The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hunting the Skipper, by George Manville Fenn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Hunting the Skipper

The Cruise of the "Seafowl" Sloop

Author: George Manville Fenn

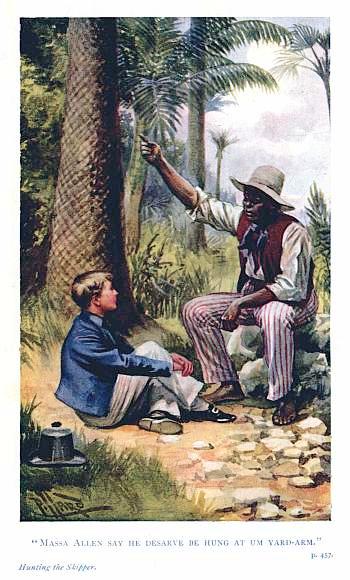

Illustrator: Harold Piffard

Release Date: January 27, 2009 [EBook #27907]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HUNTING THE SKIPPER ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

George Manville Fenn

"Hunting the Skipper"

Chapter One.

H.M.S. “Seafowl.”

“Dicky, dear boy, it’s my impression that we shall see no blackbird’s cage to-day.”

“And it’s my impression, Frank Murray, that if you call me Dicky again I shall punch your head.”

“Poor fellow! Liver, decidedly,” said the first speaker, in a mock sympathetic tone. “Look here, old chap, if I were you, I’d go and ask Jones to give me a blue pill, to be followed eight hours later by one of his delicious liqueurs, all syrup of senna.”

“Ugh!” came in a grunt of disgust, followed by a shudder. “Look here, Frank, if you can’t speak sense, have the goodness to hold your tongue.”

The speakers were two manly looking lads in the uniform of midshipmen of the Royal Navy, each furnished with a telescope, through which he had been trying to pierce the hot thick haze which pretty well shut them in, while as they leaned over the side of Her Majesty’s ship Seafowl, her sails seemed to be as sleepy as the generally smart-looking crew, the light wind which filled them one minute gliding off the next, and leaving them to flap idly as they apparently dozed off into a heavy sleep.

“There, don’t be rusty, old fellow,” said the first speaker.

“Then don’t call me by that absurd name—Dicky—as if I were a bird!”

“Ha, ha! Why not?” said Frank merrily. “You wouldn’t have minded if I had said ‘old cock.’”

“Humph! Perhaps not,” said the young man sourly.

“There, I don’t wonder at your being upset; this heat somehow seems to soak into a fellow and melt all the go out of one. I’m as soft as one of those medusae—jellyfish—what do you call them?—that float by opening and shutting themselves, all of a wet gasp, as one might say.”

“It’s horrible,” said the other, speaking now more sociably.

“Horrible it is, sir, as our fellows say. Well, live and learn, and I’ve learned one thing, and that is if I retire from the service as Captain—no, I’ll be modest—Commander Murray, R.N., I shall not come and settle on the West Coast of Africa.”

“Settle on the West Coast of Africa, with its fevers and horrors? I should think not!” said the other. “Phew! How hot it is! Bah!” he half snorted angrily.

“What’s the matter now?”

“That brass rail. I placed my hand upon it—regularly burned me.”

“Mem for you, old chap—don’t do it again. But, I say, what is the good of our hanging about here? We shall do no good, and it’s completely spoiling the skipper’s temper.”

“Nonsense! Can’t be done.”

“Oh, can’t it, Ricardo!”

“There you go again.”

“Pardon, mon ami! Forgot myself. Plain Richard—there. But that’s wrong. One can’t call you plain Richard, because you’re such a good-looking chap.”

“Bah!” in a deep angry growl.

“What’s that wrong too? Oh, what an unlucky beggar I am! But I say, didn’t you see the skipper?”

“I saw him, of course. But what about him? I saw nothing particular.”

“Old Anderson went up to him as politely as a first lieutenant could—”

“I say, Frank, look here,” cried the other; “can’t you say downright what you have to say, without prosing about like the jolly old preface to an uninteresting book?”

“No, dear boy,” replied the young fellow addressed; “I can’t really. It’s the weather.”

“Hang the weather!” cried the other petulantly.

“Not to be done, dear boy. To hang calls for a rope and the yard-arm, and there’s nothing tangible about the weather. You should say—that is, if you wish to be ungentlemanly and use language unbecoming to an officer in His Majesty’s service—Blow the weather!”

“Oh, bosh, bosh, bosh! You will not be satisfied till I’ve kicked you, Frank.”

“Oh, don’t—pray don’t, my dear fellow, because you will force me to kick you again, and it would make me so hot. But I say, wasn’t I going to tell you something about old Anderson and the skipper?”

“No—yes!—There, I don’t know. Well, what was it?”

“Nothing,” said Frank Murray, yawning. “Oh, dear me, how sleepy I am!”

“Well, of all the aggravating—”

“That’s right: go on. Say it,” said Murray. “I don’t know what you were going to call me, dear boy, but I’m sure it would be correct. That’s just what I am. Pray go on. I’m too hot to hit back.”

“You’re not too hot to talk back, Franky.”

“Eh? Hullo! Why, I ought to fly at you now for calling me by that ridiculous name Franky.”

“Bah! Here, do talk sense. What were you going to tell me about old Anderson and the skipper?”

“I don’t know, dear boy. You’ve bullied it all out of me, or else the weather has taken it out. Oh, I know now: old Anderson went up to him and said something—what it was I don’t know—unless it was about changing our course—and he snarled, turned his back and went below to cool himself, I think. I say, though, it is hot, Dick.”

“Well, do you think I hadn’t found that out?”

“No, it is all plain to see. You are all in a state of trickle, old chap. I say, though, isn’t it a sort of midsummer madness to expect to catch one of these brutal craft on a day like this?”

There was an angry grunt.

“Quite right, old fellow. Bother the slavers! They’re all shut up snugly in the horrible muddy creeks waiting for night, I believe. Then they’ll steal out and we shall go on sailing away north or south as it pleases the skipper. Here, Dicky—I mean, Dick—what will you give me for my share of the prize money?”

“Bah!” ejaculated the youth addressed. “Can’t you be quiet, Frank? Buss, buss, buss! It’s just for the sake of talking. Can’t you realise the fact?”

“No, dear boy; it’s too hot to realise anything?”

“Well, then, let me tell you a home truth.”

“Ah, do! Anything about home and the truth would be delicious here. Wish I could have an ice!”

“There you go! I say, can’t you get tired of talking?”

“No, dear boy. I suppose it is my nature to. What is a fellow to do? You won’t.”

“No, I’m too hot. I wish every slaver that sails these muddy seas was hung at the yard-arm of his own nasty rakish schooner.”

“Hee-ah, hee-ah, hee-ah! as we say in Parliament.”

“Parliament! Parler, to talk!” grunted the other. “That’s where you ought to be, Frank, and then you’d be in your element.”

“Oh, I say! I was only politely agreeing with you. That was a splendid wish. The beasts! The wretches! But somehow they don’t get their deserts. Here have we been two months on this station, and I haven’t had so much as a squint of a slaver. I don’t believe there are any. All myths or fancies—bits of imagination.”

“Oh, there are plenty of them, lad, but they know every in and out of these mangrove-infested shores, and I’ll be bound to say they are watching us day by day, and as soon as we are lost in one of these foggy hazes it’s up with their lug sails, and they glide away like—like—like—here, what do they glide away like? I’m not as clever as you. I’m at a loss for words. Give me one—something poetic, Frank.”

“Steam out of a copper.”

“Bah!”

“What, won’t that do?”

“Do? No! There—like a dream.”

“Brayvo! Werry pretty, as Sam Weller said. Oh, here’s Tommy May—Here, Tom, what do you think of the weather?” said the lad, addressing a bluff-looking seaman.

“Weather, sir?” said the man, screwing up his face till it was one maze of wrinkles. “Beg pardon, sir, but did you mean that as one of your jokes, sir, or was it a conundydrum?”

“Oh, don’t ask questions, Tom, but just tell us plainly what you think of the weather.”

“Nothing, sir; it’s too hot to think,” replied the man.

“Quite right, May,” said the other midshipman. “Don’t bother the poor fellow, Murray. Here, May, what do you fellows before the mast think about the slavers?”

“Slippery as the mud of the river banks, sir.”

“Good,” said Murray. “Well spoken, Tom. But do you think there are any about here?”

“Oh yes, sir,” said the man; “no doubt about it. They on’y want catching.”

“No, no,” cried Murray. “That’s just what they don’t want.”

“Right you are, sir; but you know what I mean.”

“I suppose so,” said Murray; “but do you chaps, when you are chewing it all over along with your quids, believe that we shall come upon any of them?”

“Oh yes, sir; but do you see, they sail in those long, low, swift schooners that can come and go where they like, while we in the Seafowl seem to be thinking about it.”

