The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Rich Little Poor Boy, by Eleanor Gates This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Rich Little Poor Boy Author: Eleanor Gates Release Date: February 21, 2008 [EBook #24663] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RICH LITTLE POOR BOY *** Produced by Suzanne Lybarger, Brian Janes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net and and the Booksmiths at http://www.eBookForge.net

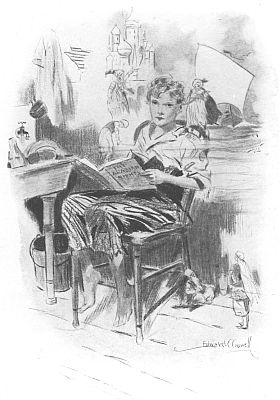

WHAT HE SAW THERE HELD HIM SPELLBOUND IN HIS CHAIR

WHAT HE SAW THERE HELD HIM SPELLBOUND IN HIS CHAIR

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Wicked Giant | 1 |

| II. | Pride and Penalty | 10 |

| III. | A Feast and an Excursion | 17 |

| IV. | The Four Millionaires | 24 |

| V. | New Friends | 36 |

| VI. | The Dearest Wish | 52 |

| VII. | A Serious Step | 60 |

| VIII. | More Treasures | 68 |

| IX. | One-Eye | 79 |

| X. | The Surprise | 93 |

| XI. | The Discovery | 108 |

| XII. | A Prodigal Puffed Up | 117 |

| XIII. | Changes | 122 |

| XIV. | The Heaven that Nearly Happened | 138 |

| XV. | Scouts | 144 |

| XVI. | Hope Deferred | 153 |

| XVII. | Mr. Perkins | 160 |

| [viii]XVIII. | The Roof | 172 |

| XIX. | A Different Cis | 183 |

| XX. | The Handbook | 190 |

| XXI. | The Meeting | 201 |

| XXII. | Cis Tells a Secret | 212 |

| XXIII. | Roses that Tattled | 219 |

| XXIV. | Father Pat | 233 |

| XXV. | An Ally Crosses a Sword | 241 |

| XXVI. | The End of a Long Day | 247 |

| XXVII. | Another Gift | 255 |

| XXVIII. | Another Story | 275 |

| XXIX. | Revolt | 290 |

| XXX. | Disaster | 300 |

| XXXI. | The Vision | 318 |

| XXXII. | Help | 330 |

| XXXIII. | One-Eye Fights | 345 |

| XXXIV. | Sir Algernon | 357 |

| XXXV. | Good-bys | 363 |

| XXXVI. | Left Behind | 373 |

| XXXVII. | Ups and Downs | 379 |

| XXXVIII. | Another Good-by | 391 |

| XXXIX. | The Letter | 400 |

| XL. | "The True Way" | 407 |

HE was ten. But his clothes were forty. And it was this difference in the matter of age, and, consequently, in the matter of size, that explained why, at first sight, he did not show how thin-bodied he was, but seemed, instead, to be rather a stout little boy. For his faded, old shirt, with its wide sleeves lopped off just above his elbows, and his patched trousers, shortened by the scissors to knee length, were both many times too large for him, so that they lay upon him, front, back and sides, in great, overlapping pleats that were, in turn, bunched into heavy tucks; and his kitchen apron, worn with the waistband about his neck, the strings being tied at the back, also lent him—if viewed from the front—an appearance both of width and weight.

But he was not stout. His frame was not even fairly well covered. From the apron hem in front, the two legs that led down to the floor were scarcely larger than lead piping. From the raveling ends of his short sleeves were thrust out arms that matched the legs—bony, skinny arms, pallid as to color, and with hardly any more shape to them than there was to the poker of the cookstove. But while the lead-pipe legs ended in the sort of hard, splinter-defying boy's feet that could be met with on any stretch of pavement outside the tenement, the bony arms did not end in boyish hands. The hands that hung, fingertips touching halfway to the knee, were far too big for a boy of ten. They were red, too, as if all the blood of his thin shoulders had run down his arms and through his[2] wrists, and stayed there. And besides being red, fingers, palms and backs were lined and crinkled. They looked like the hands of a hard-working, grown girl. That was because they knew dish washing and sweeping, bed making and cooking, scrubbing and laundering.

But his head was all that a boy's head should be, showing plenty of brain room above his ears. While it was still actually—and naturally—large for his body, it looked much too large; not only because the body that did its bidding was undersized, but because his hair, bright and abundant, added to his head a striking circumference.

He hated his hair, chiefly because it had a hint of wave in it, but also because its color was yellow, with even a touch of green! He had been taunted about it—by boys. But what was worse, women and girls had admired it, and laid hands upon it—or wanted to. And small wonder; for in thick undulations it stood away from forehead and temples as if blown by the wind. A part it had not, nor any sort of neat arrangement. He saw strictly to that. Whenever his left hand was not busy, which was less often than he could wish, he tugged at his locks, so that they reared themselves on end, especially at the very top, where they leaned in various directions and displayed what appeared to be several cowlicks. At every quarter that shining mop was uneven, because badly cut by Big Tom Barber, his foster father, whose name belied his tonsorial ability.

Below that wild shock of colorful hair was a face that, when clean, could claim attention on its own account. It was a square-jawed little face over which the red was quick to come, though, unhappily, it did not stay. Its center was a nose that seemed a trifle small in proportion to its surroundings. But the top line of it was straight, and the nostrils were well carved, and had a way of lifting and swelling whenever his interest was caught.[3]

Under them was a mouth that was wide yet noticeably beautiful—not with the soft beauty of a baby's mouth, or a girl's, and not because it could boast even a touch of scarlet. It had been cut as carefully as his nose, the lips full yet firm, their lines drawn delicately, but with strength. It was sensitive, with a little quirk at each corner which betrayed its humor. Above all things, its expression was sweet.

Colorless as were his cheeks and lips, nevertheless he did not seem a pale boy, this because his brows were a misty yellow-white, and his thick lashes flaxen; while his eyes were an indescribable mixture of glowing gray and blue plentifully flecked with yellow. Perfectly adjusted were these straight-looking eyes, and set far apart. By turns they were quick, and bold, and open, and full of eager inquiry; or they were thoughtfully half covered by their heavy lids, very still, and far sighted. And when he laughed, what with the shine of his hair and brows and light lashes, and the flash of his eyes and his teeth, the effect was as if sunlight were upon his face—though the sun so seldom shone upon him that he had not one boyish freckle.

Such was Johnnie Smith.

Just now he was looking smaller and less sunlit than usual. This was because Big Tom bulked in front of him, delivering the final orders for the day before going down the three flights of stairs, out into the brick-paved area, thence through a dank, ground-floor hall which bored its way from end to end of another tenement, and into the crowded East Side street, and so to his work on the docks.

Barber was a huge-shouldered, long-armed slouch of a man, with a close-cropped head (flat at the back) upon which great hairy ears stood out like growths. His eyes were bloodshot and bulging, the left with an elusive cast in it that showed only now and then, when it testified to the[4] kink in his brain. His nose, uneven in its downward trend, was so fat and wide and heavy that it fairly sprawled upon his face; and its cavernous, black nostrils made it seem to possess something that, to Johnnie, was like a personality—as if it were a queer sort of snakish thing, carefully watched over by the bulging, bloodshot eyes.

For Barber's nose had the power of moving itself as Johnnie had seen no other nose move. Slowly and steadily it went up and down whenever Barber ate or talked—as even Johnnie's small, straight nose would often do. But whenever Big Tom laughed—sneeringly or boastfully or in ugly triumph—the nose would make a sudden, sidewise twist.

But something besides its power to move made it seem a live and separate thing: the longshoreman troubled himself to shave only of a Sunday morning, when, with all the stiff, dark growth cleared away to right and left—for Barber's beard grew almost to his eyes—his nose, though bent and purplish, was fairly like a nose. But with Monday, again the nose took on that personality; and seemed to be crouching and writhing at the center of its mat of stubble.

But Barber's mouth was his worst feature, with its great, pushed-out underlip, which showed his complete satisfaction in himself. So big was that lip that it seemed to have acquired its size through the robbing of the chin just beneath—for Big Tom had little enough chin.

But his neck was massive, and an angry red, sprinkled with long, wiry hairs. It fastened his flat-backed head to a body that was like a gorilla's, thick and wide and humped. And his arms gave an added touch of the animal, for they were so long that his great palms reached to his knees; and so sprung out at the shoulder, and so curved in at the wrist, that when they met at the fingers they formed a pair[5] of mammoth, muscled tongs—tongs that gave Barber his boasted value in and out of ships.

His legs were big, too. As he stood over Johnnie now, it was plain to see where the boy's shaggy trousers had come from (the grotesquely big shirt as well). Each of those legs was almost as big as Johnnie's skimped little body. And they turned up at the bottom in great broganned feet that Barber was fond of using as instruments of punishment. More than once Johnnie had felt those feet. And if he could ever have decided how pain was to be inflicted upon him, he would always have chosen the long, thick, pliant strap that belted in, and held together, his baggy clothes. For the strap left colorful tracks that stung only in the making; but the mark of one of those feet went black, and ached to the bone.

Johnnie hated Big Tom worse than he hated his own yellow hair. But he feared him, too. And now listened attentively as the longshoreman, his cutty pipe smoking in one knotted fist, his dinner pail in the other, his cargo hook slung to his burly neck, glowered down upon him.

"Git your dishes done," admonished Barber. "Don't let the mush dry on 'em, and draw the flies."

There being no question to answer, Johnnie said nothing. Final orders of a morning were the usual thing. If he was careful not to reply, if he waited, taking care where he looked, the longshoreman would have his say out and go—pressed by time. So the boy, almost holding his breath, fastened his eyes upon a patch of wall where the smudged plaster was broken and some laths showed. And not a muscle of him moved, except one big toe, which he curled and uncurled across a crack in the rough, worn kitchen floor.

"Git everything else done, too," went on Big Tom. "You don't scrub till to-morrow, so the day's clear for stringin' beads, or makin' vi'lets. And don't let me come[6] home t'night and find no hot supper. You hear me." He chewed once or twice—on nothing.

Johnnie continued silent, counting the laths—from the top down, from the bottom up. But his toe moved a shade faster. For there was a note of rising irritation in that You hear me.

"I say, you hear me!" repeated Big Tom (replies always angered him: this time silence had). He thrust the whole of the short stem of his "nose-warmer" into his mouth. Then, with the free hand, he seized Johnnie by one thin shoulder and gave him a rough, forward jerk.

"Yes," acknowledged the boy, realizing too late that this was one occasion when speech would have been safest. He still concentrated on the laths, hoping that matters would go no further.

But that single jerk, far from satisfying Barber's rancor, only added to it—precisely as if he had tasted something which had whetted his appetite for more. He gripped Johnnie's shoulder again, this time driving him back a step. "Now, no sass!" he warned.

The blood came rushing to Johnnie's face, darkening it so that the misty yellow-white brows stood out grotesquely. And his chest began to heave. He loathed the touch of Barber's hand. He despised the daily orders that only turned him against his work. But most of all he shrank from the indignity of being jerked when it was wholly undeserved.

Big Tom marked the boy's rising color. And the sight spurred his ill-humor. "What do you do for your keep?" he demanded. "Stop pullin' your hair!" He struck Johnnie's hand down with a sweaty palm that touched the boy's forehead. "Pullin' and hawlin' all the time, but don't earn the grub y' swallow!"

Just as one jerk always led to another, so one blow was usually the prelude to a thrashing. Johnnie saw that he[7] must stop the thing right there; must have instant help in diverting Barber. Taking a quick, deep breath, he sounded his call for aid—a loud, croupy cough.

It was instantly answered. The door beside the cookstove swung wide, and Cis came hurrying in from the tiny, windowless closet—this her "own room"—where she had been listening anxiously. "Oh, Mr. Barber," she began, trying to keep her young voice from trembling, "this week can I have enough out of my wages for some more shoe-whitening?"

There were several ways in which to take Big Tom's mind from any subject. The surest of these was to bring up a question of spending. And now, answering to his stepdaughter's subterfuge as promptly as if he were a mechanism that had been worked by a key, he turned from glowering down upon Johnnie to scowl at her.

"More?" he demanded harshly.

Her blue eyes met his look timidly. Out of the wisdom of her sixteen-year-old policy, she habitually avoided him, slipping away of a morning to her work at the pasteboard-box factory without a word; slipping back as quietly in the late afternoon; keeping out of his sight and hearing whenever that was possible; and speaking to him seldom.

Cis looked at every one timidly. She avoided Big Tom not only because it was wise to do so but because she was naturally shy and retiring, and avoided people in general. She had a quaint face (framed by straight, light-brown hair) that ended in a pointed, pink chin. Habitually she wore that expression of mingled understanding and responsibility common to all children who have brought up other children. So that she seemed older than she was. But her figure was that of a child—slim, frail, and still lacking a woman's shapeliness, notwithstanding the fact that it had long carried the burdens of a grown-up.[8]

Facing her stepfather now, she did not falter. "Yes, please," she answered. "The last, I got a month ago."

His pipe was in his fist again, and he was chewing wrathfully. "I'll see," he growled. And waved her to go.

From the hall door, she glanced back at Johnnie. Not only had she and he a system of communication by means of coughs, humming, whistles, taps and other audible sounds; and a second system (just as good) that depended upon wall marks, soap-inscribed hieroglyphics on the bit of mirror in Cis's room, or the arrangement of dishes on the kitchen table, and pots and pans on the stove, but they had a well-worked-out silent system—by means of brow-raisings, eye and lip movements, head tippings and swift finger pointings—that was as perfect and satisfactory as the dumb conversation of two colts. Such a system was necessary; for whenever the great figure of Barber came wedging itself through the hall door, and his presence, like a blighting shadow, darkened the already dark little flat, then the two young voices had to fall instantly silent, since Barber would brook no noise—least of all whispering.

Now by the quick, sidewise tip of her small, black-hatted head, Cis inquired of Johnnie whether she should stay or go. And Johnnie, with what amounted to an upward fling of his eyelids, answered that she need not stay. With Barber's cutty once more in his right fist, and with his mind veered to a fresh subject, Johnnie knew the crisis was past.

With a swift glance of affection and sympathy, not unmixed with triumph over the success of her interruption, Cis fluttered out—leaving the door open at Barber's back.

The longshoreman turned heavily as if to follow her, but came about with a final caution, lowering his voice to cheat any busy ear in the other flat on the same floor. "Don't you neglect the old man," he charged. "Face—hair—fix him up—you know."[9]

At the stove, an untidy heap of threadbare, brown blanket, in a wheel chair suddenly stirred. In several ways old Grandpa was like a big baby, but particularly in this habit of waking promptly whenever he was mentioned. "Is that you, Mother?" he asked in his thin, old voice. (He meant Big Tom's mother, dead now these many years.)

A swift change came over Barber's face. His great underlip drew in, what chin he had was thrust out with something like concern, and his eyes rolled away from Johnnie to the whimpering old man. "It's all right, Pa," he said soothingly. "It's all right. Jus' you sleep." Then he turned, tiptoed through the door, and shut it after him softly.

Johnnie did not move—except to shift his look from the laths to the door knob, and take up his toeing of the crack at his feet. The door itself moved, and rattled gently, as the area door three flights below was opened by Cis, and a gust from the narrow court was sent up the stairs of the tenement, as a bubble forces its way surfaceward through water, to suck at the Barber door.

But Big Tom was not yet gone. And a moment later, the boy was looking at the outer knob, now in the clutch of several great, grimy, calloused fingers.

"Let your hair alone!" ordered the longshoreman. Then the door closed finally, and the stairs complained with loud creakings as Barber descended them.

Johnnie waited till the door in front of him moved and rattled again, then[10]—

HIS toe stopped working across the crack in the floor. His left hand forsook his tousled hair and fell to his side. His eyes narrowed, and his chin came up. Then his lips began to move, noiselessly. "I'll pay him up for that!" he promised. "I'll make him wish he didn't shove me! This time, I'll think a' awful bad think about him! I'll think the worst think I can! I'll—I'll——"

He paused to decide. He had many "thinks" for the punishing of Big Tom, each of them ending in the desertion of that gentleman, who was always left helplessly groveling and pleading while Johnnie made a joyous, triumphant departure. Which of all those revenges would he select this morning? Would he go, after handing the longshoreman over to the harshest patrolman in New York? or would it be a doctor who would remain behind in the flat with the tyrant, assuring Johnnie, as the latter sauntered out of the kitchen for the very last time, that no skill on earth could entirely mend the hurts which he had so bravely inflicted upon his groaning foster father? or would he set sail grandly from the Battery for some port at least a million miles away, his last view of the metropolis including in its foreground, along with a brass band and many dignitaries of the city, the kneeling shape of a wretched dock-worker who had repented of his meanness too late?

Suddenly Johnnie caught his breath, his eyes dilated,[11] his fingers began to play against his palms. He had decided. And in that same instant, a change came over him—complete, satisfactory, astonishing.

Now, instead of the ragged, little boy upon whom Big Tom had glowered down—a meek boy, subdued, even crestfallen, whose eyes were lowered, and whose lashes blinked fearsomely, he was quite a good deal taller, boldly erect, proud in his poise, light on his neatly shod feet, confident and easy in his manner, with a charming smile to right and left as ringing cheers went up for him while he awaited the lessening of the pleasant tribute, his composure really quite splendid, his hands stuffed into the pocket of his absolutely new, light-gray suit, which had knee pants.

A change had also taken place in the Barber kitchen. Now the walls were freshly papered in a regal green-and-gold pattern which, at the floor line, met a thick, red carpet. Red velvet curtains hung at either side of the window. Splendid, fat chairs were set carelessly here and there; and a marble-topped table behind Johnnie was piled with a variety of delectable dishes, including several pies oozing juice.

And the crowd that pressed up to the hall door! It was worthy of his pride, for it was a notable gathering. In it was no tenant of the building, no neighbor from other, near-by flats, and not a single member of that certain rough gang which haunted the area, the dark halls leading into it, and all the blocks round about.

Indeed, no! Even in his "thinks" Johnnie was most careful regarding the selection of his companions, his social trend being ever upward. And he was never small about any crowd of his, but always had everybody he could remember who was anybody—a riot of famous people. On this occasion he was reaching into truly exclusive circles. Naturally, then, this was a well-dressed assemblage, strikingly equipped with silk hats (there were no ladies present)[12] and gold-headed canes; and every gentleman in the gathering wore patent-leather shoes, and a vest that did not match his coat. All were smart and shaven and wealthy. In their lead, uniformed in khaki, and wearing the friendliest look possible to a young man who is cheering, was His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales.

Like all the others in that wildly enthusiastic gathering, the young heir apparent was turned toward Johnnie as toward a hero. And small wonder. For there, between the distinguished crowd and the boy, lying prone upon the red carpet, in his oldest clothes, and unshaven, was none other than Big Tom Barber, felled by the single, overwhelming blow that Johnnie had just given him, his nose bleeding (not too much, however) and the breath clean knocked out of him.

Now the shouting died away, and Johnnie addressed the admiring throng. But his lips moved without even a whisper. "I made up my mind a long time ago," he began, "to give Tom Barber a good thrashin'. So this morning, I done it."

Despite his ungrammatical conclusion, the speech called forth the resounding hurrahs of the Prince and his gentlemen, and once more Johnnie had to wait, striving to appear properly modest, and twirling a gold watch chain all of heavy links. But he could not keep his nostrils from swelling, or his eyes from flashing. And his chest heaved.

It was now that he made Cis one of his audience, dressing her in a becoming pink gown (her favorite color). Old Grandpa was standing beside her, no longer feeble and chair bound, but handsomely overcoated and hatted, and looking as formidable as any policeman. These two, naturally enough, had only proud glances for the young champion of the hour.

But Johnnie's task of subduing Barber was not finished. The brave boy could see that the big longshoreman was[13] making as if to rise. Johnnie could still feel the touch of Big Tom's perspiring hand on his forehead, and the pinch of those cruel fingers on his shoulder. Taking a forward step, he gave Barber's shoulder a wrenching jerk, then thrust the longshoreman backward by a spanking blow of the open palm full upon that big, ugly, bristling face.

Again Barber fell prostrate. He was purple with mortification, and leered up at Johnnie murderously.

"Ha! ha! Y' got enough?" Johnnie inquired. He was all of a glow now, and his face fairly shone. But he was not done with the tyrant. A sense of long-outraged justice made him hand Barber the big, black, three-legged, iron kettle that belonged on the back of the cookstove. There was some cold oatmeal in the bottom of the kettle, and Johnnie also handed the longshoreman a spoon—with a glance toward the Prince, who seemed awed by Johnnie's complete mastery of the enemy. "Here!" the boy directed, giving the pot a light kick with a new shoe (which was brown). "Go ahead and eat. Eat ev'ry bite of it. It's got kerosene in it!"

Now Barber got to his knees imploringly. "Oh, don't make me eat it!" he begged. "Oh, don't, Johnnie! Please!"

"Y' made me eat it once," said Johnnie quietly. "And y' need a lesson, Tom Barber, and I'm givin' y' one."

Barber choked down the bad-tasting food. But there was no taunting of him. Johnnie kept a dignified silence—as did also the Prince and the gentlemen. But when the last spoonful was swallowed, and Barber was cowering beside the empty kettle, the boy felt called upon to go still further, and make away finally with that strap which was the symbol of all he hated—that held up and together the too-large clothes which had so long mortified his pride; that stood for the physical pain dealt out to him by Big Tom if he so much as slighted a bit of his girl's work.

The strap was around him now, even over that new suit.[14] It circled him like a snake. He took it off, his lips working in another splendid speech. "And I don't wear it ever again," he declared, looking down at Barber. "Do y' understand that?" He flicked a big arm with the leather, though not hard enough to give pain.

"Yes," faltered the longshoreman, shrinking.

"Well, I'm glad y' understand it," returned Johnnie. "And now you just watch me for on-n-ne second! You won't never lay this strap across me> again!"

He whipped out a long, sharp, silver-handled bread-knife. Then turning to the table, he laid the strap upon the beautiful marble; and, in sight of all, cut it away to the very buckle—inch by inch!

"Now!" he cried, as he scattered the pieces upon the carpet.

The punishment was complete; his triumph nothing less than perfect. And it occurred to him now that there was particular gratification in having present this morning His Royal Highness. "Mister Prince," he said, "I'm awful tickled you was here!"

The Prince expressed himself as being equally pleased. "Mister Smith," he returned, "I don't know as I ever seen a boy that could hit like you! Why, Mister Smith, it's wonderful! How do y' do it?" He shook Johnnie's hand warmly.

"Well, I guess I'm like David, Mister Prince," Johnnie explained modestly. "O' course you know David—and his friend, Mister Goli'th?—Oh, y' don't? Y' mean y' ain't never met neither one? Oh, gee! I'm surprised! But that's 'cause y' don't know Mrs. Kukor, upstairs. They're both friends of hers. Well, I'll ask 'em down."

An upturned face and a beckoning arm accomplished the invitation, whereupon there entered at once the champion Philistine and that youth who was ruddy and of a fair countenance. And after a deal of hand-shaking all[15] around, Johnnie told the tale of that certain celebrated fight—told it as one who had witnessed the whole affair. He turned his face from side to side as he talked, gesticulating with easy grace.

"And now I guess we're ready t' start, ain't we?" he observed as he concluded. "David, would you and your friend like t' come along?—Only Big Tom, he's got t' stay behind, 'cause——"

At the stove, the untidy heap of brown blanket in the wheel chair stirred again. Out of the faded folds a small head, blanched and bewhiskered, reared itself weakly. "Johnnie," quavered old Grandpa. "Johnnie! Milk!"

The boy's lips ceased to frame words. His right arm fell to his side; the left went up again to resume that tugging at his hair. He swayed slightly, shifting his weight, and his big toe began once more to curl and uncurl. Then, as fancy was displaced by reality, as dreaming gave place to fact, Barber disappeared from the floor. The silk-hatted gentlemen with the gold canes went, too—along with the gallant young English Prince, that other Prince who was of Israel, and a tall person with a sore, red bump on his forehead. The gold-and-green walls faded; so did the carpet, the curtains, and that light-gray suit (which was precisely like the one Johnnie had worn when he first came to the Barber flat—except, of course, that it was larger). The marble-topped table and the fat chairs folded themselves up out of sight. And all those delicious fruit pies dissolved into thin air.

But one thing did not go: A sense of satisfaction. Having met his enemy before the world, and conquered him; having spent his own anger and loathing, and revenged the other's hated touch, his gray eyes held a pleased, proud look. Once more in the soiled big shirt and trousers, with the strap coiled about his middle, he could put Barber[16] aside for the day—not brood about him, harboring ill-will, nor sulk and fret.

Now he was ready for "thinks" of a different sort—adventures that were wholly delightful.

A feeling of joy surged through him. Ahead lay fully nine unhampered hours. He pivoted like a top. His arms tossed. Then, like a spring from which a weight has been lifted, like a cork flying out of a charged bottle, he did a high, leaping hop-skip straight into the air.

"Wow-ow-ow-ow-ow!" he sang out full-throatedly. "Rr-r-r-r! ree-ee-ee!"—and explosively, "Brt! brt! brt! bing!"[17]

NINE free hours!—or, to be exact, eight, since the best part of one would have to be devoted to the flat in order to avoid trouble. However, Johnnie never did his work any sooner than he actually had to; and that hour of labor should be, as always, the last of the nine, this for the sake of obeying Big Tom at the latest possible time, of circumventing his wishes, and thwarting and outwitting him, just to the degree that safety permitted.

So! For eight hours Johnnie would live his dreams. And, oh, the things he could do! the things!

But before he could begin the real business of the day, he had to put Grandpa to sleep again. This was best accomplished through tiring the little old man with a long, exciting train trip. "Oo, Grandpa!" cried Johnnie. "Who wants to go ride-ride on the cars?"

"Cars! cars! cars!" shrilled Grandpa, his white-lashed, milky-blue eyes dancing. At once, impatiently, he fell to tapping on the floor with his cane, while, using his other hand, he swung the wheel chair in a circle. Across his shrunken chest, from one side of the chair to the other, was a strand of rope that kept him from tumbling out of his seat. To hasten the promised departure, he began to throw his weight alternately against the rope and the back of the chair, like an excited baby.

"Wait now!" admonished Johnnie. He took off his apron and wadded it into a ball. Then with force and[18] fervor he sent the ball whizzing under the sink. "Where'll we go?" he cried. The bottoms of his trouser legs hung about his knees in a fringe. Now as he did another hop-skip into the air, not so much because of animal spirits as through sheer mental relief, all that fringe whipped and snapped. "Pick out a place, Grandpa!" he bade. "Where do y' want t' go?"

"Go! go! go!" chanted the old man. Not so long ago he had been able to call up a score of destinations—most of them names that had to do with the Civil War campaigns which, in the end, had impaired his brain and cost him the use of his legs.

Johnnie proceeded to prompt. "Gettysburg?" he asked; "Shiloh? Chick'mauga? City of Washingt'n? Niaggery Falls?"

"Niaggery Falls!" cried Grandpa, catching, as he always did, at whatever point was named last. "Where's my hat? Where's my hat?"

He never remembered how to find his hat, though it always hung conveniently on the back of the wheel chair. It was the dark, broad-brimmed, cord-encircled head covering of the Grand Army man. As he turned his head in a worried search for it, Johnnie set the hat atop the white hair.

Johnnie had named Niagara last because he liked best to visit that Wonder of Nature. He did not know why—except that the name seemed curiously familiar to him. It was familiar to Grandpa, too, in a dim way, for he had visited "the Falls" on his wedding trip. And every repetition of the imaginary journey thrilled him.

"Chug! chug! chug!" he began, the moment he felt the hat. His imitation of a starting engine was so genuine that it shook his spare frame from his head to his slippered feet. "Chug! chug! chug!"

But Johnnie was not ready to set off. The little, old[19] soldier had not yet eaten his breakfast, and if he did not eat he would not go to sleep promptly at the conclusion of the trip, nor stay asleep.

"Oh, Grandpa," began the boy coaxingly, as he hastily dished up a saucer of oatmeal, another saucer of prunes, and poured a glass of milk, "before we start we got t' eat our grand banquet! It's a long way to Niaggery, y' know. So here we both are at the Grand Central Station!" (The Station was situated on or about the center of the kitchen.)

"Station!" echoed Grandpa. "Chug! chug! chug!"

"No, Grandpa,"—Johnnie's manner of handling the old man was comically mature, almost motherly; his tone, while soothing, was quietly firm, as if he were speaking to a younger child. "See! Here's the fine table!"

Up to this table, still strewn with unwashed dishes and whatever remained of breakfast, the pair of travelers drew. Then Johnnie, with the air and the lavishness of a millionaire, ordered an elaborate and tasty breakfast from a waiter the like of whom was not to be found anywhere save in his own imagination.

This waiter's name was Buckle, and he had served Johnnie faithfully for the past several years. In all ways he was an extraordinary person of his kind, being able to furnish anything that Grandpa and Johnnie might call for, whether meat, vegetable or fruit, at any time of the year, this without regard to such small matters as seasons, the difficulties of importing, adverse hunting laws, and the like. Which meant that Grandpa could always have his venison, and Johnnie his choice of fruits—all from the deft hand of a man quick and soft-footed, and full of low bows, who wore a suit of red velvet fairly loaded with gold bands and brass buttons.

"Mister Buckle," began Johnnie (for such an august creature in red velvet could not be addressed save with a courteous title), "a turkey, please, an' some lemon pie, an'[20] some strawberry ice cream an' fifteen pounds of your best candy."

"Candy! candy! candy!" clamored Grandpa, impatiently beating on the table with his spoon like a baby.

Buckle was wonderful. As Johnnie's orders swept him hither and thither, how he transformed the place, laying down the articles called for upon a crisp red tablecloth that was a glorious full brother to one that belonged to the little Jewish lady who lived upstairs. But Grandpa took little interest in Buckle, though he picked eagerly enough at the viands which Johnnie urged upon him.

"Here's your turkey," pointed out the boy, giving the old man his first spoonful of cereal. "My goodness, did y' ever see such a drumstick! Now another!—'cause, gee! you'll be starved 'fore ever we git t' Niaggery! Mm! but ain't that turkey fine?"

"Mm! Mm!" agreed the veteran.

"Mister Buckle, I'll take some soda and some popcorn," went on Johnnie, spooning out his own saucer of oatmeal. "And some apples and oranges, and bananas and cherries and grapes."

Fruit was what he always ordered. How almost terribly at times he yearned for it! For the only fruit that ever Barber brought home was prunes. Johnnie washed them and put them over the fire to boil with a regularity due to his fear of the strap. But he hated them. (Likewise he pitied them—because they seemed such little, old creatures, and grew in that shriveled way which reminded him somehow of Grandpa.) What he longed for was fresh fruit, which he got only at long intervals, this when Cis carried home to him a few cherries in the bottom of a paper bag, or part of an apple which was generously specked, and so well on its way to ruin, or shared the half of a lemon, which the two sucked, turn about, all such being the gifts of a certain old gentleman with a wooden leg who[21] carried on a thriving trade in the vicinity of the nearest public school. But the periods between the contributions were so long, and the amount of fruit consumed was so small, that Johnnie was never even a quarter satisfied—except at one of his Barmecide feasts.

Grandpa's oatmeal and milk finished, Johnnie urged the prunes upon him. "Oo, lookee at the watermelon!" he cried. "The dandy, big watermelon!—on ice!"

The mere word "watermelon" always stirred a memory in old Grandpa's brain, as if he could almost recall when he, a young soldier of the North, had taken his fill of sweet, black-seeded, carnation-tinted pulp at some plantation in the harried South. And now he ate greedily till the last prune was gone, when Johnnie had Buckle throw all of the green rinds into the sink. (It was this attention to detail which invested his games with reality.) Then, the repast finished, Grandpa fretted to be away, whirling his chair and whimpering.

Johnnie had eaten through a perfect menu only as an unfillable boy can. So he dismissed Buckle with a thousand-dollar bill, and the two travelers were off, Johnnie making a great deal of jolly noise as he fulfilled the duties of engineer, engine and conductor, Grandpa having nothing to do but be an appreciative passenger.

To the old man the dish cupboard, which was Carthage, in "York State," never lost its interest, he having lived in that town long years ago, before he marched out of it with a company of men who were bound for the War. But the morris chair with its greasy cushions, which was the capital, Albany, and the cookstove, which was very properly Pittsburgh (though the surface of the earth had to be wrenched about in order to put Pittsburgh after Albany on the way to "the Falls"), both of these estimable cities also won their share of attention, the special train bearing the pair making a stop at each, though the passengers,[22] boy and man, longed quite naturally for a sight of the Marvel of Waters which awaited them at the end of the line.

But Pittsburgh left behind, and Buffalo (the woodbox) all but grinding under their wheels, neither Grandpa nor Johnnie could withstand longer the temptation to push forward to wonderful Niagara itself. With loud hissings, toot-toots, and guttural announcements on the part of the conductor, the wheel chair drew up with a twisting flourish—at the sink.

And now came the most exciting moment of all. For here imagination had to be called upon least. This Niagara was liquid. And held back its vast flood—or poured it—just as Johnnie chose. He proceeded to have it pour. With Grandpa's cane, he rapped peremptorily twice—then once—on the big lead pipe which, leading through the ceiling as a vent to Mrs. Kukor's sink, debouched in turn into the Barber sink.

A moment's wait. Then some one began to cross the floor overhead with an astonishing sound of rocking yet with little advance—in the way that a walking doll goes forward. This was Mrs. Kukor herself, who was motherhood incarnate to Johnnie; motherhood boiled down into an unalloyed lump; the pure essence of it in a fat, round package. The little Jewish lady never objected to this regular morning interruption of her work. And so the next moment, the miracle happened. Lake Erie began to empty itself; and with splashes, gurgles and spurts, the cataract descended upon the pots and pans heaped in the Barber sink.

The downpour was greeted by a treble chorus of delight from the tourists. "Oh, Grandpa!" cried Johnnie, jumping up and down. "Ain't it fine! Ain't it fine!" And "Fine!" chimed in the old man, swaying himself against his breast rope. "Fine! Fine!"[23]

One long half-minute Niagara poured—before the admiring gaze of the two in the special. Then the great stream became dammed, the rush of its waters ceased, except for a weak trickle, and the ceiling gave down the sound of a rocking step bound away, followed by the squeaking of a chair. Mrs. Kukor was back at work.

The train returned silently to Pittsburgh, the Grand Army hat was taken off and hung in its place, the blanket was pulled up about Grandpa's shoulders, and this one of the pair of travelers was left to take his rest. Comfortable and swift as the whole journey was, nevertheless the feeble, old soldier was tired. His pale blue eyes were roving wearily; the chair at a standstill, down came their lids, and his head tipped sidewise.

He looked as much like a small, gray monkey as his strapping son resembled a gorilla. As Johnnie tucked the blanket about the thin old neck, Grandpa was already breathing regularly, the while he made the facial grimaces of a new-born child.[24]

JOHNNIE always started his own daily program with a taste of fresh air. He cared less for this way of spending his first fifteen free minutes than for many another. But as Cis, with her riper wisdom, had pointed out, a short airing was necessary to a boy who had no red in his cheeks, and too much blue at his temples—not to mention a pinched look about the nose. Johnnie regularly took a quarter of an hour out of doors.

He took it from the sill of the kitchen window—which was the only window in the Barber flat.

This sill was breast-high from the kitchen floor, Johnnie not being tall for his age. But having shoved up the lower sash with the aid of the broom handle, he did not climb to seat himself upon the ledge. For there was no iron fire escape outside; the nearest one came down the wall of the building to the kitchen window of the Gamboni family, to the left. And so Johnnie denied himself a perch on his sill—a dangerous position, as both Mrs. Kukor and Cis pointed out to him.

Their warnings were unnecessary. He could easily realize what a slip of the hand might mean: a plunge through space to the brick paving far below; and there an instant and horrible end. His picture of it was enough to guard him against accident. He contented himself with laying his body across the sill, with the longer and heavier portion of his small anatomy balanced securely against a shorter and lighter upper portion.[25]

He achieved this position and held it untiringly by the aid of the old rope coil. This coil was a relic of those distant times when there was no fire escape even outside the kitchen window of the Gambonis, and the landlord provided every tenant with this cruder means of flying the building. The rope hung on a large hook just under the Barber window, and was like a hard, smudged wheel, so completely had the years and the climate of the kitchen colored and stiffened it. And Johnnie's weight was not enough to elongate its set curves.

It was a handy affair. Using it as a stepping-place, and pulling himself up by his hands, he brought the lower end of his breastbone into contact with the sill. Resting thus, upon his midriff, he was thoroughly comfortable, due to the fact that Big Tom's shirt and trousers thoroughly padded his ribby front. Then he swelled his nostrils with his intaking of air, and his back heaved and fell, so that he was for all the world like some sort of a giant lizard, sunning itself on a rock.

Against the dingy black-red of the old wall, his yellow head stood forth as gaudily as a flower. The flower nodded, too, as if moved by the breeze that was wreathing the smoke over all the roofs. For Johnnie was taking a general survey of the scenery.

The Barber window looked north, and in front of it were the rear windows of tenements that faced on a street. There was a fire escape at every other one of these windows—the usual spidery affair of black-painted iron, clinging vinelike to the bricks. And over each escape were draped garments of every hue and kind, some freshly washed, and drying; others airing. Mingling with the apparel were blankets, quilts, mattresses, pillows and babies.

Somehow Johnnie did not like the view. He glanced down into the gloomy area, where a lean and untidy cat[26] was prowling, and where there sounded, echoing, the undistinguishable harangue of the fretful Italian janitress.

Now Johnnie's general survey was done. He always made it short, wasting less than one minute in looking down or around. It was beauty that drew him—beauty and whatever else could start up in his mind the experiences he most liked. His face upturned, one hand flung across his brows to shield his eyes, for the light outside the sill seemed dazzling after the semidark of the flat, he scanned first the opposite roof edges, a whole story higher than he, where sparrows were alighting, and where smoke plumes curled like veils of gossamer; next he scanned the sky.

Above the roofline of the tenements was a great, changing patch which he called his own, and which he found fascinating. And not only for what it actually showed him, which was splendid enough, but for the eternal promise of it. At any moment, what might not come slipping into sight!

What he longed most to catch sight of was—a stork. Those babies across on the fire escapes, storks had brought them (which was the main reason why all the families kept bedclothes out on the barred shelves; a quilt or a pillow made a soft place on which to leave a new baby). A stork had brought Cis—she had had her own mother's word for it many times before that mother died. A stork had brought Johnnie, too—and Grandpa, Mrs. Kukor, the Prince of Wales, the janitress; in fact, every one.

"I wonder what kind of a stork was it that fetched Big Tom!" Johnnie once had exclaimed, straightway visioning a black and forbidding bird.

Storks, according to Cis, were as bashful as they were clever, and did not come into sight if any one was watching. They were big enough to be seen easily, however, as[27] proven by this: frequently one of them came floating down with twins!

"Down from where?" Johnnie had wanted to know, liking to have his knowledge definite.

"From their nests, silly," Cis had returned. But had been forced to confess that she did not know where storks built their nests. "In Central Park, I guess," she had added. (Central Park was as good a place as any.)

"Oh, you guess!" Johnnie had returned, disgusted.

He had never given up his watching, nor his hope of some day seeing a big baby-bringer. He searched his sky patch now. But could see only the darting sparrows and, farther away, some larger birds that wheeled gracefully above the city. Many of these were seagulls. The others were pigeons, and Cis had told him that people ate them. This fact hurt him, and he tried not to think about it, but only of their flight. He envied them their freedom in the vast milkiness, their power to penetrate it. Beyond the large birds, and surely as far away as the sun ever was, some great, puffy clouds of a blinding white were shouldering one another as they sailed northward.

Out of the wisdom possessed by one of her advanced age, Cis had told him several astonishing things about this field of sky. What Barber considered a troublesome, meddlesome, wasteful school law was, at bottom, responsible for her knowing much that was true and considerable which Johnnie held was not. And one of her unbelievable statements (this from his standpoint) was to the effect that his sky patch was constantly changing,—yes, as frequently as every minute—because the earth was steadily moving. And she had added the horrifying declaration that this movement was in the nature of a spin, so that, at night, the whole of New York City, including skyscrapers, bridges, water, streets, vehicles and population, was upside down in the air[28]!

"Aw, it ain't so!" he cried, though Cis reminded him (and rather sternly, for her) that in doing so he was questioning a teacher who drew a magnificent salary for spreading just such statements. "And if they pay her all that money, they're crazy! Don't y' know that if we was t' come upside down, the chimnies'd fall off all the buildin's? and East River'd spill?"

Cis countered with a demonstration. She filled Big Tom's lunch pail with water and whirled it, losing not a drop.

But he went further, and proved her wrong—that is so far as the upside-down of it was concerned. He did this by staying awake the whole of the following night and noting that the city stayed right-side up throughout the long hours. Cis, poor girl, had been pitifully misinformed.

But the changing of the sky he believed. He believed it because at night there was the kind of sky overhead that had stars in it; also, sometimes, a moon. But by dawn, the starred sky was gone—been left behind, or got slipped to one side; in its place was a plain, unpatterned stretch of Heaven which, in due time, was once more succeeded by a firmament adorned and a-twinkle.

When Cis returned home one evening and declared that the forewoman at the factory had asserted that there were stars everywhere in the sky by day as well as by night, and no plain spots at all anywhere; and, further, that if anybody were at the bottom of a deep well he—or she—could see stars in the sky in the daytime, Johnnie had fairly hooted at the tale. And had finally won Cis over to his side.

Her last doubt fled when, having gone down into a dark corner of the area the Sunday following, she found, as did he, that no stars were to be seen anywhere. After that she believed in his theory of starless sky-spots; starless, but not plain. For in addition to the sun, many other[29] things lent interest to that field of blue—clouds, rain, sleet, snow, and fog, all in their time or season. Also, besides the birds, he occasionally glimpsed whole sheets of newspapers as they ambitiously voyaged above the house tops. And how he longed for them to blow against his own window, so that he might read them through and through!

Sometimes he saw a flying machine. The first one that had floated across his sky had very nearly been the death of him. Because, forgetting danger in his rapturous excitement, he had leaned out dangerously, and might have fallen if he had not suddenly thought of Grandpa, and thrown himself backward into the kitchen to fetch the wheel chair. The little old soldier had only been mildly diverted by the sight. Johnnie, however, had viewed the passing of the biplane in amaze, though later on he came to accept the conquest of the air as just one more marvel in a world of marvels.

But his wonder in the sky itself never lessened. About its width he did not ponder, never having seen more than a narrow portion of it since he was big enough to do much thinking. But, oh, the depth of it! He could see no sign of a limit to that, and Mrs. Kukor declared there was none, but that it reached on and on and on and on! To what? Just to more of the on and on. It never stopped.

One night Cis and he, bent over the lip of the window, she upholstered on a certain excelsior-filled pillow which was very dear to her, and he padded by Big Tom's cast-offs, had attempted to realize what Mrs. Kukor had said. "On—and on—and on—and on," they had murmured. Until finally just the trying to comprehend it had become overpowering, terrible. Cis declared that if they kept at it she would certainly become dizzy and fall out. And so they had stopped.

But Johnnie was not afraid to think about it, awful as[30] it was. It was at night, mostly, that he did his thinking. At night the birds he loved were all asleep. But so was Barber; and Johnnie, with no fear of interruption, could separate himself from the world, could mentally kick it away from under him, and lightly project his thin little body up to the stars.

Whenever fog or clouds screened the sky patch, hiding the stars, a radiance was thrown upon the heavens by the combined lights of the city—a radiance which, Johnnie thought, came from above; and he was always half expecting a strange moon to come pushing through the cloud screen, or a new sun, or a premature dawn!

Now looking up into the deep blue he murmured, "On—and—on—and on," to himself. And he wondered if the gulls or the pigeons ever went so far into the blue that they lost their way, and never came back—but just flew, and flew, and flew, till weariness overcame them, when they dropped, and dropped, and dropped, and dropped!

A window went up in front of him, across the area, and a voice began to call at him mockingly: "Girl's hair! Girl's hair! All he's got is girl's hair! All he's got is girl's hair!"

He started back as if from a blow. Then reaching a quick hand to the sash, he closed the window and stepped down.

The voice belonged to a boy who had once charged Mrs. Kukor with going to church on a Saturday. But even as Johnnie left the sill he felt no anger toward the boy save on Mrs. Kukor's account. Because he knew that his hair was like a girl's. If the boy criticized it, that was no more than Johnnie constantly did himself.

The second his feet touched the splintery floor he made toward the table, caught up the teapot, went to lean his head over the sink, and poured upon his offending locks the whole remaining contents of the pot—leaves and all.[31] For Cis (that mine of wisdom) had told him that tea was darkening in its effect, not only upon the lining of the tummy, which was an interesting thought, but upon hair. And while he did not care what color he was inside, darker hair he longed to possess. So, his bright tangles a-drip, he set the teapot in among the unwashed pans and fell to rubbing the tea into his scalp.

And now at last he was ready to begin the really important matters of the day.

But just which of many should he choose for his start? He stood still for a moment, considering, and a look came into his face that was all pure radiance.

High in the old crumbling building, as cut off from the world about him as if he were stranded with Grandpa on some mountain top, he did not fret about being shut in and away; he was glad of it. He was spared the taunts of boys who did not like his hair or his clothes; but also he had the whole flat to himself. Day after day there was no one to make him do this, or stop his doing that. He could handle what he liked, dig around in any corner or box, eat when he wished. Most important of all, he could think what he pleased!

He never dwelt for any length of time upon unhappy pictures—those which had in them hate or revenge. His brain busied itself usually with places and people and events which brought him happiness.

For instance, how he could travel! And all for nothing! His calloused feet tucked round the legs of the kitchen chair, his body relaxed, his expression as rapt as any Buddhist priest's, his big hands locked about his knees, and his eyes fastened upon a spot on the wall, he could forsake the Barber flat, could go forth, as if out of his own body, to visit any number of wonderful lands which lay so near that he could cross their borders in a moment. He could sail vast East Rivers in marvelous tugs. He[32] could fly superbly over great cities in his own aeroplane.

And all this travel brought him into contact with just the sort of men and women he wanted to know, so politely kind, so interesting. They never tired of him, nor he of them. He was with them when he wanted to be—instantly. Or they came to the flat in the friendliest way. And when its unpleasant duties claimed him—the Monday wash, the Tuesday ironing, the Saturday scrubbing, or the regular everyday jobs such as dishes, beds, cooking, bead-stringing, and violet-making—frequently they helped him, lightening his work with their charming companionship, stimulating him with their example and praise.

Oh, they were just perfect!

And how quiet, every one of them! So often when the longshoreman returned of an evening, his bloodshot eyes roving suspiciously, a crowd of handsomely dressed people filled the kitchen, and he threaded that crowd, yet never guessed! When Big Tom spoke, the room usually cleared; but later on Johnnie could again summon all with no trouble whatever, whether they were great soldiers or presidents, kings or millionaires.

Of the latter he was especially fond; in particular, of a certain four. And as he paused now to decide upon his program, he thought of that quartet. Why not give them a call on the telephone this morning?

He headed for the morris chair. Under its soiled seat-cushion was a ragged copy of the New York telephone directory, which just nicely filled in the sag between the cushion and the bottom of the chair. He took the directory out—as carefully as if it were some volume not possible of duplication.

It was his only book. Once, while Cis was still attending school, he had shared her speller and her arithmetic, and made them forever his own (though he did not realize it yet) by the simple method of photographing each on[33] his brain—page by page. And it was lucky that he did; for when Cis's brief schooldays came to an end, Big Tom took the two textbooks out with him one morning and sold them.

The directory was the prized gift of Mrs. Kukor's daughter, Mrs. Reisenberger, who was married to a pawnbroker, very rich, and who occupied an apartment (not a flat)—very fine, very expensive—in a great Lexington Avenue building that had an elevator, and a uniformed black elevator man, very stylish. The directory meant more to Johnnie than ever had Cis's books. He knew its small-typed pages from end to end. Among the splendid things it advertised, front, back, and at the bottom of its pages, were many he admired. And he owned these whenever he felt like it, whether automobiles or animals, cash registers or eyeglasses. But such possessions, fine as they were, took second place in his interest. What thrilled him was the list of subscribers—the living, breathing thousands that waited his call at the other end of a wire! And what people they were!—the world-celebrated, the fabulously wealthy, the famously beautiful (as Cis herself declared), and the socially elect!

Of course there was still others who were prominent, such as storekeepers, prize fighters, hotel owners and the like (again it was Cis who furnished the data). But Johnnie, as has been seen, aimed high always; and he was particular in the matter of his telephonic associations. Except when shopping, he made a strict rule to ring up only the most superior.

There was a clothesline strung down the whole length of the kitchen. This Johnnie lowered on a washday to his own easy reach. At other times it was raised out of the way of Big Tom's head.

He let the line down. Then pushing the kitchen chair to that end of the rope which was farthest from the stove[34] and the sleeping old man, he stood upon it; and having considered a moment whether he would first call up Mr. Astor, or Mr. Vanderbilt, or Mr. Carnegie, or Mr. Rockefeller, decided upon Mr. Astor, and gave a number to a priceless Central who was promptness itself, who never rang the wrong bell, or reported a busy wire, or cut him off in the midst of an engrossing conversation.

This morning, as usual, he got his number at once. "Good-mornin', Mister Astor!" he hailed breezily. "This is Johnnie Smith.—'Oh, good-mornin', Mister Smith! How are y'?'—I'm fine!—'That's fine!'—How are you, Mister Astor?—'Oh, I'm fine.'—That's fine!—'I was just wonderin', Mister Smith, if you would like to go out ridin' with me.'—Yes, I would, Mister Astor. I think it'd be fine!—'Y' would? Well, that's fine! And, Mister Smith, I'll come by for y' in about ten minutes. And if ye'd like to take a friend along——'"

There now followed, despite the appointment set for so early a moment, a long and confidential exchange of views on a variety of subjects. When this was finished, Johnnie rang, in turn, Messrs. Vanderbilt, Carnegie and Rockefeller, sparing these gentlemen all the time in the world. (When any one of them did indeed call for him, fulfilling an appointment, what a gorgeous blue plush hat the millionaire wore! and what a royally fur-collared coat!)

Now Johnnie put aside the important engagement he had made with Mr. Astor, and, being careful first to find the right numbers in the book, got in touch with numerous large concerns, and ordered jewelry, bicycles, limousines, steam boilers and paper drinking cups with magnificent lavishness.

He had finished ordering his tenth automobile, which was to be done up in red velvet to match the faithful Buckle, when there fell upon his quick ear the sound of a step. In the next instant he let go of the clothesline, sent[35] the telephone book slipping from the chair at his feet, and plunged like a swimmer toward that loose ball of gingham under the sink.

And not a moment too soon; for scarcely had he tossed the tied strings over his tea-leaf-sprinkled hair, when the door opened, and there, coat on arm, great chest heaving from his climb, bulgy eyes darting to mark the condition of the flat, stood—Barber![36]

IT WAS an awful moment.

During that moment there was dead silence. Johnnie's heart stopped beating, his ears sang, his throat knotted as if paralyzed, and the skin on the back of his head crinkled; while in all those uneven thickets of his tawny, tea-stained hair, small, dreadful winds stirred, and he seemed to lift—horribly—away from the floor.

Also, a sickish, sinking feeling at the lower end of his breastbone made him certain that he was about to break in two; and a sudden wobbling of the knees threatened to bring him down upon them.

Barber closed the hall door at his back—gently, so as not to waken his father. His eyes were still roving the kitchen appraisingly. It was plain that the full sink and the littered table were having their effect upon him; for he had begun that chewing on nothing which betokened a rising temper.

Johnnie saw, but he was too stunned and scared to think of any way out of his difficulty. He might have caught up the big cooking spoon and rapped on that lead pipe—five times in rapid succession, as if he were trying to clear the spoon of the cereal clinging to its bowl. The five raps was a signal that he had not used for a long time. It belonged to that dreadful era to which Cis and he referred as "before the saloons shut up." Preceding the miracle that had brought the closing of these, Barber,[37] returning home from his day's work, had needed no excuse for using the strap or his boot upon either of the children. And once he had struck helpless old Grandpa—a happening remembered by Cis and Johnnie with awesome horror, so that they spoke of it as they spoke of the Great War, or of a murder in the next block.

It had not been possible in those days for Big Tom to overlook the temptation of drink. To arrive at his own door from any direction he had to pass saloons. At both of the nearest street crossings northward, three of the four corners had been occupied by drinking places. There were two at each of the street crossings to the south. In those now distant times, the signal, and Mrs. Kukor's prompt answering of it, had often saved Cis and Johnnie from drunken beatings.

But now the boy sent no signal. Those big-girl's hands were shaking in spite of all effort to control. His upturned face was a ghastly sallow. The gray eyes were set.

Barber's survey of the room finished, he stepped across the sagging telephone line, placed the cargo hook and his lunch pail on the untidy table, and squared round upon Johnnie.

"Now, say!"

"Yes?" It was a whisper.

"What y' done in here since I left two hours ago?"

Johnnie drew a quick breath. He was not given to falsehood, but he did at times depend upon evasion—at such times as this. And not unnaturally. For he was in the absolute power of a bully five times his own size—a bully who was none the less cruel because he argued that he was disciplining the boy properly, bringing him up "right." Discipline or not, Big Tom did not know the meaning of mercy; and to Johnnie the blow of one of those great gorillalike fists was like some cataclysm of nature.

"What y' done?" persisted Barber, but speaking low,[38] so as not to disturb the sleeper in the wheel chair. He leaned down toward Johnnie, and thrust out that lower lip.

The boy's own lips began to move, stiffly. But he spoke as if he were out of breath. "Grandpa f-f-fretted," he stammered. "He—he wanted to be run up and down—with his hat on. And—and so I filled the m-m-mush-kettle t' soak it, and then we—we——"

His lips went on moving; but his words became inaudible. A smile was twisting Barber's mouth, and carrying that crooked, cavernous nose sidewise. Johnnie understood the smile. The fringe about his thin arms and legs began to tremble. He raised both hands toward the longshoreman, the palms outward, in a gesture that was like a silent prayer.

With a muttered curse, Barber straightened, turned on his heel, strode to the door of his bedroom, threw it wide, noted the unmade beds, and came about, pushing at the sleeve of his right arm. "Come here," he bade, and the quiet of his tone was more terrible to the boy than if he had shouted.

Johnnie did not obey. He could not. His legs would not move. His feet were rooted. "Oh, Mister Barber," he pleaded. "Oh, don't lick me! I won't never do it again! Oh, don't! Oh, don't! Oh, don't!"

"Come here." The great arm was bared now. The voice was lower than before. In one bulging, bloodshot eye that cast showed and went, then showed again. "Do what I say—come here."

"Oh! oh! oh!" Again Johnnie was gasping.

Barber burst out at him like some fierce storm. "Don't y' try t' fool me!" he cried. He came on. When he was within reach, that great, naked, iron arm shot out, seized the boy at his middle, swept him up from the floor with a violence that sent the tea leaves flying from the yellow hair, held him for a second in mid-air, the small body[39] slouched in the big clothes as in the bottom of a sack, then shook him till he fairly rattled, like a pea in a pod.

In a terror that was uncontrollable, Johnnie began to thrash about and scream. And as Barber half dropped, half flung him to the floor, old Grandpa roused, and came round in his chair, tap-tapping with the cane. "Captain!" he shrilled. "The right's falling back! They're giving us grape and canister!—Oh, our boys! Our poor boys!" Frightened by any trouble, his mind always reverted to old scenes of battle, when his broken sentences were like a halting, squeaky record in some talking machine that is out of order and running down.

As Grandpa rolled near to Johnnie, the latter caught at a wheel, seeking help, in his extremity, of the helpless, and thrust his hands through the spokes to lock them. So that as Barber once more bent and dragged at him, the chair and the old man followed about the kitchen.

"Let go!" commanded the longshoreman. He tried to shake Johnnie free of the wheel.

But Johnnie held on, and his cries redoubled. The kitchen was in a tumult now, for old Grandpa was also weeping—not only in fear for Johnnie, but in terror lest he himself be overturned. And Big Tom was alternately cursing and ordering.

The trouble was heard elsewhere. To right and left there was movement, and the sound of windows being raised. Voices called out questioningly. Some one pounded on a wall in protest. And overhead Mrs. Kukor left her chair and went rocking across her floor.

Muttering a savage exclamation, Big Tom let go of the boy and flung himself into the morris chair, not wanting to go so far with his punishment as to invite the complaints of his neighbors and the interference of the police. "Git up out of that!" he commanded, giving Johnnie a rough nudge with a foot; then to quiet his father, "Now, Pa![40] That'll do. Sh! sh! It's all right. The battle's over, and the Yanks've beat."

But Johnnie was still prone, with the wheel in his embrace, and the old veteran was sobbing, his wrinkled face glistening with tears, when Mrs. Kukor opened the door and came doll-walking in.

She was a short little lady, with a compact, inflexible figure that was, so to speak, square, with rounded-off corners—square, and solid, and heavy. She had eyes that were as black and round and bright as a sparrow's, a full, red mouth, and graying hair, abundant and crinkly, which stood out around her countenance as if charged with electricity. It escaped the hairpins. Even a knitted brown cap of some weight did not adequately confine it. Every hair seemed vividly alive.

Her olive face was a trifle pale now. Her birdlike eyes darted from one to another of the trio, quickly taking in the situation. Too concerned to make any apology for her unannounced entrance, she teetered hastily to Big Tom's side.

"Oy! oy!" she breathed anxiously. "Vot iss?"

"Tommie home," faltered old Grandpa. "Tommie home. And the color sergeant's dead!" He reached his arms out to her like a frightened child who welcomes company.

Like her eyes, Mrs. Kukor's lips never rested, going even when she listened, for she had the habit of silently repeating whatever was said. Thus, with lips and eyes busy, head alternately wagging and nodding eloquently, and both hands waving, she was constantly in motion. Now, "The color sergeant's dead!" her mouth framed, and she gave a swift glance around almost as if she expected to see a fallen flag bearer.

"It's this lazy little rascal again," declared Barber, working his jaws in baffled wrath.

"So-o-o-o!" She stooped and laid a gentle hand on[41] Johnnie's shoulder. "Come," she said. "Better Chonnie, he goes in a liddle by Cis's room. No?" And as the boy, still trembling, got to his knees beside the chair, she helped him to rise, and half led, half carried him past the stove.

Barber began his defense. "I go out o' here of a mornin'," he complained, "to do a hard day's work, so's I can pay rent and the grocer. I leave that kid t' do a few little things 'round the place. And the minute my back's turned, what does he do? Nothin'! I come back, and look!"

Mrs. Kukor, having seen Johnnie out of the room, turned about. Then, smoothing her checked apron with her plump hands, she glanced at Barber with a deprecating smile. "I haf look," she answered. "Und I know. But—he wass yust a poy, und you know poys."

"I know boys have t' work," came back Barber, righteously. "If they don't, they grow up into no-account men. When his Aunt Sophie died, I promised her I'd raise him right. The work here don't amount to nothin',—anyhow not if you compare it with what I done when I was a boy. Why, on my father's farm, up-state, I was out of my bed before sunup, winter and summer, doin' chores, milkin', waterin' the stock, hoein', and so on. What's a few dishes to that? What's a bed or two? and a little sweepin'? And look! He ain't even washed the old man yet! And I like to see my father clean and neat. That's what makes me so red-hot, Mrs. Kukor—the way he neglects my father."

"Chonnie wass shut up so much," argued Mrs. Kukor.

That cast whitened Big Tom's eye anxiously. He did not want Johnnie to hear any talk about going out. He hastened to reply, and his tone was more righteous than ever. "No kid out of this flat is goin' to run the streets," he declared, "and learn all kinds of bad, and bring it home to that nice, little stepdaughter o' mine! No, Mrs. Kukor,[42] her mother'd haunt me if I didn't bring her up nice, and you can bet I'll do that. That kid, long's he stays under my roof, is goin' t' be fit t' stay. And he wouldn't be if he gadded the streets with the gangs in this part of town." While this excuse for keeping Johnnie indoors was anything but the correct one, Big Tom was able to make his voice fervent.

"But Chonnie wass tired mit always seeink the kitchen," persisted the little Jewish lady. "He did-ent go out now for a lo-ong times. I got surprises he ain't crazy!"

"That's just what he is!" cried Big Tom, triumphantly. "He's crazy! Of all the foolishness in the world, he can think it up! And the things he does!—but nothin' that'll ever git him anywheres, or do him any good! And lazy? Anything t' kill time—t' git out of honest work! Now what d'y' suppose he was doin' with this clothes line down? and talkin' out loud to himself?"

"Niaggery! Niaggery!" piped old Grandpa, smiling through his tears, and swaying against the rope that crossed his chest. "Niaggery! Niaggery! Chug! chug! chug!"

Mrs. Kukor spread out both hands in a comprehensive gesture. "See?" she asked. "Oh, I haf listen. The chair goes roundt and roundt, und much water wass runnink in the sink. It wass for Grandpa, und—it takes time."

Barber's dark face relaxed a little. It could not truthfully be said of him that he was a bad son; and any excuse that offered his father as its reason invariably softened him. He pulled himself to his feet and picked up the lunch pail and the cargo hook. "Well—all right," he conceded. "But I said t' myself, 'I'll bet that kid ain't workin'.' So havin' a' hour, I come home t' see. And how'd he git on yesterday, makin' vi'lets for y'?"

"Ach!"—this, an exclamation of impatience, was aimed at herself. "I wass forgettink!" Under her apron hung[43] a long, slender, black bag. Out of it she took a twenty-five-cent piece and offered the coin to Barber. "For yesttady," she added.

"Thank y'." He took the quarter. "Glad the kid done his work."

"Oh, sure he do!" protested Mrs. Kukor. "Pos-i-tiv-vle!" (Mrs. Kukor could also be guilty of self-deception.)

Now, Barber raised his voice a little: "Johnnie, let's see how quick you can straighten this place up."

At that, Mrs. Kukor waved both hands in eloquent signals, urging Big Tom to go; tapped her chest, winked, and made little clicking noises with her tongue—all to denote the fact that she would see everything straightened up to perfection, but that for old Grandpa's sake further conversation with Johnnie might be a mistake, since weeping all around would surely break out again. So Barber, muttering something about leaving her a clear coast, scuffed his way out.

As the hall door closed, Johnnie buried his small nose in Cis's pillow. He was wounded in pride rather than in body. He hated to be found on the floor at the toe of Big Tom's boot. He had listened to the conversation while lying face downward on Cis's bed but with his head raised like a turtle's. However, it seemed best, somehow, not to be found in that position by Mrs. Kukor. He must not take his ill-treatment lightly, nor recover from his hurts too quick. He decided to be prone and prostrated. When the little Jewish lady came swaying in to him, therefore, he was stretched flat, his yellow head motionless.

The sight smote Mrs. Kukor. In all the five years he had lived at the Barber flat, she had continually watched over him, plying him with medicine, pulling his baby teeth, mending his ragged clothes, teaching him to cook and do[44] housework, feeding him kosher dainties, and—for reasons better hinted at than made plain—keeping a sharp lookout in the matter of his bright hair.

In the beginning, when trouble had assailed him, her lap had received him like the mother's lap he could not remember; her arms had cradled him tenderly, her kisses had comforted, and he had often wept out his rage and mortification on her bosom.

However, long since he had felt himself too big to be held or kissed. And as for his hair, she understood what a delicate subject it had come to be with him. She would have liked to stroke it now; but she contented herself with patting gently one thin arm. Behind her was old Grandpa, peering into the dim closet.

"Oy! oy! oy!" mourned Mrs. Kukor, wagging her round head. "Ev'rytink goes bat if some peoples lives by oder peoples w'ich did-ent belonk mit. Und how to do? I can't to say, except yust live alonk, und see if sometink nice happens maype."

Johnnie moved, with a long, dry sob, and very tenderly she leaned down to turn his face toward her. "Ach, poor Chonnie!" she cried. "Come! We will wash him, und makes him all fresh und clean. Und next—how do you t'ink? Mrs. Kukor hass for you a big surprises!"

He sat up then, wearily, but forbore to seem curious, and she coaxed him into the kitchen, to bathe the dust and tears from his countenance, and stitch up some rents in the big shirt, where Big Tom had torn it. All the while she talked to him comfortingly. "Ach, mine heart it bleets over you!" she declared. "But nefer mind. Because, oh, such swell surprises!"

Now Johnnie felt he could properly show interest in things outside the morning's trouble. "What, Mrs. Kukor?" he wanted to know. "Is it—is it noodle soup?"[45]

And now both burst out laughing, for it was always a great joke between them, his liking for her noodle soup. Old Grandpa laughed loudest of all, circling them, and pounding the floor with his cane. "What say?" he demanded. "What say?" Altogether the restoration to the flat of peace and happiness was made so evident that, to right, left, and below, windows now began to go down with a bang, as, the Barber row over, the neighbors went back to their own affairs.

"It wass not noodle soup," declared Mrs. Kukor. "It wass sometink a t'ousand times so goot. But not for eatink. No. Much better as. Und! Sooner your work wass finished, make a signals to me alonk of the sink, und see how it happens!"

More she would not say, but rocked out and up.

Johnnie went at his dishes hard. The table cleared, the sink empty, and the cupboard full, he tied the clothesline out of the way, then with broom and dustpan invaded Big Tom's bedroom, which Grandpa shared with his hulking son. Here were two narrow, iron bedsteads. Between them was barely room for the wheel chair when it rolled the little old man in to his night's rest. To right and left of the door, high up, several nails supported a few dusty garments. That was all.

If Johnnie stooped in the doorway of this room, he could see every square foot of its floor, and every article in it. Yet from the very first he had feared the place, into which no light and air came direct. Whenever he swept it and made the beds, his heart beat fast, and he felt nervous concerning his ankles, as if Something were on the point of seizing them! For this reason he always put off his bedroom work as long as he could; then finished it up quickly, keeping the door wide while he worked. At other times, he kept it tight shut. Often when old Grandpa was[46] asleep by the stove, Johnnie would tiptoe to that door, lean against the jamb of it, and listen. And he told Cis that he could plainly hear creakings!

But this morning he felt none of his usual nervousness, so taken up was his mind with Mrs. Kukor's mystery. Swiftly but carefully he made the two beds. As a rule, he contented himself with straightening each out, but so artfully that Barber would think the sheets had been turned. Sometimes Barber threw a bit of paper or a sock into one bed or the other, in order to trap Johnnie, who found it wise always to search for evidence.