The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 14, No. 81, July, 1864, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 14, No. 81, July, 1864 Author: Various Release Date: April 1, 2010 [EBook #31838] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ATLANTIC MONTHLY *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections.)

TICKNOR AND FIELDS,

LONDON: TRÜBNER AND COMPANY.

M DCCC LXIV.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1864, by

Ticknor and Fields,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

| Beer-Drinking, Head-Quarters of | Andrew Ten Broeck | 185 |

| Biography, The New School of | Gail Hamilton | 579 |

| Cadmean Madness, The | W. L. Symonds | 265 |

| Columbia River, On the | Fitz-Hugh Ludlow | 703 |

| Communication | D.A. Wasson | 424 |

| Cullet | Jane G. Austin | 304 |

| Currency | George S. Lang | 109 |

| Democracy and the Secession War | C. C. Hazewell | 505 |

| Dixie, Our Last Day in | Edmund Kirke | 715 |

| Dolliver Romance, A Scene from the | Nathaniel Hawthorne | 101 |

| Electric Girl of La Perrière, The | Robert Dale Owen | 284 |

| England and America | Prof. Goldwin Smith | 749 |

| English Authors in Florence | Miss K. Field | 660 |

| Foreign Relations, Our Recent | G. M. Towle | 243 |

| Glorying in the Goad | Gail Hamilton | 21 |

| Gourgues, Dominic de, The Vengeance of | F. Parkman | 530 |

| Halcyon Days | Caroline Chesebro | 675 |

| Hawthorne | O. W. Holmes | 98 |

| Highland Light, The | H. D. Thoreau | 649 |

| House and Home Papers | Harriet Beecher Stowe | 93, 230, 434, 565, 689 |

| How Rome is Governed | Prof. G. W. Greene | 150 |

| Ice and Esquimaux | D. A. Wasson | 728 |

| Ice-Period in America | Prof. Louis Agassiz | 86 |

| Inanimate Things, The Total Depravity of | Mrs. E. A. Walker | 357 |

| Jones, Paul, and Denis Duval | F. Ingham | 493 |

| Lamb's, Charles, Uncollected Writings | J. E. Babson | 478, 552 |

| Leaves from an Officer's Journal | T. W. Higginson | 521, 740 |

| Lina | 538 | |

| Little Country-Girl, The | Mrs. A. M. Diaz | 212 |

| Luigi, The True Story of | Harriet E. Prescott | 411 |

| Mexico | G. Reynolds | 51 |

| Meyerbeer | Francis Williams | 116 |

| Night in the Water, A | T. W. Higginson | 393 |

| Oregon, On Horseback into | Fitz-Hugh Ludlow | 75 |

| Paris, Literary Life in | "Spiridion" | 200, 292 |

| Presidential Election, The Twentieth | C. C. Hazewell | 633 |

| Reade, Charles | Harriet E. Prescott | 137 |

| Récamier, Madame | Miss J. M. Luyster | 446 |

| Regular and Volunteer Officers | T. W. Higginson | 348 |

| Revolution, Finances of the | Prof. G. W. Greene | 591 |

| Richmond, Our Visit to | Edmund Kirke | 372 |

| Rim, The | Harriet E. Prescott | 63 |

| Saadi | R. W. Emerson | 33 |

| San Francisco, Through-Tickets to | Fitz-Hugh Ludlow | 604 |

| Sculpture, The Process of | Harriet Hosmer | 734 |

| Sea-Hours with a Dyspeptic | Joseph D. Howard | 617 |

| Vendue, On a Late | J. E. Babson | 406 |

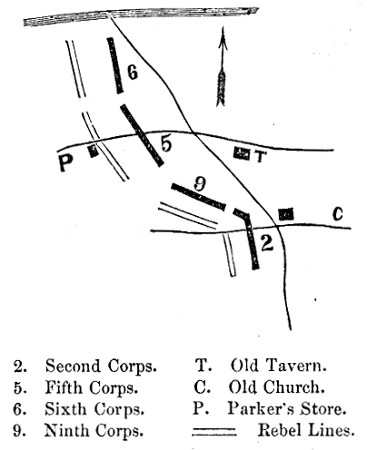

| Virginia, The May Campaign in | "Carleton" | 124 |

| We are a Nation | J. T. Trowbridge | 769 |

| Wellfleet Oysterman, The | H. D. Thoreau | 470 |

| [Pg iv] | ||

| Wet-Weather Work | Donald G. Mitchell | 39, 333 |

| What shall we have for Dinner? | E. E. Hale | 364 |

| What will become of Them? | J. T. Trowbridge | 170, 320 |

| Wife's Story, The | Author of "Life in the Iron-Mills" | 1 |

| Before Vicksburg | G. H. Baker | 371 |

| Bridge of Cloud, The | H. W. Longfellow | 283 |

| Bryant, To William Cullen | H. T. Tuckerman | 563 |

| Bryant's Seventieth Birthday | O. W. Holmes | 738 |

| Concord | H. W. Longfellow | 169 |

| Divina Commedia, On Translating the | H. W. Longfellow | 688 |

| Forgotten | Elisabeth A. C. Akers | 332 |

| Friar Jerome's Beautiful Book | T. B. Aldrich | 195 |

| Heart of the War, The | J. G. Holland | 240 |

| In Memory of J. W.—R. W. | O. W. Holmes | 115 |

| Last Rally, The | J. T. Trowbridge | 589 |

| Maskers, The | J. T. Trowbridge | 303 |

| Palingenesis | H. W. Longfellow | 19 |

| Return of the Birds, The | W. C. Bryant | 37 |

| Riches | 530 | |

| Ride to Camp, The | G. H. Boker | 404 |

| Service | J. T. Trowbridge | 443 |

| Summer, The Future | 503 | |

| Sweet-Brier | 229 | |

| Tobacconalian Ode, A | 672 | |

| Vanishers, The | J. G. Whittier | 726 |

| Watching | 74 | |

| Works and Days | T. W. Parsons | 491 |

| Arnold on Translating Homer | 136 |

| Arnold's Last Words | 136 |

| Browning's Dramatis Personæ | 644 |

| Carter's Summer Cruise | 515 |

| Dufour's Strategy and Tactics | 259 |

| Farnham's Eliza Woodson | 388 |

| ---- Woman and her Era | 388 |

| Greeley's American Conflict | 133 |

| Guizot's Meditations on Christianity | 784 |

| Haupt on Military Bridges | 781 |

| Hazard on Freedom of Mind in Willing | 778 |

| Jennie Juneiana | 387 |

| Kingsley's Roman and Teuton | 252 |

| Marsh's Man and Nature | 261 |

| Mill's Dissertations and Discussions | 776 |

| Newman's Translation of the Iliad | 135 |

| Owen's Wrong of Slavery | 517 |

| Parton's Life and Times of Franklin | 383 |

| Prescott's Azarian | 515 |

| Privations and Sufferings of U.S. Soldiers in Rebel Prisons | 777 |

| Reid's Cliff-Climbers | 390 |

| Tennyson's Enoch Arden | 518 |

| Thoreau's Maine Woods | 386 |

| Trollope's Small House at Allington | 254 |

| Webster's American Dictionary | 642 |

| Wilson's History of the Anti-Slavery Measures of Congress | 787 |

| Youmans's Class-Book of Chemistry | 256 |

| Recent American Publications | 136, 263, 391, 648, 788 |

I will tell you the story of my life, since you ask it; for, though the meaning of the life of any woman of my character would be the same, I believe, the facts of mine, being sharp and compressed, may make it, perhaps, more apparent. It will be enough for me to give you the history of one day,—that of our first coming to Newport; for it seems to me as if it held and spoke out plainly whatever gist and significance there was in all the years for me. I know many people hold the theory, that once in every life God puts the stuff of which He has made the man or woman to the test, gives the soul a chance of a conscious fight with that other Power to win or lose itself, once for all. I do not know: it seems but just that one should be so left, untrammelled, to choose between heaven and hell: but who can shake off trammels,—make themselves naked of their birth and education? I know on that day when the face of my fate changed, I myself was conscious of no inward master-struggle: the great Life above and Life below pressed no closer on me, seemed to wait on no word of mine. It was a busy, vulgar day enough: each passing moment occupied me thoroughly. I did not look through them for either God or Death; and as for the deed I did, I had been drifting to that all my life: it began when I was a pampered, thin-blooded baby, learning the alphabet from blocks on my mother's lap; then years followed, succulent to satiety for my hungry brain and stimulated tastes; a taint of hereditary selfishness played its part, and so the end came. Yet I know that on that day I entered the gate through which there is no returning: for, believe me, there are such ways and gates in life; every day, I see more clearly how far and how immovably the paths into those other worlds abut into this, and I know that I, for one, have gone in, and the door is closed behind me. There is no going back for me into that long-ago time. Only He who led me here knows how humbly and through what pain I dared to believe this, and dare to believe that He did lead me,—that it was by no giddy, blear-sighted free-will of my own that I arrived where I stand to-day.[Pg 2]

It was about eighteen months after my marriage that we came to Newport. But let me go back a few weeks to one evening when my husband first told me of the failure of the house in which his property was invested; for it was then, I think, that the terror and the temptation which had beset my married life first took a definite shape and hold on me.

