The Project Gutenberg EBook of Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Author: Various Release Date: August 30, 2009 [EBook #29848] Last updated: March 20, 2011 Last updated: May 26, 2013 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASTOUNDING STORIES *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, and WESTERN ADVENTURES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

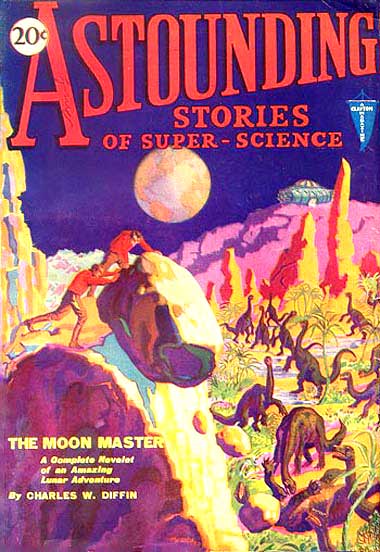

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSOLOWSKI | ||

| Painted in Water-colors from a Scene in "The Moon Master." | |||

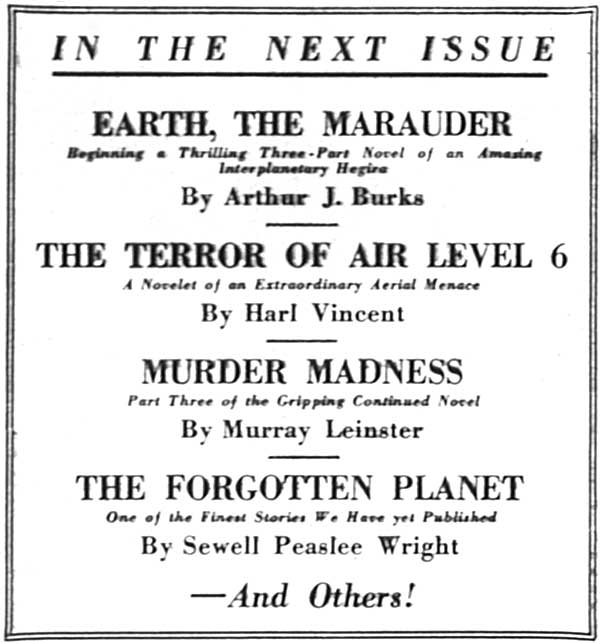

| OUT OF THE DREADFUL DEPTHS | C. D. WILLARD | 293 | |

| Robert Thorpe Seeks Out the Nameless Horror That Is Sucking All Human Life Out of Ships in the South Pacific. | |||

| MURDER MADNESS | MURRAY LEINSTER | 310 | |

| Bell, of the Secret "Trade," Strikes into the South American Jungle to Find the Hidden Stronghold of the Master—the Unknown Monster Whose Diabolical Poison Swiftly and Surely Is Enslaving the Whole Continent. (Part Two of a Continued Novel.) | |||

| THE CAVERN WORLD | JAMES P. OLSEN | 340 | |

| A Great Oil Field Had Gone Dry—and Asher, Trapped Far under the Earth Among the Revolting Petrolia, Learns Why. | |||

| BRIGANDS OF THE MOON | RAY CUMMINGS | 352 | |

| The Besieged Earth-men Wage Grim, Ultra-scientific War with Martian Bandits in a Last Great Struggle for Their Radium-ore—and Their Lives. (Conclusion.) | |||

| GIANTS OF THE RAY | TOM CURRY | 368 | |

| Madly the Three Raced for their Lives up the Shaft of the Radium Mine, for Behind Them Poured a Stream of Hideous Monsters—Giants of the Ray! | |||

| THE MOON MASTER | CHARLES W. DIFFIN | 384 | |

| Through Infinite Deeps of Space Jerry Foster Hurtles to the Moon—Only to be Trapped by a Barbaric Race and Offered as a Living Sacrifice to Oong, their Loathsome, Hypnotic God. (A Complete Novel.) | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 421 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Application for entry as second-class mail pending at the Post Office at New York, under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

"Help—help—the eyes—the eyes!"

"Help—help—the eyes—the eyes!"

obert Thorpe reached languidly for a cigarette and, with lazy fingers, extracted a lighter from his pocket.

"Be a sport," he repeated to the gray haired man across the table. "Be a sport, Admiral, and send me across on a destroyer. Never been on a destroyer except in port. It ... would be a new experience ... enjoy it a lot...."

In the palm-shaded veranda of this club-house in Manila, Admiral Struthers, U. S. N., regarded with undisguised disfavor the young man in the wicker chair. He looked at the deep chest and the broad shoulders which even a loose white coat could not conceal, at the short, wavy brown hair and the slow, friendly smile on the face below.

A likable chap, this Thorpe, but lazy—just an idler—he had concluded. Been playing around Manila for the last two months—resting up, he had said. And from what? the Admiral had questioned disdainfully. Admiral Struthers did not like indolent young men, but it would have saved him money if he had really got an answer to his question and had learned just why and how Robert Thorpe had earned a vacation.

"You on a destroyer!" he said, and the lips beneath the close-cut gray mustache twisted into a smile. "That[294] would be too rough an experience for you, I am afraid, Thorpe. Destroyers pitch about quite a bit, you know."

He included in his smile the destroyer captain and the young lady who completed their party. The young lady had a charming and saucy smile and knew it; she used it in reply to the Admiral's remark.

"I have asked Mr. Thorpe to go on the Adelaide," she said. "We shall be leaving in another month—but Robert tells me he has other plans."

"Worse and worse," was the Admiral's comment. "Your father's yacht is not even as steady as a destroyer. Now I would suggest a nice comfortable liner...."

obert Thorpe did not miss the official glances of amusement, but his calm complacence was unruffled. "No," he said, "I don't just fancy liners. Fact is, I have been thinking of sailing across to the States alone."

The Admiral's smile increased to a short laugh. "I would make a bet you wouldn't get fifty miles from Manila harbor."

The younger man crushed his cigarette slowly into the tray. "How much of a bet?" he asked. "What will you bet that I don't sail alone from here to—where are you stationed?—San Diego?—from here to San Diego?"

"Humph!" was the snorted reply. "I would bet a thousand dollars on that and take your money for Miss Allaire's pet charity."

"Now that's an idea," said Thorpe. He reached for a check book in his inner pocket and began to write.

"In case I lose," he explained, "I might be hard to find, so I will just ask Miss Allaire to hold this check for me. You can do the same." He handed the check to the girl.

"Winner gets his thousand back, Ruth; loser's money goes to any little orphans you happen to fancy."

"You're not serious," protested the Admiral.

"Sure! The bank will take that check seriously, I promise you. And I saw just the sloop I want for the trip ... had my eye on her for the past month."

"But, Robert," began Ruth Allaire, "you don't mean to risk your life on a foolish bet?"

Thorpe reached over to pat tenderly the hand that held his check. "I'm glad if you care," he said, and there was an undertone of seriousness beneath his raillery, "but save your sympathy for the Admiral. The U. S. Navy can't bluff me." He rose more briskly from his chair.

"Thorpe...." said Admiral Struthers. He was thinking deeply, trying to recollect. "Robert Thorpe.... I have a book by someone of that name—travel and adventure and knocking about the world. Young man, are you the Robert Thorpe?"

"Why, yes, if you wish to put it that way," agreed the other. He waved lightly to the girl as he moved away.

"I must be running along," he said, "and get that boat. See you all in San Diego!"

he first rays of the sun touched with golden fingers the tops of the lazy swells of the Pacific. Here and there a wave broke to spray under the steady wind and became a shower of molten metal. And in the boat, whose sails caught now and then the touch of morning, Robert Thorpe stirred himself and rose sleepily to his feet.

Out of the snug cabin at this first hint of day, he looked first at the compass and checked his course, then made sure of the lashing about the helm. The steady trade-winds had borne him on through the night, and he nodded with satisfaction as he prepared to lower his lights. He was reaching for a line as the little craft hung for an instant on the top of a wave. And in that instant his eyes caught a marking of white on the dim waters ahead.

"Breakers!" he shouted aloud and leaped for the lashed wheel. He swung[295] off to leeward and eased a bit on the main-sheet, then lashed the wheel again to hold on the new course.

Again from a wave-crest he stared from under a sheltering hand. The breakers were there—the smooth swells were foaming—breaking in mid-ocean where his chart, he knew, showed water a mile deep. Beyond the white line was a three-master, her sails shivering in the breeze.

