The Project Gutenberg EBook of An American Girl Abroad, by Adeline Trafton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: An American Girl Abroad Author: Adeline Trafton Illustrator: Miss L. B. Humphrey Release Date: May 8, 2010 [EBook #32289] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN AMERICAN GIRL ABROAD *** Produced by Emmy, Tor Martin Kristiansen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

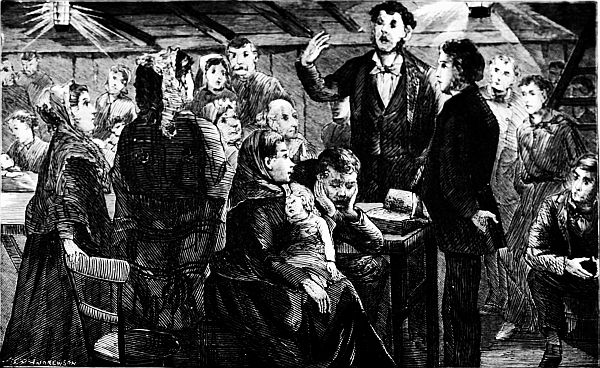

"At night we descended into the depths of the steamer to worship with the steerage passengers." Page 23

"At night we descended into the depths of the steamer to worship with the steerage passengers." Page 23

One of the most bright, chatty, wide-awake books of travel ever written. It abounds in information, is as pleasant reading as a story book, and full of the wit and sparkle of "An American Girl" let loose from school and ready for a frolic.

"It is a thrilling story, written in a fascinating style, and the plot is adroitly handled."

It might be placed in any Sabbath School library, so pure is it in tone, and yet it is so free from the mawkishness and silliness that mar the class of books usually found there, that the veteran novel reader is apt to finish it at a sitting.

"A delightful book, original and enjoyable," says the Brownville Echo.

"A fascinating story, unfolding, with artistic touch, the young life of one of our impulsive, sharp-witted, transparent and pure-minded girls of the nineteenth century," says The Contributor, Boston.

Pure, strong, healthy, just what might be expected from the pen of so gifted a writer as Mrs. Cheney. A very interesting picture of life among the New Hampshire hills, enlivened by the tangle of a story of the ups and downs of every-day life in this out-of-the-way locality. The characters introduced are quaintly original, and the adventures are narrated with remarkable skill.

"A wholesome story of home life, full of lessons of self-sacrifice, but always bright and attractive in its varied incidents."

A hearty and healthy story, dealing with young folks and home scenes, with sleighing, fishing and other frolics to make things lively.

| PAGE | |

| I. | |

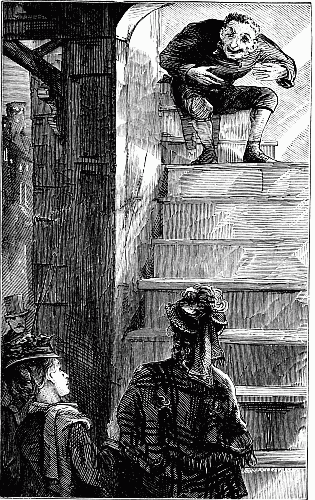

| "At night we descended into the depths of the steamer to worship with the steerage passengers." | Frontispiece. |

| II. | |

| "A dozen umbrellas were tipped up; the rain fell fast upon a dozen upturned, expectant faces." | 57 |

| III. | |

| "At the word of command they struck the most extraordinary attitudes." | 157 |

| IV. | |

| "Frowsy, sleepy, cross, and caring nothing whatever for the sun, moon, or stars, we stood like a company of Bedlamites, ankle deep in the wet grass upon the summit." | 176 |

| V. | |

| "Evidently the little old woman is going a journey." | 196 |

| VI. | |

| "Together we stared at him with rigid and severe countenances." | 240 |

CHAPTER I. | |

| ABOARD THE STEAMER. | |

| We two alone.—"Good by."—"Are you the captain of this ship?"—Wretchedness.—The jolly Englishman and the Yankee.—A sail!—The Cattle-man.—The Jersey-man whose bark was on the sea.—Church services under difficulties.—The sweet young English face.—Down into the depths to worship.—"Beware! I stand by the parson."—Singing to the fishes.—Green Erin.—One long cheer.—Farewell, Ireland. | 13 |

CHAPTER II. | |

| FIRST DAYS IN ENGLAND. | |

| [8]Up the harbor of Liverpool.—We all emerge as butterflies.—The Mersey tender.—Lot's wife.—"Any tobacco?"—"Names, please."—St. George's Hall.—The fashionable promenade.—The coffee-room.—The military man who showed the purple tide of war in his face.—The railway carriage.—The young man with hair all aflame.—English villages.—London.—No place for us.—The H. house.—The Babes in the Wood.—The party from the country.—We are taken in charge by the Good Man.—The Golden Cross.—Solitary confinement.—Mrs. B.'s at last. | 27 |

CHAPTER III. | |

| EXCURSIONS FROM LONDON. | |

| Strange ways.—"The bears that went over to Charlestown."—The delights of a runaway without its dangers.—Flower show at the Crystal Palace.—Whit-Monday at Hampton Court.—A queen baby.—"But the carpets?"—Poor Nell Gwynne.—Vandyck faces.—Royal beds.—Lunch at the King's Arms.—O Music, how many murders have been committed in thy name!—Queen Victoria's home at Windsor.—A new "house that Jack built."—The Round Tower.—Stoke Pogis.—Frogmore.—The Knights of the Garter.—The queen's gallery.—The queen's plate.—The royal mews.—The wicker baby-wagons.—The state equipages. | 43 |

CHAPTER IV. | |

| SIGHT-SEEING IN LONDON. | |

| The Tower.—The tall Yankee of inquiring mind.—Our guide in gorgeous array.—War trophies.—Knights in armor.—A professional joke.—The crown jewels.—The room where the little princes were smothered.—The "Traitor's Gate."—The Houses of Parliament.—What a throne is like.—The "woolsack."—The Peeping Gallery for ladies.—Westminster Hall and the law courts.—The three drowsy old women.—The Great Panjandrum himself.—Johnson and the pump.—St. Paul's.—Wellington's funeral car.—The Whispering Gallery.—The bell. | 55 |

CHAPTER V. | |

| AWAY TO PARIS. | |

| [9]The wedding party.—The canals.—New Haven.—Around the tea-table.—Separating the sheep from the goats.—"Will it be a rough passage?"—Gymnastic feats of the little steamer.—O, what were officers to us?—"Who ever invented earrings?"—Dieppe.—Fish-wives.—Train for Paris.—Fellow-passengers.—Rouen.—Babel.—Deliverance. | 68 |

CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE PARIS OF 1869. | |

| The devil.—Cathedrals and churches.—The Louvre.—Modern French art.—The Beauvais clock, with its droll, little puppets.—Virtue in a red gown.—The Luxembourg Palace.—The yawning statue of Marshal Ney.—Gay life by gas-light.—The Imperial Circus.—The Opera.—How the emperor and empress rode through the streets after the riots.—The beautiful Spanish woman whose face was her fortune.—Napoleon's tomb. | 76 |

CHAPTER VII. | |

| SIGHTS IN THE BEAUTIFUL CITY. | |

| The Gobelin tapestry.—How and where it is made.—Père La-Chaise.—Poor Rachel!—The baby establishment.—"Now I lay me."—The little mother.—The old woman who lived in a shoe.—The American chapel.—Beautiful women and children.—The last conference meeting.—"I'm a proof-reader, I am." | 90 |

CHAPTER VIII. | |

| SHOW PLACES IN THE SUBURBS OF PARIS. | |

| [10]The river omnibuses.—Sèvres and its porcelain.—St. Cloud as it was.—The crooked little town.—Versailles.—Eugenie's "spare bedroom."—The queen who played she was a farmer's wife.—Seven miles of paintings.—The portraits of the presidents. | 100 |

CHAPTER IX. | |

| A VISIT TO BRUSSELS. | |

| To Brussels.—The old and new city.—The paradise and purgatory of dogs.—The Hôtel de Ville and Grand Place.—St. Gudule.—The picture galleries.—Wiertz and his odd paintings.—Brussels lace and an hour with the lace-makers.—How the girls found Charlotte Brontë's school.—The scene of "Villette." | 109 |

CHAPTER X. | |

| WATERLOO AND THROUGH BELGIUM. | |

| To Waterloo.—Beggars and guides.—The Mound.—Chateau Hougomont.—Victor Hugo's "sunken road."—Antwerp.—A visit to the cathedral.—A drive about the city.—An excursion to Ghent.—The funeral services in the cathedral.—"Poisoned? Ah, poor man!"—The watch-tower.—The Friday-market square.—The nunnery.—Longfellow's pilgrims to "the belfry of Bruges." | 122 |

CHAPTER XI. | |

| A TRIP THROUGH HOLLAND. | |

| [11]Up the Meuse to Rotterdam.—Dutch sights and ways.—The pretty milk-carriers.—The tea-gardens.—Preparations for the Sabbath.—An English chapel.—"The Lord's barn."—From Rotterdam to the Hague.—The queen's "House in the Wood."—Pictures in private drawing-rooms.—The bazaar.—An evening in a Dutch tea-garden.—Amsterdam to a stranger.—The "sights."—The Jews' quarter.—The family whose home was upon the canals.—Out of the city.—The pilgrims. | 134 |

CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE RHINE AND RHENISH PRUSSIA. | |

| First glimpse of the Rhine.—Cologne and the Cathedral.—"Shosef in ter red coat."—St. Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins.—Up the Rhine to Bonn.—The German students.—Rolandseck.—A search for a resting-place.—Our Dutch friend and his Malays.—The story of Hildegund.—A quiet Sabbath.—Our Dutch friend's reply.—Coblentz.—The bridge of boats.—Ehrenbreitstein, over the river.—A scorching day upon the Rhine.—Romance under difficulties.—Mayence.—Frankfort.—Heidelberg.—The ruined castle.—Baden-Baden.—A glimpse at the gambling.—The new and the old "Schloss."—The Black Forest.—Strasbourg.—The mountains. | 147 |

CHAPTER XIII. | |

| DAYS IN SWITZERLAND. | |

| [12]The Lake of Lucerne.—Days of rest in the city.—An excursion up the Righi.—The crowd at the summit.—Dinner at midnight.—Rising before "the early worm."—The "sun-rise" according to Murray.—Animated scarecrows.—Off for a tour through Switzerland.—The lake for the last time.—Grütlii.—William Tell's chapel.—Fluellen.—Altorf.—Swiss haymakers.—An hour at Amsteg.—The rocks close in.—The Devil's Bridge.—The dangerous road.—"A carriage has gone over the precipice!"—Andermatt.—Desolate rocks.—Exquisite wild flowers.—The summit of the Furka.—A descent to the Rhone glacier.—Into the ice.—Swiss villages.—Brieg.—The convent inn.—The bare little chapel on the hill.—To Martigny. | 168 |

CHAPTER XIV. | |

| AMONG THE EVERLASTING HILLS. | |

| The quaint inn.—The Falls of the Sallenches, and the Gorge de Trient.—Shopping in a Swiss village.—A mule ride to Chamouni.—Peculiarities of the animals.—Entrance to the village.—Egyptian mummies lifted from the mules.—Rainy days.—Chamois.—The Mer de Glace.—"Look out of your window."—Mont Blanc.—Sallenches.—A diligence ride to Geneva.—Our little old woman.—The clownish peasant.—The fork in the road.—"Adieu." | 189 |

CHAPTER XV. | |

| LAST DAYS IN SWITZERLAND. | |

| Geneva.—Calvin and jewelry.—Up Lake Leman.—Ouchy and Lausanne.—"Sweet Clarens."—Chillon.—Freyburg.—Sight-seers.—The Last Judgment.—Berne and its bears.—The town like a story.—The Lake of Thun.—Interlaken.—Over the Wengern Alp.—The Falls of Giessbach.—The Brunig Pass.—Lucerne again. | 201 |

CHAPTER XVI. | |

| BACK TO PARIS ALONE. | |

| Coming home.—The breaking up of the party.—We start for Paris alone.—Basle, and a search for a hotel.—The twilight ride.—The shopkeeper whose wits had gone "a wool-gathering."—"Two tickets for Paris."—What can be the matter now?—Michel Angelo's Moses.—Paris at midnight.—The kind commissionaire.—The good French gentleman and his fussy little wife.—A search for Miss H.'s.—"Come up, come up."—"Can women travel through Europe alone?" A word about a woman's outfit. | 220 |

The time of departure arrived. We said the two little words that bring so many tears and heartaches, and ran up on the deck with the rain in our faces, and something that was not all rain in our eyes, for one last look at our friends; but they were hidden from sight. There comes to me a dim recollection of attempting to mount to an inaccessible place: of clinging to wet ropes with the intention of seeing the last of the land; of thinking it, after a time, a senseless proceeding, and of resigning ourselves finally to our berths and inevitable circumstances. Eight bells and the dinner bell; some one darkened our doorway.

"What's this? Don't give it up so. D'ye hear the dinner bell?"

"Are—are you the captain of this ship?" gasped Mrs. K., feebly, from the sofa.

"To be sure, madam. Don't give it up so."

Mrs. K. groaned. There came to me one last gleam of hope. What if it were possible to brave it out! In a moment my feet were on the floor, but whether my name were McGregor, or not, I could not tell. I made an abortive attempt after the pretty hood, prepared with such pleasant anticipations, and had a dim consciousness that somebody's hands tied it about my head. Then we started. We climbed heights, we descended depths indescribable, in that short walk to the[16] saloon, and there was a queer feeling of having a windmill, instead of a head, upon my shoulders. A number of sympathizing faces were nodding in the most remarkable manner, as we reached the door, and the tables performed antic evolutions.

"Take me back!" and the berth and the little round stewardess received me. There followed a night of misery. One can form no idea, save from experience, of the horrors of the first night upon an ocean steamer. There are the whir, and buzz, and jar, and rattle, and bang of the screw and engine; the pitching and rolling of the ship, with the sensation of standing upright for a moment, and then of being made to rest comfortably upon the top of your head; the sense of undergoing internal somersaults, to say nothing of describing every known curve externally. You study physiology involuntarily, and doubt if your heart, your lungs, or indeed any of your internal organs, are firmly attached, after all; if you shall not lose them at the next lurch of the ship. Your head is burning with fever, your hands and feet like ice, and you feel dimly, but wretchedly, that this is but the beginning of sorrows; that there are a dozen more days to come. You are conscious of a vague wonder (as the night lengthens out interminably) what eternity can be, since time is so long. The bells strike the half hours, tormenting you with calculations which amount to nothing. Everything within the room, as well as without, swings, and rolls, and rattles. You are confident your bottles in the rack will go next, and don't much care if they do, though you lie and dread the crash. You are tormented with thirst, and the ice-water is in that same[17] rack, just beyond your reach. The candle in its silver case, hinged against the wall, swings back and forth with dizzy motion, throwing moving distorted shadows over everything, and making the night like a sickly day. You long for darkness, and, when at last the light grows dim, until only a red spark remains and the smoke that adds its mite to your misery, long for its return. At regular intervals you hear the tramp, tramp, overhead, of the relieving watch; and, in the midst of fitful slumbers, the hoarse voices of the sailors, as the wind freshens and they hoist the sails, wake you from frightful dreams. At the first gray dawn of light come the swash of water and the trickling down of the stream against your window, with the sound of the holy-stones pushed back and forth upon the deck. And with the light—O, blessed light!—came to us a dawn of better things.

There followed days when we lay contented upon the narrow sofa, or within the contracted berths, but when to lift our heads was woe. A kind of negative blessedness—absence from misery. We felt as if we had lost our heart, our conscience, and almost our immortal soul, to quote Mark Twain. There remained to us only those principles and prejudices most firmly rooted and grounded. Even our personal vanity left us at last, and nothing could be more forsaken and appropriate than the plain green gown with its one row of military buttons, attired in which, day after day, I idly watched the faces that passed our door. "That's like you Americans," said our handsome young Irish doctor, pointing to these same buttons. "You can't leave your country without taking the spread-eagle with you!"[18]

Our officers, with this one exception, were English. Our captain, a living representative of the traditional English sailor. Not young, save in heart; simple, unaffected, and frank in manner, but with a natural dignity that prevented undue familiarity, he sang about the ship from morning till night, with a voice that could carry no air correctly, but with an enjoyment delightful to witness—always a song suggested by existing circumstances, but with

The life of the ship was an Englishman, with the fresh complexion almost invariably seen upon Englishmen, and forty years upon a head that looked twenty-five. He was going home after a short tour through the United States, with his mind as full of prejudices as his memorandum-book was of notes. He chanced, oddly enough, to room with the genuine Yankee of the company—a long, lean, good-natured individual from one of the eastern states, "close on ter Varmont," who had a way of rolling his eyes fearfully, especially when he glared at his food. He represented a mowing machine company, and we called him "the Mowing Machine Man." He accosted us one day, sidling up to our door, with, "How d'ye do to-day?"

"Better, thank you," I replied from the sofa.[19]

"That's real nice. Tell ye what, we'll be glad to see the ladies out. How's yer mar?" nodding towards the berth from which twinkled Mrs. K.'s eyes. I laughed, and explained that our relations were of affection rather than consanguinity. His interest increased when he found we were travelling alone. He gave us his London address, evidently considering us in the light of Daniels about to enter the lions' den. "Ef ye have any trouble," said he, as he wrote down the street and number, "there's one Yankee'll stand up for ye." He amused the Englishman by calling out, "Hullo. D'ye feel good this morning?" "No," would be the reply, with a burst of laughter; "I feel awful wicked; think I'll go right out and kill somebody."

There was a shout one morning, "A sail! See the stars and stripes!" I had not raised my head for days, but staggered across the floor at that, and clinging to the frame, thrust my head out of the window. Yes, there was a ship close by, with the stars and stripes floating from the mast-head, I found, when the roll of the steamer carried my window to its level. "Seems good ter see the old rag!" I looked up to find the Mowing Machine Man gazing upon it with eyes all afloat. "I'd been a thinking," said he, "all them fellers have got somebody waiting for 'em over there,"—our passengers were mostly English,—"but there wasn't nobody a waiting for me. Tell ye what,"—and he shook out the folds of a red and yellow handkerchief,—"it does my heart good ter see the old flag." There was a bond of sympathy between us from that moment.

We had another and less agreeable specimen of[20] this free people—a tall, tough western cattle dealer, who quarrelled if he could find an antagonist, swore occasionally, drank liquor, and chewed tobacco perpetually, wore his trousers tucked into his long boots, his hands tucked into his pockets, and, to crown these attributes, believed in Andrew Johnson!—a middle-aged man, with soft, curling brown hair above a face that could be cruelly cold and hard. His hair should have been wire; his blue eyes were steel. But hard as was his face, it softened and smoothed itself a little at sight of the sick women. He paused beside us one day with a rough attempt to interest and amuse by displaying a knife case containing a dozen different articles. "This is ter take a stun out of a hoss's huf, and this, d'ye see, is a tooth-pick;" putting it to immediate use by way of explanation. At the table he talked long and loud upon the rinderpest, and other kindred and appetizing topics. "I've been a butcher myself," he would say. "I've cut up hundreds o' critters. What part of an ox, now, d'ye think that was taken from?" pointing to the joint before him, and addressing a refined, delicate-faced old gentleman across the table, who only stared in silent horror.

But even the "Cattle Man" was less marked in his peculiarities than the "Jersey Man," a melancholy-eyed, curly-wigged individual from the Jersey shore, who wore his slouched hat upon one side of his head, and looked as though he were doing the rakish lover in some fifth-rate theatre; who was "in the musical line myself; Smith and Jones's organs, you know; that's me;" and who, being neither Smith nor Jones, we naturally concluded must be the organ. He recited[21] poetry in a loud tone at daybreak, and discussed politics for hours together, arguing in the most satisfactory manner with the principles, and standing most willingly upon the platform, of everybody. He assumed a patronizing air towards the Mowing Machine Man. "Well, you are a green Yankee," he would say; "lucky for you that you fell in with me;" to which the latter only chuckled, "That's so." He had much to tell of himself, of his grandmother, and of his friends generally, who came to see him off; "felt awfully, too," which we could hardly credit; rolled out snatches of sentimental songs, iterating and reiterating that his bark was on the sea,—and a most disagreeable one we found it; wished we had a piano on board, to which we murmured, "The Lord forbid;" and hoped we should soon be well enough to join him in the "White Squall." He was constantly reminding us that we were a very happy family party, so "congenial," and evidently agreed with the Mowing Machine Man, who said, "They're the best set of fellows I ever see. They'll tell ye anything."

We numbered a clergyman among us, of course. "Always a head wind when there's a parson aboard," say the sailors. So this poor dyspeptic little man bore the blame of our constant adverse winds. Nothing more bigoted, more fanatical than his religious belief could be imagined. You read the terrors of the Lord in his eye; and yet he won respect, and something more, by his consistency and zeal. Earnestness will tell. "The parson will have great influence over the Cattle Man," the captain said, Sabbath morning, as we were walking the deck. "The Cattle Man?"[22] "Yes, the parson will get a good hold of him." Just then, as if to prove the old proverb true, that his satanic majesty is always in the immediate neighborhood when his character is under discussion, the Cattle Man and Jersey came up the companion-way. "If you please, captain," said the former, "we are a committee to ask if the parson may preach to the steerage people to-night." "Certainly," was the reply; "I will attend myself." They thanked him, and went below, leaving me utterly amazed. They were the last men upon the ship whom one would have selected as a committee upon spiritual things!

The church service for the cabin passengers was held in the saloon. A velvet cushion upon one end of the long table constituted the pulpit, before which the minister stood, holding fast to the rack on either side, and bracing himself against the captain's chair in the rear. Even then he made, involuntarily, more bows than any ritualist, and the scripture, "What went ye out for to see? A reed shaken by the wind?" would present itself. The sailors in their neat dress filed in and ranged themselves in one corner. The stewards gathered about the door, one, with face like an owl, most conspicuous. The passengers filled their usual seats, and a delegation from the steerage crept shyly into the unoccupied space—women with shawls over their heads and babies in their arms, shock-headed men and toddling children, but all with an evident attempt at appropriate dress and manner. Among them was one sweet young English face beneath an old crape bonnet. A pair of shapely hands, which the shabby black gloves could not disguise, held fast a little[23] child. Widowhood and want in the old world; what was waiting her in the new? The captain read the service, and all the people responded. The women's eyes grew wet at the sound of the familiar words. The little English widow bent her face over the head of the child in her lap, and something glistened in its hair. Our sympathies grew wide, and we joined in the prayer for the queen, that she might have victory over her enemies, and even murmured a response to the petition for Albert Edward and the nobility, dimly conscious that they needed prayers. The good captain added a petition for the president of the United States, to which the Mowing Machine Man and I said, "Amen." Then the minister, having poised himself carefully, read a discourse, sulphurous but sincere; the Mowing Machine Man thrusting his elbow into my side in a most startling manner at every particularly blue point. We were evidently in sympathy; but I could have dispensed with the expression of it. We closed with the doxology, standing upon our feet and swaying back and forth as though it had been a Shaker chant, led by an improvised choir and the Jersey Man.

At night we descended into the depths of the steamer to worship with the steerage passengers. It was like one of Rembrandt's pictures—the darkness, the wild, strangely-attired people, the weird light from the lanterns piercing the gloom, and bringing out group after group with fearful distinctness; the pale, earnest face of the preacher, made almost unearthly by the glare of the yellow light—a face with its thin-drawn lips, its eyes like coals of fire such as the flames of martyrdom lit[24] once, I imagine. Close beside him stood the Cattle Man, towering like Saul above the people, and with an air that plainly said, "Beware—I stand by the parson."

But the record of all these days would have no end. How can I tell of the long, happy hours, when more[25] than strength, when perfect exhilaration, came to us; when existence alone was a delight? To sit upon the low wheel-house, with wraps and ribbons and hair flying in the wind, while we sang,—

One morning, when the land seemed a forgotten dream, we awoke to find green Erin close beside us. All the day before the sea-gulls had been hovering over us—beautiful creatures, gray above and white beneath, clouds with a silver lining. Tiny land birds, too, flew about us, resting wearily upon the rigging. The sea all at once became like glass. It seemed like the book of Revelation when the sun shone on it,—the sea of glass mingled with fire. For a time the land was but a line of rock, with martello towers perched upon the points. On the right, Fastnet Rock rose out of the sea, crowned with a light-house; then the gray barren shore of Cape Clear Island, and soon the sharp-pointed Stag Rocks. It is a treacherous coast. "I've been here many a night," said the captain, as he gave us his glass, "when I never expected to see[26] morning." And all the while he was speaking, the sea smiled and smiled, as though it could never be cruel.

We drew nearer and nearer, until we could see the green fields bounded by stone walls, the white, winding roads, and little villages nestling among the hills. Towards noon the lovely harbor of Queenstown opened before us, surrounded and almost shut in by rocky islands. Through the glass we could see the city, with its feet in the bay. We were no longer alone. The horizon was dotted with sails. Sometimes a steamer crossed our wake, or a ship bore down upon us. We hoisted our signals. We dipped our flag. The sailors were busy painting the boats, and polishing the brass till it shone again. Now the tender steams out from Queenstown. The steerage passengers in unwonted finery, tall hats and unearthly bonnets, and one in a black silk gown, are running about forward, shaking hands, gathering up boxes and bundles, and pressing towards the side which the tender has reached. There are the shouting of orders, the throwing of a rope, and in a moment they are crowding the plank. One long cheer, echoed from the stern of our steamer, and they are off.

All day we walked the deck; even the sick crawled up at last to see the panorama. We still lingered when night fell, and we had turned away from the land to strike across the channel, and the picture rests with me now; the purple sky with one long stretch of purple, hazy cloud, behind which the sun went down; the long, low line of purple rock, our last glimpse of Ireland, and the shining, purple sea, with not a ripple upon its surface.

The Mersey tender (a tender mercy to some) puffed out to meet us, and we descended the plank as those who turn away from home, leaving much of our thoughts, and something of our hearts, within the ship. It had been such a place of rest, of blessed idleness! Only when our feet touched the wharf did we take up the burden of life again. There were the meeting of friends, in which we had no part; the maelstrom of horses, and carts, and struggling humanity, in which we found a most unwilling place; and then we followed fast in the footsteps of the Mowing Machine Man, who in his turn followed a hair-covered trunk upon the shoulders of a stout porter, our destination the custom-house shed close by. For a moment, as we were tossed hither and thither by the swaying mass, our desires followed our thoughts to a certain sheltered nook, upon a still, white deck, with the sunbeams slanting down through the furled sails above, with the lazy, lapping sea below, and only our own idle thoughts for company. Then we remembered Lot's wife.[29]

There was a little meek-faced custom-house officer in waiting, with a voice so out of proportion to his size, that he seemed to have hired it for the occasion, or come into it with his uniform by virtue of his office. "Any tobacco?" he asked, severely, as we lifted the lid of our one trunk. We gave a virtuous and indignant negative. That was all. We might go our several ways now unmolested. One fervent expression of good wishes among our little company, while we make for a moment a network of clasped hands, and then we pass out of the great gates into our new world, and into the clutches of the waiting cabmen. By what stroke of good fortune we and our belongings were consigned to one and the same cab, in the confusion and terror of the moment, we did not know at the time. It was clearly through the intervention of a kind fellow-passenger, who, seeing that amazement enveloped us like a garment, kindly took us in charge. The dazed, as well as the lame and lazy, are cared for, it seems. By what stroke of good fortune we ever reached our destination, we knew still less. Our cab was a triumph of impossibilities, uncertainties, and discomfort. Our attenuated beast, like an animated hoop skirt, whose bones were only prevented, by the encasing skin, from flying off as we turned the corners, experienced hardly less difficulty in drawing his breath than in drawing his load. We descended at the entrance to the hotel as those who have escaped from imminent peril. We mounted the steps—two lone, but by no means lorn, damsels, two anxious, but by no means aimless females, knowing little of the world, less of travelling, and nothing whatever of foreign ways. Our[30] very air, as we entered the door, was an apology for the intrusion.

"Names, please," said the smiling man in waiting, opening what appeared to be the book of fate. We added ours to the long list of pilgrims and strangers who had sojourned here, dotting our i's and crossing our t's in the most elegant manner imaginable. If any one has a doubt as to our early advantages, let him examine the record of the Washington Hotel, Liverpool. The heading, "Remarks," upon the page, puzzled us. Were they to be of a sacred or profane nature? Of an autobiographical character? Were they to refer to the dear land we had just left? Through some political throes she had just brought forth a ruler. Should we add to the U. S. against our names, "As well as could be expected"? We hesitated,—and wrote nothing. Up the wide stairs, past the transparency of Washington—in the bluest of blue coats, the yellowest of top boots, and an air of making the best of an unsought and rather ridiculous position—we followed the doily upon the head of the pretty chambermaid to our wide, comfortable room, with its formidable, high-curtained beds. The satchels and parcels innumerable were propped carefully into rectitude upon the dressing table, under the impression that the ship would give a lurch; and then, gazing out through the great plate glass windows upon the busy square below, we endeavored to compose our perturbed minds and gather our scattered wits.

It is not beautiful, this great city of Liverpool, creeping up from the sea. It has little to interest a stranger aside from its magnificent docks and warehouses.[31] There are mammoth truck horses from Suffolk, with feet like cart wheels; there is St. George's Hall, the pride of the people, standing in the busy square of the same name, with a statue of the saint himself—a terror to all dragons—just before it. It is gray, many columned, wide stepped, vast in its proportions. Do you care for its measurement? Having seen that, you are ready to depart; and, indeed, there is nothing to detain one here beyond a day of rest, a moment to regain composure after the tossing of the sea. There are some substantial dwellings,—for commerce has its kings,—and some fine shops,—for commerce also has its queens,—and one fine drive, of which we learned too late. The air of endurance, which pervades the whole city, as it does all cities in the old world, impresses one greatly, as though they were built for eternity, not time; the founders having forgotten that here we are to have no continuing city. In the new world, man tears down and builds up. Every generation moulds and fashions its towns and cities after its own desires, or to suit its own means. Man is master. In the old world, one generation after another surges in and out of these grim, gray walls, leaving not so much as the mark the waves leave upon the rocks. Unchanged, unchanging, they stand age after age, time only softening the hard outlines, deepening the shadows it has cast upon them, and so bringing them into a likeness of each other that they seem to have been the design of one mind, the work of one pair of hands, and hardly of mortal mind or hands at that. They seem to say to man, "We have stood here ages before you were born. We shall stand here ages after you are forgotten."[32] They must be filled with echoes, with ghosts, and haunting memories.

Bold Street, a tolerably narrow and winding way, in which many are found to walk,—contrary to all precedent,—boasts the finest shops. Here the Lancashire witches, as the beauties of the county are called, walk, and talk, and buy gewgaws of an afternoon. It was something strange to us to see long silken skirts entirely destitute of crinoline, ruffle, or flounce, trailed here through mud and mire, or raised displaying low Congress gaiters, destitute of heels. For ourselves, if we had been the king of the Cannibal Islands, we could hardly have attracted more attention than we did in our plain, short travelling suits and high-heeled boots. It grew embarrassing, especially when our expression of unqualified benevolence drew after us a train of beggars. They crossed the street to meet us. They emerged from every side street and alley, thrusting dirty hands into our faces, and repeating twice-told tales in our ears, until we were thankful when oblivion and the shadow of the hotel fell upon us.

We dined in the coffee-room,—that comfortable and often delightfully cosy apartment fitted with little tables, and with its corner devoted to books, to papers and conversation,—that combination of dining, tea and reading-room unknown to an American hotel,—sacred to the sterner sex from all time, and only opened to us within a few years,—the gates being forced then, I imagine, by American women, who will not consent to hide their light under a bushel, or keep to some faraway corner, unseeing and unseen. English women,[33] as a rule, take their meals in their own private parlors. Perhaps because English men generally desire the flowers intrusted to their fostering care to blush unseen. It may be better for the gardeners; it may be better for the flowers—I cannot tell; but we dined in the coffee-room, as Americans usually do. One of the clergymen, who attend at such places, received our order. It was not so very formidable an affair, after all, this going down by ourselves; or would not have been, if the big-eyed waiter, who watched our every movement, would have left us, and the military man at the next table, who showed "the purple tide of war," or something else, in his face, and blew his nose like a trombone, ceased to stare. As it was, we aired our most elegant table manners. We turned in our elbows and turned out our toes,—so to speak,—and ate our mutton with a grace that destroyed all appetite. We tried to appear as though we had frequently dined in the presence of a whole battalion of soldiery, under the scrutiny of innumerable waiters,—and failed, I am sure. "With verdure clad" was written upon every line of our faces. The occasion of this cross fire we do not know to this day. Was it unbounded admiration? Was it spoons?

Having brushed off the spray of the sea, having balanced ourselves upon the solid earth, having seen St. George's Hall, there was nothing to detain us longer, and the next morning we were on our way to London. We had scrutinized our bill,—which might have been reckoned in pounds, ounces, and penny-weights, for aught we knew to the contrary,—and informed the big-eyed waiter that it was correct. We[34] had also offered him imploringly our largest piece of silver, which he condescended to accept; and having been presented with a ticket and a handful of silver and copper by the porter who accompanied us to the station across the way, in return for two or three gold pieces, we shook off the dust of Liverpool from our feet, turned our eyes from the splendors of St. George's Hall, and set our faces steadfastly towards our destination. There was a kind of luxury, notwithstanding our prejudices, in this English railway carriage, with its cushions all about us, even beneath our elbows; a restfulness unknown in past experience of travel, in the ability to turn our eyes away from the flying landscape without, to the peaceful quiet, never intruded upon, within. We did not miss the woman who will insist upon closing the window behind you, or opening it, as the case may be. Not one regret had we for the "B-o-s-t-o-n papers!" nor for the last periodical or novel. The latest fashion gazette was not thrown into our lap only to be snatched away, as we became interested in a plan for rejuvenating our wardrobe; nor were we assailed by venders of pop corn, apples, or gift packages of candy. Even the blind man, with his offering of execrable poetry, was unknown, and the conductor examined our tickets from outside the window. Settling back among our cushions, while we mentally enumerated these blessings of omission, there came a thought of the perils incurred by solitary females locked into these same comfortable carriages with madmen. If the danger had been so great for one solitary female, what must it be for two, we thought with horror. We gave a quick glance at our[35] fellow-passenger, a young man with hair all aflame. Certainly his eyes did roll at that moment, but it was only in search of a newsboy; and when he exclaimed, like any American gentleman, "Hang the boy!" we became perfectly reassured. He proved a most agreeable travelling companion. We exchanged questions and opinions upon every subject of mutual interest, from the geological formation of the earth to the Alabama claims. I can hardly tell which astonished us most, his profound erudition or our own. Now, I have not the least idea as to whether Lord John Russell sailed the Alabama, or the Alabama sailed of itself, spontaneously; but, whichever way it was, I am convinced it was a most iniquitousiniquitous proceeding, and so thought it safe to take high moral ground, and assure him that as a nation we could not allow it to go unpunished. You have no idea what an assistance it is, when one is somewhat ignorant and a good deal at a loss for arguments, to take high moral ground.

When we were weary of discussion, when knowledge palled upon our taste, we pulled aside the little blue curtain, and gave ourselves up to gazing upon the picture from the window. I doubt if any part of England is looked upon with more curious eyes than that lying between Liverpool and London. It is to so many Americans the first glimpse of strange lands. Spread out in almost imperceptible furrows were the velvet turfed meadows, the unclipped hedges a mass of tangled greenness between. For miles and miles they stretched away, with seldom a road, never a solitary house. The banks on either side were tufted with broom and yellow with gorse; the hill-sides in the[36] distance, white with chalk, or black with the heather that would blossom into purple beauty with the summer. We rushed beneath arches festooned, as for a gala-day, with hanging vines. Tiny gardens bloomed beside the track at every station, and all along the walls, the arched bridges, and every bit of stone upon the wayside, was a mass of clinging, glistening ivy. Not the half-dead, straggling thing we tend and shield so carefully at home, with here and there a leaf put forth for very shame. These, bright, clear-cut, deep-tinted, crowded and overlapped each other, and ran riot over the land, transforming the dingy, mildewy cottages, bits of imperishable ugliness, into things of beauty, if not eternal joys. Not in the least picturesque or pleasing to the eye were these English villages; straggling rows of dull red brick houses set amidst the fields—dirty city children upon a picnic—with a foot square garden before each door, cared for possibly, possibly neglected. A row of flower-pots upon the stone ledge of every little window, a row of chimney-pots upon the slate roof of every dwelling. Sometimes a narrow road twisted and writhed itself from one to another, edged by high brick walls, hidden beneath a weight of ivy; sometimes romantic lanes, shaded by old elms, and green beyond all telling. The towns were much the same,—outgrown villages. And the glimpse we caught, as we flew by, so far above the roofs often that we could almost peep down upon the hearths through the chimney tops, was by no means inviting.

Dusk fell upon us with the smoke, and mist, and drizzling rain of London, bringing no anxiety; for was there[37] not, through the thoughtfulness of friends, a place prepared for us? Our pleasant acquaintance of the golden locks forsook his own boxes, and bundles, and innumerable belongings to look for our baggage, and saw us safely consigned to one of the dingy cabs in waiting. I trust the people of our own country repay to wanderers there something of the kindness which American women, travelling alone, receive at the hands of strangers abroad. It was neither the first nor the last courtesy proffered most respectfully, and received in the spirit in which it was offered. There is a deal of nonsense in the touch-me-not air with which many go out to see the world, as there is a deal of folly in the opposite extreme. But these acquaintances of a day, the opportunity of coming face to face with the people in whose country you chance to be, of hearing and answering their strange questions in regard to our government, our manners and customs, as well as in displaying our own ignorance in regard to their institutions, in giving information and assistance when it is in our power, and in gratefully receiving the same from others,—all this constitutes one of the greatest pleasures of journeying.

Our peace of mind received a rude shock, when, after rattling over the pavings around the little park in Queen's Square, and pulling the bell at Mr. B.'s boarding-house, we found that we were indeed expected, but indefinitely, and no place awaited us. We had forgotten to telegraph. It was May, the London season, and the hotels full. "X. told us you were coming," said the most lady-like landlady, leading us into the drawing-room from the dank darkness[38] of the street. There was a glow of red-hot coals in the grate, a suggestion of warmth and comfort in the bright colors and cosy appointments of the room—but no place for us. "I'm very sorry; if you had telegraphed—but we can take you by Monday certainly," she said. I counted my fingers. Two days. Ah! but we might perish in the streets before that. Everything began to grow dark and doleful in contemplation. Some one entered the room. The landlady turned to him: "O, here is the good man to whose care you were consigned by X." We gave a sigh of relief, as we greeted the Good Man, for all our courage, like the immortal Bob Acres's, had been oozing from our finger ends. And if we possess one gift above another, it is an ability to be taken care of. "Do you know X.?" asked another gentleman, glancing up from his writing at the long, red-covered table. "We travelled with him," nodding towards his daughter, whose feet touched the fender, "through Italy, last winter." "Indeed—"

"I'll just send out to a hotel near by," interrupted kind Mrs. B., "and see if you can be accommodated a day or two." How very bright the room became! The world was not hollow, after all, nor our dolls stuffed with sawdust. Even the cabman's rattle at the knocker, and demand of an extra sixpence for waiting, could not disturb our serenity. The messenger returned. Yes; we could be taken in (?) at the H. house; and accepting Mrs. B.'s invitation to return and spend the evening, we mounted to our places in the little cab, as though it had been a triumphal car, and were whizzed around the corner at an alarming pace by the impatient cabman.[39]

I should be sorry to prejudice any one against the H. house—which I might perhaps say is not the H. house at all; I hardly like to compare it to a whited sepulchre, though that simile did occur to my mind. Very fair in its exterior it was, with much plate glass, and ground glass, and gilding of letters, and shining of brass. It had been two dwelling-houses; it was now one select family hotel. But the two dwelling-houses had never been completely merged into one; never married, but joined, like the Siamese twins. There was a confusing double stairway; having ascended the right one, you were morally certain to descend the wrong. There was a confusing double hall, with doors in every direction opening everywhere but upon the way you desired to go. We mounted to the top of the house, followed by two porters with our luggage, one chambermaid with the key, another to ask if we would dine, and two more bearing large tin cans of hot water. We grew confused, and gasped, "We—we believe we don't care for any more at present, thank you," and so dismissed them all. The furniture was so out of proportion to the room that I think it must have been introduced in an infant state, and grown to its present proportions there. The one window was so high that we were obliged to jump up to look out over the mirror upon the bureau—a gymnastic feat we did not care to repeat. The bed curtains were gray; indeed there was a gray chill through the whole place. We sat down to hold a council of war. We resolved ourselves into a committee of ways and means, our feet upon the cans of hot water. "Pleasant," I said, as a leading remark, my heart beginning[40] to warm under the influence of the hot water. "Pleasant?" repeated Mrs. K.; "it's enough to make one homesick. We can't stay here." "But," I interposed, "suppose we leave here, and can't get in anywhere else?" A vision of the Babes in the Wood rose before me. There was a rap at the door; the fourth chambermaid, to announce dinner. We finished our consultation hurriedly, and descended to the parlor, where we were to dine. It was a small room, already occupied by a large table and a party from the country; an old lady to play propriety, a middle-aged person of severe countenance to act it, and a pair of incipient and insipid lovers. He was a spectacled prig in a white necktie, a clergyman, I suppose, though he looked amazingly like a waiter, and she a little round combination of dimples and giggle.

