Most of the characters in this tale are from life, and some of the main events are historical, although the actual scenes and names are not given. Many men now living will remember Fighting Bill Kenna and the Horse Preacher, as well as the Fort Ryan races. These horse races are especially well known and have been described in print many times. I did not witness any of them myself, but listened on numerous occasions when they were described to me by eye-witnesses. My first knowledge of the secret try-out in Yellowbank Canyon was given to me years ago by Homer Davenport, the cartoonist, with permission to use the same.

But all of these more or less historic events are secondary to the intent of illustrating the growth of a character, whose many rare gifts were mere destructive force until curbed and harmonized into the big, strong machine that did such noble work in the West during my early days on the Plains.

Ernest Thompson Seton.

BOOK ONE The Child of the Stable Yard

CHAPTER I. The Home Land of Little Jim Hartigan

CHAPTER II. The Strains That Were Mingled in Jim

CHAPTER III. How He Lost His Father

CHAPTER IV. The Atmosphere of His Early Days

CHAPTER V. Little Jim's Tutors

CHAPTER VI. Jim Loses Everythin

CHAPTER VII. He Gets a Much-needed Lesson

BOOK II The Conversion

CHAPTER VIII. The Conversion of Jim

CHAPTER IX. Jim Hartigan Goes to College

CHAPTER X. Escape to Cedar Mountain

CHAPTER XI. A New Force Enters His Life

CHAPTER XII. Belle Boyd

CHAPTER XIII. Preacher Jim's First Sermon

CHAPTER XIV. The Lure of the Saddle

CHAPTER XV. Pat Bylow's Spree

CHAPTER XVI. The New Insurance Agents

CHAPTER XVII. Belle Makes a Decision and Jim Evades One

CHAPTER XVIII. The Second Bylow Spree

CHAPTER XIX. The Day of Reckoning

CHAPTER XX. The Memorable Trip to Deadwood

CHAPTER XXI. The Ordeal

CHAPTER XXII. The Three Religions Confront Him

BOOK III The Horse Preacher

CHAPTER XXIII. Blazing Star

CHAPTER XXIV. Red Rover

CHAPTER XXV. The Secret of Yellowbank Canyon

CHAPTER XXVI. Preparing for the Day

CHAPTER XXVII. The Start

CHAPTER XXVIII. The Finish

CHAPTER XXIX. The Riders

CHAPTER XXX. The Fire

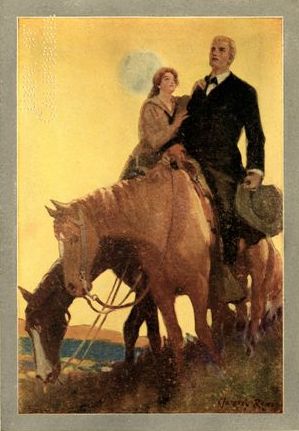

CHAPTER XXXI. Love in the Saddle

BOOK IV The Horse Preacher Afoot

CHAPTER XXXII. The Advent of Midnight

CHAPTER XXXIII. The Sociable

CHAPTER XXXIV. Springtime

CHAPTER XXXV. When the Greasewood is in Bloom

CHAPTER XXXVI. Shoeing the Buckskin

CHAPTER XXXVII. The Boom

CHAPTER XXXVIII. When the Craze Struck

CHAPTER XXXIX. Jim's Bet

CHAPTER XL. The Crow Band

CHAPTER XLI. The Pinto

CHAPTER XLII. The Aftertime

CHAPTER XLIII. Finding the Lost One

CHAPTER XLIV. A Fair Rider

CHAPTER XLV. The Life Game

CHAPTER XLVI. What Next?

CHAPTER XLVII. Back to Deadwood

CHAPTER XLVIII. The Fork in the Trail

CHAPTER XLIX. The Power of Personality

CHAPTER L. The Call to Chicago

CHAPTER LI. These Little Ones

CHAPTER LII. The Boss

CHAPTER LIII. The First Meeting

CHAPTER LIV. The Formation of the Club

BOOK V The Call of the Mountain

CHAPTER LV. In the Absence of Belle

CHAPTER LVI. The Defection of Squeaks

CHAPTER LVII. The Trial

CHAPTER LVIII. In the Death House

CHAPTER LIX. The Heart Hunger

CHAPTER LX. The Gateway and the Mountain

CHAPTER LXI. Clear Vision on the Mountain

CHAPTER LXII. When He Walked with the King

BOOKS BY ERNEST THOMPSON SETON

BY MRS. ERNEST THOMPSON SETON

A burnt, bare, seared, and wounded spot in the great pine forest of Ontario, some sixty miles northeast of Toronto, was the little town of Links. It lay among the pine ridges, the rich, level bottomlands, and the newborn townships, in a region of blue lakes and black loam that was destined to be a thriving community of prosperous farmer folk. The broad, unrotted stumps of the trees that not so long ago possessed the ground, were thickly interstrewn among the houses of the town and in the little fields that began to show as angular invasions of the woodland, one by every settler's house of logs. Through the woods and through the town there ran the deep, brown flood of the little bog-born river, and streaking its current for the whole length were the huge, fragrant logs of the new-cut pines, in disorderly array, awaiting their turn to be shot through the mill and come forth as piles of lumber, broad waste slabs, and heaps of useless sawdust.

Two or three low sawmills were there, each booming, humming, busied all the day. And the purr of their saws, or the scream when they struck some harder place in the wood, was the dominant note, the day-long labour-song of Links. At first it seemed that these great, wasteful fragrant, tree-destroying mills were the only industries of the town; and one had to look again before discovering, on the other side of the river, the grist mill, sullenly claiming its share of the water power, and proclaiming itself just as good as any other mill; while radiating from the bridge below the dam, were the streets—or, rather, the rough roads, straight and ugly—along which wooden houses, half hidden by tall sunflowers, had been built for a quarter of a mile, very close together near the bridge, but ever with less of house and sunflower and more of pumpkin field as one travelled on, till the last house with the last pumpkin field was shut in by straggling, much-culled woods, alternating with swamps that were densely grown with odorous cedar and fragrant tamarac, as yet untouched by the inexorable axe of the changing day.

Seen from the road, the country was forest, with about one quarter of the land exposed by clearings, in each of which were a log cabin and the barn of a settler. Seen from the top of the tallest building, the sky line was, as yet, an array of plumy pines, which still stood thick among the hardwood trees and, head and shoulders, overtopped them.

Links was a town of smells. There were two hotels with their complex, unclean livery barns and yards, beside, behind, and around them; and on every side and in every yard there were pigs—and still more pigs—an evidence of thrift rather than of sanitation; but over all, and in the end overpowering all, were the sweet, pervading odour of the new-sawn boards and the exquisite aroma of the different fragrant gums—of pine, cedar, or fir—which memory will acknowledge as the incense to conjure up again in vivid actuality these early days of Links.

It was on a sunny afternoon late in the summer of 1866 that a little knot of loafers and hangers-on of the hotels gathered in the yard of the town's larger hostelry and watched Bill Kenna show an admiring world how to ride a wild, unbroken three-year-old horse. It was not a very bad horse, and Bill was too big to be a wonderful rider, but still he stayed on, and presently subdued the wild thing to his will, amid the brief, rough, but complimentary remarks of the crowd.

One of the most rapt of the onlookers was a rosy-cheeked, tow-topped boy of attractive appearance—Jim; who though only eight years old, was blessed with all the assurance of twenty-eight. Noisy and forward, offering suggestions and opinions at the pitch of his piping voice, he shrieked orders to every one with all the authority of a young lord; as in some sense he was, for he was the only son of "Widdy" Hartigan, the young and comely owner and manager of the hotel.

"There, now, Jim. Could ye do that?" said one of the bystanders, banteringly.

"I couldn't ride that 'un, cause me legs ain't long enough to lap round; but I bet I could ride that 'un," and he pointed to a little foal gazing at them from beside its dam.

"All right, let him try," said several.

"And have his brains kicked out," said a more temperate onlooker.

"Divil a bit," said big Bill, the owner of the colt. "That's the kindest little thing that ever was born to look through a collar," and he demonstrated the fact by going over and putting his arms around the young thing's gentle neck.

"Here, you; give me a leg up," shouted Jimmy, and in a moment he was astride the four-month colt.

