The Project Gutenberg EBook of Ran Away to Sea, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Ran Away to Sea

Author: Mayne Reid

Release Date: December 13, 2007 [EBook #23853]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RAN AWAY TO SEA ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"Ran Away to Sea"

Chapter One.

I was just sixteen when I ran away to sea.

I did not do so because I had been treated unkindly at home. On the contrary, I left behind me a fond and indulgent father, a kind and gentle mother, sisters and brothers who loved me, and who lamented for me long after I was gone.

But no one had more cause to regret this act of filial disobedience than I myself. I soon repented of what I had done, and often, in after life, did it give me pain, when I reflected upon the pain I had caused to my kindred and friends.

From my earliest years I had a longing for the sea—perhaps not so much to be a sailor, as to travel over the great ocean, and behold its wonders. This longing seemed to be part of my nature, for my parents gave no encouragement to such a disposition. On the contrary, they did all in their power to beget within me a dislike for a sea life, as my father had designed for me a far different profession. But the counsels of my father, and the entreaties of my mother all proved unavailing. Indeed—and I feel shame in acknowledging it—they produced an effect directly opposite to that which was intended; and, instead of lessening my inclination to wander abroad, they only rendered me more eager to carry out that design! It is often so with obstinate natures, and I fear that, when a boy, mine was too much of this character. Most to desire that which is most forbidden, is a common failing of mankind; and in doing this, I was perhaps not so unlike others.

Certain it is, that the thing which my parents least desired me to feel an interest in—the great salt sea—was the very object upon which my mind constantly dwelt—the object of all my longings and aspirations.

I cannot tell what first imbued me with a liking for the sea, for I had such a liking almost from the years of childhood. I was born upon the sea-shore, and this fact might explain it; for, during my early life, when I was still but a mere child, I used to sit at the window and look with admiring eyes on the boats with their white sails, and the beautiful ships with their tall tapering masts, that were constantly passing and repassing. How could I do otherwise than admire these grand and glorious structures—so strong and so graceful? How could it be otherwise, than that I should imbibe a longing to be on board of them, and be carried afar over yonder bright blue water?

As I grew older, certain books had chanced to fall into my hands, and these related to the sea—they told of lovely lands that lay upon its shores—of strange races of men and animals—of singular plants and trees—of palms and broad-leaved figs—of the banyan and the baobab—of many things beautiful and wonderful. These books strengthened the inclination I already felt to wander abroad over the ocean.

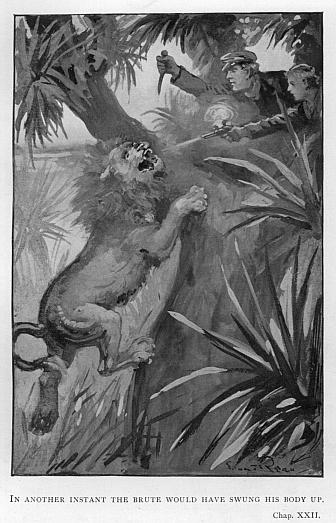

Another circumstance aided in bringing about the climax. I had an uncle who had been an old skipper—that is, the master of a merchant-ship—and it was the delight of this old gentleman to assemble his nephews around him—there was a goodly number of us—and tell us tales of the sea, to which all were ever eager to listen. Many a budget did he deliver by the winter fireside—for, like the storyteller of the “Arabian Nights,” a thousand and one tales could he tell—stories of desperate adventures by flood and field—of storms, hurricanes, and shipwrecks—long voyages in open boats—encounters with pirates and Indians—battles with sharks, and seals, and whales bigger than houses—terrible conflicts with wild beasts—as bears, wolves, lions, and tigers! All these adventures had our old uncle encountered, or said he had, which to his admiring audience was pretty much the same thing.

After listening to such thrilling narrations, no wonder I became tired of home, no wonder my natural inclination grew into a passion I could no longer resist. No wonder I ran away to sea.

And I did so at the age of sixteen—the wonder is I did not go sooner, but it was no fault of mine that I did not; for from the time I was able to talk I had been constantly importuning my parents for leave to go. I knew they could easily have found a situation for me, had they been so minded. They could have bound me as an apprentice on board some of the great merchant vessels sailing for India, or they could have entered me in the Royal Navy as a midshipman, for they were not without high interest; but neither father nor mother would lend an ear to my entreaties.

At length, convinced they would never consent, I resolved upon running away; and, from the age of fourteen, had repeatedly offered myself on board the ships that traded to the neighbouring seaport, but I was too small a boy, and none of them would take me. Some of the captains refused because they knew I had not the consent of my parents; and these were the very kind with whom I should have preferred going; since the fact of their being such conscientious men, would have ensured me good treatment. But as these refused to take me I had no other resource but to try elsewhere, and I at length succeeded in striking a bargain with a skipper who had no scruples about the matter, and I was booked as an apprentice. He knew I was about to run away; and more than this, assisted in the design by letting me know the exact day and hour he was to take his departure from the port.

And I was aboard at the time specified; and before any search could have been made for me, or even before I could have been missed, the vessel had tripped her anchor, spread her sails, and carried me off beyond the possibility of pursuit.

Chapter Two.

I was not twelve hours on board—twelve minutes I might almost say—before I was completely cured of my sea fever; and I would have parted with the best tooth in my head to have set my legs once more on land again. Almost on embarking I was overhauled by sea-sickness, and in another hour it became so bad that I thought it would have turned me inside out.

Sea-sickness is a malady not pleasant under any circumstances—even to a first-cabin passenger, with a steward to wait upon him, and administer soothing prescriptions and consoling sympathy. How much more painful to a poor friendless boy treated as I was—sworn at by the surly captain—cursed and cuffed by the brutal mate—jeered and laughed at by the ruffian crew. Oh! it was horrid, and had the ship been sinking under me at that moment I verily believe I should not have made the slightest effort to save myself!

Forty-eight hours, however, gave me relief from the nauseous ailing, for this like many other diseases is often short-lived where it is most violent. In about two days I was able to stand up and move about the decks, and I was made to move about them with a vengeance.

I have above characterised the captain as “surly,” the mate “brutal,” and the crew a set of “ruffians”: I have spoken without exaggeration. With an exception or two, a more villainous gang I never encountered—of course not before that time—for that was not likely; but never since either, and it has several times been the fortune of my life to mix in very questionable and miscellaneous company.

The captain was not only surly, but positively ferocious when drunk or angry, and one or both he generally was. It was dangerous to go near him—at least for me, or any one that was weak and helpless—for it was chiefly upon the unresisting that he ventured his ill-humour.

I was not long on board before I incurred his displeasure by some mistake I could not possibly help—I had a taste of his temper then, and many a one afterwards, for his spite once kindled against anyone was implacable as the hate of a Corsican, and never became allayed.

He was a short, stout, “bluffy” man, with features perfectly regular, but with fat round cheeks, bullet eyes, and nose slightly upturned—a face which is often employed in pictures to typify good-nature, jollity, and an honest heart; but with little propriety is it so employed in my opinion, since under just such smiling faces have I, during a long life’s experience, encountered the greatest amount of dishonesty combined with dispositions most cruel and brutal. Such a man was the skipper into whose tender care I had so recklessly thrown myself.

The mate was an echo of his captain. When the one said “no” the other said “no,” and when either said “yes,” the other affirmed it. The principal difference between them was that the mate did not drink, and perhaps this lengthened, if it did not strengthen, the bond of friendship that existed between them. Had both been drinkers they must have quarrelled at times; but the mate never “tasted” as he affirmed, and when his superior was in his cups this enabled him to bear the abuse which not unfrequently the captain treated him to. In all matters of discipline, or of anything else, he was with the captain, for though brutal he was but a cowardly fellow and ever ready to fawn upon his master, “boot-lick” him as the sailors termed it.

There was a second mate, but this was a very secondary kind of a character, not worth description, and scarcely to be distinguished from the common “hands” over whom he exercised only a very limited control.

