The Project Gutenberg EBook of City Crimes, by Greenhorn

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

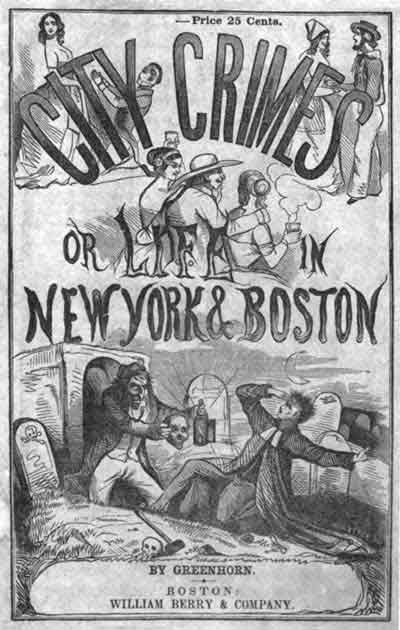

Title: City Crimes

or Life in New York and Boston

Author: Greenhorn

Release Date: January 7, 2009 [EBook #27732]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CITY CRIMES ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Linda Hamilton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

City Crimes;

{First published 1849}

[Pg 3] [Pg 4]

A Young Gentleman of Wealth and Fashion—a noble resolve—the flatterers—the Midnight Encounter—an Adventure—the Courtezan—Temptation triumphant—how the Night was passed.

'What a happy dog I ought to be!' exclaimed Frank Sydney, as he reposed his slippered feet upon the fender, and sipped his third glass of old Madeira, one winter's evening in the year 18—, in the great city of New York.

Frank might well say so; for in addition to being as handsome a fellow as one would be likely to meet in a day's walk, he possessed an ample fortune, left him by a deceased uncle. He was an orphan; and at the age of twenty-one, found himself surrounded by all the advantages of wealth, and at the same time, was perfect master of his own actions. Occupying elegant apartments at a fashionable hotel, he was free from any of those petty cares and vexations which might have annoyed him, and he kept an establishment of his own; while at the same time he was enabled to maintain, in his rooms, a private table for the entertainment of himself and friends, who frequently repaired thither, to partake of his hospitality and champagne suppers. With such advantages of fortune and position, no wonder he exclaimed, as at the beginning of our tale—'What a happy dog I ought to be!'

Pursuing the current of his thought Frank half audibly continued—

'Yes, I have everything to make me truly happy—health, youth, good looks and wealth; and yet it seems to me that I should derive a more substantial satisfaction from my riches were I to apply them to the good of mankind. To benefit one's fellow creatures is the noblest and most exalted of enjoyments—far superior to the gratification of sense. The grateful blessings of the poor widow or orphan, relieved by my bounty, are greater music to my soul, than the insincere plaudits of my professed friends, who gather around my hearth to feast upon my hospitality, and yet who, were I to lose my wealth, and become poor, would soon cut my acquaintance, and sting me by their ingratitude. To-night I shall have a numerous party of these friends to sup with me, and this supper shall be the last one to which I shall ever invite them. Yes! My wealth shall be employed for a nobler object than to pamper these false and hollow-hearted parasites. From this night, I devote my time, my energies and my affluence to the relief of deserving poverty and the welfare of all who need my aid with whom I may come in contact. I will go in person to the squalid abodes of the poor—I will seek them out in the dark alleys and obscure lanes of this mighty metropolis—I will, in the holy mission of charity, venture into the [Pg 5]vilest dens of sin and iniquity, fearing no danger, and shrinking not from the duty which I have assumed.—Thus shall my wealth be a blessing to my fellow creatures, and not merely a means of ministering to my own selfishness.'

Noble resolve! All honor to thy good and generous heart, Frank Sydney! Thou hast the true patent of nature's nobility, which elevates and ennobles thee, more than a thousand vain titles or empty honors! Thou wilt keep thy word, and become the poor man's friend—the liberal and enlightened philanthropist—the advocate of deserving poverty, and foe to the oppressor, who sets his heel upon the neck of his brother man.

The friends who were to sup with him, arrived, and they all sat down to a sumptuous entertainment. Frank did the honors with his accustomed affability and care; and flowing bumpers were drunk to his health, while the most flattering eulogiums upon his merits and excellent qualities passed from lip to lip. Frank had sufficient discernment to perceive that all this praise was nothing but the ebullitions of the veriest sycophants; and he resolved at some time to test the sincerity of their protestations of eternal friendship.

'Allow me, gentlemen,' said Mr. Archibald Slinkey, a red-faced, elderly man, with a nose like the beak of a poll-parrot—'to propose the health of my excellent and highly esteemed friend, Frank Sydney. Gentlemen, I am a plain man, unused to flattery, and may be pardoned for speaking openly before the face of our friend—for I will say it, he is the most noble hearted, enlightened, conscientious, consistent, and superlatively good fellow I ever met in the course of my existence.'

'So he is,' echoed Mr. Narcissus Nobbs, a middle-aged gentleman, with no nose to speak of, but possessing a redundancy of chin and a wonderful capacity of mouth—'so he is, Slinkey; his position—his earning—his talent—his wealth—'

'Oh, d——n his wealth,' ejaculated Mr. Solomon Jenks, a young gentleman who affected a charming frankness and abruptness in his speech, but who was in reality the most specious flatterer of the entire party. Mr. Jenks rejoiced in the following personal advantages: red hair, a blue nose, goggle eyes, and jaws of transparent thinness.

'D——n his wealth!' said Jenks—'who cares for that? Sydney's a good fellow—a capital dog—an excellent, d——d good sort of a whole-souled devil—but his wealth is no merit. If he lost every shilling he has in the world, why curse me if I shouldn't like him all the better for it! I almost wish the rascal would become penniless tomorrow, in order to afford me an opportunity of showing him the disinterestedness of my friendship. I would divide my purse with him, take him by the hand and say—Frank, my boy, I like you for yourself alone, and d——n me if you are not welcome to all I have in the world—That's how I would do it.'

'I thank you gentlemen, for your kind consideration,' said Frank; 'I trust I may never be necessitated to apply to any of my friends, for aid in a disagreeable emergency—but should such ever unfortunately be the case, be assured that I shall not hesitate to avail myself of your generous assistance.'

'Bravo—capital—excellent!' responded the choir of flatterers, in full chorus, and their glasses were again emptied in honor of their host.

It was midnight ere these worthies took their departure. When at length they[Pg 6] were all gone, and Frank found himself alone, he exclaimed—'Thank heaven, I am at last rid of those miserable and servile fellows, who in my presence load me with the most extravagant praise and adulation, while behind my back they doubtless ridicule my supposed credulity. I have too long tolerated them—henceforth, I discard and cast them off.'

He approached the window, and drawing aside the curtain, looked forth into the streets. The moon was shining brightly; and its rays fell with dazzling lustre upon the snow which covered the ground. It was a most lovely night, altho' excessively cold; and Sydney, feeling not the least inclination to retire to rest, said to himself:

'What is to prevent me from beginning my career of usefulness and charity to-night? The hour is late—but misery sleeps not, and 'tis never too late to alleviate the sufferings of distressed humanity. Yes, I will go forth, even at the midnight hour, and perchance I may encounter some poor fellow-creature worthy of my aid, or visit some abode of poverty where I can minister to the comfort of its wretched inmates.'

He threw on an ample cloak, put on a fur cap and gloves, and taking his sword-cane in his hand, left the hotel, and proceeded at a rapid pace thro' the moon-lit and deserted streets. He entered the Park, and crossed over towards Chatham street, wishing to penetrate into the more obscure portions of the city, where Poverty, too often linked with Crime, finds a miserable dwelling-place. Thus far, he had not encountered a single person; but on approaching the rear of the City Hall, he observed the figure of a man issue from the dark obscurity of the building, and advance directly toward him. Sydney did not seek to avoid him, supposing him to be one of the watchmen stationed in that vicinity, but a nearer view satisfied him that the person was no watchman but a man clothed in rags, whose appearance betokened the extreme of human wretchedness. He was of a large and powerful build, but seemed attenuated by want, or disease—or perhaps, both. As he approached Sydney, his gestures were wild and threatening: he held in his hands a large paving-stone, which he raised, as if to hurl it at the other with all his force.