The big sailing ship swung off on a new tack as he watched. Was she dodging those breakers? he wondered. Then he stared in amazement through the growing light at the unbroken swells where the white line had been.

e rubbed his sleepy eyes with a savage hand and stared again. There were no breakers—the sea was an even expanse of heaving water.

"I could swear I saw them!" he told himself, but forgot this perplexing occurrence in the still more perplexing maneuvers of the sailing ship.

This steady wind—for smooth handling—was all that such a craft could ask, yet here was this old-timer of the sea with a full spread of canvas booming and cracking as the ship jibed. She rolled far over as he watched, recovered, and tore off on a long, sweeping circle.

The one man crew of the little sloop should have been preparing breakfast, as he had for many mornings past, but, instead he swung his little craft into the wind and watched for near an hour the erratic rushes and shivering haltings of the larger ship. But long before this time had passed Thorpe knew he was observing the aimless maneuvers of an unmanned vessel.

And he watched his chance for a closer inspection.

he three-master Minnie R., from the dingy painting of the stern, hung quivering in the wind when he boarded her. There was a broken log-line that swept down from the stern, and he caught this and made his own boat fast. Then, watching his chance, he drew close and went overboard, the line in his hand.

"Like a blooming native after cocoanuts," he told himself as he went up the side. But he made it and pulled himself over the rail as the ship drew off on another tack.

Thorpe looked quickly about the deserted deck. "Ahoy, there!" he shouted, but the straining of rope and spars was his only answer. Canvas was whipping to ribbons, sheets cracked their frayed ends like lashes as the booms swung wildly, but a few sails still held and caught the air.

He was on the after deck, and he leaped first for the wheel that was kicking and whirling with the swing of the rudder. A glance at the canvas that still drew, and he set her on a course with a few steadying pulls. There was rope lying about, and he lashed the wheel with a quick turn or two and watched the ship steady down to a smooth slicing of the waves from the west.

And only then did the man take time to quiet his panting breath and look about him in the unnatural quiet of this strangely deserted deck. He shouted again and walked to a companionway to repeat the hail. Only an echo, sounding hollowly from below, replied to break the vast silence.

t was puzzling—inconceivable. Thorpe looked about him to note the lifeboats snug and undisturbed in their places. No sign there of an abandonment of the boat, but abandoned she was, as the silence told only too plainly. And Thorpe, as he went below, had an uncanny feeling of the crew's presence—as if they had been there, walked where he walked, shouted and laughed a matter of a brief hour or two before.

The door of the captain's cabin was burst in, hanging drunkenly from one hinge. The log-book was open; there were papers on a rude desk. The bunk was empty where the blankets had been[296] thrown hurriedly aside. Thorpe could almost see the skipper of this mystery ship leaping frantically from his bed at some sudden call or commotion. A chair was smashed and broken, and the man who examined it curiously wiped from his hands a disgusting slime that was smeared stickily on the splintered fragments. There was a fetid stench within his nostrils, and he passed up further examination of this room.

Forward in the fo'c'sle he felt again irresistibly the recent presence of the crew. And again he found silence and emptiness and a disorder that told of a fear-stricken flight. The odor that sickened and nauseated the exploring man was everywhere. He was glad to gain the freedom of the wind-swept deck and rid his lungs of the vile breath within the vessel.

He stood silent and bewildered. There was not a living soul aboard the ship—no sign of life. He started suddenly. A moaning, whimpering cry came from forward on the deck!

Thorpe leaped across a disorder of tangled rope to race toward the bow. He stopped short at sight of a battered cage. Again the moaning came to him—there was something that still lived on board the ill-fated ship.

e drew closer to see a great, huddled, furry mass that crouched and cowered in a corner of the cage. A huge ape, Thorpe concluded, and it moaned and whimpered absurdly like a human in abject fear.

Had this been the terror that drove the men into the sea? Had this ape escaped and menaced the officers and crew? Thorpe dismissed the thought he well knew was absurd. The stout wood bars of the cage were broken. It had been partially crushed, and the chain that held it to the deck was extended to its full length.

"Too much for me," the man said slowly, aloud; "entirely too much for me! But I can't sail this old hooker alone; I'll have to get out and let her drift."

He removed completely one of the splintered bars from the broken cage. "I've got to leave you, old fellow," he told the cowering animal, "but I'll give you the run of the ship."

He went below once more and came quickly back with the log-book and papers from the captain's room. He tied these in a tight wrapping of oilcloth from the galley and hung them at his belt. He took the wheel again and brought the cumbersome craft slowly into the wind. The bare mast of his own sloop was bobbing alongside as he went down the line and swam over to her.

Fending off from the wallowing hulk, he cut the line, and his small craft slipped slowly astern as the big vessel fell off in the wind and drew lumberingly away on its unguided course.

She vanished into the clear-cut horizon before the watching man ceased his staring and pricked a point upon his chart that he estimated was his position.

And he watched vainly for some sign of life on the heaving waters as he set his sloop back on her easterly course.

t was a sun-tanned young man who walked with brisk strides into the office of Admiral Struthers. The gold-striped arm of the uniformed man was extended in quick greeting.

"Made it, did you?" he exclaimed. "Congratulations!"

"All O.K.," Thorpe agreed. "Ship and log are ready for your verification."

"Talk sense," said the officer. "Have any trouble or excitement? Or perhaps you are more interested in collecting a certain bet than you are in discussing the trip."

"Damn the bet!" said the young man fervently. "And that's just what I am here for—to talk about the trip. There were some little incidents that may interest you."

He painted for the Admiral in brief, terse sentences the picture of that day[297]break on the Pacific, the line of breakers, white in the vanishing night, the abandoned ship beyond, cracking her canvas to tatters in the freshening breeze. And he told of his boarding her and of what he had found.

"Where was this?" asked the officer, and Thorpe gave his position as he had checked it.

"I reported the derelict to a passing steamer that same day," he added, but the Admiral was calling for a chart. He spread it on the desk before him and placed the tip of a pencil in the center of an unbroken expanse.

"Breakers, you said?" he questioned. "Why, there are hundreds of fathoms here, Mr. Thorpe."

know it," Thorpe agreed, "but I saw them—a stretch of white water for an eighth of a mile. I know it's impossible, but true. But forget that item for a time, Admiral. Look at this." He opened a brief case and took out a log-book and some other papers.

"The log of the Minnie R.," he explained briefly. "Nothing in it but routine entries up to that morning and then nothing at all."

"Abandoned," mused the Admiral, "and they did not take to the boats. There have been other instances—never explained."

"See if this helps any," suggested Thorpe and handed the other two sheets of paper. "They were in the captain's cabin," he added.

Admiral Struthers glanced at them, then settled back in his chair.

"Dated September fourth," he said. "That would have been the day previous to the time you found her." The writing was plain, in a careful, well-formed hand. He cleared his throat and read aloud:

"Written by Jeremiah Wilkens of Salem, Mass., master of the Minnie R., bound from Shanghai to San Pedro. I have sailed the seas for forty years, and for the first time I am afraid. I hope I may destroy this paper when the lights of San Pedro are safe in sight, but I am writing here what it would shame me to set down in the ship's log, though I know there are stranger happenings on the face of the waters than man has ever seen—or has lived to tell.

ll this day I have been filled with fear. I have been watched—I have felt it as surely as if a devil out of hell stood beside me with his eyes fastened on mine. The men have felt it, too. They have been frightened at nothing and have tried to conceal it as I have done.—And the animals....

"A shark has followed us for days—it is gone to-day. The cats—we have three on board—have howled horribly and have hidden themselves in the cargo down below. The mate is bringing a big monkey to be sold in Los Angeles. An orang-outang, he calls it. It has been an ugly brute, shaking at the bars of its cage and showing its ugly teeth ever since we left port. But to-day it is crouched in a corner of its cage and will not stir even for food. The poor beast is in mortal terror.

"All this is more like the wandering talk of an old woman muttering in a corner by the fireside of witches and the like than it is like a truthful account set down by Jeremiah Wilkins. And now that I have written it I see there is nothing to tell. Nothing but the shameful account of my fear of some horror beyond my knowing. And now that it is written I am tempted to destroy—No, I will wait—"

"And now what is this?" Admiral Struthers interrupted his reading to ask. He turned the paper to read a coarse, slanting scrawl at the bottom of the page.