It was a cool September evening, I remember: a saffronish umber stain behind the low Hudson hills all that was left of the day's fresh and harvest-scented heat; the trails of black smoke from the boats against the sky, the close-shut cottages on the other shore, the very red cows coming slowly up from the meadow-pool, looking lonesome and cold in the sharp, blue air. In the library, however, there was a glow of warmth and light, as usual where Doctor Manning sat. He had been opening the evening's mail, and laid the last letter on the table, taking off his glasses in his slow, deliberate way.

"It is as we feared," turning to me. "It's quite gone, Hester, quite. I'll have to begin at the beginning again. It would have been better I had not trusted the whole to Knopps,—yes."

I said nothing: the news was not altogether unexpected. He took off his wig, and rubbed his head slowly, his eyes fixed on my face with some anxious, steady inquiry, which his tones did not express.

"I'll go back to Newport. Rob's there. I'll get a school again. You did not know I taught there when I was a young man?"

"No."

I knew nothing of my husband's youth. Miss Monchard, his ward, who was in the room, did, however; and after waiting for me a moment to go on, she said, cheerfully,—

"The boys will be men now, Sir. Friends ready waiting. And different sort of friends from any we have here, eh?"

He laughed.

"Yes, Jacky, you're right. Yes. They've all turned out well, even those Arndts. Jim Arndt used to trot you on his knee on the school-house steps, when you were a baby. But he was a wild chap. He's in the sugar-trade, Rob writes me. But they'll always be boys to me, Jacky,—boys."

His head dropped, with a smile still on his mouth, and he began fingering his scanty beard, as was his habit in his fits of silent musing. Jacqueline looked at him satisfied, then turned to me. I do not know what she saw upon my face, but she turned hastily away.

"It's a town with a real character of its own, Newport, Mrs. Manning,"—trying to make her coarse bass voice gentle. "You'll understand it better than I. New-York houses, now, even these on the Hudson, hint at nothing but a satisfied animal necessity. But there, with the queer dead streets, like a bit of the old-time world, and the big salt sea"——She began to stammer, as usual, and grow confused. "It's like looking out of some far-gone, drowsy old day of the Colonies, and yet feeling life and eternity fresh and near to you."

I only smiled civilly, by way of answer. Jacqueline always tried me. She was Western-born, I a New-Englander; and every trait about her, from the freedom with which she hurled out her opinions to the very setting-down of her broad foot, jarred on me as a something boorish and reckless. Her face grew red now.

"I don't say what I want exactly," she hesitated. "I only hoped you'd like the town, that it would reconcile——There's crabs there," desperately turning to Teddy, who was playing a furtive game of marbles under the table, and grabbing him by the foot. "Come here till I tell you about the crabs."

I remember that I got up and went out of the low window on to the porch, looking down at the quiet dun shadows and the slope of yellowed grass leading to the river, while Jacky and the boy kept up a hurly-burly conversation about soldier-crabs[Pg 3] that tore each other's legs off, and purple and pink sea-roses that ate raw meat, and sea-spiders like specks of blood in the rocks. My husband laughed once or twice, helping Jacky out with her natural history. I think it was the sound of that cheery, mellow laugh of his that fermented every bitter drop in my heart, and brought clearly before me for the first time the idea of the course which I afterwards followed. I thrust it back then, as if it had been a sneer of the Devil's at all I held good and pure. What was there in the world good and pure for me but the man sitting yonder, and the thought that I was his wife? And yet——I had an unquiet brain, of moderate power, perhaps, but which had been forced and harried and dragged into exertion every moment of my life, according to the custom with women in the States from which I came. Every meanest hint of a talent in me had been nursed, every taste purged, by the rules of my father's clique of friends. The chance of this was all over,—had been escaping since my marriage-day. Now I clearly saw the life opening before me. What would taste or talent be worth in the coarse struggle we were about to begin for bread and butter? "Surely, we have lost something beyond money," I thought, looking behind into the room, where my husband was quietly going back to the Arndts in quest of food for reflection, and Jacky prosed on about sea-anemones. I caught a glimpse of my sallow face in the mirror: it was full of a fierce disgust. Was their indifference to this loss a mere torpid ignorance of the actual brain- and soul-wants it would bring on us, or did they really look at life and accept its hard circumstances from some strange standing-ground of which I knew nothing? I had not become acclimated to the atmosphere of my husband's family in the year and a half that I had been his wife. He had been married before; there were five children, beginning at Robert, the young preacher at Newport, and ending with Teddy, beating the drum with his fists yonder on the table; all of them, like their father, Western-born, with big, square-built frames, and grave, downright-looking faces; simple-hearted, and much given, the whole party, to bursts of hearty laughter, and a habit of perpetually joking with each other. There might be more in them than this, but I had not found it: I doubted much if it were worth the finding. I came from a town in Massachusetts, where, as in most New-England villages, there was more mental power than was needed for the work that was to be done, and which reacted constantly on itself in a way which my husband called unwholesome; it was no wonder, therefore, that these people seemed to me but clogs of flesh, the mere hands by which the manual work of the world's progress was to be accomplished. I had hinted this to Doctor Manning one day, but he only replied by the dry, sad smile with which it had become his habit of late to listen to my speculations. It had cost me no pain thus to label and set aside his children: but for himself it was different; he was my husband. He was the only thing in the world which I had never weighed and valued to estimate how much it was worth to me: some feeling I could not define had kept me from it until now. But I did it that evening: I remember how the cool river-air blew in the window-curtain, and I held it back, looking steadily in at the thick-set, middle-aged figure of the man sitting there, in the lamp-light, dressed in rough gray: peering at the leather-colored skin, the nervous features of the square face, at the scanty fringe of iron-gray whisker, and the curly wig which he had bought after we were married, thinking to please me, at the brown eyes, with the gentle reticent look in them belonging to a man or beast who is thorough "game"; taking the whole countenance as the metre of the man; going sharply over the salient points of our life together, measuring myself by him, as if to know—what? to know what it would cost me to lose him. God be merciful to me, what thought was this? Oh, the wrench in[Pg 4] heart and brain that came then! A man who has done a murder may feel as I did while I stood for the next half-hour looking at the red lights of the boats going up and down the Hudson, in the darkening fog.

After a while Teddy came waddling out on the porch, in his usual uncouth fashion, and began pulling at my cape.

"You're getting cold, mother. Come in. Come!"

I remember how I choked as I tried to answer him, and, patting his gilt-buttoned coat, took the fat chapped little hands in mine, kissing them at last. I was so hungry for affection that night! I would have clung to a dog that had been kind to me. I thought of the first day Doctor Manning had brought him to me, in this same comical little jacket, by the way, and the strangely tender tone in which he had said,—"This is your mother, boy. He's as rough as a bear, Hetty, but he won't give you trouble or pain. Nothing shall give you pain, if I"——Then he stopped. I never heard that man make a promise. If he had come out instead of Teddy on the porch that night, and had spoken once in the old tone, calling me "Hetty," God knows how different all that came after would have been. The motherless boy, holding himself up by my knees, was more sturdy than I that night, and self-reliant: never could have known, in his most helpless baby-days, the need with which I, an adult woman, craved a cheering word, and a little petting.

Jacqueline came behind me and pinned a woollen shawl around my neck, patting my shoulders in her cozy, comfortable fashion.

"None of your dark river-fogs at Newport," she laughed. "The sea-air has the sweep of half the world to gather cold and freshness in, and it makes even your bones alive. Your very sleep is twice as much sleep there as anywhere else."

