The Project Gutenberg EBook of The International Monthly, Volume 3, No. 2, May, 1851, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The International Monthly, Volume 3, No. 2, May, 1851 Author: Various Release Date: June 26, 2009 [EBook #29246] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY, MAY 1851 *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections.)

Transcriber's note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of Contents has been created for the HTML version.

GEORGE WILKINS KENDALL.

WASHINGTON.

WILLIAM HOGARTH.

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE.

YEAST: A PROBLEM.

THE LITTLENESS OF A GREAT PEOPLE.

A JEW AND A CHRISTIAN.

POLICARPA LA SALVARIETTA,

A REAL AMERICAN SAINT.

AUTHORS AND BOOKS.

THE FINE ARTS.

HAS THERE BEEN A GREAT POET IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY!

THE REAL ADVENTURES AND ACHIEVEMENTS OF GEORGE BORROW.

THE FAUN OVER HIS GOBLET.

THE JESUIT RELATIONS.

THE HAT REFORM AGITATION.

PROFESSIONAL DEVOTION.

"THE WILFULNESS OF WOMAN."

A STORY WITHOUT A NAME.

NATURAL REVELATION.

HEART-WHISPERS.

THE SNOWDROP IN THE SNOW.

THE COUNT MONTE-LEONE: OR, THE SPY IN SOCIETY.

LIFE AT A WATERING PLACE.

THE TWIN SISTERS.

ALFIERI.

ANECDOTES OF PAGANINI.

BIOGRAPHY OF FRENCH JOURNALISTS.

PROPHECY.

THE MODERN HAROUN-AL-RASCHID.

LOVE.—A SONNET.

THE HISTORY OF SORCERY AND MAGIC.[I]

HARTLEY COLERIDGE AND HIS GENIUS.

LYRA.—A LAMENT.

MY NOVEL:

A FAMILY OF OLD MAIDS.

HISTORICAL REVIEW OF THE MONTH.

RECORD OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY.

RECENT DEATHS.

"OTSEGO HALL," THE RESIDENCE OF J. FENIMORE COOPER.

GEORGE W. DEWEY.

LADIES' FASHIONS FOR THE EARLY SUMMER.

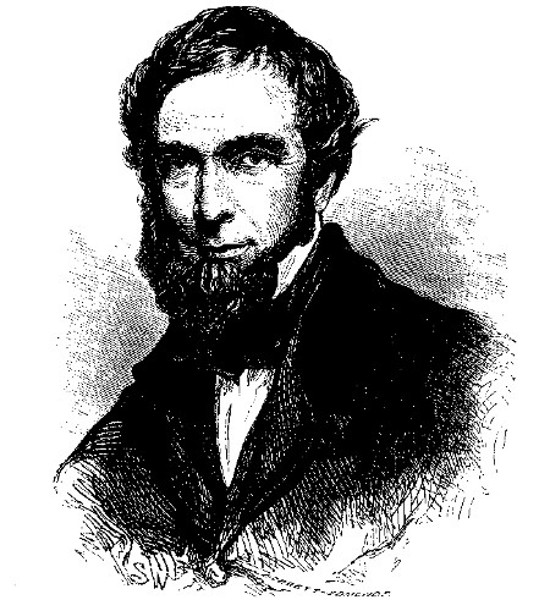

We have here a capital portrait of the editor in chief of the New Orleans Picayune, George W. Kendall, who, as an editor, author, traveller, or bon garçon, is world-famous, and every where entitled to be chairman in assemblies of these several necessary classes of people. Take him for all in all, he may be described as a new Chevalier Bayard, baptized in the spirit of fun, and with a steel pen in lieu of a blade of Damascus. He is a Vermonter—of the state which has sent out Orestes Brownson, Herman Hooker, the Coltons, Hiram Powers, Hannah Gould, and a crowd of other men and women with the sharpest intellects, and for the most part the genialist tempers too, that can be found in all the country. His boyhood was passed in the delightful village of Burlington, from which, when he was of age, he came to New-York, and here he lived until about the year 1835, when he went to New Orleans, where his subsequent career may be found traced in the most witty and brilliant and altogether successful journal ever published in the southern or western states.

Partly for the love of adventure and partly for advantage to his health, in the spring of 1841 Mr. Kendall determined to make an excursion into the great south-western prairies, and the contemplated trading expedition to Santa-Fe offering escort and agreeable companions, he procured passports from the Mexican vice-consul at New-Orleans, and joined it, at Austin. The history of this expedition has become an important portion of the history of the nation, and its details, embracing an account of his own captivity and sufferings in Mexico, were written by Mr. Kendall in one of the most spirited and graphic books of military and wilderness adventure, vicissitude, and endurance, that has been furnished in our times. The work was published in two volumes, by the Harpers, in 1844. It has since passed through many editions, and for the fidelity and felicity, the bravery and bon hommie, that mark all [Pg 146]its pages, it is likely to be one of the choicest chronicles that will be quoted from our own in the new centuries.

After the publication of his narrative of the Santa Fe Expedition, Mr. Kendall resumed his more immediate services in the Picayane—always, it may be said without injustice to his associates, most attractive under his personal supervision; and in the angry and war-tending controversies with Mexico which filled the public mind in the succeeding years, he was one of the calmest as well as wisest of our journalists. When at length the conflict came on, he attended the victorious Taylor as a member of his staff along the mountains and valleys which that great commander marked with the names of immortal victories, and had more than satisfaction for all griefs of his own in seeing the flag of his country planted in every scene in which his country had been insulted in his own person.

Upon the conclusion of the war, Mr. Kendall commenced the preparation of the magnificent work which has lately been published in this city by the Appletons, under the title of The War between the United States and Mexico, by George W. Kendall, illustrated by pictorial drawings by Carl Nebel. Mr. Nebel may be regarded as one of the best battle-painters living. He accompanied Mr. Kendall during the war, and made his sketches while on the several fields where he had witnessed the movements of the contending armies; and in all the accessories of scenery, costume, and general effect, he has unquestionably been as successful as the actors in the drama admit him to have been in giving a vivid and just impression of the distinguishing characteristics of each conflict. The subjects of the plates are the Bombardment of Vera Cruz, the Battle of Cerro Gordo, the Storming of Chepultepec, the Assault on Contreras, the Battle of Cherubusco, the Attack on Molino del Rey, General Scott's Entrance into Mexico, the Battle of Buena Vista, the Battle of Palo Alto, and the Capture of Monterey. In some cases, there are two representations of the same scene, taken from different points of view. These have all been reproduced in colored lithography by the best artists of Paris. The literary part of the work, comprising very careful and particular accounts of these events, is excellently written—so compactly and perspicuously, with so thorough a knowledge and so pure a taste, as to be deserving of applause among models in military history. Mr. Kendall passed about two years in Europe for the purpose of superintending its publication, and its success must have amply satisfied the most sanguine anticipations with which he entered upon its composition.

New England is largely represented among the leading editors of the South and West, and it is a little remarkable that the two papers most conspicuous as representatives of the idiosyncrasies which most obtain in their respective states—the Picayune and George D. Prentice's Louisville Journal—are conducted by men from sections most antagonistical in interest and feeling, men who have carried with them to their new homes and who still cherish there all the reciprocated affections by which they were connected with the North. When George W. Kendall leaves New Orleans for his summer wandering in our more comfortable and safe latitudes, an ovation of editors awaits him at every town along the Mississippi, and, crossing the mountains, he is the most popular member of the craft in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New-York, or Boston—an evidence that the strifes of party may exist without any personal ill-feeling, if the editor never forgets in his own person to sustain the character of a gentleman.

It is a truth, illustrated in daily experience, and yet rarely noted or acted upon, that, in all that concerns the appreciation of personal character or ability, the instinctive impressions of a community are quicker in their action, more profoundly appreciant, and more reliable, than the intellectual perceptions of the ablest men in the community. Upon all those subjects that are of moral apprehension, society seems to possess an intelligence of its own, infinitely sensitive in its delicacy, and almost conclusive in the certainty of its determinations; indirect, and unconscious in its operation, yet unshunnable in sagacity, and as strong and confident as nature itself. The highest and finest qualities of human judgment seem to be in commission among the nation, or the race. It is by such a process, that whenever a true hero appears among mankind, the recognition of his character, by the general sense of humanity, is instant and certain: the belief of the chief priests and rulers of mind follows later, or comes not at all. The perceptions of a public are as subtly-sighted as its passions are blind. It sees, and feels, and knows the excellence, which it can neither understand, nor explain, nor vindicate. These involuntary opinions of people at large explain themselves, and are vindicated by events, and form at last the constants of human understanding. A character of the first order of greatness, such as seems to pass out of the limits and courses of ordinary life, often lies above the ken of intellectual judgment; but its merits and its infirmities never escape the sleepless perspicacity of the common sentiment, which no novelty of form can surprise, and no mixture of qualities can perplex. The mind—the logical faculty—comprehends a subject, when it can trace in it the same elements, or relations, which it is familiar with elsewhere; if it finds but a faint analogy of form or substance, its decision is embarrassed. But this other instinct seems to become subtler, and more rapid, and more absolute in conviction, at the line where reason begins to falter.

