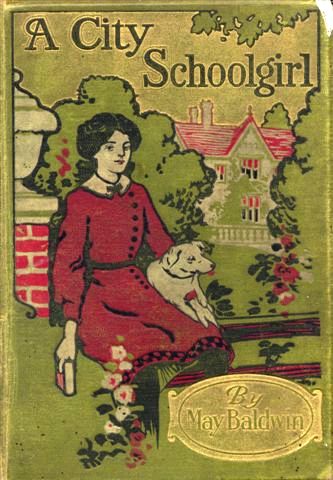

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A City Schoolgirl, by May Baldwin

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A City Schoolgirl

And Her Friends

Author: May Baldwin

Illustrator: T. J. Overnell

Release Date: January 2, 2010 [EBook #30837]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A CITY SCHOOLGIRL ***

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

CHAPTER I. HARD FACTS

CHAPTER II. THE NEW LAIRD OF LOMORE

CHAPTER III. FRIENDS IN NEED

CHAPTER IV. UPS AND DOWNS

CHAPTER V. THE NEW LIFE

CHAPTER VI. IN LONELY LODGINGS

CHAPTER VII. KIND-HEARTED LONDONERS

CHAPTER VIII. GOOD MANNERS

CHAPTER IX. THE ENTERPRISE CLUB

CHAPTER X. BLEAK HOUSE HOSTEL

CHAPTER XI. 'THE RANK IS BUT THE GUINEA'S STAMP'

CHAPTER XII. 'SAVE'

CHAPTER XIII. YOUNG HOUSE-HUNTERS

CHAPTER XIV. OFF TO A HOME AGAIN

CHAPTER XV. EVA'S PRESENTIMENT

CHAPTER XVI. VAVA'S BUSINESS LETTER

CHAPTER XVII. A SUNDAY AT HEATHER ROAD

CHAPTER XVIII. STELLA'S SURPRISING REQUEST

CHAPTER XIX. THE JUNIOR PARTNER

CHAPTER XX. VAVA ON FRIENDS

CHAPTER XXI. EVA'S CONDUCT AND ITS SAD EFFECTS

CHAPTER XXII. DANTE'S IDYLL

CHAPTER XXIII. STELLA'S PRIDE

CHAPTER XXIV. BADLY BEGUN AND MADLY ENDED

CHAPTER XXV. UNDER A CLOUD

CHAPTER XXVI. MORE CLOUDS

CHAPTER XXVII. THE VALUE OF A GOOD CHARACTER

CHAPTER XXVIII. VAVA GETS A SHOCK

CHAPTER XXIX. THINGS STRAIGHTEN OUT

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

She ran off, turning round to wave her hand to her sister

'Vava,' said Stella, 'do not say such dreadful things'

'I'm quite well, thank you, Mr. Jones; but my algebra isn't.'

'My lamb, you should not answer your sister as you do'

'Where have you been, Vava Wharton?' demanded Miss Briggs

Stella goes to the prize distribution

'These are the facts, Miss Wharton; hard facts no doubt, but you wished for the truth, and indeed I could not have hidden it from you even if I had wished to do so.' So said a keen but kindly faced old gentleman, as he sat in an office surrounded by despatch and deed boxes which proclaimed his profession to be that of a lawyer.

The young lady to whom these remarks were addressed, and who was a pretty girl of twenty-one, dressed in deep and obviously recent mourning, now replied, with a sad smile, 'But I did not want you to hide anything from me; I wanted to hear the truth, Mr. Stacey, and I thank you very much for telling it to me. Then I may understand that we have just fifty pounds a year to live upon between the two of us?'

'That is all, I am sorry to say; at least all that you can count upon with any certainty for the present, for the shares, of which I have been trying to tell you, at present bring in nothing, and may never do so. Of course there is the furniture, which might fetch a hundred or two, for there are two or three valuable pieces; and, besides that, your father had some nice china and some fine old silver,' observed Mr. Stacey.

'Oh I could not sell that!' said the girl hastily, and her colour rose.

The old lawyer shook his head. 'It is not a case of could; it is a case of must, my dear young lady,' he said not unkindly.

'But why? You say there are no debts to pay. Why, then, should we part with all that is left to us of home?' argued the girl, the tears coming into her eyes.

'Why? Because you must live, you and Vava, and I don't quite see how you are to do that on fifty pounds a year—twenty-five pounds apiece—even if we get your sister into a school where they would take her on half-terms as a kind of pupil-teacher,' explained the lawyer patiently.

'Send Vava to a school as a pupil-teacher, to be looked down upon and despised by the other girls who were richer than she, to waste half her time in teaching, and let her go away from me? I could not do it!' cried the girl impulsively. Then, as she saw the old man, who had been a lifelong friend of her father's as well as his lawyer, shrug his shoulders, as much as to say she was hopeless, she added more quietly, 'We have never been parted in our lives, Mr. Stacey, and we are sad enough as it is,' and her lips quivered. 'She would be so lonely without me, and I without her; and surely it is as cheap for two to live together as one? Besides, I am going to earn money; I was my father's secretary for three years, and he always said I was a very good one. I can typewrite quite quickly; I have typewritten all his letters for him for the last three years and copied all his manuscripts, and I scarcely ever made a mistake.'

Her listener looked doubtful for a moment; but now that she had some practical suggestion to make, the interview began to take a more business-like appearance, and the old man was ready to listen to her.

'Yes,' he said, 'your father often told me that you were better than any trained secretary he ever had, and I have no doubt your three years' experience has been useful to you; but unfortunately there is no one here who happens to want a secretary'——

Before he could get any further, Stella Wharton interrupted eagerly, 'But we do not think of staying here, and I have thought the whole matter over. I knew I should have to earn my own living, and of course the proper place to do that is in London.'

Mr. Stacey's look of consternation would have been amusing if he had not been so serious. 'You and Vava go and live in London alone! The thing is impossible!'

'Why impossible?' asked Stella quietly. 'Hundreds and thousands of girls do it who are not even as old as I am.'

'Yes, but not girls like you,' said the lawyer. He stopped from sheer inability to express what he meant and felt, which was that such an exceptionally pretty girl as Stella Wharton ought not to start life alone in London and be thrown on her own resources, even though she was a thoroughly trustworthy girl and had a younger sister to live with her. 'You do not know anything about London, or even what a town is like; you have lived in this little Scotch village (for it is not much more), as far as I know, all your life, and the thing would never do. It's—it's impossible!' he wound up; 'you could not possibly do it!'

'It is not a case of could; it is a case of must,' quoted Stella, with the ghost of a smile, as she repeated the old man's words of a few minutes ago.

'Yes, yes,' he said; 'you must live, I know that; but even supposing that it would be possible for you to earn your living, and even to earn it as a secretary, you would not be able to earn enough at first to keep yourself, let alone keep your sister as well.'

'We could live on very little,' pleaded Stella; and here she brought out from her purse a slip from a newspaper. 'I thought of answering this.' So saying, she handed it to the old lawyer, who read an advertisement for a secretary in a City office who could typewrite quickly and correctly, and transcribe difficult manuscripts in French and English.

'You might be able to do this,' said the lawyer, 'for, to be sure, you are both excellent French scholars; but a City office'——He looked most disapproving. 'Well,' he said, 'there is no harm in answering it; or suppose you let me answer it for you?'

'I was going to ask you whether you would give me a testimonial; but if you would write for me it would be very, very kind of you,' replied Stella.

'Very well,' said Mr. Stacey with a sigh, 'I shall write to this man; but no doubt he will have hundreds of other applications. The pay is good, and girls who can typewrite are to be found by the thousand nowadays.'

'Yes,' said Stella eagerly; 'but he says "an educated person," and I read in the papers the other day that three-quarters of the girls who go in for typewriting cannot even write their own language, so they probably would not be able to write French.'

'But thirty-five shillings a week! How are you going to live upon thirty-five shillings a week?' inquired the lawyer.

'It will be forty-five shillings a week,' corrected Stella.

'Well, forty-five shillings a week between two of you; that is not a hundred and fifty pounds a year. It would take that for you alone to live in London.'

'I have calculated it all out, Mr. Stacey; and if you would not mind looking at this sheet of paper I think you will see that we could do it;' and Stella handed the lawyer a second piece of paper, upon which, in a very neat and legible hand, the girl had written out her idea of the probable cost of living for two people in London in lodgings.

'Rent ten pounds a year!' ejaculated the lawyer, reading the first item on the list in a tone of mingled surprise and amusement. 'That shows how much you know of London and its prices. Where do you suppose you would get lodgings for two people at eight shillings per week? Why, a couple of rooms would cost a guinea at least.'

Stella Wharton's expressive face fell as she said, 'I didn't know that. The Misses Burns have a very nice little house here for twenty pounds a year, and I thought lodgings could not possibly be as much, for we would be content with two rooms at first.'

The lawyer read the items through with as grave an air and as attentively as if he were reading an important document dealing with thousands of pounds; and when he had finished he handed it back to her, saying, 'I see, you have thought the matter out carefully, and, at all events, there is no need to settle anything just yet, for you have another month before everything can be settled up here. I shall write to-night in answer to this advertisement.' And then shaking hands very kindly with the girl, the lawyer showed her out.

Stella made her way back to the old Manor House, in which she had lived with her father, mother (who had died some years ago), and her younger sister Vava, ever since she was born, and where a week ago her father had suddenly died, leaving his two daughters, as will have been seen, very inadequately provided for. At the gate, or, more correctly speaking, upon the gate, was Vava, who swung lightly over and into the road to meet her sister.

'Well,' she said, 'what had Mr. Stacey to say?'

'A great deal,' said Stella gravely, as Vava took her arm and hung on to her elder sister.

There were seven years between the two girls, the gap between having been filled by three brothers, who had all died.

'Stella,' said Vava in a coaxing tone, as they turned in at the gate and walked up the long drive, 'you need not be afraid of telling me about it, because I know it all—everything.'

'What do you know?' inquired Stella, smiling in spite of her sadness.

'I know everything that Mr. Stacey said to you,' announced the younger girl confidently.

'How can you possibly know that, Vava, seeing that I have not told you a single word and that you were not at the interview?' Stella was always very matter-of-fact, and Vava would say that she was slow.

'I knew what he was going to say before he ever opened his mouth. He was going to tell you that we had lost all our money, and that this Manor House is not ours any longer, that I must go to a cheap school, and that you must go and be a governess, or something horrid like that,' announced Vava.

'Vava, who told you?' cried Stella, surprised out of her caution, for she had not meant to tell her younger sister the real facts of the case.

'Mrs. Stacey has been here, and she told me that there were some other people coming to the Manor House. When I said we didn't want them, she said the Manor House was not ours, and that we should not be able to keep them out. When I asked her why, she said because we had no money.'

'Mrs. Stacey was quite wrong, and she had no business to speak to you like that. I am sure Mr. Stacey would be very angry if he knew,' said Stella, who looked rather angry herself. 'Besides which,' she added in a calmer tone, 'we have not lost all our money; we have more than a thousand pounds. And you were not quite right about Mr. Stacey either, for he did not suggest that I should go out as a governess, and he is at this minute answering an advertisement for a secretaryship for me.'

Vava was silent for a minute; then she said in a queer little voice, very unlike her usual cheerful one, 'But he did say I was to go to a school, didn't he?'

'Would you dislike that very much?' said Stella, more to try her sister than because she had much doubt of the answer.

'I should hate it, Stella; I would rather scrub floors than be a charity-girl with a red cloak and a round hat and short hair, with perhaps people giving me pennies as I walked along the street.'

'There is no chance of your going to a charity school,' replied Stella, 'there will be enough money to send you to a proper boarding-school, if that is necessary, for there are lots of schools where you do not pay much more than fifty pounds a year; but I should like you to live with me in London, and go to day-school there.'

'Oh Stella, how lovely! and we could go to the Zoo and Madame Tussaud's and the Tower every day for a walk!' cried Vava with delight.

'I am afraid we could not go daily expeditions, Vava, because I should be in an office all day and you will be at school; but we should have Saturdays and Sundays together, and anything would be better than being parted—wouldn't it?—even if we are poor.'

Vava did not answer, but the squeeze that she gave to Stella's arm was quite answer enough. They had arrived at the door of the Manor House, and the old housekeeper came forward to meet them.

'My dears, come into my little room and have some tea; you must be perished with cold, and I have got some lovely scones that cook has made on purpose for you. Come straight in, won't you, Miss Stella?'

'Thank you, nursie,' said Stella with a pleasant smile, as she followed the housekeeper to her room; while Vava danced along in front of the old woman, calling her all sorts of affectionate names for her thoughtfulness in getting hot scones for them on this cold day.

It was not a usual thing for the girls to have tea with the housekeeper, though they did sometimes do it. But Stella, though surprised at the way the housekeeper asked them, thought it was to save them from having a lonely tea in the dining-room without their father; and to the housekeeper's relief she went straight to the latter's room, and partook very cheerfully of the homely meal set before them. Twice during the meal Stella thought that she heard voices in the passage which she did not recognise as belonging to the servants, who, indeed, were not in the habit of speaking in such loud tones about the house; but she paid no attention to it.

The housekeeper, who had formerly been the girls' nurse, and was still called 'nursie' by them, talked more than usual.

At last Vava observed, 'Nursie, I believe you are feverish.'

'Miss Vava!' exclaimed the old woman, 'what can you be thinking about? What makes you think I am feverish? I am not a bit hot, unless this big fire is making my face a bit red.'

'I am not talking about your face; it is your voice that is feverish, and your eyes are glittering dreadfully,' said Vava.

'Vava,' said Stella, 'do not say such dreadful things.' She also looked at the housekeeper, who did look nervous, if not feverish, as Vava had suggested, and whose face certainly got very flushed as a knock came to the door.

The butler, throwing it open, said to a gentleman and a lady who accompanied him, 'This is the housekeeper's room, sir, and this'——Here he caught sight of Stella and Vava, and with a muttered, 'I beg your pardon, young ladies, I am sure,' he shut the door, and his footsteps were heard hurrying down the passage.

The three occupants of the housekeeper's room took the unexpected visitors in very different and characteristic ways. The housekeeper became what Vava called more 'feverish' than ever; Stella stared in grave surprise at this liberty on the part of the butler; while Vava grew red with anger, and, guessing at once what it meant, cried indignantly, 'How dare they come walking over our house before we are out of it? Stella, why don't you go and tell David he ought to be ashamed of himself letting them in? What is he thinking of to take such a liberty?'

Stella turned her eyes, which justified her name, and looked at her excited younger sister. She had not understood the meaning of the intrusion until her quicker-witted sister told her, and she was not too pleased herself at old David's behaviour, which even she, quiet and attached to the old servant as she was, felt was taking too much upon himself.

But, before she could speak, the old housekeeper broke in, rather nervously, 'Miss Stella, dearie, you must not be angry with David; it's my fault as well as his; we only wanted to save you both worry and annoyance; and so it would, for you would never have known aught about it but for David bringing them in here. He must be daft, after my telling him he was to be sure and keep them out of your sight.'

'But I don't understand. I suppose these are the people who want to take the house, and, if so, of course they wish to see it? Still, I think they should have written just to ask my leave; and, at any rate, David should have done so before he showed them over our house,' Stella answered with dignity.

'That's just it; you don't understand, my bairn; and I don't rightly understand it myself. It's their house—something about a mortgage—now the poor Laird's gone, and they only waited until he was under the ground to come tearing up from London in their motor to look at their property, and it was more than David could do to put them off, and so, sooner than have you troubled by their impudence'——said the housekeeper.

'It is not very considerate, perhaps, but they have a right to ask to see their own house without being called impudent; and though you mean it kindly, nursie, you and David, I think I should know what is going on in this house,' interrupted Stella.

'We'd just better get out of it as soon as we can. Mrs. Stacey came to ask us to go and stay with them; she told me to give you the invitation. But I'd rather go to the manse; Mrs. Monro would be sure to take us!' cried Vava.

