This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Niagara

An Aboriginal Center of Trade

Author: Peter A. (Peter Augustus) Porter

Release Date: April 12, 2010 [eBook #31955]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NIAGARA***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/niagaraaborigina00portuoft |

NIAGARA,

AN ABORIGINAL

CENTER OF TRADE

The printed story of Niagara dates back only three centuries; and during the first three decades of even that period the references to this wonderful handiwork of Nature—which was located in a then unexplored region of a New World, a Continent then inhabited only by warring tribes of superstitious Savages—are few and far between.

Three facts relating to this locality—and three only—seem to be proven as ante-dating the commencement of that printed story.

That its "Portage" had long been in use.

That it was then, and long had been, a spot for the annual assemblage of the Indians "for trade."

That here, and here only, was found a certain substance which the Aborigines had long regarded as a cure for many human ills.

Before 1600, everything else that we think we know, and like to quote about Niagara, is only Indian Myth or Tradition; possibly handed down for Ages, orally, from generation to generation, amongst the Aborigines; or, quite as probable, it is the invention of some Indian or White man Mythologist of recent times; the presumption in favor of the latter being strengthened, when no mention of the legend, not even the slightest reference thereto, is to be found in any of the writings of any of the authors, who (either through personal visits to the Tribes living comparatively near to the Cataract, or from narrations told to them by Indians living elsewhere on this Continent) had learnt their facts at first hand, and had then duly recorded them,—until long after the beginning of the eighteenth Century.

It is probably to the latter class—modern traditions—even with all their plausibilities, based upon the superstitious and stoical nature of the Aborigines—that several of the best-known Legends concerning Niagara belong.

Three of those legends, especially, appeal to the imagination. One relates to Worship, one to Healing, one to Burial,—embracing the Deity, Disease, and Death.

The Legend of Worship is the inhuman yet fascinating one that the Onguiaahras (one of the earliest-known orthographies of the word Niagara), who were a branch of the Neutrals, and dwelt in the immediate vicinity of the Great Fall—and, according to Indian custom, took their name from the chief physical feature of their territory—long followed the custom of annually sacrificing to the Great Spirit "the fairest maiden of the Tribe"; sending her, alive, over the Falls in a white canoe (which was decked with fruits and flowers, and steered by her own hand) as a special offering to the Deity for tribal favor, and for protection against its more numerous and more powerful foes.

And that, at the time of this annual Sacrifice, the tribes from far and near assembled at Niagara, there to worship the Great Spirit. If this Legend is based on fact, it would certainly have made the locality a famous place of annual rendezvous; and at such a rendezvous the opportunities for the exchange of many and varied commodities—"trade"—would surely not have been neglected.

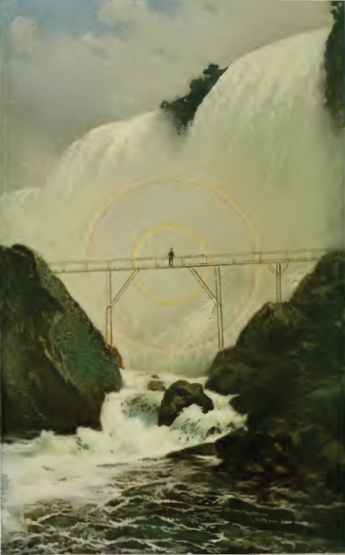

The Legend of Healing is, that anyone, Brave or Squaw, if ill, would quickly be restored to perfect health could they but reach the base of the Falls, go in behind the sheet of falling waters,—entering, as it were, the abode of the Great Spirit,—and, on emerging therefrom, be able to behold a complete circular Rainbow—which should symbolize the Deity's absolute promise of restoration to perfect health.

Of course, it was the difficulty and danger of descending into the Gorge, and of scaling the face of the cliff in returning—accomplishable in those days only by means of vines which clung to the rocks, or by crude ladders (formed of long trunks of trees, from which all branches had been lopped off about a foot from the trunk, and set upright, close to the face of the cliff)—that lends any plausibility to the legend.

The Legend of Burial was, that Goat Island was specially reserved as a burying-ground for famous chiefs and noted warriors.

If this Legend was founded on fact, it certainly would have made Niagara at that time one of the best known and most frequented spots on the Continent; and at each visit for such burial, trade would doubtless have been carried on.

CIRCULAR RAINBOWS

It is possible to-day, as it most certainly was in those traditional days, to behold a complete circular Rainbow at Niagara; generally, only when one is out in front of the falling waters, close to the spray, near the level of the river in the Gorge; always with the Sun at one's back—and the Sun must shine brightly, and the Mist must be plentiful.

It is possible to see a complete circular Rainbow anywhere, on land or water, whenever one stands between the Sun and a sufficiently abundant mist (standing close to the latter), and the Sun is near the horizon.

It is possible to see it, at some point at Niagara, often,—that is on every bright day,—because that abundant curtain of mist is ever present; and the Gorge, by reason of its great width and depth, affords specially favorable opportunities.

This curious phenomenon is obtainable easily and regularly only in the Gorge at the Goat Island end of the American Fall, from the rocks in front of the Cave of the Winds (for the prevailing winds of the locality are from the southwest, which bring the spray cloud into the best relative position at this point), or from the deck of the steamboat, at certain parts of the trip,—and from both only in the afternoon.

It can sometimes be seen from Prospect Point, and from the Terrapin Rocks—in the early morning, when the spray-cloud rises towards the north.

It can also, sometimes (at the season when the Sun sets farthest to the northward), be seen from the rocks out in front of the American Fall, below Prospect Point.

This was the spot where the Aborigines would most easily have tested the efficacy of the Legend; for their descent into the Gorge was made at a point on the American shore, not so very far north from the end of that Fall.

When white men first settled near the Cataract, in the first decade of the 19th Century, the location of the "Indian Ladder" was amongst the present overflows from the mills of the Lower Milling district. That, by reason of the "debris slope" of the Gorge being highest at that point, had doubtless been its location for ages.

The fact that, even at the most accessible (and that by no means easily reached) end of the Fall in the Gorge, the entire conditions of the Legend could so rarely be fully complied with, would have been to the unscientific minds of the Savages only an additional incentive to a firmer belief in it.

It is also observable from the rocks beyond and below Terrapin Point, on the Goat Island side of the Horse-Shoe Fall; but the climb out to that point is both arduous and dangerous, and is very rarely attempted.

No such phenomenon can be seen from the Canadian shore, because there are no rocks out in front of that end of the Horse-Shoe Fall on which one can stand.

Were one to stand upon the apex of the Rock of Ages, or on the apex of any other high rock at the base of the Fall, at noon, when the sky was clear above, and the currents of air happened to surround the base of that rock on all sides with spray, as one turned completely around one would be in the center of a complete circular Rainbow—which would be below the level of the feet—and of which one would see but the half at any portion of the turn.