Take the case of Shakspeare. His surpassing greatness was never acknowledged by the learned, until the nation had ascertained and settled it as a foregone and questionless conclusion. Even now, to the most sagacious mind of this time, the real ground and evidence of its own assurance of Shakspeare's supremacy, is the universal, deep, immovable conviction of it in the public feeling. There have been many acute essays upon his minor characteristics; but intellectual criticism has never grappled with Shaksperian ART in its entireness and grandeur, and probably it never will. We know not now wherein his greatness consists. We cannot demonstrate it. There is less indistinctness in the merit of less eminent authors. Those things which are not doubts to our consciousness, are yet mysteries to our mind. And if this is true of literary art, which is so much within the sphere of reflection, it may be expected to find more striking illustration in great practical and public moral characters.[Pg 147]

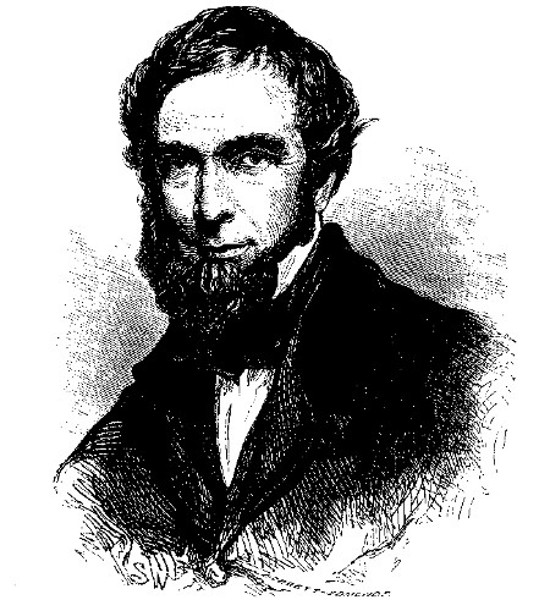

THE NATIONAL MONUMENT AT WASHINGTON.

THE NATIONAL MONUMENT AT WASHINGTON.

These considerations occur naturally to the mind in contemplating the fame of Washington. An attentive examination of the whole subject, and of all that can contribute to the formation of a sound opinion, results in the belief that General Washington's mental abilities illustrate the very highest type of greatness. His mind, probably, was one of the very greatest that was ever given to mortality. Yet it is impossible to establish that position by a direct analysis of his character, or conduct, or productions. When we look at the incidents or the results of that great career—when we contemplate the qualities by which it is marked, from its beginning to its end—the foresight which never was surprised, the judgment which nothing could deceive, the wisdom whose resources were incapable of exhaustion—combined with a spirit as resolute in its official duties as it was moderate in its private pretensions, as indomitable in its public temper as it was gentle in its personal tone—we are left in wonder and reverence. But when we would enter into the recesses of that mind—when we would discriminate upon its construction, and reason upon its operations—when we would tell how it was composed, and why it excelled—we are entirely at fault. The processes of Washington's understanding are entirely hidden from us. What came from it, in counsel or in action, was the life and glory of his country; what went on within it, is shrouded in impenetrable concealment. Such elevation in degree of wisdom, amounts almost to a change of kind, in nature, and detaches his intelligence from the sympathy of ours. We cannot see him as he was, because we are not like him. The tones of the mighty bell were heard with the certainty of Time itself, and with a force that vibrates still upon the air of life, and will vibrate for ever. But the clock-work, by which they were regulated and given forth, we can neither see nor understand. In fact, his intellectual abilities did not exist in an analytical and separated form; but in a combined and concrete state. They "moved altogether when they moved at all." They were in no degree speculative, but only practical. They could not act at all in the region of imagination, but only upon the field of reality. The sympathies of his intelligence dwelt exclusively in the national being and action. Its interests and energies were absorbed in them. He was nothing out of that sphere, because he was every thing there. The extent to which he was identified with the country is unexampled in the relations of individual men to the community. During the whole period of[Pg 148] his life he was the thinking part of the nation. He was its mind; it was his image and illustration. If we would classify and measure him, it must be with nations and not with individuals.

This extraordinary nature of Washington's capacities—this impossibility of analyzing and understanding the elements and methods of his wisdom—have led some persons to doubt whether, intellectually, he was of great superiority; but the public—the community—never doubted of the transcendent eminence of Washington's abilities. From the first moment of his appearance as the chief, the recognition of him, from one end of the country to the other, as the man—the leader, the counsellor, the infallible in suggestion and in conduct—was immediate and universal. From that moment to the close of the scene, the national confidence in his capacity was as spontaneous, as enthusiastic, as immovable, as it was in his integrity. Particular persons, affected by the untoward course of events, sometimes questioned his sufficiency; but the nation never questioned it, nor would allow it to be questioned. Neither misfortune, nor disappointment, nor accidents, nor delay, nor the protracted gloom of years, could avail to disturb the public trust in him. It was apart from circumstances; it was beside the action of caprice; it was beyond all visionary, and above all changeable feelings. It was founded on nothing extraneous; not upon what he had said or done, but upon what he was. They saw something in the man, which gave them assurance of a nature and destiny of the highest elevation—something inexplicable, but which inspired a complete satisfaction. We feel that this reliance was wise and right; but why it was felt, or why it was right, we are as much to seek as those who came under the direct impression of his personal presence. It is not surprising, that the world, recognizing in this man a nature and a greatness which philosophy cannot explain, should revere him almost to religion.

The distance and magnitude of those objects which are too far above us to be estimated directly—such as stars—are determined by their parallax. By some process of that kind we may form an approximate notion of Washington's greatness. We may measure him against the great events in which he moved; and against the great men, among whom, and above whom, his figure stood like a tower. It is agreed that the war of American Independence is one of the most exalted, and honorable, and difficult achievements related in history. Its force was contributed by many; but its grandeur was derived from Washington. His character and wisdom gave unity, and dignity, and effect to the irregular, and often divergent enthusiasm of others. His energy combined the parts; his intelligence guided the whole: his perseverance, and fortitude, and resolution, were the inspiration and support of all. In looking back over that period, his presence seems to fill the whole scene; his influence predominates throughout; his character is reflected from every thing. Perhaps nothing less than his immense weight of mind could have kept the national system, at home, in that position which it held, immovably, for seven years; perhaps nothing but the august respectability which his demeanor threw around the American cause abroad, would have induced a foreign nation to enter into an equal alliance with us, upon terms that contributed in a most important degree to our final success, or would have caused Great Britain to feel that no great indignity was suffered in admitting the claim to national existence of a people who had such a representative as Washington. What but the most eminent qualities of mind and feeling—discretion superhuman—readiness of invention, and dexterity of means, equal to the most desperate affairs—endurance, self-control, regulated ardor, restrained passion, caution mingled with boldness, and all the contrarieties of moral excellence—could have expanded the life of an individual into a career such as this?

