The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Immortal, by Alphonse Daudet

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Immortal

Or, One Of The "Forty." (L'immortel) - 1877

Author: Alphonse Daudet

Translator: A. W. Verrall And Margaret D. G. Verrall

Release Date: June 12, 2008 [EBook #25766]

Last Updated: October 1, 2016

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE IMMORTAL ***

Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

IMMORTAL; OR, THE “FORTY.” (L’IMMORTEL)

Illustrations

At the Corner of The Quai D’orsay

A Select Reception, at the Padovani Mansion

Seem As Easy As the Hovering of a Dragon-fly

Pressed Upon Her Half-open Lips a Long, Long Kiss

There, Under the Black-draped Porch

Passed a Tall Figure Bent Double

Well, by Your Schemes I Have Lost a Million

With the Help of Fage The Bookbinder

Good Wine is the Only Real Good in Life.

Danjou Read Like a Genuine ‘player’

In the 1880 edition of Men of the Day, under the heading Astier-Réhu, may be read the following notice:—

Astier, commonly called Astier-Réhu (Pierre Alexandre Léonard), Member of the Académie Française, was born in 1816 at Sauvagnat (Puy-de-Dôme). His parents belonged to the class of small farmers. He displayed from his earliest years a remarkable aptitude for the study of history. His education, begun at Riom and continued at Louis-le-Grand, where he was afterwards to re-appear as professor, was more sound than is now fashionable, and secured his admission to the Ecole Normale Supérieure, from which he went to the Chair of History at the Lycée of Mende. It was here that he wrote the Essay on Marcus Aurelius, crowned by the Académie Française. Called to Paris the following year by M. de Salvandy, the young and brilliant professor showed his sense of the discerning favour extended to him by publishing, in rapid succession, The Great Ministers of Louis XIV. (crowned by the Académie Française), Bonaparte and the Concordat (crowned by the Académie Française), and the admirable Introduction to the History of the House of Orleans, a magnificent prologue to the work which was to occupy twenty years of his life. This time the Académie, having no more crowns to offer him, gave him a seat among its members. He could scarcely be called a stranger there, having married Mlle. Rèhu, daughter of the lamented Paulin Réhu, the celebrated architect, member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and granddaughter of the highly respected Jean Réhu, the father of the Académie Française, the elegant translator of Ovid and author of the Letters to Urania, whose hale old age is the miracle of the Institute. By his friend and colleague M. Thiers Léonard Astier-Réhu was called to the post of Keeper of the Archives of Foreign Affairs. It is well known that, with a noble disregard of his interests, he resigned, some years later (1878), rather than that the impartial pen of history should stoop to the demands of our present rulers. But deprived of his beloved archives, the author has turned his leisure to good account. In two years he has given us the last three volumes of his history, and announces shortly New Lights on Galileo, based upon documents extremely curious and absolutely unpublished. All the works of Astier-Réhu may be had of Petit-Séquard, Bookseller to the Académie.

As the publisher of this book of reference entrusts to each person concerned the task of telling his own story, no doubt can possibly be thrown upon the authenticity of these biographical notes. But why must it be asserted that Léonard Astier-Réhu resigned his post as Keeper of the Archives? Every one knows that he was dismissed, sent away with no more ceremony than a hackney-cabman, because of an imprudent phrase let slip by the historian of the House of Orleans, vol. v. p. 327: ‘Then, as to-day, France, overwhelmed by the flood of demagogy, etc.’ Who can see the end of a metaphor? His salary of five hundred pounds a year, his rooms in the Quai d’Orsay (with coals and gas) and, besides, that wonderful treasure of historic documents, which had supplied the sap of his books, all this had been carried away from him by this unlucky ‘flood,’ all by his own flood! The poor man could not get over it. Even after the lapse of two years, regret for the ease and the honours of his office gnawed at his heart, and gnawed with a sharper tooth on certain dates, certain days of the month or the week, and above all on ‘Teyssèdre’s Wednesdays.’ Teyssèdre was the man who polished the floors. He came to the Astiers’ regularly every Wednesday. On the afternoon of that day Madame Astier was at home to her friends in her husband’s study, this being the only presentable apartment of their third floor in the Rue de Beaune, the remains of a grand house, terribly inconvenient in spite of its magnificent ceiling. The disturbance caused to the illustrious historian by this ‘Wednesday,’ recurring every week and interrupting his industrious and methodical labours, may easily be conceived. He had come to hate the rubber of floor, a man from his own country, with a face as yellow, close, and hard as his own cake of beeswax. He hated Teyssèdre, who, proud of coming from Riom, while ‘Meuchieu Achtier came only from Chauvagnat,’ had no scruple in pushing about the heavy table covered with pamphlets, notes, and reports, and hunted the illustrious victim from room to room till he was driven to seek refuge in a kind of pigeon-hole over the study, where, though not a big man, he must sit for want of room to get up. This lumber-closet, which was furnished with an old damask chair, an aged card-table and a stand of drawers, looked out on the courtyard through the upper circle of the great window belonging to the room below. Through this opening, much resembling the low glass door of an orangery, the travailing historian might be seen from head to foot, miserably doubled up like Cardinal La Balue in his cage. It was here that he was sitting one morning with his eyes upon an ancient scrawl, having been already expelled from the lower room by the bang-bang-bang of Teyssèdre, when he heard the sound of the front door bell.

‘Is that you, Fage?’ asked the Academician in his deep and resonant bass.

‘No, Meuchieu Achtier. It is the young gentleman.’

On Wednesday mornings the polisher opened the door, because Corentine was dressing her mistress.

‘How’s The Master?’ cried Paul Astier, hurrying by to his mother’s room. The Academician did not answer. His son’s habit of using ironically a title generally bestowed upon him as a compliment was always offensive to him.

‘M. Fage is to be shown up as soon as he comes,’ he said, not addressing himself directly to the polisher.

‘Yes, Meuchieu Achtier.’ And the bang-bang-bang began again.

‘Good morning, mamma.’

‘Why, it’s Paul! Come in. Mind the folds, Corentine.’

Madame Astier was putting on a skirt before the looking-glass. She was tall, slender, and still good-looking in spite of her worn features and her too delicate skin. She did not move, but held out to him a cheek with a velvet surface of powder. He touched it with his fair pointed beard. The son was as little demonstrative as the mother.

‘Will M. Paul stay to breakfast?’ asked Corentine. She was a stout countrywoman of an oily complexion, pitted with smallpox. She was sitting on the carpet like a shepherdess in the fields, and was about to repair, at the hem of the skirt, her mistress’s old black dress. Her tone and her attitude showed the objectionable familiarity of the under-paid maid-of-all-work.

No, Paul would not stay to breakfast. He was expected elsewhere. He had his buggy below; he had only come to say a word to his mother.

‘Your new English cart? Let me look,’ said Madame Astier. She went to the open window, and parted the Venetian blinds, on which the bright May sunlight lay in stripes, just far enough to see the neat little vehicle, shining with new leather and polished pinewood, and the servant in spotless livery standing at the horse’s head.

‘Oh, ma’am, how beautiful!’ murmured Coren-tine, who was also at the window. ‘How nice M. Paul must look in it!’

The mother’s face shone. But windows were opening opposite, and people were stopping before the equipage, which was creating quite a sensation at this end of the Rue de Beaune. Madame Astier sent away the servant, seated herself on the edge of a folding-chair, and finished mending her skirt for herself, while she waited for what her son had to say to her, not without a suspicion what it would be, though her attention seemed to be absorbed in her sewing. Paul Astier was equally silent. He leaned back in an arm-chair and played with an ivory fan, an old thing which he had known for his mother’s ever since he was born. Seen thus, the likeness between them was striking; the same Creole skin, pink over a delicate duskiness, the same supple figure, the same impenetrable grey eye, and in both faces a slight defect hardly to be noticed; the finely-cut nose was a little out of line, giving an expression of slyness, of something not to be trusted. While each watched and waited for the other, the pause was filled by the distant brushing of Teyssèdre.

‘Rather good, that,’ said Paul.

His mother looked up. ‘What is rather good?’

He raised the fan and pointed, like an artist, at the bare arms and the line of the falling shoulders under the fine cambric bodice. She began to laugh.

‘Yes, but look here.’ She pointed to her long neck, where the fine wrinkles marked her age. ‘But after all,’... you have the good looks, so what does it matter? Such was her thought, but she did not express it. A brilliant talker, perfectly trained in the fibs and commonplaces of society, a perfect adept in expression and suggestion, she was left without words for the only real feeling which she had ever experienced. And indeed she really was not one of those women who cannot make up their minds to grow old. Long before the hour of curfew—though indeed there had perhaps never been much fire in her to put out—all her coquetry, all her feminine eagerness to captivate and charm, all her aspirations towards fame or fashion or social success had been transferred to the account of her son, this tall, good-looking young fellow in the correct attire of the modern artist, with his slight beard and close-cut hair, who showed in mien and bearing that soldierly grace which our young men of the day get from their service as volunteers.

‘Is your first floor let?’ asked the mother at last.

‘Let! let! Not a sign of it! All the bills and advertisements no go! “I don’t know what is the matter with them; but they don’t come,” as Védrine said at his private exhibition.’

He laughed quietly, at an inward vision of Védrine among his enamels and his sculptures, calm, proud, and self-assured, wondering without anger at the non-appearance of the public. But Madame Astier did not laugh. That splendid first floor empty for the last two years! In the Rue Fortuny! A magnificent situation—a house in the style of Louis XII.—a house built by her son! Why, what did people want? The same people, doubtless, who did not go to Védrine. Biting off the thread with which she had been sewing, she said:

‘And it is worth taking, too!’

‘Quite; but it would want money to keep it up.’

The people at the Crédit Foncier would not be satisfied. And the contractors were upon him—four hundred pounds for carpenter’s work due at the end of the month, and he hadn’t a penny of it.

The mother, who was putting on the bodice of her dress before the looking-glass, grew pale and saw that she did so. It was the shiver that you feel in a duel, when your adversary raises his pistol to take aim.

‘You have had the money for the restorations at Mousseaux?’

‘Mousseaux! Long ago.’

‘And the Rosen tomb?’

‘Can’t get on. Védrine still at his statue.’

‘Yes, and why must you have Védrine? Your father warned you against him.’

‘Oh, I know. They can’t bear him at the Institute.’

He rose and walked about the room.

‘You know me, come. I am a practical man. If I took him and not some one else to do my statue, you may suppose that I had a reason.’ Then suddenly, turning to his mother:

‘You could not let me have four hundred pounds, I suppose?’ She had been waiting for this ever since he came in; he never came to see her for anything else.

‘Four hundred pounds? How can you think——’ She said no more; but the pained expression of her mouth and eyes said clearly enough:

‘You know that I have given you everything—that I am dressed in clothes fit for the rag-bag—that I have not bought a bonnet for three years—that Corentine washes my linen in the kitchen because I should blush to give such rubbish to the laundress; and you know also that my worst misery is to refuse what you ask. Then why do you ask?’ And this mute address of his mother’s was so eloquent that Paul Astier answered it aloud:

‘Of course I was not thinking of your having it yourself. By Jove, if you had, it would be the better for me. But,’ he continued, in his cool, off hand way, ‘there is The Master up there. Could you get it from him? You might. You know how to get hold of him.’

‘That is over. There is an end of that.’

‘Well, but, you know, he works; his books sell; you spend nothing.’

He looked round in the subdued light at the reduced state of the old furniture, the worn curtains, the threadbare carpet, nothing of later date than their marriage thirty years ago. Where was it then that all the money went?

‘I say,’ he began again, ‘I wonder whether my venerable sire is in the habit of taking his fling?’

It was an idea so monstrous, so inconceivable, that of Léonard Astier-Réhu ‘taking his fling,’ that his wife could not help smiling in spite of herself. No, on that point she thought there was no need for uneasiness. ‘Only, you know, he has turned suspicious and mysterious, and “buries his hoard.” We have gone too far with him.’

They spoke low, like conspirators, with their eyes upon the carpet.

‘And grandpapa,’ said Paul, but not in a tone of confidence, ‘could you try him?’

‘Grandpapa? You must be mad!’

Yet he knew well enough what old Réhu was. A touchy, selfish man all but a hundred years old, who would have seen them all die rather than deprive himself of a pinch of snuff or a single one of the pins that were always stuck on the lapels of his coat. Ah, poor child! He must be hard up indeed before he could think of his grandfather.

‘Well, you would not like me to try —— ——.’ She paused.

‘To try where?’

‘In the Rue de Courcelles. I might get something in advance for the tomb.’

‘There? Good Heavens! You had better not!’

He spoke to her imperiously, with pale lips and a disagreeable expression in his eye; then recovering his self-contained and fleeting tone, he said:

‘Don’t trouble any more about it. It is only a crisis to be got through. I have had plenty before now.’

She held out to him his hat, which he was looking for. As he could get nothing from her, he would be off. To keep him a few minutes longer, she began talking of an important business which she had in hand—a marriage, which she had been asked to arrange.

At the word marriage he started and looked at her askance: ‘Who was it?’ She had promised to say nothing at present. But she could not refuse him. It was the Prince d’Athis.

‘Who is the lady?’ he asked.

It was her turn now to show him the side view of her crooked nose.

‘You do not know the lady. She is a foreigner with a fortune. If I succeed I might help you. I have made my terms in black and white.’

He smiled, completely reassured.

‘And how does the Duchess take it?’

‘She knows nothing of it, of course.’

‘Her Sammy,’ Her dear prince! And after fifteen years!’

Madame Astier’s gesture expressed the utter carelessness of one woman for the feelings of another.

‘What else could she expect at her age?’ said she.

‘Why, what is her age?’

‘She was born in 1827. We are in 1880. You can do the sum. Just a year older than myself.’

‘The Duchess!’ cried Paul, stupefied.

His mother laughed as she said, ‘Why, yes, you rude boy! What are you surprised at? I am sure you thought her twenty years younger. It’s a fact, it seems, that the most experienced of you know nothing about women. Well, you see, the poor prince could not have her hanging on to him all his life. Besides, one of these days the old Duke will die, and then where would he be? Fancy him tied to that old woman!’

‘Well,’ said Paul, ‘so much for your dear friend!’ She fired at this. Her dear friend! The Duchess! A pretty friend! A woman who, with twenty-five thousand a year—intimate as she was with her, and well aware of their difficulties—had never so much as thought of helping them! What was the present of an occasional dress? Or the permission to choose a bonnet at her milliner’s? Presents for use! There was no pleasure in them.

‘Like grandpapa Réhu’s on New Year’s day,’ put in Paul assenting. ‘An atlas, or a globe!’

‘Oh, Antonia is, I really think, more stingy still. When we were at Mousseaux, in the middle of the fruit season, if Sammy was not there, do you remember the dry plums they gave us for dessert? There is plenty in the orchard and the kitchen garden, but everything is sent to market at Blois or Vendôme. It runs in her blood, you know. Her father, the Marshal, was famous for it at the Court of Louis Philippe; and it was something to be thought stingy at the Court of Louis Philippe! These great Corsican families are all alike; nothing but meanness and pretension! They will eat chestnuts, such as the pigs would not touch, off plate with their arms on it. And as for the Duchess—why, she makes her steward account to her in person! They take the meat up to her every morning; and every evening (this is from a person who knows), when she has gone to her grand bed with the lace, at that tender moment she balances her books!’

Madame Astier was nearly breathless. Her small voice grew sharp and shrill, like the cry of a sea-bird from the masthead. Meanwhile Paul, amused at first, had begun to listen impatiently, with his thoughts elsewhere. ‘I am off,’ said he abruptly. ‘I have a breakfast with some business people—very important.’

‘An order?’

‘No, not architect’s business this time.’

She wanted him to satisfy her curiosity, but he went on, ‘Not now; another time; it’s not settled.’ And finally, as he gave his mother a little kiss, he whispered in her ear, ‘All the same, do not forget my four hundred.’

But for this grown-up son, who was a secret cause of division, the Astier-Réhu would have had a happy household, as the world, and in particular the Academic world, measures household happiness. After thirty years their mutual sentiments remained the same, kept beneath the snow at the temperature of what gardeners call a ‘cold-bed.’ When, about ‘50, Professor Astier, after brilliant successes at the Institute, sued for the hand of Mademoiselle Adelaide Réhu, who at that time lived with her grandfather at the Palais Mazarin, it was not the delicate and slender beauty of his betrothed, it was not the bloom of her ‘Aurora’ face, which were the real attractions for him. Neither was it her fortune. For the parents of Mademoiselle Adelaide, who died suddenly of cholera, had left her but little; and the grandfather, a Creole from Martinique, an old beau of the time of the Directory, a gambler, a free liver, great in practical jokes and in duels, declared loudly and repeatedly that he should not add a penny to her slender portion.

No, that which enticed the scion of Sauvagnat, who was far more ambitious than greedy, was the Académie. The two great courtyards which he had to cross to bring his daily offering of flowers, and the long solemn corridors into which at intervals there descended a dusty staircase, were for him rather the path of glory than of love. The Paulin Réhu of the Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, the Jean Réhu of the ‘Letters to Urania,’ the Institute complete with its lions and its cupola—this was the Mecca of his pilgrimage, and all this it was that he took to wife on his wedding day.

For this not transient beauty he felt a passion proof against the tooth of time, a passion which took such hold of him that his permanent attitude towards his wife was that of those mortal husbands on whom, in the mythological age, the gods occasionally bestowed their daughters. Nor did he quit this respect when at the fourth ballot he had himself become a deity. As for Madame Astier, who had only accepted marriage as a means of escape from a hard and selfish grandfather in his anecdotage, it had not taken her long to find out how poor was the laborious peasant brain, how narrow the intelligence, concealed by the solemn manners of the Academic laureate and manufacturer of octavos, and by his voice with its ophicleide notes adapted to the sublimities of the lecture room. And yet when, by force of intrigue, bargaining, and begging, she had seated him at last in the Académie, she felt herself possessed by a certain veneration, forgetting that it was herself who had clothed him in that coat with the green palm leaves, in which his nothingness ceased to be visible.

In the dull concord of their partnership, where was neither joy, nor intimacy, nor communion of any kind, there was but one single note of natural human feeling, their child; and this note disturbed the harmony. In the first place the father was entirely disappointed of all that he wished for his son, that he should be distinguished by the University, entered for the general examinations, and finally pass through the Ecole Normale to a professorship. Alas! at school Paul took prizes for nothing but gymnastics and fencing, and distinguished himself chiefly by a wilful and obstinate perversity, which covered a practical turn of mind and a precocious understanding of the world. Careful of his dress and his appearance, he never went for a walk without the hope, of which he made no secret to his schoolfellows, of ‘picking up a rich wife.’ Two or three times the father had been ready to punish this determined idleness after the rough method of Auvergne, but the mother was by to excuse and to protect. In vain Astier-Réhu scolded and snapped his jaw, a prominent feature which, in the days when he was a professor, had gained him the nickname of Crocodilus. In the last resort, he would threaten to pack his trunk and go back to his vineyard at Sauvagnat.

‘Ah, Léonard, Léonard!’ Madame Astier would say with gentle mockery; and nothing further came of it. Once, however, he really came near to strapping his trunk in good earnest, when, after a three years’ course of architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paul refused to compete for the Prix de Rome. The father could scarcely speak for indignation. ‘Wretched boy! It is the Prix de Rome! You cannot know; you do not understand. The Prix de Rome! Get that, and it means the Institute!’ Little the young man cared. What he wanted was wealth, and wealth the Institute does not bestow, as might be seen in his father, his grandfather, and old Réhu, his great-grandfather! To start in life, to get a business, a large business, an immediate income—this was what he wanted for his part, and not to wear a green coat with palms on it.

Léonard Astier was speechless. To hear such blasphemies uttered by his son and approved by his wife, a daughter of the house of Réhu! This time his trunk was really brought down from the box room; his old trunk, such as professors use in the provinces, with as much ironwork in the way of nails and hinges as might have sufficed for a church door, and high enough and deep enough to have held the enormous manuscript of ‘Marcus Aurelius’ together with all the dreams of glory and all the ambitious hopes of an historian on the high road to the Académie. It was in vain for Madame Astier to pinch her lips and say, ‘Oh, Léonard, Léonard!’ Nothing would stop him till his trunk was packed. Two days it stood in the way in the middle of his study. Then it travelled to the ante-room; and there reposed, turned once and for ever into a wood-box.

And at first, it must be said, Paul Astier did splendidly. Helped by his mother and her connection in good society, and further assisted by his own cleverness and personal charm, he soon got work which brought him into notice. The Duchess Padovani, wife of a former ambassador and minister, trusted him with the restoration of her much admired country house at Mousseaux-on-the-Loire, an ancient royal residence, long neglected, which he succeeded in restoring with a skill and ingenuity really amazing in an undistinguished scholar of the Beaux-Arts. Mousseaux got him the order for the new mansion of the Ambassador of the Porte; and finally the Princess of Rosen commissioned him to design the mausoleum of Prince Herbert of Rosen, who had come to a tragic end in the expedition of Christian of Illyria. The young man now thought himself sure of success. Astier the elder was induced by his wife to put down three thousand pounds out of his savings for the purchase of a site in the Rue Fortuny. Then Paul built himself a mansion—or rather, a wing to a mansion, which was itself arranged as a block of elegant ‘rooms to let.’ He was a practical young fellow, and if he wanted a mansion, without which no artist is chic, he meant it to bring him an income.

Unfortunately houses to let are not always so easy to let, and the young architect’s way of life, with two horses in his stable (one for harness, one for the saddle), his club, his visiting, his slow reimbursements, made it impossible for him to wait. Moreover, the elder Astier suddenly declared that he was not going to give any more; and all that the mother could attempt or say for her darling son failed to shake this irrevocable decision. Her will, which had hitherto swayed the establishment, was now resisted. Thenceforward there was a continual struggle. The mother used her ingenuity to make little dishonest profits on the household expenses, that she might never have to say ‘no’ to her son’s requests. Léonard suspected her and, to protect himself, checked the accounts. In these humiliating conflicts the wife, who was the better bred, was the first to tire; and nothing less than the desperate situation of her beloved Paul would have induced her to make a fresh attempt.

She went slowly into the dining room. It was a long, melancholy room, ill lighted by tall, narrow windows, having in fact been used as a table d’hôte for ecclesiastics until the Astiers took it. There she found her husband already at table, looking preoccupied and almost grumpy. In the ordinary way ‘the Master’ came to his meals with a smiling serenity as regular as his appetite, and with teeth which, sound as a foxhound’s, were not to be discouraged by stale bread or leathery meat, or by the miscellaneous disagreeables which are the everyday flavouring of life.

‘Ah, it’s Teyssèdre’s day,’ thought Madame Astier, as she took her seat, her best dress rustling as she did so. She was a little surprised at not receiving the compliment with which her husband never failed to welcome her ‘Wednesday’ costume, shabby as it was. Reckoning that this bad temper would go off with the first mouthfuls, she waited before beginning her attack. But, though the Master went on eating, his ill humour visibly increased. Everything was wrong; the wine tasted of the cork; the balls of boiled beef were burnt.

‘And all because your M. Fage kept you waiting this morning,’ cried Corentine angrily from the adjoining kitchen. She showed her shiny pitted face for a moment at the hatch in the wall through which, in the days of the table d’hôte, they used to pass the dishes. She shut it with a bang; upon which Astier muttered, ‘Really that girl’s impudence——’ He was in truth much annoyed that the name of Fage had been mentioned before his wife. And sure enough at any other moment Madame Astier would not have failed to say, ‘Oh, Fage the bookbinder here again!’ and there would have followed a domestic scene; on all which Corentine reckoned when she threw in her artful speech. To-day, however, it was all-important that the master should not be irritated, but prepared by skilful stages for the intended petition. He was talked to, for instance, about the health of Loisillon, the perpetual secretary of the Académie, who, it seemed, was getting worse and worse. Loisillon’s post and his rooms in the Institute were to come to Léonard Astier as a compensation for the office which he had lost; and though he was really attached to his dying colleague, still the prospect of a good salary, an airy and comfortable residence, and other advantages had its attractions. He was perhaps ashamed to think of the death in this light, but in the privacy of his household he did so without blinking. But to-day even that did not bring a smile. ‘Poor M. Loisillon!’ said Madame Astier’s thin voice; ‘he begins to be uncertain about his words. La vaux was telling us yesterday at the Duchess’s, he can only say “a cu-curiosity, a cu-curiosity,” and,’ she added, compressing her lips and drawing up her long neck, ‘he is on the Dictionary Committee.’

Astier-Réhu did not move an eyebrow.

‘It is not a bad story,’ said he, clapping his jaw with a magisterial air. ‘But, as I have said somewhere in my history, in France the provisional is the only thing that lasts. Loisillon has been dying any time this ten years. He’ll see every one of us buried yet—every one of us,’ he repeated angrily, pulling at his dry bread. It was clear that Teyssèdre had put him into a very bad temper indeed.

Madame Astier went to another subject, the special meeting of all the five Académies, which was to take place within a few days, and to be honoured by the presence of the Grand Duke Leopold of Finland. It so happened that Astier-Réhu, being director for the coming quarter, was to preside at the meeting and to deliver the opening speech, in which his Highness was to receive a compliment. Skilfully questioned about this speech, which he was already planning, Léonard described it in outline. It was to be a crushing attack upon the modern school of literature—a sound thrashing administered in public to these pretenders, these dunces. And at this his eyes, big with his heavy meal, lighted up his square face, and the blood rose under his thick bushy eyebrows. They were still coal-black, and contrasted strangely with the white circle of his beard.

‘By the way,’ said he suddenly, ‘what about my uniform coat? Has it been seen to? The last time I wore it, at Montribot’s funeral——’

But do not women think of everything? Madame Astier had seen to the coat that very morning. The silk of the palm leaves was getting shabby; the lining was all to pieces. It was very old. Oh, dear, when did he wear it first? Why, it was as long ago—as long ago—as when he was admitted! The twelfth of October, eighteen-sixty-six! He had better order a new one for the Meeting. The five Académies, a Royal Highness, and all Paris! Such an audience was worth a new coat. Léonard protested, not energetically, on the ground of expense. With a new coat he would want a new waistcoat; knee-breeches were not worn now, but a new waistcoat would be indispensable.

‘My dear, you really must!’ She continued to press him. If they did not take care they would make themselves ridiculous with their economy. There were too many shabby old things about them. The furniture of her room, for instance! It made her feel ashamed when a friend came in, and for a sum comparatively trifling.

‘Ouais! quelque sot,’ muttered Astier-Réhu, who liked to quote his classics. The furrow in his forehead deepened, and under it, as under the bar of a shutter, his countenance, which had been open for a minute, shut up. Many a time had he supplied the means to pay a milliner’s bill, or a dressmaker’s, or to re-paper the walls, and after all no account had been settled and no purchase made. All the money had gone to that Charybdis in the Rue Fortuny. He had had enough of it, and was not going to be caught again. He rounded his back, fixed his eyes upon the huge slice of Auvergne cheese which filled his plate, and said no more.

Madame Astier was familiar with this dogged silence. This attitude of passive resistance, dead as a ball of cotton, was always put on when money was mentioned. But this time she was resolved to make him answer. ‘Ah,’ she said, ‘I see you rolling up, Master Hedgehog. I know the meaning of that. “Nothing to be got! nothing to be got! No, no, no!” Eh?’ The back grew rounder and rounder. ‘But you can find money for M. Fage.’ Astier started, sat up, and looked uneasily at his wife. Money for M. Fage? What did she mean?’ Why, of course,’ she went on, delighted to have forced the barrier of his silence, ‘of course it takes money to do all that binding. And what’s the good of it, I should like to know, for all those old scraps?’

He felt relieved; evidently she knew nothing; it was only a chance shot.

But the term ‘old scraps’ went to his heart: unique autograph documents, signed letters of Richelieu, Colbert, Newton, Galileo, Pascal, marvels bought for an old song, and worth a fortune. ‘Yes, madam, a fortune.’ He grew excited, and began to quote figures, the offers that had been made him. Bos, the famous Bos of the Rue de l’Abbaye (and he knew his business if any one did), Bos had offered him eight hundred pounds merely for three specimens from his collection—three letters from Charles the Fifth to François Rabelais. Old scraps indeed!

Madame Astier listened in utter amazement. She was well aware that for the last two or three years he had been collecting old manuscripts. He used sometimes to speak to her of his finds, and she listened in a wandering absent-minded way, as a woman does listen to a man’s voice when she has heard it for thirty years. But this was beyond her conception. Eight hundred pounds for three letters! And why did he not take it?’

He burst out like an explosion of dynamite.

‘Sell my Charles the Fifths! Never! I would see you all without bread and begging from door to door before I would touch them—understand that!’ He struck the table. His face was very pale, and his lips thrust out This fierce maniac was an Astier-Réhu whom his wife did not know. In the sudden glow of a passion human beings do thus take aspects unknown to those who know them best The next minute the Academician was quite calm, again, and was explaining, not without embarrassment, that these documents were indispensable to him as an author, especially now that he could not command the Records of the Foreign Office. To sell these materials would be to give up writing. On the contrary, he hoped to make additions to them. Then, with a touch of bitterness and affection, which betrayed the whole depth of the father’s disappointment, he said, ‘After my time, my fine gentleman of a son may sell them if he chooses; and since all he wants is to be rich, I will answer for it that he will be.’

‘Yes; but meanwhile——’

This ‘meanwhile’ was said in a little flute-like voice so cruelly natural and quiet that Léonard, unable to control his jealousy of this son who left him no place in his wife’s heart, retorted with a solemn snap of the jaw, ‘Meanwhile, madam, others can do as I do. I have no mansion, I keep no horses and no English cart. The tramway does for my going and coming, and I am content to live on a third floor over an entresol, where I am exposed to Teyssèdre. I work night and day, I pile up volume after volume, two and three octavos in a year. I am on two committees of the Académie; I never miss a meeting; I never miss a funeral; and even in the summer I never accept an invitation to the country, lest I should miss a single tally. I hope my son, when he is sixty-five, may be as indefatigable.’

It was long since he had spoken of Paul, and never had he spoken so severely. The mother was struck by his tone, and in her look, as she glanced sidelong, almost wickedly, at her husband, there was a shade of respect, which had not been there before.

‘There is a ring,’ said Léonard eagerly, rising as he spoke, and flinging his table napkin upon the back of his chair. ‘That must be my man.’

‘It’s some one for you, ma’am; they are beginning early to-day,’ said Corentine, as, with her kitchen-maid’s fingers wiped hastily on her apron, she laid a card on the edge of the table. Madame Astier looked at it. ‘The Vicomte de Freydet.’ A gleam came into her eyes. But her delight was not perceptible in the calm tone in which she said, ‘So M. de Freydet is in Paris?’

‘Yes, about his book.’

‘Bless me! His book! I have not even cut it. What is it about?’

She hurried over the last mouth fuls, and washed the tips of her white fingers in her glass while her husband in an absent-minded way gave her some idea of the new volume. ‘God in Nature,’ a philosophic poem, entered for the Boisseau prize.

‘Oh, I do hope he will get it. He must, he must. They are so nice, he and his sister, and he is so good to the poor paralysed creature. Do you think he will?’

Astier would not commit himself. He could not promise, but he would certainly recommend Freydet, who seemed to him to be really improving. ‘If he asks you for my personal opinion, it is this: there is still a little too much for my taste, but much less than in his other books. You may tell him that his old master is pleased.’

Too much of what? Less of what? It must be supposed that Madame Astier knew, for she sought no explanation, but left the table and passed, quite happy, into her drawing room—as the study must be considered for the day. Astier, more and more absorbed in thought, lingered for some minutes, breaking up with his knife what remained in his plate of the Auvergne cheese; then, being disturbed in his meditations by Corentine, who, without heeding him, was rapidly clearing the table, he rose stiffly and went up, by a little staircase like a cat-ladder, to his attic, where he took up his magnifying glass and resumed the examination of the old manuscript upon which he had been busy since the morning.

SITTING straight, with the reins well held up in the most correct fashion, Paul Astier drove his two-wheeled cart at a stiff pace to the scene of his mysterious breakfast ‘with some business people.’ ‘Tclk! tclk!’ Past the Pont Royal, past the quays, past the Place de la Concorde. The road was so smooth, the day so fine, that as terraces, trees, and fountains went by, it would have needed but a little imagination on his part to believe himself carried away on the wings of Fortune. But the young man was no visionary, and as he bowled along he examined the new leather and straps, and put questions about the hay-merchant to his groom, a young fellow perched at his side looking as cool and as sharp as a stable terrier. The hay-merchant, it seemed, was as bad as the rest of them, and grumbled about supplying the fodder.

‘Oh, does he?’ said Paul absently; his mind had already passed to another subject. His mother’s revelations ran in his head. Fifty-three years old! The beautiful Duchess Antonia, whose neck and shoulders were the despair of Paris! Utterly incredible! ‘Tclk! tclk!’ He pictured her at Mousseaux last summer, rising earlier than any of her guests, wandering with her dogs in the park while the dew was still on the ground, with loosened hair and blooming lips; she did not look made up, not a bit. Fifty-three years old? Impossible!

