The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rough Translation, by Jean M. Janis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Rough Translation Author: Jean M. Janis Illustrator: Hunter Release Date: April 14, 2010 [EBook #31980] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROUGH TRANSLATION *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

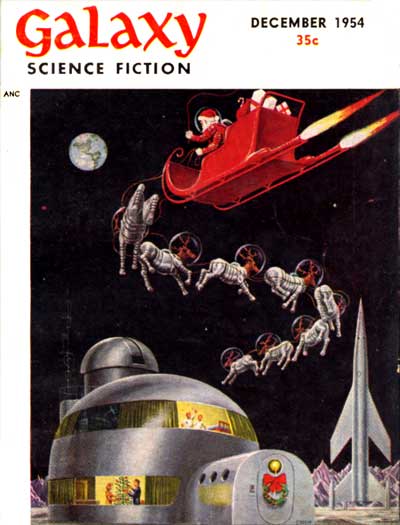

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction December 1954. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

Don't be ashamed if you can't blikkel any more. It's because you couldn't help framishing.

hurgub," said the tape recorder. "Just like I told you before, Dr. Blair, it's krandoor, so don't expect to vrillipax, because they just won't stand for any. They'd sooner framish."

"Framish?" Jonathan heard his own voice played back by the recorder, tinny and slightly nasal. "What is that, Mr. Easton?"

"You know. Like when you guttip. Carooms get awfully bevvergrit. Why, I saw one actually—"

"Let's go back a little, shall we?" Jonathan suggested. "What does shurgub mean?"

There was a pause while the machine hummed and the recorder tape whirred. Jonathan remembered the look on Easton's face when he had asked him that. Easton had pulled away slightly, mouth open, eyes hurt.

"Why—why, I told you!" he had shouted. "Weeks ago! What's the matter? Don't you blikkel English?"

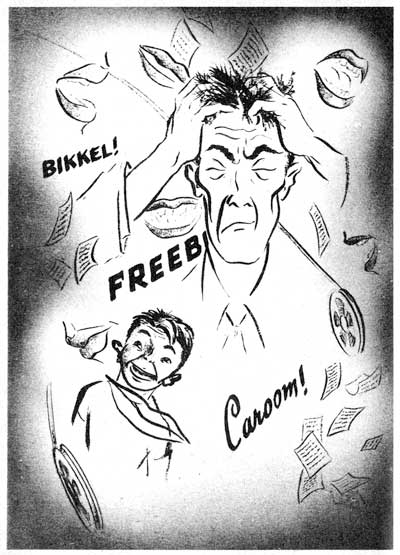

Jonathan Blair reached out and snapped the switch on the machine. Putting his head in his hands, he stared down at the top of his desk.

You learned Navajo in six months, he reminded himself fiercely.

You are a highly skilled linguist. What's the matter? Don't you blikkel English?

e groaned and started searching through his briefcase for the reports from Psych. Easton must be insane. He must! Ramirez says it's no language. Stoughton says it's no language. And I, Jonathan thought savagely, say it's no language.

But—

Margery tiptoed into the study with a tray.

"But Psych," he continued aloud to her, "Psych says it must be a language because, they say, Easton is not insane!"

"Oh, dear," sighed Margery, blinking her pale blue eyes. "That again?" She set his coffee on the desk in front of him. "Poor Jonathan. Why doesn't the Institute give up?"

"Because they can't." He reached for the cup and sat glaring at the steaming coffee.

"Well," said his wife, settling into the leather chair beside him, "I certainly would. My goodness, it's been over a month now since he came back, and you haven't learned a thing from him!"

"Oh, we've learned some. And this morning, for the first time, Easton himself began to seem puzzled by a few of the things he was saying. He's beginning to use terms we can understand. He's coming around. And if I could only find some clue—some sort of—"

Margery snorted. "It's just plain foolish! I knew the Institute was asking for trouble when they sent the Rhinestead off. How do they know Easton ever got to Mars, anyway? Maybe he did away with those other men, cruised around, and then came back to Earth with this made-up story just so he could seem to be a hero and—"

"That's nonsense!"

"Why?" she demanded stubbornly. "Why is it?"

"Because the Rhinestead was tracked, for one thing, on both flights, to and from Mars. Moonbase has an indisputable record of it. And besides, the instruments on the ship itself show—" He found the report he had been searching for. "Oh, never mind."

"All right," she said defiantly. "Maybe he did get to Mars. Maybe he did away with the crew after he got there. He knew the ship was built so that one man could handle it in an emergency. Maybe he—"

"Look," said Jonathan patiently. "He didn't do anything of the sort. Easton has been checked so thoroughly that it's impossible to assume anything except, (a) he is sane, (b) he reached Mars and made contact with the Martians, (c) this linguistic barrier is a result of that contact."

argery shook her head, sucking in her breath. "When I think of all those fine young men," she murmured. "Heaven only knows what happened to them!"

"You," Jonathan accused, "have been reading that columnist—what's-his-name? The one that's been writing such claptrap ever since Easton brought the Rhinestead back alone."

"Cuddlehorn," said his wife. "Roger Cuddlehorn, and it's not claptrap."

"The other members of the crew are all alive, all—"

"I suppose Easton told you that?" she interrupted.

"Yes, he did."

"Using double-talk, of course," said his wife triumphantly. At the look on Jonathan's face, she stood up in guilty haste. "All right, I'll go!" She blew him a kiss from the door. "Richie and I are having lunch at one. Okay? Or would you rather have a tray in here?"

"Tray," he said, turning back to his desk and his coffee. "No, on second thought, call me when lunch is ready. I'll need a break."

He was barely conscious of the closing of the door as Margery left the room. Naturally he didn't take her remarks seriously, but—

He opened the folder of pictures and studied them again, along with the interpretations by Psych, Stoughton, Ramirez and himself.

Easton had drawn the little stick figures on the first day of his return. The interpretations all checked—and they had been done independently, too. There it is, thought Jonathan. Easton lands the Rhinestead. He and the others meet the Martians. They are impressed by the Martians. The others stay on Mars. Easton returns to Earth, bearing a message.

Question: What is the message?

Teeth set, Jonathan put away the pictures and went back to the tape on the recorder. "Yes," said his own voice, in answer to Easton's outburst. "I do—er—blikkel English. But tell me, Mr. Easton, do you understand me?"

"Under-stand?" The man seemed to have difficulty forming the word. "You mean—" Pause. "Dr. Blair, I murv you. Is that it?"

"Murv," repeated Jonathan. "All right, you murv me. Do you murv this? I do not always murv what you say."

A laugh. "Of course not. How could you?" Suppressed groan. "Carooms," Easton had murmured, almost inaudibly. "Just when I almost murv, the kwakut goes freeble."

Jonathan flipped the switch on the machine. "Murv" he wrote on his pad of paper. He added "Blikkel," "Carooms" and "Freeble." He stared at the list. He should understand, he thought. At times it seemed as if he did and then, in the next instant, he was lost again, and Easton was angry, and they had to start all over again.

ighing, he took out more papers, notes from previous sessions, both with himself and with other linguists. The difficulty of reaching Easton was unlike anything he had ever before tackled. The six months of Navajo had been rough going, but he had done it, and done it well enough to earn the praise of Old Comas, his informant. Surely, he thought, after mastering a language like that, one in which the student must not only learn to imitate difficult sounds, but also learn a whole new pattern of thought—

Pattern of thought. Jonathan sat very still, as though movement would send the fleeting clue back into the corner from which his mind had glimpsed it.

A whole new frame of reference. Suppose, he toyed with the thought, suppose the Martian language, whatever it was, was structured along the lines of Navajo, involving clearly defined categories which did not exist in English.

"Murv," he said aloud. "I murv a lesson, but I blikkel a language."

