The Project Gutenberg EBook of The International Magazine, Volume 2, No. 3, February, 1851, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The International Magazine, Volume 2, No. 3, February, 1851 Author: Various Release Date: August 5, 2008 [EBook #26196] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE, FEBRUARY, 1851 *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections.)

Transcriber's note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of Contents has been created for the HTML version.

THOMAS CHATTERTON.

Authors and Books.

The Fine Arts.

THE AUTHORESS OF "JANE EYRE," AND HER SISTERS.

DAVIS ON THE LAST HALF CENTURY.

POPULAR LECTURES.

OLD TIMES IN NEW-YORK.

ROSSINI IN THE KITCHEN.

THE FIRST PEACE SOCIETY.

EGYPT UNDER THE PHARAOHS.

CAMILLE DESMOULINS.

THE BATTLE OF THE CHURCHES IN ENGLAND.

KILLING OF SIR ALEXANDER BOSWELL.

THE LATE DR. TROOST.

MADAME DACIER.

Original Poetry.

SCANDALOUS DANCES.

THEATRICAL CRITICISM.

THE FRENCH GENERALS OF TO-DAY.

WILLIAM PENN AND MACAULAY.

A STORY WITHOUT A NAME.

CHARLES MACKAY'S LAST POEMS.

THE COUNT MONTE-LEONE, OR, THE SPY IN SOCIETY.

PUBLIC LIBRARIES.

THE JOURNALS OF LOUIS PHILIPPE.

THE BUNJARAS.

THE MYSTIC VIAL

BARRY CORNWALL'S LAST SONG.

ANIMA MUNDI.

THE GHETTO OF ROME.

HENRY C. CAREY, AND HIS POLITICAL ECONOMY.

MY NOVEL: OR, VARIETIES IN ENGLISH LIFE.

DANTE.

AN EDITORIAL VISIT.

BIOGRAPHIES, LIVES, MEMOIRS, AND RECOLLECTIONS.

PHENOMENA OF DEATH.

BURLESQUES AND PARODIES.

JOHN ADAMS UPON RICHES.

RECENT DEATHS.

Scientific Miscellany.

Ladies Fashions for February.

In the history of English literature there is no name that inspires a profounder melancholy than that of the "marvellous boy" Chatterton, of whom it must be said that in genius he surpassed any one who ever died so young, and that in suffering he had larger experience than almost any one who has lived to old age. Shelley says of him:

And Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Byron, Southey, Scott, Kirke White, Landor, Montgomery, and others, have laid immortal flowers upon his tomb, to make the heart ache that we did not live in time to save the "sleepless soul" from "perishing in his pride."

Of the genius of poor Chatterton, Campbell says, "I would rather lean to the utmost enthusiasm of his admirers, than to the cold opinion of those who are afraid of being blinded to the defects of the poems attributed to Rowley, by the veil of obsolete phraseology which is thrown over them. If we look to the ballad of Sir Charles Bawdin, and translate it into modern English, we shall find its strength and interest to have no dependence on obsolete words. The inequality of his various productions may be compared to the disproportions of the ungrown giant. His works had nothing of the definite neatness of that precocious talent which stops short in early maturity. His thirst for knowledge was that of a being taught by instinct to lay up materials for the exercise of great and undeveloped powers. Even in his favorite maxim, that a man by abstinence and perseverance might accomplish whatever he pleased, may be traced the indications of a genius which nature had meant to achieve immortality. Tasso alone can be compared to him as a juvenile prodigy."

Mrs. S. C. Hall gives us, in her "Pilgrimages to English Shrines," in the Art Journal, the following interesting sketches of scenes connected with his history:—

Chatterton—poor Chatterton! We had been brooding sadly over his fragment of a life, ending at seventeen—when ordinary lives begin—and turning page after page of Horace Walpole's literary fooleries, to find his explanations and apologies for want of feeling and sympathy, which his flippant style, and heartless commentaries, illustrate to perfection; and we closed, with an aching heart, the volumes of both the parasite of genius, and him who was its mightiest creation and most miserable victim:—

It was only natural for us to recall the many instances we have ourselves known, during the past twenty years, or more, of sorrow and distress among those who sought distinction in the thorny labyrinths of literature;—those who

and those who, after a brief struggle with untoward fate, left the battle-field, to die, "unpitied and unknown!"

We have seen the career of a young literary man commenced with the first grand requisite of all excellence worth achieving—enthusiasm; high notions of moral honor, and a warm devotedness to that "calling" which lifts units to a pinnacle formed by the dry bones of hundreds slain. We have seen that enthusiasm frozen by disappointment—that honor corrupted by the contamination of dissipated men—that devotedness to the cause fade away before the great want of nature—want of bread—which it had failed to bestow. We have seen, ay, in one little year, the flashing eye dimmed—the round cheek flattened—the bright, hopeful creature, who went forth into the world—rejoicing like the sun to run his course—dragged from the waters of our leaden Thames, a discolored remnant of mortality—recognized only by the mother who looked to him for all the world could give!

This is horrible—but it is a tragedy soon played out. There are hundreds at this moment possessed of the consciousness of power without the strength to use it. To such, a little help might lead to a life of successful toil—perhaps the happiest life a man can lead. A heritage of usefulness is one of peace to the last. We knew another youth, of a more patient nature than he of whom we have just spoken. He seemed never weary. We have witnessed his nightly toil; his daily labor; the smiling patience with which he endured the sneers levelled, only in English society, against "mere literary men." We remember when, on the first day of every month, he used to haunt the booksellers' shops to look over the magazines, cast his eyes down the table of contents, just to see if "his poem" or "his paper" had been inserted—then lay them down one after another with a pale sickly smile, expressive of disappointment, and turn away with a look of gentle endurance. The insertion of a sonnet, for which perhaps he might receive seven shillings, would set him dreaming again of literary immortality; and at last the dream was realized by an accident, or rather, to speak advisedly, by a good Providence. He became known—known at once—blazed forth; something he had written attracted the town's attention, and ladies in crowded drawing-rooms stood upon chairs to see that poor, worn, pale man of letters: and magazines, and grave reviews, and gayly-bound albums, all waited for his contributions—charge what he pleased; and flushed with fame, and weighed down with money—money paid for the very articles that had been rejected without one civil line of courtesy—the great sustaining hope of his life was realized; he married one as worn and pale with the world's toil, as himself—married—and died within a month! The tide was too tardy in turning!

Who shall say how many men of genius have walked, like unhappy Chatterton, through the valley of the shadow of death, and found no guide, no consolation—no hope; if, the one Great Hope had not been most mercifully planted early in their hearts and minds?

It was with melancholy pleasure that, during the past summer, our Pilgrimage was made to the places connected with the boy's memory, in Bristol; first to Colston's school, in which he was educated;[1] next to the dull district in which he was either born or passed his boyhood; then to the Institution, where his "Will," a mad document, and other memoranda connected with his memory, are preserved with a degree of care, that seems—or is—a mockery, when contrasted with the worse than indifference of the city to all that concerned him when alive; next to the house of Master Canynge, and next to the monument (Redcliffe Church) with which his name will be associated as long as one of its stones remains upon another; chewing the cud of sweet and bitter fancies through its long-drawn aisles; pondering sadly in the muniment-room, where the cofres that suggested the forgeries, still lie rotting; and gazing with mingled sorrow and surprise on the "Cenotaph to Chatterton," which now, taken to pieces, occupies the corner of a damp vault—

Ah! such books as we have been reading, and such memories as we have been recalling, are, after all, unprofitable—a darkness without light. We closed our eyes upon the world, which, in our momentary bitterness, we likened to one great charnel-house, entombing all things glorious and bright. We walked to the window; the rain was descending in torrents—pour, pour; pattens clattered in the areas, and a solitary postman made the street echo with his impatient knocks. A poor organ-boy, whom we have long known, was moving, rather than walking, in the centre; his hat[Pg 291] flapped over his eyes by the rain, yet still he turned the handle, and the damp music crawled forth: he paused opposite our door, turned up the leaf of his hat, and looked upward; we missed the family of white mice which usually crawled on the top of his organ: poor child, he had sheltered them in his bosom; it was nothing more than natural that he should do so, and the act was commonplace enough—but it pleased us—it diminished our gloom. And we thought, if the great ones of the land would but foster the talent that needs, and deserves, protection from the storms of life, as that lonely boy sheltered the creatures intrusted to his care, the world would be all the better. We do not mean to insult the memory of such a genius as Chatterton by saying that he required a patron—the very sound is linked with a servility that degrades a noble nature; but we do say he sadly wanted a friend—some one who could have understood and appreciated his wonderful intellectual gifts; and whose strength of mind and position in society would have given power to direct and control the overleaping and indomitable pride which ultimately destroyed "the Boy." His career teaches a lesson of such rare value to all who seek distinction in any sphere of life, that we would have it considered well—as a beacon to warn from ruin.

Despite his marvellous talents, his industry, his knowledge, his magnitude of mind, his glorious imagination, his bold satire, his independence, his devotional love of his mother and sister—if he had lived through a long age of prosperity, Chatterton could never have been trusted, nor esteemed, from his total want of truth. His is the most striking example upon record of the necessity for uprightness in word and deed. Where a great end is to be achieved—there must be consistency, a union between noble daring and noble deeds—there must be Truth! No man has ever deviated from it without losing not only the respect of the thinking, but even the confidence of the unwise. Chatterton's earliest idea seems to have been how to deceive; and, were it possible to laugh at youthful fraud, there would be something irresistibly ludicrous in the lad bewildering the old pewterer, Burgum. Imagine the fair-haired rosy boy, the brightness of his extraordinary eyes increased by the covert mischief which urged him forward—fancy his presenting himself to Master Burgum, who, dull as his own pewter, had the ambition, which the cunning youth fostered, of being thought of an "ancient family"—fancy Chatterton in his poor-school dress presenting himself to this man, whose business, Chatterton's biographer, Mr. Dix, tells us, was carried on in the house now occupied by Messrs. Sander, Bristol Bridge,[2] and informing him that he had made a discovery—presenting to him various documents, with a parchment painting of the De Burgham arms, in proof of his royal descent from the Conqueror.

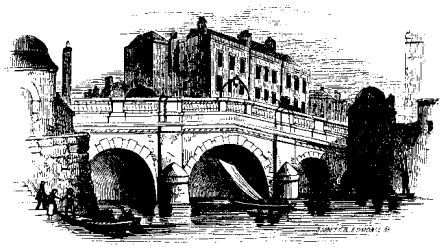

BRISTOL BRIDGE.

BRISTOL BRIDGE.

Mr. Dix assures us, "that never once doubting the validity of the record, in which his own honors were so deeply implicated, he presented the poor bluecoat-boy, who had been so fortunate in finding so much, and so assiduous in his endeavors to collect the remainder, with five shillings!" Blush, Bristol, blush at this record of a citizen's meanness; the paltry remuneration could have hardly tempted even so poor a lad as Thomas Chatterton to continue his labors for the love of gain; yet he furnished Burgum with further information, loving the indulgence of his mystifying powers, and secretly satirizing the folly he duped.

It is quite impossible to trace back any circumstance which could, to speak advisedly, have led to such a course of deception as was practised by this boy; born of obscure parents, his father, a man of dissolute habits, was sub-chanter of the Cathedral, and also master of the free school in Pyle-street; this clever, but harsh, and dissolute man died in August, 1752, and the poet was born on the 20th of the following November.[3] Such a[Pg 292] parent could not be a loss; he would have been, in all human probability, as careless of his son as he was of his wife; and, at all events, Chatterton had not the misery of early cruelty to complain of, for he had a mother, tender and affectionate, although totally unfit to guide and manage his wayward nature. Her first grief with him arose, strange as it may seem, from his inaptitude for learning—as a child he disdained A B C, and indulged himself with his own thoughts. When nearly seven years old he "fell in love," to use his mother's phrase, "with an illuminated French manuscript," and thus learned his letters from the very sort of thing he spent his early days in counterfeiting. His progress was wonderful, both as to rapidity and extent, and his pride kept pace therewith. A friend, wishing to give the boy and his sister a present of china-ware, asked him what device he would choose to ornament his with. "Paint me," he said, "an angel with wings and a trumpet, to trumpet my name over the world." Here was a proof of innate ambition; if his mother had had an understanding mind, this observation would have taught her to read his character. Such ambition could have been directed,—and directed to noble deeds.

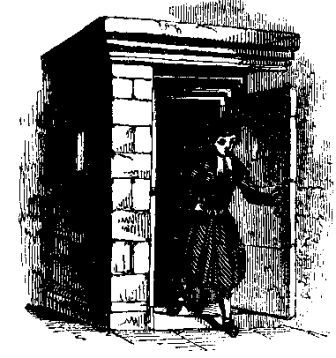

CHATTERTON AS DOORKEEPER.

CHATTERTON AS DOORKEEPER.

BIRTHPLACE OF CHATTERTON.

BIRTHPLACE OF CHATTERTON.

He was admitted into the Blue Coat School, commonly called "Colston's School,"[4] before he was eight years old, and his enthusiastic joy at the prospect of learning so much, was damped by finding that, to quench his thirst for knowledge, "there were not books enough." When he took in rotation the post of doorkeeper at the school, he used to indulge himself in making verses,[5] and[Pg 293] his sister, who loved him tenderly, presented him with a pocket-book, in which he wrote verses, and gave it back to her the following year. There was nothing in this species of tuition or companionship to create or foster either the imitations or the satire he indulged in, he had neither correction nor assistance from any one. Even before his apprenticeship to Mr. John Lambert, he felt he was not appreciated or understood; perhaps no one ever acted a greater satire upon his own profession than this harsh attorney, who deemed his apprentice on a level with his footboy. He must have been a man utterly devoid of perception and feeling; his insulting contempt of what he could not understand added considerably to the sarcastic bitterness of Chatterton's nature, and it is easy to picture the boy's feelings when his productions were torn by this tyrant and scattered on the office floor! He has his reward. John Lambert, the scrivener, is only remembered as the insulter of Thomas Chatterton![6]

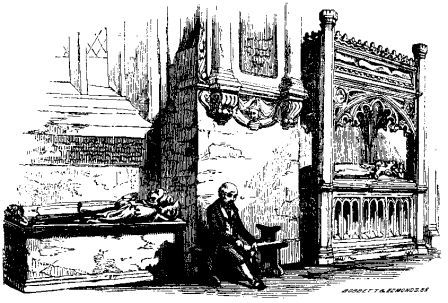

TOMB OF CANYNGE.

TOMB OF CANYNGE.

It is impossible not to pause at every page of this boy's brief but eventful life, and lament that he had no friend; reading, as we do, by the light of other days, we can see so many passages where judicious counsel, given with the intelligent affection that would at once have opened his heart, must have saved him; his heart, once laid bare to friendship, would have been purified by the air of truth; it was its closeness which infected his nature. And yet the scrivener considered him a good apprentice. His industry was amazing; his frequent employment was to copy precedents, and one volume, in his handwriting, which is still extant, consists of three hundred and forty-four closely-written folio pages. There was in that gloomy office an edition of Camden's "Britannia," and, having borrowed from Mr. Green, a bookseller, Speight's "Chaucer," he compiled therefrom an ingenious glossary, for his own use, in two parts. "The first," Mr. Dix says, "contained old words, with the modern English—the second, the modern English, with the old words; this enabled him to turn modern English into old, as an English and Latin dictionary enables the student to turn English into Latin." How miserable it is, amongst these evidences of his industry and genius, to find that all his ingenuity turned to the furtherance of a fraud. He seems to have been morally dead to every thing like the disgrace attending falsehood; for, when struggling afterwards in London to appear prosperous while starving, he wrote home to Mr. Catcott, and concludes his letter by stating that he intended going abroad as a surgeon, adding, "Mr. Barrett has it in his power to assist me greatly, by his giving me a physical character; I hope he will." He seems to have had no idea that he was asking Mr. Barrett to do a dishonest action.

But the grand fraud of his short life was boldly dared by this boy in his sixteenth year. Why he should have ever descended to forge when he felt the high pressure of genius so strong within him, is inexplicable. Why, with his daring pride, he should have submitted to be considered a transcriber, where he originated, is more than marvellous. The spell of a benighting antiquity seemed around him; it might lead one to a belief in "Gramarie"—that some fake spirit had issued forth from the "cofre of Mr. Canynge,"[7] so long[Pg 294] preserved in the room over the north porch of this Bristol church of Redcliffe—a "cofre" secured by six keys, all of which being lost or mislaid, the vestry ordered the "cofre" to be opened; and not only "Canynge's cofre," but all the "cofres," in the mysterious chamber: not from any love of antiquity, but because of the hope of obtaining certain title-deeds supposed to be contained therein. Well, these intelligent worthies, having found what concerned themselves, took them away, leaving behind, and open, parchments and documents which might have enriched our antiquarian literature beyond all calculation.[8] Chatterton's father used to carry these parchments away wholesale, and covered with the precious relics, bibles, and school-books: most likely other officers of the church did the same. After his death, his widow conveyed many of them, with her children and furniture, to her new residence, and, woman-like, formed them into dolls and thread-papers. In process of time, the child's attention being aroused by the illuminated manuscripts, he conveyed every bit of parchment he could find to a small den of a room in his mother's house, which he called his own: and, when he grew a little older, set forth, with considerable tact, in answer to all questions asked of him as to how he obtained the poems and information, that he himself had searched the old "cofres,"[9] and discovered the poems of the Monk Rowley. Certainly he could not have had a better person to trumpet his discovery than "a talkative fool" like Burgum, who was so proud of his pedigree as to torment the officers of the Herald's College about his ancestors; and he was not the only one imposed on by Chatterton's talent. His simple-minded mother bore testimony to his joy at discovering those "written parchments upon the covered books:" and, of course, each discovery added to his antiquarian knowledge; for, though no trace exists of the Monk Rowley's originals, there is little doubt that on some of those parchments he found enough to set him thinking, and with him to think and act was the same thing; indeed, there is one passage in his poems bearing so fully upon the fraud, that we transcribe it. He is writing of having discharged all his obligations to Mr. Catcott:—

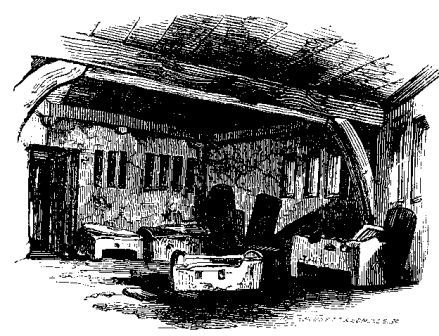

MUNIMENT ROOM.

MUNIMENT ROOM.

A Mr. Rudhall[11] said that, when Chatterton wrote on a parchment, he held it over a candle to give it the appearance of antiquity; and a Mr. Gardener has recorded, that he once saw Chatterton rub a parchment over with ochre, and afterwards rub it on the ground, saying, "that was the way to antiquate it." This exposé of Chatterton's craft is so at variance with his usual caution that we can hardly credit it. A humble woman, Mrs. Edkins, speaks of his spending all his holidays in the little den of a room we have mentioned, where he locked himself in, and would remain the entire day without meals, returning with his hands and face completely begrimed with dirt and charcoal; and she well remembers his having a charcoal pounce-bag and parchment and letters on a little deal table, and all over the ground was a litter of parchments; and she and his mother at one time fancied he intended to discolor himself and run away to the gipsies; but afterwards Mrs. Edkins believed that he was laboring at the Rowley manuscripts, and she thought he got himself bound to a lawyer that he might get at old law books. The testimony she bears to his affectionate tenderness towards his mother and sister is touching: while his pride led him to seek for notoriety for himself, it was only to render his mother and sister comfortable that he coveted wealth.

It is not our province to enter into the controversy as to whether the MSS. were originals or forgeries: it would seem to be as undecided to-day as it was three quarters of a century ago; the boy "died and made no sign:" and the world has not been put in possession of any additional facts by which the question might be determined: the balance of proof appears in favor of those who contend they were the sole offspring of his mind, suggested merely by ancient documents from which he could have borrowed no idea except that of rude spelling; yet it is by no means impossible that poems did actually exist, and came into his hands, which he altered and interpolated, but which he did not create.

In aid of his plans, Chatterton first addressed himself to Dodsley, the Pall Mall bookseller, once with smaller poems, and afterwards on behalf of the greatest production of his genius—the tragedy of "Ella;" but the booksellers of those days were not more intellectual than those at the present: they devoured the small forgery of the great Horace Walpole, "The Castle of Otranto," and rejected the magnificence of a nameless composition. This man's neglect drove the young poet to the "Autocrat of Strawberry Hill." In reply he at first received a polished letter. The literary trifler was not aware of the poverty and low station of his correspondent, and so was courteous; he is "grateful" and "singularly obliged;" bowing, and perfumed, and polite. Other communications followed. Walpole inquired—discovered the poet's situation; and then he changed! The poor fond boy! how hard and bitter was the rebuff. How little had he imagined that the Walpole's soul was not, by five shillings, as large as the Bristol pewterer's!—that he who was an adept at literary imposition could have been so harsh to a fellow-sinner! The volume of his works containing "Miscellanies of Chatterton" is now before us. Hear to his indignant honesty! He declares that "all the house of forgery are relations; and that though it be but just to Chatterton's memory to say his poverty never made him claim kindred with the richest, or more enriching branches, yet that his ingenuity in counterfeiting styles, and I believe hands, might easily have led him to those more facile imitations of prose—promissory notes." The literal meaning of this paragraph stamps the littleness of the man's mind. A slight—a very slight effort on his part might have turned the current of the boy's thoughts, and saved him from misery and death. We do not call Chatterton "his victim," because we do not think him so; but he, or any one in his position, might have turned him from the love of an unworthy notoriety to the pursuit of a laudable ambition. Following in the world's track (which he was ever careful not to outstep), when the boy was dead, Walpole bore eloquent testimony to his genius. The words of praise he gives his memory are like golden grains amid the chaffy verbiage with which he defends himself. If he perceived this at first, why not have come forward hand and heart, and shouted him on to honest fortune? But, like all clique kings, he made no general cause with literature; he only smiled on his individual worshippers, who could applaud when he said, with cruel playfulness, "that singing birds should not be too well fed!"

His master, Lambert, dismissed the youth from his service, because he had reason to suppose he meditated self-destruction; and then he proceeded to London. How buoyant and full of hope he was during his probationary days there, his letters to his mother and sister testify; his gifts, also, extracted from his necessities, are evidences of the bent of his mind—fans and china—luxuries rather than necessaries; but in this, it must be remembered, his judgment was in fault, not his affections. In all things he was swayed and guided by his pride,—his indomitable pride. The period, brief as it was, of his sojourn in the great metropolis proved that Walpole, while he neglected him so cruelly, understood him perfectly, when he said that "nothing in Chatterton could be separated from Chatterton—that all he did was the effervescence of ungovernable impulse, which, chameleon-like, imbibed the colours of all it looked on[Pg 296] it was Ossian, or a Saxon monk, or Gray, or Smollett, or Junius." His first letter to his mother is dated, April the 26th, 1770. He terminated his own existence on the 24th of August in the same year. He battled with the crowded world of London, and, what was in his case a more dire enemy than the world, his overwhelming pride, for nearly four months. Alas! how terrible are the reflections which these few weeks suggest! Now borne aloft upon the billows of hope, sparkling in the fitful brightness of a feverish sun, and then plunged into the slough of despair, his proud, dark soul disclaiming all human participation in a misery exaggerated by his own unbending pride. Let us not talk of denying sympathy to persons who create their own miseries; they endure agonies thrice told. The paltry remuneration he received for his productions is recorded by himself. Among the items is one as extraordinary as the indignant emotion it excites:—

We are wearied for him of the world's dark sight: yet in the same book is recorded that the same publisher owed him £10 19s. 6d.! This sum might have saved him, but he was too proud to ask for money; too proud to complain; too proud to accept the invitation of his acquaintances, or his landlady, to dine or sup with them; and all too proud to hint, even to his mother and sister, that he was any thing but prosperous. Ardent as if he had been a son of the hot south, he had learned nothing of patience or expediency. His first residence was at Mrs. Walmsley's, in Shoreditch, but, doubtless, finding the lodging too expensive, he removed to a Mr. Angell's, sac (or dress) maker, 4, Brook Street, Holborn. This woman, who seems to have been of a gentle nature, finding that for two days he had confined himself to his room, and gone without sustenance, invited him to dine with her; but he was offended, and assured her he was not hungry. It is quite impossible to account for this uncalled for pride. It was his nature. Lord Byron said he was mad: according to his view of the case, all eccentricity is madness; but in the case of unhappy Chatterton, that madness which arises from "hope deferred," was unquestionably endured. Three days before his death, pursuing, with a friend, the melancholy and speculative employment of reading epitaphs in the churchyard of St. Pancras, absorbed by his own reflections, he fell into a new-made grave. There was something akin to the raven's croak, the death-fetch, the fading spectre, in this foreboding accident: he smiled at it, and told his friend he felt the sting of speedy dissolution:—

At the age of seventeen years and nine months, his career ended; it was shown that he had swallowed arsenic in water, and so—

An inquest was held, and yet though Englishmen—men who could read and write, and hear—who must have heard of the boy's talents, either as a poet, a satirist, or a political writer—though these men were guided by a coroner, one, of course, in a more elevated sphere than those who usually determine the intentions of the departed soul—yet was there not one—not one of them all—with sufficient veneration for the casket which had contained the diamond—not one with enough of sympathy for the widow's son—to wrap his body in a decent shroud, and kneel in Christian piety by his grave!—not one to pause and think that, between genius and madness,

In a letter from Southey to Mr. Britton (dated in 1810, to which we have already referred, and which Mr. Britton kindly submitted to us with various other correspondence on the subject), he says, "there can now be no impropriety in mentioning what could not be said when the collected edition of Chatterton's works was published,—that there was a taint of insanity in his family. His sister was once confined; and this is a key to the eccentricities of his life, and the deplorable rashness of his death." Of this unhappy predisposition, indeed, he seems to have been himself conscious, for "in his last will and testament," written in April, 1770, before he quitted Bristol, when he seems to have meditated suicide—although, from the mock-heroic style of the document his serious design may be questioned,—he writes, "If I do a mad action, it is conformable to every action of my life, which all savored of insanity." His "sudden fits of weeping, for which no reason could be assigned," when a mere child, were but the preludes to those gloomy forebodings which haunted him when a boy. His mother had said, "she was often apprehensive of his going mad."

And so,—the verdict having been pronounced, he was cast into the burying-ground of Shoe Lane work-house—the paupers' burying-ground,—the end, as far as his clayey tabernacle was concerned, of all his dreamy greatness. When the ear was deaf to the worship of the charmer, he received his meed of posthumous praise. Malone, Croft, Dr. Knox, Wharton, Sherwin, Pye, Mrs. Cowley, Walter Scott, Haley, Coleridge, Dermody, Wordsworth, Shelley, William Howitt, Keats, who dedicated his "Endymion" to the memory of his fellow-genius; the burly Johnson, whose praise seemed unintentional; the gentle and most Christian poet, James Montgomery,—have each and all offered tributes to his memory. Robert Southey, whose polished, strong and long unclouded mind was a treasure-house of noble-thoughts, assisted Mr. Cottle in providing for the poet's family by a collection of his works; and, though last, not least, excellent John Britton has labored all his long life to render justice to the poor boy's memory. To him, indeed, it was mainly owing, that the cenotaph to which we have referred (and which now lies mouldering in the Church vault), was erected in the graveyard of Redcliffe Church, by subscription, of which the contributions of Bristol were very small.[12]

Chatterton was another warning, not only

but that no mortal should ever abandon Hope! for a reverend gentleman,—who was, in all things,[Pg 297] what, unhappily, Horace Walpole was not,—had actually visited Bristol, to seek out and aid the boy while he lay dead in London.

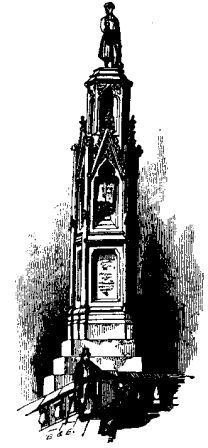

CHATTERTON'S MONUMENT.

CHATTERTON'S MONUMENT.

The knowledge of these facts cheered us as we set forth to the neighborhood of Shoe-Lane to see the spot where he had been laid. Alas, it is very hard to keep pace with the progress of London changes. After various inquiries, we were told that Mr. Bentley's printing office stands upon the ground of Shoe-Lane Workhouse. We ascended the steps leading to this shifting emporium of letters, and found ourselves face to face with a kind gentleman, who told us all he knew upon the subject, which was, that the printing office stands—not upon the burying-ground of Shoe-Lane Workhouse, where he had always understood Chatterton was buried—but upon the church burial-ground. He showed us a very curious basso-relievo, in cut-stone, of the Resurrection, which he assured us had been "time out of mind" above the entrance to the Shoe-Lane burying-place "over the way," and which is now the site of Farrington Market. This, when "all the bones" were moved to the old graveyard in Gray's Inn Road, had come "somehow" into Mr. Bentley's possession.

We were told also that Mr. Taylor, another printer, had lived, before the workhouse was pulled down, where his office-window looked upon the spot pointed out as the grave of Chatterton, and that a stone, "a rough white stone," was remembered to have been "set in a wall" near the grave with "Thomas Chatterton" and something else "scratched" into it.

We strayed back through the damp chill of the city's evening fog to the market-place, hoping, even unconsciously, to stand beside the pit into which the marvellous boy had been thrust; but we grew bewildered. And as we stood upon the steps looking down upon the market—alone in feeling, and unconscious of every thing but our own thoughts—St. Paul's bell struck, full, loud, and clear; and, casting our eyes upward, we saw its mighty dome through the murky atmosphere. We became still more "mazed," and fancied we were gazing upon the monument of Thomas Chatterton!

[1] Of Edward Colston, well and beautifully has William Howitt said, "You cannot help feeling the grand beneficence of those wealthy merchants, who, like Edward Colston, make their riches do their generous will for ever; who become thereby the actual fathers of their native cities to all generations; who roll off, every year of the world's progress, some huge stone of anxiety from the hearts of poor widows; who clear the way before the unfriended, but active and worthy lad; who put forth their invisible hands from the heaven of their rest, and become the genuine guardian angels of the orphan race for ever and ever: raising from those who would otherwise have been outcasts and ignorant laborers, aspiring and useful men; tradesmen of substance; merchants the true enrichers of their country, and fathers of happy families. How glorious is such a lot! how noble is such an appropriation of wealth! how enviable is such a fame! And amongst such men there were few more truly admirable than Edward Colston! He was worthy to have been lifted by Chatterton, to the side of the magnificent Canynge, and one cannot help wondering that he says so little about this great benefactor of his city."

[2] Our engraving shows this house, and Bristol Bridge, both memorable as being connected with the earliest of Chatterton's fabrications. Bristol Bridge was finished in September, 1768, and in the October following Chatterton sent to "Felix Farley's Bristol Journal," the curiously detailed account of the ceremonial observances on opening the ancient bridge at Bristol, 'taken from an Old Manuscript,' and which, being his first printed forgery, led, by the attention it excited, to the production of other work, and among them the Rowley Poems. At this time he was in his 16th year; but some years before he had fabricated Burgum's pedigree, and some poetry by a pretended ancestor of his, of the alleged date of 1320, called "The Romaunte of the Knyghte." The house where Burgum lived, and where Chatterton first tried his powers of deception, is the central one of the three seen above the bridge in our cut.

[3] The place of Chatterton's birth has been variously stated: Mr. Dix, in his "Life of Chatterton," has mentioned three. His first being that "he was born on the 29th of November, in the year 1752, in a house situated on Redcliff Hill, behind the shop now (1837) occupied by Mr. Hasell, grocer," and which has since been destroyed. But in the appendix to his volume is a communication stating that Mrs. Newton (Chatterton's married sister) left a daughter who "died in 1807, in the house where Chatterton was born; I believe in the arch at Cathay," a street leading from the church-yard to the river-side. But the most certain account seems to be that of Mrs. Edkins (also printed by Dix) who "went to school to Chatterton's father, and was present when the son was born, at the Pyle School." Now, as Chatterton was born about three months after his father's death, and he had been for some years master of the school, it is unlikely that his wife would be removed from the house she inhabited until after her confinement, "when," says Mrs. Edkins, "she went to a house opposite the upper gate on Redcliff Hill." The house appropriated to the master of Pyle Street School is shown in our engraving, it is at the back of the school, which faces the street, and is approached by an open passage on one side of it leading into a small court-yard, beyond which is a little garden. Over the door is inserted a stone, inscribed, "This house was erected by Giles Malpas, of St. Thomas Parish, Gent., for the use of the master of this School, A. D. 1749." The house has but two sitting rooms, one on each side of the door, that to the right being the kitchen; and in one of them the dissolute father of the Poet is said by Dix to have "often passed the whole night roaring out catches, with some of the lowest rabble of the parish." He was succeeded in the office of Schoolmaster by Edmond Chard, who held it for five years; and he was followed in 1757 by Stephen Love, who was master twenty-one years, and to whom Mrs. Chatterton first sent her son for education; and who, "after exhausting the patience of his schoolmaster, was sent back to his mother with the character of a stupid boy, and one who was absolutely incapable of receiving instruction."

[4] This School, founded in 1708 by Edward Colston, Esq., is situated in a street called St. Augustine's Back, behind the houses facing the drawbridge. It is the mansion in which Queen Elizabeth was entertained when she visited the city; and was purchased by Colston, because of its applicability to his charitable purposes. Here the scholars are boarded, lodged, and clothed, and are never permitted to be absent—except on Saturdays and Saints' days, from one till seven. They are simply taught reading, writing, and arithmetic. The school-room is on the first floor, and runs along the entire front of the building; the bed-rooms are the large airy rooms above. Behind the house is a paved yard for exercise. Chatterton remained here about seven years.

[5] The gate seen at the side of Colston's School in our cut, is that by which the school is entered; a narrow paved passage beside the house conducts to the angle of the building, when you turn to the left, and so reach the house by an open court-yard. In the corner of this angle, commanding a view of the entrance to the school, and also of the outer gate, is placed the doorkeeper's lodge delineated in our cut. It is a small building of brick, covered with lead, about six feet in height. It has within an iron seat, and an iron ledge for books. The windows are unglazed; and in winter it must be singularly uncomfortable, particularly as the occupant must traverse the length of the yard in all weathers. It is said to be the intention of the authorities to remove this little building; this is to be regretted, as it is almost the only unchanged memorial of her poet-boy which Bristol possesses. It was customary for the boys to take the office of doorkeeper in rotation for the term of one week; and it was in Chatterton's twelfth year, when he was doorkeeper, that he wrote here his first poem "On the Last Epiphany, or Christ coming to Judgment."

[6] Lambert's first office was on St. John's Steps; but the unceasing spirit of change, which has more or less destroyed all the Bristol localities connected with Chatterton, has swept this one away; "the Steps" have now been turned into a sloping ascent, and the old houses removed or renovated. Shortly after he had entered Lambert's service, his office was removed to Corn Street, and here, from the house delineated in our cut, he dated his first communication to Horace Walpole. It is immediately in front of the Exchange, and although the lower part has been altered frequently within remembrance, the upper part remains as when Lambert rented it. It may be noted, that the upper floors of the adjacent houses are still devoted to lawyers' and merchants' offices.

[7] The great Bristol merchant, William Canynge, jun., is buried in Redcliffe Church, to which he was a great benefactor, as he was to the city of Bristol generally. He entered the church to avoid a second marriage, and was made Dean of the College of Westbury, which he had rebuilt. There are two monuments to his memory in Redcliffe Church, both of which are seen in our engraving. One is a raised altar tomb with an enriched canopy; and upon the tomb lie the effigies of Canynge and his wife in the costume of the fifteenth century. The other tomb is of similar construction, and is believed to have been brought here from Westbury College; it represents Canynge in his clerical robes, his head supported by angels, and resting his feet on the figure of a Saracen. Here Chatterton frequently ruminated; indeed, the whole church abounds with memorials which call to mind the sources of his inspiration; near the door is an effigy inscribed "Johannes Lamyngton," which gave name to one of his forgeries. He was never weary of rambling in and about the church, and all his early works originated here.

[8] The muniment-room is a large low-roofed apartment over the beautiful north porch of Redcliffe Church, which was constructed by Canynge. It is hexagonal, and lighted by narrow unglazed windows. The floor rests on the groined stones of the porch, strong beams of oak forming its roof. It is secured by two massive doors in the narrow passage leading from the stairs into it. Here were preserved several large chests, and among them Canynge's cofre; from which Chatterton assured the world he had obtained the Rowley MSS.; and from which MSS. were carried away and destroyed, but the old chests still remain. There are seven in all, and they bear traces of great antiquity. Many have been strongly bound with iron, but all are now in a state of decay. This lonely cheerless room, strewn with antique fragments and suggestive of the boy-poet's day-dreams, is certainly the most interesting relic in Bristol. Its comfortless neglect is a true epitome of the life of him who first shaped his course from his reveries within it.

[9] The house said to be that of Canynge is situated in Redcliffe Street, not very far from the church. It is now occupied by a bookseller, who uses the fine hall seen in our cut, as a storehouse for his volumes. Chatterton frequently mentions this "house nempte the rodde lodge;" and in Skelton's "Etchings of Bristol Antiquities" is an engraving of this building, there called "Canynge's chapel or Masonic Hall," showing the painting in the arch at the back, representing the first person of the Trinity, supporting the crucified Saviour, angels at each side censing, and others bearing shields. This was "the Rood" with which Chatterton was familiar, and which induced him to give the name to Canynge's house in his fabrications. This painting is now destroyed, but we have restored it from Skelton's plate in our engraving.

[10] The monk Rowley was altogether an imaginary person conjured up by Chatterton as a vehicle for his wonderful forgeries. He was described by him as the intimate friend of Canynge, his constant companion, and a collector of books and drawings for him. It has been well remarked, that although it was extraordinary for a lad to have written them in the 18th century, it was impossible for a monk to have written them in the 15th. Indeed, it seems now both curious and amusing that his forgeries should have deceived the learned. When Rowley talks of purchasing his house "on a repayring lease for ninety-nine years." We at once smile, and remember his fellow-forger Ireland's Shaksperian Promissory note, before such things were invented. Our fac-simile of the pretended Rowley's writing is obtained from the very curious collection of Chatterton's manuscripts in the British Museum. It is written at the bottom of some drawings of monumental slabs and notes, stated to have been "collected ande gotten for Mr. William Canynge, by mee, Thomas Rowley." There are, however, other autographs of Rowley in the collection, so entirely dissimilar in the formation of the letters, that it might be expected to have induced a conviction of forgery. Many of the manuscripts too are still more dissimilar; and the construction of the letters totally unlike any of the period. Some are written on little fragments not more than three inches square, the writing sometimes neat and clean, at other times bad, rambling and unintelligible. The best is the account of Canynge's feast, which has been engraved in fac-simile by Strutt, to the edition of Rowley's Poems, 1777. The writing is generally bolder than Barrett's fac-simile; and that gentleman, in endeavoring to revive the faded ink, has greatly injured the originals, which are now in some cases almost indistinguishable. The drawings of pretended ancient coins and heraldry are absurdly inventive: and the representations of buildings exactly such as a boy without knowledge of drawing or architecture would fabricate; yet they imposed on Barrett who engraved them for his history of Bristol. Many of his transcripts show the shifts the poor boy was put to for paper; torn fragments and backs of law bills are frequently employed. Among the rest is a collection of extracts from Chaucer to aid him in the fabrication of his MSS. The whole is exceedingly instructive and curious.

[11] This gentleman was the proprietor of the "Bristol Journal," to which Chatterton sent his first forgery; and with whom he afterwards became intimate.

[12] The cenotaph erected to Chatterton, in 1838, from a design by S. C. Fripp, has now been removed; it stood close to the north porch, beside the steps leading into it. One of the inscriptions, which he directs in his will to be placed on his tomb, has been adopted. "To the Memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader, judge not, if thou art a Christian. Believe that he shall be judged by a superior Power. To that Power alone is he now answerable."

Of personalities, &c. a few words: Every man or woman coming before the public voluntarily—especially every man or woman placing his or her name upon the title of a book—submits so much of his or her being and character to the general criticism. It is crime to make public use of private conversation; it is crime, under most circumstances, to disclose the secret of an anonymous authorship; it is crime in all cases to invade any privacy, or comment on any purely personal matter, that has not by the interested party been offered for the world's examination. If any one publish a work of pure art, it is entirely inexcusable to suggest any illustrations of it from his life or condition, unless by his own express or implied permission. For example, if "The Princess," by Tennyson, had been printed anonymously by some notorious thief, burglar, forger, or murderer, he would be as great a villain as the author, who, in reviewing the poem, should in any manner whatever allude to the author's sins. The extent to which this law may be applied can easily be understood. To a gentleman the law itself is an instinct. Personal rights are frequently violated by praise as well as by censure, and sometimes applause is not in any degree less offensive than denunciation, though commonly men will forgive even the most unskilful and injudicious commendation. In both ways the writers of this country are apt to err.

While we agree with the most fastidious, in asserting that inviolability of one's individualism, not by himself submitted for public observation, we contend for the right and duty of the utmost freedom in the dissection of what is thus submitted. Public speech, public action, public character, are adventures upon the sea of the world's opinion, and they must brave its winds or be sunk or wrecked by them,—the person, so far as he is not involved, meanwhile safely watching from the shore for results.

In the most careful applications of this principle, it is inevitable that wrong is done sometimes; but when the wrong is not personal, it is for the most part susceptible of remedy. The author may challenge investigation of his book, the artist of his picture, the officer of his administration. If there has been unfair severity of criticism, they are likely to gain by it in the end, for every critic must justify upon challenge.

There is a distinction in the cases of the[Pg 298] dead. The world in an especial manner becomes the heir of a life which is abandoned by its master. This has been held by the wise in all ages and all states of society. The justice of the distinction is very apparent: An invasion of the individualism of the living destroys, or to a greater or less extent affects, the freedom, and so the right and wrong, of his conduct, while the secrets of the dead are to the living only as logic.

There are very few men who are not more willing to praise than to blame. The better portion of men prefer to hear the praises even of strangers. Therefore censors are held to stricter account than eulogists. But a natural love of justice is continually at war with feelings of personal kindness. It is impossible to see insolent and vulgar pretension in noisy triumph, while real and unobtrusive merit is neglected. When we see a creature strutting in laurels that have been won by another, human nature—much as it has been abused—prompts us to grasp them from undeserving brows and place them where they will have a natural grace. For trite examples, who would not rather elect Columbus than Americus to the place of Name-Giver for this continent? who does not rejoice that finally Hadley is proved a swindler of the fame of Godfrey, in the matter of the quadrant? How many such wrongs do men daily hope to see righted!

The writer of these paragraphs will never willingly violate the just conditions of criticism. If he offers, as often is necessary, conclusions rather than arguments, he will in no case withhold arguments when conclusions are held to be unjust. The true value of every sort of journalism, and of discussion also, is in its integrity much more than in its ability. Integrity is violated as much by the suppression of truth as by the suggestion of falsehood. In all cases that interest us sufficiently, and which are legitimately before the public, we shall write precisely as we think, without the slightest regard for consequences.

Oersted, the great natural philosopher, has lately published at Leipzic, under the title of Der in Geist in der Natur (Spirit in Nature), a collection of remarkable essays which he has written, at various times, during a series of years. The purpose he has followed through his entire scientific career, has, perhaps, its most complete expression in this book. It is the demonstration of the same laws in physical nature as in the higher spheres of the reason and intelligence. On the principle of the essential unity of all things, he seeks not only to lay the foundation of a universal science, but to afford some views of the superstructure. The work contains eight distinct essays: the first, "The Spiritual in the Corporeal," is in the form of a Dialogue, and aims at a reconciliation of the conflicting modes of thought, by which the universe is assumed to be essentially material, or essentially spiritual; the second, "The Fountain," treats of the impressions of beauty produced by the great, sublime, and powerful; the third considers the relation to the imagination, of the apprehension of nature by the understanding, and shows that it is only imperfect culture and ignorance which can suppose any dissonance between the two. He shows that the progress of science enriches, aggrandizes, and elevates the imagination. The fourth essay is, perhaps, the most interesting of all. Its theme is, "Superstition and Skepticism in their relation to Natural Science." The notion that superstition is favorable to poesy, he dissipates with masterly conclusiveness. The true realm of beauty is the realm of reason. It is true that science deprives the poet of the use of sundry unnatural conceptions, but while it more than compensates him by the substitution of nobler ideas, it opens to him a new, affluent, and little explored poetic world. "It can," he says, "not be charged as a crime upon natural science, that it has destroyed materials hitherto used by the poets. Such losses are of small consequence to the true poet, but may, indeed, be painful to the many dabblers in the poetic art, who think they have rendered the insignificant poetic by tricking it out in gewgaws from the poetic armory of a vanished era." The fifth, entitled, "The Existence of all things in the Domain of Reason," is the profoundest and most significant of these essays, and more than the others brings out in form as simple and popular as could be expected, the fundamental idea of the author's system of thought. It asserts that there is, throughout the universe, a radical unity between the laws of beauty, and man's moral nature and intellectual powers, and that there must therefore exist for the mind, a perfect community of nature and analogy between different worlds, and a rational connection between all thinking beings, not only of the earth, but of other planets and systems. The final essay is on "The Culture of Science as the Exercise of Religion," and is mainly an attempt to show that the very nature of science requires its culture to be made a religion, and that the good which we ought to seek must be that which is imperishable in its truth.

This work has been rapidly followed by two other publications of the same author, intended to explain or defend the positions of their predecessor. The first is called, "Natural Science in its Connection with Poetic Art and Religion." It was written in reply to the criticism of a learned and respected friend of the author, Bishop Mynster of Seeland. The second has for its title, "Natural Science and the Formation of the Intellect."

Oersted is now seventy-three years old. It is admirable to see a man of such years and distinction in the world, putting forth the same grand and elevated ideas that marked the generous enthusiasm of his youth. It is only in the genial and unselfish pursuits of science that such freshness of mind can be thus preserved.[Pg 299]

New Dramas.—Among the new dramas of any value, produced in Germany, Herodes und Mariamne, a five act tragedy, by Hebbel, deserves particular mention. The persons are too numerous, and the action too complicated, but there is great fire and energy in the general treatment, and the gradual development of the interest of the story is managed with skill. Herod, the ruler of Judea, is a tyrant by both nature and position. He was appointed to his office by the Roman triumvir Antony, who can turn him out or cut his head off at any moment, and who is strongly inclined to follow the urgent solicitations of Herod's many enemies. In order to secure himself, Herod has married Mariamne, a descendant of the Jewish royal family, and is deeply in love with her. The chief of his foes is Mariamne's mother; the Pharisees also hate him for his notorious disregard of the Jewish religion. A conspiracy is formed against him, at the head of which is the brother of Mariamne. This brother is killed in consequence, and Herod is summoned before the triumvir. Meanwhile, as soon as the murder was known, Mariamne had refused to see her husband. But the evidences of his attachment are still so convincing, and her admiration for the force of his character so great, that she becomes reconciled to him. He is about to leave her to appear before Antony, and asks if her love is great enough for her to commit suicide, in case he should not return. Finally he asks her to take an oath to that effect. But she refuses, saying that such an oath would give him no pledge that he might not have already from insight into her heart. He is not content with this, and before he leaves, engages an assassin to kill her in case Antony should put him to death. After his departure, Mariamne declares to her mother that in case Herod perishes, she has determined to kill herself. The report arrives that he has been executed; and the assassin appears; from his bearing Mariamne guesses the truth, and draws from him a confession. Just as she is in the deepest agitation at this discovery, the king appears, having been acquitted by Antony. She meets him with coldness, and at once lets him know that she has learned all. He puts to death the man, but at the same time a suspicion arises in his mind that Mariamne has discovered the secret by betraying her honor. Against this her pride will not allow her to defend herself. A second trial soon arrives. Herod receives the order—shortly before the battle of Actium—to go on a dangerous military expedition for Antony. He now requires no oath, at which she rejoices; for she still loves him, and forgives him for the past. But she does not reveal herself to him. He misunderstands the joy which she cannot conceal, as satisfaction at his departure, and charges a faithful servant to put her to death in case he shall fall. The report of his death is renewed, but the appointed assassin, revolted at his office, discloses all to Mariamne. This drives her to despair. She is confident that her husband will soon return, and determines that he shall be led to put her to death unjustly. Accordingly she gives a splendid feast, as she says, to celebrate the death of her husband. He comes and brings her before a court, not for having rejoiced at his death, but for infidelity, supposing that to be the only way in which she could have discovered the secret of the assassin. She is condemned and executed, but before dying, she reveals the whole mystery to a friend, who afterwards informs Herod. The king devoured by rage and remorse and driven to desperation, becomes merciless as a fury. It is at that moment, that the three wise men from the East arrive, and inform him of the birth of Christ; whereupon he orders the slaughter of the children. One of the peculiarities of this tragedy, is the introduction of a character, who takes no part in the action, but observes and philosophizes upon it, somewhat after the manner of the old Greek chorus. This innovation cannot be said to be successful; moreover there is generally too much philosophizing and moralizing in the piece.

Another new German tragedy is called Francisco da Rimini, by Cornelius Von der Heyse, but we know nothing more respecting it than is communicated by the publisher's advertisement. The title is promising.

The French dramatists produce more comedies than tragedies. Indeed, in the weekly notices which for the last few weeks our Parisian papers have given of the new works brought out at the various theatres of Paris, we have not observed one tragedy of importance enough for us to remark upon it. But in the lighter range of comedy, the French playwrights are unequalled and inexhaustible, as is proved by the constant transfer of their productions into both the English and German languages. They do not think it necessary to have a plot of much intricacy, or even of great interest. The point and brilliancy of the dialogue, and the perfection of the actors, render that a matter of subordinate consequence. The Two Eagles, by Bayard and Bieville (these partnerships are frequent among the dramatists of Paris), was brought out at the Théâtre Montansier. Hippolyte Vidoux, clerk in a cap store and lieutenant in the National Guards, is a charming fellow, and the idol of the women in the whole quarter. He sings, jokes, and dances the polka in every style. He is introduced into the salons of his superior officer, Count Chamaral, but meets with no sort of success among the marchionesses and duchesses. On the other hand, these ladies are dying for the young Baron Albert, who dances the contra-dance with a mien of languishing resignation worthy of a funeral. The Baron falls in love with the daughter of a rich baker, but in vain. Here Hippolyte carries off the honors and the heiress according to the French proverb, the eagle of one house is a turkey in another. At the Opera Comique, a piece in one act, The Peasant, by Alboize, music by[Pg 300] Poisat is one of the latest novelties. A proud and obstinate German Baron refuses his daughter's hand to her lover, whose great merit nevertheless causes him to be ennobled. Still the Baron refuses his daughter. "What!" he says, "shall I marry my child to a new-baked nobleman?" But as good luck would have it, the Emperor Joseph happens along in disguise, on one of his excursions for relieving virtue and unmasking vice. The Baron receives him, but has nothing to set before him. Hereupon a gardener furnishes a deer, which saves the honor of the house. The Emperor is delighted with the venison, and makes the donor sit down at the table. He is the father of the suitor, and as he has thus had the honor to eat with the Emperor, the Baron can say nothing more against the marriage. The good Emperor blesses the happy pair, and sets off again to see if there are no more comic operas in his dominions to which he can contribute a happy denouement. At the Théâtre des Variétés has been produced the Ring of Solomon, in one act, by Henry Berthoud. The scene is laid in Holland, in the winter, which affords an excellent opportunity to the scene-painter and property-man. Threa, a poor and silly girl, is so passionately in love with Hans, who has saved her from death, that she climbs a wall to see him as he is going by. The wall tumbles down with her, and among the fragments she finds the ring of Solomon, and puts it on. At once she is surrounded by fairies, in the well-known ballet costume, who carry her off into a Dutch paradise, where she also becomes a fairy, and undergoes a remarkable improvement in her wits. But this does not bring any change in her passion for Hans, and she prefers to be unhappy with him to floating for ever through the aerial joys of fairydom without him. Accordingly, she renounces the privilege conferred on her by the ring, and is rewarded for so much virtue by passing through a new transformation, after which she appears as a most lovely peasantess, and marries Hans to the universal satisfaction.

German Novels.—The bookstores of Germany now swarm with new novels, some of which we have already noticed. Modern Titans: Little People in a Great Epoch, from the press of Bookhaus, seems to be written with the express purpose of introducing all the notabilities of Berlin, Breslau and Vienna, and is not successful. The name of the author is not given. Der Tannhausen treats of suicide, republicanism, the identity of God and the universe, faith, skepticism, Christ, marriage, the emancipation of woman, and whatsoever new-fangled and startling ideas and phrases the author has met with in the activity of this busy age. This book is also charged with outrageous personalities. George Volker, a Romance of the year 1848, by Otto Müller, 3 vols., is of course, a revolutionary story. The hero is so unfortunate as to be in love with two women at a time, the one a country, and the other a peasant girl. He engages in the Badian insurrection, is about to be arrested, and thereupon gets out of all his difficulties by shooting himself. Der Sohn des Volkes, by Leoni Schucking, takes its subject and plot from the French Revolution and its influence on Germany. It is written with talent, and is altogether in the interest of the aristocracy. Der Bettler von James's Park (the Beggar of James's Park), by Alexander Jung, is not revolutionary but tragic and sentimental. At the same time, it is didactic, and sets forth sundry ideas with reference to love, God, and liberty. But the story deserves more than a line in these columns, were it only as a literary curiosity. The hero is haunted by the notion that a great misfortune will fall upon his family, whenever a travelling dealer shall offer an ecce homo for sale to any one of its members. Unluckily, such a picture is offered to himself, and he almost loses his wits at it. Hereupon he goes to see the young lady with whom he is in love, and finds her dying. This quite upsets him, and he goes crazy, and, in this condition, becomes a beggar in the London streets. At the beginning, he is very lean, and is so well suited to this trade, that he is even made a member of the beggars' guild. But ill luck still pursues him; he becomes excessively fat, and gains a belly of most aldermanic proportions. Here a lord takes him up as an object at once of study and philanthropy, but not with sufficient interest in him to provide for his support. Alms he gets none; next, he is turned out of the guild, and, at last, is taken to a hospital, where he loses his flesh, and regains his reason. Finally, after passing through a variety of other strange experiences, he dies in tranquillity, wept by the same lord, and by the lady he had himself supposed to be dead; but who, instead of this, had become a nun in France. Schnock, a picture of life in the Netherlands, is by Frederich Hebbel, a man of some distinction, as a dramatic writer, as we have noticed elsewhere. The general idea of this book is borrowed from Jean Paul's Journey of the Chaplain Schmelzle. The hero is a man of weak and timid character, married to a woman of unsparing energy and resolution. The style and execution of the work are clumsy, exaggerated and abominable. Handel und Wandel (Doings and Viewings), by Hackländer, is worthy of all praise, as a faithful and vivid picture of German rural and domestic life. The characters are all human, the action simple and direct, and the tone healthy and agreeable. Hackländer is an exception to the mass of modern German novelists, of whom, taking them together, as may be judged from the brief remarks above, no great good can be said.

Ein Dunkles Loss (A Dark Destiny), by L. Bechstein, is a socialist book, which, in the form of a novel, discusses questions relating to art, not without genuine insight and original power of thought.[Pg 302]

The Countess Hahn-Hahn, the bravest and decidedly the cleverest of the women who have written books of Oriental travel, and whose "latitudinarian" novels constitute a remarkable portion of the recent romantic literature of Germany, we perceive has entered a convent. The Ladies' Companion exclaims hereof:—

"When will the wild and the restless learn self-distrust from the histories of kindred spirits? And, observing how the pendulum must vibrate (as in Madame Hahn-Hahn's case) from utter disdain of social laws, to the most superstitious form of association under authority—how, almost always, to defiance must succeed a desire for reconciliation. When will they become chary of pouring out their laments, their attacks, their complaints, seeing that similar protestations are almost certainly followed by after repentance and recantation!"

The Countess Hahn-Hahn unfortunately has but one eye, and she is otherwise astonishingly ugly. So we may account for a very large proportion of the eccentricities of the sex. Had she been in this country she would have presided at the late Woman's Rights Convention.

No modern man has been more written about than Goethe, and the end of books concerning him seems to be still distant. The last that we hear of is called Goethe's Dichterwerth (Value of Goethe as a Poet), written by O. L. Hoffman, and published in the quaint old city of Nuremberg. It treats first of the poet's relation to natural science, art and society: next takes up the complaints of his antagonists; his poetic character; his youthful productions; his lyrics; Götz von Berlichingen; the Sorrows of Werter; the influence of Italy on his mature mind; Egmont; Iphigenia at Tauris; Tasso; the influence of the French Revolution; his relations with Schiller; his Ballads; Hermann and Dorothea; the Natural Daughter; Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship; and finally the productions of his mature years, as Wilhelm Meister's Wander-years, the Elective Affinities, and Faust. The work forms a complete commentary on the works of Goethe, and is written in the warmest spirit of admiration for his genius and influence.

Hagen's Geschichte der Neuesten Zeit (History of Recent Times) is worthy a place in the library of every historical student. It begins with the downfall of Napoleon and is to come down to the present day. The first volume has been published; it exhibits thorough mastery of the materials, and great calmness and judgment in their use. The style is clear, terse and graphic. The author, who is a professor of the University of Heidelberg, is a decided republican.

Cotta's splendid illustrated edition of the Bible (Luther's version) is now finished. It is perhaps the best Illustrated Bible ever published. The typography and woodcuts are admirable. Of the latter there are eighty, after original designs by Jäger, Overbeck, Schnorr, and others.

Fallermayer, the distinguished German traveller, is about abandoning the fruitless polemics which have gained him so many foes, to devote himself to more useful labors. He himself desires to be at peace with all the world, and the antagonists which his trenchant pen has so often unsparingly scarified, need fear him no longer. He is about to complete and print the third volume of his Oriental Impressions of Travel. This is reason for rejoicing. Fallermayer is one of the most charming and instructive of travel-writers.

Wallon's Histoire de l'Esclavage dans l'Antiquite, just published at Paris, is a work of high value to those who wish to look into a branch of history hitherto comparatively little cultivated, but destined to attract the most profound attention. M. Wallon, who is one of the candidates for the vacant seat in the French Academy, discusses in an exhaustive manner the origin of slavery in the antique world, the condition of bondmen in the various nations, and the gradual development of the institution under all circumstances and in all countries. His book is excellent for its manner, while in respect of matter the author has drawn information from all accessible sources, and digested it with judgment and impartiality. Thus he has produced a worthy contribution to that great but yet unwritten work, so full of both tragic and epic elements, the Annals of Labor. What a noble book might be made by some competent writer who should grapple with the whole subject.

The Narrative of the United States South Sea Exploring Expedition, is being translated into German, and published by Cotta of Stuttgard. The second volume is just completed. Probably all the supplementary volumes, as Hale's "Ethnology," and Pickering's "Races of Men," will follow.

Miss Barbauld's "God in Nature" has been translated into German by Thecla von Gaupert, and illustrated by that most fertile and charming of designers, Louis Richter. The translation is made from the thirtieth English edition, and the price put within the reach of the poorer classes, at fifty cents.

Frederic Bodenstedt, the author of the successful book on the Wars of the Circassians, has just published the conclusion of a new work, called "A Thousand and One Days in the Orient."

A collection of Hungarian Mythical Traditions and Fairy Tales, has lately been published in German at Berlin, translated from the Magyar of Erdily, by G. Stier.

The first part of the third and last volume of Humboldt's Cosmos has been published at Stuttgart. It is on the Fixed Stars, and makes a pretty stout book.[Pg 303]

Humboldt, having furnished for his friend, Dr. Klencke, materials for a memoir of his life, such a work was announced at Berlin, and so great was the interest excited by its advertisement, that before the first edition was all printed a second one was commenced.

Dr. Karl August Espe, who for many years has filled the post of editor to Brockhaus's Conversations-Lexicon, the work which forms the basis of the Encyclopedia Americana, died near Leipzic on the 25th November last. He was a man of great acquirements and unwearied industry, and was well known and esteemed in the literary and scientific circles of the continent. He was born at Kühren, in 1804, and went to Leipzic in 1832. Beside the great work above alluded to, he had charge of the annual memoirs of the German Society for the study of the native language and antiquities. Nearly two years ago he was attacked by a fit of apoplexy, from the effect of which his mind did not recover. He has since been in a lunatic asylum.

Neander's Church History is printed as far as the year 1294. He had continued the work in manuscript up to the beginning of the fifteenth century, so that Wiclif, Huss, and other important precursors of the Reformation have found a place in it. This last volume of this great work will shortly be printed. Neander's various posthumous works are of remarkable value, though very few of them are in a finished state. According to the Methodist Quarterly, always well informed upon such matters, his exegetical Lectures upon the New Testament are of even greater merit than his compositions in history. They are soon to be published at Berlin, from notes taken by his students.

Neander's Practical Expositions of St. James and of St. Paul's Epistle to the Philippians, are in process of translation by Mrs. H. C. Conant, the wife of Professor Conant, of Hamilton, and one of the most accomplished women in this country. A translation of Hagenbach's Kirchengeschichte des 18 und 19 Jahrhunderte, may also be expected from the same hand, and so will be done admirably.

Schleiermacher's "Brief Outline of the Study of Theology" has been translated by Rev. W. Farrar, and published by Clark, of Edinburgh, in a single duodecimo.

Dr. Karl Zimmermann has edited and published, at Darmstadt, "The Reformatory Writings of Martin Luther, in chronological order, with a Biography of Luther," in four volumes.

Two new volumes of L'Encyclopédie du Dixneuvième Siècle have just appeared at Paris. Geoffroy St. Hilaire, Becquerel, Buchez, Delescluze, Michel Chevalier, Philarete Chasles, and other literary and scientific notabilities are among the contributors.

The house of Didot, at Paris, have just issued a most interesting volume of the great work they have for some time been publishing under the title of L'Univers Pittoresque. This volume is occupied with Japan, the Burman Empire, Siam, Anam, the Malay peninsula, and Ceylon. The letter-press is furnished by Col. Jancigny, who was formerly aid-de-camp to the King of Oude, and has a thorough personal acquaintance with the countries in question. To show how great is the multitude of elephants in Ceylon, Col. J. speaks of an English officer who resided there, and who had with his own hand killed above two thousand of these monsters. The book, like all the rest of the series, is illustrated by numerous engravings. The series is to consist of forty-five volumes. Only one or two are now wanting to complete it. It is intended to afford a complete description of all the countries, nations, religions, customs, manners, &c. of the world.

M. Nisard has been elected a member of the Académie Française, in the room of the late M. Droz. He is known to the public chiefly by his translations of the Roman writers, poetical and prose, and by sundry able critical papers in the Revue des Deux Mondes. Opposing candidates were Beranger, Alfred Musset, Jules Janin, Dumas, and others. Another vacancy was to be filled in January, and among the candidates were President Bonaparte, and the Count Montalembert, who are certainly more conspicuous in politics than in letters, though one did write a book on gunnery, and the other one on Elizabeth of Hungary.

Two collections of interesting and valuable official documents have just been given to the Parisian public. One is called Archives des Missions Scientifiques et Littéraires, and consists of the most remarkable reports sent to the Government by travellers charged with scientific and literary missions. The other is the Bulletin des Comités Historiques, and embraces articles relative to history, science, literature, archæology, and the fine arts. It is issued by the Committee of the written Monuments of the History of France, and the Committee of Arts and Monuments. The most eminent names of French science and literature are among the contributors to these works.

M. Ginoux, who was sent by Guizot on a scientific mission which required him to traverse the globe, but who was recalled by the government of General Cavaignac, has returned to Paris, having been absent several years. He will soon publish the narrative of his travels, which have been in Oceanica, Polynesia, Brazil, Patagonia, Chili, Bolivia, Peru, Equador, New Grenada, Jamaica, Cuba, and the United States.

Beranger, at the last dates was, and for several weeks had been, dangerously ill, at his house at Passy.[Pg 304]