This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: An Explorer's Adventures in Tibet

Author: A. Henry Savage Landor

Release Date: October 24, 2008 [eBook #27021]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN EXPLORER'S ADVENTURES IN TIBET***

Minor punctuation errors have been corrected without notice. An obvious printer error has been corrected. It is indicated with a mouse-hover, and it is listed at the end. All other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

|

|

|

|

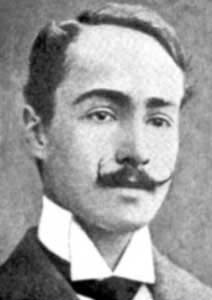

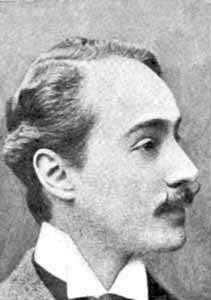

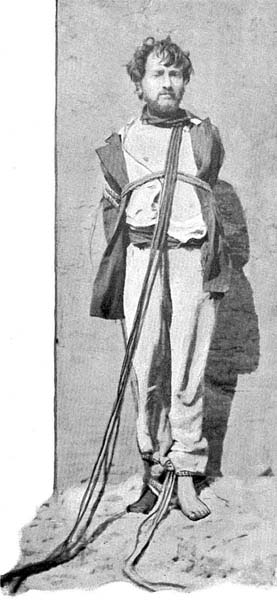

| THE AUTHOR, FEBRUARY, | THE AUTHOR, OCTOBER |

| 1897 | 1897 |

BY

A. HENRY SAVAGE LANDOR

AUTHOR OF

"In the Forbidden Land"

"The Gems of the East"

ETC. ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THE AUTHOR

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

MCMX

Copyright, 1910, by Harper & Brothers

All rights reserved

Published April, 1910.

Printed in the United States of America

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| Preface | vii | |

| I. | A Forbidden Country | 1 |

| II. | An Unknown Pass | 10 |

| III. | A Narrow Escape | 20 |

| IV. | Watched by Spies | 29 |

| V. | Warned Back by Soldiers | 37 |

| VI. | Encounter with a High Tibetan Official | 47 |

| VII. | An Exciting Night Journey | 58 |

| VIII. | Hungry Fugitives | 67 |

| IX. | An Attempt at Mutiny | 79 |

| X. | Among Enemies and Robbers | 90 |

| XI. | In Strange Company | 102 |

| XII. | Among the Lamas | 113 |

| XIII. | Life in the Monasteries | 126 |

| XIV. | Another Disaster | 136 |

| XV. | Followed by Tibetan Soldiers | 150 |

| XVI. | First White Man in the Sacred Province | 163 |

| XVII. | Disaster at the River | 176 |

| XVIII. | Captured | 191 |

| XIX. | Threats of Death | 203 |

| XX. | A Terrible Ride | 210 |

| XXI. | The Executioner | 220 |

| XXII. | A Charmed Life | 233 |

| XXIII. | Led to the Frontier | 245 |

| XXIV. | With Friends at Last | 257 |

| Appendix | 267 | |

| THE AUTHOR | Frontispiece | |

| INVOLUNTARY TOBOGGANING | Facing p. | 10 |

| AT NIGHT I LED MY MEN UP THE MOUNTAIN IN A FIERCE SNOW-STORM | " | 64 |

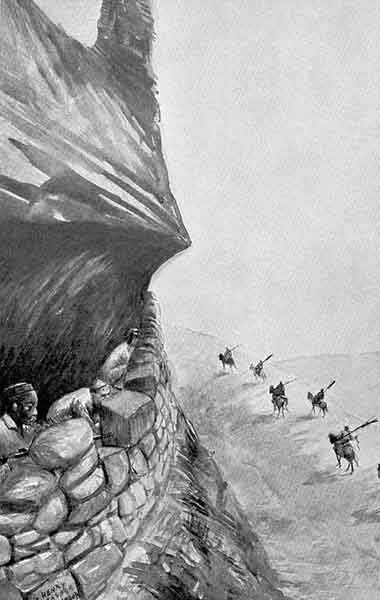

| BEHIND OUR BULWARKS | " | 76 |

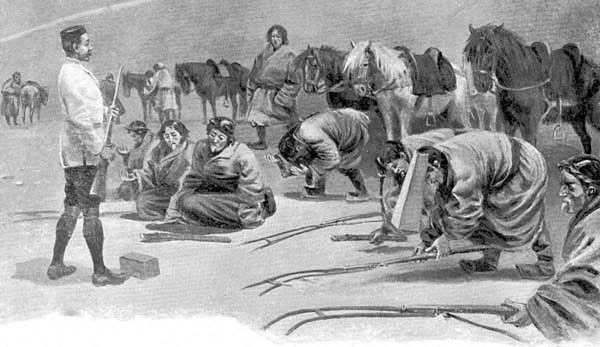

| THE BANDITS LAID DOWN THEIR ARMS | " | 102 |

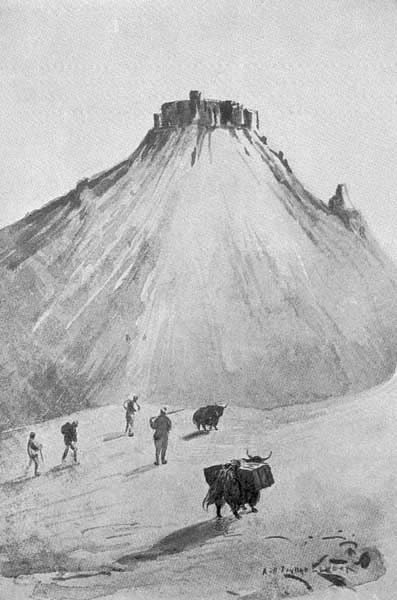

| A NATURAL CASTLE | " | 136 |

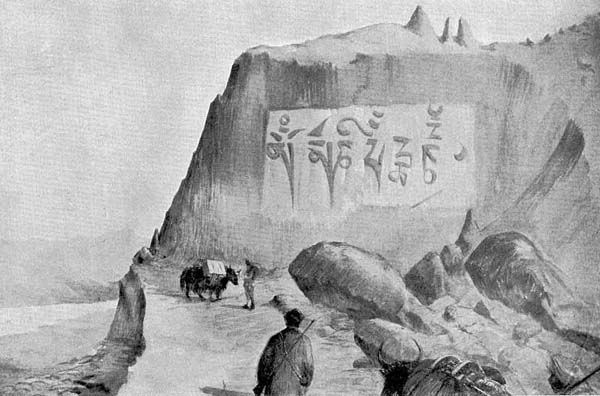

| CAMP WITH GIGANTIC INSCRIPTIONS | " | 142 |

| TORRENTIAL RAIN | " | 150 |

| TIBETAN WOMEN AND CHILDREN | " | 174 |

| PURCHASING PONIES | " | 192 |

| I WAS A PRISONER | " | 194 |

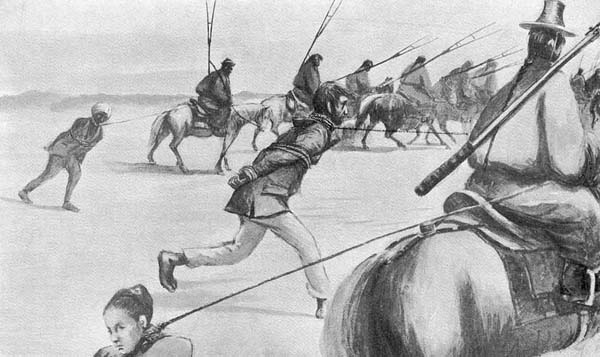

| DRAGGED INTO THE SETTLEMENT | " | 196 |

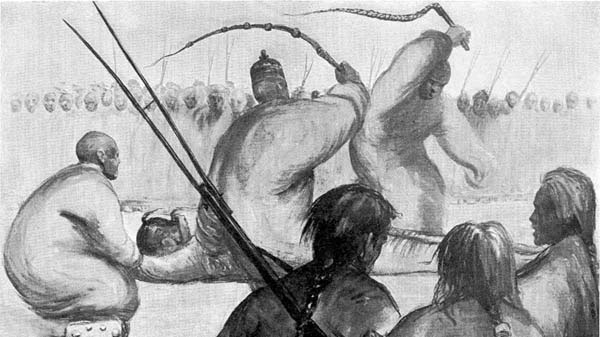

| CHANDEN SING BEING FLOGGED | " | 202 |

| THE RIDE ON A SPIKED SADDLE | " | 218 |

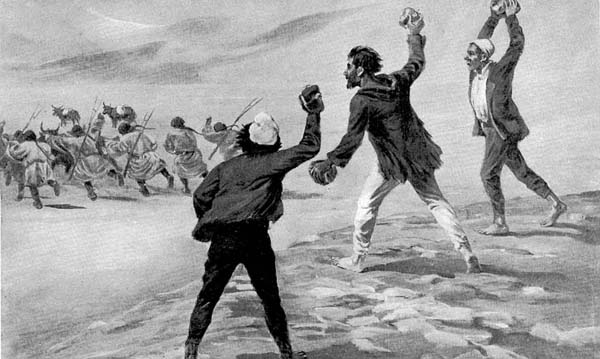

| WE ATTACKED OUR GUARD WITH STONES | " | 254 |

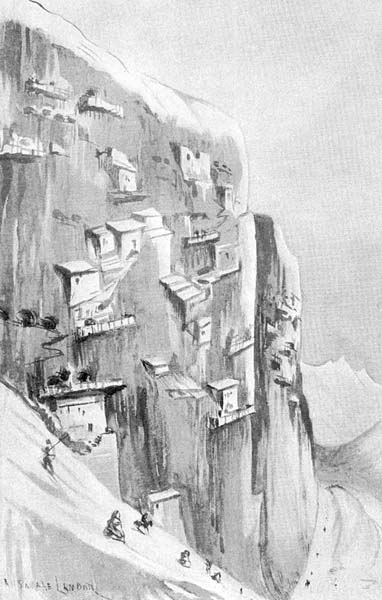

| CLIFF HABITATIONS | " | 262 |

This book deals chiefly with the author's adventures during a journey taken in Tibet in 1897, when that country, owing to religious fanaticism, was closed to strangers. For the scientific results of the expedition, for the detailed description of the customs, manners, etc., of the people, the larger work, entitled In the Forbidden Land (Harper & Brothers, publishers), by the same author, should be consulted.

During that journey of exploration the author made many important geographical discoveries, among which may be mentioned:

(a) The discovery of the two principal sources of the Great Brahmaputra River, one of the four largest rivers in the world.

(b) The ascertaining that a high range of mountains existed north of the Himahlyas, but with no such great elevations as the highest of the Himahlyan range.

(c) The settlement of the geographical controversy regarding the supposed connection between the Sacred (Mansarowar) and the Devil's (Rakastal) lakes.

(d) The discovery of the real sources of the Sutlej River.

In writing geographical names the author has given the names their true sounds as locally pronounced, and has made no exception even for the poetic word "Himahlya" (the abode of snow), which in English is usually misspelt and distorted into the meaningless Himalaya.

All bearings of the compass given in this book are magnetic. Temperature observations were registered with Fahrenheit thermometers.

A. H. S. L.

Tibet was a forbidden land. That is why I went there.

This strange country, cold and barren, lies on a high tableland in the heart of Asia. The average height of this desolate tableland—some 15,000 feet above sea-level—is higher than the highest mountains of Europe. People are right when they call it the "roof of the world." Nothing, or next to nothing, grows on that high plateau, except poor shrubs and grass in the lower valleys. The natives live on food imported from neighboring countries. They obtain this by giving in exchange wool, borax, iron, and gold.

High mountain ranges bound the Tibetan plateau on all sides. The highest is the Himahlya range to the south, the loftiest mountain range on earth. From the south it is only possible to enter Tibet with an expedition in summer, when the mountain passes are not entirely blocked by snow.

At the time of my visit the law of Tibet was that no stranger should be allowed to enter the country. The Tibetan frontier was closely guarded by soldiers.

A few expeditions had travelled in the northern part of Tibet, as the country was there practically uninhabited. They had met with no one to oppose their march save, perhaps, a few miserable nomads. No one, since Tibet became a forbidden country to strangers, had been able to penetrate in the Province of Lhassa—the only province of Tibet with a comparatively thick population. It was this province, the most forbidden of all that forbidden land, that I intended to explore and survey. I succeeded in my object, although I came very near paying with my life for my wish to be of use to science and my fellow-creatures.

With the best equipment that money could buy for scientific work, I started for the Tibetan frontier in 1897. From Bombay, in India, I travelled north to the end of the railway, at Kathgodam, and then by carts and horses to Naini Tal. At this little hill-station on the lower Himahlyas, in the north-west Province of India, I prepared my expedition, resolved to force my way in the Unknown Land.

Naini Tal is 6407 feet above the level of the sea. From this point all my loads had to be carried on the backs of coolies or porters. Therefore, each load must not exceed fifty pounds in weight. I packed instruments, negatives, and articles liable to get damaged in cases of my own manufacture, specially designed for rough usage. A set of four [3] such cases of well-seasoned deal wood, carefully joined and fitted, zinc-lined and soaked in a special preparation by which they were rendered water and air tight, could be made useful in many ways. Taken separately, they could be used as seats. Four placed in a row, answered the purpose of a bedstead. Three could be used as seat and table. The combination of four, used in a certain manner, made a punt, or boat, of quick, solid, and easy construction, with which an unfordable river could be crossed, or for taking soundings in the still waters of unexplored lakes. The cases could be used as tanks for photographic work. In case of emergency they might serve even as water-casks for carrying water in regions where it was not to be found. Each of these boxes, packed, was exactly a coolie load, or else in sets of two they could be slung over a pack-saddle by means of straps with rings.

My provisions had been specially prepared for me, and were suited to the severe climate and the high elevations I should find myself in. The preserved meats contained a vast amount of fat and carbonaceous, or heat-making food, as well as elements easily digestible and calculated to maintain one's strength in moments of unusual stress. I carried a .256 Mannlicher rifle, a Martini-Henry, and 1000 cartridges duly packed in a water-tight case. I also had a revolver with 500 cartridges, a number of hunting-knives, skinning implements, wire traps of several sizes for capturing small mammals, butterfly-nets, bottles for preserving reptiles in alcohol, insect-killing bottles (cyanide of potassium), a quantity of arsenical soap, bone nippers, scalpels, and all other accessories necessary for the collection of natural-history [4] specimens. There were in my outfit three sets of photographic cameras, and a dozen dry plates, as well as all adjuncts for the developing, fixing, printing, etc., of the negatives. I had two complete sets of instruments for astronomical observations and for use in surveying. One set had been given to me by the Royal Geographical Society of London. The other was my own. Each set consisted of the following instruments. A six-inch sextant. The hypsometrical apparatus, a device used for measuring heights by means of boiling-point thermometers, which had been specially constructed for work at great elevations. It is well known that the higher one goes, the lower is the temperature at which water boils. By measuring the temperature of boiling water and at the same time the temperature of the atmosphere at any high point on a mountain, and working out a computation in relation to the boiling-point temperature of a given place on the sea-level, one can obtain with accuracy the difference in height between the two points.

Two aneroid barometers were also carried, which were specially made for me—one registering heights to 20,000 feet, the other to 25,000 feet. Although I used these aneroids principally for differential heights along my route, as aneroids cannot always be relied upon for great accuracy, I found on checking these particular instruments with the boiling-point thermometers that they were always extremely accurate. This was, however, exceptional, and it would not do for any one to rely [5] on aneroids alone for the exact measurement of mountain heights. There were in my outfit three artificial horizons—one with mercury, the others constructed with a plate glass. The latter had a special arrangement by which they could be levelled to a nicety. I found that for taking observations for latitude and longitude by the sun the mercury horizon was satisfactory, but when occultations had to be taken at night the plate-glass horizons were easier to work, and gave a more clearly defined reflection of stars and planets in such a bitterly cold climate as Tibet, where astronomical observations were always taken under great difficulty. The most useful instrument I carried on that expedition was a powerful telescope with astronomical eyepiece. Necessarily, I carried a great many compasses, which included prismatic, luminous, floating, and pocket compasses. Maximum and minimum thermometers were taken along to keep a record of the daily temperature, and I also took with me a box of drawing and painting materials, as well as all kinds of instruments for map-making, such as protractors, parallel rules, tape rules, section paper, note-books, etc. I had water-tight half-chronometer watches keeping Greenwich mean time, and three other watches. In order to work out on the spot my observations for latitude and longitude, I had with me such books as Raper's Navigation and the Nautical Almanac for the years 1897 and 1898, in which all the necessary tables for the computations were to be found.

I was provided with a light mountain tent, usually called a tente d'abri; it was seven feet long, four feet wide, and three feet high; it weighed four pounds. All I needed in the way of bedding was one [6] camel's-hair blanket. My clothing was reduced to a minimum. My head-gear was a mere straw hat, which was unfortunately destroyed at the beginning of my journey, so that I went most of the time with my head uncovered or else wore a small cap. I wore medium thick shoes without nails, and never carried a stick. It was largely due to the simplicity of my personal equipment that I was able to travel with great speed often under trying circumstances. Although the preparations for my expedition cost me several thousand dollars, I spent little money on medicines for myself and my men; in fact, all they cost me was sixty-two cents (two shillings and sixpence). I am firm in the belief that any healthy man living naturally under natural conditions, and giving himself plenty of exercise, can be helped very little by drugs.

I started from Naini Tal and rode to Almora (5510 feet above sea-level), the last hill-station toward the Tibetan frontier where I expected to find European residents. At this place I endeavored to obtain plucky, honest, wiry, healthy servants who would be ready, for the sake of a good salary and a handsome reward, to brave the many discomforts, hardships, and perils my expedition into Tibet was likely to involve. Scores of servants presented themselves. Each one produced a certificate with praises unbounded of all possible virtues that a servant could possess. Each certificate was duly ornamented with the signature of some Anglo-Indian officer—either a governor, a general, a captain, or a [7] deputy commissioner. What struck me mostly was that bearers of these testimonials seemed sadly neglected by those who had been so enthusiastically pleased with their services. They all began by begging, or else asked, for a loan of rupees in order to buy food, clothes, and support the dear ones they would be leaving behind.

I was sitting one day in the post resting-house when an odd creature came to offer his services. "Where are your certificates?" I asked.

"Sahib, hum 'certificates' ne hai" (Sir, I have no certificates).

I employed him at once. His facial lines showed much more character than I had noticed in the features of other local natives. That was quite sufficient for me. I am a great believer in physiognomy and first impressions, which are to me more than any certificate in the world. I have so far never been mistaken.

My new servant's dress was peculiar. His head was wrapped in a white turban. From under a short waistcoat there appeared a gaudy yellow and black flannel shirt, which hung outside his trousers instead of being tucked in them. He had no shoes, and carried in his right hand an old cricket-stump, with which he "presented arms" every time I came in or went out of the room. His name was Chanden Sing. He was not a skilful valet. For instance, one day I found him polishing my shoes with my best hair-brushes. When opening soda-water bottles he generally managed to give you a spray bath, and invariably hit you in the face with the flying cork. It was owing to one of these accidents that Chanden Sing, [8] having hurt my eye badly, was one day flung bodily out of the door. Later—as I had no more soda water left—I forgave him, and allowed him to return. It was this man who turned out to be the one plucky man among all my followers. It was he who stood by me through thick and thin during our trials in Tibet.

From Almora up to what is usually called Bhot (the country upon the Himahlya slopes on the British side of the frontier) our journey was through fairly well-known districts; therefore, I shall not dwell on the first portion of our route. I had some thirty carriers with me. We proceeded up and down, through thick forests of pine and fir trees, on the sides of successive mountain ranges.

We went through the ancient Gourkha town of Pithoragarh, with its old fort. Several days later I visited the old Rajah of Askote, one of the finest princes Northern India then possessed. I went to see the Raots, a strange race of savages living, secluded from everybody, in the forest. In a work called In the Forbidden Land a detailed description will be found of my experiences with those strange people, and also of our long marches through that beautiful region of the lower Himahlyas.

We reached at last a troublesome part of the journey—a place called the Nerpani, which, translated, means "the waterless trail." Few travellers had been as far as this point. I shall not speak of the ups and down at precipitous angles which we found upon the trail, which had been cut along the almost vertical cliff. Here and there were many sections of the trail which were built on crowbars thrust horizontally into the [9] rock. A narrow path had been made by laying over these crowbars large slabs of stone not particularly firm when you trod over them. As you went along this shaky path on the side of the precipice the drop down to the river at the bottom of the cliff was often from 1800 to 2000 feet, and the path in many places not wider than six inches. In other places the Nerpani trail consisted of badly put together flights of hundreds of steps along the face of the cliff.

It was at a place called Garbyang, close to the Tibetan boundary, that I made my last preparations for my expedition into Tibet. A delay at this place was inevitable, as all the passes over the Himahlya range were closed. Fresh snow was falling daily. I intended to cross over by the Lippu Pass, the lowest of all in that region; but having sent men to reconnoitre, I found it was impossible at that time to take up my entire expedition, even by that easier way.

I had a Tibetan tent made in Garbyang. Dr. H. Wilson, of the Methodist Evangelical Mission, whom I met at this place, went to much trouble in trying to get together men for me who would accompany me over the Tibetan border. His efforts were not crowned with success. The thirty men I had taken from India refused to come any further, and I was compelled to get fresh men from this place. The Shokas (the local and correct name of the inhabitants of Bhot) were not at all inclined to accompany me. They knew too well how cruel the Tibetans were. Many of them had been tortured, and men could be seen in Garbyang who had been mutilated by the Tibetans. Indeed, the Tibetans often crossed the border to come and claim dues and taxes and inflict punishment on the helpless Shokas, who were left unprotected by the Government of India.

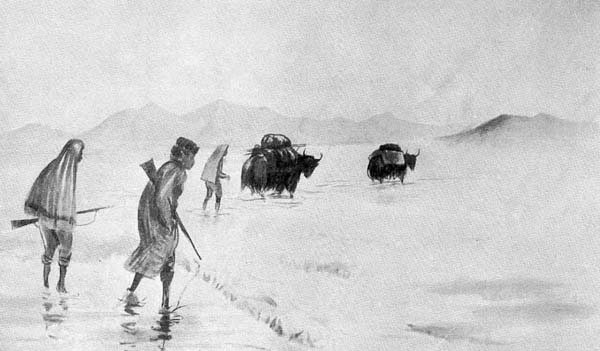

INVOLUNTARY TOBOGGANING

[11] The Jong Pen of Taklakot, a high official at the Tibetan frontier, upon hearing of my proposed visit, sent threats that he would confiscate the land of any man who came in my employ. He sent messengers threatening to cut off my head if I crossed the boundary, and promised to flog and kill any man who accompanied me. On my side I had spies keeping me well informed of his movements. He kept on sending daily messengers with more threats. He gathered his soldiers on the Lippu Pass, where he suspected I might enter his country.

Before starting with my entire expedition I took a reconnoitring trip with only a few men, in order to see what tactics I should adopt in order to dodge the fanatical natives of the forbidden land. To go and find new ways on virgin mountains and glaciers was not easy work. During our rapid scouting journey we had a number of accidents. Going over a snow-slope one day I slipped and shot down a snow-slope with terrific speed for a distance of three hundred yards, just escaping getting smashed to pieces at the end of this involuntary toboganning. One of my carriers, who carried a child on the top of one of my loads, had a similar accident, with the result that the child was killed.

On returning to Garbyang I found that the Tibetans had tried to set the natives against me. Tibetan spies travelled daily between Taklakot and Garbyang, in order to keep the Jong Pen informed of my movements. The [12] Jong Pen sent an impudent messenger one day to say that he had plenty of soldiers guarding the Lippu Pass, and that he would kill us all if we came. If he caught me alive he would cut off my head; my body, he said, he would sew in skins and fling into the river. I sent a messenger back to the Jong Pen to inform him that I was ready to start, and that I would meet him on the Lippu Pass; that he had better beware, and get out of my way. The messenger who brought him this news barely escaped with his life. He returned to me, saying that the Jong Pen was preparing for war, that he had gathered all his soldiers on the top of a narrow pass, where they had piled up a great number of large rocks and smaller ammunition to be rolled down upon us when we should be coming up the mountain-side.

Having collected men enough, after much trouble, I one day unexpectedly mustered them, and that same night made a sudden start. The Tibetans, suspecting that I might be leaving that day, cut down the bridge over a rapid and deep torrent forming the boundary between India and Nepal. This inconvenienced me, as I had to find my way on our side of the stream, which was very rugged. This gave us additional trouble. Some of the precipices we had to cross were extremely dangerous.

I reached the highest village in the Himahlyas, a place called Kuti, at an elevation of 12,920 feet. Here I hastily made my final preparations for the last dash across the frontier. Every available Shoka had joined my party, and no inducement brought more volunteers. I needed two extra men. Two stray shepherds turned up half famished and naked, with long, unkempt heads of hair, and merely a coral necklace and a silver bangle [13] by way of clothing. With these two men my little force was brought up to thirty strong.

One of the two shepherds interested me. He was sulky. He seldom uttered a word, and when he did, he never spoke pleasantly. He looked painfully ill. Motionless, he would sometimes stare at a fixed point as if in a trance. His features were peculiarly refined and regular, but his skin had the ghastly, shiny, whitish tinge peculiar to lepers. I paid no special attention to him at first, as I was busy with other matters; but one day while on the march I examined him carefully, and discovered that the poor fellow had indeed all the symptoms of that most terrible of all diseases, leprosy. His distorted and contracted fingers, with the skin sore at the joints, were a sad and certain proof. I examined his feet, and found further evidence that the man was a leper.

"What is your name?" I inquired of him.

"Mansing," he said, dryly, becoming immediately again absorbed in one of his dreamy trances.

In looking over my followers I was amused to see what a strange mixture they were. There were Humlis and Jumlis, mountain tribesmen living near the Tibetan border; they wore their long black hair tied into small braids and a topknot. There were Tibetans, Shokas, Rongbas, Nepalese—all good mountaineers. Then there were Chanden Sing and Mansing belonging to the Rajiput caste. There were a Brahmin, two native Christians, and a Johari. Then Doctor Wilson. What a collection! What a [14] confusion of languages and dialects! An amusing feature of this odd crowd was that each particular caste looked down upon all the others. This, from the beginning, occasioned a good deal of trouble among my men. I was glad of this, as it seemed a sort of guarantee that they would never combine against me. One of the most peculiar men I had with me was a Tibetan brigand, a man with the strength of an ox. His history did not bear a close examination. He had killed many people. He asked to be employed by me, as he had quarrelled with his wife, and refused to live with her any longer. In camp he went by the name of Daku (the brigand). The son of one of the richest traders of Garbyang, a young fellow called Kachi, also accompanied me. He was intelligent, and could speak a few words of English. I had employed him to look after the men and to act as interpreter, if necessary. His uncle Dola was employed in the capacity of valet and cook.

Instead of proceeding by the Lippu Pass, where the Jong Pen was waiting for me with his men, I made forced marches from Kuti in a different direction altogether. I meant to cross over by a high untrodden pass, practically unknown, where no one could suspect that a caravan would enter Tibet. My men were good. We marched steadily for several days over very rough country, getting higher and higher toward the eternal snows. We suffered considerably in crossing the rapid and foaming torrents. They were often quite deep, and the water was so cold from the melting snows that we were nearly frozen each time we waded through them. We crossed several large flat basins of stones and gravel which appeared [15] to have been lake-beds. In these basins we found deltas, formed by the stream dividing in various directions. We suffered tortures in crossing barefooted one cold stream after another. Some of my men narrowly escaped frost-bites, and it was only after rubbing their feet violently that the intense pain ceased and circulation was at last restored. The soles of my feet and my toes were badly cut and bruised. Every stone in the streams seemed to have a sharp edge. I, too, suffered agony after I had been in the water for some time. Never until that day did I know what a great comfort it was to possess a pair of warm socks! The last basin we crossed was at an elevation of 15,400 feet. We made our camp there. The thermometer registered a minimum temperature of 24°, whereas the maximum temperature that day was 51° Fahrenheit.

One of the main drawbacks of travelling at great elevations was the want of fuel. There was not a tree, not a shrub, to be seen near our camp. Nature wore her most desolate and barren look. Failing wood, my men dispersed to collect and bring in the dry dung of yaks, ponies, and sheep to serve as fuel. Kindling this was no easy matter. Box after box of matches was quickly used, and our collective lung-power severely drawn upon in blowing the unwilling sparks into a flame a few inches high. Upon this meagre fire we attempted to cook our food and boil our water (a trying process at great elevations). The cuisine that night was not of the usual excellence. We had to eat everything half-cooked, or, to be accurate, practically uncooked. The night was a bitterly cold [16] one, and snow was falling heavily. When we rose in the morning snow was two feet deep around us. The glare was painful to our eyes. I mustered my men. Mansing was missing. He had not arrived the previous night, and there was no sign of the man I had sent in search of him. I was anxious not only for the man, but for the load he carried—a load of flour, salt, pepper, and five pounds of butter. I feared that the poor leper had been washed away in one of the dangerous streams. He must, at any rate, be suffering terribly from the cold, with no shelter and no fire.

It was long after sunrise when, with the aid of my telescope, I discovered the rescued man and rescuer coming toward us. They arrived in camp an hour or so later. Mansing had been found sound asleep, several miles back, lying flat by the side of the empty butter-pot. He had eaten all the butter. When we discovered this every one in camp was angry. The natives valued fat and butter as helping to keep them warm when going over those cold passes. With much trouble I rescued Mansing from the clutches of my other men, who wanted to punish the poor leper severely. In order that this might not happen again, I ordered Mansing to carry a heavy load of photographic plates and instruments, which I thought would not prove quite so appetizing.

While we were camping a flock of some six hundred sheep appeared, and with them some Tibetans. As I had pitched my Tibetan tent, they made for it, expecting to find some of their own countrymen. Their confusion was amusing when they found themselves face to face with Doctor Wilson and [17] myself. Hurriedly removing their fur caps, they laid them upon the ground and made a comical bow. They put out their tongues full length, and kept them so until I made signs that they could draw them back, as I wanted them to answer several questions. This unexpected meeting with us frightened them greatly. They were trembling all over with fear. After getting as much information as they seemed to have, I bought their fattest sheep. When the money was paid there was a further display of furred tongues, and more grand salaams when they departed, while all hands in my camp were busy trying to prevent our newly purchased animals from rejoining the flock moving away from us. On our next march these animals were a great trouble. We had to drag them most of the way. Kachi, who had been intrusted with a stubborn, strong beast, which I had specially promised my men for their dinner if they made a long march that day, was outwitted by the sheep. It freed its head from the cord with which Kachi was dragging it, and cantered away full speed in the opposite direction to the one in which we were travelling. It is well known that at great altitudes running is a painful operation, for the rarefied air makes such exertion almost suffocating. Yet Kachi, having overcome his first surprise, was soon chasing the escaped beast, and, urged by the cheers of my other men, succeeded, after an exciting race, in catching the animal by its tail. This feat is easier to describe than to accomplish, for Tibetan sheep have very short, stumpy tails. Kachi fell to the ground exhausted, but he held fast with both hands to his [18] capture, and finally the animal was secured with ropes.

Climbing over rolling ground, we rose to a pass 15,580 feet high—over a thousand feet higher than Pike's Peak, in Colorado. Then crossing a wide, flat land, we followed the Kuti River, with its high, snowy mountains to the west and east. The line of perpetual snow was at 16,000 feet; the snow below this level melted daily, except in a few shaded places. Red and white flowers were still to be seen, though not in such quantities as lower down. We saw many pairs of small butterflies with black-and-white wings.

After a while there was yet another bitterly cold stream to ford, two small lakes to skirt, and three more deep rivers to wade, with cold water from the snows reaching up to our chests. We had to make the best way we could through a large field of iron-bearing rock, which so affected my compass that for the time it became quite unreliable, owing to its deviation.

Mile after mile we marched over sharp stones, wading through another troublesome delta fully a mile in width with eight streams, and crossing a flat basin of pointed pebbles. At last, to our great comfort, we came to smooth grass-land.

Here the Kuti River flowed through a large basin, not unlike the one near which we had camped the night before. It looked like the bed of a lake, with high vertical rocks on the left. As we went on to the north-west the basin became wider and the Kuti River turned to the north-west, while the Mangshan River, descending from the east, joined [19] the first stream in the centre of the basin. In wading through the numerous branches of the two rivers we felt more than ever the trials and weariness of the day before. The water seemed colder than ever. Our feet were by this time in a dreadful condition, bleeding and sore, because it was constantly necessary to walk barefooted rather than keep removing our foot-gear every few minutes. Aching and chilled, we stumbled on, in and out of the water, always treading, it seemed, on sharply pointed stones. The pain had to be borne patiently. At last we reached our camping-ground, situated under the lee of the high chain of mountains to the north of us and on the northern bank of the Mangshan River. Directly in front of us stood the final obstacle—the great backbone of the Himahlyas. Once across this range, I should be on the high Tibetan plateau so accurately described as "the roof of the world."

From Kuti I had sent a sturdy Shoka named Nattoo to find out whether it was possible to cross the Himahlyan chain over the high Mangshan Pass. In case of a favorable report, I should be able to get several marches into Tibet without fear of being detected. I reckoned on turning the position occupied by the force of soldiers which I was informed the Jong Pen of Taklakot had gathered on the Lippu Pass in order to prevent my entering his country. Before the Tibetans could have time to find where I was, I should be too far into the forbidden land for them to catch me up. Nattoo duly returned. He had been half-way up the mountain. The snow was deep, and there were huge and treacherous cracks in the ice. An avalanche had fallen, and it was merely by a miracle that he had escaped with his life. He had turned back without reaching the summit of the pass. He was scared and worn out, and declared it was impossible for us to proceed that way. The thrilling account of the Kutial's misfortunes discouraged my men. What with the intense cold, the fatigue of carrying heavy loads at high elevations over such rough country, and the dreaded icy-cold rivers which they had crossed so often, my carriers became [21] absolutely demoralized at the thought of new hardships ahead. I did not believe Nattoo. I determined to go and see for myself.

It was half-past four in the afternoon, and therefore some little time before sunset. There should be moonlight. I had on that day marched eight miles. It must be remembered that at high elevations the effort of walking eight miles would be as great as to walk twice as far at lower altitudes. Though my feet were wounded and sore, I was not tired. Our camp was at a height of 16,150 feet, an elevation higher than the highest mountain in Europe. Doctor Wilson insisted on accompanying me on my reconnoitring trip. Kachi Ram and a Rongba coolie also volunteered to come. Bijesing, the Johari, after some persuasion, got on his feet to accompany our little exploration party. Chanden Sing was left in charge of the camp, with strict orders to punish severely any one who might attempt to escape during my absence.

We set out, following up-stream the course of the Mangshan River boxed in between high cliffs which finally met at the glacier at the foot of the Mangshan Mountain, about three miles east-south-east of our camp. It was very hard to walk over the large, slippery stones, where one's feet constantly slipped and were jammed between rocks, straining and hurting the ankles. Since I did not trust my demoralized followers, who seemed on the verge of mutiny, I did not care to leave behind in camp the heavy load of silver rupees (R. 800) sewn in my coat. I always carried that sum on my person, as well as my rifle, two compasses (a prismatic and a [22] luminous), two aneroids, one half-chronometer and another watch, and some thirty rifle cartridges. The combined weight of these articles was considerable, and on this particular afternoon it was almost too much for my strength. We travelled up and down the series of hillocks, and in and out of the innumerable channels that centuries of melting snow and ice had cut deep into the mass of loose stones. At the point where the two ranges met there stood before us the magnificent pale-green ice-terraces of the Mangshan glacier, surmounted by great snow-fields rising to the summit of the mountain range. Clouds enveloped the higher peaks. The clear ice showed vertical streaks, especially in the lower strata, where it was granulated. The base, the sides, and top of the exposed section were covered with a thick coat of snow. The Mangshan River rose from this glacier.

We left the glacier (17,800 feet above sea-level), to the right, and, turning sharply northward, began our ascent toward the pass. The snow we struggled over was so soft and deep that we sank into it up to our waists. Occasionally there was a change from snow to patches of loose débris and rotten rock. The fatigue of walking on such a surface was simply overpowering. Having climbed up half a dozen steps among the loose, cutting stones, we would slide back almost to our original point of departure, followed by a small avalanche of shifting material that only stopped when it got to the foot of the mountain.

At a height of 19,000 feet we walked for some time on soft snow, which covered an ice-field with deep crevasses and cracks. We had to feel our [23] way with great caution, particularly as by the time we reached that spot we had only the light of the moon to depend upon.

As we rose higher, I began to feel a curious exhaustion that I had never experienced before. At sunset the thermometer which Kachi carried had fallen 40° within a few minutes, and the sudden change in the temperature seemed to affect us all. We went on, with the exception of Bijesing, who was seized with such violent mountain sickness that he was unable to proceed. The doctor, too, a powerfully built man, was suffering considerably. His legs, he said, had become like lead, and each seemed to weigh a ton. The effort of lifting, or even moving, them required all his energy. Although he was gasping pitifully for breath, he struggled on bravely until we reached an elevation of 20,500 feet. Here he was overcome with exhaustion and pain, and he was unable to go further. Kachi Ram, the Rongba, and I went ahead, but we also were suffering, Kachi complaining of violent beating in his temples and loud buzzing in his ears. He gasped and staggered dangerously, threatening to collapse at any moment. At 21,000 feet he fell flat on the snow. He was instantly asleep, breathing heavily and snoring convulsively. His hands and feet were icy cold. What caused me more anxiety than anything was the irregular beating and throbbing of his heart. I wrapped him up in his blanket and my waterproof, and, having seen to his general comfort, I shouted to the doctor (the voice in the still air carrying for a long distance) telling him what had happened. I pushed on with the Rongba, [24] who was now the only one of the party who had any strength left.

A thick mist suddenly enveloped us, which added much to our trials. After we left Kachi at 21,000 feet we made desperate efforts to get on. Our lungs seemed about to burst, and our hearts throbbed as if they would beat themselves out of our bodies. Exhausted and weighed down by irresistible drowsiness, the Rongba and I at last reached the summit. Almost fainting with fatigue, I registered my observations. The altitude was 22,000 feet, the hour 11 p.m. There was a strong, cutting north-easterly wind. The cold was intense. I was unable to register the exact temperature, as I had forgotten to take my thermometer out of Kachi's pocket when he collapsed. The stars were wonderfully brilliant, and when the mist cleared the moon shone brightly for a while over the panorama around me. Though it was a view of utter desolation, it was certainly strangely attractive. The amount of snow on the northern slope of the range was greater than on the southern. I realized the impossibility of taking my entire expedition over this high point. Below me, to the south, were mountainous ranges buried in snow, and to the south-west and north-east were peaks even higher than the one where I stood. To the north stretched the immense, dreary Tibetan plateau with undulations and intricate hill ranges, beyond which a high mountain range with snow-peaks could just be perceived in the distance.

I had barely taken in this beautiful view of nature asleep when the mist [25] again rose before me, and I saw a huge ghost rising out of it. A tall, dark figure stood in the centre of a luminous circle wrapped in an enormous veil of mist. The effect was wonderful. It was only after some moments that I realized that the ghost had my features, and that I stood in the centre of a circular lunar rainbow, looking at an enlarged reflection of myself in the mist. When I moved my arms, my body, or my head the ghost-like figure moved also. I felt very much like a child placed for the first time in front of a mirror, as I made the great image move about and repeat any odd motion that I might make. On a later occasion I saw a spectre, when the sun was up, with a circular rainbow round it. The moonlight effect differed from this, in that the colors of the rainbow were but faintly distinguishable.

The Rongba had fallen exhausted. I felt so faint with the unusual pressure on my lungs that, despite all the efforts to resist it, I also collapsed on the snow. The coolie and I, shivering pitifully, shared the same blanket in order to keep warm. Both of us were seized with irresistible sleepiness. I fought hard against it, for I well knew that if my eyelids once closed they would almost certainly remain so forever. The Rongba was fast asleep. I summoned my last atom of vitality to keep my eyes open. The bitter wind hissed by us. How that hiss still echoes in my ears! The Rongba crouched down, moaning through chattering teeth. His sudden shudders showed that he was in great pain. It seemed only common charity to let him have the entire blanket, which was in any case [26] too small for both. I wrapped it tightly round his head and his doubled-up body. The exertion was too much for me. In absolute exhaustion I fell back on the snow. I made a last desperate effort to look at the glittering stars ... my sight became dim....

How long this semi-consciousness lasted I do not know. "This is terrible! Doctor! Kachi!" I tried to speak. My voice seemed choked in my throat. Was what I saw before me real? On the vast white sheet of snow Kachi and the doctor lay motionless, like statues of ice, as if frozen to death. In my nightmare I tried to raise them. They were rigid. I knelt beside them, calling them, and striving with all my might to bring them back to life. Half dazed, I turned to look for Bijesing, and, as I did so, all sense of vitality seemed to freeze within me. I saw myself enclosed in a quickly contracting tomb of transparent ice. I felt that I, too, would shortly be frozen to death like my companions. My legs, my arms, were already icy. Horror-stricken as I was at the approach of such a ghastly death, I felt a languor and sleepiness far from unpleasant. Should I let myself go, choosing rest and peace rather than effort, or should I make a last struggle to save myself? The ice seemed to close in more and more every moment. I was suffocating.

I tried to scream, to force myself through the ice, which seemed to crush me. I gave a violent plunge. Then everything vanished ... the frozen Kachi, the doctor, the transparent tomb....

I opened my eyes. They ached as if needles had been stuck into them. It was snowing hard. I had temporarily lost the use of my legs and fingers. [27] They were almost frozen. In waking up from the ghastly nightmare, I realized instantly that I must get down at once to a lower level. I was already covered with a layer of snow. It was snowing hard when I woke, and I suppose it was the cold snow on my forehead that caused my nightmare. It is quite probable that, had it not been for the sudden shudder which shook me free, I should never have awakened.

I sat up with difficulty, and slowly regained the use of my lower limbs by rubbing and beating them. I roused the Rongba, rubbed him, and shook him till he was able to move. We began our descent.

Undoubtedly the satisfaction of going up high mountains is great, but can it ever be compared to the delight of coming down again?

The incline being extremely steep, we took long strides on the snow. When we came to patches of débris we slid down at a great pace amid a deafening roar from the huge mass of loose stones set in motion by our descent. It was still snowing.

"Hark!" I said to the Rongba. "What is that?"

With hands up to our ears we listened attentively.

"Ao, ao, ao! Jaldi ao! Tumka hatte?" (Come, come, come! Come quickly! Where are you?) cried a faint, distressed voice from far down below.

We quickened our pace. With hardly any control over our legs our descent was precipitous. The snow-fall ceased, and we became enveloped in a freezing thick mist which pierced into our very bones.

Guided by the anxious cries of the doctor, we continued our breakneck [28] journey downward. The cries became more and more distinct, and at last we came face to face with Wilson, still helpless.

He had been uneasy about us, and during our long absence had quite given us up for lost.

We looked for and found Kachi. He had slept like a top, curled up in his warm blanket and my waterproof coat. He was now quite refreshed. All together we continued our race downward with no serious mishaps. Life and strength gradually came back to us when we descended to lower heights.

Over the same trying stony valley we reached camp in the morning. The anxiety of my men in camp was intense. They had lost all hope of seeing us again.

A few hours' rest, a hearty meal, and by 9 a.m. we were ready again to start, this time with the entire expedition, over the easier Lumpiya Pass. The thermometer registered 40° inside the tent. The minimum temperature outside, during the night, had been 14°. We followed the Kuti River at the foot of the mountain range. On rounding a prominent headland, where the Kuti River flowed through a narrow passage, we saw on a mound fourteen stone pillars and pyramids with white stones on them and some Tibetan "flying prayers," mere strips of cloth flapping in the wind. It was from this point that the ascent of the Lumpiya Pass began.

Our route gradually ascended, going north-west first, then swinging away to the north-east, until we attained an elevation of 17,350 feet on a flat basin covered with deep snow. So far we had gone on with no great trouble, but matters suddenly changed for the worse. Each coolie in the long silent row at the head of which I marched sank in snow up to his knees, often up to his waist. Their dark faces, wrapped tightly round in turbans, stood out in sharp contrast upon the white background. Some wore fur caps with ear-flaps. All had sheepskin coats and high boots. Many used snow-spectacles. Watching this silent procession of men with [30] heavy loads upon their backs, struggling higher and higher with piteous panting, one could not help wondering anxiously as to how many of them would return to their own country alive. Moving cautiously to avoid treacherous crevasses, I made my way ahead to a spot six hundred feet higher, where I halted for a while on a rocky island fairly clear of snow. As coolie after coolie arrived panting hard, he dropped his load and sat quietly by the side of it. There was not a grumble, not a word of reproach for the hard work they were made to endure. Sleet was falling, and everything was wet and cold. From this point there was a steep pull before us. To the left we had a glacier, the face of which was a precipitous wall of ice about one hundred feet in height. Like the Mangshan glacier, it was in horizontal strata of beautifully clear ice with vertical stripes of dark green.

The doctor and I went ahead. In our anxiety to reach the summit we mistook our bearings. With great fatigue we climbed an extremely steep incline. Here we were on a patch of troublesome loose stones, on which we struggled for over half an hour, until we reached the summit of the range, 18,750 feet—considerably higher than the pass itself. Most of the other men had proceeded by a dangerous way skirting the glacier.

The wind from the north-east was piercing, and the cold intense. From this high point we obtained a beautiful bird's-eye view of the Tibetan plateau. Huge masses of snow covered the Tibetan side of the Himahlyas, as well as the lower range of mountains immediately in front of us, [31] lying almost parallel to our range. Two thousand feet below, between these two ranges, flowed, in a wide barren valley, a river called the Darma Yankti. This river is the principal source of that great river which afterward takes the name of Sutlej. I was glad to be the first white man to visit the place where it has its birth. In the distance a flat plateau, rising some eight hundred feet above the river and resembling a gigantic railway embankment, could be seen for many miles. Far away to the north stood a chain of high blue mountains capped with snow—undoubtedly the Gangri chain with the Kelas peaks.

The strain of exertion in this rarefied air brought about a painful incident. Exhausted from cold and fatigue, a man called Rubso, a Christian convert, was seized with cramp. He was lying in a semi-conscious state, his teeth chattering, his features distorted and livid; his eyes were sunken and lifeless. We carried him under the shelter of a rock and rubbed him vigorously, endeavoring to restore his circulation. He eventually recovered enough to come along.

From our high point we now had to descend to the pass six hundred feet lower. We made our way along dangerous rocks and débris. I was clinging, with half-frozen fingers, to a prominent rock when I heard screams of distress from below. On the steep incline of snow two coolies, with their respective loads, having lost their footing, were sliding at an incredible speed. They finally reached the bottom of the basin, where the change in the descent made them turn involuntary somersaults, while [32] their loads flew off in every direction. I was relieved when I saw the men getting up again. One of them staggered, and fell back a second time as if dead. Hastening over the slippery rocks, and then down over loose stones, I reached the pass. This was 18,150 feet above the sea. Two reluctant men were sent to the relief of the coolie in distress. He and his load were at last carried up to the place where I was. He had been badly shaken and was aching all over, but was able to continue with us.

We hurried down the steep slope on the Tibetan side, to get away quickly from the bitterly cold, windy pass. Describing a wide curve, and then across several long snow-beds, we at last reached the river-level, and pitched our tents on snow at an elevation of 16,900 feet. There was no wood; no yak or pony dung, no lichens, no moss, and therefore nothing with which we could make a fire. My men believed that eating cold food at high elevations, when the temperature was low, led to certain death. They preferred to remain without food altogether. Night came, and with it the wind blowing in gusts, and piling the grit and snow around our tents. In the night, when a hurricane was raging, we had to turn out of our flapping canvasses several times to make the loosened pegs firmer. Refastening the frozen ropes was icy-cold work. At 2 a.m. the thermometer was down to 12°; at 9 a.m., in the sun, it went up to 26°, and inside the tent at the same hour we had a temperature of 32°—freezing-point.

[33] In a hurricane of grit and drenching rain we packed our traps as best we could and again started. To my surprise, as I was marching ahead of my men, I noticed, some two hundred yards from my former camp, a double line of recent footmarks in the snow. Those coming toward us were somewhat indistinct and nearly covered with grit; those going in the opposite direction seemed quite recent. After carefully examining these footprints, I became certain that they had been left by a Tibetan. Where the footprints were nearest our camp, marks in the snow showed that the man had at different points laid himself flat on the snow. We had evidently been spied upon and watched during the night. My men, who were already showing fear of the Tibetans, were now all anxiously stooping over these footprints. Some of them thought that the stranger must be a daku (a brigand), and that at night we should be attacked by the whole band; others maintained that the spy could only be a soldier sent by the Gyanema officers to watch our movements. This incident was held by them as an evil omen.

We were travelling on flat or slightly rolling barren ground. We waded across another cold river with water up to our waists. My men became so tired that one mile further we were obliged to halt. The elevation of this point was 16,650 feet.

The cold was intense. Again we had no fuel of any kind. A furious wind was blowing. Snow fell heavily in the evening. My carriers, half starved, ate a little satoo (a kind of oatmeal), but Chanden Sing, a Rajiput, could not, without breaking his caste, eat his food without undressing. It was two days since he had eaten his last meal, but [34] rather than break the rules of his religion, or take off his clothes when it was so cold, he chose to curl up in his blanket and go to sleep fasting.

Inside the tent the temperature was 28° Fahrenheit, or below freezing-point. There was a foot of snow upon the ground, and it was snowing heavily. The carriers, huddled close together so as to keep warm, attempted to sleep in order to forget their hunger.

Two or three hours later the weather cleared. The coolies, half starved, came to complain that they were again unable to find fuel to cook their food, and that they would leave me. It was a trying time. I immediately took my telescope and climbed to the top of a small mound. It was curious to see how much faith the coolies had in this spy-glass. They believed, in a child-like fashion, that with it I could see through mountains. I came down with the good news that one day's march beyond would bring us to a spot where fuel was plentiful.

They cheerfully hastened to pack up the loads, and set forth with unusual energy in the direction I had pointed out. We followed a course parallel to the high, flat plateau on the other side of the stream. This snow-covered plateau extended from south-west to north-east. Beyond it to the north could be seen some high, snowy peaks—in all probability the lofty summits south-east of Gartok. To our right we were flanked by high, rugged mountains, with streams here and there dashing down their sides. Six hours' brisk marching took us to a sheltered spot where a few [35] lichens and shrubs were growing. If we had suddenly descended into the Black Forest of Germany or the Yosemite Valley with their gigantic trees centuries old, our delight could not have been greater, yet the tallest of these shrubs stood no higher than six or seven inches from the ground, while the biggest piece of wood we collected was no larger around than an ordinary pencil. With all possible haste all hands went to work to root up these plants for fuel.

When night came the same number of hands were busy cooking and swiftly ladling out such steaming food as was available from the different pots to the mouths of the famished coolies. Happiness reigned in camp. All recent hardships were forgotten.

A fresh surprise was awaiting us when we rose. Two Tibetans disguised as beggars came to our camp. They pretended to be suffering from cold and starvation. I gave orders that they should be properly fed and kindly treated. On being cross-examined they confessed that they were spies sent by the officer at Gyanema to find out whether a white man had crossed the frontier, and whether we had seen him.

We had so many things to attend to in the morning, and it was so cold, that washing had really become a nuisance. I, for my part, gave it up, at least for the time. We were sunburnt, and we wore turbans and snow-glasses, so the Tibetans departed under the impression that our party consisted of a Hindoo doctor, his brother, and a caravan of servants (none of whom had seen a white man), and that we were now on a pilgrimage to the sacred Mansarowar Lake and Kelas Mount.

In the presence of the men we treated this as a great joke, but, all [36] the same, Wilson and I anxiously consulted as to our immediate plans. Should we make a rapid march during the night over the mountain range to our right, and strike east by the wilds, or should we face the Gyanema leader and his soldiers?

We decided to meet them rather than go out of our way. I gave orders to break camp at once.

We altered our course from north to north-east, rising to 16,600 feet. We arrived at Lama Chokten, a pass protected by a Tibetan guard. The soldiers quickly turned out, matchlocks in hand. They seemed a miserable lot. They offered no resistance, but begged for money and food. The men complained of ill-treatment from their superiors. They received no pay, and even food was only occasionally sent to them at this outpost. Their tunics were in rags. Each man carried a sword stuck in front through the girdle. Here, too, we had more inquiries about the young sahib, the white man. Messengers on horseback had been sent post-haste from Taklakot to warn the Gyanema officer not to let him penetrate into Hundes (the Tibetan name for Tibet) should he attempt to come by the Lumpiya Pass. Their description of my supposed appearance was amusing enough to me, and when they said that if the sahib came their way they would cut off his head, I felt so touched by their good-natured confidence that I wanted to distribute a few rupees among them.

"Don't give them anything, sir," said Kachi and the doctor. "These fellows are friends of the dacoits. If these get to know that you have [38] money, we shall run great risk of being attacked by them."

I insisted on giving them a present.

"No, sir," cried Kachi; "do not do it, or it will bring us trouble and misfortune. If you give them four annas, that will be ample."

Accordingly the commanding officer had this large sum deposited in his outstretched palm. To show his satisfaction, he put out his tongue to its full length, waved both hands in sign of gratitude, bowing clumsily at the same time. His fur cap had been previously removed and thrown on the ground. It was a great deal of ceremony over a gift which amounted to somewhat less than eight cents.

From this place I saw a beautiful sight. To the north the clouds had scattered, and the snow-covered sacred Kelas Mountain rose up before us. Not unlike the graceful roof of a temple, Kelas towered over the long, white-capped range, contrasting in its beautiful blending of tints with the warm sienna color of the lower elevations. Kelas was some two thousand feet higher than the other peaks of the Gangri chain. It showed strongly defined ledges and terraces marking its stratification, and these were covered with horizontal layers of snow of brilliant white in contrast to the dark, ice-worn rock. The Tibetans, the Nepalese, the Shokas, the Humlis, Jumlis, and Hindoos, all had a strong veneration for this mountain, which was believed by them to be the abode of all the good gods, especially the god Siva. In fact, the ledge round its base [39] was said by the Hindoos to be the mark of the ropes used by the devil "Rakas" in his effort to pull down the throne of Siva.

My men, with heads uncovered, their faces turned toward the sacred peak, were muttering prayers. With joined hands, which they slowly raised as high as the forehead, they prayed fervently, and then went down on their knees, with heads touching the ground. My brigand follower, who was standing close by me, hurriedly whispered that I should join in the prayers.

"You must keep friends with the gods," said the bandit; "misfortune will attend you if you do not bow to Kelas. That is the home of a good god!" And he pointed to the peak with the most devout air of conviction.

To please him, I saluted the mountain with great deference, and, imitating the example of my men, placed a white stone on one of the Choktens or Obos (stone pillars). Hundreds of these had been erected at this place by devotees. These Obos, or rough pyramids of stones, were to be found on the paths over high passes, near lakes, and at the source of rivers. At no place had I seen so many as at Lama Chokten. Each passer-by deposited a white stone on one of these Obos. This was supposed to bring good fortune.

The guard-house itself, of rough stone, would in any country but Tibet be recognized as better fitted for pigs than for human beings.

Having gone a mile or so further, as the sun was fast disappearing we searched for a suitable spot to pitch our tents. There was no sign of water, only the stony bed of a dried rivulet. We were discussing the [40] situation when we heard a faint sound of rushing water. It grew louder and louder, and then we saw coming our way a stream of limpid snow-water gradually creeping over a bed of stones. Evidently the snow of the mountains, which had melted during the day, had only now reached the spot where we stood. My brigand was greatly excited.

"Water flowing to you, sahib!" he exclaimed, with his arms outstretched. "You will have great luck! Look! Look! You want water for your camp, and a stream comes to you! Heaven blesses you. You must dip your fingers into the water as soon as it comes up to you, and throw some drops over your shoulders. Fortune will then attend you on your journey."

I readily fell in with this Tibetan superstition. We all dipped our fingers and sprinkled the water over our backs. Wilson, however, who took the matter quite seriously, said it was all nonsense, and would not give in to such "childish superstitions."

In front of our camp was a great stretch of flat alluvial land, about ten miles long and fourteen wide, which apparently had once been the bed of a lake. With my telescope I could see at the foot of a small hill the camping-ground of Karko. There were many tents. My men seemed reassured when by their shape and color we made out the tents to be those of Joharis from Milam, who came over to this place to trade with the Tibetans. Beyond Karko to the north a stretch of water, the Gyanema Lake, shone brilliantly, and beyond it could be seen comparatively low hill ranges. In the distance more snowy peaks were visible.

[41] On leaving camp we traversed the plain for six miles in a north-easterly direction, and then turned into a smaller valley well enclosed by hills, which we followed for a distance of three or four miles.

During our march we saw many herds of kiang (wild horse). They came close to us. They resembled zebras, except that they were light brown in color. Their graceful and coquettish ways were most attractive. The natives regarded the proximity of these animals as dangerous, for their apparent tameness was merely in order to get quite near the unwary traveller, and then, with a sudden dash, inflict a horrible bite.

Having climbed over a hill range, we descended on the other side into a grassy stretch of flat land with a lake on the northern side. On a hill south of the lake stood the Gyanema fort, a primitive, tower-like structure of stone, with a tent pitched over it to answer the purpose of a roof. Two dirty white rags hung from a flagstaff. These were not national flags, but merely wind-prayers. Lower down, at the foot of the hill, were two or three large black tents and a small shed of stone. Hundreds of black, white, and brown yaks[1] were grazing on the green patches of grass.

The appearance of our party evidently frightened everybody, for we had hardly shown ourselves on the summit of the pass when in the fort a gong began to sound loudly, filling the air with its metallic notes. A shot was fired. Soldiers with their matchlocks[2] ran here and there. They [42] pulled down one of the black tents and hastily conveyed it inside the fort. The greater part of the garrison sought shelter within the walls of the fort with the hurry almost of a stampede. When, after some time, they made up their minds that we did not mean to hurt them, some of the Tibetan officers, followed by their men, came trembling to meet us. The doctor, unarmed, went ahead to talk to them, while Chanden Sing and I remained with the coolies in order to protect our baggage in case of a treacherous attack, and to prevent my frightened carriers from abandoning their loads and escaping. Matters looked peaceful enough. Rugs were spread on the grass, and finally we all sat down. An hour of tiresome talking with the Tibetan officers, while the same things were repeated over and over again, led to nothing. They said they could on no account allow any one from India, whether native or sahib, to proceed, and we must go back. We, on our side, stated that we were doing no harm. We were pilgrims to the sacred Lake of Mansarowar, only a few miles farther. We had gone to much expense and trouble. How could we now turn back when so near our goal? We would not go back, and trusted they would allow us to proceed.

We treated them courteously. Probably mistaking this for fear, they promptly took advantage of it, especially the Magbun, the General-in-Chief in charge of the Gyanema fort. His humble manner, of which at first he had made so much display, suddenly turned into arrogance.

"You will have to cut off my head," said he, with a vicious [43] countenance, "or, rather, I will cut off yours, before I let you go another step."

"Cut off my head!" I cried, jumping on my feet and shoving a cartridge into my rifle.

"Cut off my head!" repeated Chanden Sing, pointing with his Martini-Henry at the official.

"Cut off our heads!" exclaimed the Brahmin, angrily, and the two Christian servants of Dr. Wilson, while they handled a Winchester and a couple of Gourkha kukris (large knives).

"No, no, no, no! Salaam, salaam, salaam!" shouted the Magbun, with the quickness of a panic-stricken man. "Salaam, salaam," repeated he again, bowing down to the ground, tongue out, and placing his hat at our feet in a disgustingly servile manner. "Let us talk like friends."

The Magbun's men, no braver than their master, shifted about in a casual manner, so as to be behind their superior officers in case of our firing. On second thought, feeling that they were not safe even so screened, they got up. One after the other the Tibetans walked away for half-a-dozen steps slowly, to impress upon us that it was not fear that made them leave, and then took to their heels.

The Magbun and the officers who remained became meek. We spoke and argued in a friendly manner for two long hours, but with no result. The Magbun could not decide of his own accord. He would consult with his officers, and he could give us an answer no sooner than the next [44] morning. In the mean time he would provide for our general comfort and insure our safety, if we would encamp near his tent. This, of course, I well knew to be a trick to gain time, so as to send for soldiers to Barca, north of the Rakastal Lake, as well as to all the neighboring camps. I frankly told him my suspicions, but added that I wished to deal fairly with the Tibetan authorities before resorting to force. I reminded the Magbun again and made him plainly understand that we were merely peaceful travellers, and had not come to fight; that I was paying tenfold for anything I purchased from him or his men, and was glad to do so; but at the same time, let any one beware who dared touch a single hair of a member of my party! The Magbun declared that he understood perfectly. He swore friendship, and as friends he begged us to stop over the night near his camp. By the Sun and Kunjuk Sum (Trinity) he gave a solemn oath that we should in no way be harmed. He took humble leave of us and retired.

The doctor and I had been sitting in front. Next were Chanden Sing, the Brahmin, and the two Christians. The carriers were behind. When the Magbun had gone, I turned round to look at my followers. What a sight! They one and all were crying, each man hiding his face in his hands. Kachi had tears streaming down his cheeks, Dola was sobbing, while the brigand and the other Tibetan in my employ, who had for the occasion assumed a disguise, were hiding behind their loads. Serious though the situation was, I could not help laughing at the fright of my men.

We pitched our tents. I had been sitting inside, noting the [45] observations which I had taken with my instruments and writing up my diary, when Kachi crept in, apparently in great distress. He seemed so upset that he could hardly speak.

"Master!" he whispered. "Master! The Tibetans have sent a man to your coolies threatening to kill them if they remain faithful to you. They must abandon you during the night. If you attempt to hold them they have orders to kill you."

At the same time that this agent had been sent to conspire with my coolies, other envoys of the Magbun brought into my camp masses of dry dung to make our fires. These men conveyed to me again the Magbun's renewed declarations of friendship. Nevertheless, soldiers were sent in every direction by the Tibetan official to call for help. I saw them start. One messenger went toward Kardam and Taklakot, a second proceeded in the direction of Barca, a third galloped to the west.

My carriers were evidently preparing to leave me. I watched them, unseen, through an opening in the tent. They were busily engaged separating their blankets and clothes from my loads, dividing the provisions among themselves, and throwing aside my goods. I went out to them, patiently made them repack the things, and warned them that I would shoot any one who attempted to revolt or desert.

While the doctor and I sat down to a hearty meal, Chanden Sing was intrusted with the preparations for war on our side. He cleaned the rifles with much care, and got the ammunition ready. He was longing to [46] fight. The Brahmin, on whose faithfulness we could also rely, remained cool and collected through the whole affair. He was a philosopher, and never worried over anything. He took no active part in preparing for our defence, for he did not fear death. God alone could kill him, he argued, and all the matchlocks in the country together could not send a bullet through him unless God wished it. And if it be God's decree that he should die, what would be the use of rebelling against it? The two converts, like good Christians, were more practical, and lost no time in grinding the huge blades of their kukris, in order to make them as sharp as razors.

When darkness came I placed a guard a little distance off our camp. It seemed likely that the Tibetans might make a rush on our tent if they had a chance. One of us kept watch all night outside the tent, while those inside lay down in their clothes, with loaded rifles by their side. I cannot say that either Dr. Wilson or I felt very uneasy, for the Tibetan soldiers, with their clumsy matchlocks, long spears, and jewelled swords and daggers, were more picturesque than dangerous.

[1] A kind of ox with long hair.

[2] Old muskets fired by a fusee, with a prong to rest the barrel on.

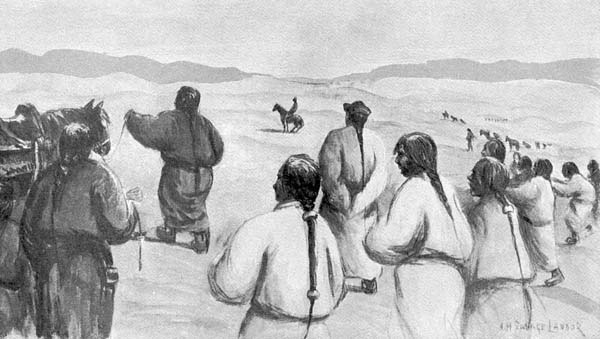

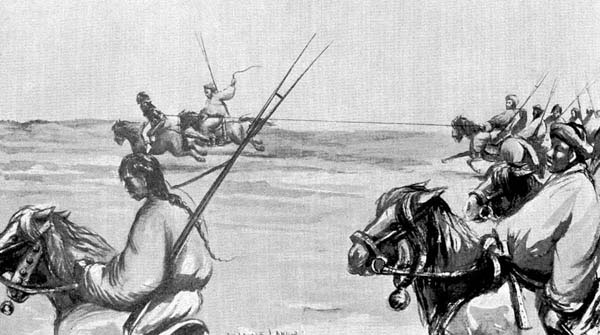

Early the next morning we were roused by the distant sound of tinkling horse-bells. On looking out of the tent I saw a long row of pack-ponies heavily laden, escorted by a number of mounted soldiers with matchlocks and spears. It was evident that some high official was coming. This advance-guard consisted of his inferior officers and baggage. They took a long sweep far away from our tent, and dismounted at the Gyanema fort. Other soldiers and messengers were constantly arriving in groups from all directions. The leader of one party, with a large escort of soldiers, was received with profuse salaams. I concluded that he must be an important person.

After some time a message was sent to us that this new-comer, the Barca Tarjum, wished to have the honor of seeing us. His rank might be described as that of a feudal prince. We replied that we were having our breakfast, and that we would send for him when we wished to speak to him. Our experience had taught us that it was better to treat Tibetan officials as inferiors, as they were then more subdued and easier to deal with. At eleven, we sent a messenger to the fort, to say we should be pleased to receive the Tarjum. He came immediately with a large [48] following. He was a picturesque figure dressed in a long coat of green silk of Chinese shape, with large sleeves turned up, showing his arms up to the elbow. He had a cap similar to those worn by Chinese officials, and he was shod in heavy, long black boots, with large nails under the soles. His long, pale, angular face was remarkable in many ways. It was dignified and full of repose. Though somewhat weak, his features were rather fine. Long hair fell in loose curls down to his shoulders. Hanging from his left ear was a large ear-ring, with malachite ornaments and a pendant. In his nervous fingers he held a small roll of Tibetan material, which he used with both hands as a handkerchief. He blew his nose inconsequently every time he was at a loss to answer a question. The Tarjum and his men were profuse in their bows, and there was, as usual, a great display of tongues.

We had rugs placed outside our principal tent. The doctor and I sat on one, asking the Tarjum to sit on the one facing us. His followers squatted around him. It is a well-known fact that in Tibet, if you are a "somebody," or if you wish people to recognize your importance, you must have an umbrella spread over your head. Fortunately the ever-prudent doctor had two, and these were duly spread over our respective heads. The Tarjum himself was shaded under a parasol of colossal dimensions, held in position by his secretary.

In spite of the extravagant terms of friendship which fell from the Tarjum's lips, I was convinced, by studying the man's face, that his words were insincere, and that it would be unsafe to trust him. He [49] never looked us straight in the face. His eyes were fixed on the ground all the time, and he spoke in an unpleasantly affected manner. I did not like the man from the very first, and, friend or no friend, I kept my loaded rifle on my lap.

After long, heavy speeches, clumsy compliments, and tender inquiries on the state of health of all relatives they could possibly think of, after repeated blowing of the nose and loud coughing, which always came on when we asked whether they had yet decided what we should be allowed to do, at last, when my patience was nearly exhausted, our negotiations of the previous day were reopened. We argued for hours. We asked to be allowed to go on. They were still uncertain whether they would let us or not. To simplify matters, and hasten their decision before other reinforcements arrived, the doctor applied for permission to let only eight of us proceed to Mansarowar. He (the doctor) himself would remain at Gyanema with the rest of the party, as a proof of good faith. Even this offer they rejected, not directly, but with hypocritical excuses and delays. They thought we could not find our way, and that if we did we should find it rough and the climate too severe; that brigands might attack us, and so on. All this was tiresome. The Tibetans were even getting unpleasant. I decided to bring matters to a crisis.

Still holding the rifle cocked at safety on my lap, I turned the muzzle of it toward the Tarjum, and purposely let my hand slide down to the trigger. He became uncomfortable. His face showed signs of apprehension.

[50] His eyes, until now fixed on the ground, became first unsteady, and then settled fixedly, with a look of distress, on the muzzle of my rifle. He tried to dodge the aim, right or left, by moving his head. I made the weapon follow his movements. The Tarjum's servants fully shared their master's fear. Without doubt the poor fellow was in agony; his tone of voice, a moment before loud and insulting, now became very humble. With much meekness he expressed himself ready to please us in every way.

"I see that you are good people," said he, in a faint whisper accompanied by a deep bow. "I cannot give, as I should like, my official approval to your journey forward, but you can go if you wish. I cannot say more. Eight of you can proceed to the sacred Mansarowar Lake. The others will remain here."

Before giving his final decision, he said that he would prefer to have another consultation with his officers.

We granted this readily.

The Tarjum then presented the doctor with a roll of Tibetan cloth.

I had bathed in the morning, and my Turkish towel was spread outside the tent to dry. The Tarjum, who showed great interest in all our things, took a particular fancy to its knotty fabric. He sent for his child to see this wonderful material, and when he arrived the towel was placed on the youth's back as if it were a shawl. I at once offered it to him as a present if he would accept it. There were no bounds to his delight, and our relations, somewhat strained a few minutes earlier, became now of [51] the friendliest character. We invited the party inside our tent, and they examined everything with curiosity, asking endless questions. They were now quite pleasant, and even amusing. Tibetans have a craving for alcohol. They soon asked if I had any to give them; there was nothing they would like more. As I never carry intoxicants, I could not offer whiskey, wine, or beer; but, not wishing to disappoint them, I produced a bottle of methylated spirit[3] (which I used as fuel in my hypsometrical[4] apparatus). This they readily drank, apparently liking its throat-burning-qualities. They even asked for more. The Tarjum complained of an ailment from which he had suffered for some time. The doctor was able to give him a suitable remedy. All officers received small presents. Then they departed.

In the afternoon a messenger came from the Barca Tarjum. He had good news for us. The Tarjum wished us to understand that, "as we had been so kind to him and his followers, he regarded us as his personal friends. As we were so anxious to visit the Mansarowar Lake and the great Kelas Mount, and had already experienced many difficulties and great expense in coming so far, he agreed that eight of our party should proceed to these sacred places. It was impossible for him to give an official consent, but he repeated again that we could go if we wished."

This news naturally delighted me. Once at Kelas, I felt sure I could easily go further.

On the same evening a traitor in our camp sneaked from under the tent in [52] which my men were sleeping and paid a visit to the Tarjum. There is no doubt that he told him I was not the doctor's brother nor a Hindoo pilgrim. He disclosed that I was a sahib, and that I was on my way to Lhassa. From what I heard afterward, it seemed that the Tarjum did not quite believe his informant; but, fresh doubts arising in his mind, he sent a message in the night, entreating us to return the way we had come.

"If there is really a sahib in your party, whom you have kept concealed from me, and I let you go on, my head will be cut off by the Lhassa officials. You are now my friends, and you will not allow this."

"Tell the Tarjum," I replied to the messenger, "that he is my friend, and I will treat him as a friend."

In the morning we found thirty horsemen, fully armed, posted about one hundred yards from our tent. To go ahead with my frightened men and be followed by this company would certainly bring trouble. It was better to adopt other tactics.