However, before Vava had uttered the last word, another knock came at the door, and in answer to Stella's 'Come in!' David M'Taggart entered, looking rather shamefaced. In broad Scotch, which it will perhaps be best to spare English readers, he said, 'I'm sorry to trouble you, Miss Stella, but the leddy will not take no for an answer; she wants to see you.'

Stella unconsciously put on her most dignified air, and said, 'I do not understand why she should wish to see me. It is the house they have bought, not us; and if she wishes to know when it will be at her disposal, you may tell her we will be out of it'—she hesitated a moment, and her voice trembled as she added, 'as soon as we can move the furniture; in a week, if possible.'

Still David lingered. 'It's just that—the furniture, I mean—that she'll be after, I'm thinking. I know it's hard on you, missie. But you must just be brave and the Laird's daughter; and, if you could make up your mind to it, just see the leddy and her husband; they're no' bad, though they're no' the quality.'

David M'Taggart had nursed Stella in his arms as a baby, and had been the old Laird's right hand. In fact, when Mr. Wharton was deep in his literary labours, David had kept things about the place straighter than they would otherwise have been; and if his education had been better, and he had been allowed, he would probably have managed the money matters of his late master, and prevented the Laird allowing them to get into the disastrous state they were found to be in after his death, of which state the late Laird was, happily for him, though unfortunately for his daughters, quite ignorant.

Stella listened to David's advice, and replied, 'Very well, David, I will see this lady. What is her name?'

'It's a fine name—Mrs. Montague Jones she calls herself; but it's with him I'd do business, if I may be so bold as to say so, for he's a fair man, and not so keen on a bargain as she.'

To this piece of advice the girl made no reply, but followed the old butler out of the room and down the wide staircase to the drawing-room. At the door she paused involuntarily, as David threw it open for her and announced, 'This is Miss Wharton, mem.'

The short, thick-set business man, who was standing looking out of one of the windows, turned sharply round at the words; and, as he told his wife afterwards, was 'fairly taken aback to see that beautiful young lady standing there like a princess in the doorway and looking down upon us.'

And his wife—a handsome woman herself, who was sitting at a table examining some old silver, of which the Laird had a fine collection—though she answered him rather sharply to the effect that the 'looking down' ought to be on their side rather than the Whartons', was conscious somehow of a feeling of inferiority. However, she rose, and, coming forward, said civilly and kindly enough, 'I must apologise, Miss Wharton, for this intrusion, and it's only because I think we may be able to be of use to you'——Here Mrs. Montague Jones stopped abruptly, for Stella's pride had risen, and she stiffened visibly.

'My wife doesn't mean that, Miss Wharton. What we wished to ask was a favour to us, for which we would willingly make a return. I'm a business man, and you are a young lady who knows nothing about business,' Mr. Montague Jones now put in.

But Stella did not look any better pleased as she answered civilly but distantly, 'In that case would it not be better to address yourself to our lawyer, who is a man of business?' Stella had been her father's secretary for so long that she spoke in a slightly stilted English with a Scotch accent.

'Quite right, and so we did, but he told us he could do nothing without you'—Mr. Stacey had said that he could do nothing with her on this particular matter—'and we have taken the liberty of coming straight to the fountain-head, so to speak. It's about this furniture now.'

But Stella interrupted hastily, 'I am afraid you have given yourself unnecessary trouble'—and her looks said 'and me too'—'for I have no intention of parting with it.'

A gleam came into the man's eye, whether of anger at her haughtiness or admiration at the spirit which could refuse a possibly advantageous business offer was not clear, with poverty staring her in the face; but he laid a hand on his wife's arm to prevent her speaking, and continued quietly, and in a kind and friendly tone, 'No one has asked you to do that, Miss Wharton. I feel with you that however valuable furniture or silver or that kind of thing may be, it is doubly valuable to the owner, especially when, as in your case, it has been in the family for a long time, and I should be the last to counsel you to part with it.'

Miss Wharton looked surprised, and so did Mrs. Jones, who stared at her husband in amazement.

'In that case, I fail to see'——began the girl, and then hesitated.

'You fail to see what proposal I have to make about the furniture? If you'll have a little patience I'll tell you. I've just seen your lawyer, and a very nice man he is, and has your interests at heart, for which you may be thankful, as they are not all so. I hear you are thinking of going to London. Now, you can't take all this fine furniture with you; it would get knocked to pieces on the way there, besides costing no end of money, and you'd want a mansion to put it in when you got there, which you won't have just yet, though you will have again one day, I hope. Now what, may I ask, do you mean to do with it?'

'I don't know. I shall warehouse it here, I suppose,' said Stella, who had no clear ideas on the subject.

'That's just what I was going to suggest. Why not leave it all here, with the exception of any little things or specially valuable belongings that you 'd like to put away, and let us pay a fair sum for the use of them. They'll not spoil, for they are old and well-made, and there'll only be the wife and me and Jamie, that's our son and heir—ahem! a quiet, well-behaved young fellow—and none of us will knock it about; besides, your man M'Taggart has agreed—condescended I might say—to stay on with us for the present, and he'll be free to write and tell you if it's being badly used; and we'll put a clause in the agreement that if M'Taggart thinks it is in bad hands you have the right to order its removal in twenty-four hours,' announced Mr. Jones.

'Really, Monty'——cried his wife; but her husband pressed her arm, and patiently waited for Stella's reply.

The girl puckered her brows; it would be a way out of the difficulty. But she did not feel equal to settling the matter herself, and answered doubtfully, 'If Mr. Stacey approves, I should have no objection—that is to say, I would agree; but I should like some of my mother's things put away.'

'Oh of course, we quite understand that, Miss Wharton, and we will have everything put down in black and white by your lawyer,' said Mr. Montague Jones.

Stella, who had taken the seat offered her by her undesired visitor, now rose to put an end to the interview; and then a sudden thought struck her. These people had motored from the south, and perhaps had come far that day—at any rate from the nearest town, a good many miles off—and she had not even offered them a cup of tea, and her Scotch hospitality forbade her to let them depart without doing so much. She accordingly offered it, and Mrs. Jones accepted the offer so gladly that her young hostess felt ashamed of herself; and, ringing the bell, she ordered in tea.

The interval of waiting might have been rather awkward; but not long after David had answered the summons the door opened, and in walked Vava.

Mr. and Mrs. Jones had an idea that Scotch girls in general were plain and hard-featured, hence their surprise at Stella's appearance; and Vava, though she was at an awkward age, and had not Stella's beauty, was a bright, fresh-looking girl, with merry, laughing eyes which no trouble could dim for long, and she too fitted in with her surroundings.

'How do you do? David will bring the tea in a minute, and there are still some scones left,' she announced, without waiting to be introduced.

Mr. Jones shook her hand heartily. 'That's good hearing; we lunched early, and I've been with lawyers ever since, and worried with business, about which you luckily know nothing; and scones—which we poor ignorant Londoners call "scoones"—sounds very inviting.'

'So they are, deliciously inviting; but as for your business, I just do know something about it,' Vava observed.

'Vava!' cried Stella horrified.

Mr. Jones laughed, not in the least embarrassed, though he had not meant to be taken up so. 'Ah well, business is business and pleasure is pleasure, and I don't believe in mixing them, though some people do. Business is over for this afternoon, and now I am having the pleasure of making your acquaintance.'

'Do you go to school, Miss Wharton?' inquired his wife, putting the first question ladies seem invariably to put to girls in their teens.

'No, but I am going to a day-school when we get to London. Do you know any nice ones there, not too dear?' inquired Vava.

Stella coloured hotly, and looked despairingly at Vava, who was evidently in a mood to say dreadful things, as Stella considered them.

But Mr. Jones stepped into the breach. 'If you take my advice you'll go to my school; it's one of the best in London.'

'Do you keep a school? I didn't know rich people did that,' said Vava.

'I don't keep it exactly, but I am chairman of the governors, and on speech-days I go there, dressed in my chain and brass breastplate and things, and listen to how all the girls have been getting on, and I frown at the idle ones, and praise the good ones, and if you were to come there I should praise and clap you. It's a first-class school though the fees are very low,' he wound up, as if this were an important detail.

'Nothing is decided yet,' said Stella, rather shortly, and frowning at the too candid Vava.