In a yard, under normal kindly conditions, a colt may be the gentlest thing in the world, but when suddenly there descends upon its back a wild animal that clings with exasperating pertinacity, there is usually but one result. The colt plunged wildly, shaking its head and instinctively putting in practice all the ancient tricks that its kind had learned in fighting the leopard or the wolf of the ancestral wild horse ranges.

But Jim stuck on. His legs, it was true, were not long enough to "lap round," but he was a born horseman. He had practised since he was able to talk, never losing a chance to bestride a steed; and now he was in his glory. Round and round went the colt, amid the laughter of the onlookers. They apprehended no danger, for they knew that the youngster could ride like a jackanapes; in any case the yard was soft with litter, and no harm could happen to the boy.

The colt, nearly ridden down, had reached the limit of its young strength, and had just about surrendered. Jim was waving one hand in triumph, while the other clutched the fuzzy mane before him, when a new and striking element was added to the scene. A rustle of petticoats, a white cap over yellow hair, a clear, commanding voice that sent the men all back abashed, and the Widdy Hartigan burst through the little circle.

"What do ye mean letting me bhoy do that fool thing to risk his life and limb? Have ye no sense, the lot of ye? Jimmy, ye brat, do ye want to break yer mother's heart? Come off of that colt this holy minute; or I'll—"

Up till now, Jim had been absolute dominator of the scene; but the powerful personality of his mother shattered his control, dethroned him.

As she swept angrily toward him, his nerve for the time was shaken. The colt gave a last wild plunge; Jim lost his balance and his hold, and went down on the soft litter.

As it sprang free from its tormenter, the frightened beast gave vent to its best instinctive measure of defense and launched out a final kick. The youngster gave a howl of pain, and in a minute more he was sobbing in his mother's arms, while one of the crowd was speeding for the doctor.

Yes, the arm was broken above the elbow, a simple fracture, a matter of a month to mend. The bone was quickly set, and when his wailing had in a measure subsided, Jim showed his horseman soul by jerking out: "I could have rode him, Mother. I'll ride him yet. I'll tame him to a finish, the little divil."

Clearly one cannot begin the history of the French Revolution with the outbreak of 1789. Most phenomena, physical and spiritual, have their roots, their seeds, their causes—whatever you will—far behind them in point of time. To understand them one must go back to the beginning or they will present no logic or raison d'être. The phenomenon of James Hartigan, the Preacher of Cedar Mountain, which is both a physical and a spiritual fact, is nowise different, and the reader must go back with me to some very significant events which explain him and account for him.

Little Jim's father was James O'Hartigan in Donegal. The change in the patronymic was made, not by himself, but by the Government Emigration Agent at Cork. When James, Sr. came forward to be listed for passage, the official said: "Oh, hang your O's. I have more of them now than the column will hold. I'll have to put you in the H's, where there's lots of room." And so the weight of all the Empire was behind the change.

James Hartigan, Sr. was a typical Irish "bhoy," which is high praise. He was broad and hearty, with a broad and hearty grin. He was loved and lovable, blessed with a comely countenance and the joy of a humorous outlook on life and its vicissitudes. You could not down Jimmy so low that he might not see some bright and funny aspect in the situation. This was not only a happy temperamental trait, but it also had a distinct advantage, for in the moments of deepest self-invited degradation he never forgot that somewhere ahead, his trail would surely lead to the uplands once again.

He was what the doctors called "normal human," muscled far above the average, heart action strong and regular. This combination often produces two well-marked types—a high-class athlete and a low-class drunkard. Often these are united in the same individual; or, rather, the individual appears in the first rôle, until the second comes to overmaster it. Such was Jimmy Hartigan, Sr., whose relation to the Preacher may be labelled Cause Number One.

Those who knew her people said that the forbears of Katherine Muckevay had seen better days; that the ancient royal blood of Ireland ran in her veins; that the family name was really Mach-ne-veagh; and that, if every one had his own, Kitty would be wearing a diamond tiara in the highest walks of London importance. In ancient days, the Kings of Ulster used to steal a bride at times from the fair-haired folk across the sea; maybe that was where Kitty got her shining hair of dusty yellow-red, as well as the calm control in times of stress, something the psychologists call coördination, which is not a Celtic characteristic.

Of book learning Kitty had almost none, but she had native gifts. She had wits, good looks, and a wealth of splendid hair, as well as a certain presence which was her perpetual hedge of safety, even when she took the perilous place of maid in the crude hotel with its bar-room annex, whither the hand of Fate had brought her, an Irish immigrant, to find a new life in the little town of Links. Kitty was Cause Number Two.

Jimmy did not chance to cross on the same ship. But the time had come; and by chance, which is not chance at all, he drifted into the same corner of Canada, and had not half a day to wait before he was snapped up by a local farmer seeking for just such a build of man to swing the axe and scythe upon his farm.

Farm life is dreary enough, at least it was in those days. It was hard work from dawn to dusk, and even then the feeble, friendly glimmer of a caged candle was invoked to win an extra hour or two of labour from the idleness of gloom—hours for the most part devoted to the chores. The custom of the day gave all the hired ones freedom Saturday night and all day Sunday. Wages were high, and with one broad epidemic impulse all these thriving hirelings walked, drove, or rode on Saturday night to the little town of Links. Man is above all a social animal; only the diseased ones seek solitude. Where, then, could they meet their kind?

The instinct which has led to the building of a million clubs, could find no local focus but the bar-room. John Downey's "hotel" was the social centre of the great majority of the men who lived and moved around the town of Links. Not the drink itself, but the desire of men to meet with men, to talk and swap the news or bandy mannish jokes, was the attracting force. But the drink was there on tap and all the ill-adjusted machinery of our modern ways operated to lead men on, to make abstainers drink, to make the moderate, drunken.

If the life in Downey's stable, house, and bar were expanded in many chapters, the reader would find a pile of worthless rubbish, mixed with filth, but also here and there a thread of gold, a rod of the finest steel, and even precious jewels. But this is not a history of the public house. Downey's enters our list merely as Cause Number Three.

Those who study psychological causation say that one must find four causes, accounting for place, matter, force, and time. The three already given are well known, and I can only guess at the fourth, that referring to the time. If we suppose that a sea pirate of a thousand years ago, was permitted to return to earth, to prove that he had learned the lessons of gentleness so foreign to his rapacious modes of thought, and that, after a thousand years of cogitation in some disembodied state, he was allowed to reassume the flesh, to fight a different fight, to raise himself by battle with himself, we shall, perhaps, account for some of the strangely divergent qualities that met in the subject of this story. At least, let us name the ancient Sea-king as Cause Number Four.... And conjunction of these four was affected in the '50s at Downey's Hotel, when Jim Hartigan met Kitty Muckevay.

These were the strains that were mingled in little Jim; and during his early life from the first glimpse we catch of him upon the back of the unbroken colt, he was torn by the struggle between the wild, romantic, erratic, visionary, fighting Celt, with moods of love and hate, and the calmer, steady, tireless, lowland Scottish Saxon from the North who, far less gifted, had far more power and in the end had mastery; and having won control, built of his mingled heritages a rare, strong soul, so steadfast that he was a tower of strength for all who needed help.

The immediate and physical environment of Links was the far backwoods of Canada, but the spirit and thought of it were Irish. The inhabitants were nearly all of Irish origin, most of them of Irish birth, and the fates had ruled it so that they came from all parts of the green isle. The North was as well represented as the South, and the feuds of the old land were most unprofitably transferred to the new.

Two days on the calendar had long been set aside by custom for the celebration of these unhappy feuds; the seventeenth of March, which is St. Patrick's Day, and the twelfth of July, on which, two hundred years before, King William had crossed the river to win the famous Battle of the Boyne. Under the evil spell of these two memorable occasions, neighbours who were good and helpful friends, felt in honour bound to lay all their kindness aside twice every year, and hate and harass each other with a senseless vindictiveness.

At the time with which this chronicle has to do, Orange Day had dawned on Links. No rising treble issued from the sawmills; the air was almost free of their dust, and there were hints of holiday on all the town. Farmers' wagons were arriving early, and ribbons of orange and blue were fastened in the horses' headgear. From the backyard of Downey's Hotel the thumping of a big drum was heard, and the great square piles of yellow lumber near Ford's Mill gave back the shrilling of fifes that were tuning up for the event. As the sun rose high, the Orangemen of the Lodge appeared, each wearing regalia—cuffs and a collarette of sky-blue with a fringe of blazing orange, or else of gold, inscribed with letters and symbols.