There was a carpenter, an old man with a large swollen rum-reddened nose, another crony of the captain’s; and a huge and very ugly negro, who was both cook and steward, and who was vile enough to have held office in the kitchen of Pluto. These were the officers of the ship, and for the men, they were, as already stated, as villainous a crew as I ever encountered. There were exceptions—only one or two,—but it was some time before I discovered them.

In such companionship then did I find myself—I just fresh from the tender protection of parents—from the company of kind friends, and associates. Oh! I was well cured of the sea fever, and would have given half my life to be on land again! How I reproached myself for my folly! How I reproached that friend of the family—the old salt—whose visionary adventures had no doubt been the cause of my sea longings! how in my heart I now execrated both him, and his fanciful stories! Would I had never heard them! would that I had never run away to sea!

Repentance had arrived too late to be of any use. I could no longer return—I must go on, and how long? merciful heaven, the prospect was horrible! Months of my painful life were to be endured. Months! nay years,—for I now remembered that the wretch of a captain had caused me to sign some agreement—I had not even read it, but I knew it was an article of indenture; and I was told afterwards that it bound me for years—for five long years—bound me not an apprentice but in reality a slave. A slave for five years to this hideous brute, who might scold me at will, cuff me at will, kick me at will, have me flogged or put in irons whenever the fancy crossed his mind.

There was no retreating from these hard conditions. Filled with bright visions of “life on the ocean wave,” I had subscribed to them without pause or thought. My name was down, and I was legally bound. So they told me both captain and mate, and I believed it.

I could not escape, no matter how severe the treatment. Should I attempt to run away from the ship, it would be desertion. I could be brought back and punished for it. Even in a foreign port the chances of desertion would be no better, but worse, since there the sailor finds it more difficult to conceal himself. I had no hope then of escaping from the cruel thrall in which I now found myself, but by putting an end to my existence, either by jumping into the sea or hanging myself from the yard-arm—a purpose which on more than one occasion I seriously entertained; but from which I was diverted by the religious teachings of my youth, now remembered in the midst of my misery.

It would be impossible for me to detail the number of cruelties and indignities to which I was forced to submit. My existence was a series of both.

Even my sleep, if sleep it could be called, I was not allowed to enjoy. I possessed neither mattress nor hammock, for I had come aboard in my common wearing clothes—in my school-jacket and cap—without either money in my pocket or luggage in my hands. I had not even the usual equipments of a runaway—the kerchief bundle and stick; I possessed absolutely nothing—much less a mattress or hammock. Such things a skipper does not find for his crew, and of course there was none for me. I was not even allowed a “bunk” to sleep in, for the forecastle was crowded and most of the bunks carried double. Those that were occupied by only one chanced to have for their tenants the most morose and ill-natured of the crew, and I was not permitted to share with them. Even still more inhospitable were these fiends—for I cannot help calling them so when I look back on what I suffered at their hands—I was not even allowed to lie upon their great chests, a row of which extended around the forecastle, in front of the respective bunks, and covered nearly the whole space of the floor. The floor itself did not leave room for me to lie down—besides it was often wet by dirty water being spilled upon it, or from the daily “swabbing” it usually received. The only place I could rest—with some slight chance of being left undisturbed—was in some corner upon the deck; but there it was at times so cold I could not endure it, for I had no blanket—no covering but my scanty clothes; and these were nearly always wet from washing the decks and the scud of the sea. The cold compelled me to seek shelter below, where if I stretched my weary limbs along the lid of a chest, and closed my eyes in sleep, I was sure to be aroused by its surly owner, who would push me rudely to the floor, and sometimes send me out of the forecastle altogether.

Add to this that I was almost constantly kept at work—by night as by day. I may say there was no drudgery—no “dirty work”—that was not mine. I was not only slave to captain, mates, and carpenter, but every man of the crew esteemed himself my master. Even “Snowball” in the “caboose”—as the cook was jocularly termed—ordered me about with a fierce exultation, that he had one white skin that he could command!

I was boot-black for the captain, mates, and carpenter, bottle-washer for the cook, and chamber-boy for the men—for it was mine to swab out the forecastle, and wait upon the sailors generally.

Oh! it was a terrible life. I was well punished for my one act of filial disobedience—well rewarded for my aspirations and longings for the sea. But it is just the rôle that many a poor sailor boy has to play—more especially if like me he has run away to sea.

Chapter Three.

For many long days and nights I endured this terrible oppression without complaining—not but that I could have complained and would, but to what purpose? and to whom? There was none to whom I might appeal—no one to listen to my tale of woe. All hands were equally indifferent to my sufferings, or at least seemed so, since no one offered either to take my part, or say a word in my favour.

At length, however, an incident occurred which seemed to make me in some measures the protégé of one of the sailors, who, though he could not shield me from the brutalities of the captain or mate, was at least able to protect me from the indignities I had hitherto suffered at the hands of the common men.

This sailor was named “Ben Brace,” but whether this was a real name or one which he had acquired at sea, I could never tell. It was the only name that I ever heard given him, and that by which he was entered in the ship’s books. It is quite possible that “Ben Brace” was his real name—for among seamen such appellations as “Tom Bowline,” “Bill Buntline,” and the like are not uncommon—having descended from father to son through a long line of sailor ancestry.

Ben Brace then was the name of my protector, and although the name is elsewhere famous, for the sake of truth I cannot alter it. How I came to secure the patronage of Ben was not through any merit of my own, nor indeed did it arise from any very delicate sympathy on his part. The companionship in which he had long lived had naturally hardened his feelings like the rest—though not by any means to so great an extent. He was only a little indifferent to human suffering—having witnessed much of it—and usage will make callous the most sensitive natures. Moreover, Ben had himself suffered ill-treatment, as I afterwards learnt from him—savage abuse had he suffered, and this had sunk into his spirit and rendered him somewhat morose. There was some apology for him if his manner was none of the gentlest. His natural disposition had been abused, for at bottom there was as much kindness in his nature as belongs to the average of men.

A rough, splendid seaman was Brace—the very best on board—and this point was generally conceded by the others—though he was not without one or two rivals.

It was a splendid sight to see Ben Brace, at the approach of a sudden squall, “swarming” up the shrouds to reef a topsail, his fine bushy curls blowing out behind, while upon his face sat that calm but daring expression, as if he defied the storm and could master it. He was a large man, but well proportioned—rather lithe and sinewy than robust, with a shock of dark-brown hair in their thick curls somewhat matted, covering the whole of his head; for he was still but a young man, and there were no signs of baldness. His face was good, rather darkish in complexion, and he wore neither beard nor whisker—which was rather odd for a sailor, whose opportunities for shaving are none of the best. But Ben liked a clean face, and always kept one. He was no sea dandy, however, and never exhibited himself, even on Sundays, with fine blue jacket and fancy collars as some others were wont to do. On the contrary, his wear was dark blue Guernsey shirt, fitting tight to his chest, and displaying the fine proportions of his arms and bust. His neck a sculptor would have admired from its bold regular outline, and his breast was full and well rounded, though, like that of all sailors, it was disfigured by tattooing, and over its surface when bare, and on his arms, you might have observed the usual hieroglyphics of the ship—the foul anchor, the pair of pierced hearts, with the B.B., and numerous other initials. A female figure upon the left breast, rudely punctured in deep-blue, was no doubt the presumed portrait of some black-eyed “Sal” or “Susan” of the Downs.

Such was Ben Brace, my new-found friend and protector.

How I came to secure his protection was by a chance incident, somewhat curious. It was thus:—

I had not been long on board before I made a discovery that somewhat astonished me, which was, that more than half the crew were foreigners. I was astonished at this, because I had hitherto been under the impression that an English ship was always manned by English sailors—including of course Scotch and Irish—either of whom make just as good sailors as Englishmen. Instead of being all English, or Scotch, or Irish, however, on board the Pandora (for that I had learnt was the name of the ship, and an appropriate name it was), I soon perceived that at least three-fourths of the men were from other countries. Were they Frenchmen? or Spaniards? or Portuguese? or Dutch? or Swedes? or Italians? No—but they were all these, and far more too, since the crew was a very large one for the size of the ship—quite two score of them in all. There seemed to be among them a representative of every maritime nation in the world, and, indeed, had every country in sending its quota selected the greatest scamp within its boundaries, they could hardly have produced a finer combination of ruffianism than was the crew of the Pandora! I have already hinted at exceptions, but when I came to know them all there were only two—my protector Brace, and another innocent but unfortunate fellow, who was by birth a Dutchman.

