The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Negro Farmer, by Carl Kelsey This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Negro Farmer Author: Carl Kelsey Release Date: August 17, 2009 [EBook #29714] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NEGRO FARMER *** Produced by Tom Roch, Stephanie Eason, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images produced by Core Historical Literature in Agriculture (CHLA), Cornell University.)

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Introduction | 5 |

| II. | Geographic Location | 9 |

| III. | Economic Heritage | 22 |

| IV. | Present Situation | 29 |

| Virginia | 32 | |

| Sea Coast | 38 | |

| Central District | 43 | |

| Alluvial Region | 52 | |

| V. | Social Environment | 61 |

| VI. | The Outlook | 67 |

| VII. | Agricultural Training | 71 |

| Population Maps | 80 |

In the last three hundred years there have been many questions of general interest before the American people. It is doubtful, however, if there is another problem, which is as warmly debated to-day as ever and whose solution is yet so uncertain, as that of the Negro. In the second decade of the seventeenth century protests were being filed against black slavery, but the system was continued for nearly 250 years. The discussion grew more and more bitter, and to participation in it ignorance, then as now, was no bar. The North had less and less direct contact with the Negro. The religious hostility to human bondage was strengthened by the steadily increasing difference in economic development which resulted in the creation of sectional prejudices and jealousies. The North held the negro to be greatly wronged, and accounts of his pitiable condition and of the many individual cases of ill treatment fanned the flames of wrath. The reports of travelers, however, had little influence compared with the religious sentiments which felt outraged by the existence of bond servitude in the land. Through all the years there was little attempt to scientifically study the character of the problem or the nature of the subject. A mistaken economic sentiment in the South and a strong moral sentiment at the North rendered such studies unnecessary, if not impossible. The South, perceiving the benefits of slavery, was blind to its fundamental weaknesses, and the North, unacquainted with Negro character, held to the natural equality of all men. Thus slavery itself became a barrier to the getting of an adequate knowledge of the needs of the slave. The feeling grew that if the shackles of slavery were broken, the Negro would at once be as other men. The economic differences finally led to the war. It is not to be forgotten that slavery itself was not the cause of the war, nor was there any thought on the part of the Union leaders to make the blacks citizens. That this was done later was a glowing tribute to their ignorance of the real demands of the situation. The Republican party of to-day shows no indication of repeating this mistake in the newly acquired islands. I would not be understood as opposing suffrage of the blacks, but any thoughtful observer must agree that as a race they were not prepared for popular government at the time of their liberation. The folly of the measures adopted none can fail to see who will read the history of South Carolina or Mississippi during what is called "Reconstruction."

[Pg 6]Immediately after the war, new sources of information regarding the Negro were afforded the North. The leaders of the carpet-bag regime, playing political games, circulated glowing reports of the progress of the ex-slaves. A second class of persons, the teachers, went South, and back came rose-colored accounts. It might seem that the teacher could best judge of the capacity of a people. The trouble is that in the schools they saw the best specimens of the race, at the impressionable period of their lives, and under abnormal conditions. There is in the school an atmosphere about the child which stimulates his desire to advance, but a relapse often comes when ordinary home conditions are renewed. Moreover, it is well known that the children of all primitive races are very quick and apt up to a certain period in their lives, excelling often children of civilized peoples, but that this disappears when maturity is reached. Hence, the average teacher, not coming in close contact with the mass of the people under normal surroundings, gives, although sincerely, a very misleading picture of actual conditions. A third class of informants were the tourists, and their ability to get at the heart of the situation is obvious. There remain to be mentioned the Negro teachers and school entrepreneurs. Naturally these have presented such facts as they thought would serve to open the purses of their hearers. Some have been honest, many more unintentionally dishonest, and others deliberately deceitful. The relative size of these classes it is unnecessary to attempt to ascertain. They have talked and sung their way into the hearts of the hearers as does the pitiful beggar on the street. The donor sees that evidently something is needed, and gives with little, if any, careful investigation as to the real needs of the case. The result of it all has been that the testimony of those who knew far more than was possible for any outsider, the southern whites, has gone unheeded, not to say that it has been spurned as hostile and valueless. The blame, of course, is not always on one side, and as will be shown later, there are many southern whites who have as little to do with the Negro, and consequently know as little about him, as the average New Yorker. This situation has been most unfortunate for all concerned. It should not be forgotten that the question of the progress of the Negro has far more direct meaning for the southerner, and that he is far more deeply interested in it than is his northern brother, the popular impression to the contrary notwithstanding. It is unnecessary to seek explanations, but it is a pleasure to recognize that there are many indications that a better day is coming, and indications now point to a hearty co-operation in educational efforts. There are many reasons for the change, and perhaps the greatest of these is summed up in "Industrial Training."

The North is slowly learning that the Negro is not a dark-skinned Yankee, and that thousands of generations in Africa have produced a being very different from him whose ancestors[Pg 7] lived an equal time in Europe. In a word, we now see that slavery does not account for all the differences between the blacks and whites, and that their origins lie farther back. Our acquaintance with the ancestors of the Negro is meager. We do not even know how many of the numerous African tribes are represented in our midst. A good deal of Semitic blood had already been infused into the more northern tribes. What influence did this have and how many descendants of these tribes are there in America? Tribal distinctions have been hopelessly lost in this country, and the blending has gone on so continuously that perhaps there would be little practical benefit if the stocks could be determined to-day. It is, however, a curious commentary on the turn discussions of the question have taken, that not until 1902 did any one find it advisable to publish a comprehensive study of the African environment and to trace its influence on subsequent development. Yet this is one of the fundamental preliminaries to any real knowledge of the subject.

In close connection with the preceding is the question of the mulatto. Besides the blending of African stocks there has been a good deal of intermixture of white blood. We do not even know how many full blooded Africans there are in America, nor does the last census seek to ascertain. Mulattoes have almost entirely been the offspring of white fathers and black mothers, and probably most of the fathers have been boys and young men. Without attempting a discussion of this subject, whose results ethnologists cannot yet tell, it is certain that a half breed is not a full blood, a mulatto is not a Negro, in spite of the social classification to the contrary. The general belief is that the mulatto is superior, either for good or bad, to the pure Negro. The visitor to the South cannot fail to be struck with the fact that with rare exceptions the colored men in places of responsibility, in education or in business, are evidently not pure negroes. Even in slavery times, the mulattoes were preferred for certain positions, such as overseers, the blacks as field hands. Attention is called to this merely to show our ignorance of an important point. Some may claim that it is a matter of no consequence. This I cannot admit. To me it seems of some significance to know whether mulattoes (and other crosses) form more than their relative percentage of the graduates of the higher schools; whether they are succeeding in business better than the blacks; whether town life is proving particularly attractive to them; whether they have greater or less moral and physical stamina, than the blacks. The lack of definite knowledge should at least stop the prevalent practice of taking the progress of a band of mulattoes and attempting to estimate that of the Negroes thereby. It may be that some day the mulatto will entirely supplant the black, but there is no immediate probability of this. Until we know the facts, our prophecies are but wild guesses. It should be remembered that a crossing of white and black may show itself in[Pg 8] the yellow negro or the changed head and features, either, or both, as the case may be. A dark skin is, therefore, no sure indication of purity and blood.[1]

It is often taken for granted that the Negro has practically equal opportunities in the various parts of the South, and that a fairly uniform rate of progress may be expected. This assumption rests on an ignorance of the geographical location of the mass of blacks. It will be shown that they are living in several distinct agricultural zones in which success must be sought according to local possibilities. Development always depends upon the environment, and we should expect, therefore, unequal progress for the Negroes. Even the highest fruits of civilization fail if the bases of life are suddenly changed. The Congregational Church has not flourished among the Negroes as have some other denominations, in spite of its great activity in educational work. The American mode of government is being greatly modified to make it fit conditions in Porto Rico. The manufacturers of Pennsylvania and the farmers of Iowa do not agree as to the articles on which duties should be levied, and it is a question if the two have the same interpretation of the principle of protection. Different environments produce different types. So it will be in the case of the Negro. If we are to understand the conditions on which his progress depends, we must pay some attention to economic geography. That this will result in a recognition of the need for shaping plans and methods according to local needs is obvious. The present thesis does not pretend to be a completed study, much less an attempt to solve the Negro problem. It is written in the hope of calling attention to some of the results of this geographic location as illustrated in the situation of the Negro farmer in various parts of the South.

The attempt is made to describe the situation of the average man. It is fully recognized that there are numbers of exceptions among the Negroes as well as among the white school teachers, referred to above. That there is much in the present situation, both of encouragement and discouragement, is patent. Unfortunately, most of us shut our eyes to one or the other set of facts and are wildly optimistic or pessimistic, accordingly. That there may be no misunderstanding of my position, let me say that I agree with the late Dr. J. L. M. Curry in stating that: "I have very little respect for the intelligence or the patriotism of the man who doubts the capacity of the negro for improvement or usefulness."

The great Appalachian system, running parallel to the Atlantic coast, and ending in northern Alabama, forms the geological axis of the southern states. Bordering the mountains proper is a broad belt of hills known as the Piedmont or Metamorphic region, marked by granite and other crystalline rocks, and having an elevation decreasing from 1,000 to 500 feet. The soil varies according to the underlying rocks, but is thin and washes badly, if carelessly tilled. The oaks, hickories and other hardwoods, form the forests. In Virginia this section meets the lower and flatter country known as Tide-Water Virginia. In the southern part of this state we come to the Pine Hills, which follow the Piedmont and stretch, interrupted only by the alluvial lands of the Mississippi, to central Texas. The Pine Hills seldom touch the Piedmont directly, but are separated by a narrow belt of Sand Hills, which run from North Carolina to Alabama, then swing northward around the coal measures and spread out in Tennessee and Kentucky. This region, in general of poor soils, marks the falls of the rivers and the head of navigation. How important this is may easily be seen by noticing the location of the cities in Georgia, for instance, and remembering that the country was settled before the day of railroads. In Alabama the Black Prairie is interposed between the Pine Hills and the Sand Hills, and this prairie swings northward into Mississippi. The Pine Hills give way to the more level Pine Flats, which slope with a gradient of a few feet a mile to the ocean or the gulf, which usually has a narrow alluvial border. Going west from Alabama we cross the oak and hickory lands of Central Mississippi, which are separated from the alluvial district by the cane hills and yellow loam table lands. Beyond the bottom lands of the Mississippi (and Red river) we come to the oak lands of Missouri, Arkansas and Texas which stretch to the black prairies of Texas, which, bordering the red lands of Arkansas, run southwest finally, merging in the coast prairies near Austin. In the northern part of Arkansas we come to the foothills of the Ozarks. These different regions are shown by the dotted lines on the population maps.