The gathering place was in the street before the Lodge Hall, and their number was steadily increased by men from the surrounding farms. The brethren of the opposite faith, the Catholics—more often called "Dogans" or "Papists"—were wisely inconspicuous. Had it been their day, their friends, assembled from far places, would have given them numbers enough for safety and confidence; but now the boys in green were, for the most part, staying at home and seeking to avoid offence.

In the stable yard of Downey's Hotel, where Jim Hartigan—the father of our hero—and several others of his Church were disconsolately looking forward to a dreary and humiliating day, the cheery uproar of the Orangemen in the bar-room could plainly be heard. James himself was surprised at his restraint in not being there too, for he was a typical Irish "bhoy" from the west coast, with a religion of Donegal colour and intensity. Big, hearty, uproarious in liquor, and full of fun at all times, he was universally beloved. Nothing could or did depress Jim for long; his spirits had a generous rebound. A boisterous, blue-eyed boy of heroic stature, he was the joy of Downey's, brim-full of the fun of life and the hero of unnumbered drinking bouts in the not so very distant past. But—two months before—Jim had startled Links and horrified his priest by marrying Kitty Muckevay of the gold-red hair. Kitty had a rare measure of good sense but was a Protestant of Ulster inflexibility. She had taken Jim in hand to reform him, and for sixty days he had not touched a drop! Moreover he had promised Kitty to keep out of mischief on this day of days. All that morning he had worked among the horses in Downey's livery stable where he was head man. It was a public holiday, and he had been trying desperately to supply a safety valve for his bursting energy. His excitible Irish soul was stirred by the murmur of the little town, now preparing for the great parade, as it had been stirred twice every year since he could remember, but now to the farthest depths.

He had swallowed successfully one or two small affronts from the passing Orangemen, because he was promise-bound and sober; but when one of the enemy, a boon companion on any other day, sought him out in the stable yard and, with the light of devilment in his eyes, walked up holding out a flask of whiskey and said: "Hartigan! Ye white-livered, weak-need papist, ye're not man enough to take a pull at that, an' tip the hat aff of me head!" Hartigan's resolutions melted like wax before the flare of his anger. Seizing the flask, he took a mouthful of the liquor and spurted it into the face of the tormentor. The inevitable fight did not amount to much as far as the casualties went, but what loomed large was the fact that Hartigan had filled his mouth with the old liquid insanity. Immediately he was surrounded by those who were riotously possessed of it, and in fifteen minutes Jimmy Hartigan was launched on the first drunken carouse he had known since he was a married man in public disgrace with the priest for mating with a Protestant.

The day wore on and the pace grew faster. There were fun and fighting galore, and Jimmy was in his element again. Occasional qualms there were, no doubt, when he had a moment to remember how Kitty would feel about it all. But this was his day of joy—mad, rollicking, bacchanalian joy—and all the pent-up, unhallowed hilarity of the bygone months found vent in deeds more wild than had ever been his before.

The Orangemen's procession started from their lodge, with three drums and one fife trilling a wheezing, rattling manglement of "Croppies Lie Down," whose only justification lay in the fact that it was maintaining a tradition of the time; and Jimmy Hartigan, besieged in the livery yard with half a dozen of his coreligionists, felt called upon to avenge the honour of the South of Ireland at these soul-polluting sounds. Someone suggested a charge into the ranks of the approaching procession, with its sizzling band and its abhorrent orange-and-blue flags, following in the wake of Bill Kenna, whose proud post was at the head of the procession, carrying a cushion on which was an open Bible. The fact that Bill was a notorious ruffian—incapable of reading, and reeling drunk—had no bearing on his being chosen as Bible carrier. The Bible fell in the dust many times and was accidentally trampled on by its bearer, which was unfortunate but not important. Bill bore the emblem of his organization and, being a good man with his fists, he was amply qualified for his job.

But the sight of all this truculence and the ostentatious way in which the little green flags were trampled on and insulted, was too much for Jimmy and his inspired companions.

"Let's charge the hull rabble," was the suggestion.

"What! Six charge one hundred and twenty!"

"Why not?"

The spirit of Gideon's army was on them, and Jimmy shouted: "Sure, bhoys, let's hitch to that and give it to 'em. Lord knows their black souls need it." He pointed to a great barrel half full of whitewash standing in a wagon ready for delivery next day at the little steamer dock, where a coat of whitewash on the wharf and shed was the usual expedient to take the place of lights for night work.

Thus it came about. The biggest, strongest team in the stable was harnessed in a minute. The men were not too drunk to pick the best in horses and harness. The barrel was filled brim-full with water and well stirred up, so that ammunition would be abundant. Jimmy was to be the driver; the other five were each armed with a bucket, except one who found a force pump through which the whitewash could be squirted with delightful precision. They were to stand around the barrel and dash its contents right and left as Jimmy drove the horses at full speed down the middle of the procession. Glorious in every part was the plan; wild enthusiasm carried all the six away and set the horses on their mettle.

Armed with a long, black snake whip, Jimmy mounted the wagon seat. The gate was flung wide, and, with a whoop, away went that bumping chariot of splashing white. Bill Kenna had just dropped his Bible for the eleventh time and, condemning to eternal perdition all those ill-begotten miscreants who dared to push him on or help his search, he held the ranks behind him for a moment halted. At this instant with a wild shout, in charged Jim Hartigan, with his excited crew. There was not a man in the procession who had not loved Hartigan the day before, and who did not love him the day after; but there was none that did not hate him with a bitter hate on this twelfth day of July, as he charged and split the procession wide open.

The five helpers dashed their bewildering, blinding slush fast and far, on every face and badge that they could hit; and the pump stream hit Kenna square in the face as he yelled in wrath. The paraders were not armed for such a fight. Men that could face bullets, knives, and death, were dismayed, defeated, and routed by these baffling bucketfuls and the amazing precision of the squirting pump.

Strong hands clutched at the bridle reins, but the team was plunging and going fast. The driver was just drunk enough for recklessness; he kept the horses jumping all down that Orangemen's parade. Oh, what a rout it made! And the final bucketfuls were hurled in through the window of the Orange Lodge, just where they were needed most, as Jimmy and his five made their escape.

The bottle now went round once more. Shrieking with laughter at their sweeping, bloodless victory, the six Papists saw the procession rearrayed. Kenna had recovered and wiped his face with one coat sleeve, his Bible with the other. The six dispensers of purity could not resist it; they must charge again. Hartigan wheeled the horses to make the turn at a run. But with every circumstance against him—speed and reckless driving, a rough and narrow roadway beset with stumps—the wagon lurched, crashed, upset, and the six went sprawling in the ditch. The horses ran away to be afterward rounded up at a farm stable three miles off, with the fragments of a wagon trailing behind them.

The anger of the Orangemen left them as they gathered around. Five of the raiders were badly shaken and sobered, one lay still on the stones, a deep and bloody dent in his head. The newly arrived, newly fledged doctor came, and when after a brief examination, he said: "He's dead—all right," there was a low, hollow sound of sympathy among the men who ten minutes before would gladly have killed him. One voice spoke for all the rest.

"Poor lad! He was a broth of a bhoy! Poor little Widdy Hartigan."

There were many surprises and sharp contrasting colour spots on the map of the "Widdy's" trail for the next nine years. With herself and the expected child to make a home for after that mad Orange Day, she had sought employment and had been welcomed back to the hotel where she had ever been a favourite.

The little room above the kitchen which projected over the yard was her only resting place. The cheapest, simplest of wooden furniture was all it held. On a tiny stand, made of a packing case, was her Bible and, hanging over it a daguerreotype of her husband—his frank, straight gaze and happy face looking forth with startling reality. Outside and very near, for the building was low, the one window looked upon the yard of the hotel, with its horses, its loafers, its hens and its swine; while just above the shutter's edge a row of swallows had their nests, where the brooding owners twittered in the early summer morning, as she rose with the sunrise and went about her work. A relief at first, the duties Kitty had undertaken grew heavier with the months, till at last the kindly heart of the owner's wife was touched, and a new régime of rest ensued.