“Poor sluggish sloop of war!” said Roberts.

“Nay, nay, sir,” said the man, “begging your pardon, she’s as smart a vessel as ever I sailed in, with as fine a captain and officers, ’specially the young gentlemen.”

“Now, none of your flattering gammon, Tom.”

“Begging your pardon, gentlemen,” said the man sturdily, “that it arn’t. I says what I says, and I sticks to it, and if we only get these here blackbird catchers on the hop we’ll let ’em see what the Seafowl can do.”

“If!” said Roberts bitterly.

“Yes, sir, if. That’s it, sir, and one of these days we shall drop upon them and make them stare. We shall do it, gentlemen, you see if we shan’t.”

“That’s what we want to see, Tom,” said Murray.

“Course you do, gentlemen, and all we lads forrard are itching for it, that we are—just about half mad.”

“For prize money?” said Roberts sourly.

“Prize money, sir?” replied the man. “Why, of course, sir. It’s a Bri’sh sailor’s nature to like a bit of prize money at the end of a v’y’ge; but, begging your pardon, sir, don’t you make no mistake. There arn’t a messmate o’ mine as wouldn’t give up his prize money for the sake of overhauling a slaver and reskying a load o’ them poor black beggars. It’s horrid; that’s what it just is.”

“Quite right, May,” said Roberts.

“Thankye, sir,” said the man; “and as we was a-saying on’y last night—talking together we was as we lay out on the deck because it was too stuffycatin’ to sleep.”

“So it was, May,” said Roberts.

“Yes, sir; reg’lar stifler. Well, what we all agreed was that what we should like to do was to set the tables upside down.”

“What for?” said Murray, giving his comrade a peculiar glance from the corner of his eye.

“Why, to give the poor niggers a chance to have a pop at some of the slavers’ crews, sir, to drive ’em with the whip and make ’em work in the plantations, sir, like dumb beasts. I should like to see it, sir.”

“Well said, Tom!” cried Murray.

“Thankye, sir. But it’s slow work ketching, sir, for you see it’s their swift craft.”

“Which makes them so crafty, eh, Tom?” cried Murray.

“Yes, sir. I don’t quite understand what you mean, sir, but I suppose it’s all right, and—”

“Sail on the lee bow!” sang out a voice from the main-top.

Chapter Two.

Bother the Fog.

A minute before those words were shouted from the main-top, the low-toned conversation carried on by the two young officers, with an occasional creak or rattle from a swinging sail was all that broke the silence of the drowsy vessel; now from everywhere came the buzz of voices and the hurrying trample of feet.

“It’s just as if some one had thrust a stick into a wasp’s nest,” whispered Frank Murray to his companion, as they saw that the captain and officers had hurried up on deck to follow the two lads’ example of bringing their spy-glasses to bear upon a faintly seen sail upon the horizon, where it was plainly marked for a few minutes—long enough to be made out as a low schooner with raking masts, carrying a heavy spread of canvas, which gradually grew fainter and fainter before it died away in the silvery haze. The time was short, but quite long enough for orders to be sharply given, men to spring up aloft, and the sloop’s course to be altered, when shuddering sails began to fill out, making the Seafowl careen over lightly, and a slight foam formed on either side of the cut-water.

“That’s woke us up, Richard, my son,” said Murray.

“Yes, and it means a chance at last.”

“If.”

“Only this; we just managed to sight that schooner before she died away again in the haze.”

“Well, that gave us long enough to notice her and send the Seafowl gliding along upon her course. Isn’t that enough?”

“Not quite, old fellow.”

“Bah! What a fellow you are, Frank! You’re never satisfied,” cried Roberts. “What have you got in your head now?”

“Only this; we had long enough before the haze closed in to sight the schooner well.”

“Of course. We agreed to that.”

“Well, suppose it gave them time enough to see us?”

“Doubtful. A vessel like that is not likely to have a man aloft on the lookout.”

“There I don’t agree with you, Dick. It strikes me that they must keep a very sharp lookout on board these schooners, or else we must have overhauled one of them before now.”

“Humph!” said Roberts shortly. “Well, we shall see. According to my ideas it won’t be very long before we shall be sending a shot across that schooner’s bows, and then a boat aboard. Hurrah! Our bad luck is broken at last.”

“Doesn’t look like it,” said Murray, who had dropped all light flippancy and banter, to speak now as the eager young officer deeply interested in everything connected with his profession.

“Oh, get out!” cried Roberts. “What do you mean by your croaking? Look at the way in which our duck has spread her wings and is following in the schooner’s wake. It’s glorious, and the very air seems in our favour, for it isn’t half so hot.”

“I mean,” said Murray quietly, “that the mist is growing more dense.”

“So much in our favour.”

“Yes,” said Murray, “if the schooner’s skipper did not sight us first.”

“Oh, bother! I don’t believe he would.”

“What’s that?” said a gruff voice.

“Only this, sir,” said Roberts to the first lieutenant, who had drawn near unobserved; “only Murray croaking, sir.”

“What about, Murray?” asked the elderly officer.

“I was only saying, sir, that we shall not overhaul the schooner if her people sighted us first.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of, my lads,” said the old officer. “This haze may be very good for us, but it may be very good for them and give their skipper a chance to double and run for one or other of the wretched muddy creeks or rivers which they know by heart. There must be one somewhere near, or she would not have ventured out by daylight, and when we get within striking distance we may find her gone.”

The lieutenant passed the two lads and went forward, where he was heard to give an order or two which resulted in a man being stationed in the fore chains ready to take soundings; and soon after he was in eager conversation with the captain.

“Feeling our way,” said Murray, almost in a whisper, as he and his companion stood together where the man in the chains heaved the lead, singing out the soundings cheerily till he was checked by an order which resulted in his marking off the number of fathoms in a speaking voice, and later on in quite a subdued tone, for the haze had thickened into a sea fog, and the distance sailed ought to have brought the Seafowl pretty near to the schooner, whose commander might possibly take alarm at the announcement of a strange vessel’s approach.

“I’m afraid they must have heard us before now,” said Roberts softly. “Ah, hark at that!”

For as the man in the chains gave out the soundings it was evident that the depth was rapidly shoaling, when, in obedience to an order to the helmsman a turn or two was given to the wheel, the sloop of war was thrown up into the wind, the sails began to shiver, and the Seafowl lay rocking gently upon the swell.

“Bother the fog!” said Murray fretfully. “It’s growing worse.”

“No, sir,” said the seaman who was close at hand. “Seems to me that it’s on the move, and afore long we shall be in the clear, sir, and see where we are.”

The man’s words proved to be correct sooner than could have been expected, for before many minutes had passed, and just when the mist which shut them in was at its worst, the solid-looking bank of cloud began to open, and passed away aft; the sun shot out torrid rays, and those on board the Seafowl were seeing the need there had been for care, for they were gazing across the clear sea at the wide-spreading mangrove-covered shore, which, monotonous and of a dingy green, stretched away to north and south as far as eye could reach.

“Where’s the schooner?” exclaimed Murray excitedly, for the Seafowl seemed to be alone upon the dazzling waters.

“In the fog behind us,” said Roberts, in a disappointed tone. “We’ve overdone it. I expected we should; the skipper was in such a jolly hurry.”

Frank Murray took his companion’s words as being the correct explanation of the state of affairs; but they soon proved to be wrong, for the soft breeze that had sprung up from the shore rapidly swept the fog away seaward, and though all on board the sloop watched eagerly for the moment when the smart schooner should emerge, it at last became plain that she had eluded them—how, no one on board could say.

“It’s plain enough that she can’t have gone seaward,” said Roberts thoughtfully. “She must have sailed right away to the east.”

“Yes,” said Murray thoughtfully.

“Of course! Right over the tops of the mangroves,” said Roberts mockingly. “They hang very close, and there’s a heavy dew lying upon them, I’ll be bound.”

“Oh, yes, of course,” said Murray. “She couldn’t have passed in through some opening, I suppose?”

“Where is the opening, then?” cried Roberts shortly.

“I don’t know,” replied his companion coolly; “but there must be one, and the captain of the schooner must be quite at home here and know his way.”

“I wish my young officers would learn to know their way about this horrible shore instead of spending their time in talking,” cried an angry voice, and the two midshipmen started apart as they awoke to the fact that the captain had approached them unheard while they were intently sweeping the shore.

“Higher, my lad—higher up,” cried the captain. “The cross-trees, and be smart about it.—Yes, Mr Murray, you’re right; there’s a narrow river somewhere about, or perhaps it’s a wide one. Take your glass, sir—the opening is waiting to be found. What do you think of it, Mr Anderson?”

“I don’t think, sir. I feel sure the schooner has come out of some river along here, caught sight of us, and taken advantage of the mist to make her way back, and for aught we know she is lying snugly enough, waiting till we are gone.”