"The eyes—the eyes—they are everywhere above us—God help—" The writing trailed off in a straggling line.

he lips beneath the trim gray mustache drew themselves into a hard line. It was a moment before[298] Admiral Struthers raised his eyes to meet those of Robert Thorpe.

"You found this in the captain's cabin?" he asked.

"Yes."

"And the captain was—"

"Gone."

"Blood stains?"

"No, but the door had been burst off its hinges. There had been a struggle without a doubt."

The officer mused for a minute or two.

"Did they go aboard another vessel?" he pondered. "Abandon ship—open the sea-cocks—sink it for the insurance?" He was trying vainly to find some answer to the problem, some explanation that would not impose too great a strain upon his own reason.

"I have reported to the owners," said Thorpe. "The Minnie R. was not heavily insured."

The Admiral ruffled some papers on his desk to find a report.

"There has been another," he told Thorpe. "A tramp freighter is listed as missing. She was last reported due east of the position you give. She was coming this way—must have come through about the same water—" He caught himself up abruptly. Thorpe sensed that an Admiral of the Navy must not lend too credulous an ear to impossible stories.

"You've had an interesting experience, Mr. Thorpe," he said. "Most interesting. Probably a derelict is the answer, some hull just afloat. We will send out a general warning."

He handed the loose papers and the log book to the younger man. "This stuff is rubbish," he stated with emphasis. "Captain Wilkins held his command a year or so too long."

"You will do nothing about it?" Thorpe asked in astonishment.

"I said I would warn all shipping; there is nothing more to be done."

"I think there is." Thorpe's gray eye were steady as he regarded the man at the desk. "I intend to run it down. There have been other such instances, as you said—never explained. I mean to find the answer."

dmiral Struthers smiled indulgently. "Always after excitement," he said. "You'll be writing another book, I expect. I shall look forward to reading it ... but just what are you going to do?"

"I am going to the Islands," said Thorpe quietly. "I am going to charter a small ship of some sort, and I am going out there and camp on that spot in the hope of seeing those eyes and what is behind them. I am leaving to-night."

Admiral Struthers leaned back to indulge in a hearty laugh. "I refused you a passage on a destroyer once," he said, "and it was an expensive mistake. I don't make the same mistake twice. Now I am going to offer you a trip....

"The Bennington is leaving to-day on a cruise to Manila. I'll hold her an extra hour or two if you would like to go. She can drop you at Honolulu or wherever you say. Lieutenant Commander Brent is in command—you remember him in Manila, of course."

"Fine," Thorpe responded. "I'll be there."

"And," he added, as he took the Admiral's hand, "if I didn't object to betting on a sure thing I would make you a little proposition. I would bet any money that you would give your shirt to go along."

"I never bet, either," said Admiral Struthers, "on a sure loss. Now get out of here, you young trouble-shooter, and let the Navy get to work." His eyes were twinkling as he waved the young man out.

horpe found himself comfortably fixed on the Bennington. Brent, her commander, was a fine example of the aggressive young chaps that the destroyer fleet breeds. And he liked to play cribbage, Thorpe found. They were pegging away industriously the sixth night out when the first S.O.S. reached them. A mes[299]sage was placed before the commander. He read it and tossed it to Thorpe as he rose from his chair.

"S.O.S.," said the radio sheet, "Nagasaki Maru, twenty-four thirty-five N., one five eight West. Struck something unknown. Down at the bow. May need help. Please stand by."

Captain Brent had left the room. A moment later, and the quiver and tremble of the Bennington told Thorpe they were running full speed for the position of the stricken ship.

But: "Twenty-four thirty-five North," he mused, "and less than two degrees west of where the poor old Minnie R. got hers. I wonder ... I wonder...."

"We will be there in four hours," said Captain Brent on his return. "Hope she lasts. But what have they struck out there? Derelict probably, though she should have had Admiral Struthers' warning."

Robert Thorpe made no reply other than: "Wait here a minute, Brent. I have something to show you."

e had not told the officer of his mission nor of his experience, but he did so now. And he placed before him the wildly improbable statement of the late Captain Wilkins.

"Something is there," surmised Captain Brent, "just awash, probably—no superstructure visible. Your Minnie R. hit the same thing."

"Something is there," Thorpe agreed. "I wish I knew what."

"This stuff has got to you, has it?" asked Brent as he returned the papers of Captain Wilkins. He was quite evidently amused at the thought.

"You weren't on the ship," said Thorpe, simply. "There was nothing to see—nothing to tell. But I know...."

He followed Brent to the wireless room.

"Can you get the Nagasaki?" Brent asked.

"They know we are coming, sir," said the operator. "We seem to be the only one anywhere near."

He handed the captain another message. "Something odd about that," he said.

"U. S. S. Bennington," the captain read aloud. "We are still afloat. On even keel now, but low in water. No water coming in. Engines full speed ahead, but we make no headway. Apparently aground. Nagasaki Maru."

"Why, that's impossible," Brent exclaimed impatiently. "What kind of foolishness—" He left the question uncompleted. The radio man was writing rapidly. Some message was coming at top speed. Both Brent and Thorpe leaned over the man's shoulder to read as he wrote.

"Bennington help," the pencil was writing, "sinking fast—decks almost awash—we are being—"

In breathless silence they watched the pencil, poised above the paper while the operator listened tensely to the silent night.

gain his ear received the wild jumble of dots and dashes sent by a frenzied hand in that far-off room. His pencil automatically set down the words. "Help—help—" it wrote before Thorpe's spellbound gaze, "the eyes—the eyes—it is attack—"

And again the black night held only the rush and roar of torn waters where the destroyer raced quivering through the darkness. The message, as the waiting men well knew, would never be completed.

"A derelict!" Robert Thorpe exclaimed with unconscious scorn. But Captain Brent was already at a communication tube.

"Chief? Captain Brent. Give her everything you've got. Drive the Bennington faster than she ever went before."

The slim ship was a quivering lance of steel that threw itself through foaming waters, that shot with an endless, roaring surge of speed toward that distant point in the heaving waste of the Pacific, and that seemed, to the two silent men on the bridge, to put[300] the dragging miles behind them so slowly—so slowly.

"Let me see those papers," said Captain Brent, finally.

e read them in silence.

Then: "The eyes!" he said. "The eyes! That is what this other poor devil said. My God, Thorpe, what is it? What can it be? We're not all insane."

"I don't know what I expected to find," said Thorpe slowly. "I had thought of many things, each wilder than the next. This Captain Wilkins said the eyes were above him. I had visions of some sky monster ... I had even thought of some strange aircraft from out in space, perhaps, with round lights like eyes. I have pictured impossibilities! But now—"

"Yes," the other questioned, "now?"

"There were tales in olden times of the Kraken," suggested Thorpe.

"The Kraken!" the captain scoffed. "A mythical monster of the sea. Why, that was just a fable."

"True," was the quiet reply, "that was just a fable. And one of the things I have learned is how frequently there is a basis of fact underlying a fable. And, for that matter, how can we know there is no such monster, some relic of a Mesozoic species supposed to be extinct?"

He stood motionless, staring far out ahead into the dark. And Brent, too, was silent. They seemed to try with unaided eyes to penetrate the dark miles ahead and see what their sane minds refused to accept.

t was still dark when the search-light's sweeping beam picked up the black hull and broad, red-striped funnels of the Nagasaki Maru. She was riding high in the water, and her big bulk rolled and wallowed in the trough of the great swells.

The Bennington swept in a swift circle about the helpless hulk while the lights played incessantly upon her decks. And the watching eyes strained vainly for some signal to betoken life, for some sign that their mad race had not been quite vain. Her engines had been shut down; there was no steerage-way for the Nagasaki Maru, and, from all they could see, there were no human hands to drag at the levers of her waiting engines nor to twirl with sure touch the deserted helm. The Nagasaki Maru was abandoned.

The lights held steadily upon her as the Bennington came alongside and a boat was swung out smartly in its davits. But Thorpe knew he was not alone in his wild surmise as to the cause of the catastrophe.

"Throw your lights around the water occasionally," Brent ordered. "Let me know if you see anything."

"Yes sir," said the man at the search-light. "I will report if I spot any survivors or boats."

"Report anything you see," said Commander Brent curtly.

"You go aboard if you want to," he suggested to Thorpe. "I will stay here and be ready if you need help."