Sydney, naturally conceiving the man's intentions to be hostile, drew the sword from his cane, and prepared to act on the defensive, at the same time exclaiming:

'Who are you, and what do you wish?'

'Money!' answered the other, in a hollow tone, with the stone still upraised, while his eyes glowed savagely upon the young man.

Sydney, who was brave and dauntless, steadily returned his gaze, and said, calmly:

'You adopt a strange method, friend, of levying contributions upon travellers. If you are in distress and need aid, you should apply for it in a becoming manner—not approach a stranger in this threatening and ruffianly style. Stand off—I am armed, you see—I shall not hesitate to use this weapon if—'

The robber burst into a wild, ferocious laugh:

'Fool!' he cried. 'What can your weak arm or puny weapon do, against the strength of a madman? For look you, I am mad with hunger! For three days I have not tasted food—for three cold, wretched nights I have roamed thro' the streets of[Pg 7] this Christian city, homeless, friendless, penniless! Give me money, or with this stone will I dash out your brains.'

'Unfortunate man,' said Sydney, in accents of deep pity—'I feel for you, on my soul I do. Want and wretchedness have made you desperate. Throw down your weapon, and listen to me; he who now addresses you is a man, possessing a heart that beats in sympathy for your misfortunes. I have both the means and the will to relieve your distress.'

The robber cast the stone from him, and burst into tears. 'Pardon me, kind stranger,' he cried, 'I did intend you harm, for my brain is burning, and my vitals consumed by starvation. You have spoken to me the first words of kindness that I have heard for a long, long time. You pity me, and that pity subdues me. I will go and seek some other victim.' 'Stay,' said Sydney, 'for heaven's sake give up this dreadful trade of robbery. Here is money, sufficient to maintain you for weeks—make a good use of it—seek employment—be honest, and should you need further assistance, call at —— Hotel, and ask for Francis Sydney. That is my name, and in me you will ever find a friend, so long as you prove yourself worthy.'

'Noble, generous man!' exclaim the robber, as he received a fifty dollar note from the hands of Frank. 'God will reward you for this. Believe me, I have not always been what I now am—a midnight ruffian, almost an assassin. No—I have had friends, and respectability, and wealth. But I have lost them all—all! We shall meet again—farewell!'

He ran rapidly from the spot, leaving Frank to pursue his way alone, and ponder upon this remarkable encounter.

Leaving the Park, and turning to the left, Frank proceeded up Chatham street towards the Bowery. As he was passing a house of humble but respectable exterior, he observed the street door to open, and a female voice said, in a low tone—'Young gentleman I wish to speak to you.'

Frank was not much surprised at being thus accosted, for his long residence in New York had made him aware of the fact that courtezans often resorted to that mode of procuring 'patronage' from such midnight pedestrians as might happen to be passing their doors. His first impulse was to walk on without noticing the invitation—but then the thought suggested itself to his mind: 'Might I not possibly be of some use or benefit to that frail one? I will see what she has to say.'

Reasoning thus, he stepped up to the door, when the female who had accosted him took him gently by the hand, and drawing him into the entry, closed the door. A lamp was burning upon a table which stood in the passage, and by its light Frank perceived that the lady was both young and pretty; she was wrapped in a large shawl, so that the outlines of her form were not plainly visible, yet it was easy to be seen that she was of good figure and graceful carriage.

'Madame, or Miss,' said Frank, 'be good enough to tell me why—'

'We cannot converse here in the cold,' interrupted the lady, smiling archly. 'Pray, sir, accompany me up-stairs to my room, and your curiosity shall be satisfied.'

Frank (who had his own reasons) motioned her to lead the way; she took the lamp[Pg 8] from the table, and ascended the staircase, followed by the young gentleman. The lady entered a room upon the second floor, in which stood a bed and other conveniences denoting it to be a sleeping chamber; a cheerful fire was glowing in the grate. The apartment was neatly and plainly furnished, containing nothing of a character to indicate that its occupant was other than a perfectly virtuous female. No obscene pictures or immodest images were to be seen—all was unexceptionable in point of propriety.

The lady closed and locked the chamber door; then placing two chairs before the fire, she seated herself in one, and requested Frank to occupy the other. Throwing off her shawl, she displayed a fine form and voluptuous bust—the latter very liberally displayed, as she was arrayed in nothing but a loose dressing gown, which concealed neither her plump shoulders, nor the two fair and ample globes, whiter than alabaster, that gave her form a luxurious fullness.

'You probably have sufficient discrimination, sir, to divine my motive in inviting you into this house and chamber,' began the young lady, not without some embarrassment. 'You will readily infer, from my conduct, that I belong to the unfortunate class—'

'Say no more,' said Frank, interrupting her, 'I can readily guess why you accosted me, and as readily comprehend your true position and character. Madame, I regret to meet you in this situation.'

The lady cast down her eyes, and made no immediate reply, but for some minutes continued to trace imaginary figures upon the carpet, with the point of her delicate slipper. Meanwhile, Frank had ample leisure to examine her narrowly. His eyes wandered over the graceful, undulating outlines of her fine form, and lingered admiringly upon the exposed beauties of her swelling bosom; he glanced at her regular and delicate features which were exceedingly girlish and pretty, for she certainly was not much over sixteen years of age. When it is remembered that Frank was a young man of an ardent and impulsive temperament, the reader will not be surprised that the loveliness of this young creature began to excite within his breast those feelings and desires which are inherent in human nature. In fact, he found himself being gradually overcome by the most tumultuous sensations: his heart palpitated violently, his breath grew hurried and irregular, and he could scarcely restrain himself from clasping her to his breast with licentious violence. His passions were still further excited, when she raised her eyes to his face, and glanced at him with a soft smile, full of tenderness and invitation. Frank Sydney was one of the best fellows in the world, and possessed a heart that beat in unison with every noble, generous and kindly feeling; but he was not an angel. No, he was human, and subject to all the frailties and passions of humanity. When, therefore, that enticing young woman raised her eyes, swimming with languishing desire, to his face, and smiled so irresistibly, he did precisely what ninety-nine out of every one hundred young men in existence would have done, in the same circumstances—he encircled her slender waist with his arm, drew her to his throbbing breast, and tasted the nectar of her ripe lips, which so plainly invited the salute. Ah Frank, Frank! thou hast gone too far to retract now! Thy hand plays with those ivory globes—thy lips[Pg 9] kiss those rounded shoulders, and that beauteous neck—thy brain becomes dizzy, thy senses reel, and thy amorous soul bathes in a sea of rapturous delight!

Truly, Frank Sydney, thou art a pretty fellow to prate about sallying forth at midnight to do good to thy fellow creatures!—Here we find thee, within an hour after thy departure from thy home, on an 'errand of mercy,' embraced in the soft arms of a pretty wanton, and revelling in the delights of voluptuousness. We might have portrayed thee as a paragon of virtue and chastity; we might have described thee as rejecting with holy horror the advances of that frail but exceedingly fair young lady—we might have made a saint of thee, Frank. But we prefer to depict human nature as it is not as it should be;—therefore we represent thee to be no better than thou art in reality. Many will pardon thee for thy folly, Frank, and admit that it was natural—very natural. Our hero did not return to his hotel until an hour after daybreak. The interval was passed with the young lady of frailty and beauty. He shared her couch; but neither of them slumbered, for at Frank's request, his fair friend occupied the time in narrating the particulars of her history, which we repeat in the succeeding chapter.

The Courtezan's story, showing some of the Sins of Religious Professors—A carnal Preacher, a frail Mother, and a lustful Father—a plan of revenge.

'My parents are persons of respectable standing in society;—they are both members of the Methodist Episcopal church, and remarkably rigid in their observance of the external forms and ceremonies of religion. Family worship was always adhered to by them, as well as grace before and after meals. They have ever been regarded as most exemplary and pious people. I was their only child; and the first ten years of my life were passed in much the same manner as those of other children of my sex and condition. I attended school, and received a good education; and my parents endeavored to instill the most pious precepts into my mind, to the end, they said, that I might become a vessel of holiness to the Lord. When I reached my twelfth year, a circumstance occurred which materially diminished my belief in the sanctity and godliness of one of my parents, and caused me to regard with suspicion and distrust, both religion and its professors.

