The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Hated, by Frederik Pohl This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Hated Author: Frederik Pohl Illustrator: Dick Francis Release Date: July 24, 2009 [EBook #29503] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HATED *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

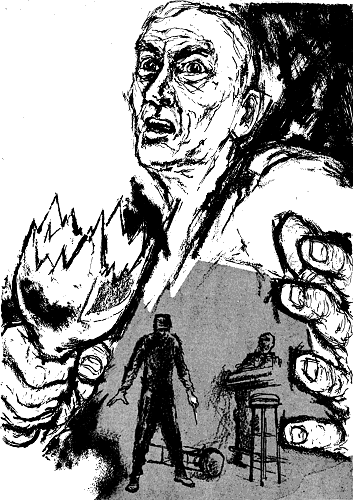

After space, there was always one more river to cross ... the far side of hatred and murder!

Illustrated by DICK FRANCIS

The bar didn't have a name. No name of any kind. Not even an indication that it had ever had one. All it said on the outside was:

Cafe

EAT

Cocktails

which doesn't make a lot of sense. But it was a bar. It had a big TV set going ya-ta-ta ya-ta-ta in three glorious colors, and a jukebox that tried to drown out the TV with that lousy music they play. Anyway, it wasn't a kid hangout. I kind of like it. But I wasn't supposed to be there at all; it's in the contract. I was supposed to stay in New York and the New England states.

Cafe-EAT-Cocktails was right across the river. I think the name of the place was Hoboken, but I'm not sure. It all had a kind of dreamy feeling to it. I was—

Well, I couldn't even remember going there. I remembered one minute I was downtown New York, looking across the river. I did that a lot. And then I was there. I don't remember crossing the river at all.

I was drunk, you know.

You know how it is? Double bourbons and keep them coming. And after a while the bartender stops bringing me the ginger ale because gradually I forget to mix them. I got pretty loaded long before I left New York. I realize that. I guess I had to get pretty loaded to risk the pension and all.

Used to be I didn't drink much, but now, I don't know, when I have one drink, I get to thinking about Sam and Wally and Chowderhead and Gilvey and the captain. If I don't drink, I think about them, too, and then I take a drink. And that leads to another drink, and it all comes out to the same thing. Well, I guess I said it already, I drink a pretty good amount, but you can't blame me.

There was a girl.

I always get a girl someplace. Usually they aren't much and this one wasn't either. I mean she was probably somebody's mother. She was around thirty-five and not so bad, though she had a long scar under her ear down along her throat to the little round spot where her larynx was. It wasn't ugly. She smelled nice—while I could still smell, you know—and she didn't talk much. I liked that. Only—

Well, did you ever meet somebody with a nervous cough? Like when you say something funny—a little funny, not a big yock—they don't laugh and they don't stop with just smiling, but they sort of cough? She did that. I began to itch. I couldn't help it. I asked her to stop it.

She spilled her drink and looked at me almost as though she was scared—and I had tried to say it quietly, too.

"Sorry," she said, a little angry, a little scared. "Sorry. But you don't have to—"

"Forget it."

"Sure. But you asked me to sit down here with you, remember? If you're going to—"

"Forget it!" I nodded at the bartender and held up two fingers. "You need another drink," I said. "The thing is," I said, "Gilvey used to do that."

"What?"

"That cough."

She looked puzzled. "You mean like this?"

"Goddam it, stop it!" Even the bartender looked over at me that time. Now she was really mad, but I didn't want her to go away. I said, "Gilvey was a fellow who went to Mars with me. Pat Gilvey."

"Oh." She sat down again and leaned across the table, low. "Mars."

The bartender brought our drinks and looked at me suspiciously. I said, "Say, Mac, would you turn down the air-conditioning?"

"My name isn't Mac. No."

"Have a heart. It's too cold in here."

"Sorry." He didn't sound sorry.

I was cold. I mean that kind of weather, it's always cold in those places. You know around New York in August? It hits eighty, eighty-five, ninety. All the places have air-conditioning and what they really want is for you to wear a shirt and tie.

But I like to walk a lot. You would, too, you know. And you can't walk around much in long pants and a suit coat and all that stuff. Not around there. Not in August. And so then, when I went into a bar, it'd have one of those built-in freezers for the used-car salesmen with their dates, or maybe their wives, all dressed up. For what? But I froze.

"Mars," the girl breathed. "Mars."

I began to itch again. "Want to dance?"

"They don't have a license," she said. "Byron, I didn't know you'd been to Mars! Please tell me about it."

"It was all right," I said.

That was a lie.

She was interested. She forgot to smile. It made her look nicer. She said, "I knew a man—my brother-in-law—he was my husband's brother—I mean my ex-husband—"

"I get the idea."

"He worked for General Atomic. In Rockford, Illinois. You know where that is?"

"Sure." I couldn't go there, but I knew where Illinois was.

"He worked on the first Mars ship. Oh, fifteen years ago, wasn't it? He always wanted to go himself, but he couldn't pass the tests." She stopped and looked at me.

I knew what she was thinking. But I didn't always look this way, you know. Not that there's anything wrong with me now, I mean, but I couldn't pass the tests any more. Nobody can. That's why we're all one-trippers.

I said, "The only reason I'm shaking like this is because I'm cold."

It wasn't true, of course. It was that cough of Gilvey's. I didn't like to think about Gilvey, or Sam or Chowderhead or Wally or the captain. I didn't like to think about any of them. It made me shake.

You see, we couldn't kill each other. They wouldn't let us do that. Before we took off, they did something to our minds to make sure. What they did, it doesn't last forever. It lasts for two years and then it wears off. That's long enough, you see, because that gets you to Mars and back; and it's plenty long enough, in another way, because it's like a strait-jacket.

You know how to make a baby cry? Hold his hands. It's the most basic thing there is. What they did to us so we couldn't kill each other, it was like being tied up, like having our hands held so we couldn't get free. Well. But two years was long enough. Too long.

The bartender came over and said, "Pal, I'm sorry. See, I turned the air-conditioning down. You all right? You look so—"

I said, "Sure, I'm all right."

He sounded worried. I hadn't even heard him come back. The girl was looking worried, too, I guess because I was shaking so hard I was spilling my drink. I put some money on the table without even counting it.

"It's all right," I said. "We were just going."

"We were?" She looked confused. But she came along with me. They always do, once they find out you've been to Mars.

In the next place, she said, between trips to the powder room, "It must take a lot of courage to sign up for something like that. Were you scientifically inclined in school? Don't you have to know an awful lot to be a space-flyer? Did you ever see any of those little monkey characters they say live on Mars? I read an article about how they lived in little cities of pup-tents or something like that—only they didn't make them, they grew them. Funny! Ever see those? That trip must have been a real drag, I bet. What is it, nine months? You couldn't have a baby! Excuse me— Say, tell me. All that time, how'd you—well, manage things? I mean didn't you ever have to go to the you-know or anything?"

"We managed," I said.

She giggled, and that reminded her, so she went to the powder room again. I thought about getting up and leaving while she was gone, but what was the use of that? I'd only pick up somebody else.

It was nearly midnight. A couple of minutes wouldn't hurt. I reached in my pocket for the little box of pills they give us—it isn't refillable, but we get a new prescription in the mail every month, along with the pension check. The label on the box said:

CAUTION

Use only as directed by physician. Not to be taken by persons suffering heart condition, digestive upset or circulatory disease. Not to be used in conjunction with alcoholic beverages.

I took three of them. I don't like to start them before midnight, but anyway I stopped shaking.

I closed my eyes, and then I was on the ship again. The noise in the bar became the noise of the rockets and the air washers and the sludge sluicers. I began to sweat, although this place was air-conditioned, too.

I could hear Wally whistling to himself the way he did, the sound muffled by his oxygen mask and drowned in the rocket noise, but still perfectly audible. The tune was Sophisticated Lady. Sometimes it was Easy to Love and sometimes Chasing Shadows, but mostly Sophisticated Lady. He was from Juilliard.

Somebody sneezed, and it sounded just like Chowderhead sneezing. You know how everybody sneezes according to his own individual style? Chowderhead had a ladylike little sneeze; it went hutta, real quick, all through the mouth, no nose involved. The captain went Hrasssh; Wally was Ashoo, ashoo, ashoo. Gilvey was Hutch-uh. Sam didn't sneeze much, but he sort of coughed and sprayed, and that was worse.

Sometimes I used to think about killing Sam by tying him down and having Wally and the captain sneeze him to death. But that was a kind of a joke, naturally, when I was feeling good. Or pretty good. Usually I thought about a knife for Sam. For Chowderhead it was a gun, right in the belly, one shot. For Wally it was a tommy gun—just stitching him up and down, you know, back and forth. The captain I would put in a cage with hungry lions, and Gilvey I'd strangle with my bare hands. That was probably because of the cough, I guess.

She was back. "Please tell me about it," she begged. "I'm so curious."

I opened my eyes. "You want me to tell you about it?"

"Oh, please!"

"About what it's like to fly to Mars on a rocket?"

"Yes!"

"All right," I said.

It's wonderful what three little white pills will do. I wasn't even shaking.

"There's six men, see? In a space the size of a Buick, and that's all the room there is. Two of us in the bunks all the time, four of us on watch. Maybe you want to stay in the sack an extra ten minutes—because it's the only place on the ship where you can stretch out, you know, the only place where you can rest without somebody's elbow in your side. But you can't. Because by then it's the next man's turn.

"And maybe you don't have elbows in your side while it's your turn off watch, but in the starboard bunk there's the air-regenerator master valve—I bet I could still show you the bruises right around my kidneys—and in the port bunk there's the emergency-escape-hatch handle. That gets you right in the temple, if you turn your head too fast.

"And you can't really sleep, I mean not soundly, because of the noise. That is, when the rockets are going. When they aren't going, then you're in free-fall, and that's bad, too, because you dream about falling. But when they're going, I don't know, I think it's worse. It's pretty loud.

"And even if it weren't for the noise, if you sleep too soundly you might roll over on your oxygen line. Then you dream about drowning. Ever do that? You're strangling and choking and you can't get any air? It isn't dangerous, I guess. Anyway, it always woke me up in time. Though I heard about a fellow in a flight six years ago—

"Well. So you've always got this oxygen mask on, all the time, except if you take it off for a second to talk to somebody. You don't do that very often, because what is there to say? Oh, maybe the first couple of weeks, sure—everybody's friends then. You don't even need the mask, for that matter. Or not very much. Everybody's still pretty clean. The place smells—oh, let's see—about like the locker room in a gym. You know? You can stand it. That's if nobody's got space sickness, of course. We were lucky that way.

"But that's about how it's going to get anyway, you know. Outside the masks, it's soup. It isn't that you smell it so much. You kind of taste it, in the back of your mouth, and your eyes sting. That's after the first two or three months. Later on, it gets worse.

"And with the mask on, of course, the oxygen mixture is coming in under pressure. That's funny if you're not used to it. Your lungs have to work a little bit harder to get rid of it, especially when you're asleep, so after a while the muscles get sore. And then they get sorer. And then—

"Well.

"Before we take off, the psych people give us a long doo-da that keeps us from killing each other. But they can't stop us from thinking about it. And afterward, after we're back on Earth—this is what you won't read about in the articles—they keep us apart. You know how they work it? We get a pension, naturally. I mean there's got to be a pension, otherwise there isn't enough money in the world to make anybody go. But in the contract, it says to get the pension we have to stay in our own area.

"The whole country's marked off. Six sections. Each has at least one big city in it. I was lucky, I got a lot of them. They try to keep it so every man's home town is in his own section, but—well, like with us, Chowderhead and the captain both happened to come from Santa Monica. I think it was Chowderhead that got California, Nevada, all that Southwest area. It was the luck of the draw. God knows what the captain got.

"Maybe New Jersey," I said, and took another white pill.

We went on to another place and she said suddenly, "I figured something out. The way you keep looking around."

"What did you figure out?"

"Well, part of it was what you said about the other fellow getting New Jersey. This is New Jersey. You don't belong in this section, right?"

"Right," I said after a minute.

"So why are you here? I know why. You're here because you're looking for somebody."

"That's right."

She said triumphantly, "You want to find that other fellow from your crew! You want to fight him!"

I couldn't help shaking, white pills or no white pills. But I had to correct her.

"No. I want to kill him."

"How do you know he's here? He's got a lot of states to roam around in, too, doesn't he?"

"Six. New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland—all the way down to Washington."

"Then how do you know—"

"He'll be here." I didn't have to tell her how I knew. But I knew.

I wasn't the only one who spent his time at the border of his assigned area, looking across the river or staring across a state line, knowing that somebody was on the other side. I knew. You fight a war and you don't have to guess that the enemy might have his troops a thousand miles away from the battle line. You know where his troops will be. You know he wants to fight, too.

Hutta. Hutta.

I spilled my drink.

I looked at her. "You—you didn't—"

She looked frightened. "What's the matter?"

"Did you just sneeze?"

"Sneeze? Me? Did I—"

I said something quick and nasty, I don't know what. No! It hadn't been her. I knew it.

It was Chowderhead's sneeze.

Chowderhead. Marvin T. Roebuck, his name was. Five feet eight inches tall. Dark-complected, with a cast in one eye. Spoke with a Midwest kind of accent, even though he came from California—"shrick" for "shriek," "hawror" for "horror," like that. It drove me crazy after a while. Maybe that gives you an idea what he talked about mostly. A skunk. A thoroughgoing, deep-rooted, mother-murdering skunk.

I kicked over my chair and roared, "Roebuck! Where are you, damn you?"

The bar was all at once silent. Only the jukebox kept going.

"I know you're here!" I screamed. "Come out and get it! You louse, I told you I'd get you for calling me a liar the day Wally sneaked a smoke!"

Silence, everybody looking at me.

Then the door of the men's room opened.

He came out.

He looked lousy. Eyes all red-rimmed and his hair falling out—the poor crumb couldn't have been over twenty-nine. He shrieked, "You!" He called me a million names. He said, "You thieving rat, I'll teach you to try to cheat me out of my candy ration!"

He had a knife.

I didn't care. I didn't have anything and that was stupid, but it didn't matter. I got a bottle of beer from the next table and smashed it against the back of a chair. It made a good weapon, you know; I'd take that against a knife any time.

I ran toward him, and he came all staggering and lurching toward me, looking crazy and desperate, mumbling and raving—I could hardly hear him, because I was talking, too. Nobody tried to stop us. Somebody went out the door and I figured it was to call the cops, but that was all right. Once I took care of Chowderhead, I didn't care what the cops did.

I went for the face.

He cut me first. I felt the knife slide up along my left arm but, you know, it didn't even hurt, only kind of stung a little. I didn't care about that. I got him in the face, and the bottle came away, and it was all like gray and white jelly, and then blood began to spring out. He screamed. Oh, that scream! I never heard anything like that scream. It was what I had been waiting all my life for.

I kicked him as he staggered back, and he fell. And I was on top of him, with the bottle, and I was careful to stay away from the heart or the throat, because that was too quick, but I worked over the face, and I felt his knife get me a couple times more, and—

And—

And I woke up, you know. And there was Dr. Santly over me with a hypodermic needle that he'd just taken out of my arm, and four male nurses in fatigues holding me down. And I was drenched with sweat.

For a minute, I didn't know where I was. It was a horrible queasy falling sensation, as though the bar and the fight and the world were all dissolving into smoke around me.

Then I knew where I was.

It was almost worse.

I stopped yelling and just lay there, looking up at them.

Dr. Santly said, trying to keep his face friendly and noncommittal, "You're doing much better, Byron, boy. Much better."

I didn't say anything.

He said, "You worked through the whole thing in two hours and eight minutes. Remember the first time? You were sixteen hours killing him. Captain Van Wyck it was that time, remember? Who was it this time?"

"Chowderhead." I looked at the male nurses. Doubtfully, they let go of my arms and legs.

"Chowderhead," said Dr. Santly. "Oh—Roebuck. That boy," he said mournfully, his expression saddened, "he's not coming along nearly as well as you. Nearly. He can't run through a cycle in less than five hours. And, that's peculiar, it's usually you he— Well, I better not say that, shall I? No sense setting up a counter-impression when your pores are all open, so to speak?" He smiled at me, but he was a little worried in back of the smile.

I sat up. "Anybody got a cigarette?"

"Give him a cigarette, Johnson," the doctor ordered the male nurse standing alongside my right foot.

Johnson did. I fired up.

"You're coming along splendidly," Dr. Santly said. He was one of these psych guys that thinks if you say it's so, it makes it so. You know that kind? "We'll have you down under an hour before the end of the week. That's marvelous progress. Then we can work on the conscious level! You're doing extremely well, whether you know it or not. Why, in six months—say in eight months, because I like to be conservative—" he twinkled at me—"we'll have you out of here! You'll be the first of your crew to be discharged, you know that?"

"That's nice," I said. "The others aren't doing so well?"

"No. Not at all well, most of them. Particularly Dr. Gilvey. The run-throughs leave him in terrible shape. I don't mind admitting I'm worried about him."

"That's nice," I said, and this time I meant it.

He looked at me thoughtfully, but all he did was say to the male nurses, "He's all right now. Help him off the table."

It was hard standing up. I had to hold onto the rail around the table for a minute. I said my set little speech: "Dr. Santly, I want to tell you again how grateful I am for this. I was reconciled to living the rest of my life confined to one part of the country, the way the other crews always did. But this is much better. I appreciate it. I'm sure the others do, too."

"Of course, boy. Of course." He took out a fountain pen and made a note on my chart; I couldn't see what it was, but he looked gratified. "It's no more than you have coming to you, Byron," he said. "I'm grateful that I could be the one to make it come to pass."

He glanced conspiratorially at the male nurses. "You know how important this is to me. It's the triumph of a whole new approach to psychic rehabilitation. I mean to say our heroes of space travel are entitled to freedom when they come back home to Earth, aren't they?"

"Definitely," I said, scrubbing some of the sweat off my face onto my sleeve.

"So we've got to end this system of designated areas. We can't avoid the tensions that accompany space travel, no. But if we can help you eliminate harmful tensions with a few run-throughs, why, it's not too high a price to pay, is it?"

"Not a bit."

"I mean to say," he said, warming up, "you can look forward to the time when you'll be able to mingle with your old friends from the rocket, free and easy, without any need for restraint. That's a lot to look forward to, isn't it?"

"It is," I said. "I look forward to it very much," I said. "And I know exactly what I'm going to do the first time I meet one—I mean without any restraints, as you say," I said. And it was true; I did. Only it wouldn't be a broken beer bottle that I would do it with.

I had much more elaborate ideas than that.

—PAUL FLEHR

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction January 1958. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and typographical errors have been corrected without note.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Hated, by Frederik Pohl

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HATED ***

***** This file should be named 29503-h.htm or 29503-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/9/5/0/29503/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.