musket, a loud savage roar was audible, as the lion, thus disturbed, moved sullenly away from what he had expected would have been a feast; whilst the hunters, hearing him retreat, proceeded without any alarm with their meal, the Kaffirs alone of the party occasionally stopping in their eating to listen, and to watch the neighbouring bush.

The sun had set about three hours, and the moon, a few days past the full, had risen; whilst the Boers, having finished their meal, were rolled up in their sheepskin carosses, and sleeping on the ground as calmly as though they were each in a comfortable bed. The Kaffirs, however, were still quietly but steadily eating, and conversing in a low tone, scarcely above a whisper.

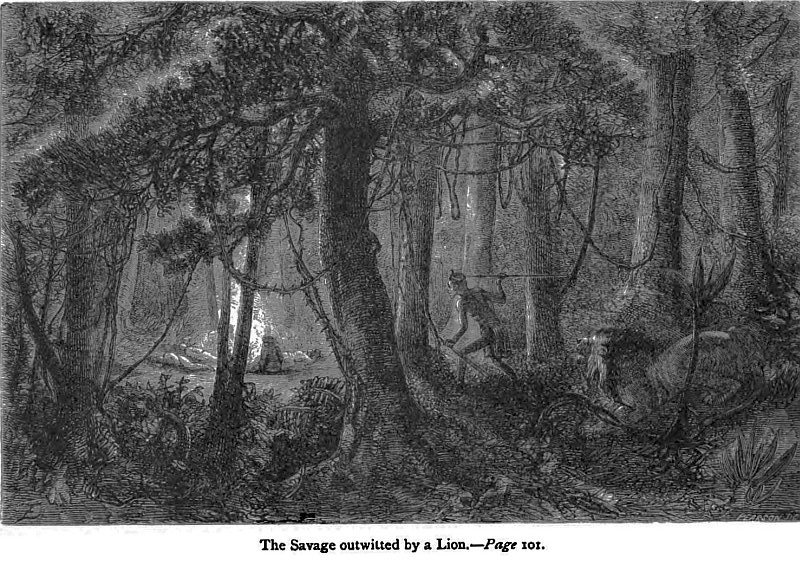

“The lion will not leave us during the night,” said the Kaffir called Tembili, “I will not sleep unless you watch, ’Nquane.”

“Yes, I will watch whilst you sleep, then you sleep whilst I watch,” replied the Kaffir addressed as ’Nquane. “We shall shoot elephants to-morrow, I think; and the young chief must be now close to them, that is why he does not return.”

“No: he would return to tell us if he could, I fear he must have lost himself,” replied Tembili.

“The ‘strong’ lose himself,” exclaimed ’Nquane, “no, as soon the vulture lose his way in the air, or the springbok on the plains, or the elephant in the forest, as the strong lose himself any where. He sees without eyes and hears without ears. Hark! is that the lion?”

Both Kaffirs listened attentively for some minutes, when ’Nquane said, “It is the lion moving up the krantz: he smells something or hears something; he must have tasted man’s flesh, to have stopped here so long close to us. What can he hear now? Ah, there is something up high in the bushes, a buck perhaps, the lion will soon feast on it, and that will be the better for us, as when his belly is full he will not want to eat you or me.”

Attentively as the Kaffirs watched the bushes, and listened for some sound indicative of the lion’s position, they yet could hear nothing; so quietly did the creature move, they had almost given up their attention to eating, when a sudden flash of light burst from the bushes on the top of the kloof, followed by a thundering roar which was succeeded by a silence, broken only at intervals by the distant echoes of the report of the gun, which at first had scarcely been audible in the midst of the lion’s roar, for such it proved to be.

As these sounds burst over the camp, each hunter started from his slumber, and stood waiting for some fresh indication of danger, or cause for action; for half a minute no man spoke, but then Bernhard exclaimed—

“That must have been Hans, he must have met the lion in the dark;” and, “Oh, Hans! Hans!” he shouted:

“Here so,” replied a voice from the summit of the kloof; “is that Bernhard?”

“Yes, Hans: are you hurt?”

“No, but the lion is: he is dying in a bush not far off. I don’t like to move, as I can’t see him: could you bring some lighted branches here?”

’Nquane, the Kaffir, and Bernhard each seized a large blazing branch, and grasping their guns, ascended the steep slope to the position occupied by Hans.

“Up this way,” said Hans, “the lion is to your right, and I think dead; but we had better not go near him till we are certain. Now give me a branch, I can light this grass, and go look for him.” Saying this, Hans advanced to some bushes and cast a handful of blazing grass before him. “He’s dead,” exclaimed Hans, “so come, and we will skin him: he’s a fine fellow!”

“Come down to the camp and eat first, Hans,” urged Bernhard, “and tell us where you have been, then come and skin the lion.”

“No, business first,” exclaimed Hans. “The jackalls might spoil the skin in a few minutes, and before the lion was cold; so we will first free him of his coat, then I will eat.”

It took Hans and his two companions only a short time to divest the lion of its skin, when the three returned to camp, where the new-comer was heartily welcomed, and where he was soon fully occupied in making a meal from the remains of the supper left by his companions. Hans Sterk, as he sat quietly eating his meal with an appetite that seemed to indicate a long previous fast, did not give one the idea of a very remarkable man. He was quite young—probably not more than two-and-twenty, and not of very great size; he was, however, what is called well put together, and seemed more framed for activity than strength; his eyes were deep-set and small, with that earnest look about them which seemed to plainly indicate that they saw a great deal more than most eyes. His companions seemed quite to understand Hans’ peculiarities, for they did not address a word to him whilst he was eating, being fully aware that had they done so they would have obtained no answer. When, however, he had completely satisfied his hunger, Bernhard said—

“What have you seen and done, Hans? and why are you so late? We feared you had lost the line for our resting-place before it got dark, and would not reach us to-night.”

“Lost the line,” replied Hans; “that was not easy, considering you stopped at the only river for ten miles round; but I was nearly stopping away all night, only I remembered you had such good fat eland for supper, and so I returned.”

“And what made you nearly stop away, Hans?”

“Few men like to walk about among bushes and krantzes when man-eating lions are on the look-out, and the sun has set for two hours,” replied Hans.

“Was there nothing else that kept you?” inquired Bernhard. “You left us all of a sudden.”

“Yes, there was something else kept me away.”

“And that was—”

“This,” said Hans, as he pulled from his coat pocket a small brown lump like India-rubber, from which two or three long wire-like bristles protruded.

“You came on elephants!” exclaimed several of the Boers. “What luck! The first we have seen. Were they bulls or cows?”

“I came on fresh elephant’s spoor soon after I left you,” said Hans. “I dared not come back to call you, and feared to miss you; so I went on alone, and saw the spoor of four large bull elephants. This spoor I followed for some distance, and then found that the creatures had entered the forest. But the place was good; there were large trees, and but little underwood; so I could see far, and walk easily. I came upon the elephants; they were together, and knew not I was near till I had fired, and the big bull dropped dead.”

“Where did you hit him, Hans?”

“Between the eye and the ear, and he fell to the shot.”

“The others escaped, then, Hans,” said Heinrich.

“Not before I had hit one with fine tusks behind the shoulder.”

“Then he escaped?”

“No, he went for two miles, then separated from the others, and stood in the thick bush. I becrouped (stalked him) and gave him my bullet between the eye and the ear, and he fell.”

“Where’s his tail, Hans?” said one of the Boers.

Hans drew from his pocket a second small black bristly lump, and placed it beside the first, saying, “There is the tail of the elephant in the thick bush.”

“What weight are the tusks, Hans?” said Bernhard.

“About sixty to eighty pounds each. They are old bulls with sound teeth.”