If we compare him with the great men who were his contemporaries throughout the nation; in an age of extraordinary personages, Washington was unquestionably the first man of the time in ability. Review the correspondence of General Washington—that sublime monument of intelligence and integrity—scrutinize the public history and the public men of that era, and you will find that in all the wisdom that was accomplished was attempted, Washington was before every man in his suggestions of the plan, and beyond every one in the extent to which he contributed to its adoption. In the field, all the able generals acknowledged his superiority, and looked up to him with loyalty, reliance, and reverence; the others, who doubted his ability, or conspired against his sovereignty, illustrated, in their own conduct, their incapacity to be either his judges or his rivals. In the state, Adams, Jay, Rutledge, Pinckney, Morris—these are great names; but there is not one whose wisdom does not vail to his. His superiority was felt by all these persons, and was felt by Washington himself, as a simple matter of fact, as little a subject of question, or a cause of vanity, as the eminence of his personal stature. His appointment as commander-in-chief, was the result of no design on his part, and of no efforts on the part of his friends; it seemed to take place spontaneously. He moved into the position, because there was a vacuum which no other could supply: in it, he was not sustained by government, by a party, nor by connections; he sustained himself, and then he sustained every thing else. He sustained Congress against the army, and the army against the injustice of Congress. The brightest mind among his contemporaries was Hamilton's; a character which cannot be contemplated without frequent admiration, and constant affection. His talents took the form of genius, which Washington's did not. But active, various, and brilliant, as the faculties of Hamilton were, whether viewed in the precocity of youth, or in the all-accomplished elegance of maturer life—lightning quick as his intelligence was to see through every subject that came before it, and vigorous as it was in constructing the argumentation by which other minds were to be led, as upon a shapely bridge, over the obscure depths across which his had flashed in a moment—fertile and sound in schemes, ready in action, splendid in display, as he was—nothing is more obvious and certain than that when Mr. Hamilton approached Washington, he came into the presence of one who surpassed him in the extent, in the comprehension, the elevation, the sagacity, the force, and the ponderousness of his mind, as much as he did in the majesty of his aspect, and the grandeur of his step. The genius of Hamilton was a flower, which gratifies, surprises, and enchants; the intelligence of Washington was a stately tree,[Pg 149] which in the rarity and true dignity of its beauty is as superior, as it is in its dimensions.

THE GRAVE OF WASHINGTON.

THE GRAVE OF WASHINGTON.

The great comedian in pictorial art forms one of the subjects of Mrs. Hall's sketches, in the Pilgrimages to English Shrines, and we think her article upon visiting his tomb as interesting as any in this popular series:

Hogarth, the great painter-teacher of his age and country, was born in the parish of St. Bartholomew the Great, in London, on the 10th of November, 1697, and his trusty and sympathizing biographer, Allan Cunningham, says, "we have the authority of his own manuscripts for believing he was baptized on the 28th of the same month;" but the parish registers have been examined for confirmation with "fruitless solicitude." Cunningham gives December as the month of his birth; this is a mistake; so also is his notice of the painter's introduction of the Virago into his picture of the "Modern Midnight Conversation." No female figure appears in this subject. It is in the third plate of the "Rake's Progress" the woman alluded to is introduced. A small critic might here find a fit subject for vituperation, and loudly condemn Cunningham as a writer who was too idle to examine the works he was describing; pouncing on his minute errors, and forgetting the totality of his generous labors. Much of this spirit infests literature; and merges the kindly exposition of error into the bitterness of personal attack. The fallibility of human nature should teach us charity, and our own faults lead us to "more gently scan our brother man,"—a thing too often unthought of by those who are nothing if not critical, and as frequently nothing when they are. The painter was descended from a Westmoreland family. Sprung from an industrious race of self-helping yeomen, whose hardy toil brought them health and contentment, Hogarth had an early advantage, derived from his father's love of letters, which eventually drew him away from field and wood to the great London mart. Like thousands of others, he was unsuccessful. Fortunately, in this instance, his want of success in literature stimulated the strong mind of his son to seek occupation of more certain profit; and those who feel interest in the whereabouts of celebrated men, may think upon the days when William Hogarth wrought in silver, as the apprentice of Ellis Gamble, in Cranbourne Street, and speculate upon the change of circumstances, wrought by his own exertions, when, as a great painter, in after time, he occupied the house, now known as the Sabloniere Hotel, in Leicester Square.

Hogarth's character of mind, evidenced in his works and proved by his biography, is so perfectly honest, open, home-bred English, that we claim him with pride—as belonging exclusively to England. His originality is of English growth; his satire broad, bold, fair-play English. He was no screened assassin of character, either with pen or pencil; no journalist's hack to stab in secret—concealing his name, or assuming a forged one; no masked caricaturist, responsible to none. His philosophy was of the straightforward, clear-sighted English school; his theories—stern, simple, and unadorned—thoroughly English; his determination—proved in his love as well as in his hate—quite English; there is a firmness of purpose, a rough dignity, a John-Bull look in his broad intelligent face; the very fur round his cap must have been plain English rabbit-skin! No matter what "schools" were in fashion, Hogarth created and followed his own; no matter what was done, or said, or written, Hogarth maintained his opinion unflinchingly; he was not to be moved or removed from his resolve. His mind was vigorous and inflexible, and withal, keen and acute; and though the delicacy of his taste in this more refined age may be matter of question, there can be no doubt as to his integrity and uprightness of purpose—in his determination to denounce vice, and by that means cherish virtue.

Professor Leslie, in his eloquent and valuable Lectures on Painting, delivered in the spring of the present year to the students of the Royal Academy, has nobly vindicated Hogarth as an artist and a man, in words that all who heard will long remember. "Hogarth," he said, "it is true, is often gross; but it must be remembered that he painted in a less fastidious age than ours, and that his great object was to expose vice. Debauchery is always made by him detestable, never attractive." Charles Lamb, one of the best of his commentators, who has viewed his labors in a kindred spirit, speaking of one of his most elaborate and varied works, the "Election Entertainment," asks, "What is the result left on the mind? Is it an impression of the vileness and worthlessness of our species? Or is not the general feeling which remains after the individual faces have ceased to act sensibly on the mind, a kindly one in favor of the species?" Leslie speaks of his "high species of humor, pregnant with moral meanings," and no happier choice of phrase could characterize his many works. Lamb, with true discrimination, says: "All laughter is not of a dangerous or soul-hardening tendency. There is the petrifying sneer of a demon, which excludes and kills love, and there is the cordial laughter of a man, which implies and cherishes it."

Hogarth's works are before us all; and are lessons as much for to-day as they were for yesterday. We have no intention of scrutinizing their merits or defects; we write only of the influence of a class of art such as he brought courageously before the English public. Every one is acquainted with the "Rake's Progress," and can recall subject after subject, story after story, which he[Pg 150] illustrated. Comparatively few can judge of him as a painter, but all can comprehend his moral essays—brave as true!

His fearlessness and earnestness are above all price; independent, in their high estate, of all praise. We would send "Marriage à la Mode" into general circulation during the London season, where the market for wives and husbands is presided over by interest rather than affection. The matrimonial mart was as bravely exposed by the great satirist, as the brutal and unmanly cock-fight, which at that period was permitted to take place at the Cock-pit Royal, on the south side of St. James's Park.

Society always needs such men as William Hogarth—true, stern men—to grapple with and overthrow the vices which spring up—the very weeds both of poverty and luxury,—the latter filled with the more bitter and subtle poison. Calling to mind the period, we the more honor the great artist's resolution; if the delicacy of our improved times is offended by what may seem deformity upon his canvas, we must remember that we do not shrink from Hogarth's coarseness, but from the coarseness he labored, by exposing, to expel. He painted what Smollett, and Fielding, and Richardson wrote far more offensively; but he surpassed the novelists both in truth and in intention. He painted without sympathizing with his subjects, whom he lashed with unsparing bitterness or humor. He never idealized a vice into a virtue—he never compromised a fact, much less a principle.

He has, indeed, written fearful sermons on his canvas; sermons which, however exaggerated they may seem to us in some of their painful details of human sin and human misery, are yet so real, that we never doubt that such things were, and are. No one can suspect Hogarth to have been tainted by the vices he exposed. In this he has the advantage of the novelists of his period: he gives vice no loophole of escape: it is there in its hideous aspect, each step distinctly marked, each character telling its own tale of warning, so that "he who runs may read."

Whoever desires to trace the life of this English artist—to note him in his apprenticeship—when he tamed as well as his rough nature would permit, his hand to the delicate graving so cherished by his master, Ellis Gamble; and when freed from his apprenticeship, he sought art through the stirring scenes of life, saying quaintly enough, that "copying other men's works resembled pouring wine out of one vessel into another; there was no increase of quantity, and the flavor of the vintage was liable to evaporate;"—whoever would study the great, as well as the small, peculiarities of the painter who converted his thumb-nail into a palette, and while transcribing characters and events both rapidly and faithfully, complained of his "constitutional idleness:"—whenever, we say, our readers feel desirous of revelling in the biography of so diligent, so observing, so faithful, so brave a spirit, we should send them to our old friend Allan Cunningham's most interesting history of the man. Honest Allan had much in common with our great national artist: though of different countries, they sprung from the same race—sturdy yeomen; they were alike lovers of independence, fighting for the best part of life manfully and faithfully enjoying the noble scorn of wrong, and battling for the right from the cradle to the grave. Self-educated—that is to say, educated by Nature, which gave and nourished his high intellect and independent soul—Allan could comprehend and appreciate the manly bearing and stern self-reliance of the painter, whose best resources were in himself; thus the biography of Hogarth is among the finest examples of its class which our language supplies. Allan's sympathies were with his subject; and his knowledge also came to his aid: for the poet was thoroughly imbued with a love of art.