The soils of these various regions having never been subjected to a glacial epoch, are very diverse, and it would be a thankless task to attempt any detailed classification on the basis of fertility. The soils of the Atlantic side being largely from the crystalline rocks and containing therefore much silica, are re[Pg 10]puted less fertile than the gulf soils. The alluvial lands of the Mississippi and other rivers are beyond question the richest of all. Shaler says: "The delta districts of the Mississippi and its tributaries and similar alluvial lands which occupy broad fields near the lower portion of other streams flowing into the gulf have proved the most enduringly fertile areas of the country." Next to these probably stand the black prairies. In all states there is more or less alluvial land along the streams, and this soil is always the best. It is the first land brought into cultivation when the country is settled, and remains most constantly in use. Each district has its own advantages and its own difficulties. In the metamorphic regions, the trouble comes in the attempt to keep the soil on the hills, while in the flat lands the problem is to get proper drainage. In the present situation of the Negro farmer the adaptability of the soil to cotton is the chief consideration.

The first slaves were landed at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. The importation was continued in spite of many protests, and the practice soon came into favor. Almost without interruption, in spite of various prohibitions, the slave traffic lasted right up to the very outbreak of the war, most of the later cargoes being landed along the gulf coast. Slavery proved profitable at the South; not so at the North, where it was soon abandoned. It was by no means, however, equally profitable in all parts of the South, and as time went on this fact became more noticeable. Thus at the outbreak of the war, Kentucky and Virginia were largely employed in selling slaves to the large plantations further south. Few new slaves had been imported into Virginia in the last one hundred years. The center of slavery thus moved southwest because of changing economic conditions, not because of any inherent opposition to the system. This gradual weeding out of the slaves in Virginia may very possibly account for the general esteem in which Virginia negroes have been held. To indicate the character of those sold South, Bracket[2] gives a quotation from a Baltimore paper of 1851 which advertised some good Negroes to be "exchanged for servants suitable for the South with bad characters."

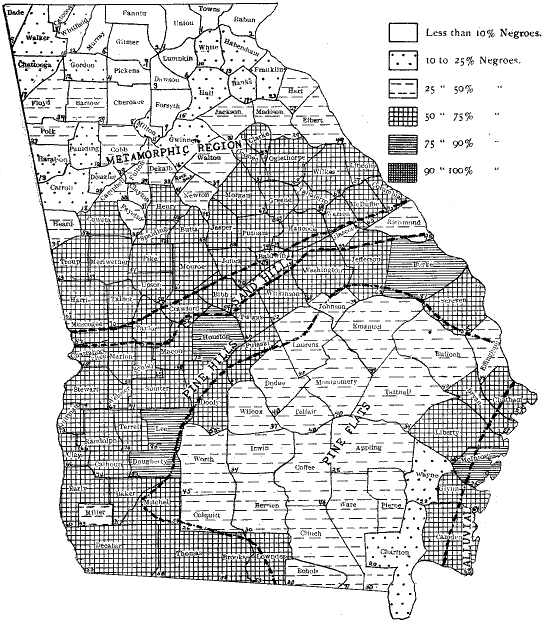

To trace the development of the slave-holding districts is not germain to the present study, interesting as it is in itself. It may be worth while to trace the progress in one state. In Georgia, in 1800, the blacks outnumbered the whites in the seacoast counties, excepting Camden, and were also in the majority in Richmond. In 1830 they also outnumbered the whites along the Savannah river and were reaching westward as far as Jones county. In 1850, besides the coast and the river, they were in a majority in a narrow belt crossing the state from Lincoln to Harris counties. By 1860 they had swung southward in the western part of [Pg 11]the state and were in possession of most of the counties south of Troup, while the map of 1900 shows that they have added to this territory. In other parts of the state they have never been greatly in evidence. The influence of the rivers is again evident when we notice that they moved up to the head of navigation, then swung westward.

As slavery developed, it was accompanied by a great extension of cotton growing, or, perhaps, it were truer to say that the gradual rise of cotton planting made possible the increased use of slaves. The center of the cotton industry had reached the middle of Alabama by 1850, was near Jackson, Mississippi, in 1860, and has since moved slowly westward. The most prosperous district of the South in 1860 was probably the alluvial lands of the Mississippi. This gives us the key to the westward trend of slavery. Let it be remembered, too, that the system of slavery demands an abundance of new lands to take the place of those worn out by the short-sighted cultivation adopted. Thus in the South little attention was paid to rotation of crops or to fertilizers. As long as the new land was abundant, it was not considered, and probably was not profitable to keep up the old. The result was that "the wild and reckless system of extensive cultivation practiced prior to the war had impoverished the land of every cotton-producing state east of the Mississippi river." As cotton became less and less profitable in the east the opening up of the newer and richer lands in the west put the eastern planter in a more and more precarious situation. Had cotton fallen to anything like its present price in the years immediately preceding the war, his lot would have been far worse.

Another influence should be noted. Slavery tended to drive out of a community those who opposed the system, and also the poor whites, non-slave holders. The planters sought to buy out or expel this latter class, because of the temptation they were under to incite the slaves to steal corn and cotton and sell it to them at a low price. There was also trouble in many other ways. There was thus a tendency to separate the mass of the blacks from the majority of the whites. That this segregation actually arose a map of the proportionate populations for Alabama in 1860 shows. It may be claimed that there were other reasons for this separation, such as climatic conditions, etc. This may be partially true, but it evidently cannot be the principal reason, for we find the whites in the majority in many of the lowest and theoretically most unhealthful regions, as in the pine flats. This is the situation to-day also.

The influence of the rivers in determining the settlement of the country has been mentioned. Nowhere was this more the case than in the alluvial lands of the Mississippi, the so-called "Delta." This country was low and flat, subject to overflows of the river. The early settlements were directly on the banks of the navigable streams, because this only was accessible, and because[Pg 12] the land immediately bordering the streams is higher than the back land. Levees were at once started to control the rivers, but not until the railroads penetrated the country in 1884 was there any development of the back land. Even to-day most of this is still wild.

The war brought numerous changes, but it is only in place here to consider those affecting the location of the people. The mobility of labor is one of the great changes. Instead of a fixed labor force we now have to deal with a body relatively free to go and come. The immediate result is that a stream of emigration sets in from the border states to the cities of the North, where there was great opportunity for servants and all sorts of casual labor. The following table shows the number of negroes in various northern cities in 1860 and also in 1900:

| 1860. | 1900. | |||

| Washington | 10,983 | 86,702 | ||

| Baltimore | 27,898 | 79,258 | ||

| Philadelphia | 22,185 | 62,613 | ||

| New York | 16,785 | 60,666 | ||

| St. Louis | 3,297 | 35,516 | ||

| Chicago | 955 | 30,150 |

Coincident with the movement to the more distant towns came a development of southern cities. City life has been very attractive to Negroes here also, as the following table indicates:

| 1860. | 1900. | |||

| New Orleans | 24,074 | 77,714 | ||

| Atlanta | 1,939 | 35,727 | ||

| Richmond | 14,275 | 32,230 | ||

| Charleston | 17,146 | 31,522 | ||

| Savannah | 8,417 | 28,090 | ||

| Montgomery | 4,502 | 17,229 | ||

| Birmingham | ... | 16,575 |

Other cities show the same gains. As a rule, the negro has been the common laborer in the cities and in the trades does not seem to hold the same relative position he had in 1860. In recent years there has been quite a development of small tradesmen among them.

A comparison of the two tables shows that Washington and Baltimore have more Negroes than New Orleans; that St. Louis has more than Atlanta and Richmond, while New York and Philadelphia contain double the number of Savannah and Charleston. This emigration to the North has had great effect upon many districts of the South. It seems also to be certain that the Negroes have not maintained themselves in the northern cities, and that the population has been kept up by constant immigration. What this has meant we may see when we find that in 1860 the Negroes were in the majority in five counties in Maryland, in two in 1900; in 43 in Virginia in 1860, in 35 in 1900; in North Carolina in 19 in 1860, in 15 in 1900.

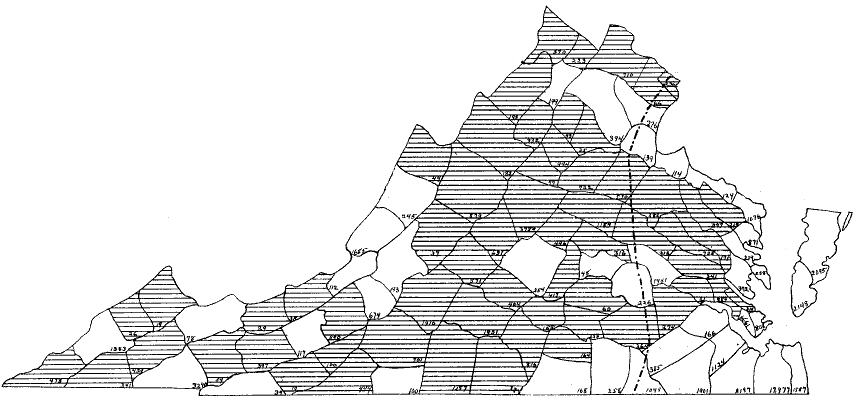

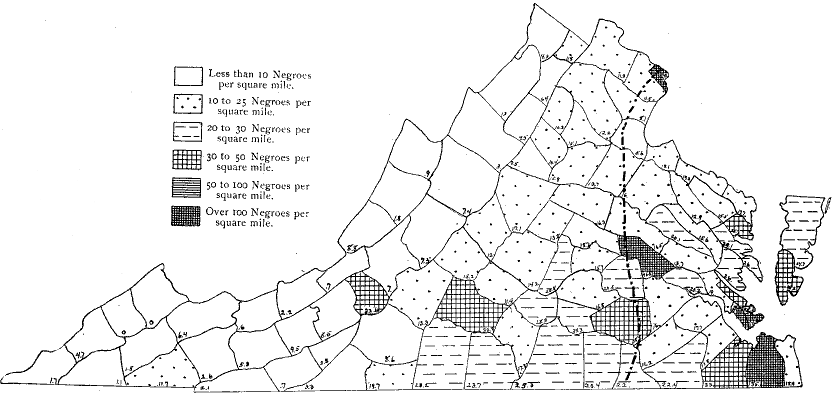

The map on page 13 shows the movement of the Negro population in Virginia between 1890 and 1900. The shaded coun[Pg 14]ties, 60 in number, have lost in actual population (Negro). The total actual decrease in these counties was over 27,000. Even in the towns there has been a loss, for in 1890 the twelve towns of over 2,500 population contained 32,692 Negroes. In 1900 only 29,575. The only section in which there has been a heavy increase is the seacoast from Norfolk and Newport News to the north and including Richmond. A city like Roanoke also makes its presence felt. When we remember that the Negroes in Virginia number over 600,000, and that the total increase in the decade was only 25,000, a heavy emigration becomes clear.

As a common laborer also the negro has borne his part in the development of the economical resources of the South. He has built the railroads and levees; has hewn lumber in the forests; has dug phosphate rock on the coast and coal in the interior. Wherever there has been a development of labor industry calling for unskilled labor he has found a place. All these have combined to turn him from the farm, his original American home. The changing agricultural conditions which have had a similar influence will be discussed later.