'No, and of course there is no hurry; and, if you will excuse my talking of business, I should like just to say that if you wished to stay here a month or more we should be delighted. As for that school, it is a famous City foundation, and I will send you the prospectus when I return home, if you will allow me,' said Mrs. Jones, whom tea and scones had made quite friendly.

'A City school!' said Vava. 'Is that a charity school?'

'Oh dear no!' cried Mrs. Jones hastily. 'My niece used to go there.'

Stella gave a ghost of a smile, but said nothing; and soon her visitors left, with profuse thanks and promises to see the lawyer and let him arrange matters.

It was consequently with lightened hearts that the two orphans stood looking after their visitors in the darkening day.

'They are not quite ladies and gentlemen—I mean, a lady and gentleman—but they are rather kind, and I think they will take care of our furniture, Stella; so I should let them have it till we are rich again and can buy this place back from them,' said Vava, as she stood on the steps watching the tail-light of the Montague Joneses' well-appointed car disappear down the drive.

'How do you know anything about that?' inquired her sister in surprise; for unless her sister had been listening at the door, a meanness of which she knew her to be incapable, she could not imagine how she could guess what the new owners of Lomore had been proposing.

'Ah, ha! a little bird told me. But I quite approve; it will save us the trouble of moving it about, and you'll see we shall be back here again before long; that's another thing a little bird told me,' cried Vava, loosing her sister's arm to hop on one foot down the stone steps, and then try to perform the same feat up them.

'Vava! do be sensible at your age, and tell me what you mean by your nonsense about a little bird telling you a private conversation which no one could honourably know anything about,' said her sister severely.

Vava was sobered for the minute; and, giving a last hop on to the top step, she stood on her two feet before her sister and retorted, 'What do you mean by your insinuations, pray? Do you imagine I have been listening through the keyhole? because, if so, I decline to parley with you further. And as for my age, why shouldn't I do gymnastics? When I go to an English school I shall have to do far sillier things than that. And, oh Stella! do you think I shall go to that City school? I don't think I should like to be taught by Mr. Montague Jones, though he is a kind old man.'

'Mr. Montague Jones does not teach there; he told you that, and I don't know at all where you will go to school. Perhaps it will be a boarding-school after all, for we cannot live in London unless I get this post as secretary, or some other like it; and you would perhaps be best away from me, for you do not obey me,' replied her elder sister.

'If you mean that you want to know how I knew about the Joneses and their offering to take care of our furniture, David told me; and if you want to know how he knew—which I can see you do, because you have screwed your eyebrows into a question-mark—Mr. Jones told him himself, when David said he knew we would never sell it—for it is half mine, isn't it, although you are my guardian?—and it's to look after it and the place for us till we get it back that David is staying with them, though "they are not the quality," as he says.'

This explanation satisfied Miss Wharton, and she only said, in answer to Vava's last remark, 'Yes, the furniture is half yours, of course, and I should have told you about this offer, as I am legally responsible for it and all your property. And talking of property, Vava, it is very hard I know, but this place is no longer ours, nor can it ever be again, for we have no rich relations to leave us enough money to buy it back; nor shall we ever have enough ourselves even if the Joneses wanted to sell it, which I don't fancy they will, for they have bought it for their son and heir, as they called him to me.'

'How hateful! a Londoner Laird of Lomore! Oh but he sha'n't be that long, for I am going to earn a fortune and turn him out!' cried Vava, her eyes flashing.

Stella laughed at her younger sister's vehemence, and inquired, 'In what way are you going to earn money, pray?'

'I'm going to invent something. I read the other day in that ladies' magazine of a man who invented a very simple little thing to save candles, and he made thousands and thousands of pounds by it; and I've got an idea too—it's a thing to save matches,' announced Vava.

'Matches! Why should one save matches? They are cheap enough without saving them,' exclaimed Stella.

'Not in every country. Don't you remember Mrs. M'Ewan saying that when they were abroad last year they paid a penny a box, and for such bad ones too? Well, my idea is to make them light at both ends; you always throw away half the match, and now it will do for twice,' explained Vava.

Stella did not laugh for fear of hurting Vava's feelings and arousing her wrath, but only said, 'You do think of odd things, Vava; but I wish you would not say all you think. I am often quite nervous of what you may say or do next.'

'You needn't be nervous now, because I am going to be quite grown-up and proper, and not give you any more trouble,' announced Vava, who meant what she said, though she did not always act up to her excellent resolutions, as will be seen.

In fact, only two days later she made her sister nervous, besides annoying her; for, as the elder girl was walking towards the village to Mr. Stacey's office, in answer to a message from him requesting her to call, she saw her sister, whom she had missed for the last hour, sitting beside Mr. Montague Jones in his motor, being whirled past her at a terrible speed, or at least so it seemed to her. Whether Vava saw her or not Stella could not be sure; but she took no notice of her, neither did Mr. Jones, whom she supposed did not recognise her. Rather ruffled at the occurrence, Miss Wharton continued her way to the lawyer's, her pretty head held still more erect, and a slightly scornful smile on her face at the way her sister's indignation against the London Laird had evaporated.

'Well, Miss Wharton, my dear, I have good news for you—at least, I suppose I must call it good news, though it means that we shall lose you, for the people whose advertisement I answered have written offering you the post of secretary to the junior partner of a very good firm in the City of London—Baines, Jones & Co. Your hours will be ten till four, short hours for London clerks—er, secretaries I mean; and your work will be to translate French letters for him and write French answers, which he will dictate in English. You see it is a position of trust, because they don't know much French and have to trust to your translating their letters faithfully, and that I was able to assure them you would do. In fact, after what I said they were quite ready to take you, and it is the best I can do for you—not what I should like for your father's daughter, but it might be worse. You will have a nice little room to yourself with your typewriter, and need have nothing to do with any one, and I may tell you that if you give satisfaction your salary will be raised.'

'Thank you very much, Mr. Stacey,' replied Stella briefly. She was grateful, and the old man knew it; but the vision his words brought up of her future life in a stuffy, dingy City office, sitting at a typewriter writing dull business letters—a very different thing from the literary work she had helped her father with—depressed her for a moment. Then she roused herself, and went on to speak of the arrangement which had been agreed upon between the lawyer and Mr. Montague Jones about the furniture, and which only needed her signature to be settled.

'Ah, yes, they have been most generous,' began the lawyer; but he hastened to correct himself when he saw Stella's face stiffen—'fair, I should say, and anxious to meet your wishes. I think we are fortunate in falling into their hands, and may safely trust them.' How fortunate, Mr. Stacey did not dare to say.

'Yes, I think they will take care of our furniture, and they evidently wish to be friendly, which is more than I do, though Vava seems to have taken to them,' replied Stella.

'And they to her. Here is the prospectus of that school Mr. Montague Jones is governor of. He is evidently a little afraid of you and your stately airs'—here the lawyer's eyes twinkled—'not that he thinks the less of you for them, quite the contrary. However, to resume, it seems an excellent school; the teaching staff is first-rate, the building palatial, and the fees most moderate—two guineas a term. Moreover, as it is in the City, not far from your own office, you could go there and back together, which would be a great thing,' explained the lawyer.

He was a busy man, for not only every one in the sleepy little town, but all round, great and small, came to him for advice, and Stella, knowing this, was grateful for his interest in her affairs; and on his advice agreed, if it proved to come up to the prospectus, to send Vava to the City school. This business being settled, she turned homeward with a feeling that now she had no more to do with Lomore, and that the sooner they left it and began their new life in London the better. In fact, this was practically what Mr. Stacey said: Messrs Baines, Jones & Co. would like her to begin at her earliest convenience, and the new term began next Tuesday, and this was Wednesday.

Vava was on the gate when her sister arrived. 'Where have you been? I've been such a lovely drive with the Montagues—well, never mind their other name; it's horribly common anyway. I met them up the road, and they asked if we would come for a run, and we came back to fetch you; but you had gone to Mr. Stacey's, so I was sure you would not mind; and—what do you think?—they are going to drive us up to London in their car!' the girl cried, pouring out the words so fast that her sister could hardly follow her.