Eight months after that fatal Orange Day, James Hartigan, Jr., was born in the little room over the yard; and baby wailings were added to the swallows' chirps and the squeals of pigs. Mother Downey, rough and rawboned to the eye, now appeared in guardian-angel guise, and the widow's heart was deeply touched by the big, free kindness that events had discovered in the folk about her. Kitty was of vigorous stock; in a week she was up, in a fortnight seemed well; and in a month was at her work, with little Jim—named for his father and grandfather—in hearing, if not in sight.

Then, quite suddenly, Mrs. Downey died. A big, gaunt woman, she had the look of strength; but the strength was not there; and a simple malady that most would have shaken off was more than she could fight. With her husband and Kitty by the bed, she passed away; and her last words were: "Be good—to—Kitty, John—and—Little Jim."

It was an easy promise for John Downey to give and a pleasant undertaking to live up to. Before his wife had been dead three months, John Downey had assured Kitty that she might become Mrs. Downey Number Two as early as she pleased. It was not by any means the first offer since her loss. Indeed, there were few free men in Links who would not have been glad to marry the winsome, young, energetic widow.

But all her heart was on her boy, and until she could see that it was best for him she would take no second partner. Downey's proposal was a puzzle to her; he was a big, strong, dull, moderately successful, unattractive man. But he had a good business, no bad habits, and was deeply in love with her.

It was the thought of little Jim that settled it. Downey showed genuine affection for the child. To give him a father, to have him well educated—these were large things to Kitty and she consented. As soon as the late Mrs. Downey should have been laid away for six months, the wedding was to be and Kitty moved to other lodgings meanwhile. But Fate's plans again disagreed with Kitty's. A few weeks after her consent, the town was startled by the news that John Downey was dead. A cold—neglect (for he did not know how to be sick), and pneumonia. The folk of the town had much to talk of for a day, and the dead man's will gave still higher speed to their tongues, for he had left the hotel and all its appurtenances to Widdy Hartigan, as a life interest; after her death it was to go to a kinsman. Thus, out of John Downey's grave there grew a tree with much-needed and wholesome fruit.

Now Kitty was in a quandary. She was an abstainer from choice rather than principle; but she was deeply imbued with the uncompromising religion of her Ulster forbears. How could she run a bar-room? How could she, who had seen the horror of the drink madness, have a hand in setting it in the way of weak ones? Worst dilemma of all, how could she whose religious spirit was dreaming of a great preacher son, bring him up in these surroundings—yet how refuse, since this was his only chance?

She consulted with her pastor; and this was the conclusion reached: She would accept the providential bequest. Downey's would be an inn, a hotel; not a bar-room. The place where the liquor was sold should be absolutely apart, walled off; and these new rules were framed: No minor should ever be served there, no habitual drunkard, no man who already had had enough. Such rules in Canada during the middle of last century were considered revolutionary; but they were established then, and, so far as Kitty could apply them, they were enforced; and they worked a steady betterment.

With this new responsibility upon her, the inborn powers of Kitty Hartigan bloomed forth. Hers was the gift of sovereignty, and here was the chance to rule. The changes came but slowly at first, till she knew the ground. A broken pane, a weak spot in the roof, a leaky horse trough, and a score of little things were repaired. Account books of a crude type were established, and soon a big leak in the treasury was discovered and stopped; and many little leaks and unpaid bills were unearthed. An aspiring barkeeper of puzzling methods was, much to his indignation, hedged about by daily accountings and, last of all, a thick and double door of demarcation was made between the bar-room and the house. One was to be a man's department, a purely business matter; the other a place apart—another world of woollen carpets and feminine gentleness, a place removed ten miles in thought. The dwellers in these two were not supposed to mix or even to meet, except in the dining room three times a day; and even there some hint of social lines was apparent.

In former times the hotel had been a mere annex of the bar-room. Now the case was reversed; the bar-room became the annex. The hotel grew as Kitty's power developed. Good food temptingly served brought many to the house who had no interest in the annex. Her pies made the table famous and were among the many things that rendered it easy to displace the brown marbled oilcloth with white linen, and the one roller towel for all, with individual service in each room.

In this hotel world the alert young widow made her court and ruled as a queen. Here little Jim slept away his babyhood and grew to consciousness with sounds of coming horses, going wheels; of chicken calls and twittering swallows in their nests; shouts of men and the clatter of tin pails; the distant song of saw mills and their noontide whistles; smells of stables mixed with the sweet breathings of oxen and the pungent odour of pine gum from new-sawn boards.

And ever as he grew, he loved the more to steal from his mother's view and be with the stable hands—loving the stable, loving the horses, loving the men that were horsemen in any sort, and indulged and spoiled by them in turn. The widow was a winner of hearts whom not even the wife of Tom Ford, the rich millman and mayor of the town, could rival in social power, so Jim, as the heir apparent, grew up in an atmosphere of importance that did him little good.

"Whiskey" Mason had been for more than three years with Downey. He was an adroit barkeep. He knew every favourite "mix" and how to use the thickest glasses that would ever put the house a little more ahead of the game. But the Widow soon convinced herself that certain rumours already hinted at were well-founded, and that Mason's salary did not justify his Sunday magnificence. Mason had long been quite convinced that he was the backbone of the business and absolutely indispensable. Therefore he was not a little surprised when the queen, in the beginning of her reign, invited him to resign his portfolio and seek his fortune elsewhere, the farther off the better to her liking.

Mason went not far, but scornfully. He took lodgings in the town to wait and see the inevitable wreck that the widow was inviting for her house. For two months he waited, but was disappointed. The hotel continued in business; the widow had not come to beg for his return; his credit was being injured with excessive use; and as he had found no other work, he took the stage to the larger town of Petersburg some thirty miles away. Here he sought a job, in his special craft of "joy mixer" but, failing to find that, he turned his attention to another near akin. In those days the liquor laws of Canada provided a heavy fine for any breach of regulation; and of this the informant got half. Here was an easy and honourable calling for which he was well equipped.

It has ever been law in the man's code that he must protect the place he drinks in, so that the keepers of these evil joints are often careless over little lapses. Thus Whiskey Mason easily found a victim, and within three days was rich once more with half of the thousand-dollar fine that the magistrate imposed.

He felt that all the country suddenly was his lawful prey. He could not long remain in Petersburg, where he was soon well known and shunned. He had some trouble, too, for threats against his life began to reach him more and more. It was the magistrate himself who suggested contemptuously, "You had better take out a pistol license, my friend; and you would be safer in a town where no one knows you."

In those early days before his dismissal by Kitty, Mason's life and Little Jim's had no point of meeting. Six years later, when he returned to Links, Jimmy was discovering great possibilities in the stables of the Inn. Mason often called at the bar-room where he had once been the ruling figure, and was received with cold aloofness. But he was used to that; his calling had hardened him to any amount of human scorn. He still found a kindred spirit, however, in the stable man, Watsie Hall, and these two would often "visit" in the feed room, which was a favourite playground of the bright-haired boy.

It is always funny if one can inspire terror without actual danger to the victim. Mason and Hall taught Jim to throw stones at sparrows, cats, and dogs, when his mother was not looking. He hardly ever hit them, and his hardest throw was harmless, but he learned to love the sport. A stray dog that persisted in stealing scraps which were by right the heritage of hens, was listed as an enemy, and together they showed Jim how to tie a tin can on the dog's tail in a manner that produced amazingly funny results and the final disappearance of the cur in a chorus of frantic yelps.

These laboratory experiments on animals developed under the able tutors, and Jim was instructed in the cat's war dance, an ingenious mode of inspiring puss to outdo her own matchless activity in a series of wild gyrations, by glueing to each foot a shoe of walnut shell, half filled with melted cobbler's wax to hold it on. Flattered by their attentions at first, the cat purred blandly as they fitted on the shoes. Jim's eyes were big and bright with tensest interest. The cat was turned loose in the grain room. To hear her own soft pads drop on the floor, each with a sharp, hard crack, must have been a curious, jarring experience. To find at every step a novel sense of being locked in, must have conjured up deep apprehensions in her soul. And when she fled, and sought to scale the partition, to find that her claws were gone—that she was now a thing with hoofs—must have been a horrid nightmare. Fear entered into her soul, took full control; then followed the wild erratic circling around the room, with various ridiculous attempts to run up the walls, which were so insanely silly that little James shrieked for joy, and joining in with the broom, urged the cat to still more amazing evidences of muscular activity not excelled by any other creature.

It was rare sport with just a sense of sin to give it tang, for he had been forbidden to torment the cat, and Jim saw nothing but the funny side; he was only seven.

It was a week later that they tried the walnut trick again, and Jim was eager to see the "circus." But the cat remembered; she drove her teeth deep into Hall's hand and fought with a feline fury that is always terrifying. Jim was gazing in big-eyed silence, when Hall, enraged, thrust the cat into the leg of a boot and growled, "I'll fix yer biting," and held her teeth to the grindstone till the body in the boot was limp.

At the first screech of the cat, Jim's whole attitude had changed. Amusement and wild-eyed wonder had given way to a shocking realization of the wicked cruelty. He sprang at Hall and struck him with all the best vigour of his baby fists. "Let my kitty go, you!" and he kicked the hostler in the shins until he himself was driven away. He fled indoors to his mother, flung himself into her arms and sobbed in newly awakened horror. To his dying day he never forgot that cry of pain. He had been in the way of cruel training with these men, but the climax woke him up. It was said that he never after was cruel to any creature, but this is sure—that he never after cared to be with cats of any sort.

This was the end of Hall, so far as his life had bearing on that of James Hartigan Second; for Kitty dismissed him promptly as soon as she heard the story of his brutality.

Of all the specimens of fine, physical manhood who owned allegiance to Downey's Hotel, Fightin' Bill Kenna was the outstanding figure. He was not so big as Mulcahy, or such a wrestler as Dougherty, or as skilled a boxer as McGraw; he knew little of the singlestick and nothing of knife- or gun-play; and yet his combination of strength, endurance and bullet-headed pluck made him by general voice "the best man in Links."

Bill's temper was fiery; he loved a fight. He never was worsted, the nearest thing to it being a draw between himself and Terry Barr. After that Terry went to the States and became a professional pugilist of note. Bill's social record was not without blemish. He was known to have appropriated a rope, to the far end of which was attached another man's horse. He certainly had been in jail once and should have been there a dozen times, for worse crimes than fighting. And yet Bill was firmly established as Bible bearer in the annual Orangemen's parade and would have smashed the face of any man who tried to rob him of his holy office.

Kenna was supposed to be a farmer, but he loved neither crops nor land. The dream of his exuberant life was to be a horse breeder, for which profession he had neither the capital nor the brains. His social and convivial instincts ever haled him townward, and a well-worn chair in Downey's bar-room was by prescriptive right the town seat of William Kenna, Esq., of the Township of Opulenta. Bill had three other good qualities besides his mighty fists. He was true to his friends, he was kind to the poor and he had great respect for his "wurd as a mahn." If he gave his "wurd as a mahn" to do thus and so, he ever made a strenuous effort to keep it.

Bill was madly in love with Kitty Hartigan. She was not unmoved by the huge manliness of the warlike William, but she had too much sense to overlook his failings, and she held him off as she did a dozen more—her devoted lovers all—who hung around ever hoping for special favour. But though Kitty would not marry him, she smiled on Kenna indulgently and thus it was that this man of brawn had far too much to say in shaping the life of little Jim Hartigan. High wisdom or deep sagacity was scarcely to be named among Kenna's attributes, and yet instinctively he noted that the surest way to the widow's heart was through her boy. This explained the beginning of their friendship, but other things soon entered in. Kenna, with all his faults, was a respecter of women, and—they commonly go together—a clumsy, awkward, blundering lover of children. Little Jim was bright enough to interest any one; and, with the certain instinct of a child, he drifted toward the man whose heart was open to him. Many a day, as Kenna split some blocks of wood that were over big and knotty for the official axeman, Jim would come to watch and marvel at the mighty blows. His comments told of the imaginative power born in his Celtic blood:

"Bill, let's play you are the Red Dermid smiting the bullhide bearing Lachlin," he would shout, and at once the brightness of his mental picture and his familiarity with the nursery tales of Erin that were current even in the woods created a wonder-world about him. Then his Ulster mind would speak. He would laugh a little shamefaced chuckle at himself and say:

"It's only Big Bill Kenna splitting wood."

Bill was one of the few men who talked to Jim about his father; and, with singular delicacy, he ever avoided mentioning the nauseating fact that the father was a papist. No one who has not lived in the time and place of these feuds can understand the unspeakable abomination implied by that word; it was the barrier that kept his other friends from mention of the dead man's name; and yet, Bill spoke with kindly reverence of him as, "a broth of a bhoy, a good mahn, afraid of no wan, and as straight as a string."

Among the occasional visitors at the stable yard was young Tom Ford, whose father owned the mill and half the town. Like his father, Tom was a masterful person, hungry for power and ready to rule by force. On the occasion of his first visit he had quarrelled with Jim, and being older and stronger, had won their boyish fight. It was in the hour of his humiliation that Kenna had taken Jim on his knee and said:

"Now Jim, I'm the lepricaun that can tache you magic to lick that fellow aisy, if ye'll do what I tell you." And at the word "lepricaun," the Celt in Jim rose mightier than the fighting, bullet-headed Saxon. His eager word and look were enough.

"Now, listen, bhoy. I'll put the boxing gloves on you every day, an' I'll put up a sack of oats, an' we'll call it Tom Ford; an' ye must hit that sack wi' yer fist every day wan hundred times, twenty-five on the top side and siventy-five on the bottom side for the undercut is worth more than the uppercut anny day; an' when ye've done that, ye're making magic, and at the end of the moon ye'll be able to lick Tom Ford."

Jim began with all his ten-year-old vigour to make the necessary magic, and had received Bill's unqualified approval until one day he appeared chewing something given him by one of the men as a joke. Jim paused before Bill and spat out a brown fluid.

"Fwhat are ye doing?" said Bill; then to his disgust, he found that Jim, inspired probably by his own example, was chewing tobacco.

"Spit it out, ye little divil, an' never agin do that. If ye do that three times before ye're twenty-one, ye'll make a spell that will break you, an' ye'll never lick Tom Ford."

Thus, with no high motive, Kenna was in many ways, the guardian of the child. Coarse, brutish, and fierce among men, he was ever good to the boy and respectful to his mother; and he rounded out his teaching by the doctrine: "If ye give yer word as a mahn, ye must not let all hell prevent ye holding to it." And he whispered in a dreadful tone that sent a chill through the youngster's blood: "It'll bring the bone-rot on ye if ye fail; it always does."

It is unfortunate that we cannot number the town school principal as a large maker of Jim's mind. Jim went to school and the teacher did the best he could. He learned to read, to write and to figure, but books irked him and held no lure. His joy was in the stable yard and the barn where dwelt those men of muscle and of animal mind; where the boxing gloves were in nightly use, the horses in daily sight, and the world of sport in ring or on turf was the only world worth any man's devotion.

There were a dozen other persons who had influence in the shaping of the life and mind of Little Jim Hartigan; but there was one that overpowered, that far outweighed, that almost negatived the rest; that was his mother. She could scarcely read, and all the reading she ever tried to do was in her Bible. Filled with the vision of what she wished her boy to be—a minister of Christ—Kitty sent him to the public school, but the colour of his mind was given at home. She told him the stories of the Man of Galilee, and on Sundays, hand in hand, they went to the Presbyterian Church, to listen to tedious details that illustrated the practical impossibility of any one really winning out in the fight with sin.

She sang the nursery songs of the old land and told the tales of magic that made his eyes stare wide with loving, childish wonder. She told him what a brave, kind man his father had been, and ever came back to the world's great Messenger of Love. Not openly, but a thousand times—in a thousand deeply felt, deeply meant, unspoken ways—she made him know that the noblest calling man might ever claim was this, to be a herald of the Kingdom. Alone, on her knees, she would pray that her boy might be elected to that great estate and that she might live to see him going forth a messenger of the Prince of Peace.