‘Tclk, tclk! Hi! Hi!’ That’s a nasty corner between the Rond Pont and the Avenue d’Antin.—All the same, it was a low trick they were playing her, to find a wife for the Prince. For let his mother say what she would, the Duchess and her drawing-room had been a fine thing for them all. Perhaps his father might never have been in the Académie but for her; he himself owed her all his commissions. Then there was the succession to Loisillon’s place and the prospect of the fine rooms under the cupola—well, there was nothing like a woman for flinging you over. Not that men were any better; the Prince d’Athis, for instance. To think what the Duchess had done for him! When they met he was a ruined and penniless rip; now what was he? High in the diplomatic service, member of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, on account of a book not a word of which he had written himself, ‘The Mission of Woman in the World’. And while the Duchess was busily at work to fit him with an Embassy, he was only waiting to be gazetted before taking French leave and playing off this dirty trick on her, after fifteen years of uninterrupted happiness. ‘The mission of woman in the world!’ Well, the Prince understood what the mission of woman was. The next thing was to better the lesson. ‘Tclk! tclk! Gate, please.’

Paul’s soliloquy was over, and his cart drew up before a mansion in the Rue de Courcelles. The double gates were rolled, back slowly and heavily as if accomplishing a task to which they had long been unused.

In this house lived the Princess Colette de Rosen, who had shut herself up in the complete seclusion of mourning since the sad occurrence which had made her a widow at twenty-six. The daily papers recorded the details of the young widow’s sensational despair: how the fair hair was cut off close and thrown into the coffin; how her room was decorated as for a lying in state; how she took her meals alone with two places laid, while on the table in the anteroom lay as usual the Prince’s walking stick, hat, and gloves, as though he were at home and just going out. But one detail had not been mentioned, and that was the devoted affection and truly maternal care which Madame Astier showed for the ‘poor little woman’ in these distressing circumstances.

Their friendship had begun some years ago, when a prize for an historical work had been adjudged to the Prince de Rosen by the Académie, ‘on the report of Astier-Réhu.’ Differences of age and social position had however kept them apart until the Princess’s mourning removed the barrier. When the widow’s door was solemnly closed against society, Madame Astier alone escaped the interdict. Madame Astier was the only person allowed to cross the threshold of the mansion, or rather the convent, inhabited by the poor weeping Carmelite with her shaven head and robe of black; Madame Astier was the only person admitted to hear the mass sung twice a week at St. Philip’s for the repose of Herbert’s soul; and it was she who heard the letters which Colette wrote every evening to her absent husband, relating her life and the way she spent her days. All mourning, however rigid, involves attention to material details which are degrading to grief but demanded by society. Liveries must be ordered, trappings provided for horses and carriages, and the heartbroken mourner must face the hypocritical sympathy of the tradesman. All these duties were discharged by Madame Astier with never-failing patience. She undertook the heavy task of managing the household, which the tear-laden eyes of its fair mistress could no longer supervise, and so spared the young widow all that could disturb her despair, or disarrange her hours for praying, weeping, writing ‘to him,’ and carrying armfuls of exotic flowers to the cemetery of Père Lachaise, where Paul Astier was superintending the erection of a gigantic mausoleum in commemorative stone brought at the express wish of the Princess from the scene of the tragedy.

Unfortunately the quarrying of this stone and its conveyance from Illyria, the difficulties of carving granite, and the endless plans and varying fancies of the widow, to whom nothing seemed sufficiently huge and magnificent to suit her dead hero, had brought about many hitches and delays. So it happened that in May 1880, two years and more after the catastrophe and the commencement of the work, the monument was still unfinished. Two years is a long time to maintain the constant paroxysms of an ostentatious grief, each sufficient to discharge the whole. The mourning was still observed as rigidly as ever, the house was still closed and silent as a cave. But in the place of the living statue weeping and praying in the furthest recesses of the crypt was now a pretty young woman whose hair was growing again, instinct with life in every curl and wave of its soft luxuriance. The reappearance of this fair hair gave a touch of lightness, almost of brightness, to the widow’s mourning, which seemed now no more than a caprice of fashion. In the movements and tones of the Princess was perceptible the stirring of spring; she had the air of relief and repose noticeable in young widows in the second period of their mourning. It is a delightful position. For the first time after the restraints of girlhood and the restraints of marriage, a woman enjoys the sweets of liberty and undisputed possession of herself; she is freed from contact with the coarser nature of man, and above all from the fear of maternity, the haunting terror of the young wife of the present day. In the case of the Princess Colette the natural development of uncontrollable grief into perfect peacefulness was emphasised by the paraphernalia of inconsolable widowhood with which she was still surrounded. It was not hypocrisy; but how could she give orders, without raising a smile on the servants’ faces, to remove the hat always waiting in the ante-room, the walking stick conspicuously handy, the place at table always laid for the absent husband; how could she say, ‘The Prince will not dine to-night’? But the mystic correspondence ‘with Herbert in heaven’ had begun to fall off, growing less frequent every day, till it ended in a calmly written journal which caused considerable, though unexpressed, amusement to Colette’s discerning friend.

The fact was that Madame Astier had a plan. The idea had sprung up in her practical little mind one Tuesday night at the Théâtre Français, when the Prince d’Athis had said to her confidentially in a low voice: ‘Oh, my dear Adelaide, what a chain to drag! I am bored to death.’ She at once planned to marry him to the Princess. It was a new game to play, crossing the old game, but not less subtle and fascinating. She had not now to hold forth upon the eternal nature of vows, or to hunt up in Joubert or other worthy philosophers such mottoes as the following, which the Princess had written out at the beginning of her wedding book: ‘A woman can be wife and widow with honour but once.’ She no longer went into raptures over the manly beauty of the young hero, whose portrait, full length and half length, profile and three quarters, in marble and on canvas, met you in every part of the house.

It was her system now to bring him gradually and dexterously down. ‘Do you not think, dear,’ she would say, ‘that these portraits of the Prince make his jaw too heavy? Of course I know the lower part of his face was rather pronounced, a little too massive.’ And so she administered a series of little poisonous stabs, with an indescribable skill and gentleness, drawing back when she went too far, and watching for Colette’s smile at some criticism a little sharper than the rest. Working in this way she at last brought Colette to admit that Herbert had always had a touch of the boor; his manners were scarcely up to his rank; he had not, for instance, the distinguished air of the Prince d’Athis, ‘whom we met a few Sundays ago on the steps of St. Philip’s. If you should fancy him, dear, he is looking for a wife.’ This last remark was thrown out as a jest; but presently Madame Astier recurred to it and put it more definitely. Well, why should the Princess not marry him? It would be most suitable; the Prince had a good name, a diplomatic position of some importance; the marriage would involve no alteration of the Princess’s coronet or title—a practical convenience not to be overlooked. ‘And, indeed, if I am to tell you the truth, dear, the Prince entertains towards you an affection which’... &c. &c.

The word ‘affection’ at first hurt the Princess’s feelings, but she soon grew used to hear it. They met the Prince d’Athis at church, then in great privacy at Madame Astier’s in the Rue de Beaune, and Colette soon admitted that he was the only man who might have induced her to abandon her widowhood. But then poor dear Herbert had loved her so devotedly—she had been his all.

‘Really,’ said Madame Astier with the quiet smile of a person who knows. Then followed allusions, hints, and all the devices by which one woman poisons the mind of another.

‘Why, my dear, there is no such thing in the world. A man of good breeding—a gentleman—will take care, for the sake of peace, not to give his wife pain or distress. But——’

‘Then you mean that Herbert——’

‘Was no better than the rest of them.’ The Princess, with an indignant protest, burst into tears; painless, passionless tears, such as ease a woman, and leave her as fresh as a lawn after a shower. But still she did not give way, to the great annoyance of Madame Astier, who had no conception of the real cause of her obduracy.

The truth was that frequent meetings to criticise the scheme of the mausoleum, much touching of hands and mingling of locks over the plans and sketches of cells and sepulchral figures, had created between Paul and Colette a fellow feeling which had gradually grown more and more tender, until one day Paul Astier detected in Colette’s eyes as she looked at him an expression that almost confessed her liking. There rose before him as a possibility the miraculous vision of Colette de Rosen bringing him her million as a marriage gift. That might be in a short time, after a preliminary trial of patience, a regularly conducted beleaguering of the fortress. In the first place it was most important to-betray no hint to ‘mamma,’ who, though very cunning and subtle, was likely to fail through excess of zeal, especially when the interests of her Paul were at stake. She would spoil all the chances in her eagerness to hasten the successful issue. So Paul concealed his plans from Madame Astier, in entire ignorance that she was running a countermine in the same line as his. He acted on his own account with great deliberation. The Princess was attracted by his youth and fashion, his brightness and his witty irony, from which he carefully took the venom. He knew that women, like children and the mob, and all impulsive and untutored beings, hate a tone of sarcasm, which puts them out, and which they perceive by instinct to be hostile to the dreams of enthusiasm and romance.

On this spring morning it was with feelings of more confidence than usual that young Astier reached the house. This was the first time that he had been asked to breakfast at the Rosen mansion; the reason alleged was a visit which they were to make together to the cemetery, in order to inspect the works on the spot. With an unexpressed understanding they had fixed on a Wednesday, the day when Madame Astier was ‘at home,’ so as not to have her as a third in the party. With this thought in his mind the young man, self-controlled as he was, let fall as he crossed the threshold a careless glance which took in the large courtyard and magnificent offices almost as if he were entering on the possession of them. His spirits fell as he passed through the ante-room, where the footmen and lacqueys in deep mourning were dozing on their seats. They seemed to be keeping a funeral vigil round the hat of the defunct, a magnificent grey hat, which proclaimed the arrival of spring as well as the determination with which his memory was kept up by the Princess. Paul was much annoyed by it; it was like meeting a rival. He did not realise the difficulty which prevented Colette from escaping the self-forged fetters of her custom. He was wondering angrily whether she would expect him to breakfast in company with him, when the footman who relieved him of his walking stick and hat informed him that the Princess would receive him in the small drawing-room. He was shown at once into the rotunda with its glass roof, a bower of exotic plants, and was completely reassured by the sight of a little table with places laid for two, the arrangement of which Madame de Rosen was herself superintending.

‘A fancy of mine,’ she said, pointing to the table, ‘when I saw how fine it was. It will be almost like the country.’

She had spent the night considering how she could avoid sitting down with this handsome young man in the presence of his knife and fork, and, not knowing what to say to the servants, had devised the plan of abandoning the situation and ordering breakfast, as a sudden whim, ‘in the conservatory.’

Altogether the ‘business’ breakfast promised well. The Romany blanc lay to keep cool in the rocky basin of the fountain, amidst ferns and water plants, and the sun shone on the pieces of spar and on the bright smooth green of the outspread leaves. The two young people sat opposite one another, their knees almost touching: he quite self-possessed, his light eyes cold and fiery; she all pink and white, her new growth of hair, like a delicate wavy plumage, showing without any artificial arrangement the shape of her little head. And while they talked on indifferent topics, both concealing their real thoughts, young Astier exulted each time that the silent servants opened the door of the deserted dining-room, when he saw in the distance the napkin of the departed, left for the first time cheerless and alone.

From the Vicomte de Freydet

To Mademoiselle Germaine de Freydet,

Clos Jallanges, near Mousseaux, Loir et Cher.

My dear Sister,—I am going to give you a precise account of the way I spend my time in Paris. I shall write every evening, and send you the budget twice a week, as long as I stay here.

Well, I arrived this morning, Monday, and took up my quarters as usual in my quiet little hotel in the Rue Servandoni, where the only sounds of the great city which reach me are the bells of Saint Sulpice, and the continual noise from a neighbouring forge, a sound of the rhythmical beating of iron, which I love because it reminds me of our village. I rushed off at once to my publisher. ‘Well, when do we come out?’

‘Your book? Why, it came out a week ago.’

Come out, indeed, and gone in too—gone into the depths of that grim establishment of Manivet’s, which never ceases to pant and to reek with the labour of giving birth to a new volume. This Monday, as it happened, they were just sending out a great novel by Herscher, called Satyra. The copies struck off—how many hundreds of thousands of them I don’t know—were lying in stacks and heaps right up to the very top of the establishment. You can fancy the preoccupation of the staff, and the lost bewildered look of worthy Manivet himself, when I mentioned my poor little volume of verse, and talked of my chances for the Boisseau prize. I asked for a few copies to leave with the members of the committee of award, and made my escape through streets—literally streets—of Satyra, piled up to the ceiling. When I got into my cab, I looked at my volume and turned over the pages. I was quite pleased with the solemn effect of the title, ‘God in Nature.’ The capitals are perhaps a trifle thin, when you come to look at them, not quite as black and impressive to the eye as they might be. But it does not matter. Your pretty name, ‘Germaine,’ in the dedication will bring us luck. I left a couple of copies at the Astiers’ in the Rue de Beaune. You know they no longer occupy their rooms at the Foreign Office. But Madame Astier has still her ‘Wednesdays.’ So of course I wait till Wednesday to hear what my old master thinks of the book; and off I went to the Institute.

There again I found them as busy as a steam factory. Really the industry of this big city is marvellous, especially to people like us, who spend all the year in the peace of the open country. Found Picheral—you remember Picheral, the polite gentleman in the secretary’s office, who got you such a good place three years ago, when I received my prize—well, I found Picheral and his clerks in the midst of a wild hubbub of voices, shouting out names and addresses from one desk to another, and surrounded on all sides by tickets of every kind, blue, yellow, and green, for the platform, for the outer circle, for the orchestra, Entrance A, Entrance B, &c. They were in the middle of sending out the invitations for the great annual meeting, which is to be honoured this year by the presence of a Royal Highness on his travels, the Grand Duke Leopold. ‘Very sorry, my lord’—Picheral always says ‘my lord,’ having learnt it, no doubt, from Chateaubriand—’ but I must ask you to wait.’ ‘Certainly, M. Picheral, certainly.’

Picheral is an amusing old gentleman, very courtly. He reminds me of Bonicar and our lessons in deportment in the covered gallery at grandmamma’s house at Jallanges. He is as touchy, too, when crossed, as the old dancing master used to be. I wish you had heard him talk to the Comte de Bretigny, the ex-minister, one of the grandees of the Académie, who came in, while I was waiting, to rectify a mistake about the number of his tallies. I must tell you that the tally attesting attendance is worth five shillings, the old crown-piece. There are forty Academicians, which makes two hundred shillings per meeting, to be divided among those present; so, you see, the fewer they are, the more money each gets. Payment is made once a month in crown-pieces, kept in stout paper bags, each with its little reckoning pinned on to it, like a washing bill. Bretigny had not his complete number of tallies; and it was the most amusing sight to see this man of enormous wealth, director of Heaven knows how many companies, come there in his carriage to claim his ten shillings. He only got five, which sum, after a long dispute, Picheral tossed to him with as little respect as to a porter. But the ‘deity’ pocketed them with inexpressible joy; there is nothing like money won by the sweat of your brow. For, my dear Germaine, you must not imagine that there is any idling in the Académie. Every year there are fresh bequests, new prizes instituted; that means more books to read, more reports to engross, to say nothing of the dictionary and the orations. ‘Leave your book at their houses, but do not go in,’ said Picheral, when he heard I was competing for the prize. ‘The extra work, which people are always putting on the members, makes them anything but gracious to a candidate.’

I certainly have not forgotten the way Ripault-Babin and Laniboire received me, when I called on them about my last candidature. Of course, when the candidate is a pretty woman, it is another story. Laniboire becomes jocose, and Ripault-Babin, still gallant in spite of his eighty years, offers the fair canvasser a lozenge, and says in his quavering voice, ‘Touch it with your lips, and I will finish it.’ So they told me in the secretary’s office, where the deities are discussed with a pleasing frankness. ‘You are in for the Boisseau prize. Let me see; you have for awarders two Dukes, three Mouldies, and two Players.’ Such, in the office, is the familiar classification of the Académie Française! ‘Duke’ is the name applied to all members of the nobility and episcopacy; Mouldies’ includes the professors and the learned men generally; while a ‘Player’ denotes a lawyer, dramatic author, journalist, or novelist.

After ascertaining the addresses of my Dukes, Mouldies, and Players, I gave one of my ‘author’s copies’ to the friendly M. Picheral, and, for form’s sake, left another for poor M. Loisillon, the Permanent Secretary, who is said to be all but dead. Then I set to work to distribute the remaining copies all over Paris. The weather was glorious. As I passed through the Bois de Boulogne on my way back from the house of Ripault-Babin (which reminded me of the lozenges), the place was sweet with may and violets. I almost fancied myself at home again on one of those first days of early spring when the air is fresh and the sun hot; and I was inclined to give up everything and come back to you at Jallanges. Dined on the boulevard alone and gloomy, and then spent the rest of my evening at the Comédie Française, where they were playing Desminières’ ‘Le Dernier Frontin.’ Desminières is one of the awarders of the Boisseau prize, so I shall tell no one but you how his verses bored me. The heat and gas gave me a headache. The actors played as if Louis XIV. had been listening; and while they spouted alexandrines, suggestive of the unrolling of a mummy’s bands, I was still haunted by the scent of the hawthorn at Jallanges, and repeated to myself the pretty lines of Du Bellay, a fellow-countryman, or a neighbour at least:

More than your marbles hard I love the tender slate,

Than Tiber more the Loire, and France than Rome,

Mine own dear hills than Palatinus’ state,

More than the salt sea breeze the fragrantair of home.

Tuesday.—Walked about the town all the morning, stopping in front of the booksellers’ shops to look for my book in the windows. Satyra, Satyra, Satyra! Satyra and nothing else to be seen everywhere, with a paper slip round it, ‘Just out.’ Here and there, but very seldom, there would be a poor miserable God in Nature tucked away out of sight. When no one was looking I put it on the top of the heap, well in view; but people did not stop. One man did, though, in the Boulevard des Italiens, a negro, a very intelligent-looking fellow. He turned over the pages for five minutes, and then went away without buying the book. I should have liked to present it to him.

Breakfasted in the corner of an English eating-house, and read the papers. Not a word about me, not even an advertisement. Manivet is so careless, very likely he has not so much as sent the orders, though he declared he had. Besides, there are so many new books. Paris is deluged with them. But for all that it is depressing to think that verses, which ran like fire through one’s fingers, which seemed, in the feverish delight of writing them, beautiful enough to fill the world with brightness, are more lost now that they are gone into circulation, than when they were but a confused murmuring in the brain of their author. It reminds one of a ball-dress. When it is tried on in the sympathetic family circle, it is expected to outshine and eclipse every dress in the room; but under the blaze of the gas it is lost in the crowd. Well, Herscher is a lucky fellow. He is read and understood. I met ladies carrying snugly under their arms the little yellow volume just issued. Alas, for us poor poets! It is all very well for us to rank ourselves above and beyond the crowd. It is for the crowd, after all, that we write. When Robinson Crusoe was on his desert island, cut off from all the world and without so much as the hope of seeing a sail on the horizon, would he have written verses, even if he had been a poetic genius? Thought about this a great deal as I tramped through the Champs Elysées, lost, like my book, in an unregarding stream.

I was coming back to my hotel, pretty glum, as you may imagine, when on the Quai d’Orsay, just in front of the grass-grown ruin of the Cour des Comptes, I knocked against a big fellow, strolling along in a brown study. ‘Hullo, Freydet!’ said he. ‘Hullo, Védrine!’ said I. You’ll remember my friend Védrine who, when he was working at Mousseaux, came with his sweet young wife to spend an afternoon at Clos-Jallanges. He is not a bit altered, except that he is a trifle grey at the temples. He held by the hand the fine boy with the beaming eyes, whom you used to admire. His head was erect, his movements slow and eloquent, his whole carriage that of a superior being. A little way behind was Madame Védrine pushing a perambulator, in which was a laughing little girl, born since their visit to Touraine.

‘That makes three for her, counting me,’ said Védrine, with a wave of his hand towards his wife; and the look of Madame when her eye rests on her husband really does express the tender satisfaction of motherhood; she is like a Flemish Madonna contemplating her Divine Child. Talked a long time, leaning against the parapet of the quay; it did me good to be with these honest folk. That is a man, anyhow, who cares nothing whatever for success, and the public, and the prizes! With his connections (he is cousin to Loisillon and to the Baron d’Huchenard), if he chose—if he just put a little water into his strong wine—he might have orders, and get the Biennial Prize, and be in the Institute in no time. But nothing tempts him, not even fame. ‘Fame,’ he said, ‘I have had a taste of it. I know what it is. When a man’s smoking, he sometimes gets his cigar by the wrong end. Well, that’s fame: just a cigar with the hot end and ash in your mouth.’

‘But, Védrine,’ said I, ‘if you work neither for fame nor for money—— yes, yes; I know you despise it; but, that being so, I say, why do you take so much trouble?’

‘For myself and my personal satisfaction. It’s the desire for creation and self-expression.’

Clearly here is a man who would have gone on with his work in the desert island. He is a true artist, ever in quest of a new type, and in the intervals of his labour endeavours by change of material and change of conditions to satisfy his craving for a fresh revelation. He has made pottery, enamels, mosaics, the fine mosaics so much admired in the guard-room at Mousscaux. When the thing is done, the difficulty overcome, he goes on to something else. At the present moment his great idea is to try painting; and the moment he has finished his warrior, a great bronze figure for the Rosen tomb, he intends, as he says, ‘to put himself to oil.’ His wife always gives her approval, and rides behind him on each of his hobbies. The right wife for an artist taciturn, admiring, saving the grown-up boy from all that might spoil his dream or catch his feet as he goes star-gazing along. She is the sort of woman dear Germaine, to make a man want to be married. If I knew another such, I should certainly bring her to Clos-Jallanges, and I am sure you would love her. But do not be alarmed. There are not many of them; and we shall go on to the end, living just by our two selves, as we do now.

Before we parted we fixed another meeting for Thursday, not at their house at Neuilly, but at the studio on the Quai d’Orsay, where the whole family spend the day together. This studio would seem to be the strangest place. It is in a corner of the old Cour des Comptes. He has got permission to do his work there, in the midst of wild vegetation and mouldering heaps of stone. As I went away I turned to watch them walking along the quay, father, mother, and children, all enveloped in the calm light of the setting sun, which made a halo round them like a Holy Family. Strung together a few lines on the subject in the evening at my hotel; but I am put out by having neighbours, and do not like to spout. I want my large study at Jallanges, with its three windows looking out oh the river and the sloping vineyards.

And now we come to Wednesday, the great day and the great event! I will tell you the story in full. I confess that I had been looking forward to my call on the Astiers with much trepidation, which increased to-day as I went up the broad moist steps of the staircase in the Rue de Beaune. What was I going to hear said about my book? Would my old master have had time to glance at it? His opinion means for me so very much. He inspires me still with the same awe as when I was in his class, and in his presence I shall always feel myself a schoolboy. His unerring and impartial judgment must be that of the awarders of the prize. So you may guess the tortures of impatience which I underwent in the master’s large study, which he gives up to his wife for her reception.

It’s sadly different from the room at the Foreign Office. The table at which he writes is pushed away into a recess behind a great screen covered in old tapestry, which also hides part of the bookshelves. Opposite, in the place of honour, is a portrait of Madame Astier in her young days, wonderfully like her son, and also like old Réhu, whose acquaintance I have just had the honour of making. The portrait has a somewhat depressing air of elegance, cold and polished, like the large uncarpeted room itself, with its sombre curtains and its outlook on a still more sombre courtyard. But in comes Madame Astier, and her friendly greeting brightens all the surroundings. What is there in the air of Paris which preserves the beauty of a woman’s face beyond the natural term, like a pastel under its glass? The delicate blonde with her keen eyes looked to me three years younger than when I saw her last. She began by asking after you, and how you were, dearest, showing great interest in our domestic life. Then suddenly she said: ‘But your book, let us talk about your book. How splendid! You kept me reading all night.’ And she showered upon me well-chosen words of praise, quoted two or three lines with great appropriateness, and assured me that my old master was delighted; he had begged her to tell me so, in case he should not be able to tear himself from his documents.

Red as you know I always am, I must have turned as scarlet as after a hunt dinner. But my joy soon passed away when I heard what the poor woman was led on into confiding to me about their embarrassments. They have lost money; then came Astier’s dismissal; now the master works night and day at his historical books, which take so long to construct and cost so much to produce, and then are not bought by the public. Then they have to help old Réhu, the grandfather, who has nothing but his fees for attendance at the Académie; and at his age, ninety-eight, you may imagine the care and indulgence necessary. Paul is a good son, hardworking, and on the road to success, but of course the initial expenses of his profession are tremendous. So Madame Astier conceals their narrow means from him as well as from her husband. Poor dear man! I heard his heavy even step overhead while his wife was stammering out, with trembling lips and hesitating, reluctant words, a request that if I could——

Ah, the adorable woman! I could have kissed the hem of her dress!

Now, my dear sister, you will understand the telegram you must have received a little while ago, and who the £400 were for that I asked for by return of post. I suppose you sent to Gobineau at once. The only reason I did not telegraph direct to him is that, as we ‘go shares’ in everything, our freaks of liberality ought, like the rest, to be common to both. But it is terrible, is it not, to think of the misery concealed under these brilliant and showy Parisian exteriors?

Five minutes after she had made these distressing disclosures people arrived and the room was full; Madame Astier was conversing with a complete self-possession and an appearance of happiness in voice and manner which made my flesh creep. Madame Loisillon was there, the wife of the Permanent Secretary. She would be much better employed in looking after her invalid than in boring society with the charms of their delightful suite, the most comfortable in the Institute, ‘with three rooms more than it had in Villemain’s time.’ She must have told us this ten times, in the pompous voice of an auctioneer, and in the hearing of a friend living uncomfortably in rooms lately used for a table d’hôte!

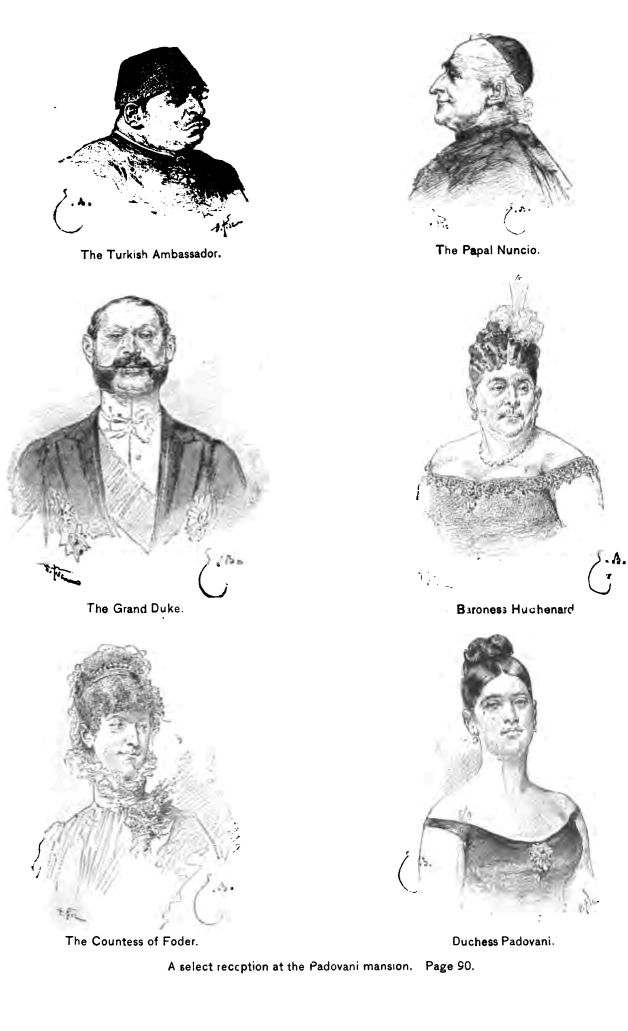

No fear of such bad taste in Madame Ancelin, a name often to be seen in the Society papers. A good fat round lady, with regular features and high complexion, piping out epigrams, which she picks up and carries round: a friendly creature, it must be allowed. She too had sat up all night reading me. I begin to think it is the regular phrase. She begged me to come to her house whenever I liked. It is one of the three recognised meeting-places of the Académie. Picheral would say that Madame Ancelin, mad on the theatre, welcomes more especially the ‘Players,’ Madame Astier the ‘Mouldies,’ while the Duchess Padovani monopolises the ‘Dukes,’ the aristocracy of the Institute. But really these three haunts of fame and intrigue communicate one with another, for on Wednesday in the Rue de Beaune I saw a whole procession of deities of every description. There was Danjou the writer of plays, Rousse, Boissier, Dumas, de Brétigny, Baron Huchenard of the Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and the Prince d’Athis of the Sciences Morales et Politiques. There is a fourth circle in process of formation, collected round Madame Eviza, a Jewess with full cheeks and long narrow eyes, who flirts with the whole Institute and sports its colours; she has green embroideries on the waistcoat of her spring costume, and a little bonnet trimmed with wings à la Mercury. She carries her flirtations a little too far. I heard her say to Danjou, whom she was asking to come and see her, ‘The attractions of Madame Ancelin’s house are for the palate, those of mine for the heart.’

‘I require both lodging and board,’ was the cold reply of Danjou. Danjou, I believe, covers the heart of a cynic under his hard impenetrable mask and his black stiff thatch, like a shepherd of Latium. Madame Eviza is a fine talker, and is mistress of considerable information; I heard her quoting to the old Baron Huchenard whole sentences from his ‘Cave Man,’ and discussing Shelley with a boyish magazine writer, neat and solemn, with a pointed chin resting on the top of a high collar.

When I was young it was the fashion to begin with verse-writing, whatever was to follow, whether prose, business, or the bar. Nowadays people begin with literary criticism, generally a study on Shelley. Madame Astier introduced me to this young gentleman, whose views carry weight in the literary world; but my moustaches and the colour of my skin, as brown as that of a sapper-and-miner, probably failed to please him. We spoke only a few words, while I watched the performance of the candidates and their wives or relatives, who had come to show themselves and to see how the ground lay. Ripault-Babin is very old, and Loisillon cannot last much longer; and around these seats, which must soon be vacant, rages a war of angry looks and poisoned words.

Dalzon the novelist, your favourite, was there; he has a kindly, open, intellectual face, as you would expect from his books. But you would have been sorry to see him cringing and sniggering before a nobody like Brétigny, who has never done anything, but occupies in the Academic the seat reserved for the man of the world, as in the country we keep a place for the poor man in our Twelfth Night festivities. And not only did he court Brétigny, but every Academician who came in. There he was, listening to old Rehu’s stories, laughing at Danjou’s smallest jokes with the ‘counterfeited glee’ with which at Louis-le-Grand we rewarded what Védrine used to call ‘usher’s wit.’ All this to bring his twelve votes of last year up to the required majority.

Old Jean Réhu looked in at his granddaughter’s for a few minutes, wonderfully fresh and erect, well buttoned up in a long frock coat. He has a little shrivelled face, looking as if it had been in the fire, and a short cottony beard, like moss on an old stone. His eyes are bright and his memory marvellous, but he is deaf, and this depresses him and drives him into long soliloquies about his interesting personal recollections, To-day he told us about the household of the Empress Joséphine at Malmaison; his ‘compatriote,’ he calls her, both being Creoles from Martinique. He described her, in her muslins and cashmere shawls, smelling of musk so strongly as to take one’s breath away, and surrounded with flowers from the colonies. Even in war time these flowers, by the gallantry of the enemy, were allowed to pass the lines of their fleet. He also talked of David’s studio, as it was under the Consulate, and did us the painter, rating and scolding his pupils with his mouth all awry and the remains of his dinner in his cheek. After each extract from the long roll of his experience, the patriarch shakes his head solemnly, gazes into space, and says in his firm tones, ‘That’s a thing that I have seen.’ It is his signature, as it were, put at the bottom of the picture to prove it genuine. I ought to say that, with the exception of Dalzon, who pretended to be drinking in his words, I was the only person in the room who attended to the old man’s tales. They seemed to me much more worth hearing than the stories of a certain Lavaux, a journalist, or librarian, or something—a dreadful retailer of gossip, whatever else he may be. The moment he came in there was a general cry, ‘Ah, here’s Lavaux!’ and a circle was formed round him at once, all laughing and enjoying themselves. Even the frowning ‘deities’ revel in his anecdotes. He has a smooth-shaven, quasi-clerical face and goggle eyes. He prefaces all his tales and witticisms with such remarks as ‘I was saying to De Broglie,’ or ‘Dumas told me the other day,’ or ‘I have it from the Duchess herself,’ backing himself up with the biggest names and drawing his instances from all quarters. He is a pet of the ladies, whom he posts up in all the intrigues of the Académie and the Foreign Office, the world of letters and the world of fashion. He is very intimate with Danjou, and a constant companion of the Prince d’Athis, with whom he came in. Dalion and the young critic of Shelley he patronises; and indeed he exercises a power and authority quite inexplicable to me.

In the medley of stories which he produced from his inexhaustible chops—most of them were riddles to a simple rustic like myself—one only struck me as amusing. It was the mishap which occurred to a young Count Adriani, of the Papal Guard. He was going through Paris, in attendance upon a reverend personage, to take a cardinal’s hat and cap to some one or other, and the story is that he left the insignia at the house of some fair lady whom he met with as he left the train, and of whom he knew neither the name nor the address, being, poor young man! a stranger in Paris. So he had to write off to the Papal Court for new specimens of the ecclesiastical headgear to replace the first, which the lady must find entirely superfluous. The best part of the story is that the little Count Adriani is the Nuncio’s own nephew, and that at the Duchess’s last party—she is called ‘the Duchess’ in Academic circles just as she is at Mousseaux—he told his adventure quite naively in his broken French. Lavaux imitates it wonderfully.