The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Iron Pirate, by Max Pemberton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Iron Pirate

A Plain Tale of Strange Happenings on the Sea

Author: Max Pemberton

Release Date: September 3, 2008 [EBook #26514]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE IRON PIRATE ***

Produced by Robert Cicconetti and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

UNIFORM WITH THIS WORK.

Kronstadt. By Max Pemberton.

Other Works by the same Author.

Red Morn.

The Giant's Gate.

The Garden of Swords.

A Puritan's Wife.

The Sea Wolves.

The Impregnable City.

The Little Huguenot.

CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited.

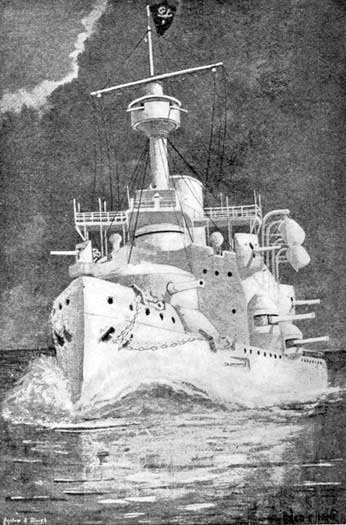

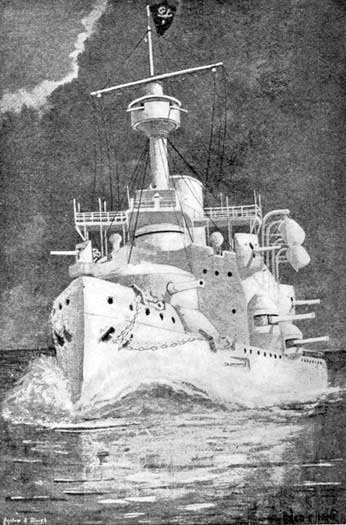

THE IRON PIRATE (p. 124).

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Perfect Fool asks a Favour | 1 |

| II. | I Meet Captain Black | 13 |

| III. | "Four-Eyes" delivers a Message | 31 |

| IV. | A Strange Sight on the Sea | 43 |

| V. | The Writing of Martin Hall | 59 |

| VI. | I Engage a Second Mate | 92 |

| VII. | The Beginning of the Great Pursuit | 101 |

| VIII. | I Dream of Paolo | 114 |

| IX. | I Fall in with the Nameless Ship | 123 |

| X. | The Spread of the Terror | 140 |

| XI. | The Ship in the Black Cloak | 153 |

| XII. | The Drinking Hole in the Bowery | 166 |

| XIII. | Astern of the "Labrador" | 180 |

| XIV. | A Cabin in Scarlet | 193 |

| XV. | The Prison of Steel | 198 |

| XVI. | Northward Ho! | 205 |

| XVII. | One Shall Live | 218 |

| XVIII. | The Den of Death | 228 |

| XIX. | The Murders in the Cove | 239 |

| XX. | I Quit Ice-Haven | 262 |

| XXI. | To the Land of Man | 274 |

| XXII. | The Robbery of the "Bellonic" | 285 |

| XXIII. | I Go to London | 298 |

| XXIV. | The Shadow on the Sea | 308 |

| XXV. | The Dumb Man Speaks | 329 |

| XXVI. | A Page in Black's Life | 345 |

| XXVII. | I Fall to Wondering | 371 |

THE IRON PIRATE.

CHAPTER I.

THE PERFECT FOOL ASKS A FAVOUR.

"En voiture! en voiture!"

If it has not been your privilege to hear a French guard utter these words, you have lost a lesson in the dignity of elocution which nothing can replace. "En voiture, en voiture; five minutes for Paris." At the well-delivered warning, the Englishman in the adjoining buffet raises on high the frothing tankard, and vaunts before the world his capacity for deep draughts and long; the fair American spills her coffee and looks an exclamation; the Bishop pays for his daughter's tea, drops the change in the one chink which the buffet boards disclose, and thinks one; the travelled person, disdaining haste, smiles on all with a pitying leer; the foolish man, who has forgotten something, makes public his conviction that he will lose his train. The adamantine official alone is at his ease, and, as the minutes go, the knell of the train-loser sounds the deeper, the horrid jargon is yet more irritating.

I thought all these things, and more, as I waited for the Perfect Fool at the door of my carriage in the harbour station at Calais. He was truly an impossible man, that small-eyed, short-haired, stooping mystery I had met at Cowes a month before, and formed so strange a friendship with. To-day he would do this, to-morrow he would not; to-day he had a theory that the world was egg-shaped, to-morrow he believed it to be round; in one moment he was hot upon a journey to St. Petersburg, in the next he felt that the Pacific Islands offered a better opportunity. If he had a second coat, no man had ever seen it; if he had a purpose in life, no man, I hold, had ever known it. And yet there was a fascination about him you could not resist; in his visible, palpitating, stultifying folly there was something so amazing that you drew to the man as to that unknown something which the world had not yet given to you, as a treasure to be worn daily in the privacy of your own enjoyment. I had, as I have said, picked the Perfect Fool up at Cowes, whither I had taken my yacht, Celsis, for the Regatta Week; and he had clung to me ever since with a dogged obstinacy that was a triumph. He had taken of my bread and eaten of my salt unasked; he was not a man such as the men I knew—he was interested in nothing, not even in himself—and yet I tolerated him. And in return for this toleration he was about to make me lose a train for Paris.

"Will you come on?" I roared for the tenth time, as the cracked bell jangled and the guards hoisted the last stout person into the only carriage where there was not a seat for her. "Don't you see we shall be left behind? Hurry up! Hang your parcels! Now then—for the last time, Hall, Hill, Hull, whatever your confounded name is, are you coming?"

Many guards gave a hand to the hoist, and the Perfect Fool fell upon his hat-box, which was all the personal property he seemed to possess. He apologised to Mary, who sat in the far corner, with more grace than I had looked for from him, woke Roderick, who was in his fifth sleep since luncheon, and then gathered the remnants of himself into a coherent whole.

"Did anyone use my name?" he asked gravely, and as one offended. "I thought I heard someone call me Hull?"

"Exactly; I think I called you every name in the Directory, but I'm glad you answer to one of them."

"Yes, and I tell you what," said Roderick, "I wish you wouldn't come into a railway carriage on your hands and knees, waking a fellow up every time he tries to get a minute to himself; I don't speak for myself, but for my sister."

The Perfect Fool made a profound bow to Mary, who looked very pretty in her dainty yachting dress—she was only sixteen, I had known her all her life—and he said, "I cannot make your sister an apology worthy of her."

"If that isn't a shame, Mr. Hall," replied the blushing girl. "I never go to sleep in railway carriages."

"No, of course you don't," said Roderick, as he made himself comfortable for another nap, "but you may go to sleep in a railway carriage;" then with a grunt, "Wake me up at Amiens, old man," he sank to slumber.

The train moved slowly over the sandy marsh which lies between Calais and Boulogne, and the vapid talk of the railway carriage held us to Amiens, and after. During the second half of the long journey Roderick was asleep, and Mary's pretty head had fallen against the cushion as the swing of the carriage gave the direct negative to her words at Calais station. At last, even the maker of commonplaces was silent; and as I reclined at greater length on the cushions of the stuffy compartment, I thought how strange a company we were then being carried over the dull, drear pasture-land of France, to the lights, the music, and the life of the great capital. Of the man Martin Hall—I remembered his true name in the moments of repose—I knew nothing beyond that which I have told you; but of my friends Roderick and Mary, accompanying me on this wildaway journey, I knew all that was to be known. Roderick and I had been at Caius College, Cambridge, together, friends drawn the closer in affection because our conditions in kith and kin, in possession and in purpose, in ambition and in idleness, were so very like. Roderick was an orphan twenty-four years of age, young, rich, desiring to know life before he measured strength with her, caring for no man, not vital enough to realise danger, an Englishman in tenacity of will, a good fellow, a gentleman. His sister was his only care. He gave to her the strength of an undivided love, and just as, in the shallowness of much of his life, there was matter for blame, so in this increasing affection and thought for the one very dear to him was there the strength of a strong manhood and a noble work.