“Thank you, Mr Anderson,” said the captain, with studied politeness, “but unfortunately I knew all this before you spoke. What I want to know is where our friend is lying so snugly. What do you say to that?”

“Only this, sir—that we must run in as far as we can and sail along close inshore till we come to the opening of the river.”

“And while we sail south we shall be leaving the mouth behind, Mr Anderson, eh?”

“If it proves to be so, sir,” replied the first lieutenant gravely, “we must sail north again and again too, until we find the entrance.”

“Humph! Yes, sir; but hang it all, are my officers asleep, that we are sailing up and down here month after month without doing anything? Here, Mr Murray, what are you thinking about, sir?”

The lad started, for his chief had suddenly fired his question at him like a shot.

“Well, sir, why don’t you answer my question?”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” replied Murray now. “I was thinking.”

“Yes, sir, you were thinking,” cried the captain passionately. “I know you were thinking, and saying to yourself that you had a most unreasonable captain.”

Murray was silent, and the first lieutenant and the other midshipman, after exchanging a glance, fixed their eyes upon the monotonous shore.

“Do you hear me, sir?” thundered the captain, as if he were speaking to the lookout at the mast-head instead of the lad close to him. “That was what you were thinking, was it not? Come: the truth.”

He bent forward to gaze straight into the boy’s eyes as if determined to get an answer.

“Yes, sir,” said the lad desperately, “something of that sort;” and then to himself, “Oh, murder! I’m in for it now!”

“Yes, I knew you were, Mr Murray,” cried the captain. “Thank you. I like my junior officers to speak out truthfully and well. Makes us place confidence in them, Mr Anderson, eh?”

“Yes, sir,” growled the chief officer, “but it isn’t always pleasant.”

“Quite right, Mr Anderson, and it sounds like confounded impudence, too. But we’re wasting time, and it is valuable. I’m going to have that schooner found. The sea’s as smooth as an inland lake, so man and lower down the cutters. You take the first cutter, Mr Anderson, Munday the second. Row or sail to north and south as the wind serves, and I’ll stand out a bit to see that you don’t start the game so that it escapes. You young gentlemen had better go with the boats.”

Murray glanced at the old officer, and to the question in his eyes there came a nod by way of answer.

“You always have the luck, Franky,” grumbled Roberts, as soon as they were alone.

“Nonsense! You have as good a chance as I have of finding the schooner.”

“What, with prosy old Munday! Why, he’ll most likely go to sleep.”

“So much the better for you. You can take command of the boat and discover the schooner’s hiding-place.”

“Of course. Board her, capture the Spanish—”

“Or Yankee,” said Murray.

“Captain!” snapped out Roberts. “Oh yes, I know. Bother! I do get so tired of all this.”

Tired or no, the young man seemed well on the alert as he stepped into the second cutter, and soon after each of the boats had run up their little sail, for a light breeze was blowing, and, leaving the sloop behind, all the men full of excitement as every eye was fixed upon the long stretches of mangrove north and south in search of the hidden opening which might mean the way into some creek, or perhaps the half-choked-up entrance into one of the muddy rivers of the vast African shore.

Chapter Three.

The Cute Visitor.

The first cutter had the wind in her favour and glided northward mile after mile along a shore thickly covered with the peculiar growth of the mangrove, those dense bird-affecting, reptile-haunted coverts, whose sole use seems to be that of keeping the muddy soil of the West Afric shores from being washed away.

The heat was terrible, and the men were congratulating themselves on the fact that the wind held out and saved them from the painful task of rowing hard in the blistering sunshine.

Murray’s duty was to handle the tiller lines as he sat in the stern sheets beside the first lieutenant, and after being out close upon three hours he began to feel that he could keep awake no longer—for his companion sat silent and stern, his gaze bent upon the dark green shore, searching vainly for the hidden opening—and in a half torpid state the midshipman was about to turn to his silent companion and ask to be relieved of the lines, when he uttered a gasp of thankfulness, and, forgetting discipline, gripped the officer by the knee.

“What the something, Mr Murray, do you mean by that?” cried the lieutenant angrily.

“Look!” was the reply, accompanied by a hand stretched out with pointing index finger.

“Stand by, my lads, ready to pull for all you know,” cried the lieutenant. “The wind may drop at any moment. You, Tom May, take a pull at that sheet; Mr Murray, tighten that port line. That’s better; we must cut that lugger off. Did you see where she came out?”

“Not quite, sir,” said Murray, as he altered the boat’s course a trifle, “but it must have been close hereabouts. What are you going to do, sir?”

“Do, my lad? Why, take her and make the master or whatever he is, act as guide.”

“I see, sir. Then you think he must have come out of the river where the schooner has taken refuge?”

“That’s what I think,” said the lieutenant grimly; “and if I am right I fancy the captain will not be quite so hard upon us as he has been of late.”

“It will be a glorious triumph for us—I mean for you, sir,” said Murray hurriedly.

“Quite right, Mr Murray,” said his companion, smiling. “I can well afford to share the honours with you, for I shall have owed it to your sharp eyes. But there, don’t let’s talk. We must act and strain every nerve, for I’m doubtful about that lugger; she sails well and may escape us after all.”

Murray set his teeth as he steered so as to get every foot of speed possible out of the cutter, while, sheet in hand, Tom May sat eagerly watching the steersman, ready to obey the slightest sign as the boat’s crew sat fast with the oars in the rowlocks ready to dip together and pull for all they were worth, should the wind fail.

“That’s good, my lads,” said the lieutenant—“most seamanlike. It’s a pleasure to command such a crew.”

There was a low hissing sound as of men drawing their breath hard, and the old officer went on.

“We’re not losing ground, Mr Murray,” he said.

“No, sir; gaining upon her, I think.”

“So do I—think, Mr Murray,” said the lieutenant shortly, “but I’m not sure. Ah, she’s changing her course,” he added excitedly, “and we shall lose her. Oh, these luggers, these luggers! How they can skim over the waves! Here, marines,” he said sharply, as he turned to a couple of the rifle-armed men who sat in the stern sheets, “be ready to send a shot through the lugger’s foresail if I give the order; the skipper may understand what I mean.” And the speaker, sat frowning heavily at the lightly-built lugger they were following. “I don’t see what more I can do, Mr Murray.”

“No, sir,” said the midshipman hoarsely. “Oh, give the order, sir—pray do! We mustn’t lose that boat.”

“Fire!” said the lieutenant sharply; and one marine’s rifle cracked, while as the smoke rose lightly in the air Murray uttered a low cry of exultation.

“Right through the foresail, sir, and the skipper knows what we mean.”

“Yes, capital! Good shot, marine.”

The man’s face shone with pleasure as he thrust in a fresh cartridge before ramming it down, and the crew looked as if they were panting to give out a loud cheer at the success of the lieutenant’s manoeuvre, for the little lugger, which was just beginning to creep away from them after a change in her course, now obeyed a touch of her helm and bore round into the wind till the big lug sails shivered and she gradually settled down to rock softly upon the long heaving swell that swept in landward.

As the cutter neared, Murray noted that the strange boat was manned by a little crew of keen-looking blacks, not the heavy, protuberant-lipped, flat-nosed, West Coast “niggers,” but men of the fierce-looking tribes who seem to have come from the east in the course of ages and have preserved somewhat of the Arabic type and its keen, sharp intelligence of expression.

But the midshipman had not much time for observation of the little crew, his attention being taken up directly by the dramatic-looking entrance upon the scene of one who was apparently the skipper or owner of the lugger, and who had evidently been having a nap in the shade cast by the aft lugsail, and been awakened by the shot to give the order which had thrown the lugger up into the wind.

He surprised both the lieutenant and Murray as he popped into sight to seize the side of his swift little vessel and lean over towards the approaching cutter, as, snatching off his wide white Panama hat, he passed one duck-covered white arm across his yellowish-looking hairless face and shouted fiercely and in a peculiar twang—

“Here, I say, you, whoever you are, do you know you have sent a bullet through my fores’l?”

“Yes, sir. Heave to,” said the lieutenant angrily.

“Wal, I have hev to, hevn’t I, sirr? But just you look here; I don’t know what you thought you was shooting at, but I suppose you are a Britisher, and I’m sure your laws don’t give you leave to shoot peaceful traders to fill your bags.”

“That will do,” said the lieutenant sternly. “What boat’s that?”

“I guess it’s mine, for I had it built to my order, and paid for it. Perhaps you wouldn’t mind telling me what your boat is and what you was shooting at?”