Jacky's rough voice was like the cuckoo's: it always prophesied pleasant weather. She went in again now, and sat down on her little sewing-chair. The low, rolling fogs outside, and the sharp September wind rattling the bare branches of the orchard-trees and the bushes on the lawn, only made the solid home-look of comfort within warmer and brighter. There was a wood-fire kindled on the library-hearth, and its glow picked out red flushes of light on the heavy brown curtains, and the white bust of Psyche, and a chubby plaster angel looking down. Jacky, rocking and sewing, her red mouth pursed up, half whistling, suited the picture, somehow, I could not but feel, mere lump and matter though she might be. There was something fresh and spicy about her. I never had been impressed so justly by her as on that night. Rough, perhaps, but it was a pure roughness: everything about the girl had been clean since she was born, you felt, from the paint of the house where she lived to the prayer her nurse had taught her. Her skin was white and ruddy, her blue eyes clear and full of honesty, her brown curls crisp and unoiled. She could not reason, maybe; but she was straightforward and comfortable: every bone in her roly-poly little figure forgot to be a bone, and went into easy cushions of dimpled flesh. If ever Jacky died and went into a more spiritual world, she would be sure to take with her much of the warmth and spring and vigor of this. She had drawn her chair close to Doctor Manning's, where the flickering light touched the soft woollen folds of her dress and the bit of crimson ribbon at her throat. He liked bright colors, like most men of his age. It was a pretty picture.

I turned and looked down at the river again, shivering,—trying to think of the place and all we were leaving. I did not wonder that it cost the others little to give up the house: it meant but little to them. Doctor Manning had bought it just before we were married, being then a square chocolate-colored farm-house, and we had worked our own whims on it to make it into a home, thrusting out a stout-pillared big porch at one side, and[Pg 5] one or two snug little bay-windows from my sewing-room. There was a sunny slope of clover down to the river, a dusky old apple and plum orchard at the left, and Mary's kitchen-garden on the right, with a purblind old peacock strutting through the paths, showing its green and gold. Not much in all this: nothing to please Jacky's artist and poet sense, if she had any. But——I held on to the porch-railings now, drumming with my fingers, as I thought of it. It was all the childhood I ever had known. He brought me there the day we were married, and until August—six months—we had been there alone. I could hear his old nag Tinder neighing now, in the stable where we used to go every evening to feed and rub him down: for I went with Daniel, as I called him, then, everywhere, even to consult his mason or farm-hands. He used to stand joking with them a minute after the business was over, in an unwonted fashion for him, and then scramble into the buggy beside me, and drive off, his fresh, bright eye turned to the landscape as if enjoying it for the first time.

"God bless you, Hetty!" he used to say, "this is putting new blood into my veins."

Generally, in those long rides, I used to succeed in coaxing him imperceptibly back to talk of his life in South America,—not only that I liked to hear this new phase of wild adventuring life, but my own blood would glow and freshen to see the fierce dare-devil look come back into the eye, and the shut teeth of the grave, laconic old Doctor. People did not know the man I had married,—no; and I would draw in closer to his shaggy coat, and spur him on to his years of trading in the West, and later in this State. He had a curious epigrammatic way of talking that I have noticed in a less degree in many Western men: coming at the marrow and meaning of a scene or person in his narration with a sheer subtilized common-sense, a tough appreciation of fact beyond theory, and of its deeper, juster significance, and a dramatic aptness for expression. Added to all this, my husband's life had been compacted, crowded with incident; it had saddened and silenced his nature abnormally; this was the first break: a going back to what he might have been, such as his children were now.

"I never talked to any one before, Hetty," he said thoughtfully once, as we were driving along, after a few moments' silence. "I feel as if I had got breath, this late in the day, that I never expected, for whatever thought was in me,—and—whatever love."

He turned away his face, crimson at this. He was as strangely reticent and tender on some points as a woman. So seldom he put his love into words! That time I remember how the tears suddenly blinded me, when I heard him, and my fingers grew unsteady, holding the reins. I was so happy and proud. But I said nothing: he would not have liked it.

Of one time in his life Doctor Manning had never talked to me: of his earlier youth; when he was married before. He was not a man of whom you could ask questions; yet I had hinted an inquiry once or twice in his presence, but only by a change of color and a strange vague restlessness had he shown that he understood my drift of meaning. Soon after that, his eldest son, Robert, came to see his father's new wife, and stayed with us a day or two. He was a short, thickly built young man, with heavy jaws and black hair and eyes,—keen eyes, I soon felt, that were weighing and analyzing me as justly, but more shrewdly than ever his father had done. The night before he went away he came up to the porch-step where I sat, and said abruptly,—

"I am satisfied, and happy to go now."

"I am glad of that," I said earnestly; for the tenderness of the son to the father had touched me.

"Yes. You cannot know the dread I had of seeing you. I knew the risk he ran in laying his happiness in any woman's hands at his hour of life. But it was hard he never should know a home and[Pg 6] love like other men,"—his voice unsteady, and with an appealing look.

"He never shall need it," I said, quietly.

"You think not?"—his eyes on the ground. "At all events,"—after a pause,—"he is resting like a child now: it will not be easy to startle him to any harsh reality, and," looking up, "I hope God may deal with you, Mrs. Manning, as you deal with my father. Forgive me," as I began to speak, "you do not know what this is to me. It makes me rough, I know. I never yet have forgiven the woman that"——His mother? He caught the look, stopped, pushed his hair back, caught his breath. "One thing let me say," after a moment's silence. "You do not know my father. If he wakens to find his wife is not what he thinks her, it will be too late for me to warn you then. He has been hurt sore and deeply in his life. Your chance is but once."

I did not reply to Robert Manning, nor was I offended: there was too much solemnity in his coarseness. The man's affection for his father was as part of his life-blood, I believed.

My husband came to me when he saw Robert go, and loosened my hands from my face. I clung to him as I never did before.

"What is this hurt he talks of in your life, Daniel? Will I be enough to take it out? Will I?"

He laughed, a low, constrained laugh, holding my shoulders as if I were a bit of a child.

"God knows you are enough, Hetty. I never thought He'd send me this. Rob has been talking to you? He"——

"He is bitter."

"He loves me,—poor Rob!"

"Tell me of those people that hurt you, as he says."

It was a prurient, morbid curiosity that had seized me. A sort of shiver ran over his frame.

"Eh, what, Hetty?"—in a low voice. "Let that go, let that go,"—standing silent a moment, looking down. "Why would we bring them back, and hack over the old dead faults? Had she no pain to bear? We couldn't find that out to speak for her. But God knows it."

I might have known how my question would have ended; for, always, he covered over the ill-doing of others with a nervous haste, with the charity of a man himself sharply sensitive to pain.

"It is healthful to go back to past pain," I said, half dissatisfied.

"Is it so?"—doubtfully, as he turned away with me. "I don't know, child. Now and then He has to punish us, or cut out a cancer maybe. But for going back to gloat over the cure or the whip-lash——No; it will keep us busy enough to find good air and food, every minute for itself"; and, with a ruddy, genial smile, he had stooped and kissed my forehead.

A year had passed since that night. I was standing on the same porch, but I was alone now. My husband sat a few feet from me in his old easy-chair, but no gulf could have parted us so wide and deeply. Robert Manning had said I would have but one chance. Well, I had had it, and it was gone. So I stood there, looking quietly at him and Jacky and the boy. The child had pushed his father's wig off, and his bare head with its thin iron-gray hair fell forward on his breast, resting on Teddy's sleeping cheek. I saw now how broad and sad the forehead was,—the quiet dignity on the whole face. Yet it had been such a simple-hearted thing to do,—to buy that wig to please me! One of those little follies the like of which would never come again.

I went in and sat down as usual, apart, throwing aside from my neck the shawl which Jacky had pinned there, loathing anything she had touched, so real and sharp was the thought about her become, as if the evening's fog and cold had lent it a venomous life. They had made a quiet cozy picture before, which had bitterly brought back our first married days, but it was broken up now. The Doctor's three boys came lumbering in, with muddy shoes, game-bags, and the usual fiery faces and loud jokes after their day's[Pg 7] sport. Jacky threw down her sewing, and went out to see the squirrels drawn, and the Doctor smoothed Teddy's hair, looking after them with a pleased smile. One of the rarest sparkles of our daily life! It was a year since Doctor Manning had brought his children home. They filled the house. Musing on the past now, and trying to look at that year calmly, while I sat by the fire, my husband would fade back in the picture into an unmeaning lay-figure. Was this my fault? Could I help it, if God had made me with a different, clearer insight into life and its uses than these people with their sound beef and muscle, their uncouth rejoicing in being alive? There was work enough in them: a broad-fisted grappling with the day's task or obstacle, a drinking of its pain or success into their slow brains, but nowhere the metre to note the soul's changes, nor the eye to speculate on them. "No," my husband had said to me one day, "we Western people have the mass of this country's appointed work to do, so we are content that God should underlie the hypotheses. We waste no strength in guesses at the reason why."

