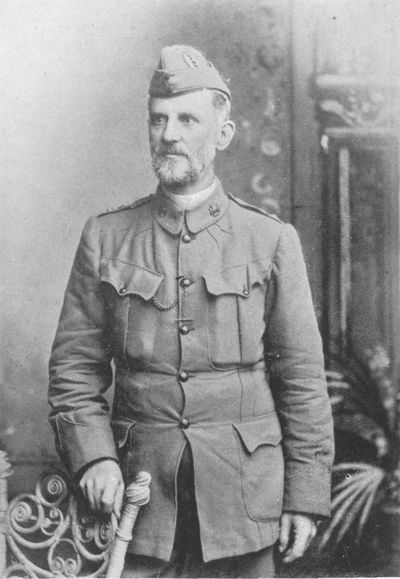

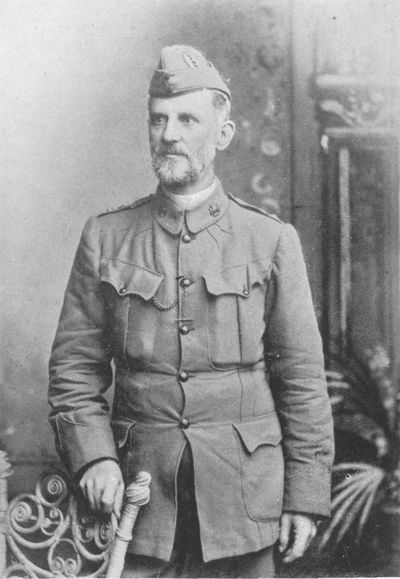

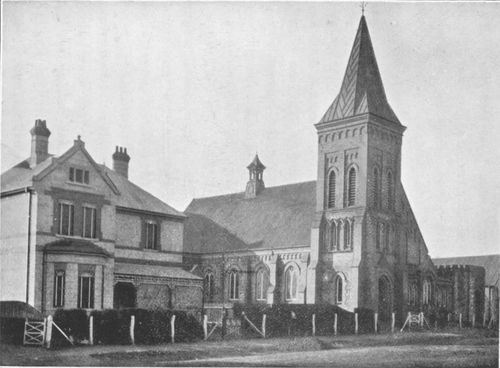

From a photograph by Deale, Blomfontein

Rev. E. P. LOWRY.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: With the Guards' Brigade from Bloemfontein to Koomati Poort and Back

Author: Edward P. Lowry

Release Date: April 22, 2008 [eBook #25135]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH THE GUARDS' BRIGADE FROM BLOEMFONTEIN TO KOOMATI POORT AND BACK***

Transcriber's Note:

Page 122: "After the treasure ship Hermione had thus been secured off Cadiz by the Actæan and the Favorite" should probably be "After the treasure ship Hermione had thus been secured off Cadiz by the Active and the Favorite".

From a photograph by Deale, Blomfontein

Rev. E. P. LOWRY.

FROM BLOEMFONTEIN

TO KOOMATI POORT AND BACK

BY THE

REV. E. P. LOWRY

SENIOR WESLEYAN CHAPLAIN WITH THE SOUTH AFRICAN FIELD FORCE

London

HORACE MARSHALL & SON

TEMPLE HOUSE, TEMPLE AVENUE, E.C.

1902

TO

THE OFFICERS,

NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS, AND MEN

OF THE GUARDS' BRIGADE

THIS IMPERFECT RECORD OF THEIR HEROIC DARING, AND OF

THEIR YET MORE HEROIC ENDURANCE IS

RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

IN TOKEN OF SINCEREST ADMIRATION, AND IN GRATEFUL

APPRECIATION OF NUMBERLESS COURTESIES RECEIVED

BY ONE OF THEIR FELLOW TRAVELLERS AND

CHAPLAINS THROUGHOUT THE BOER

WAR OF 1899-1902

The story of my long tramp with the Guards' Brigade was in part told through a series of letters that appeared in The Methodist Recorder, The Methodist Times, and other papers. The first portion of that series was republished in "Chaplains in Khaki," as also extensive selections in "From Aldershot to Pretoria." In this volume, therefore, to avoid needless repetition, the story begins with our triumphal occupation of Bloemfontein, and is continued till after the time of the breaking-up of the Guards' Brigade.

No one will expect from a chaplain a technical and critical account of the complicated military operations he witnessed at the seat of war. For that he has no qualifications. Nor, on the other hand, would it be quite satisfactory if he wrote only of what the chaplains and other Christian workers were themselves privileged to do in connection with the war. That would necessitate great sameness, if not great tameness. These pages are rather intended to set forth the many-sided life of our soldiers on active service, their privations and perils, their failings and their heroisms, their rare endurance, and in some cases their unfeigned piety; that all may see what manner of men they were who in so many instances laid down their lives in the defence of the empire; and amid what stupendous difficulties they endeavoured to do their duty.

(p. viii) We owe it to the fact that these men have volunteered in such numbers for military service that Britain alone of all European nations has thus far escaped the curse of the conscription. In that sense, therefore, they are the saviours and substitutes of the entire manhood of our nation. If they had not consented of their own accord to step into the breach, every able Englishman now at his desk, behind his counter, or toiling at his bench, must have run the risk of having had so to do. We owe to these men more than we have ever realised. It is but right, therefore, that more than ever they should henceforth live in an atmosphere of grateful kindliness, of Christian sympathy and effort.

"God bless you, Tommy Atkins,

Here's your country's love to you!"

My authorities for the statements made in the introductory chapter are Fitzpatrick's "Pretoria from Within," and Martineau's "Life of Sir Bartle Frere." For the verifying or correcting of my own facts and figures, given later on, I have consulted Conan Doyle's "The Great Boer War," Stott's "The Invasion of Natal," and almost all other available literature relating to the subject.

Edward P. Lowry.

Pretoria, March 1902.

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER

PAGE

The Ultimatum and what led to it 1

Two Notable Dreamers—A Bankrupt Republic—The Man who Schemed as well as Dreamed—The Gold Plague—Hated Johannesburg—Boer preparations for War—Coming events cast their shadows before—The Ultimatum—The Rallying of the Clans—The Rousing of the Colonies.

CHAPTER I

On the way to Bloemfontein, and in it! 14

A capital little Capital—Famished Men and Famine Prices—Republican Commandeering—A Touching Story—The Price of Milk.

CHAPTER II

A Long Halt 24

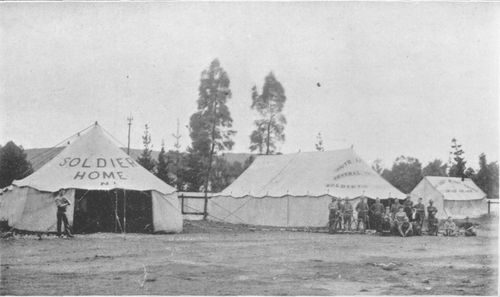

Refits—Remounts—Regimental Pets—Civilian Hospitality and Soldiers' Homes—Soldiers' Christian Association Work—Rudyard Kipling's Mistake—All Fools' Day—Eastertide in Bloemfontein—The Epidemic and the Hospitals—All hands and houses to the rescue—A sad sample of Enteric—Church of England Chaplains at work.

CHAPTER III

Through Worlds Unknown and from Worlds Unknown 45

A Pleasure Jaunt—Onwards, but Whither!—That Pom-Pom again—A Problem not quite solved—A Touching Sight—Rifle Firing and Firing Farms—Boer Treachery and the White Flag—The Pet Lamb still lives and learns—Right about face—From Worlds Unknown—The Bushmen and their Australian Chaplains.

Quick March to the Transvaal 57

A Comedy—A Tragedy—A Wide Front and a Resistless Force—Brandfort—"Stop the War" Slanders—A Prisoner who tried to be a Poet—Militant Dutch Reformed Predikants—Our Australian Chaplain's pastoral experiences—The Welsh Chaplain.

CHAPTER V

To the Valsch River and the Vaal 70

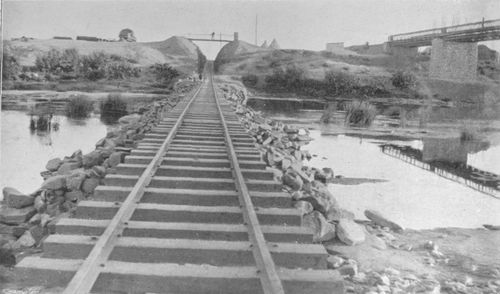

The Sand River Convention—Railway Wrecking and Repairing—The Tale, and Tails, of a Singed Overcoat—Lord Roberts as Hospital Visitor—President Steyn's Sjambok—A Sunday at last that was also a Sabbath—Military Police on the March—A General's glowing eulogy of the Guards—Good News by the way—Over the Vaal at last.