Among the mixed lot there were several Frenchmen, but one, named “Le Gros,” deserves particular notice. He was well named, for he was a stout, fat Frenchman, gross in body as in mind, with a face of ferocious aspect, more that half covered with a beard that a pirate might have envied—and indeed it was a pirate’s beard, as I afterwards learnt.

Le Gros was a bully. His great size and strength enabled him to enact the part of the bully, and upon all occasions he played it to perfection. He was a bold man, however, and a good seaman—one of the two or three who divided the championship with Ben Brace. I need hardly say that there was a rivalry between them, with national prejudices at the bottom of it. To this rivalry was I indebted for the friendship of Ben Brace.

It came about thus. By some trifling act I had offended the Frenchman, and ever after did he make it a point to insult and annoy me by every means in his power, until at length, on one occasion, he struck me a cruel blow on the face. That blow did the business. It touched the generous chord in the heart of the English sailor, that, despite the vile association in which he lived, still vibrated at the call of humanity. He was present, and saw the stroke given, and saw, moreover, that it was undeserved. He was lying in his hammock at the time, but instantly sprang out, and, without saying a word, he made a rush at Le Gros and pinned him with a John Bull hit upon the chin.

The bully staggered back against a chest, but in a moment recovered himself; and then both went on deck, where a ring was formed, and they went to work with the fists in right earnest. The officers of the ship did not interfere—in fact the mate drew near and looked on, rather as I thought with an interest in the combat, than with any desire to put an end to it, and the captain remained upon his quarter-deck, apparently not caring how it ended! I wondered at this want of discipline, but I had already begun to wonder at many other matters that occurred daily on board the Pandora, and I said nothing.

The fight lasted a good while, but ended as might be expected, when a fist combat occurs between an Englishman and Frenchman. The latter was badly thrashed, and that portion of his face that was not already black with hair was soon turned to a bluish-black by the rough, hard knuckles of his antagonist. He was at length felled to the deck like a great bullock, and obliged to acknowledge himself beaten.

“Now you danged parley voo!” cried Brace, as he gave the finishing blow, “don’t lay finger on that boy again, or I’ll give you just twice as much. The boy’s English after all, and gets enough, without being bullied by a frog-eatin’ Frenchman. So mind what I say, one and all of ye,” and as he said this he scowled round upon the crowd, “don’t lay a finger on him again ne’er one of you.”

Nor did they one or any of them from that time forth. Le Gros’s chastisement proved effectual in restraining him, and its example affected all the others.

From that time forth my existence became less miserable, though for many reasons it was sufficiently still hard enough to endure. My protector was strong to shield me from the crew, but I had still the captain, the carpenter, and the mate for my tormentors.

Chapter Four.

My condition, however, was greatly improved. I was allowed my full share of the “lob-scouse,” the “sea-pies,” and “plum-duff,” and was no longer hunted out of the forecastle. I was even permitted to sleep on the dry lid of a sailor’s chest, and had an old blanket given me by one of the men—who did it out of compliment not to myself but to Brace, whose good opinion the man wanted to secure. Another made a present of a knife, with a cord to hang it around my neck, and a tin platter was given me by a third. Such are the advantages of having a powerful patron. Many little “traps” were contributed by others of the crew, so that I soon had a perfect “kit,” and wanted nothing more.

Of course I felt grateful for all these odds and ends, though many of them were received from men who had formerly given me both cuffs and kicks. But I was never slow to forgive, and, friendless as I had been, I easily forgave them. I wanted all these little matters very badly. Boys who go to sea in the usual way go well provided with change of clothes—often two or three—with plates, knives, fork, and spoon, in short, a complete apparatus for eating.

In my hurry to get away from home I had not thought of bringing one single article of such things; and, consequently, I had nothing—not even a second shirt!

I should have been in a terrible fix, and was so, in truth, until the day on which Ben Brace thrashed the French bully; but from that time forward my condition was sensibly better. I felt grateful, therefore, to my protector, but another incident occurred shortly after, that not only increased my gratitude to the highest degree possible, but seemed also to make the man’s friendship for me still stronger than before.

The incident I am about to relate is one that has often occurred to sailor boys before my time, and no doubt will occur again, until governments make better laws for the regulation of the merchant service, with a view to control and limit the far too absolute power that is now entrusted to the commanders of merchant-ships. It is a positive and astounding fact, that many of these men believe they may treat with absolute cruelty any of the poor people who are under their command, without the slightest danger of being punished for it! Indeed, their ill-usage is only limited, by the length of time their unfortunate victim will stand it without making resistance. Among sailors, those who are known to be of an independent spirit and bold daring, are usually permitted to enjoy their rights and privileges; but the weak and unresisting have to suffer, when serving under mates and captains of this brutal kind, and it is to be regretted that there are too many such in the merchant navy of England.

The amount of suffering endured under such tyranny is almost incredible. Many a poor sailor of timid habits, and many a youthful sailor boy, are forced to lead lives that are almost unendurable—drudged nearly to death, flogged at will, and, in short, treated as the slaves of a cruel master.

The punishment inflicted—if it can be called punishment where no crime has been committed—is often so severe as to endanger life—nay, more, life is not unfrequently taken; and far oftener are sown the seeds of disease and consequent death, which in time produce their fatal fruit.

Of course every one admits that the commander of a ship at sea should possess some extraordinary powers over his men, beyond those which are allowed to the master of a factory or the surveyor of a public work. It is argued that without such, he could not answer for the safety of his vessel. There should be one head and that should be absolute. This argument is in part true. Every sensible man will admit that some extraordinary powers should be granted to the captain of a ship, but the mistake has hitherto lain, not so much in his possessing this absolute power, as in the want of an adequate punishment for him whenever he abuses it.

Hitherto the punishment has usually either failed altogether, or has been so disproportioned to the crime, as to be of no service for example to others. On the contrary, it has only encouraged them in their absolute ideas, by proving almost their complete irresponsibility. The captain, with his mates at his back, his money, and the habitual dread which many of his crew feel for him, can usually “out-swear” the poor victim of his brutality, and often the latter is deterred from seeking redress by actual fear of still worse consequences in case he may be defeated. Often too the wearied sufferer, on getting once more to land—to his home, and among his friends—is so joyed at the termination of his torments, that he loses all thoughts of justice or redress, and leaves his tyrant to depart without punishment.

The history of emigration would furnish many a sad tale of petty tyranny and spite, practised on the poor exile on the way to his wilderness home. There are chapters that might be written of bullyism and brutality—thousands of chapters—that would touch the chords of sympathy to the very core of the heart. Many a poor child of destitution—prostrated by the sickness of the sea—has submitted to the direst tyranny and most fiendish abuse on the part of those who should have cheered and protected him, and many a one has carried to his far forest home a breast filled with resentment against the mariner of the ocean. It is a matter of great regret, that the governments of migrating nations will not act with more energy in this matter, and give better protection to the exile, oft driven by misfortune in search of a new home.

A pity it is that better laws are not made for the guidance and restraint of merchant captains, who, taking them altogether, are naturally as honest, and perhaps not less humane, than any other class of men; but who thus entrusted with unbridled will and ill-defined powers, but follow the common fashion of human nature, and become tyrants of the very worst kind.

It is true that of late some salutary examples have been made, and one who richly deserved it has suffered the extreme punishment of the law; but it is to be feared that these good examples will not be followed up; public feeling will subside into its old channel of indifference, and the tyranny of the skipper-captain,—with that of his brutal coadjutor, the mate,—will be allowed to flourish as of yore, to the torture of many an unfortunate victim.