'It was the custom of the pastor of the church to which my parents belonged, to make a weekly round of visits among the members of his congregation. These visits were generally made in the middle of the forenoon or afternoon, during the absence of the male members of the various families. I observed that 'our minister' invariably paid his visits to our house when my father was absent at his place of[Pg 10] business. Upon these occasions, he would hold long and private conferences with my mother, who used to declare that these interviews with that holy man did her more substantial good than all his preaching. 'It is so refreshing to my soul,' she would say, 'to pray in secret with that good man—he is so full of Christian love—so tender in his exhortations—so fervent in his prayers! O that I could meet him every day, in the sanctity of my closet, to strengthen my faith by the outpourings of his inexhaustible fount of piety and Christian love!'

'The wrestlings with the Lord of my maternal parent and her holy pastor, must have been both prolonged and severe, judging from the fact that at the termination of these pious interviews, my mother sometimes made her appearance with disordered apparel and disarranged hair; while the violence of her efforts to strengthen her faith was further manifest from the flushed condition of her countenance, and general peculiarity of aspect.

'One afternoon the Reverend Mr. Flanders—for that was the name of our minister—called to see my mother, and as usual they retired together to a private room, for 'holy communion.' Young as I was, my suspicions had long been excited in regard to the nature of these interviews; I began to think that their true object partook more largely of an earthly and carnal character, than either the pastor or my mother would care to have known. Upon the afternoon in question, I determined to satisfy myself on this point;—and accordingly, as soon as they entered the room and closed the door, (which they always locked,) I stole noiselessly up-stairs, and stationed myself in the passage, on the outside of the room, and listened intently. I had scarcely taken up my position, when my ear caught the sound of kissing; and applying my eye to the key-hole, I beheld the Rev. Mr. Flanders bestowing the most fervent embraces upon my mother, which she returned with compound interest. The pious gentleman, clasping her around the waist with one arm, proceeded to take liberties which astonished and disgusted me: and my mother not only permitted the revered scoundrel to do this, but actually seemed to encourage him. Soon they placed themselves upon a sofa, in full view of my gaze; and I was both mortified and enraged to observe the wantonness of my mother, and the lasciviousness of her pious friend. After indulging in the most obscene and lecherous preliminaries, the full measure of their iniquity was consummated, I being a witness to the whole disgraceful scene. Horrified, and sick at heart, I left the spot and repaired to my own room, where I shed many bitter tears, for the dishonor of my mother and the hypocrisy of the minister filled me with shame and grief. From that moment, I ceased to love and respect my mother, as formerly; but she failed to perceive any alteration in my conduct towards her, and at that time was far from suspecting that I had witnessed the act of her dishonor and disgrace.

'I had always regarded my father as one of the best and most exemplary of men; and after my mother's crime, I comforted myself with the reflection that he, at least, was no hypocrite! but in every sense a good and sincere Christian. Nothing happened to shake this belief, until I had reached my fourteenth year; and then, alas! I became too painfully convinced that all his professions of piety and holiness[Pg 11] were but a cloak to conceal the real wickedness of his heart. It chanced, about this time, that a young woman was received into our family, as a domestic: this person was far from being handsome or in the slightest degree interesting, in countenance—yet her figure was rather good than otherwise. She was a bold, wanton-looking wench; and soon after she came to live with us, I noticed that my father frequently eyed her with something sensual in his glances. He frequently sought opportunities of being alone with her; and one evening, hearing a noise in the kitchen, I went to the head of the stairs, and listened—there was the sound of a tussle, and I heard Jane (the name of the young woman,) exclaim—'Have done, sire—take away your hands—how dare you?' And then she laughed, in a manner that indicated her words were not very seriously meant. My father's voice next reached me; what he said I could not clearly distinguish; but he seemed to be remonstrating with the girl, and entreating her to grant him some favor; what that favor was, I could readily guess; and that she did grant it to him, without much further coaxing, was soon evident to my mind, by certain unmistakable sounds. But I preferred seeing to hearing; creeping softly down the kitchen stairs, I peeped in at the door, which was slightly ajar, and beheld my Christian papa engaged in a manner that reflected no credit on his observance of the seventh commandment.

'Thus having satisfied myself as to the nature and extent of his sanctity and holiness, I softly ascended the stairs, and resumed my seat in the parlor. In less than ten minutes afterwards, the whole family were summoned together around the family altar, and then my excellent and pious father poured out his pure spirit in prayer, returning thanks for having been 'preserved from temptation,' and supplicating that all the members of his household might flee from fleshy lusts, which war against the soul; to which my chaste and saint-like mother responded in a fervent 'Amen.' From that evening, the kitchen wench with whom my father had defiled himself, assumed an air of bold insolence to every one in the house; she refused to perform any of the menial services devolving upon her, and when my mother spoke of dismissing her, my father would not listen to it; so the girl continued with us. She had evidently obtained entire dominion over my father, and did not scruple to use her power to her own advantage; for she flaunted about in showy ribbons and gay dresses, and I had no difficulty in surmising who furnished her with the means of procuring them.

'I still continued to attend the church of the Rev. Mr. Flanders. He used to preach excellent sermons, so far as composition and style of delivery were concerned; his words were smooth as oil; his manner full of the order of sanctity; his prayers were fervid eloquence. Yet, when I thought what a consummate scoundrel and hypocrite he was at heart, I viewed him with loathing and disgust.

'I soon became sensible that this reverend rogue began to view me with more than an ordinary degree of interest and admiration; for I may say, without vanity, that as I approached my fifteenth year, I was a very pretty girl; my form had begun to develop and ripen, and my maiden graces were not likely to escape the lustful eyes of the elderly roues of our 'flock,' and seemed to be particularly attractive to that aged libertine known as the Rev. Balaam Flanders.[Pg 12]

'So far from being flattered by the attentions of our minister (as many of our flock were,) I detested and avoided him. Yet his lecherous glances were constantly upon me, whenever I was thrown into his society; even when he was in the pulpit, he would often annoy me with his lustful gaze.

'A bible class of young ladies was attached to the church, of which I was a member. We assembled at the close of divine service in the evening, for the study and examination of the Scriptures. Mr. Flanders himself had charge of this class, and was regarded by all the young ladies (myself excepted) as a 'dear, good man.' When one of us was particularly apt in answering a question or finding a passage, he would playfully chuck the good scholar under the chin, in token of his commendation; and sometimes, even, he would bestow a fatherly kiss upon the fair student of holy writ.

'These little tokens of his amativeness he often bestowed on me; and I permitted him, as I considered such liberties to be comparatively harmless. He soon however went beyond these 'attentions' to me—he first began by passing his hand over my bust, outside my dress, and, growing emboldened by my suffering him to do this, he would slide his hand into my bosom, and take hold of my budding evidences of approaching womanhood. Once he whispered in my ear—'My dear, what a delicious bust you have!' I was by no means surprised at his conduct or words, for his faux pas with my frail mother convinced me that he was capable of any act of lechery. I also felt assured that he lusted after me with all the ardor of his lascivious passions, and I well know that he waited but for an opportunity to attempt my seduction.—I hated the man, both for his adultery with my mother, and his vile intentions towards myself—and I determined to punish him for his lewdness and hypocrisy—yes, punish him through the medium of his own bad passions, and in a manner that would torture him with alternate hope and despair; now inspiring him with rapture by apparently almost yielding to his wishes, and then maddening him by my resistance—at the same time resolving not to submit to his desires in any case. This was my plan for punishing the hoary libertine, and you shall see how well I carried it out.

'I did not discourage my reverend admirer in his amorous advances, but on the contrary received them in such a manner as might induce him to suppose that they were rather pleasing to me than otherwise. This I did in order to ensure the success of my scheme—I observed with secret satisfaction that he grew bolder and bolder in the liberties which he took with my person. He frequently accompanied me home in the evening after prayer meeting; and he always took care to traverse the most obscure and deserted streets with me, so as to have a better opportunity to indulge in his licentious freedoms with me, unobserved. Not content with thrusting his hand into my bosom, he would often attempt to pursue his investigations elsewhere: but this I always refused to permit him to do. He was continually embracing and kissing me—and in the latter indulgence, he often disgusted me beyond measure, by the excessive libidinousness which he exhibited—I merely mention these things to show the vile and beastly nature of this man, whom the world regarded as a pure and holy minister of the gospel. Though old enough to[Pg 13] be my grandfather, the most hot blooded boy in existence could not have been more wanton or eccentric in the manifestations of his lustful yearnings. In fact, he wearied me almost to death by his unceasing persecution of me; yet I bore it with patience, so as to accomplish the object I had in view.