At Niagara, when one gazes on a complete circular bow, as seen against the perpendicular curtain of spray, the center of the circle will always be lower than the point where one is standing. This is necessarily so, from the very nature of things,—because the Sun, one's head, and the center of that circle must be in a line.

When the point of observation is high enough, and the spray-cloud spreads out extensively enough, it is possible to see two concentric, complete Rainbows at one time. In fact, one does often see a portion of the arc of such a second bow; but three complete concentric bows, or three arcs of bows, are never seen at Niagara, nor anywhere else.

George William Curtis, in "Lotus Eating," records,—

"There [at the Cave of the Winds], at sunset, and there only, you may see three circular rainbows, one within another,"—

He does not say, "complete circles"; he doubtless meant "arcs." He does not say he saw them; so in the absence of a more definite statement, it was certainly merely hearsay to which he referred.

John R. Barlow, who has been a guide at the Cave of the Winds for over thirty years, says that on numerous occasions during that period he has seen two complete circular Rainbows at one time, at that point. He observed it twice, and only twice, in 1905.

In 1872, Professor Tyndall, with Barlow as his guide, made an exhaustive study of the Goat Island ends of the American and Horse-Shoe Falls. As he was gazing at a complete Rainbow circle, Barlow told him that he had sometimes seen two complete concentric bows at one time. "That is possible," replied Tyndall.

"And I have heard people say they have seen three such bows; though I myself have never seen the third," said Barlow.

"Because it is an impossibility," answered Tyndall. "The second bow is merely the reflexion of the first. A third bow would be a shadow of a shadow; and no one can see that."

Had this Legend of Healing been found recorded in any of the early chronicles, it would have been the earliest known reference to Niagara in its relation to Medicine; and would have associated the Cataract therewith long, long before the advent of the white man.

But, alas! it is not so found; and no trace of it can be met with, until a very recent date. It has so much the appearance of a made-to-order story, such a specially-prepared-to-fit-the-locality aspect, it savors so strongly of an attempt to make the early Indian Mythology conform to the Christian story of the "Bow of Promise," that its Aboriginal authenticity may well be doubted.

FIRST WHITE VISITOR

We do not know, and we never shall know, the name of the first white man who gazed upon the Cataract of Niagara; that marvelous spot, the scenic wonder of the World, that glory of Nature, which has been referred to as "The Emblem of God's Majesty on Earth,"—where, in the words of Father Hennepin, in 1697,—

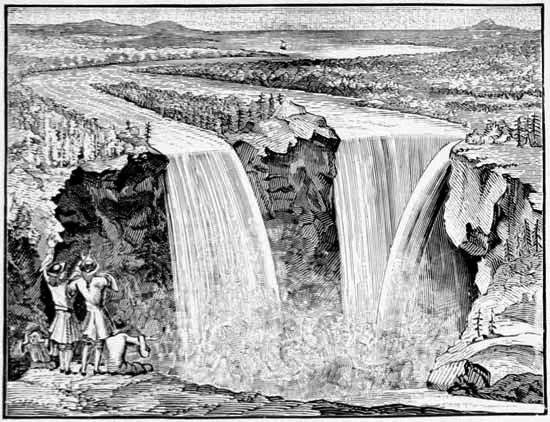

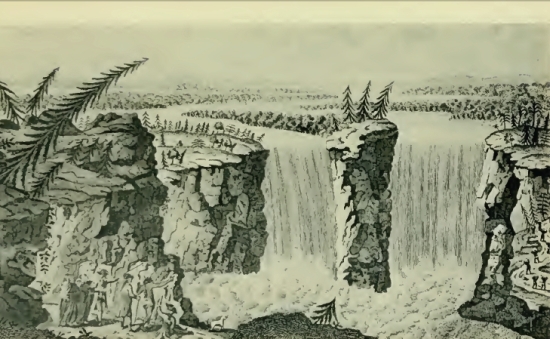

"Betwixt the lakes Erie and Ontario, is a great and prodigious cadence of water, which falls down after a surprising and astonishing manner; insomuch that the Universe itself does not afford its parallel."

Which description, even to-day, two Centuries later, stands out as the most impressive, as well as the quaintest, brief mention of Niagara that was ever penned. And Father Hennepin also gave to the World, in the same volume, the first known picture of Niagara.

It was unquestionably a Frenchman who first, through pale-face eyes, saw the great Cataract; and it was later than 1608, the year when the ancient City of Quebec was founded, and white men first settled in the northern part of this Continent.

Possibly, though improbably, he may have been one of those holy men, Priests of the Catholic Church, who devoted their learning, their strength, and their years to the cause of their Maker; who daily risked their lives, as alone they braved the hardships and the sufferings of long journeys through pathless forests, and who encountered the fury of unknown savages, as they carried the Gospel to Tribes who dwelt along the shores of mighty waters, in a vast and an unexplored wilderness; and tried, though in vain, to lead those strange peoples to the Ways of God.

It is more likely to have been one of those fearless and hardy men, one of the earliest members of what later became a distinct class—the Coureurs de Bois, or Woodsmen—a class founded by Champlain; on a correct principle for commercial intercourse and the extension of sovereignty, under conditions as they then and there existed (but probably without any full appreciation of the important and prominent part it was destined, later, to play in the development of New France); when, in 1610, he gave a young Frenchman, Etienne Brule, to the Algonquin chief Iroquet; who, in appreciation of Champlain's confidence, gave him a young savage named Savignon, as a pledge of future friendship.

Brule was the first Frenchman known to have joined the savages, to become one of them, and adopt their manner of life. He spent years amongst them, was a woodsman or trader, learnt their languages, was Champlain's personal interpreter among the various tribes, and was often sent as Ambassador from the French at Quebec to savage Nations.

Beloved and trusted by the Indians for years, traveling all over the Northwest, claiming to have discovered Lake Superior, and a copper mine on its shores (in proof of which he brought back samples of that metal to Quebec), he was finally tortured, put to death, and eaten by the Savages.

By reason of his acquaintance with many tribes, of his occupation, and of his travels, there is no one who is more likely to be entitled to the distinction of having been the first of the white man's race to behold Niagara than this same Etienne Brule.

From his intimacy with Champlain, he must have known—what Champlain knew and had recorded—of the existence of such a waterfall; indeed, it is by no means improbable that many of the details of Champlain's maps (especially those relating to regions which Champlain never saw, but which Brule did visit) were drawn from the latter's descriptions.

From his intimacy with Iroquet—Brule spent the better part of eight years in his Country and in that of his allies; being the territory lying to the north of Lake Ontario—he must have known what Iroquet knew of the location of such a waterfall (which was only about 150 miles from the center of his territory, and a journey of that distance was of small moment to the Indians of those days); and when Iroquet went to it as a "trading place," Brule doubtless accompanied him.

It must also be remembered that it was this same chief, Iroquet, who later confirmed to Father Daillon the renown of "the great River of the Neutrals"—that is the Niagara—as a Center of Trade; whose location he knew well, but refused to divulge to the Priest.

Knowing of such a wonderful waterfall's existence, and its general location; being a "trader," and Niagara being even then a well-known Center of Trade, the probabilities are that Brule visited it at a very early date.

A TRADING PLACE

But, while white men were no doubt at Niagara early in the 17th Century—possibly as early as 1611—and while we know that Traders and Priests were in its immediate vicinity at various times prior to 1669; and while we have good reason to believe, that in that latter year LaSalle himself explored the whole of the Niagara Frontier; yet it is not until 1678 that we have any positive record of any visit, nor any description of the Cataract by a man who claimed to have actually seen it.

Father Hennepin's first work, "Louisiana," published in 1681, tells of that first recorded visit, and gives the first description of Niagara by an eye-witness.

At the time when that first unnamed white man saw the Cataract the Indians had, and firmly believed in, at least one positive tradition regarding it; one which had long been believed in by the tribes far and near, and which had long been turned to good account in trade by former generations of Indians who dwelt at Niagara; and which was believed in and maintained for many a year afterwards. It was a tradition which had long caused the vicinity of the Cataract to be known far and wide as, and to be, a great Center of Trade; because it related to a highly-prized commodity which was found and primarily procurable only at this spot.

The first printed direct mention of Niagara referred to its famous Portage. The two next references to it were indirect and poetic, and, in so far as geographical location, certainly exemplified a poet's license.

The second printed allusion to it,—an indirect one, as noted later,—was in regard to trade.

Champlain was on the lower St. Lawrence River when, in 1603, he first heard of the Niagara Portage; Father Daillon was within a hundred miles of the Cataract when, in 1626, he first heard of Niagara as a "trading place."

When white men first became really acquainted with the Indians, 300 years ago, the various tribes had, and no doubt had long had, certain "trading places" where they annually met for barter.

At that time, the Hurons and Algonquins had such a meeting place on the upper Ottawa River.

It was at such a trade gathering at Lake Saint Peter, that Iroquet, in 1610, received Brule as a gift.

Father Sagard, who in 1625 was a Missionary among them at Lake Nipissing, has stated that the Hurons used each summer to travel for five or six weeks southerly, in order to meet the tribes which had goods they wanted; and that they brought back those articles both for their own use and for sale to other tribes. From the direction stated, and from other deductions, it is probable that that annual summer journey of the Hurons "for trade" had Niagara as its objective point.

That the Indians traded among themselves is unquestioned. When Cartier, in 1534, ascended the St. Lawrence River, the Indians of Hochelaga were smoking tobacco which had been grown in the sunny south lands. The Muskegons, around James Bay, traded their furs with their southern neighbors for birch bark, out of which to make their canoes. Axes and arrow heads of obsidian—a stone found on the lower Mississippi—were in use among the tribes to the north of Quebec. The Indian "trade" was not all done haphazard. The most of it was done at gatherings held at regularly agreed upon times and places. And in the selection of localities, Niagara must have been a favored meeting place.

That there, and there only, were found those "Erie Stones," a much-sought-for article, was an important reason for its selection as such; its central location and its accessibility from all points were other reasons.

No tribe which feared the fierce Iroquois—and that embraced almost every known tribe—would have dared to go to a "trading place," when in order to reach it they had to cross the country of the Iroquois. But they could get to Niagara from all sides without touching that Iroquois territory. There they could meet and barter with tribes otherwise almost impossible for them to reach.

The tribes of the southeast, and those of the northeast, could there meet in safety.

Again, it was in the Country of the Neutrals, whose territory lay between that of the Iroquois and the Hurons. And Indian law decreed—and it was observed—that in the cabins of the Neutrals even those bitter foes, Iroquois and Hurons, met in peace.

Champlain was certainly the first white man to mention the Falls of Niagara in Literature; Brule was probably Niagara's first white visitor; and equally probable, he was the first white man ever to "trade" there. One would like well to know the particulars of that "trade"—what he got and what he gave.

EARLY REFERENCES

Champlain and Brule are two names of surpassing interest in their relation to Niagara. The first unquestionably heads the long list of Authors who have ever written about our Waterfall; the other probably heads the infinitely longer list—comprising many millions—of those pale-faces who have ever visited our Cataract.

That first reference to Niagara in all Literature is found in that of France, in 1603, when Samuel de Champlain, the subsequent founder of Quebec, the first Governor-General of New France,—and still the most picturesque figure in all Canadian history,—narrated, in his now excessively rare pamphlet, "Des Sauvages" (of which only about half-a-dozen copies are known to exist), what the Indians on the St. Lawrence River told him about this waterfall (for he himself never saw Niagara), in these words:

"Then they come to a lake [Ontario] some eighty leagues long, with a great many Islands [the Thousand Islands], the water at its extremity being fresh and the winter mild. At the end of this lake they pass a fall [Niagara] somewhat high, where there is quite a little water which falls down. There they carry their canoes overland for about a quarter of a league, in order to pass the fall; afterwards entering another lake [Erie] some sixty leagues long and containing very good water."

In the same volume Champlain records that another savage told him,—

"That the water at the western end of the lake [Ontario] was perfectly salt; that there was a fall about a league wide, where a very large mass of water falls into said lake."

It was not the wonders nor the beauty of the Cataract that impressed itself upon the minds of those savages, and that led them to furnish to Champlain—and so to the white man's world—the very first knowledge of the existence of Niagara. No! What most impressed the Cataract upon the minds of those Aborigines was the fact that at this point, the Falls themselves, together with the Rapids for a short distance above them, and for a long distance below them, were an insuperable obstacle to water—that is, canoe—navigation; that here they were obliged to make a long "portage." It was the only break in an otherwise uninterrupted water travel of hundreds of miles; which, going westward, extended from a point on the St. Lawrence, many miles east of the outlet of Lake Ontario, clear to the farthest end of Lake Superior; and which, coming eastward, extended nearly 1,500 miles, from where the City of Duluth now stands even until it reached the bitter waters of the Atlantic Ocean in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence.

In the same volume, "Des Sauvages," appeared a poem by one "La Franchise," addressed to Champlain, in which mention is made of the "Saults Mocosans" or Mocosan Falls, "which shock the eyes of those who dare to look upon that unparalleled downpour."

Mocosa was the name of that territory vaguely called Virginia, and which seems to have embraced everything from New York to Florida, extending indefinitely to the west and northwest. The allusion is generally considered to refer to Niagara; thus making Niagara's appearance in Poetry cotemporaneous with its appearance in prose.