These remarks are hardly applicable to my own particular case, for the fiends who tortured me would have done so all the same if the best laws in the world had existed. They were beyond all laws, as I soon after learnt,—all laws, human or divine—and of course felt neither responsibility nor fear of punishment. They had no fear even to take my life, as will be proved by the incidents I am about to relate.

Chapter Five.

One of the disagreeables which a boy-sailor encounters on first going to sea is the being compelled to mount up “aloft.” If the master of the vessel be a man of considerate feelings, he will allow the apprentice a little time to get over the dread of climbing, by sending him only into the lower rigging, or no higher than the main or foretop. He will practise him a good deal upon the “shrouds,” so as to accustom his feet and fingers to the “ratlines” and other ropes, and will even permit him to pass a number of times through the “lubber’s hole,” instead of forcing him to climb back downwards by the “futtock shrouds.”

A few trials of this kind will take away the giddiness felt on first mounting to a high elevation, and thus a boy may safely be denied the use of the lubber’s hole, and may be sent up the futtock shrouds, and after that the topgallant shrouds, and so on to the royals,—if there be any on the ship,—and by thus gradually inducting him into the art of climbing, he will get over the difficulty without dread and without peril—for both of these may be encountered in first climbing to the upper rigging of a ship. It is usual then for masters, who are humane, to permit boys to become somewhat accustomed to the handling of ropes before sending them into the highest rigging.

But, alas! there are many who have not this consideration, and it is not uncommon for a youth, fresh from home and school, to be ordered up to the topgallant crosstrees, or even the royal-yard, at the very first go, and of course his life is imperilled by the ascent. Not unfrequent have been the instances in which the lives of boys have been sacrificed in this very way.

Now it so happened that for two weeks after I had set foot upon board the Pandora I had never been ordered aloft. I had not even had occasion to ascend the lower shrouds, though I had done so of my own will, as I was desirous of learning to climb. In all my life I had never been higher than the branches of an apple-tree; and since I had now chosen the sea for my profession—though I sadly repented my choice—I felt that the sooner I learnt to move about among the rigging the better.

But, singular to say, for the first two weeks after embarking myself on the Pandora I found but little opportunity of practising. Once or twice I had climbed up the ratlines, and crawled through the lubber’s hole to the maintop; and this I believed to be something of a feat, for I felt giddy enough while accomplishing it. I would have extended my enterprise by an attempt to ascend the topmast shrouds, but I was never allowed time, as the voice of either captain or mate would reach me from below, usually summoning me with an oath, and ordering me upon some other business, such as to mop out the cabin, swab the quarter-deck, black their boots, or perform some other menial act of service. In fact, I had begun to perceive that the drunken old skipper had no intention of teaching me anything of the seaman’s craft, but had taken me aboard as a sort of slave-of-all-work, to be kicked about by everybody, but by himself in particular. That this was in reality his design became every day more evident to me, and caused me disappointment and chagrin. Not that I was any longer ambitious of being a sailor, and could I have transported myself safely home again at that moment, it is not likely I should ever afterwards have set foot upon a ratline. But I knew that I was bent upon a long voyage,—how long or whither bound I could not tell,—and even though I might be able to desert from the Pandora when she reached her port,—a purpose I secretly meditated,—how should I act then? In a foreign land, without friends, without money, without the knowledge of a trade, how was I to exist, even if I could escape from the bondage of my apprenticeship? In all likelihood I should starve. Without knowing aught of seamanship, I should have no chance of getting a passage home again; whereas, if I had been allowed to practise with the rest, I might soon have acquired sufficient knowledge to enable me to “work my passage,” as it is termed, to any part of the world. This was just what I wanted, and it was on this account I felt so much aggrieved at finding it was the very thing I was not to be taught.

I had the hardihood on one occasion,—I know not what inspired me,—to make a remonstrance about this to the captain. I made it in the most delicate manner I could. My immediate answer was a knock-down, followed by a series of kicks that mottled my body with blue spots, and the more remote consequence of my “damned impudence,” as the captain called it, was worse treatment than ever.

I would soon have learnt to climb had I been left to myself, but I was not allowed even to practise that. I was always called below by one or the other of my tyrants, and with an oath, a cuff, or a kick, ordered upon some piece of “dirty work.”

Once, however, I was not ordered “alow,” but “aloft;” once I was allowed to have my fill of climbing.

Snatching an interval when I thought both mate and master were asleep, I had gone up to the maintop.

Every one who has looked upon a full-rigged ship must have noticed some distance up the main-mast a frame-wood or platform, like a little scaffold. A similar construction may be observed on the fore and mizen-mast, if the ship be a large one. This platform is called the “top,” and its principal object is to extend the ladder-like ropes, called “shrouds,” that reach from its outer edge to the head of the mast next above, which latter is the topmast. It must here be observed that the “masts” of a ship, as understood by landsmen, are each divided into a number of pieces in the reckoning of a sailor. For instance, in a ship or barque there are three which are called respectively the main, fore, and mizen-masts—the main-mast being near the middle of the ship, the fore-mast forward, towards the bows, and the mizen-mast “aft,” near the stern or poop. But each one of these is divided into several pieces, which pieces have distinct names in the sailor’s vocabulary. Thus, the “main-mast,” to a sailor, is not the whole of that long straight stick which rises up out of the middle of a ship’s deck, and points like a spire to the sky. On the contrary, the main-mast terminates a little above the platform just mentioned, and which, from that circumstance, is designed the “maintop.” Another mast, quite distinct from this, and made out of a separate piece of timber there begins, and runs up for nearly an equal length, but of course more slender than the main-mast itself, which latter supports it. This second is called the “main-topmast.” Above that a third is elevated, supported upon the topmast head by cheeks, trestles, and crosstrees. This is shorter and more slender than the main-topmast, and is named the “main-topgallant-mast,” and above this again, the “main-royal-mast” is similarly raised—though it is only in the largest and best rigged vessels that a “royal-mast” is used. The “main-royal-mast” terminates the structure, and its top, or head, is usually crowned with a flat circular piece of wood, called the “main-truck,” which is the most elevated point in the ship. The fore and mizen-masts are similarly divided, though the latter is much shorter than either of the others and rarely has topgallant-sails, and still more rarely “royals.”

I have given this explanation in order that you may understand that the maintop to which I say I climbed was not the most elevated point of the mast, but simply the platform near the head of the main-mast, as understood by sailors.

This platform is, in the common parlance of the crew, frequently designated the “cradle,” and it merits the appellation, for in a vessel at sea and under a breeze it is generally “rocked” about, either in long sweeps from side to side, or backward and forward from stem to stern, according to the ship’s motion. It is the pleasantest part of the ship for one who is inclined to solitude, for once upon it, you cannot see aught of what is going on below, unless you look over the edge or down through the lubber’s hole already mentioned. You may hear the voices of the crew, but not distinctly, as the surge of the sea itself, and the wind drumming upon the sails and whistling through the shrouds, usually drowns most other sounds. To me it was the greatest luxury to spend a few minutes in this retired spot. Sick of the association into which I had so heedlessly thrown myself—disgusted with the constant blasphemy ever in my ears, and above all, longing for repose, I would have given anything to have been permitted to spend my leisure hours in this aerial cradle, but I found no leisure hours nor moments for such indulgence, for my unfeeling tyrants gave me neither rest nor repose. The mate, in particular, seemed to take pleasure in rendering my existence as miserable as he could, and, discovering that I had a predilection for the “top,” seemed determined that of all other places I should not go there to rest myself.

One day, however, believing that he and the captain had both gone to sleep,—as they sometimes did in fine weather—I took the opportunity of ascending to my favourite perch; and, stretching my wearied limbs along the hard planks, I lay listening to the sad sighing of the winds and the waters. A sweet breeze fanned my brow, and, notwithstanding the danger which there was in falling asleep there—for there was no “top armour” or netting upon the Pandora—I was soon in the land of dreams.

Chapter Six.

My dreams were by no means of a pleasant nature.

How could they be, considering the life I was compelled to lead? With my spirit hourly harassed by indignities, and my body wearied with overwork, it is not likely I should have sweet dreams.

