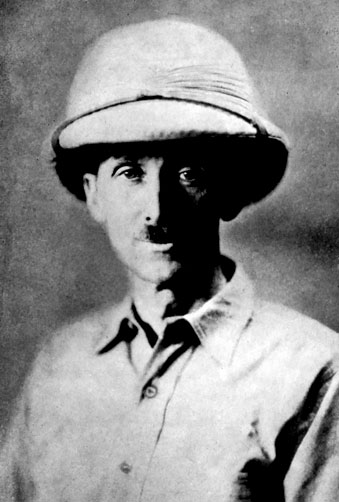

WILLIAM BEEBE

WILLIAM BEEBEAuthor of Edge of the Jungle, Jungle Days, Gallapagos, World's End, The Arcturus Adventure, etc.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Edge of the Jungle, by William Beebe This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Edge of the Jungle Author: William Beebe Release Date: June 24, 2008 [EBook #25888] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EDGE OF THE JUNGLE *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Mark C. Orton, Linda McKeown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

WILLIAM BEEBE

WILLIAM BEEBE

This second series of essays, following those in Jungle Peace, are republished by the kindness of the Editors of The Atlantic Monthly, Harper's Magazine and House and Garden.

With the exception of A Tropic Garden which refers to the Botanical Gardens of Georgetown, all deal with the jungle immediately about the Tropical Research Station of the New York Zoological Society, situated at Kartabo, at the junction of the Cuyuni and Mazaruni Rivers, in British Guiana.

For the accurate identification of the more important organisms mentioned, a brief appendix of scientific names has been prepared.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I | The Lure of Kartabo | 3 | |

| II | A Jungle Clearing | 34 | |

| III | The Home Town of the Army Ants | 58 | |

| IV | A Jungle Beach | 90 | |

| V | A Bit of Uselessness | 112 | |

| VI | Guinevere the Mysterious | 123 | |

| VII | A Jungle Labor Union | 149 | |

| VIII | The Attas at Home | 172 | |

| IX | Hammock Nights | 195 | |

| X | A Tropic Garden | 230 | |

| XI | The Bay of Butterflies | 252 | |

| XII | Sequels | 274 | |

| Appendix of Scientific Names | 295 | ||

| Index | 299 |

A house may be inherited, as when a wren rears its brood in turn within its own natal hollow; or one may build a new home such as is fashioned from year to year by gaunt and shadowy herons; or we may have it built to order, as do the drones of the wild jungle bees. In my case, I flitted like a hermit crab from one used shell to another. This little crustacean, living his oblique life in the shallows, changes doorways when his home becomes too small or hinders him in searching for the things which he covets in life. The difference between our estates was that the hermit crab sought only for food, I chiefly for strange new facts—which was a distinction as trivial as that he achieved his desires sideways and on eight legs, while I traversed my environment usually forward and generally on two.

The word of finance went forth and demanded the felling of the second growth around Kalacoon,[4] and for the second time the land was given over to cutlass and fire. But again there was a halting in the affairs of man, and the rubber saplings were not planted or were smothered; and again the jungle smiled patiently through a knee-tangle of thorns and blossoms, and the charred clumps of razor-grass sent forth skeins of saws and hanks of living barbs.

I stood beneath the familiar cashew trees, which had yielded for me so bountifully of their crops of blossoms and hummingbirds, of fruit and of tanagers, and looked out toward the distant jungle, which trembled through the expanse of palpitating heat-waves; and I knew how a hermit crab feels when its home pinches, or is out of gear with the world. And, too, Nupee was dead, and the jungle to the south seemed to call less strongly. So I wandered through the old house for the last time, sniffing the agreeable odor of aged hypo still permeating the dark room, re-covering the empty stains of skins and traces of maps on the walls, and re-filling in my mind the vacant shelves. The vampires had returned to their chosen roost, the martins still swept through the corridors, and as I went down the hill, a moriche oriole sent a silver shaft of[5] song after me from the sentinel palm, just as he had greeted me four years ago.

Then I gathered about me all the strange and unnameable possessions of a tropical laboratory—and moved. A wren reaches its home after hundreds of miles of fast aerial travel; a hermit crab achieves a new lease with a flip of his tail. Between these extremes, and in no less strange a fashion, I moved. A great barge pushed off from the Penal Settlement, piled high with my zoölogical Lares and Penates, and along each side squatted a line of paddlers,—white-garbed burglars and murderers, forgers and fighters,—while seated aloft on one of my ammunition trunks, with a microscope case and a camera close under his watchful eye, sat Case, King of the Warders, the biggest, blackest, and kindest-hearted man in the world.

Three miles up river swept my moving-van; and from the distance I could hear the half-whisper—which was yet a roar—of Case as he admonished his children. "Mon," he would say to a shirking, shrinking coolie second-story man, "mon, do you t'ink dis the time to sleep? What toughts have you in your bosom, dat you delay de Professor's household?" And then a chanty[6] would rise, the voice of the leader quavering with that wild rhythm which had come down to him, a vocal heritage, through centuries of tom-toms and generations of savages striving for emotional expression. But the words were laughable or pathetic. I was adjured to

Or the jungle reëchoed the edifying reiteration of

The thrill that a whole-lunged chanty gives is difficult to describe. It arouses some deep emotional response, as surely as a military band, or the reverberating cadence of an organ, or a suddenly remembered theme of opera.

As my aquatic van drew up to the sandy landing-beach, I looked at the motley array of paddlers, and my mind went back hundreds of years to the first Spanish crew which landed here, and I wondered whether these pirates of[7] early days had any fewer sins to their credit than Case's convicts—and I doubted it.

Across my doorstep a line of leaf-cutting ants was passing, each bearing aloft a huge bit of green leaf, or a long yellow petal, or a halberd of a stamen. A shadow fell over the line, and I looked up to see an anthropomorphic enlargement of the ants,—the convicts winding up the steep bank, each with cot, lamp, table, pitcher, trunk, or aquarium balanced on his head,—all my possessions suspended between earth and sky by the neck-muscles of worthy sinners. The first thing to be brought in was a great war-bag packed to bursting, and Number 214, with eight more years to serve, let it slide down his shoulder with a grunt—the self-same sound that I have heard from a Tibetan woman carrier, and a Mexican peon, and a Japanese porter, all of whom had in past years toted this very bag.

I led the way up the steps, and there in the doorway was a tenant, one who had already taken possession, and who now faced me and the trailing line of convicts with that dignity, poise, and perfect self-possession which only a toad, a giant grandmother of a toad, can exhibit.[8] I, and all the law-breakers who followed, recognized the nine tenths involved in this instance and carefully stepped around. When the heavy things began to arrive, I approached diffidently, and half suggested, half directed her deliberate hops toward a safer corner. My feelings toward her were mingled, but altogether kindly,—as guest in her home, I could not but treat her with respect,—while my scientific soul revelled in the addition of Bufo guttatus to the fauna of this part of British Guiana. Whether flashing gold of oriole, or the blinking solemnity of a great toad, it mattered little—Kartabo had welcomed me with as propitious an omen as had Kalacoon.

Houses have distinct personalities, either bequeathed to them by their builders or tenants, absorbed from their materials, or emanating from the general environment. Neither the mind which had planned our Kartabo bungalow, nor the hands which fashioned it; neither the mahogany walls hewn from the adjoining jungle, nor the white-pine beams which had known many decades of snowy winters—none of these were obtrusive. The first had passed into oblivion,[9] the second had been seasoned by sun and rain, papered by lichens, and gnawed and bored by tiny wood-folk into a neutral inconspicuousness as complete as an Indian's deserted benab. The wide verandah was open on all sides, and from the bamboos of the front compound one looked straight through the central hall-way to bamboos at the back. It seemed like a happy accident of the natural surroundings, a jungle-bound cave, or the low rambling chambers of a mighty hollow tree.

