The Project Gutenberg EBook of Soil Culture, by J. H. Walden This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Soil Culture Author: J. H. Walden Release Date: January 15, 2010 [EBook #30975] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOIL CULTURE *** Produced by Steven Giacomelli and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images produced by Core Historical Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University)

NEW YORK:

PUBLISHED BY ROBERT SEARS,

181 WILLIAM STREET.

[Pg 3]1858.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, By J. H. WALDEN, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, in and for the Northern District of Illinois.

SAVAGE & McCREA, STEREOTYPERS, C. A. ALVORD, Printer,

13 Chambers Street, N.Y. No. 15 Vandewater Street, N.Y.

If "he who causes two blades of grass to grow where but one grew before, is a benefactor of his race," he is not less so who imparts to millions a knowledge of the methods by which it is done.

The last half century has been the era of experiments and writing on the cultivation of the soil. The result has been the acquisition of more knowledge on the subjects embraced, than the world had attained in all its previous history. That knowledge is scattered through many volumes of numerous periodicals and books, and interspersed with many theories, and much speculation, that can never be valuable in practice. In the form in which it is presented, it confuses, rather than aids, the great mass of cultivators. Hence the prejudice against "book-farming." Provided established facts only are presented, they are none the worse for being printed.

The object of this volume is to condense, and present in an intelligible form, all important established facts in the science of soil-culture. The author claims originality, as to the discovery of facts and [Pg 6]principles, in but few cases. During ten years of preparatory study for this work, he has sought the rewards of industry, in sifting out the certain and the useful from the hypothetical and the fanciful, and the results of judicious discrimination between fallacy and just reasoning, in support of theories. This volume is designed to be a complete manual for all but amateur cultivators. While it is believed that he who follows its directions will be certain of success, it is not intended to disparage the merits of other works, but to encourage and extend their perusal. We can not too strongly recommend to young culturists to keep themselves well posted in this kind of literature, and give to every discovery and invention in this science a fair trial; not on a large scale, so as to sink money in fruitless experiments, but sufficient to afford a sure test of their real value. To no class of men is study more important than to soil-culturists.

It is believed that the directions here given, if followed, will save millions of dollars annually to that class of cultivators who can least afford to waste time and money in experimenting. With beginners it is important to be successful at first; which is impossible without availing themselves of the experience of others. While we thus aim to give our volume this exclusively practical form, and utilitarian character, we do not undervalue the labors of amateur cultivators. A meed of praise is due to those who are willing to spend time and money in experiments, by which great truths are evolved for the benefit of mankind.[Pg 7]

Perfection is not claimed for this volume. But the author hopes nothing will be found here that is untrue. A fear of inserting errors may have induced us to omit some things that may yet prove valuable. If anything seems to be at variance with a cultivator's observation, in a given locality, he will discover in our general principles on climate, soil, and location, that it is a natural result.

Accurate as far as we go has been our motto. It is hoped the form is most convenient. All is arranged under one alphabet, with a complete index. The author has consulted many intelligent cultivators and writers, who, without exception, approve his plan. All agree in saying that it is designed to fill a place not occupied by any other single volume in the language. It is impossible, without cumbering the volume, to give suitable credit to the authors and persons consulted. Suffice it to say, the author has carefully studied all the works mentioned in this volume, and availed himself of a great variety of verbal suggestions, by scientific and practical men. If this work shall, in any good degree, serve the purpose for which it is intended, it will amply reward the author for an amount of labor, experiment, observation, and study, appreciable only by few.

New York, January 1, 1858.[Pg 8]

| PAGE | |

| Apple-Worms | 22 |

| Apple-Tree Borer | 24 |

| Caterpillar Eggs | 25 |

| Canker-Worm Moths | 25 |

| Baldwin Apple | 34 |

| Bellflower Apple | 35 |

| Early Harvest Apple | 36 |

| Spitzbergen Apple | 37 |

| Rhode Island Greening | 38 |

| Fall Pippin | 39 |

| Newtown Pippin | 40 |

| Rambo Apple | 41 |

| Rome Beauty | 42 |

| Westfield Seek-no-further | 43 |

| Northern Spy | 44 |

| Roxbury Russet | 45 |

| Swaar Apple | 46 |

| Maiden's Blush | 47 |

| Barberries | 56 |

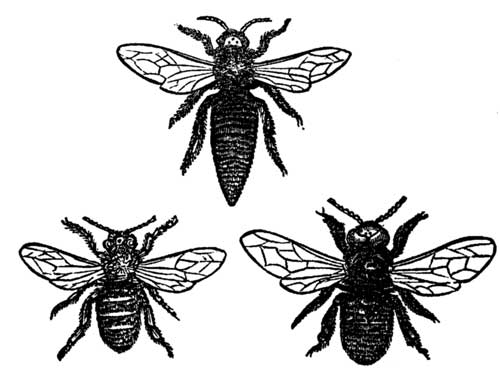

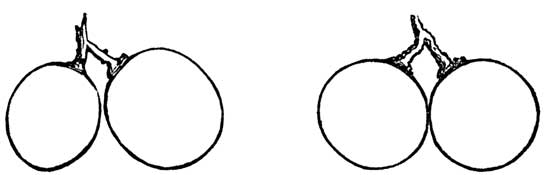

| Working Bee, Queen and Drone | 69 |

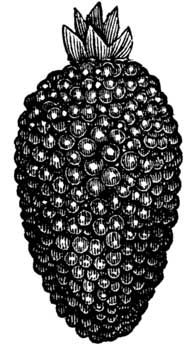

| High-Bush Blackberry | 83 |

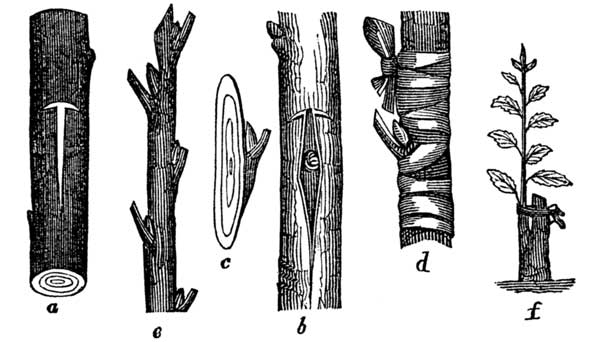

| Budding (Six Illustrations) | 91 |

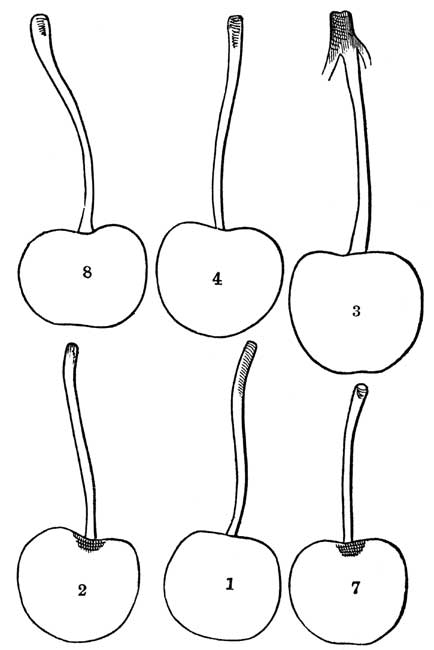

| Cherries (Six Illustrations) | 122 |

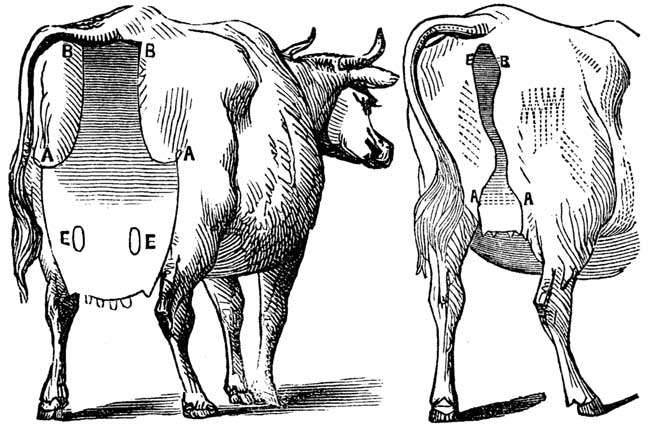

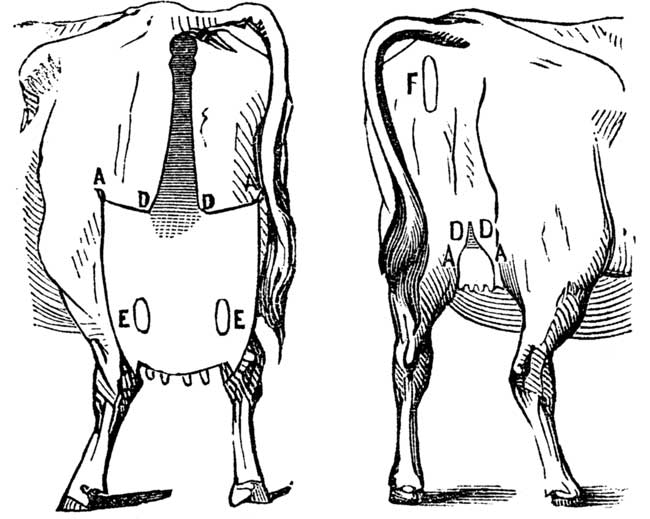

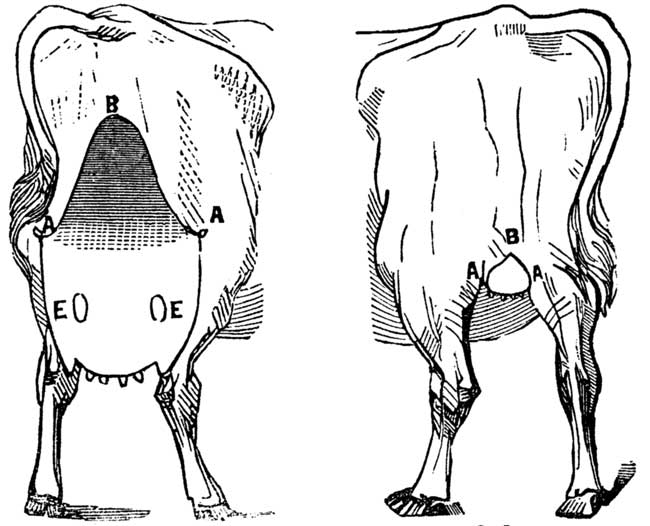

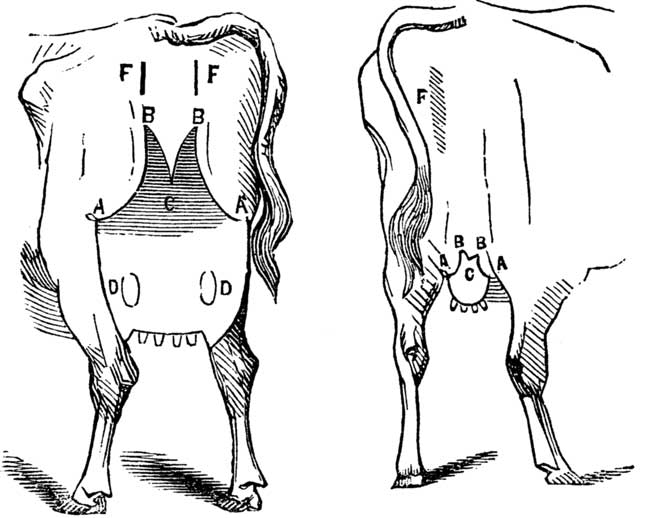

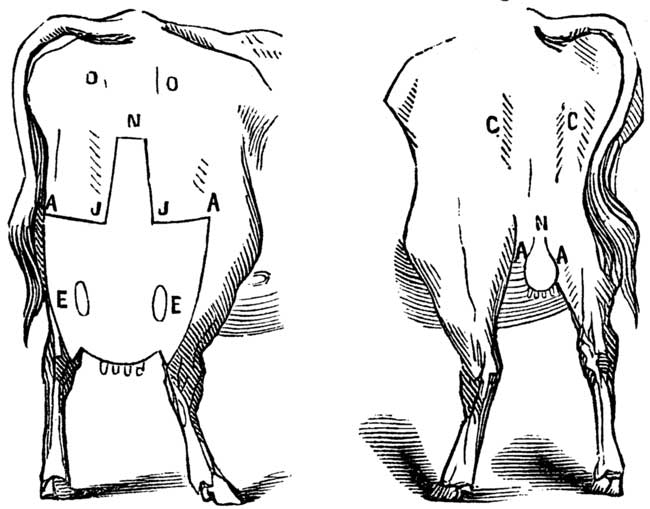

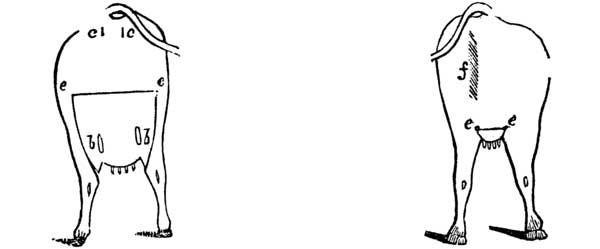

| Milking Qualities of Cows Illustrated | |

| The Flanders Cow | 145 |

| The Selvage Cow | 147 |

| The Curveline Cow | 148 |

| The Bicorn Cow | 149 |

| The Demijohn Cow | 150 |

| The Square Escutcheon Cow | 151 |

| The Lemousine Cow | 151 |

| The Horizontal Cut Cow | 152 |

| Bastards | 152 |

| Cranberries | 156 |

| Fig | 181 |

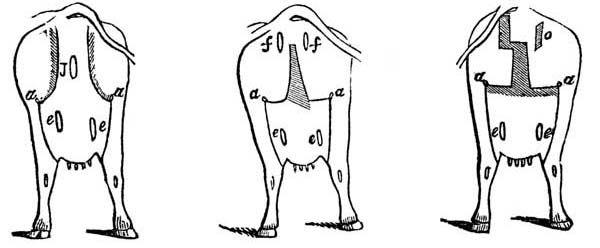

| Cleft and Tongue Grafting | 210 |

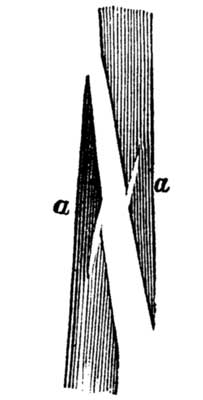

| Isabella Grapes | 223 |

| Catawba Grapes | 223 |

| Rebecca Grapes | 224 |

| Delaware Grapes | 225 |

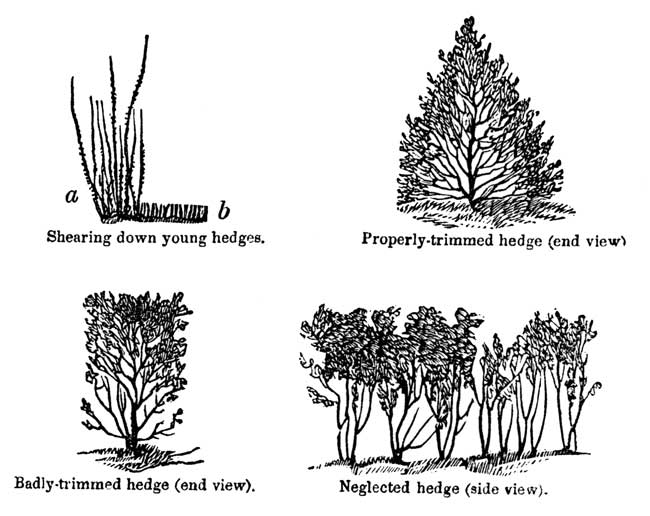

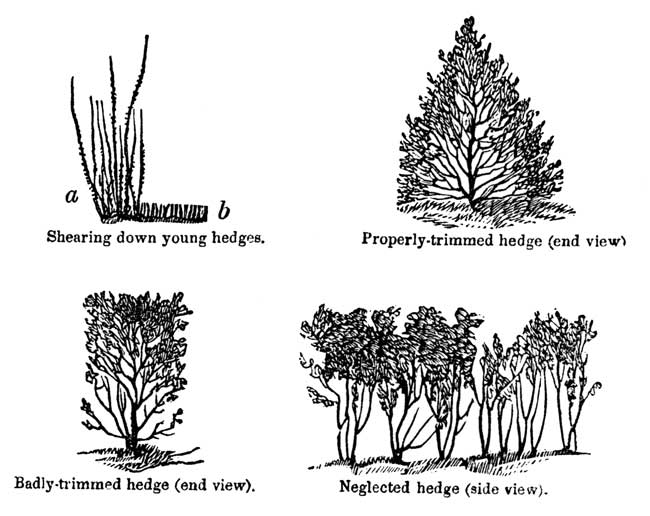

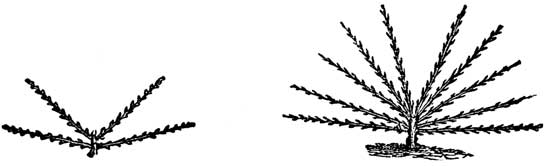

| Hedge-Pruning (4 engravings) | 238 |

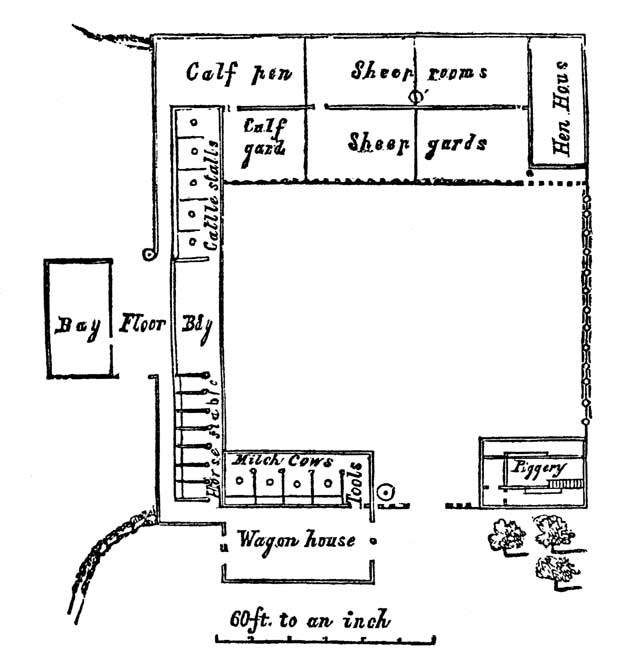

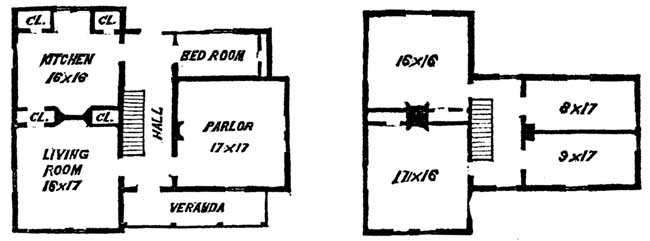

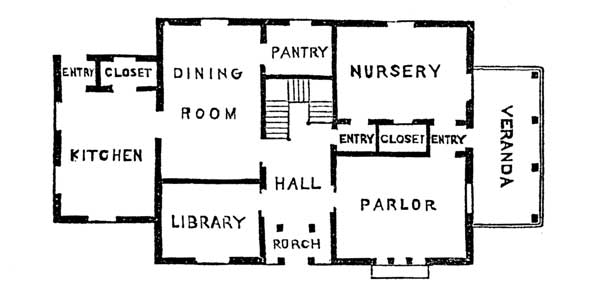

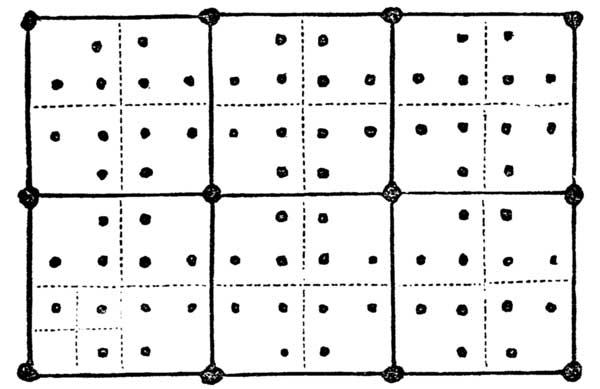

| Ground Plan of Farm Buildings | 252 |

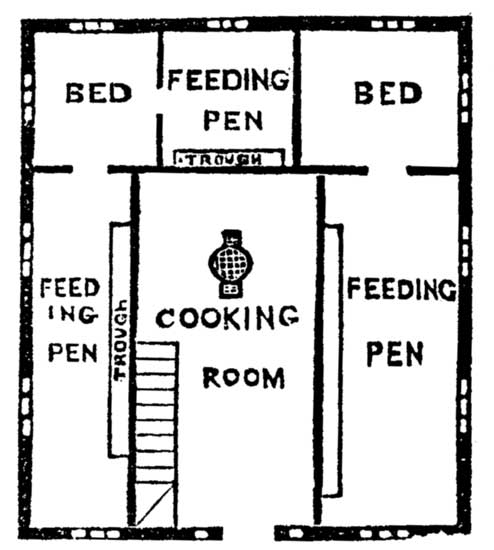

| Ground Plan of Piggery | 253 |

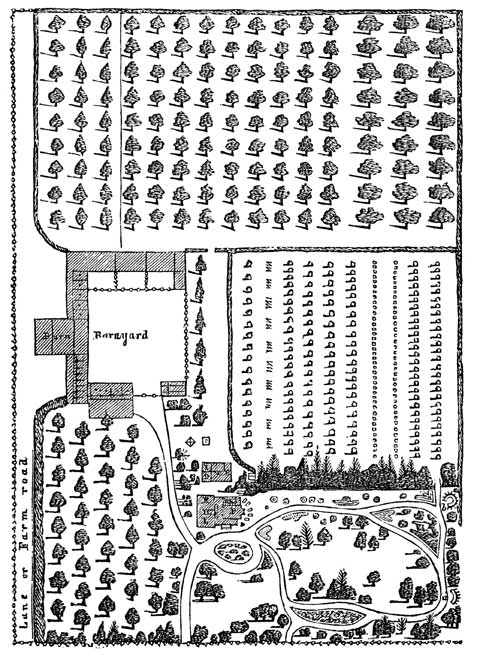

| Ground Plan of Country Residence, Farm Buildings, Fruit Garden, and Grounds | 254 |