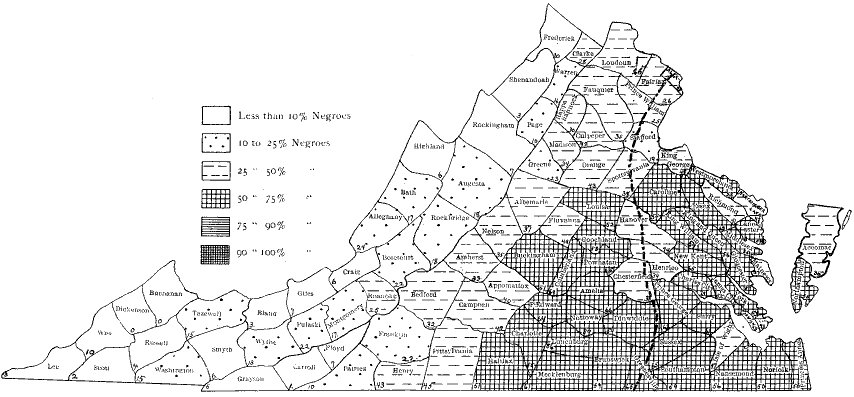

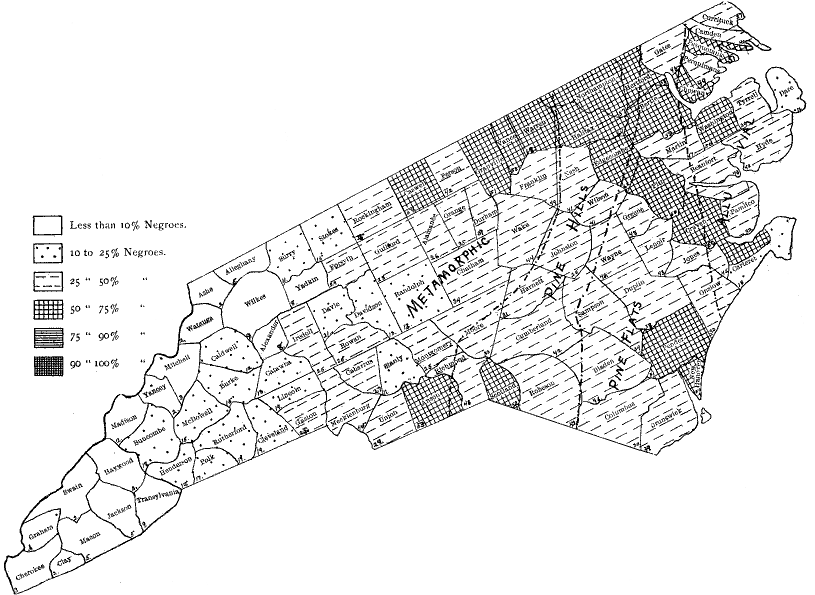

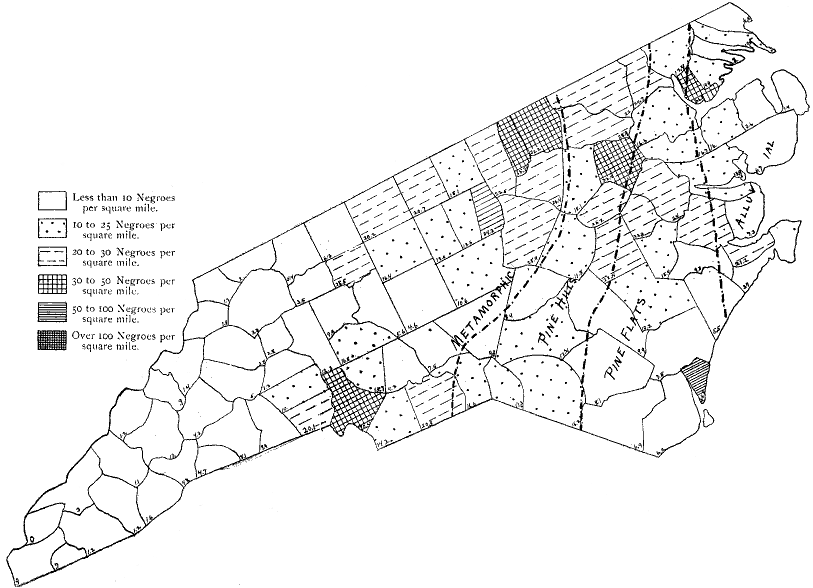

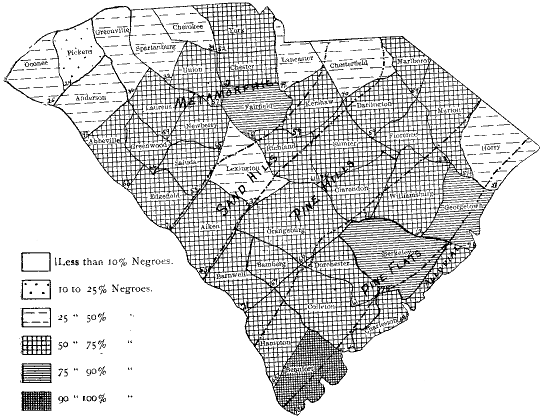

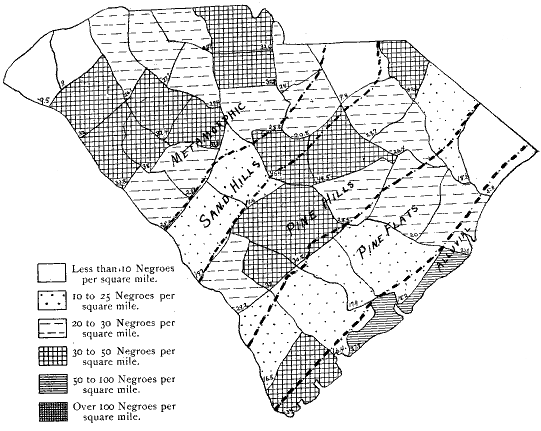

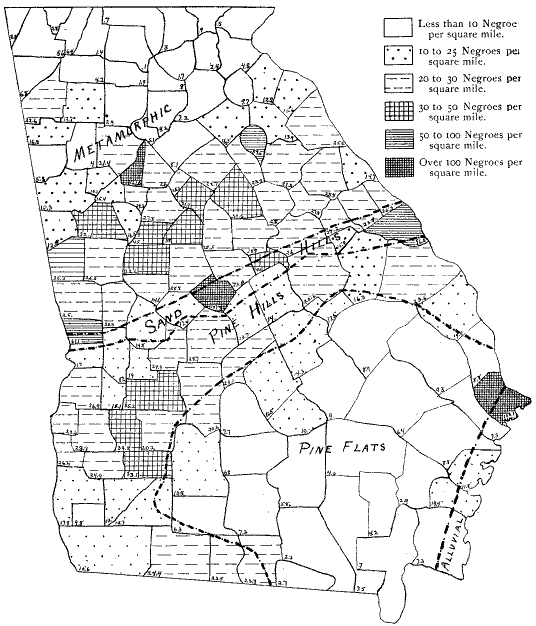

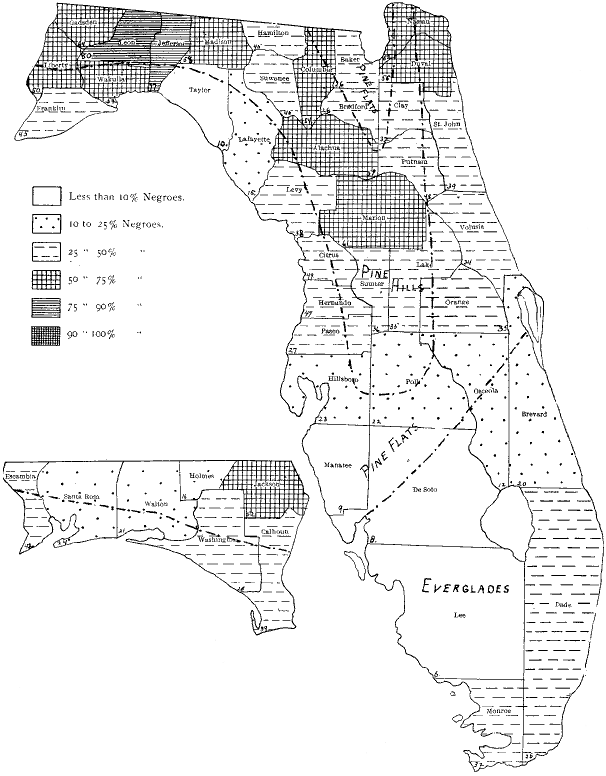

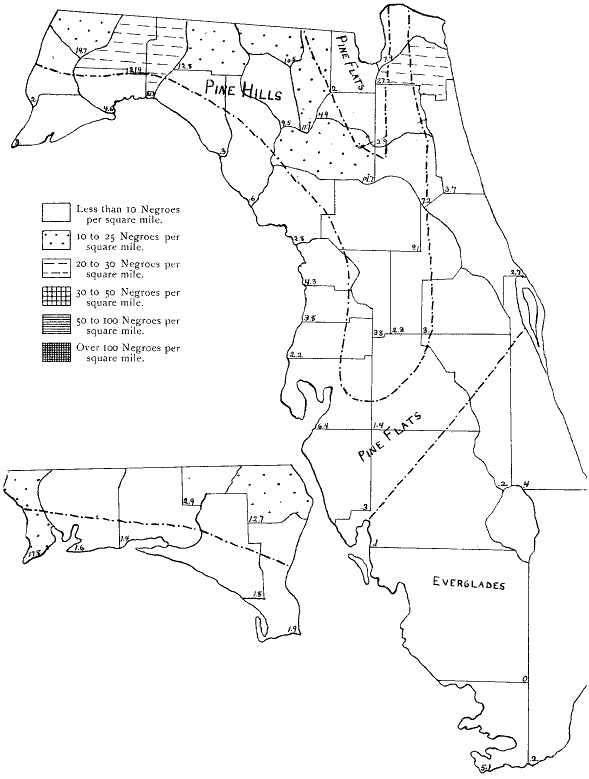

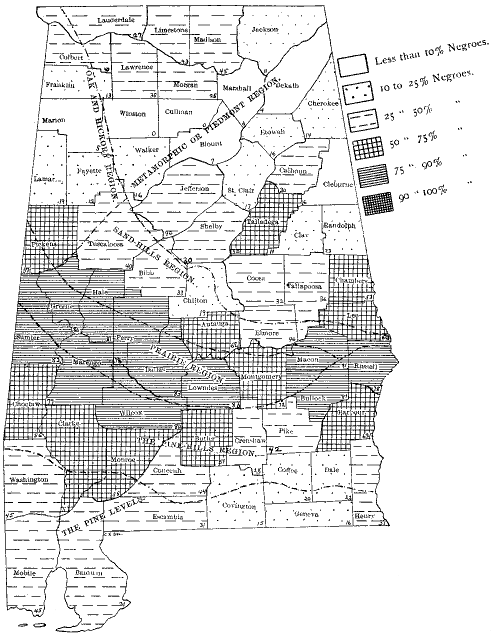

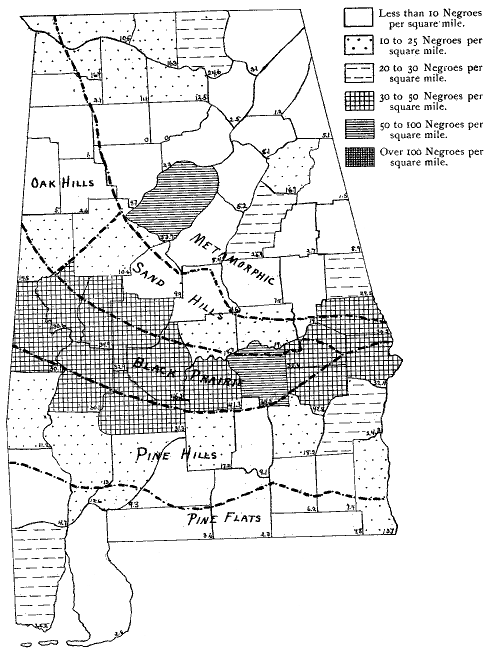

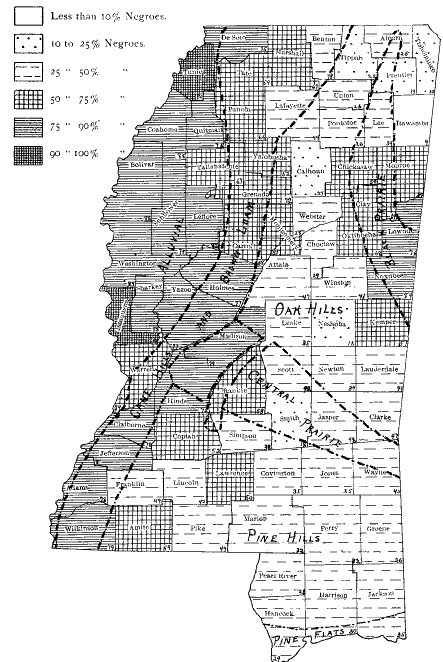

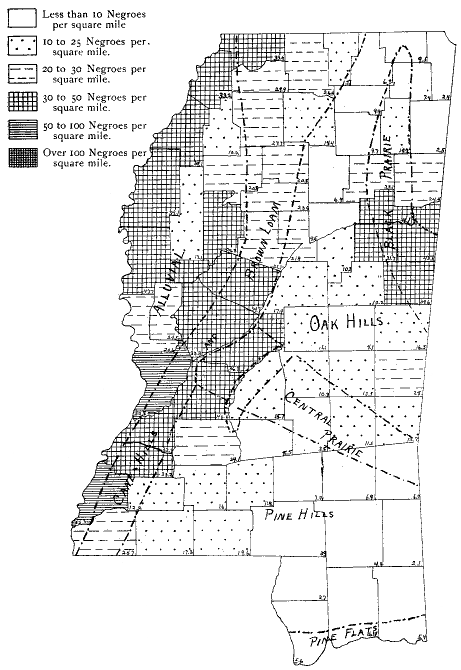

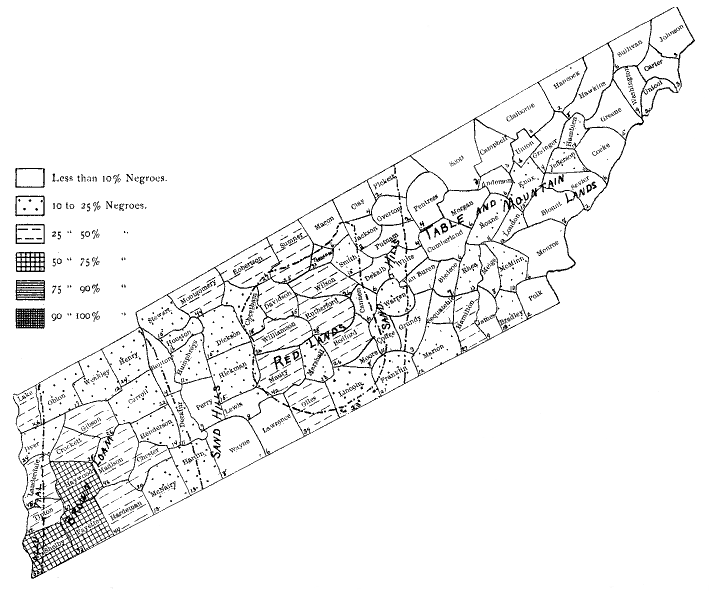

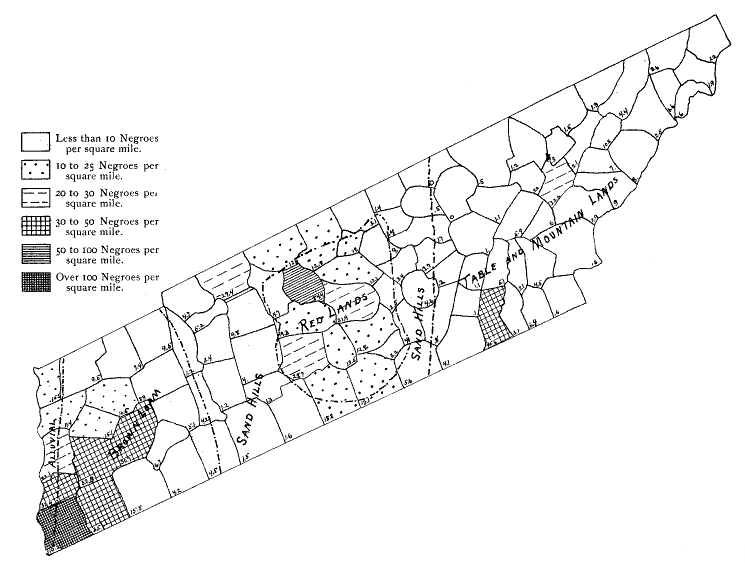

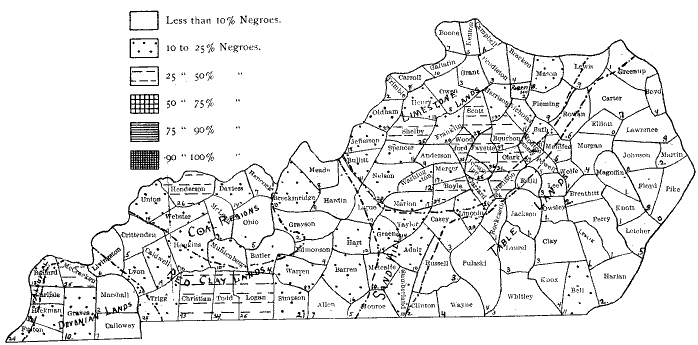

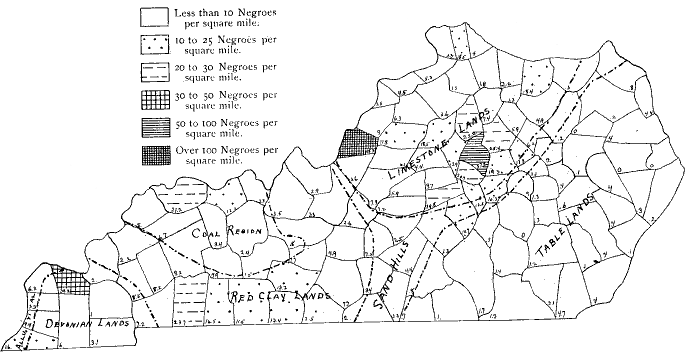

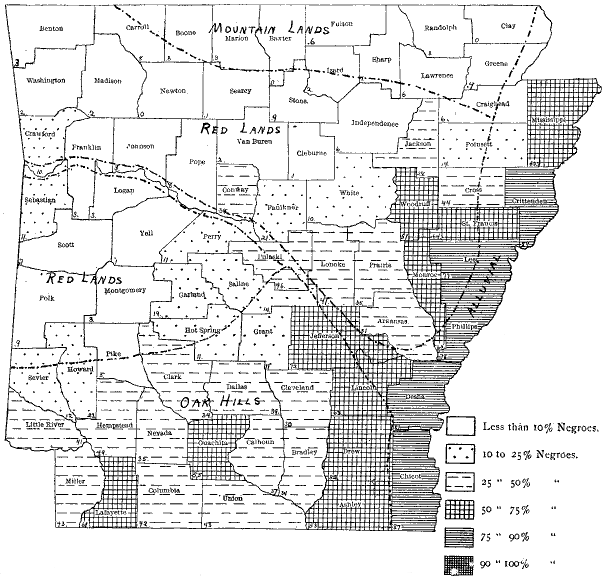

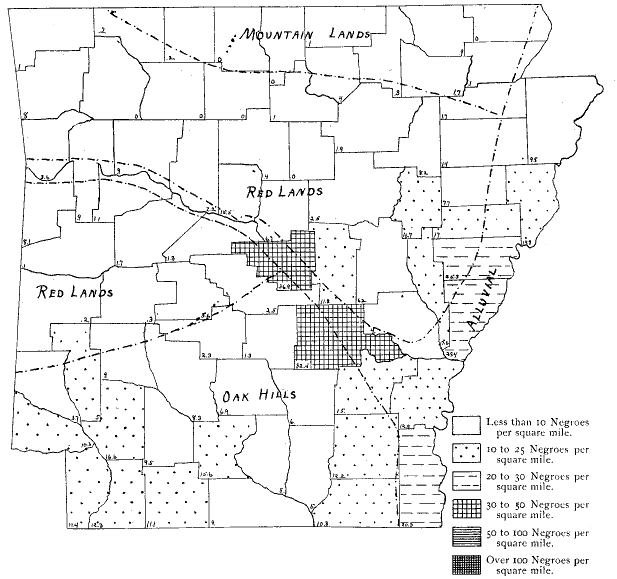

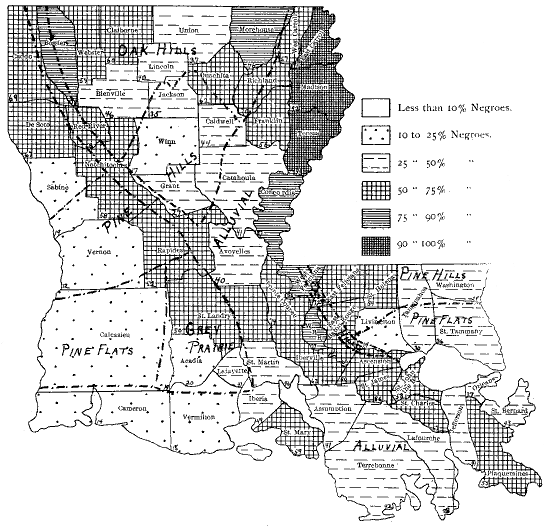

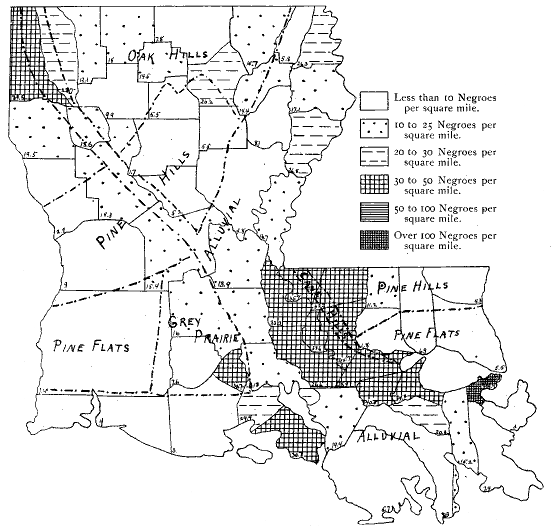

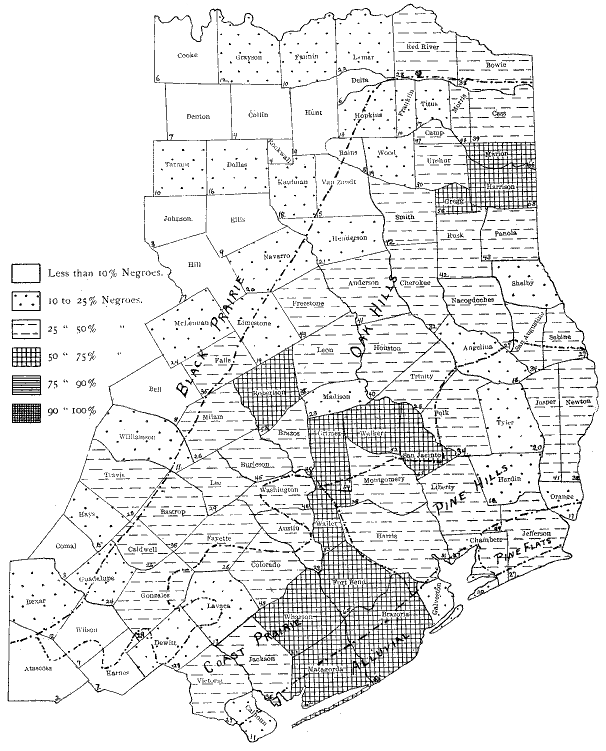

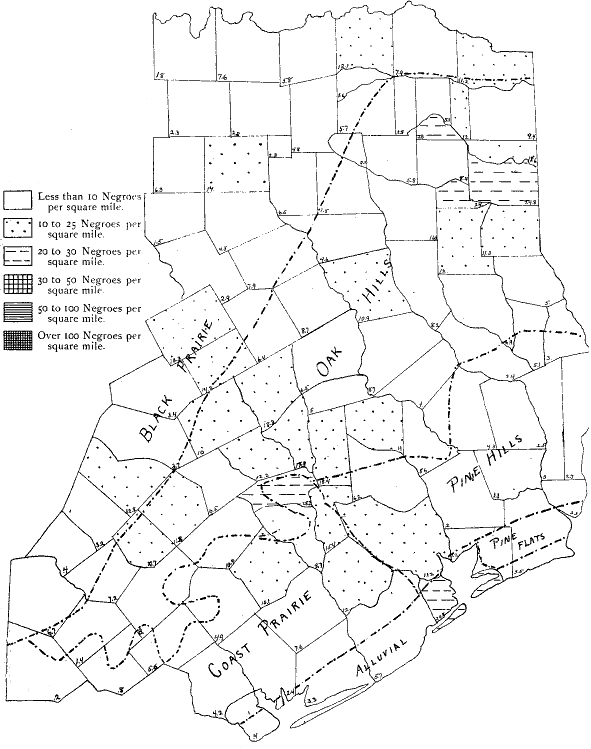

Having thus briefly reviewed the influences which have had part in determining his general habitat we are ready to examine more closely his present location. The maps of the Negro population will show this for the different states. A word regarding these maps. They are drawn on the same scale, and the shading represents the same things for the different states. The density map should always be compared with the proportionate map to get a correct view of the actual situation. If this is not done, confused ideas will result. On the density maps if a county has a much heavier shading than surrounding ones, a city is probably the explanation. The reverse may be true on the proportionate maps where the lighter shading may indicate the presence of numbers of whites in some city, as in Montgomery county, Alabama, or Charleston county, South Carolina.

Beginning with Virginia, we find almost no Negroes in the western mountain districts, but their numbers increase as we approach the coast and their center is in the southeast. The heavy district in North Carolina adjoins that in Virginia, diminishing in the southern part of the state. Entering South Carolina we discover a much heavier population, both actually and relatively. Geographical foundations unfortunately (for our purpose) do not follow county lines. It is very likely, however, that could we get at the actual location of the people, we should find that they had their influence. Evidently the Sand 'Hills have some significance, for the density map shows a lighter negro population. So does the Pine Flats district, although in this state the Negroes are in the majority in the region, having been long settled in the race districts. In no other state do the blacks outnumber the whites in the Pine Flats. In Georgia the northern part is in possession of the whites, as are the Pine Flats. The[Pg 15] Negroes hold the center and the coast. In Florida the Negroes are in the Pine Hills. In Alabama they center in the Pine Hills and Black Prairie. In Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana they are in the alluvial regions, and in Texas they find their heaviest seat near Houston. Outside of the city counties we do not find a population of over 30 negroes to the square mile until South Carolina is reached, and the heaviest settlement is in the black prairie of Alabama and the alluvial region of Mississippi, and part of Louisiana. In Tennessee they are found along the river and in the red lands of the center, while in Kentucky they are chiefly located in the Limestone district. Summarizing their location, we may say that they start in the east-central portion of Virginia and follow the line of the Pine Hills to Alabama, only slightly encroaching upon the Metamorphic district, and except in South Carolina, on the pine flats. They occupy the black prairie of Alabama and Mississippi, and the lands of the river states with a smaller population in the Oak Hills of Texas, the red lands of Tennessee and some of the limestone district of Kentucky. It is worth while to examine one state more in detail and Alabama has been selected as being typical. The Negro proportion in the state in 1860 was 45.4 per cent, and in 1900 was 45.2 per cent.