Allan Cunningham was a better disciplinarian, and less prone to look for or care for enjoyment, than Hogarth; though we have many pleasant memories how he truly relished both music and conversation. But there was more sentiment in the Scottish poet than in the English painter; and the deep dark eyes of the Scot had more of fervor and less of sarcasm in their brightness. We repeat, Allan, of all writers, could thoroughly appreciate Hogarth; and his biography is written con amore. He says that "all who love the dramatic representations of actual life,—all who have hearts to be gladdened by humor,—all who are pleased with judicious and well-directed satire,—all who are charmed with the ludicrous looks of popular folly, and all who can be moved with the pathos of human suffering, are admirers of Hogarth." But to our thinking; Hogarth had a calling even more elevated than the Scottish poet has given him in this eloquent summing-up of his attributes; "he is one of our greatest teachers—a teacher to whom is due the highest possible honor; and the more we feel the importance of the teacher, the more we value those who teach well. In grappling with folly and in combating with crimes, he was compelled to reveal the nature of that he proposed to satirize; he was obliged to set up sin in its high place before he could crown it with infamy." The times were full of internal as well as foreign disturbance, and Hogarth's studio was no hermitage to exclude passing events or their promoters. He lived with the living, moving present,—his engravings being his pleasures; portraits, as they are now to many a high-hearted man of talent, his means of subsistence; heavy weights of mortality that fetter and clog the ascending spirit.

His controversies and encounters with the worthless Wilkes,—his defence of his own theories,—his determined dislike to the establishment of a Royal Academy—his various other controversies—rendered his exciting course very different from that of the lonely artists of the present day, who are but too fond of living in closed studios, "pouring," as Hogarth would have said,—"pouring wine from one vessel into another,"—pondering over tales and poems for inspiration, and transcribing the worn-out models of many seasons into attitudes of bounding and varied life! Is it not wonderful, as sad, that the artist will not feel his power, will not take his own place, assume his high standing as of old, and demand the duty of respect from the world by the just exercise of his glorious privilege! "Entertainment and information are not all the mind requires at the hand of an artist; we wish to be elevated by contemplating what is noble,—to be warmed, by the presence of the heroic,—and charmed and made happy by the light of purity and loveliness. We desire to share in the lofty movements of fine minds—to have communion with their image of[Pg 151] what is godlike, and to take a part in the rapture of their love, and in the ecstasies of all their musings. This is the chief end of high poetry, of high painting, and high sculpture; and the man misunderstands the true spirit of those arts who seeks to deprive them of a portion of their divinity, and argues that entertainment and information constitute their highest aim." We have quoted this passage because it expresses our notions of the power of art more happily than we are able to express it; but we must add that the teaching as well as the poetic painter has much to complain of from society; it is impossible to mingle among the "higher classes" without being struck by their indifference to every phase of British art,—except portraiture. "Have you been to the Exhibition? Are there many nice miniatures? are the portraits good? Lady D.'s lace is perfect; Mrs. A.'s velvet is inimitable." Such observations strike the ear with painful discord, when the mind is filled with memories of those who are brave or independent enough to "look forward" with creative genius. There are many noble exceptions among our aristocracy; but with far too great a number art is a mere fashion.

HOGARTH'S HOUSE.

HOGARTH'S HOUSE.

As a people, neither our eyes nor our ears are yet opened to its instructive and elevating faculty. We mistake the outlay of money for an expenditure of sympathy.

Hogarth's portraits were almost too faithful to please his sitters: he was too truthful to flatter, even on canvas; and the wonder is that he achieved any popularity in this fantastic branch of his art. Allan Cunningham has said of him, that he regarded neither the historian's page, nor the poet's song. He was contented with the occurrences of the passing day, with the folly or the sin of the hour; yet to the garb and fashion of the moment, he adds story and sentiment for all time. It is quite delicious to read the excuses Allan makes for the foibles of the man whose virtues had touched his own generous heart; he confesses with great naiveté that he looked coldly—"too coldly, perhaps"—on foreign art, and perhaps too fondly on his own productions; and then adds that, "where vanity soonest misleads the judgment he thought wisely; he contemplated his own works, not as things excellent in themselves, but as the rudiments of future excellence, and looked forward with the hope that some happier Hogarth would raise, on the foundation he had laid, a perfect and lasting superstructure."

We must humbly differ from the poet in this matter; we believe, if the characteristic cap were removed from that sturdy brow, we should find an admirable development of the organ of self-esteem. He thought as little of a future and "happier Hogarth," as he did of the old masters. He was Monarch of the Present—and he knew it!

The age we live in talks much about renovation, but it is not a conservative age; on the contrary, it would pull down Temple Bar, if it dared, to widen the passage from the Strand into Fleet Street; and it demolishes houses, shrines of noble memories, with a total absence of respect for what it ought to honor. We never hear of an old house without a feeling that it is either going to be destroyed or modernized; and this inevitably leads to a desire to visit it immediately. Having determined on a drive to Chiswick to make acquaintance with the dwelling of Hogarth, and look upon his tomb—we became restless until it was accomplished.

We had seen, by the courtesy of Mr. Allison, the piano-forte manufacturer in Dean Street, the residence of Sir James Thornhill, whose daughter Hogarth married: the proprietor bestows most praiseworthy care on the house, which was formerly one of considerable extent and importance. Mr. Allison says there can be little doubt that the grounds extended into Wardour Street. Once, while removing a chimney-piece in the drawing-room,[Pg 152] a number of cards tumbled out—slips of playing-cards, with the names of some of the most distinguished persons of Hogarth's time written on the backs; the residences were also given, proving that the "gentry" then dwelt where now the poorer classes congregate. But the most interesting part of the house is the staircase, with its painted ceiling; the wall of the former is divided into three compartments, each representing a sort of ball-room back-ground, with groups of figures life-size, looking down from a balcony; they are well preserved, and one of the ladies is thought to be a very faithful portrait of Mrs. Hogarth. Hogarth must have spent some time in that house:—but we were resolved, despite the repute of its being old and ugly, to visit his dwelling-place at Chiswick; and though we made the pilgrimage by a longer route than was necessary, we did not regret skirting the beautiful plantations of the Duke of Devonshire, nor enjoying the fragrance of the green meadows, which never seem so green to us, as in the vale of the Thames. The house is a tall, narrow, abrupt-looking place, close to the roadside wall of its inclosed garden; numbers of cottage dwellings for the poor have sprung up around it, but in Hogarth's day it must have been very isolated: not leading to the water, as we had imagined, but having a dull and prison-like aspect; if, indeed, any place can have that aspect where trees grow, and grass is checkered by their ever-varying shadows. The house was occupied from 1814 to 1832 by Cary, the translator of Dante; and it would be worth a pilgrimage if considered only as the residence of this truly-excellent and highly-gifted clergyman.

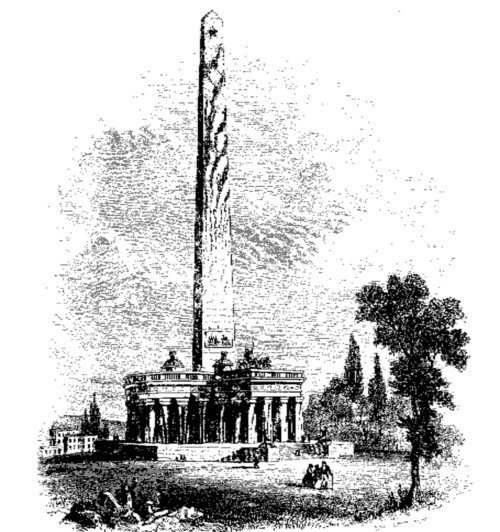

ROOM IN HOGARTH'S HOUSE.

ROOM IN HOGARTH'S HOUSE.

We have received from his son an interesting note relative to its features at the period when it came into his father's possession. "The house," he says, "stands in one corner of a high-walled garden of about three quarters of an acre, that part of the garden which faced the house was divided into long, narrow, formal flower-beds. Five large trees, whose ages bespoke their acquaintance with Hogarth, showed his love of the beautiful as well as the useful, a mulberry, walnut, apricot, double-blossomed cherry, and a hawthorn: the last of these was a great favorite with my father, from its beauty, and the attraction it was to the nightingale, which never failed to visit it in the spring: the gardeners were their mortal enemies, and alas, have at length prevailed. A few years ago, when I went to visit the old place, only one of the trees remained, (the mulberry seen in our sketch); in a nook at one side of the garden was a nut-walk, with a high wall and a row of filbert-trees that arched triumphantly over it; at one end of this walk was a stone slab, on which Hogarth used to play at nine-pins; at the other end were the two little tombstones to the memory of a bird and a dog." The house is as you see it here, the rooms with low ceilings and all sorts of odd shapes,—up and down, in and out,—yet withal pleasant and comfortable, and rendered more so by the gentle courtesy of their mistress and her kindly servant; the very dogs seemed to partake of the human nature of their protector, and attended us wherever we went, with more than ordinary civility. Hogarth might have been tempted to immortalize one of them for its extreme ugliness, and the waggish spirit with which it pulled at its companion's ears, who in vain attempted to tug at the bits of stumps that stuck out at either side of its tormentor's head. Mr. Fairholt was permitted to sketch the drawing room; the open door leads to the chamber from whence, it is said, Miss Thornhill eloped with Hogarth.

Mr. Cary, in the note to which we have already alluded, says, "there can hardly be a doubt that the house belonged to Sir James Thornhill, and that Hogarth inherited it from him. Mrs. Hogarth lived there after her husband's death, and left it by will to a lady from whose executor my father bought it in the year 1814. The room from which Miss Thornhill is said to have eloped is the inner room, on the first floor; this room was used[Pg 153] by my father as his study. Over the dining-room fireplace was a spirited pencil sketch of five heads, and under them written 'five jolly fellows,' by Hogarth—during an absence the servants of a tenant carefully washed all out."

We can easily imagine how the union between Hogarth and his daughter, commenced after such a fashion, outraged not only the courtliness, but the higher and better feelings of Sir James Thornhill. Hogarth's innate consciousness of power may at that time have appeared to him vulgar effrontery; and it is not to be wondered at, that, until convinced of his talent, he refused him all assistance. There is something so false and wrong in the concealment that precedes an elopement, and the elopement of an only child from an aged father, that we marvel how any one can treat lightly the outraged feelings of a confiding parent. Earnest tender love so deeply rooted in a father's heart may pardon, but cannot reach forgetfulness as quickly as it is the custom of play-writers and novelists to tell us it may do.

Sir James Thornhill was greatly the fashion; he was the successor of Verrio, and the rival of La Guerre, in the decorations of our palaces and public buildings. His demands for the painting of Greenwich Hall were contested; and though La Fosse received two thousand pounds for his works at Montague House, besides other allowances, Sir James, despite his dignity as Member of Parliament for his native town of Weymouth, could obtain but forty shillings a square yard for painting the cupola of St. Paul's! Thus the patronage afforded "native talent" kept him poor; and though it must have been necessary (one of the cruel necessities induced by love of display in England), to have an establishment suited to his public position in London, nothing could be more unpretending than his ménage at Chiswick. Mrs. Hogarth, advised by her mother, skilfully managed to let her father see one of her husband's best productions under advantageous circumstances. Sir James acknowledged its merit at once, exclaiming, "Very well! very well! The man who can make works like this can maintain a wife without a portion;" and soon after became not only reconciled, but generous to the young people. Hogarth had tasted the bitterness of labor; he had even worked for booksellers, and painted portraits!—so that this summer brightness must have been full of enjoyment. He appreciated it thoroughly, and was ever the earnest admirer and the ready defender of Sir James Thornhill; thus the old knight secured a friend in his son; and it was pleasanter to think of the hours of reconciliation and happiness they might have passed within the walls of that inclosed garden, beneath the crumbling trellice, or the shadow of the old mulberry tree, than of the fortuneless artist wooing the confiding daughter from her home and her filial duties.

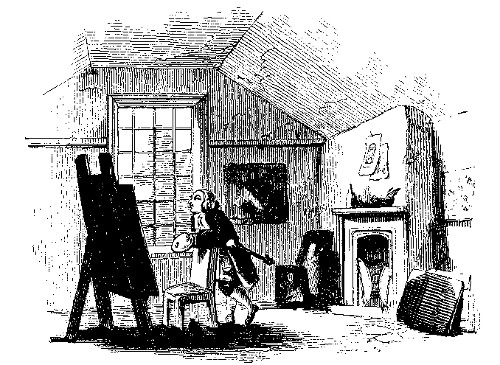

HOGARTH'S PAINTING-ROOM.

HOGARTH'S PAINTING-ROOM.

We were invited to inspect Hogarth's painting-room—a mere loft, of most limited dimensions, over the stable, which the imagination could easily furnish with the necessary easel, or still less cumbrous graver's implements. It is situated at the furthest part of the garden from the house; a small door in the garden-wall leads into a little inclosure, one side of which is occupied by the stable. The painting-room is over the stable, and is reached by a stair; it has but one window which looks towards the road. It must have been sufficiently commodious for Hogarth's purposes; but possesses not the conveniences of modern painting-rooms. The house at Chiswick could only have been a place for recreation and repose, where relaxation was cared for, and where sketches were prepared to ripen into publication.

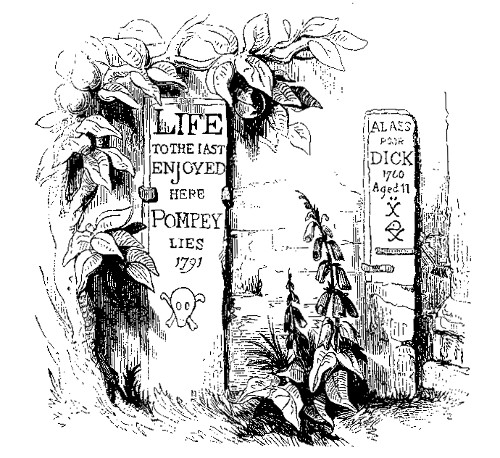

There are traditions about Chiswick of Hogarth having, while studying and taking notes, frequented a little inn by the roadside, and almost within sight of his dwelling. It has been modernized throughout—and supplies no subject for the pencil—yet it retains some indications, not without interest, of a remote date. The Painter must have been familiar with every class of character; and Chiswick was then enough of a country village to supply him amply with material. But, although a keen satirist, it is certain that he had as much tenderness for the lower orders of creation, as a young loving girl. In a corner of this quaint old garden, two tiny monuments are affixed to the wall, one chiselled perhaps by Hogarth's own hand, to the memory of his canary bird! The[Pg 154] thinking character of the painter's mind is evidenced in this as in every thing he did—the engraving on the tomb suggesting reflection. Charles Lamb said of him truly, that the quantity of thought which he crowded into every picture, would alone "unvulgarize" every subject he might choose; and the refined Coleridge exclaims, "Hogarth! in whom the satirist never extinguished that love of beauty which belonged to him as a poet." There is something inexpressibly tender and touching in this memento of his affection for a little singing bird: the feeling must have been entirely his own, for he had no child to suggest the tribute to a feathered favorite. The tomb was afterwards accompanied with one to Mrs. Hogarth's dog. They are narrow, upright pieces of white stone laid against the brick-wall, but they are records of gentle and generous sympathies not to be overlooked. That Hogarth was more than on friendly terms with the canine race, the introduction of his own dog into his portrait clearly tells, and doubtless his bird often brought with its music visions of the country into the heat and dust of Leicester Square—soothing away much of his impatience. Men who have to fight the up-hill battle of life, must have energy and determination; and Hogarth was too out-spoken and self-confident not to have made many enemies. In after years his success (limited though it was, in a pecuniary point of view, for he died without leaving enough to support his widow respectably), produced its ordinary results—envy and enmity: and insults were heaped upon him. He was not tardy of reply, but Wilkes and Churchill were in strong health when nature was giving way with the great painter; an advantage they did not fail to use with their accustomed malignity. The profligate Churchill, turning the poet's nature into gall, infested the death-bed of Hogarth with unfeeling sarcasm, anticipating the grave, and exulting over a dying man.

TOMBS OF DOG AND BIRD.

TOMBS OF DOG AND BIRD.

Hogarth, warned by the autumn winds, and suffering from the restlessness of approaching dissolution, left Chiswick on the 25th of October, 1764, and returned to his residence in Leicester Square. He was cheerful—in full possession of his mental faculties, but lacked the vigor to exert them. The very next day, having received an agreeable letter from Doctor Franklin, he wrote a rough copy of his answer, but exhausted with the effort, retired to bed. Seized by a sudden sickness, he arose—rung the bell with alarming violence—and within two hours expired!

Of all the villages in the neighborhood of London, rising from the banks of the Thames, (and how numerous and beautiful they are!) few are so well known as that of Chiswick. The horticultural fêtes are anticipated with anxiety similar to that our grandmothers felt for the fêtes of Ranelagh; the toilettes of the ladies rival the flowers, and the only foe to the fascinating fair ones is the weather; but all which the crowd care about in Chiswick is confined to the "Duke's grounds" and the Society's Gardens. The Duke's beautiful little villa, erected by the last Earl of Burlington, is indeed a shrine worthy of deep homage; within its walls both Charles James Fox and George Canning breathed their last; and if, for a moment, we recall the times of Civil War, when each honest English heart fought bravely and openly for what was believed "the right," we may picture the struggle between Prince Rupert and the Earl of Essex, terminating with doubtful success, for eight hundred high born cavaliers were left dead on the plain that lies within sight of the gardens so richly perfumed by flowers, and echoing not to the searching trumpet or rolling drum, but to the gossamer music of Strauss and Jullien.

The Duke of Devonshire's grounds, containing about ninety acres, are filled with mementos, pleasant to the eye and suggestive to the imagination; but we must seek and find a more solemn scene, where the churchyard of Chiswick incloses the ashes of some whose names are written upon[Pg 155] the pages of History. Though the church is, in a degree, surrounded by houses, there is much of the repose of "a country churchyard" about it; the Thames belts it with its silver girdle, and when we visited its sanctuary, the setting sun cast a mellow light upon the windows of the church, touching a headstone or an urn, while the shadows trembled on the undulating graves. Like all church-yards it is crowded, and however reverently we bent our footsteps, it was impossible to avoid treading on the soft grass of the humble grave, or the gray stone that marks the resting-place of one of "the better order."

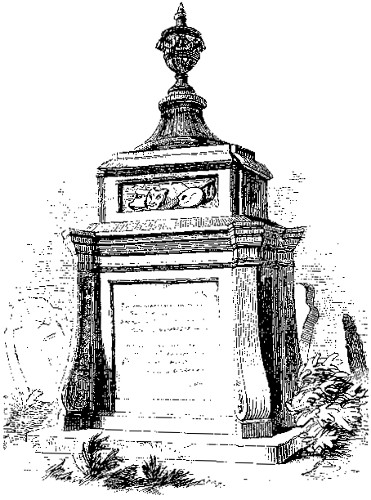

HOGARTH'S TOMB.

HOGARTH'S TOMB.

How like the world was that silent churchyard! High and low, rich and poor, mingled together, and yet avoiding to mingle. The dust of the imperious Duchess of Cleveland found here a grave; while here too, as if to contrast the pure with the impure, repose the ashes of Mary, daughter of Oliver Cromwell; Holland the actor, the friend of David Garrick, here cast aside his "motley." Can we wonder at the actor's love of applause?—posterity knows him not; present fame alone is his—the lark's song leaves no record in the air!—Lord Macartney, the famous ambassador to China, a country of which our knowledge was then almost as dim as that we have of the moon—the ambassador rests here, while a Chinese junk is absolutely moored in the very river that murmurs beside his grave! Surely the old place is worthy of a pilgrimage. Loutherbourg, the painter, found a resting-place in its churchyard. Ralph, the historian and political writer, whose histories and politics are now as little read as the Dunciad which held them up to ridicule, is buried here; and confined as is the space, it is rich in epitaphs,—three are from the pen of David Garrick, two from that of Arthur Murphy.

Hogarth's monument has been very faithfully copied by Mr. Fairholt.

It is remarkable among the many plainer "stones" with which the churchyard is crowded, but is by no means distinguished for that artistic character—which it might have received as covering the remains of so great an artist. A small slab, in relief, takes from it, however, the charge of insipidity; it contains a comic mask, an oak branch, pencils and mahl-stick, a book and a scroll, and the palette, marked with the "line of beauty."

It has been remarked, that "while he faithfully followed nature through all her varieties, and exposed, with inimitable skill, the infinite follies and vices of the world, he was in himself an example of many virtues." And the following poetical tribute by David Garrick is inscribed on the tomb:

Dr. Johnson also composed an epitaph, which Cunningham considers "more to the purpose, but still unworthy:"

The tributes—in poetry and prose—are just, examine the works of this great painter-teacher as closely and suspiciously as we may, we can discover nothing that will induce a momentary doubt of his integrity of purpose in all he did; his shafts were aimed at Vice,—in no solitary instance was he ever guilty of arraigning or assailing Virtue. Compare him with the most famous of the Dutch masters, and he rises into glory; coarseness and vulgarity in them had no point out of which could come instruction. If they picture the issues of their own minds, they must have been gross and sensual; they ransacked the muck of life, and the grovelling in character, for themes that one should see only by compulsion. But Hogarth's subjects were never without a lesson, and, inasmuch as he resorted for them to the open volume of humanity, like those of the most immortal of our writers, his works are "not for an age but for all time."

The author of The House of Seven Gables is now about forty-five years of age. He was born in Salem, Massachusetts, and is of a family which for several generations has "followed the sea." Among his ancestors, I believe, was the "bold Hawthorne," who is celebrated in a revolutionary ballad as commander of the "Fair American." He was educated at Bowdoin College in Maine, where he graduated in 1825.

Probably he appeared in print before that time, but his earliest volume was an anonymous and never avowed romance which was published in Boston in 1832. It attracted little attention, but among those who read it with a just appreciation of the author's genius was Mr. S. G. Goodrich, who immediately secured the shrouded star for The Token, of which he was editor, and through which many of Hawthorne's finest tales and essays were originally given to the public. He published in 1837 the first and in 1842 the second volume of his Twice-Told Tales, embracing whatever he wished to preserve from his contributions to the magazines; in 1845 he edited The Journal of an African Cruiser; in 1846 published Mosses from an Old Manse, a second collection of his magazine papers; in 1850 The Scarlet Letter, and in the last month the longest and in some respects the most remarkable of his works, The House of Seven Gables.

In the introductions to the Mosses from an Old Manse and The Scarlet Letter we have some glimpses of his personal history. He had been several years in the Custom-House at Boston, while Mr. Bancroft was collector, and afterwards had joined that remarkable association, the "Brook Farm Community," at West Roxbury, where, with others, he appears to have been reconciled to the old ways, as quite equal to the inventions of Fourier, St. Simon, Owen, and the rest of that ingenious company of schemers who have been so intent upon a reconstruction of the foundations of society. In 1843, he went to reside in the pleasant village of Concord, in the "Old Manse," which had never been profaned by a lay occupant until he entered it as his home. In the introduction to The Mosses he says:

"A priest had built it; a priest had succeeded to it; other priestly men, from time to time, had dwelt in it; and children, born in its chambers, had grown up to assume the priestly character. It was awful to reflect how many sermons must have been written there. The latest inhabitant alone—he, by whose translation to Paradise the dwelling was left vacant—had penned nearly three thousand discourses, besides the better, if not the greater number, that gushed living from his lips. How often, no doubt, had he paced to and fro along the avenue, attuning his meditations, to the sighs and gentle murmurs, and deep and solemn peals of the wind, among the lofty tops of the trees! In that variety of natural utterances, he could find something accordant with every passage of his sermon, were it of tenderness or reverential fear. The boughs over my head seemed shadowy with solemn thoughts, as well as with rustling leaves. I took shame to myself for having been[Pg 157] so long a writer of idle stories, and ventured to hope that wisdom would descend upon me with the falling leaves of the avenue; and that I should light upon an intellectual treasure, in the Old Manse, well worth those hoards of long-hidden gold, which people seek for in moss-grown houses. Profound treatises of morality—a layman's unprofessional, and therefore unprejudiced views of religion;—histories (such as Bancroft might have written, had he taken up his abode here, as he once purposed), bright with picture, gleaming over a depth of philosophic thought;—these were the works that might fitly have flowed from such a retirement. In the humblest event, I resolved at least to achieve a novel, that should evolve some deep lesson, and should possess physical substance enough to stand alone. In furtherance of my design, and as if to leave me no pretext for not fulfilling it, there was, in the rear of the house, the most delightful little nook of a study that ever offered its snug seclusion to a scholar. It was here that Emerson wrote 'Nature;' for he was then an inhabitant of the Manse, and used to watch the Assyrian dawn and the Paphian sunset and moonrise, from the summit of our eastern hill. When I first saw the room, its walls were blackened with the smoke of unnumbered years, and made still blacker by the grim prints of puritan ministers that hung around. These worthies looked strangely like bad angels, or, at least, like men who had wrestled so continually and so sternly with the devil, that somewhat of his sooty fierceness had been imparted to their own visages. They had all vanished now; a cheerful coat of paint, and gold tinted paper hangings, lighted up the small apartment; while the shadow of a willow-tree, that swept against the overhanging eaves, attempered the cheery western sunshine. In place of the grim prints there was the sweet and lovely head of one of Raphael's Madonnas, and two pleasant little pictures of the Lake of Como. The only other decorations were a purple vase of flowers, always fresh, and a bronze one containing graceful ferns. My books (few, and by no means choice; for they were chiefly such waifs as chance had thrown in my way) stood in order about the room, seldom to be disturbed."

In his home at Concord, thus happily described, in the midst of a few congenial friends, Hawthorne passed three years; and, "in a spot so sheltered from the turmoil of life's ocean," he says, "three years hasten away with a noiseless flight, as the breezy sunshine chases the cloud-shadows across the depths of a still valley." But at length his repose was invaded by that "spirit of improvement," which is so constantly marring the happiness of quiet-loving people, and he was compelled to look out for another residence.

"Now came hints, growing more and more distinct, that the owner of the old house was pining for his native air. Carpenters next appeared, making a tremendous racket among the outbuildings, strewing green grass with pine shavings and chips of chesnut joists, and vexing the whole antiquity of the place with their discordant renovations. Soon, moreover, they divested our abode of the veil of woodbine which had crept over a large portion of its southern face. All the aged mosses were cleared unsparingly away; and there were horrible whispers about brushing up the external walls with a coat of paint—a purpose as little to my taste as might be that of rouging the venerable cheeks of one's grandmother. But the hand that renovates is always more sacrilegious than that which destroys. In fine, we gathered up our household goods, drank a farewell cup of tea in our pleasant little breakfast-room—delicately-fragrant tea, an unpurchasable luxury, one of the many angel-gifts that had fallen like dew upon us—and passed forth between the tall stone gate-posts, as uncertain as the wandering Arabs where our tent might next be pitched. Providence took me by the hand, and—an oddity of dispensation which, I trust, there is no irreverence in smiling at—has led me, as the newspapers announce while I am writing, from the old Manse into a Custom House! As a story-teller, I have often contrived strange vicissitudes for my imaginary personages, but none like this. The treasure of intellectual gold which I had hoped to find in our secluded dwelling, had never come to light. No profound treatise of ethics—no philosophic history—no novel, even, that could stand unsupported on its edges—all that I had to show, as a man of letters, were these few tales and essays, which had blossomed out like flowers in the calm summer of my heart and mind."

The Mosses from an Old Manse he declared the last offering of their kind he should ever put forth; "unless I can do better," he wrote in this Introduction, "I have done enough in this kind." He went to his place in the Custom House, in his native city, and if President Taylor's advisers had not been apprehensive that in his devotion to ledgers he would neglect the more important duties of literature, perhaps we should have heard no more of him; but those patriotic men, remembering how much they had enjoyed the reading of the Twice-Told Tales and the Mosses, induced the appointment in his place of a whig, who had no capacity for making books, and in the spring of last year we had The Scarlet Letter.

Like most of his shorter stories, The Scarlet Letter finds its scene and time with the earlier Puritans. Its argument involves the analysis and action of remorse in the heart of a person who, himself unsuspected, is compelled to assist in the punishment of the partner of his guilt. This peculiar and powerful fiction at once arrested attention, and claimed for its author the eminence as a novelist which his previous performances had secured for him as a writer of tales. Its whole atmosphere and the qualities of its characters demanded for a creditable success very unusual capacities. The frivolous costume and brisk action of the story of fashionable life are easily depicted by the practised sketcher, but a work like The Scarlet Letter comes slowly upon the canvas, where passions are commingled and overlaid with the deliberate and masterly elaboration with which the grandest effects are produced in pictorial composition and coloring. It is a distinction of such works that while they are acceptable to the many, they also surprise and delight the few who appreciate the nicest arrangement and the most high and careful finish. The Scarlet[Pg 158] Letter will challenge consideration in the name of Art, in the best audience which in any age receives Cervantes, Le Sage, or Scott.

Following this romance came new editions of True Stories from History and Biography, a volume for youthful readers, and of the Twice-Told Tales. In the preface to the latter, underrating much the reputation he has acquired by them, he says:

"The author of Twice-Told Tales has a claim to one distinction, which, as none of his literary brethren will care about disputing it with him, he need not be afraid to mention. He was for a good many years the obscurest man of letters in America. These stories were published in magazines and annuals, extending over a period of ten or twelve years, and comprising the whole of the writer's young manhood, without making (so far as he has ever been aware) the slightest impression on the public. One or two among them, the Rill from the Town Pump, in perhaps a greater degree than any other, had a pretty wide newspaper circulation; as for the rest, he has no grounds for supposing that on their first appearance they met with the good or evil fortune to be read by any body. Throughout the time above specified he had no incitement to literary effort in a reasonable prospect of reputation or profit; nothing but the pleasure itself of composition—an enjoyment not at all amiss in its way, and perhaps essential to the merit of the work in hand, but which, in the long run, will hardly keep the chill out of a writer's heart, or the numbness out of his fingers. To this total lack of sympathy, at the age when his mind would naturally have been most effervescent, the public owe it (and it is certainly an effect not to be regretted, on either part), that the author can show nothing for the thought and industry of that portion of his life, save the forty sketches, or thereabouts, included in these volumes. Much more, indeed, he wrote; and some very small part of it might yet be rummaged out (but it would not be worth the trouble) among the dingy pages of fifteen or twenty year old periodicals, or within the shabby morocco covers of faded Souvenirs. The remainder of the works alluded to had a very brief existence, but, on the score of brilliancy, enjoyed a fate vastly superior to that of their brotherhood, which succeeded in getting through the press. In a word, the author burned them without mercy or remorse, and, moreover, without any subsequent regret, and had more than one occasion to marvel that such very dull stuff as he knew his condemned manuscripts to be, should yet have possessed inflammability enough to set the chimney on fire!...

"As he glances over these long-forgotten pages, and considers his way of life while composing them, the author can very clearly discern why all this was so. After so many sober years, he would have reason to be ashamed if he could not criticise his own work as fairly as another man's; and, though it is little his business and perhaps still less his interest, he can hardly resist a temptation to achieve something of the sort. If writers were allowed to do so, and would perform the task with perfect sincerity and unreserve, their opinions of their own productions would often be more valuable and instructive than the works themselves. At all events, there can be no harm in the author's remarking that he rather wonders how the Twice-Told Tales should have gained what vogue they did, than that it was so little and so gradual. They have the pale tint of flowers that blossomed in too retired a shade—the coolness of a meditative habit, which diffuses itself through the feeling and observation of every sketch. Instead of passion, there is sentiment; and, even in what purport to be pictures of actual life, we have allegory, not always so warmly dressed in its habiliments of flesh and blood as to be taken into the reader's mind without a shiver. Whether from lack of power or an unconquerable reserve, the author's touches have often an effect of tameness; the merriest man can hardly contrive to laugh at his broadest humor, the tenderest woman, one would suppose, will hardly shed warm tears at his deepest pathos. The book, if you would see any thing in it, requires to be read in the clear, brown, twilight atmosphere in which it was written; if opened in the sunshine, it is apt to look exceedingly like a volume of blank pages....

"The author would regret to be understood as speaking sourly or querulously of the slight mark made by his earlier literary efforts on the public at large. It is so far the contrary, that he has been moved to write this preface, chiefly as affording him an opportunity to express how much enjoyment he has owed to these volumes, both before and since their publication. They are the memorials of very tranquil, and not unhappy years. They failed, it is true—nor could it have been otherwise—in winning an extensive popularity. Occasionally, however, when he deemed them entirely forgotten, a paragraph or an article, from a native or foreign critic, would gratify his instincts of authorship with unexpected praise,—too generous praise, indeed, and too little alloyed with censure, which, therefore, he learned the better to inflict upon himself. And, by-the-by, it is a very suspicious symptom of a deficiency of the popular element in a book, when it calls forth no harsh criticism. This has been particularly the fortune of the Twice-Told Tales. They made no enemies, and were so little known and talked about, that those who read, and chanced to like them, were apt to conceive the sort of kindness for the book, which a person naturally feels for a discovery of his own. This kindly feeling (in some cases, at least) extended to the author, who, on the internal evidence of his sketches, came to be regarded as a mild, shy, gentle, melancholic, exceedingly sensitive, and not very forcible man, hiding his blushes under an assumed name, the quaintness of which was supposed, somehow or other, to symbolize his personal and literary traits. He is by no means certain that some of his subsequent productions have not been influenced and modified by a natural desire to fill up so amiable an outline, and to act in consonance with the character assigned to him; nor, even now, could he forfeit it without a few tears of tender sensibility. To conclude, however,—these volumes have opened the way to most agreeable associations, and to the formation of imperishable friendships; and there are many golden threads, interwoven with his present happiness, which he can follow up more or less directly, until he finds their commencement here; so that his pleasant pathway among realities seems to proceed out of the Dream-Land of his youth, and to be bordered with just enough of its shadowy foliage to shelter him from the heat of the[Pg 159] day. He is therefore satisfied with what the Twice-Told Tales have done for him, and feels it to be far better than fame."

