The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Books of Chilan Balam, the Prophetic and Historic Records of the Mayas of Yuc, by Daniel G. Brinton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Books of Chilan Balam, the Prophetic and Historic Records of the Mayas of Yucatan Author: Daniel G. Brinton Release Date: March 12, 2010 [EBook #31610] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOOKS OF CHILAN BALAM *** Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

A number of typographical errors have been maintained in this version of this book. They are marked and the corrected text is shown in the popup. A description of the errors is found in the list at the end of the text.

By Daniel G. Brinton, M. D.

VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE NUMISMATIC AND ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY OF

PHILADELPHIA; MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL

SOCIETY; THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY;

DÉLÉGUÉ OF THE INSTITUTION

ETHNOGRAPHIQUE,

ETC., ETC.

EDWARD STERN & CO.,

PHILADELPHIA.

The substance of the present pamphlet was presented as an address to the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia, at its meeting in January, 1882, and was printed in the Penn Monthly, March, 1882. As the subject is one quite new in the field of American archæology and linguistics, it is believed that a republication in the present form will be welcomed by students of these branches.

Civilization in ancient America rose to its highest level among the Mayas of Yucatan. Not to speak of the architectural monuments which still remain to attest this, we have the evidence of the earliest missionaries to the fact that they alone, of all the natives of the New World, possessed a literature written in “letters and characters,” preserved in volumes neatly bound, the paper manufactured from the bark of a tree and sized with a durable white varnish.5-†

A few of these books still remain, preserved to us by accident in the great European libraries; but most of them were destroyed by the monks. Their contents were found to relate chiefly to the pagan ritual, to traditions of the heathen times, to astrological superstitions, and the like. Hence, they were considered deleterious, and were burned wherever discovered.

This annihilation of their sacred books affected the natives most keenly, as we are pointedly informed by Bishop Landa, himself one of the most ruthless of Vandals in this respect.5-‡ But already [6]some of the more intelligent had learned the Spanish alphabet, and the missionaries had added a sufficient number of signs to it to express with tolerable accuracy the phonetics of the Maya tongue. Relying on their memories, and, no doubt, aided by some manuscripts secretly preserved, many natives set to work to write out in this new alphabet the contents of their ancient records. Much was added which had been brought in by the Europeans, and much omitted which had become unintelligible or obsolete since the Conquest; while, of course, the different writers, varying in skill and knowledge, produced works of very various merit.

Nevertheless, each of these books bore the same name. In whatever village it was written, or by whatever hand, it always was, and to-day still is, called “The Book of Chilan Balam.” To distinguish them apart, the name of the village where a copy was found or written, is added. Probably, in the last century, almost every village had one, which was treasured with superstitious veneration. But the opposition of the padres to this kind of literature, the decay of ancient sympathies, and especially the long war of races, which since 1847 has desolated so much of the peninsula, have destroyed most of them. There remain, however, either portions or descriptions of not less than sixteen of these curious records. They are known from the names of the villages respectively as the Book of Chilan Balam of Nabula, of Chumayel, of Káua, of Mani, of Oxkutzcab, of Ixil, of Tihosuco, of Tixcocob, etc., these being the names of various native towns in the peninsula.

When I add that not a single one of these has ever been printed, or even entirely translated into any European tongue, it will be evident to every archæologist and linguist what a rich and unexplored mine of information about this interesting people they may present. It is my intention in this article merely to touch upon a few salient points to illustrate this, leaving a thorough discussion of their origin and contents to the future editor who will bring them to the knowledge of the learned world.

Turning first to the meaning of the name “Chilan Balam,” it is not difficult to find its derivation. “Chilan,” says Bishop Landa, the second bishop of Yucatan, whose description of the native customs is an invaluable source to us, “was the name of their priests, whose duty it was to teach the sciences, to appoint holy days, to treat the sick, to offer sacrifices, and especially to[7] utter the oracles of the gods. They were so highly honored by the people that usually they were carried on litters on the shoulders of the devotees.”7-* Strictly speaking, in Maya “chilan” means “interpreter,” “mouth-piece,” from “chij,” “the mouth,” and in this ordinary sense frequently occurs in other writings. The word, “balam”—literally, “tiger,”—was also applied to a class of priests, and is still in use among the natives of Yucatan as the designation of the protective spirits of fields and towns, as I have shown at length in a recent study of the word as it occurs in the the native myths of Guatemala.7-† “Chilan Balam,” therefore, is not a proper name, but a title, and in ancient times designated the priest who announced the will of the gods and explained the sacred oracles. This accounts for the universality of the name and the sacredness of its associations.