| Laying out Curves Illustrated | 255 |

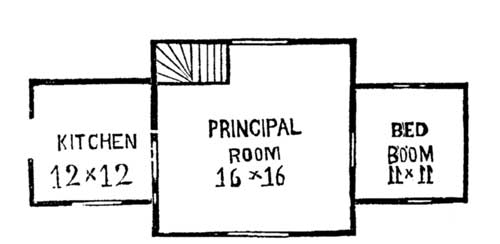

| Ground Plan of Farm-House | 255 |

| Summer-House | 256 |

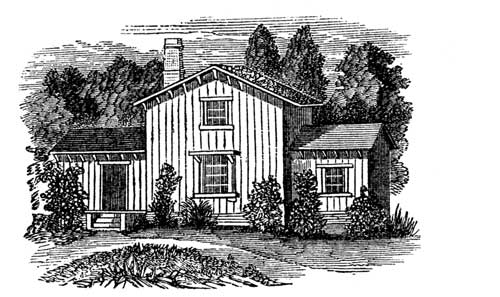

| Laborer's Cottage | 257 |

| Ground Plan of Laborer's Cottage | 257 |

| Italian Farm-House | 258 |

| Ground Plan of Italian Farm-House | 258 |

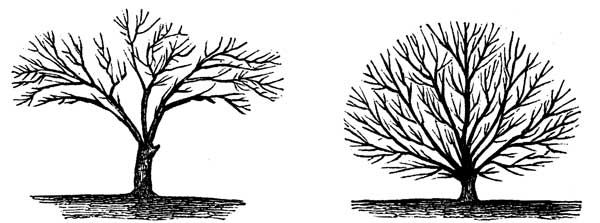

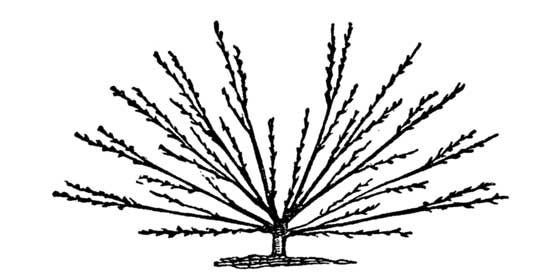

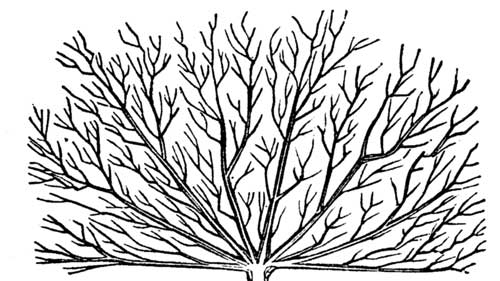

| Neglected Peach-Tree | 324 |

| Properly-Trimmed Peach-Tree | 324 |

| Plan of a Pear-Orchard | 338 |

| Bartlett Pear | 340 |

| Beurré Diel Pear | 341 |

| White Doyenne Pear | 342 |

| Flemish Beauty | 343 |

| Seckel | 345 |

| Gray Doyenne Pear | 346 |

| The Curculio | 355 |

| Lawrence's Favorite Plum | 356 |

| Imperial Gage | 357 |

| Egg-Plum | 357 |

| Green Gage | 358 |

| Jefferson Plum | 358 |

| Washington Plum | 359 |

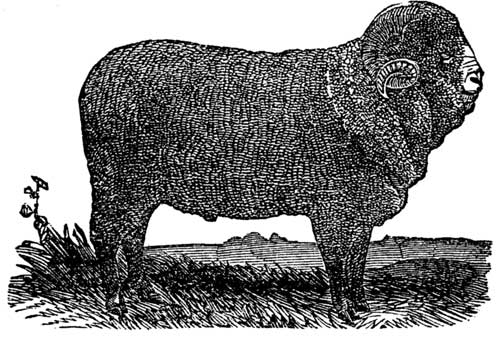

| French Merino Ram | 386 |

| Shepherdia, or Buffalo Berry | 390 |

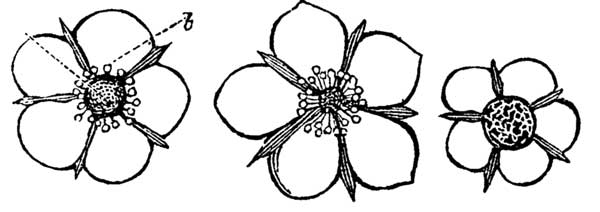

| Strawberry Blossoms | 397 |

| Fan Training (Four Illustrations) | 417, 418 |

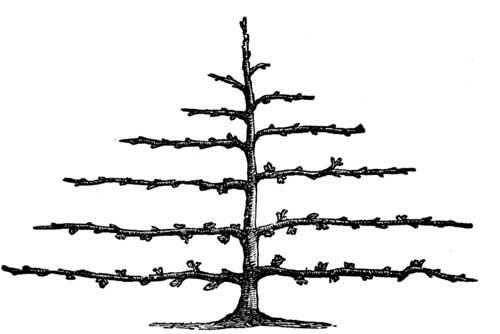

| Horizontal Training (Two Illustrations) | 419 |

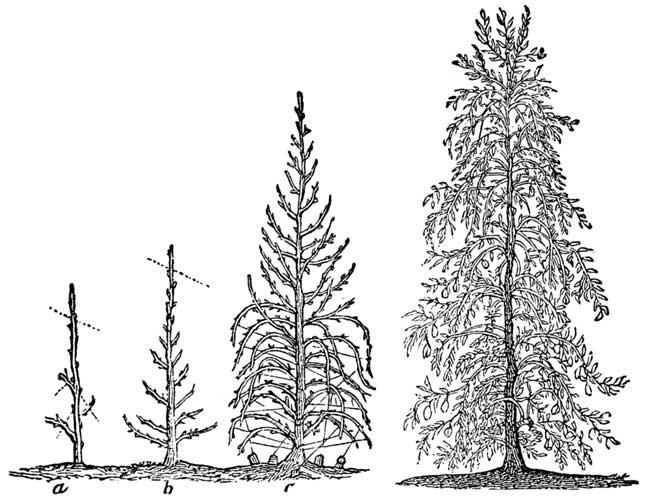

| Conical Training (Four Illustrations) | 420 |

This is the art of successfully changing fruits or plants from one climate to another. Removal to a colder climate should be effected in the spring, and to a warmer one in the fall. This may be done by scions or seeds. By seeds is better, in all cases in which they will produce the same varieties. Very few imported apple or pear trees are valuable in this country; while our finest varieties, perfectly adapted to our climate, were raised from seeds of foreign fruits and their descendants. The same is true of the extremes of this country. Baldwin apple-trees, forty or fifty years old, are perfectly hardy in the colder parts of New England; while the same imported from warmer sections of the Union fail in severe winters. This fact has given many new localities the reputation of being poor fruit-regions. When we remove fruit-trees to a similar climate in a new country, they flourish well, and we call it a good fruit-country. Remove trees from the same nursery to a different climate and soil, and they are not hardy and vigorous, and we call it a poor fruit-country. These two localities may be equally good for fruit, with suit[Pg 10]able care in acclimating the tree and preparing the soil. Thus the rich prairies of central Illinois are often said not to be adapted to fruit. Give time to raise fruits from the seed, and to apply the principles of acclimation, and those rich prairies will be among the great fruit-growing regions of the world. Two things are essential to successful fruit-culture, on all the alluvial soils of the Northwest: raise from seed, and prune closely and head-in short, and thus put back and strengthen the trees for the first ten years, and no more complaints will be heard.

The peach has been gradually acclimated, until, transplanted from perpetual summer, it successfully endures a temperature of thirty-five degrees below zero. This prince of fruits will yet be successfully grown even beyond the northern limits of Minnesota. Many vegetables may also be grown in very different climates, by annually importing the seed from localities where they naturally flourish. Sweet potatoes are thus grown abundantly in Massachusetts. We wonder this subject has received so little attention. We commend these brief hints to the earnest consideration of all practical cultivators, hoping they may be of great value in the results to which they may lead.

Almonds are natives of several parts of Asia and Africa. They perfectly resemble the peach in all but the fruit. The peach and almond grow well, budded into each other. In France, almond-stocks are pre[Pg 11]ferred for the peach. Their cultivation and propagation are in all respects the same as the peach.

Varieties.—1. Long, hard shell. This is the best for cultivation in western and middle states, and in all cold regions. Very ornamental.

2. Common sweet. Productive in middle states, but not so good as the first.

3. Ladies' thin shell. Fruit large, long, and sweet; the very best variety, but not so hardy as the first two. Grows well in warm locations, with slight protection in winter.

4. The bitter. Large, with very ornamental leaves and blossoms. Fruit bitter, and yielding that deadly poison, prussic acid.

5. Peach almond. So called from having a pulp equal to a poor peach. Not hardy in northern climates. Other varieties are named, but are of no consequence to the practical cultivator.

6. Two varieties of ornamental almonds are very beautiful in spring—the large, double flowering, and the well-known dwarf flowering. But we regard peach-blossoms quite as ornamental, and the ripe peaches much more so, and so prefer to cultivate them.

Almonds are extensively cultivated in the south of Europe, especially in Portugal, as an article of commerce. They will grow equally well in this country; but labor is so cheap in Europe, that American cultivators can not compete with it in the almond market. But every one owning land should cultivate a few as a family luxury.[Pg 12]

The original of all our apples was the wild European crab. We have in this country several native crabs larger and better than the European; but they have not yet, as we are aware, been developed into fine apples. Apple-trees are hardy and long-lived, doing well for one hundred and fifty years. Highly-cultivated trees, however, are thought to last only about fifty years. An apple-tree, imported from England, produced fruit in Connecticut at the age of two hundred and eight years. The apple is the most valuable of all fruits. The peach, the best pears, the strawberries, and others, are all delicious in their day; but apples are adapted to a greater variety of uses, and are in perfection all the year; the earliest may be used in June, and the latest may be kept until that time next year. As an article of food, they are very valuable on account of both their nutritive and medicinal qualities. As a gentle laxative, they are invaluable for children, who should always be allowed to eat ripe apples as they please, when they can be afforded. Children will not long be inclined to eat ripe fruit to their injury.

An almost exclusive diet of baked sweet apples and milk is recorded as having cured chronic cases of consumption, and other diseases caused by too rich food. Let dyspeptics vary the mode of preparing and using an apple diet, until it agrees with them, and many aggravated cases may be cured without medicine. It is strange how the idea has gained so much currency that apples, although a pleasant luxury, are not suffi[Pg 13]ciently nutritious for a valuable article of diet. There is no other fruit or vegetable in general use that contains such a proportion of nutriment. It has been ascertained in Germany, by a long course of experiments, that men will perform more labor, endure more fatigue, and be more healthy, on an apple diet, than on that universal indispensable for the poor, the potato. Apples are more valuable than potatoes for food. They are equally valuable as food for fowls, swine, sheep, cattle, and horses. Hogs have been well fattened on apples alone. Cooked with other vegetables, and mixed with a little ground grain or bran, they are an economical food for fattening pork or beef. Sweet or slightly-acid apples, fed to neat stock or horses, will prevent disease, and keep the animals in fine condition. For human food they may be cooked in a greater variety of ways than almost any other article. Apple-cider is valuable for some uses. It makes the best vinegar in general use, and, when well made and bottled, is better than most of our wines for invalids. Apple-molasses, or boiled cider, which is sweet-apple cider boiled down until it will not ferment, is excellent in cookery. Apple-butter is highly esteemed in many families. Dried apples are an important article of commerce. Green apples are also exported to most parts of the world. Notwithstanding the increased attention to their cultivation during the last half-century, their market value is steadily increasing, and doubtless will be, for the best varieties, for the next five hundred years.