CHAPTER VI

A Chapter about Chaplains 88

A Chaplain who found the Base became the Front—Pathetic Scenes in Hospital—A Battlefield Scene no less Pathetic—Look on this Picture, and on that—A third-class Chaplain who proved a first-rate Chaplain—Running in the Wrong Man—A Wainman who proved a real Waggoner—Three bedfellows in a barn—A fourth-class Chaplain that was also a first-rate Chaplain—A Parson Prisoner in the hands of the Boers—Caring for the Wounded—How the Chaplain's own Tent was bullet-riddled—A Sample Set of Sunday Services.

CHAPTER VII

The Helpful Work of the Officiating Clergy 103

At Cape Town and Wynberg—Saved from Drowning to sink in Hospital—A Pleasant Surprise—The Soldiers' Reception Committee—The other way about—Our near kinship to the Boers—More good Work on our right Flank.

CHAPTER VIII

Getting to the Golden City 113

An elaborate night toilet—Capturing Clapham Junction—Dear diet and dangerous—No Wages but the Sjambok—The Gold Mines—The Soldiers' Share—The Golden City—Astonishing the Natives.

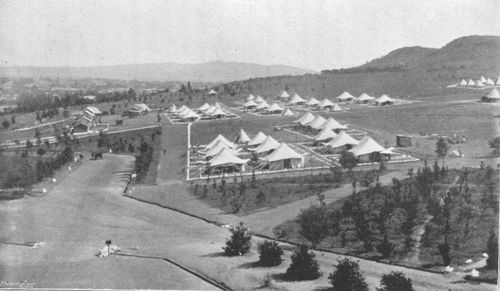

Pretoria—the City of Roses 127

Whit-Monday and Wet Tuesday—"Light after Dark"—Why the Surrender?—Taking Possession—"Resurgam"—A Striking Incident—No Canteens and no Crime.

CHAPTER X

Pretorian Incidents and Impressions 142

The State's Model School—Rev. Adrian Hoffmeyer—The Waterfall Prisoners—A Soldier's Hymn—A big Supper Party—The Soldiers' Home—Mr and Mrs Osborn Howe—A Letter from Lord Kitchener—Also from Lord Roberts—A Song in praise of De Wet—Cordua and his Conspiracy—Hospital Work in Pretoria—The Wear and Tear of War—The Nursing Sisters—A Surprise Packet—Soldierly Gratitude—The Ladysmith Lyre.

CHAPTER XI

From Pretoria to Belfast 169

The Boer way of saying "Bosh"—News from a far Country—Further fighting—Touch not, taste not, handle not—More Treachery and still more—The root of the matter—A Tight Fit—Obstructives on the Rail—Middleburg and the Doppers—August Bank Holiday—Blowing up Trains—A peculiar Mothers' Meeting—Aggressive Ladies—A Dutch Deacon's Testimony—A German Officer's Testimony.

CHAPTER XII

Through Helvetia 190

The Fighting near Belfast—Feeding under Fire—A German Doctor's Confession—Friends in need are Friends indeed—The Invisible Sniper's Triumph—"He sets the mournful Prisoners free"—More Boer Slimness—A Boer Hospital—Foreign Mercenaries—A wounded Australian—Hotel Life on the Trek—A Sheep-pen of a Prison—Pretty Scenery and Superb.

CHAPTER XIII

War's Wanton Waste 210

A Surrendered Boer General—Two Unworthy Predikants—Two Notable Advocates of Clemency—Mines without Men, and Men (p. xii) without Meat—Much Fat in the Fire—More Fat and Mightier Flames—A Welcome Lift by the Way—"Rags and Tatters, get ye gone!"—Destruction and still more Destruction—At Koomati Poort—Two Notable Fugitives—The Propaganda of the Africander Bond—Ex-President Steyn—Paul Botha's opinion of this Ex-President.

CHAPTER XIV

From Portuguese Africa to Pretoria 231

Staggering Humanity—Food for Flames—A Crocodile in the Koomati—A Hippopotamus in the Koomati—A Via Dolorosa—Over the Line—Westward Ho!—Ruined Farms and Ruined Firms—Farewell to the Guards' Brigade!

CHAPTER XV

A War of Ceaseless Surprises 245

Exhaustlessness of Boer resources—The Peculiarity of Boer Tactics—The Surprisers Surprised—Train Wrecking—The Refugee Camps—The Grit of the Guards—The Irregulars—The Testimony of the Cemetery—Death and Life in Pretoria.

CHAPTER XVI

Pretoria and the Royal Family 261

Suzerainty turned to Sovereignty—Prince Christian Victor—A Royal Funeral—A Touching Story—The Death of the Queen—The King's Coronation.

THE ULTIMATUM AND WHAT LED TO IT

When the late Emperor of the French was informed, on the eve of the Franco-German War, that not so much as a gaiter button would be found wanting if hostilities were at once commenced, soon all France found itself, with him, fatally deceived. But when the Transvaal Burghers boasted that they were "ready to give the British such a licking as they had never had before," it proved no idle vaunting. Whether the average Boer understood the real purpose for which he was called to arms seems doubtful; but his leaders made no secret of their intention to drive the hated "Roineks" into the sea, and to claim, as the notorious "Bond" frankly put it, "all South Africa for the Africanders." The Rev. Adrian Hoffmeyer of the Dutch Reformed Church freely admits that the watchword of the Western Boers was "Tafelburg toc," that is, "To Table Mountain"; and that their commandant said to him, "We will not rest till our flag floats there."

Similarly on the eastern side it was their confident boast that presently they would be "eating fish and (p. 002) drinking coffee at sea-side Durban." There would thus be one flag floating over all South Africa; and that flag not the Union Jack but its supplanter.

Two notable Dreamers.Now the Dutch have undoubtedly as absolute a right to dream dreams of wide dominion as we ourselves have; and this particular dream had no less undeniably been the chief delight of some among them for more than a decade twice told.

Even President Brand, of the Orange Free State, referring to Lord Carnarvon's pet idea of a federated South Africa, said: "His great scheme is a united South Africa under the British Flag. He dreams of it and so do I; but under the flag of South Africa." Much in the same strain President Burgers, of the Transvaal Republic, when addressing a meeting of his countrymen in Holland, said: "In that far-off country the inhabitants dream of a future in which the people of Holland will recover their former greatness." He was convinced that within half a century there would be in South Africa a population of eight millions; all speaking the Dutch language; a second Holland, as energetic and liberty-loving as the first; but greater in extent, and greater in power.

A Bankrupt Republic.Nevertheless, in this far-seeing President's day, the Transvaal, after fourteen years of doubtful independence, reached in 1877 its lowest depths of financial and political impotency. Its valiant burghers were vanquished in one serious conflict with the natives; and, emboldened thereby, the (p. 003) Zulus were audaciously threatening to eat them up, when Shepstone appeared upon the scene. "I thank my father Shepstone for his restraining message," said Cetewayo. "The Dutch have tired me out; and I intended to fight with them once, only once, and to drive them over the Vaal." The jails were thrown open because food was no longer obtainable for the prisoners. The State officials, including the President, knew not where to secure their stipends, and were hopelessly at variance among themselves. The Transvaal one-pound notes were selling for a single shilling, and the State treasury contained only twelve shillings and sixpence wherewith to pay the interest on a comparatively heavy State debt, besides almost innumerable other claims.

No wonder, therefore, that Burgers, in disgust, declared he would sooner be a policeman under a strong government. "Matters are as bad as they ever can be," said he; "they cannot be worse!" Hence its annexation, in 1877, by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, without the assistance of a solitary soldier, but with the eager assent of thousands of the burghers, bade fair to prove the salvation of the Transvaal, and probably would have done, had the easily-to-be-obtained consent of the Volksraad been at once sought, and Lord Carnarvon's promise of speedy South African Federation, together with a generous measure of local self-government, been promptly redeemed. But European complications, with serious troubles on the Indian frontier, caused interminable delay in the maturing of this scheme; and as the disappointed Boers grew restive, a "Hold your Jaw" Act was passed, making it a penal (p. 004) offence for any Transvaaler even to discuss such questions. In our simplicity we sit upon the safety valve and then wonder why the boiler bursts. To the "Hold your Jaw" policy the Boer reply was an appeal to arms; and at Majuba in the spring of 1881 their rifles said what their jaws were forbidden to say. Majuba was indeed a mere skirmish, an affair of outposts; but Magersfontein and Spion Kop are the legitimate sons of Majuba.

The man who Schemed as well as Dreamed.Napoleon, with possibly a veiled reference to himself, once said to the French people, "You have the men, but where is The Man?" The Boers in the day of their uprising against British rule found "The Man" in Paul Stephanus Kruger. To all South Africa a veritable "man of Destiny" has he proved to be; and for eighteen successive years, as their honoured President he has ruled his people with an absoluteness no European potentate could possibly approach. By birth a British subject, and for a brief while after the annexation a paid official of the British Government, he yet seems all his life to have been a consistent hater of all things British. When only ten years old, a tattered, bare-legged, unlettered lad, he joined "The great Trek" which in 1837 sought on the dangerous and dreary veldt beyond the Vaal a refuge from British rule. He it was who, surviving the terrors of those tragic times and trained in that stern school, became like Brand and Burgers a dreamer of dreams. He lived to baffle by his superior (p. 005) shrewdness, or slimness, all the arts of English diplomacy. In his later years this President manifestly deemed himself chosen of Heaven to make an end of British rule from the Zambesi to the sea. "The Transvaal shall never be shut up in a kraal," said he. A Sovereign International State he declared it was, or should be, with free access to the ocean; and how astonishingly near he came to the accomplishment of these bold aims we now know to our exceeding cost. Nevertheless, to this persistent dreamer of dreams the two South African Republics owe their extinction; while the British Empire owes to him more than to any other living man its fast approaching Federation.

With surprising secrecy and success the Transvaal officials prepared for the inevitable conflict which the attempted fulfilment of such bold dreams involved, and in that preparation were rendered essential aid, first by the discovery, not far from Pretoria, of the richest goldfield in the whole world, which soon provided them with the necessary means; and next by the Jameson Raid, which provided them with the necessary excuse.

To Steevens, the lamented correspondent of The Daily Mail, a Dopper editor and predikant said, "I do not think the Transvaal Government has been wise, and I told them they made a great mistake when they let people come in to the mines. This gold will ruin you; to remain independent you must remain poor"! Perhaps so! but the modern world is not built that way. No trekkers nowadays may take possession (p. 006) of half a continent, forbid all others to come in, and right round the frontier post up notices "Trespassers will be prosecuted." Even Robinson Crusoe had not long landed on his desolate isle when he was startled by the sight of a strange footprint on the seashore sand. Welcome or unwelcome, somebody else had come! Crusoe and his man Friday might set up no exclusive rights in a heritage that for a brief while seemed all their own. The Boer with his Kaffir bondsman has been compelled to learn the same distasteful lesson. The wealth of the Witwaters Rand was for those who could win it; and for that stupendous task the Boer had neither the necessary aptitude nor the necessary capital. It was not, therefore, for him to echo the cry of Edie Ochiltree when he found hid treasure amid the ruins of St Roth's Abbey—"Nae halvers and quarters,—hale o' mine ain and nane o' my neighbours." The bankrupt Boer had to let his enterprising neighbour in to do the digging, or get no gold at all.

Hated Johannesberg.Nevertheless, the upspringing as by magic of the great city of Johannesberg in the midst of the dreary veldt filled Kruger's soul with loathing. When once asked to permit prospecting for minerals around Pretoria, he replied, "Look at Johannesberg! We have enough gold and gold seekers in the country already!" The presence of this ever-growing multitude was felt to be a perpetual menace to Dutch, and more especially to Dopper supremacy. So, in his frankly confessed detestation of them, their Dopper President for five years at a stretch (p. 007) never once came near them, and when at last he ventured to halt within twenty miles of their great city it was thus he commenced his address to the crowd at Krugersdorp:—"Burghers, friends, thieves, murderers, newcomers, and others." The reek of the Rand was evidently even then in his nostrils; and the mediæval saint that could smell a heretic nine miles off was clearly akin to Kruger. Unfortunately for him the "newcomers" outnumbered the old by five to one, and were a bewilderingly mixed assortment, representing almost every nationality under the whole heaven. In what had suddenly become the chief city of the Transvaal, with a white population of over 50,000, only seven per cent. were Dutch, and sixty-five per cent. were British. These aliens from many lands paid nearly nine-tenths of the taxes, yet were persistently denied all voice alike in national and municipal affairs. "Rights!" exclaimed the angry President when appealed to for redress, "Rights! They shall win them only over my dead body!" At whatever cost he was stubbornly resolved that as long as he lived the tail should still wag the dog instead of the dog the tail; and that a continually dwindling minority of simple farmer folk should rule an ever-growing majority of enterprising city men. Though the political equality of all white inhabitants was the underlying condition on which self-government was restored to the Transvaal, what the Doppers had won by bullets they would run no risk of losing through the ballot box, and so one measure of exclusion after another rapidly became law. When reminded (p. 008) that in other countries Outlanders were welcomed and soon given the franchise, the shrewd old President replied, "Yes! but in other countries the newcomers do not outswamp the old burghers." The whole grievance of the Boers is neatly summed up in that single sentence; and so far it proves them well entitled to our respectful pity.

It was, however, mere fatalism resisting fate when to a deputation of complaining Outlanders Kruger said "Cease holding public meetings! Go back and tell your people I will never give them anything!" Similarly when in 1894 35,000 adult male Outlanders humbly petitioned that they might be granted some small representation in the councils of the Republic, which would have made loyal burghers of them all, the short-sighted President contended that he might just as well haul down the Transvaal flag at once. There was a strong Dopper conviction that to grant the franchise on any terms to this alien crowd would speedily degrade the Transvaal into a mere Johannesberg Republic; and they would sooner face any fate than that; so the Raad, with shouts of derision, rejected the Outlanders' petition as a saucy request to commit political suicide. They felt no inclining that way! Nevertheless one of their number ventured to say, "Now our country is gone. Nothing can settle this but fighting!" And that man was a prophet.

Boer preparations for War.For that fighting the President and his Hollander advisers began to prepare with a timeliness and thoroughness we can but admire, however much in due time we were made to smart thereby. Through the suicide of a certain State (p. 009) official it became known that in 1894—long therefore before the Raid—no less than £500,000 of Transvaal money had been sent to Europe for secret uses. Those secret uses, however, revealed themselves to us in due time at Magersfontein and Colenso. The Portuguese customs entries at Delagoa Bay will certify that from 1896 to 1898 at least 200,000 rifles passed through that port to the Transvaal. It was an unexampled reserve for states so small. The artillery, too, these peace-loving Boers laid up in store against the time to come, not only exceeded in quantity, but also outranged, all that British South Africa at that time possessed. Their theology might be slightly out-of-date, but in these more material things the Boers were distinctly up-to-date. For many a week after the war began both the largest and the smallest shells that went curving across our battlefields were theirs; while many of our guns were mere popguns firing smoky powder, and almost as useless as catapults. It was not a new Raid these costly weapons were purchased to repel; neither men nor nations employ sledge-hammers to drive home tinned-tacks. It was a mighty Empire they were intended to assail; and a mighty Republic they were intended to create.

When the fateful hour arrived for the hurling of the Ultimatum, in very deed "not a gaiter button" was found wanting on their side; and every fighting man was well within reach of his appointed post. Fierce-looking farmers from the remotest veldt, and sleek urban Hollanders, German artillerists, French generals, Irish-Americans, Colonial rebels, all were ready. The horse (p. 010) and his rider, prodigious supplies of food stuffs, and every conceivable variety of warlike stores, were planted at sundry strategic points along the Natal and Cape Colony frontiers. War then waited on a word and that word was soon spoken!

Coming events cast their shadows before.As early as September 18th, 1899, the Transvaal sent an unbending and defiant message to the British Government. On September 21st the Orange Free State, after forty years of closest friendship with England, officially resolved to cast in her lot with the Transvaal against England. On September 29th through railway communication between Natal and the Transvaal was stopped by order of the Transvaal Government. On September 30th twenty-six military trains left Pretoria and Johannesberg for the Natal border; and that same day saw 16,000 Boers thus early massed near Majuba Hill. Yet at that very time the British forces in South Africa were absolutely and absurdly inadequate not merely for defiance but even for defence. On October 3rd, a full week before the delivery of the Ultimatum, the Transvaal mail train to the Cape was stopped at the Transvaal frontier, and the English gold it carried, valued at £500,000, was seized by the Transvaal Government. Whether that capture be regarded merely as a premature act of war or as highway robbery, it leaves no room for doubt as to which side in this quarrel is the aggressor; and when at last the challenge came, even chaplains could with a clear conscience, though by no means with a light heart, set out for the seat of war.

(p. 011) The Ultimatum.Surely never since the world began was such an Ultimatum presented to one of the greatest Powers on earth by what were supposed to be two of the weakest. At the very time that armed and eager burghers were thus massing threateningly on our frontiers, the Queen it will be remembered was haughtily commanded to withdraw from those frontiers the pitifully few troops then guarding them; to recall, in the sight of all Europe, every soldier that in the course of the previous twelvemonth had been sent to our South African Colonies; and solemnly to pledge herself, at Boer bidding, that those then on the sea should not be suffered to set foot on African soil. Moreover, so urgent was this audacious demand that Pretoria allowed London only forty-eight hours in which to decide what should be its irrevocable doom, to lay aside the pride of empire, or pay the price of it in blood.

Superb in its audacity was that demand: and, if war was indeed fated to come, this daring challenge was for England as serviceable a deed as unwitting foemen ever wrought.

The rallying of the Clans.It put a sudden end for a season to all controversy. It rallied in defence of our Imperial heritage almost every class, and every creed. It thrilled us all, like the blast of the warrior horn of Roderick Dhu, which transformed the very heather of the Highlands into fighting men. As the soldiers' laureate puts it "Duke's son and cook's son," with rival haste responded to the martial call. To serve (p. 012) their assailed and sorrowing Queen, royal court and rural cottage gave freely of their best. It intensified the patriotism of us all; and probably never, since the days of the Armada, had the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland found itself so essentially united.

The rousing of the Colonies.The effect of the Ultimatum throughout the length and breadth of Greater Britain was no less remarkable than its first results at home. Not only the two Colonies that, alas, were soon to be overrun by hostile hordes, and mercilessly looted, but also those farthest removed from the fray, instantly took fire, and burned with imperialistic zeal that stinted neither men nor means.

"A varied host, from kindred realms they come,

Brethren in arms, but rivals in renown."

The declaration of war united the ends of the earth in a common enthusiasm, and sent a strange throb of brotherhood right round the globe. The whole empire at last awoke to a sense of its essential oneness. Australians and Canadians, men from Burma, from India and Ceylon, speedily joined hands on the far distant veldt in defence of what they proudly felt to be their heritage as well as ours. Their presence in the very forefront of the fray betokened the advent of a new era. Nobler looking men, or men of a nobler spirit, were never brought together at the unfurling of any banner. They were the outcome of competitions strangely keen and close. Sydney for instance called for five hundred volunteers; but within a few days three thousand five hundred valiant men were clamouring for acceptance. So was it in (p. 013) Montreal. So it was everywhere. Often too at no slight financial sacrifice was the post of peril sought. As a type of many more, I was told of an Australian doctor who paid a substitute £300 to carry on his practice, while he as a private joined the fighting ranks and faced cheerily the manifold privations of the hungry veldt. Rich is the empire that owns such sons; and myriads of them in the hour of impending conflict were ready to say—

"War? We would rather peace! But, Mother, if fight we must,

There are none of your sons on whom you can lean with a surer trust.

Bone of your bone are we; and in death would be dust of your dust!"

It was the Ultimatum that thus linked to each other and to us those loyal hearts that longed to keep the empire whole; and thus President Kruger in his blindness became Greater Britain's boundless benefactor.[Back to Contents]

ON THE WAY TO BLOEMFONTEIN, AND IN IT

"For old times' sake

Don't let enmity live;

For old times' sake

Say you will forget and forgive.

Life is too short for quarrel;

Hearts are too precious to break;

Shake hands and let us be friends

For old times' sake!"

So gaily sang the Scots Guards as, in hope of speedy triumph and return, we left Southampton for Kruger's Land on the afternoon of October 21st, 1899.

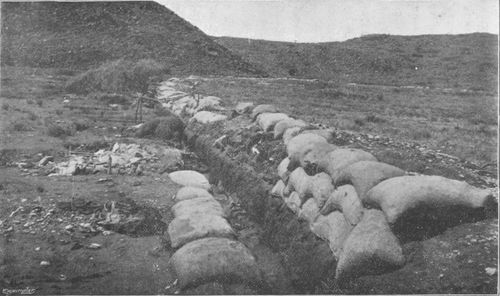

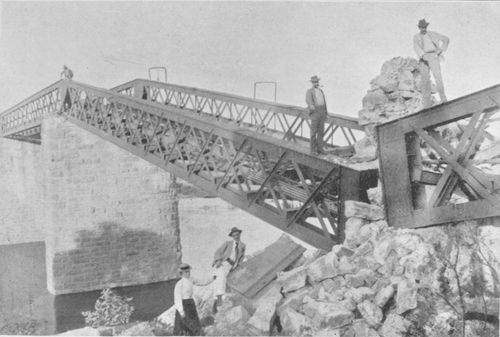

From a photograph by Mr Westerman

A Magersfontein Boer Trench.

Our last evening in England brought us the welcome tidings that on that day, the Boers who had thus early invaded Natal with a view to annexing it, had been badly beaten at Talana Hill. That seemed a good beginning; and it sent us to sea with lightsome hearts; nor was it till long after we landed in South Africa that we learned what had really taken place during our cheerful voyage;—that on the very day we embarked, the battle of Elandslaagte had been won by our hard-pressed comrades, but at a cost of 260 casualties; and that the very next day—The Nubia's first Sunday at sea—Dundee with all its stores had perforce been abandoned by 4000 of our retreating troops, for whose relief, two days later, Tinta Inyoni was fought by General French; that on Oct. 29th while we were (p. 015) spending a tranquil Sunday in St Vincent's harbour there commenced the struggle that culminated in the Nicholson's Nek disaster; and that on Nov. 13th, while we were awaiting orders in Table Bay, the capture of our armoured train at Chieveley took place. Clearly it was blissful ignorance that begat our hopes of brief absence from home, and of the easy vanquishing of our hardy foes!

Two days later I reached the Orange River; and, on the courteous suggestion of Lord Methuen, was attached to the mess of the 3rd Grenadier Guards, as was also my "guide, philosopher and friend" the Rev. T. F. Falkner our Anglican chaplain. Here I left my invaluable helper, Army Scripture Reader Pearce; while, with the Guards' Brigade now made complete by the arrival of the 1st and 2nd Coldstream battalions, I pushed forward to be present at the four battles which followed in startlingly swift succession, and which I have already with sufficient fulness described in "Chaplains in Khaki," viz. Belmont on Nov. 23rd, Graspan on Nov. 25th, Modder River on Nov. 28th, and the Magersfontein defeat on Dec. 11th, for which, however, the next Amajuba Day—Feb. 27th, 1900—brought us ample compensation in the surrender of Cronje and his 4000 veterans, with the ever memorable sequel to that surrender, the occupation of Bloemfontein by the British forces.

A capital little Capital.It would probably be difficult to find anywhere under the sun a more prosperous and promising little city, or one better governed than Bloemfontein, which the Guards entered on the afternoon of Tuesday, March 13th, 1900. There is (p. 016) not a scrap of cultivated land anywhere around it. It is very literally a child of the veldt; and still clings strangely to its nursing mother. Indeed the veldt is not only round about it on every side, but even asserts its presence in many an unfinished street. You are still on the veldt in the midst of the city; and the characteristic kopje is in full view here, there, and everywhere. On one side of the city is the old fort built by the British more than fifty years ago, and soon after vacated by them, but it is erected of course on a kopje, on one slope of which, part of the city now stands. On the opposite side of the town is a new fort; but that also crowns a kopje. This metropolis of what was then the Orange Free State, thus intensely African in its situation and surroundings, was nevertheless an every way worthy centre of a worthy State.

Many of its public buildings are notably fine, as for instance the Government Offices over which it was my memorable privilege to see the Union Jack unceremoniously hoisted; and the Parliament Hall, on the opposite side of the same road, erected some twelve years ago at a cost of £80,000. The Grey College, which accommodates a hundred boy boarders, is an edifice of which almost any city would be proud; and "The Volk's Hospital," that is "The People's Hospital," is also an altogether admirable institution. From the commencement of the war this was used for the exclusive benefit of sick or wounded Boers and of captured Britishers who were in the same sore plight. Among these I found many English officers, who all bore witness to the kind (p. 017) and skilful treatment they had uniformly received from the hospital authorities; but when the Boer forces hurried away from Bloemfontein they were compelled to leave their sick and wounded behind; with the result that as at Jacobsdal, the English patients at once ceased to be prisoners, while the Boer patients at once became prisoners. So do the wheels of war and fortune go whirling round!

With a white population of under ten thousand all told, a large proportion is of British descent; and presently a positively surprising number of Union Jacks sprang forth from their hiding-places and fluttered merrily all over the town. Everybody was thankful that no bombardment had taken place; but many even of the British residents regarded with sincere regret the final extinction of the independence of this once self-governed and well-governed Republic.

Famished men and famine prices.The story has now everywhere been told of the soldier lad who, when he caught sight of his first swarm of locusts, wonderingly exclaimed as he noted their peculiar colour, "I'm blest if the butterflies out here haven't put on khaki." Bloemfontein very soon did the same. Khaki of various shades and various degrees of dirtiness saluted me at every point. Khaki men upon khaki men swarmed everywhere. Brigade followed brigade in apparently endless succession; but all clad in the same irrepressible colour, till it became quite depressing. No wonder the townspeople soon took to calling the soldiers "locusts," not merely out of compliment to the gay (p. 018) colour of their costume, but also as aptly descriptive of their apparent countlessness. They seemed like the sands by the seashore, innumerable. They bade fair to swallow up the place.

That last expression, however, suggests yet another point of resemblance. For longer than these men seemed able to remember, the order of the day had been "long marches and short rations." When, therefore, they reached this welcome halting-place they were simply famished; insatiably hungry, they eagerly spent their last coin in buying up whatever provisions had fortunately escaped the commandeering of the Boers. There was no looting, no lawlessness of any kind; and many a civilian gave his last loaf to a starving trooper. There was soon a famine in the place and no train to bring us fresh supplies. All the bakeries of the town were commandeered by the new government for the benefit of the troops; but like the five loaves of the gospel story, "What were they among so many?" I saw the men, like swarms of bees, clustering around the doors and clambering on to the window-sills of these establishments, enjoying apparently the smell of the baking bread, and cherishing the vain hope of being able to purchase a loaf when at last the ovens were emptied.

So too at the grocers' shops, a "tail" was daily formed outside the door, which at intervals was cautiously opened to let in a few at a time of these clamorous customers, who presently retired by the back door, laden more or less with such articles as happened to be still in store; but muttering as they came out "this is (p. 019) like Klondyke," with evident reference not to Klondyke gold, but to Klondyke prices. It was not the traders that needed protection as against the troopers, but the troopers that needed protection as against some of the traders. Even proclamation prices were alarmingly high, as for instance, a shilling for a pound of sugar. Sixpence was the popular price for a cup of tea, often without milk or sugar. The quartermaster whose tent I shared was charged four shillings for a single "whisky and soda," and was informed that if he wanted a bottle of whisky the price would be thirty-five shillings. On such terms tradesmen who, before the war, had laid in large and semi-secret stores now reaped a magnificent harvest. One provision merchant was reported to have thus sold £700 worth of goods before breakfast on a certain Saturday morning, in which case he would perhaps reckon that on that particular date his breakfast had been well earned. It probably meant in part a wholesale army order; but even in that case it would be for cash, and not a case of commandeering after the fashion of the Boers.

A crippled Scandinavian tailor told me that his constant charge, whether to Colonels or Kaffirs, was two shillings an hour; and that he thought his needle served him badly if it did not bring him in £6 a week. About the same time a single-handed but nimble-fingered barber claimed to have made £100 in one week out of the invading British; but his victims declared that his price was a shilling for a shave and two shillings for a clip. At those figures the seemingly impossible comes to pass—if only (p. 020) customers are plentiful enough. Oh for a business in Bloemfontein!

Republican Commandeering.The Republicans of South Africa have always been credited with an ingrained objection to paying rates and taxes even in war time; but they frankly recognise the reasonableness of governmental commandeering, and apparently submit to it without a murmur; especially when it hits most heavily the stranger within their gates. Accordingly, the war-law of the Orange Free State authorises the commandeering without payment of every available man, and of all available material of whatsoever kind within thirty days of war being declared. During those thirty days, therefore, the war-broom sweeps with a most commendable thoroughness; and all the more so, because after that date everything must be paid for at market values. Why pay, if being a little "previous" will serve the same purpose?

A gentleman farmer whom it was my privilege to visit, some fifteen miles out from Bloemfontein, told me he had been thus commandeered to the extent of about £3100; the value of waggons, oxen, and produce, he was compelled gratuitously to supply to his non-taxing government. A specially prosperous store-keeper in the town was said to have had £600 worth of goods taken from him in the same way; but then, of course, he had the compensating comfort of feeling that he was not being taxed! Even Republics cannot make war quite without cost; and by this time some are beginning to discover that it is the most ruinously expensive of all pursuits.

(p. 021) The Republican conscription was equally wide reaching; for every capable man between the ages of sixteen and sixty was required to place himself and his rifle at the service of the State. Even sons of British parentage, being burghers, were not allowed to cross the border and so escape this, in many a case, hateful obligation. Their life was forfeit, if they sought to evade the dread duties of the fighting line, and refused to level reluctant rifles against men speaking the same mother tongue. Some few, however, secured the rare privilege of acting simply as despatch riders, or as members of the Boer ambulance corps.

A touching story.One of the sons of my Methodist farmer friend had been thus employed at Magersfontein, but had now seized the first opportunity of taking the oath and returning to his home. With his own lips he told me that on that fatal field he had found the body of an English officer, in whose cold hand lay an open locket, and in the locket two portraits; one the portrait of a fair English lady, and the other that of a still fairer English child. So, before the eyes of one dying on the blood-stained veldt did visions of home and loved ones flit. Life's last look turned thither! In war, the cost in cash is clearly the cost that is of least consequence. Who can appraise aright the price of that one locket?

Yet, appositely enough, as, that same evening, I was being driven back to town in a buggy and four, a little maiden—perchance like the maiden of the locket—wonderingly exclaimed as she watched the sun sink in (p. 022) radiance behind a neighbouring hill: "Why! just look! The sky is English!" "How so?" asked her father. "Can't you see?" said the child; "it is all red, white, and blue!" which indeed it was!

The price of milk.But our title to this newly-conquered territory was by no means quite so unchallenged as such a complacent and complimentary sky might have led one to suppose. The heavens above us were for the moment English, but scarcely the earth beneath us; and certainly not the land beyond us. Great even thus far had been the price of conquest; but the full sum was not yet ready for the reckoning. No new Magersfontein awaited us, and no new Paardeberg; but the incessant risking of precious life, and much loss thereof in other fashions than those of the battlefield.

Possibly one of the most distressing cases of that kind occurred only two days after near Karee, a few miles beyond Bloemfontein. The officers of the Guards had become famous for their care of their men, and for their constant endeavour to keep them well served with supplementary supplies of food. They foraged right and left, and bargained with the farmers for all available milk and butter and cheese and bread. Men on the march cannot always live on rations only, and good leadership looks after the larder as well as after the lives of the men. On this gracious errand there rode forth from the camp as fine a group of regimental officers as could possibly be found; to wit, the colonel of the Grenadiers, his adjutant and transport officer who, beyond most, were choice young men and goodly; also the colonel of one of the (p. 023) Coldstream battalions, and one orderly. Hiding near a neighbouring kopje was a small body of Zarps watching for a chance of sniping or capturing a seceding Boer. Of them our officers caught sight, and with characteristic British pluck sought to capture them. But on the kopje the Boers found effectual cover, plied their rifles vigorously and presently captured all their would-be captors. As at Belmont, and on the same day of the month, the colonel of the Grenadiers was wounded in two places; the transport officer, the son of one of our well-known generals, lost his right arm; the adjutant, a younger brother of a noted earl, was shot through the heart, and the life of the other colonel was for a while despaired of. It was in some senses the saddest disaster that had yet befallen the Guards' Brigade; and it was the outcome not of some decisive battle, but of a kindly quest for milk.[Back to Contents]

A LONG HALT AT BLOEMFONTEIN

Refits.Before we could resume our march every commissariat store needed to be replenished, and every man required a new outfit from top to toe. If the march of the infantry had been much further prolonged we should have degenerated into a literally bootless expedition, for some of the men reached Bloemfontein with bare if not actually bleeding feet, while their nether garments were in a condition that beggared and baffled all description. Once smart Guardsmen had patched their trousers with odd bits of sacking, and in one case the words "Lime Juice Cordial" were still plainly visible on the sacking. So came that "cordial" and its victorious wearer into the vanquished capital. Others despairingly gave up all further attempts at patching, having repeatedly proved, as the Scriptures say, that the rent is thereby made worse. So they were perforce content to go about in such a condition of deplorable dilapidation as anywhere else would inevitably result in their being "run in" for flagrant disregard of public decorum.

The Canadians took rank from the first as among the very finest troops in all the field, and adopted as their own the following singular marching song:—

(p. 025) "We will follow Roberts,

Follow, follow, follow;

Anywhere, everywhere,

We will follow him!"

Brave fellows that they were, they meant it absolutely, utterly, even unto death. But thus without boots and other yet more essential belongings, how could they?

Remounts.The cavalry was in equally serious plight. It is said that Sir George White took with him into Ladysmith over 10,000 mules and horses, but brought away at the close of the siege less than 1100. Many of the rest had meanwhile been transformed into beefsteak and sausages. We also, during the month that brought us to Bloemfontein had used up a similar number. A cavalryman told me that out of 540 horses belonging to his regiment only 50 were left; and in that case the sausage-making machine was in no degree responsible for the diminished numbers. Yet a cavalryman without a horse is as helpless as a cripple without a crutch. It was therefore quite clear that most of our cavalry regiments would have to remain rooted to the spot till their remounts arrived.

Not until May 1st was another forward move found possible; and during one of those weeks of waiting there happened the Sanna's Post disaster, a grievous surrender of some of our men at Reddersburg, a serious little fight at Karee, and a satisfactory skirmish at Boshof, which made an end of General de Villebois-Mareuil and his commando of foreign supporters of (p. 026) the Boers; but in none of these affairs were the Guards involved.

Regimental Pets.Meanwhile the men during their few leisure hours found it no easy matter to amuse themselves. In the rush for Bloemfontein, footballs and cricket bats were all left behind. There were no canteens and no open-air concerts. The only pets the men had left were pet animals, and of them they made the most. The Welsh, of course, had their goat to go before them, and were prouder of it than ever. The Canadians at Belmont bought a chimpanzee which still grinned at them from the top of its pole in front of their lines, and with patient perseverance, still did all the mischief its limited resources would permit; whereat the men were mightily pleased. The adjoining battalion boasted of possessing a yet more charming specimen of the monkey tribe; a mite of a monkey, and for a monkey almost a beauty; but as full of mischief as his bigger brother.

Strange to tell, the Grenadiers' pet was, of all things in the world, a pet lamb; and of all persons in the world, the cook of the officers' mess was its kindly custodian. "Mary had a little lamb," says the nursery rhyme. So had we!

"Its fleece was white as snow;

And everywhere that Mary went

That lamb was sure to go!"

So was it with ours! Walking amid camp-kettles, and dwelling among sometimes cruelly hungry men that lamb was jokingly called our "Emergency Rations," (p. 027) but it would have had to be a very serious emergency, indeed, to cut short that pet's career. Yet a lamb thus playing with soldiers, and marching with them from one camping ground to another, was well-nigh as odd a sight as I have ever yet seen.

Civilian Hospitality and Soldiers' Homes.During our six weeks of waiting I was for the most part the guest of the Rev. Stuart and Mrs Franklin, whose kindness to me was great with an exceeding greatness. Ever to be remembered also was the hospitality of the senior steward of the Wesleyan Church, who happened, like myself, to be a Cornishman; and from whose table there smiled upon me quite familiarly a bowl of real Cornish cream. Whole volumes would not suffice to express the emotions aroused in my Cornish breast by that sight of sights in a strange land.

Through the kindness of these true friends we were enabled to open the Wesleyan Sunday School as a Soldiers' Home where the men were welcome to sing and play, read, and write letters to their hearts' content. Here also every afternoon from 200 to 700 soldiers were supplied with an excellent cup of tea and some bread and butter for threepence each. A threepenny piece is there called "a tickey," and till the troops arrived that was the lowest coin in use. An Orange Free Stater scorned to look at a penny; but a British soldier's pay is constructed on other lines; and what he thought of our "tickey" tea, the following unsolicited testimonial laughingly proves. It is an unfinished letter picked (p. 028) up in the street, and was probably dropped as the result of a specially hurried departure, when some passing officer looked in and shouted "Lights out!"

Bloemfontein, O.F.S.

Dear Mother,—I can't say I care much for this place. Nothing to see but kopjes all round; and if you want to buy anything, by Jove, you have to pay a pretty price. For instance, cup of tea, 6d.; bottle of ginger beer, 6d.; cigarettes, 1s. a packet. But at the Soldiers' Home a cup of tea is only 3d. Thanks to those in authority, the S.H. is what I call our "haven of rest." I shan't be sorry when I come home to our own haven of rest, as it is impossible to buy any luxuries on our little pay. Just fancy, a small tin of jam, 2s. It's simply scandalous; and the inhabitants seem to think Tommy has a mint of money.

After a while similar Homes were opened in various parts of the town; but this long pause in our progress was a veritable harvest-time for all Christian workers; and especially for those of the S.C.A., who planted two magnificent marquees in the very midst of the men, and had the supreme satisfaction of seeing them crowded night after night and almost all day long. Every Sunday morning I was privileged to conduct one of my Parade Services under their sheltering canvas; and many a time in the course of each succeeding week took part in their enthusiastic religious gatherings.

Here, as at Modder River, secular song was nowhere, while sacred song became all and in all. I am told that sometimes on the march, sometimes amid actual battle scenes, our lads caught up and encouraged themselves by chanting some more or less appropriate music-hall ditty. One battalion when sending a specially large (p. 029) consignment of whizzing bullets across into the Boer lines did so to the accompanying tune of

"You have to have 'em

Whether you want 'em or no!"

Another fighting group, when specially hard pressed, began to sing "Let 'em all come!" But in the Bloemfontein camps I seldom heard any except songs of quite another type; and on one occasion was greatly touched by listening to a Colonial singing a sweet but unfamiliar melody about

"The pages that I love

In the Bible my mother gave to me."

Even among men on active service, many of whom are nearing mid-life, and have long been married, mother's influence is still a supremely potent thing!

Rudyard Kipling's Mistake.Partly as the result of influences such as these, and partly as the result of prohibitory liquor laws, we became the most absolutely sober army Europe ever put into the field. Prior to our coming, no liquor might at any price be sold to a native; and there were in the whole country no beer shops, but only hotels bound to supply bed and board when required, and not liquor only, with the result that this fair land has long been almost as sober as it is sunny.

The sale of intoxicants to the troops was equally restricted, and no liquor could be obtained by them except as a special favour on special terms. Absolutely the only concert or public meeting held in Bloemfontein while the Guards were in the neighbourhood was in connection with (p. 030) the Army Temperance Association, Lord Roberts himself presiding; and concerning him the soldiers playfully said, "He has water on the brain." Through all this weary time of waiting our troops were as temperate as Turks, and much more chaste; so that the soldiers' own pet laureate is reported to have declared, whether delightedly or disgustedly he alone knows, that this outing of our army in South Africa was none other than a huge Sunday School treat; so incomprehensibly proper was even the humblest private and so inconceivably unlike the Tommy Atkins described in his "Barrack-room Ballads," Kipling discovered in South Africa quite a new type of Tommy Atkins, and, as I think, of a pattern much more satisfactory. Nevertheless, in one small detail the laureate's simile seems gravely at fault. In the homeland no Sunday School treat was ever yet seen at which the girls did not greatly outnumber the boys; but on the African veldt the only girl of whom we ever seemed to gain even an occasional glimpse was—"The girl I left behind me."

All Fools' Day.During our stay in Bloemfontein a part of the Guard's Brigade was sent to protect the drift and broken railway bridge across the Modder River at "The Glen"; which was the first really pretty pleasure resort we had found in South Africa since Table Mountain and Table Bay had vanished from our view. Here the Grenadier officers had requisitioned for mess purposes a little railway schoolhouse, cool and shady, in the midst of the nearest approach to a real wood in all the regions round about; and here I purposed (p. 031) conducting my usual Sunday parade, but with my usual Sunday ill-fortune. On arrival I found the whole division that had been encamped just beyond the river had suddenly moved further on, quite out of reach; so the service arranged for them inevitably fell through.

But on Saturday afternoon a set of ambulance waggons arrived, bringing in the first instalment of about 170 wounded men belonging to that same division. It was rumoured that the K.O.S.B.'s, in a sort of outpost affair, had landed in a Boer trap, planted of course near a convenient kopje; with the result that our ambulances were, as usual, speedily required. In the course of the campaign some of our troops developed a decided proficiency in finding such traps—by falling into them!

Nevertheless, two battalions of Guards remained in camp, and they, at any rate, might be confidently relied on for a parade next morning. Indeed, one of the majors in charge, a devout Christian worker, told me he had purposed to himself conduct a service for my men if I had not arrived; and for that I thanked him heartily. Moreover, the men just then were busy gathering fuel and piling it for a camp-fire concert, to commence soon after dark that evening. Clearly, then, the Guards were anchored for some time to come, though their comrades beyond the river had vanished.

I had yet to learn that the coming Sunday was "All Fools' Day," and that for those who had been busy thus scheming it was fittingly so called. At the mess that very evening our usual "orders" informed us that the men would parade for worship at 6.45 next morning; (p. 032) but within a few minutes a telegram arrived requiring the Coldstream battalion and half the Grenadiers to entrain for Bloemfontein at once, thence to proceed to some unnamed destination; and every man to take with him as much ammunition as he could carry. So, instead of a big bonfire and their blankets, the men at a moment's notice had to face a long night journey in open trucks, with the inspiring prospect of a severe fight at that journey's end. Nothing daunted, every man instantly got ready to obey the call; and just before midnight forty truck-loads of fighting men set out, they knew not whither, to meet they knew not what; but cheerily singing, as the train began to move, "The anchor's weighed." It was indeed!

"What does it all mean?" asked one lad of another; but though vague rumours of disaster were rife,—(it proved to be the day of the Sanna's Post mishap),—nothing definite was known; and on the eve of "All Fools' Day" it seemed doubly wise to be wholesomely incredulous. So I retired to my shelter, made of biscuit boxes covered with a rug; and slept soundly till morning light appeared. Then the sun, which at its setting had smiled on two thousand men and their blanket shelters, at its rising looked in vain for men or blankets; all were gone, save a few Grenadiers left for outpost duty. I had come from Bloemfontein for nought. Just behind my shelter stood the pile of firewood neatly heaped in readiness for the previous night's camp fire, but never lighted; and close beside my shelter was spread on the ground fresh beef and mutton, enough to feed fifteen hundred men; but those fifteen hundred were now far away, (p. 033) nobody knew where; and of that fresh meat the main part was destined to speedy burial. Truly enough that Sunday was indeed "All Fools' Day"; though the fooling was on our part of a quite involuntary order!

Yet in face of oft recurring disappointment and disaster the favourite motto of the Orange Free State amply justified itself, and will do to the end. It says Alles zal recht komen; which means, being interpreted, "All will come right." While God remains upon the throne that needs must be!

Eastertide in Bloemfontein.Good Friday for many of us largely justified its name. It was a graciously good day. My first parade in a S.C.A. marquee was not only well attended but was also marked by much of hallowed influence. Then followed a second parade service in the Wesleyan church which was still more largely attended; and attended by men many of whose faces were delightfully familiar. It was an Aldershot parade service held in the heart of South Africa, and in what is supposed to be the hostile capital of a hostile state.

In the course of the afternoon over five hundred paid a visit to our temporary Soldiers' Home for letter writing and the purchase of such light refreshments as we found it possible to provide in that famine haunted city. The evening we gave up to Christian song in that same Soldiers' Home; and when listening to so many familiar voices singing the old familiar hymns, some of us seemed for the moment almost to forget we were not in the hallowed "Glory Room" of the Aldershot Home.

On Easter Sunday at the two parade services in the (p. 034) Town Church the most notable thing was the visible eagerness with which men listened to the old, old story of Eastertide, and the overwhelming heartiness with which they sang our triumphant Easter hymns. There is a capital Wesleyan choir in Bloemfontein; but they told me they might as well whistle to drown the roaring of a whirlwind as attempt "to lead" the singing of the soldiers.

At these Sunday morning parades the church was usually packed with khaki in every part. The gallery was filled to overflowing; chairs were placed in all the aisles on the ground floor; the choir squeezed themselves within the communion rail; and the choir seats were occupied by men in khaki, for the most part deplorably travel-stained and tattered. Soldiers sat on the pulpit stairs; and into the very pulpit khaki intruded, for I was there and of course in uniform. It was a most impressive sight, this coming together into the House of God of comrades in arms fresh from many a hard fought conflict and toilsome march.

At one of these services a sergeant of the 12th Lancers was present; and his was just a typical case. It was at the battle of Magersfontein we had last met. On that memorable morning he and his troop rode past me to the fight; we grasped hands, whispered one to the other "494"[1]; and then parted to meet months after, unharmed amid all peril, in our Father's House in Bloemfontein. The thrill of such a meeting, which represents cases of that kind by the score, no one can fully understand (p. 035) till it becomes inwoven in his own experience. So we met, and remembering the way our God had led us, we sang as few men could

"Praise ye the Lord! 'tis good to raise

Your hearts and voices in His praise!"

How good, supremely good, I have no words to tell!

On that Easter afternoon there came a sudden summons to conduct another soldier's funeral. For a full hour and a half I watched and waited beyond the appointed time, while the digging of a shallow grave in difficult ground was being laboriously completed; and then in the name of Him who is the "Resurrection and the Life," we laid our soldier-brother in his lowly resting place, enwrapped only in his soldier-blanket. Meanwhile, in accordance with a touching Anglican custom, there came into the cemetery a long procession of choir boys and children singing Easter hymns, joining in Easter liturgies, and then proceeding to lay on the new made graves an offering of Easter flowers.

At the Easter evening service I was surprised to see in the Wesleyan church another dense mass of khaki. Every man had been required to procure a separate personal "pass" in order to be present, and the evening was full of threatenings, threatenings that in due time justified themselves by a terrific thunderstorm, which resulted in nearly every tunic being drenched before it could reach its sheltering tent. Yet in spite of such forbiddings the men came in from the outlying camps, literally by hundreds, to attend that Easter evening service; and I deemed their presence there a notable (p. 036) tribute to the spiritual efficiency of spiritual work among our troops the wide world over.

Easter Monday, as in England so in Bloemfontein, is a Bank holiday, and usually devoted to picnicking in The Glen, till the war put its foot thereon, as well as on much else that was pleasurable. My most urgent duty that day was the conducting of another military funeral; and thereupon in the cemetery I saw a triple sight significant of much.

At the gate were some soldiers in charge of a mule waggon on which lay the body of a negro, awaiting burial. In the service of our common Queen that representative of the black-skinned race had just laid down his life. Inside the gates two graves were being dug; one by a group of Englishmen for an English comrade, and one by a group of Canadians for a comrade lent to us for kindred service by "Our Lady of the Snows." So now are lying side by side in South African soil these two typical representatives of the principal sections of the Anglo-Saxon race; their lives freely given, like that of their black brother, in the service and defence of one common heritage—that Christian empire which surely God himself has builded. Camp and cemetery alike teach one common lesson, and by the lips of the living and the dead enforce attention to the same vast victorious fact! Next day it was an Australian officer I saw laid in that same treasure-house of dead heroes. He that hath eyes to see let him see! This deplorable war, which thus brought together from afar the builders and binders of the empire, in an altogether amazing measure made (p. 037) them thereby of one mind and heart. It is life arising out of death; and surely every devout-minded Englishman will learn at last to say "This is the Lord's doing; and it is marvellous in our eyes!"

The Epidemic and the Hospitals.The first military funeral since the reoccupation of Bloemfontein by the British it fell to my lot to conduct two days after our arrival. A fine young guardsman who had taken part in each of our four famous battles, and in our recent march, just saw this goal of all our hopes and died. The fatal symptoms were evidently of a specially alarming type, for he was hastily buried with all his belongings, his slippers, his iron mug, his boots, his haversack, and the very stretcher on which he lay; then over all was poured some potent disinfectant. It was a gruesome sight! So to-day he lies in the self-same cemetery where rests many a British soldier who fell not far away in the fights of fifty years ago. It was British soil in those distant days, and is British soil again, but at how great cost we were now about to learn.

That guardsman was the first fruits of a vast ingathering. In the course of the next few weeks over 6000 cases of enteric sprang up in the immediate neighbourhood of that one little town; and 1300 of its victims were presently laid in that same cemetery, which now holds so much of the empire's best, and towards which so many a mother-heart turns tearfully from almost every part of the Anglo-Saxon world. It was the after-math of Paardeberg, which claimed more lives long after, than in all its hours of slowly intensifying agony! Boers and (p. 038) Britons, both together, there were vastly fewer who sighed their last beside the Modder River banks than the sequent fever claimed at Bloemfontein; and all through the campaign the loss of life caused by sickness has been so much larger than through wounds as to justify the soldiers' favourite dictum respecting it: "Better three hits than one enteric."

Such an epidemic, laying hold as it did in the course of a few weeks of one in five of all the troops within reach of Bloemfontein, is quite unexampled in the history of recent wars; and the Royal Army Medical Corps can scarcely be censured for being unable to adequately cope with it. They were 900 miles from their base, with only a broken railway by which to bring up supplies. The little town, already so severely commandeered by the Boers, could furnish next to nothing in the way of medical comforts or necessities. Every available bed, or blanket, or bit of sheeting, was bought up by the authorities; but if every private bedroom in the place had been ransacked, the requirements of the case even then could scarcely have been met. Possibly that ought to have been done, but all through this campaign our army rulers have been excessively tender-handed in such matters; forgetting that clemency to the vanquished is often cruelty to the victors. So in Bloemfontein healthy civilians, whether foes or friends, slept on feather beds, while suffering and delirious soldiers were stretched on an earthen floor that was sodden with almost incessant rain. Neither for that rain can the army doctors be held responsible, though it almost drove them to despair. Nor (p. 039) was it their fault that the Boers were allowed at this very time to capture the Bloemfontein waterworks, and shatter them. Bad water at Paardeberg caused the epidemic. Bad water at Bloemfontein brought it to a climax. In this little city of the sick the medical men had at one time a constant average of 1800 sufferers on their hands; mostly cases of enteric which, as truly as shot and shell, shows no respect of persons. Not only our fighting-men—soldiers of high degree and low degree alike—but non-combatants, chaplains, army scripture readers, war correspondents, doctors, and army nurses, it remorselessly claimed and victimised. In such a campaign the fighting line is not the chief point of peril, nor the fighting soldiers the only sufferers. Hospital work has its heroes, though not its trumpeters, and many a man of the Royal Army Medical Corps has as faithfully won his medal as any that handled rifle.

All hands and houses to the rescue.Our "Kopje-Book Maxims" told us that "two horses are enough to shift a camp—provided they are dead enough." Either the camp or the horses must be quickly shifted if pestilence is to be kept at bay; yet in spite of all shiftings, of all sanitary searchings and strivings, the fever refused to shift; the field hospitals were from the first hopelessly crowded out; and the city of death would quickly have become the city of despair, but for the timely arrival of sundry irregular helpers and organisations that had been lavishly equipped and sent out by private beneficence. Such was the huge Portman Hospital. In the Ramblers' Club and Grounds, the Longman Hospital was housed; (p. 040) and here I found Conan Doyle practising the healing art with presumably a skill rivalling that with which he penned his superb detective tales. In the forsaken barracks of the Orange Free State soldiery, the Sydney doctors established their house of healing, assisted by ambulance men and ambulance appliances unsurpassed by anything of the kind employed in any other part of Africa. Australia, like her sister colonies, sent to us her best; and bravely they bore themselves beside our best.

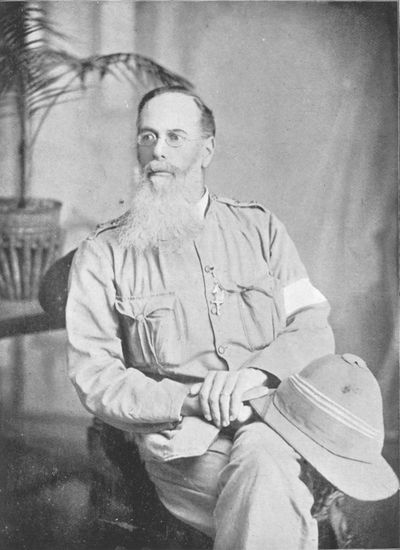

From a photograph taken at Pretoria, June 1900

Rev. T. F. Falkner, M.A. Chaplain to the Forces.

Chaplain to the First Division and to the Guards' Brigade, South African Field Force, 1899-1900.

To relieve the pressure thus created almost every public building in the town was requisitioned for hospital purposes; schools and clubs and colleges, the nunnery, the lunatic asylum, and even the stately Parliament Hall with its marble entrance and sumptuous fittings. The presidential chair, behind the presidential desk, still retained its original place on the presidential platform; but,—"how are the mighty fallen!" I saw it occupied by an obscure hospital orderly who was busy filling up a still more obscure hospital schedule. The whole floor of the building was so crowded with beds that all the senatorial chairs and desks had perforce been removed. The Orange Free State senators sitting on those aforesaid chairs had resolved in secret session, only a few eventful months before, to hurl in England's face an Ultimatum that made war inevitable, and brought our batteries and battalions to their very doors. But now they were fugitives every one from the city of their pride, which they had surrendered without striking a solitary blow for its defence; while the actual building in which their lunacy took final shape, and launched itself (p. 041) on an astonished Christendom, I beheld full to overflowing with the deadly fruit of their doing. In the very presence of the president's chair of state, here a Boer, there a Briton, it may be of New Zealand birth or Canadian born, moaned out his life, and so made his last mute protest against the outrage which rallied a whole empire in passionate self-defence.

Among the more than thousand victims the Bloemfontein fever epidemic claimed, few were more lamented than a sergeant of the 3rd Grenadier Guards, who, according to the Household Brigade Magazine, had a specially curious experience in the assault on Grenadier Hill at the battle of Belmont, for "he was hit by no less than nine separate bullets, besides having his bayonet carried away, off his rifle, by another shot, making a total of ten hits. He continued till the end of the action with his company in the front of the attack, where on inspection it was found he had only actually five wounds; but besides some damage to his clothing had both pouches hit and all his cartridges exploded. He did not go to hospital till the next day, when he felt a little bruised and stiff." It really seemed hard to succumb to enteric after such a miraculous escape from the enemies' murderous fire.

Church of England Chaplains at work.The following letter by the Rev. T. F. Falkner refers to this period, and was sent originally to the Chaplain-General; but is here published, slightly abridged, as an excellent illustration of the spirit and work of the many chaplains of the Church of England who have taken part in this campaign:—

(p. 042) "I was particularly anxious that you should know the luxury in which we are living in the matter of Church privileges, and the keen appreciation which our people show of that which is so freely offered. Nothing can exceed the kindness of the dean and his clergy. They allow us to have the use of the cathedral on Sunday mornings at nine o'clock for a parade service for the Guards, and at 5.30 on Sunday evenings we have a special evensong for the convenience of officers and men to enable them to get back to barrack or camp in good time; in addition to this, we have permission to hold a special mission service for soldiers on Friday evenings at 6.30. There is a daily celebration as well as Morning and Evening Prayer and Litany, while on Sundays there are three celebrations of Holy Communion. These are luxuries to us wayfarers on the veldt. Now for the appreciation of them. On the Sunday after we came in, the cathedral choir volunteered their help at our nine o'clock (Guards') parade, and the service was home-like and hearty. The drums were there and rolled at the Glorias, and 'God Save the Queen,' which was sung because it was a parade service. I spoke to the men on the blessings of a restful hour of worship in an English church after our journeyings, and of the mercies which had been granted to us, basing what I had to say on 'It is good for us to be here.' At the morning service at 10.30 there was a large number of the headquarter staff present, many of whom, Lord Roberts included, stayed to the celebration.... At 7.30, the ordinary hour for evensong, long before the service began the church was literally packed with officers and men, one vast mass of khaki; all available chairs and forms were got in, and officers were put up into the long chancel wherever room could be found for them. The heartiness of that service, the reverence and devoutness of the men, the uplifting of heart and voice in the familiar chants and hymns, the clear manly enunciation of the Articles of our Faith, and the ready responses, all combined to make the service a grand evidence of the religious side of our men and a striking testimony to their desire to worship their God in the beauty of holiness. Many of us will remember that Sunday night with thankfulness. Coney preached us a very excellent sermon. The few civilians who were able to get in were much struck by the evident sincerity and devout behaviour of the men who surrounded them. And yet the Boers say 'the English must lose because they have no God.' One of the clergy told me a day or two after we got here that he met one of our men outside the cathedral as he was (p. 043) walking along, and the soldier accosted him. 'Beg pardon, sir, is that an English church?' 'Yes,' said the clergyman. 'Might I go in, sir?' 'Why, of course,' was the reply, 'it is open all day.' 'Thank you, sir; I should just like to go in and say a prayer for the wife and children;' and in he went.

"I felt after our first experience that it was hardly fair to oust so many of the regular worshippers from their own place of worship, and so we arranged for the extra service at 5.30. It was to be purely a soldiers' service. But a word or two about the Friday evening special Lenten service. Familiar hymns, a metrical litany, and part of the Commination Service were gladly joined in by a large number of men, the cathedral being more than half full, and the archdeacon gave us a very helpful address. After that service a good number of men stayed behind, at our invitation, to practise psalms and hymns for the soldiers' evening service on the following Sunday, a precaution which served its purpose well. At that service the church was filled; Lord Roberts came to it, and it was an ideal soldiers' service. Coney and I took the service, Norman Lee and Southwell read the lessons, Blackbourne was at the organ, and the dean preached. One of the staff officers said afterwards that he had never enjoyed a service so much, and I think many others had similar feelings. But the flow of khaki-clad worshippers had not ceased, for no sooner had our 5.30 service ended than men and officers began coming in for the 7.30 ordinary service, and at that the chancel and more than half the body of the church was again filled with our troops. It was cheering to see and comforting to share in.

"The morning of this Sunday I spent at Bishop's Glen, about fourteen miles up the line, close to the bridge over the Modder River which was blown up directly we got here, where two battalions of the Guards were afterwards sent. I had to go up in great haste on the Saturday to bury the adjutant of the 3rd Grenadiers, who was killed the day before; a very sad task for me, for having been with the battalion all along, I had got to know him well and to appreciate him highly, as every one did who knew him. I got to camp about 5.30 on Saturday evening, after three and a half hours' heavy travelling along a muddy track over the veldt, through dongas and drifts, and we laid him to rest on a little knoll overlooking the well-wooded banks of what is there a pretty river, a short distance only from the broken bridge, which stood out against a background of shrubs and trees on the river side, and struck me as a fitting emblem of a strong (p. 044) and useful life smitten down suddenly by an unseen hand. I stayed the night at Glen, where Grenadiers and Coldstreams took care of me, and on Sunday morning at seven we had our parade service, followed by a celebration at the railway station, at which we had a nice number of communicants.

"We find the hospital work here very heavy. There are no less than ten public buildings in use as hospitals in the town: in addition, of course, to our field hospitals, which are full. For a short time last week I was left to do all this with two chaplains besides myself. The chaplains here are splendid, so keen and self-denying, nothing seems too much trouble; all going strong and working hard. It is a pleasure to be with such men. We are all distressed at our inability to do more, and conscious of our failure to do what we would wish; but we do what we can. The S.C.A. has two tents and are working on good lines, and the men appreciate them. Lowry and I have walked the whole way so far, save that I had a lift from Jacobsdal to Klip Drift, and I am thankful to be able to say I have not been other than fit all through. All the others have had horses to ride: they are welcome to them. I am a bit proud of having had a share in that march from Klip Drift to Bloemfontein, and am thankful for the strength that was given me to do it. I am jealous for the honour of the department, and all I want at the end of the campaign is that the generals should say, the Church of England chaplains have done their duty well. One said to me the other day, 'I should like to be mentioned in despatches.' I replied, 'I have no such wish. To do that you must go where you have no business to be.' Our chaplains are brave men; there's not one who would flinch if told to go into the firing line; but the generals all say that our place is at the field hospital; moving quietly amongst the sick and wounded when they are brought in, and burying the dead when they are carried out. There's not one of our chaplains out here who has not earned, so far as I can gather, kind words from those with whom he serves, and I think you will find your selection has been more than justified.