In 1609, Lescarbot published his "Histoire de la Nouvelle France," wherein he quotes extensively (including the references to Niagara) from Champlain; the work being reissued in several editions in subsequent years. And in 1610, Lescarbot, who was a great admirer of Champlain (he may himself have been "La Franchise"), produced a poem, wherein he speaks of the "great falls" which the Indians encounter in going up the St. Lawrence, from below the present site of Montreal, "jusqu'au voisinage de la Virginia"; which, under the above-noted boundaries of Virginia, has been stretched in imagination to include Niagara, but more likely meant the Rapids of the St. Lawrence.

Champlain, in the map which he made in 1612, notes a "waterfall," but places it at the Lake Ontario end of the river; still it is clearly meant for Niagara.

Early references to this Niagara Region—which up to about the middle of the 17th Century was owned and occupied by the Neuters, and after that time by their conquerors and annihilators, the Senecas—are to be found in that wonderful series of Reports made by the Catholic Missionaries in Canada to their Superiors in France, during a large part of the 17th Century, and known as the "Jesuit Relations."

From them we learn that Father Daillon was among the Neutrals, and "on the Iroquois Frontier" (which was east of the Niagara River, somewhere about midway between that and the Genesee River), in 1626.

In a letter, dated at Tonachin, a Huron village, 18th July, 1627, Father Daillon told of his visit to the Neuters the year before. In it he wrote:

"I have always seen them constant in their resolution to go with at least four canoes to the trade, if I would guide them, the whole difficulty being that we did not know the way. Yroquet, an Indian known in those countries, who had come there with twenty of his men hunting for beaver, and who took fully five hundred, would never give us any mark to know the mouth of the river. He and several Hurons assured us well that it was only ten days journey [from the Huron Country] to the trading place; but we were afraid of taking one river for another and losing our way, or dying of hunger on the land."

The above quotation, which was given in Sagard, 1636, was omitted from Daillon's letter by Le Clercq in his "Premier Établissement de la Foi," 1691. In his translation of the latter work, John Gilmary Shea, in a note concerning this very passage, says:

"This was evidently the Niagara River and the route through Lake Ontario," and he adds: "The omission of the passage by Le Clercq was evidently caused by the allusion to trade."

That omission was doubtless at the instance of the French Government, whose permission was then a necessity before any book could be published. That Government knew the importance and the advantages of Niagara, both as a strategic point and as a Center of Trade. Only four years before Le Clercq's book appeared a French army, under De Denonville, had built a fort there; but the hostility of the Iroquois (incited by British agents) had forced its abandonment a year later. Anxious to again possess it, planning now to do so by diplomacy rather than by arms, the French Government would naturally have objected to any published allusion to the locality as a point of Trade,—which could in no way have aided its designs, but by further calling Britain's attention to Niagara's importance, would naturally cause her agents to be still further vigilant toward frustrating any move of France for the control thereof.

In the same letter Daillon says:

"But the Hurons having discovered that I talked of leading them [the Neutrals] to the trade, he [Yroquet] spread in all the villages when he passed, very bad reports about me * * * in a word, the Hurons told them so much evil of us [the French] to prevent their going to trade * * * adding a thousand other absurdities to make us hated by them, and prevent their trading with us; so that they might have the trade with these nations themselves exclusively, which is very profitable to them."

Yroquet, who was Champlain's friend, as before mentioned, being a close ally of the Hurons, evidently had no desire for a Frenchman to open trade directly with the Iroquois—the sworn foes of the Hurons—and thus to divert any of the trade which he carried on with the French in the Huron Country.

So the first white man known to have been on the Niagara River (in 1626) wrote about it as a "trading place." It clearly was regarded in that light, at that time, both by the Neutrals and by the Hurons; those being the only two tribes which Father Daillon had visited. And if it was so known to the tribes on the west and northwest, there was no reason why it should not have been so known—and it no doubt was so known—to the tribes to the south, to the east, and to the west.

On his map, in 1632, Champlain continues his location of the Cataract at the point where the river enters Lake Ontario; and marks it, "Falls at the extremity of Lake St. Louis [Ontario] very high, where many fish come down and are stunned."

In 1640, Fathers Brebeuf and Chaumonot, on their famous Mission to the Neutrals, crossed the Niagara River at Onguiaahra, a village of that Nation, which stood on the site of the present Lewiston. They probably never saw the Falls; their visit being filled with danger, hunger, and threats of their destruction by the very savages whose souls they were trying to save. Father L'Allement, their Superior, in his account of their Mission, in the Jesuit Relation of 1642, speaks merely of "the village Onguiaahra, of the same name as the river."

Another passage in his letter says,—

"Many of our Frenchmen, who have been here in the Huron Country, in the past made journeys in this Country of the Neutral Nation, for the sake of reaping profit and advantage from furs, and other little wares that one might look for."

And in all probability some of those Frenchmen had reached the Niagara River, in their trade with the Neutrals, before Father Daillon crossed its stream.

Niagara was then, as it is now, the geographical center of the eastern one-third of North America; it was the center of population among the many and widely distributed Indian Tribes; it was the most accessible, the most easily reached place, from all directions, in America. Indian trails led toward it from all points of the compass; it was easily accessible by water from every quarter—and, by canoe, was the Indians preferred means of transportation.

It was thus easily reached by the tribes on the east and northeast by Lake Ontario; by the tribes on the north by Lake Simcoe and the portage to Toronto; by the tribes in the great west and northwest (covering a vast territory) by all the upper lakes; by the tribes in the southwest by the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Alleghany rivers; by the tribes in the southeast by the Susquehanna River. Even in aboriginal days—by reason of its central location, its portage, its position as a Center of Trade, and its "Erie Stones"—Niagara was the best and most widely known spot on the Continent; even as—for other reasons—it is to-day.

Father Ragueneau, in a letter written from the Huron Country, in Canada, in 1648, and published in the "Jesuit Relation" of 1649, makes the second known direct printed reference to the Falls themselves, when he writes,—

"Lake Erie, which is formed by the waters from the Mer Douce [Lake Huron], discharges itself into Lake Ontario, over a Cataract of fearful height,"

which description was, word for word, the same as is found in a letter, written not later than 1645, from that same Huron Country, by Docteur Gendron, but which was not published until 1660.

The third direct printed reference to our Cataract was in a letter, written by Father Bressani, from that same Huron Country, in 1652, and published the following year. He wrote,—

"Lake Erie discharges itself, by means of a very high Cataract, into a third lake, which is still larger and finer, called Lake Ontario."

Thus, up to 1660, the Jesuit Fathers, Ragueneau and Bressani, were the only persons, except Champlain, who had made any direct printed reference to Niagara's Waterfall; like him, neither of them ever saw it;—the three known men, who first mentioned in print what is to-day the best known Cataract on Earth, wrote from hearsay,—and none of them gave it a name.