“And ivory is fetching five shillings a pound. A sixty pound business. Oh, Hans, you are lucky! Are there more there, do you think? Was there other spoor, or were these wanderers?”

“To-morrow,” replied Hans, “we may come upon a large herd of bulls, for before sundown I crossed fresh spoor of a herd of about twenty. They were tracking south, so we shall not have far to go.”

“But tell us,” said Victor, another Boer, “about the lion above there. How did you see him? It was dark, was it not?”

“Not very dark; the moon gave me light, and the creature whisked its tail just as it was going to spring, and so I saw it. I knew the place was one likely for a lion, and so had my eyes about me. It does not do to think too much when you walk in the veldt by night, or you may be taken unawares. I shot the lion between the eyes; and had he been any thing but a lion, he would have dropped dead; but a lion’s life is too big to go all at once out of so small a hole as a bullet makes, and so he did not die for ten minutes.”

“Where are the other two bull elephants, Hans?” inquired Victor. “Did they go far, do you think, or would they stop?”

“One is beside the Vlei near the Bavians Kloof; the other is in the thorn-bushes a mile from it.”

“But they won’t stop there. Where think you they will be to-morrow?”

“Where they are now,” replied Hans, as he quietly brought from his pocket the ends of two more elephants’ tails, and placed them beside those already on the ground.

“You have not killed all four bull elephants, Hans?” said Bernhard, with a look of astonishment. “Will a bull elephant let you cut off the end of his tail when he is alive, Bernhard? You taught me first how to spoor an elephant, and you never told me that he would let you do that; so I killed mine first, and then cut his tail off afterwards. I shot all four bull elephants, and expended but thirteen bullets altogether on them. The teeth will weigh nearly five hundred pounds, and so I think I have a good excuse for coming late to supper. But now, good-night. We must be up early, and so sleep is good for a steady hand in the morning, and we shall want it, for game is near and plentiful. Good-night, and sleep well.”

Chapter Two.

Following the Elephants—Cutting out the tusks—Hunting the herd of Elephants.

The sun’s rays had scarcely commenced illuminating the eastern horizon, when the hunters were up, and making their preparations for the start. The plan of hunting which they had adopted, was to enter the country with waggons, oxen, and horses; to leave their waggons at a good outspanning-place where there was plenty of water and forage for the cattle; then to scour the country round and search for game, or spoor, which if found, the horses, oxen, and waggons were brought up, and the elephants hunted on horseback. The elephant is so formidable an animal, and usually is so fierce, especially when wounded and hunted, that few African sportsmen venture to follow him on foot into his dense woody retreats. It is customary to drive the herd, when discovered, into the most open country, this driving being accomplished either by setting fire to the dried grass, by making large bonfires, or by discharging fire-arms, and thus causing the herds to leave a secure retreat for one less sheltered. It is not unfrequently a matter of two or three days, to drive elephants into a good and favourable country; and upon this driving being judiciously carried out, much of the success of the hunt depends. There are very many men whose livelihood depends entirely on elephant hunting. They farm but little, have few cattle, but devote their time mainly to hunting; and in a country so untrodden as was Africa some years ago, there was no want of game, and thus a man provided with horse, gun, powder, and lead, might live independent of almost all else.

Hans Sterk was a man who had been devoted to sport from his childhood. His father was a Dutchman who had early in his colonial career gone upon the outskirts of civilisation, and had been one of the pioneers to slay the wild beasts, and teach the savage man that the white man is the master over the black. Hans’ mother was an English woman, an emigrant who had ventured into Africa, and had there found a home. But both his parents had been cruelly murdered by the Kaffirs in one of their attacks upon the colonists; and at a very early age he had found himself owner of a waggon, some spans of oxen, a few head of cattle and horses, and had thus every means at his disposal for indulging in hunting; and as his taste led him in pursuit of the elephant, he soon became famed as an unerring marksman, an expert spoorer, and one of the most determined elephant hunters. On more than one occasion also he had distinguished himself in commandoes against the Kaffir tribes. Thus before he was twenty he had obtained a reputation for skill and bravery, and at that age was known as Hans Sterk, the elephant hunter. How well he deserved the title, the result of his day’s sport just related amply shows.

The morning after Hans’ return to the sleeping-place was fine, and well suited for spooring or shooting. There had been a heavy dew, and the wind was light, so that no extra noises disturbed the bushes, and rendered the feeding of an elephant inaudible, or the rush of a wild beast undistinguishable from the rustling of the forest branches. Hans had sent one of his Kaffirs to the waggons, to announce to the men there the death of four elephants, and to bring such aid as was requisite to cut out the tusks, and convey them to the waggons. He then with his white companions started on his footsteps of the previous night towards the ground where his elephants had fallen. Having with him a hatchet and knife, and aided by ’Nquane and his friend Bernhard, he proceeded to extract the tusks of his first elephant. The animal had fallen backwards, so that it lay in a very good attitude to be operated on; and Hans, taking his hatchet, cut down each side of the elephant’s trunk, so that at last this appendage could be turned completely over its head. The roots of the tusks were thus exposed to view, and were next attacked with the hatchet, the ends fixed in the jaws being loosened and cut off, by means of a fulcrum made from a large branch of a tree. The tusks were then worked up and down, and the hatchet applied to sever those parts which held most tenaciously, until the tusks were quite loose in the jaw, and could then be extracted with a good pull. About one-third of an elephant’s tusk is embedded in its jaw, and this part being filled up with muscles and nerves is hollow, and has to be cleaned out before it is inserted in the waggon. A tooth, as a tusk is called by elephant hunters, weighs about ten per cent, heavier when it is first taken from an elephant’s jaw, than when it becomes dry from keeping. Very few elephants’ tusks exceed 100 pounds in weight each, the average size of a good pair of tusks being from 100 to 150 pounds. Sometimes, however, a marvellous old bull, or one who has developed his teeth in a wonderful way, is found, whose teeth weigh nearly 130 pounds each; but such patriarchs are rarely met with.

The country in which elephants are found in abundance is usually thinly inhabited, and the natives are not possessed of fire-arms in great abundance or of much value. Thus the elephant, being a dangerous animal to hunt and hard to kill, often remains in forests when the more timid game of the open country has been driven away. But when English or Dutch sportsmen have visited a country, they usually wound mortally many more elephants than they kill and find, and thus the Kaffirs, who follow up and find the wounded animals, drive a very fair trade in elephants’ tusks, of which they soon understand the true value. Thus a party of hunters not unfrequently return from a three or four months’ shooting-trip into the interior with from two to three thousand pounds’ weight of ivory. There is, however, considerable risk in this sport when looked at from its mercantile point of view. It may happen that the country to which the hunters have travelled has been temporarily deserted by elephants in consequence of hunters having just previously hunted that ground, or from a scarcity of water. The horse or cattle sickness may attack the hunter’s quadrupeds, and thus, even if his waggons be full, he may have to leave them behind whilst he returns some four or five hundred miles to re-purchase cattle, again enter the country, and find his waggons probably pillaged and burnt he knows not by whom, his followers murdered, and he left to make the best of his way home again. Thus a hunter’s life is one of excitement and risk; and though the profits are great at times, and the life one which has irresistible charms, yet it is one not to be rashly undertaken by all men. There are, too, very many small chiefs, whose friendship it is necessary to gain by presents, or they will not allow you to journey through their country; and sometimes small wars take place between these potentates, when each party considers himself entitled to pillage all travellers who have been on friendly terms with his enemy.

There are, then, a goodly array of dangers and difficulties surrounding the African hunter, to say nothing of those which threaten him from wild beasts, such as lions, leopards, etc., or poisonous snakes. So that it is not difficult for a man as young even as Hans Sterk to gain a wide reputation for skill and bravery in surmounting those obstacles to which he had been frequently opposed.