Kitty was alive to the danger of the inherited taste for drink in her son. The stern, uncompromising Presbyterian minister of the town, in whose church the widow had a pew, was temperate, but not an abstainer; in fact, it was his custom to close the day with a short prayer and a tall glass of whiskey and water. While, with his advice, she had entirely buried her doctrinal scruples on the selling of drink to the moderate, her mother-heart was not so easily put to sleep. Her boy belonged to the house side of the hotel. He was not supposed to enter the saloon; and when, one day, she found an unscrupulous barkeeper actually amusing himself by giving the child a taste of the liquid fire, she acted with her usual promptitude and vigour. The man was given just enough time to get his hat and coat, and the boy was absolutely forbidden the left wing of the house. Later, in the little room where he was born, she told Jim sadly and gently what it would mean, what suffering the drinking habit had brought upon herself, and thus, for the first time, he learned that this had been the cause of his father's death. The boy was deeply moved and voluntarily offered to pledge himself never to touch a drop again so long as he lived. But his mother wisely said:

"No, Jim; don't say it that way. Leaning backward will not make you safer from a fall; only promise me you'll never touch it till you are eighteen; then I know you will be safe."

And he promised her that he never would; he gave his word—no more; for already the rough and vigorous teaching of Bill Kenna had gripped him in some sort. He felt that there was no more binding seal; that any more was more than man should give.

When Jim was twelve he was very tall and strong for his age, and almost too beautiful for a boy. His mother, of course, was idolatrous in her love. His ready tongue, his gift of reciting funny or heroic verse, and his happy moods had made him a general favourite, the king of the stable yard. Abetted, inspired and trained by Kenna, he figured in many a boyish fight, and usually won so that he was not a little pleased with himself in almost every way. Had he not carried out his promise of two years before and thrashed the mayor's son, who was a year older than himself, and thereby taught a lesson to that stuck-up, purse-proud youngster? Could he not ride with any man? Yes, and one might add, match tongues with any woman. For his native glibness was doubly helped by the vast, unprintable vocabularies of his chosen world, as well as by choice phrases from heroic verse that were a more exact reflex of his mind.

Then, on a day, came Whiskey Mason drifting into Links once more. He was making an ever scantier living out of his wretched calling, and had sunk as low as he could sink. But he had learned a dozen clever tricks to make new victims.

At exactly eleven o'clock, p.m., the bar-room had been closed, as was by law required. At exactly eleven five, p.m. a traveller, sick and weak, supported by a friend, came slowly along the dusty road to the door, and, sinking down in agony of cramps, protested he could go no farther and begged for a little brandy, as his friend knocked on the door, imploring kindly aid for the love of heaven. The barkeeper was obdurate, but the man was in such a desperate plight that the Widow Hartigan was summoned. Ever ready at the call of trouble her kindly heart responded. The sick man revived with a little brandy; his friend, too, seemed in need of similar help and, uttering voluble expressions of gratitude, the travellers went on to lodgings on the other side of the town, carrying with them a flask in which was enough of the medicine to meet a new attack if one should come before they reached their destination.

At exactly eleven ten, p.m., these two helpless, harmless strangers received the flask from Widow Hartigan. At exactly eight a.m., the next day, at the opening of the Magistrate's office, they laid their information before him, that the Widow Hartigan was selling liquor out of hours. Here was the witness and here was the flask. They had not paid for this, they admitted, but said it had been "charged." All the town was in a talk. The papers were served, and on the following day, in court, before Tom Ford, the Mayor, the charge was made and sworn to by Mason, who received, and Hall, who witnessed and also received, the unlawful drink.

It was so evidently a trumped-up case that some judges would have dismissed it. But the Mayor was human; this woman had flouted his wife; her boy had licked his boy. The fine might be anything from one hundred up to one thousand dollars. The Mayor was magnanimous; he imposed the minimum fine. So the widow was mulcted a hundred dollars for playing the rôle of good Samaritan. Mason and Hall got fifty dollars to divide, and five minutes later were speeding out of town. They left no address. In this precautionary mood their instincts were right, though later events proved them to be without avail.

Just one hour after the disappearance of Mason, Kenna came to town and heard how the Widow's open-hearted kindness had led her into a snare. His first question was: "Where is he?" No one knew, but every one agreed that he had gone in a hurry. Now it is well known that experienced men seeking to elude discovery make either for the absolute wilderness or else the nearest big city. There is no hiding place between. Kenna did not consult Kitty. He rode, as fast as horse could bear his robust bulk to Petersburg where Mason had in some sort his headquarters.

It was noon the next day before Bill found him, sitting in the far end of the hardware shop. Mason never sat in the saloons, for the barkeepers would not have him there. He did not loom large, for he always tried to be as inconspicuous as possible, and his glance was shifty.

Bill nodded to the iron dealer and passed back to the stove end of the store. Yes, there sat Mason. They recognized each other. The whiskey sneak rose in trepidation. But William said calmly, "Sit down."

"Well," he continued with a laugh, "I hear you got ahead of the Widdy."

"Yeh."

"Well, she can afford it," said Bill. "She's getting rich."

Mason breathed more freely.

"I should think ye'd carry a revolver in such a business," said William, inquiringly.

"Bet I do," said Mason.

"Let's have a look at it," said Kenna. Mason hesitated.

"Ye better let me see it, or——" There was a note of threat for the first time. Mason drew his revolver, somewhat bewildered. Before the informer knew what move was best, Kenna reached out and took the weapon.

"I hear ye got twenty-five dollars from the Widdy."

"Yeh." And Mason began to move nervously under the cold glitter in Kenna's eyes.

"I want ye to donate that to the orphan asylum. Here, Jack!" Kenna called to the clerk, "Write on a big envelope 'Donation for the orphan asylum. Conscience money.'"

"What does it say?" inquired Bill, for he could not read. The clerk held out the envelope and read the inscription.

"All right," said Bill, "now, Mason, jest so I won't lose patience with you and act rough like, hand over that twenty-five."

"I ain't got it, I tell you. It's all gone."

"Turn out your pockets, or I will."

The whiskey sneak unwillingly turned out his pockets. He had fifteen dollars and odd.

"Put it in that there envelope," said Bill, with growing ferocity. "Now gum it up. Here, Jack, will ye kindly drop this in the contribution box for the orphans while we watch you?" The clerk entered into the humour of it all. He ran across the street to the gate of the orphan asylum and dropped the envelope into the box. Mason tried to escape but Bill's mighty hand was laid on his collar. And now the storm of animal rage pent up in him for so long broke forth. He used no weapon but his fists, and when the doctor came, he thought the whiskey man was dead. But they brought him round, and in the hospital he lingered long.

It was clearly a case of grave assault; the magistrate was ready to issue a warrant for Kenna's arrest. But such was Bill's reputation that they could get no constable to serve it. Meanwhile, Mason hung between life and death. He did not die. Within six weeks, he was able to sit up and take a feeble interest in things about him, while Bill at Links pursued his normal life.

Gossip about the affair had almost died when the Mayor at Petersburg received a document that made him start. The Attorney General of the Province wrote: "Why have you not arrested the man who committed that assault? Why has no effort been made to administer justice?"

The Mayor was an independent business man, seeking no political favours, and he sent a very curt reply. "You had better come and arrest him yourself, if you are so set on it."

That was why two broad, square men, with steadfast eyes, came one day into Links. They sought out Bill Kenna and found him in the bar-room, lifting the billiard table with one hand, as another man slipped wedges under it to correct the level. Little Jim, though he had no business there at all, stood on the table itself and gave an abundance of orders.

"Are you William Kenna?" said the first of the strangers.

"I am that," said he.

"Then I arrest you in the Queen's name"; and the officer held up a paper while the other produced a pair of handcuffs.

"Oi'd like to see ye put them on me." And the flood of fight in him surged up.

He was covered by two big revolvers now, which argument had no whit of power to modify his mood; but another factor had. The Widow who had entered in search of Jim and knew the tragedy that hung by a hair, sped to his side: "Now, Bill, don't ye do it! I forbid ye to do it!"

"If they try to put them on me, I'll kill or be killed. If they jist act dacent, I'll go quiet."

"Will ye give yer word, Bill?"

"I will, Kitty; I'll give me word as a mahn. I'll go peaceable if they don't try to handcuff me."

"There," said Kitty to the officers. "He's give his word; and if you're wise, ye'll take him at that."

"All right," said the chief constable, and between them William moved to the door.

"Say, Bill, ye ain't going to be took?" piped little Jim. He had watched the scene dumbfounded from his place on the table. This was too much.