For myself, I was twenty-five when the strange things of which I am about to write happened to me. Like Roderick, I was an orphan. My father had left me £50,000, which I drew upon when I was of age; but, shame that I should write it, I had spent more than £40,000 in four years, and my schooner, the Celsis, with some few thousand pounds, alone remained to me. Of what was my future to be, I knew not. In the senseless purpose of my life, I said only, "It will come, the tide in my affairs which taken at the flood should lead on to fortune." And in this supreme folly I lived the days, now in the Mediterranean, now cruising round the coast of England, now flying of a sudden to Paris with one they might have called a vulgarian, but one I chose to know. A journey fraught with folly, the child of folly, to end in folly, so might it have been said; but who can foretell the supreme moments of our lives, when unknowingly we stand on the threshold of action? And who should expect me to foresee that the man who was to touch the spring of my life's action sat before me—mocked of me, dubbed the Perfect Fool—over whose dead body I was to tread the paths of danger and the intricate ways of strange adventure?

But I would not weary you with more of these facts than are absolutely necessary for the understanding of this story, surpassing strange, which I judge it to be as much my duty as my privilege to write. Let us go back to the Gare du Nord, and the compartment wherein Mary and Roderick slept, while the Perfect Fool and I faced each other, surfeited with meteorological observations, sick to weariness with reflections upon the probability of being late or arriving before time. I would well have been silent and dozed as the others were doing; of a truth, I had done so had it not become very evident that the man who had begun to bore me wished at last to say something, relating neither to the weather nor to the speed of our train. His restless manner, the fidgeting of his hands with certain papers which he had taken from his great-coat pocket, the shifting of the small grey eyes, marked that within him which suffered not show except in privacy; and I waited for him, making pretence of interest in the great plain of hedgeless pasture-land which bordered the track on each side. At last he spoke, and, speaking, seemed to be the Perfect Fool no longer.

"They're both asleep, aren't they?" he asked suddenly, as he put his hand, which seemed to tremble, upon my arm, and pointed to the sleepers. "Would you mind making sure—quite sure—before I speak?—that is, if you will let me, for I have a favour to ask."

To see the man grave and evidently concerned was to me so unusual that for a moment I looked at him rather than at Roderick or Mary, and waited to know if the gravity were not of his humour and not of any deeper import. A single glance at him convinced me for the second time that I did him wrong. He was looking at me with a fitful pleading look unlike anything he had shown previously. In answer to his request I assured him at once that he might speak his mind; that, even if Roderick should overhear us, I would pledge my word for his good faith. Then only did he unbosom himself and tell me freely what he had to say.

"I wanted to speak to you some days ago," he said earnestly and quickly, as his hands continued to play with the paper, "but we have been so much occupied that I have never found the occasion. It must seem curious in your eyes that I, who am quite a stranger to you, should have been in your company for some weeks, and should not have told you more than my name. As the thing stands, you have been kind enough to make no inquiries; if I am an impostor, you do not care to know it; if I am a rascal hunted by the law, you have not been willing to help the law; you do not know if I have money or no money, a home or no home, people or no people, yet you have made me—shall I say, a friend?"

He asked the question with such a gentle inflexion of the voice that I felt a softer chord was touched, and in response I shook hands with him. After that he continued to speak.

"I am very grateful for all your trust, believe me, for I am a man that has known few friends in life, and I have not cared to go out of my way to seek them. You have given me your friendship unasked, and it is the more prized. What I wanted to say is this, if I should die before three days have passed, will you open this packet of papers I have prepared and sealed for you, and carry out what is written there as well as you are able? It is no idle request, I assure you; it is one that will put you in the place where I now stand, with opportunities greater than I dare to think of. As for the dangers, they are big enough, but you are the man to overcome them as I hope to overcome them—if I live!"

The sun fell over the lifeless scene without as he ceased to speak. I could see a crimson beam glowing upon a crucifix that stood on the wayside by the hill-foot yonder; but the cheerless monotony of plough land and of pasture, stretching away leafless, treeless, without bud or flower, herd or herdsman, church or cottage, to the shadowed horizon, looming dark as the twilight deepened, was in sympathy with the gloom which had come upon me as Martin Hall ceased to speak. I had thought the man a fool and witless, flighty in purpose and shallow in thought, and yet he seemed to speak of great mysteries—and of death. In one moment the jester's cloak fell from him, and I saw the mail beneath. He had made a great impression upon me, but I concealed it from him, and replied jauntily and with no show of gravity—

"Tell me, are you quite certain that you are not talking nonsense?"

He replied by asking me to take his hand. I took it—it was chill with the icy cold as of death; and I doubted his meaning no more, but determined to have the whole mystery, then so faintly sketched, laid bare before me.

"If you are not playing the fool, Hall," said I, "and if you are sincere in wishing me to do something which you say is a favour to you, you must be more explicit. In the first place, how did you get this absurd notion that you are going to die into your head? Secondly, what is the nature of the obligation you wish to put upon me? It is quite clear that I can't accept a trust about which I know nothing, and I think that for undiluted vagueness your words deserve a medal. Let us begin at the beginning, which is a very good place to begin at. Now, why should you, who are going to Paris, as far as I know, simply as a common sightseer, have any reason to fear some mysterious calamity in a city where you don't know a soul?"

He laughed softly, looking out for a moment on the sunless fields, but his eyes flashed lights when he answered me, and I saw that he clenched his hands so that the nails pierced the flesh.

"Why am I going to Paris without aim, do you say? Without aim—I, who have waited years for the work I believe that I shall accomplish to-night—why am I going to Paris? Ha! I will tell you: I am going to Paris to meet one who, before another year has gone, will be wanted by every Government in Europe; who, if I do not put my hand upon his throat in the midst of his foul work, will make graves as thick as pines in the wood there before you know another month; one who is mad and who is sane, one who, if he knew my purpose, would crush me as I crush this paper; one who has everything that life can give and seeks more, a man who has set his face against humanity, and who will make war on the nations, who has money and men, who can command and be obeyed in ten cities, against whom the police might as well hope to fight as against the white wall of the South Sea; a man of purpose so deadly that the wisest in crime would not think of it—a man, in short, who is the product of culminating vice—him I am going to meet in this Paris where I go without aim—without aim, ha!"

"And you mean to run him down?" I asked, as his voice sank to a hoarse whisper, and the drops stood as beads on his brow; "what interest have you in him?"

"At the moment none; but in a month the interest of money. As sure as you and I talk of it now, there will be fifty thousand pounds offered for knowledge of him before December comes upon us!"

I looked at him as at one who dreams dreams, but he did not flinch.

"You meet the man in Paris?" I went on.

"To-night I shall be with him," he answered; "within three days I win all or lose all: for his secret will be mine. If I fail, it is for you to follow up the thread which I have unravelled by three years' hard work——"

"What sort of person do you say he is?" I continued, and he replied—

"You shall see for yourself. Dare you risk coming with me—I meet him at eight o'clock?"

"Dare I risk!—pooh, there can't be much danger."

"There is every danger!—but, so, the girl is waking!"

It was true; Mary looked up suddenly as we thundered past the fortifications of Paris, and said, as people do say in such circumstances, "Why, I believe I've been asleep!" Roderick shook himself like a great bear, and asked if we had passed Chantilly; the Perfect Fool began his banter, and roared for a cab as the lights of the station twinkled in the semi-darkness. I could scarce believe, as I watched his antics, that he was the man who had spoken to me of great mysteries ten minutes before. Still less could I convince myself that he had not many days to live. So are the fateful things of life hidden from us.

CHAPTER II.

I MEET CAPTAIN BLACK.

The lights of Paris were very bright as we drove down the Boulevard des Capucines, and drew up at length at the Hôtel Scribe, which is by the Opera House. Mary uttered a hundred exclamations of joy as we passed through the city of lights; and Roderick, who loved Paris, condescended to keep awake!

"I'll tell you what," he exclaimed, after a period of profound reflection, "the beauty of this place is that no one thinks here, except about cooking, and, after all, cooking is one of the first things worthy of serious speculation, isn't it? Suppose we plan a nice little dinner for four?"

"For two, my dear fellow, if you please," said Hall, with mock of state—he was quite the Perfect Fool again. "Mr. Mark Strong condescends to dine with me, and in that utter unselfishness of character peculiar to him insists on paying the bill—don't you, Mr. Mark?"

I answered that I did, and, be it known, I was the Mark Strong referred to.

"The fact is, Roderick," I explained, "that I made a promise to meet one of Mr. Hall's friends to-night, so you and Mary must dine alone. You can then go to sleep, don't you see, or take Mary out and buy her something."

"Yes, that would be splendid, Roderick," cried Mary, all the girlish excitement born of Paris strong upon her. "Let's go and buy a hundred things"—Roderick groaned—"but I wish, Mark, you weren't going to leave us on our first night here; you know what you said only yesterday!"

"What did I say yesterday?"

"That there were a lot of bounders in Paris—and I want to see them bound!"

I consoled her by telling her that bounders never made display after six o'clock, and assured her that Roderick had long confessed to me his intention to buy her the best hat in Paris, at which Roderick muttered exclamations for my ear only. By that time we were at the hotel, and the Perfect Fool had much to say.

"Could any gentleman oblige me with the time, English or French?" he asked; "my watch is so moved at the situation in which it finds itself that it is fourteen hours too slow."

I told him that it was ten minutes to eight, and the information quickened him.

"Ten minutes to eight, and half-a-dozen Russian princes, to say nothing of an English knight, to meet; so ho, my toilet must remain! Could anyone oblige me with a comb, fragmentary or whole?"

He continued his banter as we mounted the stairs of the cozy little hotel, whose windows overlook the core of the great throbbing heart of Paris, and so until we were alone in my room, whither he had followed me.

"Quick's the word," he said, as he shut the door, and took several articles from his hat-box, "and no more palaver. One pair of spectacles, one wig, one set of curiosities to sell—do I look like a second-hand dealer in odd lots, or do I not, Mr. Mark Strong?"

I had never seen such an utter change in any man made with such little show. The Perfect Fool was no longer before me; there was in his place a lounging, shady-looking, greed-haunted Hebrew. The haunching of the shoulders was perfect; the stoop, the walk, were triumphs. But he gave me little opportunity to inspect him or to ask for what reason he had thus disguised himself.

"It's five minutes from here," he said, "and the clocks are going eight—you are right as you are, for you are a cipher in the affair yet, and don't run the danger I run—now come!"

He passed down the stairs with this blunt invitation, and I followed him. So good was his disguise and make-pretence that the others, who were in the narrow hall, drew back, to let him go, not recognising him, and spoke to me, asking what I had done with him. Then I pointed to the new Perfect Fool, and without another word of explanation went on into the street.

We walked in silence for some little distance, keeping by the Opera, and so through to the broad Boulevard Haussmann. Thence he turned, crossing the busy thoroughfare, and passing through the Rue Joubert, stopped quite suddenly at last in the mouth of a cul-de-sac which opened from the narrow street. He had something to say to me, and he gave it with quick words prompted by a quick and serious wit, for he had put off the rôle of the jester at the hotel.

"This is the place," he said; "up here on the third, and there isn't much time for talk. Just this; you're my man, you carry this box of metal"—he meant the case of curiosities—"and don't open your mouth, unless you get the fool in you and want the taste of a six-inch knife. That's my risk, and I haven't brought you here to share it; so mum's the word, mum, mum, mum; and keep a hold on your eyes, whatever you see or whatever you hear. Do I look all right?"

"Perfectly—but just a word; if we are going into some den where we may have a difficulty in getting out again, wouldn't it be as well to go armed?"

"Armed!—pish!"—and he looked unutterable contempt, treading the passage with long strides, and entering a house at the far end of it.

Thither I followed him, still wondering, and passing the concierge found myself at last on the third floor, before a door of thick oak. Our first knocking upon this had no effect, but at the second attempt, and while he was pulling his hat yet more upon his eyes, I heard a great rolling voice which seemed to echo on the stairway, and so leapt from flight to flight, almost like the rattle of a cannon-shot with its many reverberations. For the moment indistinct, I then became aware that the voice was that of a man singing and walking at the same time, and seemingly in no hurry to give us admission, for he passed from room to room bellowing this refrain, and never varying it by so much as a single word:—

"There was a man of Boston town,

With his pistols three,

With his pistols three, three, three;

And never a skunk in Boston town

That he didn't chaw but me!"

When the noise stopped at last, there was silence, complete and unbroken, for at least five minutes, during which time Hall stood motionless, waiting for the door to be opened. After that we heard a great yell from the same voice, with the words, "Ahoy, Splinters, shift along the gear, will you?" and then Splinters, whoever he might be, was cursed in unchosen phrases as the son of all the lubbers that ever crowded a fo'cas'le. A mumbled discussion seemed to tread on the heels of the hullabaloo, when, apparently having arranged the "gear" to satisfaction, the man stalked to the door, singing once more in stentorian tones:

"There was a man of Boston town,

With his pistols three,

With his pistols——"

"Hullo—the darned little Jew and his kick-shaws; why, matey, so early in the morning?"

The exclamation came as he saw us, putting his head round the door, and showing one arm swathed all up in dirty red flannel. He was no sort of a man to look at, as the Scots say, for his head was a mass of dirty yellow hair, and his face did not seem to have known an ablution for a week. But there was an ugly jocular look about his rabbit-like eyes and a great mark cut clean into the side of his face which were a fit decoration for the red-burnt, pitted, and horribly repulsive countenance he betrayed. His leer, too, as he greeted Hall, was the evil leer of a man whose laugh makes those hearing hush with the horror of it; and, on my part, forgetting the warning, I looked at him and drew back repelled. This he saw, and with a flush and a display of one great stump of a tooth which protruded on his left lip, he turned on me.

"And who may you be, matey, that you don't go for to shake hands with Roaring John? Dip me in brine, if you was my son I'd dress you down with a two-foot bar. Why don't you teach the little Hebrew manners, old Josfos? but there," and this he said as he opened the door wider, "so long as our skipper will have to do with shiners to sell and land barnacles, what ken you look for?—walk right along here."

The room indicated opened from a small hall, for the place was built after the Parisian fashion—akin to that of our flats—and was a house in itself. The man who called himself "Roaring John" entered the apartment before us, bawling at the top of his voice, "Josfos, the Jew, and his pardner come aboard!" and then I found myself in the strangest company and the strangest place I have ever set eyes on. So soon as I could see things clearly through the hanging atmosphere of tobacco smoke and heavy vapour, I made out the forms of six or eight men, not sitting as men usually do in a place where they eat, but squatting on their haunches by a series of low narrow tables, which were, on closer inspection, nothing but planks put upon bricks and laid round the four sides of the apartment. Of other furniture there did not seem to be a vestige in the place, save such as pertained to the necessities of eating and sleeping. Each man lolled back on his own pile of dirty pillows and dirtier blankets; each had before him a great metal drinking-cup, a coarse knife, which I found was for hacking meat, long rolls of plug tobacco, and a small red bundle, which I doubt not was his portable property. Each, too, was dressed exactly as his fellow, in a coarse red shirt, seamen's trousers of ample blue serge, a belt with a clasp-knife about his waist, and each had some bauble of a bracelet on his arm, and some strange rings upon his fingers. In the first amazement at seeing such an assembly in the heart of civilised Paris, I did no more than glean a general impression, but that was a powerful one—the impression that I saw men of all ages from twenty-five years upwards; men marked by time as with long service on the sea; men scarred, burnt, some with traces of great cuts and slashes received on the open face; men fierce-looking as painted devils, with teeth, with none, with four fingers to the hand, with three; men whose laugh was a horrid growl like the tumult of imprisoned passions, whose threats chilled the heart to hear, whose very words seemed to poison the air, who made the great room like a cage of beasts, ravenous and ill-seeking. This and more was my first thought, as I asked myself, into what hovel of vice have I fallen, by what mischance have I come on such a company?

Martin Hall seemed to have no such ill opinion of the men, and put himself at his ease the moment we entered. I had, indeed, believed for the moment that he had brought me there with evil intent, distrusting the man who was yet little more than a stranger to me; but recalling all that passed, his disguise, his evident fear, I put the suspicion from me, and listened to him, more content, as he made his way to the top of the room and stood before one who forced from me individual notice, so strange-looking was he, and so deep did the respect which all paid him appear to be. We shall meet this man often in our travels together, you and I, my friends, so a few words, if you please, about him. He sat at the head of the rude table, as I have said, but not as the others sat, on pillows and blankets, for there was a pile of rich-looking skins—bear, tiger, and white wolf—beneath him, and he alone of all the company wore black clothes and a white shirt. He was a short man, I judged, black-bearded and smooth-skinned, with a big nose, almost an intellectual forehead, small, white-looking hands, all ablaze with diamonds, about whose fine quality there could not be two opinions; and, what was even more remarkable, there hung as a pendant to his watch-chain a great uncut ruby which must have been worth five thousand pounds. One trade-mark of the sea alone did he possess, in the dark, curly ringlets which fell to his shoulders, matted there as long uncombed, but typical in all of the man. This then was the fellow upon whose every word that company of ruffians appeared to hang, who obeyed him, as I observed presently, when he did so much as lift his hand, who seemed to have in their uncouth way a veneration for him, inexplicable, remarkable—the man of whom Martin Hall had painted such a fantastic picture, who was, as I had been told, soon to be wanted by every Government in Europe. And so I faced him for the first time, little thinking that before many months had gone I should know of deeds by his hand which had set the world aflame with indignation, deeds which carried me to strange places, and among dangers so terrible that I shudder when the record brings back their reality.

Hall was the first to speak, and it was evident to me that he cloaked his own voice, putting on the nasal twang and the manner of an East-end Jew dealer.

"I have come, Mister Black," he said, "as you was good enough to wish, with a few little things—beautiful things—which cost me moosh money——"

"Ho, ho!" sang out Captain Black, "here is a Jew who paid much money for a few little things! Look at him, boys!—the Jew with much money! Turn out his pockets, boys!—the Jew with much money! Ho, ho! Bring the Jew some drink, and the little Jew, by thunder!"

His merriment set all the company roaring to his mood. For a moment their play was far from innocent, for one lighted a great sheet of paper and burnt it under the nose of my friend, while another pushed his dirty drinking-pot to my mouth, and would have forced me to drink. But I remembered Hall's words, and held still, giving banter for banter—only this, I learnt to my intense surprise that the pot did not contain beer but champagne, and that, by its bouquet, of an infinitely fine quality. In what sort of a company was I, then, where mere seamen wore diamond rings and drank fine champagne from pewter pots?

The unpleasant and rough banter ceased on a word from Captain Black, who called for lights, which were brought—rough, ready-made oil flares, stuck in jugs and pots—and Hall gathered up his trinkets and proceeded to lay them out with the well-simulated cunning of the trader.

"That, Mister Black," he said, putting a miniature of exquisite finish against the white fur on the floor, "is a portrait of the Emperor Napoleon, sometime in the possession of the Empress Josephine; that is a gold chain—he was eighteen carat—once the property of Don Carlos; here is the pen with which Francis Drake wrote his last letter to the Queen Elizabeth—beautiful goods as ever was, and cost moosh money!"

"To the dead with your much money," said the Captain with an angry gesture, as he snatched the trinkets from him, and eyed them to my vast surprise with the air of a practised connoisseur; "let's handle the stuff, and don't gibber. How much for this?" He held up the miniature, and admiration betrayed itself in his eyes.

"He was painted by Sir William Ross, and I sell him for two hundred pounds, my Captain. Not a penny less, or I'm a ruined man!"

"The Jew a ruined man! Hark at him! Four-Eyes"—this to a great lanky fellow who lay asleep in the corner—"the little Jew can't sell 'em under two hundred, I reckon; oh, certainly not; why, of course. Here, you, Splinters, pay him for a thick-skinned, thieving shark, and give him a hundred for the others."

The boy Splinters, who was a black lad, seemingly about twelve years old, came up at the word, and took a great canvas bag from a hook on the wall. He counted three hundred gold pieces on the floor—pieces of all coinages in Europe and America, as they appeared to be by their faces, and Hall, who had squatted like the others, picked them up. Then he asked a question, while the little black lad, who bore a look of suffering on his worn face, stood waiting the Captain's word.

"Mister Captain, I shall have waiting for me at Plymouth to-morrow a relic of the great John Hawkins, which, as I'm alive, you shouldn't miss. I have heard them say that it is the very sword with which he cut the Spaniards' beards. Since you have told me that you sail to-morrow, I have thought, if you put me on your ship across to Plymouth, I could show you the goods, and you shall have them cheap—beautiful goods, if I lose by them."

Now, instead of answering this appeal as he had done the others, with his great guffaw and banter, Captain Black turned upon Hall as he made his request, and his face lit up with passion. I saw that his eyes gave one fiery look, while he clenched his fists as though to strike the man as he sat, but then he restrained himself. Yet, had I been Hall, I would not have faced such another glance for all that adventure had given me. It was a look which meant ill—all the ill that one man could mean to another.

"You want to come aboard my boat, do you?" drawled the Captain, as he softened his voice to a fine tone of sarcasm. "The dealer wants a cheap passage; so ho! what do you say, Four-Eyes; shall we take the man aboard?"

Four-Eyes sat up deliberately, and struck himself on the chest several times as though to knock the sleep out of him. He seemed to be a brawny, thick-set Irishman, gigantic in limb, and with a more honest countenance than his fellows. He wore a short pea-jacket over the dirty red shirt, and a great pair of carpet slippers in place of the sea-boots which many of the others displayed. His hair was light and curly, and his eyes, keen-looking and large, were of a grey-blue and not unkindly-looking. I thought him a man of some deliberation, for he stared at the Captain and at Hall before he answered the question put to him, and then he drank a full and satisfying draught from the cup before him. When he did give reply, it was in a rich rolling voice, a luxurious voice which would have given ornament to the veriest common-place.

"Oi'd take him aboard, bedad," he shouted, leaning back as though he had spoken wisdom, and then he nodded to the Captain, and the Captain nodded to him.

The understanding seemed complete.

"We sail at midnight, tide serving," said the Captain, as he picked up the miniature and the other things; "you can come aboard when you like—here, boy, lock these in the chest."

The boy put out his hand to take the things, but in his fear or his clumsiness, he dropped the miniature, and it cracked upon the floor. The mishap gave me my first real opportunity of judging these men in the depth of their ruffianism. As the lad stood quivering and terror-struck, Black turned upon him, almost foaming at the lips.

"You clumsy young cub, what d'ye mean by that?" he asked; and then, as the boy fell on his knees to beg for mercy, casting one pitiful look towards me—a look I shall not soon forget—he kicked him with his foot, crying—

"Here, give him a dozen with your strap, one of you."

He had but to say the words, when a colossal brute seized the boy in his grip, and held his head down to the table board, while another, no more gentle, stripped his shirt off, and struck him blow after blow with the great buckle, so that the flesh was torn while the blood trickled upon the floor. The brutal act stirred the others to a fine merriment, yet for myself, I had all the will to spring up and grip the striker as he stood, but Hall, who had covered my hand with his, held it so surely, and with such prodigious strength, that my fingers almost cracked. It was the true sign-manual for me to say nothing, and I realised how hopeless such a struggle would be, and turned my head that I should not see the cruel thing to the end.

When the lad fainted they gave him a few kicks with their heavy boots, and he lay like a log on the floor, until the ruffian named "Roaring John" picked him up and threw him into the next room. The incident was forgotten at once, and Captain Black became quite merry.

"Bring in the victuals, you, John," he said, "and let Dick say us a grace; he's been doing nothing but drink these eight hours."

Dick, a red-haired, penetrating-looking Scotsman, who carried the economy of his race even to the extent of flesh, of which he was sparse, greeted the reproof by casting down his eyes into the empty can before him.

"Is a body to cheer himself wi' naething?" he asked; "not wi' a bit food and drink after twa days' toil? It's an unreasonable man ye are, Mister Black, an' I dinna ken if I'll remain another hoor as meenister to yer vessel."

"Ho, ho, Dick the Ranter sends in his resignation; listen to that, boys," said the Captain, who had found his humour again. "Dick will not serve the honourable company any longer. Ho, swear for the strangers, Dick, and let 'em hear your tongue."

The man, rascal and ill-tongued as I doubt not he was at times, refused to comply with the demand as the food at length was put upon the table. It was rich food, stews, with a profuse display of oysters, chickens, boiled, roast, à la maître d'hôtel, fine French trifles, pasties, ices—and it was to be washed down, I saw, by draughts from magnums of Pommery and Greno. I was, at this stage, so well accustomed to the scene that the novelty of a company of dirty, repulsive-looking seamen banqueting in this style did not surprise me one whit, only I wished to be away from a place whose atmosphere poisoned me, and where every word seemed garnished with some horrible oath. I whispered this thought to Hall, and he said, "Yes," and rose to go, but the Captain pulled him back, crying—

"What, little Jew, you wouldn't eat at other people's cost! Down with it, man, down with it; fill your pockets, stuff 'em to the top. Let's see you laugh, old wizen-face, a great sixty per cent. croak coming from your very boots—here, you, John, give the man who hasn't got any money some more drink; make him take a draught."

The men were becoming warmed with the stuff they had taken, and furiously offensive. One of them held Hall while the others forced champagne down his throat, and the man "Roaring John" attempted to pay me a similar compliment, but I struck the cup from his hand, and he drew a knife, turning on me. The action was foolish, for in a moment a tumult ensued. I heard fierce cries, the smash of overturned boards and lights, and remembered no more than some terrific blows delivered with my left, as Molt of Cambridge taught me, a sharp pain in my right shoulder as a knife went home, the voice of Hall crying, "Make for the door—the door," and the great yell of Captain Black above the others. His word, no doubt, saved us from greater harm; for when I had thought that my foolhardiness had undone us, and that we should never leave the place alive, I found myself in the Rue Joubert with Hall at my side, he torn and bleeding as I was, but from a slight wound only.

"That was near ending badly," he said, looking at the skin-deep cut on my shoulder. "They're wild enough sober, but Heaven save anyone from them when they're the other way!"

I looked at him steadily for a moment; then I asked—

"Hall, what does it mean? Who are these men, and what business carries you amongst them?"

"That you'll learn when you open the papers; but I don't think you will open them yet, for I'm going to succeed." He was gay almost to frivolity once more. "Did you hear him ask me to sail with him from Dieppe to-morrow?"

"I did, and I believe you're fool enough to go. Did you see the look he gave you when he said 'Yes'?"

"Never mind his look. I must risk that and more, as I have risked it many a time. Once aboard his yacht I shall have the key which will unlock six feet of rope for that man, or you may call me the Fool again."

It was light with the roseate, warm light of a late summer's dawn as we reached the hotel. Paris slept, and the stillness of her streets greeted the life-giving day, while the grey mist floated away before the scattered sunbeams, and the houses stood clear-cut in the finer air. I was hungry for sleep, and too tired to think more of the strange dream-like scene I had witnessed; but Hall followed me to my bedroom, and had yet a word to say.

"Before we part—we may not meet again for some time, for I leave Paris in a couple of hours—I want to ask you to do me yet one more service. Your yacht is at Calais, I believe—will you go aboard this morning and take her round to Plymouth? There ask for news of the American's yacht—he has only hired her, and she is called La France. News of the yacht will be news of me, and I shall be glad to think that someone is at my back in this big risk. If you should not hear of me, wait a month; but if you get definite proof of my death, break the seal of the papers you hold and read—but I don't think it will come to that."

So saying, he left me with a hearty handshake. Poor fellow, I did not know then that I should break the seal of his papers within three days.

CHAPTER III.

"FOUR-EYES" DELIVERS A MESSAGE.

A warming glare of the fuller sun upon my eyes, the cracking of whips, the shouting of fierce-lunged coachmen, the hum of moving morning life in the city, stirred me from a deep sleep as the clocks struck ten. I sat up in bed, uncertain in the effort of wit-gathering if night had not given me a dream rather than an experience, a chance play of the brain's imagining, and not a living knowledge of true scenes and strange men. For in this mood does nature often play with us, tricking us to fine thoughts as we lie dreaming, or creating such shows of life as we slumber, that in our first moments of wakefulness we do not detect the cheat or reckon with the phantoms. I knew not for some while, as I lay back listening to the hum of busy Paris, if the Perfect Fool had or had not told me anything, if we had gone together to a house near the Rue Joubert, or if we had remained in the hotel, if he had begged of me some favour, or if I had dreamed it. All was but a confused mind-picture, changing as a kaleidoscope, blurred, shadowy. It might have remained so long, had I not, looking about the room, become aware that a letter, neatly folded, lay on the small table at my bedside. It was the letter which brought the consciousness of reality; and in that moment I knew that I had not dreamed but lived the curious events of the night. But these are the words which Martin Hall wrote:—

"Hôtel Scribe. Seven a.m.—I leave in ten minutes, and write you here my last word. We shall sail from Dieppe at midnight. Do not forget to cross to Plymouth if you have any friendship for me. I look to you alone.—Martin Hall."

He had left Paris then, and set out upon his great risk. The man's awe-inspiring courage, his immense self-reliance, his deep purpose, were marked strongly in those few simple words, and I had never felt so great an admiration for him. He looked to me alone, and assuredly he should not look in vain. I would follow him to Plymouth, losing no moment in the act; and I resolved then to go farther if the need should be, and to search for him in every land and on every sea, for he was a brave man whose like I had not often known.

I dressed in haste with this intention, and went to déjeûner in our private room below. Roderick was there, sleepy over his bottle of bad Bordeaux, and Mary, who insisted on taking an English breakfast, was in the height of a dissertation on Parisian tea.

"Did you ever see anything so feeble?" she said, being fond of Roderick's speech mannerisms and often mimicking them. "Isn't it pretty awful?" and she poured some from her spoon.

"'Pretty awful' is not the expression for a polite young woman," replied Roderick, with a severe yawn; "anyone who comes to Paris for tea deserves what he gets."

"Yes, and what he gets 'takes the biscuit.'"

"Mary!"

"Well, you always say, 'takes the biscuit'; why shouldn't I?"

"Because, my child, because," said Roderick, slowly and paternally, "because—why, here's Mark. Hallo! you're a pretty fellow; I hope you enjoyed yourself last night."

"Exceedingly, thanks; in fact, I may say that I had a most delightful evening with men who suited me to the—tea—thank you, Mary! I'll take a cup—and now tell me, what has he bought you?"

I thought that a judicious policy of dissimulation was the wise course at that time, for I had not then determined to share my secret even with Roderick, as, indeed, by my word I was bound not to do until Hall should so wish. In this intent I hid all my serious mood, and continued the pleasant chatter.

Mary had soon poured out a cup of the decoction which Frenchmen call tea, an aqueous product, the fluid of chopped hay long stewed in tepid water, and then she answered—

"Let me see, now, what did Roderick buy me? Oh, yes! I remember, he bought me a meerschaum pipe and a walking-stick!"

"A what?" I gasped.

"A meerschaum pipe, and a walking-stick with a little man to hold matches on the top of it."

Roderick looked guilty, and admitted it.

"You see," he said in apology, "they sold only those things at the first place we came to, and you don't expect a fellow to walk in Paris, do you? Now, when I've rested after breakfast, I suggest that we all make up our minds for a long stroll, and get to the Palais Royal."

"Well, that's about three hundred yards from here, isn't it? Are you quite sure you're equal to it?"

He looked at me reproachfully.

"You don't want a man to kill himself on his holiday, do you? You're fatally energetic. Now, I believe that the science of life is rest, the calm survey of great problems from the depths of an armchair. It's astonishing how easy things are if you take them that way; never let anything agitate you—I never do."

"No, he don't, does he, Mary? But about this excursion to the Palais Royal; I'm afraid you'll have to go alone, for I have just had a letter which calls me back to the yacht. It's awfully unfortunate, but I must go, although I will return here in a week, if possible, and pick you up; otherwise, you will hear of my movements as soon as I know them myself."

Somewhat to my astonishment, they both looked at me, saying nothing, but evidently very much surprised. Mary's big eyes were wide open with amazement, but Roderick had a more serious look on his face. He did not question me, he did not say a word, but I felt his thought—"You hold something back"—and the mute reproach was keen. Perhaps some explanation would then have been demanded had not another interruption broken the unwelcome silence. One of the servants of the hotel entered to tell me that a man who wished to speak with me was waiting outside, and asked if I would see him there or in the privacy of our room. As I could not recall that anyone in Paris had any business with me, I said, "Send the man here"; and presently he entered, when to my intense surprise I found him to be no other than one of the ruffians—the one called "Four-Eyes" by the Captain of the company I had met on the previous evening. Not that he seemed in any way abashed at the meeting—he walked into the room with a seaman's lurch, and steadied himself only when he saw Mary. Then he rang an imaginary bell-rope on his forehead, and "hitched" himself together, as sailors say, looking for all the world like some great dog that has entered a house where dogs are forbidden. His first words were somewhat unexpected—

"Oi was priest's boy in Tipperary, bedad," said he, and then he looked round as if that information should put him on good terms with us.

"Will you sit down, please?" was my request as he stood fingering his hat, and looking at Mary as though he had seen a vision, "and permit me to ask what the fact of your serving a priest in Ireland has to do with your presence here now?"

"That brings us to the point av it, and thanking yer honor, it's meself that ain't aisy on them land-craft which don't carry me cargo on an even keel at all, so I'll be standin', with no offence to the Missy, sure, an' gettin' to the writin' which is fur yer honor's ear alone as me instruckthshuns goes."

He rang the bell-rope over his right eye again, and gave me a letter, well written on good paper. I watched him as I read it, and saw that in a power of eye that was astounding, he had fixed one orb upon Mary and one upon the ceiling, and that the two objects shared his gaze, while his body swayed as though he was unaccustomed to balance himself upon a fair floor. But I read his letter, and write it for you here—

"Captain Black presents his compliments to Mr. Mark Strong, whom he had the pleasure of receiving last night, and regrets the reception which was offered to him. Captain Black hopes that it will be his privilege to receive Mr. Strong on his yacht La France, now lying over against the American vessel Portland, in Dieppe harbour, at 11 to-night, and to extend to him hospitality worthy of him and his host."

Now, that was a curious thing indeed. Not only did it appear that my pretence of being Hall's partner in trade was completely unmasked by this man of the Rue Joubert; but he had my name—and, by his tone in writing, it was clear that he knew my position, and the fact that I was no trader at all. Whether such knowledge was good for me, I could not then say; but I made up my mind to act with cunning, and to shield Hall in so far as was possible.

"Did your master tell you to wait for any answer?" I asked suddenly, as the seaman brought his right eye from the direction of the ceiling and fixed it upon me; and he said—

"Is it for the likes of me to be advisin' yer honor? 'Sure,' says he, 'if the gentleman has the moind to wroite he'll wroite, if he has the moind to come aboard me—meanin' his yacht—he'll come aboard; and we'll be swimming in liquor together as gents should. And if so be as the gentleman' (which is yer honor), says he, 'will condescend to wipe his fate on me cabin shates, let him be aboard at Dieppe afore seven bells,' says he, 'and we'll shame the ould divil with a keg, and heave at daybreak'—which is yer honor's pleasure, or otherwise, as it's me juty to larn!"

It needed no very clever penetration on my part to read danger in every line of this invitation—not only danger to myself, who had been dragged by the heels into the business, but danger to Hall, whose disguise could scarce be preserved when mine was unmasked. And yet he had left Paris, and even then, perhaps, was in the power of the man Black and his crew! What I could do to help him, I could not think; but I determined if possible to glean something from the palpably cunning rogue who had come on the errand.

"I'll give you the answer to this in a minute," said I; "meanwhile, have a little whisky? A seaman like yourself doesn't thrive on cold water, does he?"

"Which is philosophy, yer honor—for could wather never warmed any man yet—me respects to the young lady"—here he looked deep into his glass, adding slowly, and as if there was credit to him in the recollection, "Oi was priest's boy in Tipperary, bedad"—and he drank the half of a stiff glass at a draught.

"Do you find this good weather in the Channel?" I inquired suddenly, looking hard at him over the table.

He made circles with his glass, and turned his eyes upon Mary, before he answered; and when he did, his voice died away like the fall of a gale which is tired. "Noice weather, did ye say—by the houly saints, it depends."

"On what?" I asked, driving the question home.

"On yer company," said he, returning my gaze, "and yer sowl."

"That's curious!"

"Yes, if ye have one to lose, and put anny price on it."

His meaning was too clear.

"Tell your master, with my compliments," I responded, "that I will come another time—I have business in Paris to-day!"

He still looked at me earnestly, and when he spoke again his voice had a fatherly ring. "If I make bold, it's yer honor's forgiveness I ask—but, if it was me that was in Paris I'd stay there," and putting his glass down quickly, he rolled to the door, fingered his hat there for one moment, put it on awry, and with the oft-repeated statement, "Oi was priest's boy in Tipperary, bedad," he swayed out of the room.

When he was gone, the others, who had not spoken, turned to me, their eyes asking for an explanation.

"One of Hall's friends," I said, trying to look unconcerned, "the mate on the yacht La France—the vessel he joins to-day."

Roderick tapped the table with his fingers; Mary was very white, I thought.

"He knows a queer company," I added, with a grim attempt at jocularity, "they're almost as rough as he is."

"Do you still mean to sail to-night?" asked Roderick.

"I must; I have made a promise to reach Plymouth without a moment's delay."

"Then I sail with you," said he, being very wide-awake.

"Oh, but you can't leave Paris; you promised Mary!"

"Yes, and I release him at once," interrupted Mary, the colour coming and going in her pretty cheeks, "I shall sail from Calais to-night with you and Roderick."

"It's very kind of you—but—you see——"

"That we mean to come," added Roderick quickly. "Go and pack your things, Mary; I have something to say to Mark."

We were alone, he and I, but there was between us the first shadow that had come upon our friendship.

"Well," said he, "how much am I to know?"

"What you choose to learn, and as much as your eyes teach you—it's a promise, and I've given my word on it."

"I was sure of it. But I don't like it, all the same—I distrust that fool, who seems to me a perfect madman. He'll drag you into some mess, if you'll let him. I suppose there's no danger yet, or you wouldn't let Mary come!"

"There can be no risk now, be quite sure of that—we are going for a three days' cruise in the Channel, that is all."

"All you care to tell me—well, I can't ask more; what time do you start?"

"By the club train. I have two hours' work to do yet, but I will meet you at the station, if you'll bring my bag——"

"Of course—and I can rest for an hour. That always does me good in the morning."

I left him so, being myself harassed by many thoughts. The talk with Black's man did not leave me any longer in doubt that Hall had gone to great risk in setting out with the ruffian's crew; and I resolved that if by any chance it could be done, I would yet call him back to Paris. For this I went at once to the office of the Police, and laid as much of the case before one of the heads as I thought needful to my purpose. He laughed at me; the yacht La France was known to him as the property of an eccentric American millionaire, and he could not conceive that anyone might be in danger aboard her. As there was no hope from him, I took a fiacre and drove to the Embassy, where one of the clerks heard my whole story; and while inwardly laughing at my fears, as I could see, promised to telegraph to a friend in Calais, and get my message delivered.

I had done all in my power, and I returned to the Hôtel Scribe; but the others had left for the station. Thither I followed them, instructing a servant to come to me at the Gare du Nord if any telegram should be sent; and so reached the train, and the saloon. It was not, however, until the very moment of our departure that a messenger raced to our carriage, and thrust a paper at me; and then I knew that my warning had come too late. The paper said: "La France has sailed, and your friend with her."

CHAPTER IV.

A STRANGE SIGHT ON THE SEA.

It was on the morning of the second day; three bells in the watch; the wind playing fickle from east by south, and the sea agold with the light of an August sun. Two points west of north to starboard I saw the chalky cliffs of the Isle of Wight faint through the haze, but away ahead the Channel opened out as an unbroken sea. The yacht lay without life in her sails, the flow of the swell beating lazily upon her, and the great mainsail rocking on the boom. We had been out twenty-four hours, and had not made a couple of hundred miles. The delay angered every man aboard the Celsis, since every man aboard knew that it was a matter of concern to me to overtake the American yacht, La France, and that a life might go with long-continued failure.

As the bells were struck, and Piping Jack, our boatswain—they called him Piping Jack because he had a sweetheart in every port from Plymouth to Aberdeen, and wept every time we put to sea—piped down to breakfast, my captain betrayed his irritation by an angry sentence. He was not given to words, was Captain York, and the men knew him as "The Silent Skipper"; but twenty-four hours without wind enough to "blow a bug," as he put it, was too much for any man's temper.

"I tell you what, sir," he said, sweeping the horizon with his glass for the tenth time in ten minutes, "this American of yours has taken the breeze in his pocket, and may it blow him to——I beg your pardon, I did not see that the young lady had joined us."

But Mary was there, fresh as a rose dipped in dew, and as Roderick followed her up the companion ladder, we held a consultation, the fifth since we left Calais.

"It's my opinion," said Roderick, "that if those men of yours had not been ashore on leave, York, and we could have sailed at midnight, we should have done the business and been in Paris again by this time."

"It's my opinion, sir, that your opinion is not worth a cockroach," cried the captain quite testily; "the men have nothing to do with it. Look above; if you'll show me how to move this ship without a hatful of wind, I'll do it, sir," and he strutted off to breakfast, leaving us with Dan, the forward look-out.

Dan was a grand old seaman, and there wasn't one of us who didn't appeal to him in our difficulties.

"Do you think it means to blow, Dan?" I asked, as I offered him my tobacco-pouch: and Mary said earnestly—

"Oh, Daniel, I do wish a gale would come on!"

"Ay, Miss, and so do many of us; but we can't be making wind no more'n we can make wittals—and excusing me, Miss, it ain't Daniel, not meaning no disrespect to the other gent, whose papers were all right, I don't doubt, but my mother warn't easy in larning, and maybe didn't know of him—it's Dan, Miss, free-and-easy like, but nat'ral."

"Well, Dan, do you think it will blow? Can't you promise it will blow?"

"Lor, Miss, I'd promise ye anything; but what is nater is nater, and there's an end on it—not as I don't say there won't be a hatful o' wind afore night—why should I? but as for promisin' of it, why I'd give ye a hurricane willing—or two."

We went down to breakfast, the red of sea strength on our cheeks; and in the cosy saloon we made short work of the coffee and soles, the great heaps of toast, and the fresh fruit. I could not help some gloomy thoughts as I found myself on my own schooner again, asking how long she would be mine, and how I should suffer the loss of her when all my money was spent. These were cast off in the excitement of the chase, and came only in the moments of absolute calm, when all the men aboard fretted and fumed, and every other question was: "Isn't it beginning to blow?"

The morning passed in this way, a long morning, with the sea like a mirror, and the sun as a great circle of red fire in the haze. Hour after hour we walked from the fore-hatch to the tiller, from the tiller to the fore-hatch, varying the exercise with a full inspection of every craft that showed above the horizon. At eight bells we lay a few miles farther westward, the island still visible to the starboard, but less distinct. At four bells, when we went to lunch, the heat was terrible below, and the sun was terrible on deck; but yet there was not a breeze. At six bells some dark and dirty clouds rose up from the south, and twenty hands pointed to them. At "one bell in the first dog" the clouds were thick, and the sun was hidden. Half-an-hour later there was a shrill whistling in the shrouds, and the rain began to patter on the deck, while the booms fretted, and we relieved her in part of her press of sail. When the squall struck us at last, the Channel was foaming with long lines of choppy seas; and the sky southward was dark as ink. But there was only joy of it aboard; we stood gladly as the Celsis heeled to it, and rising free as an unslipped hound, sent the spray flying in clouds, and dipped her decks to the foam which washed her.

During one hour, when we must have made eleven knots, the wind blew strong, and was fresh again after that; so that we set the foresail unreefed and let the great mainsail go not many minutes later. The swift motion was an ecstasy to all of us, an unbounded delight; and even the skipper softened as we stood well out to sea, and looked on a great continent of clouds underlit with the spreading glow of the sunset, their rain setting up the mighty arched bow whose colours stood out with a rich light over the wide expanse of the east. Nor did the breeze fall, but stiffened towards night, so that in the first bell, when we came up from dinner, the Celsis was straining and foaming as she bent under her pressure of canvas, and it needed a sailor's foot to tread her decks. But of this no one thought, for we had hardly come above when we heard Dan hailing—

"Yacht on the port-bow."

"What name?" came from twenty throats.

"La France," said Dan, and the words had scarce left his lips when the skipper roared the order—

"Stand by to go about!"

For some minutes the words "'bout ship" were not spoken. The schooner held her course, and rapidly drew up with the yacht we had set out to seek. From the first there was no doubt about her name, which she displayed in great letters of gold above her figure-head. Dan had read them as he sighted her; and we in turn felt a thrill of delight as we proved his keen vision, watching the big cutter, for such she was, heading, not for Plymouth, but for the nearer coast. But this was not the only strange thing about her course, for when she had made some few hundred yards towards the coast, she jibbed round of a sudden, with an appalling wrench at the horse; and there being, as it appeared, no hand either at the peak halyards or the throat halyards, the mainsail presently showed a great rent near the luff, while the foresail had torn free from the bolt-ropes of the stay, and was presenting a sorry spectacle as the yacht went about, and away towards France again.

Such a display of seamanship astounded our men.

"Close haul, you lubbers; close haul!" roared Dan, in the vain delusion that his voice would be heard a quarter of a mile away. "Keep down yer 'elm and close haul—wash me in rum if he ain't comin' up again, and there she goes right into it. Shake up, you gibbering fools; luff her a bit and make fast. Did ye ever see anythin' like it this side of a Margit steamer?"

The skipper said nothing, but as the yacht luffed right up into the wind again, he groaned as a man who is hurt. Piping Jack looked sorrowful too, and said, almost with tears in his eyes—

"Axin' yer pardon, sir, but hev you got a pair of eyes in your head which can make out anything unusual aboard there?"

"They're a queer lot, if that's what you mean, and they haven't got enough seamanship amongst them to run a washing tub. Is there anything else you make out?"

"A good deal, sir; and look you, there ain't a living soul on her deck, or may I never see shore again."

"By all that's curious, you're right. There isn't a man showing!"

"'Bout ship," roared the skipper, and every man ran to his post, while I touched Captain York on the shoulder and pointed to the seemingly deserted and errant yacht.

But the skipper's eyes were not those of a ground-gazer; he needed no aid from me; what others had seen, he had seen, and he nodded an affirmative to my unspoken question.

"What do you think it means?" I asked, as we came up into the wind, and the men were belaying after close hauling for the beat; "are they hiding from us, or is she deserted?"

But the only answer I got was the one word "Rum," uttered with a jerky emphasis, and taken up by Dan, who said—

"Very rum, and a good many drunk below, or I don't know the taste of it."

The obvious thought that the yacht we had sought and run down was without living men upon her decks had taken the lilt from the seamen's merry tongues, and a gloom settled on us all. Perhaps it was more than a mere surmise, for an uncanny feeling of something dreadful to come took hold of me, and I feared that, finding the yacht, we had also found the devil's work; but I held my peace on that, and made up my mind to act.

"Skipper," said I, "order a boat out; I'm going aboard her."

He looked at me, and shook his head.

"When the wind falls, perhaps; but now!" and he shrugged his shoulders.

"Is there any sign that the breeze will drop?"

"None at present; but I'll tell you more in an hour. Meanwhile," and here he whispered, "get your pistols out and say nothing to the men. I shall follow her."

His advice was wise; and as the dark began to fall and the night breeze to blow fresh, while the yacht ahead of us swung here and there, almost making circles about us, we hove to for the time and watched her. I begged Mary to go below, but she received the suggestion with merriment.

"Go below, when the men say there's fun coming! Why should I go below?"

"Because it may be serious fun."

She took my arm, and linking herself closely to me as to a brother, she said—

"Because there's danger to you and to Roderick; isn't that it, Mark?"

"Not to us any more than to the men; and there may be no danger, of course. It's only a thought of mine."

"And of mine, too. I shall stay where I am, or Roderick will go to sleep."

"What does Roderick say?"

He had joined us on the starboard side, and was gazing over the sea at the pursued yacht, which lay shaking dead in the wind's eye, but Mary's question upset whatever speculation he had entered upon.

"I've got an opinion," he drawled, with a yawn.

"You don't say so——"

"The wind's falling, and it's getting beastly dark."

"Two fairly obvious conclusions; do you think you could keep sufficiently awake to help man the boat?—in another ten minutes we shall see nothing."

"Do you think I'm a fool, that I'm going to stop here?"

"Forgive me, but I'm getting anxious. Martin Hall sailed on that yacht; and I promised to help him—but there's no need for you to do anything, you know."

"No need when you are going—pshaw, I'll fetch my Colt, and Mary shall watch us. I don't think she is afraid of much, are you, Rats?"—he called her "Rats" because they were the one thing on earth she feared—and then he went below, and I followed him, getting my revolver and my oil-skins, for I knew that it would be wet work. I had scarce reached the deck again when I felt the schooner moving; but no break of light showed the place where the other was, and the skipper called presently for a blue flare, which cast a glowing light for many hundred yards, and still left us uncertain.

"She's gone, for sure," said Dan to the men around him, for every soul on board, even including old Chasselot—called by the men "Cuss-a-lot"—our cook, was staring into the thick night; "and I wouldn't stake a noggin that her crew ain't cheated the old un at last an' gone down singing. It's mighty easy to die with your head full o' rum, but I don't go for to choose it meself, not particler."

Billy Eightbells, the second mate, was quite of Dan's opinion. The looks of the others told me then that they began to fear the adventure. Billy was the first really to give expression to the common sentiment.

"Making bold to speak," he said, "it were two years ago come Christmas as I met something like this afore, down Rio way——"

"Was it at eight bells, Billy?" asked Mary mischievously. She knew that all Billy's yarns began at eight bells.

"Well, I think it were, mum, but as I was saying——"

"Flash again," said the skipper, suddenly interrupting the harangue, and as the blue light flashed we saw right ahead of us the wanderer we sought; but she was bearing down upon us, and there was fear in the skipper's voice when he roared—

"For God's sake, hard a-starboard!"

The helm went over, and the yacht loomed up black, as our own light died away; and passed us within a cable's length. What lift of the night there was showed us her decks again; but they were not deserted, for as one or two aboard gave a great cry, I saw the white and horridly distorted face of a man who clung to the main shrouds—and he alone was guardian of the wanderer.

The horrid vision struck my own men with a deadly fearing.

"May the Lord help us!" said Dan.

"And him!" added Piping Jack solemnly.

"Was he alive, d'you think?" asked Dan.

"It's my opinion he'd seen something as no Christian man ought to see. Please God, we all get to port again!"

"Please God!" said half-a-dozen; and their words had meaning.

For myself, my thoughts were very different. That vision of the man I had left well and hopeful and strong not three days since was terrible to me. A brave man had gone to his death, but to what a death, if that agonised face and distorted visage betokened aught! And I had promised to aid him, and was drifting there with the schooner, raising no hand to give him help.

"Skipper," I cried, "this time we'll risk getting a boat off; I'm going aboard that vessel now, if I drown before I return." Then I turned to the men, and said: "You saw the yacht pass just now, and you saw that man aboard her—he's my friend, and I'm going to fetch him. Who amongst you is coming with me?"

They hung back for a moment before the stuff that was in them showed itself; then Dan lurched out, and said—

"I go!"

Billy Eightbells followed.

"And I," said he, "if it's the Old One himself."

"And I," said Piping Jack.

"And I," said Planks, the carpenter.

"Come on, then, and take your knives in your belts. Skipper, put about and show another light."

He obeyed mechanically, saying nothing; but he was a brave man, I knew. It was our luck to find that the boat went away from the davits with no more than a couple of buckets of water in her; and in two minutes' time the men were giving way, and we rose and fell to the still choppy sea, while the green spray ran from our oilskins in gallons. In this way we made a couple of hundred yards in the direction we judged the yacht would turn, and lit a flash. It showed her a quarter of a mile away, jibbing round and coming into the wind again.

"We shall catch her on the tack if she holds her bearing," said Dan, "and be aboard in ten minutes."

"What then?" said Billy.

"Ay, what then?" echoed the others.

"But it's a friend of the guv'nor's," repeated Dan, "and he's in danger—no common danger, neither. Please God, we all get to port again."

"Please God!" they responded, and Roderick, who sat at the tiller with me, whispered—

"I never saw men who liked a job less."

As the good fellows gave way again, and the boat rode easily before the wind, I noticed for the first time that the clouds were scattering; and we had not made another cable's length when a great cloud above us showed silver at its edges, and opaquely white in its centre, through which the moon shone. Anon it dissolved, and the transformation on the surface of the water was a transformation from the dark of storm to the chrome light of a summer moon. There, around us, the panorama stretched out: the sea, white-waved and rolling; the lights of a steamer to port; of a couple of sailing vessels astern; of a fishing fleet away ahead, and nearer to the shore. But these we had no thought for, since the deserted yacht was beating up to us, and we stood right in her track.

"Get a grapnel forward, and look out there," cried Dan, who was in command; and Billy stood ready, while we could hear the swish of the waves against the cutter's bows, and every man instinctively put his hand on his pistol or his knife.

As if to help us, the wind fell away as the schooner came up, and she began to shake her sails; making no way as she headed almost due east. It seemed a fit moment for effort, and Dan had just sung out "Give way," when every man who had gripped an oar let go the handle again and sat with horror writ on his countenance. For, almost with the words of the order, there was the sound as of fierce contest, of the bursting of wood, and the spread of flame; and in that instant the decks of the yacht were ripped up, and sheets of fire rose from them to the rigging above. The light of this mighty flare spread instantly over the sea about her, and far away you could look on the rolling waves, red as waves of fire. A terrible sight it was, and terrible sounds were those of the wood rending with the heat, of the stays snapping and flying, of the hissing of the flame where it met the water. But it was a sight of infinite horror to us, because we knew that one who might yet live was a prisoner of the conflagration—the one passenger, as it seemed then, of the vessel which was doomed.

"Give way," roared Dan again, for the men sat motionless with terror. "Are you going to let him burn? May God have mercy on him, for he needs mercy!"

The words awed them. They shot the long-boat forward; and I stood in her stern to observe, if I could, what passed on the burning decks. And I saw a sight the like to which I pray that I may never see again. Martin Hall stood at the main shrouds, motionless, volumes of flame around him, his figure clear to be viewed by that awful beacon.

"Why doesn't he jump it?" I called aloud. "If he can't swim, he could keep above until we're alongside"; and then I roared "Ahoy!" and every man repeated the cry, calling "Ahoy!" each time he bent to his oar, his voice hoarse with excitement. But Martin Hall never moved, his gaunt figure was motionless—the flames beat upon it, it did not stir; and we drew near enough anon and knew the worst.

"Devils' work, devils' work!" said Dan; "he's lashed there—and he's dead!" But the men still cried "Ahoy!" as they rushed their oars through the water, and were as those mad with fiery drink.

"Easy!" roared Dan. "Easy, for a parcel of stark fools! Would you run alongside her?"

There they lay, for any nearer approach would have been perilous, and even in that place where we were, twenty feet on the windward side, the heat was nigh unbearable. So near were we that I looked close as it might be into the dead face of Martin Hall, and saw that the fiends who had lashed him there had done their work too well. But I hoped in my heart that he had been dead when the end of the ship had begun to come, and that it were no reproach to me that he had perished: for to save his body from that holocaust was work no man might do.

So did we watch the mounting fire, and the last tack of the yacht La France. Saucily she raised her head to a new breeze, shook her great sail of flame in the night, and scattered red light about her. Then she dipped her burning jib as if in salute, and there was darkness.

"Rest to a good ship," said Dan, in melancholy mood; but I said—

"Rest to a friend." I had known the man whose death had come; and when his body went below I hungered for the grip of the hand which was then washed by the Channel waves.

"Give way," I cried to the men, who sat silent in their fear of it, and when they rowed again they cried as before, "Ahoy": so strong and vivid was the picture which the sea had then put out.

As we neared our own ship, Roderick endeavoured to speak to me, but his voice failed, and he took my hand, giving it a great grip. Then we came on board, where Mary waited for us with a white face, and the others stood silent; but we said nothing to them, going below. There I locked myself in my own cabin, and though fatigue lay heavy on me, and my eyes were clouded with the touch of sleep, I took Martin Hall's papers from my locker, and lighted the lamp to read them through.

But not without awe, for they were a message from the dead.

CHAPTER V.

THE WRITING OF MARTIN HALL.

The manuscript, which was sealed on its cover in many places, consisted of several pages of close writing, and of sketches and scraps from newspapers—Italian, French, and English. The sketches I looked at first, and was not a little surprised to see that one of them was the portrait of the man known as "Roaring John," whom I had met at Paris in the strange company; while there was with this a blurred and faint outline of the features of the seaman called "Four-Eyes," who had come to me at the Hôtel Scribe with the bidding to go aboard La France. But what, perhaps, was even more difficult to be understood was the picture of the great hull of what I judged to be a warship, showing her a-building, with the work yet progressing on her decks. The newspaper cuttings I deemed to be in some part an explanation of these sketches, for one of them gave a description of a very noteworthy battleship, constructed for a South American Republic, but in much secrecy; while another hinted that great pains had been taken with the vessel, which was built at a mighty cost, and on so new a plan that the shipwrights refused to give information concerning her until she had been some months at sea to prove her.

All this reading remained enigmatical, of course, and as I could make nothing of it to connect it with the events I have narrated, I went on to the writing, which was fine and small, as the writing of an exact man. And the words upon the head of it were these:—

SOME ACCOUNT OF A NAMELESS WARSHIP,

Of Her Crew, and Her Purpose.