Project Gutenberg's The House of Fulfilment, by George Madden Martin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The House of Fulfilment Author: George Madden Martin Release Date: March 28, 2010 [EBook #31806] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HOUSE OF FULFILMENT *** Produced by David Garcia, Sam W. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Kentuckiana Digital Library)

By GEORGE MADDEN MARTIN

AUTHOR OF EMMY LOU

NEW YORK

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

MCMIV

Copyright, 1904, by

McCLURE, PHILLIPS & CO.

Published, September, 1904

Second Impression

Copyright, 1904, by The S. S. McClure Co.

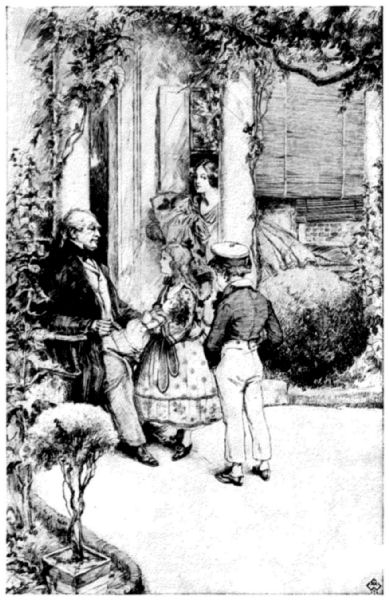

“WHAT IS YOUR NAME, DEAR?”

To A. R. M.

| PAGE | |

| PART ONE | 1 |

| CHAPTER ONE | 3 |

| CHAPTER TWO | 18 |

| CHAPTER THREE | 27 |

| CHAPTER FOUR | 35 |

| CHAPTER FIVE | 53 |

| CHAPTER SIX | 65 |

| CHAPTER SEVEN | 78 |

| PART TWO | 85 |

| CHAPTER ONE | 87 |

| CHAPTER TWO | 106 |

| CHAPTER THREE | 115 |

| CHAPTER FOUR | 147 |

| CHAPTER FIVE | 163 |

| CHAPTER SIX | 173 |

| CHAPTER SEVEN | 187 |

| CHAPTER EIGHT | 207 |

| PART THREE | 227 |

| CHAPTER ONE | 229 |

| CHAPTER TWO | 244 |

| CHAPTER THREE | 261 |

| CHAPTER FOUR | 278 |

| CHAPTER FIVE | 286 |

| CHAPTER SIX | 297 |

| CHAPTER SEVEN | 304 |

| CHAPTER EIGHT | 321 |

| CHAPTER NINE | 328 |

| CHAPTER TEN | 337 |

| CHAPTER ELEVEN | 341 |

| CHAPTER TWELVE | 350 |

| CHAPTER THIRTEEN | 354 |

| CHAPTER FOURTEEN | 368 |

Harriet Blair was seventeen when she went with her father and mother and her brother Austen to New Orleans, to the marriage of an older brother, Alexander, the father’s business representative at that place. It was characteristic of the Blairs that they declined the hospitality of the bride’s family, and from the hotel attended, punctiliously and formally, the occasions for which they had come. It takes ease to accept hospitality.

Alexander Blair, the father, banker and capitalist, of Vermont stock, now the richest man in Louisville, was of a stern ruggedness [Pg 4] unsoftened by a long and successful career in the South, while his wife, the daughter of a Scotch schoolmaster settled in Pennsylvania, was the possessor of a thrifty closeness and strong, practical sense.

Alexander, their oldest son, a man of thirty, to whose wedding they had come, was what was natural to expect, a literal, shrewd man, with a strong sense of duty as he saw it. His long, clean-shaven upper lip, above a beard, looked slightly grim, and his straight-gazing, blue-grey eyes were stern.

The second son, Austen, was clean-featured, handsome and blond, but he was also, by report, the shrewd and promising son of his father, even as his brother was reported before him.

Harriet, the daughter, was a silent, cold-looking girl, who wrapped herself in reserve as a cover for self-consciousness but, observing [Pg 5] closely, thought to her own conclusions. She had a disillusioning way of baring facts in these communings, which showed life to her very honestly but without romance or glamour.

At the wedding, sitting in her white dress by her father and mother in the flower-bedecked parlours of the Randolphs, Harriet looked at her brother, standing by the girl of seventeen whom he had just married, and saw things much as they were. In Molly, the bride of an hour, with her child’s face and red-brown hair and shadowy lashes, she saw a descendant of pleasure-loving, ease-taking Southerners. Molly’s father, from what Austen had said, was the dispenser of a lavish and improvident hospitality and a genial dweller on the edge of bankruptcy, while the mother, a belle of the ’40’s, some one had told the Blairs, seemed just the [Pg 6] woman to marry her only child to a man opposed to her people in creed, politics and habits—which in 1860 meant something—but son of one of the richest men in the South.

Harriet ate her supper close by her father and mother. She did not know how to mix with these gay, incidental Southerners, and sitting there, went on with her communings. She could explain it on the Randolph side, but why Alexander was marrying Molly she could not understand. Shy and self-conscious, she knew vaguely of a thing called love. She had met it in her reading rather than seen its acting forces anywhere about her. To be sure, her brother Austen had been engaged to a Miss Ransome of Woodford County, a fashionable Kentucky beauty. The Blairs were a narrowly religious people. Harriet, a school-girl then, had stood at the [Pg 7] window of the stately new stone house in Louisville which the Blairs called home, and, watching the fashionable world flow in and out of the high old brick cottage across the street, where Miss Ransome spent much time with a great-aunt, had wondered.

But love had not proved such a factor after all. Austen’s engagement had been broken.

Harriet went back to Kentucky with the question of Alexander and Molly still open.

A year later her father went South again. War was loudly threatening, and he had large interests in Louisiana and Mississippi. There was a certain sympathy and understanding between the stern, silent man and his daughter, and he suggested that she go with him and see the child newly born to Alexander and Molly.

But, reaching New Orleans to find his son [Pg 8] gone to Mobile, concerning these same interests, Mr. Blair decided to join him, and Molly being about to leave for her father’s plantation with the baby and nurse, that she might the more rapidly convalesce, it was decided that Harriet accompany her.

The two weeks at Cannes Brulée were strange to the girl, thus introduced to a Southern house overflowing with guests and servants, and she moved amid the idling and irresponsibility, the laughter and persiflage, with a sense of being outside of it all, and the fault, try as she would, her own.

This feeling was strongest that Sunday afternoon when the gaiety and badinage seemed to centre about a new arrival, a handsome, silver-aureoled Catholic priest, confessor to half the parish. Genial, polished, and affable, his very charm seemed to the Calvinistic-bred Harriet to invest him [Pg 9] the more with the seductions of Romanism, as she had been taught to regard them.

There were music, cards, a huge bowl frosted with the icy beverage within, and to the stunned young Puritan the genial little priest in the midst seemed smiling a bacchanalian benediction over all.

Suddenly, above chatter and music Molly’s voice arose, gay but insistent, Molly there in the big chair, pale and big-eyed, her strength so slow to return, herself a child in her little muslin dress.

“Baby is four weeks old,” Molly was declaring, “and here is Father Bonot from service at Cannes Brulée and so with his vestments. I’m here and Harriet’s here, and mamma’s here, and everybody else is a cousin or something. I’m sure I don’t know when I can get to church. P’tite shall be baptized here, now.”

[Pg 10] And before the slower comprehension of the dazed Harriet had grasped the meaning of the ensuing preparations—the draping of the pier-table, the lighting of waxen candles—a sudden silence had fallen; the gay abandon of these mercurial Southerners had given place to reverent awe, even to tears, as the new-born representative of the Puritan Blairs was brought in, in robes like cascades of lace, while of all that followed, the one thing seeming to reach the comprehension of Harriet was the chanting monotone of Father Bonot saying above the child, “Mary Alexina—”

Later Molly and Harriet went back to New Orleans, to find Alexander there but his father gone up to Vicksburg. Molly was to keep Harriet with her until his return.

Only the girl knew what it meant to find herself near her brother. It was as if here [Pg 11] was something sane, rational, stable, by which to re-establish poise and standards. Harriet would have trembled to oppose her brother, so that to see Molly and Alexander together was a revelation. His sternness and his displeasure alike broke as a wave upon Molly, and as a wave receded, leaving her, as a wave would leave the sand, pretty and sparkling and smiling. Other things were revelations to Harriet, too.

Going down to breakfast one morning, she found her brother clean-shaven, immaculate, monosyllabic, awaiting the overdue meal. The French windows were open to the scent of myriads of roses outside, and also to the morning sun, far too high. The negro servants were hurrying to and fro, Molly nowhere visible.

Later, as the dishes were being uncovered, she appeared, her unstockinged little feet [Pg 12] thrust into pretty French slippers, and her cambric nightgown by no means concealed by a negligée, all lace and ribbons, hastily caught together. Yet she was pretty, pretty like a lovely and naughty child.

Nor did the embarrassment of Harriet, the presence of the servants, or her husband’s cold preoccupation with his breakfast disturb Molly, who trailed along with apparent unconcern until, reaching his elbow, she threw a wicked glance at Harriet, then kissed him on that spot on his head which, but for a few carefully disposed strands, must have been termed bald.

At the thing, absurd as it was, there swept over Harriet the hot shrinking of one made conscious of sex for the first time. With throbbing at throat and ears, she gazed into her plate, her feeling, oddly enough, centring in keen revulsion against her brother.

[Pg 13] But Molly was dragging a chair to his elbow. “What’s the fricassee made of, Alexander?”

Her husband vouching her no reply, she slipped an arm about his neck, and, leaning over, drew his fork to her mouth and tasted the morsel thereon.

Then she turned her head sideways to regard him. “Don’t frown it back, Alec, the smile I mean. I adore you when you don’t want to and have to let it come. Acknowledge now, this is the way to breakfast.”

And Harriet, who had been led to regard playfulness as little less than vice, was conscious of Molly trying to force a ripe fig between Alexander’s lips, repressed, thin lips upon which softening sat as if afraid of itself and her.

“You see,” Molly was explaining, “I couldn’t get down sooner. P’tite was making [Pg 14] the most absurd catches at her mosquito bar, and Celeste refusing to laugh at her. You haven’t finished your breakfast? Why must you always hurry off? No”—her hand against his mouth, he, risen now, she on a knee in her chair, clinging to him—“don’t tell me any more about Sumter having been fired upon, and your being worried over business. I hate business. What’s anything this moment, if you would only see it, compared with me, and ripe figs dipped in cream?”

And then the triumph of her laugh as, his arms suddenly around her, he grasped her, lifted, enfolded her for a moment, then as fiercely put her from him and went out, leaving Harriet sick, shaken, at this sight of human passion seen for the first time.

The following day Harriet’s father returned and she went home.

[Pg 15] When she next saw her brother it was in Louisville, where he was driven back to his own people by reason of his Northern creed and sympathies. His father-in-law had been among the first to fall in defence of the Confederacy, and with Alexander, now, was his mother-in-law, widowed and dependent, and a wife in this sense changed from child to woman—that she was a fiercely avowed Southerner to the fibre of her.

With his little family he remained in Louisville a year. If his own people wondered at the extravagance of his wife and mother-in-law at a time when incomes were so seriously shrunken, Alexander was too much a Blair for even a Blair to approach the subject.

The child was sent daily to his mother’s—he saw to that—a pretty baby, the little [Pg 16] Mary Alexina, and robed like a young princess; but beyond this he seemed to discourage intimacy between the households. Certainly there was no common ground, the business judgment, large experience, and the integrity of the Blairs being in the constant service of the government, while rumor had it that the home of young Mrs. Alexander Blair was the social rallying place for Southern sympathizers generally.

Suddenly, in the midst of big affairs, Alexander arranged otherwise for the maintenance of his wife’s mother, whom it was his to support for the few remaining years of her life, and went to Europe with Molly and the child. Long after it came to Harriet’s hearing that the frequent presence of a young Confederate officer at his house had led to the step.

It was four years from this time, in 1867, [Pg 17] that Alexander Blair, the senior, died, to be shortly followed by his wife.

Though the son Alexander returned to Louisville of necessity, following these events, he left Molly and the child in Washington with some of her people there. And though his interests became centred in Louisville again, he never brought his family back, but went and came between the two places. In domestic infelicity it is our own people we would hide it from longest. It was two years after, in ’69, that Alexander met his end with the shocking suddenness of accidental death as he was returning East to Molly and the child.

The leisure of a summer evening had fallen with the twilight. Along that street in Louisville wherein stood the Blair house, with its splendid lawn, and its carriage driveway issuing through a tall, iron gate, front doors were opening and family groups gathering. The yards wore the fresh green of June. A homecoming crumple-horn ambled by, her bag swinging heavily. In the South, in 1870, cities were villages overgrown.

In the parlour of her home Harriet Blair sat, awaiting the arrival of her brother Austen from Washington, where he had gone to bring back their dead brother’s child.

[Pg 19] Harriet, at twenty-six, in lustreless mourning, was handsome and, some might have said, cold. Her face was finely chiselled, and framed with light hair waving from its parting in curves regular as the flutings of a shell. There was a poise, a composure about this Harriet, making her unlike the tall, shy girl of nine years before.

As the bell rang she laid down her book and rose, and a second later Austen entered, leading a little girl with a round, short-cropped head. His eyes met his sister’s in greeting, then he loosed the child’s hand. “This is your Aunt Harriet, Alexina,” he said, and stepped across the room to stand before the mantel and watch the two.

Harriet bent and kissed the small cheek. Demonstration, even to this extent, meant much for a Blair. Then she crossed the room. She was more than ordinarily tall [Pg 20] for a woman, with form proportioned to length of limb, and the beauty of her carriage gained by her unconsciousness of it.

Having pulled the bell-cord she came back, smiling, calmly expectant, looking from Austen to the child, who, seated now on the edge of a chair, was regarding her with grave eyes.

“She has a strong look of Alexander,” said Harriet, consideringly, “and a little look of you—and of me. She is a Blair, though I can see her mother, too, about the mouth.”

The child moved under the scrutiny, but her gaze, returning the study, did not falter.

Harriet laughed; was it at this imperturbability? “I think,” she decided, “we may consider her a Blair.” Then to the white maid-servant entering: “You may order supper, Nelly, for Mr. Blair and myself. [Pg 21] This is Alexina, and, I should say, tired out. Suppose you give her a warm bath and let her go right to bed—have you her trunk key, Austen?—and I will send a tray up with her supper afterward.”

Then, as Nelly took the key and went out, Harriet addressed her brother. “For, apart from the hygienic advantages of the bath before the supper, I confess”—with faintly discernible amusement—“to a fancy for the ceremony as a form, so to speak, emblematic of a moral washing and a fresh start.” She ended with a raising of her brows as she regarded her brother.

Austen Blair had no use for levity. Mild as this was, he dismissed it curtly. “I would suggest,” he said, “that you avoid personalities; it can but be injudicious for any child to hear itself discussed.”

Again Harriet laughed; she was provokingly [Pg 22] good-humoured. “Coming from her nine years of life beneath Molly’s expansive nature, I don’t think you need fear for what she’ll gather from me.” She took the child’s hand and lifted her from the chair. “Here is Nelly, Alexina; go with her and do what she says. Say good-night to your uncle. Supper, Austen.”

The dining-room being sombre, one might have said it accorded with the master, whose frown had not all cleared away.

Harriet was speaking. “What of Molly? Was there a scene at parting with her voluntarily given-up offspring? For her moods, like her tempers, used to delight in being somewhat inconsistent and mixed.”

“She has in no way changed,” replied Austen. Was it this flat conciseness in all he said that made levity irresistible to Harriet in turn? “My interview with her was [Pg 23] confined to business. That ended, she told me, as an afterthought, apparently, that the coloured woman was going to remain with her, and she supposed Alexina could manage on the train. She also told me that her husband had severed connection with the legation and was going back to Paris. Alexina was not with them at the hotel, but with her uncle, Senator Randolph, from whose house Molly was married.”

“And Molly’s parting with the child—”

“Was a piece with it all, tears and relief, just as you would have expected.”

“And the husband’s, this Mr. Garnier’s, attitude?”

“Was enigmatical; how far he understands the situation I had no means of judging.”

“I’m sorry for the child, though,” said Harriet suddenly, “for if there is anything [Pg 24] of Molly in her, life according to the Blair standard may pall, and,” whimsically, “her mixture of natures be vexed within her.”

Austen took the Blairs seriously, and at any time he disliked the personal or the playful. He spoke coldly. “Having given the child over to you from the moment of arrival, of this initiatory tone you are taking I shall say no more. Duties you assume you do best your own way.”

Harriet arched her brows. “You mean, having found better results followed the withdrawal of your oversight of me as mistress of our house, you are going to let me alone in this?”

“Exactly,” said her brother, “and therefore on the subject, now or hereafter, I shall say no more.” And it was eminently characteristic of him that he never did.

Meanwhile up-stairs the child had gone [Pg 25] through with the bath and the supper like an automaton in Nelly’s hands.

“She said ‘yes’ when I asked her anything,” Nelly reported later to the cook; “or she said ‘no’. And her lips were set that hard she might a’most have been Mr. Austen’s own child.”

And that was all Nelly saw in the little creature she tucked into the huge, square bedstead under the bobinet mosquito bar. But no sooner had Nelly’s footsteps ceased along the hall than the child, as one throwing off an armour of repression, rolled out of the high bed and from under the bar, flinging and disarranging the neat covers with passionate fury, sobbing wildly. A bead of gas lit the room. She pattered across the floor to the opened trunk, and when the little figure, stumbling over its gown, stole back to bed, a heartrendingly battered, plaster-headed [Pg 26] doll was clasped in its arms. And, as the voices of children at play on the sidewalk came up through the open windows, the child, shaken with crying—the more passionate because of long repression—was declaring: “Sally Ann, baby, I couldn’t never have given you up, not even if I was your own truly mother, Sally Ann, I couldn’t, never.”

Down-stairs the evening passed as evenings usually did when Harriet and Austen were alone. There were not even the varyings from parlour to front door that the heat seemed to necessitate for the rest of the neighbourhood. Front porches are sociable things. The Blairs’ was the only house on the street without one.

The evening passed with the brother and sister at opposite sides of the black, marble-topped table in the long parlour, she embroidering on a strip of cambric with nice skill, he quickly and deftly cutting the wrappers and pages of papers and magazines [Pg 28] accumulated in his absence. To undertake just what he could do justice to and keep abreast of it, was the method by which he accomplished more than any two men, in business, in church affairs, in civic duties, for the man took his citizenship seriously. Both brother and sister had been raised to economy of time, yet sometimes she mocked at herself for her many excellencies and sometimes sighed, while he—

At ten o’clock Harriet rolled her work together and said good-night, ascending the crimson-carpeted stairway with the unhurried movement of an Olympian goddess; that is, if an Olympian goddess could have been so genuinely above concern about it.

Her room, a front one on the second floor, had a look of spaciousness and exquisite order. She moved about, adjusting a shade, setting a gas-bracket at some self-imposed [Pg 29] angle of correctness, giving the sheets of the opened bed a touch of adjustment.

It was the price paid for the free exercise of individuality. Already, at twenty-six, ways were becoming habits.

These things arranged, she passed to the adjoining room, from to-night given to Alexina. Turning up the gas, Harriet glanced about at Nelly’s disposition of things, then moved to the bed.

Whatever were the emotions called forth by the relaxed little form, softly and regularly breathing against a battered doll, or by the essentially babyish face with the fine, flaxen hair damp and clinging about the forehead, the Blairs were people to whom restraint was second nature. Whatever Harriet felt showed only in solicitude for the child who had thrown aside all cover. But as she drew the sheet and light blanket up, [Pg 30] her hand touched the smoothness of a bared little limb. It brought embarrassment. She had but once before touched the bareness of another’s body, and that her mother’s, and in death.

Was it shame, this surging of strange hotness through her?

The refuge of a Blair was always action. She stepped to the bay of the room and drew the shutters against the night-wind.

Between the windows stood the bureau. Harriet paused, arrested by a daguerreotype in a velvet case open upon it. The child must have left it there. She sat down and laying the picture on her knee, regarded it, her chin in her palm.

It was the face of the father of the sleeping child, dead less than a year, for whom his sister was wearing this black trailing in folds about her.

[Pg 31] And looking on his face, she recalled another, exquisite in pallor, with shadowy lashes, the face of Molly, who ten months after Alexander’s death had married again; who not only married but gave up her child. Had it been the purpose of Alexander to test her for the child’s sake? She had been given her third and the child the same, with Austen as executor and guardian. In the event of Molly marrying again, she had been given choice. She might relinquish all right in the remaining third and keep the child, or by giving up the child could claim the portion. And the estate was large. In ten months Molly had chosen.

And yet, thinking of these things, Harriet bade herself be just, chief tenet in the Blair creed. Was she so certain Alexander had been altogether unhappy in his marriage? May not compensations arise out of [Pg 32] a man’s own nature if he cares for the woman? For Harriet no longer asked why her brother had married Molly. She knew, knew that the thing called love is stronger than reason, than life—some even claimed, than death. Not that she knew it of herself, this calm, poised Harriet, but, watching, she had seen its miracles.

And out of this, Alexander may have drawn his compensation, for, stronger than the hourly friction of his daily life, stronger than the hurt of outraged conventionality, thrift, and pride, stronger than the jealousy which must have often assailed him, had not love survived in Alexander to the end, love that protected and concealed Molly’s failings from his own people?

Suddenly, over Harriet swept the breath of roses coming into an open breakfast room and she saw a stern-lipped man lift, [Pg 33] enfold a child-woman to him for a moment, and as fiercely put her from him and go out.

Harriet, breathing quickly, put her brother’s picture back, and going to the bed, lifted the bar and drew the sheet again over the child. Then she stood looking down. What manner of little creature was this child of Alexander and Molly?

Glancing about to assure herself all was in order, she put the light out, and, with hand outstretched against the darkness, moved to the door, when there swept over her again the vision of Molly clinging to Alexander, and again she felt the surrender of the man, the fierce closing of his arms, and again she was shaken by his passion.

And even after she reached her room and sat down at her desk to the ledger of household accounts, it came over her, and [Pg 34] she paused, her hand pressed to her hot cheek.

But that a little creature had cried itself to sleep in the next room she did not dream. She would have cried herself, had she known it, she, to whom tears came seldom and hard. But she was a slow awakening soul, groping, and she did not know.

The next morning Harriet sat in Alexina’s room putting criss-cross initials on a pile of unmarked little garments. It was part of the creed that clothes be marked.

Presently, as the child came to her aunt’s knee for a completed garment, Harriet laid a hand on the little shoulder. Demonstration came hard and brought a flush of embarrassment with it.

“Alexina,” she said, “you haven’t mentioned your mother!”

The child stood silent but there came a repeated swallowing in her throat while a slow red welled up over the little face.

[Pg 36] Harriet had a feeling of sudden liking and understanding. “You would rather—you prefer not?”

The child nodded, but later, as if from some fear of appearing unresponsive, she brought an album from her trunk and spread it open on Harriet’s knee. She seemed a loyal small soul to her kinsfolk, mainly her mother’s people, and turning the leaves went through the enumeration.

At one page—“Daddy,” she said.

“Daddy” applied in a baby’s cadence to Alexander! Daddy! It was a revelation of that part of her brother’s life which Harriet had forgotten in accounting assets. “Daddy,” called fearlessly, with intonation unconsciously dear and appealing. And Alexander had been that to his child!

There was no picture of Molly, but there was a torn and vacant space facing [Pg 37] Alexander. Had the child removed one? She bore resentment then? Harriet had no idea how far a child of nine could comprehend and feel the situation.

She would have been surprised at other things a child of nine can feel. If the routine of the house dragged dully to Alexina, Harriet never suspected it. The personal attention was detailed to Nelly, who divined more—Nelly, the freckle-faced, humorous-eyed house girl, taken from the Orphans’ Home and trained by Harriet’s mother. But, then, Nelly had been orphaned herself, and had known those first days following asylum consignment and perhaps had not forgot. Her sympathy expressed itself through the impersonal, the Blair training not having encouraged the other.

“Such a be-yewtiful dress,” said she, laying out the clothes for her charge.

[Pg 38] Which was true; no child of Molly’s would have suffered for clothes, Molly loving them too well herself.

“And such be-yewtiful slippers,” said Nelly, with Alexina in her lap, pulling up the little stocking and buttoning the strap about the ankle.

Alexina’s hand held tight to Nelly’s hard, firm arm, steadying herself. Perhaps she divined the intention. “Can I come, too, when you go to set the table?” she asked.

But Harriet never suspected. Nor again, that evening while she and Austen read under the lamp, did Harriet know that Alexina, standing at the open parlour window gazing at the children playing on the sidewalk, was fighting back passionate tears of an outraged love and a baffling sense of injustice.

All at once a child’s treble came in from the pavement.

[Pg 39] “Can’t you come play?”

Alexina turned, with backward look of eager inquiry to her aunt, who had come behind her to see who called.

“As you please; go if you want,” said Harriet good-humouredly.

Austen, too, glanced out. Tip-toe on the stone curbing of the iron fence perched a little girl, spokesman for the group of children behind her.

“Who is the child?” he asked his sister.

“Her name is Carringford. She is a grand-daughter of the old Methodist minister who lives at the corner; secretary of his church board, or something, isn’t he? I’ve noticed two or three little Carringfords playing in the yard as I go by, and all of them handsome.”

Austen placed them at once. The child’s mother was the daughter of the old minister, [Pg 40] and, with husband and children, lived in the little brown house with him. An interest in the details of the human affairs about him was an unexpected phase in Austen’s character. He liked to know what a man was doing, his income, his habits, his family ties.

“I know Carringford,” he remarked; “he is book-keeper for Williams, a good, steady man. As you say, a handsome child, exceedingly so.”

Harriet watched until the little niece joined the group outside. “Gregarious little creatures they seem to be,” she remarked. There was good-humour in her tone, but there was no understanding.

The next day was Sunday. On Monday it rained. Tuesday evening Alexina stood at the parlour window as before, looking out. The little figure looked very solitary.

[Pg 41] “May I go play?” suddenly she asked. The voice was low, there was no note even of wistfulness, it was merely the question. There are children who suffer silently.

“Why not?” Harriet rejoined, looking up from her magazine. She was the last person to restrict any one needlessly.

The little niece went forth. The children had not come for her again. Perhaps they did not want her, but, even with this fear upon her, go she must.

At the gate she paused and with the big house in its immaculate yard behind her, gazed up and down.

It was a quiet street with the houses set irregularly back from fences of varying patterns, and the brick sidewalks were raised and broken in places by the roots of huge sycamores and maples along the curbs.

But the cropped head of Alexina turned [Pg 42] this way and that in vain. The street was deserted, the stillness lonesome. She swallowed hard. She knew where the little girl named Emily Carringford lived, for she had pointed out the house that first evening as they ran past in play, so Alexina slowly crossed the street, hoping Emily might be at her gate.

But first, as she went along, came a wide brick cottage, sitting high above a basement, a porch across the front. She gazed in between the pickets of the fence, for it seemed nice in there. The ground was mossy under the trees, and the untrimmed bushes made bowers with their branches. She would like to play in this yard. Her eyes travelled on to the house. A gentleman sat in a cane arm-chair at the foot of the steps, smoking, and on the porch was a lady in a white dress with ribbons. The house [Pg 43] looked old and the yard looked old, and so did the gentleman, but the lady was young; maybe she was going to a party, for it was a gauzy dress and the ribbons were rosy.

Alexina liked the cottage and the lady, and the big, wide yard, and somehow did not feel as lonesome as she had. She started on to find Emily, but at that moment the gate of the cottage swung out across her path. How could she know that the boy upon it, lonely, too, had planned the thing from the moment of her starting up the street?

“Oh,” said Alexina, and stopped, and looked at the boy, uncomfortably immaculate in fresh white linen clothes, but he was absorbed in the flight of a bird across the rosy western sky.

“Come and play,” said the straightforward Alexina. Companionship was what she was in search of.

[Pg 44] The boy, without looking at her, shook his head, not so much as if he meant no, but as if he did not know how to say yes.

Perhaps she divined this, for approaching the gate and fingering its hasp, she asked,

“Why?”

The boy, assuming a sort of passivity of countenance as for cover to shyness, kicked at the gate, then scowled as he twisted his neck within the stiff circle of his round collar with the combative air of one who wars against starch. “There’s nobody to play with,” he said; “they’ve all gone to the Sunday-school picnic. I don’t go to that church,” nodding in the direction of a brick structure down the street.

“You go to the same one as my Aunt Harriet and my uncle,” Alexina informed him. “I saw you there, and your name is William. [Pg 45] I heard the lady calling you that, coming out.”

The gate which had swung in swung out again, bringing the boy nearer this outspoken little girl, whose unconsciousness was putting him more at his ease. He had seen her at church, too, but he could not have told her so.

“What’s the rest of your name—William what?”

Such a question makes a shy person very miserable, but the interest was pleasing.

“William Leroy,” said the boy tersely. Then, as if in amend for the abruptness, he added: “Sometimes they call it the other way, King William, you know.”

“Who do?”

“Father and mother.”

“You mean when you’re pretending?”

The gate stopped in its jerkings. There [Pg 46] had been enough about the name. He was an imperious youngster. “No, I don’t,” he said; “it’s William Leroy backward.”

The little girl looked mystified, but evidently thought best to change a subject about which the person concerned seemed testy. “I saw one once,” she said sociably; “a real one. He was in a carriage, with horses and soldiers, and a star on his coat.”

“One what?” demanded the boy.

“A king, a real one, you know.”

Now, this princeling on the gate knew when his own sex were guying and he knew the remedy. He did not know this little girl, but he would not have thought it of her.

“A real—what?” he demanded.

“A real king, but they don’t say king; they say ‘l’empereur.’”

William looked stern. “I don’t know [Pg 47] what you mean,” he returned; “where did you see any king?”

The grave eyes were not one bit abashed. “In Paris, where we lived,” said the little girl. “There was a boy named Tommy watching at the hotel window, too, and he said, ‘Vive le roi,’ and Marie, my bonne, she said, ‘Sh—h: l’empereur!’”

The effect of this was unexpected, for the boy, descending from the gate, turned a keenly irradiated countenance upon her. “Do you mean Paris, my father’s Paris, Paris in France?”

“Why,” said the little girl, regarding him with some surprise, “yes.” For he was taking her by the hand in a masterful fashion.

“Come in,” he commanded. “I want you to tell father; that’s father there.”

But Alexina, friendly soul, went willingly enough with him through the gate and up [Pg 48] the wide pavement between bordering beds of unflourishing perennials.

“Listen, father,” William Leroy was calling to the gentleman at the foot of the steps; “she’s been in Paris, your Paris.”

The gentleman’s ivory-tinted fingers removed the cigar from his lips. As he turned the western light fell on his lean, clean-shaven face, thin-flanked beneath high cheek-bones. From between grey brows thick as a finger rose a Louis Philippe nose, its Roman prominence accentuated by the hollowness of the cheeks. The iron-grey hair, thrown back off the face, fell, square-cut, to the coat collar behind.

Never a word spoke the gentleman, only, cigar in hand, waited, eagle-countenanced, sphinx-like. Yet straight Alexina came to his side, and her baby eyes, quick to dilate, now confidingly calm, met the ones looking [Pg 49] out piercingly from their retreat beneath the heavy brows, and quite as a matter of course a little hand rested on his knee as she stood there, and equally as naturally, his face impassive, did the fingers of the gentleman close upon it.

A silent compact, silently entered into, for before a word was interchanged the animated contralto of the lady came down from above. “Who is the little girl, son? What is your name, dear?”

Son’s wince was visible. He had no knowledge of the little girl’s name, but he did not want to say so.

But she was answering for herself, looking up at the pretty lady, dressed as though for a party. “It’s Mary Alexina Blair,” she was saying, “but my Aunt Harriet says it’s to be just Alexina now.”

“Oh,” said the lady. There was a little [Pg 50] silence before she spoke again. “It must be Alexander Blair’s child, Georges. Come up, dear, and let me see you.”

But King William, balancing himself on the back of his father’s chair, objected. “Hurry, then, mother,” he demanded; “we want to play.”

But Alexina had gone up the steps obediently. The eyes of the lady were dark and slumbrous, but in them was the slightly helpless look of short vision. She drew the child close for inspection.

The fair hair, the even brows, the clear-gazing eyes she seemed to have expected, but the dilation in those same wondering eyes raised to hers, the short upper-lip, the full under one that trembled—these the lady did not know. “A sensitiveness, a warmth,” she said, half aloud. What did she mean? Then she raised her voice.

[Pg 51] “See, Willy Leroy, how she stands for me, while you pull away if I so much as lay my hand on you.”

“But you look so close,” objected Willy, “and you fix my hair, and you say my collar ain’t straight. You’ve seen her now, mother; you’ve seen her close, and I want her to come sit on the step.”

“Go, then, little Mary Alexina Blair,” said the lady; “he’s a little ingrate whose mother has to barter with him for every concession he makes her.” And, smiling at herself, her face alight and arch with the animation of her smile, Charlotte Leroy sat back in the scarlet settee and respread her draperies as a bird its plumage, touching the ribbons at her waist and throat, resettling them with the air of one who takes frank pleasure in their presence and becomingness. This done, she viewed her hands, charming [Pg 52] hands heavy with costly rings, and finally, reassured at all points, she relaxed her buoyant figure and looked around with smiling return to her surroundings. It was for no party she was dressed but for her own satisfaction.

“Your initials spell Mab,” King William was telling Alexina as they sat on the step; “that means you’ll be rich. Mine don’t spell anything. I’m named for my grandfather up in Woodford, William Ransome. He’s dead. Father’s don’t either—Georges Gautier Hippolyte Leroy. His father ran away from France because he was a Girondist, and came to Louisville because it was French, and father’s been to Paris, too; haven’t you, father?”

The gentleman thus adjured removed his cigar and addressed his wife. “It begins to amount to garrulity. If the opposite sex [Pg 54] produces this at ten, what are we to expect later on?”

Mrs. Leroy’s voice had a note of defence in it, as if she could not brook even humorous criticism of the boy. It was plain where the passionate ardour in her nature was centred.

“I’m glad, I’m glad to see it,” she declared. “I was afraid it was not in him, I was beginning to fear he was a self-sufficient little monster.”

But her son was continuing the family history. “Mother’s name was Charlotte Ransome; wasn’t it, mother? When I’m a man I’m going to buy my grandfather’s stock farm back, and we’ll live there; won’t we, mother?”

But the impulsive Charlotte, veering around, here took her husband’s side: “‘I’m going to—I’m going to,’” she mimicked the [Pg 55] boy, then began to chant derisively as in words familiar to both:

But it only gave him an idea. He was not often a host. It was going to his head. “Wait!” he ordered, to whom it was not quite clear, and tore into the house, to be back almost at once, bearing a beribboned guitar.

“Now,” he said, depositing it upon his mother’s lap; “now, sing it for her; sing it right, mother. It’s ‘The Ram of Derby.’” This to Alexina, with a sudden shyness as he found himself addressing her.

But she, unconscious soul, did not recognize it, hers being an all-absorbed interest, and, reassured, young William went on:

“There was a William Ransome once, [Pg 56] when he was little, sat on General Washington’s knee, and General Washington sang him ‘The Ram of Derby.’ Go on, mother, sing it.”

And Charlotte, with eyes laughing down on the two upturned faces, “went on,” her jewelled fingers bringing the touch of a practised hand upon the strings, her buoyant figure responsive to the rhythm, while into the Munchausen recital she threw a dash, a swing that rendered the interest breathless.

And so on through the tale. King William, at her knees, clapped his hands. Alexina, by him, clapped hers, too, for joy of companionship, while the third listener sat with unchanging countenance below. But he liked it, somehow one knew he liked it, knew that he was listening down there in the dusk.

Perhaps Charlotte knew it, too. The vibrant twang slowed to richer chords, broke into rippling chromatic, caught a new measure, a minor note, and her contralto began:

[Pg 58] But this was only so much suggestion for her son’s active brain. “Tell her, mother,” he begged, pulling at Charlotte’s sleeve; “tell her about the ‘King William.’”

“And it has lain dormant, this egotism, unsuspected,” came up from out of the dusk.

Charlotte’s fingers swept the chords, her eyes fixed adoringly on her little son’s face, the while she sang on, absently, softly:

But King William, far from being harrowed by the woeful enumeration, laid an imperious hand on the strings. “Tell her, mother; I want you to tell her.”

“Come then, and kiss mother, and I will.”

He moved the intervening step and [Pg 59] submitted a cheek reluctantly. “Just one and you said you’d tell.”

But Charlotte, imperious herself, waved him off; she’d none of him now. “It’s because he’s a vain boy, little Mary Alexina Blair, and filled with self-importance, that he wants you to know, and he only wants me to tell you because he has not quite the assurance to do it himself; that is why he wants me to tell about the great, white-prowed Argo—”

“We call them bows, not prows,” came up out of the dusk.

But she refused the correction. “—The white-prowed Argo that is building across the river, to go in search of a golden fleece for little Jason here, a boat large, oh larger even than those other boats of little Jason’s father, the Captain down there, which used to float up and down the Mississippi, and [Pg 60] which vanished one day into the maw of the Confederacy—”

But Jason was lifting his voice. “Not that way; make her stop, father; that ain’t the way!”

But mother was not to be hurried out of her revenge. “And this big, white ark is one day going to float off on the flood of Hope, bearing Jason and his father and his mother, the last plank of fortune between them and—”

Jason was beating with his hands on the steps. “Make her stop, father; make her tell it right; she don’t understand what mother means. Do you?” with an appeal to the absorbed Alexina.

That small soul jumped and looked embarrassed to know what to say, for direct admissions are not always polite. “I had an ark once,” she stated, “but I sucked the [Pg 61] red off Noah, and Marie, my bonne, took it away.”

Leaning down, Charlotte Leroy swept the baby-voiced creature up into her lap. There was a passion of maternity in the act. “You innocent,” she said, and held her fast.

It was nice to be there; the ribbons and the lacy ruffles were soft beneath her cheek, and the dark eyes of the lady were smiling down.

The child turned suddenly and clung to Charlotte with passionate responsiveness.

“It’s about the boat his father is building, Willy wants you to know, little Mab,” the lady was telling her, “and how, the other day, the Captain down there and our friends and Willy and I went aboard her, on the ways at the shipyard over the river, and how, at the ax-stroke, as she slid down and out across the water, Willy broke the bottle on [Pg 62] the bow and christened the boat ‘King William.’”

“Just so,” came up in the Captain’s voice.

The moon was rising slowly.

“There’s some one at the gate,” cried Willy.

“It’s for me,” said Alexina, starting up; “it’s Nelly and she’s hunting me.”

Later, Nelly, leading her across the street, was saying, “I don’t believe Miss Harriet is going to like it when she knows where you’ve been.”

“Why?”

But Nelly couldn’t say; “except that they’re the only ladies on the street not knowing each other,” she explained.

The two went in. Alexina dropped Nelly’s hand and walked into the parlour and across to Harriet’s knee. Austen sat reading on the other side of the table.

[Pg 63] “I’ve been over to a boy’s house,” said Alexina; “his name is King William and their other name is Leroy.”

Harriet held the cambric strip of embroidery from her and viewed it. “Austen,” she asked, “is Alexina to play indiscriminately with the children on the square?”

Austen looked across at his sister. “It is within your authority to decide,” he returned, “but I know of no reason why she should not.”

Harriet made no response. Outwardly she was concerned with some directions to Nelly, waiting to take the child to bed, but inwardly she was wondering if Austen ever could have cared for this Charlotte Ransome.

He sat long after Harriet had gone. Then, rising abruptly, he went out the front door and walked to the corner of the house. It [Pg 64] was dark in the coachman’s room above the stable, and the master could go to bed secure that his oil was not being wasted.

That was all, yet he did not go in. The night was perfect, full of moonlight and the scent of earth and growing things. It was so still the houses along the street seemed asleep.

Almost furtively, the gaze of Austen lifted to the cottage, dark and silent across the way. He had been the one who would not forgive; the other had been only an impetuous girl.

He stood there long. Perhaps his face was colder, his lips pressed to a thinner line; perhaps it was the moonlight. Then he turned and went into the house.

Alexina came to Harriet with information.

“Emily goes to school to her aunt, and King William goes there, too.”

“Do they?” returned Harriet. Her interest was good-humoured rather than ardent.

“I’d like to go, too,” said her niece.

“Oh,” from Harriet, understanding at last; “but isn’t school about over?”

“There’s two weeks more.”

“If it will make you happy, why not, if the teacher does not object?”

So Alexina went with Emily to school. King William was there, but he hardly [Pg 66] noticed her, seeming gloomy and given to taking his slate off into corners.

“He don’t want to come,” explained Emily; “he’s the only boy.”

“Then what does he come for?” queried the practical Alexina.

“His mother won’t let him go to a public school.”

There was more to be learned about William. He fought the boys who went to the public school, because they jeered him in his ignominy. Alexina saw it happening up the alley but, strangely enough, when William appeared at school, he seemed cheered up, though something of a wreck.

Out of school, Alexina often went over to Emily’s house to play. There were no servants there, but her mamma beat up things in crocks, and her great-aunty, a brisk little old woman with sharp eyes, made yeast [Pg 67] cakes and dried them out under the arbour and milked the cow, too, and Emily’s little brother, Oliver, carried milk to the neighbours. Once in the spotless, shining kitchen, Alexina was allowed to wield a mop in a dish-pan and, still again, to stir at batter in a bowl.

In the room which would have been the parlour in another house, Emily’s grandfather Pryor sat at a table with books around him, and wrote on big sheets of paper in close writing. He was a stern old man and his hair stood out fine and white about his head. Once, as he passed across the front porch, he looked at Emily, then stopped, pointing to the chain about her neck. It was Alexina’s little gold necklace which Emily had begged to wear.

“Take it off,” he said.

Emily obeyed, but her checks were flaming, [Pg 68] and when he had gone she threw her head back. “When I’m grown, I mean to have them of my own, and wear them, too,” she said.

She seemed happier away from home. “Let’s go over to your house,” she always said. She liked grown people, too, and Uncle Austen once patted her head, and after she had gone said to Aunt Harriet: “A handsome child, an unusually pleasing child.”

But while Alexina played thus with Emily, more often she trudged across to King William’s.

The nature of engrossment was different over there. Often as not it was theology, though this, to be sure, was the Captain’s word for it, not his son’s.

Willy’s mother, like Aunt Harriet, was a Presbyterian. “If I had been a better one,” [Pg 69] she lamented to her husband one evening, “I would know how to meet his questions now. You don’t take one bit of the responsibility of his religious training, Captain Leroy.”

The creed of King William’s mamma, when she came to formulate it, seemed a stern one, and it lost nothing in its setting forth by reason of her determination to do her duty by her son.

“Thank Heaven I had to sit under these things when I was a child, however I hated it then, or I could not do my part by him now,” she told the Captain. “I want him,” fervently, “to be everything I am not.”

“Which might,” suggested the Captain, “be a prig, you know.”

But King William, listening, drank in these things. He had a garden patch in the back yard and knew the nature and habits [Pg 70] of every vegetable in it, and being strictly a utilitarian, he weeded out sickly plants and unknown cotyledons with a ruthless hand.

Alexina expostulated. “Maybe it hurts ’em,” she feared.

“Maybe it does,” said the inexorable William; “but they are like the souls born to be damned. Put ’em on the brush pile there, and after a while we’ll burn ’em.”

At other times the yard was a sea-girt coral reef and they the stranded mariners. Generally Alexina accepted everything. The stories were new to her. But when she did have knowledge of a thing she stood firm; for instance, about the ocean, that you could not land every few moments of your progress and throw out gang-planks.

“For I’ve been there,” she insisted, “and you couldn’t, you know.”

At times they adjourned to the commons [Pg 71] behind the stable, which, in reality, were plains frequented by Indians, or, if the yard palled or rain drove them in, there was fat, black, plausible Aunt Rose in the basement kitchen to talk to, and if Aunt Rose proved fractious and drove them out, together with her own brood generally skulking around, before a threatening dish-rag or broom, there was Charlotte to be beguiled from more serious occupation into doing her son’s bidding.

Charlotte was always busy. The cottage and all in it had come to her from her father’s aunt. She had been accustomed to seeing the windows, the furniture, the mirrors, the silver door knobs shining; therefore, she knew such things ought to shine, and since there was no one in these days but herself to do it, she cleaned, polished, rubbed, and went to bed limp.

[Pg 72] One afternoon in the late fall, when the children sought her, she was pasting papers over glasses of jelly. “We went over the river to see the boat yesterday,” King William was saying to Alexina as they came in. “Tell her about it, mother; about the gold star at the bow.”

The papers did not want to stick. “He’s a bad boy, little Mab,” Charlotte informed her. “He made me take him over before he’d promise to go to the party he’s asked to. He wants to be a little boor who won’t know how to act when he grows up.”

“I’m never goin’ to parties when I’m grown up, so what’s the use learning how to act at ’em now?” argued her son.

Charlotte dropped a mucilaged paper. “But you promised,” she reminded him anxiously; “you promised—”

“Oh, well—” admitted her son.

[Pg 73] Charlotte kept a fire in her parlour. Coal was at a fabulous price in the South that winter, but she had never known a parlour without a fire, and here she and the children sat in the afternoons, the Captain often returning early and joining them.

“Georges,” said Charlotte upon one of these occasions, “we are poor.”

The Captain smoked in silence. Perhaps he had realized it before. His keen eyes, however, were regarding her.

“But,” said Charlotte, “we go on acting as though we were rich.”

“Just so,” said the Captain.

“When your trousers get shabby, you order more like them. Did you ever ask your tailor if he has anything cheaper?”

Now, trousers of that pearl tint peculiar to the finest fabrics were as characteristic a part of the Captain’s garb as were the black [Pg 74] coat, the low-cut vest, the linen cambric handkerchiefs like small tablecloths for size, the tall silk hat, and the Henry Clay collar above the black silk stock.

“Did you ever ask him if he had anything cheaper, Georges?”

“I can’t say,” admitted Georges, “that I ever did.” For the Captain had never asked his tailor a price in his life. When the bill came he paid it. But it takes income to meet eccentricities of this sort, while now—

Did the Captain, glancing from his wife to the boy on the floor, seem to age, to shrink in his chair? For Charlotte was thirty-two and the boy was ten and the Captain was nearing sixty.

“And when your shirts and Willy’s things and mine give out, I’ve been going right on to the sisters ordering more. Convent prices are high, Georges.”

[Pg 75] The Captain had nothing to say.

“Adele has been telling me that she cuts down her eldest boy’s things for the little one.” Adele was the widow of a Confederate general. “So I borrowed her patterns. Listening to Adele talk, I realized, Georges, that you and Willy and I have to learn how to be poor.”

It was at this point that Charlotte brought forth from the chair behind her a voluminous broadcloth cape, such as men then wore for outer wrap, and spread it on the mahogany centre-table.

“It’s perfectly good, if you did discard it, and I’m going to cut it into something for Willy; I didn’t tell Adele I never had tried, she is so capable, but I borrowed her patterns.” And Charlotte brought forth a paper roll.

The Captain, in the arm-chair, sat and [Pg 76] watched. Alexina, from his knee, where he had a way of lifting her, watched too. Willy, from a perch on the arm of the sofa, offered suggestions.

This was early in the afternoon. At six o’clock the Captain, lighting another of an uninterrupted series of cigars, was still watching silently. On the sofa sat Charlotte, in tears. On the table, tailor fashion, sat King William, sorting patterns, while Nelly, who had come for Alexina, stood by and directed.

“How does he know?” Mrs. Leroy, watching her son a little anxiously, asked the Captain. “I wouldn’t like him to develop such a bent. He doesn’t get it from you—or from me.”

“I look at my legs,” said William, “and then I build it that way.”

Another afternoon the Captain looked up [Pg 77] from his smoking and spoke to Charlotte. The children were on the floor turning the pages of a picture paper.

“We have succeeded in securing the loan on a mortgage on the boat. Cowan arranged it through his bank. It was at a higher rate than we had agreed on, but we’d lost all the time we could spare. We’ll push ahead now and have things finished by spring.”

That night, over at the Blairs’, as Alexina climbed into her place at the table Austen was speaking to Harriet. “You remember I told you I was looking for an investment of the proceeds of those bonds of Alexina’s which matured the other day? This morning I took a mortgage on a boat Cowan is building at his yard.”

Alexina heard her name, but did not understand.

There came a day the following spring when Alexina, seeking her aunt, wept.

Harriet gazed at her dismayed, at a loss. Heretofore Alexina had taken her tears to Nelly or had kept them to herself.

“They are going away,” she said, “King William and them; going in the boat.”

This, as a matter to cry about, was a mystery to Harriet. “Going where?” she asked.

“To get the golden fleece,” her weeping niece assured her.

“Well,” said Harriet amused, “let us hope they may find it, but why the tears?”

[Pg 79] Alexina got up and carried her tears to her own room. It spoke her infantile capacity to discriminate that she bore away no resentment; there are things that the Aunt Harriets with the best wills in the world need not be expected to understand.

King William’s mother, telling her, had held her tight and rocked her; King William’s father, when he saw her lip trembling afterward, had lifted her on his knee.

Going into the big, high room which was her own, Alexina shut the door. Then she cast herself on the floor. A little hand, beating about wildly, came upon Sally Ann, lying unregarded there. Gathering her in fiercely, presently the sobs grew quieter. Later she wiped her eyes upon her child and, kissing her tenderly, put her down and went over to King William’s; the time was short and she could have Sally Ann afterward.

[Pg 80] The next day the cottage was closed and the shutters made fast. Alexina felt lonesome even to look over there, and Sally Anns are but silent comforters.

But in a year the Leroys came back from St. Louis, between which city and New Orleans the splendid new “King William” had been plying. The judgment of Captain Leroy had been at fault, which is a sad thing when a man is sixty. The day of the steamboat had passed, because that of the railroad had come. The “King William” as a venture was a failure.

So, one morning, the cottage windows were open to the Virginia creeper outside them. Nelly whispered the news to Alexina at breakfast, and the child could not eat for hurry to be through and go over.

It was as if King William had been watching for her, for he came running to the gate [Pg 81] and took her hand to conduct her in. He was taller and thinner, and looked different, and neither could find anything to say on the way.

Charlotte was sitting in the parlour, her wraps half-removed. They had only just arrived, and the stillness and closeness of a newly opened house was about. “How does one pack furniture for moving, Willy?” Charlotte began as he appeared.

But he was bringing Alexina. “Tell her about it, mother,” he said, “so she’ll know.”

Charlotte, brightening, held out her arms. Then, having lifted the child to her lap and kissed her, her face grew wan again. “There was no fleece for Jason, little Mab; there is no Land of Colchis, never believe it. And those seeking, like Willy and me, are like to wander until youth and hope and opportunity are gone.”

[Pg 82] She was crying against a little cropped head. King William stood irresolute, then put an arm around her. “Not that way, mummy; don’t tell it that way.”

But control had given way. “And there is nothing for little Jason. He must go and fight with his bare hands like any poor churl’s child—oh, Willy, Willy, my little son—”

Alexina, in her lap, sat very still; King William was staring hard into space.

Charlotte went on. “We are going away, little Mab, Willy and his father and I; going away for good. Everything that ever was ours, this cottage and all, is gone. We are going to a place in the South called Aden, where there are a few acres that still are ours only because they would not sell.”

A moment they all were still. Then the little breast of Alexina began to heave. The [Pg 83] Leroys had never seen her this way. Sally Ann had, many times, and Nelly once or twice. She threw herself upon Charlotte. “I want to go, too; I want to go; I hate it—there,” with a motion of self toward the big, white house visible through the window. “I hate it, and I want to go too.”

They were all crying now. Suddenly King William stood forth in front of the child. “When we get rich, I’ll come for you,” he said.

The practical Alexina looked through the arrested tears as she sat up. “But if you don’t get rich?” she questioned.

Charlotte laughed. She was half child herself. The laugh died. The other half was woman. “Then he won’t come; if he is the son of his father, he won’t come.”

Alexina Blair, at twenty, returned from school to her uncle’s home with but small emotion, as, at fourteen, she had left with little regret, yet the shady streets, the open front doors, the welcomes called from up-stairs windows as she passed—evidences that she was back among her own people in the South—all at once made her glad to be here.

How could she have felt emotion over a mere return to Uncle Austen’s house? She might have felt enthusiasm over Nelly, but Nelly was married to the gardener at her old asylum and a Katy had taken her place. [Pg 88] The house was the same. If only its stone façade might be allowed to mellow, to grey a little! But, newly cleaned, it stood coldly immaculate in its yard of shaven lawn set about with clipped shrubberies. As for her uncle, Alexina found herself applying the same adjectives to him, shaven, immaculate, cold.

She wondered what he thought of her, but Uncle Austen never made personal remarks.

Aunt Harriet, on joining her niece in the East early in the summer, had looked at her consideringly. She seemed pleased.

“Why,” she said, “Alexina, you are a Tennyson young person, tall and most divinely—you are a little more intense in your colouring than is usual with a Blair. I’m glad.”

The somewhat doubtful smile on the girl’s face deepened as if a sudden radiance [Pg 89] leaped into it. She seized her aunt’s hand. “Oh,” she said, “you’re very nice, Aunt Harriet.”

Harriet laughed, rather pleased than not, but she still was studying the girl. “She is impulsive and she doesn’t look set,” the aunt was telling herself—was it gratefully? “perhaps she is less Blair than I thought.”

Austen Blair too, in fact, now viewed his niece with complacency—she fulfilled the Blair requirements—but he talked of other things.

“It is the intention of your aunt and myself,” he told her promptly, “to introduce you at once to what will be your social world, for it is well for everyone to have local attachment.”

As the matter progressed it appeared that social introduction, as Uncle Austen understood [Pg 90] it, was largely a matter of expenditure. In all investment it is the expected thing to place where there is likeliest return. Therefore he scanned the invitation list earnestly.

“She can afford to do the thing as it should be done,” he remarked to Harriet.

“She? But Austen—” Harriet hesitated. “I supposed it was ours, this affair; it seems the least—”

Austen looked at her. At first he did not comprehend, then he replied with some asperity. “I have so far kept sentiment and business apart in managing Alexina’s affairs.”

Harriet was silenced. It was becoming less and less wise to oppose Austen. He had his own ideas about the matter. “The thing is to be done handsomely,” he set forth, “but,” as qualification, “judiciously.”

Therefore he stopped an acquaintance on [Pg 91] the street a day or two before the affair. “Are we to have the pleasure of seeing you on Tuesday?” he asked, even a little ostentatiously, for the young man had neglected to accept or decline.

Austen reported the result to Harriet. “For there is no use ordering a supper for five hundred if but four hundred and ninety-nine are coming,” he told her.

“No?” said Harriet.

“Exactly,” said her brother.

Alexina, present at the conversation, looked from the one to the other. Uncle Austen was Uncle Austen; there was a slight lift of the girlish shoulders as she admitted this. But Aunt Harriet—

For Harriet had changed. She had been changing these past two summers. She was absent, forgetful, absorbed, even irritable. Aunt Harriet! And recalled, she [Pg 92] would colour and look about in startled fashion.

Alexina and Harriet had been always on terms friendly and pleasant, but scarcely to be called intimate; terms that, after a cordial good-night, closed the door between their rooms, and while the girl had been conscious of a fondness for her serene and capable aunt, there were times too, when, met by that same serenity, she had felt she must rebel, and in secret had thrown her young arms out in impotent, passionate protest.

But now Aunt Harriet forgot and neglected and grew cross like any one, and the sententious utterances of Uncle Austen irritated her. Alexina, going into her room one day, found her with her head bowed on the desk. Was she crying? The girl slipped out.

Was Aunt Harriet unhappy? The heart of Alexina warmed to her.

[Pg 93] The evening of Alexina’s return home Harriet had come to her door. To twenty years thirty-eight seems pitiably far along in life, yet Harriet called up no such feeling in Alexina. No passion of living writ itself on Galatea’s check while she was in marble, and Alexina, opening the door to the tap, thought her aunt beautiful.

“If there are callers to-night,” Harriet said, “I want you to come down. My friends are not too elderly,” she smiled in the old, good-humoured way, “to be nice to you this winter.”

So later Alexina went down to the library, a room long unfurnished, now the only really cheerful room in the house. Was it because Harriet had furnished it?

The girl always had realized in an indefinite way that Harriet was a personage; later, in their summers away together, she [Pg 94] discovered that men liked her handsome aunt.

In the library she found a group who, from the conversation, seemed to be accustomed to dropping in thus in casual fashion. They were men of capacity and presence, one felt that, even in the case of that long avowed person of fashion, Mr. Marriot Bland, who was getting dangerously near to that time of life when he would be designated an old beau. He was a personage, too, of his type. Alexina shook hands with him gaily; she had been used to his coming since she first came to live with Aunt Harriet and Uncle Austen. Harriet introduced the others. The girl’s spirits rose; she felt it was nice that she should be knowing them.

And they? What does middle-age feel, looking upon youth, eager-eyed, buoyant, [Pg 95] flushed with the first glow from that unknown about to dawn?

Oh, it was a charming evening. The girl showed she thought it so and smiled, and the men smiled too, as they joined Harriet in making her the young centre. Perhaps there was a tender something in the smiles. Was it for their own gone youth?

One, a Major Rathbone, stayed after the others left. He sat building little breastworks on the centre-table out of matches taken from the bronze stand by the lamp, and as he talked he looked over every now and then at Harriet on the other side.

In the soberer reaction following the breaking up of the group, Alexina, too, found time to look at Harriet. It was an Aunt Harriet that she had never seen before. The colour was richly dyeing this Harriet’s cheeks, and the jewel pendant at her throat [Pg 96] rose and trembled and fell, and her white lids fell, too, though she had laughed when her eyes met laughter and something else in the brown eyes of the Major fixed on her.

It was of Mr. Marriot Bland the Major was speaking, his smooth, brown hand caressing his clean-shaven chin.

“So cruelly confident are you cold Dianas,” he was saying. “Now, even a Penelope must hold out the lure of her web to an old suitor, but you Dianas—”

Alexina laughed. She had jumped promptly into a liking for this lean, brown man with the keen, humorous eyes and the deliberate yet quick movements, and now absorbed in her thoughts, was unconscious of her steadfast gaze fixed on him, until he suddenly brought his eyes to bear on hers with humorous inquiry.

“Well?” he inquired.

[Pg 97] Now Alexina, being fair, showed blushes most embarrassingly, but she could laugh too.

“What’s the conclusion?” he demanded; “or would it be wiser not to press inquiry?”

Alexina laughed again. She knew she liked this Major.

“I was wondering,” she confessed. “You are so different from what I expected. I heard Aunt Harriet and Uncle Austen discussing one of your editorials, so I read it. I thought you would be different—fiercer maybe, and—er—more aggressive.”

Alexina began to blush again, for the Major was so edified at something that his enjoyment was suspicious.

“But no man is expected to live down to his editorials, Miss Alexina; I write ’em for a living.”

He stroked his chin as he regarded her, [Pg 98] but there was laughter too out of the tail of his eye across at Aunt Harriet, who was laughing also, though she looked teased.

Later Alexina learned more about this Major Rathbone. It was Emily Carringford who told her. Emily came over promptly the day after Alexina’s return and, admitted by Katy, ran up as of old.

Alexina, hearing her name called, turned from a melée of unpacking as the other reached the open doorway.

“Oh, Emily,” she said, and stood and gazed.

Emily stood, too, archly, and, meeting Alexina’s look, laughed. Her blush was an acknowledgment; she did not even pretend to misunderstand Alexina’s meaning.

“Aunt Harriet told me how—how lovely you were, and Uncle Austen told me last night that my friend, Miss Emily, he [Pg 99] considered an ‘unusually good-looking woman—a handsome woman, in fact.’” The niece had her uncle’s every conciseness of tone as she quoted. “But somehow with it all, I wasn’t prepared—”

She came forward with hands out.

Emily forgot to take the hands. “Did he say that, really, Alexina?”

“Yes; why shouldn’t he? Oh, Emily, it must be joy, or does it frighten you to know you’re so beautiful?”

She was letting her fingers touch, almost with awe, the curve of the other’s check.

Emily laughed, but the crimson on the cheek deepened.

“And your voice?” demanded Alexina. “I want to hear you sing. Did you get the place in the choir you wrote me about?”

“Miss Harriet got it for me; it was she who suggested it—that is, she got Mr. [Pg 100] Blair to get it for me. It’s at your church, you know.”

“Uncle Austen? No. Did he, really?”

But the surprise in Alexina’s voice was unfair to her uncle. To help people to the helping of themselves was part of his creed. He looked upon it as a furthering of the general social economy, as indeed he had pointed out more than once to those he was thus assisting.

But Alexina had many things to ask. She pushed Emily into a chair.

“Is it pleasant—the choir?” she began.

“Pleasant? Well,” Emily looked away and coloured, “I like the money; I’ve never been able to have any clothes before. There was a scene at home about it—my singing, I mean, in any but my own church, and for money. It was grandfather, of course; it’s always been grandfather. He says it’s [Pg 101] spiritual prostitution, whatever he means by that, taking money for praising the Lord in an alien faith.” She laughed in an off-hand way. “No, I’ll be honest, I’d have to be sooner or later with you, anyhow, I hate it—not the work and rehearsals so much, but the being patronized. When some of those women stop me, with the air of doing the gracious thing, to tell me they have enjoyed my singing, oh, I could—” Again she laughed, but her cheeks were blazing. Then she leaned over and fingered some of the girlish fineries strewing the bed. “I hate it at home, too, when it comes to being honest about things—six of us, with grandfather and Aunt Carrie making eight, in that little house!”

Later, Alexina chanced to refer to Major Rathbone. She spoke enthusiastically, for [Pg 102] she either liked people or she did not like them. “Hadn’t you heard about him?” asked Emily in surprise. “He met Miss Harriet two years ago, and he’s been coming ever since. It’s funny, too, that he should. He’s the Major Rathbone, you know—”

But Alexina looked unenlightened.

“Why,” said Emily, “the Major Rathbone who was the Confederate guerrilla—the one who captured and burned a train-load of stuff your grandfather and Mr. Austen had contracted to deliver for the government. I’ve heard people tell about it a dozen different ways since he’s been coming to see Miss Harriet. Anyway, however it was, the government at the time put a price on his head and your grandfather and Mr. Austen doubled it. And now they say he’s in love with Miss Harriet!”

In love! With Aunt Harriet! Alexina [Pg 103] grew hot. Aunt Harriet! She felt strange and queer. But Emily was saying more. “Mr. Blair and Major Rathbone aren’t friends even yet; I was here to supper with Miss Harriet one evening last winter, and Mr. Blair was furious over an editorial by Major Rathbone in the paper that day about some political appointments from Washington. Mr. Blair had had something to do with them, had been consulted about them from Washington, it seems. Major Rathbone’s a Catholic, too.”

It rushed upon Alexina that she had spoken to the Major of a family discussion over his editorials.

Emily stayed until dusk. As Alexina went down to the door with her, they met Uncle Austen just coming in. He stopped, shook hands, and asked how matters were in the choir.

[Pg 104] As Emily ran down the steps he addressed himself to his niece. “A praiseworthy young girl to have gone so practically to work.” Then as Emily at the gate looked back, nodding archly, he repeated it. “A praiseworthy young girl, praiseworthy and sensible,” his gaze following her, “as well as handsome.”

He went in, but Alexina lingered on the broad stone steps. It was October and the twilight was purple and hazy. Chrysanthemums bloomed against the background of the shrubbery; the maples along the street were drifting leaves upon the sidewalk; the sycamores stood with their shed foliage like a cast garment about their feet, raising giant white limbs naked to heaven.

There were lights in the wide brick cottage. Strangers lived there now. A swinging [Pg 105] sign above the gate set forth that a Doctor Ransome dwelt therein.

The eddying fall of leaves is depressing. Autumn anyhow is a melancholy time. Alexina, going in, closed the door.

The Blair reception to introduce their niece may have been to others the usual matter of lights and flowers and music, but to the niece it was different, for it was her affair.

She and her aunt went down together. The stairway was broad, and to-night its banister trailed roses.

Alexina was radiant. She even marched up and kissed her uncle. Things felt actually festive.

All the little social world was there that evening. Alexina recalled many of the girls and the older women; of the older men she [Pg 107] knew a few, but of the younger only one could she remember as knowing.

He was a rosy-cheeked youth with vigorous, curling yellow hair, and he came up to her with a hearty swinging of the body, smiling in a friendly and expectant way, showing nice, square teeth, boyishly far apart. She knew him at once; he had gone to dancing school when she did, and she was glad to see him.

“Why, Georgy,” she said, and held out a hand, just as it was borne in upon her that Georgy wore a young down on his lip and was a man.

“Oh,” she said, blushing, “I hope you don’t mind?”

He was blushing, too, but the smile that showed his nice spaced teeth was honest.

“No,” he said; “I don’t mind.”

Which Alexina felt was good of him and [Pg 108] so she smiled back and chatted and tried to make it up. And Georgy lingered and continued to linger and to blush beneath his already ruddy skin until Harriet, turning, sent him away, for Harriet was a woman of the world and Georgy was the rich and only child of the richest mamma present, and the other mammas were watching.

Alexina’s eyes followed him as he went, then wandered across the long room to Emily. She had expected to feel a sense of responsibility about Emily, but Uncle Austen, after a long and precise survey of her from across the room, put his eye-glasses into their case and went to her. His prim air of unbending for the festive occasion was almost comical as he brought up youths to make them known. This done he fell back to his general duties as host.

But Alexina, watching Emily, felt [Pg 109] dissatisfaction with her, her archness was overdone, her laughter was anxious.

Why should Emily stoop to strive so? With her milk-white skin and chestnut hair, with her red lips and starry eyes there should have belonged to her a pride and a young dignity. Alexina, youthfully stern, turned away.

It brought her back to the amusing things of earth, however, that Uncle Austen should take Emily home when it was over. Would Emily be arch with Uncle Austen? Picture it!