The teeth of the various elephants slain by Hans having been extracted from the jaws of the animals, placed on the shoulders of Kaffirs, marked with Hans’ mark, and despatched to the waggons, Hans led the way over some bushy country towards a range of low hills near which a bright silvery streak indicated that a stream of water was flowing.

“Before I look for spoor where I expect it,” said Hans to his Dutch companions, “I will look through my ‘far-seer’” (as he termed his telescope), “to see what wilde there is in the open country.”

Adjusting his telescope to suit his focus, Hans took a careful look all round, and at length rested his glass against a tree and looked steadily down near the stream of which we have spoken. After a careful examination he offered his glass to a companion, and said, “I see eight or nine large bull elephants near the mimosas beside those yellow-wood trees. Can you see more?”

Chapter Three.

The Bull Elephant—The Charge of the Elephants—Counting the Spoils.

O ye lovers of true sport, men of nerve and skill, ye who prize a reality and are not satisfied with a feeble imitation, have you ever attempted to realise the excitement and glory of combating with a herd of lordly elephants, fierce and powerful, and monarchs in their own forests? Ye, who consider that the only sport is pursuing a fleeing fox over the grass-lands of your own country, can but feebly imagine the effect produced by measuring your skill and daring against the giant strength and cunning of a mighty elephant, who has braved his hundred summers, and has been able to withstand the bullets or spears of a hundred foes; who has won his way among his rivals by fierce and hardly contested battles; and who dreads no enemy, but is ever ready to try conclusions with the most formidable of all, viz. man. To stand alone and on foot, amidst the tangled luxuriant foliage of an African forest, within a few yards of one of these watchful monsters, whose foot could crush you as easily as could your foot a mouse or rat, and whose headlong rush through the forest would carry away every obstacle, is a proceeding which causes the blood to course through one’s veins like quicksilver. To hide near a troop of these animals, watching their strange movements and taking advantage of favourable opportunities for deadly shots, which are answered by the most savage and unearthly shrieks, is another phase of sport which is spirit-stirring in the extreme. Add to these scenes the most glowing landscape, covered with brilliant flowers, and ornamented with gorgeously-tinted birds, whilst various rare and graceful antelopes are bounding away in all directions to escape the tumult which has disturbed them, and there is an explanation of the mystery of that so-called hunter’s fever, which induces those who have once tasted such sport to ever afterwards thirst for it as the parched stag thirsts for water.

Surrounding Hans Sterk there were men who had slain lions and buffaloes, had brought to the earth the lofty cameleopard, and had frequently gathered tusks from their elephants slain in fair fight. Yet with these men the excitement had not worn off; and they, one and all, seemed to be endowed with additional life-power as they recognised with the ‘far-seer’ the largest of African game browsing calmly in his native wilderness. “We must not show ourselves,” said Hans, “or the alarm will spread. See those ostriches in the ‘open;’ they suspect us; and though they are two miles off, they can distinguish us among these thorns. Let us lie down, and we will make our plans for attacking those elephants.”

The whole party at once sank to the ground, and were thus completely concealed from the keen sight of all except the vultures, which were sailing about overhead. Each of the hunters then took a careful survey of the nature of the ground between his position and the river near which the elephants were browsing. After an interval of a few minutes, one of the eldest men asked the rest what plan they had made.

“You speak first, Piet,” was the answer of Hans; “then we will all give our opinions.”

“I think,” said Piet, “we should go down to the right, enter that bush, and so keep near the stream till we stalk on to the elephants; for the ground is very good where they are, and they will not move far whilst they can feed there.”

Nearly every one agreed with this remark except Hans, who, when his opinion was asked, said that he had two reasons why he should prefer another plan. First, the wind would not quite suit, but would blow from them to the elephants when they first entered the thorn-bushes. Then, in front of the elephants, and about a mile off, was a large dense forest. “If they enter that,” said Hans, “we shall not see them again. I should like to go down to the left, get in front of the elephants, and either wait for them to feed up to us, or stalk them up wind. Then when they run, they will go towards our waggons, and we shall be able to hunt those which are not killed to-day, with the aid of our horses to-morrow.” After a slight hesitation the hunters decided that this was the better plan, and determined at once to put it into execution. Each man examined the priming of his rifle, put on fresh caps, felt the position of his cartridges, powder-flask, and bullets, so as to be certain all was ready for use; and then, following each other in Indian file, the party strode forward in the direction agreed upon.

When hunters are in the neighbourhood of large game, it is an understood rule that a shot is not to be fired at any small animal. Thus, if a party were out in search of elephants, and had separated from each other, a shot from one party would at once bring the others to it, for it would be understood that elephants had been fired at. Thus antelopes of various kinds were allowed to gallop off without a shot being fired at them. A fat eland, whose appearance made the Kaffirs’ mouth almost water, was allowed to stand under a tree, and gaze with astonishment at the novel spectacle of a herd of two-legged creatures moving over its domain. For to have fired a shot would have not only disturbed the country, but would have been a reckless destruction of life, a proceeding which every true sportsman abhors. Taking advantage of the slopes of ground, the cover of trees, etc., Hans and his party turned the position of the elephants, and halted about five hundred yards in advance of them, without having caused these watchful, keen-scented animals any suspicion of their presence.

Each hunter took up a position behind a tree, immediately he came in front of the elephants, and there waited for some signal from the leader before advancing. It was soon evident that the elephants were feeding towards the hunters, and thus if they remained quiet, they would soon have their game within range. Twelve majestic bull elephants were in the herd, each with tusks of large size. Such game being close to them caused each man of the party to feel excited with the anticipation of the coming sport, and to reserve himself for his first shot. On came the troop, scarcely staying now to feed, for they had by some instinct or power of observation become slightly alarmed. The scent of the hunters, or the screech of some bird had indicated to them that an enemy was near, and thus they ceased feeding. A majestic twelve-foot bull elephant led the party, and seemed well qualified for a leader. He strode forward some dozen yards with trunk erect and ears wide-spread, then stopped and drew the air through his trunk with great rapidity, turning from side to side with a quickness which seemed surprising in so vast an animal. That lazy, stupid appearance which those who have seen caged animals only, are disposed to attribute to elephants, was very different from the activity of this leader, as his restless eye watched each bush or tree; and his threatening attitude occasionally indicated that he was ready to charge an enemy. Suddenly, as though a fresh cause for suspicion had arisen, the mighty bull raised his trunk, and gave three sharp, shrill, and powerful trumpet-notes, which might have been heard at a distance of two miles. Immediately a deep rumbling sound was uttered by all the other members of the herd, who stood instantly like so many bronze figures, the only indications of life being the shaking of their huge ears, which from time to time were erected, and then depressed. During fully two minutes this watchful attitude was maintained, after which one deep note was sounded by the leading bull, and the whole party strode onwards. They were, unluckily for them, advancing to destruction; for each hunter was now within fifty yards of the leader, and several rifles were already aiming at various parts of the grand-looking animal. A moment’s silence, broken only by the heavy tread of the elephants, and then the stillness of the wilderness was broken by the report of half-a-dozen heavy rifles. In an instant the scene was changed. The leading bull elephant reeled as he received the leaden hail; but his strong frame yet retained plenty of life, and, uttering a fearful shriek, he charged headlong at the tree behind which two of the hunters were concealed. The tree was large and strong, and the men trusted that it would stand even the rush of the elephant; but so great was the momentum of the vast bull, that the tree snapped as though it were a mere sapling, and the two hunters narrowly escaped being crushed by the tree, or trodden under foot by the enraged monster. As he charged onward, blinded with rage, he received another volley from the second barrel of the Boers’ rifles; bleeding from a dozen wounds, he still held on his mad career, until he could no longer withstand the shock to his system; he then suddenly stopped, threw up his trunk as though signalling his defeat, and sank back on the ground, the earth shaking and resounding with the fall. Following their leader until the smell of blood warned them that it was dangerous to pursue his course, the remaining elephants spread out on each side, and formed two parties; but their course was undecided, for their leader had been slain, and for a time they had no confidence in a successor. The hunters, having almost instantly reloaded their rifles, ran forward in order to intercept the elephants and cut them off from the dense bush towards which they were wending their way. Closing with one of the nearmost, Hans and two of his companions fired at the heavy shoulder, which for an instant was exposed to their aim. Responding to the report of the guns, the elephant trumpeted his defiance; and turning with rapidity he rushed at the assailants. Small trees and underwood gave way before the mountain of flesh which was urged against them, and any inexperienced men would have been in a dangerous position. To be charged by a savage bull elephant was not, however, any thing very novel either to Hans or his companions, who at once keeping close together ran to the more open part of the forest, but where large trees were abundant. For about forty yards, the three men ran shoulder to shoulder; but the elephant, with his giant strides, was gaining on them, and would, it appeared, soon reach his tiny enemies, whose fate would then be decided. But a hunter is full of expedients, and knows when to practise them; thus, as the elephant was rushing onwards in a straight course, Hans shouted, “Now,” when instantly the party separated, Hans turning sharp to the right, his two companions to the left, and each slipping behind a broad-stemmed tree. The elephant, either undecided which to pursue, or not seeing the artifice of his enemies, continued his rush onwards; but before he had gone many yards, the forest again echoed back the report of the hunters’ rifles, and three more bullets lodged behind the elephant’s ear caused him to pitch forward on his head, his tusks snapping off with a sharp crack, and he rolling to the ground harmless as the trees around him. Three other elephants that were badly wounded effected their escape; but the elephant hunters knew their death warrant had been signed; and so, assembling near the great elephant’s carcass, the successful men drank a “Soupe” of brandy, cut off the tail of the “game,” and for awhile talked over the events of the hunt. It was then decided to return to the waggons, bring them, with oxen and horses, near the stream by which they were then seated, and to hunt the remainder of the herd on horseback; for it was seen that if the country were not very favourable, but little success would be obtained if the elephants were pursued on foot. Now that the country had been alarmed by the report of fire-arms, there was no longer any need for concealment, so the hunters spread out instead of following in Indian file, for hunger began to remind them that the sun was past the meridian, and thus a slice from an antelope or an eland would not be objected to. It was not long before an eland and her calf were seen reclining beneath some acacia-trees; and the plan being arranged, the pair were soon surrounded, when the hunters, closing in, rendered their escape impossible, and both were shot by the hungry travellers. The elephants, having been feeding for some days in this neighbourhood, had deposited the fuel for a fire, which, dried by the sun, ignited rapidly, and in a few minutes was blazing beneath the strips of alternate fat and lean, which had been strung on two or three ramrods. And thus, in less than an hour from the sighting of the elands, their flesh was being eaten by the sportsmen, who, provided only with a paper of salt and a clasp-knife, were yet able to make an excellent dinner, which was washed down with some of the water from the stream, flavoured by a dash of brandy from the flasks carried by each hunter. It was near sunset when the party reached their waggons; but orders were given to inspan the oxen before daybreak, to have the horses ready, and to prepare for an early “trek” towards the clear stream and luxuriant forest in which the elephants had been hunted.

“There,” said Hans, “we have good water, plenty of wood and other stuff for fires, game in abundance and so we shall have nothing to do but eat, drink, sleep, and shoot; we shall kill the game that will yield us money, and so we need have no care. A hunter’s life is happy, and who would not be a hunter? Can you believe it, that Karl Zeitsman has gone down to Cape Town to write in a shop or something, because he wants to make money? Why our fore-looper’s life is a better one than his; and as to ours, one day in the veldt after game is worth a year in a town, where all is dirty, smoky, and bad. There is nothing like a free life, Bernhard, is there? and elephant hunting is the very best of all. Good-night, and sleep well, Bernhard,” said Hans as he crawled into his waggon; and, undisturbed by the roars of a distant lion, or the snores of his companions, he slept soundly and peacefully till near daybreak.

Chapter Four.

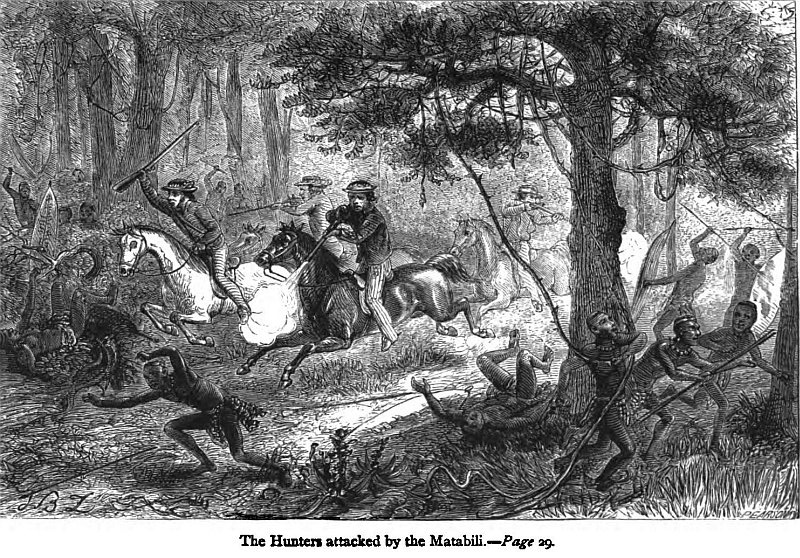

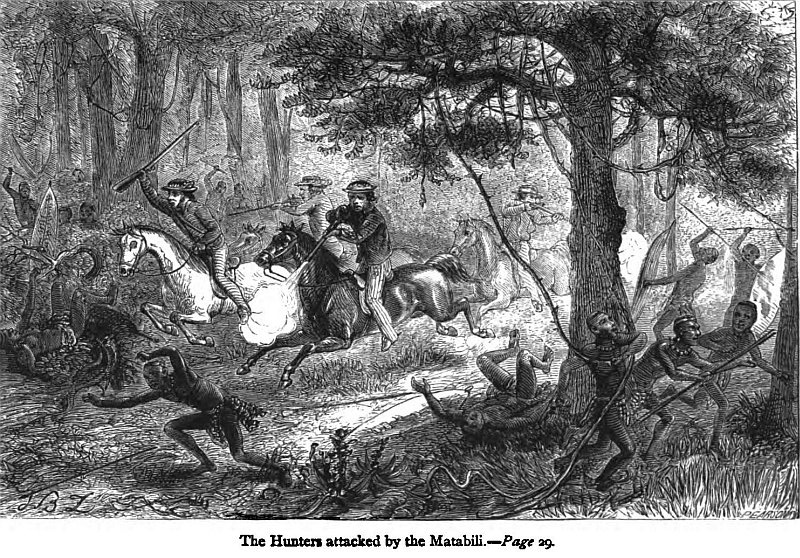

Seeking the Dead Elephants—Ambuscade of the Matabili Warriors—Escape of Hans Sterk and his Party—Battle with the Matabili—The Slaughter of Siedenberg.

“The waggons can follow,” said Hans; “that will be best. The Kaffir can show where the dead elephants are lying, and we will ride on. Shall we follow the spoor, Victor, or try and cut off the track?”

“Better follow the spoor, Hans, I think,” replied Victor; “but what does Heinrich say?”

“Follow the spoor from where we last saw the elephants; we are sure to find them there.”

It being thus agreed among the most experienced to follow the spoor, the whole party mounted their horses and rode on their journey, little expecting what was before them.

There was but little game visible to the hunters as they rode towards the locality on which their yesterday’s sport had been enjoyed; but this they believed was due to the alarm which their firing had caused; for so wide, is the country in Africa, that the animals can, if necessary, journey their forty miles during the night, and yet obtain a good grazing-ground free from interruption; so that a hunter rarely expects to find game in any district which has been hunted on the day previously, but looks for it some thirty miles distant. As the hunters rode forward the sun rose, and dried up the heavy dew which had covered the herbage during the night. The fog and mist were scattered before his burning rays, and the country once more exhibited its tropical appearance.

Hans, who had taken out his telescope to examine the country in various directions, at length exclaimed, “There is one of the Kaffirs near the elephants. How could he get there before us?”

“It is ’Nquane, perhaps; he is very quick, and may have passed us in the fog.”

“No,” replied Hans; “’Nquane, like all Kaffirs, does not like going a journey before the sun has dried and warmed the air. Can the man be a stray Matabili?”

“No matter if he is,” said one of the Boers. “Let us canter on; we shall soon see.”

The hunters increased their speed, and rode on towards their dead elephants, but saw, as they approached, no Kaffirs; and all except Hans began to doubt whether the figure he had seen really was a Kaffir, or only a stump burned and blackened so as to resemble a man. The party left the open country, and rode into the forest, being obliged to ride in file along the paths made by the elephants. They had penetrated about two hundred yards into the forest, when a shrill whistle was uttered from the wood behind, and instantly from all parts of the bush an armed Matabili warrior sprang to his feet. Two hundred men at least appeared, forming a ring, in the midst of which were the hunters. These warriors did not leave the white men long in doubt as to their intentions; but beating their shields, and waving their assagies, they rushed in towards their supposed victims.

With that readiness of expedient which a long training in such hunting expeditions as those we have described is likely to produce, the Dutchmen saw their only chance for escape. They turned their horses, and firing a destructive volley at the Matabili who blocked the path in their rear, spurred their horses, and charged at the opening which their bullets and slugs had cleared. Each man retained a charge in one barrel; and as each neared the enemy he fired from the saddle, and mostly killed or disabled his foe. So sudden had been the attack, and so rapid the retreat, that in five minutes from the first alarm the hunters found themselves clear of the bush, and with no further loss than two horses severely gashed by the assagies of their enemies, who fortunately possessed no fire-arms.

“The men belong to the old villain Moselekatse,” said Hans; “we must fight them in the open and not spare a man, or our waggon and oxen will be captured; let us halt and try to draw them out into this open bush. Are you all loaded, men?” inquired Hans, who, though nearly the youngest of the party, seemed at once to assume the position of leader.

“Yes, we are all, I think,” replied several... “And here come the Matabili, thinking to close with us. Now, for not wasting a single charge, give them the bullet in the distance, buckshot when nearer, the treacherous villains;” as he finished speaking he fired, and a dozen bullets were discharged; immediately afterwards, the dull thud of the bullets and the falling bodies of the enemy indicating the accuracy of the aims. The party were waiting for the Matabili to approach within range of buckshot and slugs; but Victor, luckily looking round, saw that two detachments had been sent round on the flanks in an endeavour to surround the horsemen, so that an immediate retreat was necessary. Every one of the hunters was, however, able to load his weapon whilst proceeding at full gallop; so that, having retreated far enough to escape being surrounded, the Boers halted, faced about, and again discharged their deadly weapons at the foe.

The leader of the Matabili soon saw that this system of fighting was not likely to lead to satisfactory results, so he whistled a signal to his men, who halted and began a retreat. The hunters however were not the men to spare their foe, but followed on their traces, shooting down their enemy with a fatal accuracy, until they reached the denser part of the forest, where the hunters dared not enter on foot against at least ten times their number, and where they could not enter on horseback. A short council of war decided them to leave half their number to watch the Matabili, whilst the remainder rode with all speed to the waggons, to stop them in their advance, and to make preparations for their defence in case an attack should be made upon them; for to defend waggons was very much more difficult than to carry on the light cavalry manoeuvres which had been so successful in the late attack of the black warriors.

There are few incidents of greater interest in connexion with our colonies than the desertion from our eastern frontier of the Cape of Good Hope of a body of about 5000 souls, who, dissatisfied with the Government to which they were compelled to own allegiance, departed with wives, children, goods, cattle, and horses into the wilderness, there to find a new home, far away from English dominion. It was in 1836 that this singular emigration took place, and it was just previous to that date that our tale commences.

Ruling over a large portion of country in about the twenty-sixth parallel of latitude, there was a chief named Moselekatse, whose tribe was termed Matabili. He was a renegade from the Zulu nation, and had by his talents formed a nation of soldiers. Between the warriors of Moselekatse and some Griquas, near the Orange River, several encounters had taken place, the latter being usually the assailants, their object being the capture of cattle, the Matabili being rich in herds. The Griquas are a tribe of bastard Hottentots, many of them being nearly white; and thus, in a Matabili’s opinion, nearly every white man was an enemy.

Believing that the ground on which they were hunting was too far from the dominions of the Matabili chieftain to make the position a dangerous one, Hans and his party had neither sent ambassadors to announce their purpose of hunting, nor had they expected to meet any bipeds in the district in which they had decided to hunt elephants. They probably would not even have been heard of by the soldiers of Moselekatse, and therefore not molested, had not a large party of the Matabili been ordered to make a reconnaissance in the neighbourhood of Natal where the Zulus were in force, and where it was said preparations were being made for an invasion of the Matabili territory. These men on their return heard the report of the white men’s rifles, and at once believed it would please their king if these rifles were brought into his presence. Concealing themselves carefully from their intended victims, and sending out a few spies to watch what was going on, the Matabili discovered where the elephants had been shot, and at once knew that on the following day the hunters would come to procure their ivory, so that an ambuscade could be arranged and the hunters surrounded and taken at a disadvantage. All was very carefully planned by the Matabili; but in consequence of the rapid decision and skill of the hunters, their plot was a failure. The Matabili were, however, formidable as enemies; they plotted deeply before they acted; and had the hunters been aware of the cunning of their foes, they would scarcely have felt as satisfied as they did when they had driven their assailants into a dense cover, and had thus compelled them to keep close, and change their attack into a defence.

Five of the hunters remained near the bush to watch the enemy, whilst five rode back towards the waggons; and thus the white men’s forces were divided. Following their back trail, the hunters rode at a canter in the direction of their last night’s outspan, eager to get to their waggons, and either put them into a state of defence, or start them in a direction away from that likely to be followed by the Matabili.

Hans Sterk, Victor, and three other Dutchmen formed the party that were returning to the waggons. After riding at a canter for some miles, they drew up and walked their horses, in order to allow them to regain their wind.

“This will be a bad day’s work for Moselekatse,” said Victor, “for we are too strong for him on the Orange river now; and if we make up a commando and attack him, he would be sure to be defeated. He has enough on his hands now with the Zulus, who will certainly make an attack on him very shortly.”

“We should have no difficulty in getting up a large party to attack the Matabili; for they have thousands of cattle, and there would be much to divide among those who ventured,” replied one of the Boers.

“They nearly succeeded this morning in finishing us,” said Hans. “Had we not been very quick, and ready with our guns, they would have surrounded us successfully; it is lucky they did not attack us last night at the waggons; we should all have been slaughtered if they had done so, as we should have been taken by surprise.”

“Yes, it is lucky,” said Victor; “and I don’t see how we could have escaped better than we have done, for, except that cut on your horse’s flank and a stab in Heinrich’s horse’s neck, we were untouched, whilst we must have killed and wounded nearly fifty of the Matabili.”

“Yes, we were fortunate,” replied Hans; “but I wish we were two hundred miles from here, with our waggons safely across the mountains. Here comes ’Nquane, and he seems in a hurry.”

No sooner did the Kaffir recognise the hunters than he ran towards them with the greatest eagerness, making all manner of signals. As soon as he came within speaking distance, he said—

“Chiefs, the Matabili came upon us at the waggons; they have killed Copen and Jack, and carried off all the oxen and horses. Oh, it is bad for us?”

Exclamations of anger and surprise were uttered by the hunters as they heard this intelligence; for they knew that without oxen all the wealth in their waggons was worthless, and could be carried off at any time by Moselekatse’s warriors, whenever they chose to come.

“How many Matabili were there?” inquired Hans.

The Kaffir opened and closed his two hands five times, thus indicating there were about fifty men.

“Only fifty!” exclaimed Hans. “Let us after them at once; surely we can beat away fifty Matabili; it is only ten apiece. You go back to the waggons, ’Nquane, and wait there; we will soon bring you back the oxen.”

The hunters immediately spurred on their horses, and rode rapidly in the direction which the marauders had taken; and having ascended a conical hill, Hans by the aid of his telescope discovered the oxen and their capturers moving rapidly over the open country, and distant scarcely two miles.

“A beautiful open country,” exclaimed Hans; “just the place for a fight on horseback, and we will give them a lesson of what we ‘Mensch’ can do.”

Seeing that there was little or no bush before the Matabili, into which they could effect their escape, the hunters did not distress their steeds by too great a speed; but cantering steadily onwards they were soon seen by the Matabili, who, leaving two of their number to drive the horses and oxen, then spread out in open order, beating their shields and shouting their defiance.

The horses ridden by the hunters were trained shooting horses, and were not therefore likely to be alarmed by the noises made by these men. Each animal also would allow its rider to fire from its back without moving a muscle; and thus the five hunters, armed as they were, well supplied with ammunition, and deadly as shots, were most formidable enemies, more so than the Matabili seemed to think; for these men had hitherto been opposed only to Hottentots and Griquas, whose courage and skill they despised. When, therefore, the Dutchmen halted, and each, selecting a victim, raised his rifle or smooth-bore to fire, the Matabili uttered taunting yells, dodged from side to side to distract their enemies’ aim, and charged towards their foes.

Suddenly the five guns were discharged, and five Matabili rolled over on the plain, each either killed or mortally wounded. The hunters instantly turned their horses, and, galloping at speed, avoided the charge of their enemies and the numerous assagies that were hurled after them. Adopting the same plan as on the former occasion, the hunters loaded as they rode away; and as soon as each man was ready, the signal was given for a halt, when it was found that the Matabili, finding pursuit useless, were returning after their stolen oxen. They did not seem to suspect the style of warfare which the Dutchmen practised, as they retreated very slowly, believing that their enemies were only anxious to escape; they soon, however, found, their mistake, as their enemies galloped up to within a hundred yards, and discharged their barrels into the crowded mass, a dozen men either falling or limping away badly wounded; for the heavy bullets and heavy charge of powder had caused one shot, in some cases, to bring down two victims.

The Matabili, finding by experience the power and skill of their few enemies, were now bent only on making their escape; and therefore, separating, they ran in all directions, leaving the oxen to be recaptured. Bent upon revenge, and upon freeing themselves from their enemies, the hunters followed their foes, shooting them like so many buck, until, finding their ammunition growing short, they returned to their oxen, which had been quietly grazing, unconscious of the battle that was being fought for their ownership. The animals being collected, were soon driven off towards the waggons; and before the sun had long passed the meridian, the oxen were inspanned, and the five Dutchmen and one Kaffir were urging forward the spans in a direction the opposite to that in which the Matabili’s country lay. The two Hottentot drivers were found dead, having been assagied by their enemies without mercy; but few articles had been taken from the waggons, for the thieves did not like to encumber themselves with much booty, as they hoped to escape by speed before the hunters discovered their loss. The two parties of Matabili had acted also in concert, one having been left to watch the waggons and attack them as soon as the Dutchmen had started for their morning’s hunt, the remainder having been moved forward to surprise the hunters when they were in the bush near the dead elephants. Both attacks had been unsuccessful; and now the only danger that the hunters feared was, that the Matabili, having been thus defeated, would return in a day or two with a large force, and, knowing that waggons can move but slowly, and rarely more than twenty-five miles a day, thus would soon overtake them and probably be able to ensure their capture and to revenge their late defeat. Before leaving the outspan, Hans wrote a few words on a paper, which he inserted in a split stick, planting this stick in the ground, so that it pointed at the sun. He rejoined his companions, who had each dismounted, and was either leading his horse, or allowing it to follow the waggons.

Hans had left a short account on the paper, of his proceedings, and had pointed the stick at the sun, in order to let his companions know when he had started, for they, he knew, would shortly return to the outspan, and would then follow the spoor of the waggons; but seeing the bodies of the Hottentots would be puzzled to account for every thing unless they were informed by some means.

“It will be bad for us if the rivers are swollen,” said Hans to Victor, as the two followed the rear waggon; “a day’s delay might cost us all our property here.”

“And our lives too,” said Victor.

“Scarcely our lives,” said Hans, “if we are watchful, our horses live, and our ammunition lasts. We can fight these Matabili in any numbers as long as they don’t possess fire-arms; when the day comes that they use guns and powder, it will be bad for us hunters, for then their numbers will render them very dangerous.”

“The English traders are supplying them as fast as they can with guns,” rejoined Victor; “it is hard for us that they do so, for we or our children may be shot by the guns these men supply, and yet we can do nothing, however much we may suffer from this money-making feeling.”

The oxen having treked for fully two hours, began to show signs of distress, so the hunters agreed to halt and to dine, for they did not consider any immediate attack was probable. They had scarcely lighted a fire and began to prepare for cooking, than the welcome sight of their companions greeted them. Two of the hunters were riding one horse, in consequence of one having died from the effects of an assagy wound; but there being five additional horses among the recaptured oxen, this loss was not a very severe one.

The new-comers announced that the Matabili had retreated farther into the forest, and did not appear disposed again to try their strength against their white enemies. The whole party exclaimed loudly against the treachery of the Matabili in attacking them when there was peace between Moselekatse and themselves. They were not aware that a savage is not very discriminating; and a raid having been made into Moselekatse’s country, some two months previously, by a party of Griquas, the warriors could not distinguish any great difference between a Dutchman and a Griqua, both being of a different colour to himself, and both being strangers in his land. A speedy revenge was decided on by the whole party as soon as they could collect a sufficient force for the purpose.

That no time was to be lost in escaping from that part of the country, was the unanimous opinion of the hunters; and so the oxen were inspanned again, and the journey continued without any delay. Thus for two days the party retreated without seeing any thing of an enemy. Game of various kinds was abundant; but except to supply themselves with food the hunters did not shoot, for they knew not how soon their lives might depend upon a plentiful supply of ammunition being at hand. So that each bar of lead was at once converted into bullets or slugs, the loose powder was made up into cartridges, and every gun cleaned and carefully loaded, so as to be as efficient as possible.

It was on the morning of the third day that the hunters observed in the distance what appeared to be a broken-down waggon, but no oxen or human beings seemed to be near it. Such a sight, however, as a wreck in the desert at once excited the curiosity of the travellers, who, leaving the waggons in charge of half the party, rode off to examine the scene on which the waggon appeared to have broken-down. As they approached the spot, they saw a man limp from out of a clump of bush and make signs to them, and this man they found to be a Hottentot, who was badly wounded in several places, and seemed almost famished with hunger.

Having supplied him with food, he informed them that he was the driver of one of three waggons belonging to a Dutchman, who, with his wife and two daughters, was travelling over the country in search of elands, when they were attacked by a party of Matabili, who came upon them at daybreak, and carried off oxen, wife, and daughters, killed the Dutchman and another Hottentot, and would have also killed him, had he not shammed to be dead.

Hans Sterk, who had been watching attentively the waggon and débris around, whilst he listened to the Hottentot’s remarks, suddenly and eagerly inquired what was the Dutchman’s name.

“Siedenberg,” said the Hottentot.

“Siedenberg!” shrieked Hans, as he grasped his rifle like a vice; “and Katrine was with him?”

“Ja,” said the Hottentot; “the Mooi Katrine has been carried off by the Matabili, and her little sister too.”

“Men,” said Hans, as he turned to his companions, “Katrine Siedenberg was to have been my wife in two months’ time. I swear she shall be freed from the Matabili, or I will die in the attempt. Which of you will aid me in my work, with your rifles, horses, and skill?”

“I will,” replied Victor.

“And I,” said Heinrich.

“And I,” said all those with him; “but we must get more men.”

It was immediately agreed that the journey should be continued until the waggons and their contents were placed in safety, for the Matabili had two days’ start, and therefore could not be overtaken by the poor half-starved horses, which now alone belonged to the hunters. Fresh horses, more people, and more ammunition were necessary, and then a successful expedition might be carried on against Moselekatse and his warriors. The Hottentot was helped back to the hunter’s waggons and allowed to ride in one of them; and the onward journey was continued with all speed, so that in three days after finding the broken-down waggon, the hunters had crossed the Nama Hari river, and had joined a large party of the emigrant farmers, who were encamped south of this river.

The news of the attack on the hunters, the slaughter of Siedenberg, and the carrying off of his daughters, scarcely required to be detailed with the eloquence which Hans brought to bear upon it, in order to raise the anger and thirst for vengeance of the Dutchmen. Those who could were at once eager to bear arms against their savage and treacherous foe, whose proceedings caused a feeling of insecurity to pervade the Boers’ encampment; and thus the expediency of inflicting a lesson on the black chieftain was considered advisable. And also there was a strong temptation to inflict this lesson, when it was remembered that enormous herds of sleek cattle belonged to the Matabili, and would of course become the property of the conquerors; and who those conquerors would be was not doubtful, considering the relative value of assagies and double-barrelled guns.

Chapter Five.

Commando against the Matabili and Moselekatse, the Chief of the Matabili.

To men who lived the life of the farmer in Africa, surrounded on all sides by savage animals, or those creatures which were hunted for the sake of their flesh, obliged to be watchful at all times on account of their enemies—the Kaffirs of the old colony and the tribes to the north of them—their preparations for a campaign were speedily made; and on the morning following that on which Hans Sterk’s party had rejoined his companions, more than eighty Dutchmen, with as many after riders, all well-armed and mounted, were ready to start on their expedition against the Matabili.

The foe against which this party was being led was known to be both cunning and daring, and so it was considered expedient to place the camp in a state of defence, lest the enemy, taking advantage of the absence of the greater number of the fighting men, should select that time for their attack; for such is the usual proceeding of African chieftains against their enemies. The waggons were therefore drawn together and brushwood placed so as to prevent an easy entrance among them, regular watches were set, so that a surprise would have been difficult, had it been attempted; and a regular attack when the Boers were prepared would have ended in a fearful slaughter of the assailants. Matters being thus satisfactorily arranged at home, the expedition started, amidst great firing of guns, this being among the Africanders the substitute for cheering.

A leader having been chosen from among the Boers, the party started full of hope, and during the first day had travelled nearly forty miles. Every precaution was taken to avoid being surprised and also to ensure surprising the enemy, for the Boers were well aware of the advantages to be gained from surprising such an enemy as the Matabili. Game was abundant in the country through which the commando passed, and thus it was not necessary for the men to burden themselves with much weight in the form of food; water was at this time of the year plentiful, and thus the two essentials of life, food and water, were to be obtained with ease. To men who loved adventure as much as did these men, such an expedition as this was sport; and had any stranger come to the bivouac at night, seen the jovial, free-from-care manner of the Boers, and heard their spirit-stirring tales, he would scarcely have imagined that these men were bound on a matter of life and death, and were shortly to be engaged with a brave and powerful enemy, who, though badly armed, still outnumbered them in the ratio of twenty to one. Of all the party, Hans Sterk alone seemed quiet and thoughtful; but his look of determination indicated that his thoughts were certainly not pacific; and when the evening arrived, and the men halted until the moon rose and enabled them to continue their journey, none were more active or watchful than Hans Sterk the elephant hunter.

Five days and nights of rapid travelling brought the Boers within a few hours’ journey of the head-quarters of the Matabili, when it was decided to halt in order to refresh both men and horses, and to endeavour to gain such information as to the disposition of the fighting men of the Matabili, as would enable them to attack the enemy at the weakest point. Whilst the Boers were thus undecided, they were joined by a party of about a dozen of their countrymen, who had been on an exploring expedition, and having left their wives and children with some men as escort, whilst they departed on a few days’ journey, returned to find their waggons destroyed and their relatives murdered. Hastening with all speed to their companions, they heard of their departure to attack the Matabili, and immediately started to join them. On their journey they had come up with and surprised a party of Matabili, whom they at once attacked, killing all except one man, whom they made prisoner; this one man being capable, they thought, of being eventually of use.

Moselekatse had made it law, that any man who was either taken prisoner or who lost his weapons in a battle, and did not bring those of an enemy, was no more to be seen in his country. Thus the captured Matabili considered it the better plan to turn traitor, and endeavour to make himself useful to his captors. He therefore informed them that if they journeyed up westward of North, they might enter Moselekatse’s country from a position where they were not expected, and where no spies were on the look out; and thus, if the attack were made at daybreak, a fearful slaughter must ensue.

Acting on this advice, the Boers started in the required direction, and were ready to dash upon their foes as soon as the first streaks of daylight illumined the land. Their attack was entirely unexpected, for the Matabili who had committed the slaughter on the wandering farmers, and who had attacked the hunters, had only just returned, and were rejoicing in their successes and in the trophies they had brought to the feet of their king. Before, however, the sun had risen more than ten times its height above the horizon, about 400 of the Matabili warriors were lying dead on the plains around their huts.

Hans Sterk had not, like many of his companions, been entirely occupied with slaughtering the enemy, he had been searching in all directions to find some traces of the prisoners who had been carried off by the Matabili; but he failed in doing so, until he found a wounded enemy, to whom he promised life if he would inform him where the white maidens were hidden. It was with difficulty that the two communicated, for Hans was but imperfectly acquainted with the half-Kaffir dialect spoken by the Matabili, and the wounded man understood but a few words of Dutch. Still, from him Hans learnt that Katrine and her sister were prisoners at Kapain, where Moselekatse then was; this place being a day’s journey from Mosega, where the battle, or rather slaughter, had just taken place.

Hans’ interests were not the same as those of the other Dutchmen; he was mainly bent upon recovering Katrine from her barbarous jailor, and immediately making her his wife; whilst his companions were only anxious to capture and carry off the large herds of cattle which were grazing around, and to take with them the waggons lately taken from the travellers. It was in vain that Hans pointed out to the commander of the expedition the advantages to be derived from following up with rapidity the successes already obtained, and to attack the chief of the Matabili where it was impossible he could escape. Carried away by his brief success, and uninfluenced by the arguments of one as young as Hans Sterk, the commander of the expedition refused to advance, and ordered the immediate retreat of the whole party, with about seven thousand head of cattle. This plan, having gained the approval of the majority of the men who formed the commando, was at once put into execution, and the retreat was commenced; and in a few days the wives, daughters, and children left at the waggons were rejoiced at the return of the expedition, with such a valuable capture as many thousand head of cattle. The news of this success spread among the colonists with magical effect, and many who had at first hesitated to follow the desert wanderers, now used the greatest expedition to do so, and thus the ranks of the wanderers were increased by some hundreds of souls. But one drawback existed, however, amidst the rejoicings, and that was, that Hans Sterk, Bernhard, and Victor, had undertaken what was considered a foolhardy expedition; for they had left the main body on the day after the battle, and were intent upon trying to effect the escape of two prisoners from the kraals of Moselekatse himself; such an attempt being almost reckless, and unlikely to succeed, considering the power and watchfulness of the enemy against whom they were about to try their skill. But we will return to Hans and his two companions.

Chapter Six.

Hans determines to follow Katrine—He journeys by Night—Hans watches the Enemy.

No sooner had Hans discovered that the Matabili had taken the two Dutch girls to a distant kraal, than he determined at all risks to attempt their release. During the first halt that occurred after the slaughter of the Matabili, he called his two great friends, Victor and Bernhard, to him, and said—

“I have failed to persuade the Governor-General to attack the enemy where he would be able utterly to defeat him and prevent him from again attacking us; for this defeat at Mosega is only like cutting off one of his fingers, whereas, if we went on to Kapain, we should attack his body. But I am going to try to release Katrine; and I have a plan in my head which may succeed, so to-night I shall leave the camp.”

Victor and Bernhard looked at one another for some time; and then, as though reading each other’s thoughts, they turned to Hans, when Victor, speaking first, said—

“I don’t know what your plans are, Hans; but you shall not go alone. I will go with you, and I think Bernhard will go also.”

“Yes, I will go,” said Bernhard, “so let us talk over your plans.”

The three friends, having thus agreed to share each other’s fate, separated themselves from their companions, and sat down beneath a tree whose wide-spreading branches sheltered them from the heavy dew that was falling. Each having lighted his pipe and remained quiet for several minutes, was ready to listen or speak, according to circumstances.

“My plans,” said Hans, are these: “to travel to the northward, and conceal ourselves and our horses in the range of hills that overlook Kapain. With my telescope I can observe all that goes on in the kraals, while we run no risk of being seen. Our spoor will scarcely be recognised, because so many horses have been travelling here lately; and the attention of all the Matabili will be occupied in either watching the main body of our people or in making preparations for an expedition against them. They would never suspect that two or three of us would remain in their country; and thus we, by daring, may avoid detection. If we are discovered, we can ride away from the Matabili; and thus, though at first it seems a great risk, yet it is not so bad after all. These are my ideas.”

“But,” inquired Victor, “how are you going to get Katrine away, or her sister?”

“I will take two spare horses with me, and they can then ride with us.”

“You can’t let Katrine know where you are, even if she is in the kraal at Kapain,” said Victor; “and without we can get to her, our journey will be useless.”

“Victor,” said Hans, “will you trust me? I know what I am about, and will not do any thing without seeing to what the spoor is leading; we will start in half an hour.”

A few words from Hans to the leader of the Boers informed him of his intention of leaving the party; and though the chief urged upon Hans the recklessness of his proceedings, he had yet no actual authority to prevent him and his two companions from acting as they wished; so, cautioning him of the risk he ran, he wished him success, and bade him good-bye.

It was about midnight when Hans and his companions left the Boers’ encampment and started on their perilous journey. They rode for a considerable distance on the back spoor of their track, then, turning northward, they followed the course of some streams which flowed from the ranges of hills in the North-East. They continued their journey with rapidity, for the moon shone brightly and enabled them to see clearly for some distance around them. Many strange forms were seen during their journey, for Africa is full of night wanderers, and occasionally the deep growl of the lion, or the cry of the leopard was audible, within a few yards of them; but Hans and his companions were bent upon an expedition, and against foes of such importance, that even lions and leopards were looked upon as creatures not to be noticed, unless they seemed disposed to attack the travellers. The rapidity with which Hans and his companions rode, the silence maintained by them, and the purpose-like manner in which they continued a straight course, turning neither to the right nor left, even though a lion roared before them, gave to their journey a weirdlike character and reminded them of the dangers to which they were exposed; for, the Matabili, smarting as they just were from the defeat at Mosega, were not likely to delay the slaughter of any white men who might fall into their hands. Hans and his companions knew that the expedition was one for life or death; but it was not the first time that these men had looked on death calmly; and they were so confident in their own expedients that there were few circumstances for which they were not prepared.

As soon as the first light of morning began to appear, the three hunters rode into a ravine covered with brushwood and trees; having ascended this for some distance they found that it was possible to ride out of it in three directions besides that in which they had entered, and thus that a retreat was easily effected, should they be attacked from any one direction. They then dismounted, slackened the girths and took off the saddles, removed the bits from their horses’ mouths, and allowed the animals to enjoy a roll in the grass, this being a proceeding which invariably refreshes an African steed, and without it he seems only half capable of enjoying his feed of grass; no sooner, however, had the animals rolled, than each was again saddled, and with the exception of loosened girths, was ready to be mounted in half a minute. The guns were examined, to see whether the night dew had rendered a miss fire probable; and then, having made a careful examination of the surrounding country with his telescope, Hans announced that after eating some of the beltong, (Meat dried in the sun), with which each was provided, two had better sleep whilst one watched, and so they could all have enough rest to fit them for the journey of the following night; having volunteered to watch first, Hans requested his companions to go to sleep, a request with which every thoroughly trained hunter should be able to comply; for he should always eat, drink, and sleep when he can, for when he wants to perhaps he may not be able. And when a hunter has nothing to do, he should sleep, for then he will be ready to dispense with his rest when it may be of importance that he should be watchful.

In a very few minutes Victor and Bernhard were snoring as though they were sleeping on a down bed instead of on the ground in an enemy’s country, whilst the horses were making the best use of their time by filling themselves with the sweet grass in the ravine.

Hans had not been on watch more than an hour, when by the aid of his telescope he discovered a large body of Matabili who were following the spoor of his horses, and seemed as though bent on pursuing him. This sight caused him considerable anxiety, not on account of the numbers of his enemies, but because a fight with them, or a retreat from them, would defeat his plans for liberating Katrine. Hans therefore watched his enemies with the greatest interest, and could distinguish them distinctly, though they were distant nearly three miles. They approached to within two miles, and he was about to awaken his companions when he noticed the Matabili halted, and the chiefs’ seemed to be talking about the spoor, as they pointed to the ground several times and then at different parts of the surrounding country. The ground was so hard and the dew had fallen so heavily immediately before sunrise, that Hans hoped the hesitation on the part of his enemies might be in consequence of a dispute or difference of opinion as regarded the date of the horses’ footprints; for the probability was, that those left by his own and his companions’ horses might be supposed to be those of stragglers of the expedition which had attacked the Matabili at Mosega. This he believed to be the case when he found that the numerous body of enemies, after a long consultation, quitted his spoor and turned away towards the West, moving with rapidity in the direction in which the main body of the Boers had retreated, and thus almost taking his back trail, instead of following him to his retreat. Several other small parties of armed Matabili were seen during the day; but none approached the ravine in which Hans was concealed, and the day passed and night arrived without any adventure.

Chapter Seven.

Expedition of the Matabili—Hans telegraphs to Katrine, and receives his Answer.