“This is the first cutter of Her Majesty’s sloop of war Seafowl,” said the lieutenant sternly, “and—”

But the American cut what was about to be said in two by crying in his sharp nasal twang—

“Then just you look here, stranger; yew’ve got hold of a boat as is just about as wrong as it can be for these waters. I’ve studied it and ciphered it out, and I tell yew that if yew don’t look out yew’ll be took by one of the waves we have off this here coast, and down yew’ll go. I don’t want to offend yew, mister, for I can see that yew’re an officer, but I tell yew that yew ought to be ashamed of yewrself to bring your men along here in such a hen cock-shell as that boat of yourn.”

“Why, it’s as seaworthy as yours, sir,” said the lieutenant good-humouredly.

“Not it, mister; and besides, I never go far from home in mine.”

“From home!” said the lieutenant keenly. “Where do you call home?”

“Yonder,” said the American, with a jerk of his head. “You ain’t got no home here, and it’s a mercy that you haven’t been swamped before now. Where have you come from?—the Cape?”

“No,” said the lieutenant; “but look here, sir, what are you, and what are you doing out here?”

“Sailing now,” said the American.

“But when you are ashore?”

“Rubber,” said the man.

“What, trading in indiarubber?”

“Shall be bimeby. Growing it now—plantation.”

“Oh,” said the lieutenant, looking at the speaker dubiously. “Where is your plantation?”

“Up the creek yonder,” replied the American, with another nod of his head towards the coast.

“Oh,” said the lieutenant quietly; “you have a plantation, have you, for the production of rubber, and you work that with slaves?”

“Ha, ha, ha, ha!” laughed the American, showing a set of very yellow teeth. “That’s what you’re after, then? I see through you now, cyaptain. You’re after slave-traders.”

“Perhaps so; and you confess yourself to be one,” said the lieutenant.

“Me?” said the American, laughing boisterously again. “Hev another try, cyaptain. Yew’re out this time. Ketch me trying to work a plantation with West Coast niggers! See those boys o’ mine?”

“Yes; I see your men,” replied the lieutenant.

“Them’s the stuff I work with. Pay ’em well and they work well. No work, no pay. Why, one of those fellows’d do more work for me in a day than one of the blacks they come here to buy up could do in a week.”

“Then slave-traders come here to buy, eh?”

“Yes, they do,” replied the man, “but ’tain’t none of my business. They don’t interfere with me, and I don’t interfere with them. Plenty of room here for both. Yew’re after them, then?”

“Yes,” said the lieutenant frankly.

“Phew!” whistled the man, giving his knees a slap. “Why, you’ll be after the schooner that came into this river this morning?”

“Possibly,” said the lieutenant, while Murray felt his blood thrill in his veins with the excitement of the position. “What schooner was it?”

“Smart sailing craft, with long rakish masts?”

“Yes, yes,” said the lieutenant; “I know all about that. A slaver, eh?”

The American half shut his eyes as he peered out of their corners at the British officer, and a queer smile puckered up his countenance.

“Slaving ain’t lawful, is it, mister?” he said.

“You answer my question,” said the lieutenant testily.

“Means confiscation, don’t it?”

“And that is not an answer,” cried the lieutenant angrily.

“Yew making a prize of that theer smart schooner from her top-masts down to her keel, eh?”

“Will you reply to what I say?” cried the lieutenant. “Is she a slaver?”

“Lookye here, mister,” said the American, grinning. “S’pose I say yes, you’ll jest confiscate that there schooner when her skipper and her crew slips over the side into the boats and pulls ashore.”

“Perhaps I may,” said the lieutenant shortly.

“Exackly so, mister. Then you sails away with her for a prize, eh?”

“Possibly,” said the lieutenant coldly.

“And what about me?”

“Well, what about you?”

“I can’t pull back to my rubber plantations and sail them away, can I?”

“I do not understand you, sir,” said the lieutenant sharply.

“No, and you don’t care to understand me, mister. ‘No,’ says you, ‘it’s no business of mine about his pesky injyrubby fields.’”

“Why should it be, sir?” said the lieutenant shortly.

“Exackly so, mister; but it means a deal to me. How shall I look after you’re gone when the slaver’s skipper—”

“Ah!” cried Murray excitedly. “Then she is a slaver!”

The American’s eyes twinkled as he turned upon the young man.

“Yew’re a sharp ’un, yew are,” he said, showing his yellow teeth. “Did I say she was a slaver?”

“Yes, you did,” cried Murray.

“Slipped out then because your boss began saying slaver, I suppose. That was your word and I give it to yew back again. I want to live peaceable like on my plantation and make my dollahs out of that there elastic and far-stretching projuice of the injyrubbery trees. That’s my business, misters, and I’m not going to take away any man’s crackter.”

“You have given me the clue I want, sir,” said the lieutenant, “and it is of no use for you to shirk any longer from telling me the plain truth about what is going on up this river or creek.”

“Oh, isn’t it, mister officer? Perhaps I know my business better than you can tell me. I dessay yew’re a very smart officer, but I could give you fits over growing rubber, and I’m not going to interfere with my neighbours who may carry on a elastic trade of their own in black rubber or they may not. ’Tain’t my business. As I said afore, or was going to say afore when this here young shaver as hain’t begun to shave yet put his oar in and stopped me, how should I look when yew’d gone and that half-breed black and yaller Portygee schooner skipper comes back with three or four boat-loads of his cut-throats and says to me in his bad language that ain’t nayther English, ’Murrican, nor nothing else but hashed swearing, ‘Look here,’ he says, ‘won’t injyrubber burn like fire, eh?’ ‘Yes,’ I says, civil and smooth, ‘it is rayther rum-combustible.’ ‘So I thought,’ he says. ‘Well, you’ve been letting that tongue of yours go running along and showing those cusses of Britishers where I anchor my boat and load up with plantation stuff for the West Injies; so jes’ look here,’ he sez, ‘I’ve lost thousands o’ dollars threw yew, and so I’m just going to make yew pay for it by burning up your plantations and putting a stop to your trade, same as yew’ve put a stop to mine. I shan’t hurt yew, because I’m a kind-hearted gentle sorter man, but I can’t answer for my crew. I can’t pay them, because yew’ve took my ship and my marchandise, so I shall tell them they must take it outer yew. And they will, stranger. I don’t say as they’ll use their knives over the job, and I don’t say as they won’t, but what I do say is that I shouldn’t like to be yew.’ There, Mister Officer, that’s about what’s the matter with me, and now yew understand why I don’t keer about meddling with my neighbours’ business.”

“Yes, I understand perfectly,” said the lieutenant, “but I want you to see that it is your duty to help to put a stop to this horrible traffic in human beings. Have you no pity for the poor blacks who are made prisoners, and are dragged away from their homes to be taken across the sea and sold like so many cattle?”

“Me? Pity! Mister, I’m full of it. I’m sorry as sorrow for the poor niggers, and whenever I know that yon schooner is loading up with black stuff I shuts my eyes and looks t’other way.”

“Indeed!” cried Murray. “And pray how do you manage to do that?”

“Why, ain’t I telling on you, youngster? I shuts my eyes so as I can’t see.”

“Then how can you look another way?”

The American displayed every tooth in his head and winked at the lieutenant.

“Yew’ve got a sharp ’un here, mister. I should keep him covered up, or shut him up somehow, ’fore he cuts anybody or himself. But yew understand what I mean, mister, and I dessay you can see now why I feel it my business to be very sorry for the black niggers, but more sorry for myself and my people. I don’t want to be knifed by a set o’ hangdog rubbish from all parts o’ the world. I’m a peaceable man, mister, but you’re a cap’en of a man-o’-war, I suppose?”

“Chief officer,” said the lieutenant.

“And what’s him?” said the American, jerking his thumb over his shoulder in the direction of the midshipman. “Young chief officer?”

“Junior officer.”

“Oh, his he? Well, I tell you what: yew both go and act like men-o’-war. Sail up close to that schooner, fire your big guns, and send her to the bottom of the river.”

“And what about the poor slaves?” said Murray excitedly.

“Eh, the black stuff?” said the American, scratching his chin with his forefinger. “Oh, I forgot all about them. Rather bad for them, eh, mister?”

“Of course,” said the lieutenant. “No, sir, that will not do. I want to take the schooner, and make her captain and crew prisoners.”

“Yew’ll have to look slippery then, mister. But what about the niggers?”

“I shall take them with the vessel to Lagos or some other port where a prize court is held, and the judge will no doubt order the best to be done with them.”

“Which means put an end to the lot, eh?” said the American.

“Bah! Nonsense!” cried Murray indignantly.

“Is it, young mister? Well, I didn’t know. It ain’t my business. Yew go on and do what’s right. It’s your business. I don’t keer so long as I’m not mixed up with it. I’ve on’y got one life, and I want to take keer on it. Now we understand one another?”

“Not quite,” said the lieutenant.

“Why, what is there as yew can’t take in?”

“Nothing,” said the lieutenant. “I quite see your position, and that you do not wish to run any risks with the slaver captain and his men.”

“Not a cent’s worth if I can help it.”

“And quite right, sir,” said the lieutenant; “but I take it that you know this slaver skipper by sight?”

“Oh, yes, I know him, mister—quite as much as I want to.”

“And you know where he trades to?”

“West Injies.”

“No, no; I mean his place here.”

“Oh, you mean his barracks and sheds where the chief stores up all the black stuff for him to come and fetch away?”

“Yes, that’s it,” cried Murray excitedly.

“Have the goodness to let me conclude this important business, Mr Murray,” said the lieutenant coldly.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Murray, turning scarlet; “I was so excited.”

“That’s one for you, mister young chief officer,” said the American, grinning at the midshipman, and then turning to the lieutenant. “These young uns want sitting upon a bit sometimes, eh, mister?”

“Look here, sir,” said the lieutenant, ignoring the remark; “just listen to me. I want you to guide me and my men to the foul nest of this slave-trader and the town of the black chief.”

The American shook his head.

“You need not shrink, for you will be under the protection of the English Government.”

“That’s a long way off, mister.”

“But very far-reaching, sir,” continued the lieutenant, “and I promise you full protection for all that you do. Why, surely, man, you will be able to cultivate your plantation far more peacefully and with greater satisfaction with the river cleared of this abominable traffic.”

“Well, if you put it in that way, mister, I should,” said the man, “and that’s a fine range of rich land where the black chief has his people and their huts. I could do wonders with that bit if I could hold it safely. The rubber I’d plant there would be enough to—”

“Rub out all the black marks that the slave-trade has made.”

“Very good, Mr Murray,” said the lieutenant, smiling pleasantly, “but this is no time to try and be smart.”

“Eh?” said the American. “Was that what he was aiming at? I didn’t understand; but I tell yew that there is about a mile of rich syle there which if I had I could make it projuice a fortune.”

“Look here, sir,” said the lieutenant, “I have no doubt about the possibility of your being helped by the British Government to take possession of such a tract after we have done with it.”

“Why, you don’t mean, Mister Chief Officer, that you will let your British Lion put his paw upon it and stick to it till you’ve done with it, as you say?”

“No, no, no,” said the lieutenant, smiling. “I mean that the British Lion will put its paw upon the horrible settlement in this way and will root out the traffic, and we shall only be too glad to encourage the rise of a peaceful honest culture such as you are carrying on.”

“You mean then that you’ll root out the slaves and burn the chief’s town?”

“Most certainly,” said the lieutenant. “And help me to get hold of that there land?”

“I believe I may promise that.”

“And take care that the Portygee slaver cock has his comb cut so as he dursen’t meddle with me?”

“I feel sure that all this will follow if you help us to capture the slaver, and point out where the abominable traffic is carried on.”

“Shake on it,” said the American, thrusting out a thin yellow hand with unpleasantly long nails.

“Shake hands upon the compact?” said the lieutenant good-humouredly. “Very good;” and he gave the yellow hand a good manly grip.

“Then I’m on!” cried the man effusively. “But look here, yew’re in this too;” and he stretched out his hand to Murray. “Yew’re a witness to all your chief said.”

“Oh, all right,” said Murray, and he let the long, thin, unpleasantly cold and dank fingers close round his hand, but not without a feeling of disgust which was expressed by the making of a grimace as soon as the American turned to the lieutenant again.

“That’s settled, then,” said the latter, “so go on at once and lead while we follow.”

“What!” said the American, with a look of wonder.

“I say, go on and guide us to the slaver’s nest.”

“What, just alone like this here?”

“Yes, of course. You see we are well-armed and ready to board and take the schooner at once. Fire will destroy the chief’s town.”

“Well, you do ’maze me,” said the American, showing his teeth.

“What do you mean?” said the lieutenant sternly. “Are you going to draw back?”

“Not me, mister. That’s a bargain,” said the man, grinning. “I mean that you ’maze me, you Englishers do, by your cheek. I don’t doubt you a bit. You mean it, and yew’ll dew it. Why, I dessay if yew yewrself wasn’t here this here young shaver of an officer would have a try at it hisself. You would, wouldn’t you, youngster?”

“Why, of course I would,” said Murray proudly; and then, feeling afraid that his assertion might be looked upon as braggadocio, he hastened to add, “I—I—er—meant to say that I would try, and our brave fellows would take the prisoners.”

“Nay, nay, yew would,” said the American. “There ain’t nothing to be ashamed on in being brave, is there, mister?”

“Of course not,” said the lieutenant.

“Of course not,” said the American; “but look here, sirree, it’s no good to lose brave men by trying to do things that’s a bit too strong and starky for you.”

“What, do you mean that the schooner’s crew would be too strong for us?”

“Nay, not me, mister. Yew’d chaw them up safe. But there’s the black king; he’s got close upon a hundred fighting men, chaps with spears. He’d fight too, for though they ain’t got much brains, these niggers, he’d know you’d be going to do away with his bread and cheese, as you may say. No, sirree, I ain’t a fighting man; rubber’s my line, but I want to get hold of that bit of syle—make sewer of it, as you may say; and if I’d got that job to do I should get another boatful of men if you could. Don’t know of a British ship handy, do you?”

“Of course. My captain is off the coast not far away. You did not suppose that we came alone?”

“Oh, I didn’t know, mister. Could you bring your captain then?”

“Yes.”

“And another boat?”

“Of course.”

“Then if I was you I should tell him to sail up the river.”

“What, is there water enough—deep water?” asked the lieutenant.

“Whatcher talking about?” said the man contemptuously. “Why, didn’t you see me sail out?”

The lieutenant shook his head.

“Think o’ that!” said the American. “Way in’s bit narrer, but as soon as you get threw the trees you’re in a big mighty river you can sail up for months if yew like. I have heerd that there’s some falls somewhere, but I’ve never seem ’em. Water enough? My snakes! There’s water enough to make a flood, if you want one, as soon as you get by the winding bits.”

“The river winds?” said the lieutenant.

“Winds? I should think she does! Why, look yonder, mister,” continued the man, pointing. “It’s all trees like that for miles. You’ve got to get through them.”

“Deep water?” asked the lieutenant.

“Orful! On’y it’s ’bout as muddy as rivers can be made.”

“And you assure me that you could pilot us in and right up to the slaver’s stronghold?”

“Pilot yew? Yew don’t want no piloting; all yew’ve got to do is to sail up in and out through the big wilderness of trees. Yew wouldn’t want no piloting, but if you undertake to see that I have that chief’s land, and clear him and his black crews away, I’ll lay yew off his front door where you can blow his palm-tree palace all to smithers without losing a man.”

“And what about the slaver?” asked Murray.

“What about her? She’ll be lying anchored there, of course.”

“With any colleagues?” asked the lieutenant.

“Whatche’r mean—t’others?”

“Yes.”

“Not now, mister. There’s as many as four or five sometimes, but I only see her go up the river this time. Yew should have come later on if you wanted more.”

“The slaver is up the river now, then?” said the lieutenant, looking at the man searchingly.

“Yes, of course,” was the reply, as the American involuntarily gave a look round, and then, as if taking himself to task for an act of folly, he added laughingly. “If she wasn’t up there she’d be out here, and you can see for yourselves that she ain’t.”

“You could show us the way in?” said Murray.

“Why, didn’t I say I could?” replied the man sharply.

“Yes; but I should like to have a glimpse of her first,” said Murray.

“What for, youngster? To let her know that you’re coming? You take my advice, mister, and come upon her sudden like.”

The lieutenant gazed intently upon the man.

“Yes; I should like to reconnoitre a bit first. With your assistance we ought to be able to run our boats close up under the shelter of the trees and see what she is like.”

“See what she’s like, mister? Why, like any other schooner. You take my advice; you’ll slip off and fetch your ship, and I’ll wait here till you come back.”

Murray looked at the man searchingly, for somehow a sense of doubt began to trouble him as to the man’s trustworthiness, and the lad began to turn over the position in his mind. For though the man’s story seemed to be reasonable enough, an element of suspicion began to creep in and he began to long to ask the lieutenant as to what he thought about the matter.

But he did not speak, for the keen-looking American’s eyes were upon him, and when they shifted it was only for them to be turned upon the lieutenant.

“Wal,” he said at last, “whatcher thinking about, mister?”

“About your running me up to where you could point out the schooner.”

“But I don’t want to,” said the man frankly.

“Why?” asked the lieutenant sharply.

“’Cause I don’t want to lose the chance of getting that there mile of plantation.”

“There ought to be no risk, sir, if we were careful.”

“I dunno so much about that there, mister. Them slaver chaps always sleep with one eye open, and there’s no knowing what might happen.”

“What might happen! What could happen?”

“Nothing; but the skipper might hyste sail and run his craft right up towards the falls. As I said, I never see them, but there must be falls to keep this river so full.”

“But we could follow him.”

“Part of the way p’raps, mister, but he could go in his light craft much further than you could in a man-o’-war.”

“True,” said the lieutenant; “you are right.”

“Somewhere about,” said the man, showing his teeth. “There, you slip off and fetch your ship, and I’ll cruise up and down off the mouth of the river here so as to make sure that the schooner don’t slip off. She’s just as like as not to hyste sail now that the fog’s all gone. She’d have been off before if it hadn’t come on as thick as soup. Say, ’bout how far off is your ship?”

“Half-a-dozen miles away,” said the lieutenant.

“That ain’t far. Why not be off at once?”

“Why not come with us?” asked Murray.

“Ain’t I telled yer, youngster? Think I want to come back and find the schooner gone?”

The lieutenant gazed from the American to the midshipman and back again, with his doubts here and there, veering like a weather vane, for the thought would keep attacking him—suppose all this about the slave schooner was Yankee bunkum, and as soon as he had got rid of them, the lugger would sail away and be seen no more?

“You won’t trust him, will you?” said Murray, taking advantage of a puff of wind which separated the two boats for a few minutes.

“I can’t,” said the lieutenant, in a whisper. “I was nearly placing confidence in him, but your doubt has steered me in the other direction. Hah!” he added quickly. “That will prove him.” And just then the lugger glided alongside again, and the opportunity for further communing between the two officers was gone.

“That’s what yew have to be on the lookout for, mister, when yew get sailing out here. Sharp cat’s-paws o’ wind hot as fire sometimes. Well, ain’t you going to fetch your ship?”

“And what about you?” said the lieutenant.

“Me?” said the man wonderingly, and looking as innocent as a child.

“Yes; where am I to pick you up again?”

“Oh! I’ll show you. I’ll be hanging just inside one of the mouths of the river, and then lead yew in when yew get back with yewr ship.”

Murray softly pressed his foot against his officer’s without seeming to move, and felt the pressure returned, as if to say—All right; I’m not going to trust him—and the lieutenant then said aloud—

“But why shouldn’t you sail with us as far as our sloop?”

“Ah, why shouldn’t I, after all?” said the man. “You might show me your skipper, and we could talk to him about what we’re going to do. All right; sail away if you like to chance it.”

The lieutenant nodded, and a few minutes later the two boats were gliding about half a mile abreast of the dense mangrove-covered shore in the direction of the Seafowl, and only about fifty yards apart.

“You’ll be keeping a sharp lookout for treachery in any shape, sir?” said Murray, in a low tone.

“The fellow’s willingness to fall in with my proposal has disarmed me, Mr Murray,” said the lieutenant quietly, “but all the same I felt bound to be cautious. I have given the marines orders to be ready to fire at the slightest sign of an attempt to get away.”

“You have, sir? Bravo!” said Murray, in the same low tone, and without seeming to be talking to his chief if they were observed. “But I did not hear you speak to the jollies.”

“No, Mr Murray; I did not mean you to, and I did not shout. But this caution is, after all, unnecessary, for there comes the sloop to look after us. Look; she is rounding that tree-covered headland.”

“Better and better, sir!” cried Murray excitedly. “I was beginning to fidget about the lugger.”

“What about her, Mr Murray?”

“Beginning to feel afraid of her slipping away as soon as we were out of sight.”

“You think, then, that the lugger’s people might be on the watch?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Quite possible,” said the lieutenant. “Well, we have her safe now.”

“Yes, sir; but won’t you heave to and wait?”

“To be sure, yes, Mr Murray; a good idea; and let the sloop sail up to us?”

“Won’t it make the captain storm a bit, sir, and ask sharply why we didn’t make haste and join?”

“Most likely, Mr Murray,” said the lieutenant quietly; “but if he does we have two answers.”

“The lugger, sir.”

“Yes, Mr Murray, and the discovery of the schooner.”

“Waiting to be boarded, sir,” said the midshipman.

“Exactly, Mr Murray. Any one make out the second cutter?”

“Ay, ay, sir!” cried Tom May. “There she is, sir—miles astarn of the Seafowl, sir.”

“I wish we could signal to her to lay off and on where she is.”

“What for, sir?”

“There may be one of the narrow entrances to the great river thereabouts, and the wider the space we can cover, the greater chance we shall have of preventing the slaver from stealing away.”

Chapter Four.

The Yankee’s Food.

“Grand, Mr Anderson,” said the captain, after a time. But his first words had come pouring out like a storm of blame, which gave the first lieutenant no opportunity to report what he had done. “Yes: could not be better sir. There, we are going to capture a slaver at last!”

“Yes, sir, if we have luck; and to stamp out one of the strongholds of the accursed trade.”

Then the captain became silent, and stood thoughtfully looking over the side at the indiarubber planter’s lugger.

“Humph!” he ejaculated, at last. “Rather a serious risk to run, to trust to this stranger and make him our guide.”

“So it struck me, sir, as I told you,” said the lieutenant.

“Let me see, Mr Anderson, did you tell me that?”

“Yes, sir, if you will recall it.”

“Humph! Yes, I suppose you did. But I was thinking. Suppose he plays us false.”

“Why should he, sir?”

“To be sure, why should he, Mr Anderson? All the same, we must be careful.”

Meanwhile, Murray was being cross-examined by his brother midshipman, who looked out of temper, and expressed himself sourly upon coming aboard.

“You have all the luck,” he said. “You drop into all the spirited adventures, while I am packed off with prosy old Munday.”

“Oh, nonsense! It is all chance. But didn’t you see anything, old chap?”

“Yes—muddy water; dingy mangroves; the tail of a croc as the filthy reptile slid off the tree roots into the water. That was all, while there I was cooking in the heat, and listening to old Munday prose, prose, prose, till I dropped off to sleep, when the disagreeable beggar woke me up, to bully me about neglecting my duty, and told me that I should never get to be a smart officer if I took so little interest in my profession that I could not keep awake when out on duty.”

“Well, it did seem hard, Dick, when he sent you off to sleep. I couldn’t have kept awake, I know.”

“I’m sure you couldn’t. But there: bother! You couldn’t help getting all the luck.”

“No; and you are going to share it now.”

“Not so sure, Frank. As like as not the skipper will send me away in a boat to watch some hole where the slaver might slip out. So this Yankee is going to act as pilot and lead us up the river to where the schooner is hiding?”

“Yes, and to show us the chief’s town, and the place where he collects the poor unfortunate blacks ready for being shipped away to the Spanish plantations.”

“My word, it’s fine!” cried Roberts excitedly. “And hooroar, as Tom May has it. Why, the lads will be half mad with delight.”

“And enough to make them,” said Murray. “But I say, how does it strike you?”

“As being glorious. Franky, old fellow, if it wasn’t for the look of the thing I could chuck up my cap and break out into a hornpipe. Dance it without music.”

“To the delight of the men, and make Anderson or Munday say that it was not like the conduct of an officer and a gentleman.”

“Yes, that’s the worst of it. But though of course we’re men now—”

“Midshipmen,” said Murray drily.

“Don’t sneer, old chap! And don’t interrupt when I’m talking.”

“Say on, O sage,” said the lad.

“I was going to say that of course, though we are men now, one does feel a bit of the boy sometimes, and as if it was pleasant now and then to have a good lark.” As the young fellow spoke he passed his hand thoughtfully over his cheeks and chin. “What are you grinning at?” he continued.

“Not grinning, old fellow; it was only a smile.”

“Now, none of your gammon. You were laughing at me.”

“Oh! Nothing!” said Murray, with the smile deepening at the corners of his mouth.

“There you go again!” cried Roberts. “Who’s to keep friends with you, Frank Murray, when you are always trying to pick a quarrel with a fellow?”

“What, by smiling?”

“No, by laughing at a fellow and then pretending you were not. Now then, what was it?”

“Oh, all right; I only smiled at you about your shaving so carefully this morning.”

“How did you know I shaved this morning?” cried the midshipman, flushing.

“You told me so.”

“That I’ll swear I didn’t.”

“Not with your lips, Dicky—Dick—but with your fingers.”

“Oh! Bother! I never did see such a fellow as you are to spy out things,” cried Roberts petulantly.

“Not spy, old chap. I only try to put that and that together, and I want you to do the same. So you think this is all glorious about yonder planter chap piloting us to the slaver’s place?”

“Of course! Don’t you?”

“Well, I don’t know, Dick,” said Murray, filling his forehead with wrinkles.

“Oh, I never did see such a fellow for pouring a souse of cold water down a fellow’s back,” cried Roberts passionately. “You don’t mean to say that you think he’s a fraud?”

“Can’t help thinking something of the kind, old man.”

“Oh!” ejaculated Roberts. “I say, here, tell us what makes you think so.”

“He’s too easy and ready, Dick,” said Murray, throwing off his ordinary merry ways and speaking seriously and with his face full of thought.

“But what does Anderson say to it?”

“He seemed to be suspicious once, but it all passed off, and then the skipper when he heard everything too talked as if he had his doubts. But now he treats it as if it is all right, and we are to follow this American chap wherever he leads us.”

“Yes, to-morrow morning, isn’t it?”

“No, Dick; to-night.”

“To-night—in the dark?”

“I suppose so.”

“Oh!” said Roberts thoughtfully, and he began to shave himself with his finger once more, but without provoking the faintest smile from his companion. “I say, Franky, I don’t like that.”

“No; neither do I, Dick.”

“It does seem like putting ourselves into his hands,” continued Roberts thoughtfully. “Oh, but I don’t know,” he continued, as if snatching at anything that told for the success of the expedition; “you know what Anderson often tells us.”

“I know what he says sometimes about our being thoughtless boys.”

“Yes, that’s what I mean, old fellow; and it isn’t true, for I think a deal about my duties, and as for you—you’re a beggar to think, just like the monkey who wouldn’t speak for fear he should be set to work.”

“Thanks for the compliment,” said Murray drily.

“Oh, you know what I mean. But I suppose we can’t think so well now as we shall by and by. I mean, older fellows can think better, and I suppose that the skipper and old Anderson really do know better than we do. It will be all right, old fellow. They wouldn’t let themselves be led into any trap; and besides, look at the Yankee—I mean, look at his position; he must be sharp enough.”

“Oh yes, he’s sharp enough,” said Murray. “Hear him talk, and you’d think he was brought up on pap made of boiled-down razor-strops.”

“Well, then, he must know well enough that if he did the slightest thing in the way of playing fast and loose with us, he’d get a bullet through his head.”

“Yes—if he wasn’t too sharp for us.”

“Oh, it will be all right,” cried Roberts. “Don’t be too cautious, Franky. Put your faith in your superior officers; that’s the way to succeed.”

“Then you think I am too cautious here, Dick?”

“Of course I do,” cried Roberts, patting his brother middy on the shoulder. “It will be all right, so don’t be dumpy. I feel as if we are going to have a fine time of it.”

“Think we shall have any fighting?”

“Afraid not; but you do as I do. I mean to get hold of a cutlass and pistols. I’m not going to risk my valuable life with nothing to preserve it but a ridiculous dirk. Don’t you be downhearted and think that the expedition is coming to grief.”

“Not I,” said Murray cheerily. “I suppose it’s all right; but I couldn’t help thinking what I have told you. I wish I didn’t think such things; but it’s a way I have.”

“Yes,” said his companion, “and any one wouldn’t expect it of you, Franky, seeing what a light-hearted chap you are. It’s a fault in your nature, a thing you ought to correct. If you don’t get over it you’ll never make a dashing officer.”

“Be too cautious, eh?” said Murray good-humouredly.

“That’s it, old chap. Oh, I say, though, I wish it was nearly night, and that we were going off at once. But I say, where’s the Yankee?”

“What!” cried Murray, starting. “Isn’t he alongside in his boat?”

“No; didn’t you see? He came aboard half-an-hour ago. Old Bosun Dempsey fetched him out of his lugger; and look yonder, you croaking old cock raven. We always have one jolly as sentry at the gangway, don’t we?”

“Of course.”

“Very well, look now; there are two loaded and primed ready for any pranks the lugger men might play; and there are the two cutters ready for lowering down at a moment’s notice, and it wouldn’t take long for Dempsey to fizzle out his tune on his pipe and send the crews into them.”

“Bah! Pish! Pooh! and the rest of it. What do you mean by that? Look, the lugger is a fast sailer.”

“Well, I dare say she is, but one of our little brass guns can send balls that sail through the air much faster. So drop all those dismal prophecies and damping thoughts about danger. Our officers know their way about and have got their eyes open. The skipper knows about everything, and what he doesn’t know bully Anderson tells him. It’s all right, Franky. Just look at the lads! Why, there’s Tom May smiling as if he’d filled his pockets full of prize money.”

“Yes,” assented Murray, “and the other lads have shaped their phizzes to match. But let’s get closer to the lugger.”

“What for?” said Roberts sharply.

“To have a good look at her Indiarubber-cultivating crew.”

“Not I!” cried Roberts. “If we go there you’ll begin to see something wrong again, and begin to croak.”

“No, no; honour bright! If I do think anything, I won’t say a word.”

“I’d better keep you here out of temptation,” said Roberts dubiously.

“Nonsense! It’s all right, I tell you. There, come along.”

Chapter Five.

Trusting a Guide.

The two lads made for where they could get a good view of the lugger swinging by a rope abreast of the starboard gangway, and as they passed along the quarter-deck, the shrill strident tones of the American’s voice reached them through one of the open cabin skylights, while directly after, Murray, keen and observant of everything, noted that the two marines of whom his companion had spoken were standing apparently simply on duty, but thoroughly upon the alert and ready for anything, their whole bearing suggesting that they had received the strictest of orders, and were prepared for anything that might occur.

Roberts gave his companion a nudge with his elbow and a quick glance of the eye, which produced “Yes, all right; I see,” from Murray. “I’m afraid—I mean I’m glad to see that I was only croaking; but I say, Dick, have a good quiet look at those fellows and see if you don’t find some excuse for what I thought.”

“Bah! Beginning to croak again.”

“That I’m not,” said Murray. “I only say have a look at them, especially at that fellow smoking.”

“Wait a moment. I have focussed my eye upon that beauty getting his quid ready—disgusting!”

“Yes, it does look nasty,” said Murray, with the corners of his lips turning up. “The regular Malay fashion. That fellow never came from these parts.”

“Suppose not. Why can’t the nasty wretch cut a quid off a bit of black twist tobacco like an ordinary British sailor?”

“Instead of taking a leaf out of his pouch,” continued Murray, “smearing it with that mess of white lime paste out of his shell—”

“Putting a bit of broken betel nut inside—” said Roberts.

“Rolling it up together—” continued Murray.

“And popping the whole ball into his pretty mouth,” said Roberts. “Bah! Look at his black teeth and the stained corners of his lips. Talk about a dirty habit! Our jacks are bad enough. Ugh!”

“I say, Dick,” whispered Murray, as the Malay occupant of the boat realised the fact that he was being watched, and rolled his opal eyeballs round with a peculiar leer up at the two young officers.

“Now then,” was the reply, “you promised that you wouldn’t croak.”

“To be sure. I only wanted to say that fellow looks a beauty.”

“Beauty is only skin deep,” said Roberts softly.

“And ugliness goes to the bone,” whispered Murray, smiling. “Yes, he looks a nice fellow to be a cultivator of the indiarubber plant.”

“Eh? Who said he was?” said Roberts sharply.

“His skipper. That’s what they all are. Splendid workers too. Do more than regular niggers.”

“Do more, no doubt,” said Roberts thoughtfully. “But they certainly don’t look like agricultural labourers. Why, they’re a regular crew of all sorts.”

“Irregular crew, you mean,” said Murray. “That one to the left looks like an Arab.”

“Yes, and the one asleep with his mouth open and the flies buzzing about him looks to me like a Krooboy. Well, upon my word, old Croaker, they do look—I say, do you see that blackest one?”

“Yes; and I’ve seen them before, you know.”

“But he opened and shut his mouth just now. You didn’t see that, did you?”

“Yes, I saw it; he has had his teeth filed like a saw.”

“That’s what I meant, and it makes him look like a crocodile when he gapes.”

“Or a shark.”

“Well,” said Roberts, after a pause, “upon my word, Frank, they do look about as ugly a set of cut-throat scoundrels as ever I saw in my life.”

“Right,” said Murray eagerly. “Well, what do you say now?”

“That I should like to point out their peculiarities to the skipper and old Anderson, and tell them what we think. Go and ask them to come and look.”

“I have already done so to Anderson.”

“But you ought to do it to the skipper as well. Look here, go at once and fetch him here to look.”

“While the American is with him? Thank you; I’d rather not.”

“Do you mean that?”

“To be sure I do. What would he say to me?”

“Oh, he’d cut up rough, of course; but you wouldn’t mind that in the cause of duty.”

Murray laughed softly.

“Why, Dick, I can almost hear what he would say about my impudence to attempt to teach him his duty. No, thank you, my dear boy; if he and Anderson think it right to trust the American, why, it must be right. If you feel that the nature of these fellows ought to be pointed out, why, you go and do it.”

Roberts took another look at the lugger’s crew, and then shrugged his shoulders, just as the captain came on deck, followed by the American and the first lieutenant.

The American was talking away volubly, and every word of the conversation came plainly to the ears of the two lads.

