Photo by Middlebrook, Durban.

Twenty thousand men encamped under General Buller.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of With the Naval Brigade in Natal (1899-1900), by

Charles Richard Newdigate Burne

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: With the Naval Brigade in Natal (1899-1900)

Journal of Active Service

Author: Charles Richard Newdigate Burne

Release Date: April 21, 2008 [EBook #25117]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH THE NAVAL BRIGADE ***

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Photo by Middlebrook, Durban.

Twenty thousand men encamped under General Buller.

1899-1900

Journal of Active Service

KEPT DURING THE RELIEF OF LADYSMITH AND SUBSEQUENT OPERATIONS IN NORTHERN NATAL AND THE TRANSVAAL, UNDER GENERAL SIR REDVERS BULLER, V.C., G.C.B.

BY

LONDON

EDWARD ARNOLD

1902

For the Army, our comrades and our friends,

the Navy has nothing but

the deepest respect and admiration.

This Journal, completed before leaving the front in October, 1900, does not assume to be more than a somewhat rough and unadorned record of my personal experiences during ten months of the South African (Boer) Campaign of 1899-1900 while in detached command of two 12-pounder guns of H.M.S. Terrible and H.M.S. Tartar. Having been asked by some of my friends to publish it, I am emboldened to do so, in the hope that the Journal may be of interest to those who read it, as giving some idea of work done by a Naval Brigade when landed for service at a most critical time. A few notes on Field Gunnery are appended with a view to give to others a few ideas which I picked up while serving with the guns on shore, after a previous experience as Gunnery Lieutenant in H.M.S Thetis and Cambrian.

For the photographs given I must record my thanks to Lieutenant Clutterbuck, R.N., Mr. Hollins, R.N., and other kind friends.

C.R.N.B.

April, 1902.

CHAPTER I

PAGE

Outbreak of the war—The Transport Service and despatch of Army Corps from Southampton—Departure of a Naval Brigade from England and landing at Capetown and Durban—I join H.M.S. Philomel 1-10

CHAPTER II

I depart for the front with a Q.-F. Battery from H.M.S. Terrible—Concentration of General Buller's army at Frere and Chieveley—Preliminary bombardment of the Boer lines at Colenso—The attack and defeat at Colenso—Christmas Day in camp 11-21

CHAPTER III

Life in Camp and Bombardment of the Boer lines at Colenso—General Buller moves his army, and by a flank march seizes "Bridle Drift" over the Tugela—The heavy Naval and Royal Artillery guns are placed in position—Sir Charles Warren crosses the Tugela with the 5th Division, and commences his flank attack 22-32

CHAPTER IV

Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz—General Buller withdraws the troops and moves once more on Colenso—We hold Springfield Bridge—Buller's successful attack on Hussar Hill, Hlangwane, and Monte Christo—Relief of Kimberley 33-44

Passage of Tugela forced and Colenso occupied—Another move back across the river to Hlangwane and Monte Christo—The Boers at length routed and Ladysmith is relieved—Entry of Relief Force into Ladysmith—Withdrawal of H.M.S. Terrible's men to China—I spend a bad time in Field Hospital—General Buller's army moves forward to Elandslaagte—Boers face us on the Biggarsberg 45-58

CHAPTER VI

End of three weary months at Elandslaagte—A small Boer attack—The advance of General Buller by Helpmakaar on Dundee—We under General Hildyard advance up the Glencoe Valley—Retreat of the Boers to Laing's Nek—Occupation of Newcastle and Utrecht—We enter the Transvaal—Concentration of the army near Ingogo—Naval guns ascend Van Wyk, and Botha's Pass is forced—Forced march through Orange Colony—Victory at Almond's Nek—Boers evacuate Majuba and Laing's Nek—Lord Roberts enters Pretoria—We occupy Volksrust and Charlestown 59-72

CHAPTER VII

Majuba Hill in 1900—We march on Wakkerstroom and occupy Sandspruit—Withdrawal of H.M.S. Forte's men and Naval Volunteers from the front—Action under General Brocklehurst at Sandspruit—I go to hospital and Durban for a short time—Recover and proceed to the front again—Take command of my guns at Grass Kop—Kruger flies from Africa in a Dutch man-of-war—Many rumours of peace 73-86

CHAPTER VIII

Still holding Grass Kop with the Queen's—General Buller leaves for England—Final withdrawal of the Naval Brigade, and our arrival at Durban—Our reception there—I sail for England—Conclusion 87-100

Gunnery Results: The 12-pounder Q.-F. Naval gun—Its mounting, sighting, and methods of firing—The Creusot 3"-gun and its improvements—Shrapnel fire and the poor results obtained by the Boers—Use of the Clinometer and Mekometer—How to emplace a Q.-F. gun, etc., etc. 101-120

APPENDIX I

Hints on Equipment and Clothing for Active Service 121-128

APPENDIX II

Extracts from some of the Despatches, Reports, and Telegrams regarding operations mentioned in this Journal 129-145

APPENDIX III

Diary of the Boer War up to October 25th, 1900 146-152

APPENDIX IV

The Navy and the War: A Résumé of Officers and Men mentioned in Despatches for the Operations in Natal 153-156

Outbreak of the war—The Transport Service and despatch of Army Corps from Southampton—Departure of a Naval Brigade from England and landing at Capetown and Durban—I join H.M.S. Philomel.

During a short leave of absence in Scotland, after my return from Flag-Lieutenant's service in India with Rear-Admiral Archibald L. Douglas, that very kind friend, now Lord of the Admiralty, appointed me (5th October, 1899) to the Transport Service at Southampton, in connection with the embarkation of the various Army Corps for the war in South Africa. As the summons came by wire, I had to leave Stirling in a hurry, collect my various goods and chattels in London, and make the best of my way to Southampton. I reported myself at the Admiralty Transport Office on Monday the 9th, and at once commenced work, visiting certain ships with Captain Barnard, the Port Transport Officer, and picking up the "hang" of the thing, and what was wanted. Captain Graham-White, R.N., came down in the afternoon to take charge of our proceedings. From that date up to the 22nd, or thereabouts, we Transport Lieutenants simply had charge (p. 002) of certain vessels fitting out, and had to inspect for the Admiralty the many freight and transport ships which came in from other centres, such as London, Liverpool, etc., to be officially passed at Southampton; among others the Goorkha and Gascon, two Union Liners, came particularly under me, and I shall always remember the courtesy of their officials, particularly Captain Wait and the indefatigable Mr. Langley, who saw that we transport officers were well looked after on board each day. Everything in connection with this Line seemed to me during my time at Southampton to be very well done, and so our work went swimmingly.

Besides myself were Lieutenants McDonald, Nelson, and Crawford, R.N., as Transport Officers, and we co-operated with a staff of military officers under Colonel Stacpole, D.A.A.G., with whom we got on very well, so that we ran the work through quickly and without a hitch. Sir Redvers Buller left Southampton in the Dunottar Castle on the 15th October, and we all saw him off; in fact, McDonald and I represented the Admiralty at the final inspection of the ship before sailing. There was, of course, a scene of great enthusiasm, and many people were there, among whom were Sir Michael Culme Seymour, Alexander Sinclair his Flag-Lieutenant, and Lady and Miss Fullerton. All this time we were more than busy inspecting and getting ships ready up to the 22nd, when the departure of the First Army Corps commenced; we got away five transports that day within half an hour of each other, all taking some 1,500 men; they were, if my memory serves me, the Malta, Pavonia, Hawarden Castle, Roslin Castle, and Yorkshire; the next few days we did similar work from 8 a.m. till dark, getting away about three ships a day on an average.

During the week Commander Heriz, R.N., and myself, (p. 003) representing the Admiralty, inspected the hospital ships Spartan and Trojan before their start; they had been fitted out under the Commander's superintendence, and were perfect; in fact, one almost wished to be a sick man to try them! All these continued departures aroused great public interest; on one day we had the Commander-in-Chief (Lord Wolseley), Lord Methuen, Sir William Gatacre, and many other Generals; and on another the Duke of Connaught came to see the 1st Bn. Scots Guards off in the Nubia and gave them a message from the Queen; he came again a few days later to see his old regiment, the Rifle Brigade, off in the German, and he and the Transport Officers were photographed many times. I was told afterwards that my own portrait appeared very often in the cinematographs of these scenes, which were then very popular and were exhibited to crowded audiences in all the London and Provincial Music Halls and elsewhere. I was very pleased on this occasion to meet my old First Lieutenant of the Cambrian, now Commander Mark Kerr, R.N., who was also seeing the Rifle Brigade off with a party of relatives whom I took over the Kildonan Castle.

Here I may mention, to show the different rates of speed, that the German carrying the Rifle Brigade, actually arrived at Capetown some hours after the Briton (in which I myself left later on for South Africa), although it started ten days before us. I have very pleasant recollections of being associated with Major Edwards of the Berkshire Regiment in embarking the Reserves of the 3rd Bn. Grenadier Guards in the Goorkha, which ship I had been superintending for so long; I was able to get their Commanding Officer, Major Kincaid, two good cabins, for which I think he was much obliged to me. These Reserves were going to Gibraltar to pick up the main Battalions of (p. 004) their regiment which took part later on (3rd and 4th November) in Lord Methuen's actions at Belmont and Graspan.

After the 27th October the transport ships left Southampton in ones and twos, and we were not so hard pushed; in fact, the work was becoming rather monotonous, till, on the evening of the 2nd November, our Secretary, Mr. Alton, R.N., rushed up to me with a wire telling me to be prepared immediately to leave for the Cape. I was very pleased, and thought myself extremely lucky to get out to the scene of war with a chance of going to the front; and after saying a hurried good-bye to all my friends I left Southampton on the 4th November in the Briton; my father[1] saw me off and gave me some letters of introduction; Lord Wolseley also kindly wrote about me to Sir Redvers Buller; all my old colleagues of the Transport Service gave me a most cordial send-off, and we steamed out of the docks about 7 p.m. in heavy rain, which did not, however, damp the enthusiasm of hundreds of people who waited to see the last of us. In saying farewell to the Transport Service I could not help thinking how much courtesy and assistance we transport officers received from the captains and officers of all the ships under our inspection, and how much we admired their keen feeling and hard work in the interests of the public service. I hope this may be recognised when war rewards are given.

Our voyage was a good one, being calm enough after the first day, and all going well up to Madeira (where I landed for the sixth time) as well as on the onward voyage in which we went through the usual routine of ship life until we arrived at the Cape on Monday, 20th November. The Bay was full of transports, and they seemed still to be pouring in every hour; we did not hear much news (p. 005) except that Ladysmith was still safe, and we at once entrained for Simon's Bay, a pretty train journey of about an hour and a half, where the fleet were lying. Now commenced the bad luck of the Brigade "wot never landed," we all got drafted to various ships instead of going to the front in a body as we had hoped and expected, and my lot was to join the flagship Doris. Much to our disappointment a Naval Brigade had been landed the day before our arrival for Lord Methuen's force; we ourselves were therefore regarded for the moment as hardly wanted, and the Admiral was, we were told, dead against landing any more sailors. So we were both afflicted and depressed. I had, however, a pleasant time on the Doris, and found myself senior watch keeper on board. At night many precautions were taken in the fleet; guards were landed in the dockyard with orders to fire on any suspicious boat, and a patrol boat steamed round the fleet all night up to daylight with similar orders; we ourselves often went on shore for route marching and company drill and had a grand time.

I may mention, in passing, that all the bluejackets who were landed at Simon's Bay for shore duty were fitted with khaki suits, viz., tunics and trousers and hat covers, drawn from the military stores. With the trousers the men wore brown gaiters, and each man was provided with two pairs of service boots; they all wore their white straw hats fitted with khaki covers and looked very workmanlike in heavy marching order. The Marines also wore khaki and helmets, and had stripes of marine colours (red, blue and yellow) on the helmets to distinguish the Corps. Each batch of bluejackets that were sent to the front, about twelve men in a batch, was allowed two canvas bags to hold spare clothes and other gear, and took three days' provisions and water. The haversacks were all (p. 006) stained khaki with Condy's fluid, and the guns were all painted khaki colour.

We saw a great many people at Capetown, and while there, Colonel Gatcliffe, Royal Marines, the head Press censor, told Morgan and myself a lot of instructive facts about the work at the Telegraph Offices, and how all foreign telegrams in cipher to South Africa giving news to the Boers, as well as those from them, had been stopped. Some 300 telegrams sent after Elandslaagte by Boer agents at Capetown had been thus suppressed. When we saw Colonel Gatcliffe he was busily engaged passing telegrams, which had to be read and signed by him at the Telegraph Office before they were allowed to be despatched.

All went well at Simon's Bay until November 24th, when we heard of Lord Methuen's fight and heavy casualties at Belmont, followed soon by news of the heavy loss (105 killed and wounded) incurred by the Naval Brigade at Graspan chiefly among the marines. I think that the general idea in the fleet was admiration for our comrades and gratitude to Lord Methuen for giving the Navy a chance of distinction; but I am told these views were not shared by our Chief. A force of forty seamen and fifty marines were now ordered off to the front at once to fill up these casualties. Naturally we all wanted to go, but the Admiral could not send us and drafted us off to various ships, my own destination being H.M.S. Philomel, then at Durban, which I reached in the transport Idaho, a Wilson Liner. We had on board a Field Battery and other details with six guns and 250 horses. I was much interested in the horses, who had a fine deck to themselves and were very fit; they were in fact 'Bus horses, and very good ones.

There were some Highland officers and others on board who had been wounded and were now going back to Natal (p. 007) after recovery; they told us how cunning the Boers were in selecting positions; one saw nothing of them, they said, on a hill but the muzzle of their rifles; they are only killed in retreat; they pick out any dark object as a man, such as a great-coat, training their rifles on it so as to fire directly he rises and advances. One of the officers told us how he saw at Elandslaagte a Scotchman who had been put by the Boers in their firing line with his hands tied behind his back because he had refused to fight for them; apparently the man escaped uninjured and was taken prisoner with the rest after the fight by our Lancers, swearing when liberated many oaths of vengeance on the Boers. Colonel Sheil told one of our officers, Commander Dundas, who was in charge of him and other prisoners on board the Penelope at Simon's Bay, that the only fault of our men was their rashness, and our Cavalry did not, he said, throw out sufficient scouting parties, missing himself and others on one occasion by not doing so; the Boers had not reckoned, he said, on Naval guns being landed, and placed great reliance on European interference. In his opinion, the war would be over the moment we entered Boer territory, and everything seemed at the moment to point to this conclusion. These Boer prisoners, who were all got at Elandslaagte, talked English well, and appeared, by all accounts, to have a good feeling and respect for the English, but they were very down upon the capitalists and others whom they blamed for the war.

To-day, at sea, as I write this (28th November), a S.E. breeze makes it delightfully cool. Indeed, I found the climate of Capetown, although the hot weather was beginning, delightful; a regular champagne air and a very hot sun, yet altogether a nice dry heat which quickly brought all the skin off my face at Simon's Bay after one (p. 008) day's march with the Battalion up the hills. I expect to find Natal much damper, and no doubt it will be very wet and cold at night in the hill country.

Thursday, 30th November.—The wind which has been blowing in our teeth has now moderated, so we may reach Durban earlier than we hoped, as we are only about 300 miles off. I watched the battery horses being exercised and fed this morning; they are mostly well accustomed to the ship's motion, but it is amusing sometimes to see about a dozen stalwart gunners shoving the horses behind to get them back to their stalls and eventually conquering after much energy and language, and after desperate resistance on the part of the horses; these old 'Bus horses are strong and fit, and have very good decks forward and aft for their half-hour exercise each day; while they are exercising, their stalls are cleaned out and scrubbed with chloride of lime. It is most interesting to watch their eagerness to go to their food, for they are always hungry!

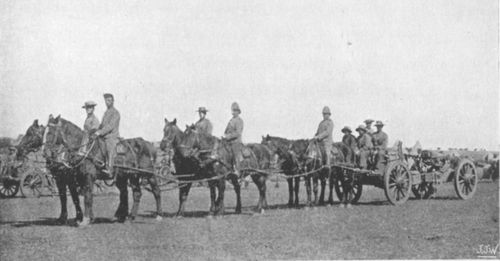

A Battery crossing the Little Tugela.

Naval Battery of 4.7's and 12-pounders at Durban.

Friday, 1st December.—We arrived at Durban at 5 a.m. and anchored in the roadstead. In the Bay are H.M.S. Terrible and Forte; also a Dutch man-of-war, the Friesland, a fine looking cruiser; there are also eleven transports at anchor. Inside the Bay are the Philomel (my ship) and Tartar, besides a lot of other transports, including my old friend the Briton. Durban is a striking place from the sea; very green and cultivated, and with rows of houses extending along a high ridge overlooking the town. It all looks very pretty and one might fancy one's self in England. A strong breeze is blowing, so it is quite cool. An officer from the Forte tells us that Estcourt is relieved and that the Boers are massing south of Colenso ready for a big fight. Our army have apparently to bridge some ravines before advancing. The guns of the Forte and (p. 009) Philomel are at Estcourt with landing parties. Commander Dundas and Lieutenants Buckle and Dooner join the Forte and I join the Philomel. Tugs came out at 1 p.m. and took us in over the bar; we passed close to the Philomel and were heartily cheered; then we went alongside the jetty, where staff officers came on board with orders. Commander Holland (Indian Marine) is here in charge of Naval transport and is an old acquaintance, as we met last year at Bombay. I got on board the Philomel without delay and found myself Captain of her, as her Captain (Bearcroft) had gone to take the Flag-Captain's place with Lord Methuen's force, and Halsey, the First Lieutenant, was at Estcourt with some 12-pounder guns. About thirty men of the Philomel are on shore under two officers, and one of her 4.7 guns is up at Ladysmith. I hear that all guns north of Pietermaritzburg are under command of Captain Jones, R.N., of the Forte; and, in fact, all the ships here at present, viz., the Terrible, Forte, Philomel, and Tartar, have landing parties at the front.

I reported myself to Commander F. Morgan, senior officer of the Tartar, who was pleased to see me as he is an old friend, I having served with him in 1894 in the Royal yacht (Victoria and Albert), from which we were both promoted on the same day (28th August, 1894). I also called on the Commandant of Durban, Captain Percy Scott of the Terrible, at his headquarter office in the town. I found him busily engaged in making-up plans and photos of Durban, as well as his designs for field and siege mountings for the 4.7 and 12-pounder guns, to forward to Admiral Douglas, my late Commander-in-Chief; he showed them to me, and ordered me to take over command of the Philomel for the present. I have met a lot of old friends, and find the ship itself clean, smart, and comfortable. (p. 010) The weather is changeable and very hot. Captain Scott has ordered martial law in the town, and everyone found in the streets after 11 p.m. is locked up. The story goes that Captain Scott himself was locked up one night by mistake!

Tuesday, 5th December.—Captain Scott sent on board a kind letter from the Governor of Natal (Sir Walter Hely-Hutchinson) who has spoken to Sir Redvers Buller about me. An early advance is expected on Colenso, and it seems on the cards that some strategic move will soon be made to outflank the Boers and commence relief operations on behalf of poor Ladysmith.[Back to Contents]

I depart for the front with a Q.-F. Battery from H.M.S. Terrible—Concentration of General Buller's army at Frere and Chieveley—Preliminary bombardment of the Boer lines at Colenso—The attack and defeat at Colenso—Christmas Day in camp.

On the 6th December there was much rejoicing in the fleet on account of an order from Headquarters that a battery of eight Naval guns was to go to the front to reinforce Sir Redvers Buller. Lieutenant Ogilvy, of the Terrible, was appointed to command, while Melville of the Forte, Deas of the Philomel, and myself, were the next fortunate three who were to accompany it. The battery, drilled and previously prepared by Captain Scott and Lieutenant Drummond, entrained the next day (7th) for its destination; but as I had to remain behind awaiting a wire from Headquarters, I was unable to start till the next morning, when I left for Frere, accompanied by my servant, Gilbert of the Marines. What a day of excitement we passed through, and how much we, who were off to the front, felt for those left behind! I gave over command of the Philomel to Lieutenant Hughes, the men gave me three cheers, and I left Durban amid many farewells and congratulations at my good luck.

Reaching Pietermaritzburg early on the 8th, we went onwards after breakfast to Estcourt. The railway is a succession of sharp curves and steep gradients and is a single line only. All the bridges on the line are carefully guarded, as far as Mooi River, by Natal Volunteers. I (p. 012) was much struck with the outlook all the way to Estcourt; a very fine country, beautifully green, with a succession of hills, valleys, and small isolated woods; in fact, if the country was more cultivated one might have thought it England, but it seems to be mostly grass land and mealy (Indian corn) fields. At Mooi River a farmer got into the train who had been driven from his farm near Estcourt when the Boers invaded Natal; he had lost all his cattle and clothes, while everything on his farm had been wantonly destroyed, and the poor fellow was now returning to the wreck with his small daughter.

On reaching Estcourt in the afternoon we found to our dismay that we could not get on any further for the moment; so I walked up to see Halsey of the Philomel, at his camp about half a mile from the station, and took him some newspapers. We had a bathe in the Tugela River, and I afterwards met Wyndham of the 60th Rifles who was A.D.C. to the Governor of Ceylon while I was Flag-Lieutenant to Admiral Douglas, and we were mutually pleased to meet again so unexpectedly. The Somersets marched in during the course of the morning from Nottingham Road; they all looked very fit, but seem to have the somewhat unpopular duty of holding the lines of communication.

Here I met also Lady Sykes and Miss Kennedy, doing nursing; they were staying at a Red Cross sort of convent close to the station. Lady Sykes gave me some books and wished me the best of luck, at which I was pleased. I believe she is writing a book of her experiences in the war and I shall be much interested to read it when I get home. It came on to pour with rain, with vivid lightning, about 8 p.m., so I was thankful to be under cover at the station; the poor soldiers outside were being washed out of their tents, and some unfortunate Natal Mounted (p. 013) Volunteers, who only arrived an hour beforehand, had no tents at all and had a very poor time of it.

Eventually I got off by train next morning (9th) for Frere, Captain Reeves, R.S.O., of the Buffs, who did me many kindnesses later on, having secured a compartment for me in a carriage which was shunted for the night, and in which I was very comfortable, although disturbed by continuous shuntings of various trains and carriages which made one realize how much work was falling on the railway officials and employés. In our train were fifty Natal Naval Volunteers under Lieutenants Anderton and Chiazzari. I was much struck with their good appearance and their silent work in stowing their gear in the train, and I realized their worth all the more when they joined up later on with our Brigade; all staid, oldish men, full of go and well dressed, while their officers were very capable, with a complete knowledge of the country.

We reached Frere Station on the morning of the 10th, passing the sad sight of the Frere railway bridge completely wrecked by the Boers. I walked out to the camp and had never seen such a fine sight before; rows and rows of tents stretching for miles, and an army of about 20,000 men. I found our electric search-light party at the station waiting to go on, and I was thankful to get a breakfast with them. Eventually our train moved on to the camp of the Naval batteries, about 2-½ miles due north of Frere, and I at once marched up with the Natal Naval Volunteers, reported myself to Captain Jones, and joined my guns, finding all the rest of the Naval officers here, viz.: Captain Jones, Commander Limpus, and Lieutenants Ogilvy, Melville, Richards, Deas, Hunt, and Wilde, with half a dozen "Mids" of the Terrible. In camp were two 4.7 guns on the new field mounting, one battery of eight 12-pounders, and another of four 12-pounder quick-firers.

(p. 014) On Sunday afternoon (10th December) an impressive Church service was held in the open, with ourselves forming the right face of the square along with Hart's Irish Brigade. In the course of next day (11th) I rode up to see James' battery on the kopje to our front defending the camp, and got my first glimpse of Colenso and the country around, some ten miles off. I found that James's guns had very mobile limbers which he had built at Maritzburg, very different to our cumbersome wagons with guns tied up astern. In the afternoon Melville and I had tea with General Hart who was very agreeable and kind, and said he knew my father, and my aunt, Lady Brind, very well.

In the evening orders suddenly came for Limpus' battery of 4.7's, my two 12-pounders, and Richards' four 12-pounders to advance the next morning (12th) at 4 a.m. to Chieveley, some seven miles from the Boer lines; and here again I was in luck's way as being one of the fortunates ordered to the front. All was now bustle and hurry to get away, and eventually the line of Naval guns, some two miles long with ammunition and baggage wagons, moved out in the gray of morning over the hills, with an escort of Irish Fusiliers, who looked very smart, "wearin' of the green" in their helmets.

Photo by Middlebrook, Durban.

Naval Brigade pitching camp at Frere, Dec. 1899.

We reached Chieveley at 8 p.m. (12th), after a long, dusty march, and got into position next morning on a small kopje about two miles to its front, called afterwards "Gun Hill." Guns were unlimbered and shell pits dug, while the wagons were all placed under cover; we received orders on arrival for immediate action, and at 9.30 a.m. we commenced shelling the enemy at a range of 9,500 yards. The 4.7 guns on the right fired the first shot, my two 12-pounders followed quickly, and a desultory shell fire went on for some hours. At my position we dug pits (p. 015) for the gun trails in order to get a greater elevation, and we plumped one or two shots on the trenches near the Colenso Bridge. The shooting of the 4.7's, with their telescopic sights and easy ranging, was beautiful; shell after shell, many of them lyddite, burst in the Boer trenches, and we soon saw streams of Boer wagons trekking up the valley beyond, while at the same time one of the Boer camps, 10,000 yards off, was completely demolished.

All this time our Biograph friends from home were gaily taking views of us, and they took two of myself and my guns while firing. Of course, the anxious officers of batteries had to lay the guns personally at this early stage, and every shot was a difficult matter, as at the extreme range we were firing, with the lengthening pieces on, the sighting was rather guesswork, and we had to judge mainly by the explosion at a distance of five and a half miles. We were all done up after our exertions under a broiling sun, and hence were not used any more that day (12th). Behind us we saw miles of troops and transport on the march onwards, which gave us the idea, and also probably the Boers, that Buller was planning a forward attack; and indeed, late at night on the 13th, the 4.7 Battery was told to move on to a kopje two miles in advance; my own guns, with the Irish Fusiliers being left to protect the ground on which we were then camped.

Orders came shortly afterwards for a general advance to the Tugela, and Captain Jones told me that I had been given the rear and left to defend from all flank attacks, and that I was to move on at daybreak of the 15th to an advanced kopje and place myself under Colonel Reeves of the Irish Fusiliers. All was now excitement; the first great fight was at length to come off and our fellows were full of confidence.

At 2 a.m., pitch dark, after a lot of hard work to get (p. 016) our guns ready, we struck camp; up rode Colonel Reeves with his regiment and threw out an advanced guard, and out we tramped and crossed the railway. Here we found all the field guns and Infantry on the move, and had great difficulty in getting on; but at last, at 5 a.m., we reached the desired kopje where I had been sent on to select gun positions. Before us stretched the battlefield for four miles to Colenso and the river; the Boers across the Tugela occupied an enormously strong position flanked by hills, all their trenches were absolutely hidden, and gun positions seemed to be everywhere. The iron bridge of Colenso was plainly visible through my telescope and was intact, and to all intents and purposes there was not a soul anywhere in sight to oppose our advance.

The Naval Battery of 4.7 and the 12-pounders under Captain Jones quickly got into position in front of us, and on all sides we saw our troops being thrown forward in extended order, forming a front of about four miles, with Cavalry thrown out on the flanks and field batteries galloping up the valley to get into range at 4,000 yards. All was dead silence till about 5.30 a.m., when the Naval guns commenced a heavy shell fire on the Boer positions. It was a fine sight; shell after shell poured in for an hour on the Boer trenches at a range of 5,000 yards, and all was soon one mass of smoke and flame. Not a sound came in reply till our troops reached the river bank, when the most terrific rifle fire I have ever heard of, or thought of, in my life, was opened from the Boer rifle pits and trenches on the river bank which had completely entrapped our men. Colonel Long, in command of the Artillery on the right of the line, unwittingly or by order, led his batteries in close intervals to within easy rifle range of those pits, when suddenly came this hail of bullets, which in a few minutes completely wrecked two (p. 017) field batteries (the 14th and 66th Batteries), killed their horses and a large number of the men, and threw four of the Naval 12-pounders under Ogilvy into confusion, although he was fortunately able to bring the guns safely out of action in a most gallant manner, with the loss of a few men wounded and thirty-seven oxen.

Many brave deeds were done here. Schofield, Congreve, Roberts, Reed, and others of the R.A. specially distinguished themselves by galloping-in fresh teams or using the only horses left in the two batteries, and bringing two guns out of action. With others at this spot poor Roberts met a heroic death and Colonel Long was badly wounded.

The firing all along the river bank was now frightful; shells from well-concealed Boer batteries played continuously upon our troops; the sun was also fearfully hot without a breath of air; and about 9 a.m. we noticed a sort of retiring movement on the left and centre of our position, and saw men straggling away to the rear by ones and twos completely done up, and many of them wounded. A field battery on the left had a hot time of it just at this moment and drew out of action for a breather quite close to our guns. I myself saw a dozen shells from the Boers go clean through their ranks, although, happily, they did not burst and did but little injury. Our troops were admirably steady throughout this hot shell fire.

Our Naval guns on Gun Hill, at about 5,000 yards range, were hard at it all this time trying to silence the Boer guns, and the lyddite shells appeared to do great damage; but the enemy never really got their range in return, and many of their shells pitched just in front of my own guns with a whiz and a dust which did us no harm. A little 1-pounder Maxim annoyed us greatly (p. 018) with its cross fire, like a buzzing wasp; it was fired from some trees in Colenso village, and enfiladed our Infantry in the supporting line, which was in extended order; but it did not do much damage so far as I could see, although it was cleverly shifted about and seemed to be impossible to silence.

By 11 a.m. (15th) we saw that our left attack was a failure; exhausted men of the Connaughts and Borderers poured in saying that their regiments had been cut up; and, indeed, many of their officers and men were shot and many drowned, in gallant attempts to cross the Tugela. Soon the ground was a mass of ambulance wagons, and stretcher parties bringing in the wounded; and a mournful sight, indeed, it was! The centre attack also failed, our men retiring quite slowly and in good order.

On the right, where the object of the advance was to carry a hill called Hlangwane, which was afterwards recognised to be the key of the whole position, our men, owing to want of numbers, could make but a feeble attack and were unable, unsupported, to pass the rifle pits which had been dug all along the valley in front of the hill. The Cavalry were, of course, of no use behind a failing Infantry attack with a river in front of them, and although extended to either flank it never got a chance to strike.

At 1 p.m. all firing ceased, except an intermittent fusillade by the Boers on our ambulance tents till they saw the red cross, when this ceased; the troops were all retired in mass to their original positions, and I myself had to clear out my guns as best I could to our old camping ground in the rear. To crown all, it came on to rain heavily about 5 p.m. by which we all got a good wetting. On our march back I had a few minutes of interesting talk with General Barton.

(p. 019) For many days all sorts of rumours flew about as to our losses at Colenso, which we afterwards found to be ten guns captured, fifty officers and 852 rank and file killed and wounded, and twenty-one officers and 207 N.C.O.'s and men missing and prisoners, a sad and unexpected end to our day's operations. An armistice to bury the dead was asked for by our people, and agreed to, but I do not believe that the Boer losses were at all heavy; and I am persuaded that if instead of the insufficient heavy batteries at Colenso, we could have had at the front, say two more batteries of 4.7 guns and two batteries of six 6" Q.-F., the Colenso disaster might never have happened. Against the fire of such guns, for say a week, moved up properly to within effective range, with reconnaissances carefully made and with an Infantry attack well pushed home in the end, I do not think that the Boers could or would have stayed in their positions; and I am confirmed in this opinion by a good many after experiences.

Saturday, 16th December.—Had a peaceful night and slept well, all being very much exhausted by the previous day's fighting and hot sun; we were kept very busy marking out ground for the Naval batteries which were all massed once more on our old camping ground.

Sunday, 17th December.—Commenced shelling Colenso Bridge at noon with a view to destroy it; but after a few rounds the order was cancelled and we again returned to camp.

Monday, 18th December.—Stood to arms at 4 a.m., then went to general quarters for action, when the 4.7 guns opened fire at daylight on Colenso Bridge for about two hours with lyddite, at a range of 7,300 yards. Lieutenant Hunt, on the left, struck one of the piers with a shell and took the roof off a small house close by; otherwise not (p. 020) much harm was done. It was a frightfully hot and depressing day with a wind like air from a furnace; and, bad luck to it, directly the sun was down at 5 p.m. a heavy dust storm came on which covered everything in a moment with black filthy dust, followed by vivid lightning and drenching rain which was quite a treat to us dried-up beings. I myself succeeded in catching a tubful of water which ensured me a good wash and a refreshing sleep for the night.

Tuesday, 19th December.—A cool nice morning and all the men in good spirits. At 8 a.m. the 4.7 guns opened fire again on Colenso Bridge. Lieutenant England's gun—the right 4.7 gun—knocked the bridge away; a very lucky and good shot, at which, needless to say, Sir F. Clery was very pleased.

Wednesday, 20th December.—Again a nice and cool day. In the evening I fired my 12-pounders at trees and villages to the left of Fort Wylie; the 4.7 gun, manned by the Natal Naval Volunteers, also did good work. We are now living like fighting-cocks, as the field canteen is open, with many delicacies, about half-a-mile to our rear. We also received unexpectedly to-day, with acclamation, lots of letters and English papers.

Thursday, 21st December.—Stood to arms at 4 a.m. and commenced firing about 6 a.m., in a very good light; my own guns were directed on the rifle pits 8,500 to 9,000 yards away, on the other side of the Tugela River. At this range the ammunition carries badly and the guns shoot indifferently. I put some common shells, however, into the enemy's rifle pits, but we are all getting tired of this sort of desultory firing and existence.

Saturday, 23d December.—About 8.30 a.m. the Commander-in-Chief and Sir F. Clery and Staff, accompanied by the foreign attachés, rode up to our guns and stayed (p. 021) for an hour sketching the hills on the right of Colenso, which I presume is now our objective. Mr. Escombe, late Premier of Natal, was also up with us all day watching our firing. Captain Jones also came to ask me to represent the Naval Brigade on the Sports Committee for Christmas Day; so I went down to General Barton's tent, met Colonel Bethune, Captain Nicholson, and others, and we arranged a good programme between us.

Sunday, 24th December.—No firing to-day. Church Parade at 8 a.m., when we brigaded with the Irish Brigade. A very large stock of beer, cakes, pine-apples, and other good things arrived in camp for the Natal Naval Volunteers; they gave a good share to our fellows who were very pleased, having none, and all are now busy preparing their plum-puddings for Christmas Day.

Christmas Day, 25th December.—We stood to arms at 4 a.m., but orders came for the guns not to fire. I was up at 5.30 a.m. to take my Sports party down to camp for the Brigade events. Our men won the Brigade Tug-of-war right out, and got great fun out of the wrestling on horseback on huge Artillery steeds, so that we came back to camp very elated. At 3 p.m. we marched down again for the finals in Sports; our fellows rigged up an Oom Paul and a Naval gent on a gun limber; this we dragged all round the camps and created quite a furore. The heat and dust were awful in the sports, but we pulled them off on the whole successfully, and all came back to camp tired out. I had my Christmas dinner with the Irish Fusiliers, who had drawn out an amusing menu of Whisky Powerful, Champagne Terrible, Cutlets à l'Oom Paul, and so on. I thought much of my people and friends at home, and was glad enough to get to bed without the prospect of any night alarm or attack, after such a big dinner.[Back to Contents]

Life in Camp and Bombardment of the Boer lines at Colenso—General Buller moves his army, and by a flank march seizes "Bridle Drift" over the Tugela—The heavy Naval and Royal Artillery guns are placed in position—Sir Charles Warren crosses the Tugela with the 5th Division, and commences his flank attack.

Tuesday, 26th December.—We stood to arms at 4 a.m., and shelled the Boer camp and trenches for two hours during the day. The Biograph people, who are still with us, took a scene of the Tug-of-war, our Oom Paul, and then a tableau of the hanging of Kruger! Captain Jones came to give the Sports prizes away, which greatly pleased our men; he told me afterwards that he had selected my two 12-pounders and the 4.7 guns to advance with him when ordered, at which needless to say I was very much gratified. Another heavy dust storm, followed by thunder and heavy rain. On the few following days we went through our usual cannonading, following a new practice of firing at night by laying our guns just at dusk, placing marks to run the wheels on, and using clinometers for elevation at the proper moment. All our shells burst, and, we were told afterwards, with effect, greatly disturbing sleeping Boers in Kaffir kraals at Colenso.

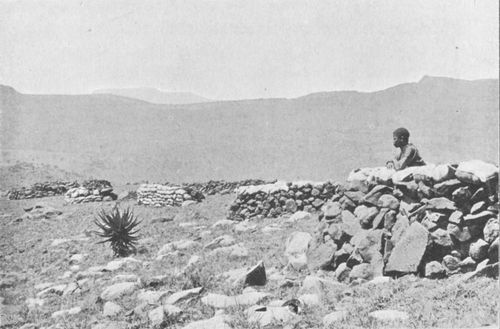

Photo by Middlebrook, Durban.

Naval Guns in Action at Colenso.

Friday, 29th December.—Again more firing at a new work that the Boers were making, apparently for guns. Seeing an officer on a white horse directing them, we banged at them all and cleared them off. Again a heavy (p. 023) storm, but sunshine reached us during it in the shape of boots and great-coats from Frere, for which we were all grateful. The following day was wet and cold. I went to camp to try and buy poor young Roberts' pony, but the price was too high for me. Lord Dundonald came to arrange with Captain Jones a sham night attack on the Boer lines which happily did not come off as it was a horrible wet night.

New Year's Day, 1900.—At midnight of the old year my middy, Whyte, and myself turned out, struck sixteen bells quietly on a 4.7 brass case, and had a fine bowl of punch, with slices of pine-apple in it, which we shared with our men on watch, wishing them all a happy New Year. Good old 1899! Well, it is past and gone, but it brought me many blessings, and perhaps more to come. We gave the Boers some 4.7 liver pills, which we hope did them good. All our men are well and cheery, but our Commander has a touch of fever, so that I am left in executive charge of the men and camp. Winston Churchill came up to look at our firing. During the next few days, in addition to our firing, our 12-pounder crews started to make mantlets for the armoured train; a very big job indeed, as they had to cover the whole of the engine and tender, afterwards called "Hairy Mary," as well as the several trucks. The officer in command congratulated our men on their work under the indefatigable Baldwin, chief gunner's mate of the Terrible, who was in charge. The military also started entrenchments and gun pits on the hill, which we call "Liars Kopje"; at dusk they came to a standstill over some big boulders that the General asked us to remove, which was a compliment to the powers of the Navy. We soon made short work of the boulders, much to the General's satisfaction, and got on fast with the mantlets. Still heavy rain at night.

(p. 024) Thursday, 4th January.—Again more firing. My own 12-pounder crews and those of Richards' guns hard at the mantlets for the armoured train, and doing the job very well. On the 2nd, Lord Dundonald rode up and arranged an attack on a red house 6,000 yards from us and supposed to contain some of the enemy, but we found nobody at home. We were all glad to receive letters from home to-day. I was busy all day shifting one of my 12-pounder gun wheels for a new and stronger pair of skeleton iron ones, just sent from Durban, in view of a feint to the front with the object of drawing the Boers away from Ladysmith.

Saturday, 6th January.—This feint was made and we had no casualties. Poor Ladysmith! Our men there are hard pressed and must have a bad time; very heavy firing all day, and we heard by heliograph that the Boers had made a heavy attack in three places, although, happily, repulsed with heavy loss (including Lord Ava) to ourselves. We have Bennet Burleigh, Winston Churchill, Hubert of The Times, and many others, constantly on Gun Hill looking at our firing.

Sunday, 7th January.—From Sir George White's signals we realize what a close shave they had yesterday in Ladysmith. A nice cool day and no firing; in fact, a day of rest. We attended Church Parade at 6 p.m. with the 2nd and 6th Brigades. The Boers are as usual in the trenches working hard, while our time just now is spent in rain and constant calls to arms.

Wednesday, 10th January.—A move at last, and I received orders to join General Hildyard's Brigade with my two guns, while the others were attached to other Columns. We were all hard at work to-day loading up wagons, and I was busy copying a large map of the country which our Commander lent me. In the evening (p. 025) General Hildyard sent for me on business, and I sat down with him and his Staff to dinner, including Prince Christian, Captain Gogarty (Brigade Major), and Lieutenant Blair, A.D.C. General Hildyard was very kind, and said he was glad I was to go with him; and the next morning I moved off my guns at daylight, and arrived at the rendezvous by the hour named. It was a fine morning, although the wet and soft ground gave me doubts about getting our guns across country. But off we started; the Cavalry scouting ahead, then the East Surreys, Queen's, and Devons, and the 7th Battery Field Artillery, followed by my guns escorted by the West Yorks. About a mile from Chieveley we had to cross a drift in which my wagons went in mud up to the tops of the wheels, and one gun got upset, which I got right again with the assistance of three teams of oxen and a party of the West Yorks. It was indeed a job, because the ground was like a marsh, and our ammunition wagons, with three tons' weight on them, were half the time sunk up to the axles; but we all smiled and looked pleased while everybody helped, and in six hours we were clear and on the road. We were all done up with the shouting and hot sun, and the General ordered us a two hours' rest while he took the Brigade on to Pretorius' farm, which we ourselves reached at 6 p.m., crossing another bad drift on the way. The men were absolutely done up, and we were glad to arrive and find ourselves in a fine grassy camp with plenty of water. General Hildyard called me up and said he was pleased with the splendid work we had put through that day. On our left were miles of baggage wagons of various Brigades going into camp along a road further west of us.

Thursday, 11th January.—Shifted my ammunition to fifty rounds per gun to lighten the wagons, and moved (p. 026) off at 5 a.m., passing General Hildyard who was looking on at the foot of the camp. We marched with the whole force to Dorn Kop Nek and then halted; the General and others, including myself, riding up to a high kopje to examine the Boer position on the Tugela at about 8,800 yards off. Prince Christian Victor came and sat on a rock by me and had a good look at the position through my telescope which he borrowed. The General ordered one of my guns up this kopje, and we brought it up with a team of oxen and fifty men on drag ropes to steady her. It was an awful climb, and the ground was strewn with boulders; the poor gun upset once, but we got it up at last into position on a beautiful grass plateau on top with a clear view of the Boer positions. The Queen's Regiment, who were our escort this morning, carried fifty rounds of ammunition up the kopje for me, and I shall always remember how on all occasions we received the greatest assistance from the Queen's and West Yorks. The General pushed on with the R.A. and the rest of the troops and reconnoitred the enemy from the next kopje. Eventually we were all ordered back to camp, and I had a great job in getting my guns down the hill again. I think it was worse than going up.

Friday, 12th January.—Prince Christian (Acting Brigade Major) and I had a short talk together; we touched on a scheme of mine for making light limbers for our guns. In the afternoon I rode out to General Clery's camp, three miles to the west, to see our Naval guns, but found they had been pushed on with Lord Dundonald's Cavalry to hold ground leading to Potgieter's Drift. I dined with Captain Reed of the 7th Battery, R.A., who knew my R.A. brother well in the 87th Battery. I found I had met him last year at the Grand National, and it is quite curious that I meet out here everyone that I ever knew.

(p. 027) Saturday, 13th January.—Sent Whyte, my middy, a nice fellow and useful to me, over to Frere on a horse to see about many things I wanted for the battery, and at 9.30 a.m. read out to my men on parade General Buller's address to the troops, dated 12th January, 1900. This is the text of it. "The Field Force is now advancing to the relief of Ladysmith where, surrounded by superior forces, our comrades have gallantly defended themselves for the last ten weeks. The General commanding knows that everyone in the force will feel as he does; we must be successful. We shall be stoutly opposed by a clever unscrupulous enemy; let no man allow himself to be deceived by them. If a white flag is displayed it means nothing, unless the force who display it halt, throw down their arms, and throw up their hands. If they get a chance the enemy will try and mislead us by false words of command and false bugle calls; everyone must guard against being deceived by such conduct. Above all, if any are even surprised by a sudden volley at close quarters, let there be no hesitation; do not turn from it but rush at it. That is the road to victory and safety. A retreat is fatal. The one thing the enemy cannot stand is our being at close quarters with them. We are fighting for the health and safety of comrades; we are fighting in defence of the flag against an enemy who has forced war on us from the worst and lowest motives, by treachery, conspiracy, and deceit. Let us bear ourselves as the cause deserves."

Sunday, 14th January.—Church Parade at 6 a.m. with the West Yorks, Devons, East Surreys, and Queen's. About 8 a.m. a wagon and team crawled up to our camp; this turned out to be the light trolley I had sent for and which Lieutenant Melville had kindly hurried forward from Frere. I was awfully pleased to see it as our load (p. 028) before was absurdly heavy. The General was also quite glad to see and hear of the new trolley. At 2 p.m. in came my new horse from Frere, and a bag of excellent saddlery; the horse was in an awful state; he had apparently bolted on getting out of the train at Frere and injured two Kaffirs who tried to stop him; then the Cavalry chased him and caught him ten miles from Frere towards the Drakensberg mountains. The poor animal was very much done up and I found him afterwards a fine willing beast.

Monday, 15th January.—Struck tents and limbered up ready to march at 6 a.m., and moved off in rear of the 7th Battery R.A.; they have been very good to us all along, shoeing ponies and giving us water. A nice cool morning, and all in good spirits. We soon passed the first drift across a spruit about four feet deep; my guns just grazed the top of the water but luckily we had taken care to stuff up the muzzles with straw. The bullocks had a very hard pull, more especially as my men were obliged to ride across the gun wagons. The General looked on and we got on very well; all working, laughing, joking, and helping, especially our good friends the Tommies. We marched across a green veldt, with the usual kopjes at intervals; and after about eight miles passed through the camp of the Somersets who came out to see us go by and were very cordial; about a mile further on we crossed the Little Tugela Bridge, and had a very heavy pull shortly afterwards across our last drift, which was a bad one. Countless bullock wagons, mule carts, and transport of all descriptions of the Clery, Hart, and Coke Brigades extended for miles along the two roads leading to our advanced position. We were delighted to see a river at last, and men and horses had a fine drink. After a meal in pelting rain I rode on to report to General (p. 029) Hildyard, and had tea with him and his staff, including Prince Christian; they are all always very nice to me.

Tuesday, 16th January.—A stream of transport wagons is still crossing the drift this morning, and the Drakensberg mountains look very grand and beautiful in this clear air. We drew fresh meat to-day in our provisions. What a surprise and a treat! The Boer position on the Big Tugela lies six miles off; and here Dundonald and his Cavalry, with one 4.7 gun, are watching the enemy who are working day and night at their trenches. About noon, Colonel Hamilton, of General Clery's Staff, rode into our camp and told me that orders had come for my guns to proceed at once into position with Lieutenant Ogilvy's battery. He asked me how long I should be. I said two hours to collect oxen and pack up, and so we were ordered to march at 1.45 p.m. I was very sorry to be suddenly shifted again out of General Hildyard's Brigade, and I asked him to intervene if we were again detached, which he promised to do. We marched up to time, and got to camp about 5 p.m., escorted by a troop of the Royal Dragoons. As usual, it came on to pour; everything was quickly a sea of mud, and the men in their black great-coats, marching along with the horses and guns mixed up with them, reminded one strongly of scenes in pictures of Napoleon's wars. We found that we had to move on in an hour's time with Ogilvy's guns to a plateau further on. I rode out to see Captain Jones and the 4.7's in position, a grand one on top of a very steep cliff kopje some 1,000 feet above the Tugela; the plateau selected for our 12-pounder guns was some 600 feet lower down and 2,000 yards nearer the enemy. We had a tough march out, and did not get to our plateau till 11.30 p.m. I had a snack and gave the others all I could, and the great Maconochie ration and beer will never be forgotten, that night at any (p. 030) rate. I myself turned in to sleep under a trolley, just as I was, and very tired we all were after our hard day.

Wednesday, 17th January.—Out at daybreak to bring our 12-pounders into action. The drift over the Tugela, about half-a-mile to our right front, had been seized by Dundonald, and a howitzer battery had been pushed across some 2,000 yards nearer than ourselves, supported by the King's Royal Rifles, the Scottish Rifles, the Durhams, and the Borderers; to our right front was also to be seen the Engineer balloon, under Captain Phillips, R.E., being filled with gas. About 10 a.m. a message came up from General Lyttelton to bring four guns into action on our left flank, which I did at once under Ogilvy's orders, and a little later Captain Jones rode down to us and told us to support Sir Charles Warren's advance to our left across the river. I opened fire with my right gun, and got the range in two shots, after which the whole four guns opened fire and burst several shells over the correct spot. I heard that Sir Charles Warren signalled in the evening to say we had by our fire put two Boer guns out of action and made them retire, and we were all delighted. His force was plainly to be seen occupying the ridge about 6,000 yards to our left front. The firing of the howitzer battery was very fine to-day; also our 4.7 guns did well. The howitzers landed salvos of their shells, six at a time, all bursting within fifty yards of one another and right on the Boer works on the sky-line, where our Naval 4.7's were also working away at a greater distance off. As no tents were allowed us I again slept in my clothes under a wagon.

Thursday, 18th January.—A beautiful morning, and we were all up at daybreak commencing a slow firing at the Boer trenches, and many fine shots were made; the howitzers, during the afternoon, pushed on about 500 yards (p. 031) nearer the enemy under cover of three small kopjes. Looking at the position from our plateau one wondered how the Boers could have allowed us to get here and cross the river unopposed. If we had been resisted we must have had an awful job, both here and at the Little Tugela. All our army experts are surprised, and we think we must have caught them on the hop, as they don't reply to our artillery fire. Still, they are opposing Sir Charles Warren's advance as well as they can, and very hard fighting is going on to our left, although we only hear the shots and see the flashes of our guns, with volleys of musketry, while the enemy are hidden behind a high hill called Spion Kop. The panorama before us is magnificent; and the Tugela, our bugbear at Colenso, lies before us, beautiful, meandering, and apparently conquered. At 5 p.m. a demonstration in force against the trenches at Brakfontein was ordered, and we commenced rapid firing with eight guns, making very fine practice and sending off some 600 shells to cover our Infantry advance which was pushed on right up to the foot of the Boer kopjes and about 1,500 yards from their trenches. The Engineer balloon floated proudly in the air watching the operations. We retired at dusk, the object being to draw the Boers to their trenches and to relieve Sir Charles Warren's left attack which was advancing very slowly. We laid our guns at dusk and fired them every half-hour during the night.

Friday, 19th January.—We began firing again at daybreak, General Lyttelton and Staff looking on. They told us that our guns had shot very well the evening before. A very hot day. The fighting on the left seems to be heavier and more distant, and all sorts of rumours are current as to demonstrations and successes.

Saturday, 20th January.—Firing as usual. We hear again heavy firing on the left. About 3 p.m. our balloon (p. 032) went right out over the Boer trenches, while our Infantry attacked in force on the right and demonstrated in front in extended order; we kept up our firing, while James's guns which had been pushed across the river took the right hills, and with the howitzers put a Boer Pom-pom out of action. The balloon did well; it was fired at by the Boers with Maxims and rifles, and was hit in several places; in fact, Captain Phillips, in charge of it, had his forehead grazed by a bullet. During the afternoon my right gun trail smashed up and I had to employ all the talent near at hand to repair it. With a baulk of timber from the Royal Engineers we finished it, and at the same time shifted the wheels to a beautiful pair of gaudily-painted iron ones from Durban. I now call it the "Circus Gun."

Sunday, 21st January.—A very hot day. The armourers and carpenters still hard at work on my gun trail. Orders came for two guns to advance across the river, and Ogilvy told me off for that honour. By dint of hard work my right gun was finished by 11 a.m., and I inspanned and went off two hours afterwards. A very steep hill was the only thing to conquer going down, and we successfully crossed the Tugela in a Boer punt—guns, oxen, and my horse. We got the guns up to our new position by 6 p.m., and found ourselves about 4,200 yards from the enemy's trenches, with James's guns on our right. We had a cordial meeting with the Scottish Rifles; they had been a week in their clothes, with no tents or baggage, so I put up one of our tarpaulins for their mess tent and we enjoyed a real good dinner. At 9 p.m. up came Ogilvy to our position, to my surprise, as he had received sudden orders to bring the rest of the guns on across the river; the road and river must have been very nasty in the dark, but Ogilvy is a clever and capable fellow, who is always determined, sees no difficulties, and invents none.[Back to Contents]

Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz—General Buller withdraws the troops and moves once more on Colenso—We hold Springfield Bridge—Buller's successful attack on Hussar Hill, Hlangwane, and Monte Christo—Relief of Kimberley.

Monday, 22nd January.—We placed the battery of six guns at daybreak in a kloof between two kopjes, in a half-moon formation, commanding the old position near Spion Kop, at about 4,500 yards, mine being in the centre. I was in charge all day and fired shots at intervals. The wind was too high for balloon reconnoitring. My first shot, a shrapnel, at the left part of Spion Kop, disabled twenty of the enemy digging in the trenches, so we were afterwards told by native scouts; and we were praised by those looking on for our accurate firing. We had now our telescopic sights on the guns, and very good ones on the whole they were, although we found the cross wires too thick and therefore hid an object such as a trench which at long range looks no more than a line. I found my deflection by a spirit-level on the trail, to test the inclination of the wheels one way or the other. There was very heavy fighting to-day on our left. Sir Charles Warren is in fact forcing his way on, and we hear reports of 400 of our fellows being killed and wounded, and the Boer trenches being taken by bayonet charges. So far as we know, General Buller's object is to outflank the (p. 034) Boers on the left, and then when Sir Charles Warren has done this, to attack in front and cut them off.

Tuesday, 23rd January.—Another day, alas, red with the blood of our poor fellows. Sir Charles Warren continued his operations at 1 p.m., and from then till midnight the fight raged. Musketry and guns booming all round, the Maxims and Vickers 1-pounder guns, being specially noticeable. At daylight we ourselves stood to guns and concentrated our fire on the Boer trenches and positions to the front and right, in order to draw the enemy away from Warren's force; while the Infantry with us (Rifle Brigade, King's Royal Rifles, Durhams and Scottish Rifles) made a demonstration in force to within 2,000 yards of the main trenches under cover of our fire. The attack under Warren got closer and closer each hour, and we could watch our fellows, apparently the Lancashire Brigade, storming the top of Spion Kop, in which, I afterwards heard, my father's old regiment (the Lancashire Fusiliers) bore a splendid part. Meanwhile our own attack on the Brakfontein trenches was withdrawn, and we brought our guns into action on the left to assist the operations on Spion Kop but soon had to desist for fear of hitting our own men. The fight raged all day and was apparently going well for us. At 4 p.m. came a message from General Buller ordering the King's Royal Rifles and Scottish Rifles to storm Spion Kop from our side, which they did, starting from our guns and making a prodigious climb right gallantly in a blazing heat and suffering a considerable loss. Poor Major Strong, with whom I had just breakfasted, was one of the wounded and, to my great sorrow, died of his wound. Our guns meanwhile were searching all the valleys and positions along the eastern slopes of Spion Kop; but it was all unavailing, as we were apparently forced to retire after heavy losses during the (p. 035) night. We ourselves were all dead beat, but had to be up all night with search-lights working on the Boer main position; but what of poor Warren's force after five days' constant marching and fighting!

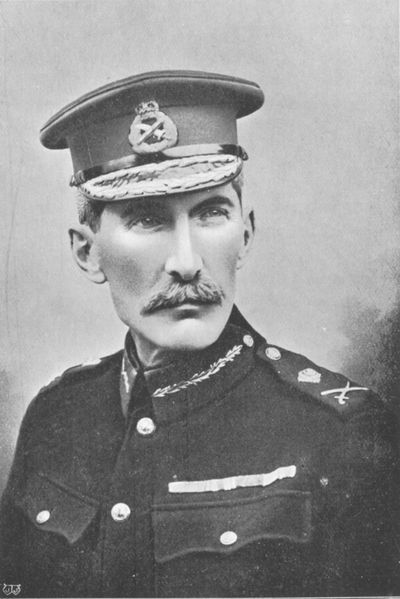

Lieut. Burne's Guns firing at Spion Kop.

4.7 Emplaced on Hlangwane.

Wednesday, 24th January.—No more firing and many rumours; but at last it was a great surprise and blow to us to hear a confirmation of the report that Warren's right had been forced to abandon Spion Kop during the night, and to be also told that we ourselves were to go back to our old plateau in the rear. I had my guns dragged up to Criticism Kop with great labour by eighty of the Durhams, who are now our escort; and with the Rifle Brigade we hold the three advanced hills here, while Ogilvy has been moved back across the river. We hear of a loss of some 1,600 men, the poor 2nd Bn. of the Lancashire Fusiliers specially suffering heavily;[2] there is therefore great depression among all here, a cessation of fire being ordered, and nothing in front of us except ambulances. Our mail came in during the evening and I was very pleased to get letters from Admiral and Mrs. Douglas. We feared a night attack, so had everything ready for the fray. I was on the watch all night with Whyte, but our search-light kept off the danger and all remained quiet.

Thursday, 25th January.—A quiet day, the Boers and our own ambulance parties burying the dead on Spion Kop. And so went the next few days, we shelling the Boers at intervals although sparingly. Rumour says that General Buller is confident of beating the Boers in one more try, and is shortly going to try it. May the key fit the (p. 036) lock this time! He seems determined, and we all hope he will be at last successful.

Monday, 29th January.—We are firing as usual. Colonel Northcote of the Rifle Brigade came over from his kopje to see me, and I proposed the construction of two rifle-proof gun pits on the river bank, to which he agreed. A very hot day and raining heavily at night.

Wednesday, 31st January.—We have orders to watch carefully the right of the Boer position. I let Mr. Whyte fire a dozen shells, which he did very well, and I finished my gun pits, and very good ones they are. Just at dark up came an officer from General Buller with an order that we were to retire our Naval guns at daybreak to the plateau, which we had to do much to our disappointment, moving off at daybreak next morning and taking the guns in a punt across the river. I learnt to my great sorrow that poor Vertue of the Buffs, my friend of Ceylon days when he was an A.D.C. to the General there, was killed at Spion Kop, and I am much depressed as I liked and admired him immensely.

Friday, 2nd February.—The Boers are busy burying their dead on Spion Kop under a flag of truce, so we have a quiet day and no firing.

Saturday, 3rd February.—The troops are all again on the move; no less than nine field batteries are pushed over the river with some Battalions of Infantry, while Boers are on the sky-line at all points watching us.

Sunday, 4th February.—Sir Charles Warren arrived on our gun plateau with his Staff, and pitched his camp close to my guns. I found that Sir Charles knew my father, and he told me that the Boers had had a severe knock at Spion Kop and were ready to run on seeing British bayonets; he spoke of his plans for the morrow and of our prospective share in them. My share is to be a good (p. 037) one, as I am to have an independent command and am so actually named in the general orders for battle. I went over the plan of battle carefully with Captain Jones, R.N., and our Commander, who thought Pontoon No. 3 was the weak spot.

Monday, 5th February.—A fateful day of battle. At daybreak we stood to our guns, but it was not till 6.30 a.m. that our Artillery, no less than seven batteries, advanced under cover of our fire. On the left were the 4.7 guns on Signal Hill; my two 12-pounders were on the gun plateau in the centre, and on the right, on Zwartz Kop, were six more of our 12-pounders under Ogilvy. The broad plan of attack was a feint on the left and then a determined right attack. This developed slowly; the Artillery and Infantry advanced, and we all shelled as hard as we could for some hours, when the Infantry laid down just outside effective rifle range from the Brakfontein trenches, and the Artillery, changing front to right, withdrew from the left, except one battery, to assist in the centre attack on Vaal Krantz. Our Naval guns went on shelling the left where the Boer guns were well under cover and were very cleverly worked. About 12 noon the Infantry withdrew from the left and it was evident that our feint had fully succeeded in its object, i.e., to get the enemy drawn down to their trenches and stuck there. The Artillery, after crossing No. 2 Pontoon, were drawn up in the centre shelling Vaal Krantz, while Lyttelton's Brigade was pushed forward to attack it and succeeded in reaching the south end of it. Our own firing on the left was incessant. I found afterwards that I had fired 250 rounds during the day, and I had many messages as to its direction and effect from Sir Charles Warren, and General Talbot-Coke, who was just behind us with his Staff. Little firing during the night. Very tired.

(p. 038) Tuesday, 6th February.—At it again at daylight, the Boers commencing from their 100 lb. 6" Creusot at 6,000 yards to the east of Zwartz Kop. I had suddenly got orders during the night from Sir Charles Warren to move my guns off the plateau and join Buller's force at daybreak at the east foot of Zwartz Kop, so I moved off at the time named, feeling very thankful that I had my extra oxen to do it. We had some miles to go, over a vile road, and on the way we passed the 7th Battery R.A. and some Cavalry and ambulances. All this, meeting us on a narrow and badly ordered road, delayed us so much that it was 8 a.m. before I was able to report my guns to the Commander-in-Chief, which I did personally; he turned round and said, rather pleased, "Oh, the Naval guns are come up," and, pointing me out the Boer 6" Creusot and a 3" gun enfilading our Artillery, he asked me if I could silence them; the 6" was at 6,500 yards and the 3" at 10,000 yards, so I replied, "Yes, the 6"," and by the General's order I brought my guns into action about 200 yards away from him and his Staff. As I was preparing to fire my right gun, bang came a 100 lb. shell right at it, striking the ground some twenty yards in front and digging a hole in the ground of about six feet long, covering us with dust, although happily the shell did not burst but jumped right over our heads. This was followed by a shrapnel which burst, but the pieces also went right over our heads. After hard pit digging, I tried for the 3" at 9,000 yards, with full lengthening pieces, with my left gun, but I could not range it; so we kept up a hot fire with both guns on the Boer Creusot, which was also being done by the two 5" guns in front of us and by our Naval battery on the top of Zwartz Kop. We silenced this gun from 8.30 a.m. to 5 p.m. when it again opened on us (with its huge puff of black powder showing up (p. 039) finely), but without doing us much harm. At 11 a.m. the Boers brought some field guns up at a gallop to Vaal Krantz, running them into dongas or pits about 6,000 yards away from us, and then sending shrapnel into our troops on the Kop and trying to have a duel with us; we quickly silenced them, however, as well as a Pom-pom in a donga about 4,000 yards off, and they beat a retreat over the sky-line. I here found my telescopic sight very useful for observing every movement while personally laying guns. The General sent me many messages by his Staff, and was pleased at our driving off the guns. As the day passed, the cannonade became fast and furious and our attack advanced but slowly; we silenced most of the Boer guns by 5 p.m. and slept that night as we stood. I had the Boer 100 lb. 6" shell (which had fallen close to us without bursting) carried up the hill to show the Commander-in-Chief and Staff; they were all interested but rather shy of it, but one of them took a photo. We picked up many fragments of shells which had fallen close to us during the day and from which all of us had narrow escapes, for we were in a warm corner. General Hildyard and Staff who were sitting close by us at one part of the day had a 100 lb. shell fired over them which just missed Prince Christian.

Wednesday, 7th February.—Dawn found us still fighting on this the last day of our attempt to relieve Ladysmith from this side; heavy firing commenced at daybreak, and we did our best to keep down the Boer fire, the 4.7 Naval gun on Signal Hill making fine practice. Meantime our troops now on Vaal Krantz, viz., Hildyard's East Surreys, Devons, and West Yorks, pushed the attack or held their trenches under heavy fire, while we were trying to silence the enemy's guns. By this time the long range of hills to the east of Brakfontein was all ablaze from our shells, (p. 040) and also one flank of Vaal Kop. All looked lurid and desolate, and at times the cannonading was terrific, the Boer 6" with its black powder vomiting smoke and affording an excellent mark. At 4 p.m. the Engineer balloon went up in our rear to reconnoitre, and brought down a disheartening report of unmasked Boer guns and positions which would enfilade our advance from here all the way to Ladysmith; so that after a Council of War the Commander-in-Chief decided to retire the troops; my orders from Colonel Parsons, R.A., being to make preparations to withdraw my two guns to Spearman's Kop as soon as the moon rose, and to cover the retirement. In fact, according to his words the Council of War decided that while we could get through to Ladysmith from here, we should be hemmed in afterwards owing to the new positions disclosed by Phillips' balloon report. It was just dusk; Infantry and Artillery were being hastily moved up to cover the retirement, and after loading up our ammunition off we ourselves went. My poor men were very done up after the constant marching, firing, and working ammunition of the last three days; we had, in fact, shot off no less than 679 rounds, and the sun was awful the whole time. The withdrawal was very well carried out in the dark; we ourselves followed the ammunition column, and the Field Artillery followed us. As the foot of Gun Hill was completely blocked I brought my guns out down by the Tugela, ready to cover the troops; and we slept as we stood, while a constant stream of Artillery, Infantry, and ambulances were struggling to get up the steep hill; indeed, it was a most memorable day and night. Poor Colonel Fitzgerald of the Durhams was carried past me in a stretcher about 5 p.m. shot in the chest with a Mauser. I had known him before when holding the kopjes over the river with his regiment; he insisted on talking to me and (p. 041) sat up to have a cup of tea, and I was glad to hear afterwards that he had eventually recovered. Our total casualties for the three days were about 350; our Infantry had done brilliantly; and, while we were all savage at having to withdraw, we were confident that the Commander-in-Chief knew best, and indeed it seems from information received later on that he did the right thing.

Thursday, 8th February.—At daylight the Boer 6" went on shelling us at 10,000 yards but did little damage, so I got up the hill about 9 a.m. after a hasty breakfast, and passing Sir Charles Warren's tent got into my old position on the plateau, finding the 7th Battery R.A. holding the hill close alongside. My men were quite done up, so that the temporary rest was acceptable, although we had to keep a sharp look-out, and twice silenced Boer guns firing on our Infantry at 6,500 yards from Spion Kop. At noon the kopjes in front were evacuated, our pontoon taken up, and the Boer punt sunk by gunpowder. So good-bye to the Tugela once more; all our positions gone and the Boers down again at the river. At dusk I got permission to withdraw my guns over the ridge on account of sniping, and it was well I did so as the Boers came very close to us during the night.

Friday, 9th February.—Got orders from the Commander-in-Chief to withdraw with others on to Springfield Bridge; we were almost the last guns off, and had a hot march of eight miles escorted by a party of the Imperial Light Infantry under Captain Champneys. How we did enjoy a bathe from the river bank, as well as our sleep that night! It was all quite heavenly.

Saturday, 10th February.—About 9 a.m. I was ordered by Colonel Burn-Murdoch of the Royal Dragoons to bring my guns up to his entrenched camp behind the (p. 042) bridge to assist in its defence. I had breakfast with him and he seemed very nice. He is now Brigadier-General and Camp Commandant, and we are left in defence here, to protect Buller's left flank, with "A" Battery Horse Artillery, the 2nd Dragoons and 13th Hussars, the Imperial Light Infantry, and the York and Lancasters. The rest of the troops had all gone to Chieveley. The day was very hot again, and I was very glad to give the men another rest, with fresh butter, milk, chickens, and fruit to be had, brought in by Kaffirs from neighbouring farms. Just think of it!

Sunday, 11th February.—Again very hot. About 7 a.m. there was a heavy rifle fire to the N.E.; our Cavalry pickets were in fact attacked, and as I saw Boers on the sky-line, I got leave to open fire, but did no damage, as the hill, we afterwards found out, was some eight miles off. So much for African lights and shades, which, after eight months' experience of them, are most deceptive. It turned out that our Cavalry pickets had been surprised by the Boers unmounted in a donga, and unluckily Lieutenant Pilkington and seven men were taken prisoners, and several men wounded—a bad affair.