The Project Gutenberg eBook of Poems of Henry Vaughan, Silurist, Volume

II, by Henry Vaughan, et al, Edited by E. K. Chambers

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Poems of Henry Vaughan, Silurist, Volume II

Author: Henry Vaughan

Editor: E. K. Chambers

Release Date: March 20, 2009 [eBook #28375]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK POEMS OF HENRY VAUGHAN, SILURIST, VOLUME II***

E-text prepared by Susan Skinner, David Cortesi,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

In the poem "In Etesiam Lachrymantem" (page 221)

the initial letter of

the final line is missing in all extant editions; it is shown as a

question-mark.

In the Boethius translation Lib. IV. Metrum VI. (page 230),

the letter

'y' has been added to make line 9/10 read "...though

they/See other

stars..." although it is missing in all available editions.

At many points a period, comma or hyphen seems to be omitted in the

original. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Where missing

punctuation is not clearly an error, or the omission is harmless to the

sense, the text remains as in the original.

Footnotes in the original appear on the page where they are referenced

and are numbered from 1 on each page. In this edition footnotes are numbered

consecutively throughout the book and are grouped following each chapter

or poem to which they refer. A footnote reference is linked to the

note text, and the text links back to the reference.

POEMS

OF

HENRY VAUGHAN

SILURIST.

Vol. II.

POEMS

OF

HENRY VAUGHAN

SILURIST

EDITED BY

E. K. CHAMBERS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

CANON BEECHING

VOL. II.

LONDON:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS, LIMITED

NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON & CO.

[vii]

| |

|

page |

| Table Of Contents |

vii |

| Biographical Note |

xv |

| Bibliography Of Henry Vaughan's Works |

lvii |

| Poems With The Tenth Satire Of Juvenal Englished, 1646 |

1 |

| | To all Ingenious Lovers of Poesy |

3 |

| | To my Ingenuous Friend, R. W. |

5 |

| | Les Amours |

8 |

| | To Amoret. The Sigh |

10 |

| | To his Friend, Being in Love |

11 |

| | Song: [Amyntas go, thou art Undone] |

12 |

| | To Amoret. Walking in a Starry Evening |

13 |

| | To Amoret Gone from him |

15 |

| | A Song to Amoret |

16 |

| | An Elegy |

17 |

| | A Rhapsodis |

18 |

| |

[viii]

To Amoret, of the Difference 'twixt him and other Lovers, >and what True Love is |

21 |

| | To Amoret Weeping |

23 |

| | Upon the Priory Grove, his Usual Retirement |

26 |

| | Juvenal's Tenth Satire Translated |

28 |

| Olor Iscanus. 1651. |

|

| | Ad Posteros |

51 |

| | To the ... Lord Kildare Digby |

53 |

| | The Publisher to the Reader |

55 |

| | Upon the Most Ingenious Pair of Twins, Eugenius

Philalethes and the Author of those Poems [by T. Powell, Oxoniensis] |

57 |

| | To my Friend the Author upon these his Poems [by I. Rowlandson, Oxoniensis] |

58 |

| | Upon the following Poems [by Eugenius Philalethes, Oxoniensis] |

59 |

| | Olor Iscanus. To the River Isca |

61 |

| | The Charnel-House |

65 |

| | In Amicum Foeneratorem |

68 |

| | To his Friend —— |

70 |

| | To his Retired Friend, An Invitation to Brecknock |

73 |

| | Monsieur Gombauld |

77 |

| | An Elegy on the Death of Mr. R. W., Slain in the late

Unfortunate Differences at Routon Heath, near Chester, 1645 |

79 |

| | Upon a Cloak lent him by Mr. J. Ridsley |

83 |

| | Upon Mr. Fletcher's Plays, Published 1647 |

87 |

| | Upon the Poems and Plays of the Ever-Memorable Mr. William

Cartwright

[ix] |

90 |

| | To the Best and Most Accomplished Couple —— |

92 |

| | An Elegy on the Death of Mr. R. Hall, Slain at Pontefract, 1648 |

94 |

| | To my Learned Friend, Mr. T. Powell, upon his Translation

of Malvezzi's Christian Politician |

97 |

| | To my Worthy Friend, Master T. Lewes |

99 |

| | To the Most Excellently Accomplished Mrs. K. Philips |

100 |

| | An Epitaph upon the Lady Elizabeth, Second Daughter to his Late Majesty |

102 |

| | To Sir William Davenant upon his Gondibert |

104 |

| Translations From Ovid. |

|

| | To his Fellow Poets at Rome, upon the Birthday of Bacchus |

106 |

| | To his Friends—after his Many Solicitations—Refusing to

Petition Cæsar for his Releasement |

109 |

| | To his Inconstant Friend, Translated for the Use of all

the Judases of this Touchstone Age |

112 |

| | To his Wife at Rome, when he was Sick |

115 |

| | Ausonii. Idyll vi. Cupido [Cruci Affixus] |

119 |

| | [Translations from Boethius]

[x] |

125 |

| | [Translations from Casimirus] |

144 |

| | The Praise of a Religious Life of Mathias Casimirus. In

Answer to that Ode of Horace, Beatus Ille Qui Procul Negotiis. |

152 |

| | Ad Fluvium Iscam |

157 |

| | Venerabili Viro, Praeceptori Suo Olim Et Semper

Colendissimo Magistro Mathaeo Herbert |

158 |

| | Praestantissimo Viro, Thomae Poëllo In Suum De Elementis

Opticae Libellum |

159 |

| | Ad Echum |

160 |

| Thalia Rediviva. 1678. |

|

| | To ... Henry Lord Marquis and Earl of Worcester, &c.

[by J. W.] |

163 |

| | To the Reader [by I. W.] |

167 |

| | To Mr. Henry Vaughan, the Silurist: upon These and his

Former Poems. [By Orinda] |

169 |

| | Upon the Ingenious Poems of his Learned Friend, Mr. Henry

Vaughan, the Silurist. [By Tho. Powell, D.D.] |

171 |

| | To the Ingenious Author of Thalia Rediviva [By N. W.,

Jes. Coll., Oxon.] |

172 |

| | To my Worthy Friend Mr. Henry Vaughan, the Silurist.

[by I. W., A.M., Oxon.] |

175 |

| Choice Poems On Several Occasions.

[xi] |

|

| | To his Learned Friend and Loyal Fellow-Prisoner, Thomas

Powel of Cant[reff], Doctor of Divinity |

178 |

| | The King Disguised |

181 |

| | The Eagle |

184 |

| | To Mr. M. L. upon his Reduction of the Psalms into Method |

187 |

| | To the Pious Memory of C[harles] W[albeoffe] Esquire, Who

Finished his Course Here, and Made his Entrance into

Immortality upon the 13 of September, in the Year of

Redemption, 1653 |

189 |

| | In Zodiacum Marcelli Palingenii |

193 |

| | To Lysimachus, the Author Being with him in London |

195 |

| | On Sir Thomas Bodley's Library, the Author Being Then in Oxford |

197 |

| | The Importunate Fortune, Written to Dr. Powel, of Cant[reff] |

200 |

| | To I. Morgan of Whitehall, Esq., upon his Sudden Journey

and Succeeding Marriage |

204 |

| | Fida; or, The Country Beauty. To Lysimachus |

206 |

| | Fida Forsaken |

209 |

| | To the Editor of the Matchless Orinda |

211 |

| | Upon Sudden News of the Much-Lamented Death of

Judge Trevers

[xii] |

213 |

| | To Etesia (for Timander); The First Sight |

214 |

| | The Character, to Etesia |

217 |

| | To Etesia Looking from her Casement at the Full Moon |

219 |

| | To Etesia Parted from Him, and Looking Back |

220 |

| | In Etesiam Lachrymantem |

221 |

| | To Etesia Going Beyond Sea |

222 |

| | Etesia Absent |

223 |

| Translations. |

|

| | Some Odes of the Excellent and Knowing [Anicius Manlius] |

224 |

| | Severinus [Boethius], Englished

The Old Man of Verona, out of Claudian |

236 |

| | The Sphere of Archimedes, out of Claudian |

238 |

| | The Ph[oe]nix, out of Claudian |

239 |

| Pious Thoughts And Ejaculations. |

|

| | To his Books |

245 |

| | Looking Back |

247 |

| | The Shower |

248 |

| | Discipline |

249 |

| | The Eclipse |

250 |

| | Affliction[xiii] |

251 |

| | Retirement |

252 |

| | The Revival |

254 |

| | The Day Spring |

255 |

| | The Recovery |

257 |

| | The Nativity |

259 |

| | The True Christmas |

261 |

| | The Request |

263 |

| | Jordanis |

265 |

| | Servilii Fatum, Sive Vindicta Divina |

266 |

| | De Salmone |

267 |

| | The World |

268 |

| | The Bee |

272 |

| | To Christian Religion |

276 |

| | Daphnis |

278 |

| Fragments And Translations. 1641-1661. |

287 |

| | From Eucharistica Oxoniensia (1641) |

289 |

| | From Of the Benefit we may get by our Enemies (1651) |

291 |

| | From Of the Diseases of the Mind and the Body (1651) |

293 |

| | From The Mount of Olives (1652) |

294 |

| | From Man in Glory (1652) |

298 |

| | From Flores Solitudinis (1654) |

299 |

| | From Of Temperance and Patience (1654) |

300 |

| | From Of Life and Death (1654) |

305 |

| | From Primitive Holiness (1654) |

307 |

| | From Hermetical Physic (1655)

[xiv] |

322 |

| | From Cerbyd Fechydwiaeth (1657) |

323 |

| | From Humane Industry (1661) |

324 |

| Notes To Vol. II |

329 |

| List Of First Lines |

355 |

[xv]

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

Recent inquiries into the life of Henry Vaughan

have added but little to the information already contained

in the memoirs of Mr. Lyte and Dr. Grosart.

I have, however, been enabled to put together a few

notes on this somewhat obscure subject, which may

be taken as supplementary to Mr. Beeching's Introduction

in Vol. I. It will be well to preface them

by reprinting the account of Anthony à Wood, our

chief original authority (Ath. Oxon., ed. Bliss, 1817, iv. 425):

"Henry Vaughan, called the Silurist from that

part of Wales whose inhabitants were in ancient times

called Silures, brother twin (but elder)[1] to Eugenius

Philalethes, alias Tho. Vaughan ... was born at

Newton S. Briget, lying on the river Isca,

commonly called Uske, in Brecknockshire, educated[xvi]

in grammar learning in his own country for six years

under one Matthew Herbert, a noted schoolmaster of

his time, made his first entry into Jesus College in

Mich. term 1638, aged 17 years; where spending

two years or more in logicals under a noted tutor,

was taken thence and designed by his father for the

obtaining of some knowledge in the municipal laws

at London. But soon after the civil war beginning,

to the horror of all good men, he was sent for home,

followed the pleasant paths of poetry and philology,

became noted for his ingenuity, and published several

specimens thereof, of which his Olor Iscanus was

most valued. Afterwards applying his mind to the

study of physic, became at length eminent in his own

country for the practice thereof, and was esteemed

by scholars an ingenious person, but proud and

humorous.... [A list of Vaughan's works

follows.] ... He died in the latter end of April

(about the 29th day) in sixteen hundred ninety and

five, and was buried in the parish church of Llansenfreid,

about two miles distant from Brecknock,

in Brecknockshire."

Anthony à Wood seems to have had some personal

acquaintance with the poet, for in his account of

Thomas Vaughan (Ath. Oxon. iii. 725) he says

that "Olor Iscanus sent me a catalogue of his

brother's works."[xvii]

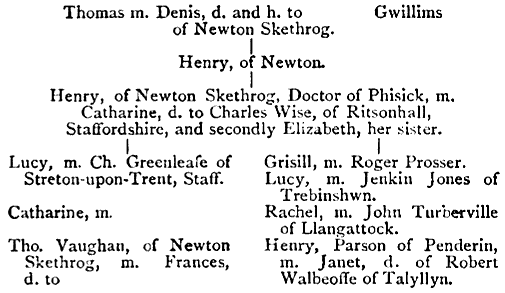

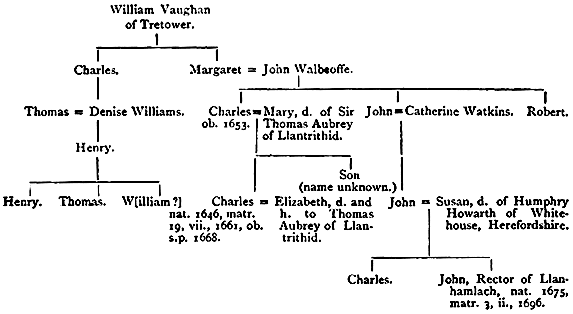

(a) THE VAUGHAN GENEALOGY.

Henry Vaughan's descent from the Vaughans of

Tretower, County Brecon, has been accurately traced

by Dr. Grosart and others. Little has been hitherto

known about his immediate family. Theophilus

Jones, in his History of Brecknockshire (1805-9), ii.

544, says: "Henry Vaughan died in 1695, aged 75,[2]

leaving by his first wife two sons and three daughters,

and by his second a daughter Rachel, who married John

Turberville. His grand-daughter, Denys, or Dyenis, a

corruption or abbreviation of Dyonisia, who was the

daughter of Jenkin Jones of Trebinshwn, by Luce

his wife, died single in 1780, aged 92, and is buried

in the Priory churchyard.[3] What became of the

remainder of his family, or whether they are extinct,

I know not." To this statement Mr. Lyte added

nothing but some errors, and Dr. Grosart nothing

but the following hypothesis:—

"I am inclined to think that William Vaughan,

censor of the College of Physicians, physician to

William IIId., was one of the sons of our worthy

mentioned by Mr. Lyte.... William Vaughan's

'age 20' in 1668 represents 1648 as the birth-date,[xviii]

and that fits in with the love-verse of the Poems

of 1646."

Mr. G. T. Clark, in his Genealogies of Glamorgan,

p. 240, gives the following account:—

Henry [Vaughan], ob. 1695, æt. 75, father by

first wife of (1) a son, s. p.; (2) Lucy ob. 29 Aug.,

1780, æt. 92,[4] m. Jenkin Jones of Trebinshwn. Their

d. Denise Jones, died single, 1780, æt. 92. By second

wife (3) Rachel, m. John Turberville; (4) Edmund;

(5) Alexander, ob. 1622 [!], s. p.; (6) Catharine, m.

Wm. Harris; (7) Mary, m. John Walbeoffe of

Llanhamlach; (8) Elizabeth, m. John Arnold; (9)

Frances, m. Wm. Johns of Cwm Dhu.

Unfortunately Mr. Clark is unable to remember

his authority for this pedigree. I have found another,

which differs from it in many ways, and is exceedingly

interesting, inasmuch as it gives, for the first

time, the names of Henry Vaughan's two wives, who

appear to have been sisters. It is in a volume of

Brecknockshire Pedigrees collected by the Welsh

Herald, Hugh Thomas, and now amongst the

Harleian MSS. Hugh Thomas was born and lived

hard by Llansantffread, and must have known

Vaughan and his family personally.

[xix]

PEDIGREE OF VAUGHAN OF TRETOWER AND NEWTON

(From Harl. MS. 2289, f. 81.)

It will be observed that neither Mr. Clark's pedigree

nor Hugh Thomas' agrees with the number of children

assigned to each marriage by Theophilus Jones, and

that neither of them helps out Dr. Grosart's hypothesis

that Dr. William Vaughan was a son of the

poet. Mr. W. B. Rye (Genealogist, iii. 33) has

made it appear likely that this Dr. Vaughan, who

married Anne Newton, of Romford in Essex, belonged

to a branch of the Vaughans who had been

settled in Romford since 1571.

I now proceed to confirm and illustrate the pedigrees

by giving such further facts concerning

Vaughan's immediate family as I have been able[xx]

with Miss Morgan's assistance, to glean. I can trace

no family of Wises in Staffordshire so early as the

seventeenth century, nor any place in that county

called Ritsonhall. It is possible that the R. W. of

the Elegy (vol. ii., p. 79, note) may have been a Wise,

and also that the connection between Vaughan and the

Staffordshire Egertons may have been through this

family (vol. ii., p. 294, note). Vaughan's first wife

Catharine was probably dead before 1658. Thomas

Vaughan, in his diary (MS. Sloane, 1741, f. 106 (b)),

makes mention in that year of "eyewater made at

the Pinner of Wakefield by my dear wife and my

Sister Vaughan, who are both now with God." The

second wife, Elizabeth, survived her husband.

Administration of his goods was granted to her as

the widow of an intestate in May, 1695.[5] The fine

old manor-house at Newton was pulled down by a

stupid land-agent within the memory of man, but a

stone has been found built into the wall of a house

half-a-mile from the site, bearing the inscription[xxi]

"HVE, 1689." This may well stand for H[enry

and] E[lizabeth] V[aughan]. Newton probably

passed to the poet's eldest son Thomas and his

wife Frances.[6] Of their descendants, if any, we

know nothing. There was a William Vaughan of

Llansantffread who, later than 1714, married Mary

Games of Tregaer in Llanfrynach. But this was

probably a Vaughan not of Newton, but of Scethrog,

also in Llansantffread (cf. footnote to p. xxv.

below.) In 1733 William Vaughan was churchwarden

of Llanfrynach. In 1740 William Vaughan

of Tregaer was high sheriff of Brecknock. In

1760 Tregaer had passed by purchase to a Mr.

Phillips. The registers of Llanfrynach from 1695-1756

are now lost. Lucy Greenleafe and her sister

Catharine are quite obscure. One of them may

have been the niece who was living with Thomas

Vaughan when news came from the country in 1658

of his father's death (MS. Sloane, 1741, f. 89 (b)). Of

the second family, Henry became Rector of Penderin

in 1684, and vacated the living, probably through

death, in 1713. A tablet to his memory hung during[xxii]

the present century in the church at Penderin, but

when the church was restored the tablets were taken

down and buried under the tiles of the chancel. His

wife, a Walbeoffe of Talyllyn, belonged to the same

family as the Walbeoffes of Llanhamlach (vol. ii.,

p. 189, note). The eldest girl, Grisill, married Roger

Prosser. The Prossers were the younger branch of a

Brecknockshire family who had become sadlers and

mercers in Brecon. Many of their tombs are in the

Priory church, but Theophilus Jones states that by

his time they were extinct. Grisill Prosser was

married a second time, in 1709, to Morgan Watkins,

an attorney, and was buried on August 21, 1737.

The second girl, Lucy, married Jenkin Jones of

Trebinshwn, a cousin of Colonel Jenkin Jones, the

local Parliamentary leader. Her daughter, Denise

Jones, died single in 1780, as Theophilus Jones

states, and her tombstone in the Priory church

records her descent. The third girl, Rachel, married

John Turberville, one of the Turbervilles of Llangattock,

who claimed kinship with the Elizabethan

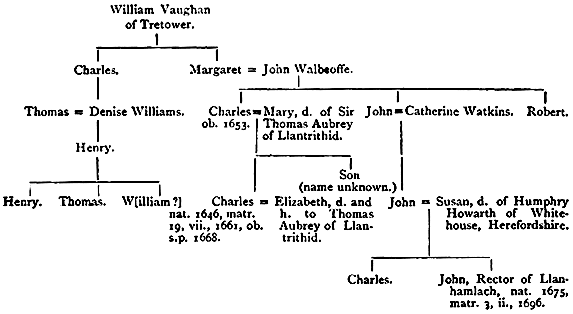

poet of that name. The following pedigree shows

the descendants of the three daughters of Henry

Vaughan's second marriage, so far as they can be

traced.[7]

[xxiii]

[xxiv]

It will be seen that I can give no evidence of

the existence of any living descendants of Henry

Vaughan.

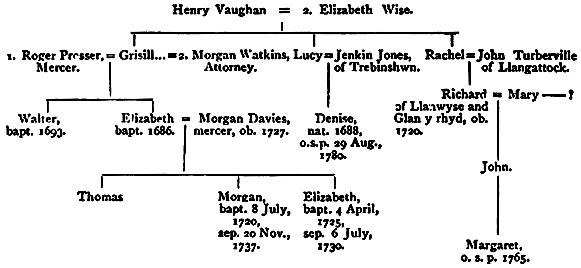

Henry's grandfather, Thomas Vaughan, a younger

son of Charles Vaughan of Tretower, seems to have

come into the possession of Newton through his

marriage with an heiress of the family of Gwillims or

Williams. Newton, or in Welsh Trenewydd, is a

farm of about 200 acres in the manor or lordship, and

near the village of Scethrog, both being in the parish

of Llansantffread and hundred of Penkelley. Williams

is a common name in Breconshire, and I cannot trace

the descent of Thomas Vaughan's wife. In the

sixteenth century Newton belonged to a family who

finally settled on the name of Howel, ap Howell or

Powell.[8] The last of these is described on his tombstone

in Llansantffread Church as "David Morgan

David Howel, who married ... William of Llanhamoloch:

and they had issue one daughter called

Denys. He died 2nd June, 1598." Perhaps Newton

passed in some way from David Morgan David Howel

to his wife's family, and so to Thomas Vaughan,

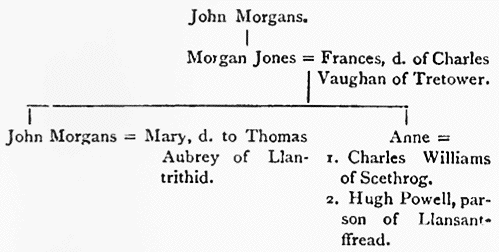

who married Denise Gwillims. Theophilus Jones

(ii. 538) records that at a later date other Williams's,[xxv]

also apparently connected with Llanhamlach, were

succeeded by other Vaughans at Scethrog, hard by

Newton. His account is that David Williams,

youngest brother of Sir Thomas Williams of Eltham,

married a daughter of John Walbeoffe of Llanhamlach

(cf. pedigree in vol. ii., p. 189, note), and bought

Scethrog. Their son Charles died without issue,

and the property passed to his wife Mary (Anne

in Harl. MS., 2289, t. 39; cf. vol. ii., p. 204, note),

the daughter of Morgan John of Wenallt....

She afterwards married Hugh Powell, clerk, parson

of Llansanffread and precentor of St. David's, and

her daughter Margaret married Charles Vaughan,

son to Vaughan Morgan of Tretower.[9]

A trace of Thomas Vaughan is probably preserved

in a window-head from the old church of Llansantffread,

now destroyed, which has the inscription:—

T. V. may stand for T[homas] V[aughan].[10]

[xxvi]

Of Henry Vaughan, the poet's father, very little is

known. His name appears in a list of Breconshire

magistrates for 1620. And we learn from Thomas

Vaughan's diary in Sloane MS. 1741, f. 89 (b), that

he died in August 1658.

The only additional definite fact which I can here

record of the poet himself is that in 1691 he entered

a caveat against any institution to the vicarage of

Llandevalley, he claiming the next presentation under

a grant from William Winter, Esq.[11] Mr. Rye has

shown that the specimen of handwriting facsimiled

by Dr. Grosart in his edition of Henry

Vaughan's Works cannot possibly be the poet's.

The signatures, however, on the margin of a copy

of Olor Iscanus, once in the library of Lady Isham,

might be genuine.

(b) VAUGHAN AND JESUS COLLEGE, OXFORD.

Anthony à Wood's statement as to Vaughan's

residence at Jesus College, Oxford, has been generally

accepted, but I venture to doubt it on the following grounds:—

(1) Vaughan's name does not occur in the University

Matriculation Register, although his brother[xxvii]

Thomas Vaughan is duly entered as matriculating

from Jesus on 14th December, 1638. The only

College records which help us are the Battel-books

for 1638 and 1640. That for 1639 is unfortunately

missing. The Rev. Llewellyn Thomas kindly

informs me that he can only trace one undergraduate

Vaughan in the two books in question. The Christian

name is not given, but I think that we must assume

it to be Thomas.

(2) Vaughan does not describe himself on any

title-page as of Jesus College; nor does he ever speak

of himself as an Oxford man. This omission is the

more noticeable as he would naturally have done so

in the lines Ad Posteros (vol. ii., p. 51), and might

well have done so in those On Sir Thomas Bodley's

Library, the Author being then in Oxford (vol. ii., p. 197).

(3) Anthony à Wood cannot be depended on. He

describes Thomas Carew, for instance, as of C.C.C.,

whereas he was a most certainly of Merton. And

there was another Henry Vaughan of Jesus, who

may have been confused with the poet. This Henry

Vaughan, a son of John Vaughan of Cathlin,

Merionethshire, matriculated at Oriel on July 4,

1634. He afterwards became a Scholar and Fellow

of Jesus, taking his B.A. in 1637 and his M.A. in

1639. In 1643 he became vicar of Penteg, co. Monmouth,

and died at Abergavenny in 1661.

(Wood, Ath. Oxon., iii. 531; Foster, Alumni Oxon.)[xxviii]

(4) The only confirmation of Anthony à Wood's

statement is the poem (vol. ii., p. 289) taken by Dr.

Grosart from the Eucharistica Oxoniensia (1641),

and signed "H. Vaughan, Jes. Col." If I am

right, this may be by Vaughan's namesake. He has

indeed another poem in that volume signed "Hen.

Vaugh., Jes. Soc." but that is in Latin, and it is

not unexampled for one man to contribute more than

one poem, especially in different tongues, to such

collections. Or it may be by Herbert Vaughan, who

was a Gentleman-commoner of the College in 1641,

and has, with Henry Vaughan the Fellow, verses in

the προτέλεια

Anglo Batava of the same year.

(c) VAUGHAN IN THE CIVIL WAR.

There are several passages which make it probable

that Vaughan, like his brother Thomas, bore arms on

the King's side in the Civil War. The most important

is in the poem To Mr. Ridsley (vol. ii., p. 83),

where he speaks of the time

"when this juggling fate

Of soldiery first seiz'd me."

In the same poem he mentions

"that day, when we

Left craggy Biston and the fatal Dee."

"Craggy Biston" is clearly Beeston Castle, one of

the outlying defences of Chester, situated on a steep[xxix]

rock not very far east of the Dee. This castle was

besieged on several occasions during the Civil War,

especially during the campaign of 1645, when

Chester was also besieged by the Parliamentarians.[12]

Between Beeston and the Dee was fought, on

September 24, 1645, the battle of Rowton Heath,

after which Charles the First, who had hoped to raise

the siege of Chester, was obliged to retreat to

Denbigh.[13] The following lines from Vaughan's

Elegy on Mr. R. W. (vol. ii., p. 79), who fell in

that battle, seem to have been written by an eye-witness:

"O that day

When like the fathers in the fire and cloud

I miss'd thy face! I might in ev'ry crowd

See arms like thine, and men advance, but none

So near to lightning mov'd, nor so fell on.

Have you observ'd how soon the nimble eye

Brings th' object to conceit, and doth so vie

Performance with the soul, that you would swear

The act and apprehension both lodg'd there?

Just so mov'd he: like shot his active hand

Drew blood, ere well the foe could understand.

But here I lost him."

This appears to me pretty conclusive evidence;

against it, however, must be set the passage on the[xxx]

Civil War in the autobiographical poem Ad Posteros

(vol. ii., p. 51).

Vixi, divisos cum fregerat haeresis Anglos

Inter Tysiphonas presbyteri et populi.

His primum miseris per amoena furentibus arva

Prostravit sanctam vilis avena rosam.

Turbarunt fontes, et fusis pax perit undis,

Moestaque coelestes obruit umbra dies.

Duret ut integritas tamen, et pia gloria, partem

Me nullam in tanta strage fuisse, scias;

Credidimus nempe insonti vocem esse cruori,

Et vires quae post funera flere docent.

Hinc castae, fidaeque pati me more parentis

Commonui, et lachrimis fata levare meis;

Hinc nusquam horrendis violavi sacra procellis,

Nec mihi mens unquam, nec manus atra fuit.

The natural interpretation of this certainly is that

Vaughan took no share in the disturbances of his

time, except to grieve over them in retirement. Yet,

in the first place, the lines may have been written

before he took up arms in 1645, and, in the second,

they may only mean that he had no share in bringing

about the troubles of England, or in shedding

innocent blood. Similarly when elsewhere, as in

Abel's Blood (vol. i. p. 254), and in the prayer to

be quoted below, he expresses horror of blood-guiltiness,

this need not necessarily be taken as

extending to the man who fights in a righteous cause.

Miss Morgan, I may add, suggests that Vaughan

was at Rowton Heath, not as a combatant, but as a[xxxi]

physician. The description which he gives of the

battle reads like that of a man who saw it from some

commanding point of view, but was not himself

engaged. I think it not improbable that Vaughan

was one of the garrison of Beeston Castle, which is

described to me as "a sort of grand stand for the

battle-field." Beeston Castle was invested by the

Parliamentarians in the course of September 1645.

On the approach of Charles the troops were drawn off

on 19th September to Chester.[14] Charles no doubt

took the opportunity to strengthen the garrison. After

Rowton Heath Beeston Castle was again besieged,

and on November 16th it surrendered. The garrison

were allowed to march across the Dee to Denbigh.

I think that this winter ride from the fallen fortress is

the one described by Vaughan in the poem to Mr.

Ridsley. It is the more probable that Vaughan took

part in this campaign of 1645, in that Charles's

force was largely recruited from Wales. After the

battle of Naseby on June 14th, the King had

marched through Wales, collecting such levies as he

could. He was in Brecon on August 5th.[15] It is

quite possible that Vaughan, whose kinsman Sir

William Vaughan was in command of a brigade,

volunteered on this occasion. From Brecon Charles

marched through Radnorshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire,

Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Yorkshire, and

so to Oxford. In September he set out again, and[xxxii]

after some delay at Hereford and Raglan, finally

made for Chester.

It is just conceivable that it is to some occasion in

this campaign that Vaughan refers when he calls Dr.

Powell his "fellow-prisoner" (vol. ii., p. 178). The

poet may even have been the Captain Vaughan whose

name appears in the official list of prisoners taken at

Rowton Heath.[16] Powell's name is not there, but

then the list does not profess to be complete. But on

the whole I think that Vaughan and Powell were

only fellow-prisoners in the Platonic sense of imprisonment

in the flesh, and even if a literal imprisonment

is intended, it may have been due to some act of

persecution which Vaughan had to suffer as a

Royalist at a later date. There is in The Mount of

Olives (1652) a Prayer in Adversity and Troubles

occasioned by our Enemies (Grosart, vol. iii., p. 75),

which, if it is to be taken—I think it is not—as

autobiographical, seems to show that, at least for a

time, he lost his estate. The prayer runs: "Thou

seest, O God, how furious and implacable mine

enemies are: they have not only robbed me of that

portion and provision which Thou hast graciously

given me, but they have also washed their hands in

the blood of my friends, my dearest and nearest

relations. I know, O God, and I am daily taught

by that disciple whom Thou didst love, that no

murderer hath eternal life abiding in him. Keep me,[xxxiii]

therefore, O my God, from the guilt of blood, and

suffer me not to stain my soul with the thoughts of

recompense and vengeance, which is a branch of Thy

great prerogative, and belongs wholly unto Thee.

Though they persecute me unto death, and pant after

the very dust upon the heads of Thy poor, though

they have taken the bread out of Thy children's

mouth, and have made me a desolation; yet, Lord,

give me Thy grace, and such a measure of charity as

may fully forgive them."

It may have been during some such time of trouble,

or imprisonment, if imprisonment there was, that

Vaughan's wife lived with Thomas Vaughan, as will

be seen below, in London.

(d) THOMAS VAUGHAN.

It has not been thought necessary to reprint in this

edition of Henry Vaughan's poems the scanty

English and Latin verses of his brother, Thomas

Vaughan. They may be found, together with verses

by Virgil and Campion ascribed to him, in vol. ii. of

Dr. Grosart's Fuller Worthies edition. But some

account of so curious a person will not be out of place.[xxxiv]

As for his brother, our chief authority is Anthony

à Wood (Ath. Oxon., iii. 722), who says that he was

the son of Thomas Vaughan of Llansantffread,[17] that

he was born in 1621, educated under Matthew

Herbert and at Jesus College, Oxford, of which he

became Fellow, took orders and received [in 1640]

the living of Llansanffread from his kinsman, Sir

George Vaughan [of Fallerstone, Wilts]. He lost

his living in the unquiet times of the Civil War,

retired to Oxford, and became an eminent chemist,

afterwards moving to London, where he worked

under the patronage of Sir Robert Murray. He was

a great admirer of Cornelius Agrippa, "a great

chymist, a noted son of the fire, an experimental

philosopher, a zealous brother of the Rosicrucian

fraternity ... neither papist nor sectary, but a

true resolute protestant in the best sense of the

Church of England." In the great plague he fled

with Murray from London to Oxford, and thence

went to the house of Samuel Kem at Albury, where

he died on February 27, 1665/6, of mercury

accidentally getting into his nose while he was

operating. He was buried at Albury on March 1st.

Writing in 1673, Anthony à Wood gives a list of his

alchemical and mystical treatises published between

1650 and 1655. Of these he had received a list from

Olor Iscanus (Henry Vaughan). They all bear the[xxxv]

name of Eugenius Philalethes, except the Aula

Lucis (1652), which was issued as by S. N., i.e.

[Thoma]S [Vaugha]N. Some of these pamphlets

contain Vaughan's share of a vigorous and scurrilous

controversy with Henry More, the Platonist.

Anthony à Wood distinguishes from Vaughan

another Eugenius Philalethes, author of the Brief

Natural History (1669), also one Eirenaeus Philalethes,

author of Ripley Redivivus and other works,

and Eirenaeus Philoponos Philalethes, author of The

Marrow of Alchemy (1654-5).[18]

A few facts, from well-known sources, may be added

to Anthony à Wood's account. The University

Registers show that "Thos. Vaughan, son of

Thomas of Llansanfraid, co. Brecon, pleb., matriculated

from Jesus College on 14 Dec, 1638, aged 16."[xxxvi]

He took his B.A. on 18 Feb., 1641/2, but does

not appear to have taken his M.A., though he

became Fellow of his College (Foster, Alumni

Oxon.). John Walker (Sufferings of the Clergy

(1714), p. 389) states that he was ejected from his

living on the charges of "drunkenness, immorality,

and bearing arms for the King."[19] This must have

been in 1649, under the Act for the Propagation of

the Gospel in Wales. There exists a letter from

Thomas Vaughan to a friend in London, dated from

"Newtown, Ash Wednesday, 1653;"[20] and it appears

from Jones' History of Brecknockshire (ii., 542), that

at one time he lived with his brother Henry there.

The allusions to Henry More, to Murray, and to the

Isis and Thames seem to show that he is the Daphnis

of his brother's Eclogue (vol. ii., p. 278). No trace

of his death or burial can however be now found at

Albury. Mr. Gordon Goodwin points out to me

that Dr. Samuel Kem was a somewhat notorious

character (Dict. Nat. Biog., s.v. Kem): perhaps this

friendship, together with the personal confession

quoted below, throws light on the charges which

lost Vaughan his living. On the other hand[xxxvii]

Anthony à Wood speaks well of him, and the

tone of his writings bears out this more kindly

judgment, at any rate so far as his later years are

concerned.

What has been said fairly well exhausted the

available information on Thomas Vaughan until a

few years ago, when Mr. A. E. Waite discovered in

Sloane MS. 1741 a valuable manuscript of his, containing

amongst other things a number of autobiographical

memoranda. He printed some extracts

from this in the preface to an edition of some of The

Magical Writings of Thomas Vaughan (Redway,

1888), and has been kind enough to furnish me with

a reference to the MS. itself, which I have carefully

examined. It bears the title Aqua Vitae non Vitis,

and the inscription "Ex libris Thomas et Rebecca

Vaughan, 1651, Sept. 28. Quos Deus coniunxit quis

separabit?" The contents are partly personal

jottings and records of dreams, partly alchemical

formulae. They appear to cover the period 1658-1662.

We learn from them the following facts:—Vaughan

was married on September 28, 1651, to a

lady named Rebecca (f. 106 (b)). With her and his

"Sister Vaughan" he lived and studied alchemy at

the Pinner of Wakefield.[21] He had previously lodged

at Mr. Coalman's in Holborn (f. 104 (b)). His wife

died on Saturday, April 17, 1658, and was buried at

[xxxviii]

Mappersall, in Bedfordshire (f. 106 (b)).[22] In 1658 his

father and his brother W. were both dead, and he

mentions the news of his father's death coming to

his niece in a letter from the country (f. 89 (b)). On

April 9, 1659, he saw his brother H. in a dream.

On 16 July, 1658, he was living at Wapping

(f. 103 (b)), and at an earlier period at Paddington.

There is an inventory of his wife's goods left at Mrs.

Highgate's, and mention of a Mr. Highgate and a

Sir John Underhill (f. 107). He names his cousin,

Mr. J. Walbeoffe, with whom he had some money

transactions (f. 18), and speaks of "a certain person

with whom I had in former times revelled away my

years in drinking" (f. 103). Perhaps this also was

John Walbeoffe, on whom see vol. ii., p. 189, note.

The alchemical formulae and receipts are interesting.

In one place (f. 12) Vaughan announces the discovery

of the "Extract of Oil of Halcaly," which he had

previously found in his wife's days and had lost

again. This he calls "the greatest joy I can ever

have in this world after her death." He seems to

have regarded it as the key to an universal solvent.

Nearly every receipt is followed by his and his wife's[xxxix]

initials in the form T. R. V. or T. V. R., and by some

expression of devotion to her or of religious piety.

I now come to the remarkable statements made

with respect to Thomas Vaughan in the Mémoires

d'une ex-Palladiste, now in course of publication by

Miss Diana Vaughan. Miss Vaughan is a lady who

has created a considerable sensation in Paris. Her

own account of herself is that she was brought up as

a worshipper of Lucifer, and was for some years a

leading spirit amongst certain androgynous lodges of

Freemasons, in which the worship of Lucifer is

largely practised. She has now, owing to the direct

interposition of Joan of Arc, become a Catholic, and

has made it her mission to combat Luciferian Freemasonry

in every way. Her Memoirs are partly a[xl]

biography, partly an account of this cult.[23] Miss

Vaughan claims to be a great-grand-daughter of

Thomas Vaughan's. She declares him to have been

a Luciferian, Grand-master of the Rosicrucian order,

and the founder of modern Freemasonry; and gives[xli]

an exhaustive account of his career on the authority

of family archives. The following paragraphs contain

the substance of her narrative, the "legend of

Philalethes," as it was told to Miss Vaughan by her

father and her uncle, who were intimate friends of

Albert Pike.

The traditional accounts of Thomas Vaughan, says

Miss Vaughan, contain serious errors. The dates

of his birth and of his death, and the pseudonym

under which he wrote are all incorrectly stated[24]

(p. 110). He was born in Monmouth in 1612,

being two years the elder of his brother Henry.

The two boys were brought up at Oxford, after[xlii]

their father's death, by their uncle, Robert Vaughan

the antiquary,[25] and entered at Jesus College

(p. 114). In 1636, at the age of 24, Thomas

Vaughan went to London, and became the disciple of

Robert Fludd, who was a Rosicrucian (p. 148). The

real nature of the Rosicrucians has hitherto been a

mystery. They were in reality Luciferians, and

carried on in secret during the seventeenth century

that warfare against Adonai, the god of the Catholics,

out of which had already sprung Wiclif, Luther, and

the Reformation, and out of which was some day to

spring, more deadly and more dangerous still, Freemasonry.

The Fraternity of Rosie-Cross was

founded by Faustus Socinus in 1597. He was

succeeded as head of it by Caesar Cremonini (1604-1617),

Michael Maier (1617-1622), Valentin Andreae

(1622-1654), and Thomas Vaughan (1654-1678).[26]

When Thomas Vaughan first came to London in

1636, Valentin Andreae was Summus Magister of

the Fraternity, and amongst its leading members

were Robert Fludd and Amos Komenski, or

Comenius (pp. 129-148). Robert Fludd initiated

Thomas Vaughan into the lower degrees of the[xliii]

Golden Cross (p. 148), and sent him to Andreae at

Calw, near Stuttgart, with a letter in which he prophesied

for him a miraculous future (p. 163). After

this visit to Germany, Vaughan returned to London,

and after Fludd's death, in 1637, undertook in 1638

his first visit to America. In many of his writings

he speaks as a Christian minister, and at this time he

probably passed as a Nonconformist (p. 164). He

was back in London early in June, 1639 (p. 165), and

in the same year visited Denmark, and made a report

to Komenski on the mysterious golden horn found at

Tondern in that country (p. 166). In 1640 Vaughan

received from Komenski the first initiation of the

Rosie Cross, and chose the pseudonym of Eirenaeus

Philalethes.[27] He now became exceedingly active,

going and coming upon the face of the earth. When[xliv]

in England, he divided his time between Oxford and

London (p. 167). Between 1640 and 1644 he

visited Hamburg, the Netherlands, Italy and

Sweden (pp. 171-174). It was at this period that he

conceived the design of obtaining a far wider circulation

than they had yet met with for the ideas of

Faustus Socinus. Some of the Rosicrucians were

already "accepted masons." Vaughan determined

to capture the vast organization of craft masonry by

permeating the lodges with Luciferianism. His

associate in this task was Elias Ashmole, with whose

aid, a few years later, he composed the degrees of

Apprentice (1646), Companion (1648), and Master

(1649) (pp. 142, 169-175, 197-206). The Civil War

had now approached. Oliver Cromwell was a freemason,

a Rosicrucian, and a friend of Vaughan's

(p. 176). With the execution of Laud came the

crisis of Vaughan's life, his initiation into the highest

degree of Rosie Cross by the hands of Lucifer himself.

It took place in this wise. At the last moment

Vaughan was substituted for the intended executioner

of Laud.[28] He had prepared a sacramental cloth which

he soaked in the martyr's blood, and on the same

night he sacrificed the relic to Lucifer. The divinity[xlv]

appeared, consecrated Vaughan as Magus, named

him as the next Summus Magister of the Fraternity,

and signed a pact, granting him thirty-three years

more life, at the end of which he should be borne

away from earth without death (p. 177). In 1645

Vaughan wrote, but did not yet publish, his most

important treatise, the Introitus Apertus ad Occlusum

Regis Palatium. In 1645, still following the direct

command of Lucifer, he departed for America. Here

he met the apothecary George Starkey, and in his

presence performed the alchemical feat of making gold

(p. 179).[29] Here, too, he lived amongst the Lenni-Lennaps,

where he was united to the demon Venus-Astarte

in the form of a beautiful woman, who after

eleven days bore him a daughter. This girl was brought

up among the Lenni-Lennaps under the name of Diana

Wulisso-Waghan, and became Miss Diana Vaughan's

great-great-grandmother (p. 181). In 1648 Vaughan

returned to England, and after composing the

masonic degree of Master in 1649 (p. 197), he began

[xlvi]

the publication of a series of alchemical and, in

reality, Luciferian writings. In 1650 appeared the

Anthroposophia Theomagica and the Magia Adamica,

in 1651 the Lumen de Lumine; in 1652 the Aula

Lucis (p. 211). In 1654 Valentin Andreae died, and

Vaughan succeeded him as Summus Magister of the

Rosie Cross, the event being announced to him by

the homage of three demons, Leviathan, Cerberus,

and Belphegor (p. 214). In 1655 he published his

Euphrates, and in 1656 made his head-quarters at

Amsterdam or Eirenaeopolis. In 1659 came his

Fraternity of R. C.; in 1664 his Medulla Alchymiae.[30]

In 1666 he exhibited the philosopher's stone to

Helvetius at La Haye and converted him to

occultism: in 1667 he at last resolved to publish his

Opus Magnum, the Introitus Apertus, already

written in 1645 (p. 215). In 1668 this was followed

by the Experimenta de Praeparatione Mercurii

Sophici and the Tractatus Tres (p. 236). The time

was now approaching when Vaughan, in fulfilment of

the pact of 1644, must disappear from earth. He

named Charles Blount as his successor (p. 237), and

was granted a magical vision of his grandson, the

child of Diana Wulisso-Waghan and a Lenni-Lennap

(p. 239). He finished his Memoirs, published

the Ripley Revised[31]

and the Enarratio Methodica

trium Gebri Medicinarum,

[xlvii]

left his poems to his

brother Henry, who published them in the next year

as the Thalia Rediviva,[32] and on March 25, 1678,

disappeared in the company of Lucifer Dieu-Bon

himself (p. 240). This event is vouched for, not

only by a written statement of Henry Vaughan

(p. 114), but also by the existence in a masonic

triangle at Valetta of a magical talisman into which,

when properly evoked, the spirit of Philalethes

enters and records his glorious end for the edification

of the Luciferians present[33] (p. 243).

I fear that I have taken Miss Vaughan with undue

seriousness. Her account of Thomas Vaughan is not

only unsupported by direct evidence,[34] but much of it[xlviii]

is of a character which we should not be justified in

accepting, even were direct evidence forthcoming.

And it is all discordant with the little that we do

happen to know of Thomas Vaughan from other

sources. The whole thing is, in fact, a pretty obvious

romance of very modern fabrication. It appears to

have been compiled from such information as to the

alchemical and mystical writers of the seventeenth

century as was within the reach of Albert Pike

and the brothers Vaughan about the year 1870.[xlix][35]

It is always better to explain than to refute an error;

and the nature of the Luciferian tradition of Thomas

Vaughan is pretty clearly shown by the fact that it is

not corroborated in a single particular by any of the

new facts about him that have come to light since this

probable date of its composition.[36] The fabricator put

Thomas Vaughan's birth-place in Monmouth instead

of Brecon, because he had never seen Dr. Grosart's

Fuller Worthies Edition of Henry Vaughan. He

makes no mention of any of the facts contained in

Sloane MS. 1741, because that MS. was still

unknown. And, most fatal of all, he puts Thomas

Vaughan's birth in 1612 instead of 1621-2, because

Foster's Alumni Oxonienses being yet unpublished,

he was ignorant of the record of that date preserved

in the University Registers. But we can go

a step further. We can confute him, not only by

pointing to the books he did not use, but by pointing

to those he did. It has already been shown that the

ascription to Vaughan of the English translation of

Maier's Themis Aurea is due to a misunderstanding[l]

of a phrase used by Anthony à Wood. The Athenae

Oxonienses then was one source of the compilation.

Another was the Histoire de la Philosophie

Hermétique, written by Lenglet-Dufresnoy in 1742.

Here is the proof. Miss Vaughan supports her

statement as to the birth-date in 1612 by a quotation

from the Introitus Apertus, in which the writer

states it to have been composed "en l'an 1645 de

notre salut, et le trente-troisième de mon age." This

she professes to translate from the editio princeps

published by Jean Lange in 1667. As a matter of

fact it is taken from the version given in Lenglet-Dufresnoy's

book. And Lenglet-Dufresnoy followed,

not the edition of 1667, but the later edition published

by J. M. Faust at Frankfort in 1706. In this

the words are "trigesimo tertio," whereas in the

editio princeps they are "vicesimo tertio," and in

W. Cooper's English translation of 1669, "in the 23rd

year of my age," thus bringing the date of the birth

of Eirenaeus Philalethes not to 1612, but to 1622.

The "legend of Philalethes" need detain us no

longer. Miss Vaughan's narrative is a very insufficient

basis for regarding the pious minister and

mystic which Thomas Vaughan appears to have

been as a secret enemy of Christianity and a worshipper of Lucifer.

But when the legend is set aside, there still remain

certain questions suggested by it which may be considered

without much reference to the statements of[li]

Miss Vaughan. Was Thomas Vaughan a Rosicrucian?

And was he, admittedly the author of a

series of tracts under the name of Eugenius Philalethes,

also the author of those which bear the name of

Eirenaeus Philalethes? The first question is, I am

afraid, insoluble, until it has been decided whether

the Fraternity of R. C. ever had an actual existence.

Anthony à Wood states that Thomas Vaughan was a

zealous Rosicrucian, but probably Anthony à Wood

took the term in the general sense of mystic and

alchemist. On the other hand Vaughan himself, in

his preface to the English translation of the Rosicrucian

manifestoes, seems to disavow any personal

acquaintance with the members of the fraternity.

Even this is not conclusive, for the Rosicrucian rule,

as given in the Laws of the Brotherhood, published

by Sincerus Renatus in 1710,[37] obliges the

members to deny their membership.

There is more material for the discussion of the

second question, but I do not know that it is more

possible to come to a definite conclusion. The

personality of the anonymous adept who took

the name of Eirenaeus Philalethes was shrouded in

mystery even to his contemporaries. The fullest

account given of him on any of his title-pages is on

that of the Experimenta de Praeparatione Mercurii

Sophici (1668), which is said to be "ex manuscripto[lii]

Philosophi Americani alias Eyrenaei Philalethis,

natu Angli, habitatione Cosmopolitae."[38] We have

also the description given by George Starkey, or

whoever it was, in the Marrow of Alchemy (1654-5),

p. 25. Starkey says:—

"His present place in which he doth abide

I know not, for the world he walks about,

Of which he is a citizen; this tide

He is to visit artists and seek out

Antiquities a voyage gone and will

Return when he of travel hath his fill.

"By nation an Englishman, of note

His family is in the place where he

Was born, his fortune's good, and eke his coat

Of arms is of a great antiquity;

His learning rare, his years scarce thirty-three;

Fuller description get you not from me."

[liii]

Starkey gives the age of Eirenaeus Philalethes as

33 in 1654. This precisely confirms the writer's own

statement in the earlier editions of the Introitus

Apertus that he was 23 in 1645, and fixes the birth-date

as 1621 or 1622. Now this agrees remarkably

with the birth-date ascertained from other sources of

Thomas Vaughan. But Thomas died in 1666, and

it is usually asserted that Eirenaeus Philalethes lived

until at least 1678. Miss Vaughan states that he

must have been alive in that year, because he then

published the Ripley Revived, and the Enarratio

Trium Gebri Medicinarum. She declares that the

author of the Enarratio mentions the pains taken

about that edition (p. 240). I do not find any prefatory

matter in this book at all. There is a preface

to the Ripley Revived, but this was written long

before 1678, for it mentions the Introitus Apertus,

published in 1667, as still in manuscript. Neither

Jean Lange, the editor of the Introitus Apertus of

1667, writing 9th December, 1666, nor William

Cooper, the editor of the English translation[liv][39]

of 1669, writing 15th September, 1668, know

whether the author is still alive. In fact he cannot

be shown to have outlived Thomas Vaughan, for there

is no proof that the adept who showed the philosopher's

stone to Helvetius on December 27th, 1666,[40]

was the same as he who showed it to George

Starkey many years before. I will briefly enumerate

a few other links which connect Eirenaeus Philalethes

with Thomas Vaughan. A German translation of

the Introitus Apertus, published at Hamburg under

the title of Abyssus Alchemiae (1704), is said on the

title-page to be "von T. de Vagan." Miss Vaughan

states that a similar translation of the first of the

Tres Tractatus, published at Hamburg in 1705, also

bears this name (p. 237), and this is borne out by

Lenglet-Dufresnoy (iii. 261-6), who speaks of a

French MS. of the Tres Tractatus inscribed "par

Thomas de Vagan, dit Philalèthe ou Martin Birrhius."

Birrhius, however, was only the editor. These ascriptions

are probably made on the authority of G. W.

Wedelius, who in his preface, dated 2nd Sept., 1698,

to an edition of the Introitus Apertus, published at

Jena in 1699, says of the author:—"Ex Anglia

tamen vulgo habetur oriundus ... et Thomas De

Vagan appellatus." The English Three Tracts

(1694) are stated on the title-page to have been[lv]

written in Latin by Eirenaeus Philalethes; but there

is a note in the British Museum Catalogue to the

effect that the Latin original has the name Eugenius

Philalethes. Unfortunately this Latin Tres Tractatus,

published in 1668 by Martin Birrhius at Amsterdam,

is not in the Library, and I cannot verify the statement.

Finally, I may note that the Ripley Revived

(1678) has an engraved title-page by Robert

Vaughan, who also did the title-page to Olor Iscanus,

and that Starkey's Marrow of Alchemy contains, at

the end of the preface to Part ii., some lines by

William Sampson, which mention

"Harry Mastix Moor

Who judged of Nature when he did not know her";

clearly an allusion to More's controversy with

Thomas Vaughan.

It will be seen that there is some primâ facie

evidence for identifying Eirenaeus Philalethes with

Thomas Vaughan, whereas he was probably not

George Starkey (Eirenaeus Philoponos Philalethes),

and cannot be shown to have been anyone else. But

I am not satisfied. We do not know that Thomas

Vaughan was ever in America, and there is the strong

evidence of Anthony à Wood, who distinguishes

between Eirenaeus and Eugenius, and who appears

to have had information from Henry Vaughan himself.

Mr. A. E. Waite argues against the identification

on the ground that Eirenaeus Philalethes was a[lvi]

"physical alchemist," whereas Thomas Vaughan's

alchemy was spiritual and mystical. But we have

Vaughan's authority for saying that he had pursued

the physical alchemy also.[41] And he was clearly doing

so when he wrote Sloane MS. 1741. A more

pertinent objection is perhaps that Eirenaeus Philalethes

appears to have been in possession of the

grand secret when he wrote the Introitus Apertus in

1645, whereas Thomas Vaughan was still seeking it

in 1658. To pursue the matter further would require

a wide knowledge of the alchemical writings of the

seventeenth century, which unfortunately I do not

possess.[42]

My gratitude is due for help received in compiling

the biographical and other notes in these volumes to

Dr. Grosart, Mr. C. H. Firth, Mr. W. C. Hazlitt,

Mr. A. E. Waite, and the Rev. Llewellyn Thomas;

notably to Miss G. E. F. Morgan of Brecon, whose

knowledge of local genealogy and antiquities has

been invaluable.

July, 1896.E. K. Chambers.

[lvii]

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HENRY VAUGHAN'S WORKS.

(1)

POEMS, | WITH | The tenth SATYRE of | IUVENAL |

ENGLISHED. | By Henry Vaughan, Gent. |—Tam nil,

nulla tibi vendo | Illiade—| LONDON, | Printed for G.

Badger, and are to be sold at his | shop under Saint Dunstan's

Church in | Fleet-street. 1646. [8vo.]

The translation from Juvenal has a separate title-page.

IVVENAL'S | TENTH | SATYRE | TRANSLATED. |

Nèc verbum verbo curabit reddere fidus | Interpres—|

LONDON, | Printed for G. B., and are to be sold at his

Shop | under Saint Dunstan's Church. 1646.

(2)

[Emblem] | Silex Scintillans: | or | SACRED POEMS |

and | Priuate Eiaculations | By | Henry Vaughan Silurist |

LONDON | Printed by T. W. for H. Blunden | at ye Castle

in Cornehill. 1650. [8vo.]

(3)

OLOR ISCANUS. | A COLLECTION | OF SOME SELECT |

POEMS, | AND | TRANSLATIONS, | Formerly

written by | Mr. Henry Vaughan Silurist. | Published by a

Friend. | Virg. Georg. | Flumina amo, Sylvasq. Inglorius—|

LONDON | Printed by T. W. for Humphrey Moseley, | and[lviii]

are to be sold at his shop, at the | Signe of the Princes Arms

in St. Pauls | Church-yard, 1651. [8vo.]

The Preface is dated "Newton by Usk this 17 of Decemb. 1647."

The prose translations in this volume have separate title-pages:

(a) OF THE | BENEFIT | Wee may get by our |

ENEMIES. | A DISCOURSE | Written originally in the |

Greek by Plutarchus Chaeronensis, | translated in to Latin by

I. Reynolds Dr. | of Divinitie and lecturer of the Greeke

Tongue | In Corpus Christi College In Oxford. | Englished By

H: V: Silurist. |—Dolus, an virtus quis in hoste requirat. |—fas

est, et ab hoste doceri. | LONDON. | Printed for

Humphry Moseley [etc.].

(b) OF THE | DISEASES | OF THE | MIND | And

the BODY. | A DISCOURSE | Written originally in the |

Greek by Plutarchus Chaeronensis, | put in to latine by I.

Reynolds D.D. | Englished by H: V: Silurist. | Omnia

perversae poterunt Corrumpere mentes. | LONDON. |

Printed for Humphry Moseley [etc.].

(c) OF THE DISEASES | OF THE | MIND, | AND

THE | BODY, | and which of them is | most pernicious. | The

Question stated, and decided | by Maximus Tirius, a Platonick

Philosopher, written originally in | the Greek, put into

Latine by | John Reynolds D.D. | Englished by Henry

Vaughan Silurist. | LONDON, | Printed for Humphry

Moseley [etc.].

(d) THE | PRAISE | AND | HAPPINESSE | OF THE

| COUNTRIE-LIFE; | Written Originally in | Spanish by

Don Antonio de Guevara, | Bishop of Carthagena, and |

Counsellour of Estate to | Charls the Fifth Emperour | of

Germany. |Put into English by H. Vaughan Silurist. |

Virgil. Georg. | O fortunatos nimiùm, bona si sua nôrint, |

Agricolas!—| LONDON, | Printed for Humphry

Moseley [etc.].

[lix]

(4)

THE | MOUNT of OLIVES: | OR, | SOLITARY

DEVOTIONS. | By | HENRY VAUGHAN Silurist. |

With | An excellent Discourse of the | blessed State of MAN

in GLORY, | written by the most Reverend and | holy Father

ANSELM Arch-| Bishop of Canterbury, and now | done into

English. | Luke 21, v. 39, 37. | [quoted in full]. | LONDON,

Printed for WILLIAM LEAKE at the | Crown in Fleet-Street

between the two | Temple-Gates. 1652 [12mo].

The preface is dated "Newton by Usk this first of October 1651."

The translation from Anselm has a separate title-page:

MAN | IN | GLORY: | OR, | A Discourse of the blessed

| state of the Saints in the | New JERUSALEM. | Written

in Latin by the most | Reverend and holy Father |

ANSELMUS | Archbishop of Canterbury, and now | done

into English. | Printed Anno Dom. 1652.

(5)

Flores Solitudinis. | Certaine Rare and Elegant |

PIECES; | Viz. | Two Excellent Discourses | Of 1. Temperance,

and Patience; | 2. Life and Death. | BY | I. E.

NIEREMBERGIUS. | THE WORLD | CONTEMNED;

| BY | EUCHERIUS, Bp. of LYONS. | And the Life of

| PAULINUS, | Bp. of NOLA. | Collected in his Sicknesse

and Retirement, | BY | HENRY VAUGHAN, Silurist. |

Tantus Amor Florum, & generandi gloria Mellis. | London,

Printed for Humphry Moseley at the | Princes Armes in St.

Pauls Church-yard. 1654. [12mo.]

The Preface is dated "Newton by Usk, in South-Wales,

April 17, 1652." The pieces have separate title-pages:

(a) Two Excellent | DISCOURSES | Of 1. Temperance

and Patience. | 2. Life and Death. | Written in Latin by |

Johan: Euseb: Nierembergius. | Englished by | HENRY

VAUGHAN, Silurist. | ... Mors vitam temperet, &

[lx]

vita Mortem. | LONDON: | Printed for Humphrey Moseley, etc.

The Preface is dated "Newton by Uske neare Sketh-Rock. 1653."

(b) THE WORLD | CONTEMNED, | IN A | Parenetical

Epistle written by | the Reverend Father | EUCHERIUS,

| Bishop of Lyons, to his Kinsman | VALERIANUS. |

[Texts] | London, Printed for Humphrey Moseley [etc.].

(c) Primitive Holiness, | Set forth in the | LIFE | of

blessed | PAULINUS, | The most Reverend, and | Learned

BISHOP of | NOLA: | Collected out of his own Works, |

and other Primitive Authors by | Henry Vaughan, Silurist. |

2 Kings cap. 2. ver. 12 | My Father, my Father, the Chariot

of | Israel, and the Horsmen thereof. | LONDON, | Printed

for Humphry Moseley [etc.].

(6)

Silex Scintillans: | SACRED | POEMS | And private |

EJACULATIONS. | The second Edition, In two Books; |

By Henry Vaughan, Silurist. | Job chap. 35 ver. 10, 11.

| [quoted in full] | London, Printed for Henry Crips, and

Lodo- | wick Lloyd, next to the Castle in Cornhil, | and in

Popes-head Alley. 1655. [8vo.]

A reissue, with additions and a fresh title-page, of (2).

The Preface is dated "Newton by Usk, near Sketh-rock Septem. 30, 1654."

(7)

HERMETICAL | PHYSICK: | OR, | The right

way to pre-| serve, and to restore | HEALTH | BY | That

famous and faith-| full Chymist, | HENRY NOLLIUS. |

Englished by | HENRY UAUGHAN, Gent. | LONDON. |

Printed for Humphrey Moseley, and | are to be sold at his shop,

at the | Princes Armes, in St

Pauls Church-Yard, 1655. [12mo.]

(8)

Thalia Rediviva: | THE | Pass-Times and Diversions

[lxi]

| OF A | COUNTREY-MUSE, | In Choice | POEMS | On

several Occasions. | WITH | Some Learned Remains of the

Eminent | Eugenius Philalethes. | Never made Publick till

now. |—Nec erubuit sylvas habitare Thalia. Virgil. | Licensed,

Roger L'Estrange. | London, Printed for Robert Pawlet at the

Bible in | Chancery-lane, near Fleetstreet, 1678 [8vo.]

The Remains of Eugenius Philalethes [Thomas Vaughan]

have a separate title-page.

Eugenii Philalethis, | VIRI | INSIGNISSIMI | ET |

Poetarum | Sui Saeculi, meritò Principis: | VERTUMNUS |

ET | CYNTHIA, &c. | Q. Horat. |—Qui praegravat artes

Infra se positas, | extinctus am[a]bitur.—| LONDINI, |

Impensis Roberti Pawlett, M.DC.LXXVIII. [12mo.]

(9)

Olor Iscanus. A collection of some Select Poems, Together

with these Translations following, etc. All Englished by

H. Vaughan, Silurist. London: Printed and are to be sold by

Peter Parker ... 1679. [8vo.]

A reissue, according to Dr. Grosart (ii. 59) and W. C. Hazlitt

(Supplement to Third Series Of Collections, p. 106), of the 1651

Olor Iscanus, with a fresh title-page. I have not seen a copy.

(10)

[Miss L. I. Guiney writes in her essay on Henry

Vaughan, the Silurist (Atlantic Monthly, May, 1894): "Mr.

Carew Hazlitt has been fortunate enough to discover the

advertisement of an eighteenth-century Vaughan reprint."

As to this Mr. Hazlitt writes to me: "I cannot tell where

Miss Guiney heard about the Vaughan—not certainly from me.

But there is an edition of his 'Spiritual Songs,' 8vo, 1706, of

which, however, I don't at present know the whereabouts."]

(11)

Silex Scintillans: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations

of Henry Vaughan, with Memoir by the Rev. H. F.

Lyte. London: William Pickering, 1847. [12mo.]

An edition of (6) and part of (8).[lxii]

(12)

The Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations of Henry

Vaughan, with a Memoir by the Rev. H. F. Lyte. Boston

[U. S. A.]: Little, Brown and Company, 1856. [8vo.]

A reprint of (11).

(13)

Silex Scintillans, etc.: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations,

by Henry Vaughan. London: Bell and Daldy. 1858.

A reprint, with a revised text, of (11).

(14)

The Fuller Worthies' Library. The Works in Verse and

Prose complete of Henry Vaughan, Silurist, for the first time

collected and edited: with Memorial-Introduction: Essay on

Life and Writings: and Notes: by the Rev. Alexander B.

Grosart, St. George's, Blackburn, Lancashire. In four

Volumes.... Printed for Private Circulation. 1871.

A reprint of the original editions, with biographical and

critical matter. Only 50 4to, 106 8vo, and 156 12mo copies

printed. In Vol. II. are included the Poems of Thomas

Vaughan, with a separate title-page.

The English and Latin Verse-Remains of Thomas Vaughan

('Eugenius Philalethes'), twin-brother of the Silurist. For

the first time collected and edited: with Memorial-Introduction

and Notes: by the Rev. Alexander B. Grosart [etc.].

(15)

Silex Scintillans, etc. Sacred Poems and Pious Ejaculations.

By Henry Vaughan, "Silurist." With a Memoir

by the Rev. H. F. Lyte. Job xxxv. 10, 11 [in full]. London:

George Bell and Sons, York Street, Covent Garden. 1883. [8vo.]

A reprint, with a text further revised, of (11) and (13), forming

a volume of the Aldine Poets. Since reprinted in 1891.[lxiii]

(16)

The Jewel Poets. Henry Vaughan. Edinburgh. Macniven

and Wallace. 1884.

A selection, with a short preface by W. R. Nicoll.

(17)

Silex Scintillans. Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations,

by Henry Vaughan (Silurist). Being a facsimile of the

First Edition, published in 1650, with an Introduction by the

Rev. William Clare, B.A. (Adelaide). London: Elliot Stock,

62, Paternoster Row. 1885. [12mo.]

A facsimile reprint of (2).

(18)

Secular Poems by Henry Vaughan, Silurist. Including

a few pieces by his twin-brother Thomas ("Eugenius Philalethes").

Selected and arranged, with Notes and Bibliography,

by J. R. Tutin, Editor of "Poems of Richard Crashaw," etc.

Hull: J. R. Tutin. 1893.

A selection from Vol. II. of (14).

(19)

The Poems of Henry Vaughan, Silurist. With an

Introduction by H. C. Beeching, Rector of Yattendon. [Publishers'

Device.] London: Lawrence and Bullen, 16, Henrietta

Street, W.C. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 153-157

Fifth Avenue. 1896. [Two vols. 8vo.]

The present edition. A hundred copies are printed on large paper.

[1]

POEMS,

WITH THE

TENTH SATIRE OF JUVENAL

ENGLISHED.

1646.

[2]

[3]

TO ALL INGENIOUS LOVERS OF POESY.

Gentlemen,

To you alone, whose more refined spirits

out-wing these dull times, and soar above the drudgery

of dirty intelligence, have I made sacred these

fancies: I know the years, and what coarse entertainment

they afford poetry. If any shall question

that courage that durst send me abroad so late, and

revel it thus in the dregs of an age, they have my silence: only,

Languescente seculo, liceat ægrotari.

My more calm ambition, amidst the common noise,

hath thus exposed me to the world: you have here

a flame, bright only in its own innocence, that

kindles nothing but a generous thought: which

though it may warm the blood, the fire at highest

is but Platonic; and the commotion, within these

limits, excludes danger. For the satire, it was of

purpose borrowed to feather some slower hours; and

what you see here is but the interest: it is one of

his whose Roman pen had as much true passion for

the infirmities of that state, as we should have pity[4]

to the distractions of our own: honest—I am sure—it

is, and offensive cannot be, except it meet with such

spirits that will quarrel with antiquity, or purposely

arraign themselves. These indeed may think that

they have slept out so many centuries in this satire

and are now awakened; which, had it been still

Latin, perhaps their nap had been everlasting. But

enough of these,—it is for you only that I have adventured

thus far, and invaded the press with verse; to

whose more noble indulgence I shall now leave it,

and so am gone.—

H. V.

[5]

TO MY INGENUOUS FRIEND, R. W.

When we are dead, and now, no more

Our harmless mirth, our wit, and score

Distracts the town; when all is spent

That the base niggard world hath lent

Thy purse, or mine; when the loath'd noise

Of drawers, 'prentices and boys

Hath left us, and the clam'rous bar

Items no pints i' th' Moon or Star;

When no calm whisp'rers wait the doors,

To fright us with forgotten scores;

And such aged long bills carry,

As might start an antiquary;

When the sad tumults of the maze,

Arrests, suits, and the dreadful face

Of sergeants are not seen, and we

No lawyers' ruffs, or gowns must fee:

When all these mulcts are paid, and I

From thee, dear wit, must part, and die;

We'll beg the world would be so kind,

To give's one grave as we'd one mind;

There, as the wiser few suspect,

That spirits after death affect,

Our souls shall meet, and thence will they,

Freed from the tyranny of clay,

[6]

With equal wings, and ancient love

Into the Elysian fields remove,

Where in those blessèd walks they'll find

More of thy genius, and my mind.

First, in the shade of his own bays,

Great Ben they'll see, whose sacred lays

The learnèd ghosts admire, and throng

To catch the subject of his song.

Then Randolph in those holy meads,

His Lovers and Amyntas reads,

Whilst his Nightingale, close by,

Sings his and her own elegy.

From thence dismiss'd, by subtle roads,

Through airy paths and sad abodes,

They'll come into the drowsy fields

Of Lethe, which such virtue yields,

That, if what poets sing be true,

The streams all sorrow can subdue.

Here, on a silent, shady green,

The souls of lovers oft are seen,

Who, in their life's unhappy space,

Were murder'd by some perjur'd face.

All these th' enchanted streams frequent,

To drown their cares, and discontent,

That th' inconstant, cruel sex

Might not in death their spirits vex.

And here our souls, big with delight

Of their new state, will cease their flight:

And now the last thoughts will appear,

[7]

They'll have of us, or any here;

But on those flow'ry banks will stay,

And drink all sense and cares away.

So they that did of these discuss,

Shall find their fables true in us.

[8]

LES AMOURS

Tyrant, farewell! this heart, the prize

And triumph of thy scornful eyes,

I sacrifice to heaven, and give

To quit my sins, that durst believe

A woman's easy faith, and place

True joys in a changing face.

Yet ere I go: by all those tears

And sighs I spent 'twixt hopes and fears;

By thy own glories, and that hour

Which first enslav'd me to thy power;

I beg, fair one, by this last breath,

This tribute from thee after death.

If, when I'm gone, you chance to see

That cold bed where I lodgèd be,

Let not your hate in death appear,

But bless my ashes with a tear:

This influx from that quick'ning eye,

By secret pow'r, which none can spy,

The cold dust shall inform, and make

Those flames, though dead, new life partake

Whose warmth, help'd by your tears, shall bring

O'er all the tomb a sudden spring

Of crimson flowers, whose drooping heads

Shall curtain o'er their mournful beds:

[9]

And on each leaf, by Heaven's command,

These emblems to the life shall stand

Two hearts, the first a shaft withstood;

The second, shot and wash'd in blood;

And on this heart a dew shall stay,

Which no heat can court away;

But fix'd for ever, witness bears

That hearty sorrow feeds on tears.

Thus Heaven can make it known, and true

That you kill'd me, 'cause I lov'd you.

[10]

TO AMORET.

The Sigh.

Nimble sigh, on thy warm wings,

Take this message and depart;

Tell Amoret, that smiles and sings,

At what thy airy voyage brings,

That thou cam'st lately from my heart.

Tell my lovely foe that I

Have no more such spies to send,

But one or two that I intend,

Some few minutes ere I die,

To her white bosom to commend.

Then whisper by that holy spring,

Where for her sake I would have died,

Whilst those water-nymphs did bring

Flowers to cure what she had tried;

And of my faith and love did sing.

That if my Amoret, if she

In after-times would have it read,

How her beauty murder'd me,

With all my heart I will agree,

If she'll but love me, being dead.

[11]

TO HIS FRIEND BEING IN LOVE.

Ask, lover, ere thou diest; let one poor breath

Steal from thy lips, to tell her of thy death;

Doating idolater! can silence bring

Thy saint propitious? or will Cupid fling

One arrow for thy paleness? leave to try

This silent courtship of a sickly eye.

Witty to tyranny, she too well knows

This but the incense of thy private vows,

That breaks forth at thine eyes, and doth betray

The sacrifice thy wounded heart would pay;

Ask her, fool, ask her; if words cannot move,

The language of thy tears may make her love.

Flow nimbly from me then; and when you fall

On her breast's warmer snow, O may you all,

By some strange fate fix'd there, distinctly lie,

The much lov'd volume of my tragedy.

Where, if you win her not, may this be read,

The cold that freez'd you so, did strike me dead.

[12]

SONG.

Amyntas go, thou art undone,

Thy faithful heart is cross'd by fate;

That love is better not begun,

Where love is come to love too late.[43]

Had she professèd[44] hidden fires,

Or show'd one[45] knot that tied her heart,

I could have quench'd my first desires,

And we had only met to part.

But, tyrant, thus to murder men,

And shed a lover's harmless blood,

And burn him in those flames again,

Which he at first might have withstood.

Yet, who that saw fair Chloris weep

Such sacred dew, with such pure[46] grace;

Durst think them feignèd tears, or seek

For treason in an angel's face.

This is her art, though this be true,

Men's joys are kill'd with[47] griefs and fears,

Yet she, like flowers oppress'd with dew,

Doth thrive and flourish in her tears.

[13]

This, cruel, thou hast done, and thus

That face hath many servants slain,

Though th' end be not to ruin us,

But to seek glory by our pain.[48]

[14]

TO AMORET.

Walking in a Starry Evening.