That there should be any truth in this statement that the public was so slow to recognize so fine a genius, is a mortifying evidence of the worthlessness of a literary popularity. But it may be said of Hawthorne's fame that it has grown steadily, and that while many who have received the turbulent applause of the multitude since he began his career are forgotten, it has widened and brightened, until his name is among the very highest in his domain of art, to shine there with a lustre equally serene and enduring.

Mr. Hawthorne's last work is The House of Seven Gables, a romance of the present day. It is not less original, not less striking, not less powerful, than The Scarlet Letter. We doubt indeed whether he has elsewhere surpassed either of the three strongly contrasted characters of the book. An innocent and joyous child-woman, Phœbe Pyncheon, comes from a farm-house into the grand and gloomy old mansion where her distant relation, Hepzibah Pyncheon, an aristocratical and fearfully ugly but kind-hearted unmarried woman of sixty, is just coming down from her faded state to keep in one of her drawing-rooms a small shop, that she may be able to maintain an elder brother who is every moment expected home from a prison to which in his youth he had been condemned unjustly, and in the silent solitude of which he has kept some lineaments of gentleness while his hair has grown white, and a sense of beauty while his brain has become disordered and his heart has been crushed and all present influences of beauty have been quite shut out. The House of Seven Gables is the purest piece of imagination in our prose literature.

The characteristics of Hawthorne which first arrest the attention are imagination and reflection, and these are exhibited in remarkable power and activity in tales and essays, of which the style is distinguished for great simplicity, purity and tranquillity. His beautiful story of Rappacini's Daughter was originally published in the Democratic Review, as a translation from the French of one M. de l'Aubépine, a writer whose very name, he remarks in a brief introduction, (in which he gives in French the titles of some of his tales, as Contes deux foix racontées, Le Culte du Feu, etc.) "is unknown to many of his countrymen, as well as to the student of foreign literature." He describes himself, under this nomme de plume, as one who—

"Seems to occupy an unfortunate position between the transcendentalists (who under one name or another have their share in all the current literature of the world), and the great body of pen-and-ink men who address the intellect and sympathies of the multitude. If not too refined, at all events too remote, too shadowy and unsubstantial, in his mode of development, to suit the taste of the latter class, and yet too popular to a satisfy the spiritual or metaphysical requisitions of the former, he must necessarily find himself without an audience, except here and there an individual, or possibly an isolated clique."

His writings, to do them justice, he says—

"Are not altogether destitute of fancy and originality; they might have won him greater reputation but for an inveterate love of allegory, which is apt to invest his plots and characters with the aspect of scenery and people in the clouds, and to steal away the human warmth out of his conceptions. His fictions are sometimes historical, sometimes of the present day, and sometimes, so far as can be discovered, have little or no reference either to time or space. In any case, he generally contents himself with a very slight embroidery of outward manners,—the faintest possible counterfeit of real life,—and endeavors to create an interest by some less obvious peculiarity of the subject. Occasionally a breath of nature, a rain-drop of pathos and tenderness, or a gleam of humor, will find its way into the midst of his fantastic imagery, and make us feel as if, after all, we were yet within the limits of our native earth. We will only add to this cursory notice, that M. de l'Aubépine's productions, if the reader chance to take them in precisely the proper point of view, may amuse a leisure hour as well as those of a brighter man; if otherwise, they can hardly fail to look excessively like nonsense."

Hawthorne is as accurately as he is happily described in this curious piece of criticism, though no one who takes his works in the "proper point of view," will by any means agree to the modest estimate which, in the perfect sincerity of his nature, he has placed upon them. He is original, in invention, construction, and expression, always picturesque, and sometimes in a high degree dramatic. His favorite scenes and traditions are those of his own country, many of which he has made classical by the beautiful associations that he has thrown around them. Every thing to him is suggestive, as his own pregnant pages are to the congenial reader. All his productions are life-mysteries, significant of profound truths. His speculations, often bold and striking, are presented with singular force, but with such a quiet grace and simplicity as not to startle until they enter in and occupy the mind. The gayety with which his pensiveness is occasionally broken, seems more than any thing else in his works to have cost some effort. The gentle sadness, the "half-acknowledged melancholy," of his manner and reflections, are more natural and characteristic.

His style is studded with the most poetical imagery, and marked in every part with the happiest graces of expression, while it is calm, chaste, and flowing, and transparent as water. There is a habit among nearly all the writers of imaginative literature, of adulterating the conversations of the poor with barbarisms and grammatical blunders which have no more fidelity than elegance. Hawthorne's integrity as well as his exquisite—taste prevented him from falling into this error. There is not in the world a large rural population that speaks its native language with a purity approaching that with which the English is spoken by the[Pg 160] common people of New England. The vulgar words and phrases which in other states are supposed to be peculiar to this part of the country are unknown east of the Hudson, except to the readers of foreign newspapers, or the listeners to low comedians who find it profitable to convey such novelties into Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Vermont. We are glad to see a book that is going down to the next ages as a representative of national manners and character in all respects correct.

Nathaniel Hawthorne is among the first of the first order of our writers, and in their peculiar province his works are not excelled in the literature of the present day or of the English language.

The Rev. Mr. Kingsley, author of Alton Locke, has collected into a book the series of vehement and yeasty papers which have appeared from his pen in Fraser's Magazine under the above title, and a new impulse is thus given in England to the discussion of the Problem of Society. The declared object of the work—which is of the class of philosophical novels—is to exhibit the miseries of the poor; the conventionalisms, hypocrisies, and feebleness of the rich; the religious doubts of the strong, and the miserable delusions and superstitions of the weak; the mammon-worship of the middling and upper classes, and the angry humility of the masses. The story is very slight, but sufficient for the effective presentation of the author's opinions. The best characters are an Irish parson, a fox-hunting squire and his commonplace worldly wife, and a thoughtless and reckless but not unkind man of the world. Here is a sketch of a commonplace old English vicar, such as has been familiar in the pages of novels and essays time out of mind:

"He told me, hearing me quote Schiller, to beware of the Germans, for they were all Pantheists at heart. I asked him whether he included Lange and Bunsen, and it appeared that he had never read a German book in his life. He then flew furiously at Mr. Carlyle, and I found that all he knew of him was from a certain review in the Quarterly. He called Boëhmen a theosophic Atheist. I should have burst out at that, had I not read the very words in a High Church review, the day before, and hoped that he was not aware of the impudent falsehood which he was retailing. Whenever I feebly interposed an objection to any thing he said (for, after all he talked on), he told me to hear the Catholic Church. I asked him which Catholic Church? He said the English. I asked him whether it was to be the Church of the sixth century, or the thirteenth, or the seventeenth, or the eighteenth? He told me the one and eternal Church, which belonged as much to the nineteenth century as to the first. I begged to know whether, then, I was to hear the Church according to Simeon, or according to Newman, or according to St. Paul; for they seemed to me a little at variance? He told me, austerely enough, that the mind of the Church was embodied in her Liturgy and Articles. To which I answered, that the mind of the episcopal clergy might, perhaps, be; but, then, how happened it that they were always quarreling and calling hard names about the sense of those very documents? And so I left him, assuring him that living in the nineteenth century, I wanted to hear the Church of the nineteenth century, and no other; and should be most happy to listen to her, as soon as she had made up her mind what to say."

English travellers in America give very minute accounts of the bad grammar and questionable pronunciation they sometimes hear among our common people: with what advantage they might go into the rural neighborhoods of their own country for exhibitions in this line is shown by the following description of a scene in a booth, which one of the characters of Mr. Kingsley enters at night: