THE PYRAMIDS.

THE PYRAMIDS.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 1, No. 2, July, 1850., by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Volume 1, No. 2, July, 1850. Author: Various Release Date: February 5, 2010 [EBook #31187] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY, JULY 1850 *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

Transcriber's Note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of contents has been created for the HTML version.

THOMAS DE QUINCEY.

THE MINER'S DAUGHTERS—A TALE OF THE PEAK.

MOORISH DOMESTIC LIFE.

THE RAILWAY STATION.

THE SICK MAN'S PRAYER

SOPHISTRY OF ANGLERS.—IZAAK WALTON.

GLOBES, AND HOW THEY ARE MADE.

LETTICE ARNOLD.

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION.

FIFTY YEARS AGO.

A PARIS NEWSPAPER.

ON THE DEATH OF AN INFANT.

RECOLLECTIONS OF EMINENT MEN.

ODE TO THE SUN.

TWO-HANDED DICK THE STOCKMAN.

THE USES OF SORROW.

BENJAMIN WEST.

PEACE.

ALCHEMY AND GUNPOWDER.

GLIMPSES OF THE EAST.

CHRIST-HOSPITAL WORTHIES.

LEIGH HUNT DROWNING.

WILLIAM PITT.

IGNORANCE OF THE ENGLISH.

LINES BY ROBERT SOUTHEY.

THE SCHOOLMASTER OF COLERIDGE AND LAMB.

EDUCATION IN AMERICA

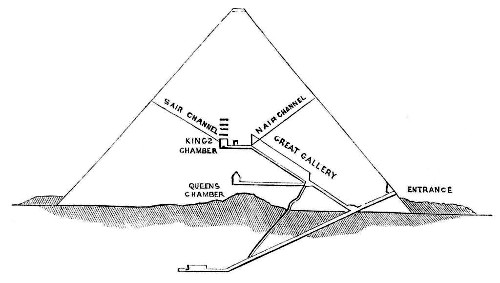

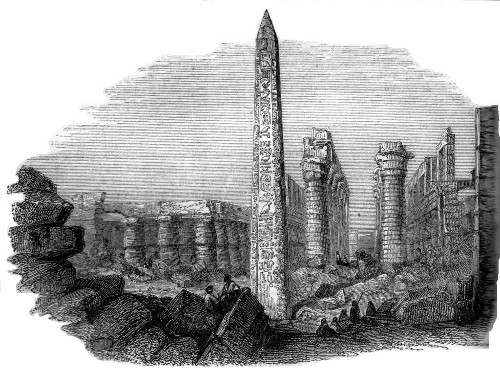

SCENES IN EGYPT.

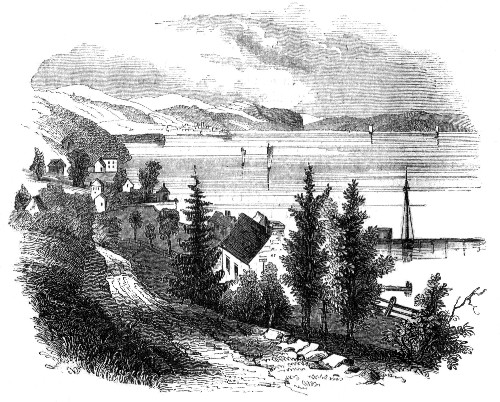

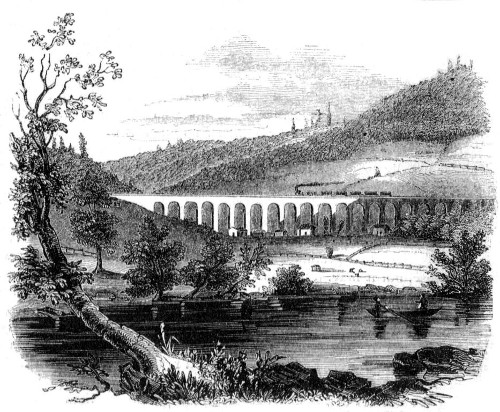

SCENERY ON THE ERIE RAILROAD.

BATHING—ITS UTILITY.

POVERTY OF THE ENGLISH BAR.

SONNET ON THE DEATH OF WORDSWORTH.

MAURICE TIERNAY,

THE PLANET-WATCHERS OF GREENWICH.

RAPID GROWTH OF AMERICA.

LORD COKE AND LORD BACON.

FATHER AND SON.

DIPLOMACY—LORD CHESTERFIELD.

THOMAS MOORE.

THE APPETITE FOR NEWS.

A FEW WORDS ON CORALS.

A NIGHT IN THE BELL INN.

DEATH OF CROMWELL.

MY WONDERFUL ADVENTURES IN SKITZLAND.

CHARLOTTE CORDAY.

GREENWICH WEATHER-WISDOM.

DOING.

YOUNG RUSSIA.

THE ORPHAN'S VOYAGE HOME.

LORD BYRON, WORDSWORTH, AND CHARLES LAMB.

AMERICAN VANITY.

MONTHLY RECORD OF CURRENT EVENTS.

LITERARY NOTICES.

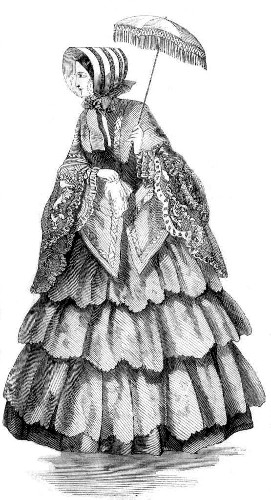

SUMMER FASHIONS.

When "Gilfillan's Gallery" first appeared, a copy of it was sent to an eminent lay-divine, the first sentence of whose reply was, "You have sent me a list of shipwrecks." It was but too true, for that "Gallery" contains the name of a Godwin, shipwrecked on a false system, and a Shelley, shipwrecked on an extravagant version of that false system—and a Hazlitt, shipwrecked on no system at all—and a Hall, driven upon the rugged reef of madness—and a Foster, cast high and dry upon the dark shore of Misanthropy—and an Edward Irving, inflated into sublime idiocy by the breath of popular favor, and in the subsidence of that breath, left to roll at the mercy of the waves, a mere log—and lastly, a Coleridge and a De Quincy, stranded on the same poppy-covered coast, the land of the "Lotos-eaters," where it is never morning, nor midnight, nor full day, but always afternoon.

Wrecks all these are, but all splendid and instructive withal. And we propose now—repairing to the shore, where the last great argosy, Thomas De Quincey, lies half bedded in mud—to pick up whatever of noble and rare, of pure and permanent, we can find floating around. We would speak of De Quincey's history, of his faults, of his genius, of his works, and of his future place in the history of literature. And when we reflect on what a mare magnum we are about to show to many of our readers, we feel for the moment as if it were new to us also, as if we stood—

We can not construct a regular biography of this remarkable man; neither the time for this has come, nor have the materials been, as yet, placed within reach of us, or of any one else. But we may sketch the outlines of what we know, which is indeed but little.

Thomas De Quincey is the son of a Liverpool merchant. He is one of several children, the premature loss of one of whom he has, in his "Suspiria de Profundis" (published in "Blackwood") most plaintively and eloquently deplored. His father seems to have died early. Guardians were appointed over him, with whom he contrived to quarrel, and from whose wing (while studying at Oxford) he fled to London. There he underwent a series of surprising adventures and severe sufferings, which he has recounted in the first part of his "Opium Confessions." On one occasion, while on the point of death by starvation, his life was saved by the intervention of a poor street-stroller, of whom he afterward lost sight, but whom, in the strong gratitude of his heart, he would pursue into the central darkness of a London brothel, or into the deeper darkness of the grave. Part of the same dark period of his life was spent in Wales, where he subsisted now on the hospitality of the country people, and now, poor fellow, on hips and haws. He was at last found out by some of his friends, and remanded to Oxford. There he formed a friendship with Christopher North, which has continued unimpaired to this hour. Both—besides the band of kindred genius—had that of profound admiration, then a rare feeling, for the poetry of Wordsworth. In the course of this part of his life he visited Ireland, and was introduced soon afterward to OPIUM—fatal friend, treacherous ally—root of that tree called Wormwood, which has overshadowed all his after life. A blank here occurs in his history. We find him next in a small white cottage in Cumberland—married—studying Kant, drinking laudanum, and dreaming the most wild and wondrous dreams which ever crossed the brain of mortal. These dreams he recorded in the "London Magazine," then a powerful periodical, conducted by John Scott, and supported by such men as Hazlitt, Reynolds, and Allan Cunningham. The "Confessions," when published separately, ran like wildfire, although from their anonymous form they added nothing at the time to the author's fame. Not long after their publication, Mr. De Quincey came down to Scotland, where he has continued to reside, wandering from place to place, contributing to periodicals of all sorts and sizes—to "Blackwood," "Tait," "North British Review," "Hogg's Weekly Instructor," as well as writing for the "Encyclopædia Britannica," and publishing one or two independent works, such as "Klosterheim," a tale, and the "Logic of Political Economy." His wife has been long dead. Three of his daughters, amiable and excellent persons, live in the sweet village of Lasswade, in the neighborhood of Edinburgh; and there he is, we believe, at present himself.

From his very imperfect sketch of De Quincey's[Pg 146] history, there rush into our minds some rather painful reflections. It is painful to see a

It is painful to see a glorious being transfigured into a rolling thing before the whirlwind. It is painful to be compelled to inscribe upon such a shield the word "Desdichado." It is painful to remember how much misery must have passed through that heart, and how many sweat drops of agony must have stood, in desolate state, upon that brow. And it is most painful of all to feel that guilt, as well as misery, has been here, and that the sowing of the wind preceded the reaping of the whirlwind.

Such reflections were mere sentimentalism, unless attended by such corollaries as these: 1st. Self-control ought to be more than at present a part of education, sedulously and sternly taught, for is it not the geometry of life? 2dly. Society should feel more that she is responsible for the wayward children of genius, and ought to seek more than she does to soothe their sorrows, to relieve their wants, to reclaim their wanderings, and to search, as with lighted candles, into the causes of their incommunicable misery. Had the public, twenty years ago, feeling Mr. De Quincey to be one of the master spirits of the age, and, therefore, potentially, one of its greatest benefactors, inquired deliberately into his case, sought him out, put him beyond the reach of want, encouraged thus his heart, and strengthened his hand, rescued him from the mean miseries into which he was plunged, smiled approvingly upon the struggles he was making to conquer an evil habit—in one word, recognized him, what a different man had he been now, and over what magnificent wholes had we been rejoicing, in the shape of his works, instead of deploring powers and acquirements thrown away, in rearing towers of Babel, tantalizing in proportion to the magnitude of their design, and the beauty of their execution. Neglected and left alone as a corpse in the shroud of his own genius, a fugitive, though not a vagabond, compelled day after day to fight absolute starvation at the point of his pen, the marvel is, that he has written so much which the world may not willingly let die. But, it is the world's fault that the writings it now recognizes, and may henceforth preserve on a high shelf, are rather the sublime ravings of De Quincey drunk, than the calm, profound cogitations of De Quincey sober. The theory of capital punishments is much more subtle and widely ramified than we might at first suppose. On what else are many of our summary critical and moral judgments founded? Men find a man guilty of a crime—they vote him for that one act a purely pernicious member of society, and they turn him off. So a Byron quarrels with his wife—a Coleridge loses his balance, and begins to reel and totter like Etna in an earthquake—a Burns, made an exciseman, gradually descends toward the low level of his trade—or a De Quincey takes to living on laudanum, and the public, instead of seeking to reform and re-edify each brilliant begun ruin, shouts out, "Raze, raze it to its foundation." Because the sun is eclipsed, they would howl him away! Because one blot has lighted on an imperishable page, they would burn it up! Let us hope, that as our age is fast becoming ashamed of those infernal sacrifices called executions, so it shall also soon forbear to make its most gifted sons pass through the fire to Moloch, till it has tested their thorough and ineradicable vileness.

Mr. De Quincey's faults we have spoken of in the plural—we ought, perhaps, rather to have used the singular number. In the one word excitement, assuming the special form of opium—the "insane root"—lies the gravamen of his guilt, as, also, of Coleridge's. Now, we are far from wishing to underrate the evil of this craving. But we ought to estimate Mr. De Quincey's criminality with precision and justice; and, while granting that he used opium to excess—an excess seldom paralleled—we must take his own explanation of the circumstances which led him to begin its use, and of the effects it produced on him. He did not begin it to multiply or intensify his pleasures, still less to lash himself with its fiery thongs into a counterfeit inspiration, but to alleviate bodily pain. It became, gradually and reluctantly, a necessity of his life. Like the serpents around Laocoon, it confirmed its grasp, notwithstanding the wild tossings of his arms, the spasmodic resistance of every muscle, the loud shouts of protesting agony; and, when conquered, he lay like the overpowered Hatteraick in the cave, sullen, still in despair, breathing hard, but perfectly powerless. Its effects on him, too, were of a peculiar kind. They were not brutifying or blackguardizing. He was never intoxicated with the drug in his life; nay, he denies its power to intoxicate. Nor did it at all weaken his intellectual faculties any more than it strengthened them. We have heard poor creatures consoling themselves for their inferiority by saying, "Coleridge would not have written so well but for opium." "No thanks to De Quincey for his subtlety—he owes it to opium." Let such persons swallow the drug, and try to write the "Suspiria," or the "Aids to Reflection."

Coleridge and De Quincey were great in spite of their habits. Nay, we believe that on truly great intellects stimulus produces little inspiration at all. Can opium think? can beer imagine? It is De Quincey in opium—not opium in De Quincey—that ponders and that writes. The stimulus is only the occasional cause which brings the internal power into play; it may sometimes dwarf the giant, but it can never really elevate the dwarf.

The evil influences of opium on De Quincey were of a different, but a very pernicious sort: they weakened his will; they made him a colossal slave to a tiny tyrant; they shut him up (like the Genii in the "Arabian Tales") in a[Pg 147] phial filled with dusky fire; they spread a torpor over the energies of his body; they closed up or poisoned the natural sources of enjoyment; the air, the light, the sunshine, the breeze, the influences of spring, lost all charm and power over him. Instead of these, snow was welcomed with an unnatural joy; storm embraced as a brother; and the stern scenery of night arose like a desolate temple round his ruined spirit. If his heart was not utterly hardened, it was owing to its peculiar breadth and warmth. At last his studies were interrupted, his peace broken, his health impaired, and then came the noon of his night; a form of gigantic gloom, swaying an "ebon sceptre," stood over him in triumph, and it seemed as if nothing less than a miraculous intervention could rescue the victim from his power.

But the victim was not an ordinary one. Feeling that hell had come, and that death was at hand, he determined, by a mighty effort, to arise from his degradation. For a season his struggles were great and impotent, as those of the giants cast down by Jove under Etna. The mountain shook, the burden tottered, but the light did not at first appear. Nor has he ever, we suspect, completely emancipated himself from his bondage; but he has struggled manfully against it, and has cast off such a large portion of the burden that it were injustice not to say of him that he is now free.

It were ungracious to have dwelt, even so long, upon the errors of De Quincey, were it not that, first, his own frankness of disclosures frees us from all delicacy; and that, secondly, the errors of such a man, like the cloud of the pillar, have two sides—his darkness may become our light—his sin our salvation. It may somewhat counteract that craving cry for excitement, that everlasting Give, give, so much the mistake of the age, to point strongly to this conspicuous and transcendent victim, and say to his admirers, "Go ye and do otherwise."

We pass gladly to the subject of his genius. That is certainly one of the most singular in its power, variety, culture, and eccentricity, our age has witnessed. His intellect is at once solid and subtle, reminding you of veined and figured marble, so beautiful and evasive in aspect, that you must touch ere you are certain of its firmness. The motion of his mind is like that of dancing, but it is the dance of an elephant, or of a Polyphemus, with his heavy steps, thundering down the music to which he moves. Hence his humor often seems forced in motion, while always fine in spirit. The contrast between the slow march of his sentences, the frequent gravity of his spirit, the recondite masses of his lore, the logical severity of his diction, and his determination, at times, to be desperately witty, produces a ludicrous effect, but somewhat different from what he had intended. It is "Laughter" lame, and only able to hold one of his sides, so that you laugh at, as well as with him. But few, we think, would have been hypercritical in judging of Columbus' first attitudes as he stepped down upon his new world. And thus, let a great intellectual explorer be permitted to occupy his own region, in whatever way, and with whatever ceremonies, may seem best to himself. Should he even, like Cæsar, stumble upon the shore, no matter if he stumble forward, and by accepting, make the omen change its nature and meaning.

Genius and logical perception are De Quincey's principal powers. There are some writers whose power, like the locusts in the Revelation, is "in their tails"—they have stings, and there lies their scorpion power. De Quincey's vigor is evenly and equally diffused through his whole being. It is not a partial palpitation, but a deep, steady glow. His insight hangs over us and the world like a nebulous star, seeing us, but, in part, remaining unseen. In fact, his deepest thoughts have never been disclosed. Like Burke, he has not "hung his heart upon his sleeve for daws to peck at." He has profound reticence as well as power, and he has modesty as well as reticence. On subjects with which he is acquainted, such as logic, literature, or political economy, no man can speak with more positive and perfect assurance. But on all topics where the conscience—the inner most moral nature—must be the umpire, "the English Opium Eater" is silent. His "silence" indeed, "answers very loud," his dumbness has a tongue, but it requires a "fine ear" to hear its accents; and to interpret them what but his own exquisitely subtle and musical style, like written sculpture, could suffice?

Indeed, De Quincey's style is one of the most wondrous of his gifts. As Professor Wilson once said to us about him, "the best word always comes up." It comes up easily, as a bubble on the wave; and is yet fixed, solid, and permanent as marble. It is at once warm as genius, and cool as logic. Frost and fire fulfill the paradox of "embracing each other." His faculties never disturb or distract each other's movements—they are inseparable, as substance and shadow. Each thought is twin-born with poetry. His sentences are generally very long, and as full of life and of joints as a serpent. It is told of Coleridge, that no shorthand-writer could do justice to his lectures; because, although he spoke deliberately, yet it was impossible, from the first part of his sentences, to have the slightest notion how they were to end—each clause was a new surprise, and the close often unexpected as a thunderbolt. In this, as in many other respects. De Quincey resembles the "noticeable man with large gray eyes." Each of his periods, begin where it may, accomplishes a cometary sweep ere it closes. To use an expression of his own, applied to Bishop Berkeley, "he passes, with the utmost ease and speed, from tar-water to the Trinity, from a mole-heap to the thrones of the Godhead." His sentences are microcosms—real, though imperfect wholes. It is as if he dreaded that earth would end, and chaos come again, ere each prodigious[Pg 148] period were done. This practice, so far from being ashamed of, he often and elaborately defends—contrasting it with the "short-winded and asthmatic" style of writing which abounds in modern times, and particularly among French authors. We humbly think that the truth on this question lies in the middle. If an author is anxious for fullness, let him use long sentences; if he aims at clearness, let them be short. If he is beating about for truth, his sentences will be long; if he deems he has found, and wishes to communicate it to others, they will be short. In long sentences you see processes; in short, results. Eloquence delights in long sentences, wit in short. Long sentences impress more at the time; short sentences, if nervous, cling more to the memory. From long sentences you must, in general, deduct a considerable quantum of verbiage; short have often a meagre and skeleton air. The reading of long sentences is more painful at first, less so afterward; a volume composed entirely of short sentences becomes soon as wearisome as a jest-book. The mind which employs long sentences has often a broad, but dim vision—that which delights in short, sees a great number of small points clearly, but seldom a rounded whole. De Quincey is a good specimen of the first class. The late Dr. Hamilton, of Leeds, was the most egregious instance of the second. With all his learning, and talent, and fancy, the writings of that distinguished divine are rendered exceedingly tedious by the broken and gasping character of their style—reading which has been compared to walking on stepping-stones instead of a firm road. Every thing is so clear, sharp, and short, that you get irritated and provoked, and cry out for an intricate or lengthy sentence, both as a trial to your wind, and as a relief to your weariness.

The best style of writing, in point of effect, is that which combines both forms of sentence in proper proportions. Just as a well-armed warrior of old, while he held the broadsword in his right hand, had the dagger of mercy suspended by his side, the effective writer, who can at one time wave the flaming brand of eloquence, can at another use the pointed poignard of direct statement, of close logic, or of keen and caustic wit. Thus did Burke, Hall, Horsley, and Chalmers.

Akin to De Quincey's length of sentence, is his ungovernable habit of digression. You can as soon calculate on the motions of a stream of the aurora, as on those of his mind. From the title of any one of his papers, you can never infer whether he is to treat the subject announced, or a hundred others—whether the subjects he is to treat are to be cognate, or contradictory, to the projected theme—whether, should he begin the subject, he shall ever finish it—or into how many foot-notes he is to draw away, as if into subterranean pipes, its pith and substance. At every possible angle of his road he contrives to break off, and hence he has never yet reached the end of a day's journey. Unlike Christian in the "Pilgrim," he welcomes every temptation to go astray—and, not content with shaking hands with old Worldly Wiseman, he must, before climbing Mount Difficulty, explore both the way of Danger and that of Destruction. It may be inquired, if this arise from the fertility or from the frailty of his genius—from his knowledge of, and dominion over every province of thought, or from his natural or acquired inability to resist "right-hand or left-hand defections," provided they promise to interest himself and to amuse his readers. Judging from Coleridge's similar practice, we are forced to conclude that it is in De Quincey too—a weakness fostered, if not produced, by long habits of self-indulgence.

And yet, notwithstanding such defects (and we might have added to them his use of logical formulæ at times when they appear simply ridiculous, his unnecessary scholasticism, and display of learning, the undue self-complacence with which he parades his peculiar views, and explodes his adversary's, however reputed and venerable, and a certain air of exaggeration which swathes all his written speech), what splendid powers this strange being, at all times and on all subjects, exerts! With what razor-like sharpness does he cut the most difficult distinctions! What learning is his—here compelling wonder, from its variety and minute accuracy; and there, from the philosophical grasp with which he holds it, in compressed masses! And, above all, what grand, sombre, Miltonic gleams his imagination casts around him on his way; and in what deep swells of organ-like music do his thoughts often, harmoniously and irrepressibly, move! The three prose-writers of this century, who, as it appears to us, approach most nearly to the giants of the era of Charles I., in spirit of genius and munificence of language, are, Edward Irving, in his preface to "Ben Ezra," Thomas Aird, in parts of his "Religious Characteristics," and Thomas De Quincey, in his "Confessions," and his "Suspiria de Profundis."

In coming down from an author to his works we have often a feeling of humiliation and disappointment. It is like comparing the great Ben Nevis with the streamlets which flow from his base, and asking, "Is this all the mighty mountain can give the world?" So, "What has De Quincey done?" is a question we are now sure to hear, and feel rather afraid to answer.

In a late number of that very excellent periodical, "Hogg's Instructor," Mr. De Quincey, as if anticipating some such objection, argues (referring to Professor Wilson), that it is ridiculous to expect a writer now to write a large separate work, as some had demanded from the professor. He is here, however, guilty of a fallacy, which we wonder he allowed to escape from his pen: there is a difference between a large and a great work. No one wishes either De Quincey or John Wilson to write a folio; what we wish from each of them is, an artistic[Pg 149] whole, large or comparatively small, fully reflecting the image of his mind, and bearing the relation to his other works which the "Paradise Lost" does to Milton's "Lycidas," "Arcades," and "Hymn on the Nativity." And this, precisely, is what neither of those illustrious men has as yet effected.

De Quincey's works, if collected, would certainly possess sufficient bulk; they lie scattered, in prodigal profusion, through the thousand and one volumes of our periodical literature; and we are certain, that a selection of their better portions would fill ten admirable octavos. Mr. De Quincey himself was lately urged to collect them. His reply was, "Sir, the thing is absolutely, insuperably, and forever impossible. Not the archangel Gabriel, nor his multipotent adversary, durst attempt any such thing!" We suspect, at least, that death must seal the lips of the "old man eloquent," ere such a selection shall be made. And yet, in those unsounded abysses, what treasures might be found—of criticism, of logic, of wit, of metaphysical acumen, of research, of burning eloquence, and essential poetry! We should meet there with admirable specimens of translation from Jean Paul Richter and Lessing; with a criticism on the former, quite equal to that more famous one of Carlyle's; with historical chapters, such as those in "Blackwood" on the Cæsars, worthy of Gibbon; with searching criticisms, such as one on the knocking in Macbeth, and two series on Landor and Schlosser; with the elephantine humor of his lectures on "Murder, considered as one of the fine arts;" and with the deep theological insight of his papers on Christianity, considered as a means of social progress, and on the Essenes. In fact, De Quincey's knowledge of theology is equal to that of two bishops—in metaphysics, he could puzzle any German professor—in astronomy, he has outshone Professor Nichol—in chemistry, he can outdive Samuel Brown—and in Greek, excite to jealousy the shades of Porson and Parr. There is another department in which he stands first, second, and third—we mean, the serious hoax. Do our readers remember the German romance of Walladmor, passed off at the Leipsic fair as one of Sir Walter Scott's, and afterward translated into English? The translation, which was, in fact, a new work, was executed by De Quincey, who, finding the original dull, thought proper to re-write it; and thus, to charge trick upon trick. Or have they ever read his chapter in "Blackwood" for July, 1837, on the "Retreat of a Tartar tribe?" a chapter certainly containing the most powerful historical painting we ever read, and recording a section of adventurous and romantic story not equaled, he says, "since the retreat of the fallen angels." This chapter, we have good reason for knowing, originated principally in his own inventive brain. Add to all this, the fiery eloquence of his "Confessions"—the labored speculation of his "Political Economy"—the curiously-perverted ingenuity of his "Klosterheim"—and the solemn, sustained, linked, and lyrical raptures of his "Suspiria," and we have answered the question, What has he done? But another question is less easy to answer, What can he, or should he, or shall he yet do? And here we venture to express a long-cherished opinion. Pure history, or that species of biography which merges into history, is his forte, and ought to have been his selected province. He never could have written a first-rate fiction or poem, or elaborated a complete or original system of philosophy, although both his imagination and his intellect are of a very high order. But he has every quality of the great historian, except compression; he has learning, insight, the power of reproducing the past, fancy to color, and wit to enliven his writing, and a style which, while it is unwieldy upon small subjects, rises to meet all great occasions, like a senator to salute a king. The only danger is, that if he were writing the history of the Crusades or Cæsars, for instance, his work would expand to the dimensions of the "Universal History."

A great history we do not now expect from De Quincey; but he might, produce some, as yet, unwritten life, such as the life of Dante, or of Milton. Such a work would at once concentrate his purpose, task his powers, and perpetuate his name.

As it is, his place in the future gallery of ages is somewhat uncertain. For all he has hitherto done, or for all the impression he has made upon the world, his course may be marked as that of a brilliant but timid meteor, shooting athwart the midnight, watched but by few eyes, but accompanied by the keenest interest and admiration of those who did watch it. Passages of his writings may be preserved in collections; and, among natural curiosities in the museum of man, his memory must assuredly be included as the greatest consumer of laudanum and learning—as possessing the most potent of brains, and the weakest of wills, of almost all men who ever lived.

We have other two remarks to offer ere we close. Our first is, that, with all his errors, De Quincey has never ceased to believe in Christianity. In an age when most men of letters have gone over to the skeptical side, and too often treat with insolent scorn, as sciolistic and shallow, those who still cling to the gospel, it is refreshing to find one who stands confessedly at the head of them all, in point of talent and learning, so intimately acquainted with the tenets, so profoundly impressed by the evidences, and so ready to do battle for the cause, of the blessed faith of Jesus. From those awful depths of sorrow in which he was long plunged, he never ceased to look up to the countenance and the cross of the Saviour; and now, recovered from his evils, and sins, and degradations, we seem to see him sitting, "clothed and in his right mind, at the feet of Jesus." Would to God that others of his class were to go, and to sit down beside him!

We may state, in fine, that efforts are at[Pg 150] present being made to procure for Mr. De Quincey a pension. A memorial on the subject has been presented to Lord John Russell. We need hardly say, that we cordially wish this effort all success. A pension would be to him a delicate sunset ray—soon, possibly, to shine on his bed of death—but, at all events, sure to minister a joy and a feeling of security, which, during all his long life, he has never for an hour experienced. It were but a proper reward for his eminent abilities, hard toils, and the uniform support which he has given, by his talents, to a healthy literature, and a spiritual faith. We trust, too, that government may be induced to couple with his name, in the same generous bestowal, another—inferior, indeed, in brilliance, but which represents a more consistent and a more useful life. We allude to Dr. Dick, of Broughty Ferry, a gentleman who has done more than any living author to popularize science—to accomplish the Socratic design of bringing down philosophy to earth—who has never ceased, at the same time, to exhale moral and religious feeling, as a fine incense, from the researches and experiments of science to the Eternal Throne—and who, for his laborious exertions, of nearly thirty years' duration, has been rewarded by poverty, and neglect, the "proud man's contumely," and, as yet, by the silence of a government which professes to be the patron of literature and the succorer of every species of merit in distress. To quote a newspaper-writer, who is well acquainted with the case: "I know that Dr. Dick has lived a long and a laborious life, writing books which have done much good to man. I know that he has often had occasion to sell these books to publishers, at prices to which his poverty, and not his will consented. I know, too, that throughout his life he has lived with the moderation and the meekness of a saint, as he has written with the wisdom of a sage; and, knowing these things, I would fain save him from the death of a martyr."

There is no really beautiful part of this kingdom so little known as the Peak of Derbyshire. Matlock, with its tea-garden trumpery and mock-heroic wonders; Buxton, with its bleak hills and fashionable bathers; the truly noble Chatsworth and the venerable Haddon, engross almost all that the public generally have seen of the Peak. It is talked of as a land of mountains, which in reality are only hills; but its true beauty lies in valleys that have been created by the rending of the earth in some primeval convulsion, and which present a thousand charms to the eyes of the lover of nature. How deliciously do the crystal waters of the Wye and the Dove rush along such valleys, or dales, as they there are called. With what a wild variety do the gray rocks soar up amid their woods and copses. How airily stand in the clear heavens the lofty limestone precipices, and the gray edges of rock gleam cut from the bare green downs—there never called downs. What a genuine Saxon air is there cast over the population—what a Saxon bluntness salutes you in their speech!

It is into the heart of this region that we propose now to carry the reader. Let him suppose himself with us now on the road from Ashford-in-the-water to Tideswell. We are at the Bull's Head, a little inn on that road. There is nothing to create wonder, or a suspicion of a hidden Arcadia in any thing you see, but another step forward, and—there! There sinks a world of valleys at your feet. To your left lies the delicious Monsal Dale. Old Finn Hill lifts his gray head grandly over it. Hobthrush's Castle stands bravely forth in the hollow of his side—gray, and desolate, and mysterious. The sweet Wye goes winding and sounding at his feet, amid its narrow green meadows, green as the emerald, and its dark glossy alders. Before us stretches on, equally beautiful, Cressbrook Dale; Little Edale shows its cottages from amidst its trees; and as we advance, the Mousselin-de-laine Mills stretch across the mouth of Miller's Dale, and startle with the aspect of so much life amid so much solitude.

But our way is still onward. We resist the attraction of Cressbrook village on its lofty eminence, and plunge to the right, into Wardlow Dale. Here we are buried deep in woods, and yet behold still deeper the valley descend below us. There is an Alpine feeling upon us. We are carried once more, as in a dream, into the Saxon Switzerland. Above us stretch the boldest ranges of lofty precipices, and deep amid the woods are heard the voices of children. These come from a few workmen's houses, couched at the foot of a cliff that rises high and bright amid the sun. That is Wardlow Cop; and there we mean to halt for a moment. Forward lies a wild region of hills, and valleys, and lead-mines, but forward goes no road, except such as you can make yourself through the tangled woods.

At the foot of Wardlow Cop, before this little hamlet of Bellamy Wick was built, or the glen was dignified with the name of Raven Dale, there lived a miner who had no term for his place of abode. He lived, he said, under Wardlow Cop, and that contented him.

His house was one of those little, solid, gray limestone cottages, with gray flagstone roofs, which abound in the Peak. It had stood under that lofty precipice when the woods which now so densely fill the valley were but newly planted. There had been a mine near it, which had no doubt been the occasion of its erection in so solitary a place; but that mine was now worked out and David Dunster, the miner, now worked[Pg 151] at a mine right over the hills in Miller's Dale. He was seldom at home, except at night, and on Sundays. His wife, besides keeping her little house, and digging and weeding in the strip of garden that lay on the steep slope above the house, hemmed in with a stone wall, also seamed stockings for a framework-knitter in Ashford, whither she went once or twice in the week.

They had three children, a boy and two girls. The boy was about eight years of age; the girls were about five and six. These children were taught their lessons of spelling and reading by the mother, among her other multifarious tasks; for she was one of those who are called regular plodders. She was quiet, patient, and always doing, though never in a bustle. She was not one of those who acquire a character for vast industry by doing every thing in a mighty flurry, though they contrive to find time for a tolerable deal of gossip under the plea of resting a bit, and which "resting a bit" they always terminate by an exclamation that "they must be off, though, for they have a world of work to do." Betty Dunster, on the contrary, was looked on as rather "a slow coach." If you remarked that she was a hard-working woman, the reply was, "Well, she's always doing—Betty's work's never done; but then she does na hurry hersen." The fact was, Betty was a thin, spare woman, of no very strong constitution, but of an untiring spirit. Her pleasure and rest were, when David came home at night, to have his supper ready, and to sit down opposite to him at the little round table, and help him, giving a bit now and then to the children, that came and stood round, though they had had their suppers, and were ready for bed as soon as they had seen something of their "dad."

David Dunster was one of those remarkably tall fellows that you see about these hills, who seem of all things the very worst made men to creep into the little mole holes on the hill sides that they call lead-mines. But David did manage to burrow under and through the hard limestone rooks as well as any of them. He was a hard-working man, though he liked a sup of beer, as most Derbyshire men do, and sometimes came home none of the soberest. He was naturally of a very hasty temper, and would fly into great rages; and if he were put out by any thing in the working of the mines, or the conduct of his fellow-workmen, he would stay away from home for days, drinking at Tideswell, or the Bull's Head, at the top of Monsal Dale, or down at the Miners' Arms at Ashford-in-the-water.

Betty Dunster bore all this patiently. She looked on these things somewhat as matters of course. At that time, and even now, how few miners do not drink and "rol a bit," as they call it. She was, therefore, tolerant, and let the storms blow over, ready always to persuade her husband to go home and sleep off his drink and anger, but if he were too violent, leaving him till another attempt might succeed better. She was very fond of her children, and not only taught them on week-days their lessons, and to help her to seam, but also took them to the Methodist Chapel in "Tidser," as they called Tideswell, whither, whenever she could, she enticed David. David, too, in his way, was fond of the children, especially of the boy, who was called David after him. He was quite wrapped up in the lad, to use the phrase of the people in that part; in fact, he was foolishly and mischievously fond of him. He would give him beer to drink, "to make a true Briton on him," as he said, spite of Betty's earnest endeavor to prevent it—telling him that he was laying the foundation in the lad of the same faults that he had himself. But David Dunster did not look on drinking as a fault at all. It was what he had been used to all his life. It was what all the miners had been used to for generations. A man was looked on as a milk-sop and a Molly Coddle, that would not take his mug of ale, and be merry with his comrades. It required the light of education, and the efforts that have been made by the Temperance Societies, to break in on this ancient custom of drinking, which, no doubt, has flourished in these hills since the Danes and other Scandinavians bored and perforated them of old for the ores of lead and copper. To Betty Dunster's remonstrances, and commendations of tea, David would reply, "Botheration, Betty, wench! Dunna tell me about thy tea and such-like pig's-wesh. It's all very well for women; but a man, Betty, a man mun ha' a sup of real stingo, lass. He mun ha' summut to prop his ribs out, lass, as he delves through th' chert and tood-stone. When tha weylds th' maundrel (the pick), and I wesh th' dishes, tha shall ha' th' drink, my wench, and I'll ha' th' tea. Till then, prithee let me aloon, and dunna bother me, for it's no use. It only kicks my monkey up."

And Betty found that it was of no use; that it did only kick his monkey up, and so she let him alone, except when she could drop in a persuasive word or two. The mill-owners at Cress brook and Miller's Dale had forbidden any public-house nearer than Edale, and they had more than once called the people together to point out to them the mischiefs of drinking, and the advantages to be derived from the very savings of temperance. But all these measures, though they had some effect on the mill people, had very little on the miners. They either sent to Tideswell or Edale for kegs of beer to peddle at the mines, or they went thither themselves on receiving their wages.

And let no one suppose that David Dunster was worse than his fellows, or that Betty Dunster thought her case a particularly hard one. David was "pretty much of a muchness," according to the country phrase, with the rest of his hard-working tribe, which was, and always had been, a hard-drinking tribe; and Betty, though she wished it different, did not complain just because it was of no use, and because she was no worse off than her neighbors.

Often when she went to "carry in her hose"[Pg 152] to Ashford, she left the children at home by themselves. She had no alternative. They were there in that solitary valley for many hours playing alone. And to them it was not solitary. It was all that they knew of life, and that all was very pleasant to them. In spring, they hunted for birds'-nests in the copses, and among the rocks and gray stones that had fallen from them. In the copses built the blackbirds and thrushes; in the rocks the firetails; and the gray wagtails in the stones, which were so exactly of their own color, as to make it difficult to see them. In summer, they gathered flowers and berries, and in the winter they played at horses, kings, and shops, and sundry other things in the house.

On one of these occasions, a bright afternoon in autumn, the three children had rambled down the glen, and found a world of amusement in being teams of horses, in making a little mine at the foot of a tall cliff; and in marching for soldiers, for they had one day—the only time in their lives—seen some soldiers go through the village of Ashford, when they had gone there with their mother, for she now and then took them with her when she had something from the shop to carry besides her bundle of hose. At length they came to the foot of an open hill, which swelled to a considerable height, with a round and climbable side, on which grew a wilderness of bushes, amid which lay scattered masses of gray crag. A small winding path went up this, and they followed it. It was not long, however, before they saw some things which excited their eager attention. Little David, who was the guide, and assumed to himself much importance as the protector of his sisters, exclaimed, "See here!" and springing forward, plucked a fine crimson cluster of the mountain bramble. His sisters, on seeing this, rushed on with like eagerness. They soon forsook the little winding and craggy footpath, and hurried through sinking masses of moss and dry grass, from bush to bush, and place to place. They were soon far up above the valley, and almost every step revealed to them some delightful prize. The clusters of the mountain-bramble, resembling mulberries, and known only to the inhabitants of the hills, were abundant, and were rapidly devoured. The dewberry was as eagerly gathered—its large, purple fruit passing with them for blackberries. In their hands were soon seen posies of the lovely grass of Parnassus, the mountain cistus, and the bright blue geranium.

Higher and higher the little group ascended in this quest, till the sight of the wide, naked hills, and the hawks circling round the lofty, tower-like crags over their heads, made them feel serious and somewhat afraid.

"Where are we?" asked Jane, the elder sister. "Arn't we a long way from hom?"

"Let us go hom," said little Nancy. "I'm afreed here;" clutching hold of Jane's frock.

"Pho, nonsense!" said David; "what are you afreed on? I'll tak care on you, niver fear."

And with this he assumed a bold and defying aspect, and said, "Come along; there are nests in th' hazzles up yonder."

He began to mount again, but the two girls hung back and said, "Nay, David, dunna go higher; we are both afreed;" and Jane added, "It's a long wee from hom, I'm sure."

"And those birds screechin' so up there; I darna go up," added little Nancy. They were the hawks that she meant, which hovered whimpering and screaming about the highest cliffs. David called them little cowards, but began to descend, and, presently, seeking for berries and flowers as they descended, they regained the little winding, craggy road, and, while they were calling to each other, discovered a remarkable echo on the opposite hill side. On this, they shouted to it, and laughed, and were half frightened when it laughed and shouted again. Little Nancy said it must be an old man in the inside of the mountain; at which they were all really afraid, though David put on a big look, and said, "Nonsense! it was nothing at all." But Jane asked how nothing at all could shout and laugh as it did? and on this little Nancy plucked her again by the frock, and said in turn, "Oh, dear, let's go hom!"

But at this David gave a wild whoop to frighten them, and when the hill whooped again, and the sisters began to run, he burst into laughter, and the strange spectral Ha! ha! ha! that ran along the inside of the hill, as it were, completed their fear, and they stopped their ears with their hands, and scuttled away down the hill. But now David seized them, and pulling their hands down from their heads, he said, "See here! what a nice place with the stones sticking out like seats. Why, it's like a little house; let us stay and play a bit here." It was a little hollow in the hill side surrounded by projecting stones like an amphitheatre. The sisters were still afraid, but the sight of this little hollow with its seats of crag had such a charm for them that they promised David they would stop awhile, if he would promise not to shout and awake the echo. David readily promised this, and so they sat down. David proposed to keep a school, and cut a hazel wand from a bush, and began to lord it over his two scholars in a very pompous manner. The two sisters pretended to be much afraid, and to read very diligently on pieces of flat stone which they had picked up. And then David became a sergeant, and was drilling them for soldiers, and stuck pieces of fern into their hair for cockades. And then, soon after, they were sheep, and he was the shepherd; and he was catching his flock and going to shear them, and made so much noise that Jane cried, "Hold! there's the echo mocking us."

At this they all were still. But David said, "Pho! never mind the echo; I must shear my sheep:" but just as he was seizing little Nancy to pretend to shear her with a piece of stick, Jane cried out, "Look! look! how black it is coming down the valley there! There's[Pg 153] going to be a dreadful starm. Let us hurry hom!"

David and Nancy both looked up, and agreed to run as fast down the hill as they could. But the next moment the driving storm swept over the hill, and the whole valley was hid in it. The three children still hurried on, but it became quite dark, and they soon lost the track, and were tossed about by the wind, so that they had difficulty to keep on their legs. Little Nancy began to cry, and the three taking hold of each other, endeavored in silence to make their way homeward. But presently they all stumbled over a large stone, and fell some distance down the hill. They were not hurt, but much frightened, for they now remembered the precipices, and were afraid every minute of going over them. They now strove to find the track by going up again, but they could not find it any where. Sometimes they went upward till they thought they were quite too far, and then they went downward till they were completely bewildered; and then, like the Babes in the Wood, "They sate them down and cried."

But ere they had sate long, they heard footsteps, and listened. They certainly heard them and shouted, but there was no answer. David shouted, "Help! fayther! mother! help!" but there was no answer. The wind swept fiercely by; the hawks whimpered from the high crags, lost in the darkness of the storm; and the rain fell, driving along icy cold. Presently there was a gleam of light through the clouds; the hill side became visible, and through the haze they saw a tall figure as of an old man ascending the hill. He appeared to carry two loads slung from his shoulders by a strap; a box hanging before, and a bag hanging at his back. He wound up the hill slowly and wearily, and presently he stopped, and relieving himself of his load, seated himself on a piece of crag to rest. Again David shouted, but there still was no answer. The old man sate as if no shout had been heard—immovable.

"It is a man," said David, "and I will mak him hear;" and with that he shouted once more with all his might. But the old man made no sign of recognition. He did not even turn his head, but he took off his hat and began to wipe his brow as if warm with the ascent.

"What can it be?" said David in astonishment. "It is a man, that's sartain. I'll run and see."

"Nay, nay!" shrieked the sisters. "Don't, David, don't! It's perhaps the old man out of the mountain that's been mocking us. Perhaps," added Jane, "he only comes out in starms and darkness."

"Stuff!" said David, "an echo isn't a man; it's only our own voices. I'll see who it is;" and away he darted, spite of the poor girls' crying in terror, "Don't; don't, David; oh, don't!"

But David was gone. He was not long in reaching the old man, who sate on his stone breathing hard, as if out of breath with his ascent, but not appearing to perceive David's approach. The rain and the wind drove fiercely upon him, but he did not seem to mind it. David was half afraid to approach close to him, but he called out, "Help! help, mester!" The old man remained as unconscious of his presence. "Hillo!" cried David again. "Can you tell us the way down, mester?" There was no answer, and David was beginning to feel a shudder of terror run through every limb, when the clouds cleared considerably, and he suddenly exclaimed, "Why, it's old Tobias Turton of top of Edale, and he's as deaf as a door nail!"

In an instant David was at his side; seized his coat to make him aware of his presence, and, on the old man perceiving him, shouted in his ear, "Which is the way down here, Mester Turton? Where's the track?"

"Down? Weighs o' the back?" said the old man; "ay, my lad, I was fain to sit down; it does weigh o' th' back, sure enough."

"Where's the foot-track?" shouted David, again.

"Th' foot-track? Why, what art ta doing here, my lad, in such a starm? Isn't it David Dunster's lad?"

David nodded. "Why, the track's here—see!" and the old man stamped his foot. "Get down hom, my lad, as fast as thou can. What dun they do letting thee be upon th' hills in such a dee as this?"

David nodded his thanks, and turned to descend the track, while the old man, adjusting his burden again, silently and wearily recommenced his way upward.

David shouted to his sisters as he descended, and they quickly replied. He called to them to come toward him, as he was on the track, and was afraid to quit it again. They endeavored to do this; but the darkness was now redoubled, and the wind and rain became more furious than ever. The two sisters were soon bewildered among the bushes; and David, who kept calling to them at intervals to direct their course toward him, soon heard them crying bitterly. At this, he forgot the necessity of keeping the track, and darting toward them, soon found them, by continuing to call to them, and took their hands to lead them to the track. But they were now drenched through with the rain, and shivered with cold and fear. David, with a stout heart, endeavored to cheer them. He told them the track was close by, and that they would soon be at home. But though the track was not ten yards off, somehow they did not find it. Bushes and projecting rocks turned them out of their course; and, owing to the confusion caused by the wind, the darkness, and their terror, they searched in vain for the track. Sometimes they thought they had found it, and went on a few paces, only to stumble over loose stones, or get entangled in the bushes.

It was now absolutely becoming night. Their terrors increased greatly. They shouted and cried aloud, in the hope of making their parents hear them. They felt sure that both father and[Pg 154] mother must be come home; and as sure that they would be hunting for them. But they did not reflect that their parents could not tell in what direction they had gone. Both father and mother were come home, and the mother had instantly rushed out to try to find them, on perceiving that they were not in the house. She had hurried to and fro, and called—not at first supposing they would be far. But when she heard nothing of them, she ran in, and begged of her husband to join in the search. But at first David Dunster would do nothing. He was angry at them for going away from the house, and said he was too tired to go on a wild-goose chase through the plantations after them. "They are i' th' plantations," said he; "they are sheltering there somewhere. Let them alone, and they'l come home, with a good long tail behind them."

With this piece of a child's song of sheep, David sat down to his supper, and Betty Dunster hurried up the valley, shouting, "Children, where are you? David! Jane! Nancy! where are you?"

When she heard nothing of them, she hurried still more wildly up the hill toward the village. When she arrived there—the distance of a mile —she inquired from house to house, but no one had seen any thing of them. It was clear they had not been in that direction. An alarm was thus created in the village; and several young men set out to join Mrs. Dunster in the quest. They again descended the valley toward Dunster's house, shouting every now and then, and listening. The night was pitch dark, and the rain fell heavily; but the wind had considerably abated, and once they thought they heard a faint cry in answer to their call, far down the valley. They were right: the children had heard the shouting, and had replied to it. But they were far off. The young men shouted again, but there was no answer; and after shouting once more without success, they hastened on. When they reached David Dunster's house, they found the door open, and no one within. They knew that David had set off in quest of the children himself, and they determined to descend the valley. The distracted mother went with them, crying silently to herself, and praying inwardly, and every now and then trying to shout. But the young men raised their strong voices above hers, and made the cliffs echo with their appeals.

Anon a voice answered them down the valley. They ran on as well as the darkness would let them, and soon found that it was David Dunster, who had been in the plantations on the other side of the valley; but hearing nothing of the lost children, now joined them. He said he had heard the cry from the hill side farther down, that answered to their shouts; and he was sure that it was his boy David's voice. But he had shouted again, and there had been no answer but a wild scream as of terror, that made his blood run cold.

"O God!" exclaimed the distracted mother, "what can it be! David! David! Jane Nancy!"

There was no answer. The young men bade Betty Dunster to contain herself, and they would find the children before they went home again. All held on down the valley, and in the direction whence the voice came. Many times did the young men and the now strongly agitated father shout and listen. At length they seemed to hear voices of weeping and moaning. They listened—they were sure they heard a lamenting—it could only be the children. But why then did they not answer? On struggled the men, and Mrs. Dunster followed wildly after. Now, again, they stood and shouted, and a kind of terrified scream followed the shout.

"God in heaven!" exclaimed the mother; "what is it? There is something dreadful. My children! my children! where are you?"

"Be silent, pray do, Mrs. Dunster," said one of the young men, "or we can not catch the sounds so as to follow them." They again listened, and the wailings of the children were plainly heard. The whole party pushed forward over stock and stone up the hill. They called again, and there was a cry of "Here! here! fayther! mother! where are you?"

In a few moments more the whole party had reached the children, who stood drenched with rain, and trembling violently, under a cliff that gave no shelter, but was exposed especially to the wind and rain.

"O Christ! my children!" cried the mother, wildly, struggling forward and clasping one in her arms. "Nancy! Jane! But where is David? David! David! Oh, where is David? Where is your brother?"

The whole party was startled at not seeing the boy, and joined in a simultaneous "Where is he? where is your brother?"

The two children only wept and trembled more violently, and burst into loud crying.

"Silence!" shouted the father. "Where is David? I tell ye? Is he lost? David, lad, where ar ta?"

All listened, but there was no answer but the renewed crying of the two girls.

"Where is the lad, then?" thundered forth the father with a terrible oath.

The two terrified children cried, "Oh, down there! down there!"

"Down where? Oh, God!" exclaimed one of the young men; "why it's a precipice! Down there!"

At this dreadful intelligence the mother gave a wild shriek, and fell senseless on the ground. The young men caught her, and dragged her back from the edge of the precipice. The father in the same moment, furious at what he heard, seized the younger child, that happened to be near him, and shaking it violently, swore he would fling it down after the lad.

He was angry with the poor children, as if they had caused the destruction of his boy. The young men seized him, and bade him think what he was about; but the man believing his[Pg 155] boy had fallen down the precipice, was like a madman. He kicked at his wife as she lay on the ground, as if she were guilty of this calamity by leaving the children at home. He was furious against the poor girls, as if they had led their brother into danger. In his violent rage he was a perfect maniac, and the young men pushing him away, cried shame on him. In a while, the desperate man, torn by a hurricane of passion, sate himself down on a crag, and burst into a tempest of tears, and struck his head violently with his clenched fists, and cursed himself and every body. It was a dreadful scene.

Meantime, some of the young men had gone down below the precipice on which the children had stood, and, feeling among the loose stones, had found the body of poor little David. He was truly dead!

When he had heard the shout of his father, or of the young men, he had given one loud shout in answer, and saying, "Come on! never fear now!" sprang forward, and was over the precipice in the dark, and flew down, and was dashed to pieces. His sisters heard a rush, a faint shriek, and suddenly stopping, escaped the destruction that poor David had found.

We must pass over the painful and dreadful particulars of that night, and of a long time to come; the maniacal rage of the father, the shattered heart and feelings of the mother, the dreadful state of the two remaining children, to whom their brother was one of the most precious objects in a world which, like theirs, contained so few. One moment to have seen him full of life, and fun, and bravado, and almost the next a lifeless and battered corpse, was something too strange and terrible to be soon surmounted. But this was woefully aggravated by the cruel anger of their father, who continued to regard them as guilty of the death of his favorite boy. He seemed to take no pleasure in them. He never spoke to them but to scold them. He drank more deeply than ever, and came home later; and when there, was sullen and morose. When their mother, who suffered severely, but still plodded on with all her duties, said, "David, they are thy children too," he would reply, savagely, "Hod thy tongue! What's a pack o' wenches to my lad?"

What tended to render the miner more hard toward the two girls was a circumstance which would have awakened a better feeling in a softer father's heart. Nancy, the younger girl, since the dreadful catastrophe, had seemed to grow gradually dull and defective in her intellect, she had a slow and somewhat idiotic air and manner. Her mother perceived it, and was struck with consternation by it. She tried to rouse her, but in vain. She could not perform her ordinary reading and spelling lessons. She seemed to have forgotten what was already learned. She appeared to have a difficulty in moving her legs, and carried her hands as if she had suffered a partial paralysis. Jane, her sister, was dreadfully distressed at it, and she and her mother wept many bitter tears over her. One day, in the following spring, they took her with them to Ashford, and consulted the doctor there. On examining her, and hearing fully what had taken place at the time of the brother's death—the fact of which he well knew, for it, of course, was known to the whole country round—he shook his head, and said he was afraid they must make up their minds to a sad case; that the terrors of that night had affected her brain, and that, through it, the whole nervous system had suffered, and was continuing to suffer the most melancholy effects. The only thing, he thought, in her favor was her youth; and added, that it might have a good effect, if they could leave the place where she had undergone such a terrible shock. But whether they did or not, kindness and soothing attentions to her would do more than any thing else.

Mrs. Dunster and little Jane returned home with heavy hearts. The doctor's opinion had only confirmed their fears; for Jane, though but a child, had quickness and affection for her sister enough to make her comprehend the awful nature of poor Nancy's condition. Mrs. Dunster told her husband the doctor's words, for she thought they would awaken some tenderness in him toward the unfortunate child. But he said, "That's just what I expected. Hou'll grow soft, and then who's to maintain her? Hou mun goo to th' workhouse."

With that he took his maundrel and went off to his work. Instead of softening his nature, this intelligence seemed only to harden and brutalize it. He drank now more and more. But all that summer the mother and Jane did all that they could think of to restore the health and mind of poor Nancy. Every morning, when the father was gone to work, Jane went to a spring up in the opposite wood, famed for the coldness and sweetness of its waters. On this account the proprietors of the mills at Cressbrook had put down a large trough there under the spreading trees, and the people fetched the water even from the village. Hence Jane brought, at many journeys, this cold, delicious water to bathe her sister in; they then rubbed her warm with cloths, and gave her new milk for her breakfast. Her lessons were not left off, lest the mind should sink into fatuity, but were made as easy as possible. Jane continued to talk to her, and laugh with her, as if nothing was amiss, though she did it with a heavy heart, and she engaged her to weed and hoe with her in their little garden. She did not dare to lead her far out into the valley, lest it might excite her memory of the past fearful time, but she gathered her flowers, and continued to play with her at all their accustomed sports, of building houses with pieces of pots and stones, and imagining gardens and parks. The anxious mother, when some weeks were gone by, fancied that[Pg 156] there was really some improvement. The cold-bathing seemed to have strengthened the system: the poor child walked, and bore herself with more freedom and firmness. She became ardently fond of being with her sister, and attentive to her directions. But there was a dull cloud over her intellect, and a vacancy in her eyes and features. She was quiet, easily pleased, but seemed to have little volition of her own. Mrs. Dunster thought if they could but get her away from that spot, it might rouse her mind from its sleep. But, perhaps, the sleep was better than the awaking might be; however, the removal came, though in a more awful way than was looked for. The miner, who had continued to drink more and more, and seemed to have almost estranged himself from his home, staying away in his drinking bouts for a week or more together, was one day blasting a rock in the mine, and being half-stupefied with beer, did not take care to get out of the way of the explosion, was struck with a piece of the flying stone, and killed on the spot.

The poor widow and her children were now obliged to remove from under Wardlow-Cop. The place had been a sad one to her; the death of her husband, though he had been latterly far from a good one, and had left her with the children in deep poverty, was a fresh source of severe grief to her. Her religious mind was struck down with a weight of melancholy by the reflection of the life he had led, and the sudden way in which he had been summoned into eternity. When she looked forward, what a prospect was there for her children! It was impossible for her to maintain them from her small earnings, and as to Nancy, would she ever be able to earn her own bread, and protect herself in the world?

It was amid such reflections that Mrs. Dunster quitted this deep, solitary, and, to her, fatal valley, and took up her abode in the village of Cressbrook. Here she had one small room, and by her own labors, and some aid from the parish, she managed to support herself and the children. For seven years she continued her laborious life, assisted by the labor of the two daughters, who also seamed stockings, and in the evenings were instructed by her. Her girls were now thirteen and fifteen years of age: Jane was a tall and very pretty girl of her years; she was active, industrious, and sweet-tempered: her constant affection for poor Nancy was something as admirable as it was singular. Nancy had now confirmed good health, but it had affected her mother to perceive that, since the catastrophe of her brother's death, and the cruel treatment of her father at that time, she had never grown in any degree as she ought; she was short, stout, and of a pale and very plain countenance. It could not be now said that she was deficient in mind, but she was slow in its operations. She displayed, indeed, a more than ordinary depth of reflection, and a shrewdness of observation, but the evidences of-this came forth in a very quiet way, and were observable only to her mother and sister. To all besides she was extremely reserved: she was timid to excess, and shrunk from public notice into the society of her mother and sister. There was a feeling abroad in the neighborhood that she was "not quite right," but the few who were more discerning, shook their heads, and observed, "Right, she was not, poor thing, but it was not want of sense; she had more of that than most."

And such was the opinion of her mother and sister. They perceived that Nancy had received a shock of which she must bear the effects through life. Circumstances might bring her feeble but sensitive nerves much misery. She required to be guarded and sheltered from the rudenesses of the world, and the mother trembled to think how much she might be exposed to them. But in every thing that related to sound judgment, they knew that she surpassed not only them, but any of their acquaintance. If any difficulty had to be decided, it was Nancy who pondered on it, and, perhaps, at some moment when least expected, pronounced an opinion that might be taken as confidently as an oracle.

The affection of the two sisters was something beyond the ties of this world. Jane had watched and attended to her from the time of her constitutional injury with a love that never seemed to know a moment's weariness or change; and the affection which Nancy evinced for her was equally intense and affecting. She seemed to hang on her society for her very life. Jane felt this, and vowed that they would never quit one another. The mother sighed. How many things, she thought, might tear asunder that beautiful resolve.

But now they were of an age to obtain work in the mill. Indeed, Jane could have had employment there long before, but she would not quit her sister till she could go with her—and now there they went. The proprietor, who knew the case familiarly, so ordered it that the two sisters should work near each other; and that poor Nancy should be as little exposed to the rudeness of the work-people as possible. But at first so slow and awkward were Nancy's endeavors, and such an effect had it on her frame, that it was feared she must give it up. This would have been a terrible calamity; and the tears of the two sisters and the benevolence of the employer enabled Nancy to pass through this severe ordeal. In a while she acquired sufficient dexterity, and thenceforward went through her work with great accuracy and perseverance. As far as any intercourse with the workpeople was concerned, she might be said to be dumb. Scarcely ever did she exchange a word with any one, but she returned kind nods and smiles; and every morning and evening, and at dinner-time, the two sisters might be seen going to and fro, side by side—Jane often talking with some of them; the little, odd-looking sister walking silent and listening.

Five more years, and Jane was a young woman. Amid her companions, who were few of them above the middle size, she had a tall[Pg 157] and striking appearance. Her father had been a remarkably tall and strong man, and she possessed something of his stature, though none of his irritable disposition. She was extremely pretty, of a blooming, fresh complexion, and graceful form. She was remarkable for the sweetness of her expression, which was the index of her disposition. By her side still went that odd, broad-built, but still pale and little sister. Jane was extremely admired by the young men of the neighborhood, and had already many offers, but she listened to none. "Where I go must Nancy go," she said to herself, "and of whom can I be sure?"

Of Nancy no one took notice. Her pale, somewhat large features, her thoughtful, silent look, and her short, stout figure, gave you an idea of a dwarf, though she could not strictly be called one. No one would think of Nancy as a wife—where Jane went she must go; the two clung together with one heart and soul. The blow which deprived them of their brother seemed to bind them inseparably together.

Mrs. Dunster, besides her seaming, at which, in truth, she earned a miserable sum, had now for some years been the post-woman from the village to the Bull's Head, where the mail, going on to Tideswell, left the letter-bag. Thither and back, wet or dry, summer or winter, she went every day, the year round. With her earnings, and those of the girls, the world went as well with them as the world goes on the average with the poor; and she kept a small, neat cottage. Cramps and rheumatisms she began to feel sensibly from so much exposure to rain and cold; but the never-varying and firm affection of her two children was a balm in her cup which made her contented with every thing else.

When Jane was about two-and-twenty, poor Mrs. Dunster, seized with rheumatic fever, died. On her death-bed, she said to Jane, "Thou will never desert poor Nancy; and that's my comfort. God has been good to me. After all my trouble, he has given me this faith, that, come weal, come woe, so long as thou has a home, Nancy will never want one. God bless thee for it! God bless you both; and he will bless you!" So saying, Betty Dunster breathed her last.

The events immediately following her death did not seem to bear out her dying faith; for the two poor girls were obliged to give up their cottage. There was a want of cottages. Not half of the work-people could be entertained in this village; they went to and fro for many miles. Jane and Nancy were now obliged to do the same. Their cottage was wanted for an overlooker—and they removed to Tideswell, three miles off. They had thus six miles a day to walk, besides standing at their work; but they were young, and had companions. In Tideswell they were more cheerful. They had a snug little cottage; were near a meeting; and found friends. They did not complain. Here, again Jane Dunster attracted great attention, and a young, thriving grocer paid his addresses to her. It was an offer that made Jane take time to reflect. Every one said it was an opportunity not to be neglected: but Jane weighed in her mind, "Will he keep faith in my compact with Nancy?" Though her admirer made every vow on the subject, Jane paused and determined to take the opinion of Nancy. Nancy thought for a day, and then said, "Dearest sister, I don't feel easy; I fear that from some cause it would not do in the end."

Jane, from that moment, gave up the idea of the connection. There might be those who would suspect Nancy of a selfish bias in the advice she gave; but Jane knew that no such feeling influenced her pure soul. For one long year the two sisters traversed the hills between Cressbrook and Tideswell. But they had companions, and it was pleasant in the summer months. But winter came, and then it was a severe trial. To rise in the dark, and traverse those wild and bleak hills; to go through snow and drizzle, and face the sharpest winds in winter, was no trifling matter. Before winter was over, the two young women began seriously to revolve the chances of a nearer residence, or a change of employ. There were not few who blamed Jane excessively for the folly of refusing the last good offer. There were even more than one who, in the hearing of Nancy, blamed her. Nancy was thoughtful, agitated, and wept. "If I can, dear sister," she said, "have advised you to your injury, how shall I forgive myself? What shall become of me?"

But Jane clasped her sister to her heart, and said, "No! no! dearest sister, you are not to blame. I feel you are right; let us wait, and we shall see!"

One evening, as the two sisters were hastening along the road through the woods on their way homeward, a young farmer drove up in his spring-cart, cast a look at them, stopped, and said, "Young women, if you are going my way. I shall be glad of your company. You are quite welcome to ride."

The sisters looked at each other. "Dunna be afreed," said the young farmer; "my name's James Cheshire. I'm well known in these parts; you may trust yersens wi' me, if it's agreeable."

To Jane's surprise, Nancy said, "No, sir, we are not afraid; we are much obliged to you."

The young farmer helped them up into the cart, and away they drove.

"I'm afraid we shall crowd you," said Jane.

"Not a bit of it," replied the young farmer. "There's room for three bigger nor us on this seat, and I'm no ways tedious."

The sisters saw nothing odd in his use of the word "tedious," as strangers would have done[Pg 158] they knew it merely meant "not at all particular." They were soon in active talk. As he had told them who he was, he asked them in their turn if they worked at the mills there. They replied in the affirmative, and the young man said,

"I thought so. I've seen you sometimes going along together. I noticed you because you seemed so sisterly like, and you are sisters, I reckon."

They said "Yes."

"I've a good spanking horse, you seen," said James Cheshire. "I shall get over th' ground rayther faster nor you done a-foot, eh? My word, though, it must be nation cold on these bleak hills i' winter."

The sisters assented, and thanked the young farmer for taking them up.

"We are rather late," said they, "for we looked in on a friend, and the rest of the mill-hands were gone on."

"Well," said the young farmer, "never mind that. I fancy Bess, my mare here, can go a little faster nor they can. We shall very likely be at Tidser as soon as they are."

"But you are not going to Tidser," said Jane, "your farm is just before us there."

"Yay, I'm going to Tidser though. I've a bit of business to do there before I go hom."

On drove the farmer at what he called a spanking rate; presently they saw the young mill-people on the road before them.

"There are your companions," said James Cheshire; "we shall cut past them like a flash of lightning."

"Oh," exclaimed Jane Dunster, "what will they say at seeing us riding here?" and she blushed brightly.

"Say?" said the young farmer, smiling, "never mind what they'll say; depend upon it, they'd like to be here theirsens."

James Cheshire cracked his whip. The horse flew along. The party of the young mill-hands turned round, and on seeing Jane and Nancy in the cart, uttered exclamations of surprise.

"My word, though!" said Mary Smedley, a fresh buxom lass, somewhat inclined to stoutness.

"Well, if ever!" cried smart little Hannah Bowyer.

"Nay, then, what next?" said Tetty Wilton, a tall, thin girl of very good looks.

The two sisters nodded and smiled to their companions; Jane still blushing rosily, but Nancy sitting as pale and as gravely as if they were going on some solemn business.

The only notice the farmer took was to turn with a broad, smiling face, and shout to them, "Wouldn't you like to be here too?"

"Ay, take us up," shouted a number of voices together; but the farmer cracked his whip, and giving them a nod and a dozen smiles in one, said, "I can't stay. Ask the next farmer that comes up."

With this they drove on; the young farmer very merry and full of talk. They were soon by the side of his farm. "There's a flock of sheep on the turnips there," he said, proudly, "they're not to be beaten on this side Ashbourne. And there are some black oxen, going for the night to the straw-yard. Jolly fellows, those, eh? But I reckon you don't understand much of farming stock?"