The dates of the books which have come down to us are various. One of them, “The Book of Chilan Balam of Mani,” was undoubtedly composed not later than 1595, as is proved by internal evidence. Various passages in the works of Landa, Lizana, Sanchez Aguilar and Cogolludo—all early historians of Yucatan,—prove that many of these native manuscripts existed in the sixteenth century. Several rescripts date from the seventeenth century,—most from the latter half of the eighteenth.

The names of the writers are generally not given, probably because the books, as we have them, are all copies of older manuscripts, with merely the occasional addition of current items of note by the copyist; as, for instance, a malignant epidemic which prevailed in the peninsula in 1673 is mentioned as a present occurrence by the copyist of “The Book of Chilan Balam of Nabula.”

[8]I come now to the contents of these curious works. What they contain may conveniently be classified under four headings:

Astrological and prophetic matters;

Ancient chronology and history;

Medical recipes and directions;

Later history and Christian teachings.

The last-mentioned consist of translations of the “Doctrina,” Bible stories, narratives of events after the Conquest, etc., which I shall dismiss as of least interest.

The astrology appears partly to be reminiscences of that of their ancient heathendom, partly that borrowed from the European almanacs of the century 1550-1650. These, as is well known, were crammed with predictions and divinations. A careful analysis, based on a comparison with the Spanish almanacs of that time would doubtless reveal how much was taken from them, and it would be fair to presume that the remainder was a survival of ancient native theories.

But there are not wanting actual prophecies of a much more striking character. These were attributed to the ancient priests and to a date long preceding the advent of Christianity. Some of them have been printed in translations in the “Historias” of Lizana and Cogolludo, and of some the originals were published by the late Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, in the second volume of the reports of the “Mission Scientifique au Mexique et dans l’Amérique Centrale.” Their authenticity has been met with considerable skepticism by Waitz and others, particularly as they seem to predict the arrival of the Christians from the East and the introduction of the worship of the cross.

It appears to me that this incredulity is uncalled for. It is known that at the close of each of their larger divisions of time (the so-called “katuns,”) a “chilan,” or inspired diviner, uttered a prediction of the character of the year or epoch which was about to begin. Like other would-be prophets, he had doubtless learned that it is wiser to predict evil than good, inasmuch as the probabilities of evil in this worried world of ours outweigh those of good; and when the evil comes his words are remembered to his credit, while, if, perchance, his gloomy forecasts are not realized, no one will bear him a grudge that he has been at fault. The temper of this people was, moreover, gloomy, and it suited them to hear of threatened danger[9] and destruction by foreign foes. But, alas! for them. The worst that the boding words of the oracle foretold was as nothing to the dire event which overtook them,—the destruction of their nation, their temples and their freedom, ’neath the iron heel of the Spanish conqueror. As the wise Goethe says:

“Seltsam ist Prophetenlied,

Doch mehr seltsam was geschieht.”

As to the supposed reference to the cross and its worship, it may be remarked that the native word translated “cross,” by the missionaries, simply means “a piece of wood set upright,” and may well have had a different and special signification in the old days.

By way of a specimen of these prophecies, I quote one from “The Book of Chilan Balam of Chumayel,” saying at once that for the translation I have depended upon a comparison of the Spanish version of Lizana, who was blindly prejudiced, and that in French of the Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg, who knew next to nothing about Maya, with the original. It will be easily understood, therefore, that it is rather a paraphrase than a literal rendering. The original is in short, aphoristic sentences, and was, no doubt, chanted with a rude rhythm:

“What time the sun shall brightest shine,

Tearful will be the eyes of the king.

Four ages yet shall be inscribed,

Then shall come the holy priest, the holy god.

With grief I speak what now I see.

Watch well the road, ye dwellers in Itza.

The master of the earth shall come to us.

Thus prophesies Nahau Pech, the seer,

In the days of the fourth age,

At the time of its beginning.”