“Of course, cyaptain, I’ll stop on board your craft if yew like, but I put it to yew, how am I going to play pilot and lead you in through the mouth if I stop here? I can sail my lugger easy enough, but I should get into a tarnation mess if I tried to con your big ship. Better let me lead in aboard my own craft, and you follow.”

“In the darkness of night?” said the captain.

“There ain’t no darkness to-night, mister. It’ll be full moon, and it’s morning pretty early—just soon enough for you to begin business at daybreak. I shall lead you right up to where the schooner’s lying, and then you’ll be ready to waken the skipper up by giving him a good round up with your big guns.”

“And what about the slaves?”

“Oh, you must fire high, sir, and then yew won’t touch them. High firing’s just what yew want so as to cripple his sails and leave him broken-winged like a shot bird on the water.”

The captain nodded, and the two midshipmen, after a glance at the first lieutenant, to see that he was listening attentively with half-closed eyes, gazed at the American again.

“Lookye here, mister,” he said, “yew must make no mistake over this job. If yew do, it’s going to be pretty bad for me, and instead of me being rid of a bad neighbour or two, and coming in for a long strip of rich rubber-growing land, I shall find myself dropped upon for letting on to him yewr craft; and I tell yew he’s a coon, this slave cyaptain, as won’t forgive anything of that kind. He’s just this sort of fellow. If he finds I’ve done him such an on-neighbourly act, he’ll just give his fellows a nod, and in less time than yew can wink there’ll be no rubber-grower anywhere above ground, for there’ll be a fine rich plantation to sell and no bidders, while this ’ere industrious enterprising party will be somewhere down the river, put aside into some hole in the bank to get nice and mellow by one of the crockydiles, who object to their meat being too fresh.”

“Ugh!” shuddered Roberts.

“Oh, that’s right enough, young squire,” said the man, turning upon him sharply. “I ain’t telling you no travellers’ tales. It’s all true enough. Wal, cyaptain, don’t you see the sense of what I am saying?”

“Yes, sir. But tell me this; do you guarantee that there are no shoals anywhere about the mouth of the river?”

“Shoals, no; sands, no, sir. All deep water without any bottom to speak of. But where you find it all deep mud yew can’t take no harm, sir. The river’s made its way right threw the forest, and the bank’s cut right straight down and up perpendicular like, while if you were to go ashore it would only be to send your jib boom right in among the trees and your cut-water against the soft muddy bank. Why, it’s mostly a hundred feet deep. Yew trust me, and yew’ll find plenty of room; but if yew don’t feel quite comf’table, if I was yew I’d just lie off for a bit while you send in one of your boats and Squire First Lieutenant there, to see what it’s like, and the sooner the better, for the sun’s getting low, and as I dessay yew know better than I can tell yew, it ain’t long after the sun sinks before it’s tidy dark. Now then, what do yew say? I’m ready as soon as yew are.”

“How long will it take us to get up to the chief’s town?”

“’Bout till daylight to-morrow morn’, mister. That’s what I’m telling of yew.”

“Then it’s quite a big river?”

“Mighty big, sir.”

“And the current?”

“None at all hardly, mister. Yew’ll just ketch the night wind as blows off the sea, and that’ll take yew up as far as yew want to go. Then morrow mornin’ if yew’re done all yew want to do yew’ll have the land wind to take yew out to sea again. Though I’m thinking that yew won’t be able to do all yew want in one day, for there’s a lot of black folk to deal with, and I wouldn’t be in too great a hurry. Yew take my advice, cyaptain; do it well while yew’re about it, and yew won’t repent.”

“Never fear, sir,” said the captain sternly. “I shall do my work thoroughly. Now then, back into your lugger and show us the way. Mr Munday, take the second cutter and follow this American gentleman’s lead, and then stay alongside his boat while Mr Anderson comes back to report to me in the first cutter. You both have your instructions. Yes, Mr Roberts—Yes, Mr Murray,” continued the captain, in response to a couple of appealing looks; “you can accompany the two armed boats.”

Chapter Six.

Into the Mist.

Murray thought that the American screwed up his eyes in a peculiar way when he found that the two boats were to go in advance of the sloop, but he had no opportunity for telling Roberts what he believed he had seen, while so busy a time followed and his attention was so much taken up that it was not till long afterwards that he recalled what he had noted.

The American, upon rejoining his lugger, sailed away at once with the two boats in close attendance and the sloop right behind, their pilot keeping along the dingy mangrove-covered shore and about half-a-mile distant, where no opening seemed visible; and so blank was the outlook that the first lieutenant had turned to his young companion to say in an angry whisper—

“I don’t like this at all, Mr Murray.” But the words were no sooner out of his mouth than to the surprise of both there was a sudden pressure upon the lugger’s tiller, the little vessel swung round, and her cut-water pointed at once for the densely wooded shore, so that she glided along in a course diagonal to that which she had been pursuing.

“Why, what game is he playing now?” muttered the lieutenant. “There is no opening here. Yes, there is,” he added, the next minute. “No wonder we passed it by. How curious! Ah, here comes the moon.”

For as the great orb slowly rose and sent her horizontal rays over the sea in a wide path of light, she lit-up what at first sight seemed to be a narrow opening in the mangrove forest, but which rapidly spread out wider and wider, till as the three boats glided gently along, their sails well filled by the soft sea breeze, Murray gazed back, to see that the sloop was now following into what proved to be a wide estuary, shut off from seaward by what appeared now in the moonlight a long narrow strip of mangrove-covered shore.

“River,” said the lieutenant decisively, “and a big one too. Now, Tom May, steady with the lead.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” cried the man, and he began to take soundings, one of the sailors in the second cutter receiving his orders and beginning to follow the example set.

Then there was a hail from the lugger.

“What game do you call this?”

“Soundings,” replied the lieutenant gruffly.

“Twenty fathom for miles up, and you can go close inshore if you like. It’s all alike.”

“P’raps so,” said the officer, “but my orders are to sound.”

“Sound away, then,” said the American sourly; “but do you want to be a week?” And he relapsed into silence, till about a couple of miles of the course of the wide river had been covered, sounding after sounding being taken, which proved the perfect truth of the American’s words.

Then the two cutters closed up and there was a brief order given by the first lieutenant, which resulted in the second cutter beginning to make its way back to where the sloop lay in the mouth of the estuary.

“What yer doing now?” came from the lugger.

“Sending word to the sloop that there’s plenty of water and that she may come on.”

“Course she may, mister,” grumbled the American. “Think I would ha’ telled yew if it hedn’t been all right? Yew Englishers are queer fish!”

“Yes,” said the lieutenant quietly. “We like to feel our way cautiously in strange waters.”

“Then I s’pose we may anchor now till your skipper comes? All right, then, on’y you’re not going to get up alongside of the schooner this side of to-morrow morning, I tell yew.”

“Very well, then, we must take the other side of her the next morning.”

The American issued an order of his own in a sulky tone of voice, lowering his sails; and then there was a splash as a grapnel was dropped over the side.

“Hadn’t yew better anchor?” he shouted good-humouredly now. “If yew don’t yew’ll go drifting backward pretty fast.”

For answer the lieutenant gave the order to lower the grapnel, and following the light splash and the running out of the line came the announcement of the sailor in charge as he checked the falling rope—

“No bottom here.”

“Takes a tidy long line here, mister,” came in the American’s sneering voice. “Guess your sloop’s keel won’t touch no bottom when she comes up.”

The lieutenant made no reply save by hoisting sail again and running to and fro around and about the anchored lugger, so as to pass the time in taking soundings, all of which went to prove that the river flowed sluggishly seaward with so little variation in the depth that the soundings were perfectly unnecessary.

It was tedious work, and a couple of hours passed before, pale and spirit-like at first, the other cutter came into sight in the pale moonlight, followed by the sloop, when the American had the lugger’s grapnel hauled up and ran his boat alongside of the first cutter.

“Look here,” he said angrily, “yewr skipper’s just making a fool of me, and I may as well run ashore to my plantation, for we shan’t do no good to-night.”

The man’s words were repeated when the sloop came up, and a short discussion followed, which resulted in the captain changing his orders.

“The man’s honest enough, Anderson,” he said, “and I must trust him.”

“What do you mean to do, then, sir?” said the first lieutenant, in a low tone.

“Let him pilot us to where the slaver lies.”

“With the lead going all the time, sir?”

“Of course, Mr Anderson,” said the captain shortly. “Do you think me mad?”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” replied the chief officer. “Perhaps it will be best.”

It proved to be best so far as the American’s temper was concerned, for upon hearing the captain’s decision, he took his place at the tiller of his lugger and led the way up the great river, followed by the stately sloop, whose lead as it was lowered from time to time told the same unvarying tale of deep water with a muddy bottom, while as the river’s winding course altered slightly, the width as far as it could be made out by the night glasses gave at least a couple of miles to the shore on either hand.