He. "Have you been out for a walk this morning?"

She. "No; te-he-he-he."

He. "You ought to, you know."

She. "Te-he-he-he—yes."

He. "You should always exercise before dinner."

She. "Te-he-he-he."

Here the words gave out entirely, and, it being remarkably droll, all joined in the chorus. "We must go somewhere else, if possible," we explained to Mrs. B., when, a little later, we found our way to her door. "At least we shall be better contented if we make the attempt." The Good Man offered his protection; we found a cab, and proceeded to explore the city, asking admittance in vain at one hotel after another, until at last the Golden Cross upon the Strand, more charitable[41] than its neighbor, or less full, opened its doors, and the good landlady, of unbounded proportions, made us both welcome and comfortable. Quite palatial did our neat bed-room, draped in white, appear. We were the proud possessors, also, of a parlor, with a round mirror over the mantel, a round table in the centre, a sofa, of which Pharaoh's heart is no comparison as regards hardness, a row of stiff, proper arm-chairs, and any amount of ornamentation in the way of works of art upon the walls, and shining snuffers and candlesticks upon the mantel. Our bargain completed, there remained nothing to be done but to remove our baggage from the other house, which I am sure we could never have attempted alone. Think of walking in and addressing the landlady, while the chambermaids and waiters peeped from behind the doors, with, "We don't like your house, madam. Your rooms are tucked up, your beds uninviting, your chambermaids frowsy, your waiters stupid, and your little parlor an abomination." How could we have done it? The Good Man volunteered. "But do you not mind?" "Not in the least." Is it not wonderful? How can we believe in the equality of the sexes? In less than an hour we were temporarily settled in our new quarters, our rescued trunks consigned to the little bed-room, our heart-felt gratitude in the possession of the Good Man.

We took our meals now in our own parlor, trying the solitary confinement system of the English during our two days' stay. It seemed a month. Not a sign of life was there, save the landlady's pleasant face behind the bar and the waiter who answered our bell, with the exception of a pair of mammoth shoes before the next[42] door, mornings, and the bearded face of a man that startled us, once, upon the stairs. And yet the house was full. It was a relief when our two days of banishment Mere over, when in Mrs. B.'s pretty drawing-room, and around her table, we could again meet friends, and realize that we were still in the world.

For two busy weeks we rattled over the flat pavings of the city in the low, one-horse cabs. We climbed towers, we descended into crypts, we examined tombstones,[44] we gazed upon mummies. Everything was new, strange, and wonderful, even to the little boys in the street, who, as well as the omnibus drivers, were decked out in tall silk hats—a piece of absurdity in one case, and extravagance in the other, to our minds. The one-horse carriages rolled about upon two wheels; the occupants, like cross children, facing in every direction but the one they were going, and everybody, contrary to all our preconceived ideas of law and order, turned to the left, instead of to the right,—to say nothing of other strange and perplexing ways that came under our observation. We had come abroad upon the same errand as the bears who "went over to Charlestown to see what they could see," and so stared into every window, into every passing face, as though we were seeking the lost. We became known as the women who wanted a cab; our appearance within the iron posts that guard the entrance to Queen's Square from Southampton Row being the signal for a perfect Babel of unintelligible shouts and gesticulations down the long line of waiting vehicles, with the charging down upon us of the first half dozen in a highly dangerous manner. Wisdom is sometimes the growth of days; and we soon learned to dart out in an unexpected moment, utterly deaf and blind to everything and everybody but the first man and the first horse, and thus to go off in triumph.

But if our exit was triumphant, what was our entry to the square, when weary, faint with seeing, hearing, and trying in vain to fix everything seen and heard in our minds, we returned in a hansom! English ladies do not much affect this mode of conveyance, but American[45] women abroad have, or take, a wide margin in matters of mere conventionality,—and so ride in hansom cabs at will. They are grown-up baby perambulators upon two wheels; the driver sitting up behind, where the handle would be, and drawing the reins of interminable length over the top of the vehicle. Picture it in your mind, and then wonder, as I did, what power of attraction keeps the horse upon the ground; what prevents his flying into the air when the driver settles down into his seat. A pair of low, folding doors take the place of a lap robe; you dash through the street at an alarming rate without any visible guide, experiencing all the delights of a runaway without any of its dangers.

A ride by rail of half an hour takes one to Sydenham. It is a charming walk from the station through the tastefully arranged grounds, with their shrubberies, roseries, and fountains, along the pebble-strewn paths, crowded this day with visitors. The palace itself is so like its familiar pictures as to need no description. Much of the grandeur of its vast proportions within is lost by its divisions and subdivisions. There are courts representing the various nations of the earth,—America, as usual, felicitously and truthfully shown up by a pair of scantily attired savages under a palm tree; there are the courts of the Alhambra, of Nineveh, and of Pompeii; there are fountains, and statues, and bazaars innumerable, where one may purchase almost anything as a souvenir; there are cafés where one may refresh the body, and an immense concert[46] hall where one may delight the soul,—and how much more I cannot tell, for the crowd was almost beyond belief, and a much more interesting study than Egyptian remains, or even the exquisite mass of perfumed bloom, that made the air like summer, and the whole place a garden. They were of the English middle class, the upper middle class, bordering upon the nobility,—these rotund, fine-looking gentlemen in white vests and irreproachable broadcloth, these stout, red-faced, richly-attired ladies, with their soft-eyed, angular daughters following in their train, or clinging to their arms. We listened for an hour to the queen's own band in scarlet and gold, and then came back to town, meeting train after train filled to overflowing with expensively arrayed humanity in white kids, going out for the evening.

It was Whit-Monday,—the workingman's holiday,—a day of sun and shower; but we took our turn upon the outside of the private omnibus chartered for the occasion, unmindful of the drops; our propelling power, six gray horses. By virtue of this private establishment we were free to pass through Hyde Park,—that breathing-place of aristocracy, where no public vehicle, no servant without livery, is tolerated. It was early, and only the countless hoof-prints upon Rotten Row suggested the crowd of wealth and fashion that would throng here later in the day. One solitary equestrian there was; perched upon a guarded saddle, held in her place by some concealed band, serenely content, rode a queen baby in long, white robes. A[47] groom led the little pony. She looked at us in grave wonder as we dashed by,—born to the purple! I cannot begin to describe to you the rising up of London for this day of pleasure; the decking of itself out in holiday attire; the garnishing of itself with paper flowers; the smooth, hard roads leading into the country, all alive; the drinking, noisy crowd about the door of every pot-house along the way. It was a delightful drive of a dozen or more miles, through the most charming suburbs imaginable,—past lawns, and gardens, and green old trees shading miniature parks; past "detached" villas that had blossomed into windows; indeed, the plate glass upon houses of most modest pretension was almost reckless extravagance in our eyes, forgetting, as we did, the slight duty to be paid here upon what is, with us, an expensive luxury. No wonder the English are a healthful people,—the sun shines upon them. I like their manner of house-building, of home-making. They set up first a great bay-window, with a room behind it, which is of secondary importance, with wide steps leading up to a door at the side. They fill this window with the rarest, rosiest, most rollicksome flowers. Then, if there remain time, and space, and means, other rooms are added, the bay-windows increasing in direct proportion; while shades, drawn shades, are a thing unknown. "But the carpets?" They are so foolish as to value health above carpets.