No thought of who had been here last came to us that first evening. We unlimbered the creaky-legged cots, stiff and complaining after their three years' rest, and the air was filled with the clean odor of micaceous showers of naphthalene from long-packed pillows and sheets. From the rear came the clatter of plates, the scent of ripe papaws and bananas, mingled with the smell of the first fire in a new stove. Then I went out and sat on my own twelve-foot bank, looking down on the sandy beach and out and over to the most beautiful view in the Guianas. Down from the right swept slowly the Mazaruni, and from the left the Cuyuni, mingling with one wide expanse like a great rounded lake, bounded by[10] solid jungle, with only Kalacoon and the Penal Settlement as tiny breaks in the wall of green.

The tide was falling, and as I sat watching the light grow dim, the water receded slowly, and strange little things floated past downstream. And I thought of the no less real human tide which long years ago had flowed to my very feet and then ebbed, leaving, as drift is left upon the sand, the convicts, a few scattered Indians, and myself. In the peace and quiet of this evening, time seemed a thing of no especial account. The great jungle trees might always have been lifeless emerald water-barriers, rather than things of a few centuries' growth; the ripple-less water bore with equal disregard the last mora seed which floated past, as it had held aloft the keel of an unknown Spanish ship three centuries before. These men came up-river and landed on a little island a few hundred yards from Kartabo. Here they built a low stone wall, lost a few buttons, coins, and bullets, and vanished. Then came the Dutch in sturdy ships, cleared the islet of everything except the Spanish wall, and built them a jolly little fort intended to command all[11] the rivers, naming it Kyk-over-al. To-day the name and a strong archway of flat Holland bricks survive.

In this wilderness, so wild and so quiet to-day, it was amazing to think of Dutch soldiers doing sentry duty and practising with their little bell-mouthed cannon on the islet, and of scores of negro and Indian slaves working in cassava fields all about where I sat. And this not fifty or a hundred or two hundred years ago, but about the year 1613, before John Smith had named New England, while the Hudson was still known as the Maurice, before the Mayflower landed with all our ancestors on board. For many years the story of this settlement and of the handful of neighboring sugar-plantations is one of privateer raids, capture, torture, slave-revolts, disease, bad government, and small profits, until we marvel at the perseverance of these sturdy Hollanders. From the records still extant, we glean here and there amusing details of the life which was so soon to falter and perish before the onpressing jungle. Exactly two hundred and fifty years ago one Hendrik Rol was appointed commander of Kyk-over-al. He was governor, captain,[12] store-keeper and Indian trader, and his salary was thirty guilders, or about twelve dollars, a month—about what I paid my cook-boy.

The high tide of development at Kartabo came two hundred and three years ago, when, as we read in the old records, a Colony House was erected here. It went by the name of Huis Naby (the house nearby), from its situation near the fort. Kyk-over-al was now left to the garrison, while the commander and the civil servants lived in the new building. One of its rooms was used as a council chamber and church, while the lower floor was occupied by the company's store. The land in the neighborhood was laid out in building lots, with a view to establishing a town; it even went by the name of Stad Cartabo and had a tavern and two or three small houses, but never contained enough dwellings to entitle it to the name of town, or even village.

The ebb-tide soon began, and in 1739 Kartabo was deserted, and thirty years before the United States became a nation, the old fort on Kyk-over-al was demolished. The rivers and rolling jungle were attractive, but the soil was poor, while the noisome mud-swamps of the coast proved to be fertile and profitable.[13]

Some fatality seemed to attach to all future attempts in this region. Gold was discovered, and diamonds, and to-day the wilderness here and there is powdering with rust and wreathing with creeping tendrils great piles of machinery. Pounds of gold have been taken out and hundreds of diamonds, but thus far the negro pork-knocker, with his pack and washing-pan, is the only really successful miner.

The jungle sends forth healthy trees two hundred feet in height, thriving for centuries, but it reaches out and blights the attempts of man, whether sisal, rubber, cocoa, or coffee. So far the ebb-tide has left but two successful crops to those of us whose kismet has led us hither—crime and science. The concentration of negroes, coolies, Chinese and Portuguese on the coast furnishes an unfailing supply of convicts to the settlement, while the great world of life all about affords to the naturalist a bounty rich beyond all conception.

So here was I, a grateful legatee of past failures, shaded by magnificent clumps of bamboo, brought from Java and planted two or three hundred years ago by the Dutch, and sheltered by a bungalow which had played its part in the[14] development and relinquishment of a great gold mine.

For a time we arranged and adjusted and shifted our equipment,—tables, books, vials, guns, nets, cameras and microscopes,—as a dog turns round and round before it composes itself to rest. And then one day I drew a long breath and looked about, and realized that I was at home. The newness began to pass from my little shelves and niches and blotters; in the darkness I could put my hand on flash or watch or gun; and in the morning I settled snugly into my woolen shirt, khakis, and sneakers, as if they were merely accessory skin.

In the beginning we were three white men and four servants—the latter all young, all individual, all picked up by instinct, except Sam, who was as inevitable as the tides. Our cook was too good-looking and too athletic to last. He had the reputation of being the fastest sprinter in Guiana, with a record, so we were solemnly told, of 9-1/5 seconds for the hundred—a veritable Mercury, as the last world's record of which I knew was 9-3/5. His stay with us was like the orbit of some comets, which make a single lap around the[15] sun never to return, and his successor Edward, with unbelievably large and graceful hands and feet, was a better cook, with the softest voice and gentlest manner in the world.

But Bertie was our joy and delight. He too may be compared to a star—one which, originally bright, becomes temporarily dim, and finally attains to greater magnitude than before. Ultimately he became a fixed ornament of our culinary and taxidermic cosmic system, and whatever he did was accomplished with the most remarkable contortions of limbs and body. To watch him rake was to learn new anatomical possibilities; when he paddled, a surgeon would be moved to astonishment; when he caught butterflies, a teacher of physical culture would not have believed his eyes.

At night, when our servants had sealed themselves hermetically in their room in the neighboring thatched quarters, and the last squeak from our cots had passed out on its journey to the far distant goal of all nocturnal sounds, we began to realize that our new home held many more occupants than our three selves. Stealthy rustlings, indistinct scrapings, and low murmurs kept us interested for as long as ten minutes;[16] and in the morning we would remember and wonder who our fellow tenants could be. Some nights the bungalow seemed as full of life as the tiny French homes labeled, "Hommes 40: Chevaux 8," when the hastily estimated billeting possibilities were actually achieved, and one wondered whether it were not better to be the cheval premier, than the homme quarantième.

For years the bungalow had stood in sun and rain unoccupied, with a watchman and his wife, named Hope, who lived close by. The aptness of his name was that of the little Barbadian mule-tram which creeps through the coral-white streets, striving forever to divorce motion from progress and bearing the name Alert. Hope had done his duty and watched the bungalow. It was undoubtedly still there and nothing had been taken from it; but he had received no orders as to accretions, and so, to our infinite joy and entertainment, we found that in many ways it was not only near jungle, it was jungle. I have compared it with a natural cave. It was also like a fallen jungle-log, and we some of the small folk who shared its dark recesses with hosts of others. Through the air, on wings of skin or feathers[17] or tissue membrane; crawling or leaping by night; burrowing underground; gnawing up through the great supporting posts; swarming up the bamboos and along the pliant curving stems to drop quietly on the shingled roof;—thus had the jungle-life come past Hope's unseeing eyes and found the bungalow worthy residence.

The bats were with us from first to last. We exterminated one colony which spent its inverted days clustered over the center of our supply chamber, but others came immediately and disputed the ownership of the dark room. Little chaps with great ears and nose-tissue of sensitive skin, spent the night beneath my shelves and chairs, and even my cot. They hunted at dusk and again at dawn, slept in my room and vanished in the day. Even for bats they were ferocious, and whenever I caught one in a butterfly-net, he went into paroxysms of rage, squealing in angry passion, striving to bite my hand and, failing that, chewing vainly on his own long fingers and arms. Their teeth were wonderfully intricate and seemed adapted for some very special diet, although beetles seemed to satisfy those[18] which I caught. For once, the systematist had labeled them opportunely, and we never called them anything but Furipterus horrens.

In the evening, great bats as large as small herons swept down the long front gallery where we worked, gleaning as they went; but the vampires were long in coming, and for months we neither saw nor heard of one. Then they attacked our servants, and we took heart, and night after night exposed our toes, as conventionally accepted vampire-bait. When at last they found that the color of our skins was no criterion of dilution of blood, they came in crowds. For three nights they swept about us with hardly a whisper of wings, and accepted either toe or elbow or finger, or all three, and the cots and floor in the morning looked like an emergency hospital behind an active front. In spite of every attempt at keeping awake, we dropped off to sleep before the bats had begun, and did not waken until they left. We ascertained, however, that there was no truth in the belief that they hovered or kept fanning with their wings. Instead, they settled on the person with an appreciable flop and then crawled to the desired spot.[19]

One night I made a special effort and, with bared arm, prepared for a long vigil. In a few minutes bats began to fan my face, the wings almost brushing, but never quite touching my skin. I could distinguish the difference between the smaller and the larger, the latter having a deeper swish, deeper and longer drawn-out. Their voices were so high and shrill that the singing of the jungle crickets seemed almost contralto in comparison. Finally, I began to feel myself the focus of one or more of these winged weasels. The swishes became more frequent, the returnings almost doubling on their track. Now and then a small body touched the sheet for an instant, and then, with a soft little tap, a vampire alighted on my chest. I was half sitting up, yet I could not see him, for I had found that the least hint of light ended any possibility of a visit. I breathed as quietly as I could, and made sure that both hands were clear. For a long time there was no movement, and the renewed swishes made me suspect that the bat had again taken flight. Not until I felt a tickling on my wrist did I know that my visitor had shifted and, unerringly, was making for the arm which I had exposed. Slowly it crept forward,[20] but I hardly felt the pushing of the feet and pulling of the thumbs as it crawled along. If I had been asleep, I should not have awakened. It continued up my forearm and came to rest at my elbow. Here another long period of rest, and then several short, quick shifts of body. With my whole attention concentrated on my elbow, I began to imagine various sensations as my mind pictured the long, lancet tooth sinking deep into the skin, and the blood pumping up. I even began to feel the hot rush of my vital fluid over my arm, and then found that I had dozed for a moment and that all my sensations were imaginary. But soon a gentle tickling became apparent, and, in spite of putting this out of my mind and with increasing doubts as to the bat being still there, the tickling continued. It changed to a tingling, rather pleasant than otherwise, like the first stage of having one's hand asleep.

It really seemed as if this were the critical time. Somehow or other the vampire was at work with no pain or even inconvenience to me, and now was the moment to seize him, call for a lantern, and solve his supersurgical skill, the exact method of this vespertilial anæsthetist.[21] Slowly, very slowly, I lifted the other hand, always thinking of my elbow, so that I might keep all the muscles relaxed. Very slowly it approached, and with as swift a motion as I could achieve, I grasped at the vampire. I felt a touch of fur and I gripped a struggling, skinny wing; there came a single nip of teeth, and the wing-tip slipped through my fingers. I could detect no trace of blood by feeling, so turned over and went to sleep. In the morning I found a tiny scratch, with the skin barely broken; and, heartily disappointed, I realized that my tickling and tingling had been the preliminary symptoms of the operation.

Marvelous moths which slipped into the bungalow like shadows; pet tarantulas; golden-eyed gongasocka geckos; automatic, house-cleaning ants; opossums large and small; tiny lizards who had tongues in place of eyelids; wasps who had doorsteps and watched the passing from their windows;—all these were intimates of my laboratory table, whose riches must be spread elsewhere; but the sounds of the bungalow were common to the whole structure.

One of the first things I noticed, as I lay on my cot, was the new voice of the wind at night.[22] Now and then I caught a familiar sound,—faint, but not to be forgotten,—the clattering of palm fronds. But this came from Boom-boom Point, fifty yards away (an out jutting of rocks where we had secured our first giant catfish of that name). The steady rhythm of sound which rose and fell with the breeze and sifted into my window with the moonbeams, was the gentlest shussssssing, a fine whispering, a veritable fern of a sound, high and crisp and wholly apart from the moaning around the eaves which arose at stronger gusts. It brought to mind the steep mountain-sides of Pahang, and windy nights which presaged great storms in high passes of Yunnan.

But these wonder times lived only through memory and were misted with intervening years, while it came upon me during early nights, again and again, that this was Now, and that into the hour-glass neck of Now was headed a maelstrom of untold riches of the Future—minutes and hours and sapphire days ahead—-a Now which was wholly unconcerned with leagues and liquor, with strikes and salaries. So I turned over with the peace which passes all telling—the forecast of delving into the private affairs of birds and[23] monkeys, of great butterflies and strange frogs and flowers. The seeping wind had led my mind on and on from memory and distant sorrows to thoughts of the joy of labor and life.

At half-past five a kiskadee shouted at the top of his lungs from the bamboos, but he probably had a nightmare, for he went to sleep and did not wake again for half-an-hour. The final swish of a bat's wing came to my ear, and the light of a fog-dimmed day slowly tempered the darkness among the dusty beams and rafters. From high overhead a sprawling tarantula tossed aside the shriveled remains of his night's banquet, the emerald cuirass and empty mahogany helmet of a long-horned beetle, which eddied downward and landed upon my sheet.

Immediately around the bungalow the bamboos held absolute sway, and while forming a very tangible link between the roof and the outliers of the jungle, yet no plant could obtain foothold beneath their shade. They withheld light, and the mat of myriads of slender leaves killed off every sprouting thing. This was of the utmost value to us, providing shade, clear passage to every breeze, and an absolute dearth of flies and mosquitoes. We found that the[24] clumps needed clearing of old stems, and for two days we indulged in the strangest of weedings. The dead stems were as hard as stone outside, but the ax bit through easily, and they were so light that we could easily carry enormous ones, which made us feel like giants, though, when I thought of them in their true botanical relationship, I dwarfed in imagination as quickly as Alice, to a pigmy tottering under a blade of grass. It was like a Brobdingnagian game of jack-straws, as the cutting or prying loose of a single stem often brought several others crashing to earth in unexpected places, keeping us running and dodging to avoid their terrific impact. The fall of these great masts awakened a roaring swish ending in a hollow rattling, wholly unlike the crash and dull boom of a solid trunk. When we finished with each clump, it stood as a perfect giant bouquet, looking, at a distance, like a tuft of green feathery plumes, with the bungalow snuggled beneath as a toadstool is overshadowed by ferns.

Scores of the homes of small folk were uncovered by our weeding out—wasps, termites, ants, bees, wood-roaches, centipedes; and occasionally a small snake or great solemn toad came out from the débris at the roots, the latter blinking and[25] swelling indignantly at this sudden interruption of his siesta. In a strong wind the stems bent and swayed, thrashing off every imperfect leaf and sweeping low across the roof, with strange scrapings and bamboo mutterings. But they hardly ever broke and fell. In the evening, however, and in the night, after a terrific storm, a sharp, unexpected rat-tat-tat-tat, exactly like a machine-gun, would smash in on the silence, and two or three of the great grasses, which perhaps sheltered Dutchmen generations ago, would snap and fall. But the Indians and Bovianders who lived nearby, knew this was no wind, nor yet weakness of stem, but Sinclair, who was abroad and who was cutting down the bamboos for his own secret reasons. He was evil, and it was well to be indoors with all windows closed; but further details were lacking, and we were driven to clothe this imperfect ghost with history and habits of our own devising.

The birds and other inhabitants of the bamboos, were those of the more open jungle,—flocks drifting through the clumps, monkeys occasionally swinging from one to another of the elastic tips, while toucans came and went. At evening, flocks of parrakeets and great black orioles came[26] to roost, courting the safety which they had come to associate with the clearings of human pioneers in the jungle. A box on a bamboo stalk drew forth joyous hymns of praise from a pair of little God-birds, as the natives call the house-wrens, who straightway collected all the grass and feathers in the world, stuffed them into the tiny chamber, and after a time performed the ever-marvelous feat of producing three replicas of themselves from this trash-filled box. The father-parent was one concentrated mite of song, with just enough feathers for wings to enable him to pursue caterpillars and grasshoppers as raw material for the production of more song. He sang at the prospect of a home; then he sang to attract and win a mate; more song at the joy of finding wonderful grass and feathers; again melody to beguile his mate, patiently giving the hours and days of her body-warmth in instinct-compelled belief in the future. He sang while he took his turn at sitting; then he nearly choked to death trying to sing while stuffing a bug down a nestling's throat; finally, he sang at the end of a perfect nesting season; again, in hopes of persuading his mate to repeat it all, and this failing, sang in chorus in the wren quintette—I hoped, in[27] gratitude to us. At least from April to September he sang every day, and if my interpretation be anthropomorphic, why, so much the better for anthropomorphism. At any rate, before we left, all five wrens sat on a little shrub and imitated the morning stars, and our hearts went out to the little virile featherlings, who had lost none of their enthusiasm for life in this tropical jungle. Their one demand in this great wilderness was man's presence, being never found in the jungle except in an inhabited clearing, or, as I have found them, clinging hopefully to the vanishing ruins of a dead Indian's benab, waiting and singing in perfect faith, until the jungle had crept over it all and they were compelled to give up and set out in search of another home, within sound of human voices.

Bare as our leaf-carpeted bamboo-glade appeared, yet a select little company found life worth living there. The dry sand beneath the house was covered with the pits of ant-lions, and as we watched them month after month, they seemed to have more in common with the grains of quartz which composed their cosmos than with the organic world. By day or night no ant or other edible thing seemed ever to approach or be[28] entrapped; and month after month there was no sign of change to imago. Yet each pit held a fat, enthusiastic inmate, ready at a touch to turn steam-shovel, battering-ram, bayonet, and gourmand. Among the first thousand-and-one mysteries of Kartabo I give a place to the source of nourishment of the sub-bungalow ant-lions.

Walking one day back of the house, I observed a number of small holes, with a little shining head just visible in each, which vanished at my approach. Looking closer, I was surprised to find a colony of tropical doodle-bugs. Straightway I chose a grass-stem and squatting, began fishing as I had fished many years ago in the southern states. Soon a nibble and then an angry pull, and I jerked out the irate little chap. He had the same naked bumpy body and the fierce head, and when two or three were put together, they fought blindly and with the ferocity of bulldogs.

To write of pets is as bad taste as to write in diary form, and, besides, I had made up my mind to have no pets on this expedition. They were a great deal of trouble and a source of distraction from work while they were alive; and one's heart was wrung and one's concentration disturbed at[29] their death. But Kib came one day, brought by a tiny copper-bronze Indian. He looked at me, touched me tentatively with a mobile little paw, and my firm resolution melted away. A young coati-mundi cannot sit man-fashion like a bear-cub, nor is he as fuzzy as a kitten or as helpless as a puppy, but he has ways of winning to the human heart, past all obstacles.

The small Indian thought that three shillings would be a fair exchange; but I knew the par value of such stock, and Kib changed hands for three bits. A week later a thousand shillings would have seemed cheap to his new master. A coati-mundi is a tropical, arboreal raccoon of sorts, with a long, ever-wriggling snout, sharp teeth, eyes that twinkle with humor, and clawed paws which are more skilful than many a fingered hand. By the scientists of the world he is addressed as Nasua nasua nasua—which lays itself open to the twin ambiguity of stuttering Latin, or the echoes of a Princetonian football yell. The natural histories call him coati-mundi, while the Indian has by far the best of it, with the ringing, climactic syllables, Kibihée! And so, in the case of a being who has received much more than his share of vitality, it was altogether fitting to[30] shorten this to Kib—Dunsany's giver of life upon the earth.

My heart's desire is to run on and tell many paragraphs of Kib; but that, as I have said, would be bad taste, which is one form of immorality. For in such things sentiment runs too closely parallel to sentimentality,—moderation becomes maudlinism,—and one enters the caste of those who tell anecdotes of children, and the latest symptoms of their physical ills. And the deeper one feels the joys of friendship with individual small folk of the jungle, the more difficult it is to convey them to others. And so it is not of the tropical mammal coati-mundi, nor even of the humorous Kib that I think, but of the soul of him galloping up and down his slanting log, of his little inner ego, which changed from a wild thing to one who would hurl himself from any height or distance into a lap, confident that we would save his neck, welcome him, and waste good time playing the game which he invented, of seeing whether we could touch his little cold snout before he hid it beneath his curved arms.

So, in spite of my resolves, our bamboo groves became the homes of numerous little souls of wild folk, whose individuality shone out and dominated[31] the less important incidental casement, whether it happened to be feathers, or fur, or scales. It is interesting to observe how the Adam in one comes to the surface in the matter of names for pets. I know exactly the uncomfortable feeling which must have perturbed the heart of that pioneer of nomenclaturists, to be plumped down in the midst of "the greatest aggregation of animals ever assembled" before the time of Noah, and to be able to speak of them only as this or that, he or she. So we felt when inundated by a host of pets. It is easy to speak of the species by the lawful Latin or Greek name; we mention the specimen on our laboratory table by its common natural-history appellation. But the individual who touches our pity, or concern, or affection, demands a special title—usually absurdly inapt.

Soon, in the bamboo glade about our bungalow, ten little jungle friends came to live; and to us they will always be Kib and Gawain, George and Gregory, Robert and Grandmother, Raoul and Pansy, Jennie and Jellicoe.

Gawain was not a double personality—he was an intermittent reincarnation, vibrating between the inorganic and the essence of vitality. In a[32] reasonable scheme of earthly things he filled the niche of a giant green tree-frog, and one of us seemed to remember that the Knight Gawain was enamored of green, and so we dubbed him. For the hours of daylight Gawain preferred the role of a hunched-up pebble of malachite; or if he could find a leaf, he drew eighteen purple vacuum toes beneath him, veiled his eyes with opalescent lids, and slipped from the mineral to the vegetable kingdom, flattened by masterly shading which filled the hollows and leveled the bumps; and the leaf became more of a leaf than it had been before Gawain was merged with it.

Night, or hunger, or the merciless tearing of sleep from his soul wrought magic and transformed him into a glowing, jeweled specter. He sprouted toes and long legs; he rose and inflated his sleek emerald frog-form; his sides blazed forth a mother-of-pearl waist-coat—a myriad mosaics of pink and blue and salmon and mauve; and from nowhere if not from the very depths of his throat, there slowly rose twin globes,—great eyes,—which stood above the flatness of his head, as mosques above an oriental city. Gone were the neutralizing lids, and in their place, strange upright pupils surrounded with vermilion lines and[33] curves and dots, like characters of ancient illuminated Persian script. And with these appalling eyes Gawain looked at us, with these unreal, crimson-flecked globes staring absurdly from an expressionless emerald mask, he contemplated roaches and small grasshoppers, and correctly estimated their distance and activity. We never thought of demanding friendship, or a hint of his voice, or common froggish activities from Gawain. We were content to visit him now and then, to arouse him, and then leave him to disincarnate his vertebral outward phase into chlorophyll or lifeless stone. To muse upon his courtship or emotions was impossible. His life had a feeling of sphinx-like duration—Gawain as a tadpole was unthinkable. He seemed ageless, unreal, wonderfully beautiful, and wholly inexplicable.

Within six degrees of the Equator, shut in by jungle, on a cloudless day in mid-August, I found a comfortable seat on a slope of sandy soil sown with grass and weeds in the clearing back of Kartabo laboratory. I was shaded only by a few leaves of a low walnut-like sapling, yet there was not the slightest hint of oppressive heat. It might have been a warm August day in New England or Canada, except for the softness of the air.

In my little cleared glade there was no plant which would be wholly out of place on a New England country hillside. With debotanized vision I saw foliage of sumach, elm, hickory, peach, and alder, and the weeds all about were as familiar as those of any New Jersey meadow. The most abundant flowers were Mazaruni daisies, cheerful little pale primroses, and close to me, fairly overhanging the paper as I wrote, was the spindling button-weed, a wanderer from[35] the States, with its clusters of tiny white blossoms bouqueted in the bracts of its leaves.

A few yards down the hillside was a clump of real friends—the rich green leaves of vervain, that humble little weed, sacred in turn to the Druids, the Romans, and the early Christians, and now brought inadvertently in some long-past time, in an overseas shipment, and holding its own in this breathing-space of the jungle. I was so interested by this discovery of a superficial northern flora, that I began to watch for other forms of temperate-appearing life, and for a long time my ear found nothing out of harmony with the plants. The low steady hum of abundant insects was so constant that it required conscious effort to disentangle it from silence. Every few seconds there arose the cadence of a passing bee or fly, the one low and deep, the other shrill and penetrating. And now, just as I had become wholly absorbed in this fascinating game,—the kind of game which may at any moment take a worth-while scientific turn,—it all dimmed and the entire picture shifted and changed. I doubt if any one who has been at a modern battle-front can long sit with closed eyes in a midsummer meadow and not have his blood leap as scene after[36] scene is brought back to him. Three bees and a fly winging their way past, with the rise and fall of their varied hums, were sufficient to renew vividly for me the blackness of night over the sticky mud of Souville, and to cloud for a moment the scent of clover and dying grass, with that terrible sickly sweet odor of human flesh in an old shell-hole. In such unexpected ways do we link peace and war—suspending the greatest weights of memory, imagination, and visualization on the slenderest cobwebs of sound, odor, and color.

But again my bees became but bees—great, jolly, busy yellow-and-black fellows, who blundered about and squeezed into blossoms many sizes too small for them. Cicadas tuned up, clearing their drum-heads, tightening their keys, and at last rousing into the full swing of their ecstatic theme. And my relaxed, uncritical mind at present recorded no difference between the sound and that which was vibrated from northern maples. The tamest bird about me was a big yellow-breasted white-throated flycatcher, and I had seen this Melancholy Tyrant, as his technical name describes him, in such distant lands that he fitted into the picture without effort.[37]

White butterflies flitted past, then a yellow one, and finally a real Monarch. In my boy-land, smudgy specimens of this were pinned, earnestly but asymetrically, in cigar-boxes, under the title of Danais archippus. At present no reputable entomologist would think of calling it other than Anosia plexippus, nor should I; but the particular thrill which it gave to-day was that this self-same species should wander along at this moment to mosaic into my boreal muse.

After a little time, with only the hum of the bees and the staccato cicadas, a double deceit was perpetrated, one which my sentiment of the moment seized upon and rejoiced in, but at which my mind had to conceal a smile and turn its consciousness quickly elsewhere, to prevent an obtrusive reality from dimming this last addition to the picture. The gentle, unmistakable, velvet warble of a bluebird came over the hillside, again and again; and so completely absorbed and lulled was I by the gradual obsession of being in the midst of a northern scene, that the sound caused not the slightest excitement, even internally and mentally. But the sympathetic spirit who was directing this geographic burlesque overplayed, and followed the soft curve of audible wistfulness[38] with an actual bluebird which looped across the open space in front. The spell was broken for a moment, and my subconscious autocrat thrust into realization the instantaneous report—apparent bluebird call is the note of a small flycatcher and the momentary vision was not even a mountain bluebird but a red-breasted blue chatterer! So I shut my eyes very quickly and listened to the soft calls, which alone would have deceived the closest analyzer of bird songs. And so for a little while longer I still held my picture intact, a magic scape, a hundred yards square and an hour long, set in the heart of the Guiana jungle.

And when at last I had to desert Canada, and relinquish New Jersey, I slipped only a few hundred miles southward. For another twenty minutes I clung to Virginia, for the enforced shift was due to a great Papilio butterfly which stopped nearby and which I captured with a lucky sweep of my net. My first thought was of the Orange-tree Swallow-tail, née Papilio cresphontes. Then the first lizards appeared, and by no stretch of my willing imagination could I pretend that they were newts, or fit the little emerald scales into a New England pasture. And so I chose for a time to live again among the Virginian[39] butterflies and mockingbirds, the wild roses and the jasmine, and the other splendors of memory which a single butterfly had unloosed.

As I looked about me, I saw the flowers and detected their fragrance; I heard the hum of bees and the contented chirp of well-fed birds; I marveled at great butterflies flapping so slowly that it seemed as if they must have cheated gravitation in some subtle way to win such lightness and disregard of earth-pull. I heard no ugly murmur of long hours and low wages; the closest scrutiny revealed no strikes or internal clamorings about wrongs; and I unconsciously relaxed and breathed more deeply at the thought of this nature world, moving so smoothly, with directness and simplicity as apparently achieved ideals.

Then I ceased this superficial glance and looked deeper, and without moralizing or dragging in far-fetched similes or warnings, tried to comprehend one fundamental reality in wild nature—the universal acceptance of opportunity. From this angle it is quite unimportant whether one believes in vitalism (which is vitiating to our "will to prove"), or in mechanism (whose name itself is a symbol of ignorance, or deficient vocabulary,[40] or both). Evolution has left no chink or crevice unfilled, unoccupied, no probability untried, no possibility unachieved.

The nearest weed suggested this trend of thought and provided all I could desire of examples; but the thrill of discovery and the artistic delight threatened to disturb for the time my solemn application of these ponderous truisms. The weed alongside had had a prosperous life, and its leaves were fortunate in the unadulterated sun and rain to which they had access. At the summit all was focusing for the consummation of existence: the little blossoms would soon open and have their one chance. To all the winds of heaven they would fling out wave upon wave of delicate odor, besides enlisting a subtle form of vibration and refusing to absorb the pink light—thereby enhancing the prospects of insect visitors, on whose coming the very existence of this race of weeds depended.

Every leaf showed signs of attack: scallops cut out, holes bored, stains of fungi, wreaths of moss, and the insidious mazes of leaf-miners. But, like an old-fashioned ship of the line which wins to port with the remnants of shot-ridden sails, the plant had paid toll bravely, although unable[41] to defend itself or protect its tissues; and if I did not now destroy it, which I should assuredly not do, this weed would justify its place as a worthy link in the chain of numberless generations, past and to come.

More complex, clever, subtle methods of attack transcended those of the mere devourer of leaf-tissue, as radically as an inventor of most intricate instruments differs from the plodding tiller of the soil. In the center of one leaf, less disfigured than some of its fellows, I perceived four tiny ivory spheres, a dozen of which might rest comfortably within the length of an inch. To my eye they looked quite smooth, although a steady oblique gaze revealed hints of concentric lines. Before the times of Leeuwenhoek I should perhaps have been unable to see more than this, although, as a matter of fact, in those happy-go-lucky days my ancestors would doubtless have trounced me soundly for wasting my time on such useless and ungodly things as butterfly eggs. I thought of the coming night when I should sit and strain with all my might, striving, without the use of my powerful stereos, to separate from translucent mist of gases the denser nucleus of the mighty cosmos in Andromeda. And I alternately[42] bemoaned my human limitation of vision, and rejoiced that I could focus clearly, both upon my butterfly eggs a foot away, and upon the spiral nebula swinging through the ether perhaps four hundred and fifty light-years from the earth.

I unswung my pocket-lens,—the infant of the microscope,—and my whole being followed my eyes; the trees and sky were eclipsed, and I hovered in mid-air over four glistening Mars-like planets—seamed with radiating canals, half in shadow from the slanting sunlight, and silhouetted against pure emerald. The sculpturing was exquisite. Near the north poles which pointed obliquely in my direction, the lines broke up into beads, and the edges of these were frilled and scalloped; and here again my vision failed and demanded still stronger binoculars. Here was indeed complexity: a butterfly, one of those black beauties, splashed with jasper and beryl, hovering nearby, with taste only for liquid nectar, yet choosing a little weed devoid of flower or fruit on which to deposit her quota of eggs. She neither turned to look at their beauties nor trusted another batch to this plant. Somehow, someway, her caterpillar wormhood had carried, through the mummified chrysalid and the reincarnation[43] of her present form, knowledge of an earlier, infinitely coarser diet.

Together with the pure artistic joy which was stirred at the sight of these tiny ornate globes, there was aroused a realization of complexity, of helpless, ignorant achievement; the butterfly blindly pausing in her flower-to-flower fluttering—a pause as momentous to her race as that of the slow daily and monthly progress of the weed's struggle to fruition.

I took a final glance at the eggs before returning to my own larger world, and I detected a new complication, one which left me with feelings too involved for calm scientific contemplation. As if a Martian should suddenly become visible to an astronomer, I found that one of the egg planets was inhabited. Perched upon the summit—quite near the north pole—was an insect, a wasp, much smaller than the egg itself. And as I looked, I saw it at the climax of its diminutive life; for it reared up, resting on the tips of two legs and the iridescent wings, and sunk its ovipositor deep into the crystalline surface. As I watched, an egg was deposited, about the latitude of New York, and with a tremor the tiny wasp withdrew its instrument and rested.[44]

On the same leaf were casually blown specks of dust, larger than the quartette of eggs. To the plant the cluster weighed nothing, meant nothing more than the dust. Yet a moment before they contained the latent power of great harm to the future growth of the weed—four lusty caterpillars would work from leaf to leaf with a rapidity and destructiveness which might, even at the last, have sapped the maturing seeds. Now, on a smaller scale, but still within the realm of insect life, all was changed—the plant was safe once more and no caterpillars would emerge. For the wasp went from sphere to sphere and inoculated every one with the promise of its kind. The plant bent slightly in a breath of wind, and knew nothing; the butterfly was far away to my left, deep-drinking in a cluster of yellow cassia; the wasp had already forgotten its achievement, and I alone—an outsider, an interloper—observed, correlated, realized, appreciated, and—at the last—remained as completely ignorant as the actors themselves of the real driving force, of the certain beginning, of the inevitable end. Only a momentary cross-section was vouchsafed, and a wonder and a desire to know fanned a little hotter.[45]

I had far from finished with my weed: for besides the cuts and tears and disfigurements of the leaves, I saw a score or more of curious berry-like or acorn-like growths, springing from both leaf and stem. I knew, of course, that they were insect-galls, but never before had they meant quite so much, or fitted in so well as a significant phenomenon in the nexus of entangling relationships between the weed and its environment. This visitor, also a minute wasp of sorts, neither bit nor cut the leaves, but quietly slipped a tiny egg here and there into the leaf-tissue.

And this was only the beginning of complexity. For with the quickening of the larva came a reaction on the part of the plant, which, in defense, set up a greatly accelerated growth about the young insect. This might have taken the form of some distorted or deformed plant organ—a cluster of leaves, a fruit or berry or tuft of hairs, wholly unlike the characters of the plant itself. My weed was studded with what might well have been normal seed-fruits, were they not proved nightmares of berries, awful pseudo-fruits sprouting from horridly impossible places. And this excess of energy, expressed in tumorous outgrowths, was all vitally useful to the grub—just[46] as the skilful jiu-jitsu wrestler accomplishes his purpose with the aid of his opponent's strength. The insect and plant were, however, far more intricately related than any two human competitors: for the grub in turn required the continued health and strength of the plant for its existence; and when I plucked a leaf, I knew I had doomed all the hidden insects living within its substance.

The galls at my hand simulated little acorns, dull greenish in color, matching the leaf-surface on which they rested, and rising in a sharp point. I cut one through and, when wearied and fretted with the responsibilities of independent existence, I know I shall often recall and envy my grub in his palatial parasitic home. Outside came a rather hard, brown protective sheath; then the main body of the gall, of firm and dense tissue; and finally, at the heart, like the Queen's chamber in Cheops, the irregular little dwelling-place of the grub. This was not empty and barren; but the blackness and silence of this vegetable chamber, this architecture fashioned by the strangest of builders for the most remarkable of tenants, was filled with a nap of long, crystalline hairs or threads like the spun-glass candy in our[47] Christmas sweetshops—white at the base and shading from pale salmon to the deepest of pinks. This exquisite tapestry, whose beauties were normally forever hidden as well from the blind grub as from the outside world, was the ambrosia all unwittingly provided by the antagonism of the plant; the nutrition of resentment, the food of defiance; and day by day the grub gradually ate his way from one end to the other of his suite, laying a normal, healthful physical foundation for his future aerial activities.

The natural history of galls is full of romance and strange unrealities, but to-day it meant to me only a renewed instance of an opportunity seized and made the most of; the success of the indirect, the unreasonable—the long chance which so few of us humans are willing to take, although the reward is a perpetual enthusiasm for the happening of the moment, and the honest gambler's joy for the future. How much more desirable to acquire merit as a footless grub in the heart of a home, erected and precariously nourished by a worthy opponent, with a future of unnumbered possibilities, than to be a queen-mother in nest or hive—cared-for, fed, and cleansed by a host of slaves, but with less prospect[48] of change or of adventure than an average toadstool.

Thus I sat for a long time, lulled by similitudes of northern plants and bees and birds, and then gently shifted southward a few hundred miles, the transition being smooth and unabrupt. With equal gentleness the dead calm stirred slightly and exhaled the merest ghost of a breeze; it seemed as if the air was hardly in motion, but only restless: the wings of the bees and the flycatcher might well have caused it. But, judged by the sequence of events, it was the almost imperceptible signal given by some great Jungle Spirit, who had tired of playing with my dreams and pleasant fancies of northern life, and now called upon her legions to disillusion me. And the response was immediate. Three great shells burst at my very feet,—one of sound, one of color, and the third of both plus numbers,—and from that time on, tropical life was dominant whichever way I looked. That is the way with the wilderness, and especially the tropical wilderness—to surprise one in the very field with which one is most familiar. While in my own estimation my chief profession is ignorance, yet I sign[49] my passport applications and my jury evasions as Ornithologist. And now this playful Spirit of the Jungle permitted me to meditate cheerfully on my ability to compare the faunas of New York and Guiana, and then proceeded to startle me with three salvos of birds, first physically and then emotionally.

From the monotone of under-world sounds a strange little rasping detached itself, a reiterated, subdued scraping or picking. It carried my mind instantly to the throbbing theme of the Niebelungs, onomatopoetic of the little hammers forever busy in their underground work. I circled a small bush at my side, and found that the sound came from one of the branches near the top; so with my glasses I began a systematic search. It was at this propitious moment, when I was relaxed in every muscle, steeped in the quiet of this hillside, and keen on discovering the beetle, that the first shell arrived. If I had been less absorbed I might have heard some distant chattering or calling, but this time it was as if a Spad had shut off its power, volplaned, kept ahead of its own sound waves, and bombed me. All that actually happened was that a band of little parrakeets flew down and alighted nearby.[50] When I discovered this, it seemed a disconcerting anti-climax, just as one can make the bravest man who has been under rifle-fire flinch by spinning a match swiftly past his ear.

I have heard this sound of parrakeet's wings, when the birds were alighting nearby, half a dozen times; but after half a hundred I shall duck just as spontaneously, and for a few seconds stand just as immobile with astonishment. From a volcano I expect deep and sinister sounds; when I watch great breakers I would marvel only if the accompanying roar were absent; but on a calm sunny August day I do not expect a noise which, for suddenness and startling character, can be compared only with a tremendous flash of lightning. Imagine a wonderful tapestry of strong ancient stuff, which had only been woven, never torn, and think of this suddenly ripped from top to bottom by some sinister, irresistible force.

In the instant that the sound began, it ceased; there was no echo, no bell-like sustained overtones; both ends were buried in silence. As it came to-day it was a high tearing crash which shattered silence as a Very light destroys darkness; and at its cessation I looked up and saw[51] twenty little green figures gazing intently down at me, from so small a sapling that their addition almost doubled the foliage. That their small wings could wring such a sound from the fabric of the air was unbelievable. At my first movement, the flock leaped forth, and if their wings made even a rustle, it was wholly drowned in the chorus of chattering cries which poured forth unceasingly as the little band swept up and around the sky circle. As an alighting morpho butterfly dazzles the eyes with a final flash of his blazing azure before vanishing behind the leaves and fungi of his lower surface, so parrakeets change from screaming motes in the heavens to silence, and then to a hurtling, roaring boomerang, whose amazing unexpectedness would distract the most dangerous eyes from the little motionless leaf-figures in a neighboring treetop.

When I sat down again, the whole feeling of the hillside was changed. I was aware that my weed was a northern weed only in appearance, and I should not have been surprised to see my bees change to flies or my lizards to snakes—tropical beings have a way of doing such things.

The next phenomenon was color,—unreal, living pigment,—which seemed to appeal to more[52] than one sense, and which satisfied, as a cooling drink or a rare, delicious fragrance satisfies. A medium-sized, stocky bird flew with steady wing-beats over the jungle, in black silhouette against the sky, and swung up to an outstanding giant tree which partly overhung the edge of my clearing. The instant it passed the zone of green, it flashed out brilliant turquoise, and in the same instant I recognized it and reached for my gun. Before I retrieved the bird, a second, dull and dark-feathered, flew from the tree. I had watched it for some time, but now, as it passed over, I saw no yellow and knew it too was of real scientific interest to me; and with the second barrel I secured it. Picking up my first bird, I found that it was not turquoise, but beryl; and a few minutes later I was certain that it was aquamarine; on my way home another glance showed the color of forget-me-nots on its plumage, and as I looked at it on my table, it was Nile green. Yet the feathers were painted in flat color, without especial sheen or iridescence, and when I finally analyzed it, I found it to be a delicate calamine blue. It actually had the appearance of a too strong color, as when a glistening surface reflects the sun. From beak to tail it threw off[53] this glowing hue, except for its chin and throat, which were a limpid amaranth purple; and the effect on the excited rods and cones in one's eyes was like the power of great music or some majestic passage in the Bible. You, who think my similes are overdone, search out in the nearest museum the dustiest of purple-throated cotingas,—Cotinga cayana,—and then, instead, berate me for inadequacy.

Sheer color alone is powerful enough, but when heightened by contrast, it becomes still more effective, and I seemed to have secured, with two barrels, a cotinga and its shadow. The latter was also a full-grown male cotinga, known to a few people in this world as the dark-breasted mourner (Lipaugus simplex). In general shape and form it was not unlike its cousin, but in color it was its shadow, its silhouette. Not a feather upon head or body, wings or tail showed a hint of warmth, only a dull uniform gray; an ash of a bird, living in the same warm sunlight, wet by the same rain, feeding on much the same food, and claiming relationship with a blazing-feathered turquoise. There is some very exact and very absorbing reason for all this, and for it I search with fervor, but with little success. But[54] we may be certain that the causes of this and of the host of other unreasonable realities which fill the path of the evolutionist with never-quenched enthusiasm, will extend far beyond the colors of two tropical birds. They will have something to do with flowers and with bright butterflies, and we shall know why our "favorite color" is more than a whim, and why the Greeks may not have been able to distinguish the full gamut of our spectrum, and why rainbows are so narrow to our eyes in comparison to what they might be.

Finally, there was thrown aside all finesse, all delicacy of presentation, and the last lingering feeling of temperate life and nature was erased. From now on there was no confusion of zones, no concessions, no mental palimpsest of resolving images. The spatial, the temporal,—the hillside, the passing seconds,—the vibrations and material atoms stimulating my five senses, all were tropical, quickened with the unbelievable vitality of equatorial life. A rustling came to my ears, although the breeze was still little more than a sensation of coolness. Then a deep whirr sounded overhead, and another, and another, and with a rush a dozen great toucans were all about[55] me. Monstrous beaks, parodies in pastels of unheard-of blues and greens, breasts which glowed like mirrored suns,—orange overlaid upon blinding yellow,—and at every flick of the tail a trenchant flash of intense scarlet. All these colors set in frames of jet-black plumage, and suddenly hurled through blue sky and green foliage, made the hillside a brilliant moving kaleidoscope.

Some flew straight over, with several quick flaps, then a smooth glide, flaps and glide. A few banked sharply at sight of me, and wheeled to right or left. Others alighted and craned their necks in suspicion; but all sooner or later disappeared eastward in the direction of a mighty jungle tree just bursting into a myriad of berries. They were sulphur-breasted toucans, and they were silent, heralded only by the sound of their wings and the crash of their pigments. I can think of no other assemblage of jungle creatures more fitted to impress one with the prodigality of tropical nature. Four years before, we set ourselves to work to discover the first eggs and young of toucans, and after weeks of heartbreaking labor and disappointments we succeeded. Out of the five species of toucans living in this part of Guiana we found the nests of four,[56] and the one which eluded us was the big sulphur-breasted fellow. I remembered so vividly the painstaking care with which, week after week, we and our Indians tramped the jungle for miles,—through swamps and over rolling hills,—at last having to admit failure; and now I sat and watched thirty, forty, fifty of the splendid birds whirr past. As the last of the fifty-four flew on to their feast of berries, I recalled with difficulty my faded visions of northern birds.

And so ended, as in the great finale of a pyrotechnic display, my two hours on a hillside clearing. I can neither enliven it with a startling escape, nor add a thrill of danger, without using as many "ifs" as would be needed to make a Jersey meadow untenable. For example, if I had fallen over backwards and been powerless to rise or move, I should have been killed within half an hour, for a stray column of army ants was passing within a yard of me, and death would await any helpless being falling across their path. But by searching out a copperhead and imitating Cleopatra, or with patience and persistence devouring every toadstool, the same result could be achieved in our home-town orchard. When on the march, the army ants are as innocuous at two[57] inches as at two miles. Had I sat where I was for days and for nights, my chief danger would have been demise from sheer chagrin at my inability to grasp the deeper significance of life and its earthly activities.

From uniform to civilian clothes is a change transcending mere alteration of stuffs and buttons. It is scarcely less sweeping than the shift from civilian clothes to bathing-suit, which so often compels us to concentrate on remembered mental attributes, to avoid demanding a renewed introduction to estranged personality. In the home life of the average soldier, the relaxation from sustained tension and conscious routine results in a gentleness and quietness of mood for which warrior nations are especially remembered.

Army ants have no insignia to lay aside, and their swords are too firmly hafted in their own beings to be hung up as post-bellum mural decorations, or—as is done only in poster-land—metamorphosed into pruning-hooks and plowshares.

I sat at my laboratory table at Kartabo, and looked down river to the pink roof of Kalacoon, and my mind went back to the shambles of Pit[59] Number Five.[1] I was wondering whether I should ever see the army ants in any guise other than that of scouting, battling searchers for living prey, when a voice of the jungle seemed to hear my unexpressed wish. The sharp, high notes of white-fronted antbirds—those white-crested watchers of the ants—came to my ears, and I left my table and followed up the sound. Physically, I merely walked around the bungalow and approached the edge of the jungle at a point where we had erected a small outhouse a day or two before. But this two hundred feet might just as well have been a single step through quicksilver, hand in hand with Alice, for it took me from a world of hyoids and syrinxes, of vials and lenses and clean-smelling xylol, to the home of the army ants.

[1] See Jungle Peace, p. 211.

The antbirds were chirping and hopping about on the very edge of the jungle, but I did not have to go that far. As I passed the doorless entrance of the outhouse I looked up, and there was an immense mass of some strange material suspended in the upper corner. It looked like stringy, chocolate-colored tow, studded with hundreds of tiny ivory buttons. I came closer and looked [60]carefully at this mushroom growth which had appeared in a single night, and it was then that my eyes began to perceive and my mind to record, things that my reason besought me to reject. Such phenomena were all right in a dream, or one might imagine them and tell them to children on one's knee, with wind in the eaves—wild tales to be laughed at and forgotten. But this was daylight and I was a scientist; my eyes were in excellent order, and my mind rested after a dreamless sleep; so I had to record what I saw in that little outhouse.

This chocolate-colored mass with its myriad ivory dots was the home, the nest, the hearth, the nursery, the bridal suite, the kitchen, the bed and board of the army ants. It was the focus of all the lines and files which ravaged the jungle for food, of the battalions which attacked every living creature in their path, of the unnumbered rank and file which made them known to every Indian, to every inhabitant of these vast jungles.

Louis Quatorze once said, "L'Etat, c'est moi!" but this figure of speech becomes an empty, meaningless phrase beside what an army ant could boast,—"La maison, c'est moi!" Every rafter, beam, stringer, window-frame and door-[61]frame, hall-way, room, ceiling, wall and floor, foundation, superstructure and roof, all were ants—living ants, distorted by stress, crowded into the dense walls, spread out to widest stretch across tie-spaces. I had thought it marvelous when I saw them arrange themselves as bridges, walks, handrails, buttresses, and sign-boards along the columns; but this new absorption of environment, this usurpation of wood and stone, this insinuation of themselves into the province of the inorganic world, was almost too astounding to credit.

All along the upper rim the sustaining structure was more distinctly visible than elsewhere. Here was a maze of taut brown threads stretching in places across a span of six inches, with here and there a tiny knot. These were actually tie-strings of living ants, their legs stretched almost to the breaking-point, their bodies the inconspicuous knots or nodes. Even at rest and at home, the army ants are always prepared, for every quiescent individual in the swarm was standing as erect as possible, with jaws widespread and ready, whether the great curved mahogany scimitars of the soldiers, or the little black daggers of the smaller workers. And with[62] no eyelids to close, and eyes which were themselves a mockery, the nerve shriveling and never reaching the brain, what could sleep mean to them? Wrapped ever in an impenetrable cloak of darkness and silence, life was yet one great activity, directed, ordered, commanded by scent and odor alone. Hour after hour, as I sat close to the nest, I was aware of this odor, sometimes subtle, again wafted in strong successive waves. It was musty, like something sweet which had begun to mold; not unpleasant, but very difficult to describe; and in vain I strove to realize the importance of this faint essence—taking the place of sound, of language, of color, of motion, of form.

I recovered quickly from my first rapt realization, for a dozen ants had lost no time in ascending my shoes, and, as if at a preconcerted signal, all simultaneously sank their jaws into my person. Thus strongly recalled to the realities of life, I realized the opportunity that was offered and planned for my observation. No living thing could long remain motionless within the sphere of influence of these six-legged Boches, and yet I intended to spend days in close proximity. There was no place to hang a hammock,[63] no overhanging tree from which I might suspend myself spider-wise. So I sent Sam for an ordinary chair, four tin cans, and a bottle of disinfectant. I filled the tins with the tarry fluid, and in four carefully timed rushes I placed the tins in a chair-leg square. The fifth time I put the chair in place beneath the nest, but I had misjudged my distances and had to retreat with only two tins in place. Another effort, with Spartan-like disregard of the fiery bites, and my haven was ready. I hung a bag of vials, notebook, and lens on the chairback, and, with a final rush, climbed on the seat and curled up as comfortably as possible.

All around the tins, swarming to the very edge of the liquid, were the angry hosts. Close to my face were the lines ascending and descending, while just above me were hundreds of thousands, a bushel-basket of army ants, with only the strength of their threadlike legs as suspension cables. It took some time to get used to my environment, and from first to last I was never wholly relaxed, or quite unconscious of what would happen if a chair-leg broke, or a bamboo fell across the outhouse.

I swiveled round on the chair-seat and counted[64] eight lines of army ants on the ground, converging to the post at my elbow. Each was four or five ranks wide, and the eight lines occasionally divided or coalesced, like a nexus of capillaries. There was a wide expanse of sand and clay, and no apparent reason why the various lines of foragers should not approach the nest in a single large column. The dividing and redividing showed well how completely free were the columns from any individual dominance. There was no control by specific individuals or soldiers, but, the general route once established, the governing factor was the odor of contact.

The law to pass where others have passed is immutable, but freedom of action or individual desire dies with the malleable, plastic ends of the foraging columns. Again and again came to mind the comparison of the entire colony or army with a single organism; and now the home, the nesting swarm, the focus of central control, seemed like the body of this strange amorphous organism—housing the spirit of the army. One thinks of a column of foragers as a tendril with only the tip sensitive and growing and moving, while the corpuscle-like individual ants are driven in the current of blind instinct to and fro,[65] on their chemical errands. And then this whole theory, this most vivid simile, is quite upset by the sights that I watch in the suburbs of this ant home!

The columns were most excellent barometers, and their reaction to passing showers was invariable. The clay surface held water, and after each downfall the pools would be higher, and the contour of the little region altered. At the first few drops, all the ants would hasten, the throbbing corpuscles speeding up. Then, as the rain came down heavier, the column melted away, those near each end hurrying to shelter and those in the center crawling beneath fallen leaves and bits of clod and sticks. A moment before, hundreds of ants were trudging around a tiny pool, the water lined with ant handrails, and in shallow places, veritable formicine pontoons,—large ants which stood up to their bodies in water, with the booty-laden host passing over them. Now, all had vanished, leaving only a bare expanse of splashing drops and wet clay. The sun broke through and the residue rain tinkled from the bamboos.

As gradually as the growth of the rainbow above the jungle, the lines reformed themselves.[66] Scouts crept from the jungle-edge at one side, and from the post at my end, and felt their way, fan-wise, over the rain-scoured surface; for the odor, which was both sight and sound to these ants, had been washed away—a more serious handicap than mere change in contour. Swiftly the wandering individuals found their bearings again. There was deep water where dry land had been, but, as if by long-planned study of the work of sappers and engineers, new pontoon bridges were thrown across, washouts filled in, new cliffs explored, and easy grades established; and by the time the bamboos ceased their own private after-shower, the columns were again running smoothly, battalions of eager light infantry hastening out to battle, and equal hosts of loot-laden warriors hurrying toward the home nest. Four minutes was the average time taken to reform a column across the ten feet of open clay, with all the road-making and engineering feats which I have mentioned, on the part of ants who had never been over this new route before.

Leaning forward within a few inches of the post, I lost all sense of proportion, forgot my awkward human size, and with a new perspective became an equal of the ants, looking on,[67] watching every passer-by with interest, straining with the bearers of the heavy loads, and breathing more easily when the last obstacle was overcome and home attained. For a period I plucked out every bit of good-sized booty and found that almost all were portions of scorpions from far-distant dead logs in the jungle, creatures whose strength and poisonous stings availed nothing against the attacks of these fierce ants. The loads were adjusted equably, the larger pieces carried by the big, white-headed workers, while the smaller ants transported small eggs and larvæ. Often, when a great mandibled soldier had hold of some insect, he would have five or six tiny workers surrounding him, each grasping any projecting part of the loot, as if they did not trust him in this menial capacity,—as an anxious mother would watch with doubtful confidence a big policeman wheeling her baby across a crowded street. These workers were often diminutive Marcelines, hindering rather than aiding in the progress. But in every phase of activity of these ants there was not an ounce of intentionally lost power, or a moment of time wilfully gone to waste. What a commentary on Bolshevism![68]

Now that I had the opportunity of quietly watching the long, hurrying columns, I came hour by hour to feel a greater intimacy, a deeper enthusiasm for their vigor of existence, their unfailing life at the highest point of possibility of achievement. In every direction my former desultory observations were discounted by still greater accomplishments. Elsewhere I have recorded the average speed as two and a half feet in ten seconds, estimating this as a mile in three and a half hours. An observant colonel in the American army has laid bare my congenitally hopeless mathematical inaccuracy, and corrected this to five hours and fifty-two seconds. Now, however, I established a wholly new record for the straight-away dash for home of the army ants. With the handicap of gravity pulling them down, the ants, both laden and unburdened, averaged ten feet in twenty seconds, as they raced up the post. I have now called in an artist and an astronomer to verify my results, these two being the only living beings within hailing distance as I write, except a baby red howling monkey curled up in my lap, and a toucan, sloth, and green boa, beyond my laboratory table. Our results are identical, and I can safely announce that the[69] amateur record for speed of army ants is equivalent to a mile in two hours and fifty-six seconds; and this when handicapped by gravity and burdens of food, but with the incentive of approaching the end of their long journey.

As once before, I accidentally disabled a big worker that I was robbing of his load, and his entire abdomen rolled down a slope and disappeared. Hours later in the afternoon, I was summoned to view the same soldier, unconcernedly making his way along an outward-bound column, guarding it as carefully as if he had not lost the major part of his anatomy. His mandibles were ready, and the only difference that I could see was that he could make better speed than others of his caste. That night he joined the general assemblage of cripples quietly awaiting death, halfway up to the nest.