It does not cost more than five or six cents per bushel to raise apples; hence they are one of the most profitable crops a farmer can raise. No farm, there[Pg 14]fore, is complete without a good orchard. The man who owns but five acres of land should have at least two acres in fruit-trees.

Soil.—Apples will succeed well on any soil that will produce good cabbages, potatoes, or Indian corn. Land needs as much manure and care for apple-trees as for potatoes. Rough hillsides and broken lands, unsuitable for general cultivation, may be made very valuable in orchards. It must be enriched, if not originally so, and kept clean about the trees. On no crop does good culture pay better. Many suppose that an apple-tree, being a great grower, will take care of itself after having attained a moderate size. Whoever observes the great and rapid growth of apple-trees must see, that, when the ground is nearly covered with them, they must make a great draft on the soil. To secure health and increased value, the deficiency must be supplied in manure and cultivation. The quantity and quality of the fruit depend mainly on the condition of the land. The kinds and proportions of manures best for an apple-orchard are important practical questions. We give a chemical analysis of the ashes of the apple-tree, which will indicate, even to the unlearned, the manure that will probably be needed:—

Analysis of the ash of the apple-tree.

| Sap-wood. | Heart-wood. | Bark of trunk. | |

| Potash | 16.19 | 6.620 | 4.930 |

| Soda | 3.11 | 7.935 | 3.285 |

| Chloride of sodium | 0.42 | 0.210 | 0.540 |

| Sulphate of lime | 0.05 | 0.526 | 0.637 |

| Phosphate of peroxyde of iron | 0.80 | 0.500 | 0.375 |

| Phosphate of lime | 17.50 | 5.210 | 2.425 |

| Phosphate of magnesia | 0.20 | 0.190 | |

| Carbonic acid | 29.10 | 36.275 | 44.830 |

| Lime | 18.63 | 37.019 | 51.578 |

| Magnesia | 8.40 | 6.900 | 0.150 |

| Silicia | 0.85 | 0.400 | 0.200 |

| Soluble silicia | 0.80 | 0.300 | 0.400 |

| Organic matter | 4.60 | 2.450 | 2.100 |

| —— | —— | —— | |

| 100.65 | 104.535 | 111.450 |

This table will indicate the application of plenty of wood-ashes and charcoal; lime in hair, bones, horn-shavings, old plaster, common lime, and a little common salt. Lime and ashes, or dissolved potash, are indispensable on an old orchard; they will improve the fruit one half, both in quantity and quality.

Propagation.—This is done mainly by seeds, budding and grafting. The best method is by common cleft-grafting on all stocks large enough, and by whip or tongue grafting on all others. (See under article, Grafting.)

Grafting into the sycamore is recommended by some. The scions are said to grow profusely, and to bear early and abundantly; but they are apt to be killed by cold winters. We do not recommend it. Almost everything does best budded or grafted into vigorous stocks of its own nature. Root-grafting, as it is termed,—that is, cutting up roots into pieces three or four inches long, and putting a scion into each—has been a matter of much discussion and diversity of opinion. It is certainly a means of most rapidly multiplying a given variety, and is therefore profitable to the nurseryman. For ourselves, we should prefer trees grafted[Pg 16] just above, or at the ground, using the whole stock for one tree. We do not, however, undertake to settle this controverted point. Our minds are fixed against it. Others must do as they please. Propagation by seed is thought to be entirely uncertain, because, as is supposed, the seeds will not reproduce their own varieties. We consider this far from being an established fact.

When grafts are put into large trees, high up from the ground, their fruit may be somewhat modified by the stock. There is also a slight tendency in the seeds of all grafts to return to the varieties from which they descended. But we believe the general rule to be, that the seeds of grafts, put in at the ground and standing alone, will generally produce the same varieties of fruit. The most prominent obstacle in the way of this reproduction is the presence of other varieties, which mix in the blossom. The planting of seeds from any mixed orchard can never settle this question, because they are never pure. Propagation by seeds, then, is an inconvenient method, only to be resorted to for purposes of acclimation. But it is so seldom we have a good bearing apple-tree so far removed from others as not to be affected by the blossoms, that we generally get from seeds a modification of varieties. Raising suitable stocks for grafting is done by planting seeds in drills thirty inches apart, and keeping clear of weeds until they are large enough to graft. The soil should be made very rich, to save time in their growth. Land where root-crops grew the previous year is the best. If kept clear of weeds, on rich, deep soil, from one to two thirds of them will be large enough for whip-grafting after the first year's growth. The pomice from the[Pg 17] cider-mill is often planted. It is better to separate the seeds, and plant them with a seed-drill. They will then be in straight, narrow rows, allowing the cultivator and hoe to pass close by them, and thus save two thirds of the cost of cultivation. The question of keeping seeds dry or moist until planting is one of some importance. Most seeds are better for being kept slightly moist until planted; but with the apple it makes no difference. Keep apple-seeds dry and spread, as they are apt to heat. Freezing them is not of the slightest importance. If you plant pomice, put in a little lime or ashes to counteract the acid. For winter-grafting, pull the seedlings that are of suitable size, cut off the tops eight inches from the root, and pack in moist sand in a cellar that will not freeze. After grafting, tie them up in bunches, and pack in tight boxes of moist sand or sawdust.

Transplanting.—This is fully treated elsewhere in this work. We give under each fruit only what is peculiar to that species. In mild climates transplant in the fall, and in cold in the spring. Spring-planting must never be done until the soil has become dry enough to be made fine. A thoroughly-pulverized soil is the great essential of successful transplanting. Trees for spring-planting should always be taken up before the commencement of vegetation. But in very wet springs, this occurs before the ground becomes sufficiently dry; it is then best to take up the trees and heel them in, and keep them until the soil is suitable. The place for an apple-tree should be made larger than for any other tree, because its roots are wide-spreading, like its branches. The earth should be thrown out to the depth of twenty inches, and four or five feet square,[Pg 18] for an ordinary-sized tree. This, however, will not do on a heavy clay subsoil, for it would form a basin to hold water and injure the tree. A ditch, as low as the bottom of the holes, should extend from tree to tree, and running out of the orchard, constructed in the usual method of drains, and, whatever be the subsoil, the trees will flourish. The usual compost to manure the trees in transplanting will be found elsewhere. In the bottom of these places for apple-trees should be thrown a plenty of cobblestones, with a few sods, and a little decaying wood and coarse manure. We know of nothing so good under an apple-tree as small stones; the tree will always be the larger and thriftier for it. This is, in a degree, beneficial to other fruits, but peculiarly so to the apple.

Size for transplanting.—Small trees usually do best. Large trees are often transplanted with the hope of having an abundance of fruit earlier. This usually defeats the object. The large trees will bear a little fruit earlier than the small ones; but the injury by removal is so much greater, that the small stocky trees come into full, regular bearing much the soonest. From five to eight feet high is often most convenient for field-orchard culture. But, wherever we can take care of them, it is better to set out smaller trees; they will do better for years. A suitable drain, extending through the orchard, under each row of trees, will make a good orchard on low, wet land.

Trimming at the time of transplanting.—Injured roots should be removed as in the general directions under Transplanting. But the idea of cutting off most of the top is a very serious error. When large trees are transplanted, which must necessarily lose many of their[Pg 19] roots in removal, a corresponding portion of the top must be separated; but in no other case. The leaves are the lungs of the tree. How shall it have vitality if most of them are removed? It is like destroying one lung and half of the other, and then expect a man to be in vigorous health. We have often seen the most of two years' growth of trees lost by such reckless pruning. If the roots are tolerably whole and sound, leave the top so. A peach-tree needs to be trimmed much closer when transplanted, because it has so many more buds to throw out leaves.

Mulching.—This is quite as beneficial to apple-trees as to all transplanted trees. Well done, it preserves a regularity of moisture that almost insures the life of the tree.

Pruning.—The tops should be kept open and exposed to the sun, the cross limbs cut out, and everything removed that shows decided symptoms of decay. The productiveness of apple-trees depends very much upon pruning very sparingly and judiciously. There are two ways to keep an open top: one is, to allow many large limbs to grow, and cut out most of the small ones, thus leaving a large collection of bare poles without anything on which the fruit can grow;—the other method is to allow few limbs to grow large, and keep them well covered with small twigs, which always bear the fruit. The latter method will produce two or three times as much fruit as the former.

The head of an apple-tree should be formed at a height that will allow a team to pass around under its branches.

Distance apart.—In a full-grown orchard, that is designed to cover the ground, the trees should be two[Pg 20] rods (thirty-three feet) apart. When it is designed always to cultivate the ground, and land is plenty, set them fifty or sixty feet apart. You will be likely always to have fine fruit, and a crop on the land beside. Our recommendation to every one is to set out all orchards, of whatever fruit, so as to have them cover the whole ground when in maturity. Among apple-trees, dwarf pears, peaches, or quinces, may be set, which will be profitable before the apples need all the ground.

Bearing years.—A cultivator may have a part of his orchard bear one year, and the remainder the next, or he may have them all bear every year. There are two reasons why a tree bears full this year and will not bear the next. One is, it is allowed to have such a superabundance of fruit to mature this year, that it has no strength to mature fruit-buds for the next, and hence a barren year; the other reason is, a want of proper culture and the specific manures for the apple. Manure highly, keep off the insects, cultivate well, and do not allow too much to remain on the trees one season, and you will have a good crop every year. But if one would let his trees take the natural course, but wishes to change the bearing year of half of his orchard, he can accomplish it by removing the blossoms or young fruit from a part of his trees on the bearing year, and those trees having no fruit to mature will put forth an abundance of buds for fruit the following season; thus the fruit-season will be changed without lessening the productiveness. Go through a fruit-region in what is called the non-bearing seasons, and you will find some orchards and some trees very full of fruit. Trees of the same variety in another orchard near by will have very little fruit. This shows that the bearing season[Pg 21] is a matter of mere habit, in all except what is determined by late frosts. This fact may be turned to great pecuniary value, by producing an abundance of apples every year.

Plowing and pasturing.—An apple-orchard should be often plowed, but not too deep among the roots. When not actually under the plow, it should be pastured, with fowls, calves, or sheep. Swine are recommended, as they will eat all the apples that fall prematurely, and with them the worms that made them fall. But we have often seen hogs, by their rooting and rubbing, kill the trees. Better to pick up the apples that fall too early, and give them to the swine. Turkeys and hens in an orchard will do much to destroy the various insects. They may be removed for a short time when they begin to peck the ripening fruit.

Orchards pastured by sheep are said not to be infested with caterpillars. Sheep pastured and salted under apple-trees greatly enrich the soil, and in those elements peculiarly beneficial.

Enemies.—There are several of these that are quite destructive, when not properly guarded against. Two things are necessary, and, united and thoroughly performed, they afford a remedy or a preventive for most of the depredations of all insects: 1. Keep the trees well cleared of all rough, loose bark, which affords so many hiding-places for insects.

2. Wash the trunks and large limbs of the trees, twice between the 25th of May and the 15th of August, with a ley of wood-ashes or dissolved potash. Apple-trees will bear it strong enough to kill some of the finest cherries. We add another very effectual wash. Let cultivators choose between the two. Into two gal[Pg 22]lons of water put two quarts of soft-soap and one fourth pound of sulphur. If you add tobacco-juice, or any other very offensive article, it will be still better.

Apple-worm.—The insect that produces this worm lays its egg in the blossom-end of the young apple. That egg makes a worm that passes down about the core and ruins the fruit. Apples so affected will fall prematurely, and should be picked up and fed to swine. This done every day during their falling, which does not last a great while, will remedy the evil in two seasons. The worm that crawls from the fallen apple gets into crevices in rough bark, and spins his cocoon, in which he remains till the following spring.

Bonfires, for a few evenings in the fore part of June, in an orchard infested with moths, will destroy vast numbers of them, before they have deposited their eggs. This can not be too strongly insisted upon.

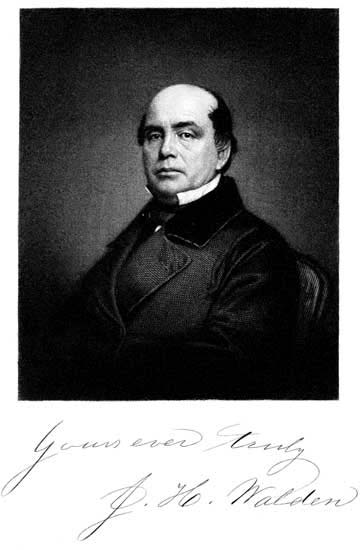

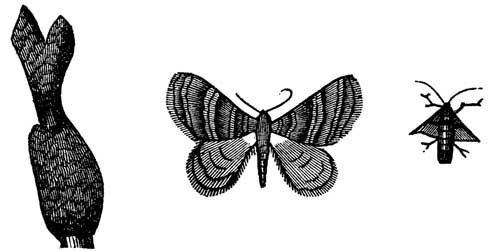

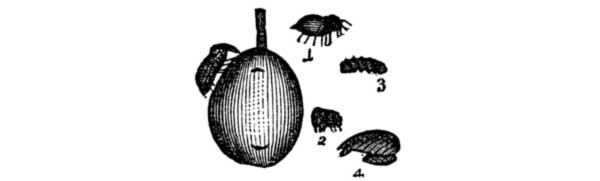

Apple-Worms.

a The young worm. b The full-grown worm. c The same magnified. d

Cocoon. e Chrysalis.

Apple-Worms.

a The young worm. b The full-grown worm. c The same magnified. d

Cocoon. e Chrysalis.Bark-louse.—Dull white, oval scales, one tenth of an inch long, which sometimes appear on the stems of trees in vast numbers, may be destroyed by the wash recommended above.

Woolly aphis—called in Europe by the misnomer, American blight—is very destructive across the water, but does not exist extensively on this side. It is supposed to exist, in this country, only where it has been introduced with imported trees. It appears as a white downy substance in the small forks of trees. This is composed of a large number of very minute woolly lice, which increase with wonderful rapidity. They are easily destroyed by washing with diluted sulphuric acid—three fourths of an ounce, by measure, from the druggist's—and seven and a half ounces of water, applied by a rag tied to the end of a stick. The operator must keep it from his clothes. After the first rain this is perfectly effectual.

Apple-tree borer.—This is a fleshy-white grub, found in the trunks of the trees. It enters at the surface of the ground where the bark is tender, and either girdles or thoroughly perforates the tree, causing its death. This is produced by a brown and white striped beetle about half an inch long. It does not go through its different stages annually, but remains a grub two or three years. It finally comes out in its winged state, early in June, flying in the night and laying its eggs. If the borers are already in the tree, they may be killed by cutting out, or by a steel wire thrust into their holes. But better prevent them. This can be done effectually by placing a small mound of ashes or lime around each tree early in the spring.

On nursery-trees their attacks may be prevented by[Pg 24] washing with a solution of potash—two pounds in eight quarts of water. As this is a good manure, as well as a great remedy for insects, it had better be used every season.

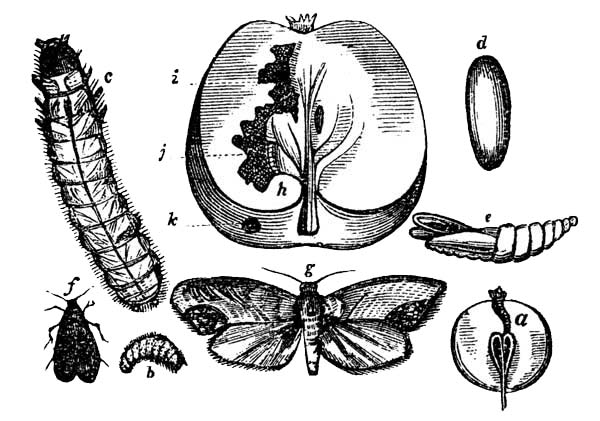

| Borer, | Eggs. | Beetle. |

Caterpillars are the product of a miller of a reddish-brown color, measuring about an inch and a half when flying. They deposit many eggs about the forks and near the extremities of young branches. These hatch in spring, in season for the young foliage, on which they feed voraciously. When neglected for two or three years, they often defoliate large trees. The habits of the caterpillar are favorable to their destruction. They weave their webs in forks of trees, and are always at home in rainy weather, and in the morning till nine o'clock. The remedy is to kill them. This is most effectually done by a sponge on the end of a pole, dipped in strong spirits of ammonia. Each one touched by it is instantly killed, and it is not difficult to reach them all. They may also be rubbed off with a brush or swab on the end of a pole, and burned. The principle is to get them off, web and all, and destroy them. This can always be effectually done, if attended to early in the season, and early in the morning. If any have been missed, and come out in insects to deposite more[Pg 25] eggs, bonfires are most effectual. These should be made of shavings, in different parts of the orchard, and about the middle of June, earlier or later, according to latitude and season. The ends of twigs on which the eggs are laid in bunches of hundreds (see figure), may be cut off in the fall and destroyed. As this can be done with pruning-shears, it may be an economical method of destroying them.

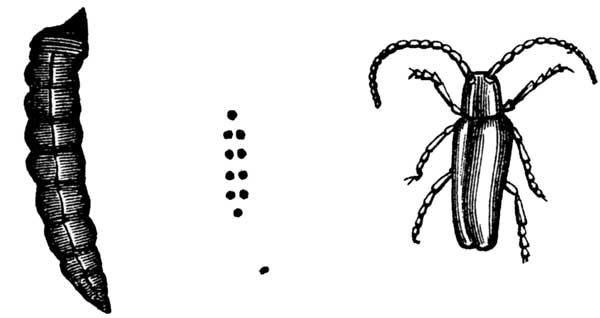

Caterpillar Eggs. Canker-worm Moths, Male and Female.

Caterpillar Eggs. Canker-worm Moths, Male and Female.

Canker-worm.—The male moth has pale-ash colored wings, with a black dot, and is about an inch across. The female has no wings, is oval in form, dark-ash colored above, and gray underneath. These rise from the ground as early in spring as the frost is out. Some few rise in the fall. The females travel slowly up the body of the tree, while the winged males fly about to pair with them. Soon you may discover the eggs laid, always in rows, in forks of branches and among the young twigs. Every female lays nearly a hundred, and covers them over carefully with a transparent, waterproof glue. The eggs hatch from May 1st to June 1st, according to the latitude and season, and come out an ash-colored worm with a yellow stripe. They are very voracious, sometimes entirely stripping an orchard of[Pg 26] its foliage. At the end of about four weeks they descend to the ground, to remain in a chrysalis state, about four inches below the surface, until the following spring. These worms are very destructive in some parts of New England, and have been already very annoying, as far west as Iowa. They will be likely to be transported all over the country on young trees. Many remedies are proposed, but to present them all is only to confuse. The best of anything is sufficient. We present two, for the benefit of two classes of persons. For all who have care enough to attend to it, the best remedy is to bind a handful of straw around the tree, two feet from the ground, tied on with one band, and the ends allowed to stand out from the tree. The females, who can not fly, but only ascend the trunk by crawling, will get up under the straw, and may easily be killed, by striking a covered mallet on the straw, and against the tree below the band. This should be attended to every day during the short season of their ascent, and all will be destroyed. Burn the straw about the last of May. But those who are too indolent or busy to do this often till their season is past, may melt India-rubber over a hot fire, and smear bandages of cloth or leather previously put tight around the tree. This will prevent the female moth from crossing and reaching the limbs. Tar is used, but India-rubber is better, as weather will not injure it as it will tar, so as to allow the moth to pass over. Put this on early and well, and let it remain till the last of May. But the first, the process of killing them, is far the best.

Gathering-and preserving.—All fruit, designed to be kept even for a few weeks, should be picked, and not shaken off, and laid, not dropped into a basket, and[Pg 27] with equal care put into the barrels in which it is to be kept or transported. The barrel should be slightly shaken and filled entirely full. Let it stand open two days, to allow the fruit to sweat and throw off the excessive moisture. Then head up tight, and keep in a cool open shed until freezing weather; then keep where they can occasionally have good air, and in as cool a place as possible, without danger of freezing. Of all the methods of keeping apples on shelves, buried as potatoes, in various other articles, as chaff, sawdust, &c., this is, on the whole, the best and cheapest. Wrapping the apples in paper before putting them into the barrels, may be an improvement. Apples gathered just before hard frosts, or as they are beginning to ripen, but before many have fallen from the trees, and packed as above, and the barrels laid on their sides in a good dry, dark cellar, where air can occasionally be admitted, can be kept in perfection from six to eight weeks, after the ordinary time for their decay. Apples for cider, or other immediate use, may be shaken off upon mats or blankets spread under the tree for that purpose. They are not quite so valuable, but it saves times in gathering.

Varieties are exceedingly numerous and uncertain. Cole estimates that two millions of varieties have been produced in the single state of Maine, and that thousands of kinds may there be found superior to those generally recommended in the fruit-books. The minute description of fruits is not of the least use to one out of ten thousand cultivators. The best pomologists differ in the names and descriptions of the various fruits. Some varieties have as many as twenty-five synonyms. Of what use, then, is the minute description of the hundred[Pg 28] and seventy-seven varieties of Cole's American fruit-book, or of the vast numbers described by Downing, Elliott, Barry, and Hooper? The best pear we saw in Illinois could not be identified in Elliott's fruit-book by a practical fruit-grower. We had in our orchard in Ohio a single apple-tree, producing a large yield of one of the very best apples we ever saw; it was called Natural Beauty. We could not learn from the fruit-books what it was. We took it to an amateur cultivator of thirty years' experience, and he could not identify it. This is a fair view of the condition of the nomenclature of fruits. The London experimental gardens are doing much to systemize it, and the most scientific growers are congratulating them on their success. But it never can be any better than it is now. Varieties will increase more and more rapidly, and synonyms will be multiplied annually, and the modification of varieties by stocks, manures, climates, and location, will render it more and more confused.

We can depend only upon our nurserymen to collect all improved varieties, and where we do not see the bearing-trees for ourselves, trust the nurseryman's description of the general qualities of fruit. Seldom, indeed, will a cultivator buy fruit-trees, and set out his orchard, and master the descriptions in the fruit-books, and after his trees come into bearing, minutely try them by all the marks to see whether he has been cheated, and, if so, take up the trees and put out others, to go the same round again, perhaps with no better success. Hence, if possible, let planters get trees from a nursery so near at hand that they may know the quality of the fruit of the trees from which the grafts are taken, get the most popular in their vicinity, and always[Pg 29] secure a few scions from any extraordinary apple they may chance to taste. It is well, also, to deal only with the most honorable nurserymen. Remember that varieties will not do alike well in all localities. Many need acclimation. Every extensive cultivator should keep seedlings growing, with a view to new varieties, or modifications of old ones, adapted to his locality.

We did think of describing minutely a few of the best varieties, adapted to the different seasons of the year. But we can see no advantage it would be to the great mass of cultivators, for whom this book is designed. Those who wish to acquaint themselves with those descriptions will purchase some of the best fruit-books. We shall content ourselves with giving the lists, recommended by the best authority, for different sections, followed by a general description of the qualities of a few of the best. Downing's lists are the following:—

| Early Harvest. | Vandevere of New York. |

| Red Astrachan. | Jonathan. |

| Early Strawberry. | Melon. |

| Summer Rose. | Yellow Bellflower. |

| William's Favorite. | Domine. |

| Primate. | American Golden Russet. |

| American Summer Pearmain. | Cogswell. |

| Garden Royal. | Peck's Pleasant. |

| Jefferis. | Wagener. |

| Porter. | Rhode Island Greening. |

| Jersey Sweet. | King of Tompkins County. |

| Large Yellow Bough. | Swaar. |

| Gravenstein. | Lady Apple. |

| Maiden's Blush. | Ladies' Sweet. |

| Autumn Sweet Bough. | Red Canada. |

| Fall Pippin. | Newtown Pippin. |

| Mother. | Boston Russet. |

| Smokehouse. | Northern Spy. |

| Rambo. | Wine Sap. |

| Esopus Spitzenburg. | Baldwin. |

| Red Astrachan. | Fameuse. |

| Early Sweet Bough. | Pomme Gris. |

| Saps of Wine or Bell's Early. | Canada Reinette. |

| Golden Sweet. | Golden Ball. |

| William's Favorite. | St. Lawrence. |

| Porter. | Jewett's Fine Red. |

| Dutchess of Oldenburgh. | Rhode Island Greening. |

| Keswick Codlin. | Baldwin. |

| Hawthornden. | Winthrop Greening. |

| Gravenstein. | Danvers Winter-Sweet. |

| Mother. | Ribston Pippin. |

| Tolman Sweet. | Roxberry Russet. |

| Yellow Bellflower. |

Made up from the contributions of twenty different cultivators, from five Western states.[Pg 31]

| Early Harvest. | Domine. |

| Carolina Red June. | Swaar. |

| Red Astrachan. | Westfield Seek-no-further. |

| American Summer Pearmain. | Broadwell. |

| Sweet June. | Vandevere of New York, or Newtown Spitzenburg. |

| Large Sweet Bough. | Ortly, or White Bellflower. |

| Summer Queen. | Yellow Bellflower. |

| Maiden's Blush. | White Pippin. |

| Keswick Codlin. | American Golden Russet. |

| Fall Wine. | Herfordshire Pearmain. |

| Rambo. | White Pearmain. |

| Belmont. | Wine Sap. |

| Fall Pippin. | Rawle's Janet. |

| Fameuse. | Red Canada. |

| Jonathan. | Willow Twig. |

| Tolman Sweet. |

| Early Harvest. | Nickajack. |

| Carolina Juice. | Maverack's Sweet. |

| Red Astrachan. | Batchelor or King. |

| Gravenstein. | Buff. |

| American Summer Pearmain. | Shockley. |

| Julian. | Ben Davis. |

| Mangum. | Hall. |

| Fall Pippin. | Mallecarle. |

| Maiden's Blush. | Horse. |

| Summer Rose. | Bonum. |

| Porter. | Large Striped Pearmain. |

| Rambo. | Rawle's Janet. |

| Large Early Bough. | Disharoon. |

| Fall Queen, or Ladies' Favorite. | Meigs. |

| Oconee Greening. | Camack's Sweet. |

| Cullasaga. |

Some varieties are included in all these lists, showing that the best cultivators regard some of our finest[Pg 32] apples as adapted to all parts of the country. A careful comparison of Hooper's lists, as recommended by the best Western cultivators, whose names are there mentioned, will show that they name the same best varieties, with a few additions.

We have carefully examined the varieties recommended by Ernst, by Kirtland and Elliott, by Barry, and by the national convention of fruit-growers, and find a general agreement on the main varieties. There are some differences of opinion, but they are minor. They have left out some of Downing's list, and added some, as a matter of course. All this only goes to show the established character of our main varieties. Out of all these, select a dozen of those named, in most of the lists, and you will have all that ever need be cultivated for profit. The best six might be still better. Yet, in your localities, you will find good ones not named in the books, and new ones will be constantly rising.

Downing adds that "Newtown Pippin does not succeed generally at the West, yet in some locations they are very fine. Rhode Island Greening and Baldwin generally fail in many sections, while in others they are excellent."

Now, it is contrary to all laws of vegetation and climate, that a given fruit should be good in one county and useless in the next, if they have an equal chance in each place. A suitable preparation of the soil, in supplying, in the specific manures, what it may lack, getting scions from equally healthy trees, and grafting upon healthy apple-seedling stocks—observing our principles of acclimation—and not one of our best apples will fail, in any part of North America.[Pg 33]

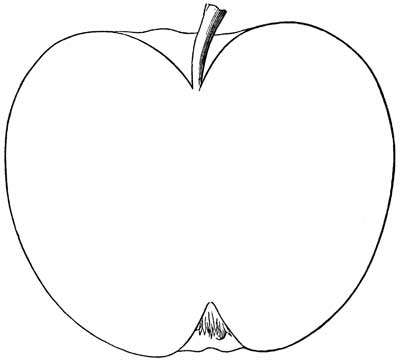

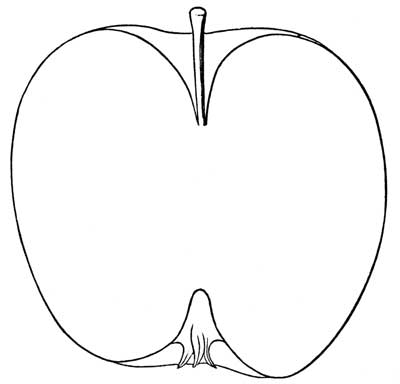

On a given parallel of latitude, a man may happen to plant a tree upon a fine calcareous soil, and it does well. Another chances to plant one upon a soil of a different character, and it does not succeed. It is then proclaimed that fruit succeeds well in one locality, and is useless in another near by and in the same latitude. The truth is, had the latter supplied calcareous substances to his deficient soil, as he might easily have done, in bones, plaster, lime, &c., the fruit would have done equally well in both cases. We should like to see this subject discussed, as it never has been in any work that has come under our observation. It would redeem many a section from a bad reputation for fruit-growing, and add much to the luxuries of thousands of our citizens. Apples can be successfully and profitably grown on every farm of arable land in North America. We present, in the following cuts, a few of our best apples, in their usual size and form. Some are contracted for the want of room on the page. We shall describe a few varieties, in our opinion the best of any grown in this country. These are all that need be cultivated, and may be adapted to all localities. We lay aside all technical terms in our description, which we give, not for purposes of identification, but to show their true value for profitable culture. The quality of fruit, habits of the tree, and time of maturity, are all that are necessary, for any practical purpose.

Nickajack.—Synonyms—Wonder, Summerour.

Origin, North Carolina. Tree vigorous, and a constant prolific bearer. Fruit large, skin yellowish, shaded land striped with crimson, and sprinkled with lightish dots. Yellowish flesh, fine subacid flavor. Tender, crisp, and juicy. Season, November to April.[Pg 34]

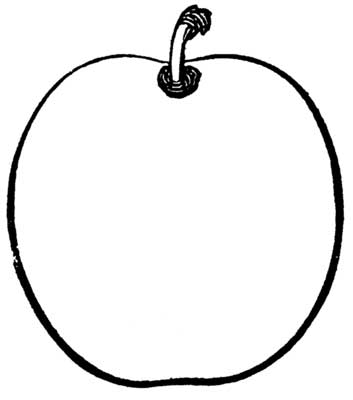

Baldwin.—Synonyms—Late Baldwin, Woodpecker, Pecker, Steele's Red Winter.

Stands at the head of all apples, in the Boston market. Fruit large and handsome. Tree hardy, and an abundant bearer. It is of the family of Esopus Spitzenburg. Yellowish white flesh, crisp and beautiful flavor, from a mingling of the acid and saccharine. Season, from November to March. On some rich western soils, it is disposed to bitter rot, which may be easily prevented, by application to the soil of lime and potash.

Canada Red.—Synonyms—Old Nonsuch, Richfield Nonsuch, Steele's Red Winter.

An old fruit in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Tree[Pg 35] not a great grower, but a profuse bearer. Good in Ohio, Michigan, and other Western states. Retains its fine flavor to the last. January to May.

Bellflower.—Synonyms—Yellow Bellflower, Lady Washington, Yellow Belle-fleur.

Fruit very large, pale lemon yellow, with a blush in the sun. Subacid, juicy, crisp flesh. Tree vigorous, regular and excellent bearer. Season, November to March. Highly valuable.[Pg 36]

Early Harvest.—Synonyms—Early French Reinette, Prince's Harvest, July Pippin, Yellow Harvest, Large White Juneating, Tart Bough.

The best early apple. Bright straw color. Subacid, white, tender, juicy, and crisp. Equally good for cooking and the dessert. Season, the whole month of July in central New York; earlier south, and later north, as of all other varieties.

Red Astrachan.—Brought to England from Sweden in 1816. One of the most beautiful apples in the whole list. Fruit very large, and very smooth and fair. Color deep crimson, with a little greenish yellow in the shade and occasionally a little russet near the stalk. Flesh white and crisp, rich acid flavor. Gather as soon as nearly ripe, or it will become mealy. Abundant bearer. July and August.[Pg 37]

Esopus Spitzenburg.—Synonym—True Spitzenburg.

Large, fine flavored, lively red fruit. It is everywhere well known, as one of the very best apples ever cultivated, both for cooking and the desert. December to February, and often good even into April. A very great bearer.

King of Tompkins County.—Synonym—King Apple.

This is an abundant annual bearer. Skin rather yellowish, shaded with red and striped with crimson. Flesh rather coarse, but juicy and tender, with a very agreeable vinous aromatic flavor. One of the best. December and March.[Pg 38]

Rhode Island Greening.—Synonyms—Burlington Greening, Jersey Greening, Hampshire Greening.

A universal favorite, everywhere known. Acid, lively, aromatic, excellent alike for the dessert and kitchen. Great bearer. November to March. It is said to fail on some rich alluvial soils at the West. Avoid root grafting, and apply the specific manures, and we will warrant it everywhere.

Bonum.—Synonym—Magnum Bonum.

From North Carolina. Fruit large, from light to dark red. Flesh yellow, subacid, rich, and delicious. Tree hardy, vigorous, and an early and abundant bearer.

American Golden Russet.—Synonyms—Sheep Nose, Golden Russet, Bullock's Pippin, Little Pearmain.

The English Golden Russet is a variety cultivated in this country, but much inferior to the above. The[Pg 39] fruit is small, but melting juicy, with a very pleasant flavor. It is one of the most regular and abundant bearers known. Tree hardy and thrifty. October to January. We know from raising and using it at the West, that it is one of the very best.

Pippin, Fall.—Confounded with Holland Pippin and several other varieties.

A noble fruit, unsurpassed by any other autumn apple. Very large, equally adapted to table and kitchen. Fine yellow, when fully ripe, with a few dots. Flesh is white, mellow, and richly aromatic. October and December. A fair bearer, though not so great as many others.[Pg 40]

Newtown Pippin.—Synonyms—Green Newtown Pippin, Green Winter Pippin, American Newtown Pippin, Petersburg Pippin.

This is put down as the first of all apples. It commands the highest price, in the London market. It keeps long without the least shriveling or loss of flavor. Fruit medium size, olive green, with small gray specks. Flesh greenish white, juicy, crisp, and of an exceedingly delicious flavor. The best keeping apple, good for eating from December to May.

The yellow pippin, is another variety nearly as good.

Porter.—A Massachusetts fruit, very fair; a very great bearer. Is a favorite in Boston. Deserves general cultivation. September and into October.

Smokehouse.—Synonyms—Mill Creek Vandevere, English Vandevere.

An old variety from Pennsylvania, where the original[Pg 41] tree grew by a gentleman's smoke-house; hence its name. Skin yellow, shaded with crimson, sprinkled with large gray or brown dots. September to February. One of the very best for cooking.

Rambo.—Synonyms—Romanite, Bread and cheese apple, Seek-no-further.

This is a great fall apple. Medium size, flat, yellowish white in the shade, and marbled with pale yellow and red in the sun, and speckled with large rough dots. Flesh greenish white, rich, subacid. October to December.

Canada Reinette.—This has ten synonyms in Europe, which indicates its popularity. In this country it is known only under the above name. Fruit of the very largest size. A good bearer. The quality is in all respects good. Lively, subacid flavor. December to April, unless allowed to hang on the tree too long. Pick early in the fall.[Pg 42]

Rome Beauty.—Synonyms—Roman Beauty, Gillett's Seedling.

Fruit large, yellow, ground shaded, and striped with red, and sprinkled with little dots. Flesh yellowish, juicy, tender, subacid. Bears every year a great crop of very large showy apples. It is not superior in flesh or flavor, but keeps and sells very well. Always must be very profitable, and hence very popular.

Autumn Sweet Bough.—Synonyms—Late Bough, Fall Bough, Summer Bell Flower, Philadelphia Sweet.

Tree very vigorous and productive. Fruit medium. Skin smooth, pale yellow with a few brown dots. Flesh white, tender, sweet vinous flavor. One of the best dessert sweet apples. August and October.[Pg 43]

Westfield Seek-no-further.—Synonyms—Seek-no-further, Red Winter Pearmain, Connecticut Seek-no-further.

Fruit large, pale dull red, sprinkled with obscure russety yellow dots. Flesh white, tender and fine-grained. On all accounts good. October to February according to Downing. Elliott says from December to February. But the doctors often disagree. So you had better eat your apples when they are good, whether it be October or December, or according to Downing, Elliott, or Hooper.

Ribston Pippin.—Synonyms—Glory of York, Travers', Formosa Pippin, Rock hill's Russet.

This occupies as high a place in England, as any other apple. In this country, two or three others, as Baldwin and Newtown Pippin, are more highly es[Pg 44]teemed. This is most successfully grown in the colder parts of the United States and Canada. Fruit medium, deep yellow, firm, crisp; flavor sharp aromatic. November to April.

Northern Spy.—This is a new American variety, with no synonyms. It originated near Rochester, N. Y.

There is not a better dessert apple known. It retains its exceedingly pleasant juiciness, and excellent flavor from January to June. In western New York, they have been carried to the harvest field, in July in excellent condition. A fair bearer of beautiful fruit. Subacid with a peculiar freshness of flavor. Dark stripes of purplish red in the sun, but a greenish pale yellow in the shade. High culture and an open top for admission of the sun, affects the fruit more favorably than any other.[Pg 45]

Roxbury Russet.—Synonyms—Boston Russet, Putnam Russet.

An excellent fruit, and prodigious bearer. Medium size, flesh greenish white, rather juicy, and subacid. Good in January, and one of the best in market in June.

There are other russets of larger size, but much inferior. This should be in every collection. It is not first in richness and flavor, but it is superior to most in productiveness, and is one of the best keepers.

Large Yellow Bough.—Synonyms—Early Sweet Bough, Sweet Harvest, Bough.

No harvest-apple equals this, except the Early Harvest. Excellent for the dessert, but rather sweet for pies and sauce. Fruit above medium. Tree a moderate grower, but a profuse bearer. Flesh white and very tender. Very sweet and sprightly. July and August. Should have a place, even in a small collection.[Pg 46]

Swaar.—One of the best American fruits. Its name in Dutch, where it originated on the Hudson River, means heavy.

Fruit is large, and when fully ripe, of a dead gold color, dotted with many brown specks. Flesh yellowish, fine grained, and tender. Flavor aromatic and exceedingly rich. Bears good crops. December to March.

Winesap.—This is one of the best apples for cider, and good also for the table and kitchen. Fruit hangs long on the tree without injury. It is very productive, and does well on a variety of soils. Very fine in the West. Yellow flesh, very firm, and high flavored. November to May. Deservedly, a very popular orchard variety.[Pg 47]

Maiden's Blush.—A comparatively new variety from New Jersey. Remarkably beautiful. Admired as a dessert fruit, and equally good for the kitchen and for drying. Clear lemon yellow, with a blush cheek, sometimes a brilliant red cheek. Rapid growing tree, with a fine spreading head, bearing most abundantly. August and October.

Ladies' Sweeting.—The finest sweet apple, for dessert in winter, that has yet been produced. Skin smooth and nearly covered with red, in the sun. Flesh is greenish white, very tender, juicy, and crisp. Without any shriveling or loss of flavor, it keeps till May. So good a winter and spring sweet apple is a desideratum in any orchard or garden.[Pg 48]

The foregoing are all that any practical cultivator will need. Most will select from our list, perhaps half a dozen, which will be all they wish to cultivate. From our descriptions, which are not designed to enable planters to identify the varieties, but to ascertain their qualities, any one can select such as he prefers. And they are so generally known, that there will be but little danger of getting varieties, different from those ordered.

We subjoin, from Hooker's excellent Western Fruit-Book, the following—

"The following list," says Hooker, "contains a catalogue of the most popular varieties of apples, recommended by various pomological societies of the United States for the Western states." These varieties can be obtained of all respectable nurserymen. The list may be of use to some cultivators in the different states mentioned. The general qualities of the best of these will be found in our descriptions under the cuts:—

For the value of these varieties, in the states mentioned, you have the authority of the best pomological societies. The several states are mentioned so fre[Pg 50]quently, that it will be seen that most of them are adapted to all the states. Attend to acclimation and manure, and guard against insects, and they will all flourish, in all parts of the West and of the Union.

This is a fruit about half-way between a peach and a plum. The stone is like the plum, and the flesh rather more like the peach. It is esteemed, principally, because it comes earlier in the season than anything else of the kind.

It is used as a dessert-fruit, for preserving, drying, and various purposes in cookery. It does well on plum-stock, and best in good deep, moist loam, manured as the peach and plum. The best varieties produce their like from the seed. Seedlings are more hardy than any grafted trees. Grafts on plums are much better than on the peach. The latter seldom produce good hardy, thrifty trees, although many persist in trying them. The apricot is a favorite tree for espalier training against walls and fences, in small yards, where it bears luxuriantly. It also makes a good handsome standard tree for open cultivation.

It is as much exposed to depredations from curculio as the plum, and must be treated in the same way. Cultivation same as peach. It produces its fruit, like the peach, only on wood of the previous year's growth; hence it must be pruned like the peach. Especially must it be headed in well, to secure the best crop.

Varieties are quite numerous, a few of which only[Pg 51] deserve cultivation. Any of the nine following varieties are good:—

Brown's Early.—Yellow, with red cheek. A very productive, great grower.

Newhall's Early.—Bright-orange color, with deep-red cheek. A good cling-stone variety, every way worthy of cultivation.

Moorpark.—Yellow, with ruddy cheek. An enormous bearer, though of slow growth. It is a freestone variety of English origin, and needing a little protection in our colder latitudes.

Dubois' Early Golden.—Color, pale-orange. Very hardy and productive. In 1846, the original tree at Fishkill, N. Y., bore ninety dollars' worth of fruit.

Large Early.—Orange, but red in the sun. An excellent, early, productive variety.

Hemskirke.—Bright-orange, with red cheek. An English variety, vigorous tree, and good bearer.

Peach.—Yellow, with deep-brown on the sun-side. An excellent French variety.

Breda.—Deep-orange, with blush spots in the sun. A vigorous, productive, African variety.

Roman.—Pale-yellow, with occasionally red dots. Good for northern latitudes.

From these, planters may select those that best suit their localities and fancy. They are a little liable to be frost-bitten in the blossoms, as they bloom very early. Otherwise they are always very productive. They are ornamental, both in the leaf and in the blossom. Eaten plain, before thoroughly ripe, they are not healthy; otherwise, harmless and delicious. Every garden should have half a dozen.[Pg 52]

There are two plants known by this name. The Jerusalem artichoke, so called, not from Jerusalem in Palestine, but a corruption of the Italian name which signifies the tuber-rooted sunflower. The tubers are only used for pickling. They make a very indigestible pickle, and the plant is injurious to the garden, so they had better not be raised.

The artichoke proper grows something like a thistle, bearing certain heads, that, at a particular stage of their growth, are fine for food.

The soil should be prepared as for asparagus, only fifteen inches deep will do well. The plot of ground should be where the water will not stand on it at any time in the winter, as it will on most level gardens. This will kill the roots. When a new bed is made with slips from old plants, carefully separate vigorous shoots, remove superfluous leaves, plant five inches deep in rows five feet apart, and two feet apart in the rows. Keep very clean of weeds. The first year, some pretty good, though not full-sized heads will be produced. Plant fresh beds each year, and you will have good heads from July to November. Small heads will grow out along the stalk like the sunflower. Remove most of these small ones when they are about the size of hens' eggs, and the others will grow large. When the scales begin to diverge, but before the blossoms come out, is the time to cut them for use. Lay brush over them to prevent suffocation, and cover with straw in winter, to protect from severest cold. Too much warmth, however, is more injurious than frost.[Pg 53]

Spring-dress much like asparagus. Remove from each plant all the stocks but two or three of the best. Those removed are good for a new bed. A bed, properly made, will last four or five years.

To save seed, bend down a few good heads, so as to prevent water from standing in them; tie them to a stake, until the seed is matured. But, like Early York cabbage, imported seed is better. The usual way of serving them is, the full heads boiled. In Italy the small heads are cut up, with oil, salt, and pepper. This vegetable would be a valuable accession to American kitchen gardens.

Are one of the best applications to the soil, for almost all plants. Leeched ashes are a valuable manure, but not equal to unleached. Few articles about a house or farm should be saved with greater care. Be as choice of them as of your small change. They are worth three times as much on the land as they can be sold for other purposes. On corn, at first hoeing, they are nearly equal to plaster. On onions and vines, they promote the growth and keep off the insects. Sprinkle on dry, when plants are damp, but not too wet. Do not put wet ashes on plants, or water while the ashes are on. It will kill them. Mix ashes and plaster with other manures, and their power will be greatly increased. Mixed in manure of hot-beds, they accelerate the heat. On sour land they are equal to lime for correcting the acidity.[Pg 54]

This is a universal favorite in the vegetable garden. By the application of sand and compost, the soil should be kept loose, to allow the sprouts to spring easily from the crowns. Propagation is best effected by seed, transplanting after one year's growth. Older roots divided and transplanted are of some value, but not equal to young roots, nor will they last as long.

Preparation of the soil for an asparagus-bed is most important to success. Dig a trench on one edge of the plat designed for the bed, and the length of it, eighteen inches wide and two feet deep. Put in the bottom one foot of good barn-yard manure, and tread down. Then spade eighteen inches more, by the side of and as deep as the other, throwing the soil upon the manure in the trench. Fill with manure and proceed as before, and so until the whole plat has been trenched; then wheel the earth from the first ditch to the other side and fill into the last trench, thus making all level. If there is danger that water will stand in the bottom, drain by a blind ditch. If this is objected to as too expensive, let it be remembered that such a bed, with a little annual top-dressing, will be good for twenty years, which is the age at which asparagus-plants begin to deteriorate; then a new bed should be ready to take its place.