Sanson, who, in 1650, had issued a map of North America, largely following those of Champlain, but improving on their accuracy (though not indicating Niagara), in 1656, issued one of New France or Canada, whereon he both correctly places our Waterfall, and, for the first time in Literature or Cartography gave it a direct name, marking it "Ongiara Sault." Much information about Canada had no doubt been made public in France—by Missionaries and Explorers, with the Government's approval—during those half-a-dozen years.

Hennepin, in 1683, was the first person to use the word "Niagara," which has been the accepted name ever since; though more than a hundred different ways of spelling it have been found. And from Hennepin's time,—by every known form of pictorial reproduction; during the last forty years by photography more than all other forms put together—Niagara has been the most pictured and therefore the best known spot on earth.

DOCTEUR GENDRON

In 1660, another, and a most interesting reference to our Cataract appeared in print; written by one Docteur Gendron. It does not appear that he ever saw it, but he seems to have learnt a good deal about it; of course he learnt it from the Indians; moreover, he learnt it from Hurons, who dwelt in more or less proximity to it; from men who, no doubt, themselves had seen it. He learnt it from the same source, not improbably from the same men, from whom Fathers Ragueneau and Bressani had gotten their less comprehensive knowledge of it—for he had a special reason, in the line of his profession, for learning about it. He had written home to France concerning it, at least three years before Ragueneau, at least seven years before Bressani, had done so. And, curiously enough, at the very time when Docteur Gendron wrote his letters, Fathers Ragueneau and Bressani were also in that Huron Country. It is, therefore, more than reasonably certain, that all three of them being Europeans, all three living among the Hurons,—whose territory was not large, through which news of the presence of white men in those days traveled fast,—that they must have known each other, not only as acquaintances, but as intimates. The Priests had their headquarters at the Home of the Huron Mission, and the Docteur would, for every reason, take up his residence in that same Indian Village. Those three men,—with the exception of Champlain, the earliest known chroniclers of the existence of Niagara Falls,—were doubtless near neighbors and close friends, in the Huron Country, in the wilds of Canada, over two hundred and fifty years ago.

In 1636, there had been published at Paris a work in five volumes, written by one Pierre Davity, who had died the year before, entitled "The Whole World; With all its Parts, States, Empires, Kingdoms, Republics and Governments." It had been reissued at least twice by 1649. In all three of those Editions, "America, The Third Part of the World," had been treated of at some length—especially the Southern Hemisphere;—and while Canada had not been overlooked, there had been no mention of Niagara.

In 1660, Jean Baptiste de Rocoles, who was both a Counsellor to the King and also his State Historian, reissued the work, enlarged and "brought up to date." This issue was in three volumes, folio; rather ponderous tomes; well printed, and elaborately bound. As in the previous editions, it was issued by consent of the King, and with the approval of the Clergy; and it now had the official editing of the King's Historian.

At the end of the portion relating to America—that is, at the very end of the last volume—its contents evidently coming to Rocoles' notice at the last moment; probably after the work was entirely printed (for the preceding page bears the imprint, "End of America"; and there is no mention of its contents in the Index), is a short Chapter entitled (translated),

"Certain Special Information about the Country of the Hurons in New France. Recorded by the Sieur Gendron, Doctor of Medicine, who has lived for a long time in that Country."

This supplementary Chapter is six pages in length, and, while it is not signed, we may justly assume that Rocoles himself, and none other, wrote it. It begins,—

"One of my friends having lately placed in my hands a few letters written in the years 1644 and 1645, which Sieur Gendron, native of Voue in Beausse, had sent to him from that Country [of the Hurons], where he was at that time; I have had the curiosity to transcribe from them, word for word, what follows; for a better knowledge and acquaintance of those lands, newly discovered. And I have done so the more willingly because this person is worthy of credence, and he wrote these letters to men of merit, who had travelled much."

In the letters thus transcribed, "word for word," Sieur Gendron gives the location of the Huron Country, where he writes,—

"I now am," "as between the 44th and 45th degrees of Latitude; and as to Longitude, it is half an hour more to the west than Quebec."

From his descriptions of the Lake Region, from his location of other Indian tribes, and from the context, Sieur Gendron was very near the southern end of Georgian Bay, when he wrote those letters. That he was in the same Indian Village, as was the House, or Headquarters, of the Mission to the Hurons (which was located at that point), is deducable even more strongly, from the fact, that Father Ragueneau, in his report to his Superior, in 1648, uses, word for word, over more than a score of printed lines, in locating the adjoining Indian tribes, the language of Sieur Gendron, written at least three, possibly four, years before, and published by Rocoles in 1660.

That he did so, not plagiarizing, but with the knowledge and consent, and not improbably (in those parts of his letter which dealt with physical conditions) with the assistance, of Docteur Gendron, must be admitted by those who know from history of the splendid abilities, the exalted piety, and the noble character of Father Paul Ragueneau, S.J., who, after his labors amongst the Hurons were ended, became the Superior of his Order at Quebec—that is, in Canada.

A little further on, Docteur Gendron writes,—

"Towards the south, and a little towards the west, is the Neuter Nation, whose villages, which are now on the frontier, are only about thirty leagues distant from the Hurons. It is forty or fifty leagues in extent" [that is from west to east, for it extended from the Detroit River to some distance east of the Niagara River].

Then he writes, what for the purpose of this article is the most interesting portion of the letters, as follows:

"Almost south of the Neuter Nation is a large lake, almost 200 leagues in circumference, called Erie, which is formed from the Fresh Water Sea, [Lake Huron] and falls, from a terrible height, into a third lake called Ontario, which we call St. Louis.

"From the foam of the waters, roaring at the foot of certain large rocks, which are found at this place, is formed a stone, or rather pulverized salt, of a somewhat yellowish color, of great virtue for healing wounds, fistulas, and malignant ulcers. In this place, full of horrors, live also certain savages, who live only on elk, deer, buffalos, and all other kinds of game that the rapids drag and bring down to the entrance of these rocks; where the savages catch them, without running for them, more than sufficient for their needs, and the maintenance of strangers [Indians from other and distant tribes], with whom they trade in these 'Erie Stones' ['Pierres Eriennes']—thus called because of this lake—who carry and distribute them to other Nations."