Though not sweet, however, they were short enough—at least my sleep was so, for my eyes had not been closed above five minutes when I was rudely awakened, not by a voice, but by a smart thwack upon the hips, administered by no light hand, and with an instrument that I knew by the feel to be what, in sailors’ parlance, is called a “rope’s end.”

It needed no repetition of the stroke to awake me and cause me to start to my feet; had it done so, I should certainly have caught it again as sharply as before—for, on springing up, I saw the hand of the fellow who had struck me raised aloft to repeat the blow. He did repeat it, but my sudden rising spoiled his aim, and the rope’s end doubled loosely over my shoulders.

I was not a little astonished on recognising the ruffian. It was the French bully—Le Gros!

I knew that he had the disposition to flog me with a rope’s end, or anything else—for he still harboured a heart full of malice against me—I well knew that he was not wanting in the will; had we been in some corner of the earth all alone by ourselves, I should not have been astonished at him flogging me almost to death—not a bit of it. But what surprised me was his daring to do so there and then. Ever since Brace had thrashed him, he had been as mute as a mouse—morose enough with me, but never offering any insult that might be resented by my protector.

What had happened then to cause this change? Had he again fought with Brace and beaten him? Or had my patron taken some offence at me and withdrawn his protection, thus leaving the ruffian free to chastise me for his own especial pleasure?

Surely some change must have taken place in our mutual relations, else Le Gros would never have dared to raise his hand against me in the manner he was doing?

Therefore was I surprised and puzzled—could it be that, finding me all alone upon the top, he had taken the fancy into his head that he could there give me a drubbing without being seen?

Surely that could not be his idea? If not seen, I could be heard. I might easily cry out, so that my protector would hear me; or even if he could not, I could tell him afterwards, and though that would not save me from the drubbing it would get me the satisfaction of seeing Le Gros catch one as well.

These reflections passed almost instantaneously through my mind—they occupied only a few seconds—just the interval that elapsed from the time I first stood to my feet till I recovered from the surprise I felt at being confronted by the Frenchman. It was a short pause, for the bully had again elevated the rope’s end to come down with another thwack.

I leaped to one side and partially avoided the blow, and then rushing in towards the mast I looked down the lubber’s hole to see if Brace was below.

He was not visible, and I would have cried out for him, but my eyes at that moment rested upon two objects and caused me to hold my voice. Two individuals were upon the quarter-deck below, both looking upward. It was not difficult to recognise them—the plump, jolly, false face of the skipper and the more ferocious countenance of his coadjutor were not to be mistaken. Both, as I have said, were looking upward, and the wicked expression that danced in the round bullet eyes of the former, with the grim smile of satisfaction that sat upon the lips of the latter, told me at a glance that the Frenchman and I were the objects of their attention.

The unlooked-for attack on the part of Le Gros was now explained:—he was not acting for himself, but as the deputy of the others! it was plain they had given him orders, and from the attitude in which they stood, and the demoniac expression already noticed, I felt satisfied that some new torture was intended for me.

I did not cry out for Brace, it would have been of no use. The brave fellow could not protect me from tyrants like these. They were his masters, with law on their side to put him in chains if he interfered, even with his voice—to shoot or cut him down if he attempted to rescue me.

I knew he dare not interrupt them, no matter what cruelty they might inflict. It would be better not to get him into trouble with his superiors, and, under these considerations, I held my tongue and awaited the event. I was not kept long in doubt about their intentions.

“Hang the lazy lubber!” shouted the mate from below—“snoring in broad daylight, eh? Wake him up with the rope’s end, Frenchy! Wallop him till he sings out!”

“No,” cried the captain, to whom a better programme had suggested itself. “Send him aloft! He seems fond of climbing up stairs. Drive him to the garret! He wants to be a sailor—we’ll make one of him!”

“Ha! ha!” rejoined the mate with a hoarse laugh at the wit of his superior; “the very thing, by Jove! give him an airing on the royal-yard!”

“Ay—ay!” answered Le Gros, and then, turning to me, with the rope held in menace, he ordered me to ascend.

I had no alternative but obey, and, twisting myself around the topmast shrouds, I caught the ratlins in my hands and commenced climbing upward.

Chapter Seven.

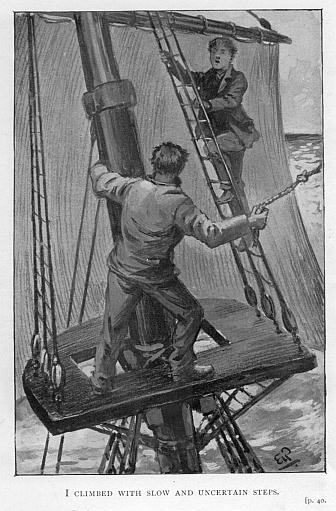

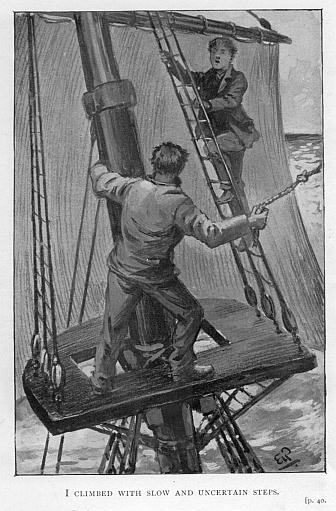

I climbed with slow and nervous step. I should have gone much slower but that I was forced upward by Le Gros, who followed me with the rope’s end, with which he struck me behind whenever I made a stop. He delivered his blows with fiendish spite, striking me about the legs and over the posteriors, and trying to hurt me as much as possible. In this he succeeded, for the hard-knotted rope pained me exceedingly. I had no alternative therefore but to keep on upward or submit to his lashing. I kept on.

I reached the topmast crosstrees, and mounted upon them. Oh! it was a fearful sight to look down. Below me was nothing but the sea itself, for the masts, bent over by the breeze, were far from being perpendicular. I felt as if suspended in the air, with not even the earth beneath me—for the surface of the sea was below, glittering like the sky itself.

Beneath me, however, at my feet, was the dark, scowling face of Le Gros, who, with threatening voice and gestures, ordered me upward—still upward!

Upward! how could I climb father? Above me extended the topgallant rigging. Upon this there were no rattlins, nothing to rest the foot upon—nothing but the two black rigid ropes converging until they met at the head of the mast. How could I ascend them? It seemed beyond my power to do so.

But I was not even allowed to hesitate. The brute swung himself near, and continued plying the knotted cord upon my shins, at the same time uttering oaths and ferocious threats that he would cut every inch of skin off my body if I did not go aloft.

I had no alternative but to try, and, placing myself between the ropes, I commenced drawing myself upward. After a severe effort I succeeded in getting upon the topgallant yard, where I again paused—I could go no further. My breath was quite gone and I had scarce strength to hold by the rigging and prevent myself from falling.

The royal-mast still towered above, and below, threatened the dark face of Le Gros. There was a smile upon it in the midst of its scowling—a smile of satisfaction at the agony he saw I was undergoing at that moment.

I could still hear the voices of the fiends below, calling out the commands: “Up with him, Frenchy—up to the royal-yard!”

I thought I heard other voices, and that of Brace repeating the words, “Avast there! avast! the lad’s in danger.”

I looked in a slanting direction toward the deck. I saw the crew standing by the forecastle! I thought there was confusion among them, and a scuffle, as if some were taking his part, and others approving of what was going on; but I was too frightened to make an exact observation at the moment, and too much occupied by the ruffian who was nearest me.

“Up!” he cried, “up, or pe Gar! I flog you to ze death for von land lobber—I vill sacr–r–é!”

And with this threat he again plied the instrument of torture, more sharply than ever.

I could not stand it. The royal-yard was the highest point to which they intended to force me. If I could reach it then they would be satisfied, and would cease to punish me. It is a perilous feat, even for one who has had some practice in climbing, to reach the royal-yard of a big ship, but to me it appeared impossible that I could accomplish it. There was but the smooth rope—with neither knot nor loop to aid hand or foot. I must go up it hand over hand, dragging the whole weight of my body. Oh! it was a dread and perilous prospect, but despair or rather Le Gros, at length forced me to the trial, and, grasping the smooth stay rope, I commenced climbing upward.

I had got more than half-way—the royal-yard was almost within reach—when my strength completely failed me. My heart grew weak and sick, and my head swam with giddiness. I could sustain myself no longer, my grasp on the rope gave way, and I felt myself falling—falling—at the same time choking for want of breath.

For all this I did not lose consciousness. I still preserved my senses through all that terrible descent; and believed while falling that I should be killed by the fall, or, what was the same thing, drowned in the sea below. I was even sensible when I struck the water and plunged deeply below the surface, and I had an idea that I did not drop directly from the royal-mast into the sea, but that my fall was broken by something half-way down. This proved to be correct, as I afterwards learnt. The ship chanced to be under full canvas at the time, and the maintopsail, swollen out by the fresh breeze, had caught me on its convex side as I came down. From this I had bounded off again, but the impetus of the fall had been thus lessened; and the second pitch into the sea was not so violent as it would otherwise have been. Otherwise, indeed, I should have been crushed upon the surface of the water, never to breathe again. Another circumstance happened in my favour: my body had turned round as I parted from the top, and I was going head downward; but, on striking the sail, the attitude was reversed, and I reached the water in a perpendicular position, with my feet downward. Consequently, the shock was less, and, sinking deeply in the waves, I was saved. All these points I learned afterwards, from one who had anxiously watched me in my descent.

When I rose to the surface of course it was with confused senses, and with surprise that I still lived—for I had been certain on letting go my hold that I was being hurled into eternity—yes, I fully believed that my end had come.

I now perceived that I was still living—that I was in the sea—that waves were dashing around me; and on looking up I saw the dark ship at a cable’s distance from me, still passing away. I thought I saw men standing along the taffrail, and some clinging upon the shrouds; but the ship appeared to be going fast away, and leaving me behind in the water.

I had learnt to swim, and, for a boy, was a good average swimmer. Feeling that I was not hurt I instinctively struck out, though not to follow the vessel, but to keep myself from sinking. I looked around to see if there was anything I might cling to, as I fancied that something might have been thrown out from the ship. I could see nothing at first, but as I mounted upon the top of a wave I noticed a dark round object, between me and the hull, which, notwithstanding that the sun was in my eyes, I made out to be the head of a man. He was still at some distance, but evidently nearing me, and as it approached I recognised the thick curly hair and countenance of my protector Brace. He had leaped overboard and was swimming to my rescue. In a few seconds he was by my side.

“Ho!” cried he, as he drew near and saw that I was swimming, “all right my lad! swim like a duck, eh?—all right—don’t feel hurt, do you? Lean on me, if you do.”

I answered that I felt strong enough to swim for half-an-hour if necessary.

“All right then,” he rejoined; “we’ll get a rope’s end in less time than that, though maybe you fancy you’ve had enough of rope’s end? Hang the inhuman scoundrels. I’ll revenge you yet, my lad. Ship ahoy!” he shouted, “this way with your rope! ahoy! ahoy!”

By this time the ship had worn round, and was returning to pick us up. Had I been alone in the water, as I afterwards ascertained, this manoeuvre would not have been executed; or, at all events, but very little pains would have been taken to rescue me. But Brace having jumped overboard rendered it necessary that the ship should be put about, and every effort made to recover him, as he was a man of too much importance among the crew to be sacrificed with impunity. Neither mate nor captain dared leave him to his fate; and, consequently, the orders were given to “wear-ship.”

Fortunately the breeze was light, and the sea not very rough; and as the vessel passed near to where we were swimming, ropes were thrown out which both of us were able to seize, and by means of which we were soon hauled up, and stood once more safely upon deck.

The spite of my tormentors seemed to be satisfied for the time. I saw nothing of any of them when I got aboard, nor during the remainder of that day, as I was permitted to go below and remain in the forecastle during the whole of the afternoon.

Chapter Eight.

Strange to say, I received somewhat better treatment after this occurrence, though it was not from any remorse at what had happened, or that either mate or captain had grown more humane or friendly. The reason was very different. It was because both perceived that what they had done had produced an unfavourable impression upon the crew. Many of the men were friends and admirers of Brace, and, along with him, disapproved altogether of the conduct of the officers, so that in the forecastle and around the windlass there was a good deal of disaffected talk after this event, often spoken loudly enough. Brace, by his behaviour in leaping overboard to the rescue, had gained favour—for true courage always finds admirers whether they be rude or refined—and the number of Brace’s friends was increased by it. I heard that he had really interfered when I was being forced aloft, and had shouted out contradictory orders to those of the mate. This accounted for the confusion I had noticed on deck, and which was the result of several of his friends endeavouring to restrain him, while others were joining him in his appeal.

Both Captain and mate on the quarter-deck had heard all this, but pretended not to notice it. Had it been any other man than Brace they would have instantly put him in irons, or punished him still more severely,—especially if he had chanced to be one of the weaker and less popular of the crew. As it was, they took no steps in the matter, and no one was punished for the expressions of remonstrance that had been used. But both captain and mate had noted the disaffection; and that was the reason why I was afterwards treated with more humanity, or rather with less cruelty—for insults and indignity were still occasionally offered me by one or the other.

I was from this time permitted to practise with the sailors, and had less of the dirty work to do. A sort of simple fellow, the Dutchman already mentioned—who was also much played upon,—shared with me the meaner drudgery, and had more than half of the spleen which the captain and mate must needs spend upon somebody. Indeed, the poor Dutchman, who, although a harmless creature, was a wretched specimen of humanity, came well-nigh being killed by their cruelty; and I have no doubt but that the injuries inflicted upon him, while on board the Pandora, would have brought him to an earlier grave than Nature designed for him, had it not been his sad fate to meet death at a still earlier period,—as I shall have occasion to relate.

The cruelties committed upon this man by the captain and mate of the Pandora would be incredible if told,—incredible, because it would scarce be believed that the human heart is capable of such want of feeling. But it seems to be a law of wicked natures, that where cruelty has once commenced its career and meets with no resistance on the part of its victim, the vile passion, instead of being satisfied, only grows stronger and fiercer, just like it is with savage beasts after they have tasted blood. So seemed it with the officers of the Pandora, for if they even had cause for revenge against this poor sailor, they certainly took ample satisfaction; but it was just because they had no reason for revenge,—just because there was no resistance on the part of their victim that they delighted to torture him.

I remember many of their modes of torture. One was to tie him up by the thumbs, so that his toes just touched the deck, and there keep him for hours together. This position may appear easy enough to one who has never experienced it. It is far otherwise,—it is a torture worthy of the Inquisition. It soon elicits groans from its victim. Another mode of punishment—or rather of amusing themselves—practised by the worthies of the Pandora’s quarter-deck on this poor sailor, was to sling him in his own belt half-way up to the yard-arm, and there leave him dangling about. This they jocularly called “slinging the monkey,” adopting the name of a favourite sport often practised by the sailors. Once they shut him up in an empty cask, and kept him for several days without food. A little biscuit and water was at length passed through the bung-hole, which the poor wretch greedily devoured barely in time to save himself from perishing of hunger and thirst. But there are other modes of chastisement too horrible and too abominable to be told, all of which were practised upon this unfortunate man—unfortunate in having no friend, for strange to say he received but little sympathy or commiseration from the rest of that wicked crew. Though a harmless creature enough, he was one of those unfortunates whose habits prevent them from making either friends or associates.

It seemed as if the poor fellow’s misery was to me an advantage, and shielded me from a good deal of ill-treatment I should otherwise have experienced. He stood between me and our common tyrants as a sort of breakwater or “buffer,” upon which their inhumanity expended most of its strength!

I pitied him for all that, though I dared not make exhibition either of my pity or sympathy. I had need of both for myself, for although I have said that my condition was improved, I was still miserable—wretched as I could well be.

And why? you will ask,—Why wretched now, when I had got over most of the first difficulties, and was steadily progressing in the profession I had so ardently desired to belong to? It is quite true I was progressing, and rapidly. Under the tutorship of Brace I was fast becoming a sailor. In less than a week after I had made my plunge from the royal rigging, I could climb to the royal-yard without the slightest fear—ay, I had even in a fit of bravado gone higher, and put my hand upon the main-truck! In a week’s time I knew how to twist a gasket, or splice a rope, as neatly as some of the sailors themselves; and more than once I had gone aloft with the rest to reef topsails in a stiffish breeze. This last is accounted a feat, and I had creditably performed it to the satisfaction of my patron. Yes, it is quite true I was speedily being transformed into a sailor; and yet I was far from being satisfied with my situation—or rather I should say—I was miserably ill-satisfied—perfectly wretched.

You are surprised and demand the reason. I shall give it in a few words.

I had not been many days on board the Pandora when I observed something which I fancied odd about the ship. I first noticed the manner and discipline, or rather want of discipline, of the crew, far different from what I had read of in books, which told of the exact obedience and punctilious respect between those who served and those who commanded. It might be, however, that those of which I had read were ships of war, and that in others the discipline was very different. As I had no previous knowledge of seamen, or their mode of life, I concluded that the rude behaviour of the Pandora’s crew might be a fair specimen of it, and I was both pained and humiliated by the conclusion. It was a sad realisation—or contradiction rather—of all my young dreams about the free happy life of the sailor, and I was disgusted both with him and his life at the very outset.

Another circumstance attracted my attention at the same time—that was the number of hands on board the Pandora. She was not a very large ship—not over 500 tons by registry. In fact she was not a “ship,” speaking technically, but a “barque;” in other words, a ship with her mizen-mast rigged unlike the other two, or without a “square” topsail. In this, and a few other points, lies the difference between a barque and a ship—though the former is also usually smaller.

The Pandora was large enough for a barque,—carried a full suit of sail, even to flying-jibs, topgallant studding-sails, and royals; and was one of the fastest sailors I have ever known. For her size, however, and the amount of merchandise she carried, I could not help fancying that she had too large a crew. Not over half of them seemed to be employed, even while wearing ship—and I was convinced that half of them could have done the work. I had been told often—for I used to make inquiry about such matters—that a crew of from ten or twenty hands was sufficient for a vessel of her size; what then could the Pandora want with twice that number? I counted them over and over. There were forty of them all told, including the worthies of the quarter-deck and Snowball in the caboose!

The circumstance made an impression upon me—somewhat undefined it is true—but day by day, as I observed the reckless and disgusting behaviour of both officers and men, and overheard some strange conversations, suspicions of a most painful character formed themselves in my mind and I began to dread that I had got into the company of real ruffians indeed.

These suspicions were at length confirmed, and to the fullest extent.

For several days after setting sail the hatches had been down and covered with tarpaulings. The weather had continued breezy, and as there was little occasion to go below they had been kept thus, though now and again a half-hatch had been lifted as something was required from the lower deck or the hold. I myself had not been sent below on any errand, and had never seen the cargo, though I had been told that it consisted chiefly of brandy, and we were going with it to the Cape of Good Hope.

After a while, however, when the weather became fine, or rather when we had sailed into a southern latitude where it is nearly always fine, the tarpaulings were taken off, the hatches—both main and fore—were thrown open, and all who wished passed down to the “’tween decks” at their pleasure.

Curiosity, as much as aught else, took me below; and I there saw what not only confirmed my suspicions but filled me with disgust and horror. The cargo, which was all down in the hold, and none of it on the lower deck, certainly appeared—what it had been represented—a cargo of brandy; for there were the great puncheons, scores of them, in the hold. Besides these there were some boxes of merchandise, a quantity of bar iron, and a large pile of bags which appeared to contain salt.

All this I saw without any uneasiness. It was not these that produced within me the feeling of disgust and horror. It was a pile of manufactured iron that lay upon the lower deck; iron wrought into villainous shapes and hideous forms, that, notwithstanding my inexperience, I at once recognised as shackles, manacles and fetters! What wanted the Pandora with these?

But the secret was now out. I needed to employ conjectures no longer. The carpenter was at work upon some strong pieces of oak timber, which he was shaping into the fashion of a grating, I perceived that it was intended for the hatchway.

I needed no more light. I had read of the horror of the “middle passage.” I recognised the intention of the carpenter’s job. I no longer doubted that the Pandora was a slaver!

Chapter Nine.

Yes—beyond a doubt I was on board a slave-ship—one regularly fitted up for the inhuman traffic—manned for it. I might also say armed—for although there were no cannon, I observed a large number of muskets, cutlasses, and pistols, that had been brought upon the deck from some secret hiding-place, and distributed to the men to be cleaned and put in order. From all this it was plain that the Pandora was bent upon some desperate enterprise, and although she might not sustain a combat with the smallest vessel of war, she was determined that no mere boat’s crew should capture and rob her of her human freight. But it was to her sails more than to her armour that the Pandora trusted for success; and, indeed, built and rigged as she was, few ships of war could have overhauled her in open water, and with a fair wind.

I say that I no longer doubted of her true character. Indeed the people on board no longer made a secret of it. On the contrary, they appeared to glory in the occupation, regarding it in the light of achievement and enterprise. Over their cups they sang songs in which the “bold slaver” and his “jolly crew” were made to play the heroic, and many a coarse jest was uttered relating to the “black-skinned cargo.”

We had now passed to the southward of Gibraltar Straits, and were sailing in a track where there would be less likelihood of falling in with English men-of-war. The cruisers, whose sole business it is to look after the slave-trade, would be found much farther south, and along the coasts where slaves are usually shipped; and as there was no fear of meeting with them for some days to come, the Pandora’s crew had little else to do than enjoy themselves. A constant carousal, therefore, was kept up, and drinking, singing, dancing, and “skylarking” were practised from morning to night.

You may be surprised to know that a ship so evidently fitted out for slave-traffic could have thus openly and directly sailed out of a British port. But it is to be remembered that the period of which I am writing was many years ago; although so far as that goes, it would be no anachronism to lay the scene of my narrative in the year 1857. Many a slave-ship has sailed from British ports in this very year, and with all our boasted efforts to check the slave-trade it will be found that as large a proportion of British subjects are at present engaged in this nefarious traffic as of any other nation.

The attempt to put down the African slave-trade has been neither more or less than a gigantic sham. Not one of the governments who have engaged in this scheme of philanthropy have had more than a lukewarm interest in the matter, and the puny efforts they have made have been more for the purpose of pacifying a few clamorous philanthropists, than with a real design to stop the horrid traffic. For one slave-ship that is captured at least twenty pass free, landing their emaciated thousands upon the shores of the western world. Nay—worse than ever—the tyrant who, with railroad speed, is demoralising the millions of France, lends his ill-gotten power to re-establish this barter of human souls, and the slave-trade will ere long flourish as luxuriantly as ever.

It would have been an easy matter for Great Britain long since to have crushed out every vestige of the slave-trade, even without adding one item to her expenditure. What can be more absurd than the payment of 300,000 pounds to Portuguese slave-merchants to induce them to abandon the traffic in slaves? Why it is a positive premium upon crime—an indemnity for giving up the trade of pillage and murder! I say nothing would have been easier than for England to have put an end to the very existence of this horror years ago. It would only have required her to have acted with more earnestness, and a little more energy—to have declared that a slave-dealer was a pirate, and to have dealt with him accordingly—that is, hanged him and his crew, when taken, from the yard-arm of their ship—and there was not a nation in the world that would have dared to raise voice against such a course. Indeed it is a perfect absurdity to hang a pirate and let a slaver escape: for if it be admitted that a black man’s life is of as much value as a white man’s, then is the slaver doubly a murderer, for it is a well-known fact, that out of every slave cargo that crosses the Atlantic, full one-third become victims of the middle passage. It is, therefore, a positive absurdity to treat the captain and crew of a slave-ship in any milder way than the captain and crew of a pirate ship; and if a like measure of justice had been constantly served out to both, it is but natural to suppose that slavers would now have been as scarce as pirates are, if not a good deal scarcer. How the wiseacres who legislate for the world can make a distinction between the two sorts of ruffians is beyond my logic to understand, and why a slaver should not be hanged as soon as caught is equally a puzzle to me.

In years past this might have been done, and the slave-trade crushed completely. It will be more difficult now, since the despot of France has put the stamp of his licence on the inhuman trade, and the slave-dealer is no longer an outlaw. It would be a very different affair to hang to the yard-arm some French ruffian, bearing his commission to buy souls and bodies, and under the signature of imperial majesty.

Alas, alas! the world goes back; civilisation recedes—humanity has lost its chance, and the slave-trade goes on as briskly as ever!

I was too young at the time of my first voyage to moralise in this philosophic manner; but for all that I had imbibed a thorough disgust for the slave-trade, as, indeed, most of my countrymen had done. The period of which I am speaking was that when, by the laudable efforts of Wilberforce and other great philanthropists, our country had just set before the world that noblest example on record—the payment of twenty millions of sterling pounds in the cause of humanity. All glory to those who took part in the generous subscription. Young as I was, I like others, had heard much of the horrors and cruelties of the slave-trade, for at that time these were brought prominently before the public of England.

Fancy, then, the misery I experienced, at finding myself on board a ship actually engaged in this nefarious traffic—associating with the very men against whom I had conceived such antipathy and disgust—in fact myself forming one of the crew!

I cannot describe the wretchedness that came over me.

It is possible I should have been more shocked had I made the discovery all at once, but I did not. The knowledge came upon me by degrees, and I had long suspicions before I became certain. Moreover, harassed as I had been by personal ill-treatment and other cares, I did not so keenly feel the horror of my situation. Indeed, I had begun to fancy that I had got among real pirates, for these gentry were not uncommon at the time, and I am certain a gang of picaroons would not have been one whit more vulgar and brutal than were the crews of the Pandora. It was rather a relief, therefore, to know they were not pirates—not that their business was any better,—but I had the idea that it would be easier to get free from their companionship; which purpose I intended to carry out the very first opportunity that offered itself.

It was about the accomplishment of this design that I now set myself to thinking whenever I had a moment of leisure; and, verily, the prospect was an appalling one. It might be long months before I should have the slightest chance of escaping from that horrid ship,—months! ay, it might be years! It was no longer any articles of indenture that I dreaded, for I now perceived that this had been all a sham, since I could not be legally bound to a service not lawful in itself. No, it was not anything of this sort I had to fear. My apprehensions were simply that for months—perhaps years—I might never find an opportunity of escaping from the control of the fiends into whose hands I had so unwittingly trusted myself.

Where was I to make my escape? The Pandora was going to the coast of Africa for slaves; I could not run away while there. There were no authorities to whom I could appeal, or who could hold me against the claims of the captain. Those with whom we should be in communication would be either the native kings, or the vile slave-factors,—both of whom would only deliver me up again, and glory in doing so to gratify my tyrant. Should I run off and seek shelter in the woods? There I must either perish from hunger, thirst, or be torn to pieces by beasts of prey—which are numerous on the slave-trading coasts. One or other of these would be my fate, or else I should be captured by the savage natives, perhaps murdered by them,—or worse, kept in horrid bondage for life, the slave of some brutal negro,—oh! it was a dread prospect!

Then in my thoughts I crossed the Atlantic, and considered the change of escape that might offer upon the other side. The Pandora would no doubt proceed with her cargo to Brazil, or some of the West India islands. What hope then? She would necessarily act in a clandestine manner while discharging her freight. It would be done under cover of the night, on some desert coast far from a city or even a seaport, and, in fear of the cruisers, there would be great haste. A single night would suffice to land her smuggled cargo of human souls, and in the morning she would be off again—perhaps on a fresh trip of a similar kind. There might be no opportunity, whatever, for me to go ashore—in fact, it was not likely there would be—although I would not there have scrupled to take to the woods, trusting to God to preserve me.

The more I reflected the more was I convinced that my escape from what now appeared to me no better than a floating prison, would be an extremely difficult task,—almost hopeless. Oh! it was a dread prospect that lay before me.

Would that we might encounter some British cruiser! I heartily hoped that some one might see and pursue us. It would have given me joy to have heard the shot rattling through the spars and crashing into the sides of the Pandora!

Chapter Ten.

Of course I did not give utterance to these sentiments before any of the Pandora’s crew. That would have led me into worse trouble than ever. Even Brace could not have protected me had I given expression to the disgust with which my new associates had inspired me, and I acted only with the ordinary instinct of prudence when I held my tongue and pretended not to notice those matters that were queer. Withal, I could not altogether dissemble. My face might have told tales upon me; for more than once I was taken to task by my ruffian companions, who jeered me for my scruples, calling me “green-horn,” “land-lubber,” “son of a gun,” “son of a sea-cook,” and other like contemptuous appellations, of which, among sailors, there is an extensive vocabulary. Had they known the full measure of contempt in which I had held them, they would scarce have been satisfied by giving me nicknames only. I should have had blows along with them; but I took care to hide the dark thoughts that were passing in my bosom.

I was determined, however, to have an explanation with Brace and ask his advice. I knew that I could trust him, but it was a delicate point; and I resolved to approach him with caution. He might be angry with me; for he, too, was engaged in the same nefarious companionship. He might be sensitive and reproach me for a meddler.

And yet I fancied he would not. One or two expressions I had heard him drop casually, had led me to the belief that Brace was tired of the life he was leading—that he, too, was discontented with such a lot; and that some harsh fate had conducted him into it. I hoped that it was so; for I had grown greatly interested in this fine man. I had daily evidence that he was far different from his associates,—not hardened and wicked as they. Though under the influence of association men gradually assume the tone of the majority, yet Brace had a will and a way of his own,—there was a sort of moral idiosyncracy about him that rendered him unlike the rest, and which he appeared to preserve, notwithstanding the constant contamination to which he was exposed by his companionship with such fellows. Observing this, I resolved to make known to him the cause of my wretchedness, and to obtain his advice as to how I should act.

An opportunity soon offered—a chance of conversing with him unheard by the rest of the crew.

There is a pleasant place out upon the bowsprit, particularly when the foretop-mast stay-sail is hauled down, and lying along the spar. There two or three persons may sit or recline upon the canvas, and talk over their secrets without much risk of being overheard. The wind is seldom dead ahead, but the contrary; and the voices are borne forward or far over the sea, instead of being carried back to the ears of the crew. A meditative sailor sometimes seeks this little solitude, and upon emigrant ships, some of the more daring of the deck-passengers often climb up there—for it requires a little boldness to go so high aloft over the water—and pour into one another’s ears the intended programme of their trans-oceanic life.

Brace had a liking for this place; and often about twilight he used to steal up alone, and sit by himself, either to smoke his pipe or give way to meditation.

I wished to be his companion, but at first I did not venture to disturb him, lest he might deem it an intrusion. I took courage after a time, and joined him upon his perch. I saw that he was not dissatisfied—on the contrary, he seemed pleased with my companionship.

One evening I followed him up as usual, resolved to reveal to him the thoughts that were troubling me.

“Ben!” I said, in the familiar style in which all sailors address each other. “Ben!”

“Well, my lad; what be it?”

He saw I had something to communicate, and remained attentively listening.

“What is this ship?” I asked after a pause.

“She a’n’t a ship at all, my boy—she be a barque.”

“But what is she?”

“Why, a’n’t I told you she be a barque.”

“But what sort, I want to know?”

“Why, in course, a regular rigged barque—ye see if she were a ship the mizen-mast yonder ’ud be carryin’ squares’ls aloft, which she don’t do as ye see—therefore she’s a barque and not a ship.”

“But, Ben, I know all that, for you have already explained to me the difference between a ship and a barque. What I wish to ascertain is what kind of a vessel she is?”