Thorpe nodded with approval as the small boat pulled away in the dark, for there was activity apparent on the destroyer not warranted by a mere rescue at sea. Gun-crews rushed to their stations; the tarpaulin covers were off of the guns, and their slender lengths gleamed where they covered the course of the boat.

"Brent is ready," Thorpe admitted, "for anything."

hey found the iron ladder against the ship's side, and a sailor sprang for it and made his way aboard. Thorpe was not the last to set foot on deck, and he shuddered involuntarily at the eery silence he knew awaited them.

It was the Minnie R. over again, as he expected, but with a difference. The sailing vessel, before he boarded it, had been for some time exposed to the sun, while the Nagasaki Maru had not. And here there were slimy trails still wet on the decks.[301]

He went first to the wireless room. He must know the final answer to that interrupted message, and he found it in emptiness. No radio man was waiting him there, nor even a body to show the loser of an unequal battle. But there was blood on the door-jamb where a body—the man's body, Thorpe was sure—had been smashed against the wood. A wisp of black hair in the blood gave its mute evidence of the hopeless fight. And the slime, like the trails on the deck, smeared with odorous vileness the whole room.

Thorpe went again to the deck, and, as on the other ship, he breathed deeply to rid his lungs and nostrils of the abhorrent stench. The ensign in charge of the boarding party approached.

"What kind of a rotten mess is this?" he demanded. "The ship is filthy and not a soul on board. Not a man of them, officers or crew, and the boats are all here. It's absolutely amazing, isn't it?"

"No," Thorpe told him, "about what we expected. What do you make of this?" He touched with his foot a broad trail that shone wet in the Bennington's lights.

"The Lord knows," said the ensign in wonder. "It's all over and it smells like a rotten dead fish. Well, we will be going back, sir." He called to a petty officer to round up the men, and the boat was brought alongside.

heir return to the Bennington again through a pathway of light that Thorpe knew was safe under the black muzzles of the destroyer's guns.

Or was it, he asked himself. Safe! Was anything safe from this devilish mystery that could pluck each cowering human from the lowest depths of this steel freighter, that could drag her down in the water till the radio man sent his cry: "We are sinking!..."

He told Brent quietly, after the ensign had reported, of the struggles in the wireless room and its few remaining traces. And he watched with the commander through the hour of darkness while the Bennington steamed in slow circles about the abandoned hulk, while her search-lights played endlessly over the empty waters and the men at the guns cast wondering glances at their skipper who ordered such strange procedure when no danger was there.

With daylight the scene lost its sense of mysterious threat, and Thorpe was eager to return to the abandoned ship.

"I might find something," he said, "some trace or indication of what we have to fight."

"I must leave," said Commander Brent. "Oh, I'm coming back, never fear," he added, at the look of dismay on Thorpe's face. The thought of leaving this mystery unsolved was more than that young seeker after adventure could accept.

"I'm coming back," Brent repeated. "I've been in communication with the Admiral—Honolulu has relayed the messages through. All code, of course; we mustn't alarm the whole Pacific with our nightmares. The old man says to stick around and get the low-down on this damn thing."

"Then why leave?" objected Thorpe.

ecause I am coming around to your way of thinking, Thorpe. Because I am as certain as can be that we have a monster of some sort to deal with ... and because I haven't any depth charges. I want to run up to the supply station at Honolulu and get a couple of ash-cans of TNT to lay on top of the brute if we sight him."

"Glory be!" said Thorpe fervently. "That sounds like business. Go and get your eggs and perhaps we can feed them to this devil—raw.... And I think I'll stay here, if you will be back by dark."

"Better not," the other objected; but Thorpe overruled him.

"This thing attacks in the dark," he said. "I will lay a little bet on that. It left the orang-outang on the Minnie[302] R.—quit at the first sign of daylight. I will be safe through the day, and besides, the beast has gutted this ship. It won't return, I imagine. And if I stay there for the day—live as they lived, the men who manned that ship—I may have some information that will be of help when you get back. But for Heaven's sake, Brent, don't stop to pick any flowers on the way."

"It's your funeral," said Brent not too cheerfully. "The old man said to give you every assistance, and perhaps that includes helping you commit suicide."

But Robert Thorpe only laughed as Commander Brent gave his orders for a small boat to be lowered. A ship's lantern and rockets for night signals were taken at the officer's orders. "We'll be back before dark," he said, "but take these as a precaution."

One favor Thorpe asked—that the ship's carpenter go over with him and help him to make a strong-barred retreat of the wireless cabin.

"And I'll talk to you occasionally," he told Brent. "I tried the key while I was aboard; the wireless is working on its batteries."

He waved a cheery good-by as the small boat pulled away. "And hurry back," he called. The destroyer commander nodded an emphatic assent.

n board the Nagasaki Maru, Thorpe directed the carpenter and his helpers in the work he wanted done. The man seemed to know instinctively where to put his hands on needed supplies, and the result was a virtual cage of strong oak bars enclosing the wireless room, and braces of oak to bar the single door. Thorpe was not assuming any bravado in his feeling of safety, but he was doing what he had done in many other tight corners, and he prepared his defences in advance.

These included weapons of offense as well. As the boat with the destroyer's men pulled back to the Bennington, he placed in easy reach in a corner of the room a heavy calibered rifle he had taken from his belongings.

And, still, with all his feeling of security, there was a strange depression fell upon him when the Bennington's narrow hull was small upon the horizon, and then that, too, was gone and only the heaving swells and the wallowing hulk were his companions.

Only these? He shivered slightly as he thought of that unseen watcher with the devil-eyes whose presence Captain Wilkins had felt—and his men, and the poor terrified ape! He deliberately put from his mind the thought of this; no use to start the day with morbid fears. He went below to examine the cabins. But he carried the heavy elephant gun with him wherever he went.

elow decks the signs of the marauder were everywhere, yet there was little to be learned. The slimy trails dried quickly and vanished, but not before Thorpe had traced them to the uttermost depths of the ship.

There was not a nook or corner that had gone unsearched in the horrible quest for human food. And one thing impressed itself forcibly upon the man's mind. He found a lantern, and he used it of necessity in his explorations, but this thing had gone through the dark and with unerring certainty had found its way to every victim.

"Can it see in the dark?" Thorpe questioned. "Or...." He visioned dimly some denizen of the vast depths, living beyond the limits of the sun's penetration, far in the abysmal darkness where its only light must be self-made. But his mind failed in the attempt to picture what manner of horror this thing might be.

Even in the hold its evil traces were found. There were tiers of metal drums that still shone wet in his lantern's light. Calcium carbide—for making acetylene, he supposed—marked "Made in U.S.A." The Nagasaki must have been westward bound.[303]

e went, after an hour or so, to the wireless room, and only when he relaxed in the safety of his improvised fortress did he realize how tense had been every nerve and muscle through his long search. He tried the wireless and got an instant response from the destroyer.

"Don't shoot it too fast," he spelled out slowly to the distant operator: "I am only a dub. Just wanted to say hello and report all O.K."

"Fine," was the steady, careful response. "We have had a little trouble with our condensers—" There was a short pause, then the message continued, this portion dictated by the commander. "Delay not important. We will be back as agreed. Have picked up S. S. Adelaide bound east in your latitude. Warned her to take northerly course account derelict. See you later. Signed, Brent, commanding U. S. S. Bennington."

The man in the barred room tapped off his acknowledgement and closed the key. He suddenly realized he had had no breakfast, and the hours had been slipping past. He took his gun again and went down to the galley to prepare some coffee. It was not the time or place for an enjoyable meal, but he would have relished it more had he not pictured the Adelaide and her lovely owner steaming across these threatening seas.

He knew the captain of the Adelaide. "Obstinate pigheaded old Scotchman!" "Hope he takes Brent's advice. Of course Brent couldn't tell him the truth. We can't blat this wild yarn all over the air or the passenger lines would have our scalps. But I wish the Adelaide was safe in Manila."

is explorations in the afternoon were half-hearted and perfunctory. There was nothing more to be learned. But he had seen in his mind some vague outline of what they must meet. He saw a something, mammoth, huge, that could grasp and hold an ocean freighter—against whose great body he had seen the waves dash in a line of white spray. Yet a something that could force its way down narrow passages, could press with terrific strength on bolted doors and crush them inward, wrecked and splintered. Some serpentine thing that felt and saw its way and crawled so surely through the dark—found its prey—seized it—and carried off a man as easily as it might a mouse.

No octopus, no matter what proportions, filled the description. He gave up trying to see too clearly the awful thing. And he kept away from the ship's rail when once he had ventured near. For there had come to him a feeling of fear that had sent the waves of cold trickling and prickling up his spine. Was there something really there?... A waiting lurking horror in the depths?

"The eyes," he thought, "the eyes!..." And he went more quickly than he knew to his barred retreat where again he might breathe quietly.

he position of the deserted ship was south of the regular steamer lanes on the TransPacific run. Only a trace of smoke on the northern horizon marked through the afternoon the passage of other craft. It was a long and lonely vigil for the waiting man. But the Bennington would return, and he listened in at intervals hoping to hear her friendly signal.

The batteries operating the Nagasaki's wireless were none too strong; Thorpe saved their strength, though he tried at times to raise the Bennington somewhere beyond his reach.

The sun was touching the horizon when he got his first response. "Keep up the old nerve," admonished the slow, careful sending of the Bennington's operator. "We have been delayed but we are on our way. Signed, Brent."

The man in the wireless room placed the oak bars across the door, and tried to believe he was nonchalant and unafraid as he laid out extra clips of cartridges. But his eyes persisted in[304] following the sinking sun, and he watched from within his cage the coming of the quick dark.

The protecting glare of day must be unbearable to this monster from the lightless depths, and daylight was vanishing. Thorpe's mind was searching for additional means of defense. He found it in the cargo he had seen. The drums of carbide! He could scatter it on the deck—it reacted with water, and those slimy arms, if they came and touched it, could find the contact hot. He took his lantern and went hastily below to stagger back with a drum upon his shoulder.

In the half-light that was left him he forced the cover and then rolled the drum about the swaying deck. The gray, earthly lumps of carbide formed erratic lines. Useless perhaps, he admitted, but the threatening dark forced the man to use every means at his command.

e was scattering the contents of a second drum when he stiffened abruptly to rigid attention.

The ship, thrown broadside to the wide-spaced swells, had rolled endlessly with a monotonous motion. But now the deck beneath him was steadying. It assumed an abnormal levelness. The boat rose and fell with the waves, but it no longer rolled. There was something beneath holding, drawing on it.

Thorpe knew in that frozen second what it meant. The drum clattered to the rail as he dashed for his room. Gun in hand, he watched with staring eyes where the deserted deck showed dim and vague in the light of the stars and the bow of the ship was lost in the uncertain dark of night.

Wide-eyed he watched into the blackness, and he listened with desperate attention for some slightest sound beyond the splashing of waves and the creaking of spars.

Far in the west a light appeared, to glow and vanish and glow again in the tumbling waters. The Bennington! His heart leaped at the thought, then sank as he knew the destroyer's lights would not appear from that direction.

Through a slow hour that seemed an eternity the oncoming ship drew near, and he knew with a sudden, startling certainty that it was the Adelaide—and Ruth Allaire—coming on, through into the horror awaiting.

He leaned forward tensely as a sound reached his ears. A ghostly echo of a sound, like the softest of smooth, slipping fabric upon hard steel. And as he listened, before his staring eyes, a something came between him and the lighted yacht.

It wavered and swung in the darkness. It was formless, uncertain of outline, and it swung in the night out beyond the ship's rail till it suddenly neared, waved high overhead, and the cold light of the stars shone in pale reflection from an enormous, staring eye.

It surmounted a serpentine form that took shape in the dim radiance without and came lower in undulating folds to crash heavily upon the deck.

horpe's hand was upon the wireless key. He had wanted to warn off the yacht, but not till the thud of the creature on the bare deck proved its reality could he force his cold fingers to press the key.

Then, fast as his inexperience allowed, he called frantically for the Adelaide. He spelled her name, over and over.... Would the sleepy operator never answer?

The Bennington broke in one. "Is that you, Thorpe? What is up?" they demanded.

But Thorpe kept up his slow spelling of the yacht's name. He must get a warning to them! Then he realized that the Bennington could do it better.

"Bennington," he called, "Adelaide approaching. I am attacked. Warn them off. Warn them—" His frantic, hissing dots and dashes died immediately. Beneath his feet the Nagasaki Maru was rolling again, swinging free to the[305] lift and thrust of the swells beneath.

"Good God!" he shouted aloud in his lonely cabin. "It's gone for the yacht. Adelaide—turn north—full speed—" he clicked off on a slow, stuttering key. "Head north. You are being attacked!" He groaned again as he saw the Adelaide's shining ports swing away from the safety of the north; the ship broached broadside to the waves and came slowly to a stop.

"Bennington," he radioed. "Brent—it has got the Adelaide. Help—hurry! I am going over."

He tore wildly at the barred door, and he made a dash across the deck to slip sprawling in a heap against the rail where the slimy traces of the recent visitor stretched glistening on the deck.

ow he lowered the boat Thorpe never knew. But he knew there was one that the men from the Bennington had swung over the side, and tore madly at the tackle to let the boat crash miraculously upright into the sea. He slung the rifle about his neck with a rope end—there were cartridges in his pocket—and he went down the dangling lines and cast off in a frenzy of haste.

What could he do? He hardly dared form the question. Only this stood clear and unanswerable in his mind: The yacht was in the monster's grip, and Ruth Allaire was there on board. Ruth Allaire, so smiling, so friendly, so lovable! Food for that horror from the depths.... He rowed with super-human strength to drive the heavy boat across the wave-swept distance that separated them.

Between gasping breaths he turned at times to glance over his shoulder and correct his course. And now, as he drew near, he saw though indistinct the unmistakable, snakelike weaving of horrible tenuous fingers, rolling and groping about the yacht.

They were plain as he drew alongside. The trim ship rose and fell with the water, while over her side where Thorpe approached swung a long, white monstrous rope of flesh. It retreated like the lash of a whip, and the horrified watcher saw as it went the struggling figure of a man in the grasp of flabby lips. And above them a single eye glared wickedly.

Another vile, twisting arm rose from the afterdeck with a screaming figure in its grasp and vanished into the water beyond the yacht. There were others writhing about the decks. Thorpe saw them as he made his boat fast and clambered aboard.

wave of reeking air enveloped him as he reached the deck; the nauseous stench from the monster's tentacles was horrible beyond endurance. He gagged and choked as the stifling breath entered his lungs.

A huge rope of slippery, throbbing flesh stretched its twisted length toward the stern. It contracted as he watched into bulging muscular rings and withdrew from the afterdeck. The deadly end of it stopped in mid-air not twenty feet from where he stood. The jawlike pincers on it held the limp form of an officer in its sucking grip, while above, in a protuberance like a gnarled horn, a great eye glared into Thorpe's with devilish hatred.

The beak opened sharply to drop its unconscious burden upon the deck, and the watching man, petrified with horror, saw within the gaping maw great sucking discs and beyond them a brilliant glow. The whole cavernous pit was aflame with phosphorescent light. Dimly he knew that this light explained the ability of the beastly arms to grope so surely in the dark.

The eye narrowed as the gaping, fleshy jaws distended, and Robert Thorpe, in a flash that galvanized him to action, was aware that his fight for life was on. He fired blindly from the hip, and the recoil of the heavy gun almost tore it from his hands. But he knew he had aimed true, and the toothless, seeking jaws whipped in agony back into the sea.[306]

There were other arms whose eyes were searching the stern of the yacht. Thorpe plunged frenziedly down a companionway for the cabin he knew was Ruth Allaire's. Was he in time? Could he save her if he found her? His mind was in a turmoil of half-formed plans as he rushed madly down the corridor to find the body of the girl a limp huddle across the threshold of her cabin.

he was alive; he knew it as he swung her soft body across one shoulder and staggered with his burden up the stairs. If he could only breathe! His throat was tight and strangling with the reeking putrescence in the air. And before his eyes was a picture of the strong oak bars of his own retreat. Somehow, some way, he must get back to the abandoned ship.

An eye detected him as he came on deck, and he dropped the limp body of the girl at his feet as he swung his rifle toward the glowing light within the opening jaws. The sucking discs cupped and wrinkled in dread readiness in the fleshy, toothless opening. He emptied the magazine into the head, though he knew this was only a feeler and a feeder for a still more horrible mouth in the monstrous body that rose and fell tremendously in the dark waters beyond. But it was typical of Robert Thorpe that even in the horror and frenzy of the moment he rammed another clip of cartridges into his rifle before he stooped to again raise the prostrate figure of Ruth Allaire.

The forward deck for the moment was clear; it rose high with the weight of the writhing, twisting arms that weighed down the stern of the yacht where the crew had taken refuge.

To think of helping them was worse than folly—he dismissed the thought as another great eye came over the rail. Once more he used the gun, then lowered the girl to the waiting boat, and cast off and rowed with the stealthiest of strokes into the dark.

ehind him were whipping points of light above the white brilliance of the yacht Adelaide. The boat was tossing in great waves that came from beyond, where a body, incredibly huge, was tearing the waters to foam. There were ghostly arms that shone in slimy wetness, that lashed searchingly in all directions, as the monster gave vent to its fury at Thorpe's attack. There were screaming human figures grasped in many of the jaws, and the man was glad with a great thankfulness that the girl's stupor could save her from the frightful sight.

He dared to row now, and his breath was coming in great choking sobs of sheer exhaustion when at last he pulled the senseless form of Ruth Allaire to the deck of the Nagasaki and drew her within the frail shelter of the wireless room.

Stout had the oaken bars appeared, and safe his refuge in the barricaded room, but that was before he had seen in horrible reality the fearful fury of this monster from the deep. He placed the braces against the door and turned with hopeless haste to seize the wireless key.

"Bennington," he called, and the answer came strong and clear. "Where are you.... Help—" His fingers froze upon the key and the answering message in his ears was unheeded as he watched across the water the destruction of the yacht.

This craft that had dared to resist the onset of the brute, to fight against it, to wound it, was feeling the full fury of the monster's rage. The gleaming lights of the doomed ship were waving lines that swept to and fro in the grip of those monstrous arms. The boat beneath Thorpe's feet was tossing in the waves that told of the titanic struggle. He had meant to look south for some sign of the oncoming destroyer, but in fearful fascination he stared spellbound where the masts of the trim yacht swept downward into the waves, where the green of her star-[307]board lantern glowed faintly for an instant, then vanished, to leave only the darkness and the starlit sea.

voice aroused him from his stupefaction. "Where am I ... where am I?" Ruth Allaire was asking in a frightened whisper. "That terrible thing—" She shuddered violently as memory returned to show again the horror she had witnessed. "Where are we, Robert? And the Adelaide—where is it?"

Thorpe turned slowly. The insane turmoil of the past hour had numbed his brain, stunned him.

"The Adelaide—" he mumbled, and groped fumblingly for coherent thoughts. He stared at the girl. She was half-risen from the floor where he had laid her, and the sight of her quivering face brought reason again to his mind. He knelt tenderly beside her and raised her in his arms.

"Where is the yacht?" she repeated. "The Adelaide?"

"Gone," Thorpe told her. "Lost!" A thought struck him.

"Was your father on board, Ruth?"

Ruth was dazed.

"Lost," she repeated. "The Adelaide—lost!... No," she added in belated response to Thorpe's question. "Daddy was not there. But the men—Captain MacPherson ... that horrible monster...." She buried her face in her hands as she realized what Thorpe's silence meant.

He held the trembling figure close as the girl whispered: "Where are we, Robert? Are we safe?"

"We may win through yet," he told her through grim, set lips. He realized abruptly that he was seeing the face of Ruth Allaire in the light. He had left a lantern burning! He withdrew his arms from about her and sprang quickly to his feet to put out the tell-tale light. In darkness and quiet was their only safety. And he knew as he sprang that he had waited too long. A soft body crashed heavily on the deck outside.

he girl's voice was shrill with terror as she began a question. Thorpe's hand pressed upon her lips in the dark where he stood waiting—waiting.

A luminous something was glowing outside the cabin. It searched and prodded about the deserted deck to whip upward at the audible hiss of wet carbide. Another appeared; the rifle came slowly to the man's shoulder as a pair of jaws gaped glowingly beyond the windows and an eye stared unblinkingly from its hornlike sheath. It crashed madly against the walls of the wireless room to shatter the glass and make kindling of the woodwork of the sash. Thorpe fired once and again before the specter vanished, and he knew with sickening certainty that the wounds were only messages to some central brain that would send other ravening tentacles against them. But the oak bars had held.

He reached in the brief interval for the key, and he sent out one final call for help. He strained his ears against the head-set for some friendly human word of hope.

"—rocket," the wireless man was saying. "Fire rockets. We can't find—" A swift, writhing arm wrapped crushingly about the cabin as the message ceased.

horpe seized his rifle and fired into the gray mass that bulged with terrible muscular contractions through the window. He fired again to aim lengthways of the arm and inflict as damaging a wound as his weapon would permit.

The arm relaxed, but a score of others took up the attack. Again the sickening stench was about them as gaping jaws gleamed fiery beneath the hateful eyes and tore at the flimsy structure. Thorpe jammed more cartridges into the gun and fired again and again, then dropped the weapon to fumble for the rockets that Brent had given him.

He lighted one with trembling[308] fingers; the first ball shot straight into a waiting mouth. Another ignited a searing flame of acetlylene gas where a wet arm writhed in the hot carbide trail. The man leaned far out through the broken window.

No time to look around. He let the red flares stream upward high into the air, then dropped the rocket hissing on the deck to seize once more the rifle.

A mass of muscle crashed against the door; it went to splinters under the impact, and only the two oak bars remained to hold in check the horrible tentacles and the darting heads. One mouth closed to a pointed end that forced its way between the bars. The oak gave under the strain as Robert Thorpe pulled vainly at an empty gun. Beside him rose shrieks of terror as the monstrous thing came on, and Thorpe beat with frantic fury with his clubbed rifle at the fleshy snout.

He knew as he swung the weapon that the shrieks had ceased, then smiled grimly in the numbing horror as he realized that Ruth Allaire was beside him. A piece of oak was in her hands, and she was striking with desperate and silent fury at the slimy flesh.

t was the end, Thorpe knew, and suddenly he was glad. The nightmare was over, and the end was coming with this girl beside him. But Robert Thorpe was fighting on to the last, and he tried to make his blows reach outward to the hateful devilish eye.

He saw it plainly now, for the deck was a glare of white light. He saw the eye and the thick arm behind it and the score of others that made a heaving, knotted mass were brilliant and wetly shining. He could see now how best to strike, and he turned his gun to thrust with the barrel at the eye.

It withdrew before his stroke—the jaws slid backward to the deck. There were sounds that hammered at his ears. "The guns! The guns!" a girl was screaming. Across the deck, where a search-light played, huge arms were lashing backward toward the sea. The waves beyond had vanished where a monstrous body shone wetly black in a blinding glare.

And the man hung panting, helpless, on the one remaining bar across the doorway to look where, beyond, her forward guns a spitting stream of staccato flashes, the Bennington tore the waves to high-thrown spray. Her four clean funnels swung far over as the slim ship, with her stabbing, crashing guns, swung in a sweeping circle to bear down upon the black bulk slowly sinking in the search-light's glare.

The vast body had vanished as the destroyer shot like one of her own projectiles over the spot where the beast had lain. And then, where she had passed, the sea arose in a heaving mound. The big ship beneath the watching man shuddered again as another depth charge grumbled its challenge to the master of the deeps.

he warship went careening on an arc to return and throw the full glare of her search-lights on the scene. They lighted a vast sea, strangely stilled. An oily smoothness leveled waves and ironed them out to show more clearly the convulsions of a torn mass that rose slowly into sight.

Thorpe in some way found himself outside the cabin. And he knew that the girl was again beside him as he stared and stared at what the waters held. A bloated serpent form beyond believing was struggling in the greasy swell. Its waving tentacles again were flung aloft in impotent fury, and, beneath them, where their thick ends jointed the body, a head with one horrible eye rose into the air. A thick-lipped mouth gaped open, and the gleam of molars shone white in the blinding glare.

The twisting body shuddered throughout its vast bulk, and the waving arms and futile staring eyes dropped helpless into the splashing sea. Again the revolting head was[309] raised as the destroyer sent a rain of shells into its fearful mass. Once more the oily seas were calm. They closed over the whirling vortex where a denizen of the lightless depths was returning to those distant, subterranean caverns—returning as food for what other voracious monsters might still exist.

The man's arm was about the figure of the girl, trembling anew in a fresh reaction from the horror they had escaped, when a small boat drew alongside.