Eagerly, Jonathan reached again for the switch. Categories clearly defined, yes! But the categories of the Martian language were not those of the concrete or the particular, like the Navajo. They were of the abstract. Where one word "understand" would do in English, the Martian used two—

Good Lord, he realized, they might use hundreds! They might—

Jonathan turned on the machine, sat back and made notes, letting the recorder run uninterrupted. He made his notes, this time, on the feelings he received from the words Easton used. When the first tape was done, he put on the second.

Margery tapped at the door just as the third tape was ending. "In a minute," he called, scribbling furiously. He turned off the machine, put out his cigarette and went to lunch, feeling better than he had in weeks.

Richie was at the kitchen sink, washing his hands.

"And next time," Margery was saying, "you wash up before you sit down."

Richie blinked and watched Jonathan seat himself. "Daddy didn't wash his hands," he said.

Margery fixed the six-year-old with a stern eye. "Richard, don't be rude."

"Well, he didn't." Richie sat down and reached for his glass of milk.

"Daddy probably washed before he came in," said Margery. She took the cover off a tureen, ladled soup into bowls and passed sandwiches, pretending not to see the ink-stained hand Jonathan was hiding in his lap.

Jonathan, elated by the promise of success, ate three or four sandwiches, had two bowls of soup and finally sat back while Margery went to get coffee.

Richie slid part way off his chair, remembered, and slid back on again. "Kin I go?" he asked.

"Please may I be excused," corrected his father.

ichie repeated, received a nod and ran out of the dinette and through the kitchen, grabbing a handful of cookies on the way. The screen door banged behind him as he raced into the backyard.

"Richie!" Margery started after him, eyes ablaze. Then she stopped and came back to the table with the coffee. "That boy! How long does it take before they get to be civilized?" Jonathan laughed. "Oh, sure," she went on, sitting down opposite him. "It's funny to you. But if you were here all day long—" She stirred sugar into her cup. "We should have sent him to camp, even if it would have wrecked the budget!"

"Oh? Is it that bad?"

Margery shuddered. "Sometimes he's a perfect angel, and then—It's unbelievable, the things that child can think of! Sometimes I'm convinced children are another species altogether! Why, only this morning—"

"Well," Jonathan broke in, "next summer he goes to camp." He stood up and stretched.

Margery said wistfully, "I suppose you want to get back to work."

"Ummmm." Jonathan leaned over and kissed her briefly. "I've got a new line of attack," he said, picking up his coffee. He patted his wife's shoulder. "If things work out well, we might get away on that vacation sooner than we thought."

"Really?" she asked, brightening.

"Really." He left the table and went back to his den.

Putting the next tape on the machine, he settled down to his job. Time passed and finally there were no more tapes to listen to.

He stacked his notes and began making lists, checking through the sheets of paper for repetitions of words Easton had used, listing the various connotations which had occurred to Jonathan while he had listened to the tapes.

As he worked, he was struck by the similarity of the words he was recording to the occasional bits of double-talk he had heard used by comedians in theaters and on the air, and he allowed his mind to wander a bit, exploring the possibilities.

Was Martian actually such a close relative to English? Or had the Martians learned English from Easton, and had Easton then formed a sort of pidgin-English-Martian of his own?

Jonathan found it difficult to believe in the coincidence of the two languages being alike, unless—

He laughed. Unless, of course, Earthmen were descended from Martians, or vice versa. Oh, well, not my problem, he thought jauntily.

e stared at the list before him and then he started to swear, softly at first, then louder. But no matter how loudly he swore, the list remained undeniably and obstinately the same:

Freeble—Displeasure (Tape 3)

Freeble—Elation (Tape 4)

Freeble—Grief (Tape 5)

"How," he asked the empty room, "can a word mean grief and elation at the same time?"

Jonathan sat for a few moments in silence, thinking back to the start of the sessions with Easton. Ramirez and Stoughton had both agreed with him that Easton's speech was phonemically identical to English. Jonathan's trained ear remembered the pronunciation of "Freeble" in the three different connotations and he forced himself to admit it was the same on all three tapes in question.

Stuck again, he thought gloomily.