"Yes," said Bill, "I've give me word as a mahn," and he marched away, while the Widow fled sobbing to her room.

That was the end of Kenna, so far as Jim was concerned. And, somehow, that last sentence, "I've give me word as a mahn," kept ringing in Jim's ears; it helped to offset the brutalizing effect of many other episodes—that Fighting Bill should scoff at bonds and force, but be bound and helpless by the little sound that issued from his own lips.

Bill's after life was brief. He was condemned to a year in jail for deadly assault and served the term and came again to Petersburg. There in a bar-room he encountered Hall, the pal of Whisky Mason. A savage word from Bill provoked the sneer, "You jail bird." Kenna sprang to avenge the insult. Hall escaped behind the bar. Bill still pursued. Then Hall drew a pistol and shot him dead; and, as the Courts held later, shot justly, for a man may defend his life.

It was a large funeral that buried Bill, and it was openly and widely said that nine out of ten were there merely to make sure that he was dead and buried. The Widow Hartigan was chief mourner in the first carriage. She and Jim led the line, and when he was laid away, she had a stone erected with the words, "A true friend and a man without fear." So passed Kenna; but Jim bore the traces of his influence long and deeply—yes, all his life. Masterful, physical, prone to fight and to consider might as right, yet Jim's judgment of him was ever tempered by the one thought, the binding force of his "wurd as a mahn."

The Widow never forgot that her tenure of the hotel might end at any time; and, thinking ever of Jim and his future, she saved what she could from the weekly proceeds. She was a good manager, and each month saw something added to her bank account. When it had grown to a considerable size her friends advised her to invest it. There were Government bonds paying five per cent., local banks paying six and seven, and, last of all, the Consolidated Trading Stores paying eight and sometimes more—an enterprise of which Tom Ford was head.

The high interest was tempting, and pride was not without some power. Kitty was pleased to think that now she could go to the pompous Mayor as a capitalist. So, creating with an inward sense of triumph the impression of huge deposits elsewhere, she announced that she would take a small block of stock in the C. T. S. as a nest-egg for her boy. Thus the accumulations of ten years went into the company of which the Mayor was head and guide. For a time, the interest was duly paid each half year. Then came a crash. After the reorganization the Mayor continued in his big brick house and his wife still wore her diamonds; but the widow's hard-earned savings were gone. Kitty was stunned but game; falling back on the strength that was inside, she bravely determined to begin all over and build on a rock of safety. But fortune had another blow in store for Jim. And it fell within a month, just as he turned thirteen.

It was the end of the Canadian winter. Fierce frost and sudden thaw were alternated as the north wind and the south struggled for the woods, and the heat of work in the warm sun left many ill prepared for the onset of bitter cold at dusk. Bustling everywhere, seeing that pigs were fed, pies made, and clothes mended; now in the hot kitchen, a moment later in the stable yard to manage some new situation; the Widow fell a victim to pneumonia much as John Downey had done.

For three days she lay in fever and pain. Jim was scarcely allowed to see her. They did not understand pneumonia in those days, and as it was the general belief that all diseases were "catching," the boy was kept away. The doctor was doing his best with old-fashioned remedies, blisters, mustard baths, hot herb teas and fomentations. He told her she would soon be well, but Kitty knew better. On the third day, she asked in a whisper for Jim, but told them first to wash his face and hands with salt water. So the long-legged, bright-eyed boy came and sat by his mother's bed and held her hot hands. As he gazed on her over-bright eyes, she said softly:

"My darling, you'll soon be alone, without friend or kith or kin. This place will no longer be your home. God only knows where you'll go. But He will take care of you as He took care of me."

For the first time Jim realized the meaning of the scene—his mother was dying. She quieted his sobs with a touch of her hand and began again, slowly and painfully:

"I tried to leave you well fixed, but it was not to be. The hotel will go to another. This is all I have for you."

She drew a little cedar box from under the covers, and opening it, showed him her Bible, the daguerreotype of his father and a later photograph of herself.

"Jim, promise me again that you will never touch tobacco or liquor till you are eighteen."

"Oh, mother, mother!" he wept. "I'll do anything you say. I'll promise. I give you my word I never will touch them."

She rested in silence, her hand was on his head. When her strength in a little measure came again, she said in a low tone:

"My wish was to see you educated, a minister for Christ. I hope it may yet be so."

She was still a long time; then, gently patting his head, she said to those around:

"Take him away. Wash him with salt and water."

Thus it came about that the hotel which had been Jim's only home and which he thought belonged to his mother, passed into the hands of John Downey, Jr., nephew of the original owner. It was Mrs. John Downey who offered the first ray of comfort in Jim's very bleak world. When she saw the tall handsome boy she put her arms around him and said:

"Never mind, Jim, don't go away. This will always be home for you."

So the lad found a new home in the old house, but under greatly changed conditions. The new mistress had notions of her own as to the amount of education necessary and the measure of service to be returned for one's keep. Jim was able to read, write, and cipher; this much was ample in the opinion of Mrs. Downey, and Jim's school days ended. The understanding that he must make himself useful quickly resulted in his transference to the stable. A garret in the barn was furnished with a bed for him, and Jim's life was soon down to its lowest level. He had his friends, for he was full of fun and good to look upon: but they were not of the helpful kind, being recruited chiefly from the hostlers, the pugilists, and the horsemen. He had time for amusements, too; but they were nearly always of the boxing glove and the saddle. Books had little charm for him, though he still found pleasure in reciting the heroic ballads of Lachlin, the Raid of Dermid, the Battle of the Boyne, and in singing "My Pretty, Pretty Maid," or woodmen's "Come all ye's." His voice was unusually good, except at the breaking time; and any one who knew the part the minstrel played in Viking days would have thought the bygone times come back to see him among the roystering crowd at Downey's.

The next three years that passed were useless except for this, they gifted Jim with a tall and stalwart form and shoulders like a grown man. But they added little to the good things he had gathered from his mother and from Fightin' Bill. At sixteen he was six feet high, slim and boyish yet, but sketched for a frame of power. All this time his meagre keep and his shabby clothes were his only pay. But Jim had often talked things over with his friends and they pointed out that he was now doing man's work and getting less than boy's pay. The scene that followed his application for regular wages was a very unpleasant one; and John Downey made the curious mistake of trying to throw young Jimmy out. The boy never lost his temper for a moment but laughingly laid his two strong hands on the landlord's fat little shoulders and shook him till his collar popped and his eyes turned red. Then Jim grinned and said:

"I told ye I wasn't a kid anny more."

It was the landlady's good sense that made a truce, and after a brief, stormy time the long-legged boy was reinstated at wages in the yard.

At seventeen Jim was mentioned among the men as a likely "bhoy." Women in the street would turn to look in admiration at his square shoulders, lithe swing, and handsome head. But the life he led was flat, or worse than flat. The best that can be said of it is that in all this sordid round of bar and barn he learned nothing that in any sort had power to harm his rare physique. His language at times was the worst of its lurid kind. His associates were coarse and drunken. Yet Jim lived with them in all their ways and neither chewed, smoked, nor drank. How or why, none understood. He said simply that he "didn't feel like he wanted to." With the liquor it was a different matter. Here it was a question of principle and his word to his mother helped him where by nature he was weak. So he grew up, hedged about with a dignity that was in some sense a foreshadowing of his destiny. But there was much dross to be burned away and the two great passions that stood between Jim Hartigan and full spiritual manhood had their roots in these early years at Downey's. Later he matched his strength against theirs and with that struggle, in which no quarter was asked or given, these pages are ultimately concerned.

Many a man has been ruined by a high, unbroken level of success. Intellectually it makes for despotism and a conviction of infallibility. In the world of muscle, it creates a bully.

Young Jim was far from losing his interest in the ring, and he was growing so big and strong that there were few in town who cared to put on the gloves with him. All that Bill Kenna had taught him, and more, was stored as valued learning. Kenna used to say, in his Irish vein: "There is twelve rules for to conduct yourself right in a shindy; the first is, get your blow in first; and, if ye live up to this, ye needn't worry about the other iliven rules." Jim accepted this as fundamental truth and thereby became the aggressor in nearly every brawl.