Planting.—Mark the plat into beds five feet wide, leaving paths two feet wide between them. In each bed put four rows lengthwise, which will be just fifteen inches apart, and set plants fifteen inches apart in the row. Dig a trench six inches wide and six inches deep[Pg 55] for each row; put an inch of rich mould in the bottom; set the plants on the mould, with the roots spread naturally, with the ends pointing a little downward. Be very particular about the position of the roots. Fill the trench, and round it up a little with well-mixed soil and fine manure. The bed is then perfect, and will improve for many years.

After-Culture.—In the fall, after the frost has killed the stalks, cut them down and burn them on the bed. Cover the bed with fine rotted manure, to the depth of two inches, and one half-bushel salt to each square rod. As soon as frost is out in spring, with a fork work the top-dressing into the soil to the depth of four inches, and stir the soil to the depth of eight inches between the rows, using care not to touch the crowns of the roots with the fork.

Cutting should never be performed until the third year. Set out the plants when one year old, let them grow one year in the bed, and the next year they will be fit to cut. Cut all the shoots at a suitable age, up to the last days of June. The shoots should be regularly cut just below the surface, when they are four or six inches high. If you are tempted to cut after the 25th of June, leave two or three thrifty shoots to each root, to grow up for seed, or you will weaken the plants, and they will die in winter. This is the reason why so many vacancies are seen in many asparagus beds. This plant may be forced in hotbeds, so as to yield an abundance of good shoots long before they will start in the open air, affording an early luxury to those who can afford it.

This vegetable is equal or superior to green peas, and by taking all the pains recommended above, in[Pg 56] the beginning, an abundance can be raised for twenty years, on the same bed, at a very trifling cost. Early radishes and other vegetables can be raised, between the rows, without any harm to the asparagus.

This is a medicinal plant, very useful, and easily raised. A strong infusion of the leaves, drank freely for some time by a nervous, hypochondriacal person, is, perhaps, better than any other medicine. It is also good in flatulency and fevers.

Its propagation is by slips or roots. It is perennial, affording a supply for many years. Gather just as the blossoms are appearing, and dry quickly in a slow oven, or in the shade. Press and do up in white papers, and keep in a tight, dry drawer, until needed for use.

Barberries.

Barberries.

A prickly shrub, from five to ten feet high, growing wild in this

country and in Europe, on poor, hard soils, or in moist situations, by

walls, stones, or fences.

Its propagation is by seeds, suckers, or offshoots.

This shrub is used for jellies, tarts, pickles, &c. Preserves made of equal parts of barberry and sweet apples, or outer-part of fine water-melons, are very superior. It is also one of the best shrubs for hedge.

The bark has much of the tannin principle, and with[Pg 57] the wood, is used for coloring yellow. Shrub, blossoms, and fruit, are quite ornamental, forming a beautiful hedge, but rather inclined to spread. Will do well on any land and in any situation. The discussion in New England about its blasting contiguous fields of grain, is about as sensible as the old witchcraft mania. Every garden should have two or three.

Does best on land which was hoed the previous year. If properly tilled, such land is rich, free from weeds, and easily pulverized. Sod, plowed deep in the fall, rolled early in the spring, well harrowed, the seed sown and harrowed in, and all rolled level, will produce a good crop. Two bushels of seed should be sowed on an acre, unless the land be very rich; in that case, one half-bushel less. Essential to a good crop is rain about the time of heading and filling. Hence early sowing is always surest. In many parts of the country it is of little use to sow barley, unless it be gotten in VERY EARLY. In not more than one season in twelve can you get a good crop of barley from late sowing in all the middle and western states. Barley is more favorably affected than any other grain, by soaking twenty-four hours before sowing, and mixing with dry ashes. A weak solution of nitre is best for soaking the seed.

Varieties are two, four, and six rowed. The two-rowed grows the tallest, and is most conveniently harvested. It is controverted whether the six-rowed variety yields the largest crop to the acre. If the weather[Pg 58] be dry, and the worms attack the young plants, rolling when two or three inches high, with a heavy roller, will save and increase the crop. Rolling is a great help to the harvesting, as it levels the surface.

Harvesting should always be attended to just as it turns, but by all means before the straw becomes dry. If it stands up, cut with cradle or reaper, and bind. If lodged, cut with a scythe, and cure in small cocks like clover. Standing until very ripe, or lying scattered until quite dry, is very wasteful.

Products are all the way from fifteen to seventy bushels to the acre, according to season and cultivation. Reasonable care will secure an average annual crop of forty-five or fifty bushels per acre, which makes it a profitable crop while the demand continues. It is a good crop for ground feed for all animals, the beards being a little troublesome when fed whole. The straw is one of the very best for animals. Barley requires the use of the land only ninety days, leaving it in good condition for fall-grain.

Used for malting, and for food for men and beasts. It makes handsome flour and good bread. Hulled, it is a better article of food than rice.

It succeeds well on land not stiff and tenacious enough for wheat, or moist and cool enough for oats. If farmers should raise only for malt, the nation would become drunk and poor on beer, and the market would be ruined. But raised as food, it is one of the most profitable agricultural products.[Pg 59]

A barn should always front the north. The yard for stock should be on the south side, with tight fences for protection on the east and west. As this is designed for winter use, it is a great saving of comfort to the creatures. The barn-yard should be hollowed out by excavation, until four or five feet lower in the centre than on the edges. The border should be nearly level, inclining slightly toward the centre, to allow the liquid in the yard to run into it for purposes of manure. The front of a barn should be on the summit of a small rise of ground, to allow water to run away from the door, to prevent mud. In hilly countries it is very convenient to build barns by hills, so as to allow hay and grain to be drawn in near the top, and be thrown down, instead of being pitched up. These general principles are sufficient for all ordinary barns. Those who are able to build expensive barns had better build them circular, eight or sixteen square, and one hundred feet in diameter—the lower part, to top of stable, of stone. Let the stable extend all around next to the wall, and a floor over the stable, that teams may be driven all around to pitch into the bays, and upon the mows and scaffolds, at every point. Thus teams may go round and out the door at which they entered. Such a floor will accommodate several teams at the same time. The cellar should be in the centre, surrounded by the stable. Such a cellar would never freeze, and would hold roots enough for one hundred head of cattle, which the stable would easily accommodate. Let the mangers be around next the cellar, for[Pg 60] convenience of feeding. Such a barn would be more convenient for a dairy of one hundred cows, or for winter-fattening of cattle, than any other form. It would cost no more than many barns in western New York that are not half as convenient.

These are divided into two classes—pole and bush beans. They are subdivided into many varieties. We omit the English, or horse-bean, as being less valuable, for any purpose, than our well-known beans or peas. Pole beans are troublesome to raise, and are only grown on account of excellence of quality, and to have successive gatherings from the same vines. Pole beans are only used for horticultural purposes.

Field-Beans.—For general culture there are three varieties of white—small, medium, and large. Of all known beans, we prefer the medium white. The China bean, white with a red face, is an early variety. All ripen nearly at the same time. It cooks almost as soon as a potato, and is good for the table; but it is less productive, and less saleable because not wholly white. For planting among corn, as for a very late crop, this bean is valuable, because it matures in so short a time. Good beans may be raised among corn, without injury to the corn-crop. This can only be done when it is designed to cultivate the corn but one way. Many fail in attempts to grow beans among corn, by planting them at first hoeing. The corn, having so much the start, will shade the beans and nearly destroy them.[Pg 61] But plant at the same time of the corn, and they will mature before the corn will shade them much, and not be in the way even of the ordinary crop of pumpkins. But double-cropping land in this way, at any time, is of very doubtful utility. A separate plat of ground for each crop, in nearly all cases, is the most economical. To raise a good crop of beans, prepare the soil as thoroughly as for any other crop. Beans will mature on land so poor and hard as to be almost worthless for other crops. But a rich, mellow soil is as good for beans as anything else, though not so indispensable. Drill in with a planter as near together as possible, and allow a cultivator to pass between them. One bushel to the acre on ordinary land, and three fourths of a bushel on very rich land, is about the quantity of seed requisite. Hoe and cultivate them while young. Late cultivation is useless—more so than on most other crops. Beans should not be much hilled in hoeing, and should never be worked when wet. All plants with a rough stalk, like the bean, potato, and vine, are greatly injured, sometimes ruined, by having the earth stirred around them when they are wet, or even damp. Beans are usually pulled; this should be done when the latest pods are full-grown, but not dry. Place them in small bunches on the ground with the roots up. If the weather be dry, they need not be moved until time to draw them in. If the weather be damp, they should be stacked loosely in small stacks around poles, and covered with straw on the top, to shed rain. Always haul in when very dry. Avoid stacking if possible, for they are always wasted rapidly by moving. In drawing in, keep the rack under them covered with blankets to save those that shell.[Pg 62]

In pulling beans, be sure and take hold below the pods, otherwise the pods will crack; and although no harm appears then to be done, yet, when they dry, every pod that has been squeezed by pulling, will turn wrong side out, and the contents be wasted. If your beans are part ripe and the remainder green, and it is necessary to pull them to save the early ones, or guard against frost, when the ripe ones are dry, thrash them lightly. This will shell all the ripe ones, and none of the green ones. Put the straw upon a scaffold and thrash again in winter. Thus you will save all, and have beautiful beans. Bean-straw should always be kept dry for sheep in winter; it is equal to hay.

Garden-Beans.—There are many varieties, a few of which only should be cultivated. Having the best, there is no object in raising an inferior quality.

The best early string-bean is the Early Mohawk; it will stand a pretty smart spring-frost without injury; comes early, and is good. Early Yellow, Early Black, and Quaker, or dun-colored, are also early and good.

Refugee, or Thousand-to-one, are the best string-beans known; have a round, crisp, full, succulent pod; come as soon as the Mohawks are out of the way; and are very productive. Planted in August, they are excellent until frost; the very best for pickling. For an early shell-bean we recommend the China red-face; the white kidney and numerous other varieties are less certain and productive.

Running Beans are numerous. The true Lima, very large, greenish, when ripe and dry, is the richest bean known; is nearly as good in winter, cooked in the same way, as when shelled green. They are very productive, continuing in blossom till killed by frost.[Pg 63] In warm countries they grow for years, making a tree, or growing like a large grapevine.

The London Horticultural—called also Speckled Cranberry, and Wild Goose—is a very rich variety. The only objection is the difficulty of shelling; one only can be removed at once, because of the tenderness of the pod. The Carolina or butter bean often passes for the Lima. It has similar pods, the bean is of similar shape, but always white, instead of greenish like the Lima, and smaller, earlier, and of inferior quality. The Scarlet Runner, formerly only grown as an ornament on account of its great profusion of scarlet blossoms continuing until frost, is a very productive variety; pods very large and very succulent, making an excellent string-bean; a rich variety when dry, but objectionable on account of their dark color. The Red and the White Cranberries, Dutch Caseknife, and many other varieties, have good qualities, but are inferior to those mentioned above. Beans may be forwarded in hotbeds, by planting on sods six inches square, put bottom-up on the hotbed, and covered with fine mould; plant four beans on each sod; when frost is gone, remove the sod in the hill beside the pole, previously set, leave only two pole-beans to grow in a hill; they will always produce more than a greater number. A shrub six feet high, with the branches on, is better than a pole for any running bean; nearly twice as many will grow on a bush as on a pole. Use a crowbar for setting poles, or drive a stake down first, and set poles very deep, or they will blow down and destroy the beans.[Pg 64]