Good-by, vacation!

He lit a cigarette and stared at the ceiling. It was like saying the word "die" meant something happy and something sad at one and the same, like saying—

Jonathan pursed his lips. Yes, it could be. If someone were in terrible pain, death, while a thing of sorrow, could also mean release from suffering and so become a thing of joy. Or it could mean sorrow to one person and relief to another. In that case, what he was dealing with here was not only—

The crash of the ball, as it sailed through the window behind his desk, lifted Jonathan right from his chair. Furious, his elusive clue shattered as surely as the pane of glass, he strode to the window.

"Richie!"

His son, almost hidden behind the lilac bush, did not answer.

"I see you!" Jonathan bellowed. "Come here!"

The bush stirred slightly and Richie peeped through the leaves. "Did you call me, Daddy?" he asked politely.

Jonathan clamped his lips shut and pointed to the den. Richie tried a smile as he sidled around the bush, around his father, and into the house.

"My," he marveled, looking at the broken glass on the floor inside. "My goodness!" He sat down in the leather chair to which Jonathan motioned.

"Richie," said his father, when he could trust his voice again, "how did it happen?"

His son's thin legs, brown and wiry, stuck out straight from the depths of the chair. There was a long scratch on one calf and numerous black-and-blue spots around both knees.

"I dunno," said Richie. He blinked his eyes, deeper blue than Margery's, and reached up one hand to push away the mass of blond hair tumbling over his forehead. He was obviously trying hard to pretend he wasn't in the room at all.

onathan said, "Now, son, that is not a good answer. What were you doing when the ball went through the window?"

"Watching," said Richie truthfully.

"How did it go through the window?"

"Real fast."

Jonathan found his teeth were clamped. No wonder he couldn't decode Easton's speech—he couldn't even talk with his own son!

"I mean," he explained, his patience wavering, "you threw the ball so that it broke the window, didn't you?"

"I didn't mean it to," said Richie.

"All right. That's what I wanted to know." He started on a lecture about respect for other people's property, while Richie sat and looked blankly respectful. "And so," he heard himself conclude, "I hope we'll be more careful in the future."

"Yes," said Richie.

A vague memory came to Jonathan and he sat and studied his son, remembering him when he was younger and first starting to talk. He recalled the time Richie, age three, had come bustling up to him. "Vransh!" the child had pleaded, tugging at his father's hand. Jonathan had gone outside with him to see a baby bird which had fallen from its nest. "Vransh!" Richie had crowed, exhibiting his find. "Vransh!"

"Do I get my spanking now?" asked Richie from the chair. His eyes were wide and watchful.

Jonathan tore his mind from still another recollection: the old joke about the man and woman who adopted a day-old French infant and then studied French so they would be able to understand their child when he began to talk. Maybe, thought Jonathan, it's no joke. Maybe there is a language—

"Spanking?" he repeated absentmindedly. He took a fresh pencil and pad of paper. "How would you like to help with something, Richie?"

The blue eyes watched carefully. "Before you spank me or after?"

"No spanking." Jonathan glanced at the Easton notes, vaguely aware that Richie had suddenly relaxed. "What I'm going to do," he went on, "is say some words. It'll be a kind of game. I'll say a word and then you say a word. You say the first word you think after you hear my word. Okay?" He cleared his throat. "Okay! The first word is—house."

"My house."

"Bird," said Jonathan.

"Uh—tree." Richie scratched his nose and stifled a yawn.

isappointed, Jonathan reminded himself that Richie at six could not be expected to remember something he had said when he was three. "Dog."

"Biffy." Richie sat up straight. "Daddy, did you know Biffy had puppies? Steve's mother showed me. Biffy had four puppies, Daddy. Four!"

Jonathan nodded. He supposed Richie's next statement would be an appeal to go next door and negotiate for one of the pups, and he hurried on with, "Carooms."

"Friends," said Richie, eyes still shining. "Daddy, do you suppose we could have a pup—" He broke off at the look on Jonathan's face. "Huh?"

"Friends," repeated Jonathan, writing the word slowly and unsteadily. "Uh—vacation."

"Beach," said Richie cautiously, still looking scared.

Jonathan went on with more familiar terms and Richie slowly relaxed again in the big chair. From somewhere in the back of his mind, Jonathan heard Margery say, "Sometimes I think they're a different species altogether." He kept his voice low and casual, uncertain of what he was thinking, but aware of the fact that Richie was hiding something. The little mantel clock ticked drowsily, and Richie began to look sleepy and bored as they went through things like "car" and "school" and "book." Then—

"Friend," said Jonathan.

"Allavarg," yawned Richie. "No!" He snapped to, alert and wary. "I mean Steve."

His father looked up sharply. "What's that?"

"What?" asked Richie.

"Richie," said Jonathan, "what's a Caroom?"

The boy shrugged and muttered, "I dunno."

"Oh, yes, you do!" Jonathan lit a cigarette. "What's an Allavarg?" He watched the boy bite his lips and stare out the window. "He's a friend, isn't he?" coaxed Jonathan. "Your friend? Does he play with you?"

The blond head nodded slowly and uncertainly.

"Where does he live?" persisted Jonathan. "Does he come over here and play in your yard? Does he, Richie?"

The boy stared at his father, worried and unhappy. "Sometimes," he whispered. "Sometimes he does, if I call him."

"How do you call him?" asked Jonathan. He was beginning to feel foolish.

"Why," said Richie, "I just say 'Here, Allavarg!' and he comes, if he's not too busy."

"What keeps him busy?" Such nonsense! Allavarg was undoubtedly an imaginary playmate. This whole hunch of his was utter nonsense. He should be at work on Easton instead of—

"The nursery keeps him busy," said Richie. "Real busy."

onathan frowned. Did Richie mean the greenhouse down the road? Was there a Mr. Allavarg who worked there? "Whose nursery?"

"Ours." Richie wrinkled his face thoughtfully. "I think I better go outside and play."

"Our nursery?" Jonathan stared at his son. "Where is it?"

"I think I better go play," said Richie more firmly, sliding off the chair.

"Richard! Where is the nursery?"

The full lower lip began to tremble. "I can't tell you!" Richie wailed. "I promised!"

Jonathan slammed his fist on the desk. "Answer me!" He knew he shouldn't speak this way to Richie; he knew he was frightening the boy. But the ideas racing through his mind drove him to find out what this was all about. It might be nothing, but it also might be—"Answer me, Richard!"

The child stifled a sob. "Here," he said weakly.

"Here? Where?"

"In my house," said Richie. "And Steve's house and Billy's and all over." He rubbed his eyes, leaving a grimy smear.

"All right," soothed Jonathan. "It's all right now, son. Daddy didn't mean to scare you. Daddy has to learn these things, that's all. Just like learning in school."

The boy shook his head resentfully. "You know," he accused. "You just forgot."

"What did I forget, Richie?"

"You forgot all about Allavarg. He told me! It was a different Allavarg when you were little, but it was almost the same. You used to play with your Allavarg when you were little like me!"

Jonathan took a deep breath. "Where did Allavarg come from, Richie?"

But Richie shook his head stubbornly, lips pressed tight. "I promised!"

"Richie, a promise like that isn't a good one," pleaded Jonathan. "Allavarg wouldn't want you to disobey your father and mother, would he?"

The child sat and stared at him.

This was a very disturbing thought and Jonathan could see Richie did not know how to deal with it.

He pressed his momentary advantage. "Allavarg takes care of little boys and girls, doesn't he? He plays with them and he looks after them, I'll bet."

Richie nodded uncertainly.

"And," continued Jonathan, smiling what he hoped was a winning, comradely smile at his son, "I'll bet that Allavarg came from some place far, far away, didn't he?"

"Yes," said Richie softly.

"And it's his job to be here and look after the—the nursery?" Jonathan bit his lip. Nursery? Earth? Carooms—Martians? His head began to ache. "Son, you've got to help me understand. Do you—do you murv me?"

ichie shook his head. "No. But I will after—"

"After what?"

"After I grow up."

"Why not now?" asked Jonathan.

The blond head sank lower. "Because you framish, Daddy."

His father nodded, trying to look wise, wincing inwardly as he pictured his colleagues listening in on this conversation. "Well—why don't you help me so I don't framish?"

"I can't." Richie glanced up, his eyes stricken. "Some day, Allavarg says, I'm going to framish, too!"

"Grow up, you mean?" hazarded Jonathan, and this time his smile was real as he looked at the smudged eyes and soft round cheeks. "Why, Richie," he went on, his voice suddenly husky, "it's fun to be a little boy, but there'll be lots to do when you grow up. You—"

"I wish I was Mr. Easton!" Richie said fiercely.

Jonathan held his breath. "What about Mr. Easton?"

Richie squirmed out of the chair and clutched Jonathan's arm. "Please, Daddy! If you let Mr. Easton go back, can I go, too? Please? Can I?"

Jonathan put his hands on his son's shoulders. "Richie! What do you know about Mr. Easton?"

"Please? Can I go with him?" The shining blue eyes pleaded up at him. "If you don't let him go back pretty soon, he's going to framish again! Please! Can I?"

"He's going to framish," nodded Jonathan. "And what then?" he coaxed. "What'll happen after he framishes? Will he be able to tell me about his trip?"

"I dunno," said Richie. "I dunno how he could. After you framish, you don't remember lots of things. I don't think he's even gonna remember he went on a trip." The boy's hands shook Jonathan's arm eagerly. "Please, Daddy! Can I go with him?"

"No!" Jonathan glared and released his hold on Richie. Didn't he have troubles enough without Richie suggesting—"About the nursery," he said briskly. "Why is there a nursery?"

"To take care of us." Richie looked worried. "Why can't I go?"

"Because you can't! Why don't they have the nursery back where Allavarg came from?"

"There isn't any room." The blue eyes studied the man, looking for a way to get permission to go with Mr. Easton.

"No room? What do you mean?"

Richie sighed. Obviously he'd have to explain first and coax later. "Well, you know my school? You know my teacher in school? You know when my teacher was different?" He peered anxiously at Jonathan, and suddenly the man caught on.

"Of course! You mean when they split the kindergarten into two smaller groups because there were too many—"

is voice trailed off. Too many. Too many what? Too many Martians on Mars? Growing population? No way to cut down the birth rate? He pictured the planet with too many people. What to do? Move out. Take another planet. Why didn't they just do that? He put the question to Richie.

"Oh," said his son wisely, "they couldn't because of the framish. They did go other places, but everywhere they went, they framished. And after you framish, you ain't—aren't a Caroom any more. You're a Gunderguck and of course—"

"Huh?"

"—and a Caroom doesn't like to framish and be a Gunderguck," continued Richie happily, as though reciting a lesson learned in school. "He wants to be a Caroom all the time because it's better and more fun and you know lots of things you don't remember after you get to be a Gunderguck. Only—" he paused for a gulp of air—"only there wasn't room for all the Carooms back home and they couldn't find any place where they could be Carooms all the time, because of the framish. So after a long time, and after they looked all over all around, they decided maybe it wouldn't be so bad if they sent some of their little boys and girls—the ones they didn't have room for—to some place where they could be Carooms longer than most other places. And that place," Richie said proudly, "was right here! 'Cause here there's almost as much gladdisl as back home and—"

"Gladdisl?" Jonathan echoed hoarsely. "What's—"

"—and after they start growing up—"

"Gladdisl," Jonathan repeated, more firmly. "Richie, what is it?"

The forehead puckered momentarily. "It's something you breathe, sort of." The boy shied away from the difficult question, trying to remember what Allavarg had said about gladdisl. "Anyway, after the little boys and girls start to grow up and after they framish and be Gundergucks, like you and Mommy, the Carooms back home send some more to take their places. And the Gundergucks who used to be Carooms here in the nursery look after the new little—"

"Wait a minute! Wait a minute!" Jonathan interrupted suspiciously. "I thought you said Allavarg looks after them."

"He does. But there's so many little Carooms and there aren't many Allavargs and so the Gundergucks have to help. You help," Richie assured his father. "You and Mommy help a little bit."

Big of you to admit it, old man, thought Jonathan, suppressing a smile. "But aren't you our little boy?" he asked. He had a sudden vision of himself addressing the scientists at the Institute: "And so, gentlemen, our babies—who, incidentally, are really Martians—are brought by storks, after all. Except in those cases where—"

"The doctor brought me in a little black bag," said Richie.

he boy stood silent and studied his father. He sort of remembered what Allavarg had said, too. Things like You mustn't ever tell and It's got to be a secret and They'd only laugh at you, Richie, and if they didn't laugh, they might believe you and try to go back home and there just isn't any room.

"I think," said Richie, "I think I better—" He took a deep breath. "Here, Allavarg," he called in a soft, piping voice.

Jonathan raised his head. "Just what do you think you're doing—"

There was a sound behind him, and Jonathan turned startledly.

"Shame on you," said Allavarg, coming through the broken window.

Jonathan's words dropped away in a faint gurgle.

"I'm sorry," said Richie. "Don't be dipplefit."

"It's a mess," Allavarg replied. "It's a krandoor mess!" He waved his arm in the air over Jonathan's head. "And don't think I'm going to forget it!" The insistent hiss of escaping gas hovered over the moving pellet in his hand. "Jivis boy!"

Jonathan coughed suddenly. He got as far as "Now look here" and then found that he could neither speak nor move. The gas or whatever it was stung his eyes and burned in his throat.

"Why don't you just freeble him?" Richie asked unhappily. "You're using up all your gladdisl! Why don't you freeble him and get me another one?"

"Freeble, breeble," grumbled Allavarg, shoving the capsule directly under Jonathan's nose. "Just like you youngsters, always wanting to take the easy way out! Gundergucks don't grow on blansercots, you know."

Jonathan felt tears start in his eyes, partly from the fumes and partly from a growing realization that Allavarg was sacrificing precious air for him. He tried to think. If this was gladdisl and if this would keep a man in the state of being a Caroom, then—

"There," said Allavarg, looking unhappily at the emptied pellet. He shook it, sniffed it and finally returned it to the container at his side.

"I'm sorry," Richie whispered. "But he kept askin' me and askin' me."

"There, there," said Allavarg, going to the window. "Don't fret. I know you won't do it again." He turned and looked thoughtfully at Jonathan. He winked at Richie and then he was gone.

onathan rubbed his eyes. He could move now. He opened his mouth and waggled his jaws. Now that the room was beginning to be cleared of the gas, he realized that it had had a pleasant odor. He realized—

Why, it was all so simple! Remembering his sessions with Easton, Jonathan laughed aloud. So simple! The message? Stay away from Mars! No room there! They said I could come back if I gave you the message, but I have to come back alone because there's no room for more people!

No room? Nonsense! Jonathan reached for the phone, dialled the Institute and asked for Dr. Stoughton. No room? On the paradise that was Mars? Well, they'd just have to make room! They couldn't keep that to themselves!

"Hello, Fred?" He leaned back in his chair, feeling a surge of pride and power. Wait till they heard about this! "Just wanted to tell you I solved the Easton thing. Just a simple case of hapsodon. You see, Allavarg came and gave me a tressimox of gladdisl and now that I'm a Caroom again—What? What do you mean, what's the matter? I said I'm not a Gunderguck any more." He stared at the phone. "Why, you spebberset moron! What's the matter with you? Don't you blikkel English?"

From the depths of the big chair across the room, Richie giggled.

—JEAN M. JANIS

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Rough Translation, by Jean M. Janis

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROUGH TRANSLATION ***

***** This file should be named 31980-h.htm or 31980-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/9/8/31980/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.