"They're safe," a hoarse voice bellowed back to the destroyer, and a man came monkeywise up a rope where Thorpe had launched his boat.

And now, as one in a dream, Thorpe allowed the girl to be taken from him, to be lowered to the waiting boat. He clambered down himself and in silence was rowed across to the destroyer.

"Thank God!" said Brent, as he met them at the rail. "You're safe, old man ... and Miss Allaire ... both of you! You let off that rocket just in time; we couldn't pick you up with our light—

"And now," he added, "we're going back; back to San Diego. The Admiral wants a word of mouth report."

Thorpe stilled him with a heavy gesture. "Give Ruth an opiate," he said dully. "Let her forget ... forget!... Good God, can we ever forget—" He stumbled forward, heedless of Brent's arm across his shoulders as the surgeon took the girl in charge.

dmiral Struthers, U.S.N., leaned back from his desk and blew a cloud of smoke thoughtfully toward the ceiling. He looked silently from Thorpe to Commander Brent.

"If either one of you had come to me with such a report," he said finally, "I would have found it incredible; I would have thought you were entirely insane, or trying some wild hoax."

"I wish it were a damn lie," said Thorpe quietly. "I wish I didn't have to believe it." There were new lines about the young-old eyes, lines that spoke what the lips would not confess of sleepless nights and the impress of a picture he could not erase.

"Well, we have kept it out of the papers," said the Admiral. "Said it was a derelict, and the wild messages floating about were from an inexperienced man, frightened and irresponsible. Bad advertising—very—for the passenger lines."

"Quite," Commander Brent agreed, "but of course Mr. Thorpe may want to use this in his next book of travel. He has earned the right without doubt."

"No," said Thorpe emphatically. "No! I told you, Brent, there was often a factual basis for fables—remember? Well, we have proved that. But sometimes it is best to leave the fables just fables. I think you will agree." A light step sounded in the corridor beyond. "Nothing of this to Miss Allaire," he said sharply.

The men rose as Ruth Allaire entered the room. "We were just speaking," said the Admiral with an engaging smile beneath his close-cut mustache, "of the matter of a bet. Mr. Thorpe has won handily, and he has taught me a lesson."

He took a check book from his desk. "What charity would you like to name, Miss Allaire? That was left to you, you remember."

"Some seamen's home," said Ruth Allaire gravely. "You will know best, if you two are really serious about that silly bet."

"That bet, my dear," said Robert Thorpe with smiling eyes, "was very serious ... and it has had most serious consequences." He turned to the waiting men and extended a hand in farewell.

"We are going to Europe, Ruth and I," he told them. "Just rambling around a bit. Our honeymoon, you know. Look us up if you're cruising out that way."

"As the madness grew, the two men fought. They were

murder mad. The local sub-deputy gave his guests the thrill of

watching maniacs battling to the death."

"As the madness grew, the two men fought. They were

murder mad. The local sub-deputy gave his guests the thrill of

watching maniacs battling to the death."even United States Secret Service men have disappeared in South America. Another is found—a screaming homicidal maniac. It is rumored that they are victims of a diabolical poison which produces "murder madness."

Charley Bell, of the "Trade"—a secret service organization that does not officially exist—discovers that a sinister system of slavery is flourishing in South America, headed by a mysterious man known only as The Master. This slavery is accomplished by means of a poison which causes its victims to experience a horrible writhing of the hands, followed by a madness to do murder, two weeks after the poison is taken.

The victims get relief only with an antidote supplied through Ribiera, The Master's Chief Deputy; but in the antidote there is more of the poison which again in two weeks will take effect. And so it is that a person who once receives the poison is forever enslaved.

Bell learns that Ribiera has kidnapped[311] Paula Canalejas, daughter of a Brazilian cabinet minister—himself a victim—who has killed himself on feeling the "murder madness," caused by the poison, coming over him. Bell corners Ribiera in his home, buries the muzzles of two six-guns in his stomach, and demands that he set Paula free.

n this room the electric lights were necessary at all times. And it occurred to Bell irrelevantly that perhaps there were no windows because there might be sometimes rather noisy scenes within these walls. And windows will convey the sound of screaming to the outside air, while solid walls will not.

He stood alert and grim, with his revolvers pressing into Ribiera's flabby flesh. His fingers were tensed upon the triggers. If he killed Ribiera, he would be killed. Of course. And men and women he had known and liked might be doomed to the most horrible of fates by Ribiera's death. Yet even the death or madness of many men was preferable to the success of the conspiracy in which Ribiera seemed to figure largely.

Ribiera looked up at him with the eyes of a terrified snake. There was a little stirring at the door.

"Your friends," said Bell softly, "had better not come close."

Ribiera gasped an order. The stirrings stopped. Paula came slowly into the room quite alone. She smiled queerly at Bell.

"I believed that you would come," she said quietly. "And yet I do not know that we can escape."

"We're going to try," said Bell grimly. To Ribiera he added curtly, "You'd better order the path cleared to the door, and have one of your cars brought around."[312]

ibiera croaked a repetition of the command.

"Now stand up—slowly," said Bell evenly. "Very slowly. I don't want to die, Ribiera, so I don't want to kill you. But I haven't much hope of escape, so I shan't hesitate very long about doing it. And I've got these guns' hammers trembling at full cock. If I get a bullet through my head, they'll go off just the same and kill you."

Ribiera got up. Slowly. His face was a pasty gray.

"Your major-domo," Bell told him matter-of-factly, "will go before us and open every door on both sides of the way to the street. Paula"—he used her given name without thought, or without realizing it—"Paula will go and look into each door. If she as much as looks frightened, I fire, and try to fight the rest of the way clear. Understand? I'm going to get down to a boat I have ready in the harbor if I have to kill you and every living soul in the house!"

There was no boat in the harbor, naturally. But the major-domo moved hesitantly across the room, looking at his master for orders. For Ribiera to die meant death or madness to his slaves. The major-domo's face was ghastly with fear. He moved onward, and Bell heard the sound of doors being thrust wide. Once he gave a command in the staccato fashion of a terrified man. Bell nodded grimly.

"Now we'll move. Slowly, Ribiera! Always slowly.... Ah! That's better! Paula, you go on before and look into each room. I shall be sorry if any of your servants follow after you, Ribiera.... Through the doorway. Yes! All clear, Paula? I'm balancing the hammers very carefully, Ribiera. Very delicate work. It is fortunate for you that my nerves are rather steady. But really, I don't much care.... Still all clear before us, Paula? With the servants nerve-racked as they are, I believe we'll make it through, even if I do kill Ribiera. There'll be no particular point in killing us then. It won't help them. Don't stumble, please, Ribiera.... Go carefully, and very slowly...."

ibiera's face was a gray mask of terror when they reached the door. A long, low car with two men on the chauffeur's seat was waiting.

"Only one man up front, Ribiera," said Bell dryly. "No ostentation, please. Now, I hope your servants haven't summoned the police, because they might want to stop me from marching you out there with a gun in the small of your back. And that would be deplorable, Ribiera. Quite deplorable."

With a glance, he ordered Paula into the tonneau. He followed her, driving Ribiera before him. There seemed to be none about but the stricken, terrified servant who had opened the door for their exit.

"My friend," Bell told the major-domo grimly, "I'll give you a bit of comfort. I'm not going to try to take the Senhor Ribiera away with me. Once I'm on board the yacht that waits for me, I'll release him so he can keep you poor devils sane until my Government has found a way to beat this devilish poison of his. Then I'll come back and kill him. Now you can tell the chauffeur to drive us to the Biera Mar."

He settled back in his seat. There were beads of perspiration on his forehead, but he could not wipe them off. He held the two revolvers against Ribiera's flabby body.

he car turned the corner, and he added dryly:

"Your servants, Ribiera, will warn your more prominent slaves of my intention of going on board a yacht. Preparations will be made to stop every pleasure boat and search it for me. So ... tell your chauffeur to swing about and make for the flying field. And tell him to drive carefully, by the way. I've still got these guns on a very fine adjustment of the trigger-pressure."[313]

Ribiera croaked the order. Bell was exactly savage enough to kill him if he did not escape.

For twenty minutes the car sped through the residential districts of Rio. The sun was high in the air, but clouds were banking up above the Pao d'Assucar—the Sugarloaf—and it looked as if there might be one of the sudden summer thunderstorms that sometimes sweep Rio.