'Drive us to London? Indeed, they are going to do no such thing! I do not care to accept favours from strangers; and really, Vava, I don't know what you mean by knowing my affairs before I know them myself. I don't know when we are going to London yet. Perhaps not for a week or two, and at any rate not with those people, who may be very kind, but are not educated; he can't even speak the King's English. No, if we can't make friends in our own class we will go without.'

Vava looked down at her sister, who stood with one hand on the gate, looking so stiff and proud that her face, which was really a sweet one, was almost forbidding. 'All right,' she said, swinging her feet to and fro in a way that made Stella quite nervous—'all right, then; we'll go in a stuffy railway-carriage, and have to sit up all night, and I shall be sick, as I was when we went to Edinburgh; but you won't care as long as you can stick your head up and look down on people who try to be friendly and nice to you, just because he says "dy" instead of "day;" and what does it matter? We pronounce some words quite wrong, according to the English, and I dare say they'll laugh at us when we go south. Mrs. M'Ewan said the waiter at the hotel couldn't understand her when she asked for water.'

Mrs. M'Ewan was a neighbouring laird's wife, and spoke very broad Scotch.

Stella made no answer to this tirade of her younger sister's, who swung herself off the gate and walked back to the house with Stella in no good-humour.

There they found a note from Mrs. Jones, which, to Stella's surprise, was quite grammatically written, asking whether they would honour them by occupying two seats in their car when they went back to town. 'My husband is so taken by your sister, and hearing that the train made her sick, he ventured to suggest your coming with us. He begs me to say that he feels under such obligations to you for lending us your beautiful old furniture and plate—which no money could repay or replace—that he would be glad if you would accept this attention as a mark of our gratitude.'

'That will fetch the proud hussy, if anything will. Poor girls, I am very sorry for them, especially the elder, for she'll have a lot of humble pie to eat before she's done,' Mr. Montague Jones had said to his wife; but this remark, needless to say, she did not mention in the letter. She only added that they were not particular which day they returned to town, but would go any day that suited Miss Wharton.

Mr. Jones may not have been an educated man—in fact, he would have been the first to acknowledge it; but he certainly was a tactful man, and understood managing people, as indeed he well might, for he had managed a large place of business for many years, and done so successfully, as his wealth testified.

So, after reading the letter over slowly, Stella turned to her sister with a half-ashamed smile and said, 'If you like we will go with the Montague Joneses; but only on one condition, and that is that you promise not to get too intimate, or to ask me to be friendly with them in town. They may not want to know us, for we shall be very poor; but I won't be patronised by any one, and I don't want them to call.'

Vava looked as if she were going to say something, but thought better of it, and gave the desired promise.

There was nothing now to keep them at Lomore. Mr. Stacey's clerks had made an inventory of the contents of the house; David M'Taggart and Mrs. Morrison had packed their 'young leddies'' personal belongings, part in boxes to be taken to London, and part locked away in a room in the old home, of which David M'Taggart had the key, and into which, he solemnly assured his late young mistresses, no one should enter but himself.

So all that remained for the two orphans to do was to say good-bye to their friends, which they hurried over as much as possible, for partings are painful in any case, and it was especially so in this one, and the most painful was the parting from 'nursie,' as they called Mrs. Morrison.

'And remember, my bairns, if you are ill or want me at any time, I'm here and ready to come to you. I've a good bit laid by for a rainy day, and I've no need to work any more, thank the Lord, and don't mean to work for any but a Wharton, if he was as rich as Dives; so if ever you should want a maid who needs no wages I'll be waiting for the call, and will be with you as fast as the train will take me, for you're like my own bairns,' said the loyal old servant, who had spent forty of her fifty-five years of life in the service of the Laird of Lomore, as had her father and grandfather before her, and was still as hale and hearty as a woman of thirty.

The two girls clung to her, but could not say a word, and Mr. Montague Jones, who had brought the car to the house to fetch them, turned his head away and cleared his throat suspiciously, feeling, as he told his wife afterwards, like a veritable robber who had stolen their home, and turned these two helpless and innocent girls adrift in the wide world, of which they knew nothing.

Mrs. Montague Jones did her best to be pleasant to her companion, who was Stella, for Vava was sitting beside Mr. Jones and the chauffeur; but though the girl was perfectly civil, and expressed her gratitude for their kindness, Stella was so reserved and unresponsive that it is to be feared that Mrs. Jones did not enjoy her return trip as much as she had done the one northward to take possession of the coveted property, which foolish speculations had caused the late Laird to mortgage up to its full value.

Poor proud Stella, in her innocence it had not occurred to her that she would be entertained at the best hotels on the way south; nor did she know that the journey was being made very leisurely, and, to tell the truth, by rather indirect routes, so that their thoughts might be distracted, and that they might be shown pretty scenery and interesting cathedrals and old towns. But there was no getting out of it now.

'Though if I had had any idea of the obligation we were putting ourselves under I would never have come, not even to prevent your being train-sick, Vava,' she declared to her sister.

'Then it's a very good thing you did not know; we're having a glorious time, and what is a few pounds to them? Nothing, as Mr. Montague Jones says; he is enjoying these sights twice as much for seeing us enjoy them; though, for that matter, you don't look much as if you were enjoying yourself, except when we are going over cathedrals, or looking at some extra-special view, and then, though I say it as shouldn't, your face is worth looking at,' affirmed Vava.

Stella laughed at the candid flattery, and took a hint from the equally candid criticism, and tried to be more agreeable to her kind hostess, with the result that Mrs. Montague Jones was emboldened to ask her if she would not stay a few days with them in Belgrave Square until they had found rooms.

But Stella withdrew into her shell at once. 'Oh no, thank you; you are very kind, but we have the address of some lodgings which Mrs. Monro, our minister's wife, knows, and they are expecting us.'

They were now at their last stage, and Stella handed Mrs. Monro's card to Mr. Jones, and on it was written the address. He took it and read it, and said, 'Vincent Street, Westminster; that's not far from us. We shall hope to see you sometimes; it's a poky little street, and you'll be glad to get out of it, though even Belgrave Square will seem sooty and confined after Lomore.'

It was not as tactful a speech as it might have been, and was received in such freezing silence by Stella that his wife did not dare to second the invitation, and the two girls were deposited at their new abode without any promise of meeting again, as far as Stella was concerned. As for Vava, she shook hands with Mr. Jones very warmly, and kissed Mrs. Jones; but neither did she say anything but good-bye, which, truth to say, she said in such a cheerful tone as to surprise her sister.

But the cheeriness soon subsided at sight of their rooms, for which the landlady, impressed by the grandeur of their arrival, hastened to apologise. 'And where all that luggage that arrived yesterday is to go I don't know; I've no place for it here, miss; so I just told the railway-man to keep all but these two port-manteaus at their storerooms,' she added.

'Perhaps that was best,' said Stella quietly. And then, the woman having taken her departure, she sat down on the bed, a large double one, which filled up half the dingy room, and looked round the apartment and into the tiny sitting-room with distaste.

'It's horrid, and—one thing's certain, I won't have that man staring at me!' cried Vava impulsively, jumping up, and mounting on a chair in order to take down a large portrait of a stolid-faced policeman.

'Vava, come down and leave it alone! What can you be thinking of? That is the landlady's husband, no doubt. Mrs. Monro said he was a policeman, and so we should be safe with him. You will hurt her feelings!' cried Stella.

'Then let her have him in her own bedroom. How can I sleep with him looking as if he were going to take me to prison all the time?' said Vava. However, she did not take 'him' down, but came down herself; and as the Joneses had thoughtfully had a substantial tea before they deposited their passengers, the girls decided that they would want nothing that night but a glass of milk, and went out in the dusk to see what they could of London, and get out of their close and confined lodgings.

'It went to my heart, Monty, to leave those two poor girls in that dreadful place. This world's very unfair somehow,' said Mrs. Jones, as she and her husband entered their own handsome house.

'And yet you were not too pleased at my offer about the furniture, and wanted to make me force them to sell it outright,' her husband reminded her.

'Oh well, business is business; but now that I know those two Misses Wharton I feel glad the furniture is still theirs, though what good it'll do them now or ever—unless some duke comes along and marries Miss Stella for her pretty face—I don't know.'