An examination of a proportionate map for 1860 would show that the slave owners found two parts of the state favorable to them. The first is along the Tennessee river in the North, and the second, the black prairie of the center. Of these the latter was by far the seat of the heavier population. It has already been suggested that this was probably the best land in the slave states, save the alluvial bottoms. Both districts were accessible by water. The Tombigbee and Alabama rivers reached all parts of the prairie, the Tennessee forming the natural outlet of the North. By referring now to the map of 1900, it is evident that some changes have taken place. The prairie country, the "Black Belt," is still in the possession of the Negroes, and their percentage is larger, having increased from 71 to 80. The population per square mile is also heavier. Dallas, Sumter and Lowndes counties had a Negro population of 23.6 per square mile in 1860, and 39.2 in 1900. In the northern district an opposite condition exists. In 1860 the region embracing the counties of Lauderdale, Limestone, Franklin, Colbert, Lawrence and Morgan had a colored population forming 44.5 per cent of the total. In 1900 the Negroes were but 33 per cent of the total. The district contains some 4,609 square miles, and had in 1860 a Negro population of 11 to the square mile; in 1900, 13.5. Of this increase of 2.5 per mile, about one-half is found to be in the four towns of the district whose population is over 2,500 each. The smaller villages would probably account for most of the balance, so it seems safe to say that the farming population has scarcely increased in the last forty years. Meantime the whites in the district have increased[Pg 16] from 12 per square mile to 25.4. The census shows that between 1890 and 1900 six counties of North Alabama lost in the actual Negro population, and two others were stationary, while in the black belt the whites decreased in four counties and were stationary in two. It will be seen that the Negroes have gained in Jefferson (Birmingham) and Talladega counties. The opportunities for unskilled labor account largely for this, and Talladega is also a good cotton county. In Winston and Cullman counties there are practically no Negroes, the census showing but 28 in the two. In 1860 they formed 3 per cent of the total in Winston and 6 percent in Blount, which at that time included Cullman. The explanation of their disappearance is found in the fact that since the war these counties have been settled by Germans from about Cincinnati, and the Negroes have found it convenient to move. Roughly speaking, the poor land of the Sand Hills separates the white farmers from the colored. From 1890 to 1900 the Negroes lost relatively in the Metamorphic and Sand Hills, were about stationary in the Prairie, from which they have overflowed and gained in the Oak Hills, and more heavily in the Pine Hills. This statement is based on an examination of five or six counties, lying almost wholly within each of the districts, and which, so far as known, were not affected by the development of any special industry. The period is too short to do more than indicate that the separation of the two races seems to be still going on. A similar separation exists in Mississippi, where the Negroes hold the Black Prairie and the Delta, the whites the hill country of the center.

It is evident that there is a segregation of the whites and blacks, and that there are forces which tend to perpetuate and increase this. It is interesting to note that whereas in slavery the cabins were grouped in the "quarters," in close proximity to the "big house" of the master, they are now scattered about the plantation so that even here there is less contact. In the cities this separation is evident the blacks occupy definite districts, while the social separation is complete. It seems that in all matters outside of business relations the whites have less and less to do with the blacks. If this division is to continue, we may well ask what is its significance for the future.

This geographical segregation evidently had causes which were largely economic. Probably the most potent factor to-day in perpetuating it is social, i. e., race antagonism. The whites do not like to settle in a region where they are to compete with the Negro on the farms as ordinary field hands. Moreover, the Negroes retain their old-time scorn of such whites and despise them. The result is friction. Mr. A. H. Stone cites a case in point. He is speaking of a Negro serving a sentence for attempted rape: "I was anxious to know how, if at all, he accounted for his crime, but he was reluctant to discuss it. Finally he said to me: 'You don't understand—things over here are so differ[Pg 17]ent. I hired to an old man over there by the year. He had only about forty acres of land, and he and his old folks did all their own work—cooking, washing and everything. I was the only outside hand he had. His daughter worked right alongside of me in the field every day for three or four months. Finally, one day, when no one else was round, hell got into me, and I tried to rape her. But you folks over there can't understand—things are so different. Over here a nigger is a nigger, and a white man is a white man, and it's the same with the women.' ... Her only crime was a poverty which compelled her to do work which, in the estimation of the Negro, was reserved as the natural portion of his own race, and the doing of which destroyed the relation which otherwise constituted a barrier to his brutality."[3]

Mr. Stone has touched upon one of the most delicate questions in the relationship of the races. It would be out of place to discuss it here, but attention must be called to the fact that there is the least of such trouble in the districts where the Negro forms the largest percentage of the population. I would not be so foolish as to say that assaults upon white women may not take place anywhere, but as a matter of fact they seem to occur chiefly in those regions where white and black meet as competitors for ordinary labor. Beaufort County, South Carolina, has a black population forming about 90 per cent of the total, yet I was told last summer that but one case of rape had been known in the county, and that took place on the back edge of the county where there are fewest Negroes, and was committed by a non-resident black upon a non-resident white. Certain it is that in this county, which includes many islands, almost wholly inhabited by blacks, the white women have no fear of such assaults. This is also the case in the Mississippi Delta. Mr. Stone says: "Yet here we hear nothing about an ignorant mass of Negroes dragging the white man down; we hear of no black incubus; we have few midnight assassinations and fewer lynchings. The violation by a Negro of the person of a white woman is with us an unknown crime; nowhere is the line marking the social separation of the races more rigidly drawn, nowhere are the relations between the races more kindly. With us race riots are unknown, and we have but one Negro problem—though that constantly confronts us—how to secure more Negroes." Evidently when we hear reports of states of siege and rumors of race war, we are not to understand that this is the normal, typical condition of the entire South. If this is the real situation, it seems clear that the geographical segregation plays no mean part in determining the relation of the two races. It is safe to say that there is a different feeling between the races in the districts where the white is known only as the leader and those in which he comes into competition with the black. What is the significance of this for the future?

[Pg 18]The same condition exists in the cities, and of this Professor Dubois has taken note: "Savannah is an old city where the class of masters among the whites and of trained and confidential slaves among the Negroes formed an exceptionally large part of the population. The result has been unusual good feeling between the races, and the entrance of Negroes into all walks of industrial life, with little or no opposition." "Atlanta, on the other hand, is quite opposite in character. Here the poor whites from North Georgia who neither owned slaves nor had any acquaintance with Negro character, have come into contact and severe competition with the blacks. The result has been intense race feeling."[4] In one of the large towns of the Delta last summer, a prosperous Negro merchant said to me, in discussing the comparative opportunities of different sections: "I would not be allowed to have a store on the main street in such a good location in many places." Yet, his store is patronized by whites; and this would be true in many towns in the black belt. Other evidences of the difference in feeling towards the Negroes is afforded by the epithets of "hill-billies" and "red-necks" applied to the whites of the hill country by the lowland planters, and the retaliatory compliments "yellow-bellies" and "nigger-lovers." Does this geographical segregation help to explain the strikingly diverse reports coming from various parts of the South regarding the Negro? Why does Dr. Paul Barringer, of Virginia, find that race antagonism is rapidly growing, while Mr. Stone of Mississippi, says that their problem is to get more Negroes?

The influence that this segregation has upon school facilities for both races should not be overlooked. The separation of the two races in the schools is to be viewed as the settled policy of the South. Here, then, is a farming community in which there are only a few Negroes. What sort of a separate school will be maintained for their children? Probably they are unable to support a good school, even should they so desire. The opportunities of their children must necessarily be limited. Will they make greater progress than children in the districts where the blacks are in large numbers and command good schools? If the situation be reversed and there are a few whites in a black community, the whites will be able to command excellent private schools for their children, if necessary. At present among the males over 21, the greatest illiteracy is found in the black counties. This may be accounted for by the presence of the older generation, which had little chance in the schools, and by the fact that perhaps those moving away have been the more progressive. It is a matter of regret that the census does not permit us to ascertain the illiteracy among the children from 10 to 21 years of age, to see if any difference was manifest. It would seem, however, that this segregation, coupled with race antagonism, is [Pg 19]bound to affect the educational opportunities for the blacks. A problem which becomes more serious as the states waken to the needs of the case and attempt to educate their children.

Yet again, this fact of habitat should lead us to be very chary of making local facts extend over the entire South and of making deductions for the entire country based on observations in a few places. Neglect of this precaution often leads to very erroneous and misleading conceptions of actual conditions. For instance, on page 419, Vol. VI, Census of 1900, in discussing the fact that Negro receives nearly as much per acre for his cotton as does the white, it is stated: "Considering the fact that he emerged from slavery only one-third of a century ago, and considering also his comparative lack of means for procuring the best land or for getting the best results from what he has, this near approach to the standard attained by the white man's experience for more than a century denotes remarkable progress." This may or may not be true, but the reason and proof are open to question. It assumes that the land cultivated by the Negroes is of the same quality as that farmed by the whites. This certainly is not true of Arkansas, of which it is stated that "Arkansas shows a greater production per acre by colored farmers for all three tenures." The three tenures are owners, cash-tenants, share-tenants. Mississippi agrees with Arkansas in showing higher production for both classes of tenants. Are we to infer that the Negroes in Arkansas and Mississippi are better farmers than the whites, and that, therefore, their progress has infinitely surpassed his? By no means. The explanation is that in the two states mentioned the Negroes cultivate the rich bottom land while the white farmers are found in the hills. The alluvial land easily raises twice the cotton, and that of a better quality, commanding about a cent a pound more in the market. There may possibly be similar conditions in other states; certainly in Alabama the black prairie tilled by the Negroes is esteemed better than the other land. Since this was first written I have chanced upon the report of the Geological Survey of Alabama for 1881 and 1882, in which Mr. E. A. Smith sums up this same problem as follows:

"(1) That where the blacks are in excess of the whites, there are the originally most fertile lands of the state. The natural advantages of the soils are, however, more than counterbalanced by the bad system prevailing in such sections, viz.; large farms rented out in patches to laborers who are too poor and too much in debt to merchants to have any interest in keeping up the fertility of the soil, or rather the ability to keep it up, with the natural consequence of its rapid exhaustion, and a product per acre on these, the best lands of the state, lower than that which is realized from the very poorest.

"(2) Where the two races are in nearly equal proportions, or where the whites are in only a slight excess over the blacks, as is the case in all sections where the soils are of average fertility, there is found the system of small farms, worked generally by the owners, a consequently better cultivation, a more general use of commercial fertilizers, a corre[Pg 20]spondingly high product per acre and a partial maintenance of the fertility of the soils.

"(3) Where the whites are greatly in excess of the blacks (three to one and above) the soils are almost certain to be far below the average in fertility, and the product per acre is low from this cause, notwithstanding the redeeming influences of a comparatively rational system of cultivation.

"(4) The exceptions to these general rules are nearly always due to local causes which are not far to seek and which afford generally a satisfactory explanation of the discrepancies."

If we are to base our reasoning on the table cited we might argue that land ownership is a bad thing for Negroes, for tenants of both classes among them produced more than did the owners. The white cash tenants also produced more than white owners. In explaining this it is said: "The fact that cash tenants pay a fixed money rental per acre causes them to rent only such area as they can cultivate thoroughly, while many owners who are unable to rent their excess acreage to tenants attempt to cultivate it themselves, thus decreasing the efficiency of cultivation for the entire farm." This may be true of the whites, but it is a lame explanation for the blacks. Negro farmers who own more land than they can cultivate appear to be better known at Washington than they are locally. The trouble with the entire argument is that it assumes that the Negro is an independent cultivator of cotton. This is not quite the case. In all parts of the South the Negro, tenant or owner, usually receives advances from white factors, and these spend a good part of their time riding about to see that the land is cultivated in order to insure repayment of their loans. If their advice and suggestions are not followed, or if the crop is not cultivated, the supplies are shut off. On many plantations even the portion of the land to be put in cotton is stipulated. The great bulk of the cotton crop is thus raised under the immediate oversight of the white man. There is little call for any great skill on the part of the laborer. No wonder the crop of the Negro approximates that of the white man. It is to be further remembered that cotton raising has been the chief occupation of the Negro in America. The Census gives another illustration of the unhappy effects of attempting to cover very diverse conditions in one statement in the map Vol. VI, plate 3. From this one would be justified in believing that the average farm under one management in the alluvial lands of Mississippi and Louisiana was small. As a matter of fact they are among the largest in the country. The map gives a very misleading conception and it results wholly from attempting to combine divergent conditions.

The quotation from Mr. Smith touched upon another result of this segregation. Where the whites are the farmers the farms are smaller and better cared for, more fertilizers are used, and better results are obtained. The big plantation system has caused the deterioration of naturally fertile soils. Of course, there must come a day of reckoning wherever careless husbandry prevails.

[Pg 21]City conditions are more or less uniform in all sections. The geographical location of the farmer, however, is a matter of considerable importance not only as determining in large measure the crop he must raise, but as limiting the advance he may be able to make under given conditions. It is estimated that about 85 per cent of the men (Negroes) and 44 per cent of the women in productive pursuits are farmers. Their general location has been shown. For convenience we may divide the territory into five districts: (1) Virginia and Kentucky, above the limit of profitable cotton culture. (2) The Atlantic Sea Coast. (3) The Central belt running from Virginia to Central Mississippi. This includes several different soils, but general conditions are fairly uniform. (4) The Alluvial Lands, which may be subdivided into the cotton and cane districts. (5) Texas. These different districts will be treated separately, except Texas, which is not included.

In summing up this chapter it may be said that the location of the mass of the Negro farmers has been indicated, and also the fact that there is a separation between the whites and the blacks which promises to have important bearing on future progress, while the various agricultural districts offer opportunities by no means uniform.

Previous to the appearance of the European, West Central Africa for untold hundreds of years had been almost completely separated from the outside world. The climate is hot, humid, enervating. The Negro tribes living in the great forests found little need for exertion to obtain the necessities of savage life. The woods abounded in game, the rivers in fish. By cutting down a few trees and loosening the ground with sharpened sticks the plantains, a species of coarse banana, could be made to yield many hundred fold. The greater part of the little agricultural work done fell on the women, for it was considered degrading by the men. Handicrafts were almost unknown among many tribes and where they existed were of the simplest. Clothing was of little service. Food preparations were naturally crude. Sanitary restrictions, seemingly so necessary in hot climates, were unheard of. The dead were often buried in the floors of the huts. Miss Kingsley says: "All travelers in West Africa find it necessary very soon to accustom themselves to most noisome odors of many kinds and to all sorts of revolting uncleanliness." Morality, as we use the term, did not exist. Chastity was esteemed in the women only as a marketable commodity. Marriage was easily consummated and with even greater ease dissolved. Slavery, inter-tribal, was widespread, and the ravages of the slave hunter were known long before the arrival of the whites. Religion was a mass of grossest superstitions, with belief in the magical power of witches and sorcerers who had[Pg 23] power of life and death over their fellows. Might was right and the chiefs enforced obedience. It is not necessary to go more into detail. In the words of a recent writer:

"It is clear that any civilization which is based on the fertility of the soil, and not on the energy of man, contains within itself the seed of its own destruction. Where food is easily obtained, where there is little need for clothing or houses, where, in brief, unaided nature furnishes all man's necessities, those elements which produce strength of character and vigor of mind are wanting, and man becomes the slave of his surroundings. He acquires no energy of disposition, he yields himself to superstition and fatalism; the very conditions of life which produced his civilization set the limit of its existence."

It is evident from the foregoing that there had been almost nothing in the conditions of Africa to further habits of thrift and industry. The warm climate made great provision for the future unnecessary, not to say impossible, while social conditions did not favor accumulation of property. It is necessary to emphasize these African conditions, for they have an important influence on future development. Under these conditions Negro character was formed, and that character was not like that of the long-headed blonds of the North.

The transfer to America marked a sharp break with the past. One needs but to stop to enumerate the changes to realize how great this break was. A simple dialect is exchanged for a complex language. A religion whose basic principle is love gradually supplants the fears and superstitions of heathenhood. The black passes from an enervating, humid climate to one in which activity is pleasurable. From the isolation and self-satisfaction of savagery he emerges into close contact with one of the most ambitious and progressive of peoples. Life at once becomes far more secure and wrongs are revenged by the self-interest of the whites as well as by the feeble means of self-defense in possession of the blacks. That there were cruelties and mistreatment under slavery goes without saying, but the woes and sufferings under it were as nothing compared to those of the life in the African forests. This fact is sometimes overlooked. With greater security of life came an emphasis, from without, to be sure, on better marital relations. In this respect slavery left much to be desired, but conditions on the whole were probably in advance of those in Africa. Marriage began to be something more than a purchase. Sanitation, not the word, but the underlying idea, was taught by precept and example. There came also a dim notion of a new sphere for women. Faint perceptions ofttimes, but ideas never dreamed of in Africa. I would not defend slavery, but in this country its evil results are the inheritance of the whites, not of the blacks, and the burden today of American slavery is upon white shoulders.

Many of the changes have been mentioned, but the greatest is reserved for the last. This is embraced in one word—WORK. For the first time the Negro was made to work, not casual work,[Pg 24] but steady, constant labor. From the Negro's standpoint this is the redeeming feature of his slavery as perhaps it was for the Israelites in Egypt of old. Booker Washington has written:[5] "American slavery was a great curse to both races, and I would be the last to apologize for it, but, in the providence of God, I believe that slavery laid the foundation for the solution of the problem that is now before us in the South. During slavery the Negro was taught every trade, every industry, that constitutes the foundation for making a living."

Dr. H. B. Frissell has borne the same testimony:

"The southern plantation was really a great trade school where thousands received instruction in mechanic arts, in agriculture, in cooking, sewing and other domestic occupations. Although it may be said that all this instruction was given from selfish motives, yet the fact remains that the slaves on many plantations had good industrial training, and all honor is due to the conscientious men and still more to the noble women of the South who in slavery times helped to prepare the way for the better days that were to come."

Work is the essential condition of human progress. Contrast the training of the Negro under enforced slavery with that of the Indian, although it should not be thought that the characters were the same, for the life in America had made the Indian one who would not submit to the yoke, and all attempts to enslave him came to naught. Dr. Frissell out of a long experience says:

"When the children of these two races are placed side by side, as they are in the school rooms and workshops and on the farms at Hampton, it is not difficult to perceive that the training which the blacks had under slavery was far more valuable as a preparation for civilized life than the freedom from training and service enjoyed by the Indian on the Western reservations. For while slavery taught the colored man to work, the reservation pauperized the Indian with free rations; while slavery brought the black into the closest relations with the white race and its ways of life, the reservation shut the Indian away from his white brothers and gave him little knowledge of their civilization, language or religion."

The coddled Indian, with all the vices of the white man open to him, has made little, if any, progress, while the Negro, made to work, has held his own in large measure at least.

Under slavery three general fields of service were open to the blacks. The first comprised the domestic and body servants, with the seamstresses, etc., whose labors were in the house or in close personal contact with masters and mistresses. This class was made up of the brightest and quickest, mulattoes being preferred because of their greater aptitude. These servants had almost as much to do with the whites as did the other blacks and absorbed no small amount of learning. Yet the results were not always satisfactory. A southern lady after visiting for a time in New York said on leaving:[6]

"I cannot tell you how much, after being in your house so long, I dread to go home, and have to take care of our servants again. We have a much smaller family of whites than you, but we have twelve servants,[Pg 25] and your two accomplish a great deal more and do their work a great deal better than our twelve. You think your girls are very stupid and that they give much trouble, but it is as nothing. There is hardly one of our servants that can be trusted to do the simplest work without being stood over. If I order a room to be cleaned, or a fire to be made in a distant chamber, I can never be sure I am obeyed unless I go there and see for myself.... And when I reprimand them they only say that they don't mean to do anything wrong, or they won't do it again, all the time laughing as though it were a joke. They don't mind it at all. They are just as playful and careless as any wilful child; and they never will do any work if you don't compel them."

The second class comprised the mechanics, carpenters, blacksmiths, masons and the like. These were also a picked lot. They were well trained ofttimes and had a practical monopoly of their trades in many localities. In technical knowledge they naturally soon outstripped their masters and became conscious of their superiority, as the following instance related by President G. T. Winston shows:

"I remember one day my father, who was a lawyer, offered some suggestions to one of his slaves, a fairly good carpenter, who was building us a barn. The old Negro heard him with ill-concealed disgust, and replied: 'Look here, master, you'se a first-rate lawyer, no doubt, but you don't know nothin' 'tall 'bout carpentering. You better go back to your law books.'"

The training received by these artisans stood them in good stead after the war, when, left to themselves, they were able to hold their ground by virtue of their ability to work alone.

The third class was made up of all that were left, and their work was in the fields. The dullest, as well as those not needed elsewhere, were included. Some few became overseers, but the majority worked on the farms. As a rule little work was required of children under 12, and when they began their tasks were about of the adult's. Thence they passed to "half," "three-quarter" and "full" hands. Olmsted said:[7]

"Until the Negro is big enough for his labor to be plainly profitable to his master he has no training to application or method, but only to idleness and carelessness. Before children arrive at a working age they hardly come under the notice of their owner.... The only whipping of slaves I have seen in Virginia has been of these wild, lazy children, as they are being broke in to work. They cannot be depended upon a minute out of sight. You will see how difficult it would be if it were attempted to eradicate the indolent, careless, incogitant habits so formed in youth. But it is not systematically attempted, and the influences that continue to act upon a slave in the same direction, cultivating every quality at variance with industry, precision, forethought and providence, are innumerable."

In many places the field hands were given set tasks to do each day, and they were then allowed to take their own time and stop when the task was completed. In Georgia and South Carolina the following is cited by Olmsted as tasks for a day:[7]

"In making drains in light clean meadow land each man or woman of the full hands is required to dig one thousand cubic feet; in swamp land[Pg 26] that is being prepared for rice culture, where there are not many stumps, the task for a ditcher is five hundred feet; while in a very strong cypress swamp, only two hundred feet is required; in hoeing rice, a certain number of rows equal to one-half or two-thirds of an acre, according to the condition of the land; in sowing rice (strewing in drills), two acres; in reaping rice (if it stands well), three-quarters of an acre, or, sometimes a gang will be required to reap, tie in sheaves, and carry to the stack yard the produce of a certain area commonly equal to one-fourth the number of acres that there are hands working together; hoeing cotton, corn or potatoes, one-half to one acre; threshing, five to six hundred sheaves. In plowing rice land (light, clean, mellow soil), with a yoke of oxen, one acre a day, including the ground lost in and near the drains, the oxen being changed at noon. A cooper also, for instance, is required to make barrels at the rate of eighteen a week; drawing staves, 500 a day; hoop-poles, 120; squaring timber, 100 feet; laying worm fence, 50 panels per day; post and rail fence, posts set two and a half to three feet deep, nine feet apart, nine or ten panels per hand. In getting fuel from the woods (pine to be cut and split), one cord is the task for a day. In 'mauling rails,' the taskman selecting the trees (pine) that he judges will split easiest, 100 a day, ends not sharpened.

"In allotting the tasks the drivers are expected to put the weaker hands where, if there is any choice in the appearance of the ground, as where certain rows in hoeing corn would be less weedy than others, they will be favored.

"These tasks would certainly not be considered excessively hard by a northern laborer, and, in point of fact, the more industrious and active hands finish them often by two o'clock. I saw one or two leaving the field soon after one o'clock, several about two, and between three and four I met a dozen women and several men coming to their cabins, having finished their day's work.... If, after a hard day's labor he (the driver) sees that the gang has been overtasked, owing to a miscalculation of the difficulty of the work, he may excuse the completion of the tasks, but he is not allowed to extend them."

In other places the work was not laid out in tasks, but it is safe to say that, judging from all reports and all probabilities, the amount of work done did not equal that of the free labor of the North, then or now. If it had the commercial supremacy of the South would have been longer maintained.

Some things regarding the agricultural work at once become prominent. All work was done under the immediate eye of the task master. Thus there was little occasion for the development of any sense of individual responsibility for the work. As a rule the methods adopted were crude. Little machinery was used, and that of the simplest. Hoes, heavy and clumsy, were the common tools. Within a year I have seen grass being mowed with hoes preparatory to putting the ground in cultivation. Even today the Negro has to be trained to use the light, sharp hoe of the North. Corn, cotton and, in a few districts, rice or tobacco were the staple crops, although each plantation raised its own fruit and vegetables, and about the cabins in the quarters were little plots for gardens. The land was cultivated for a time, then abandoned for new, while in most places little attention was paid to rotation of crops or to fertilizers. The result was that large sections of the South had been seriously injured before the war. As some one has said:

[Pg 27]"The destruction of the soils by the methods of cultivation prior to the war was worse than the ravages of the war. The post bellum farmer received as an inheritance large areas of wornout and generally unproductive soils."

Yet all things were the master's. A failure of the crop meant little hunger to the black. Refusal to work could but bring bodily punishment, for the master was seldom of the kind who would take life—a live Negro was worth a good deal more than a dead one. Clothing and shelter were provided, and care in sickness. The master must always furnish tools, land and seed, and see to it that the ground was cultivated. There was thus little necessity for the Negro to care for the morrow, and his African training had not taught him to borrow trouble. Thus neither Africa nor America had trained the Negro to independent, continuous labor apart from the eye of the overseer. The requirements as to skill were low. The average man learned little of the mysteries of fruit growing, truck farming and all the economies which make diversified agriculture profitable.

Freedom came, a second sharp break with the past. There is now no one who is responsible for food and clothing. For a time all is in confusion. The war had wiped out the capital of the country. The whites were land poor, the Negroes landless. It so happened that at this time the price of cotton was high. The Negro knew more about cotton than any other crop. Raise cotton became the order of the day. The money lenders would lend money on cotton, even in advance, for it had a certain and sure ready sale. Thus developed the crop-lien system which in essence consists in taking a mortgage on crops yet to be raised. The system existed among the white planters for many years before the war.

A certain amount of food and clothing was advanced to the Negro family until the crop could be harvested, when the money value of the goods received was returned with interest. Perhaps nothing which concerns the Negro has been the subject of more hostile criticism than this crop-lien system. That it is easily abused when the man on one side is a shrewd and cunning sharpster and the borrower an illiterate and trusting Negro is beyond doubt. That in thousands of cases advantage has been taken of this fact to wrest from the Negro at the end of the year all that he had is not to be questioned. Certainly a system which makes it possible is open to criticism. It should not be forgotten, however, that the system grew out of the needs of the time and served a useful purpose when honestly administered, even as it does today. No money could be gotten with land as security, and even today the land owner often sees his merchant with far less capital get money from the bank which has refused his security. The system has enabled a poor man without tools and work animals without food to get a start and be provided with a modicum of necessities until the crops were[Pg 28] harvested. Thousands have become more or less independent who started in this way. The evil influences of the system, for none would consider it ideal, have probably been that it has made unnecessary any saving on the part of the Negro, who feels sure that he can receive his advances and who cares little for the fact that some day he must pay a big interest on what he receives. Secondly, this system has hindered the development of diversified farming, which today is one of the greatest needs of the South. The advances have been conditioned upon the planting and cultivating a given amount of cotton. During recent years no other staple has so fallen in price, and the result has been hard on the farmers. All else has faded into insignificance before the necessity of raising cotton. The result on the fertility of the soil is also evident. Luckily cotton makes light demands on the land, but the thin soil of many districts has been unable to stand even the light demands. Guano came just in time and the later commercial fertilizers have postponed the evil day. The development of the cotton mills has also served to give a local market, which has stimulated the production of cotton. It seems rather evident, however, that the increasing development of western lands will put a heavier burden upon the Atlantic slope. This, of course, will not affect the culture of sea-island cotton, which is grown in only a limited area. To meet this handicap a more diversified agriculture must gradually supplant in some way the present over-attention to cotton. In early days Virginia raised much cotton, now it stands towards the bottom of the cotton states. Perhaps it is safe to say that Virginia land has been as much injured by the more exhaustive crop, tobacco, as the other states by cotton. Large areas have been allowed to go back to the woods and local conditions have greatly changed. How this diversification is to be brought about for the Negro is one of the most important questions. Recent years have witnessed an enormous development of truck farming, but in this the Negro has borne little part. This intensive farming requires a knowledge of soil and of plant life, coupled with much ability in marketing wares, which the average Negro does not possess. Nor has he taken any great part in the fruit industry, which is steadily growing. The question to which all this leads may be stated as follows. To what extent is the Negro taking advantage of the opportunities he now has on the farm? What is his present situation?

The southern states are not densely populated. Alabama has an average of 35 per square mile; Georgia, 37; South Carolina, 44. These may be compared with Iowa, 40; Indiana, 70, taking two of the typical northern farming states, while Connecticut has 187. In the prairie section of Alabama the Negro population ranges from 30 to 50 per square mile, and this is about the densest outside of the city counties. There is thus an abundance of land. As a matter of fact there is not the least difficulty for the Negro farmer to get plenty of land, and he has but to show himself a good tenant to have the whites offering him inducements.

Negroes on the farms may be divided into four classes: Owners, cash tenants, share tenants, laborers. Share tenants differ from the same class in the North in that work animals and tools[Pg 30] are usually provided by the landlord. Among the laborers must also be included the families living on the rice and cane plantations, who work for cash wages but receive houses and such perquisites as do other tenants and whose permanence is more assured than an ordinary day hand. They are paid in cash, usually through a plantation store, that debts for provisions, etc., may be deducted. Both owners and tenants find it generally necessary to arrange for advances of food and clothing until harvest. The advances begin in the early Spring and continue until August or sometimes until the cotton is picked. In the regions east of the alluvial lands advances usually stop by the first of August, and in the interim until the cotton is sold odd jobs or some extra labor, picking blackberries and the like, must furnish the support for the family. The landlord may do the advancing or some merchant. Money is seldom furnished directly, although in recent years banks are beginning to loan on crop-liens. The food supplied is often based on the number of working hands, irrespective of the number of children in the family. This is occasionally a hardship. The customary ration is a peck of corn meal and three pounds of pork per week. Usually a crop-lien together with a bill of sale of any personal property is given as security, but in some states landlords have a first lien upon all crops for rent and advances. In all districts the tenant is allowed to cut wood for his fire, and frequently has free pasture for his stock. There is much complaint that when there are fences about the house they are sometimes burned, being more accessible than the timber, which may be at a distance and which has to be cut. The landlords and the advancers have found it necessary to spend a large part of their time personally, or through agents called "riders," going about the plantations to see that the crops are cultivated. The Negro knows how to raise cotton, but he may forget to plow, chop, or some other such trifle, unless reminded of the necessity. Thus a considerable part of the excessive interest charged the Negro should really be charged as wages of superintendence. If the instructions of the riders are not followed, rations are cut off, and thus the recalcitrant brought to terms.

For a long time rations have been dealt out on Saturday. So Saturday has come to be considered a holiday, or half-holiday at least. Early in the morning the roads are covered with blacks on foot, horse back, mule back and in various vehicles, on their way to the store or village, there to spend the day loafing about in friendly discussion with neighbors. The condition of the crops has little preventive influence, and the handicap to successful husbandry formed by the habit is easily perceived. Many efforts are being made to break up the custom, but it is up-hill work. Another habit of the Negro which militates against his progress is his prowling about in all sorts of revels by night, thereby unfitting himself for labor the next day. This trait also shows[Pg 31] forth the general thoughtlessness of the Negro. His mule works by day, but is expected to carry his owner any number of miles at night. Sunday is seldom a day of rest for the work animals. It is a curious fact that wherever the Negroes are most numerous there mules usually outnumber horses. There are several reasons for this. It has often been supposed that mules endure the heat better than horses. This is questionable. The mule, however, will do a certain amount and then quit, all inducements to the contrary notwithstanding. The horse will go till he drops; moreover, will not stand the abuse which the mule endures. The Negro does not bear a good reputation for care of his animals. He neglects to feed and provide for them. Their looks justify the criticism. The mule, valuable as he is for many purposes, is necessarily more expensive in the long run than a self-perpetuating animal.

In all parts it is the custom for the Negroes to save a little garden patch about the house, which, if properly tended, would supply the family with vegetables throughout the year. This is seldom the case. A recent Tuskegee catalog commenting on this says:

"If they have any garden at all, it is apt to be choked with weeds and other noxious growths. With every advantage of soil and climate, and with a steady market if they live near any city or large town, few of the colored farmers get any benefit from this, one of the most profitable of all industries."

As a matter of fact they care little for vegetables and seldom know how to prepare them for the table. The garden is regularly started in the Spring, but seldom amounts to much. I have ridden for a day with but a glimpse of a couple of attempts. As a result there will be a few collards, turnips, gourds, sweet potatoes and beans, but the mass of the people buy the little they need from the stores. A dealer in a little country store told me last summer that he would make about $75 an acre on three acres of watermelons, although almost every purchaser could raise them if he would. In many regions wild fruits are abundant, and blackberries during the season are quite a staple, but they are seldom canned. Some cattle are kept, but little butter is made, and milk is seldom on the bill of fare, the stock being sold when fat (?). Many families keep chickens, usually of the variety known as "dunghill fowls," which forage for themselves. But the market supplied with chickens by the small farmers, as it might easily be. Whenever opportunity offers, hunting and fishing become more than diversions, and the fondness for coon and 'possum is proverbial.

In a study of dietaries of Negroes made under Tuskegee Institute and reported in Bulletin No. 38, Office of Experimental Stations, U. S. Dept. of Agriculture, it is stated:

"Comparing these negro dietaries with other dietaries and dietary standards, it will be seen that—

[Pg 32]"(1) The quantities of protein are small. Roughly speaking, the food of these negroes furnished one-third to three-fourths as much protein as are called for in the current physiological standards and as are actually found in the dietaries of well fed whites in the United States and well fed people in Europe. They were, indeed, no larger than have been found in the dietaries of the very poor factory operatives and laborers in Germany and the laborers and beggars in Italy.

"(2) In fuel value the Negro dietaries compare quite favorably with those of well-to-do people of the laboring classes in Europe and the United States."

This indicates the ignorance of the Negro regarding the food he needs, so that in a region of plenty he is underfed as regards the muscle and bone forming elements and overfed so far as fuel value is concerned. One cannot help asking what effect a normal diet would have upon the sexual passions. It is worthy of notice that in the schools maintained by the whites there is relatively little trouble on this account. Possibly the changed life and food are in no small measure responsible for the difference.

Under diversified farming there would be steady employment most of the year, with a corresponding increase of production. As it is there are two busy seasons. In the Spring, planting and cultivating cotton, say from March to July, and in the Fall, cotton picking, September to December. The balance of the time the average farmer does little work. The present system entails a great loss of time.

The absence of good pastures and of meadows is noticeable. This is also too true of white farmers. Yet the grasses grow luxuriantly and nothing but custom or something else accounts for their absence; the something else is cotton. The adaptability of cotton to the Negro is almost providential. It has a long tap root and is able to stand neglect and yet produce a reasonable crop. The grains, corn and cane, with their surface roots, will not thrive under careless handling.

The average farmer knows, or at least utilizes few of the little economies which make agriculture so profitable elsewhere. The Negro is thus under a heavy handicap and does not get the most that he might from present opportunities. I am fully conscious that there are many farmers who take advantage of these things and are correspondingly successful, but they are not the average man of whom I am speaking. With this general statement I pass to a consideration of the situation in the various districts before mentioned.

Tide Water Virginia.

The Virginia sea shore consists of a number of peninsulas separated by narrow rivers (salt water). The country along the shore and the rivers is flat, with low hills in the interior. North of Old Point Comfort the district is scarcely touched by railroads and is accessible only by steamers.

Gloucester County, lying between York River and Mob Jack[Pg 33] Bay, is an interesting region. The hilly soil of the central part sells at from $5 to $10 per acre, while the flat coast land, which is richer although harder to drain, is worth from $25 to $50. The immediate water front has risen in price in recent years and brings fancy prices for residence purposes. Curiously enough some of the best land of the county is that beneath the waters of the rivers—the oyster beds. Land for this use may be worth from nothing to many hundreds of dollars an acre, according to its nature. The county contains 250 square miles, 6,224 whites and 6,608 blacks, the latter forming 51 per cent of the population.

This sea coast region offers peculiar facilities for gaining an easy livelihood. There are few negro families of which some member does not spend part of the year fishing or oystering. There has been a great development of the oyster industry. The season lasts from September 1 to May 1, and good workmen not infrequently make $2 a day or more when they can work on the public beds. This last clause is significant. It is stated that the men expect to work most of September, October and November; one-half of December and January; one-third of February; any time in March is clear gain and all of April. According to a careful study[8] of the oyster industry it was found that the oystermen, i. e., those who dig the oysters from the rocks, make about $8 a month, while families occupied in shucking oysters earn up to $400 a year, three-fourths of them gaining less than $250. The public beds yield less than formerly and the business is gradually going into the hands of firms maintaining their own beds, with a corresponding reduction in possible earnings for the oystermen.

The effect of this industry is twofold; a considerable sum of money is brought into the county and much of this has been invested in homes and small farms. This is the bright side; but there is a dark side. The boys are drawn out of the schools by the age of 12 to work at shucking oysters, and during the winter months near the rivers the boys will attend only on stormy days. The men are also taken away from the farms too early in the fall to gather crops, and return too late in the spring to get the best results from the farm work. The irregular character of the employment reacts on the men and they tend to drift to the cities during the summer, although many find employment in berry picking about Norfolk. Another result has been to make farm labor very scarce. This naturally causes some complaint. I do not say that the bad results outweigh the good, but believe they must be considered.