It was high noon when we rolled up the wide avenue of Bushey Park, with its double border of gigantic chestnuts and limes, through Richmond Park, with its vast sweep of greensward flecked with the sunbeams,[48] dripping like the rain through the royal oaks, past Richmond terrace, with its fine residences looking out upon the Thames, the translucent stream, pure and beautiful here, before going down to the city to be defiled—like many a life. We dismounted at the gates to the palace, in the rambling old village that clings to its skirts, and joined the crowd passing through its wide portals.

It is an old palace thrown aside, given over to poor relatives, by royalty,—as we throw aside an old gown; a vast pile of dingy, red brick that has straggled over acres of Hampton parish, and is kept within bounds by a high wall of the same ugly material. It has pushed itself up into towers and turrets, with pinnacles and spires rising from its battlemented walls. It has thrust itself out into oriel and queer little latticed windows that peep into the gardens and overhang the three quadrangles, and is with its vast gardens and park, with its wide canal and avenues of green old trees, the most delightfully ugly, old place imaginable. Here kings and queens have lived and loved, suffered and died, from Cardinal Wolsey's time down to the days of Queen Anne. It is now one of England's show places; one portion of its vast extent, with the grounds, being thrown open to the public, the remainder given to decayed nobility, or wandering, homeless representatives of royalty,—a kind of royal almshouse, in fact. A curtained window, the flutter of a white hand, were to us the only signs of inhabitation.

Through thirty or more narrow, dark, bare rooms,—bare but for the pictures that crowded the walls,—we wandered. There were two or three halls of stately[49] proportions finely decorated with frescoes by Verrio, and one or two royal stairways, up and down which slippered feet have passed, silken skirts trailed, and heavy hearts been carried, in days gone by. The pictures are mostly portraits of brave men and lovely women, of kings and queens and royal favorites,—poor Nell Gwynne among them, who began life by selling oranges in a theatre, and ended it by selling virtue in a palace. The Vandyck faces are wonderfully beautiful. They gaze upon you through a mist, a golden haze,—like that which hangs over the hills in the Indian summer,—from out deep, spiritual eyes; a dream of fair women they are.

There were one or two royal beds, where uneasy have lain the heads that wore a crown, and half a dozen chairs worked in tapestry by royal fingers,—whether preserved for their questionable beauty, or because of the rarity of royal industry, I do not know. We wandered through the shrubberies, paid a penny to see the largest grape vine in the world,—and wished we had given it to the heathen, so like its less distinguished sisters did the vine appear,—and at last lunched at the King's Arms, a queer little inn just outside the gates, edging our way with some difficulty through the noisy, guzzling crowd around the door—the crowd that, having reached the acme of the day's felicity, was fast degenerating into a quarrel. In the long, bare room at the head of the narrow, winding stairs, we found comparative quiet. The tables were covered with joints of beef, with loaves of bread, pitchers of ale, and the ubiquitous cheese. A red-faced young man in tight new clothes—like a strait-jacket—occupied one end[50] of our table with his blushing sweetheart. A band of wandering harpers harped upon their harps to the crowd of wrangling men and blowsy women in the open court below; strangely out of tune were the harps, out of time the measure, according well with the spirit of the hour. A loud-voiced girl decked out in tawdry finery, with face like solid brass, sang "Annie Laurie" in hard, metallic tones,—O Music, how many murders have been committed in thy name!—then passed a cup for pennies, with many a jest and rude, bold laugh. We were glad when the day was done,—glad when we had turned away from it all.

The castle itself is a huge, battlemented structure of gray stone,—a fortress as well as a palace,—with a home park of five hundred acres, the private grounds of Mrs. Guelph, and, beyond that, a grand park of eighteen hundred acres. But do not imagine that she lives here with only her children and servants about her,—this kindly German widow, whose throne was once in the hearts of her people. Royalty is a complicated affair,—a wheel within a wheel,—and reminds us of nothing so much as "the house that Jack built."

This is the Castle of Windsor.

This is the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

These are the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

These are the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

These are the lackeys that wait on the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.[51]

These are the soldiers, tried and sworn, that guard the crown from the unicorn, that stand by the lackeys that wait on the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

These are the "military knights" forlorn, founded by Edward before you were born, that outrank the soldiers, tried and sworn, that guard the crown from the unicorn, that stand by the lackeys that wait on the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

These are the knights that the garter have worn, with armorial banners tattered and torn, that look down on the military knights forlorn, founded by Edward before you were born, that outrank the soldiers, tried and sworn, that guard the crown from the unicorn, that stand by the lackeys that wait on the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

This is the dean, all shaven and shorn, with the canons and clerks that doze in the morn, that install the knights that the garter have worn, with armorial banners tattered and torn, that look down on the military knights forlorn, founded by Edward before you were born, that outrank the soldiers, tried and sworn, that guard the crown from the unicorn, that stand by the lackeys that wait on the pages that bow to the ladies that 'tend on the queen that lives in the Castle of Windsor.

And so on. The train within the castle walls that follows the queen is endless.

We passed through the great, grand, state apartments, refurnished at the time of the marriage of the[52] Prince of Wales, for the use of the Danish family. We mounted to the battlements of the Round Tower by the hundred steps, the grim cannon gazing down upon us from the top. Half a dozen visitors were already there, gathered as closely as possible about the angular guide, listening to his geography lesson, and looking off upon the wonderful panorama of park, and wood, and winding river. Away to the right rose the spire of Stoke Pogis Church, where the curfew still "tolls the knell of parting day." To the left, in the great park below, lay Frogmore, where sleeps Prince Albert the Good. Eton College, too, peeped out from among the trees, its gardens touching the Thames, and in the distance,—beyond the sleeping villages tucked in among the trees,—the shadowy blue hills held up the sky.

St. George's Chapel is in the quadrangle below. It is the chapel of the Knights of the Garter. And now, when you read of the chapels, or churches, or cathedrals in the old world,—and they are all in a sense alike,—pray don't imagine a New England meeting-house with a double row of stiff pews and a choir in the gallery singing "Antioch"! The body of the chapel was a great, bare space, with tablets and elaborate monuments against the walls. Opening from this were alcoves,—also called chapels,—each one containing the tombs and monuments of some family. As many of the inscriptions are dated centuries back, you can imagine they are often quaintly expressed. One old knight, who died in Catholic times, desired an open Breviary to remain always in the niche before his tomb, that passers might read to their comfort, and say for him an orison.[53] Of course this would never do in the days when the chapel fell into Protestant hands. A Bible was substituted, chained into its place; but the old inscription, cut deep in the stone, still remains, beginning "Who leyde thys book here?" with a startling appropriateness of which the author never dreamed. Over another of these chapels is rudely cut an ox, an N, and a bow,—the owner having, in an antic manner, hardly befitting the place, thus written his name—Oxenbow.

You enter the choir, where the installations take place, by steps, passing under the organ. In the chancel is a fine memorial window to Prince Albert. On either side are the stalls or seats for the knights, with the armorial banner of each hanging over his place. Projecting over the chancel, upon one side, is what appears to be a bay-window. This is the queen's gallery, a little room with blue silk hangings,—for blue is the color worn by Knights of the Garter,—where she sits during the service. Through these curtains she looked down upon the marriage of the Prince of Wales. Think of being thus put away from everybody, as though one were plague-stricken. A private station awaits her when she steps from the train at the castle gates. A private room is attached to the green-houses, to the riding-school in the park, and even to the private chapel. A private photograph-room, for the taking of the royal pictures, adjoins her apartments. It must be a fine thing to be a queen,—and so tiresome! Even the gold spoon in one's mouth could not offset the weariness of it all, and of gold spoons she has an unbounded supply; from ten to fifteen millions of dollars worth of gold plate for her majesty's table being guarded within the castle! Think of it, little women who[54] set up house-keeping with half a dozen silver teaspoons and a salt-spoon!

We waited before a great gate until the striking of some forgotten hour, to visit the royal mews. You may walk through all these stables in slippers and in your daintiest gown, without fear. A stiff young man in black—a cross between an undertaker and an incipient clergyman in manner—acted as guide. Other parties, led by other stiff young men, followed or crossed our path. There were stalls and stalls, upon either side, in room after room,—for one could not think of calling them stables,—filled by sleek bays for carriage or saddle. And the ponies!—the dear little shaggy browns, with sweeping tails, and wonderful eyes peeping out from beneath moppy manes, the milk-white, tiny steeds, with hair like softest silk,—they won our hearts. Curled up on the back of one, fast asleep, lay a Maltese kitten; the "royal mew" some one called it. The carriages were all plain and dark, for the ordinary use of the court. In one corner a prim row of little yellow, wicker, baby-wagons attracted our attention, like those used by the poorest mother in the land. In these the royal babies have taken their first airings.

The state equipages we saw another day at Buckingham Palace,—the cream-colored horses, the carriages and harnesses all crimson and gold. There they stand, weeks and months together, waiting for an occasion. The effect upon a fine day, under favoring auspices,—the sun shining, the bands playing, the crowd of gazers, the prancing horses, the gilded chariots,—must almost equal the triumphal entry of a first class circus into a New England town!

"A dozen umbrellas were tipped up; the rain fell fast upon a dozen upturned, expectant faces." Page 57.

"A dozen umbrellas were tipped up; the rain fell fast upon a dozen upturned, expectant faces." Page 57.

To appreciate all this, you should see it—as we did one chilly May morning. We huddled about the stove in the waiting-room upon the site of the old royal menagerie, our companions a round man, with a limp gingham cravat and shabby coat, a little old woman in a poke bonnet, and half a dozen or more schoolboys from the country. A tall Yankee of inquiring mind joined us as we sallied from the door, led by a guide gorgeous in ruff and buckles, cotton velvet and gilt lace, and with all these glories surmounted by a black hat, that swelled out at the top in a wonderful manner. Down the narrow street within the gates, over the slippery cobble-stones, under considerable mental excitement, and our alpaca umbrella, we followed our guide to an archway, before which he paused, and struck an attitude. The long Yankee darted forward. "Stand back, my friends, stand back," said the[57] guide. "You will please form a circle." Immediately a dozen umbrellas surrounded him. He pointed to a narrow window over our heads; a dozen umbrellas were tipped up; the rain fell fast upon a dozen upturned, expectant faces. "In that room, Sir ——" (I could not catch the name) "spent the night before his execution, in solemn meditation and prayer." There was a circular groan of sympathy and approval from a dozen lips, the re-cant of a dozen dripping umbrellas, and we pattered on to the next point of interest, following our leader through pools of blood, figuratively speaking,—literally, through pools of water,—our eyes distended, our cheeks pale with horror. Ah, what treasures of credulity we must have been to the guides in those days! Time brought unbelief and hardness of heart.

We mounted stairs narrow and dark; we descended stairs dark and narrow; we entered chambers gloomy and grim. The half I could not tell—of the rooms filled with war trophies—scalps in the belt of the nation—from the Spanish Armada down to the Sepoy rebellion; the long hall, with its double row of lumbering old warriors encased in steel, as though they had stepped into a steel tower and walked off, tower and all, some fine morning; the armory, with its stacked arms for thirty thousand men. "We may have occasion to use them," said the guide, facetiously, making some reference to the speech of Mr. Sumner, just then acting the part of a stick to stir up the British lion. The Yankee chuckled complacently, and we, too, refused to quake. There was a room filled with instruments of torture, diabolical inventions, recalling the[58] days of the Inquisition. The Yankee expressed a desire to "see how some o' them things worked." Opening from this was an unlighted apartment, with walls of stone, a dungeon indeed, in which we were made to believe that Sir Walter Raleigh spent twelve years of his life. No shadow of doubt would have fallen upon our unquestioning minds, had we been told that he amused himself during this time by standing upon his head. "Walk in, walk in," said the smiling guide, as we peered into its darkness. We obeyed. "Now," said he, "that you may appreciate his situation, I will step out and close the door." The little old woman screamed; the Yankee made one stride to the opening; the guide laughed. It was only a professional joke; there was no door. We saw the bare prison-room, with its rough fireplace, the slits between the stones of the wall to admit light and air, and the initials of Lady Jane Grey, with a host more of forgotten names, upon the walls. Just outside, within the quadrangle, where the grass grew green beneath the summer rain, she was beheaded,—poor little innocent,—who had no desire to be a queen! In another tower close by, guarded by iron bars, were the royal jewels and the crown, for which all this blood was shed—pretty baubles of gold and precious stones, but hardly worth so many lives.

You remember the story of the princes smothered in the Tower by command of their cruel uncle? There was the narrow passage in the wall where the murderers came at night; the worn step by which they entered the great, bare room where the little victims slept; the winding stairs down which the bodies were[59] thrown. Beneath the great stone at the foot they were secretly buried. Then the stairway was walled up, lest the stones should cry out; and no one knew the story of the burial until long, long afterwards—only a few years since—when the walled-up stairway was discovered, the stones at the foot displaced, and a heap of dust, of little crumbling bones, revealed it. A rosy-faced, motherly woman, the wife of a soldier quartered in the barracks here, answered the rap of the guide upon the nail-studded door opening from one of the courts, and told us the old story. "The bed of the princes stood just there," she said, pointing to one corner, where, by a curious coincidence, a little bed was standing now. She answered the question in our eyes with, "My boys sleep there." "But do you not fear that the murderers will come back some night by this same winding way, and smother them?" How she laughed! And, indeed, what had ghosts to do with such a cheery body!

Down through the "Traitors' Gate," with its spiked portcullis, we could see the steps leading to the water. Through this gate prisoners were brought from trial at Westminster. It is said that the Princess Elizabeth was dragged up here when she refused to come of her own will, knowing too well that they who entered here left hope behind. A little later, with music and the waving of banners, and amid the shouts of the people, she rode out of the great gates into the city, the Queen of England.

Though they have stood barely thirty years, already the soft gray limestone begins to crumble away,—the[60] elements, with a sense of the fitness of things, striving to act the part of time, and bring them into a likeness of the adjoining abbey. There is an exquisite beauty in the thousand gilded points and pinnacles that pierce the fog, or shine softly through the mist that veils the city. Ethereal, shadowy, unreal they are, like the spires of a celestial city, or the far away towers and turrets we see sometimes at sunset in the western sky.

Here, you know, are the chambers of the Houses of Lords and Commons, with the attendant lobbies, libraries, committee-rooms, &c., and a withdrawing-room for the use of the queen when she is graciously pleased to open Parliament in person. The speaker of the House of Commons, as well as some other officials, reside here—a novel idea to us, who could hardly imagine the speaker of our House of Representatives taking up his abode in the Capitol! Parliament was not in session, and we walked through the various rooms at will, even to the robing-room of the noble lords, where the peg upon which Lord Stanley hangs his hat was pointed out; and very like other pegs it was. At one end of the chamber of the House of Lords is the throne. It is a simple affair enough—a gilded arm-chair on a little platform reached by two or three steps, and with crimson hangings. Extending down on either side are the crimson-cushioned seats without desks. In the centre is a large square ottoman,—the woolsack,—which might, with equal appropriateness, be called almost anything else. Above, a narrow gallery offers a lounging-place to the sons and friends of the peers; and at one end, above the throne, is a high loft, a kind of uplifted amen corner, for strangers, with a space where[61] women may sit and look down through a screen of lattice-work upon the proceedings below. It seems a remnant of Eastern customs, strangely out of place in this Western world, and akin to the shrouding of ourselves in veils, like our Oriental sisters. Or can it be that the noble lords are more keenly sensitive to the distracting influence of bright eyes than other men?

Adjoining the Houses of Parliament is this vast old hall. For almost five hundred years has it stood, its curiously carved roof unsupported by column or pillar. Here royal banquets, as well as Parliaments, have been held, and more than one court of justice. Here was the great trial of Warren Hastings. It was empty now of everything but echoes and the long line of statuary on either side, except the lawyers in their long, black gowns, who hastened up and down its length, or darted in and out the three baize doors upon one side, opening into the Courts of Chancery, Common Pleas, and the Exchequer. Our national curiosity was aroused, and we mounted the steps to the second, which had won our sympathies from its democratic name.