Then the clear road to the flying field. Rio has the largest metropolitan district in the world, but a great deal of it is piled on end, and Rio itself built on most of the rest. The flying field is necessarily some miles from even the residential districts, for the sake of a level plain of sufficient area.

The car shot ahead through practically untouched jungle, interspersed with tiny clearings in which were patchwork houses that might have been a thousand miles in the interior instead of so near the center of all civilization in Brazil. Up smooth gradients. Around beautifully engineered curves.

ell put aside one revolver long enough to search Ribiera carefully. He found a pearl-handled automatic, and handed it to Paula.

"Worth having," he said cheerfully. "I wonder if you'd mind searching the chauffeur: with that gun at his head I think he'd be peaceful. You needn't have him stop."

Paula stood up, smiling a little.

"I did not think I lacked courage, Senhor," she observed, "but you have taught me more."

"Nil desperandum," said Bell lightly. He relaxed deliberately. Matters would be tense at the flying field, and he would need to be wholly calm. There was little danger of an attempt at rescue here, and the necessity of being ready to shoot Ribiera at any instant was no longer a matter of split seconds.

He watched, while, bent over the back of the front seat, she extracted two squat weapons from the chauffeur's pockets.

"Quite an arsenal," said Bell as he pocketed them. He turned pleasantly to Ribiera. "Now, Ribiera, you understand just what I want. That big amphibian plane of yours is fairly fast, and once when I was merely your guest you assured me that it was always kept fueled and even provisioned for a long flight. When we reach the flying field I want it rolled out and warmed up, over at the other end of the field from the flying line. We'll go over to it in the car.

"And I've thought of something. It worried me, before, because sometimes if a man's shot he merely relaxes all over. So while we're at the flying field I'm going to be holding back the triggers of these guns with my thumbs. I don't have to pull the trigger at all—just let go and they'll go off. It isn't so fine an adjustment as I had just now, but it's safer for you as long as you behave. And you might urge your chauffeur to be cautious. I do hope, Ribiera, that you won't look as if you were frightened. If there's any hitch, and delay for letting some fuel out of the tanks or messing up the motors, I'll be very sorry for you."

he car swooped out into bright sunshine. The flying field lay below, already in the shadow of the banking clouds above. Hangars lay stretched out across the level space.

Through the gates. Ribiera licked his lips. Bell jammed the revolver muzzles closer against his sides. The chauffeur halted the car. Paula spoke softly to him. He stiffened. Bell found it possible to smile faintly.

Ribiera gave orders. There was a moment's pause—the revolver muzzles went deeper into his side—and he snarled a repetition. The official cringed and moved swiftly.

"You have chosen your slaves well, Ribiera," said Bell coolly. "They seem to occupy all strategic positions. We'll ride across."

The gears clashed. The car swerved forward and went deliberately across[314] the wide clear space that was the flying field. It halted near the farther side. In minutes the door of a hangar swung wide. There was the sputtering of a not-yet-warmed-up motor. The big plane came slowly out, its motors coughing now and then. It swung clumsily across the field, turned in a wide circle, and stopped some forty or fifty feet from the car.

"Send the mechanic back, on foot," said Bell softly.

Again Ribiera found it expedient to snarl. And Bell added, gently, while the throttled-down motors of the big amphibian boomed on:

"Now get out of the car."

Tiny figures began to gaze curiously at them from the row of hangars. The mechanic, starting back on foot, the four people getting out of the car, the big plane waiting....

ith his revolver ready and aimed at Ribiera's bulk, Bell reached in the front of the car and turned off the switch. The motor died abruptly. He put the key in his pocket.

"Just to get a minute or two extra start," he said dryly. "Climb up in the plane, Paula."

She obeyed, and turned at the top.

"I will cover them until you are up," she said quietly.

Bell laughed, now. A genuine laugh, for the first time in many days.

"We do work together!" he said cheerfully.

But he backed up the ladder. There was a stirring over by the hangars. The mechanic who had taxied the plane to this spot was a dwindling speck, no more than a third of the way across the field. But even from the distant hangars it could be seen that something was wrong.

"Close the door, Paula," said Bell. He had seated himself at the controls, and scanned the instruments closely.

This machine was heavy and large and massive. The boat-body between the retractable wheels added weight to the structure, and when Bell gave it the gun it seemed to pick up speed with an irritating slowness, and to roll and lurch very heavily when it did begin to approach flying speed. The run was long before the tail came up. It was longer before the joltings lessened and the plane began to rise slowly, with the solid steadiness that only a large and heavily loaded plane can compass.

p, and up.... Bell was three hundred feet high when he crossed the hangars and saw tiny faces staring up at him. Some of the small figures were pointing across the field. The big plane circled widely, gaining altitude, and Bell gazed down. Ribiera was gesticulating wildly, pointing upward to the soaring thing, shaking his fist at it, and making imperious, frantic motions of command.

Bell took one quick glance all about the horizon. Toward the sea the sun shone down brilliantly upon the city. Inland a broad white wall of advancing rain moved toward the coastline. And Bell smiled frostily, and flung the big ship into a dive and swooped down upon Ribiera as a hawk might swoop at a chicken.

Ribiera saw the monster thing bearing down savagely, its motors bellowing, its nose pointed directly at him. And there is absolutely nothing more terrifying upon the earth than to see a plane diving upon you with deadly intent. A panic that throws back to non-human ancestors seizes upon a man. He feels the paralysis of those ancient anthropoids who were preyed upon by dying races of winged monsters in the past. That racial, atavistic terror seizes upon him.

Bell laughed, though it sounded more like a bark, as Ribiera flung himself to the ground and screamed hoarsely when the plane seemed about to pounce upon him. The shrill timbre of the shriek cut through the roaring of the motors, even through the thick padding of the big plane's cabin walls that reduced that roaring to a not intolerable growl.[315]

ut the plane passed ten feet or more above his head. It rose, and climbed steeply, and passed again above the now buzzing, agitated hangars, and climbed above the hills behind the flying field as some men went running and others moved by swifter means toward the shaken, nerve-racked Ribiera, on whose lips were flecks of foam.

Bell looked far below and far behind him. The incredible greenness of tropic verdure, of the jungle which rings Rio all about. The many glitterings of sunlight upon glass, and upon the polished domes of sundry public buildings, and the multitudinous shimmerings of the tropic sun upon the bay. The deep dark shadow of the banking clouds drew a sharp line across the earth, and deep in that shadow lay the flying field, growing small and distant as the plane flew on. But specks raced across the wide expanse. In a peculiar, irrational fashion those specks darted toward a nearly invisible speck, and encountered other specks darting away from that nearly invisible speck, and gradually all the specks were turned about and racing for the angular, toy-block squares which were the hangars of the aeroplanes of the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Little white things appeared from those hangars—planes being thrust out into the open air while motes of men raced agitatedly about them. One of them was suddenly in motion. It moved slowly and clumsily across the ground, and then abruptly moved more swiftly. It seemed to float upward and to swing about in mid-air. It came floating toward the amphibian, though apparently nearly stationary against the sky. Another moved jerkily, and another....

ust before the big plane dived into the wide white wall of falling water, the air behind it seemed to swarm with aircraft.

In the cabin of the amphibian, of course, the bellowing of the motors outside was muffled to a certain degree. Paula clung to the seats and moved awkwardly up to the place beside Bell. She had just managed to seat herself when the falling sheet of water obliterated all the world.

"Strap yourself in your seat," he said in her ear above the persistent tumult without. "Then you might adjust my safety-belt. Well be flying blind in this rain. I hope the propellers hold."

She fumbled, first at the belt beside his upholstered chair, and only afterward adjusted her own. He sent a quick glance at her.

"Shouldn't have done that," he said quietly. "I can manage somehow."

The plane lurched and tumbled wildly. He kicked rudder and jerked on the stick, watching the instrument board closely. In moments the wild gyrations ceased.

"The beginning of this," he said evenly, "is going to be hectic. There'll be lightning soon."

Almost on his words the gray mist out the cabin windows seemed to flame. There was thunder even above the motors. But the faint, perceptible trembling of the whole plane under the impulse of its engines kept on. Bell kept his eyes on the bank and turn indicator, glancing now and then at the altimeter.

"We've got to climb," he said shortly, "up where the lightning is, too. We want to pass the Serra da Carioca with room to spare, or we'll crash on it."