Such are the obscure and ominous words of the ancient oracle. If the date is authentic, it would be about 1480—the “fourth age” in the Maya system of computing time being a period of either twenty or twenty-four years at the close of the fifteenth century.

It is, however, of little importance whether these are accurate copies of the ancient prophecies; they remain, at least, faithful imitations of them, composed in the same spirit and form which the native priests were wont to employ. A number are given much longer than the above, and containing various curious references to ancient usages.

[10]Another value they have in common with all the rest of the text of these books, and it is one which will be properly appreciated by any student of languages. They are, by common consent of all competent authorities, the genuine productions of native minds, cast in the idiomatic forms of the native tongue by those born to its use. No matter how fluent a foreigner becomes in a language not his own, he can never use it as does one who has been familiar with it from childhood. This general maxim is ten-fold true when we apply it to a European learning an American language. The flow of thought, as exhibited in these two linguistic families, is in such different directions that no amount of practice can render one equally accurate in both. Hence the importance of studying a tongue as it is employed by natives; and hence the very high estimate I place on these “Books of Chilan Balam” as linguistic material,—an estimate much increased by the great rarity of independent compositions in their own tongues by members of the native races of this continent.

I now approach what I consider the peculiar value of these records, apart from the linguistic mould in which they are cast; and that is the light they throw upon the chronological system and ancient history of the Mayas. To a limited extent, this has already been brought before the public. The late Don Pio Perez gave to Mr. Stephens, when in Yucatan, an essay on the method of computing time among the ancient Mayas, and also a brief synopsis of Maya history, apparently going back to the third or fourth century of the Christian era. Both were published by Mr. Stephens in the appendix to his “Travels in Yucatan,” and have appeared repeatedly since in English, Spanish and French.10-* They have, up to the present, constituted almost our sole sources of information on these interesting points. Don Pio Perez was rather vague as to whence he derived his knowledge. He refers to “ancient manuscripts,” “old authorities,” and the like; but, as the Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg justly complains, he rarely quotes their words,[11] and gives no descriptions as to what they were or how he gained access to them.11-* In fact, the whole of Señor Perez’s information was derived from these “Books of Chilan Balam;” and, without wishing at all to detract from his reputation as an antiquary and a Maya scholar, I am obliged to say that he has dealt with them as scholars so often do with their authorities; that is, having framed his theories, he quoted what he found in their favor and neglected to refer to what he observed was against them.

Thus, it is a cardinal question in Yucatecan archæology as to whether the epoch or age by which the great cycle (the ahau katun,) was reckoned, embraced twenty or twenty-four years. Contrary to all the Spanish authorities, Perez declared for twenty-four years, supporting himself by “the manuscripts.” It is true there are three of the “Books of Chilan Balam”—those of Mani, Káua and Oxkutzcab,—which are distinctly in favor of twenty-four years; but, on the other hand, there are four or five others which are clearly for the period of twenty years, and of these Don Perez said nothing, although copies of more than one of them were in his library. So of the epochs, or katuns, of Maya history; there are three or more copies in these books which he does not seem to have compared with the one he furnished Stephens. His labor will have to be repeated according to the methods of modern criticism, and with the additional material obtained since he wrote.

Another valuable feature in these records is the hints they furnish of the hieroglyphic system of the Mayas. Almost our only authority heretofore has been the essay of Landa. It has suffered somewhat in credit because we had no means of verifying his statements and comparing the characters he gives. Dr. Valentini has even gone so far as to attack some of his assertions as “fabrications.” This is an amount of skepticism which exceeds both justice and probability.

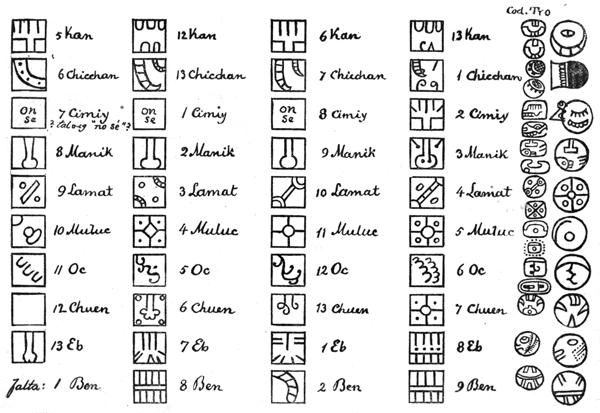

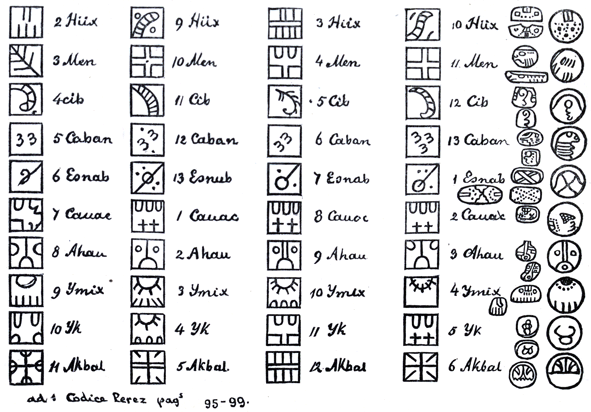

The chronological portions of the “Books of Chilan Balam” re partly written with the ancient signs of the days, months and epochs, and they furnish us, also, delineations of the “wheels” which the natives used for computing time. The former are so important to the student of Maya hieroglyphics, that I have added photographic reproductions of them to this paper, giving also representations of[14][13][12] those of Landa for comparison. It will be observed that the signs of the days are distinctly similar in the majority of cases, but that those of the months are hardly alike.

The hieroglyphs of the days taken from the “Codex Troano,” an ancient Maya book written before the Conquest, probably about 1400, are also added to illustrate the variations which occurred in the hands of different scribes. Those from the “Books of Chilan Balam” are copied from a manuscript known to Maya scholars as the “Codice Perez,” of undoubted authenticity and antiquity.14-*

The result of the comparison I thus institute is a triumphant refutation of the doubts and slurs which have been cast on Bishop Landa’s work and vindicate for it a very high degree of accuracy.

The hieroglyphics for the months are quite complicated, and in the “Books of Chilan Balam” are rudely drawn; but, for all that, two or three of them are evidently identical with those in the calendar preserved by Landa. Some years ago, Professor de Rosny expressed himself in great doubt as to the fidelity in the tracing of these hierogylphs of the months, principally because he could not find them in the two codices at his command.14-† As he observes, they are composite signs, and this goes to explain the discrepancy; for it may be regarded as established that the Maya script permitted the use of several signs for the same sound, and the sculptor or scribe was not obliged to represent the same word always by the same figure.

In close relation to chronology is the system of numeration and the arithmetical signs. These are discussed with considerable fulness, especially in the “Book of Chilan Balam of Káua.” The numerals are represented by exactly the same figures as we find in the Maya manuscripts of the libraries of Dresden, Pesth, Paris and Madrid; that is, by points or dots up to five, and the fives by single straight lines, which may be indiscriminately drawn vertically or horizontally. The same book contains a table of multiplication in[15] Spanish and Maya which settles some disputed points in the use of the vigesimal system by the Mayas.

A curious chapter in several of the books, especially those of Káua and Mani, is that on the thirteen ahau katuns, or epochs of the greater cycle of the Mayas. This cycle embraced thirteen periods, which, as I have before remarked, are computed by some at twenty years each, by others at twenty-four years each. Each of these katuns was presided over by a chief or king, that being the meaning of the word ahau. The books above-mentioned give both the name and the portrait, drawn and colored by the rude hand of the native artist, of each of these kings, and they suggest several interesting analogies.

They are, in the first place, identical, with one exception, with those on an ancient native painting, an engraving of which is given by Father Cogolludo in his “History of Yucatan,” and explained by him as the representation of an occurrence which took place after the Spaniards arrived in the peninsula. Evidently, the native in whose hands the worthy father found it, fearing that he partook of the fanaticism which had led the missionaries to the destruction of so many records of the nation, deceived him as to its purport, and gave him an explanation which imported to the scroll the character of a harmless history.

The one exception is the last or thirteenth chief. Cogolludo appends to this the name of an Indian who probably did fall a victim to his friendship to the Spaniards. This name, as a sort of guarantee for the rest of his story, the native scribe inserted in place of the genuine one. The peculiarity of the figure is that it has an arrow or dagger driven into its eye. Not only is this mentioned by Cogolludo’s informant, but it is represented in the paintings in both the “Books of Chilan Balam” above noted, and also, by a fortunate coincidence, in one of the calendar-pages of the “Codex Troano,” plate xxiii., in a remarkable cartouche, which, from a wholly independent course of reasoning, was some time since identified by my esteemed correspondent, Professor Cyrus Thomas, of Illinois, as a cartouche of one of the ahau katuns, and probably of the last of them. It gives me much pleasure to add such conclusive proof of the sagacity of his supposition.15-*

SIGNS OF THE DAYS.

The first column on the right is from Landa. The second is from the

“Codex Troano.” The remaining four are from the Book of Chilan Balam

of Káua.

SIGNS OF THE DAYS.

The first column on the right is from Landa. The second is from the

“Codex Troano.” The remaining four are from the Book of Chilan Balam

of Káua.

[18]There is other evidence to show that the engraving in Cogolludo is a relic of the purest ancient Maya symbolism,—one of the most interesting which have been preserved to us; but to enter upon its explanation in this connection would be too far from my present topic.

A favorite theme with the writers of the “Books of Chilan Balam” was the cure of diseases. Bishop Landa explains the “chilanes” as “sorcerers and doctors,” and adds that one of their prominent duties was to diagnose diseases and point out their appropriate remedies.18-* As we might expect, therefore, considerable prominence is given to the description of symptoms and suggestions for their alleviation. Bleeding and the administration of preparations of native plants are the usual prescriptions; but there are others which have probably been borrowed from some domestic medicine-book of European origin.

The late Don Pio Perez gave a great deal of attention to collecting these native recipes, and his manuscripts were carefully examined by Dr. Berendt, who combined all the necessary knowledge, botanical, linguistic and medical, and who has left a large manuscript, entitled “Recetarios de Indios,” which presents the subject fully. He considers the scientific value of these remedies to be next to nothing, and the language in which they are recorded to be distinctly inferior to that of the remainder of the “Books of Chilan Balam.” Hence, he believes that this portion of the ancient records was supplanted some time in the last century by medical notions introduced from European sources. Such, in fact, is the statement of the copyists of the books themselves, as these recipes, etc., are sometimes found in a separate volume, entitled “The Book of the Jew,”—“El Libro del Judio.” Who this alleged Jewish physician was, who left so wide-spread and durable a renown among the Yucatecan natives, none of the archæologists has been able to find out.18-†

The language and style of most of these books are aphoristic,[19] elliptical and obscure. The Maya language has naturally undergone considerable alteration since they were written; therefore, even to competent readers of ordinary Maya, they are not readily understood. Fortunately, however, there are in existence excellent dictionaries of the Maya of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which, were they published, would be sufficient for this purpose.

A few persons in Yucatan have appreciated the desirability of collecting and preserving these works. Don Pio Perez was the first to do so, and of living Yucatecan scholars particular mention should be made of the Rev. Canon Don Crescencio Carrillo y An cona, who has written a good, and I believe the only, description of them which has yet appeared in print.19-* They attracted the earnest attention of that eminent naturalist and ethnologist, the late Dr. C. Hermann Berendt, and at a great expenditure of time and labor he visited various parts of Yucatan, and with remarkable skill made fac-simile copies of the most important and complete specimens which he could anywhere find. This invaluable and unique collection has come into my hands since his death, and it is this which has prompted me to make known their character and contents to those interested in such subjects.

5-* Read before the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia, at its twenty-fourth annual meeting, January 5th, 1882.

5-† Of the numerous authorities which could be quoted on this point, I shall give the words of but one, Father Alonso Ponce, the Pope’s Commissary-General, who travelled through Yucatan in 1586, when many natives were still living who had been born before the Conquest (1541). Father Ponce had travelled through Mexico, and, of course, had learned about the Aztec picture-writing, which he distinctly contrasts with the writing of the Mayas. Of the latter, he says: “Son alabados de tres cosas entre todos los demas de la Nueva España, la una de que en su antiguedad tenian caracteres y letras, con que escribian sus historias y las ceremonias y orden de los sacrificios de sus idolos y su calendario, en libros hechos de corteza de cierto arbol, los cuales eran unas tiras muy largas de quarta ó tercia en ancho, que se doblaban y recogian, y venia á queder á manera de un libro encuardenada en cuartilla, poco mas ó menos. Estas letras y caracteres no las entendian, sino los sacerdotes de los idolos, (que en aquella lengua se llaman ‘ahkines,’) y algun indio principal. Despues las entendieron y supieron léer algunos frailos nuestros y aun las escribien.”—(“Relacion Breve y Verdadera de Algunas Cosas de las Muchas que Sucedieron al Padre Fray Alonso Ponce, Comisario-General en las Provincias de la Nueva España,” page 392). I know no other author who makes the interesting statement that these characters were actually used by the missionaries to impart instruction to the natives; but I learn through Mr. Gatschet, of the Bureau of Ethnology, Washington, that a manuscript written in this manner by one of the early padres has recently been discovered.

5-‡ “Se les quemamos todos,” he writes, “lo qual á maravilla sentian y les dava pena.”—“Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan,” page 316.

7-* “Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan,” page 160.

7-† “The Names of the Gods in the Kiche Myths of Central America.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. XIX., 1881. The terminal letter in both these words—“chilan,” “balam,”—may be either “n” or “m,” the change being one of dialect and local pronunciation. I have followed the older authorities in writing “Chilan Balam,” the modern preferring “Chilam Balam.” Señor Eligio Ancona, in his recently published “Historia de Yucatan,” (Vol. I., page 240, note, Merida, 1878,) offers the absurd suggestion that the name “balam” was given to the native soothsayers by the early missionaries in ridicule, deriving it from the well-known personage in the Old Testament. It is surprising that Señor Ancona, writing in Merida, had never acquainted himself with the Perez manuscripts, nor with those in the possession of Canon Carrillo. Indeed, the most of his treatment of the ancient history of his country is disappointingly superficial.

10-* For example, in the “Registro Yucateco,” Tome III.; “Diccionario Universal de Historia y Geografia,” Tome VIII. (Mexico, 1855); “Diccionario Historico de Yucatan,” Tome I. (Merida, 1866); in the appendix to Landa’s “Cosas de Yucatan” (Paris, 1864), etc. The epochs, or katuns, of Maya history have been recently again analyzed by Dr. Felipe Valentini, in an essay in the German and English languages, the latter in the “Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1880.”

11-* The Abbé’s criticism occurs in the note to page 406 of his edition of Landa’s “Cosas de Yucatan.”

14-* It is described at length by Don Crescencio Carrillo y Ancona, in his “Disertacion sobre la Historia de la Lengua Maya” (Merida, 1870).

14-† “Je dois déclarer que l’examen dans tous leurs détails du ‘Codex Troano’ et du ‘Codex Peresianus’ m’invite de la façon la plus sérieuse à n’accepter ces signes, tout au moins au point de vue de l’exactitude de leur tracé, qu’avec une certaine réserve.”—Leon de Rosny’s “Essai sur le Déchiffrement de l’Ecriture Hiératique de l’Amérique Centrale,” page 21 (Paris, 1876). By the “Codex Peresianus,” he does not mean the “Codice Perez,” but the Maya manuscript in the Bibliothêque Nationale. The identity of the names is confusing and unfortunate.

15-* “The Manuscript Troano,” published in The American Naturalist, August, 1881, page 640. This manuscript or codex was published in chromo-lithograph, Paris, 1879, by the French Government.

18-* “Declarar las necesidades y sus remedios.”—“Relation de las Cosas de Yucatan,” page 160. Like much of Landa’s Spanish, this use of the word “necesidad” is colloquial, and not classical.

18-† A “Medicina Domestica,” under the name of “Don Ricardo Ossado, (alias, el Judio,)” was published at Merida in 1834; but this appears to have been merely a bookseller’s device to aid the sale of the book by attributing it to the “great unknown.”

19-* In his “Disertacion sobre la Historia de la Lengua Maya ó Yucateca” (Merida, 1870).

The following errors have been maintained.

| Page | Error | Correction |

| 11 | re | are |

| 13 | hierogylphs | hieroglyphs |

| 19 | An cona | Ancona |

| fn. 14-† | Bibliothêque | Bibliothèque |

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Books of Chilan Balam, the

Prophetic and Historic Records, by Daniel G. Brinton

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOOKS OF CHILAN BALAM ***

***** This file should be named 31610-h.htm or 31610-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/3/1/6/1/31610/

Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.