'I have often, upon the Sabbath, looked at that man as he stood in the pulpit; how pious he appeared, with his high, serene forehead, his carefully arranged gray hair, his mild and saint-like features, his snow-white cravat, and plain yet rich suit of glossy black! How calm and musical were the tones of his voice!—How beautifully he portrayed the happiness of religion, and how eloquently he prayed for the repentance and salvation of poor sinners! Yet how black was his heart with hypocrisy, and how polluted his soul with lust!

'One New Year's evening—I remember it well—my parents went to pay a visit to a relative a short distance out of the city, leaving me in charge of the house; the servants had all gone to visit their friends, and I was entirely alone. I had good reason to suppose that the Rev. Mr. Flanders would call on me that evening, as he knew that my parents would be absent. I determined to improve the opportunity, and commence my system of torture. Going to my chamber, I dressed myself in the most fascinating manner, for my wardrobe was extensive; and glancing in the mirror, I was satisfied of my ability to fan the flame of his passions into fury. I then seated myself in the parlor, where a fine fire was burning: and in a few minutes a hurried knock at the door announced the arrival of my intended victim. I ran down stairs and admitted him, and he followed me into the parlor, where he deliberately took off his overcoat, and then wheeling the sofa in front of the fire, desired me to sit by him. This I did, with apparent hesitation, telling him there was nobody in the house, and I wasn't quite sure it was right for me to stay alone in his company. This information, conveyed with a well assumed maiden bashfulness, seemed to afford the old rascal the most intense delight; he threw his arm around me, and kissed me repeatedly, then his hand began the exploration to which I have alluded. I suffered him to proceed just far enough to set his passions in a blaze; and then, breaking from his embrace, I took my seat at the further end of the sofa, assuring him if he approached me without my permission, I should scream out. This was agony to him; I saw with delight that he was beginning to suffer. He begged, entreated, supplicated me to let him come near me; and at last I consented; upon condition that he should attempt to take no further liberties. To this he agreed, and seating himself at my side, but without touching me, he devoured me with lustful eyes. For some minutes neither of us spoke, but at length he took my hand, and again passed his arm around my waist. I did not oppose him, but remained passive and silent. 'Dear girl,' he whispered, pressing me close to him—'why need you be so cruel as to deny me the pleasure of love? Consider, I am your minister, and cannot sin: it will therefore be no sin for you to favor me.'

'Oh, sir,' I answered, 'I wish you were a young man—then I could almost—'

'Angelic creature!' he cried passionately—'true, I am not young, but Love never grows old—no, no, no! Consent to be mine, sweet delicious girl, and—'

'Ah, sir!' I murmured—'you tempt me sorely—I am but a weak giddy young[Pg 14] creature; do not ask me to do wrong, for I fear that I may yield, and how very, very wicked that would be!'

'The reverend gentleman covered my cheeks and lips with hot kisses, as he said—'Wicked—no! Heaven has given us passions, and we must gratify them. Look at David—look at Solomon—both good men;—they enjoyed the delights of love, and are now saints in Heaven, and why may not we do the same? Why, my dear, it is the special privilege of the ministry to—'

'Ruin us young girls, sir?' I rejoined, smiling archly. 'Ah, you have set my heart in a strange flutter! I feel almost inclined—if you are sure it is not wicked—very sure—then I—'

'You are mine!' he exclaimed in a hoarse whisper, with frenzied triumph gleaming in his eyes. I never saw anybody look so fearful as he did then; his form quivered with intense excitement—his features appeared as if convulsed—his eyes, almost starting from their sockets, were blood shot and fiery. I trembled, lest in the madness of his passions, he might forcibly overcome me. He anticipated no resistance, imagining that he had an easy prey; but, at that very instant when he thought he was about to intoxicate his vile soul with the delicious draught of sensual delight, I spurned him from me as I would have spurned the most loathsome reptile that crawls amid the foetid horrors of a dungeon vault.—That was the moment of my triumph; I had led him step by step, until he felt assured of his ultimate success: I had permitted him to obtain, as it were, glimpses of a Paradise he was never to enjoy; and at the very moment he thought to have crossed the golden threshold, to enter into the blissful and flowery precincts of that Paradise, he was hurled from the pinnacle of his hopes, and doomed to endure the bitter pangs of disappointment, and the gnawings of a raging desire, never to be appeased!

'Thus repulsed, my reverend admirer did not resume his attempt, for my indignation was aroused, and he saw fierce anger flashing from my eyes. I solemnly declared, that had he attempted forcibly to accomplish his purpose, I would have dashed out his brains with the first weapon I could have laid my hand to!

'Humbled and abashed, he retired to a corner of the room, where he seated himself with an air of mortified disappointment. Yet still he kept his eyes upon me; and as I knew that his desires were raging as violently within him as ever (tho' he dare not approach me,) I devised the following method of augmenting his passions, and inflicting further torture upon him:—In my struggle with him, my dress had become somewhat disarranged and torn; and standing before a large mirror which was placed over the mantle-piece, I loosened my garments, and while pretending to examine the injury which had been done to them, I took especial pains to remove all covering from my neck, shoulders and bosom, which were uncommonly soft and white, as you, my dear, can testify. The sight of my naked charms instantly produced the desired effect upon the minister, who watched my slightest movement with eager scrutiny: he ceased almost to breathe, but panted—yes, absolutely panted—with the intensity of his passions.—Oh, how my heart swelled with delight at the agony he was thus forced to endure! Affecting to be unconscious of his presence, I assumed the most graceful and voluptuous attitudes I could think of[Pg 15]—and he could endure it no longer; for—would you believe it?—he actually fell upon his knees before me, and groveled at my feet, entreating me, in a hoarse whisper, to kill him at once and end his torments, or else yield myself to him!

'My revenge was now accomplished, and I desired no more. I requested him to arise from his abject posture, and listen to me. Then I told him all I knew of his hypocrisy and wickedness—how I had become aware of his criminal intercourse with my mother, which, combined with his vile conduct and intentions in regard to myself, had induced me to punish him in the manner I had done, by exciting his passions almost to madness, and then repulsing him with disdain. I added, maliciously, that my own passions were warm and ardent, and that my young blood sometimes coursed thro' my veins with all the heat of sensual desire—and that were a man, young and handsome, to solicit my favors, I might possibly yield, in a thoughtless moment: but as for him, (the minister) sooner than submit to his embraces, I would permit the vilest negro in existence, to take me in his arms, and do with me as he pleased.

'All this I told the Rev. Mr. Flanders, and much more; and after listening in evident misery to my remarks, he took himself from the house. After this occurrence, I discontinued my attendance at his church and bible class. When my parents asked me the reason of my nonattendance, I refused to answer them; and at length they became enraged at what they termed my obstinacy, and insisted that I should not fail to attend church on the following Sabbath.—When the Sabbath came, I made no preparation for going to church; which mother perceiving, she began to apply the most reproachful and severe language to me. This irritated me; and without a moment's reflection, I said to her angrily:

'I can well conceive, madam, the reason of your great partiality to the Rev. Mr. Flanders; your many private interviews with him have wonderfully impressed you in his favor!'

'Wretch, what do you mean?' stammered my mother in great confusion, and turning pale and red alternately.

'You know very well what I mean, vile woman!' I cried, enraged beyond all power of restraining my speech, and perfectly reckless of the consequences of what I was saying. 'I was a witness of your infamous adultery with the hypocritical parson, and—'

'As I uttered these words, my mother gave a piercing scream, and flew at me with the fury of a tigress. She beat me cruelly, tore my hair and clothes, and being a large and powerful woman, I verily believe she would have killed me, had not my father, hearing the noise, rushed into the room, and rescued me from her grasp. He demanded an explanation of this extraordinary scene, and, in spite of the threatening looks and fierce denial of my mother, I told him all. He staggered and almost fell to the floor, when I thus boldly accused her of the crime of adultery; clinging to a chair for support, he faintly ejaculated—'My God, can this be true?'