I remember how intolerably the days of that year dragged even in memory, as I sat there trying to judge them fairly,—how other years of my life thrust them aside, persistently, as foreign, alien to me. These others were to me home,—the thoughts that had held me nearest the divine life: I went back to them, my eyes wet, and my heart sick under my weak lungs. The little village of Concord, away up yonder, where I was born,—I was glad to have been born there: thinking how man not only had learned there to stand self-poised and found himself God, but Nature herself seemed there to stop and reflect on her own beauty, and so root deeper in the inner centre. The slow-dropping river, the thoughtful hills, the very dust-colored fern that covers its fields, which might grow in Hades, so breathless and crisp it is, came back to me with a glamour of quiet that night. The soul had space to grow there! remembering how its doors of thought stood wider open to welcome truth than anywhere else on earth. "The only object in life is to grow." It was my father's,—Margaret Fuller's motto. I had been nursed on it, I might say. There had been a time when I had dreamed of attaining Margaret's stature; and as I thought of that, some old subtile flame stirred in me with a keen delight. New to me, almost; for, since my baby was born, my soul as well as my body had been weak and nauseated. It had been so sharp a disappointment! I had intended my child should be reared in New England: what I had lacked in gifts and opportunities he should possess: there was not a step of his progress which I had not mapped out. But the child was a girl, a weazen-faced little mortal, crying night and day like any other animal. It was an animal, wearing out in me the strength needed by-and-by for its mental training. I sent it to a nurse in the country. Her father had met the woman carrying it out to the wagon, and took it in his arms. "Eh? eh? is it so, little lass?" I heard him say. For days after that he looked paler, and his face had a quiet, settled look, as if he had tested the world and was done with it. The days of Tinder and the paddock and the drives were long gone then. I do not remember that after this he ever called me Hetty. But he was cheerful as ever with the boys, and, the week after, Jacky came.

Why did I think of all this now? Some latent, unconscious jar of thought brought suddenly before me a scene of many years before, a damp spring morning in Paris, when I had gone to Rosa Bonheur's studio, just out of the city, to see her "Horse-Fair": the moist smell of jonquils; the drifting light clouds above the Seine, like patches of wool; but most, the peculiar life that seemed to impregnate the place itself, holding her, as it were, to her own precise niche and work in the world,—the sharply managed lights, the skins, trappings, her disguises on the walls, the stables outside, and the finished work before us, instinct with vigor and an observation as patient as keen. I remembered[Pg 8] how some one had quoted her as saying, "Any woman can be a wife or mother, but this is my work alone."

I, too, had my gift: but one. But again the quick shiver of ecstasy ran through me;—it was my power, my wand with which to touch the world, my "Vollmachtsbrief zum Glücke": was I to give it unused back to God? I could sing: not that only; I could compose music,—the highest soul-utterance. I remember clutching my hands up to my throat, as if holding safe the power that should release me, suffer me to grow again, and looking across the oil-lamp on the table at my husband. I had been called, then,—set apart to a mission; it was a true atom of the creative power that had fired my brain; my birth had placed me on a fitting plane of self-development, and I had thrust it all aside—for what? A mess of weakest pottage,—a little love, silly rides behind Tinker, petting and paltering such as other women's souls grew imbecile without. It was the consciousness of this that had grown slowly on me in the year just gone; I had put my husband from me day by day because of it; it had reached its intolerable climax to-night. Well, it was fact: no fancy. My nature was differently built from others: I could look now at my husband, and see the naked truth about us both. Two middle-aged people, with inharmonious intellects: tastes and habits jarring at every step, clenched together only by faith in a vague whim or fever of the blood called love. Better apart: we were too old for fevers. If I remained with Doctor Manning, my rôle was outlined plain to the end: years of cooking, stitching, scraping together of cents: it was the fate of thousands of married women without means, to grovel every year nearer the animal life, to grow niggardly and common. Better apart.

As I thought that, he laid Teddy down, and came towards me,—the usual uncertain, anxious half-smile on his face with which he regarded me.

"I am sure they will all like my old home, now, lads and all. I'm glad of that. Sure of all but you, Hester. But you say nothing."

"The loss is great."

I shut my lips firmly, and leaned back, for he had put his hard hand gently on my shoulder. It made me turn faint, with some weakness that must have come down to me from my infant days, so meaningless was it. I did not hear his answer; for with the same passionate feebleness I caught the sleeve of his dressing-gown in my fingers, and began smoothing it. It was the first thing I had ever made for him. I remembered how proud I was the evening he put it on. He was looking down steadily at me with his grave, reasonable eyes, and speaking when I looked up.

"I have been knocked up and down so perpetually in my own life: that may be the reason the change did not trouble me as it ought. It makes one feel as if outside matters were but just the tithes of mint and cumin,—a hurly-burly like that which I've lived in. I am sorry. I thought you would grieve least of all, Hester. You are stronger-brained than we Mannings, eh? I was sure the life meant so much more to you than food or raiment."

"What do you mean by the life? Have I found it here, Daniel?"

"No, Hester?"

"I want work fit for me," I said, almost fiercely. "God made me for a good, high purpose."

"I know," cheerfully. "We'll find it, dear: no man's work is kept back from him. We'll find it together."

But under the cheerfulness there was a sad quiet, as of one who has lost something forever, and tries to hide the loss from himself. There was a moment's silence, then I got up, and pushed him down into my chair. I took the gray head in my arms, leaned it on my shoulder, held the thin bits of hair in my hand.

"Why, why, child!"

"Call me Hetty, Daniel. I'd like to think that name belonged to me yet."

"Surely, dear. Why! but—this is just the old times again, Hetty! You'll be bringing me my slippers again."[Pg 9]

"Yes, I will."

I went to the cupboard, and brought them, sitting down on the floor as he put them on. Another of the old foolish tricks gone long ago. There was a look on his face which had not been there this many a day. He had such a credulous heart, so easy to waken into happiness. I took his wrist in my bony hands, to raise myself; the muscles were like steel, the cording veins throbbing with health; there was an indescribable rest in the touch.

"Daniel," I said, looking him full in the face, "I'd like to have no mission in God's world. I'd like to give up my soul, and forget everything but you."

He did not answer. I think now that he understood me then and before far better than I dreamed. He only put his hand on mine with an unutterable tenderness. I could read nothing on his face but a grave common-sense. Presently he unbuttoned my sleeves and the close collar about my throat to let the cool damp blow on me.

"Yes," I said, "it's a fever, Daniel. In the blood. That is all,—with me. I decided that long ago. It will not last long." And I laughed.

"Come," he said, quietly. "I am going to write to Rob now, about our plans. You can help me."

I followed him, and sat down by the table. "There is something in the man stronger than the woman," I thought, doggedly, "inside of blood and muscle." Yet the very galling of that consciousness set me more firmly in the mind to be again free.

A month after that we came to Newport. It was not an idle month. Jacky had proposed a review of my husband's and his sons' clothes, and day after day I had sat by the window looking out on the sluggish Hudson, a hank of patent thread about my neck, stitching patches on the stiff, half-worn trousers. "It becomes us to take care of the pence now," she would say, and go on with her everlasting whistling, La-la. It rasped on my brain like the chirp of the partridge outside in the cedar-hedge. When she would go out of the room sometimes, I would hold my hand to my head, and wonder if it was for this in reality God had made me.

Yet I had my own secret. The work of my life, before I was married, had been the score of an opera. I got it out now by stealth, at night, putting my pen to it here and there, with the controlled fever with which a man might lay his hand on a dear dead face, if he knew the touch would bring it back to life. Was there any waking that dead life of mine? At that time, in New York, M. Vaux was trying the experiment of an English opera in one of the minor theatres. I sent the score to him. It did not trouble me, that, if produced, its first effect would be tried on an uncultured caste of hearers: if the leaven was pure, what matter where it began to work? and no poet or artist was ever more sincere in the belief that the divine power spoke through Him than I. I thought, that, if I remained with Doctor Manning as his wife, this venture mattered little: if I shook myself free, and, taking up my mission, came before the public as a singer, it would open the way for me. For my plan had grown defined and practical to me now.

M. Vaux had left his family at Newport after the season was over. I was to meet him there when we went down, and hear his decision on the score. I met him one day on Broadway, and hinted my vague desire of making my voice also available.

"To sing? did you say sing, Mrs. Manning? go on the stage?"—pawing his chin with one hand.

He was a short, puffy little man, with a bullet head at half-cock in the air, producing a general effect of nostrils on you.

"Sing, eh?" he mumbled, once or twice.

Before this I had been Mrs. Manning, throwing off an opera-score as a careless whim, one of the class to whom he and his like presented arms: he surveyed me now with the eye of a stock-raiser buying a new mule, and set the next evening as the time when I should "drop in[Pg 10] at his house and give him a trill or two.—Keeping dark before the old man yet, eh?" with a wink. I went in the next day, but he declined to pronounce judgment until we came to Newport.

I remember my husband met me at the gate when I returned, and lifted me from the little pony-carriage.

"I'm so glad my girl is taking her drives again,"—his face in a glow,—"coming back with the old red cheeks, too. They're a sort of hint of all the good years coming. We're far off from being old people yet, Hetty." And so went beside me slowly up the garden-walk, his hands clasped behind him, stopping to look now and then at his favorite purple and crimson hollyhocks.

I looked at him askance, as we went through the evening shadows. There was something grand in the quiet of the face, growing old with the depth of sadness and endurance subdued in it: the kindly smile over all. I had brought the smile there. But it would not be for long: and I remember how the stalk of gillyflower I held snapped in my hand, and its spicy odor made me throw it down. I have loathed it ever since. Was my life to be wasted in calling a smile to an old man's face? My husband and M. Vaux were different men; but, on the other side, they were gates to me of different lives: here, a sordid slavery of work; there,—something in me glowed warm and triumphant,—fame and an accomplished deed in life!

Surely these mawkish home-ties were fast loosing their hold on me, I thought, as we went in. I asked no questions as to my husband's plans; no one spoke to me of them. In the few days before our departure I roped up chairs, packed china in straw, sorted clothes into trunks, working harder than the others, and then creeping off alone would hum an air from the score, thanking God for giving me this thoroughly pure, holy message to utter in the world. It was the redemption of my soul from these vulgar taints: it was a sort of mortgage I held on the eternal truth and life. Yet, when no one told me of their plans, when I saw they all held some secret back from me, watching me constantly and furtively, when Jacky buzzed about my husband all day, whispering, laughing, cooking his favorite omelet for breakfast, bringing his slippers at night,—it was like so many sharp stings through stupor. "It's the woman's flesh of me!" I used to say bitterly, when I would have been glad to meanly creep after them, to cuddle Teddy up in my arms, or to lean my head on his father's knees. "I can live it down. I have 'a manly soul.'" For it was part of my creed that Nature was something given us to be lived down in fulfilling our mission.

We went by the evening's boat to Newport. I saw M. Vaux in the outer cabin, as we passed through: he nodded familiarly when Doctor Manning's back was turned, without removing his cigar.

It was stifling below, with the smell of frying meat and numerous breaths. We went on deck, my husband drawing a bench around to shelter me from the keen wind across the bow, and wrapping my flannel hood closer to my throat when we drifted out within scent of salt water. It was a night that waited and listened: the sea silent and threatening, a few yellow, dogged, low breakers running in at long intervals; now and then a rasping gurgle of wind from shore, as of one who held his breath; some thin, brown clouds ragged along the edges of the cold sky, ready for flight.

I sat there thinking how well the meaning of the sea suited my soul that night. It was no work of God's praising Him continually: it was the eternal protest and outcry against Fate,—chained, helpless, unappealing. Let the mountains and the sunshine and the green fields chant an anthem, if they would; but for this solitary sea, with its inarticulate cry, surely all the pain and impatience of the world's six thousand years had gone down and found a voice in that. Having thus cleared to myself the significance of the sea in Nature, I was trying to define its exact effect upon my own temperament,[Pg 11] (a favorite mental exercise of my father's,) when my husband touched my shoulder.

"I'll go down and smoke a bit, Hetty dear, and leave you with Jacky. She's as good guard as a troop of horse."

Jacky nodded vehemently once or twice from where she stood, followed him with her eyes as he went down the steps, anxiously, and then stood gravely silent. She was but a lump of "woman's flesh," that was clear, and I doubted if there was any soul inside to live it down. Her face was red and her eyes shining with the sea-wind. She had been at the stern with the boys, making a riot about the porpoises rolling under the boat; in the engine-room with Teddy; had tried to drag me to the deck-railing to watch the unsteady shimmer of some pale-blue sea-weed under the water, which the wheel threw up in silver flashes, or to see how, before the sun went down, we floated over almost motionless stretches of pale tea-colored water, holding, it seemed, little curdling pools of light far below in their depths on depths of shivering brown and dull red mosses.

"Ach-h! I'm glad I'm alive to-night!" she had said, gritting her teeth in her Dutch fashion.

But some new demon had possession of her brain now: she stood working with her shawl uncertainly, a trifle pale, watching me. She came to me at last, and stood balancing herself first on her heels and then her toes, biting her lip as if doubtful how to begin.

"I wish we had the baby along!" came with a gruff burst, finally. "God bless its little soul! I went out to see it on Saturday. It would do Uncle Daniel good. He needs something fresh and hearty, bread-and-butter-like, or a baby. You did not notice him this evening particularly, Mrs. Manning, eh?" anxiously.

"No."

"Nothing——Well, no matter. I'm fanciful, maybe. There's an old saying in the family about him, some Doctor's prophecy, and it makes me over-watchful, likely."

She waited for a question. I asked none. There was a dull throb of pain in my heart, but I thrust it down. The girl waited a few moments, debating with herself: I could read the struggle on her face: then she looked up straight into my eyes, her small white teeth showing determined as a steel-trap.

"It's quiet here, Mrs. Manning, and will be for a bit, and there's a story I'd like to tell you. It would do me good, if it were off my mind. Perhaps you, too," with a sharp glance.

"Go on."

She put her hand into her pocket and pulled out a broken morocco case.

"Look here. This tells the whole of the story, almost,"—holding it where the light from the cabin-window fell on it.

It was the daguerreotype of a woman: one of those faces that grow out of a torpid, cunning, sensual life; apparently marked, too, by some strange disease, the skin white, and hanging loose from the flesh. I pushed it away. Jacqueline polished it with her palm.

"She was an opium-eater, you see? The eyes have that rigid staring, like Death looking into life. You pushed it from you, Mrs. Manning?"—shutting it. "Yet I know a man who cherished that living face tenderly in his bosom for fifteen long years, and never opened his lips to say to God once that it was hard to bear: faugh!" and she flung the case into the water. "I only kept it to show you. She, the foul vampire, sucked his youth away. I think it was but the husk of life that was left him when she died;—and we are making that mean and poor enough,"—in a lower voice. "Yet that man"—more firmly—"has a stronger brain and fresher heart than you or I are fit to comprehend, Mrs. Manning. One would think God meant that the last of his life, after that gone, should be a warm Indian-summer day, opening broad and happily into the life He is keeping for him,—would you not?"

"Who is the man?"—my lips growing cold.

"Your husband."[Pg 12]

"I thought so. You did well to tell me that story."

She looked from me, her color coming and going.

"It was hard to do it. You are an older woman than I. But I thought it was needed."

I looked up at the hard-set, chubby little face, beyond at the far yellow night-line of sea, listened to the low choke, choke, of the water in the wheels.

"I wish you would leave me. Let me be alone awhile."

She went to the other end of the deck, where she could keep me in sight. It was so dull, that throb of the water, playing some old tune that would not vary! The sea stretched out in such blank, featureless reaches!

To nestle down into this man's heart and life! To make his last years that warm Indian-summer day! I could do it! I! What utter rest there were in that!

Yet was this power within me to rot and waste? My nature, all the habit and teaching of the years gone, dragged me back, held up my Self before me, bade me look at that. A whiff of tobacco-scented breathing made me look up. M. Vaux was leaning on the deck-railing, his legs crossed, surveying me critically through his half-shut eyes.

"Well, 'm, glad of the chance t' tell you. Henz and Doctor Howe thought so well of that little thing of yours that we've put it in rehearsal,—bring it out Monday week. 'N' 've concluded you can try the part of Marian in it. Not much in that,—one aria you can make something of, but begin easy, hey?"

"I have concluded to give up that scheme, Monsieur."

"Tut! tut! No such thing. Why, you've a master-talent,—that is, with cultivation, cultivation. A fine gift, Madam. Belongs to the public. Why," tapping his yellow teeth with his cane-head, "it's shutting up a bird in a cage, to smother a voice like yours. Must have training,—yes, yes, 'll see to that; 'n' there are tricks and bits of stage-effect; but you'll catch 'em,—soon enough. There's other little matters," with a furtive glance at my square shoulders and bony figure, "necessary to success. But you'll understand."

I saw how anxious the man was that I should accede to the proposal. I had not overrated my genius, then?

"If the thing's to be done, let it be done quickly. I'm going to run back to town to-morrow night, and you'd best go with me, and go in rehearsal at once. You can break it to your people to-morrow. I'll meet you in the boat,—that is," with an unwilling hesitation, "if you decide to go."

Jacky approached us.

"I will let you know," I said; and as he walked away, the water began its dull throb, throb, again, that lasted all night long.

All night long! Other people may approach the crisis of their fate with senses and faculties all on guard and alert; but with me, although I knew the next day would witness my choice for life, I believe that heavy thud of the water was the most real thought, trying my brain beyond endurance. I tried to reason coolly in the night about M. Vaux and his scheme: both vulgar, degrading in outside appearance,—I felt that, to the quick, keenly enough; but inside lay a career, utterance for myself,—and I had been dumb and choking so long!

A beam of light from the cabin-chandelier struck just then sharply across Doctor Manning's face, where he lay asleep in his berth. There was an unusual look in it, as Jacky had said, now that I looked closely: a blueness about the mouth, and a contraction of the nostrils. Was it a hint of any secret disease, that she had looked so terrified, and even the boys had kept such a sidelong scrutiny over him all day? I sat up. If I could go to him, put my hands about his head, cling to him, let my young strength and life ooze into his to atone for all he had lost in those old days! There was passion and power of love under my stiff-muscled fingers and hard calculating[Pg 13] brain, such as these people with their hot blood knew nothing of. It was passion, a weak fever of the flesh. I drew the sheet over me, and lay down again.

The morning was stiflingly hot. I remember the crowd of porters, drays, etc., jostling on the wharf: the narrow street: Monsieur passing me, as we turned into it, and muttering, "By six this afternoon I must know your decision": Robert's grave, inquiring face, when he first met his father, and saw his changed look. The rooms he had taken for us were but partially furnished, carpetless, the sun staring in through dirty windows, blue and yellow paper on the walls. He went out with Dr. Manning for a walk; the boys scattered off noisily to the sea-side. I went to work making a sort of lounge for Teddy to sleep on, out of some blocks of wood and staves of an old barrel, and so passed the time until noon. Then I sat down to mend the weekly heap of boys' socks, half-washed and leather-stained. Out of the window where I sat I looked down into the muddy back-yard of the boarding-house, where an Irishwoman was washing and gossiping with the cook cleaning fish over the ash-heap. This was what Life held for me now, was it? When the door was opened, a strong whiff of dinner filled the room. Two o'clock came.

"I will not go down to dinner," I said to Jacqueline, when the cracked bell rang. "I will go out and find Doctor Manning on the cliffs. I may have something to say to him."

But when she was gone, I darned on at the unclean socks. Somehow the future faced me in my work and surroundings. But I did not think of it as a whole. The actual dignity and beauty of life, God's truth itself, may have grown dim to me, behind a faint body and tired fingers; but let the hard-worked woman who is without that sin throw the first stone at me. I got up at last, folded the stockings, and put them away; then pinned on my bonnet and shawl. Teddy was sitting on the stairs, half asleep. I stopped to kiss him.

"You'll be back soon, mother?"—hugging me close about the neck.

"Good bye, Bud! Bring your father his pipe to-night, as he likes you to do,—and every night."

I strained him close to my breast again; he had a warm, honest little heart of his own; he would be such a man as his father. I gasped, set him down: I dared not kiss him after I thought of that: and went out of the hall, stumbling over the boarders' hats and greasy oil-cloth. Without, the air had that yellow stirless calm peculiar to Newport, which gives to the sea and landscape the effect of those French pictures glassed in tinted crystal. There were but few passengers on the street. I wondered if any of them held his fate in his hand as I did mine that day. Before I reached the cliffs the afternoon was passing away rapidly; the heated pavements under my feet growing cooler, and barred with long gray shadows; a sea-breeze blowing tattered sand-colored clouds inland; the bell of the steamer rang out sharply down at the quiet little wharf. In half an hour she would sail. M. Vaux was on board, awaiting me. I had but little time to spare.

I turned and crept slowly along the road to where the grassy street opened on the cliffs, and sat down on the brown rocks. I could see my husband on the sands with Robert, pacing to and fro; the scent of their cigars almost reached me where I sat. I must see him once more. The bell of the boat rang again; but I sat still, breaking off bits of the salt crust from the rock, hardly looking up to see if her steam was up. I was going. I knew she would not sail until I was on board. And I must see him again; he would call me Hetty, maybe: that would be something to remember. It was very quiet. The bare, ghastly cliffs formed a sort of crescent, on which I sat; far below, the sea rolled in, over the white sand, in heavy ashen sweeps: in one horn of the crescent the quaint old town nestled, its smoky breath[Pg 14] sleepily giving good-night to the clear pink air; in the other stood the sullen fort, the flag flapping sharply against the sky. The picture cut itself vividly on my brain. The two black figures came slowly towards me, across the sands, seeing me at last. I would not tell him I was going: I could write from New York: I thought, my courage giving way. What a hard, just face Robert Manning had! What money I made should go to the support of my child: Robert should not think me derelict in every duty. Then I tried to get up to meet them, but leaned back more heavily on the rocks, twisting my fingers in a tuft of salt hay that grew there.

I heard Robert say something about "jaded" and "overworked," as he looked at me, throwing away his cigar; his father answered in a whisper, which made the young man's face soften, and when they came near, he called me "mother," for the first time. Into the face of the man beside him I did not look: I thought I never could look again. There was a small rip in the sleeve of his great-coat: I remember I saw it, and wondered feebly if Jacky would attend to it,—if my child, when she was a woman, would be careful and tender with her father. Meantime my husband was talking in his cheerfullest, heartiest voice.

"Coming here makes me feel as if the old boy-time had come back, Hetty. Rob and I have been planning out our new life, and the sea and the fresh air and the very houses seemed to join in the talk, and help me on as they used to do then. I'll begin all new: just as then. Only now"——

He put his hand on my shawl with a motion that had infinite meaning and affection in it. The little steamer at the wharf swayed and rocked. Her freight was nearly all on deck: I had but a few moments more,—that is, if I meant to be free.

"We are going down to the hotel for a few minutes,—business, Hetty," he said. "Will you wait for us here? or are you afraid to be alone?

"No, I'm not afraid to be alone. It is better for me."

"Good bye, then. Come, Rob."

I did not say good-bye. Even then, I think I did not know what I had resolved. I thrust my fingers deeper into the wet tuft of grass, heard the long dash of the breakers on the beach, looked at the square black figure of Robert Manning as it went slowly up the sandy road into the street. At the other, taller and more bent, beside it, I did not once look. I wiped the clammy moisture off my face and throat.

"It's the woman's flesh of me," I said. "There is better stuff in me than that. I will go now, and fulfil my calling."

On the wharf, as I went creeping along, I met Monsieur. He offered me his fat little arm, with smiles and congratulations, and handed me hurriedly over the plank on to the deck. In a moment the steamer was puffing out of harbor.

I was to play Marian in my own opera. God had given me a power of head-work, skill for a certain mission, and I was going to perform it. The vast, vague substance on which I was to act was brought before me to-night, palpable,—the world, posterity, time; how did I call it? But, somehow, it was not what I had dreamed of since my babyhood up yonder in Concord. Nothing was vast or vague. I was looking into a little glass in a black-painted frame, and saw the same Mrs. Manning, with the same high cheekbones, the yellow mole on the upper lip, the sorrowful brown eyes: dressed in tulle now, though, the angular arms and shoulders bare, and coated with chalk, a pat of rouge laid on each cheek: under the tulle-body the same old half-sickness; the same throbbing back-tooth threatening to ache. The room was small, triangular: a striped, reddish cotton carpet on the floor, a door with a brass handle, my bandbox open on a chair, a basin with soapy water, soiled towels, two dripping tallow-candles: in short, a dressing-room in a theatre. Outside, wheels, pulleys, pasteboard castles, trees, chairs,[Pg 15] more bony women, more chalk, more tulle. Monsieur in a greasy green dressing-gown odorous of tobacco, swearing at a boy with blear eyes,—a scene-shifter. The orchestra tuning beyond the foot-lights: how vilely the first violin slurred over that second passage! "Life's Prophecy," I called it; and that "Vision of Heaven," the trombonist came in always false on the bass, because, as Monsieur said, he had always two brandy-slings too much. Beyond was "the world," passive, to be acted upon; the parquet,—ranged seats of young men with the flash-stamp on them from their thick noses to the broad-checked trousers; the dress-circle,—young girls with their eyes and brains full-facing their attendant sweethearts, and a side-giggle for the stage; crude faces in the gallery, tamed faces lower down; gray and red and black and tow-colored heads full of myriad teeming thoughts of business, work, pleasure, outside of this: treble and tenor notes wandering through them, dying almost ere born; touching what soul behind the dress and brain-work? and touching it how? Ah, well! "I am going to fulfil my mission." I said that, again and again, as I stood waiting. "Now. This is it. I take it up." But my blood would not be made to thrill.

"This wart must be covered," said a walking-lady in red paper-muslin, touching the mole on my lip with Meen Fun. M. Vaux tapped at the door,—a sly, oily smile on his mouth.

"We are honored to-night. Be prepared, my dear Madam, for surprises in your audience. Your husband is in the house,—and his son, Robert Manning."

I put up my hands in the vain effort to cover the bare neck and shoulders,—then, going back into the dressing-room, sat down, without a word. I remember how the two tallow-candles flared and sputtered, as I sat staring at them; how on the other side of the brass-handled door the play went on, the pulleys creaked, and the trombones grated, and the other women in tulle and chalk capered and sang, and that at last the stuffy voice of the call-boy outside cried, "Marian, on," and it was my time to fulfil my mission. I remember how broad a gap the green floor of the stage made to the shining tin foot-lights; how the thousand brassy, mocking eyes were centred on the lean figure that moved forward; how I heard a weak quaver going up, and knew it to be my own voice: I remember nothing more until the scene was ended: the test and last scene of the opera it had been: and as the curtain fell, it was stopped by a faint, dismal hiss that grew slowly louder and more venomous, was mingled with laughs and jeers from the gallery, and the play was damned. I stood with my white gauze and bony body and rouge behind a pasteboard flower-vase, and looked out at the laughing mob of faces. This was the world; I had done my best head-work for it, and even these plebeian brains had found it unfit for use, and tossed it aside. I waited there a moment, and then passing Monsieur, whose puffy face was purple with disappointment and rage, went into the dressing-room.

"What wonder?" I heard him demand in French. "It was so coarse a theft! But I hoped the catch-dresses would pass it off."

I wrapped a flannel cloak over my airy robes, and went out, down the crooked back-stairs into the street. I had no money; if I went back to the hotel where I had been stopping, it would be as a beggar.

I waited outside of the theatre by an old woman's candy-stand for the crowd to hustle past, holding myself up by her chair-back. She was nodding, for it was past midnight, but opened her red eyes to lift a little child on her knees who had been asleep at her feet.

"Come, Puss, the play's out, it's time for you an' Granny to be snug at home."

I laughed. Why, there was not one of these women or men crowding by, the very black beggar holding your horse, who had not a home, a child to touch, to love them,—not one. And I—I had my Self. I had developed that.

I pulled the cloak closer about me and[Pg 16] went down the pavement. The street was thronged with street-cars stopping for the play-goers, hacks, and omnibuses; the gas flamed in red and green letters over the house-fronts; the crowd laughed and swayed and hummed snatches of songs, as they went by. I saw one or two husbands drawing the wrappings tighter about their wives' throats, for the air was sharp. My husband had seen my shoulders to-night,—so had they all, covered with chalk. There were children, too, cuddling close to their mothers' sides in the carriages. I wondered if my child would ever know it had a mother. So I went slowly down the street. I never saw the sky so dark and steely a blue as it was that night: if there had been one star in it, I think it would have looked softer, more pitying, somehow, when I looked up. Knowing all that I had done, I yet cannot but feel a pity for the wretch I was that night. If the home I had desolated, the man and child I had abandoned, had chosen their revenge, they could not have asked that the woman's flesh and soul should rise in me with a hunger so mad as this.

At the corner of the street, a group from the crowd had stopped at the door of a drug-shop; they were anxious, curious, whispering back to those behind them. Some woman fainting, perhaps, or some one ill. I could not pass the lock of carriages at the crossing, and stopped, looking into the green light of the window-bottles. In a moment I caught my own name, "Manning," from a policeman who came out, and a word or two added. The crowd drew back with a sudden breath of horror; but I passed them, and went in. It was a large shop: the lustres, marble soda-fountains, and glittering shelves of bottles dazzled me at first, but I saw presently two or three men, from whom the crowd had shrunk away, standing at the far end of the shop. Something lay on the counter among them,—a large, black figure, the arm hanging down, the feet crossed. It did not move. I do not know how long I stood there, it might be hours, or minutes, and it did not move. But I knew, the first moment I looked at it, that it never would move again. They worked with him, the three men, not speaking a word. The waistcoat and shirt were open; there was a single drop of blood on the neck, where they had tried to open a vein. After a while the physician drew back, and put his hand gently on the shoulder of the shorter, stouter of the other two men.

"My friend," he said, compassionately.

Robert Manning did not seem to hear him. He had knelt on the floor and hid his face in the hand that hung down still and cold. The druggist, a pale, little person, drew the doctor aside.

"What is it, now? Apoplexy?" his face full of pity.

"No. Brought on by nervous excitement,—heart, you know. Threatened a long time, his son says. His wife, the woman who"——

The policeman had been eying my dress under the cloak for some time.

"Hi! You'd best move on," he whispered. "This a'n't no place for the likes of you."

I stood still a moment looking at the brawny black figure lying on the counter. The old days of Tinder and the paddock,—I don't know why I thought of them. It did not move: it never would move again. Dead. I had murdered him. I! I got my fingers in my oily hair, and pulled at it. "Hetty, Hetty Manning," I said, "good bye! Good bye, Daniel!" I remember hearing myself laugh as I left the shop-door; then I went down the street.

When I was far down the Bowery, an old thought came feebly up in my brain. It was how the water had choked, choked, all that night long in the wheel of the boat. When I thought of that, I waited to think. Then I turned and went to the bay, beyond Castle Garden.

The rain, drip, dripping on a cottage-roof: on branches, too, near at hand, that rustled and struck now and then against the little window-shutters, in a fashion just dreary enough to make one nestle closer into the warm bed, and peep[Pg 17] out into the shadowy chamber, with the cozy little fire burning hotly in the grate. Patter, patter: gurgling down the spouts: slacking for a minute, threatening to stop and let you sleep in a usual, soundless, vulgar way, as on other nights: then at it again, drip, drip, more monotonous, cheerfuller in its dreariness than ever. Thunder, too: growling off in the hills, where the night and rain found no snug little bed-room to make brighter by their besieging: greenish-white jets of lightning in the cracks of the shutters, making the night-lamp on the toilet-table and the fire suddenly go out and kindle up fiercely again.

This for a long time: hours or not, why should one try to know? A little bed, with crimson curtains, cool white pillows: a soft bed, where the aching limbs rested afresh with every turn. After a while, a comfortable, dumpling little figure in a loose wrapper, popping out of some great chair's depths by the fire and stirring some posset on the hearth: smelling at a medicine-bottle: coming to the bed-side, putting a fat hand on one's forehead: a start, a nervous kiss, a shaky little laugh or two, as she fumbles about, saying, "Hush-h!" and a sudden disappearing behind the curtains. A grave, pale face looking steadily down, as if afraid to believe, until the dear eyes fill with tears, and the head, with its old wig, is dropped, and I and God only know what his soul is saying.

"My husband!"

"Hetty!"

"Is it you?—Daniel?"

He lifted me in his arms farther up on the pillow, smoothing the blankets about me, trying to speak, but only choking, in a ridiculous fashion.

"And the opera, and the drug-shop, and"——

I held my hand to my head.

"The truth is," said Jacky, bobbing out from behind the curtains, her eyes suspiciously red and shiny, "I'm afraid you've had some bad dreams, dear. Just take a teaspoonful of this, that's a good soul! You've been ill, you see. Brain-fever, and what not. The very day we came to Newport. Uncle Daniel and Robert found you on the cliff."

"When we came from the hotel, you remember?" still pulling the blanket up, his lip unsteady.

"You'll choke her; what a nurse you are, to be sure, Uncle Dan! And the woman's feet as bare"——

"There, there, Jacky! I know,"—submissively, twitching at my nightcap, and then gathering my head into his arms until I could hear how his heart throbbed under the strong chest. "My wife! Hetty! Hetty!" he whispered.

I knew he was thanking God for giving me to him again. I dared not think of God, or him: God, that had given me another chance.

I lay there until morning, weak and limp, on his arm, touching it now and then to be sure it was alive, an actual flesh-and-blood arm,—that I was not a murderer. Weak as any baby: and it seemed to me—it comes to me yet as a great truth—that God had let me be born again: that He, who gave a new life to the thief in his last foul breath, had given me, too, another chance to try again. Jacky, who was the most arbitrary of nurses, coiled herself up on the foot of the bed, and kept her unwinking eyes sharp on us to enforce silence. Never were eyes more healthful and friendly, I thought feebly. But I tried all the time to press my poor head in closer to my husband's breast: I was barely free from that vacuum of death and crime, and in there were the strength and life that were to save me; I knew that. God, who had brought me to this, alone knew how I received it: whether it was a true wife that lay on Daniel Manning's bosom that night; how I loathed the self I had worshipped so long; how the misused, diseased body and soul were alive with love for him, craved a week's, a day's life to give themselves utterly to him, to creep closer to him and the Father that he knew so simply and so well. I heard him once in the night, when he thought I was asleep, say to himself[Pg 18] something of the wife who had been restored to him, who "was dead and is alive again, was lost and is found." But how true those words were he can never know.

I fell asleep towards morning, and when I woke, it was with a clear head and stronger eye to comprehend my new chance in life. The room had a pure, fresh, daylight look, snug and tidy; a clear fire crackled on the clean hearth; Jacky herself had her most invigorating of morning faces, going off at the least hint of a joke into redness and smiles. It rained still, but the curtains were drawn back, and I could see through the gray wet what a pleasant slope of meadow there was outside, clumped over with horse-chestnuts and sycamores, down to a narrow creek. The water was fogged over now with drifting mist, but beyond I caught glimpses of low wooded hills, and far to the left the pale flush of the sea running in on the sand. My husband was watching me eagerly as I looked out.

"I do not know where I am, Daniel."

"No, of course you don't,"—rubbing his forehead, as he always did when he was especially pleased. "There's so much to tell you, Hetty dear! We're beginning all new again, you see."

"You'll not tell a word, until she's had her breakfast," said Jacky, dogmatically, coming with her white basin of cool water.

Oh, the remembrance of that plunge of cold on the hot skin, of the towel's smelling of lavender, of the hard-brushed hair, of the dainty little tray, with its smoking cup of fragrant, amber tea, and delicatest slice of crisp toast! Truly, the woman's flesh of me, having been triumphant so long, goes back with infinite relish to that first meal, and the two bright faces bent over me. And then came Teddy, slying to the pillow-side, watching my pale face and thin hands with an awe-struck gaze, and carrying off the tea and toast to finish by the hearth.

"You can't see much for the rain, mother," anxiously. "Not the orchard, nor the stable,—but there is a stable, and hay, and eggs every morning, only the gray hen's trying to set, if you'll believe it. And old Mary's in the kitchen, and we've got even Tinder and our old peacock from the Hudson."

"Eat your toast now, Captain," said his father, putting his arm about me again.

"Yes, Hetty, it's a bit of a farm,—ten or fifteen acres. Our cozery: yours and mine, dear. It's Rob's surprise,"—with the awkward laugh a man gives, when, if he were a woman, the tears would come.

"Rob?"

"Yes. He had it ready. I knew it before we left New York, but we wanted to surprise you. The boys all put in a little. They're good boys. I've hardly deserved it of them,"—pulling at the quilt-fringe. "I've been a glum, unsociable old dog. I might have made their lives cheerfuller. They're going West: Bill and John to Chicago, and Jem to St. Louis: just waiting for you to be better."

"I am sorry."

I was sorry. The thought of their earnest, honest, downright faces came to me now with a new meaning, somehow: I could enter into their life now: it was an eager affection I was ready to give them, that they could not understand: I had wakened up, so thirsty for love, and to love.

"Yes, Rob did it,"—lingering on the name tenderly. "It's a snug home for us: we'll have to rough it outside a little, but we're not old yet, Hetty, eh?" turning up my face. "I have my old school in town again. We have everything we want now, to begin afresh."

I did not answer; nor, through the day, when Jacky and the boys, one after another, would say anxiously, as one does to a sick person, "Is there anything you need, mother?" did I utter a wish. I dared not: I knew all that I had done: and if God never gave me that gift again, I never should ask for it.[Pg 19] But I saw them watching me more uneasily, and towards evening caught part of Jacky's talk with Doctor Manning.

"I tell you I will. I'll risk the fever," impatiently. "It's that she wants. I can see it in her eyes. Heaven save you, Uncle Dan, you're not a woman!"

And in a moment she brought my baby and laid it in my breast. It was only when its little hand touched me that I surely knew God had forgiven me.

It ceased raining in the evening: the clouds cleared off, red and heavy. Rob had come up from town, and took his father's place beside me, but he and Jacky brought their chairs close, so we had a quiet evening all together. Their way of talking, of politics or religion or even news, was so healthy and alive, warm-blooded! And I entered into it with so keen a relish! It was such an earnest, heartsome world I had come into, out of myself! Once, when Jacqueline was giving me a drink, she said,—

"I wish you'd tell us what you dreamed in all these days, dear."

Robert glanced at me keenly.

"No, Jacky," he said, his face flushing.

I looked him full in the eyes: from that moment I had a curious reliance and trust in his shrewd, just, kindly nature, and in his religion, a something below that. If I were dying, I should be glad if Robert Manning would pray for me. I should think his prayers would be heard.

"I will not forget what I dreamed, Robert," I said.

"No, mother. I know."

After that, awhile, I was talking to him of the home he had prepared for his father and me.

"I wanted you just to start anew, with Teddy and the baby, here," he said, lightly.

"And Jacky," I added, looking up at the bright, chubby face.

It grew suddenly crimson, then colorless, then the tears came. There was a strange silence.

"Rob," she whispered, hiding her head sheepishly, "Rob says no."

"Yes, Rob says no," putting his hand on her crisp curls. "He wants you. And mother, here, will tell you a woman has no better work in life than the one she has taken up: to make herself a visible Providence to her husband and child."

I kissed Jacky again and again, but I said nothing. He went away just after that. When he shook hands, I held up the baby to be kissed. He played with it a minute, and then put it down.

"God bless the baby," he said, "and its mother," more earnestly.

Then he and Jacky went out and left me alone with my husband and my child.

So sings a certain venerable pitcher its untiring song. A brave pitcher it was in its day. A well-ordered farm lies along its swelling sides. A purple man merrily drives his purple team afield. Gold and purple milkmaids are milking purple and golden cows. Young boys bind the ripened sheaves, or bear mugs of foaming cider to the busy hay-makers, with artistic defiance of chronology. There are ploughs and harrows, hoes and spades, beehives and poultry-houses, all in the best repair, and all resplendent in purple and gold. Alas! Ilium fuit. The gold is become dim, the purple is dingy, the lucent whiteness has gone gray; a very large, brown, zigzag fissure has rent its volcanic path through the happy home, dividing the fair garden, cutting the plough in two, narrowly escaping the ploughman; and, indeed, the whole structure is saved from violent disruption only by the unrelaxing clasp of a string of blue yarn. Thus passes away the glory of the world!

Is it not too often typical of the glory of our rural dreams? To live in the country; to lie on green lawns, or under bowers of roses and honeysuckle; to watch the procession of the flowers, and bind upon our brows the sweetest and the fairest; to take largess of all the fruits in their season; to be entirely independent of the world, dead to its din, alive only to its beauty; to feed upon butter and honey, and feast upon strawberries and cream, all found within your own garden-wall; to be wakened by the lark, and lulled asleep by the cricket; to hear the tinkling of the cow-bell as you walk, and to smell the new-mown hay: surely we have found Arcadia at last. Cast away day-book and ledger, green bag and yardstick; let us go straightway into the country and buy a farm.