'The money I pay for hire will do them good'—Mr. Jones was paying fifty pounds a year—'and it needn't be a duke. I'd not mind her for a daughter myself.'

'Pray don't put such ideas into Jamie's head; not that she would not be a good wife, for she's a good girl, but she'd never look at a Jones. And if that's your plan, I'm sorry she ever came to town, for it will only upset Jamie. I do hope he won't fall in love with her!' cried Jamie's mother in alarm.

'Who spoke of Jamie? The girl's up here to earn her living, and has no idea of love-making, thank goodness! As for Jamie, he's all right, and can look after himself at his age, I should hope. I only meant that I'd like as ornamental a wife for him when he reigns up there as I've got to face me,' said Mr. Montague Jones gallantly. Then in the bustle of home-coming and the joy of meeting the aforementioned Jamie, the Whartons were banished as subjects of conversation, although a little later their name cropped up in connection with their property and other matters.

The Whartons themselves never mentioned their late hosts. London in the dusk, with its brilliant lights, its roar of traffic, and its hurrying crowds, claimed their attention.

'Oh Stella, it's awful—just awful!' cried Vava, clinging to her sister's arm in alarm.

'See, there is a park in front of us; let us go in there; it will be quieter,' replied Stella, as she pressed Vava's arm and hurried her over the crossing into Hyde Park, in which direction they had fortunately strayed.

Vava drew a great breath of relief as they began to cross the park diagonally. 'Thank goodness! I can breathe here, and needn't be looking all the time to see where those horrid, screechy motors are coming to, tearing along as they do,' she said, quite forgetful of the fact that she herself had not many hours before been tearing along in one of these same 'horrid motors.'

It was January, and the air was cold, but the Highland girls did not mind that, and took such a long walk, turning and twisting in the park, so as to avoid the streets, that they were tired out when they reached their lodgings. They slept soundly, and the next morning awoke with more courage to face their new life. The first thing was to visit the City school, and this they did together.

'I have heard of you, Miss Wharton,' said Miss Upjohn, the head-mistress, 'and I hope I shall be able to persuade you to entrust your sister to us.' She then proceeded to give her visitor a detailed account of the school, its staff, and its aims. 'Our term begins to-morrow, and that,' she continued, pointing to a large card on the table, 'is our motto for the week. We have a new one each week, and this week, as it is the beginning of the new year, we have taken "Truth and honour." The school motto is "Love as brethren," and I shall make a little speech upon it to-morrow morning after prayers.'

Stella listened in her dignified, reserved way, and it was only when she smiled that the head-mistress understood Mr. Montague Jones's enthusiastic way of speaking of her.

Vava was more responsive. 'Oh Stella, this is a lovely school! Do let me come here. And for our gymnastics we wear a red drill-dress—what fun! And what nice big rooms! I can breathe here!' she cried.

Stella smiled again. 'I don't know what to say; it seems so funny to take the first school one sees without looking about; but we have no time to spare. The only thing I am afraid of is, if you will excuse my saying so, the companions she will find here; it is not a very aristocratic part of London, and I should not like Vava to mix with the children I see in this street.'

Miss Upjohn smiled too. 'I understand your feelings; but I can assure you that though there is a mixture here, as in all big schools—even the best—our girls do not come from the streets; they come from very good neighbourhoods. I do not think your sister will come to any harm by mixing with them, and I will myself take special care of her and let her sit at lunch with one of our teachers, who dine here in the middle of the day.'

Miss Wharton did not know that she owed this concession to Mr. Jones's representations; she did not even know that it was a concession, for she had been used to a good deal of attention both from her position and her beauty; but she knew that Miss Upjohn was being very kind and friendly, and she felt sure her sister would be safe with such a high-principled woman. So before they left the big, ugly red-brick building, which Mr. Jones had truly called palatial, it was decided that Vava should go there the next day and be duly enrolled as a day-scholar at the City School for Girls.

'And now that all that is comfortably settled, let us go and see the Tower; it is in the City, so it must be near,' observed Vava.

But she was mistaken; it was not near. However, as they were walking along—for they were too unused to cities to think it necessary to go everywhere in buses and trams—Stella gave a little exclamation of surprise.

'What is it, Stella? What frightened you?' inquired Vava, looking up at her sister.

'I am not frightened, only surprised. There is the office that I shall go to every day, quite close to your school, so that I can see you to your door before I go there. I am so glad,' explained Stella.

'So am I glad, Stella. Now I sha'n't feel lonely, for I don't mind telling you that I felt just a wee bit frightened at the thought of being away from you among strangers, and no one I knew anywhere near; and here you will be quite near me, so that I can run in and see you whenever I want!' exclaimed the girl.

'Oh but you must not do that; you must not run about the streets alone! London is not Lomore, you know; besides, you will have no time to pay visits in school-hours, nor shall I have time to receive them. You must remember I am only a paid servant to these people,' said Stella, with proud humility. She then continued, 'I cannot receive visitors as if it were my own house, though, of course, if anything were really the matter Miss Upjohn could send for me. It is nice for us both to know we are only a few minutes' walk from each other.'

Not for many a day did Stella and Vava Wharton know to whose kind interest they owed this fact, nor to whom they were indebted for many a privilege, both in the former's office and the latter's school; though it was to one and the same person. At any rate, this knowledge of their nearness to each other made their first day in London a happier one than it would otherwise have been.

The Tower proved as fascinating as it always does to girls who love history when they see the fortress for the first time, and the sisters spent a long time in it and its surroundings, and went back to Vincent Street resigned to, if not content with, their lot, the worst part of which was their lodgings. Stella felt that the house could never be in the least a home to them, and was not situated in a nice part for them to live in, though she did not see what she could do better, with their limited means and knowledge of London.

'But, Stella, you have not to be at your office till ten o'clock! What will you do with yourself for this half-hour?' asked Vava next morning as her sister left her at the gates of the City School for Girls five minutes before school opened, which was half-past nine.

The two sisters had walked together to the City along the Embankment. To girls used to tramping miles over the moors, the walk was nothing, though they found that the pavements tired their feet.

'I shall take a walk, or go into a shop and have a bun,' replied Stella, for on second thoughts she shunned a walk alone through these streets crowded with men, who looked curiously, though not disrespectfully, at the tall, slight, beautiful girl, who walked with a leisurely, unbusiness-like air through the City.

'Yes, go and have a bun, and I will come to the office at half-past three and wait for you in the sitting-room,' said Vava, who felt for her sister being stared at so.

'I don't think there will be much of a sitting-room to wait in, Vava; but when you come to fetch me, just take one of your lesson-books and read quietly until I come down; and, remember, don't talk to any one,' Stella admonished her sister.

Vava looked astonished and as if she were going to argue the question; but the school-bell rang at that moment, and she ran off, turning round to wave her hand to her sister, who stood watching her until she joined a group of girls, with whom she seemed to be conversing in a most friendly way, and not in the least as if it were the first time in her life that she had ever seen them.

With a sigh, Stella turned away; she could not be like that, she could not help being stiff and reserved. Vava was quite different, and her elder sister found herself hoping fearfully that she would not get too intimate with these 'City girls.' However, she consoled herself with the thought that it could only be in school-hours, and that even in the dinner interval she would be with the young teacher who was to take special care of her, and who, at all events, would be an educated woman.

And then, as she felt somehow that her sauntering walk attracted too much attention, she turned into a baker's shop, and, addressing the pleasant-faced woman behind the counter, said, 'May I have a bun, please, and rest here for half-an-hour until my office opens?'

'Indeed you may, miss, and if you like to step into my parlour you'll find a fire there; it's no weather to be walking about the streets, and none too pleasant for a young lady like you, not but what I say if you show respect to yourself others will show it to you; still, my parlour's the best place on a day like this,' said the baker's wife; for it was a cold, frosty January day.

Stella thanked her kindly Samaritan, who little knew how nervous and miserable her self-contained and dignified visitor felt as she sat there, nor how reluctantly she rose to go to Baines, Jones & Co.'s office.

The junior partner of the firm was not often so punctual at his office as he was on this morning, on which ten o'clock found him sitting in his private room, much to the perturbation of the clerks, who hurried in at or just after the hour of ten.

'There's a lady to see you, sir,' said a young clerk, handing him a card.

'Oh—er, yes; show her into this room,' said the junior partner, with an embarrassment which amazed the clerk, who forthwith went and informed his fellow-clerks that the young boss's best girl had called upon him, and 'he doesn't seem too pleased, though she's handsome enough in all conscience—a regular beauty, and no mistake, and a cut above him too; though what she means by running after him to the City goodness knows!'

'There's no knowing what girls will do nowadays,' said a wise youth of sixteen, who was promptly told to shut up.

But Stella, quite unconscious of these criticisms on her conduct, walked quietly into the junior partner's room, and, bowing gravely, said, 'I am Miss Wharton;' and waited for him to speak.

The junior partner rose from his seat and put a chair for her. 'I am very glad to see you, Miss Wharton. I hope you had a pleasant run—journey south?'

Stella might almost have been carved in stone as she answered, 'Yes, thank you. Will you kindly tell me my duties?'

If her employer felt snubbed he did not show it, but told her what he wanted her to do, and then showed her the room in which she was to work, which was through the clerks' room. Suddenly a thought seemed to strike him. 'There is another door to this room, and by it you could come along the corridor to me when necessary without coming through the clerks' office; and that is the housekeeper's room opposite. She will make you tea, and give you hot water or anything you want,' he said, opening a door on to the corridor.

Stella gravely bowed her thanks. She was grateful for the thought, and she found her new employer very quiet and civil. When the morning was over, and she took him his letters, which he was thankful to find correctly done, he showed his kindness further by saying, 'There is a ladies' club near here where lady-clerks can go and lunch very reasonably and comfortably; the housekeeper will show you the way, if you like. You will find it convenient to stay there till two o'clock; the City is a dull place for young ladies.'

Stella thanked him again, and took his advice; but when she had left the room the junior partner got up, stretched his long limbs, for he was a tall, athletic man, who looked more as if he should have been on a yacht than in a City office. 'Whew! what an iceberg! And to think that that imperial beauty is my clerk, and that I have to give her orders from ten to four, and be repressed and snubbed by her! As if I wanted to take a liberty! Why, I dare not even mention the weather! Well, so be it; she's a good typist, and has a good business head for all it's so pretty.—Well, Mrs. Ryan, what is it? Come in. Did you take Miss Wharton to the Enterprise Club—isn't that its name?'

'Yes, sir, I did, and right glad she was to be in such a place, so bright and comfortable, poor, sweet young lady. But I came to ask you, sir, couldn't she begin at half-past nine and stop at half-past three?' inquired the kind-hearted Irishwoman, explaining about Vava and her hours.

'H'm, it would suit her better, no doubt; but I don't know about me. Oh yes, I could leave her work to do. By all means. Thanks for telling me; I'll arrange it,' said the junior partner kindly, and added, 'And take the little sister into your room if we have not quite finished, Mrs. Ryan; the waiting-room is no place for her, if she is anything like her sister.'

'The City's no place for either of them, Mr. James; but they could not have found a better master than you, go where they might,' said the good woman.

Mr. James laughed; but he did not like to hear himself spoken of as Stella's master, and thought with a grim smile how angry she would have been if she had heard the expression.

The clerks meanwhile had a subject for conversation which kept their tongues wagging in an undertone, to the neglect of their work.

'The new lady-clerk! Who would have believed it? And she gave me her card for all the world like a duchess.' Here there was a snigger, and one of his fellow-clerks asked how duchesses gave their cards. And then the buzz went on, and all were on the qui vive for the door to open; but, as is known, Stella did not pass through the room again, and the next time they met her she was with the housekeeper, to whom she was talking quite pleasantly. So that she could condescend when she liked, they discovered.

All the same, Stella might have been set down as proud and stuck-up, and been more unpopular than she was, though that probably would have troubled her little but for what occurred that afternoon, which, much as it annoyed her, was a very good thing.

The junior partner, it will be remembered, had had to wait for his typist while she packed up and took leave of her Highland home, and then motored leisurely to town, and certain foreign letters had got in arrears, and the junior partner was anxious to get through them.

Consequently, when Vava called for her sister the latter was very busy. The girl knew where the office was, but she did not know which door she ought to knock at; then she saw 'Baines, Jones & Co.—Clerks' Room.' One of the girls at school had called Stella a 'clerk,' when Vava had said 'secretary,' which sounded better. So at this door the girl knocked, and in answer to a loud 'Come in!' she entered.

Twenty heads were lifted and looked at her; but Vava was not self-conscious. She went forward, and with a friendly smile said, 'I have called for my sister. May I sit here till she is ready?'

'Certainly—that is, yes. Take a seat, miss, till I tell the boss,' said a youth, stammering rather, for it was awkward to refuse a young lady; but that was not the place for her to wait.

'No, don't tell any one. Stella said I was not to interrupt her, as she's only a paid servant like you; so just you go on with your work, and don't waste your time like the idle apprentice in the tale.'

Vava had not spoken loud, and did not know that her words were overheard by the whole room; still less was she aware that the young man of about thirty who had come in while she was speaking was the young boss and her sister's employer.

The boy to whom she had spoken had his back to him, and answered in rather an aggrieved tone, 'I'm not wasting my time; I had to answer you, and I must tell Mr. Jones, for I don't know that he'd like you to wait here; this isn't the lady's waiting-room, you know!'

'Mr. Jones won't mind,' said that gentleman, coming forward, and adding, 'So you are Miss Wharton's sister?'

'Yes, but I don't want to be in the way; you all seem very busy. Can I help you? I can write an awfully good hand, just like Stella's; she taught me, you know,' said Vava.

A smile went round the room; but Mr. Jones said quite gravely, 'That is very kind of you, and perhaps when we are hard pressed I shall take advantage of that offer; but your sister has done so much to-day that I think she will soon be ready for you.'

'Oh are you Mr. Jones?' said Vava, holding out her hand. 'I know some more Joneses, only they are'——

'Yes, it's a very common name, almost the commonest in England and Wales—rather a nuisance. But come along with me, and I will take you to your sister,' he said.

'Good-bye,' said Vava, nodding to the boy she had called the 'idle apprentice.'

'So the beauty's name is Stella!' observed one of the young men.

But he got no further. 'Shut up, Jim, and don't be such a cad as to take advantage of that youngster's friendly ways. If ever I hear any of you making free with Miss Wharton's name he'll regret it,' said the clerk in charge of the room, and his feelings on the subject were evidently shared by the rest of his fellow-clerks, for one or two of them said, by way of agreement, 'Yes, she's a nice little girl; evidently just up from the country, and not used to this kind of life, and in mourning too.'

So Stella was allowed to come and go, with no more attention or notice than the raising of their hats as they passed her, and it is to be doubted whether she could at the end of six months have recognised one of them if she had been required for any reason to do so.

Mr. Jones meanwhile took Vava into his own room, and sitting down began to talk to her of her new school and schoolfellows.

'They're all right, and the school is all right, and I like the mistresses, especially the one that takes my class—she looks so honest,' announced Vava.

'Don't the others look honest?' inquired Mr. Jones, looking amused. He had noticed that Vava spoke a little evasively of the school and its pupils as being 'all right,' which sounded qualified praise, and he was, or appeared to be, very much interested in her conversation.

'Oh I don't know; I didn't mean anything. I just liked Miss Courteney's face best, and I shall get to like the girls when I can understand them.' Here Vava laughed. 'They say some words so funnily;' and she tried to imitate them.

Mr. James Jones laughed heartily, and Vava, encouraged by him, was taking off some of her schoolfellows when Stella came to the door. Her face was a study, and both Mr. Jones and Vava jumped up with the air of culprits, as if they had been discovered doing wrong.

'I have brought the letters.—Vava, go into the housekeeper's room, please; you are interrupting Mr. Jones,' said the elder sister, holding open the door 'like an avenging angel,' as the junior partner afterwards said.

When the two girls stood outside the door they turned and looked at each other for a moment, and then without a word Stella led the way down the corridor to her own little room.