His boiling, boisterous, animal nature grew with his body and he revelled in the things of brawn. He responded joyfully when he was called on to eject some rowdy from the bar-room, and begetting confidence with each new victory, he began to have a vast opinion of himself. About this time a powerful rival of Downey's, known as the Dummer House, claimed attention at the other end of town. One was located to catch the inbound from the west; the other, those from the east. And when the owners were not at war, they kept at best an armed neutrality.

John Downey had delivered himself of some unhallowed hopes concerning the rival house, and Jim, as he passed the opposition Inn on a certain evening, had the picturesque devastations vividly in mind. It so happened that a masting team of oxen was standing patiently outside awaiting the driver who was refreshing himself at the bar. A masting team consists of six to twelve strong, selected oxen, yoked two and two to a mighty chain with which they can drag forth the largest pines that are saved for masts. Jim's too-agile mind noted the several components of a new and delightful exploit: a crowd of noisy teamsters in a log house bar-room, a team of twelve huge, well-trained oxen on a chain, the long, loose end of which lay near him on the ground. It was the work of a minute to hook the chain around a projecting log of the house. A moment more and he had the oxen on the go. Beginning with the foremost pair, he rushed down the line, and the great, heaving, hulking shoulders, two and two, bent and heaved their bulk against the strain. The chain had scarcely time to tighten; no house could stand against that power. The huge pine log was switched out at one end as a man might jerk a corn cob from its crib. The other end, still wedged in its place, held for a moment; but the oxen moved slowly on like a landslide. The log was wrenched entirely away and the upper part of the building dropped with a sullen "chock" to rest a little lower. There was a wild uproar inside, a shouting of men, a clatter of glass, and out rushed the flushed-faced rabble, astonished, frightened, furious to see the twelve great oxen solemnly marching down the street, trailing the missing log, the fragment of their house, while beside them, running, laughing, hooting, was a long-legged boy.

Jim's intention had been to clear out, but the trick proved so screamingly funny that he stood for a minute to enjoy the scene. Shelves had fallen and glasses had broken, but no person had been hurt. There was a moment's uncertainty; then with an angry shout the enraged patrons of the Dummer House swept forward. Jim discreetly fled. In the centre of the town friends appeared and in the street he turned to face his pursuers. Jim had already proved himself one of "the best men in Links" and it was with a new burst of hilarity that he wheeled about among his backers to give them "all they wanted." Instead of the expected general onslaught, a method new to Jim was adopted. The teamsters of the Dummer House held back and from their ranks there issued a square-jawed, bow-legged man, whose eye was cold, whose step was long and quick. With the utmost deliberation he measured Jim with his eye. Then he growled:

"Come on, ye ill-born pup. Now ye'll get what ye desarve."

The sporting instinct was strong in the crowd and the two were left alone to fight it out. It took very little time. Jim had made a mistake—a serious one. This was no simple teamster, guileless of training, who faced him, but a man whose life was in the outer circle of the prize ring. The thrashing was complete, and effective for several weeks. Jim was carried home and ever after he bore upon his chin a scar that was the record of the final knockout from the teamster's iron fist.

The catastrophe had several important compensations. The owner of the Dummer House decided that the boy was punished enough, and took no legal proceeding against him. On his part, Jim began to think much more seriously before giving reckless rein to his sense of humour. On the whole, his respect for the rights of others was decidedly increased. His self-esteem shrunk to more normal proportions and if he thought of the incident at all it was to wish very earnestly that some day, somewhere, he might meet the teamster again on more even terms.

Unfortunately these salutory results were negatived some six months later by an event that took place in Downey's bar. It was Jim's birthday; he was eighteen and he announced it with pride.

"And here's where ye join us," said several.

"No, I don't care about it," said Jim.

"Ye ain't promise bound now, are ye?"

"No," replied Jim, "but——"

"Make him a sweet one with syrup and just a spoonful of the crather to take the curse off."

Refusing, protesting, half ashamed of his hesitation, Jim downed at a gulp a fruity concoction, much to the delight of the assemblage. It was not so bad as he had expected it to be and the crowd roared at the expression on his face.

"Ye're a man for yourself now, lad," said a woodsman clapping him on the shoulder. "Come boys, another round to Hartigan's health."

It could not be said of Jim that he was normal in anything. In a rare and multiplied degree he had inherited the full muscling and robust heart of his folk in both lines of forbears. It was a great inheritance, but it carried its own penalty. The big animal physique holds a craving for strong drink. Physical strength and buoyancy are bound up with the love of bacchanalian riot. Jim had given his word to abstain from liquor until he was of age; he had kept it scrupulously. Now he had tasted of it the pendulum swung full to the other side. That was his nature. His world might be a high world or a low world; whichever sphere he moved in he practised no half-way measures.

From that eighteenth birthday Jim Hartigan waged ceaseless warfare within himself. During the early days he was an easy victim. Then came a shock that changed the whole aspect of his life, and later one stood beside him who taught him how to fight. But until those events took place, the town of Links knew him for what he was, a reckless, dare-devil youth, without viciousness or malice, but ripe for any extravagance or adventure. His pranks were always begun in fun though it was inevitable that they should lead to serious consequences. It was admitted by his severest critics that he had never done a cruel or a cowardly thing, yet the constant escapades and drinking bouts in which he was ever the leader earned him the name of Wild Jim Hartigan.

After each fresh exploit his abject remorse was pitiful. And so, little by little, a great nature was purged; his spirit was humbled by successive and crushing defeats. At first the animal rebound was sufficient to set him on his feet unashamed. But during the fourth year after his coming of age, an unrest, a sickness of soul took possession of Jim and no wildness sufficed to lift this gloom. And it was in frantic rebellion against this depression that he entered upon his memorable visit to the Methodist revival.

There was much excitement in Methodist circles that autumn. A preacher of power had come from the east. The church was filled to overflowing on Sunday, and a prayer meeting of equal interest was promised for Wednesday night.

The people came from miles around and there were no vacant seats. Even the aisles were filled with chairs when the Rev. Obadiah Champ rose and bawled aloud in rolling paragraphs about "Hopeless, helpless, hell-damned sinners all. Come, come to-day. Come now and be saved." A wave of religious hysteria spread over the packed-in human beings. A wave that to those untouched was grotesque and incomprehensible.

"Sure, they ain't right waked up yet," said one of Jim's half-dozen unregenerate friends who had come to sit with him on the fence outside, and scoff at the worshippers. Jim was silent, but a devil of wild deeds stirred irritatingly within him. He looked about him for some supreme inspiration—some master stroke. The crowd was all in the church now, and the doors were closed tight. But muffled sounds of shouting, of murmurings, of halleluiahs were heard.

"They're goin' it pretty good now, Jim," said another. "But I think you could arouse 'em," he added, with a grin.

Standing by the church was a tall elm tree; near by was a woodshed with axe, saw, and wood pile. Jim's eye measured the distance from trunk to roof and then, acting on a wild impulse, with visions of folk in terror for their bodies when they professed concern for nothing but their souls, he got the axe, and amid the suppressed giggles and guffaws of his chums, commenced to fell the tree. In twenty minutes the great trunk tottered, crackled, and swung down fair on the roof of the crowded building.

The congregation had reached a degree of great mental ferment with the revival, and a long, loud murmuring of prayers and groans, with the voice of the exhorter, harsh and ringing, filled the edifice, when with a crash overhead the great arms of the tree met the roof. At first, it seemed like a heavenly response to the emotion of the congregation, but the crackling of small timber, the showering down of broken glass and plaster gave evidence of a very earthly interposition.

Then there was a moment of silence, then another crack from the roof, and the whole congregation arose and rushed for the door. All in vain the exhorter tried to hold them back. He shrieked even scriptural texts to prove they should stay to see the glory of the Lord. Another flake of plaster fell, on the pulpit this time; then he himself turned and fled through the vestry and out by the back way.

Jim's following had deserted him, but he himself was there to see the fun; and when the congregation rushed into the moonlight it was like a wasp's nest poked with a stick, or a wheat shock full of mice turned over with a fork. The crowd soon understood the situation and men gathered around the sinner. There was menace in every pose and speech. They would have him up to court; they would thrash him now. But the joyful way in which Jim accepted the last suggestion and offered to meet any or all "this holy minute" had a marked effect on the programme, especially as there were present those who knew him.

Then the exhorter said: