This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Rosin the Beau

Author: Laura Elizabeth Howe Richards

Release Date: December 24, 2008 [eBook #27607]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROSIN THE BEAU***

| CAPTAIN JANUARY | $ .50 |

| Same. Illustrated Holiday Edition. | 1.25 |

| Same. Centennial Edition Limited. | 2.50 |

| MELODY | .50 |

| Same. Illustrated Holiday Edition. | 1.25 |

| MARIE | .50 |

| ROSIN THE BEAU | .50 |

| NARCISSA | .50 |

| SOME SAY | .50 |

| JIM OF HELLAS | .50 |

| SNOW WHITE | .50 |

Melody, My Dear Child:

When people ask me where I hail from, our good, neighbourly, down-east way, I answer "From the Androscoggin;" and that is true enough as far as it goes, for I have spent many years on and about the banks of that fine river; but I have told you more than that. You know something of the little village where I was born and brought up, far to the northeast of your own home village. You know something, too, of my second mother, as I call her,—Abby Rock; but of my own sweet mother I have spoken little. Now you shall hear.[8]

The first thing I can remember is my mother's playing. She was a Frenchwoman, of remarkable beauty and sweetness. Her given name was Marie, but I have never known her maiden surname: I doubt if she knew it herself. She came, quite by accident, being at the time little more than a child, to the village where my father, Jacques De Arthenay, lived; he saw her, and loved her at the sight. She consented to marry him, and I was their only child. My father was a stern, silent man, with but one bright thing in his life,—his love for my mother. Whenever she came before his eyes, the sun rose in his face, but for me he had no great affection; he was incapable of dividing his heart. I have now and then seen a man with this defect; never a woman.

My first recollection, I said, is of my mother's playing. I see myself, sitting on a great black book, the family Bible. I must have been very small, and it was a large Bible, and lay on a table in the sitting-room. I see my mother standing before me, with her violin on her arm. She is light, young, and very graceful; beauty seems to flow from her face in a kind of dark brightness, if I may use such an expression; her eyes are soft and deep. I have seen no other eyes like my mother Marie's. She taps the violin with the bow; then she taps me under the chin.

"Dis 'Bon jour!' petit Jacques!" and I say "Bo' zour!" as well as I can, and duck my head, for a bow is expected of me. No bow, no music, and I am quivering with eagerness for the music. Now she[9] draws the bow across the strings, softly, smoothly,—ah, my dear, you have heard only me play, all your life; if you could have heard my mother! As I see her and hear her, this day of my babyhood, the song she plays is the little French song that you love. If you could have heard her sing!

| "A la claire fontaine M'en allant promener, Jai trouvé l'eau si belle Que je m'y suis baigné. Il y a longtemps que je t'aime, Jamais je ne t'oublierai!" | As I went walking, walking, I found its waves so lovely, Beside the fountain fair, I stayed to bathe me there. 'Tis long and long I have loved thee, I'll ne'er forget thee more. |

As my mother sings the last words, she bends and kisses the violin, which was always a living personage to her. Her head moves like a bird's head, quickly and softly. I see her face all brightness, as I have told you; then suddenly a shadow falls on it. My back is towards the door, but she stands facing it. I feel myself snatched up by hands like quivering steel; I am set down—not roughly—on the floor. My father turns a terrible face on my mother.

"Mary!" he cried. "He was on the Bible! You—you set the child on the Holy Bible!"

I am too frightened to cry out or move, but my mother Marie lays down her violin in its box—as tenderly as she would lay me in my cradle—and goes to my father, and puts her arm round his neck, and speaks to him low and gently, stroking back his[10] short, fair hair. Presently the frightful look goes out of his face; it softens into love and sadness; they go hand-in-hand into the inner room, and I hear their voices together speaking gravely, slowly. I do not know that they are praying,—I have known it since. I watch the flies on the window, and wish my father had not come.

That, Melody, is the first thing I remember. It must have been after that, that my father made me a little chair, and my mother made a gay cushion for it, with scarlet frills, and I sat always in that. Our kitchen was a sunny room, full of bright things; Mother Marie kept everything shining. The floor was painted yellow, and the rugs were scarlet and blue; she dyed the cloth herself, and made them beautifully. There was always a fire—or so it seems now—in the great black gulf of a fireplace, and the crane hung over it, with pots and kettles. The firelight was thrown back from bright pewter and glass and copper all about the walls; I have never seen so gay a room. And always flowers in the window, and always a yellow cat on a red cushion. No canary bird; my mother Marie never would have a bird. "No prisoners!" she would say. Once a neighbour brought her a wounded sparrow; she nursed and tended it till spring, then set it loose and watched it fly away.

This neighbour was a boy, some years older than myself; he is one of the people I remember best. Petie we called him; Peter Brand; he died long ago.[11] He had been a comfort to my mother Marie, in days of sadness,—before my birth, for she was never sad after I came,—and she loved him, and he clung to her. He was a round-faced boy, with hair almost white; awkward and shy, but very good to me.

As I grew older my mother taught me many French songs and games, and Petie often made a third with us. He made strange work of the French speech; to me it came like running water, but to Petie it was like pouring wine from a corked bottle. Mother Marie could not understand this, and tried always to teach him. I can hear her cry out, "Not thus, Petie! not! you break me the ears! Listen only!

And Petie would drone out, all on one note (for the poor boy had no music either),

I speak of cakes. There was no one in the village who could cook like my mother; every one acknowledged that. Whatever she put her hand to was done to perfection. And the prettiness of it all! A flower, a green leaf, a bunch of parsley,—there was some delicate, pretty touch to everything she did. I must have been still small when I began to notice how she arranged the dishes on our table. These matters can mean but little to you, my dear child; but the eyes of your mind are so quick, I know it is one of your delights to fancy the colours and lights that you cannot see. Some bright-coloured food, then,—fried fish, it might be, which should be of a golden brown shade,—would be always on a dark blue platter, while a dark dish, say beefsteak, would be on the creamy yellow crockery that had belonged to my father's mother; and with it a wreath of parsley or carrot, setting off the yellow still more. And always, winter and summer, some flower, if only a single geranium-bloom, on the table. So that our table was always like a festival. I think this troubled my father, when his dark moods were on him. He thought it a snare of the flesh. Sometimes, if the meal were specially dainty, he would eat nothing but dry bread, and this grieved Mother Marie almost more than anything else. I remember one day,—it was my birthday, and I must have been quite a big boy by that time,—Mother Marie had made a pretty[13] rose-feast for me. The table was strewn with rose-leaves, and there was a garland of roses round my plate, and they stood everywhere, in cups and bowls. There was a round cake, too, with rose-coloured frosting; I thought the angels might have such feasts on their birthdays, but was sure no one else could.

But when my father came in,—I can see now his look of pain and terror.

"You are tempting the Lord, Mary!" he cried. "You are teaching our child to love the lust of the flesh and the pride of the eye. It is sin, it is sin, my wife!"

I trembled, for I feared he would throw my beautiful cake into the fire, as I had once seen him throw a pretty salad. But my mother Marie took his arm. The door stood open, and the warm June was shining through. She led him to the doorway, and pointed to the sky.

"Look, mon ami!" she said, in her clear, soft voice. "See the day of gold that the good God has made for our little Jacques! He fills the garden wiz roses,—I bring His roses in ze house. It is that He love ze roses, and ze little child, and thee and me, my poor Jacques; for He make us all, is it not?"

And presently, with her soft hand on his arm, the pain went from my poor father, and he came in and sat down with us, and even patted my head and tasted the cake. I recall many such scenes as this, my dear child. And perhaps I should say that my mind was, and has always remained, with my mother[14] on such matters. If God gives food for the use of His creatures, it is to His honour and glory to serve it handsomely, so far as may be; and I see little religion in a slovenly piece of meat, or a shapeless hunch of butter on a dingy plate.

My mother having this gift of grace, it was not strange that the neighbours often called on her for some service of making beautiful. At a wedding or a merrymaking of any kind she would be sent for, and the neighbours, who were plain people, thought her gift more than natural. People still speak of her in all that part of the country, though she has been dead sixty odd years, little Mother Marie. She would have liked to make the meeting-house beautiful each Sabbath with flowers, but this my father could not hear of, and she never urged it after the first time. At a funeral, too, she must arrange the white blossoms, and lay the pale hands together. Abby Rock has told me many stories of the comfort she brought to sorrowing homes, with her sweet, light, quiet ways. Abby loved her as her own child.

As I grew older, my mother taught me the violin. I learned eagerly. I need not say much about that, Melody; my best playing has been for you, and you know all I could tell you; I learned, and it became the breath of life to me. My lessons were in the morning always, so that my father might not hear the sound; but this was not because he did not love the violin. Far otherwise! In the long winter evenings my mother Marie would play for him, after I[15] was tucked up in my trundle-bed; music of religious quality, which stirred his deep, silent nature strongly. She had learned all the psalm-tunes that he loved, stern old Huguenot melodies, many of them, that had come over from France with his ancestor, and been sung down through the generations since. And with these she played soft, tender airs,—I never knew what they were, but they could wile the heart out of one's breast. I sometimes would lift my head from my pillow, and look through the open door at the warm, light kitchen beyond (for my mother Marie could not bear to shut me into the cold, dark little bedroom; my door stood open all night, and if I woke in the night, the coals would always wink me a friendly greeting, and I could hear the cat purring on her cushion). I would look, I say, through the open door. There would my mother stand, with the light, swaying way she had, like a flower or a young white birch in the wind; her cheek resting on the violin, her eyelids dropped, as they mostly were when she played, and the long lashes black against her soft, clear paleness. And my father Jacques sitting by the fire, his chin in his hand, still as a carved image, looking at her with his heart in his eyes. That is the way I think of them oftenest, Melody, my dear, as I look back to the days long ago; this is the way I mostly see my father and mother, Jacques and Marie De Arthenay, a faithful husband and wife.

"They are ducks!" she said. (She called it "docks," Melody; you cannot think how soft her speech was.) "Poor leetle docks, that go flap, flap; not yet zey have learned to swim, no! But here now, see a bird of ze water, a sea-bird what you call." She turned her wrist and sent the flat pebble flying; it skimmed along like a live thing, flipping the little crests of the ripples, going miles, it seemed to Petie and me, till at length we lost sight of it altogether.[17]

"Where did it go?" I asked. "I didn't hear it splash."

"It went—to France!" said Mother Marie. "It make a voyage, it goes, goes,—at last it arrives. 'Voilà la France!' it say. 'That I go ashore, to ask of things for Marie, and for petit Jacques, and for Petie too, good Petie, who bring the apples.'"

There were red apples in a basket, and I can see now the bright whiteness of her teeth as she set them into one.

"What will the stone see?" I asked again; for I loved to make my mother tell me of the things she remembered in France, the country she always loved. She loved to tell, too; and a dreamy look would come into her eyes at such times, as if she did not see us near at hand, but only things far off and dim. We listened, Petie and I, as if for a fairy tale.

"He come, zat leetle—non! that lit-tel stone." (Mother Marie could often pronounce our English "th" quite well; it was only when she forgot that she slipped back to the soft "z" which I liked much better.) "He come to the shore! It is not as this shore, no! White is the sand, the rocks black, black. All about are nets, very great, and boats. The men are great and brown; and their beards—Holy Cric! their beards are a bush for owls; and striped their shirt, jersey, what you call, and blue trousers. Zey come in from sea, their sails are brown and red; the boats are full wiz fish, that shine like silver; they are the herring, petit Jacques, it is of those that we live a[18] great deal. Down zen come ze women to ze shore and zey—they—are dressed beautiful, ah! so beautiful! A red petticoat,—sometimes a blue, but I love best the red, striped wiz white, and over this the dress turned up, à la blanchisseuse. A handkerchief round their neck, and gold earrings,—ah! long ones, to touch their neck; and gold beads, most beautiful! and then the cap! P'tit Jacques, thou hast not seen caps, because here they have not the understanding. But! white, like snow in ze sun; the muslin clear, you understand, and stiff that it cracks,—ah! of a beauty! and standing out like wings here, and here—you do not listen! you make not attention, bad children that you are! Go! I tell you no more!"

It was true, Melody, my dear, that Petie and I did not care so much about the descriptions of dress as if we had been little girls; my mother was never weary of telling about the caps and earrings; I think she often longed for them, poor little Mother Marie! But now Petie and I clung about her, and begged her to go on, and she never could keep her vexation for two minutes.

"Tell how they go up the street!" said Petie.

"Play we went, too!" cried I. "Play the stone was a boat, Mère Marie." (I said it as one word, Melody; it makes a pretty name, "Mère-Marie," when the pronunciation is good. To hear our people say "M'ree" or "Marry," breaks the heart, as my mother used to say.)[19]

She nodded, pleased enough to play,—for she was a child, as I have told you, in many, many ways, though with a woman's heart and understanding,—and clapped our hands softly together, as she held them in hers.

"We, then, yes! we three, Mère-Marie, p'tit Jacques, and Petie, we go up from the beach, up the street that goes tic tac, zic zac, here and there, up the hill; very steep in zose parts. We come to one place, it is steps—"

"Steps in the street?"

"Steps that make the street, but yes! and on them (white steps, clean! ah! of a cleanness!), in the sun, sit the old women, and spin, and sing, and tell stories. Ah! the fine steps. They, too, have caps, but they are brown in the faces, and striped—"

"Striped, Mère-Marie? painted, do you mean?"

"She said the steps had caps!" whispered Petie, incredulous, but too eager for the story to interrupt the teller.

"Painted? wat you mean of foolishness, p'tit Jacques? Ah! I was wrong! not striped; wreenkled, you say? all up togezzer like a brown apple when he is dry up,—like zis way!" and Mother Marie drew her pretty face all together in a knot, and looked so comical that we went into fits of laughter.

"So! zey sit, ze old women, and talk, talk, wiz ze heads together; but one sit alone, away from those others, and she sing. Her voice go up, thin, thin, like a little cold wind in ze boat-ropes.[20]

"I make learn you that song, petit Jacques, one time! So we come,—now, mes enfants, we come! and all the old women point the nose, and say, 'Who is it comes there?' But that one old—but Mère Jeanne, she cry out loud, loud. 'Marie! petite Marie, where hast thou been so long, so long?' She opens the arms—I fall into zem, on my knees; I cry—but hush, p'tit Jacques! I cry now only in ze story, only—to—to show thee how it would be! I say, 'It is me, Marie, Mère Jeanne! I come to show thee my little son, to take thy blessing. And my little friend, too!'" She turned to pat Petie's head; she would not let the motherless boy feel left out, even from a world in which he had no part.

"My good friend Petie, whose mother is with the saints. Then Mère Jeanne, she take all our hands, after she has her weep; she say 'Come!' and we go up ze street, up, up, till we come to Mère Jeanne's house."

"Tell about the house!" I cried.

"Holy Cric! what a house!" cried Mère-Marie, clapping her hands together. "It is stone, painted white, clean, like new cheese; the roof beautiful, straw,[21] warm, thick,—ah! what roofs! I have tried to teach thy father to make them, but no! Inside, it is dark and warm, and full wiz good smells. Now it is the pot-au-feu, but not every day zis, for Mère Jeanne is poor; but always somesing, fish to fry, or pancakes, or apples. But zis time, Mère Jeanne make me a fête; she say, 'It is the Fête Marie!'

"She make the fire bright, bright; and she bring big chestnuts, two handfuls of zem, and set zem on ze shovel to roast; and zen she put ze greedle, and she mixed ze batter in a great bowl—it is yellow, that bowl, and the spoon, it is horn. She show it to me, she say, 'Wat leetle child was eat wiz this spoon, Marie? hein?' and I—I kiss the spoon; I say, ''Tite Marie, Mère Jeanne! 'Tite Marie qui t'aime!'[2] It is the first words I could say of my life, mes enfants!

"Zen she laugh, and nod her head, and she stir, stir, stir till ze bobbles come—"

"The way they do when you make griddle-cakes, Mère-Marie?"

"Ah! no! much, much, thousand time better, Mère Jeanne make zem! She toss them—so! wiz ze spoon, and they shine like gold, and when they come down—hop!—they say 'Sssssssssss!' that they like to fry for Mère Jeanne, and for Marie, and p'tit Jacques, and good Petie. Then I bring out the black table, and I know where the bread live, and the cheese, and while the cakes fry, I go to milk the cow—ah! the pearl of cows, children, white like her own cream, fat[22] like a boiled chestnut, good like an angel! She has not forgotten Marie, she rub her nose in my heart, she sing to me. I take her wiz both my arms, I weep—ah! but it is joy, p'tit Jacques! it is wiz joy I weep! Zen, again in ze house, and round ze table, we all sit, and we eat, and eat, that we can eat no more. And Mère Jeanne say:

"'Tell me of thy home, Marie!' and I tell all, all; of thy father Jacques, how he good, and great, and handsome as Saint Michael; and how my house is fine, fine, and how Abiroc is good. And Mère Jeanne, she make the great eyes; she cry, 'Ah! the good fortune! Ah, Marie, that thou art fortunate, that thou art happy!'

"Then she tell thee, p'tit Jacques, how I was little, little, in a blue frock, wiz the cap tie under my chin; and how I dance and sing in the street, and how Madame la Comtesse see me, and take me to ze castle, and make teach me the violin, and give me Madame for my friend. I have told thee all, many, many times. Then she tell, Mère Jeanne,—oh! she is good, good, and all ze time she fill thee wiz chestnuts that I cry out lest thou die,—she tell how one day she come home from market, and I am gone. No Marie! She look, she run here and there, she cry, ''Tite Marie, where art thou?' No Marie come. She run to the neighbours, she search, she tear her cap; they tell her, 'Demand of thy son's wife! The strange ship sailed this morning; we heard child cry; what do we know?'[23]

"For the wife of Mère Jeanne's Jeannot, she was a devil, as I have told thee, a devil with both the eyes evil; and none dare say what she had done, for fear of their children and their cows to die. And then, Mère Jeanne she tell how she run to Jeannot's house,—she fear nossing, Mère Jeanne! the good God protect her always. She cry, 'Where is Marie? where is my child?' And Jeannot's Manon, she laugh, she say, 'Cross the sea after her, old witch! Who keeps thee?' Then—see, p'tit Jacques! see, Petie! I have not seen this wiz my eyes, no! but in my heart I have seen, I know! Then Mère Jeanne run at that woman, that devil; and she pull off her cap and tread it wiz her foot; and she pull out her hair,—never she had much, but since this day none!—and she scratch her face and tear the clothes—ah! Mère Jeanne is mild like a cherub till she is angry, but then— And that devil scream, scream, but no one come, no one care; they are all glad, they laugh to hear. Till Jeannot run in, and catch his mother and hold her hands, and take her home to her house. She tell me all this, Mère Jeanne, and it is true, and I know it in my heart. But now she is dead, that witch, and the great devil has her, and that is well." (I think my father would have lost his wits, Melody, if he had heard the way my mother talked to me sometimes; but it was a child's talk, my dear, and there was no harm. A child who had been brought up among ignorant peasants; how should she know better, poor little Mother Marie?)[24]

"But now, see, mes enfants! We must come back across the sea, for ze sun, he begin to go away down. So I tell zis, and Mère Jeanne she cry, she take us wiz her arms, she cannot let us go. But I take Madame on my arm, I go out in ze street, I begin to play wiz my hand. Then all come, all run, all cry, 'Marie! Marie is here wiz her violon!' And I play, play and sing, and the little children dance, dance, and p'tit Jacques and Petie take them the hands and dance wiz—

"Adieu, adieu, Mère Jeanne! adieu, la France! but you, mes enfants; why do you cry?"

My father wished me to help him in the farm work, but I had no turn for that. I was growing up tall and weedy, and most like my strength went into that. However it was, there was little of it for farming, and less liking. Father Jacques made up his mind that I was no good for anything, but Abby Rock stood up for me.

"The boy is not strong enough for farming, Jacques!" she said. "He's near as tall as you, now, and not fifteen yet. Put him to learn a trade, and he'll be a credit to you."

So I was put to learn shoemaking, and a good trade it has been to me all my life. The shoemaker was a kind old man, who had known me from a baby, and he contrived to make my work easy for me,—seeing I took kindly to it,—and often let me have the afternoon to myself. My lungs were weak, or Abby thought they were, and the doctor had told her I must not sit too long over my bench, but must be out in the air as much as might be, though not at hard labour. Then,—those afternoons, I am saying,—I would be off like a flash with my fiddle,—off to the yellow sand beach where the round pebbles lay. I could never let my poor father hear me play; it was a knife in his heart even to see the Lady; and these hours on the beach were my comfort, and kept[27] the spirit alive in me. Looking out to sea, I could still feel my mother Marie beside me, still hear her voice singing, so gay, so sad,—singing all ways, as the wind blows. She had no voice like yours, Melody, my dear, but it was small and sweet as a bird's; sweet as a bird's! It was there, on the yellow sand beach, that I first met Father L'Homme-Dieu, the priest.

I have told you a great deal about this good man, Melody. He came of old French stock, like ourselves,—like most of the people in our village; only his people had always been Catholics. His village, where he had a little wooden church, was ten or twelve miles from ours, but he was the only priest for twenty miles round, and he rode or walked long distances, visiting the scattered families that belonged to his following. He chanced to come to the beach one day when I was there, and stayed to hear me play. I never knew he was there till I turned to go home; but then he spoke to me, and asked about my music and my home, and talked so kindly and wisely that my heart went out to him that very hour. He took to me, too; he was a lonely man, and there was none in his own neighbourhood that he cared to make his friend; and seldom a week passed that he did not find his way to the beach, for an hour of music and talk. Talk! How we did talk! There was always a book in his pocket, too, and he would read some fine passage aloud, and then we would discuss it, and turn it over and over, and let it draw our own thoughts like[28] a magnet. It was a rare chance for a country boy, Melody! Here was a scholar, and as fine a gentleman as ever I met, and the heart of a child and a wise man melted into one; and I like his own son for the kindness he gave me. Sometimes I went to his house, but not often, for I could not take so long a time away from my work. He lived in a little house like a bird's house, and the little brown woman who did for him was like a bird, and of all curious things, her name was Sparrow,—the widow Sparrow.

There was a little study, where he sat at a desk in the middle, and could pull down any book, almost, with no more than tilting his chair; and there was a little dining-room, and a closet with a window in it, where his bed stood. All these rooms were lined with books, most of them works of theology and religion, but plenty of others, too: poetry, and romances, and plays,—he was a great reader, and his books were all the friends he had, he used to say, till he found me. I should have been his son, he would say; and then lay his hand on my head and bid me be good, and say my prayers, and keep my heart true and clean. He never talked much to me of his own church (knowing my father by name and reputation), only made plain to me the love of God, and taught me to seek it through loving man.

I used to wonder how he came to be there, in the wilderness, as it must often have seemed to him, for he had travelled much, and was city-bred, his people having left the seacoast and settled inland in his[29] grandfather's time. One day, as I stood by his desk waiting for him, I saw a box that always lay there, set open; and in it was a portrait of a most beautiful lady in a rich dress. The portrait was in a gold frame set with red stones,—rubies, they may have been,—and was a rich jewel indeed. While I stood looking at it, Father L'Homme-Dieu came in; and at sight of the open box, and me looking at it, his face, that was like old ivory in its ordinary look, flushed dark red as the stones themselves. I was sorely vexed at myself, and frightened too, maybe; but the change passed from him, and he spoke in his own quiet voice. "That is the first half of my life, Jacques!" he said. "It is set in heart's blood, my son." And told me that this was his sweetheart who was drowned at sea, and it was after her death that he became a priest, and came to find some few sheep in the wilderness, near the spot where his fathers had lived. Then he bade me look well at the sweet face, and when my time should come to love, seek out one, if not so fair (as he thought there were none such), still one as true, and pure, and tender, and loving once, let it last till death; and so closed the box, and I never saw it open again.

All this time I never let my father know about Father L'Homme-Dieu. It would have seemed to him a terrible thing that his son should be friends with a priest of the Roman Church, which he held a thing accursed. I thought it no sin to keep his mind at peace, and clear of this thing, for a cloud was gathering[30] over him, my poor father. I told Abby, however, good Abby Rock; and though it shocked her at first, she was soon convinced that I brought home good instead of harm from my talks with Father L'Homme-Dieu. She it was who begged me not to tell my father, and she knew him better than any one else did, now that my mother Marie was gone. She told me, too, of the danger that hung over my poor father. The dark moods, since my mother's death, came over him more and more often; it seemed, when he was in one of them, that his mind was not itself. He never slighted his work,—that was like the breath he drew,—but when it was done, he would sit for hours brooding by the fireplace, looking at the little empty chair where my mother used to sit and sing at her sewing. And sitting so and brooding, now and again there would come over him as it were a blindness, and a forgetting of all about him, so that when he came out of it he would cry out, asking where he was, and what had been done to him. He would forget, too, that my mother was gone, and would call her, "Mary! Mary!" so that one's heart ached to hear him; and then Abby or I must make it clear to him again, and see the dumb suffering of him, like a creature that had not the power of speech, and knew nothing but pain and remembrance.

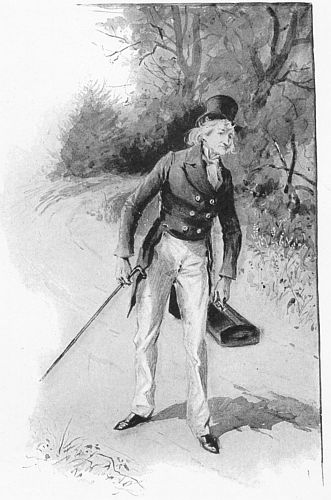

I might have been seventeen or eighteen at this time; I do not recall the precise year. I was doing well with my shoemaking, and when this trouble grew on my poor father I brought my bench into the[31] kitchen, so that I might have him always in sight. This was well enough for every day, but already I was beginning to be sent for here and there, among the neighbouring villages, to play the fiddle. The people of my father's kind were passing away, those who thought music a device of the devil, and believed that dancing feet were treading the road to hell. He was still a power in our own village; but in the country round about the young folks were learning the use of their feet, and none could hinder them, being the course of nature, since young lambs first skipped in the meadows. It was an old farmer, a good, jolly kind of man, who first gave me the name of "Rosin." He sent for me to play at his barn-raising, and a pretty sight it was; a fine new barn, Melody, all smelling sweet of fresh wood, and hung with lanterns, and a vast quantity of fruits and vegetables and late flowers set all about. Pretty, pretty! I have never seen a prettier barn-raising than that, and I have fiddled at a many since then. Well, this old gentleman calls to me across the floor, "Come here, young Rosin!" I remember his very words. "Come here, young Rosin! I can't get my tongue round your outlandish name, but Rosin'll do well enough for you." Well, it stuck to me, the name did, and I was never sorry, for I did not like to carry my father's name about overmuch, he misliking the dancing as he did. The young folks caught up an old song, and tagged that name on too, and called me Rosin the Bow. So it was first, Melody; but there are two songs, as you[32] know, my dear, to the one tune (or one tune is all I know, and fits both sets of words), and the second song spells the word "Beau," and so some merry girls in a house where I often went to play, they vowed I should be Rosin the Beau. I suppose I may have been rather a good-looking lad, from what they used to say; and to make a long story short, it was by that name that I came to be known through the country, and shall be known till I die. An old beau enough now, my little girl; eighty years old your Rosin will be, if he lives till next September. I took to playing the air whenever I entered a room; it made a little effect, a little stir,—I was young and foolish, and it took little to please me in those days. But I have always thought, and think still, that a man, as well as a woman, should make the best of the mortal part of him; and I do not know why we should not be thankful for a well-looking body as for a well-ordered mind. I cannot abide to see a man shamble or slouch, or throw his arms and legs about as if they were timber logs. Many is the time I have said to my scholars, when I was teaching dancing-school,—great lumbering fellows, hulking through a quadrille as if they were pacing a raft in log-running,—"Don't insult your Creator by making a scarecrow of the body He has seen fit to give you. With reverence, He might have given it to one of better understanding; but since you have it, for piety's sake hold up your head, square your shoulders, and put your feet in the first position!"[33]

But I wander from the thread of my story, as old folks will do. After all, it is only a small story, of a small life; not every man is born to be great, my dear. Yet, while I sat on my shoemaker's bench, stitching away, I thought of greatness, as I suppose most boys do. I thought of a scholar's life, like that of Father L'Homme-Dieu before his sorrow came to him; a life spent in cities, among libraries and learned, brilliant people, men and women. I thought of a musician's life, and dreamed of the concerts and operas that I had never heard. The poet Wordsworth, my dear, has written immortal words about the dreams of a boy, and my dreams were fair enough. It seemed as if all the world outside were clouded in a golden glory, if I may put it so, and as if I had only to run forth and put aside this shining veil, to find myself famous, and happy, and blessed. And when I came down from the clouds, and saw my little black bench, and the tools and scraps of leather, and my poor father sitting brooding over the fire, my heart would sink down within me, and the longing would come strong upon me to throw down hammer and last, and run away, out into that great world that was calling for me. And so the days went by, and the months, and the years.

As I walked across the brown fields, where the green was beginning to prick in little points here and there, I began to feel the life strong in me once more. The dull cloud of depression seemed to drop away, and instead of seeing always that sad, set face of my poor father's, I could look up and around, and whistle to the squirrels, and note the woodpecker running round[35] the tree near me. It has remained a mystery to me all my life, Melody, that this bird's brains are not constantly addled in his head, from the violence of his rapping. When I was a little boy, I tried, I remember, to nod my head as fast as his went nodding: with the effect that I grew dizzy and sick, and Mother Marie thought I was going to die, and said the White Paternoster over me five times.

I looked about me, I say, and felt my spirit waking with the waking of the year. Yet, though I was glad to feel alive and young once more, I never thought I was going to anything new or wonderful. The wise, kind friend would be there; we should talk, and I should come away refreshed and strengthened, in peace and courage; I thought of nothing more. But when the widow Sparrow opened the door to me, I heard voices from the room within; a strange voice of a man, and the priest's answering. I stopped short on the threshold.

"The Father is busy!" I said. "I will call again, when he is alone."

"Now don't you!" said Mrs. Sparrow, who was always fond of me, and thought it a terrible walk for me to take, so young, and with the "growing weakness" not out of me. "Don't ye go a step, Jacques! I expect you can come in just as well as not. There is a gentleman here, but he's so pleasant, I should wish to have you see him, if I was the Father."

I was hesitating, all the shyness of a country-bred boy coming over me; for I had a quick ear, and[36] this strange voice was not like the voices I was used to hearing; it was like Father L'Homme-Dieu's, fine and high-bred. But the next instant Father L'Homme-Dieu had stepped to the door of the study, and saw me.

"Come in, Jacques!" he cried. His eyes were bright, and his air gay, as I had never seen it. "Come in, my son! I have a friend here, and you are the very person I want him to meet." I stepped over the threshold awkwardly enough, and stood before the stranger. He was a young man, a few years older than myself; tall and slender,—we might have been twins as far as height and build went, but there the resemblance ceased. He was fair, with such delicate colouring that he might have looked womanish but for the dark fiery blue of his eyes, and his little curled moustache. He looked the way you fancy a prince looking, Melody, when Auntie Joy tells you a fairy story, though he was simply dressed enough.

"Marquis," said Father L'Homme-Dieu, with a shade of ceremony that I had never heard before in his tone, "let me present to you M. Jacques D'Arthenay, my friend! Jacques, this is the Marquis de Ste. Valerie."

He gave my name the French pronunciation. It was kindly meant; at my present age, I think it was perhaps rightly done; but then, it filled me with a kind of rage. The angry blood of a false pride, a false humility, surged to my brain and sang in my ears; and as the young man stepped forward with[37] outstretched hand, crying, "A compatriot. Welcome, monsieur!" I drew back, stammering with anger. "My name is Jacques De Arthenay!"[3] I said. "I am an American, a shoemaker, and the son of a farmer."

There was a moment of silence, in which I seemed to live a year. I was conscious of everything, the well-bred surprise of the young nobleman, the half-amused vexation of the priest, my own clumsy, boyish rage and confusion. In reality it was only a few seconds before I felt my friend's hand on my shoulder, with its kind, fatherly touch.

"Sit down, my child!" he said. "Does it matter greatly how a name is pronounced? It is the same name, and I pronounced it thus, not without a reason. Sit down, and have peace!"

There was authority as well as kindness in his voice. I sat down, still trembling and blushing. Father L'Homme-Dieu went on quietly, as if nothing had happened.

"It was for the marquis's sake that I gave your name its former—and correct—pronunciation, my son Jacques. If I mistake not, he is of the same part of France from which your ancestors came. Huguenots of Blanque, am I not right, marquis?"

I was conscious that the stranger, whom I was inwardly accusing as a pretentious puppy, a slip of a dead and worthless tree, was looking at me intently; my eyes seemed drawn to his whether I would or no. So meeting those blue eyes, there passed as it were a[38] flash from them into mine, a flash that warmed and lightened, as a smile broke over his face.

"D'Arthenay!" he said, in a tone that seemed to search for some remembrance. "D'Arthenay, tenez foi! n'est-ce pas, monsieur?"

I started. The words were the motto of my father's house. They were engraved on the stone which marked the grave of my grandfather many times back, Jacques, Sieur D'Arthenay. Seeing my agitation, the marquis leaned forward eagerly. He was full of quick, light gestures, that somehow brought my mother back to me.

"But, we are neighbours!" he cried. "We must be friends, M. D'Arthenay. Your tower—it is a noble ruin—stands not a league from my château in Blanque. The Ste. Valeries and the D'Arthenays were always friends, since Adam was, and till the Grand Monarque separated them with his accursed Revocation. Monsieur, that I am enchanted at this rencounter! La bonne aventure, oh gai! n'est-ce pas, mon père?"

There was no resisting his eager gaiety. And when he quoted the nursery song that my mother used to sing, my stubborn resentment—at what? who can say?—broke and melted away, and I was smiling back into the bright, merry eyes. Once more he held out his hand, and this time I took it gladly. Father L'Homme-Dieu looked on in delight; it was a good moment.

After that the talk flowed freely. I found that[39] the young marquis, having come on a pleasure tour to the United States, had travelled thus far out of the general route to look up the graves of some of his mother's people, who had come out with Baron Castine, but had left him, as my ancestor had done, on account of his marriage with the Indian princess. They were the Belleforts of Blanque.

"Bellefort!" I cried. "That name is on several stones in our old burying-ground. The Belforts of our village are their descendants, Father L'Homme-Dieu."

"Not Ham?" cried the father, bursting into a great laugh. "Not Ham Belfort, Jacques?"

I laughed back, nodding. "Just Ham, father!"

I never saw Father L'Homme-Dieu so amused. He struck his hands together, and leaned back in his chair, repeating over and over, "Ham Belfort! Cousin of the Marquis de Ste. Valerie! Ham Belfort! Is it possible?"

The young nobleman looked from one to the other of us curiously.

"But what?" he asked. "Ham! c'est-à-dire, jambon, n'est-ce pas?"

"It is also a Biblical name, marquis!" said Father L'Homme-Dieu. "I must ask who taught you your catechism!"

"True! true!" said the marquis, slightly confused. "Sem, Ham, et Japhet, perfectly! and—I have a cousin, it appears, named Jam—I should say,[40] Ham? Will you lead me to him, M. D'Arthenay, that I embrace him?"

"You shall see him!" I said. "I don't think Ham is used to being embraced, but I will leave that to you. I will take you to see him, and to see the graves in the burying-ground, whenever you say."

"But now, at the present time, this instant!" cried Ste. Valerie, springing from his chair. "Here is Father L'Homme-Dieu dying of me, in despair at his morning broken up, his studies destroyed by chatter. Take me with you, D'Arthenay, and show me all things; Ham, also his brothers, and Noë and the Ark, if they find themselves also here. Amazing country! astonishing people!"

So off we went together, he promising Mrs. Sparrow to return in time for dinner, and informing her that she was a sylphide, which caused her to say, "Go along!" in high delight. He had brought a letter to the priest, from an old friend, and was to stay at the house.

Back across the brown fields we went. I was no longer alone; the world was full of new light, new interest. I felt that it was good to be alive; and when my companion began to sing in very lightness of heart, I joined in, and sang with right good will.

The marquis—but why should I keep to the empty title, which I was never to use after that first hour? Nothing would do but that we should be friends on the instant, and for life,—Jacques and Yvon. "Thus it was two centuries ago," my companion declared, "thus shall it be now!" and I, in my dream of wonderment and delight, was only too glad to have it so.

We talked of a thousand things; or, to be precise, he talked, and I listened. What had I to say that could interest him? But he was full of the wonders of travel, the strangeness of the new world and the new people. Niagara had shaken him to the soul, he told me; on the wings of its thunder he had soared to the empyrean. How his fanciful turns of expression come back to me as I write of him! He was proud of his English, which was in general surprisingly good.

New York he did not like,—a savage in a Paris gown, with painted face; but on Boston he looked with the eyes of a lover. What dignity! what Puritan, what maiden grace of withdrawal! An American city, where one feels oneself not a figure of chess, but a human being; where no street resembles the one before it, and one can wander and be lost in delicious[42] windings! Ah! in Boston he could live, the life of a poet, of a scholar.

"And then,—what, my friend? I come, I leave those joys, I come away here, to—to the locality of jump-off, as you say,—and what do I find? First, a pearl, a saint; for nobleness, a prince, for holiness, an anchorite of Arabia,—Le Père L'Homme-Dieu! Next, the ancient friend of my house, who becomes on the instant mine also, the brother for whom I have yearned. With these, the graves of my venerable ancestors, heroes of constancy, who lived for war and died for faith; graves where I go even now, where I kneel to pay my duty of respect, to drop the filial tear!"

"Don't forget your living relations!" I said, with some malice. "Here is your cousin, coming to meet us."

"What—what is it?" he asked. "Is it a monster?"

"Oh, no!" I said. "It's only Ham Belfort. How are you, Ham?"

"Smart!" said Ham. "How be you? Hoish, Star! haw! Stand still there, will ye?"

The oxen came to a halt willingly enough, and man and beasts stood regarding us with calm, friendly eyes. Ham and his oxen looked so much alike, Melody (the oxen were white, I ought to have said), that I sometimes thought, if we dressed one of the beasts up and did away with his horns, people would hardly know which was which.

"Taking a load over to Cato?[44]"

Cato was the nearest town, my dear. It was there that the weekly boat touched, which was our one link with the world of cities and railways.

Ham nodded; he was not given to unnecessary speech.

"Is your wife better? I heard she was poorly."

"No, she ain't! I expect she'll turn up her toes now most any day."

This seemed awkward. I muttered some expressions of regret, and was about to move on, when my companion, who had been gazing speechless and motionless at the figure before him, caught my arm.

"Present me!" he whispered. "Holy Blue! this is my cousin, my own blood! Present me, Jacques!"

Now, I had never had occasion to make a formal introduction in my life, Melody. I had not yet begun to act as master of ceremonies at balls, only as fiddler and call-man; and it is the living truth that the only form of words I could bring to mind at the moment was, "Gents, balance to partners!" I almost said it aloud; but, fortunately, my wits came back, and I stammered out, sorely embarrassed:

"Ham, this is—a gentleman—who—who is staying with Father L'Homme-Dieu."

"That so? Pleased to meet you!" and Ham held out a hand like a shoulder of mutton, and engulfed the marquis's slender fingers.

"I am delighted to make the acquaintance of Mr. Belfort," said Ste. Valerie, with winning grace. "I[45] please myself to think that we are related by blood. My mother was a Bellefort of Blanque; it is the French form of your name, Mr. Belfort."

"I want to know!" said Ham. "Darned pleased to meet you!" He laboured for a moment, casting a glance of appeal at the oxen, who showed no disposition to assist him; then added, "You're slim-appearin' for a Belfort; they run consid'able large in these parts."

"Truly, yes!" cried the marquis, laughing delightedly. "You desire to show the world that there are still giants. What pleasure, what rapture, to go through the crowd of small persons, as myself, as D'Arthenay here, and exhibit the person of Samson, of Goliath!"

Ham eyed him gravely. "Meanin' shows?" he asked, after a pause of reflection. "No, we've never shew none, as I know of. We've been asked, father 'n' I, to allow guessin' on our weight at fairs and sech, but we jedged it warn't jest what we cared about doin'. Sim'lar with shows!"

This speech was rather beyond Ste. Valerie, and seeing him look puzzled, I struck in, "Mr. Ste. Valerie wants to see the old graves in the old burying-ground, Ham. I told him there were plenty of Belforts there, and spelling the name as he does, with two l's and an e in the middle."

"I want to know if he spells it that way!" said Ham, politely. "We jedged they didn't know much spellin', in them times along back, but I presume[46] there's different idees. Does your folks run slim as a rule?"

"Very slim, my cousin!" said Yvon. "Of my generation, there is none so great as myself."

"I want to know!" said Ham; and the grave compassion in his voice was almost too much for my composure. He seemed to fear that the subject might be a painful one, and changed it with a visible effort.

"Well, there's plenty in the old berr'in-ground spelt both ways. Likely it don't matter to 'em now."

He pondered again, evidently composing a speech; again he demanded help of the oxen, and went so far as to examine an ear of the nigh ox with anxious attention.

"'Pears as if what Belforts is above the sod ought to see something of ye!" he said at last. "My woman is sick, and liable to turn—I should say, liable to pass away most any time; but if she should get better, or—anything—I should be pleased to have ye come and stop a spell with us at the grist-mill. Any of your folks in the grist business?"

"Grisst?" Ste. Valerie looked helplessly at me. I explained briefly the nature of a grist-mill, and said truly that Ham's mill was one of the pleasantest places in the neighbourhood. Yvon was enchanted. He would come with the most lively pleasure, he assured Ham, so soon as Madame Belfort's health should be sufficiently rehabilitated. I remember, Melody, the pride with which he rolled out that long[47] word, and the delight with which he looked at me, to see if I noticed it.

"Meantime," he added, "I shall haste at the earliest moment to do myself the honour to call, to make inquiries for the health of madame, to present my respectful homages to monsieur your father. He will permit me to embrace him as a son?"

Fortunately Ham only heard the first part of this sentence; he responded heartily, begging the marquis to call at any hour. Then, being at the end of his talk, he shook hands once more with ponderous good will, and passed on, he and the oxen rolling along with equal steps.

Ste. Valerie was silent until Ham was out of earshot; then he broke out.

"Holy Blue! what a prodigy! You suffer this to burst upon me, Jacques, without notice, without preparation. My nerves are permanently shattered. You tell me, a man; I behold a tower, a mountain, Atlas crowned with clouds! Thousand thunders! what bulk! what sinews! and of my race! Amazing effect of—what? Climate? occupation? In France, this race shrinks, diminishes; a rapier, keen if you will, but slender like a thread; here, it swells, expands, towers aloft,—a club of Hercules. And with my father, who could sit in my pocket, and my grandfather, who could sit in his! Figure to yourself, Jacques, that I am called le grand Yvon!" He was silent for a moment, then broke out again. "But the mind. D'Arthenay! the brain; how is it with[48] that? Thought,—a lightning flash! is it not lost, wandering through a head large like that of an ox?"

I cannot remember in what words I answered him, Melody. I know I was troubled how to make it clear to him, and he so different from the other. I seemed to stand midway between the two, and to understand both. Half of me seemed to spring up in joy at the voice of the young foreigner; his lightness, his quickness, the very way he moved his hands, seemed a part of my own nature that I had not learned to use, and now saw reflected in another. I am not sure if I make myself clear, my child; it was a singular feeling. But when I would spring forward with him, and toss my head and wave my hands as he did,—as my mother Marie did,—there was something held me back; it was the other nature in me, slow and silent, and—no! not cold, but loath to show its warmth, if I may put it so. My father in me kept me silent many a time when I might have spoken foolishness. And it was this half, my father's half, that loved Ham Belfort, and saw the solid sweetness of nature that made that huge body a temple of good will, so to speak. He had the kind of goodness that gives peace and rest to those who lean against it. His mill was one of the places—but we shall come to that by and by!

Walking on as we talked, we soon came to the village, and I begged my new friend to come in and see my father and my home. We entered. My father was standing by the fire, facing the door, with one[49] hand on the tall mantel-shelf. He was in one of his waking dreams, and I was struck deeply, Melody, by the beauty, and, if I may use the word about a plain man, the majesty of his looks. My companion was struck, too, for he stopped short, and murmured something under his breath; I heard the word "Noblesse," and thought it not amiss. My father's eyes (they were extraordinarily bright and blue) were wide open, and looked through us and beyond us, yet saw nothing, or nothing that other eyes could see; the tender look was in them that meant the thought of my mother. But Abby came quietly round from the corner where she sat sewing, and laid her hand on his arm, and spoke clearly, yet not sharply, telling him to look and see, Jakey had brought a gentleman to see him. Then the vision passed, and my father looked and saw us, and came forward with a stately, beautiful way that he could use, and bade the stranger welcome. Ste. Valerie bowed low, as he might to a prince. Hearing that he was a Frenchman, my father seemed pleased. "My dear wife was a Frenchwoman!" he said. "She was a musician, sir; I wish you could have heard her play."

"He was himself also of French descent," Ste. Valerie reminded him, with another bow; and told of the ruined tower, and the old friendship between the two houses. But my father cared nothing for descent.

"Long ago, sir!" he said. "Long ago! I have nothing to do with the dead of two hundred years back. I am a plain farmer; my son has learned the[50] trade of shoemaking, though he also has some skill with the fiddle, I am told. Nothing compared to his mother, but still some skill."

Ste. Valerie looked from one of us to the other. "A farmer,—a shoemaker!" he said, slowly. "Strange country, this! And while your vieille noblesse make shoes and till the soil, who are these, monsieur, who live in some of the palaces that I have seen in your cities? In many, truly, persons of real nobility also, gentlemen, whether hunting of race or of Nature's own. But these others? I have seen them; large persons, both male and female, red as beef, their grossness illuminated with diamonds of royalty, their dwelling a magazine from the Rue de la Paix. These things are shocking to a European, M. D'Arthenay!" My father looked at him with something like reproof in his quiet gaze.

"I have never been in cities," he said. "I consider that a farmer's life may be used as well as another for the glory of God."

Then, with a wave of his hand, he seemed to put all this away from him, and with a livelier air asked the stranger to take supper with us. Abby had been laying the cloth quietly while we were talking, and my father would have asked her to sit down with us, but she slipped away while his face was turned in the other direction, and though he looked once or twice, he soon forgot. Poor Abby! I had seen her looking at him as he talked, and was struck by her intent expression, as if she would not lose a word he might[51] say. It seemed natural, though, that he should be her first thought; he had always been, since my mother died.

So presently we three sat about the little table, that was gay with flowers and pretty dishes. I saw Ste. Valerie's wondering glances; was it thus, he seemed to ask, that a farmer lived, who had no woman to care for him? My father saw, too, and was pleased as I had rarely seen him. He did not smile, but his face seemed to fill with light.

"My wife, sir," he said, "loved to see things bright and adorned. I try—my son and I try—to keep the table as she would like it. I formerly thought these matters sinful, but I have been brought to a clearer vision,—through affliction." (Strange human nature, Melody, my child! he was moved to say these words to a stranger, which he could not have said to me, his son!) "She had the French taste and lightness, my wife Mary. I should have been proud to have you see her, sir; the Lord was mindful of His own, and took her away from a world of sin and suffering."

The light died out; his eyes wandered for a moment, and then set, in a way I knew; and I began to talk fast of the first thing that came into my mind.

He was delighted with everything. He wanted to know about everything. He declared that he should write a book, when he returned to France, all about our village, which he called Paradise. It is a pretty place, or was as I remember it. He must see how bread was made, how wool was spun, how rugs were braided. Many's the time I have found him sitting in some kitchen, winding the great balls of rags neatly cut and stitched together, listening like a child while the woman told him of how many rugs she had made, and how many quilts she had pieced; and she more pleased than he, and thinking him one wonder and herself another.

He was in love with all the girls; so he said, and they had nothing to say against it. But yet there was no girl could carry a sore heart, for he treated them all alike. In this I have thought that he showed a sense and kindness beyond his years or his seeming giddiness; for some of them might well enough have had their heads turned by a gentleman, and one so handsome, and with a tongue that liked[54] better to say "Angel!" to a woman than anything more suited to the average of the sex. But no girl in the village could think herself for a moment the favoured maiden; for if one had the loveliest eyes in the world, the next had a cheek of roses and velvet, and the third walked like a goddess, and the fourth charmed his soul out of his body every time she opened her lips. And so it went on, till all understood it for play, and the pleasantest play they ever saw. But he vowed from the first that he would marry Abby Rock, and no other living woman. Abby always said yes, she would marry him the first Sunday that came in the middle of the week; and then she would try to make him eat more, though he took quite as much as was good for him, not being used to our hearty ways, especially in the mornings. Abby was as pleased with him as a child with a kitten, and it was pretty to see them together.

"Light of my life!" Yvon would cry. "You are exquisite this morning! Your eyes are like stars on the sea. Come, then, angelic Rock, Rocher des Anges, and waltz with your Ste. Valerie!" And he would take Abby by the waist, and try to waltz with her, till she reached for the broomstick. I have told you, Melody, that Abby was the homeliest woman the Lord ever made. Not that I ever noticed it, for the kindness in her face was so bright I never saw anything but that; but strangers would speak of it, and Yvon himself, before he heard her speak, made a little face, I remember, that only I could see, and[55] whispered, had I brought him to lodge with Medusa? Medusa, indeed! I think Abby's smile would soften any stone that had ever had a human heart beating in it, instead of the other way.

But the place in the village that Yvon loved best was Ham Belfort's grist-mill; and when he comes to my mind, in these days, when sadder visions are softened and partly dim to me, it is mostly there that I seem to see my friend.

It was, as I have said, one of the pleasantest places in the world. To begin with, the colour and softness of it all! The window-glass was powdered white, and the light came through white and dim, and lay about in long powdery shafts, and these were white, too, instead of yellow. So was the very dust white; or rather, it was good oatmeal and wheat flour that lay thick and crumbling on the rafters above, and the wheels and pulleys and other gear. As for Ham, the first time Yvon saw him in the mill, he cried out "Mont Blanc!" and would not call him anything else for some time. For Ham was whiter than all the rest, in his working-dress, cap and jacket and breeches, white to begin with, and powdered soft and furry, like his face and eyebrows, with the flying meal. Down-stairs there was plenty of noise; oats and corn and wheat pouring into the hoppers, and the great stones going round and round, and wheels creaking and buzzing, and belts droning overhead. Yvon could not talk at all here, and I not too much; only Ham's great voice and his father's (old Mr. Belfort[56] was Ham over again, gray under the powder, instead of pink and brown) could roar on quietly, if I may so express it, rising high above the rattle and clack of the machinery, and yet peaceful as the stream outside that turned the great wheels and set the whole thing flying. So, as he could not live long without talking, Yvon loved best the loft above, where the corn was stored, both in bags and unground, and where the big blowers were, and the old green fire-engine, and many other curious things. I had known them all my life, but they were strange to him, and he never tired, any more than if he had been a boy of ten. Sometimes I wondered if he could be twenty-two, as he said; sometimes when he would swing himself on to the slide, where the bags of meal and flour were loaded on to the wagons. Well, Melody, it was a thing to charm a boy's heart; it makes mine beat a little quicker to think of it, even now; perhaps I was not much wiser than my friend, after all. This was a slide some three feet wide, and say seven or eight feet long, sloping just enough to make it pleasant, and polished till it shone, from the bags that rubbed along it day after day, loading the wagons as they backed up under it. Nothing would do but we must slide down this, as if, I say, we were children of ten years old, coming down astride of the meal-sacks, and sending a plump of flour into the air as we struck the wagon. Father Belfort thought Yvon was touched in the brain; but he was all the more gentle on this account. Boys were not allowed on the slide, unless[57] it were a holiday, or some boy had had a hard time with sickness or what not; it was a treat rarely given, and the more prized for that. But Yvon and I might slide as much as we pleased. "Keep him cheerful, Jakey!" the dear old man would say. "Let him kibobble all he's a mind to! I had a brother once was looney, and we kep' him happy all his life long, jest lettin' him stay a child, as the Lord intended. Six foot eight he stood, and weighed four hundred pounds."

And when the boy was tired of playing we would sit down together, and call to Ham to come up and talk; for even better than sliding, Yvon loved to hear his cousin talk. You can take the picture into your mind, Melody, my dear. The light dim and white, as I have told you, and very soft, falling upon rows and rows of full sacks, ranged like soldiers; the great white miller sitting with his back against one of these, and his legs reaching anywhere,—one would not limit the distance; and running all about him, without fear, or often indeed marking him in any way, a multitude of little birds, sparrows they were, who spent most of their life here among the meal-sacks. Sometimes they hopped on his shoulder, or ran over his head, but they never minded his talking, and he sat still, not liking to disturb them. It was a pretty sight of extremes in bulk, and in nature too; for while Ham was afraid to move, for fear of troubling them, they would bustle up to him and cock their heads, and look him in the eye as if they said, "Come on, and show me which is the biggest!"[58]

There you see him, my dear; and opposite to him you might see a great mound or heap of corn that shone yellow as gold. "Le Mont d'Or," Yvon called it; and nothing would do but he must sit on this, lifted high above us, yet sliding down every now and then, and climbing up again, with the yellow grains slipping away under him, smooth and bright as pebbles on the shore. And for myself, I was now here and now there, as I found it more comfortable, being at home in every part of the friendly place.

How we talked! Ham was mostly a silent fellow; but he grew to love the lad so that the strings of his tongue were loosened as they had never been before. His woman, too (as we say in those parts, Melody; wife is the more genteel expression, but I never heard Ham use it. My father, on the other hand, never said anything else; a difference in the fineness of ear, my dear, I have always supposed),—his woman, I say, or wife, had not "turned up her toes," but recovered, and as he was a faithful and affectionate man, his heart was enlarged by this also. However it was, he talked more in those weeks, I suppose, than in the rest of his life put together. Bits of his talk, homely and yet wise, come back to me across the sixty years. One day, I remember, we talked of life, as young men love to talk. We said nothing that had not been said by young men since Abel's time, I do suppose, but it was all new to us; and indeed, my two companions had fresh ways of putting things that seemed to make them their own in a manner. Yvon[59] maintained that gaiety was the best that life had to give; that the butterfly being the type of the human soul, the nearer man could come to his prototype, the better for him and for all. Sorrow and suffering, he cried, were a blot on the scheme, a mistake, a concession to the devil; if all would but spread their wings and fly away from it, houp! it would no longer exist. "Et voilà!"

We laughed, but shook our heads. Ham meditated awhile, and then began in his strong, quiet voice, a little husky, which I always supposed was from his swallowing so much raw meal and flour.

"That's one way of lookin' at it, Eavan; I expect that's your French view, likely; looks different, you see, to folks livin' where there's cold, and sim'lar things, as butterflies couldn't find not to say comfortable. Way I look at it, it always seemed to me that grain come as near it as anything, go to compare things. Livin' in a grist-mill, I presume, I git into a grainy way of lookin' at the world. Now, take wheat! It comes up pooty enough, don't it, in the fields? Show me a field o' wheat, and I'll show you as handsome a thing as is made this side of Jordan. Wal, that might be a little child, we'll say; if there's a thing handsomer than a field o' wheat, it's a little child. But bimeby comes reapin' and all, and then the trouble begins. First, it's all in the rough, ain't it, chaff and all, mixed together; and has to go through the thresher? Well, maybe that's the lickin's a boy's father gives him. He don't like 'em,—I can[60] feel Father Belfort's lickin's yet,—but they git red of a sight o' chaff, nonsense, airs, and what not, for him. Then it comes here to the grist-mill. Well, I may be gittin' a little mixed, boys, but you can foller if you try, I expect. Say that's startin' out in life, leavin' home, or bindin' to a trade, or whatever. Well, it goes into the duster, and there it gets more chaff blowed off'n it. And from the duster it goes into the hopper, and down in betwixt the stones; and them stones grind, grind, grind, till you'd think the life was ground clear'n out of it. But 'tain't so; contrary! That's affliction; the upper and nether millstone—Scriptur! Maybe sickness, maybe losin' your folks, maybe business troubles,—whichever comes is the wust, and more than any mortal man ever had to bear before. Well, now, see! That stuff goes in there, grain; it comes out wheat flour! Then you take and wet it down and put your 'east in,—that's thought, I expect, or brains,—or might be a woman,—and you bake it in the oven,—call that—well, 'git-up-and-git' is all I can think of, but I should aim for a better word, talkin' to a foreigner."

"Purpose," I suggested.

"That's it! purpose! bake it in that oven, and you have a loaf of wheat bread, riz bread; and that's the best eatin' that's ben invented yet. That's food for the hungry,—which raw wheat ain't, except it's cattle. But now you hear me, boys! To git wheat bread, riz bread, you've got to have wheat to begin with. You've got to have good stuff to start with.[61] You can't make good riz bread out o' field corn. But take good stuff and grind it in the Lord's mill, and you've got the best this world can give. That's my philos'phy!"

He nodded his head to the last words, which fell slowly and weightily; and as he did so, the sparrow that had been perched on his head ran down his nose and fluttered in his face, seeming to ask how he dared make such a disturbance. "I beg your pardon, I'm sure!" said Ham. "I'd no notion I was interferin' with you. Why didn't you hit one of your size?"

I asked Yvon how I was to live, how my father and I should support ourselves in our restored castle, and whose money would pay for the restoration. He threw this aside, and said that money was base, and he refused to consider it. It had nothing to do with the feelings, less than nothing with true nobility. Should I then take my cobbler's bench, I asked him, and make shoes for him and his neighbours, while my father tilled the ground? But then, for the first and almost the last time, I saw my friend angry; he became like a naughty, sulky child, and would hardly speak to me for the rest of the day.

But he clung to his idea, none the less; and, to my great surprise, my father took it up after awhile. He thought well, he told me, of Yvon's plan; Yvon had talked it over with him. He, himself, was much stronger than he had been (this was true, Melody, or nothing would have induced me to leave him even for a week; Yvon had been like a cordial to him, and he had not had one of his seizures for weeks); and I could perfectly leave him under Abby's care. I had not been strong myself, a voyage might be a good thing for me; and no doubt, after seeing with my own eyes the matters this young lad talked of, I would be glad enough to come home and settle to my trade, and would have much to think over as I sat at my bench. It might be that a man was better for seeing something of the world; he had never felt that the Lord intended him to travel, having brought to his own door all that the world held of what was best (he[64] paused here, and said "Mary!" two or three times under his breath, a way he had when anything moved him), but it was not so with me, nor likely to be, and it might be a good thing for me to go. He had money laid by that would be mine, and I could take a portion of that, and have my holiday.

These are not his very words, Melody, but the sense of them. I was strangely surprised; and being young and eager, the thought came upon me for the first time that this thing was really possible; and with the thought came the longing, and a sense which I had only felt dimly before, and never let speak plain to me, as it were. I suppose every young man feels the desire to go somewhere else than the place where he has always abided. The world may be small and wretched, as some tell him, or great and golden, according to the speech of others; he believes neither one nor the other, he must see it with his own eyes. So this grew upon me, and I brooded over it, till my life was full of voices calling, and hands pointing across the sea, to the place which is Somewhere Else. I talked with Father L'Homme-Dieu, and he bade me go, and gave me his blessing; he had no doubt it was my pleasure, and might be my duty, in the way of making all that might be made of my life. I talked with Abby; she grew pale, and had but one word, "Your father!" Something in her tone spoke loud to my heart, and there came into my mind a thought that I spoke out without waiting for it to cool.

"Won't you marry my father, Abby?"[65]

Abby's hands fell in her lap, and she turned so white that I was frightened; still, I went on. "You love him better than any one else, except me." (She put her hand on her heart, I remember, Melody, and kept it there while I talked; she made no other sign.)

"And you can care for him ten times better than I could, you know that, Abby, dear; and—and—I know Mère-Marie would be pleased."

I looked in her face, and, young and thoughtless as I was, I saw that there which made me turn away and look out of the window. She did not speak at once; but presently said in her own voice, or only a little changed, "Don't speak like that, Jakey dear! You know I'll care for your father all I can, without that;" and so put me quietly aside, and talked about Yvon, and how good Father L'Homme-Dieu had been to me.

But I, being a lad that liked my own way when it did not seem a wrong one (and not only then, perhaps, my dear; not only then!), could not let my idea go so easily. It seemed to me a fine thing, and one that would bring happiness to one, at least; and I questioned whether the other would mind it much, being used to Abby all his life, and a manner of cousin to her, and she my mother's first friend when she came to the village, and her best friend always. I was very young, Melody, and I spoke to my father about it; that same day it was, while my mind was still warm. If I had waited over night, I might have seen more clear.[66]

"Father," said I; we were sitting in the kitchen after supper; it was a summer evening, soft and fair, but a little fire burned low on the hearth, and he sat near it, having grown chilly this last year.

"Father, would you think it possible to change your condition?"

He turned his eyes on me, with an asking look.

"Would you think it possible to marry Abby Rock?" I asked; and felt my heart sink, somehow, even with saying the words. My father hardly seemed to understand at first; he repeated, "Marry Abby Rock!" as if he saw no sense in the words; then it came to him, and I saw a great fire of anger grow in his eyes, till they were like flame in the dusk.

"I am a married man!" he said, slowly. "Are you a child, or lost to decency, that you speak of this to a married man?"

He paused, but I found nothing to say. He went on, his voice, that was even when he began, dropping deeper, and sinking as I never heard it.

"The Lord in His providence saw fit to take away my wife, your mother, before sickness, or age, or sorrow could strike her. I was left, to suffer some small part of what my sins merit, in the land of my sojourn. The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord. But because my wife Mary,—my wife Mary" (he lingered over the words, loving them so), "is a glorified spirit in another world, and I am a prisoner here, is she any less my wife, and I her faithful husband? You are[67] my son, and hers,—hers, Jakey; but if you ever say such words to me again, one house will not hold us both." He turned his head away, and I heard him murmuring under his breath, "Mary! Mary!" as I have said his way was; and I was silent and ashamed, fearing to speak lest I make matters worse; and so presently I slipped out and left him; and my fine plan came to naught, save to make two sad hearts sadder than they were.

But it was to be! Looking back, Melody, after fifty years, I am confident that it was the will of God, and was to be. In three weeks from that night, I was in France.

I pass over the wonder of the voyage; the sorrowful parting, too, that came before it, though I left all well, and my father to all appearances fully himself. I pass over these, straight to the night when Yvon and I arrived at his home in the south of France. We had been travelling several days since landing, and had stopped for two days in Paris. My head was still dizzy with the wonder and the brightness of it all. There was something homelike, too, in it. The very first people I met seemed to speak of my mother to me, as they flung out their hands and laughed and waved, so different from our ways at home. I was to see more of this, and to feel the two parts in me striving against each other; but it is early to speak of that.

The evening was warm and bright, as we came near Château Claire; that was the name of my friend's[68] home. A carriage had met us at the station, and as we drove along through a pretty country (though nothing to New England, I must always think), Yvon was deep in talk with the driver, who was an old servant, and full of news. I listened but little, being eager to see all my eyes could take in. Vines swung along the sides of the road, in a way that I always found extremely graceful, and wished we might have our grapes so at home. I was marvelling at the straw-roofed houses and the plots of land about them no bigger than Abby Rock's best table-cloth, when suddenly Yvon bade pull up, and struck me on the shoulder. "D'Arthenay, tenez foi!" he cried in my ear; and pointed across the road. I turned, and saw in the dusk a stone tower, square and bold, covered with ivy, the heavy growth of years. It was all dim in the twilight, but I marked the arched door, with carving on the stone work above it, and the great round window that stared like a blind eye. I felt a tugging at my heart, Melody; the place stood so lonely and forlorn, yet with a stateliness that seemed noble. I could not but think of my father, and that he stood now like his own tower, that he would never see.

"Shall we alight now?" asked Yvon. "Or will you rather come by daylight, Jacques, to see the place in beauty of sunshine?"

I chose the latter, knowing that his family would be looking for him; and no one waited for me in La Tour D'Arthenay, as it was called in the country.[69] Soon we were driving under a great gateway, and into a courtyard, and I saw the long front of a great stone house, with a light shining here and there.

"Welcome, Jacques!" cried Yvon, springing down as the great door opened; "welcome to Château Claire! Enter, then, my friend, as thy fathers entered in days of old!"

The light was bright that streamed from the doorway; I was dazzled, and stumbled a little as I went up the steps; the next moment I was standing in a wide hall, and a young lady was running forward to throw her arms round Yvon's neck.

He embraced her tenderly, kissing her on both cheeks in the French manner; then, still holding her hand, he turned to me, and presented me to his sister. "This is my friend," he said, "of whom I wrote you, Valerie; M. D'Arthenay, of La Tour D'Arthenay, Mademoiselle de Ste. Valerie!"