In confirmation of the Doctor's statement that articles were brought to Niagara, for the purposes of trade,—in 1903 there was opened an Indian Mound, on top of and close to the edge of the Mountain Ridge, some three and a half miles east of the Niagara River, on the Tuscarora Reservation, in the town of Lewiston, Niagara County, N.Y. It was a Burial Pit; and a Peace Burial Pit; more than probably dating from 1640, which was the last date of the ten-year Ceremonial Burials observed by the Neuters, who then owned and occupied all this Niagara Region; for before the expiration of the next ten year period, the Neuters had been annihilated by the Senecas. In it were found nearly 400 skulls, and the bones of probably an equal number of bodies, some articles of copper (made by the French, and proving trade with them), many hundreds of shell beads, and other articles of Indian make, among them some made from large Conche Shells, such as are found on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, and curiously enough three or four large, unbroken, Conche Shells. These latter, it is fair to assume, were brought nearly 2,000 miles, to Niagara, there to be traded for those "Erie Stones" (and they were brought unbroken, so that their buyer could cut from them gorgets and other ornaments of the shape and size that suited his fancy), thus proving, that for some years, no one can pretend to say how many, perhaps centuries before Docteur Gendron wrote the second known reference to Niagara, the fame of the Cataract was widely known among the Indians of North America; even beyond the far-off, sunny lands, inhabited by the Arkansaws; clear to the mouths of the Mississippi, "The Father of Waters," and along the shores of the Gulf of Mexico.

So it was a Physician, in a letter written from an unnamed place in the wilds of Canada, to a friend, of whose name we are ignorant, in France,—the contents of which letter were, in a few years, to be published to the World,—that was, in date the second, though in print the fourth, man ever to refer directly to Niagara Falls.

Yet, it is not surprising that it should have been so, for almost every instance in History tells us that, so far as newly discovered lands are concerned, it is the Explorer, or Empire-Builder, who first penetrates them, and the Priest soon follows the explorer, and the Physician soon follows the Priest. And that was exactly the order which was followed in the explorations of the Great-Lakes-Region of North America.

The Quartette—the third was an Italian, the other three were Frenchmen—who first referred directly to Niagara in print, stands—Champlain, Ragueneau, Bressani, Gendron, and in that order:—A Soldier of the Sword; two Soldiers of the Cross; and a Soldier of Medicine—though, so far as the dates when the letters of those four were written, and the information thus put in form which made its publication possible, are concerned, the Physician, Gendron, should occupy the second—instead of the fourth place. And, by-the-way, this Sieur Gendron was the first white Physician who is known to have lived anywhere in the western portion of this Country; the first white Physician in the limits of the present province of Ontario in Canada; and the first white Physician among the Indians of North America.

In the case of the good Docteur Gendron—who, next to Champlain, was the earliest to mention Niagara,—it was not the scenic beauty of the Falls (he does not say that he ever saw them), but it was something in the direct line of his profession which caused him to refer to them. It was because, at their base, and created, as he was told, by their waters, there was found—and there only—a panacea for many, if not for all, human ills. From his statements, it seems clear, that those "Erie Stones," which were "found only at Niagara," were themselves widely known amongst the Savages; and were a considerable article of trade between many, even to the most distant, Tribes.

And, even as to the minds of the Aborigines who dwelt far from it, the triple importance of Niagara was that it necessitated a long Land Carriage or Portage in their canoe voyages, that it was a famous "trading place," and, that it was the only source of supply of those famous "Erie Stones"; even so, to the mind of Docteur Gendron, their main importance lay, not in their imagined grandeur, but in the authenticated statement, that it, and it alone, produced a stone or powder, efficacious in the treatment of certain ills; which was undoubtedly a very welcome and a very decided addition to the probably very limited stock of his Materia Medica. Thus, Niagara, which to-day is famous the World over, for its Scenery, for its Botany, for its Geology, for its History, for its Hydraulic works, and lastly (and almost equally with its Scenery), for its Electrical developments, has also, through Docteur Gendron's "hasty letter"—written in 1644 or 1645—a distinct, and a very, very early claim to a place in the annals of the Healing Art—as it was known and practiced on the Continent of North America, during the first half of the 17th Century; and also therefrom another distinct proof that the locality was an Aboriginal Center of Trade.

This "Trade" in those "Erie Stones" must have been a most important thing for those Savages,—the Onguiaahras—who dwelt close to the Cataract at that time, and prior thereto.

It is further a most interesting fact, that the "Trade" therein was the first recorded trade ever carried on at Niagara; and it is also most interesting to recall, that this first Trade, at this famous spot, was in an article used for the relief of human suffering,—a simple remedy, furnished by Nature, and "all ready for use."

That Niagara product; which, possibly long before Columbus landed at San Salvador, probably during all the 16th, certainly during the 17th Century; made the locality famous, far and wide; was among the earliest known of America's healing remedies. It was evidently a leading, and a much-sought-for, prescription among the Aborigines. To-day, it has no value whatever. It is still to be found in abundance in the immediate vicinity of the Falls, in the Gorge below them; but no one seeks to gather it, save as a curiosity.

But, in those early days, among the ignorant and phenomenally superstitious Savages, those "Erie Stones," to be "found only at Niagara," seemed to them a special gift from the Great Spirit to his children. To the Savages, they were, veritably, "Big Medicine."

Their fame lasted for many a year. They were gathered and traded in—yes, and used—even until the middle of the 18th Century. As late as 1787, their reputation still clung to the great Fall.

That year, Capt. Enys, of the 29th Regiment, British, was at Niagara, and wrote of them—they were no longer called "Erie Stones," but the substance was known as "petrified spray of the Falls,"—

"On our return" [from the base of the Fall, and walking along the water's edge, under the cliff], "we employed ourselves in picking up a kind of stone, which is said to be the Spray of the Fall, petrified, but whether it is or no, I will not pretend to determine; this much I can say, that it grows, or forms itself in cavities in the cliff, about half way to the top, from whence it falls from time to time; its composition is a good deal like a piece of white marble which has been burnt in the fire, so that it may be pulverized with ease. Whatever may be its composition, it does not appear that it will bear to be exposed to the air, as some pieces which seem to have fallen longer than the rest are quite soft; while such as had lately fallen are of a much harder nature."

Robert McCauslin, M.D., who, during and after the War of the Revolution, spent nine years at Niagara—undoubtedly as British Post Surgeon at Fort Niagara,—furnished a scientific paper entitled, "An account of an earthly substance, found near the Falls of Niagara, and vulgarly called the Spray of the Falls," to Dr. Benjamin Smith Barton; and he, on October 16, 1789, communicated it to the American Philosophical Society; in whose Transactions it was subsequently published. Dr. McCauslin specially noted, that

"This substance is found, in great plenty, everywhere about the bottom of the Falls; sometimes lying loose among the stones on the beach, and sometimes adhering to the rocks, or appearing between the layers upon breaking them. The masses are of various sizes and shapes, but seldom exceed the bulk of a man's hand. Sometimes they are of a soft substance and crumble like damp sugar; while other pieces are found quite hard, and of a shining, foliated appearance; or else opaque and resembling a piece of burnt allum. It often happens that both these forms are found in the same mass. Pieces which are taken up whilst soft soon become hard by keeping; and they are never known to continue long in a soft state, as far as I have been able to learn."

He records that it is not found at all above the Falls, in the greatest amounts in the Gorge, close to the Falls; and in decreasing quantities as the distance from them increases; and is never found at a greater distance from them than perhaps a mile. From several scientific experiments which he made upon this substance, he deduced,

"1st, That this concrete is not an alkaline earth, as it is not affected either by the vitriolic or vegetable acids.

"2d, That we may, with more probability, say that it is a combination of an acid with a calcareous earth, and that it might with propriety be ranked amongst the selenites."

He thought it was formed by the moisture arising from the Falls constantly and slowly filtering between the layers of rock, in whose crevices it deposited its heavier portions, and that the violent agitation which the water had undergone disposed it to part with its earth more easily than it would otherwise do.

He adds, "The circumstance of this Spray not being found above the Falls seems to suggest an opinion that that part of the vapor which hangs upon the surrounding rocks is the heaviest, as being most loaded with earthy particles, whilst the remainder which mounts up is the purest and contains little or no earth."

Dewit Clinton, when he visited Niagara in 1810—as a Member of the first Board of Commissioners, appointed by the State of New York, to report on the whole subject of the proposed Erie Canal, noted in his diary,

"A beautiful white substance is found at the bottom of the Falls; supposed by some to be Gypsum, and by the vulgar, to be a concretion of foam, generated by the forces of the Cataract. But it is unquestionably part of the limestone, dissolved and re-united."

Since Clinton's time no attention has been paid to this substance as a curative agent.

As a geological substance it is still collected, but with greater ease than formerly, for, besides being found on and below the face of the cliff, its existence in the limestone all over the vicinity of the Falls has been demonstrated by means of the huge excavations that have been made in the development of the various Power Plants at Niagara.

CHANGES OF CONTOUR

Wonderful changes have taken place in the contour of the greater Fall at Niagara since Docteur Gendron recorded that the Indians traded in those "Erie Stones." The additional Fall, which Father Hennepin pictured in 1697, as pouring eastward from the Canadian end of the Horse Shoe Fall, was formed by the waters flowing around a large rock, which stood at the very edge of the cliff. Before the middle of the 18th Century that rock had disintegrated and been swept away; and that separate Fall then merged itself into the greater cascade; as is shown in a view of Niagara accompanying Peter Kalm's description thereof in 1751. But it must be remembered that in Hennepin's time that Canadian end of the Horse Shoe Fall extended very much farther down the Gorge than it does to-day—probably 800 feet farther. That Fall then extended its shallow end down to where old Table Rock stood. Then the levels of all the upper lakes were higher than they are to-day, those levels having been considerably lowered through the white man's denudations of the forests in the Basin of the Great Lakes. As the downpour of Niagara thereby diminished in volume, that end of the Canadian Fall receded; so that, as far as can be deduced, that Fall was some 400 feet shorter in contour (all taken off its western end) in 1900 than it was when Hennepin saw it—two and a quarter centuries before. Since 1900, the policy of the Province of Ontario, to turn its share of Niagara into cash—in renting out to corporations the right to use the waters of the Cataract for the development of electrical horsepower ("at so much per")—has resulted in still further shortening the contour of the Horse Shoe Fall, by another 400 feet. The contour of that Fall was given by survey in 1840 as 3,060 feet. Hence, in Hennepin's time, it must have been about 3,500 feet. To-day, owing to the filling in of the old river-bed, along the edge of the precipice at the Cataract's western end, that contour line would not be more than 2,700 feet.

But it must be recalled that the recession at the apex of that Fall has been very marked since 1840; and as that recession is V shaped it has added somewhat—fully two hundred feet—to the figures of that old contour line; making the contour line of the Falls to-day about 2,900 feet.

By reason of that shortening of that Fall, two scientific questions are brought up in regard to those deposits of gypsum, or "Petrified Spray of the Falls."

First—to what extent has that concretion formed behind the falling water? Has it formed there in greater quantities than it has where the face of the cliff has been open to the air? In greater quantities might have been expected, on account of the greater amount and absolute continuity of the moisture on the rocky face. The 400 feet length of cliff, from which the waters have now been permanently shut off, furnishes the answer. Practically, none of that concrete has ever accumulated in the crevices of the rock on the face of the cliff immediately behind the Falls. The currents of air, and the furious blasts of water which they create, rush constantly away from the under surface of the falling sheet, and continuously against the face of the cliff. These scour and cut away the rock, even as a sand blast would do, though more slowly. They allow no chance for deposits. The strata of the Clinton Formation (which commences at about the level of the water in the Gorge, and of the Niagara shale, which overlie it—the two combined having a depth of about eighty feet) are eaten away the faster. The eighty-feet-deep layer of Niagara Limestone, which overlies the shale, being harder, is eaten away slowly; its lower layers being attacked by the winds and waters from below (as the underlying shale disappears) and also on its face, yielding faster than the upper ones.

That this concretion has always formed in the limestone, back from the face of the cliff, behind the falling sheet (where the blasts of wind and water cannot reach nor effect it) is certain.

That it forms under the river bed, and back from the face of the gorge on both sides of the river, and wherever the water percolates through the upper layer of rock, is also certain.

It is so found in the limestone (but not in the shale) wherever deep excavations have been made near the river in the vicinity of the Falls and wherever tunnels have been driven through the limestone—in the crevices and especially where a pocket or hollow space exists in that formation.

This process of eating away the lower rocks, undermining the upper limestone, which, as its support is taken away, tumbles into the Gorge, shows the means by which the Falls gradually recede.

It is shown to the best advantage in the Cave of the Winds, which, during the past thirty years, by this wind-and-water-blast process, has been enlarged to four times its former size. Some day the layer of rock at the top of that cave will fall; the edge of the Luna Island Fall will be thus moved back a number of feet; the Cave of the Winds will become merely a narrow space between the outward-curving fall of water and the perpendicular rock; and the wind-and-water-blast will continue its erosive work on that rocky face;—and in the course of years will again produce a distinct cave.

The other scientific question—which the future will answer—is, How fast does this Niagara concrete form? With that 400 feet length of cliff on the Canadian shore—which was formerly covered by the end of the Horse-shoe Fall—exposed to the air and to observation (the outer end of those crevices in its face being now free from any such deposit); with the extensive excavations on the debris slope for the Power House below the bank, exposing new surfaces, where little such deposit now appears; with other probable excavations in connection with the power development, exposing similar surfaces at other points along the Gorge; it will be possible to approximately determine the yearly amount of accumulation and deposit of this ancient Niagara product. For that deposit will go on as ceaselessly as it has been going on, ever since the time—possibly many thousands of years ago—when the waters of a great lake (which was formed by the melting of the ice sheet) covered all this region; finally breaking over its northern barrier at the Lewiston escarpment, where, seven miles from its present location, Niagara was born.

STILL A TRADE CENTER

Le Sieur Gendron, of whom we know nothing more than is contained in the printed letters, noted before, passed away many a year ago; but at this late date, some two and a half centuries after his death, a lover of Niagara, in his search for and his collecting of early books that in any way refer to its famous Cataract, secured a copy of De Rocoles' "America, the Third Part of the World," 1660, which contains the first publication of Docteur Gendron's interesting letters from, and about, the Huron Country, in Canada. Therein he found this remarkable reference to the Waterfall,—which was quoted verbatim from the good Docteur's "hasty letter," by the State Historian of King Louis of France,—and is thereby enabled to add an hitherto unknown link (which turns out to be the second) in the chain of the earliest references to Niagara Falls; and so, both in History and in Medicine, to assign to good Docteur Gendron, a place (next alongside of the great Founder of Quebec) in Niagara's Temple of Fame. For the Sieur Gendron probably wrote from actual knowledge; he had probably, through some Huron emissary, secured some of those "Erie Stones," that "Petrified Spray of the Falls" in trade, at Niagara; he had doubtless tried the healing qualities thereof on some of his Savage Patients—and let us hope that this Niagara Remedy proved efficacious, and justified its wide-spread reputation. At any rate, in recording its uses, and its distribution by "Trade," and by probably himself using it in his Practice—limited then to the Huron Indians; and the few Frenchmen (perhaps a score or more) who then made their headquarters at the Home of the Jesuit Mission to the Hurons,—he showed, even as many a good Physician of later days has done, that he was a believer in, and user of, every one of Nature's Remedies, as furnished by her to man, and in their simplest forms; and if that Niagara product benefited his savage patients (mainly because they had faith that it would do so) surely the good Docteur earned his professional fee—which he probably had to take in trade—that is, in furs.

Niagara, meaning thereby the Niagara Frontier, or, more properly, that portion thereof which extended from Lake Ontario to about two miles above the Falls (which included Fort Niagara, and the whole of the famous Portage around the Cataract) even in Aboriginal days, before the first Fort Niagara was built, when the Indians applied the word Onguiaahra to the same territory, by reason of its accessibility, its central location, its Portage and its "Erie Stones," was widely known as a "Center of Trade." When the French became the masters of this region its main importance lay in its portage; and the same is true of it under British rule; and also under United States ownership, down to 1826, when the Erie Canal was completed.

And during all those three periods it was indeed a Trade Center. For over it passed on their westward way, all the soldiers, French, British, and American, who built or won, and garrisoned every fort and trading post in the West. All the cannon, equipments, arms, ammunition, clothing of all kinds, tools, most of the food (all of it save the fish they caught, the game they shot, and the few vegetables they raised) which sustained life in the poorly-fed garrisons in those far off posts on the upper Lakes; most of the necessities, everyone of the luxuries,—every pound of coffee, of tea, of sugar, of tobacco, of salt, of flour, of dried and salted meats, every bit of medicine, every gallon of rum;—all those and many other articles had to go to them, annually, by "way of Niagara." There was no other feasible way of transporting goods to the West. In fact there was no other way, save by the Ottawa and through the Georgian Bay; and on the Ottawa, there were forty-two portages, whereas via Niagara there was but the one. And under both French and British rule, Niagara was a great Center of Trade, in furs, and an enormous trade it was. Both the military and the commercial trade of half a Continent flowed by its doors; and both, going eastward and westward, required unloading and transporting over its seven miles of portage.

At one time, in 1764, when provisions were being forwarded to the West for the use there of Gen. Bradstreet's Army, it is recorded that over 5,000 barrels of provisions alone lay at Fort Schlosser, the upper terminus of Niagara's portage, awaiting shipment to the West. By Niagara also went—had to go, for besides being the only feasible route, it was the only safe way, for it had military protection,—all the traders, with their boat loads of cheap merchandize; men who spent months at a time in journeying among the tribes in the Northwest, trading their wares for valuable furs; all of which peltries, in turn, they had to bring east "by Niagara."

With the opening of the Erie Canal, in 1826, all that portaging business at Niagara disappeared; and Niagara, that is the territory immediately adjoining the Cataract, became a famous Watering Place; which character it has ever since retained, and always will retain.

In the early days of that scenic glory it still preserved a tinge of its ancient aspect, as "An Aboriginal Center of Trade." For many years Indian bead-work was one of the main attractions offered in the Bazaars there. And the elder generation of visitors will recall the familiar sight of aged Indian Squaws, and dusky Indian Maidens, who daily, during the season of travel, sat at various points along the route of the tourist—on the steep banks of the road leading up the hill to Goat Island, beneath the trees, close to the rapids, on Luna Island, alongside the path leading down the bank on Goat Island to old Terrapin Tower, and at various points around the Ferry House, and what is now Prospect Park—offering for sale, crude bead work, pincushions, mocassins, etc.

Often a pappoose, strapped to the board which formed the back of its picturesque but doubtless uncomfortable cradle, gazed stolidly at the pale faced visitor, as the cradle leant up against the foot of a tree, or swung suspended from some low-hanging branch. The "Braves" at home then made the toy canoes, the bows and arrows, the quivers, the war clubs and tomahawks, which the squaws also disposed of to tourists as souvenirs of Niagara.

Those "Squaw Traders" were a most picturesque feature of Niagara, and the fact that those descendants of a passing Race now seldom or never sit by the roadside and offer their wares directly to the visitor is a distinct loss to the artistic environment of the Cataract.

In those days also some enterprising genius devised the scheme of manufacturing trinkets—such as watch charms, seals, etc.,—out of that Niagara gypsum, or "Petrified Spray of the Falls"; thereby unconsciously reviving the Aboriginal Trade in that substance, which Docteur Gendron had so early recorded—only this time without any pretension that it possessed any healing qualities—but that trade was neither so famous nor so wide spread, nor so long continued, as the original.

The projectors of the Village at the Falls of Niagara, named it Manchester, in the belief that by reason of its water power (and they then contemplated the use of only a fractional part thereof—not enough to have offered any danger of "Ruining Niagara") it would develop into a manufacturing center which should rival its British prototype.

To-day, through its hydraulic developments, mainly devoted to the generation of electric power, Niagara has again become a really great Center of Trade. How great this locality is destined to become—when the stupendous works, now either in operation or under construction, shall have been completed up to the limits of their rights—whether that enormous development (over a million horse-power on both sides of the river, equal to one-quarter of the total estimated power of Niagara) shall build up a great International Manufacturing Community within close sight of the ever-ascending spray cloud; or whether the most of that power shall be utilized at far distant points, and Niagara be known commercially rather as the Producer of Power than as itself an Enormous Center of Trade—Time alone will tell. But, however great or less that growth shall be—by reason of its power, of its central location, of its accessibility, of its more than a million annual visitors—it will always be, what it is to-day, what it was in "Aboriginal days," a "Center of Trade."

***END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NIAGARA***

******* This file should be named 31955-h.txt or 31955-h.zip *******

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/9/5/31955

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://www.gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS,' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance