The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 6, Slice 4, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 6, Slice 4

"Cincinnatus" to "Cleruchy"

Author: Various

Release Date: March 14, 2010 [EBook #31641]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 6, SL 4 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz, Juliet Sutherland and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

CINCINNATUS,1 LUCIUS QUINCTIUS, (b. c. 519 B.C.), one of the heroes of early Rome, a model of old Roman virtue and simplicity. A persistent opponent of the plebeians, he resisted the proposal of Terentilius Arsa (or Harsa) to draw up a code of written laws applicable equally to patricians and plebeians. He was in humble circumstances, and lived and worked on his own small farm. The story that he became impoverished by paying a fine incurred by his son Caeso is an attempt to explain the needy position of so distinguished a man. Twice he was called from the plough to the dictatorship of Rome in 458 and 439. In 458 he defeated the Aequians in a single day, and after entering Rome in triumph with large spoils returned to his farm. The story of his success, related five times under five different years, possibly rests on an historical basis, but the account given in Livy of the achievements of the Roman army is obviously incredible.

See Livy iii. 26-29; Dion. Halic. x. 23-25; Florus i. 11. For a critical examination of the story see Schwegler, Römische Geschichte, bk. xxviii. 12; Sir G. Cornewall Lewis, Credibility of early Roman History, ch. xii. 40; W. Ihne, History of Rome, i.; E. Pais, Storia di Roma, i. ch. 4 (1898).

1 I.e. the “curly-haired.”

CINDERELLA (i.e. little cinder girl), the heroine of an almost universal fairy-tale. Its essential features are (1) the persecuted maiden whose youth and beauty bring upon her the jealousy of her step-mother and sisters, (2) the intervention of a fairy or other supernatural instrument on her behalf, (3) the prince who falls in love with and marries her. In the English version, a translation of Perrault’s Cendrillon, the glass slipper which she drops on the palace stairs is due to a mistranslation of pantoufle en vair (a fur slipper), mistaken for en verre. It has been suggested that the story originated in a nature-myth, Cinderella being the dawn, oppressed by the night-clouds (cruel relatives) and finally rescued by the sun (prince).

See Marian Rolfe Cox, Cinderella; Three Hundred and Forty-five Variants (1893); A Lang, Perrault’s Popular Tales (1888).

CINEAS, a Thessalian, the chief adviser of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus. He studied oratory in Athens, and was regarded as the most eloquent man of his age. He tried to dissuade Pyrrhus from invading Italy, and after the defeat of the Romans at Heraclea (280 B.C.) was sent to Rome to discuss terms of peace. These terms, which are said by Appian (De Rebus Samniticis, 10, 11) to have included the freedom of the Greeks in Italy and the restoration to the Bruttians, Apulians and Samnites of all that had been taken from them, were rejected chiefly through the vehement and patriotic speech of the aged Appius Claudius Caecus the censor. The withdrawal of Pyrrhus from Italy was demanded, and Cineas returned to his master with the report that Rome was a temple and its senate an assembly of kings. Two years later Cineas was sent to renew negotiations with Rome on easier terms. The result was a cessation of hostilities, and Cineas crossed over to Sicily, to prepare the ground for Pyrrhus’s campaign. Nothing more is heard of him. He is said to have made an epitome of the Tactica of Aeneas, probably referred to by Cicero, who speaks of a Cineas as the author of a treatise De Re Militari.

See Plutarch, Pyrrhus, 11-21; Justin xviii. 2; Eutropius ii. 12; Cicero, Ad Fam. ix. 25.

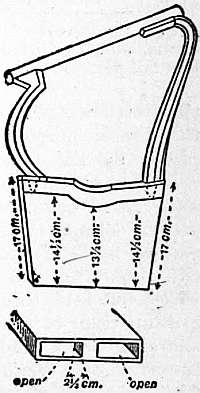

CINEMATOGRAPH, or Kinematograph (from κίνημα, motion, and γράφειν, to depict), an apparatus in which a series of views representing closely successive phases of a moving object are exhibited in rapid sequence, giving a picture which, owing to persistence of vision, appears to the observer to be in continuous motion. It is a development of the zoetrope or “wheel of life,” described by W.G. Horner about 1833, which consists of a hollow cylinder turning on a vertical axis and having its surface pierced with a number of slots. Round the interior is arranged a series of pictures representing successive stages of such a subject as a galloping horse, and when the cylinder is rotated an observer looking through one of the slots sees the horse apparently in motion. The pictures were at first drawn by hand, but photography was afterwards applied to their production. E. Muybridge about 1877 obtained successive pictures of a running horse by employing a row of cameras, the shutters of which were opened and closed electrically by the passage of the horse in front of them, and in 1883 E.J. Marey of Paris established a studio for investigating the motion of animals by similar photographic methods.

The modern cinematograph was rendered possible by the invention of the celluloid roll film (employed by Marey in 1890), on which the serial pictures are impressed by instantaneous photography, a long sensitized film being moved across the focal plane of a camera and exposed intermittently. In one apparatus for making the exposures a cam jerks the film across the field once for each picture, the slack being gathered in on a drum at a constant rate. In another four lenses are rotated so as to give four images for each rotation, the film travelling so as to present a new portion in the field as each lens comes in place. Sixteen to fifty pictures may be taken per second. The films are developed on large drums, within which a ruby electric light may be fixed to enable the process to be watched. A positive is made from the negative thus obtained, and is passed through an optical lantern, the images being thus successively projected through an objective lens upon a distant screen. For an hour’s exhibition 50,000 to 165,000 pictures are needed. To regulate the feed in the lantern a hole is punched in the film for each picture. These holes must be extremely accurate in position; when they wear the feed becomes irregular, and the picture dances or vibrates in an unpleasant manner. Another method of exhibiting cinematographic effects is to bind the pictures together in book form by one edge, and then release them from the other in rapid succession by means of the thumb or some mechanical device as the book is bent backwards. In this case the subject is viewed, not by projection, but directly, either with the unaided eye or through a magnifying glass.

Cinematograph films produced by ordinary photographic processes, being in black and white only, fail to reproduce the colouring of the subjects they represent. To some extent this defect has been remedied by painting them by hand, but this method is too expensive for general adoption, and moreover does not yield very satisfactory results. Attempts to adapt three-colour photography, by using simultaneously three films, each with a source of light of appropriate colour, and combining the three images on the screen, have to overcome great difficulties in regard to maintenance of register, because very minute errors of adjustment between the pictures on the films are magnified to an intolerable extent by projection. In a process devised by G.A. Smith, the results of which were exhibited at the Society of Arts, London, in December 1908, the number of colour records was reduced to two. The films were specially treated to increase their sensitiveness to red. The photographs were taken through two colour filters alternately interposed in front of the film; both admitted white and yellow, but one, of red, was in addition specially concerned with the orange and red of the subject, and the other, of blue-green, with the green, blue-green, blue and violet. The camera was arranged to take not less than 16 pictures a second through each filter, or 32 a second in all. The positive transparency made from the negative thus obtained 375 was used in a lantern so arranged that beams of red (composed of crimson and yellow) and of green (composed of yellow and blue) issued from the lens alternately, the mechanism presenting the pictures made with the red filter to the red beam, and those made with the green filter to the green beam. A supplementary shutter was provided to introduce violet and blue, to compensate for the deficiency in those colours caused by the necessity of cutting them out in the camera owing to the over-sensitiveness of the film to them, and the result was that the successive pictures, blending on the screen by persistence of vision, gave a reproduction of the scene photographed in colours which were sensibly the same as those of the original.

The cinematograph enables “living” or “animated pictures” of such subjects as an army on the march, or an express train at full speed, to be presented with marvellous distinctness and completeness of detail. Machines of this kind have been devised in enormous numbers and used for purposes of amusement under names (bioscope, biograph, kinetoscope, mutograph, &c.) formed chiefly from combinations of Greek and Latin words for life, movement, change, &c., with suffixes taken from such words as σκοπεῖν, to see, γράφειν, to depict; they have also been combined with phonographic apparatus, so that, for example, the music of a dance and the motions of the dancer are simultaneously reproduced to ear and eye. But when they are used in public places of entertainment, owing to the extreme inflammability of the celluloid film and its employment in close proximity to a powerful source of light and heat, such as is required if the pictures are to show brightly on the screen, precautions must be taken to prevent, as far as possible, the heat rays from reaching it, and effective means must be provided to extinguish it should it take fire. The production of films composed of non-inflammable material has also engaged the attention of inventors.

See H.V. Hopwood, Living Pictures (London, 1899), containing a bibliography and a digest of the British patents, which is supplemented in the Optician, vol. xviii. p. 85; Eugène Trutat, La Photographie animée (1899), which contains a list of the French patents. For the camera see also Photography: Apparatus.

CINERARIA. The garden plants of this name have originated from a species of Senecio, S. cruentus (nat. ord. Compositae), a native of the Canary Isles, introduced to the royal gardens at Kew in 1777. It was known originally as Cineraria cruenta, but the genus Cineraria is now restricted to a group of South African species, and the Canary Island species has been transferred to the large and widespread genus Senecio. Cinerarias can be raised freely from seeds. For spring flowering in England the seeds are sown in April or May in well-drained pots or pans, in soil of three parts loam to two parts leaf-mould, with one-sixth sand; cover the seed thinly with fine soil, and press the surface firm. When the seedlings are large enough to handle, prick them out in pans or pots of similar soil, and when more advanced pot them singly in 4-in. pots, using soil a trifle less sandy. They should be grown in shallow frames facing the north, and, if so situated that the sun shines upon the plants in the middle of the day, they must be slightly shaded; give plenty of air, and never allow them to get dry. When well established with roots, shift them into 6-in. pots, which should be liberally supplied with manure water as they get filled with roots. In winter remove to a pit or house, where a little heat can be supplied whenever there is a risk of their getting frozen. They should stand on a moist bottom, but must not be subjected to cold draughts. When the flowering stems appear, give manure water at every alternate watering. Seeds sown in March, and grown on in this way, will be in bloom by Christmas if kept in a temperature of from 40° to 45° at night, with a little more warmth in the day; and those sown in April and May will succeed them during the early spring months, the latter set of plants being subjected to a temperature of 38° or 40° during the night. If grown much warmer than this, the Cineraria maggot will make its appearance in the leaves, tunnelling its way between the upper and lower surfaces and making whitish irregular markings all over. Such affected leaves must be picked off and burned. Green fly is a great pest on young plants, and can only be kept down by fumigating or vaporizing the houses, and syringing with a solution of quassia chips, soft soap and tobacco.

CINGOLI (anc. Cingulum), a town of the Marches, Italy, in the province of Macerata, about 14 m. N.W. direct, and 17 m. by road, from the town of Macerata. Pop. (1901) 13,357. The Gothic church of S. Esuperanzio contains interesting works of art. The town occupies the site of the ancient Cingulum, a town of Picenum, founded and strongly fortified by Caesar’s lieutenant T. Labienus (probably on the site of an earlier village) in 63 B.C. at his own expense. Its lofty position (2300 ft.) made it of some importance in the civil wars, but otherwise little is heard of it. Under the empire it was a municipium.

CINNA, a Roman patrician family of the gens Cornelia. The most prominent member was Lucius Cornelius Cinna, a supporter of Marius in his contest with Sulla. After serving in the war with the Marsi as praetorian legate, he was elected consul in 87 B.C. Breaking the oath he had sworn to Sulla that he would not attempt any revolution in the state, Cinna allied himself with Marius, raised an army of Italians, and took possession of the city. Soon after his triumphant entry and the massacre of the friends of Sulla, by which he had satisfied his vengeance, Marius died. L. Valerius Flaccus became Cinna’s colleague, and on the murder of Flaccus, Cn. Papirius Carbo. In 84, however, Cinna, who was still consul, was forced to advance against Sulla; but while embarking his troops to meet him in Thessaly, he was killed in a mutiny. His daughter Cornelia was the wife of Julius Caesar, the dictator; but his son, L. Cornelius Cinna, praetor in 44 B.C., nevertheless sided with the murderers of Caesar and publicly extolled their action.

The hero of Corneille’s tragedy Cinna (1640) was Cn. Cornelius Cinna, surnamed Magnus (after his maternal grandfather Pompey), who was magnanimously pardoned by Augustus for conspiring against him.

CINNA, GAIUS HELVIUS, Roman poet of the later Ciceronian age. Practically nothing is known of his life except that he was the friend of Catullus, whom he accompanied to Bithynia in the suite of the praetor Memmius. The circumstances of his death have given rise to some discussion. Suetonius, Valerius Maximus, Appian and Dio Cassius all state that, at Caesar’s funeral, a certain Helvius Cinna was killed by mistake for Cornelius Cinna, the conspirator. The last three writers mentioned above add that he was a tribune of the people, while Plutarch, referring to the affair, gives the further information that the Cinna who was killed by the mob was a poet. This points to the identity of Helvius Cinna the tribune with Helvius Cinna the poet. The chief objection to this view is based upon two lines in the 9th eclogue of Virgil, supposed to have been written 41 or 40 B.C. Here reference is made to a certain Cinna, a poet of such importance that Virgil deprecates comparison with him; it is argued that the manner in which this Cinna, who could hardly have been any one but Helvius Cinna, is spoken of implies that he was then alive; if so, he could not have been killed in 44. But such an interpretation of the Virgilian passage is by no means absolutely necessary; the terms used do not preclude a reference to a contemporary no longer alive. It has been suggested that it was really Cornelius, not Helvius Cinna, who was slain at Caesar’s funeral, but this is not borne out by the authorities. Cinna’s chief work was a mythological epic poem called Smyrna, the subject of which was the incestuous love of Smyrna (or Myrrha) for her father Cinyras, treated after the manner of the Alexandrian poets. It is said to have taken nine years to finish. A Propempticon Pollionis, a send-off to [Asinius] Pollio, is also attributed to him. In both these poems, the language of which was so obscure that they required special commentaries, his model appears to have been Parthenius of Nicaea.

See A. Weichert, Poëtarum Latinorum Vitae (1830); L. Müller’s edition of Catullus (1870), where the remains of Cinna’s poems are printed; A. Kiessling, “De C. Helvio Cinna Poëta” in Commentationes Philologicae in honorem T. Mommsen (1878); O. Ribbeck, Geschichte der römischen Dichtung, i. (1887); Teuffel-Schwabe, Hist. of Roman Lit. (Eng. tr. 213, 2-5); Plessis, Poésie latine (1909).

CINNABAR (Ger. Zinnober), sometimes written cinnabarite, a name applied to red mercuric sulphide (HgS), or native vermilion, the common ore of mercury. The name comes from the Greek κιννάβαρι, used by Theophrastus, and probably applied to several distinct substances. Cinnabar is generally found in a massive, granular or earthy form, of bright red colour, but it occasionally occurs in crystals, with a metallic adamantine lustre. The crystals belong to the hexagonal system, and are generally of rhombohedral habit, sometimes twinned. Cinnabar presents remarkable resemblance to quartz in its symmetry and optical characters. Like quartz it exhibits circular polarization, and A. Des Cloizeaux showed that it possessed fifteen times the rotatory power of quartz (see Polarization of Light). Cinnabar has higher refractive power than any other known mineral, its mean index for sodium light being 3.02, whilst the index for diamond—a substance of remarkable refraction—is only 2.42 (see Refraction). The hardness of cinnabar is 3, and its specific gravity 8.998.

Cinnabar is found in all localities which yield quicksilver, notably Almaden (Spain), New Almaden (California), Idria (Austria), Landsberg, near Ober-Moschel in the Palatinate, Ripa, at the foot of the Apuan Alps (Tuscany), the mountain Avala (Servia), Huancavelica (Peru), and the province of Kweichow in China, whence very fine crystals have been obtained. Cinnabar is in course of deposition at the present day from the hot waters of Sulphur Bank, in California, and Steamboat Springs, Nevada.

Hepatic cinnabar is an impure variety from Idria in Carniola, in which the cinnabar is mixed with bituminous and earthy matter.

Metacinnabarite is a cubic form of mercuric sulphide, this compound being dimorphous.

For a general description of cinnabar, see G.F. Becker’s Geology of the Quicksilver Deposits of the Pacific Slope, U.S. Geol. Surv. Monographs, No. xiii. (1888).

CINNAMIC ACID, or Phenylacrylic Acid, C9H8O2 or C6H6.CH:CH.COOH, an acid found in the form of its benzyl ester in Peru and Tolu balsams, in storax and in some gum-benzoins. It can be prepared by the reduction of phenyl propiolic acid with zinc and acetic acid, by heating benzal malonic acid, by the condensation of ethyl acetate with benzaldehyde in the presence of sodium ethylate or by the so-called “Perkin reaction”; the latter being the method commonly employed. In making the acid by this process benzaldehyde, acetic anhydride and anhydrous sodium acetate are heated for some hours to about 1800 C, the resulting product is made alkaline with sodium carbonate, and any excess of benzaldehyde removed by a current of steam. The residual liquor is filtered and acidified with hydrochloric acid, when cinnamic acid is precipitated, C6H5CHO+CH3COONa = C6H5CH:CH.COONa + H2O. It may be purified by recrystallization from hot water. Considerable controversy has taken place as to the course pursued by this reaction, but the matter has been definitely settled by the work of R. Fittig and his pupils (Annalen, 1883, 216, pp. 100, 115; 1885, 227, pp. 55, 119), in which it was shown that the aldehyde forms an addition compound with the sodium salt of the fatty acid, and that the acetic anhydride plays the part of a dehydrating agent. Cinnamic acid crystallizes in needles or prisms, melting at 133°C; on reduction it gives phenyl propionic acid, C6H5.CH2.CH2.COOH. Nitric acid oxidizes it to benzoic acid and acetic acid. Potash fusion decomposes it into benzoic and acetic acids. Being an unsaturated acid it combines directly with hydrochloric acid, hydrobromic acid, bromine, &c. On nitration it gives a mixture of ortho and para nitrocinnamic acids, the former of which is of historical importance, as by converting it into orthonitrophenyl propiolic acid A. Baeyer was enabled to carry out the complete synthesis of indigo (q.v.). Reduction of orthonitrocinnamic acid gives orthoaminocinnamic acid, C6H4(NH2)CH:CH.COOH, which is of theoretical importance, as it readily gives a quinoline derivative. An isomer of cinnamic acid known as allo-cinnamic acid is also known.

For the oxy-cinnamic adds see Coumarin.

CINNAMON, the inner bark of Cinnamomum zeylanicum, a small evergreen tree belonging to the natural order Lauraceae, native to Ceylon. The leaves are large, ovate-oblong in shape, and the flowers, which are arranged in panicles, have a greenish colour and a rather disagreeable odour. Cinnamon has been known from remote antiquity, and it was so highly prized among ancient nations that it was regarded as a present fit for monarchs and other great potentates. It is mentioned in Exod. xxx. 23, where Moses is commanded to use both sweet cinnamon (Kinnamon) and cassia, and it is alluded to by Herodotus under the name κιννάμωμον, and by other classical writers. The tree is grown at Tellicherry, in Java, the West Indies, Brazil and Egypt, but the produce of none of these places approaches in quality that grown in Ceylon. Ceylon cinnamon of fine quality is a very thin smooth bark, with a light-yellowish brown colour, a highly fragrant odour, and a peculiarly sweet, warm and pleasing aromatic taste. Its flavour is due to an aromatic oil which it contains to the extent of from 0.5 to 1%. This essential oil, as an article of commerce, is prepared by roughly pounding the bark, macerating it in sea-water, and then quickly distilling the whole. It is of a golden-yellow colour, with the peculiar odour of cinnamon and a very hot aromatic taste. It consists essentially of cinnamic aldehyde, and by the absorption of oxygen as it becomes old it darkens in colour and develops resinous compounds. Cinnamon is principally employed in cookery as a condiment and flavouring material, being largely used in the preparation of some kinds of chocolate and liqueurs. In medicine it acts like other volatile oils and has a reputation as a cure for colds. Being a much more costly spice than cassia, that comparatively harsh-flavoured substance is frequently substituted for or added to it. The two barks when whole are easily enough distinguished, and their microscopical characters are also quite distinct. When powdered bark is treated with tincture of iodine, little effect is visible in the case of pure cinnamon of good quality, but when cassia is present a deep-blue tint is produced, the intensity of the coloration depending on the proportion of the cassia.

CINNAMON-STONE, a variety of garnet, belonging to the lime-alumina type, known also as essonite or hessonite, from the Gr. ἣσσων, “inferior,” in allusion to its being less hard and less dense than most other garnet. It has a characteristic red colour, inclining to orange, much like that of hyacinth or jacinth. Indeed it was shown many years ago, by Sir A.H. Church, that many gems, especially engraved stones, commonly regarded as hyacinth, were really cinnamon-stone. The difference is readily detected by the specific gravity, that of hessonite being 3.64 to 3.69, whilst that of hyacinth (zircon) is about 4.6. Hessonite is rather a soft stone, its hardness being about that of quartz or 7, whilst the hardness of most garnet reaches 7.5. Cinnamon-stone comes chiefly from Ceylon, where it is found generally as pebbles, though its occurrence in its native matrix is not unknown.

CINNAMUS [Kinnamos], JOHN, Byzantine historian, flourished in the second half of the 12th century. He was imperial secretary (probably in this case a post connected with the military administration) to Manuel I. Comnenus (1143-1180), whom he accompanied on his campaigns in Europe and Asia Minor. He appears to have outlived Andronicus I., who died in 1185. Cinnamus was the author of a history of the period 1118-1176, which thus continues the Alexiad of Anna Comnena, and embraces the reigns of John II. and Manuel I., down to the unsuccessful campaign of the latter against the Turks, which ended with the disastrous battle of Myriokephalon and the rout of the Byzantine army. Cinnamus was probably an eye-witness of the events of the last ten years which he describes. The work breaks off abruptly; originally it no doubt went down to the death of Manuel, and there are indications that, even in its present form, it is an abridgment. The text is in a very corrupt state. The author’s hero is Manuel; he is strongly impressed with the superiority of the East to the West, and is a determined opponent of the pretensions of the papacy. But he cannot be reproached with undue bias; he writes with the 377 straightforwardness of a soldier, and is not ashamed on occasion to confess his ignorance. The matter is well arranged, the style (modelled on that of Xenophon) simple, and on the whole free from the usual florid bombast of the Byzantine writers.

Editio princeps, C. Tollius (1652); in Bonn, Corpus Scriptorum Hist. Byz., by A. Meineke (1836), with Du Cange’s valuable notes; Migne, Patrologia Graeca, cxxxiii.; see also C. Neumann, Griechische Geschichtsschreiber im 12. Jahrhundert (1888); H. von Kap-Herr, Die abendländische Politik Kaiser Manuels (1881); C. Krumbacher, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur (1897).

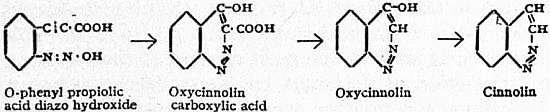

CINNOLIN, C8H6N2, a compound isomeric with phthalazine, prepared by boiling dihydrocinnolin dissolved in benzene with freshly precipitated mercuric oxide. The solution is filtered and the hydrochloride of the base precipitated by alcoholic hydrochloric acid; the free base is obtained as an oil by adding caustic soda. It may be obtained in white silky needles, melting at 24-25°C. and containing a molecule of ether of crystallization by cooling the oil dissolved in ether. The free base melts at 39°C. It is a strong base, forming stable salts with mineral acids, and is easily soluble in water and in the ordinary organic solvents. It has a taste resembling that of chloral hydrate, and leaves a sharp irritation for some time on the tongue; it is also very poisonous (M. Busch and A. Rast, Berichte, 1897, 30, p. 521). Cinnolin derivatives are obtained from oxycinnolin carboxylic acid, which is formed by digesting orthophenyl propiolic acid diazo chloride with water. Oxycinnolin carboxylic acid on heating gives oxycinnolin, melting at 225°, which with phosphorus pentachloride gives chlorcinnolin. This substance is reduced by iron filings and sulphuric acid to dihydrocinnolin.

The relations of these compounds are here shown:—

CINO DA PISTOIA (1270-1336), Italian poet and jurist, whose full name was Guittoncino de’ Sinibaldi, was born in Pistoia, of a noble family. He studied law at Bologna under Dinus Muggelanus (Dino de Rossonis: d. 1303) and Franciscus Accursius, and in 1307 is understood to have been assessor of civil causes in his native city. In that year, however, Pistoia was disturbed by the Guelph and Ghibelline feud. The Ghibellines, who had for some time been the stronger party, being worsted by the Guelphs, Cino, a prominent member of the former faction, had to quit his office and the city of his birth. Pitecchio, a stronghold on the frontiers of Lombardy, was yet in the hands of Filippo Vergiolesi, chief of the Pistoian Ghibellines; Selvaggia, his daughter, was beloved by Cino (who was probably already the husband of Margherita degli Unghi); and to Pitecchio did the lawyer-poet betake himself. It is uncertain how long he remained at the fortress; it is certain, however, that he was not with the Vergiolesi at the time of Selvaggia’s death, which happened three years afterwards (1310), at the Monte della Sambuca, in the Apennines, whither the Ghibellines had been compelled to shift their camp. He visited his mistress’s grave on his way to Rome, after some time spent in travel in France and elsewhere, and to this visit is owing his finest sonnet. At Rome Cino held office under Louis of Savoy, sent thither by the Ghibelline leader Henry of Luxemburg, who was crowned emperor of the Romans in 1312. In 1313, however, the emperor died, and the Ghibellines lost their last hope. Cino appears to have thrown up his party, and to have returned to Pistoia. Thereafter he devoted himself to law and letters. After filling several high judicial offices, a doctor of civil law of Bologna in his forty-fourth year, he lectured and taught from the professor’s chair at the universities of Treviso, Siena, Florence and Perugia in succession; his reputation and success were great, his judicial experience enabling him to travel out of the routine of the schools. In literature he continued in some sort the tradition of Dante during the interval dividing that great poet from his successor Petrarch. The latter, besides celebrating Cino in an obituary sonnet, has coupled him and his Selvaggia with Dante and Beatrice in the fourth capitolo of his Trionfi d’ Amore.

Cino, the master of Bartolus, and of Joannes Andreae the celebrated canonist, was long famed as a jurist. His commentary on the statutes of Pistoia, written within two years, is said to have great merit; while that on the code (Lectura Cino Pistoia super codice, Pavia, 1483; Lyons, 1526) is considered by Savigny to exhibit more practical intelligence and more originality of thought than are found in any commentary on Roman law since the time of Accursius. As a poet he also distinguished himself greatly. He was the friend and correspondent of Dante’s later years, and possibly of his earlier also, and was certainly, with Guido Cavalcanti and Durante da Maiano, one of those who replied to the famous sonnet A ciascun’ alma presa e gentil core of the Vita Nuova. In the treatise De Vulgari Eloquio Dante refers to him as one of “those who have most sweetly and subtly written poems in modern Italian,” but his works, printed at Rome in 1559, do not altogether justify the praise. Strained and rhetorical as many of his outcries are, however, Cino is not without moments of true passion and fine natural eloquence. Of these qualities the sonnet in memory of Selvaggia, Io fui in sull’ alto e in sul beato monte, and the canzone to Dante, Avegnachè di omaggio più per tempo, are interesting examples.

The text-book for English readers is D.G. Rossetti’s Early Italian Poets, wherein will be found not only a memoir of Cino da Pistoia, but also some admirably translated specimens of his verse—the whole wrought into significant connexion with that friendship of Cino’s which is perhaps the most interesting fact about him. See also Ciampi, Vita e poesie di messer Cino da Pistoia (Pisa, 1813).

CINQ-MARS, HENRI COIFFIER RUZÉ D’EFFIAT, Marquis de (1620-1642), French courtier, was the second son of Antoine Coiffier Ruzé, marquis d’Effiat, marshal of France (1581-1632), and was introduced to the court of Louis XIII. by Richelieu, who had been a friend of his father and who hoped he would counteract the influence of the queen’s favourite Mlle. de Hautefort. Owing to his handsome appearance and agreeable manners he soon became a favourite of the king, and was made successively master of the wardrobe and master of the horse. After distinguishing himself at the siege of Arras in 1640, Cinq-Mars wished for a high military command, but Richelieu opposed his pretensions and the favourite talked rashly about overthrowing the minister. He was probably connected with the abortive rising of the count of Soissons in 1641; however that may be, in the following year he formed a conspiracy with the duke of Bouillon and others to overthrow Richelieu. This plot was under the nominal leadership of the king’s brother Gaston of Orleans. The plans of the conspirators were aided by the illness of Richelieu and his absence from the king, and at the siege of Narbonne Cinq-Mars almost induced Louis to agree to banish his minister. Richelieu, however, recovered, became acquainted with the attempt of Cinq-Mars to obtain assistance from Spain, and laid the proofs of his treason before the king, who ordered his arrest. Cinq-Mars was brought to trial, admitted his guilt, and was condemned to death. He was executed at Lyons on the 12th of September 1642. It is possible that Cinq-Mars was urged to engage in this conspiracy by his affection for Louise Marie de Gonzaga (1612-1667), afterwards queen of Poland, who was a prominent figure at the court of Louis XIII.; and this tradition forms part of the plot of Alfred de Vigny’s novel Cinq-Mars.

See Le P. Griffet, Histoire de Louis XIII; A. Bazin, Histoire de Louis XIII (1846); L. D’Astarac de Frontrailles, Relations des choses particulières de la cour pendant la faveur de M. de Cinq-Mars.

CINQUE CENTO (Italian for five hundred; short for 1500), in architecture, the style which became prevalent in Italy in the century following 1500, now usually called “16th-century work.” It was the result of the revival of classic architecture known as Renaissance, but the change had commenced already a century earlier, in the works of Ghiberti and Donatello in sculpture, and of Brunelleschi and Alberti in architecture.

CINQUE PORTS, the name of an ancient jurisdiction in the south of England, which is still maintained with considerable modifications and diminished authority. As the name implies, 378 the ports originally constituting the body were only five in number—Hastings, Romney, Hythe, Dover and Sandwich; but to these were afterwards added the “ancient towns” of Winchelsea and Rye with the same privileges, and a good many other places, both corporate and non-corporate, which, with the title of limb or member, held a subordinate position. To Hastings were attached the corporate members of Pevensey and Seaford, and the non-corporate members of Bulvarhythe, Petit Iham (Yham or Higham), Hydney, Bekesbourn, Northeye and Grenche or Grange; to Romney, Lydd, and Old Romney, Dengemarsh, Orwaldstone, and Bromehill or Promehill; to Dover, Folkestone and Faversham, and Margate, St John’s, Goresend (now Birchington), Birchington Wood (now Woodchurch), St Peter’s, Kingsdown and Ringwould; to Sandwich, Fordwich and Deal, and Walmer, Ramsgate, Reculver, Stonor (Estanor), Sarre (or Serre) and Brightlingsea (in Essex). To Rye was attached the corporate member of Tenterden, and to a Hythe the non-corporate member of West Hythe. The jurisdiction thus extends along the coast from Seaford in Sussex to Birchington near Margate in Kent; and it also includes a number of inland districts, at a considerable distance from the ports with which they are connected. The non-incorporated members are within the municipal jurisdiction of the ports to which they are attached; but the corporate members are as free within their own liberties as the individual ports themselves.

The incorporation of the Cinque Ports had its origin in the necessity for some means of defence along the southern seaboard of England, and in the lack of any regular navy. Up to the reign of Henry VII. they had to furnish the crown with nearly all the ships and men that were needful for the state; and for a long time after they were required to give large assistance to the permanent fleet. The oldest charter now on record is one belonging to the 6th year of Edward I.; and it refers to previous documents of the time of Edward the Confessor and William the Conqueror. In return for their services the ports enjoyed extensive privileges. From the Conquest or even earlier they had, besides various lesser rights—(1) exemption from tax and tallage; (2) soc and sac, or full cognizance of all criminal and civil cases within their liberties; (3) tol and team, or the right of receiving toll and the right of compelling the person in whose hands stolen property was found to name the person from whom he received it; (4) blodwit and fledwit, or the right to punish shedders of blood and those who were seized in an attempt to escape from justice; (5) pillory and tumbrel; (6) infangentheof and outfangentheof, or power to imprison and execute felons; (7) mundbryce (the breaking into or violation of a man’s mund or property in order to erect banks or dikes as a defence against the sea); (8) waives and strays, or the right to appropriate lost property or cattle not claimed within a year and a day; (9) the right to seize all flotsam, jetsam, or ligan, or, in other words, whatever of value was cast ashore by the sea; (10) the privilege of being a gild with power to impose taxes for the common weal; and (11) the right of assembling in portmote or parliament at Shepway or Shepway Cross, a few miles west of Hythe (but afterwards at Dover), the parliament being empowered to make by-laws for the Cinque Ports, to regulate the Yarmouth fishery, to hear appeals from the local courts, and to give decision in all cases of treason, sedition, illegal coining or concealment of treasure trove. The ordinary business of the ports was conducted in two courts known respectively as the court of brotherhood and the court of brotherhood and guestling,—the former being composed of the mayors of the seven principal towns and a number of jurats and freemen from each, and the latter including in addition the mayors, bailiffs and other representatives of the corporate members. The court of brotherhood was formerly called the brotheryeeld, brodall or brodhull; and the name guestling seems to owe its origin to the fact that the officials of the “members” were at first in the position of invited guests.

The highest office in connexion with the Cinque Ports is that of the lord warden, who also acts as governor of Dover Castle, and has a maritime jurisdiction (vide infra) as admiral of the ports. His power was formerly of great extent, but he has now practically no important duty to exercise except that of chairman of the Dover harbour board. The emoluments of the office are confined to certain insignificant admiralty droits. The patronage attached to the office consists of the right to appoint the judge of the Cinque Ports admiralty court, the registrar of the Cinque Ports and the marshal of the court; the right of appointing salvage commissioners at each Cinque Port and the appointment of a deputy to act as chairman of the Dover harbour board in the absence of the lord warden. Walmer Castle was for long the official residence of the lord warden, but has, since the resignation of Lord Curzon in 1903, ceased to be so used, and those portions of it which are of historic interest are now open to the public. George, prince of Wales (lord warden, 1903-1907), was the first lord warden of royal blood since the office was held by George, prince of Denmark, consort of Queen Anne.

Admiralty Jurisdiction.—The court of admiralty for the Cinque Ports exercises a co-ordinate but not exclusive admiralty jurisdiction over persons and things found within the territory of the Cinque Ports. The limits of its jurisdiction were declared at an inquisition taken at the court of admiralty, held by the seaside at Dover in 1682, to extend from Shore Beacon in Essex to Redcliff, near Seaford, in Sussex; and with regard to salvage, they comprise all the sea between Seaford in Sussex to a point five miles off Cape Grisnez on the coast of France, and the coast of Essex. An older inquisition of 1526 is given by R.G. Marsden in his Select Pleas of the Court of Admiralty, II. xxx. The court is an ancient one. The judge sits as the official and commissary of the lord warden, just as the judge of the high court of admiralty sat as the official and commissary of the lord high admiral. And, as the office of lord warden is more ancient than the office of lord high admiral (The Lord Warden v. King in his office of Admiralty, 1831, 2 Hagg. Admy. Rep. 438), it is probable that the Cinque Ports court is the more ancient of the two.

The jurisdiction of the court has been, except in one matter of mere antiquarian curiosity, unaffected by statute. It exercises only, therefore, such jurisdiction as the high court of admiralty exercised, apart from restraining statutes of 1389 and 1391 and enabling statutes of 1840 and 1861. Cases of collision have been tried in it (the “Vivid,” 1 Asp. Maritime Law Cases, 601). But salvage cases (the “Clarisse,” Swabey, 129; the “Marie,” Law. Rep. 7 P.D. 203) are the principal cases now tried. It has no prize jurisdiction. The one case in which jurisdiction has been given to it by statute is to enforce forfeitures under the statute of 1538.

Dr (afterwards the Right Hon. Robert Joseph) Phillimore succeeded his father as judge of the court from 1855 to 1875, being succeeded by Mr Arthur Cohen, K.C. As Sir R. Phillimore was also the last judge of the high court of admiralty, from 1867 (the date of his appointment to the high court) to 1875, the two offices were, probably for the first time in history, held by the same person. Dr Phillimore’s patent had a grant of the “place or office of judge official and commissary of the court of admiralty of the Cinque Ports, and their members and appurtenances, and to be assistant to my lieutenant of Dover castle in all such affairs and business concerning the said court of admiralty wherein yourself and assistance shall be requisite and necessary.” Of old the court sat sometimes at Sandwich, sometimes at other ports. But the regular place for the sitting of the court has for a long time been, and still is, the aisle of St James’s church, Dover. For convenience the judge often sits at the royal courts of justice. The office of marshal in the high court is represented in this court by a serjeant, who also bears a silver oar. There is a registrar, as in the high court. The appeal is to the king in council, and is heard by the judicial committee of the privy council. The court can hear appeals from the Cinque Ports salvage commissioners, such appeals being final (Cinque Ports Act 1821). Actions may be transferred to it, and appeals made to it, from the county courts in all cases, arising within the jurisdiction of the Cinque Ports as defined by that act. At the solemn installation of the lord warden the judge as the next principal officer installs him.

The Cinque Ports from the earliest times claimed to be exempt from the jurisdiction of the admiral of England. Their early charters do not, like those of Bristol and other seaports, express this exemption in terms. It seems to have been derived from the general words of the charters which preserve their liberties and privileges.

The lord warden’s claim to prize was raised in, but not finally decided by, the high court of admiralty in the “Ooster Ems,” 1 C. Rob. 284, 1783.

See S. Jeake, Charters of the Cinque Ports (1728); Boys, Sandwich and Cinque Ports; Knocker, Grand Court of Shepway (1862); M, Burrows, Cinque Ports (1895); F.M. Hueffer, Cinque Ports (1900); Indices of the Great White and Black Books of the Cinque Ports (1905).

CINTRA, a town of central Portugal, in the district of Lisbon, formerly included in the province of Estramadura; 17 m. W.N.W. of Lisbon by the Lisbon-Caçem-Cintra railway, and 6 m. N. by E. of Cape da Roca, the westernmost promontory of the European mainland. Pop. (1900) 5914. Cintra is magnificently situated on the northern slope of the Serra da Cintra, a rugged mountain mass, largely overgrown with pines, eucalyptus, cork and other forest trees, above which the principal summits rise in a succession of bare and jagged grey peaks; the highest being Cruz Alta (1772 ft.), marked by an ancient stone cross, and commanding a wonderful view southward over Lisbon and the Tagus estuary, and north-westward over the Atlantic and the plateau of Mafra. Few European towns possess equal advantages of position and climate; and every educated Portuguese is familiar with the verses in which the beauty of Cintra is celebrated by Byron in Childe Harold (1812), and by Camoens in the national epic Os Lusiadas (1572). One of the highest points of the Serra is surmounted by the Palacio da Pena, a fantastic imitation of a medieval fortress, built on the site of a Hieronymite convent by the prince consort Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg (d. 1885); while an adjacent part of the range is occupied by the Castello des Mouros, an extensive Moorish fortification, containing a small ruined mosque and a very curious set of ancient cisterns. The lower slopes of the Serra are covered with the gardens and villas of the wealthier inhabitants of Lisbon, who migrate hither in spring and stay until late autumn.

In the town itself the most conspicuous building is a 14th-15th-century royal palace, partly Moorish, partly debased Gothic in style, and remarkable for the two immense conical chimneys which rise like towers in the midst. The 18th-century Palacio de Seteaes, built in the French style then popular in Portugal, is said to derive its name (“Seven Ahs”) from a sevenfold echo; here, on the 22nd of August 1808, was signed the convention of Cintra, by which the British and Portuguese allowed the French army to evacuate the kingdom without molestation. Beside the road which leads for 3½ m. W. to the village of Collares, celebrated for its wine, is the Penha Verde, an interesting country house and chapel, founded by João de Castro (1500-1548), fourth viceroy of the Indies. De Castro also founded the convent of Santa Cruz, better known as the Convento de Cortiça or Cork convent, which stands at the western extremity of the Serra, and owes its name to the cork panels which formerly lined its walls. Beyond the Penha Verde, on the Collares road, are the palace and park of Montserrate. The palace was originally built by William Beckford, the novelist and traveller (1761-1844), and was purchased in 1856 by Sir Francis Cook, an Englishman who afterwards obtained the Portuguese title viscount of Montserrate. The palace, which contains a valuable library, is built of pure white stone, in Moorish style; its walls are elaborately sculptured. The park, with its tropical luxuriance of vegetation and its variety of lake, forest and mountain scenery, is by far the finest example of landscape gardening in the Iberian Peninsula, and probably among the finest in the world. Its high-lying lawns, which overlook the Atlantic, are as perfect as any in England, and there is one ravine containing a whole wood of giant tree-ferns from New Zealand. Other rare plants have been systematically collected and brought to Montserrate from all parts of the world by Sir Francis Cook, and afterwards by his successor, Sir Frederick Cook, the second viscount. The Praia das Maçãs, or “beach of apples,” in the centre of a rich fruit-bearing valley, is a favourite sea-bathing station, connected with Cintra by an extension of the electric tramway which runs through the town.

CIPHER, or Cypher (from Arab, şifr, void), the symbol 0, nought, or zero; and so a name for symbolic or secret writing (see Cryptography), or even for shorthand (q.v.), and also in elementary education for doing simple sums (“ciphering”).

CIPPUS (Lat. for a “post” or “stake”), in architecture, a low pedestal, either round or rectangular, set up by the Romans for various purposes such as military or mile stones, boundary posts, &c. The inscriptions on some in the British Museum show that they were occasionally funeral memorials.

CIPRIANI, GIOVANNI BATTISTA (1727-1785), Italian painter and engraver, Pistoiese by descent, was born in Florence in 1727. His first lessons were given him by an Englishman, Ignatius Heckford or Hugford, and under his second master, Antonio Domenico Gabbiani, he became a very clever draughtsman. He was in Rome from 1750 to 1753, where he became acquainted with Sir William Chambers, the architect, and Joseph Wilton, the sculptor, whom he accompanied to England in August 1755. He had already painted two pictures for the abbey of San Michele in Pelago, Pistoia, which had brought him reputation, and on his arrival in England he was patronized by Lord Tilney, the duke of Richmond and other noblemen. His acquaintance with Sir William Chambers no doubt helped him on, for when Chambers designed the Albany in London for Lord Holland, Cipriani painted a ceiling for him. He also painted part of a ceiling in Buckingham Palace, and a room with poetical subjects at Standlynch in Wiltshire. Some of his best and most permanent work was, however, done at Somerset House, built by his friend Chambers, upon which he lavished infinite pains. He not only prepared the decorations for the interior of the north block, but, says Joseph Baretti in his Guide through the Royal Academy (1780), “the whole of the carvings in the various fronts of Somerset Place—excepting Bacon’s bronze figures—were carved from finished drawings made by Cipriani.” These designs include the five masks forming the keystones to the arches on the courtyard side of the vestibule, and the two above the doors leading into the wings of the north block, all of which are believed to have been carved by Nollekens. The grotesque groups flanking the main doorways on three sides of the quadrangle and the central doorway on the terrace appear also to have been designed by Cipriani. The apartments in Sir William Chambers’s stately palace that were assigned to the Royal Academy, into which it moved in 1780, owed much to Cipriani’s graceful, if mannered, pencil. The central panel of the library ceiling was painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds, but the four compartments in the coves, representing Allegory, Fable, Nature and History, were Cipriani’s. These paintings still remain at Somerset House, together with the emblematic painted ceiling, also his work, of what was once the library of the Royal Society. It was natural that Cipriani should thus devote himself to adorning the apartments of the academy, since he was an original member (1768) of that body, for which he designed the diploma so well engraved by Bartolozzi. In recognition of his services in this respect the members presented him in 1769 with a silver cup with a commemorative inscription. He was much employed by the publishers, for whom he made drawings in pen and ink, sometimes coloured. His friend Bartolozzi engraved most of them. Drawings by him are in both the British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum. His best autograph engravings are “The Death of Cleopatra,” after Benvenuto Cellini; “The Descent of the Holy Ghost,” after Gabbiani; and portraits for Hollis’s memoirs, 1780. He painted allegorical designs for George III.’s state coach—which is still in use—in 1782, and repaired Verrio’s paintings at Windsor and Rubens’s ceiling in the Banqueting House at Whitehall. If his pictures were often weak, his decorative treatment of children was usually exceedingly happy. Some of his most pleasing work was that which, directly or indirectly, he executed for the decoration of furniture. He designed many groups of nymphs and amorini and medallion subjects to form 380 the centre of Pergolesi’s bands of ornament, and they were continually reproduced upon the elegant satin-wood furniture which was growing popular in his later days and by the end of the 18th century became a rage. Sometimes these designs were inlaid in marqueterie, but most frequently they were painted upon the satin-wood by other hands with delightful effect, since in the whole range of English furniture there is nothing more enchanting than really good finished satin-wood pieces. There can be little doubt that some of the beautiful furniture designed by the Adams was actually painted by Cipriani himself. He also occasionally designed handles for drawers and doors. Cipriani died at Hammersmith in 1785 and was buried at Chelsea, where Bartolozzi erected a monument to his memory. He had married an English lady, by whom he had two sons.

CIRCAR, an Indian term applied to the component parts of a subah or province, each of which is administered by a deputy-governor. In English it is principally employed in the name of the Northern Circars, used to designate a now obsolete division of the Madras presidency, which consisted of a narrow slip of territory lying along the western side of the Bay of Bengal from 15° 40′ to 20° 17′ N. lat. These Northern Circars were five in number, Chicacole, Rajahmundry, Ellore, Kondapalli and Guntur, and their total area was about 30,000 sq. m.

The district corresponds in the main to the modern districts of Kistna, Godavari, Vizagapatam, Ganjam and a part of Nellore. It was first invaded by the Mahommedans in 1471; in 1541 they conquered Kondapalli, and nine years later they extended their conquests over all Guntur and the districts of Masulipatam. But the invaders appear to have acquired only an imperfect possession of the country, as it was again wrested from the Hindu princes of Orissa about the year 1571, during the reign of Ibrahim, of the Kutb Shahi dynasty of Hyderabad or Golconda. In 1687 the Circars were added, along with the empire of Hyderabad, to the extensive empire of Aurangzeb. Salabat Jang, the son of the nizam ul mulk Asaf Jah, who was indebted for his elevation to the throne to the French East India Company, granted them in return for their services the district of Kondavid or Guntur, and soon afterwards the other Circars. In 1759, by the conquest of the fortress of Masulipatam, the dominion of the maritime provinces on both sides, from the river Gundlakamma to the Chilka lake, was necessarily transferred from the French to the British. But the latter left them under the administration of the nizam, with the exception of the town and fortress of Masulipatam, which were retained by the English East India Company. In 1765 Lord Clive obtained from the Mogul emperor Shah Alam a grant of the five Circars. Hereupon the fort of Kondapalli was seized by the British, and on the 12th of November 1766 a treaty of alliance was signed with Nizam Ali by which the Company, in return for the grant of the Circars, undertook to maintain troops for the nizam’s assistance. By a second treaty, signed on the 1st of March 1768, the nizam acknowledged the validity of Shah Alam’s grant and resigned the Circars to the Company, receiving as a mark of friendship an annuity of £50,000. Guntur, as the personal estate of the nizam’s brother Basalat Jang, was excepted during his lifetime under both treaties. He died in 1782, but it was not till 1788 that Guntur came under British administration. Finally, in 1823, the claims of the nizam over the Northern Circars were bought outright by the Company, and they became a British possession.

CIRCASSIA, a name formerly given to the north-western portion of the Caucasus, including the district between the mountain range and the Black Sea, and extending to the north of the central range as far as the river Kuban. Its physical features are described in the article on the Russian province of Kuban, with which it approximately coincides. The present article is confined to a consideration of the ethnographical relations and characteristics of the people, their history being treated under Caucasia.

The Cherkesses or Circassians, who gave their name to this region, of which they were until lately the sole inhabitants, are a peculiar race, differing from the other tribes of the Caucasus in origin and language. They designate themselves by the name of Adigheb, that of Cherkesses being a term of Russian origin. By their long-continued struggles with the power of Russia, during a period of nearly forty years, they attracted the attention of the other nations of Europe in a high degree, and were at the same time an object of interest to the student of the history of civilization, from the strange mixture which their customs exhibited of chivalrous sentiment with savage customs. For this reason it may be still worth while to give a brief summary of their national characteristics and manners, though these must now be regarded as in great measure things of the past.

In the patriarchal simplicity of their manners, the mental qualities with which they were endowed, the beauty of form and regularity of feature by which they were distinguished, they surpassed most of the other tribes of the Caucasus. At the same time they were remarkable for their warlike and intrepid character, their independence, their hospitality to strangers, and that love of country which they manifested in their determined resistance to an almost overwhelming power during the period of a long and desolating war. The government under which they lived was a peculiar form of the feudal system. The free Circassians were divided into three distinct ranks, the princes or pshi, the nobles or uork (Tatar usden), and the peasants or hokotl. Like the inhabitants of the other regions of the Caucasus, they were also divided into numerous families, tribes or clans, some of which were very powerful, and carried on war against each other with great animosity. The slaves, of whom a large proportion were prisoners of war, were generally employed in the cultivation of the soil, or in the domestic service of some of the principal chiefs.

The will of the people was acknowledged as the supreme source of authority; and every free Circassian had a right to express his opinion in those assemblies of his tribe in which the questions of peace and war, almost the only subjects which engaged their attention, were brought under deliberation. The princes and nobles, the leaders of the people in war and their rulers in peace, were only the administrators of a power which was delegated to them. As they had no written laws, the administration of justice was regulated solely by custom and tradition, and in those tribes professing Mahommedanism by the precepts of the Koran. The most aged and respected inhabitants of the various auls or villages frequently sat in judgment, and their decisions were received without a murmur by the contending parties. The Circassian princes and nobles were professedly Mahommedans; but in their religious services many of the ceremonies of their former heathen and Christian worship were still preserved. A great part of the people had remained faithful to the worship of their ancient gods—Shible, the god of thunder, of war and of justice; Tleps, the god of fire; and Seosseres, the god of water and of winds. Although the Circassians are said to have possessed minds capable of the highest cultivation, the arts and sciences, with the exception of poetry and music, were completely neglected. They possessed no written language. The wisdom of their sages, the knowledge they had acquired, and the memory of their warlike deeds were preserved in verses, which were repeated from mouth to mouth and descended from father to son.

The education of the young Circassian was confined to riding, fencing, shooting, hunting, and such exercises as were calculated to strengthen his frame and prepare him for a life of active warfare. The only intellectual duty of the atalik or instructor, with whom the young men lived until they had completed their education, was that of teaching them to express their thoughts shortly, quickly and appropriately. One of their marriage ceremonies was very strange. The young man who had been approved by the parents, and had paid the stipulated price in money, horses, oxen, or sheep for his bride, was expected to come with his friends fully armed, and to carry her off by force from her father’s house. Every free Circassian had unlimited right over the lives of his wife and children. Although polygamy was allowed by the laws of the Koran, the custom of the country forbade it, and the Circassians were generally faithful to the 381 marriage bond. The respect for superior age was carried to such an extent that the young brother used to rise from his seat when the elder entered an apartment, and was silent when he spoke. Like all the other inhabitants of the Caucasus, the Circassians were distinguished for two very opposite qualities—the most generous hospitality and implacable vindictiveness. Hospitality to the stranger was considered one of the most sacred duties. Whatever were his rank in life, all the members of the family rose to receive him on his entrance, and conduct him to the principal seat in the apartment. The host was considered responsible with his own life for the security of his guest, upon whom, even although his deadliest enemy, he would inflict no injury while under the protection of his roof. The chief who had received a stranger was also bound to grant him an escort of horse to conduct him in safety on his journey, and confide him to the protection of those nobles with whom he might be on friendly terms. The law of vengeance was no less binding on the Circassian. The individual who had slain any member of a family was pursued with implacable vengeance by the relatives, until his crime was expiated by death. The murderer might, indeed, secure his safety by the payment of a certain sum of money, or by carrying off from the house of his enemy a newly-born child, bringing it up as his own, and restoring it when its education was finished. In either case, the family of the slain individual might discontinue the pursuit of vengeance without any stain upon its honour. The man closely followed by his enemy, who, on reaching the dwelling of a woman, had merely touched her hand, was safe from all other pursuit so long as he remained under the protection of her roof. The opinions of the Circassians regarding theft resembled those of the ancient Spartans. The commission of the crime was not considered so disgraceful as its discovery; and the punishment of being compelled publicly to restore the stolen property to its original possessor, amid the derision of his tribe, was much dreaded by the Circassian who would glory in a successful theft. The greatest stain upon the Circassian character was the custom of selling their children, the Circassian father being always willing to part with his daughters, many of whom were bought by Turkish merchants for the harems of Eastern monarchs. But no degradation was implied in this transaction, and the young women themselves were generally willing partners in it. Herds of cattle and sheep constituted the chief riches of the inhabitants. The princes and nobles, from whom the members of the various tribes held the land which they cultivated, were the proprietors of the soil. The Circassians carried on little or no commerce, and the state of perpetual warfare in which they lived prevented them from cultivating any of the arts of peace.

CIRCE (Gr. Κίρκη), in Greek legend, a famous sorceress, the daughter of Helios and the ocean nymph Perse. Having murdered her husband, the prince of Colchis, she was expelled by her subjects and placed by her father on the solitary island of Aeaea on the coast of Italy. She was able by means of drugs and incantations to change human beings into the forms of wolves or lions, and with these beings her palace was surrounded. Here she was found by Odysseus and his companions; the latter she changed into swine, but the hero, protected by the herb moly (q.v.), which he had received from Hermes, not only forced her to restore them to their original shape, but also gained her love. For a year he relinquished himself to her endearments, and when he determined to leave, she instructed him how to sail to the land of shades which lay on the verge of the ocean stream, in order to learn his fate from the prophet Teiresias. Upon his return she also gave him directions for avoiding the dangers of the journey home (Homer, Odyssey, x.-xii.; Hyginus, Fab. 125). The Roman poets associated her with the most ancient traditions of Latium, and assigned her a home on the promontory of Circei (Virgil, Aeneid, vii. 10). The metamorphoses of Scylla and of Picus, king of the Ausonians, by Circe, are narrated in Ovid (Metamorphoses, xiv.).

The Myth of Kirke, by R. Brown (1883), in which Circe is explained as a moon-goddess of Babylonian origin, contains an exhaustive summary of facts, although many of the author’s speculations may be proved untenable (review by H. Bradley in Academy, January 19, 1884); see also J.E. Harrison, Myths of the Odyssey (1882); C. Seeliger in W.H. Roscher’s Lexikon der Mythologie.

CIRCEIUS MONS (mod. Monte Circeo), an isolated promontory on the S.W. coast of Italy, about 80 m. S.E. of Rome. It is a ridge of limestone about 3½ m. long by 1 m. wide at the base, running from E. to W. and surrounded by the sea on all sides except the N. The land to the N. of it is 53 ft. above sea-level, while the summit of the promontory is 1775 ft. The origin of the name is uncertain: it has naturally been connected with the legend of Circe, and Victor Bérard (in Les Phéniciens et l’Odyssée, ii. 261 seq.) maintains in support of the identification that Αἰαίη, the Greek name for the island of Circe, is a faithful transliteration of a Semitic name, meaning “island of the hawk,” of which νῆσος Κίρκης is the translation. The difficulty has been raised, especially by geologists, that the promontory ceased to be an island at a period considerably before the time of Homer; but Procopius very truly remarked that the promontory has all the appearance of an island until one is actually upon it. Upon the E. end of the ridge of the promontory are the remains of an enceinte, forming roughly a rectangle of about 200 by 100 yds. of very fine polygonal work, on the outside, the blocks being very carefully cut and jointed and right angles being intentionally avoided. The wall stands almost entirely free, as at Arpinum—polygonal walls in Italy are as a rule embanking walls—and increases considerably in thickness as it descends. The blocks of the inner face are much less carefully worked both here and at Arpinum. It seems to have been an acropolis, and contains no traces of buildings, except for a subterranean cistern, circular, with a beehive roof of converging blocks. The modern village of S. Felice Circeo seems to occupy the site of the ancient town, the citadel of which stood on the mountain top, for its medieval walls rest upon ancient walls of Cyclopean work of less careful construction than those of the citadel, and enclosing an area of 200 by 150 yds.

Circei was founded as a Roman colony at an early date—according to some authorities in the time of Tarquinius Superbus, but more probably about 390 B.C. The existence of a previous population, however, is very likely indicated by the revolt of Circei in the middle of the 4th century B.C., so that it is doubtful whether the walls described are to be attributed to the Romans or the earlier Volscian inhabitants. At the end of the republic, however, or at latest at the beginning of the imperial period, the city of Circei was no longer at the E. end of the promontory, but on the E. shores of the Lago di Paola (a lagoon—now a considerable fishery—separated from the sea by a line of sandhills and connected with it by a channel of Roman date: Strabo speaks of it as a small harbour) one mile N. of the W. end of the promontory. Here are the remains of a Roman town, belonging to the 1st and 2nd centuries, extending over an area of some 600 by 500 yards, and consisting of fine buildings along the lagoons, including a large open piscina or basin, surrounded by a double portico, while farther inland are several very large and well-preserved water-reservoirs, supplied by an aqueduct of which traces may still be seen. An inscription speaks of an amphitheatre, of which no remains are visible. The transference of the city did not, however, mean the abandonment of the E. end of the promontory, on which stand the remains of several very large villas. An inscription, indeed, cut in the rock near S. Felice, speaks of this part of the promunturium Veneris (the only case of the use of this name) as belonging to the city of Circei. On the S. and N. sides of the promontory there are comparatively few buildings, while, at the W. end there is a sheer precipice to the sea. The town only acquired municipal rights after the Social War, and was a place of little importance, except as a seaside resort. For its villas Cicero compares it with Antium, and probably both Tiberius and Domitian possessed residences there. The beetroot and oysters of Circei had a certain reputation. The view from the highest summit of the promontory (which is occupied by ruins of a platform attributed with great probability to a temple of Venus or Circe) is of remarkable beauty; the whole mountain is covered with fragrant 382 shrubs. From any point in the Pomptine Marshes or on the coast-line of Latium the Circeian promontory dominates the landscape in the most remarkable way.

See T. Ashby, “Monte Circeo,” in Mélanges de l’école française de Rome, xxv. (1905) 157 seq.

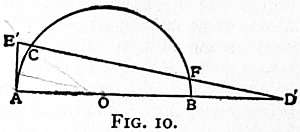

CIRCLE (from the Lat. circulus, the diminutive of circus, a ring; the cognate Gr. word is κιρκος, generally used in the form κρίκος), a plane curve definable as the locus of a point which moves so that its distance from a fixed point is constant.

The form of a circle is familiar to all; and we proceed to define certain lines, points, &c., which constantly occur in studying its geometry. The fixed point in the preceding definition is termed the “centre” (C in fig. 1); the constant distance, e.g. CG, the “radius.” The curve itself is sometimes termed the “circumference.” Any line through the centre and terminated at both extremities by the curve, e.g. AB, is a “diameter”; any other line similarly terminated, e.g. EF, a “chord.” Any line drawn from an external point to cut the circle in two points, e.g. DEF, is termed a “secant”; if it touches the circle, e.g. DG, it is a “tangent.” Any portion of the circumference terminated by two points, e.g. AD (fig. 2), is termed an “arc”; and the plane figure enclosed by a chord and arc, e.g. ABD, is termed a “segment”; if the chord be a diameter, the segment is termed a “semicircle.” The figure included by two radii and an arc is a “sector,” e.g. ECF (fig. 2). “Concentric circles” are, as the name obviously shows, circles having the same centre; the figure enclosed by the circumferences of two concentric circles is an “annulus” (fig. 3), and of two non-concentric circles a “lune,” the shaded portions in fig. 4; the clear figure is sometimes termed a “lens.”

The circle was undoubtedly known to the early civilizations, its simplicity specially recommending it as an object for study. Euclid defines it (Book I. def. 15) as a “plane figure enclosed by one line, all the straight lines drawn to which from one point within the figure are equal to one another.” In the succeeding three definitions the centre, diameter and the semicircle are defined, while the third postulate of the same book demands the possibility of describing a circle for every “centre” and “distance.” Having employed the circle for the construction and demonstration of several propositions in Books I. and II. Euclid devotes his third book entirely to theorems and problems relating to the circle, and certain lines and angles, which he defines in introducing the propositions. The fourth book deals with the circle in its relations to inscribed and circumscribed triangles, quadrilaterals and regular polygons. Reference should be made to the article Geometry: Euclidean, for a detailed summary of the Euclidean treatment, and the elementary properties of the circle.

Analytical Geometry of the Circle.

In the article Geometry: Analytical, it is shown that the general equation to a circle in rectangular Cartesian co-ordinates is x2 + y2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0, i.e. in the general equation of the second degree the co-efficients of x2 and y2 are Cartesian co-ordinates. equal, and of xy zero. The co-ordinates of its centre are -g/c, -f/c; and its radius is (g2 + f2 - c)½. The equations to the chord, tangent and normal are readily derived by the ordinary methods.

Consider the two circles:—

x2 + y2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0, x2 + y2 + 2g′x + 2f′y + c’ = 0.

Obviously these equations show that the curves intersect in four points, two of which lie on the intersection of the line, 2(g - g′)x + 2(f - f′)y + c - c′ = 0, the radical axis, with the circles, and the other two where the lines x² + y² = (x + iy) (x - iy) = 0 (where i = √-1) intersect the circles. The first pair of intersections may be either real or imaginary; we proceed to discuss the second pair.

The equation x² + y² = 0 denotes a pair of perpendicular imaginary lines; it follows, therefore, that circles always intersect in two imaginary points at infinity along these lines, and since the terms x² + y² occur in the equation of every circle, it is seen that all circles pass through two fixed points at infinity. The introduction of these lines and points constitutes a striking achievement in geometry, and from their association with circles they have been named the “circular lines” and “circular points.” Other names for the circular lines are “circulars” or “isotropic lines.” Since the equation to a circle of zero radius is x² + y² = 0, i.e. identical with the circular lines, it follows that this circle consists of a real point and the two imaginary lines; conversely, the circular lines are both a pair of lines and a circle. A further deduction from the principle of continuity follows by considering the intersections of concentric circles. The equations to such circles may be expressed in the form x² + y² = α², x² + y² = β². These equations show that the circles touch where they intersect the lines x² + y² = 0, i.e. concentric circles have double contact at the circular points, the chord of contact being the line at infinity.

In various systems of triangular co-ordinates the equations to circles specially related to the triangle of reference assume comparatively simple forms; consequently they provide elegant algebraical demonstrations of properties concerning a triangle and the circles intimately associated with its geometry. In this article the equations to the more important circles—the circumscribed, inscribed, escribed, self-conjugate—will be given; reference should be made to the article Triangle for the consideration of other circles (nine-point, Brocard, Lemoine, &c.); while in the article Geometry: Analytical, the principles of the different systems are discussed.

The equation to the circumcircle assumes the simple form aβγ + bγα + cαβ = 0, the centre being cos A, cos B, cos C. The inscribed circle is cos ½A √(α) cos ½B √(β) + cos ½C √(γ) = 0, with centre α = β = γ; while the escribed circle opposite the angle A Trilinear co-ordinates. is cos ½A √(-α) + sin ½B √(β) + sin ½C √(γ) = 0, with centre -α = β = γ. The self-conjugate circle is α² sin 2A + β² sin 2B + γ² sin 2C = 0, or the equivalent form a cosA α² + b cos B β² + c cos C γ² = 0, the centre being sec A, sec B, sec C.

The general equation to the circle in trilinear co-ordinates is readily deduced from the fact that the circle is the only curve which intersects the line infinity in the circular points. Consider the equation

aβγ + bγα + Cαβ + (lα + mβ + nγ) (aα + bβ + cγ) = 0 (1).

This obviously represents a conic intersecting the circle aβγ + bγα + cαβ = 0 in points on the common chords lα + mβ + nγ = 0, aα + bβ + cγ = 0. The line lα + mβ + nγ is the radical axis, and since aα + bβ + cγ = 0 is the line infinity, it is obvious that equation (1) represents a conic passing through the circular points, i.e. a circle. If we compare (1) with the general equation of the second degree uα² + vβ² + wγ² + 2u′βγ + 2v′γα + 2w′αβ = 0, it is readily seen that for this equation to represent a circle we must have

-kabc = vc² + wb² - 2u′bc = wa² + uc² - 2v′ca = ub² + va² - 2w′ab.

The corresponding equations in areal co-ordinates are readily derived by substituting x/a, y/b, z/c for α, β, γ respectively in the trilinear equations. The circumcircle is thus seen Areal co-ordinates. to be a²yz + b²zx + c²xy = 0, with centre sin 2A, sin 2B, sin 2C; the inscribed circle is √(x cot ½A) + √(y cot ½B) + √(z cot ½C) = 0, with centre sin A, sin B, sin C; the escribed circle opposite the angle A is √(-x cot ½A) + √(y tan ½B) + √(z tan ½C)=0, with centre - sin A, sin B, sin C; and the self-conjugate circle is x² cot A + y² cot B + z² cot C = 0, with centre tan A, tan B, tan C. Since in areal co-ordinates the line infinity is represented by the equation x + y + z = 0 it is seen that every circle is of the form a²yz + b²zx + c²xy + (lx + my + nz)(x + y + z) = 0. Comparing this equation with ux² + vy² + wz² + 2u′yz + 2v′zx + 2w′xy = 0, we obtain as the condition for the general equation of the second degree to represent a circle:—

(v + w - 2u′)/a² = (w + u - 2v′)/b² = (u + v - 2w′)/c².