Project Gutenberg's The Nursery, September 1873, Vol. XIV. No. 3, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Nursery, September 1873, Vol. XIV. No. 3 Author: Various Release Date: March 29, 2008 [EBook #24940] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NURSERY, SEPT. 1873, VOL.XIV NO.3 *** Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net Music by Linda Cantoni.

| IN PROSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| The Queer Things that happened to Nelly | 65 |

| The Six Ducks | 69 |

| The Bunch of Grapes | 71 |

| A True Story about a Dog | 73 |

| Pitcher-Plants and Monkey-Pots | 76 |

| Under the Cherry-Tree | 77 |

| Rambles in the Woods | 80 |

| What I Saw at the Seashore | 82 |

| Blossom and I | 85 |

| How Norman became an Artist | 87 |

| A Boot-Race under Difficulties | 89 |

| Pictures for Walter | 90 |

| The Fisherman's Children | 92 |

IN VERSE. | |

| PAGE. | |

| Rose's Song | 68 |

| A Little Tease | 75 |

| Sleeping in the Sunshine | 78 |

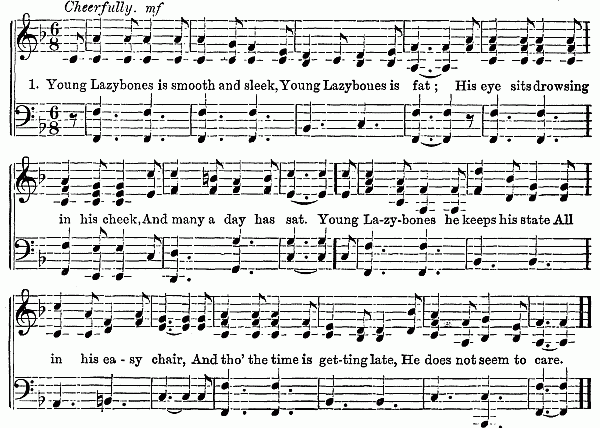

| Young Lazy-Bones (with music) | 96 |

THE QUEER THINGS THAT HAPPENED TO NELLY.

THE QUEER THINGS THAT HAPPENED TO NELLY.

No sooner had the thought passed through her mind, than, as she looked down on the closely-mown grass by the edge of the pond, she saw the queerest sight that child ever beheld.

A carriage, the body of which was made of the half of a large walnut-shell, brightly gilt, was moving along, dragged by six beetles with backs glistening with all the colors of the rainbow.

Seated in the carriage, and carrying a wand, was a young lady not larger than a child's little finger, but so beautiful that no humming-bird could equal her in beauty. She had the bluest of blue eyes, and yellow crinkled hair that shone like gold.

She stopped her team of beetles, and, standing upright, said to Nelly, "Listen to me. My name is Pitpat; and I am a fairy. I see how tired you are with work. Your father, though a good man, is a blacksmith; and there is often a smirch on his face when he stoops to kiss you. Your mother wears calico dresses, and doesn't fix her hair with false braids and waterfalls. Would you not like to be the daughter of a king and queen, and live in a palace?"

"Oh, yes, you beautiful Pitpat! I would like that ever so much!" exclaimed Nelly. "Then I should be a princess, and have nothing to do but amuse myself all day."[67]

"Take the end of my wand, and touch your eyes with it," said the little fairy.

Nelly obeyed; and in a moment, before she could wink, she found herself in a beautiful room, with mirrors reaching from the ceiling to the floor. By these she saw that she was no longer clad in an old dingy dress, nor were her feet bare; but she had on a beautiful skirt of light-blue velvet, and a bodice of the most costly lace, trimmed with ribbons; while diamonds were in her hair, and a pair of gold slippers on her feet.

Servants were in attendance on her, one of whom said, "May it please your Highness, his Majesty, your royal father, is coming." Nelly's heart fluttered. The door opened, and, preceded by two or three lackeys, a pompous old gentleman entered, clad in rich robes, a golden crown on his head, and no smirch on his face.

But, dear me, instead of catching her up in his arms, and calling her his own precious little Nelly, his Majesty simply gave her his hand to kiss, and passed on.

The queen followed in his steps. Her hair was done up in a tower of top-knots and waterfalls; and there was drapery enough on the back of her dress to astonish an upholsterer. Instead of calling Nelly "her darling," as Nelly's first mother used to do, the queen merely said, as she swept by, "Where are your manners, child?" for you must know that poor Nelly had forgotten to courtesy.

Nelly put her face in her hands, and began to cry. "Oh, you cruel Pitpat!" said she, "why did you tempt me? Oh! give me back my own dear mother in her calico dress, my own dear father with the smirch on his face, my doll Angelica, my black-and-white kitten Dainty, and my own dear, dear home beside the lovely pond where the air is so sweet and the bushes are so green."[68]

"Take the end of my wand again, and touch your eyes with it," said the voice of Pitpat. And there on the carpet, in her little gilded carriage, stood the fairy once more with her wand held out. Nelly seized it eagerly, and touched her eyes.

"Why, Dainty, what are you about?" said Nelly, as she felt the kitten's head against her arm; and then, opening her eyes, she started to find herself in the old wood-shed, seated with her back against the door, Angelica in her lap, and the soft breeze from the pond fanning her cheek and bosom. She looked at her feet. Ah! the golden slippers had disappeared. "Dear me! I must have been dreaming," said Nelly.

In the pond near Emily's house six tame ducks used to have a fine time swimming about, except in winter, when the pond was frozen. Emily had a name for each one of them. They used to run to her when she called; for they knew she loved them all, and would treat them well.

Among these six happy ducks there was a white one that was at one time of his life a wild duck. Emily named him Albus; for albus is Latin for white. I will tell you how Albus happened to become tamed.[70]

He was once on his way to the South with a large flock of his wild companions, when, as they were alighting near a creek, Albus was shot in the wing by Dick Barker, a sportsman who was out gunning. Dick ran with his dog Spot to pick up the poor wounded bird; but Albus was not so much hurt that he could not fly a little.

He flew and flew till he came to Emily's little garden; and then he fell at her feet, faint, but not dead, as if pleading for protection. Emily took him up in her arms, though she soiled her apron with blood in so doing. Dick and Spot came up; and Dick said roughly, "Give me up that duck."

"The duck has flown to my feet for protection; and I would be shot myself before I would betray him and give him up," said Emily. "I shall keep him, and heal his wounds."

Mr. Dick Barker scolded wildly; but it was of no use. He had to go off duckless. As for Albus, he soon grew well under Emily's tender care; but his wing was not as strong as it used to be: so he concluded he would become a tame bird, and not try to fly off again with his wild companions. He had a happy home, a kind mistress, and pleasant duck acquaintances. So, like a good sensible waddler, he was content.

"I am thinking what I shall do with this beautiful bunch of grapes," said Reka Lane as she sat on the bench near the arbor. Her real name was Rebecca; but they called her, for shortness, Reka.

"I know what I should do with it," said little Matilda, who had been wading in the brook, and was without shoes and stockings. "I should divide it among the present company."

"Good for Matty!" exclaimed brother Henry. "The best use you can put grapes to is to eat them before they spoil. Come, Reka, divide, divide."

"I am not sure that I shall do that," said Reka.[72]

"Look at that queer dog!" said Matty. "He has crept under the shawl on the ground, and looks like a head with no body to it."

"That shawl was left there the other day by old Mrs. Merton," said Reka. "The dog is her son's terrier; and his name is Beauty."

"He is any thing but a beauty," said Matty. "I think him the ugliest dog I ever saw."

"I suppose they call him Beauty to make up for the bad word he gets from every one as being ugly," said Reka. "He is a good dog, nevertheless; and he knows that shawl belongs to his mistress.—Don't you, Beauty?"

Here Beauty tore out from under the shawl, and began barking in a very intelligent manner.

"Now I will tell you what we will do," said Reka. "Put on your shoes and stockings, Matty, and we will all go and call on Mrs. Merton, who is ill; and we'll take back her shawl, and give her this beautiful bunch of grapes."

"Bow, wow, wow!" cried Beauty, jumping up, and trying to lick Reka's face.

When the children left Mrs. Merton's, after they had presented the grapes, Henry Lane made this remark, "I'll tell you what it is, girls, to see that old lady so pleased by our attention gave me more pleasure than a big feast on grapes, ice-creams, and sponge-cake, with lemonade thrown in."

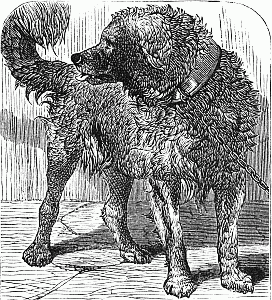

I am a middle-aged gentleman who is blessed with only one child, a little girl now nearly six years old. Her name is Fanny; and her cousin Gracie, who is about the same age, lives with us.

Both of these little girls are very fond of having me tell them stories; and I have often told them about a dog I once had. They liked this story so much, that they made me promise I would send it to "The Nursery," so that a great many little girls and boys might hear it also. This is the story:—

When I was a little boy, not more than eight years old, my mother consented to my having a dog which a friend offered to give me. He was a little pup then, not more than five weeks old. I fed him on milk for a while, and he grew very fast. I named him Cæsar.

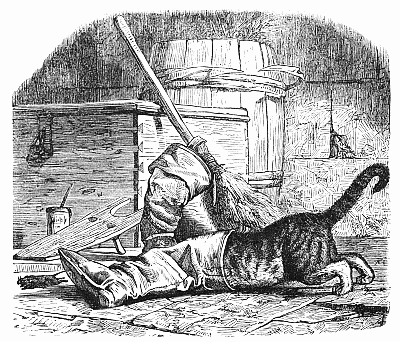

When he got to be six months old, he became very mischievous. Things were constantly being missed from the house. Handkerchiefs, slippers, shoes, towels, aprons, and napkins disappeared; and no one could tell what[74] became of them. One day Cæsar was seen going into the garden with a slipper in his mouth; and I followed him to a far-off corner where stood a large currant-bush.

I looked under the bush, and saw Cæsar digging a hole, into which he put the slipper, and then covered it up with earth. Upon digging under this bush, I found all the things that had been missed.

A neighbor's dog, called "Dr. Wiseman," was Cæsar's particular friend. One day we heard a loud scratching at the front-door; and, when we opened it, in walked Cæsar and Dr. Wiseman. Cæsar took the Doctor by the ear, and led him up to each of the family, just as if he were introducing him, and then led him into the garden, and treated him to a bone.

Although Cæsar did many naughty things, we all loved him; for he was quite affectionate as well as intelligent: but our neighbors complained of him because he chased their chickens, bit their pigs, and scared their horses. A farmer who came to our house one day with a load of potatoes took a great fancy to him. He wanted him for a watch-dog on his farm, which was only four miles from our house.

As he promised to treat him kindly, my mother thought it was best to let him have the dog; and I finally consented, although I believe I cried a good deal about it.

So Cæsar was put into the farmer's wagon, much against his will; and off he went into the country. About three months afterwards, when there was a foot of snow on the ground, there came a great scratching at the front-door of our house, early in the morning, before I was up; and, when the servant opened the door, in bounded Cæsar with a rope around his neck, and a large chunk of wood fastened to the other end of it.

He ran by the servant, and up the stairs, with the piece of wood going bump, bump, all the way, dashed into my room, jumped right up on my bed, and began licking my face.

I was very glad to see my dog again. He staid with us several days; and, when the farmer came for him, he lay down on the floor, closed his eyes, and pretended to be dead; but the farmer took him back to the farm in his wagon.

About a year and a half after that, when I came home for a vacation, we all went up to the farm, hoping to see Cæsar; but we never saw him again. The farmer had shot him, because he killed the chickens, and chased the sheep, and would not mind any thing that was said to him. Thus you see, children, that Cæsar came to a bad end, although he had every advantage of good society in his early youth.

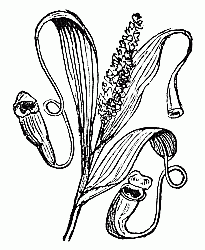

Pitcher-plants are so called, because, at the end of the leaves, the midrib which runs through them is formed into a cup shape; and in some it looks very like a pitcher or water-jug You will understand this better if you look at the drawing.

There are various kinds of pitcher-plants. Some are shorter and broader than others; but they are all green like true leaves, and hold water as securely as a jug or glass. They grow in Borneo and Sumatra, hot islands in the East. The one shown in the drawing grows in Ceylon.

Some grow in America; but they are altogether different from those in Borneo and Ceylon. One beautiful little pitcher-plant grows in Australia: but this is also very different from all the rest; for the pitchers, instead of being at the end of the leaves, are clustered round the bottom of the plant, close to the ground.

All these pitcher-plants, though very beautiful to look at, are very cruel enemies to insects: for the pitchers nearly always have water in them; and flies and small insects are constantly falling into them, and getting drowned.

Monkey-pots are hard, woody fruits; some as large and round as a cannon-ball, and some shaped like a bowl. They grow on large trees in Brazil and other parts of South America; and the natives take out the seeds, and use the fruits for holding water, or to wash themselves in.

They are called monkey-pots because monkeys are very fond of the seeds. Some of the seeds are so good, that they are collected, and sent to London and other places, where they are sold in the markets. The Brazil-nut is one of them.

"Now is the time to pick the cherries!" shouted Charles as he came running in from the garden one July afternoon.

"Are they quite ripe?" said his mother.

"Ripe? I should think so. Just look at them!" answered Charles, pointing to the trees.

"O mamma!" said Mary, "the birds are getting them all. We must have them picked at once."

"Never fear, little girl," said her mother. "There will be enough for the birds and ourselves and our neighbors too. But it really is time to begin to pick them. So,[78] Charles, get a basket, and we will all go out under the cherry-tree."

So out they all went,—Charles and Mary and Ellen and Julia and Ruth; and mamma followed with the baby.

"I told the gardener to bring a ladder," said mamma. "He will be here in a moment, Charles. You can't pick cherries without a ladder, you know."

"Of course," said that saucy boy. "Nobody can pick cherries without a ladder." And with that he gave a spring, and in about half a minute had climbed up into the tree.

"Now, girls, hold your aprons," said he. And down came a shower of the delicious fruit.

Then what a glorious scramble those little girls had! How they laughed and jumped and knocked heads together in picking up the cherries! They ate as many as they wanted; and still Charles kept throwing down more.

"Have you had enough?" said he. "So have I. Now it's time to think about filling the basket. Ah! here comes the ladder at last, with a man under it."

SLEEPING IN THE SUNSHINE.

Sleeping in the sunshine,Fie, fie, fie! While the birds are soaring High, high, high! While the buds are opening sweet, And the blossoms at your feet Look a smiling face to greet. Fie, fie, fie! Sleeping in the sunshine, Fie, fie, fie! While the bee goes humming By, by, by! Is there no small task for you,— Nought for little hands to do? Shame to sleep the morning through! Fie, fie, fie! |

Rachel has been used to a life in the city, but she is now on a visit to her uncle's in the country; and she has fine times rambling through the woods and fields.

Her cousin Paul takes her to pick berries, and tells her the names of the things she sees. "Smell of these leaves," Paul will say, breaking a twig from a shrub, somewhat like a huckleberry-bush, and crushing the leaves in his hand. "This is the bayberry-shrub. How fragrant the leaves are! It bears a berry with a gray wax-like coating; and in Nova Scotia this wax is much used instead of tallow, or mixed with tallow, to make candles."

"But what is this little red berry on the ground?" asked Rachel once when they were on one of their rambles. "It has a dark glossy leaf; and I like the taste and the smell of it very much."

"That is the checkerberry," said Paul. "Some people call it the boxberry; and some call it wintergreen. It has a flavor like that of the black birch. It is used to scent soap, and sometimes to flavor candy. It is an evergreen plant."

RAMBLES IN THE WOODS.

RAMBLES IN THE WOODS.

"What do you mean by an evergreen?" asked Rachel.

"I mean, it is green the whole year round: it does not dry up and fall off, like the leaves of the strawberry-plant," said Paul.

"What other sweet-smelling plants are there about here?" asked Rachel.

"Did you ever taste the bark of the sassafras-tree?" asked Paul. "If not, here is one; and I will break off a twig for you to chew. The color of the inner bark, near the root, is red, like cinnamon. A beer is made from it; and it is also used in soaps."[81]

"I like the odor of it very much," said Rachel.

"Here is a black-birch tree," cried Paul. "Some people call it the sweet-birch. I will cut off a piece of the bark for you to taste."

"Why, it tastes like checkerberry-leaves," said Rachel.

"Yes," replied Paul. "It is a beautiful tree, and is good for fuel. But here is a white-birch. See how white the bark is! It grows on poor land, and is a very pretty tree when well taken care of."

Here there was the sound of a horn; and Rachel asked, "What is the meaning of that sound?"

"It means that we must run home to dinner," said Paul. "So give me your hand, Cousin Rachel. You need not be afraid of snakes. There are none here that can do any harm. Come, we will make a short cut through the grove to the house."

Last summer I went to spend a few weeks at a quiet little island on the New-England coast. Every morning I used to go to the beach, and sit on the sands, and watch the blue sea with its sparkling waves, and listen to the surf breaking in white foam all along the shore.

On pleasant days the beach was lively with bathers, shouting and laughing as they plunged into the cool waves; and[83] little boys and girls playing in the clean sand, digging with their shovels, and loading and unloading their wagons, or picking up shells and sea-mosses to carry home.

On the brightest days of all, I noticed a pale-faced lady who came to sit a while in the sunshine, propped up with shawls and pillows. She always brought with her a little sky-terrier, of which she seemed as fond as if it had been a real baby.

After a while, I got acquainted with the invalid lady, and found that her name was Miss Dean, and that her dog was named Skye. He was a shaggy-looking little creature; but he had very bright eyes, and he knew almost as much as the children who played with him. He was very fond of his mistress, and very thoughtful of her comfort.

Let me tell you one thing about him that made me think so. Skye slept in the room with his mistress, on a soft cushion, with a little blanket spread over him; and in the morning, when he woke, if she was still asleep, he never disturbed her. He just sat up on his cushion as still as he could be, and watched her till she woke. As soon as she opened her eyes, he gave a little bark, for "good-morning," and sprang up on her bed, to be loved and petted.

Well, Skye was a good little dog; and we all learned to love him; and none of us would have hurt him for the world. But one day, as we were walking up from the beach, ladies and gentlemen and children and all, Skye ran down a lane, out of sight; and a thoughtless, wicked boy, who had a stone in his hand, and wanted to hit something with it, threw it with all his might at poor Skye, and broke one of his legs.

Skye cried out with the pain; and we all hurried back to see what was the matter. There we found him, whining and howling, and trying to limp along on three legs; and we just caught sight of the bad boy, running away far down[84] the lane. Miss Dean picked up her poor little darling, and carried him home.

Now, it happened that there was a very skilful surgeon staying at the hotel, who had come down to the island for a short vacation. Miss Dean sent for him, and begged him to set poor Skye's broken leg. He was a kind-hearted man, and I could not refuse to use his skill to relieve the dumb little sufferer.

So Miss Dean took Skye on her lap, and stroked him gently, and talked lovingly to him, calling him "Poor doggy!" and "Dear Skye," while the doctor made the splints, and pressed the broken bones back into their place. Then the doctor sent for some plaster of Paris, and made a soft mortar of it, and put it all around the mended leg, and let it harden into a little case, so that the bones would have to stay just as he put them till they grew together again.

All the time the doctor was doing this, Skye kept as still as a mouse; but, when it was all done, the little creature laid his head on Miss Dean's shoulder, and cried great tears, just like a child. Miss Dean had to cry, too, at the helplessness of her poor dumb darling.

For a good many weeks, Skye could only hobble about on three legs, and had to keep still on his cushion, or lie on his mistress' lap, most of the time; but he was very patient. And at last, when the good doctor said it would do to remove[85] the plaster and the splints, we did so; and Skye ran around the room as well and lively as ever. Wasn't he glad to have his liberty again!

I will tell you a true story about my sister and me. I am five years old, and Fanny (papa calls her Blossom) is three.

We are in Germany now, but our home is in America; and, when I go out to play with the boys here, they call me "America." We came over the ocean in a big ship. Papa and mamma were seasick; but Fanny and I were not, and we liked to live on the water.

When mamma packed our trunks, I wanted her to put in my little pails and wheelbarrow; and she said there wasn't room, but that we could bring as many numbers of "The Nursery" as we pleased. So we brought all we had.

We have used them so much, that papa says they are not fit to be bound; but I don't want to put them away on a shelf to be kept nice. I like to have them every day; and so does Fanny.[86]

When we were coming on the steamer, Fanny used to sit in the captain's lap, and tell him the stories.

Our auntie sends us a new "Nursery" every month. One was lost, and we were very sorry; for we can't read other picture-books so well. Fanny always has a "Nursery" to take to bed with her; and in the morning, when I wake up, I hear her talking to the boys and girls in the pictures.

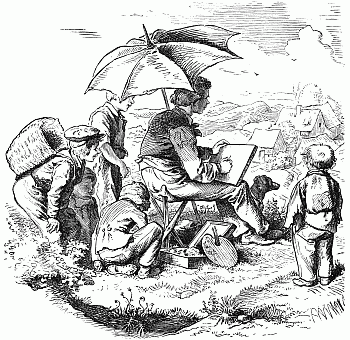

The landscape-painter sat on a camp-stool with an umbrella over his head. His palette and his box of paints were on the ground by his side. He was there to draw a picture of the village of F——.

Hardly had he begun his crayon outline when he heard a boy's voice behind him. "May I look on? sir?" said the boy. "Yes, look as much as you please, but don't talk," said the painter without turning his head.[88]

The boy had a basket strapped to his back, and stood looking intently, with both hands resting on his knees. His name was Norman Blake. Other boys, and a young woman, soon came up, and joined him as spectators.

Norman studied every movement of the painter's hand; and, when he got home, he took a piece of charcoal, and tried to draw a picture on the wall. Rather a rough picture it was, but pretty good for a first attempt.

The next day Norman went again, and looked on while the painter sketched. "You've got that line wrong," cried Norman all at once, forgetting that the painter had told him not to talk.

"What do you know about it, you young vagabond?" cried the painter angrily. "Out of this! Run, scamper, and don't show your rogue's face here again! But stop. Before you go, come here, and point out what struck you as wrong."

Norman pointed to a certain line which made the village church seem a little out of its right place in the picture. The landscape-painter seized him by the ear, and said, "You little scamp, how did you find that out? You are right, sir! But what business have you to criticise my picture? I am hesitating whether to thrash you, or to make a painter of you."

"Make a painter of me, by all means;" said Norman, laughing; for he saw that the honest painter was only half in earnest.

Well, the end of it was, that Norman accompanied the painter to the city, and began to study drawing and painting. He succeeded so well, that, after he had been studying six years, he one day brought to his friend the painter the sketch which we have had copied above.

"Do you remember that?" asked Norman.[89]

"Of course I do!" said the painter. "It represents our first meeting. Little did I think that the young vagabond with the basket on his back would one day beat me in sketching."

Hurrah! Great boot-race under difficulties.

Hurrah! Great boot-race under difficulties.

"Now, when she comes out, I shall be sure of her!"

"Now, when she comes out, I shall be sure of her!"

There were three children on the beach looking out to see the boats of the fishermen sail off to the fishing-grounds. Little Joe Bourne and his sister Susan stood side by side, watching their father's boat. Rachel, who was with them, was not their sister, but an orphan-child, whose grandfather, Mr. Harrison, was in one of the boats.

It was a windy day in November. The waves broke with a great noise on the shingly beach. Soon the wind rose higher: the sea rose too, and the rain fell fast. The children walked back to the village; and there the old men said, shaking their heads, "We shall have a storm."

That night, all the boats came safely back into the harbor, excepting the boat in which Rachel's grandfather had sailed. It was a long, sad night for poor Rachel. The next day and the next passed by; and no grandfather came back to take care of her, and find her in food and clothes, and carry her in his strong arms when she was tired out with walking.[93]

Susan and Joe in their own house felt sad for the little orphan. One day their mother went to market. Baby was in the cradle, and Susan was rocking it, whilst Joe was cutting out a boat with an old jack-knife. The kettle on the stove began to sing; and Susan and Joe began to talk.

"Poor Rachel will have to be sent to the workhouse now," said Joe.

"I hope not," said Susan. "I hope father will give her a home in our own house."

"Why, he says he can hardly earn enough to feed his own family," said Joe.

"But can't we do something to help him?" asked Susan.

"I know of nothing children like us can do," said Joe.

When their mother came home, Susan begged so earnestly to have Rachel come and stay with them, that Mrs. Bourne at last replied, "Well, we will take her in for a week or two, and see; but mind, Susan, you must try and earn a little money somehow. You will now have less time to play on the sands, remember."[94]

So Susan went and found Rachel, and brought her home to live with them all. The poor little orphan was a bright, joyous child. She had a strange hope that she should see her grandfather again; that he was not lost; for he had told her many stories of his escape from great dangers at sea.

"Why, grandfather was on a wreck once a whole week," said Rachel: "he was cast away once on an island where he had to live on clams a long while before he was rescued. I think we shall hear from him soon."

One day Joe caught a fine basket of perch from the rocks, and went round to try and sell them. But all the folks in the village told him they could get as many fish as they wanted without buying them. So Joe walked off to a town four miles away from the sea, and there he sold his fish.

He told a kind blind lady, to whom he sold some, that his sister wanted to get work, so that she could help a poor little orphan-girl. The kind lady sent Susan half a dozen handkerchiefs to hem; and the next morning Susan rose early, and sewed by candle-light, while the other children were in bed and asleep.[95]

For three years the poor Bourne family gave Rachel a nice happy home in their little house; and they would have kept her longer, but one day, while the children were all playing on the beach, they heard a great shouting, and ran to see what it was about.

It was all in honor of Grandfather Harrison. He had come back, as Rachel had always said he would. He had been picked up at sea in his sinking boat by a ship bound for Australia. The old man was carried to that far country. He went to the mines, and helped some men dig gold. He made a good deal of money, thinking it would be a good thing if he could only be rich enough to send his dear little grand-daughter to school.

But Rachel was not the only one who was benefited by his good fortune. The Bournes shared in it. Joe and Susan, and all the rest of the children, were sent to school also; and they studied with a will. It was always a happy thought to Rachel that the great kindness of these good people did not miss its reward even in this life.

| 2. Then little Maggie sings to him, And plays upon the harp; While rapid Robert, keen and slim, Cries, "Lazybones, look sharp!" And Lucy tickles with her wand, This sleepy, lazy boy; And one and all with tricks and jokes In teasing him take joy. | 3. But Lazybones must take his nap Before he goes to bed: He does not move his weary limbs Or lift his heavy head. And though a dozen brewers' drays Should rumble o'er the stones, Not all the noise that they can make Would rouse Young Lazybones. |

Obvious punctuation errors repaired.

This issue was part of an omnibus. The original text for this issue did not include a title page or table of contents. This was taken from the July issue with the "No." added. The original table of contents covered the second half of 1873. The remaining text of the table of contents can be found in the rest of the year's issues.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Nursery, September 1873, Vol. XIV.

No. 3, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NURSERY, SEPT. 1873, VOL.XIV NO.3 ***

***** This file should be named 24940-h.htm or 24940-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/2/4/9/4/24940/

Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net Music

by Linda Cantoni.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.