'It is false—I call Heaven to witness, it is false!' exclaimed my wretched and guilty mother—then, overcome by the terrors of the situation, she sank insensible upon the carpet. My father summoned a servant to her assistance; and then bade me[Pg 16] follow him into another room. Carefully closing the doors, he turned to me with a stern aspect, and said, with much severity of tone and manner:

'Girl, you have made a serious charge against your mother; you have impugned her chastity and her honor. Adultery is the most flagrant crime that can stain the holy institution of marriage. If I believed your mother guilty of it, I would cast her off forever!'

'I laughed scornfully as he said this, whereupon he angrily demanded the cause of my ill-timed mirth; and as I detested his hypocrisy, I boldly told him that it ill became him to preach on the enormity of the crime of adultery, after having been guilty of that very offence with his kitchen wench! He turned deadly pale at this unexpected retort, and stammered out—'Then you know all—denial is useless.' I told him how I had witnessed the affair in the kitchen, and reproached him bitterly for the infamous conduct. He admitted the justness of my rebuke, and when I informed him that Mr. Flanders had attempted to debauch me, he foamed with rage, and loaded the reverend libertine with epithets which were decidedly uncomplimentary. Still, he doubted the story of my mother's crime—he could not believe her to be guilty of such baseness; but he assured me that he should satisfy himself of her innocence or guilt, then left me, after having made me promise not to expose him in reference to his affair with the servant girl in the kitchen.

'Upon leaving me, my father immediately sought an interview with my mother, who by this time had recovered from her swoon. She was in her chamber; but as I was naturally anxious to know what might pass between my parents, under such unusual circumstances, I stationed myself at the door of the room, as soon as my father had entered, and heard distinctly all that was said.'

Domestic Troubles—A Scene, and a Compromise—an Escape—various matters amative, explanatory and miscellaneous, in the Tale of the Courtezan.

'Well, madam,' said my father, in a cold, severe tone—'this is truly a strange and serious accusation which our daughter has brought against you. The crime of adultery, and with a Christian minister!'

'Surely,' rejoined my mother, sobbing—'you will not believe the assertions of that young hussy. I am innocent—indeed, indeed I am.'

'I am inclined to believe that you are innocent, and yet I never shall rest perfectly satisfied until you prove yourself guiltless in this matter,' rejoined my father, speaking in a kinder tone. 'Now listen to me,' he continued. 'I have thought of a plan by which to put your virtue, and the purity of our pastor, to the test. I shall invite the reverend gentleman to dinner this afternoon, after divine service; and when we have dined, you shall retire with him to this room, for private prayer. You shall go first, and in a few minutes he shall follow you; and I shall take care that no[Pg 17] secret communication is held between you, in the way of whispering or warnings of any kind, whether by word or sign. I will contrive means to watch you narrowly, when you are with him in the chamber; and I caution you to beware of giving him the slightest hint to be on his guard, for that would be a conclusive evidence of your guilt. He will of course conduct himself as usual, not knowing that he is watched. If you are innocent, he will pray or converse with you in a Christian and proper manner; but if you ever have had criminal intercourse with him, he will, in all human probability, indicate the same in his language and actions. This is most plain; and I trust that the result will clear you of all suspicion.'

'My mother knew it would be useless to remonstrate, for my father was unchangeable, when once he had made up his mind to anything. She therefore was obliged to submit. Accordingly, Mr. Flanders dined with us that day: once, during the meal, happening to look into his face, I saw that he was gazing at me intently, and I was startled by the expression of his countenance: for that expression was one of the deadliest hate. It was but for an instant, and then he turned away his eyes; yet I still remember that look of bitter hatred. As soon as dinner was over, my mother withdrew, and a few minutes afterwards my father said to the minister:

'Brother Flanders, I am going out for a short walk, to call upon a friend; meantime, I doubt not that Mrs. —— will be happy to hold sisterly and Christian communion with you. You will find her in her chamber.'

'It is very pleasant, my brother,' responded the other—'to hold private and holy communion with our fellow seekers after divine truth. These family visits I regard as the priceless privilege of the pastor; by them the bond of love which unites him to his flock, is more strongly cemented. I will go to my sister and we will pray and converse together.'

'Saying this, Mr. Flanders arose and left the room; he had scarcely time to ascend the stairs and enter my mother's chamber, when my father quickly and noiselessly followed him, and entered an apartment adjoining. He had previously made a small hole in the wall, and to this hole he applied his eye. So rapid had been his movements, that the minister had just closed the door, when he was at his post of observation; so that it was rendered utterly impossible for my mother to whisper a word or make a sign, to caution her paramour against committing both her and himself. I lost no time in taking up my position at the chamber door, and availed myself of the keyhole as a convenient channel for both seeing and hearing. I saw that my mother was very pale and seemed ill at ease, and I did not wonder at it, for her position was an extremely painful and embarrassing one. She well knew that my father's eye was upon her, watching her slightest movement; she knew, also, that the minister was utterly unaware of my father's espionage, and she had good reason to fear that the reverend libertine would, as usual, begin the interview by amorous demonstrations. Oh, how she must have longed to put him on his guard, and thereby save both her honor and her reputation!—But she dare not.

'The minister seated himself near my unhappy mother, and opened the conversation as follows:

'Well, my dear Mrs. ——, I am sorry to inform you that I have tidings of an unpleasant nature to communicate to you. We are discovered!'[Pg 18]

'These fatal words were uttered in a low whisper; but yet I doubt not that my father had heard them. I could see that my mother trembled violently—yet she spoke not a syllable.

'Yes,' continued the minister, all unconscious of the disclosure he was making to my father—'Your daughter knows all. She suspected, it seems, the real object of our last interview, when, you recollect, we indulged in a little amative dalliance.—On New Year's evening, during your absence, I called here and saw your daughter, when she reproached me for having debauched you, stating in what manner she had seen the whole affair. Since then, I have had no opportunity of informing you that she knew our intimacy.'

'Still my mother uttered not a single word!'

'This girl,' continued the minister,'must be made to hold her tongue, somehow or other: it would be dreadful to have it reach your husband's ears. But why are you so taciturn to-day, my dear? Come, let us enjoy the present, and dismiss all fear for the future. But first we must make sure that there are no listeners this time,' and he approached the door.

'I retreated precipitately, and slipped into another room, while he opened the chamber; seeing no-one on the outside, he closed it again, and locked it. I instantly resumed my station; and I saw the minister approach my mother, (who appeared spell-bound,) and clasp her in his arms. He was about to proceed to the usual extreme of his criminality when my father uttered an expression of rage; I instantly ran into the room which had before served me as a hiding place, and in a moment more my father was at the door of my mother's chamber, demanding admission. After a short delay, the door was opened; and then a scene ensued which defies my powers of description.

''Tis needless to dwell upon the particulars of what followed. My father raved, the pastor entreated, and my mother wept. But after an hour or so, the tempest subsided; the parties arriving at the reasonable conclusion, that what was done could not be undone. Finally it was arranged that Mr. Flanders should pay my father a considerable sum of money, upon condition that the affair be hushed up.—My mother was promised forgiveness for her fault—and as I was the only person likely to divulge the matter, it was agreed that I should be placed under restraint, and not suffered to leave the house, until such time as I should solemnly swear never to reveal the secret of the adultery.—Accordingly, for one month I remained a close prisoner in the house, and at the end of that period, not feeling inclined to give the required pledge of secrecy, I determined to effect my escape, and leave my parents forever.—The thought of parting from them failed to produce the least impression of sadness upon my mind, for from the moment I had discovered the secret of their guilty intrigues, all love and respect for them had ceased. I knew it would be no easy matter for me to depart from the house unperceived, for the servant wench, Janet, was a spy upon my actions; but one evening I contrived to elude her observation, and slipping out of the door, walked rapidly away. What was to become of me, I knew not, nor cared, in my joy at having escaped from such an abode of hypocrisy as my parents' house—for of all the vices which can disgrace humanity, I regard hypocrisy as the most detestable.[Pg 19]

'Fortunately, I had several dollars in my possession; and I had no difficulty in procuring a boarding house. And now as my story must be getting tedious by its length, I will bring it to a close in as few words as possible. I supported myself for some time by the labor of my needle; but as this occupation afforded me only a slight maintenance, and proved to be injurious to my health, I abandoned it, and sought some other employment. It was about that time that I became acquainted with a young man named Frederick Archer, whose manners and appearance interested me exceedingly, and I observed with pleasure that he regarded me with admiration. Our acquaintance soon ripened into intimacy; we often went to places of amusement together, and he was very liberal in his expenditures for my entertainment. He was always perfectly respectful in his conduct towards me, never venturing upon any undue familiarity, and quite correct in his language. One evening I accompanied him to the Bowery Theatre, and after the play he proposed that we should repair to a neighboring 'Ladies Oyster Saloon,' and partake of refreshments. We accordingly entered a very fashionable place, and seated ourselves in a small room, just large enough to contain a table and sofa.—The oysters were brought, and also a bottle of champagne; and then I noticed that my companion very carefully locked the door of the room. This done, he threw his arms around me, and kissed me. Surprised at this liberty, which he had never attempted before, I scolded him a little for his rudeness; and he promised not to offend again. We then ate our oysters, and he persuaded me to drink some of the wine. Whether it contained a stimulant powder, or because I had never drank any before, I know not; but no sooner had I swallowed a glass of the sparkling liquid, than a strange dizzy sensation pervaded me—not a disagreeable feeling, by any means, but rather a delightful one. It seemed to heat my blood, and to a most extraordinary degree. Rising, I complained of being slightly unwell, and requested Frederick to conduct me out of the place immediately. Alas, sir, why need I dwell upon what followed? Frederick's conquest was an honest one; I suffered him to do with me as he pleased, and he soon initiated me into the voluptuous mysteries of Venus. I confess, I rather sought than avoided this consummation—for my passions were in a tumult, which could only be appeased by full unrestrained gratification.

'From that night my secret frailties with Frederick became frequent. I granted him all the favors he asked; yet I earnestly entreated him to marry me. This he consented to do, and we were accordingly united in the bonds of wedlock. My husband immediately hired these furnished apartments, which I at present occupy; and then he developed a trait in his character, which proved him a villain of the deepest dye. How he made a livelihood, had always to me been a profound mystery; and as he avoided the subject, I never questioned him. But how he intended to live, after our marriage, I soon became painfully aware. He resolved that I should support him in idleness, by becoming a common prostitute. When he made this debasing and inhuman proposition to me, I rejected it with the indignation it merited; whereupon he very coolly informed me, that unless I complied, he should abandon me to my fate, and proclaim to the world that I was a harlot before he married me. Finding me still obstinate, he drew a bowie knife, and swore a terrible oath, that[Pg 20] unless I would do as he wished, he would kill me! Terrified for my life, I gave the required promise; but he made me swear upon the Bible to do as he wished. He set a woman in the house to watch me during the day, and prevent my escaping, and in the evening he returned, accompanied by an old gentleman of respectable appearance, whom he introduced to me as Mr. Rogers. This person surveyed me with an impertinent stare, and complimented me on my beauty; in a few minutes, Frederick arose and said to me—'Maria, I am going out for a little while, and in the meantime you must do your best to entertain Mr. Rogers.' He then whispered in my ear—'Let him do as he will with you, for he has paid me a good price; now don't refuse him, or be in the least degree prudish, or by G—— it shall be worse for you!' Scarcely had he taken his departure, when the old wretch, who had purchased me, clasped me in his palsied arms, and prepared to debauch me; in reply to my entreaties to desist, and my appeals to his generosity, he only shook his head, and said—'No, no, young lady, I have given fifty dollars for you, and you are mine!' The old brute had neither shame, nor pity, nor honor in his breast; he forced me to comply with his base wishes, and a life of prostitution was for the first time opened to me.

'After this event, I attempted no further opposition to my husband's infamous scheme of prostituting myself for his support. Almost nightly, he brought home with him some friend of his, who had previously paid him for the use of my person. The money he gains in this way he expends in gambling and dissipation; allowing me scarcely anything for the common necessaries of life, and I am in consequence obliged to solicit private aid from such gentlemen as are disposed to enjoy my favors. My husband rarely sleeps at home, and I see but very little of him; this is a source of no regret to me, for I have ceased to feel the slightest regard for him.

'And now, sir, you have heard the particulars of my history. You will do me the justice to believe that I have been reduced to my present unfortunate position, more through the influence of circumstances, than on account of any natural depravity.—True, I am now what is termed a woman of the town—but still I am not entirely destitute of delicacy or refinement of feeling. I am an admirer of it in others. My parents I have never seen, since the day I quitted their house; but I have heard that my mother has since given birth to a fine boy, the very image of the minister; and also that Jane, my father's paramour, has become the mother of a child bearing an astonishing resemblance to the old gentleman himself!

'If you ask me why I do not escape from my husband, and abandon my present course of living, I would remind you that, as society is constituted, I never can regain a respectable standing in the eyes of the world. No, my course is marked out, and I must adhere to it. I am not happy, neither am I completely miserable; for sometimes I have my moments of enjoyment. When I meet a gentlemanly and intelligent companion, like yourself, disposed to sympathize with the misfortunes of a poor and friendless girl, I am enabled to bear up under my hard lot with something like cheerfulness and hope.'

Thus ended the Courtezan's Tale; and as it was now daylight, Frank Sydney arose and prepared for his departure, assuring her that he would endeavor to[Pg 21] benefit her in some way, and generously presenting her with a liberal sum of money, for which she seemed truly grateful. He then bade her farewell, promising to call and see her again ere long.

A Fashionable Lady—the Lovers—the Negro Paramour—astounding developments of Crime in High Life—the Accouchement—Infanticide—the Marriage—a dark suspicion.

The scene changes to that superb avenue of fashion, Broadway; the time, eleven o'clock in the morning, and the place, one of the noblest mansions which adorn that aristocratic section of the city.

Miss Julia Fairfield was seated in a luxurious apartment, lounging over a late breakfast, and listlessly glancing over the morning newspapers.

This young lady was about eighteen years of age, a beauty, an heiress, and, per consequence, a belle. She was a brunette; her beauty was of a warm, majestic, voluptuous character; her eyes beamed with the fire of passion, and her features were full of expression and sentiment. Her attire was elegant, tasteful, and unique, consisting of a loose, flowing robe of white satin, trimmed with costliest lace; her hair was beautifully arranged in the best Parisian style; and her tiny feet were encased in gold-embroidered slippers. The peculiarity of her dress concealed the outlines of her form; yet the garment being made very low in the shoulders, the upper portions of a magnificently full bust were visible.

For some time she continued to sip her chocolate and read in silence; but soon she exclaimed, in a rich, melodious voice—

'Very well, indeed!—and so those odious editors have given the full particulars of the great ball last night, and have complimented me highly on my grace and beauty! Ah, I never could have ventured there in any other costume than the one I wore. These loose dresses are capital things—but my situation becomes more and more embarrassing every day.'

At this moment a domestic announced Mr. Francis Sydney, and the announcement was followed by the entrance of that gentleman.

'My dear Julia,' said Frank, seating himself—'you will pardon my intrusion at this unfashionable hour, but I was anxious to learn the state of your health, after the fatigues of last night's assembly.'

'No apology is necessary, my dear Frank,' replied the lady, with a bewitching smile, at the same time giving him her hand, which he tenderly raised to his lips. 'I am in excellent health this morning, although dreadfully bored with ennui, which I trust will be dispelled by the enlivening influence of your presence.'

'What happiness do I derive from the reflection, my sweet girl,' said Frank, drawing his chair closer to hers, 'that, in one short month, I shall call you mine! Yes, we shall then stand before the bridal altar, and I shall have the felicity of wedding the loveliest, most accomplished, and purest of her sex!'[Pg 22]

'Ah, Francis,' sighed the lady—'how joyfully will I then bestow upon you the gift of this hand!—my heart you have already.'

These words were said with so much tenderness, and with such a charming air of affectionate modesty, that the young man caught her to his breast and covered her lips with kisses. Struggling from his ardent embrace, Julia said to him, in a tone of reproach,—

'Francis, this is the first time you ever forgot the respect due to me as a lady; but do not repeat the offense, or you will diminish my friendship for you—perhaps, my love also.—When we are married,' she added, blushing—'my person will be wholly yours—but not till then.'

'Pardon me, dear Julia,' entreated Frank, in a tone of contrition—'I will not offend again.'

The lady held out her hand, and smiled her forgiveness.

'Now that we are good friends again,' said she—'I will order some refreshments.' She rang a silver bell, and gave the necessary order to a servant, and in a few minutes, cake and wine were brought in by a black waiter, clad in rich livery. The complexion of this man was intensely dark, yet his features were good and regular and his figure tall and well-formed. In his demeanor towards his mistress and her guest, he was respectful in the extreme, seldom raising his eyes from the carpet, and when addressed, speaking in the most servile and humble tone.

After having partaken of the refreshments, and enjoyed half an hour's conversation, Frank arose and took his leave.

As soon as he had gone, an extraordinary scene took place in that parlor.

The black waiter, having turned the key within the lock of the door, approached Miss Fairfield, deliberately threw his arms around her, and kissed her repeatedly! And how acted the lady—she who had reproved her affianced husband for a similar liberty—how acted she when thus rudely and grossly embraced by that black and miscreant menial? Did she not repulse him with indignant disgust,—did she not scream for assistance, and have him punished for the insolent outrage?

No; she abandoned her person to his embraces, and returned them! She, the well-born, the beautiful, the wealthy, the accomplished lady—the betrothed bride of a young gentleman of honor—the daughter of an aristocrat—the star of a constellation of fashion—yielding herself to the arms of a negro servant!

Oh, woman! how like an angel art thou in thy virtue and goodliness! how like a devil, when thou art fallen from thy high estate!

Yes, that black fellow covers her exquisite neck and shoulders with lustful kisses! His hands revel amid the glories of her divine and voluptuous bosom; and his lips wander from her rosy mouth, to the luxurious beauties of her finely developed bust.

'My beautiful mistress!' said the black, 'how kind in you to grant me these favors! What can I do to testify my gratitude?'

'Oh Nero,' murmured the lady 'what if our intimacy should be discovered? yet you are discreet and trustworthy; for from the night I first hinted my desires to you, and admitted you into my chamber, you have behaved with prudence and caution. Yet you are aware of my situation; you know that I am enciente by you; all our precautions have failed to prevent that result of our amours. I dress myself in such[Pg 23] a way as to keep my condition from observation; no one suspects it. In a month, you know, I am to be married to Mr. Sydney; but I hope to give birth to the child in less than a week from the present time, so that, with good care and nursing, assisted by my naturally robust constitution, I shall recover my health and strength in sufficient time to enable my marriage to pass on without suspicion. I will endeavor to adopt such artifices and precautions as will completely deceive my husband, and he will never know that I am otherwise than he now supposes me. After my marriage, we can continue our intrigues as before, provided we are extremely cautious. Ah, my handsome African, how dearly I love you.'

The guilty and depraved woman sank back upon a sofa, and her paramour clasped her in his arms.

Let no one say that our narrative is becoming too improbable for belief, that the scenes which we depict find no parallel in real life. Those who are disposed to be skeptical with reference to such scenes as the foregoing had better throw this volume aside; for crimes of a much deeper dye, than any yet described, will be brought forward in this tale: crimes that are daily perpetrated, but which are seldom discovered or suspected. We have undertaken a difficult and painful task, and we shall accomplish it; unrestrained by a false delicacy, we shall drag forth from the dark and mysterious labyrinths of great cities, the hidden iniquities which taint the moral atmosphere, and assimilate human nature to the brute creation.

Five days after the occurrences just described, in the middle of the afternoon, Miss Julia Fairfield rode out in her carriage alone, driven by the black, Nero. The vehicle stopped before a house of respectable exterior, in Washington street, and the young lady was assisted to alight; entering the house, she was received by an elderly female, who immediately conducted her to a private room, which contained a bed and furniture of a neat but unostentatious description. The carriage drove away, and Julia remained several hours in the house. At about nine o'clock in the evening, the carriage returned, and she was assisted to enter, being apparently in a very feeble and unwell condition. She reached her own dwelling, and for over a week remained in her chamber, under plea of severe indisposition. When at length she made her appearance, she looked extremely pale, and somewhat emaciated; yet, for the first time in several months, she wore a tight-fitting dress, and her father, unconscious of her crimes, good-naturedly expressed his joy at seeing her 'once more dressed like a Christian lady, and not in the loose and slatternly robes she had so long persisted in wearing.'

The next morning after her visits to the house on Washington Street, the newspapers contained a notice of the discovery of the body of a newborn mulatto child, in the water off the Bowery. That child was the offspring of Miss Julia and the black; it had been strangled, and its body thrown into the water.

About three weeks after her secret accouchement, Julia became the wife of Frank Sydney. An elegant establishment had been prepared for the young couple, in Broadway. Here they repaired after the performance of the marriage ceremony; and now being for the first time alone with his beautiful bride, Frank embraced her with passionate ardor, and was not repulsed.

Ah, happy bridegroom, how little thou knowest the truth! Thou dost not sus[Pg 24]pect that the lovely woman at thy side, dressed in spotless white, and radiant with smiles—thou dost little think that she, whom thou hast taken to be thy wedded wife, comes to thy arms and nuptial bed, not a pure and stainless virgin, but a wretch whose soul is polluted and whose body is unchaste, by vile intimacy with a negro menial!

The hour waxes late, and the impatient husband conducts his fair bride to the nuptial chamber—Love's hallowed sanctuary.

Two hours afterwards, that husband was pacing a parlor back and forth, with uneven strides, his whole appearance indicative of mental agony.—Pausing, he exclaimed—

'My God, what terrible suspicions cross my mind! I imagined Julia to be an angel of purity and virtue yet now I doubt her! Oh, horrible, horrible! But may not my doubts be facts without any foundation? I will tomorrow consult a physician on the subject. Pray heaven my suspicions may prove to be utterly groundless!'

He was startled by the sound of an approaching foot-step; the door opened, and his wife entered, bearing a light. How seductive she looked, in her white night-dress! how tenderly she caressed him, as with affectionate concern she inquired if he were unwell.

'Dearest Frank,' she said, 'I had fallen into the most delicious slumber I have ever enjoyed;—doubly delicious, because my dreams were of you. Awaking suddenly, I missed you from my arms, and hastened hither to find you. What is the matter, love?'

'Nothing, Julia,' answered the husband; 'I had a slight head-ache, but it is over now. Return to your chamber, and I will follow you in a few moments.'

She obeyed, and Frank was alone. 'Either that woman is as chaste as Diana,' he said to himself, 'or she is a consummate wretch and hypocrite. But let her not be too hastily condemned. My friend, Dr. Palmer, shall give me his opinion, and if he thinks that she could have been as she was, and still be chaste, then I will discard my suspicions; but if, on the contrary, the doctor deems such a condition to be incompatible with chastity, then will I cast her off forever. I cannot endure this fearful state of suspense, would that it were morning!'

Morning came at last, and Sydney sought the residence of Dr. Palmer, with whom he held a long and private consultation. The result of this interview was not very satisfactory to the husband, for the doctor's concluding remarks were as follows:—

'My dear sir, it is impossible for any physician, however great may be his professional knowledge and experience, to decide with positive certainty upon such a matter. Nature has many freaks; the condition of your lady might be natural—yet pardon me if, in my own private opinion, I doubt its being so! I have heard of such cases, where the chastity of the lady was undoubted; yet such cases are exceedingly rare. Your position, Mr. Sydney, is a peculiarly embarrassing and delicate one. I cannot counsel you as a physician; yet, as a friend, permit me to advise you to refrain from acting hastily in this matter. Your wife may be innocent; you should consider her so, until you have ocular or other positive evidence of her guilt. Meanwhile, let her not know your suspicions, but watch her narrowly; if she were frail before[Pg 25] marriage, she needs but the opportunity to be inconstant afterwards. I have attended upon the lady several times, during slight illness, in my capacity as a physician, and I have had the opportunity to observe that she is of an uncommonly ardent and voluptuous temperament. Phrenology confirms this; for her amative developments are singularly prominent.—Candidly, her physical conformation strongly impresses me with the belief, that moral principle will scarcely restrain her from unlawful indulgence, when prompted by inclination.'

'The devil!' muttered Frank, as he retraced his steps home—'I am about as wise as ever! A pretty opinion Dr. Palmer expresses of her, truly! Well, she shall have the benefit of a doubt, and I shall try to look upon her as an innocent woman, until I detect her in an act of guilt. Meanwhile, she shall be watched narrowly and constantly.'

Frank's suspicions with reference to his newly-made wife, did not prevent his carrying out the plan of benevolence which he formed in the first chapter of this narrative. Adopting various disguises, he would penetrate into the most obscure and dangerous quarters of the city, at all hours of the day and night. The details of many of these secret adventures will be hereafter related.

A Thieves' Crib on the Five Points—Bloody Mike—Ragged Pete—the Young Thief, and the stolen Letters—The Stranger—a general Turn-out-Peeling a Lodger—the 'Forty-Foot Cave.'

It was a dreary winter's night, cold, dark, and stormy. The hour was midnight; and the place, the 'Five Points.'

The narrow and crooked streets which twine serpent-like around that dreaded plague spot of the city were deserted; but from many a dirty window, and through many a red, dingy curtain, streamed forth into the darkness rages of ruddy light, while the sounds of the violin, and the noise of Bacchanalian orgies, betokened that the squalid and vicious population of that vile region were still awake.

In the low and dirty tap-room of a thieves' crib in Cross street, are assembled about a dozen persons. The apartment is twenty feet square, and is warmed by a small stove, which is red-hot; a roughly constructed bar, two or three benches, and a table constitute all the furniture. Behind the bar stands the landlord, a great, bull-necked Irishman, with red hair, and ferocious countenance, the proprietor of the elegant appropriate appellation of 'Bloody Mike.' Upon the table are stretched two men, one richly dressed, and the other in rags—both sound asleep. Beneath the table lay a wretched-looking white prostitute, and a filthy-looking negro—also asleep. The remainder of the interesting party are seated around the stove, and sustain the following dialogue:

'Well, blow me tight,' said one, 'if ever I seed such times as these afore! Why,[Pg 26] a feller can't steal enough to pay for his rum and tobacco. I haven't made a cent these three days. D——n me if I ain't half a mind to knock it off and go to work!'

The speaker was a young man, not over one and twenty years of age; yet he was a most wretched and villainous looking fellow. His hair was wild and uncombed; his features bloated and covered with ulcers; his attire miserable and ragged in the extreme; and sundry sudden twitchings of his limbs, as well as frequent violent scratchings of the same, indicated that he was overrun with vermin. This man, whose indolence had made him a common loafer, had become a petty thief; he would lurk around backyards and steal any article he could lay his hands to—an axe, a shovel, or a garment off a line.

'What you say is true enough, Ragged Pete,' said a boy of about fourteen, quite good looking, and dressed with comparative neatness. 'A Crossman has to look sharp now-a-days to make a boodle. And he often gets deceived when he thinks he has made a raise. Why the other day I cut a rich looking young lady's reticule from her arm in Broadway and got clear off with it; but upon examining my prize, I found it contained nothing but a handkerchief and some letters. The wipe I kept for my own use; as for the letters, here they are—they are not worth a tinker's d——n, for they are all about love.'

As he spoke, he carelessly threw upon the table several letters, which were taken up and examined by Ragged Pete, who being requested by others to read aloud, complied, and opening one, read as follows:—

'Dear Mistress,—Since your marriage, I have not enjoyed any of those delicious private tete-a-tetes with you, which formerly afforded us both so much pleasure. Send me word when I can find you alone, and I will fly to your arms.

'Your ever faithful Nero'

'By Jesus!' exclaimed Bloody Mike—'it's a mighty quare name me gentleman signs himself, any how. And it's making love to another man's wife he'd be, blackguard! Devil the much I blame him for that same, if the lady's continted!'

'Here,' said Ragged Pete, taking up another letter, 'is one that's sealed and directed, and ain't been broke open yet. Let's see what it says.'

Breaking the seal, he read aloud the contents, thus:—

'Dear Nero,—I am dying to see you, but my husband is with me so constantly that 'tis next to impossible. He is kind and attentive to me, but oh! how infinitely I prefer you to him! I do not think that he has ever suspected that before my marriage, I * * * Fortunately for us, Mr. Sydney has lately been in the habit of absenting himself from home evenings, often staying out very late. Where he goes I care not, tho' I suspect he is engaged in some intrigue of his own; and if so, all the better for us, my dear Nero.

'Thus I arrange matters; when he has gone, and I have reason to think he will not soon return, a light will be placed in my chamber window, which is on the extreme left of the building, in the third story. Without this signal, do not venture into the house. If all is favourable my maid, Susan (who is in our secret,) will admit you by the back gate, when you knock thrice. Trusting that we may meet soon, I remain, dear Nero,

'Your loving and faithful JULIA.'

'Hell and furies!' exclaimed one of the company, starting from his seat, and seizing the letter; he ran his eye hastily over it, and with a groan of anguish, sank back upon the bench.

The person who manifested this violent emotion, was a young man, dressed in a mean and tattered garb, his face begrimed corresponding with that of the motley crew by which he was surrounded. He was a perfect stranger to the others present, and had not participated in their previous conversation, nor been personally addressed by any of them.

Bloody Mike, the landlord, deeming this a fit opportunity for the exercise of his authority, growled out, in a ferocious tone—

'And who the devil may ye be, that makes such a bobbaboo about a letter that a kinchen stales from a lady's work bag? Spake, ye blasted scoundrel; or wid my first, (and it's no small one) I'll let daylight thro' yer skull! And be what right do ye snatch the letter from Ragged Pete? Answer me that ye devil's pup!'

All present regarded the formidable Irishman with awe, excepting the stranger, who gazed at him in contemptuous silence. This enraged the landlord still more, and he cried out—

'Bad luck to ye, who are ye, at all at all? Ye're a stranger to all of us—ye haven't spint a pinney for the good of the house, for all ye've been toasting yer shins furnist the fire for two hours or more! Who knows but ye're a police spy, an officer in disguise, or—'

'Oh, slash yer gammon, Bloody Mike,' exclaimed the stranger, speaking with a coarse, vulgar accent—'I know you well enough, tho' you don't remember me. Police spy, hey? Why, I've just come out of quod myself, d'y see—and I've got tin enough to stand the rum for the whole party. So call up, fellers—what'll ye all have to drink?'

It is impossible to describe the effect of these words on everybody present. Bloody Mike swore that the stranger was a 'rare gentleman', and asked his pardon; Ragged Pete grasped his hand in a transport of friendship; the young thief declared he was 'one of the b'hoys from home;' the negro and the prostitute crawled from under the table, and thanked him with hoarse and drunken voices; the vagabond and well-dressed man on the table, both rolled off, and 'called on.' And the stranger threw upon the counter a handful of silver, and bade them 'drink it up.'

Such a scene followed! Half pints of 'blue ruin' were dispensed to the thirsty throng, and in a short time all, with two or three exceptions, were extremely drunk. The negro and the prostitute resumed their places under the table; the well-dressed man and his ragged companion stretched themselves upon their former hard couch; and Ragged Pete ensconced himself in the fireplace, with his head buried in the ashes and his heels up the chimney, in which comfortable position he vainly essay'd to sing a sentimental song, wherein he [illegible word] to deplore the loss of his 'own true love.' (The only sober persons were the stranger, the young thief and the Irish landlord.) The two former of these, seated in one corner, conversed together in low whispers.

'See here, young feller,' said the stranger—'I've taken a fancy to them two[Pg 28] letters, and if you'll let me keep 'em, here's a dollar for you.' The boy readily agreed, and the other continued:

'I say, there's a rum set o' coves in this here crib, ain't there? Who is that well-dressed chap on the table?'

'That,' said the boy, 'is a thief who lately made a large haul, since which time he has been cutting a tremendous swell—but he spent the whole thousand dollars in two or three weeks, and his fine clothes is all that remains. In less than a week he will look as bad as Ragged Pete.'

'And what kind of a cove is the landlord, Bloody Mike?' asked the stranger.

'He is the best friend a fellow has in the world, as long as his money lasts,' replied the boy. 'The moment that is gone, he don't know you. Now you'll see in a few moments how he'll clear everybody out of the house except such as he thinks has money. And, 'twixt you and me, he is the d——dst scoundrel out of jail, and would as lief kill a man as not.'