Nothing could have had a greater effect upon Vava, who would far rather have had a good scolding than this silent disapproval. 'Is this your sitting-room, Stella? What a nice one, and you have a fire; it has been rather cold at school,' said the girl in a repressed voice as she spread out her hands to the blaze.

Then Stella's heart melted. To be sure, Vava had been very disobedient; she had been told to speak to no one, but to learn her lessons quietly while she was waiting. Instead of which, Stella—remembering the voices she had heard in the next room—felt sure she had been talking in her free way with every one. Still, it was their first day alone in London, and Vava looked so unlike herself with the joy and brightness gone out of her face, so she said kindly, if gravely, 'Yes, this is my room, and another time, please, come straight here, unless I come and call for you, which would be better, I think, if you do not obey me. But let me hear about school. I hope they have fires there?'

'Oh yes, but I was sitting near a window, and my feet and hands got cold with having to sit still so long, I suppose; the girls say they get chilblains as soon as they come back to school,' replied Vava.

'You must wear mittens and warm house-shoes. But about the school, Vava—do you like it? Are you glad to go to school?'

'Not much; but, Stella, don't send me away from you. I will do what you tell me, really; I promise I will, unless I forget. I forgot to-day, or I would not have talked to any one. I know you're awfully angry with me; but I think I was a little flustered by all the crowds in the streets, and I just went into the first room where I saw Baines, Jones & Co. written!' cried Vava eagerly.

'I understand that you were bewildered; but you must try and remember that you are not at Lomore, and that you must not make friends without my leave, or else I shall feel that I cannot take care of you, and that it's not right to keep you with me,' said Stella.

'Then I shall die in this dreadful place without you,' declared Vava in tragic tones.

'Vava, something has happened. What is it? What has made you take such a dislike to London? You liked it well enough yesterday,' exclaimed Stella anxiously. She had been putting on her hat and coat as she spoke, and had just said this, when Mrs. Ryan, the housekeeper, came in with a tray, on which there were two cups of tea and delicious thin bread and butter and cakes.

'I have brought you a warm cup of tea to keep the cold out on your way home, and one for this young lady, who is your sister, as is plain to see. Dear, dear! and to think of you two poor lambs all alone! My dear, don't be offended with me; but if, as you say, you have no relations or friends in London, I hope you'll count me as one, and come to me if you are in any trouble, just as if I were'—a fine tact made the old Irishwoman say, 'your old housekeeper,' instead of 'your mother.'

Stella held out her hand and smiled. 'Thank you, Mrs. Ryan; indeed you are a friend, and I will come to you for advice,' she said.

'And, do you know, you remind me a little of nursie, our housekeeper at Lomore, only she is Scotch; but I can understand your way of speaking, and that's more than I can the people at school,' Vava remarked, with such a tone of disgust that the other two laughed.

But Stella looked relieved. 'So that's it, is it? I suppose they laughed at you for talking with a Scotch accent? I have often told you, Vava, that you should not copy old Duncan as you did,' protested Stella; for Vava talked much broader Scotch than Stella, and used words which are not in use or understood south of the Border.

'They're stupid things, and I don't want to talk like them. Anyway, they don't pronounce lots of their words right; they say "wat" and "ware" for "what" and "where;" so of course I got a lot of mistakes in my English dictation. But I beat them in my French,' she wound up triumphantly.

'You'll soon get used to that, miss, and there isn't a better school in London than the one you're at; there's no money spared on it, for it's a rich company that has it, though I don't know exactly why they have it,' said Mrs. Ryan.

'I do; a rich merchant's wife founded it!' cried Vava, and poured forth the history of the foundation of the school to her two listeners, till Stella stopped her.

'Now, Vava, we must not keep Mrs. Ryan.—My sister does not understand that the City is the place for business, not for paying visits or amusing one's self; and you might tell her that she must not make acquaintance with strangers,' said Stella, turning to Mrs. Ryan.

Mrs. Ryan raised her hands in amazement at such imprudence. 'Indeed no. There was a young girl I knew up from the country, and one day she was taking her ticket at one of the London stations, and there was rather a crowd, so, being timid, she stepped back and waited; then who should come up to her but a gentleman, as she called him, and, taking off his hat as polite as could be, says, "Can I take your ticket for you, miss? It's not fit for you to be pushing into a rough crowd like that;" and she, like the silly she was, thanks him and hands him her purse with all her week's money in it; and off he goes.' Here Mrs. Ryan ended, and nodded her head at Vava.

But Vava in her innocence did not understand the moral of the story, and said simply, 'That was very kind of him?'

'Yes, very kind! But he never got the ticket, and the poor girl never saw her purse nor the kind gentleman again,' explained Mrs. Ryan.

Vava's eyes were wide with horror. 'What a wicked, cruel man! But everybody can't be wicked like that!' she cried.

'No, indeed; thank God, there are many good people here; but there are rogues as well, and as you are too young to know the one from the other you must not talk to any of them,' Mrs. Ryan said.

The story made Vava very thoughtful. 'I wonder whether Mr. Jones is a rogue?' she said musingly.

But Mrs. Ryan was scandalised. 'Sakes alive, miss, don't say such a thing in his own office! He is one of the best and most respected gentlemen in the City of London, as I well know, having worked for him and his father this thirty years!' she exclaimed.

'Vava lets her tongue run away with her.—Come, Vava, we really must be going,' said Stella hastily, and she took her younger sister off with her.

It was dusk now, but the two enjoyed their walk back along the Embankment, for it did not occur to them to take a bus or train; three miles was nothing to them. Moreover, they had had tea, and were in no hurry to get back to their cramped lodgings. It was well that Vava could not see her sister's amused smile, which broke out several times on the way home at the remembrance of the younger girl's suggestion that the junior partner might be a rogue; and it is to be feared that Stella would not have been sorry if her employer—whom she suspected unjustly of thinking a good deal of himself and of wishing to patronise her and pity her for having 'come down in the world'—had heard Vava's remark.

It might have gratified her if she had known that Mrs. Ryan went straight to her master and told him the whole story.

Mr. James, as she called him, laughed heartily. 'I'm sure that's what her elder sister thinks me. Well, it does not much matter, as long as she does her work as well as she did to-day, so business-like and correctly—first accurate young woman I have ever met with; and the poor thing will have a better time here than she would with many firms. You will be sure to look after her well, Mrs. Ryan? My father is most particular that she should be comfortable—as comfortable as possible, that is to say; so be sure and give her tea before she goes, or anything she wants.'

From which conversation it will be seen that Mr. Stacey had found a good berth for his young client, and had evidently given her a high testimonial.

It was six o'clock by the time the girls reached Vincent Street, and they seated themselves on uncomfortable arm-chairs in front of the smoky fire, which they lit as soon as they got in. Vava had her lessons to do; but after their tea-supper, for which the landlady declined to cook anything but eggs—'London eggs,' as Vava said—Stella looked round for something to do. There was no piano, she had no books, nor was she fond of fancy-work, and of useful work she had none, for 'nursie' had always done most of the mending for her young ladies, though she had taught them both to work. Before they left home she had set their wardrobes in thorough order. 'So that you'll not have to trouble about them for a long while yet; and perhaps, who knows, the Lord may have made a way for me to come to you before they need looking to again,' the old woman had said, with some kind of idea that her beautiful young mistress would not somehow be left by Providence in a position for which she was so unfitted, in the old housekeeper's opinion.

So now Stella looked round for something to do, and finding nothing, passed a dreary evening, till Vava had finished preparing her lessons, and said with a yawn, 'Let's go to bed, Stella. What's the good of sitting up, staring at this horrid wall-paper with those hideous flowers that aren't like any flowers that ever grew in a garden?'

Stella gave a sigh, which, in spite of all her resolutions to be brave, she could not suppress. 'It is not very comfortable here, to be sure; but I don't know where else to go. There is a large kind of ladies' residential club near here, but I do not know if we should like it, and we should have no private sitting-room; so you would have to prepare your lessons in your bedroom, which I dislike,' she replied.

'Oh that would be horrid; the room would get so hot and stuffy, and we should not sleep. I wish we could have a little house of our own. I am sure there must be little houses to let that we could afford, like the one Dr M'Farlane's sisters lived in at Lomore.'