The Project Gutenberg EBook of Yr Ynys Unyg, by Julia de Winton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Yr Ynys Unyg

The Lonely Island

Author: Julia de Winton

Release Date: October 20, 2007 [EBook #23090]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK YR YNYS UNYG ***

Produced by Emmy, Stephen Blundell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The University of Florida, The Internet

Archive/Children's Library)

LONDON:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, AND CO., STATIONERS' HALL COURT;

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND CO., FARRINGDON STREET.

NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE: F. AND W. DODSWORTH.

1852.

Transcriber's Note

Archaic and dialect spellings remain as printed. Punctuation has been normalised. Significant errors have been noted at the end of the text. A table of contents has been provided below:

Dear Friend,

I enclose you the manuscript of which you have so long desired possession. You have permission to do what you like with it, on one condition, which is, that you alter all the names, and expunge anything like personality therein; for, as you are aware (with two exceptions) each character mentioned in the story is now alive, and so few years have elapsed since the events recorded took place that it would not be at all difficult for a stranger to recognize the heroes and heroines therein mentioned. Having settled that business, I now proceed to say, that as the narrative begins very abruptly, you will find it necessary to have some little personal account of the parties concerned, which I will lose no time in giving you. The mother of the party you know so well I need say nothing further of her than that she was about 27 when these events occurred; what her age is now, I must be excused telling, inasmuch as it has nothing to do with the story, [iv]and it is her own concern, and it will too certainly expose the time of the narrative and other things she wished left in obscurity. Mrs. E., the little mother, as she is called by every one, was the second in command. A greater contrast to her cousin could not exist. Short, and rather stout, she trotted by the side of her companion, as the little hippopotamus by the side of the giraffe. Both their eyes were dark, but the mother's were soft, and the little mother's so brilliant when she fixed her eyes on you, you must tell what you thought, as they penetrated into the heart. Her broad forehead showed the prevalence of the intellectual powers, and the reliance on her own sense and judgment. To be sure some people called her very masculine, and it is true that, when equipped in her riding gear, and ready to get into her second home (the saddle), she certainly slaps her tiny boots with her whip, walks round her horse, examines his legs, and questions her groom as to the throwing out of curbs, and other mysteries, known as stable lore. The horse has his nose twitched that she may get into the saddle before the usual kicking scene commences; once there, he may do what he likes, she is part of her horse, and enjoys his gambols as much as himself. When in female garments, though somewhat brusque in manners and blunt in speech, she is a true woman, and as feminine in heart as the fairest and most[v] delicate among the sex. Madame, the governess, must occupy our attention the next. She was the kindest, best, most loving guardian over her flock, and seemed to have but one unhappiness in the world, and that was her utter inability to keep in order and understand one rebellious pupil among them. But I will not tell tales out of school. Sybil and Serena were the mother's young sisters, 13 and 14 years of age, innocent, gay, and happy creatures, blessed with beauty and sense above the common lot. Gertrude, or Gatty, was the child of an old and valued friend. She was about 12, with the wit, the quickness, the sense of 20, and I had almost said the size, for so large a proportion of flesh, blood, and bones rarely fall to the lot of male or female at that age. She was alternately the soul of fun and merriment or the plague and torment of every one about her. She had the judgment of mature age and the nonsense of the greatest baby in her. The mother alone obtained unlimited obedience from her. I am afraid I have discovered the "unruly one," but all the characters shall speak for themselves. The mother's own children were three in number. Oscar, a fine tall active boy, with a grave quick demeanour, but the open brow and frank sweet smile won him the love of every one. Lilly, the little girl, was about 6, a little, loving, winning thing, with eyes like[vi] violets, and long dark rich curls floating all round her, from the middle of which was uplifted a little rosy face, almost perfect in its childish beauty. Felix, the youngest boy and child, was a little, delicate, spoilt fellow, whose face seemed made up of naught but eyes and eyelashes. They were all three quick and clever children; and it was partly for the improvement of the little boy's health the voyage took place, the incidents of which are mentioned in this book. Zoë and Winifred were two little nieces. The former a grave, little, quiet picture of a sweet Madonna, and the latter a little, sparkling, merry pet, with the quick action and grace of a fairy. Madame does not know it, or think we guess it, but Winny is certainly her pet. Mrs. Hargrave, the lady's maid, and Jenny, the little pet nurse, concluded the females; while a fine, tall, handsome, athletic gamekeeper formed their only male attendant. Now, having said my say, I leave you; but you must be answerable for the faults of this journal if you will publish it; nothing could be more irregular and hasty than its compilation. With this burden on your shoulders, dear friend, believe me, thine in all pity and affection,

On the 3rd of May, 183—, we embarked on board our pretty yacht, "La Luna," the crew of which included all the party mentioned in the preceding pages, besides those necessary to work her. These consisted of a captain, two mates, a boatswain, fourteen seamen, a cook, a steward, and my son's gamekeeper. Captain MacNab was a remarkably nice, active, bluff, plain-spoken man. It was easy to be seen that he was not too much pleased at commanding a company composed so entirely of women and children; neither do I think he would have undertaken the charge had we not expected Sir Walter Mayton, my children's guardian, and Mr. B., their tutor, to make part of the live stock. The former was prevented accompanying us by domestic matters; the latter from his father's death. But we made arrangements for both to join us at Madeira, for it was not deemed advisable to wait the month it would take Mr. B. to settle his father's affairs and provide a home for his sisters. The weather was so beautiful it was thought we could easily spend a month in the Mediterranean, previously to extending our voyage across the Atlantic; besides I was anxious to see the promised roses restored to my little son's face, and, without being foolhardy or presumptuous, I could not entertain the[8] least idea of danger. Our first mate, Mr. Skead, was not only extremely skilful, but the nicest merriest person on board, being quite as ready to be the boys' play-fellow as they could be to have him. Mr. Austin was the second mate, a grave religious person, who kindly acted chaplain for us. Of the seamen I need say nothing, but that they were all picked men. Alas, when I recall that day, and see so vividly before me all their rough but honest manly faces, and remember the close intimacy that, being sharers in one common home, participators in all things alike, engendered, I cannot but mourn over each face as I recall it to memory. In the few months we were together each seemed a part of the family, and in the sudden severing of our lives and fates mournful thoughts will arise as to what can have been the fate of those in whom we were so interested. But I must not anticipate, and, moreover, my task is a long one, and I have no time to spare lingering over the past. Our cook was a black man, called Benjie, which rather disturbed the peace of the little girls. They could not think the white rolls were really made by his black hands, and only his extreme good nature and willing activity caused them to be in any degree reconciled to having a black man for a cook. He was a very good one however, and willingly would we, many years after, have hailed his black face and white teeth with the joy of a dear friend. Smart, the gamekeeper, was a fine, tall, handsome man, of Gloucester make and tongue; he was quite a character in his way, and the contrast between his fear of the sea, his illness at the[9] least gale, his utter ignorance of anything nautical was very great, when we thought of his courage, strength, and skill on shore, in his own vocation. Under his care he had two large dogs, half blood hounds half St. Bernard, their names were Bernard and Cwmro. But I must describe our vessel:—La Luna had been built expressly for her present purpose, in the river Clyde; she was of nearly 200 tons burden, three-masted, beautiful and elegant in her appearance, and nothing could exceed the convenience and comfort, combined with strength, with which she was fitted up; we had a deck house, surrounded with windows, so that we were shaded from sun and sheltered from breeze, and could see in every direction each pursuing his or her favourite occupation, and yet losing none of the beauties and wonders of the ocean; near the deck house were two berths, one for Captain MacNab, the other for Mr. Austin; down stairs we had a saloon, the length of which was the width of the vessel, and about twelve feet across; on the upper end a smaller saloon, or drawing room, the sofas of which made up four berths; the three girls used this room, and it opened into the stern cabin, where Jenny and the three younger girls slept, and through which the rudder came; at the other end was a double cabin, which served for my cousin and me, opening into the bath room, beyond that was the boys' cabin, and on the left hand side of the stern cabin was Mrs. Tollair's cabin; in the other part of the vessel were four other cabins, a steward's or servant's room, besides the seamen's berths, here also were two very excellent deck[10] cabins for our two gentlemen whenever they joined us. We had fitted up the whole of the saloon with bookcases, of which one was devoted to the children's school books, drawing materials, and everything of that sort they might require. Our travels were at present not only indefinite as to time, but equally so as to place. We had a piano and a small hand organ, which could be carried on deck.

It would be impossible to convey any idea of the bustle, the noise, the confusion, the pleasure, the novelty that possessed everybody and everything the few days before we sailed. The leave-takings were the most painful, for having the care of so many who left the nearest and dearest ties behind them, on a voyage, the singularity of which invested it with a certain degree of mysterious danger, the nature of which no one could define, and which I now for the first time felt. All this gave a degree of sadness to the feelings of the whole party as we watched the English coast fading from our sight. I sat on the deck until a late hour recalling the happy and cheerful "God speed you" that my mother gave us, the more grave and solemn farewell of my father, whose foreboding mind looked farther than ours did. And then I recalled the parents of those with me; the hearty and oft-expressed wish of Gatty's father, high in honours and public esteem, to accompany us, the tearful farewell of her mother, dear Winny's merry and light-hearted mother, while her father bid her remember, during her long absence, the lessons of[11] goodness and high principle he was always so anxious to inculcate in her. My brother and sister-in-law had been prevented coming to wish Zoë farewell, on account of the illness of one of her brothers. I could not but think this as well, for her mother's delicate nerves could never have borne the parting from a child so beloved, and Zoë's leave to come would have been rescinded at the last moment. Poor child! I know not whether to wish it better to have been so or not. Dear uncle P. came to wish his daughter, my cousin, good bye, and to promise once more a father's and mother's care over her two little children during her absence. I could not help being amused at his sometimes expressing a wish to go with us, and the next minute scolding us for doing anything so mad. Well, we were off! the last adieus were said, the last looks given, the last words spoken. We were off! The die is cast, and it seemed strange to me that now and only now did fearful doubts, and vain regrets, and sad forebodings oppress my heart, and take possession of my mind. With striking vividness I recalled how, mainly to please myself and amuse my mind, I had projected and finally carried out this expedition; how I had covered my own private wishes and thoughts under the plea of the good it would do my little boy, the benefit it was to all young people to enlarge their minds by travelling and experience, the novelty of the adventure, and the sort of certain uncertainty which was to attend our steps and ways during the next eight months, thus giving the charm of novelty and singularity to the whole scheme. I know not how[12] long I should have dwelt on these circumstances, had not the children come to wish me their wonted good night. Schillie declared I had moped enough, the girls were eager that together we should take our last view of England, for the breeze that carried us now so fast through the water bid fair to take us soon out of sight of land. The young soon lose the painful feelings of parting; besides, they were so delighted at being really off, they had been so fearful lest anything should occur to prevent one or all going, so as to destroy the unity, if I may so call it, of the party, that unmitigated pleasure alone pervaded them. This buoyancy of their feelings had as yet prevented any symptoms of illness, and I don't think there was a pale face amongst the party, save the little invalid and Smart, the gamekeeper. He sat silent and amazed between his two dogs, and, could we have analyzed his feelings, I have no doubt we should have been privy to most curious and contradictory ideas. Qualms were coming over him of various kinds, equally foreign to his nature. Probably, for the first time, he was experiencing fear and sickness at the same moment, and quite unable to understand the symptoms of either. The boys had not yet found out what made their dear Smart so dull and unlike himself, when they were so joyous and delighted. We all rose up, and went together to watch the fading land. Various exclamations proved how much our thoughts dwelt on that beloved shore, and long after my short sight had deemed it passed from view did my dear girls exclaim, "they yet saw it; there were still lights."[13] But Captain MacNab wanted his deck to himself, so with cheerful good nights, the moon being up, we descended to take our first meal on board, and use those narrow couches at which we were so much amused, and which the children had been longing to try from the moment they came on board. Such a noisy tea never was, interrupted now and then by a lurching of the vessel, which was such a new thing to us that all started, some in fear, some in fun, and some, I must own, with other feelings not very agreeable. The oddity of having nothing steady on our swinging table, the laughing at the pale looks that flitted across the faces of others, the grave determination with which little Winny declared "that now she was really a sailor, she would only eat ship biscuit," caused intense merriment. But ere tea was over one or two of our party disappeared, and when twelve o'clock arrived Captain MacNab had La Luna all to himself and his men, for the feminine crew were deep in slumber, caused by the, to them, unusual motion of the sea, and the unwonted excitement of the day.

May 4.—The next morning there were many defaulters, myself amongst the number. In lieu of the laughter and joy of the preceding evening, there were groans, and moans, and beseechings for tea or a drink of water. Sybil, Gatty, and Serena all rose valiantly; Gatty scornfully repudiating the possibility of being ill. But it was in vain, "the loftiest spirit was lowliest laid." The little girls rather courted the notion. Being ill in bed of course precluded the idea of lessons, with which a certain portion of every day had been threatened, and as they lay in bed thus they discoursed:—

Zoë.—"I really do not think it will be pleasant if we are to be like this all the time."

Lilly.—"Oh, Zoë, I am so snug, I have got a nice book to read, and there will be no playing on the piano to-day."

Winny.—"Oh! I am very sorry for that. If I did not feel so funny, I should like to go and play very much. But I am glad we are to have no French. Jenny says Madame is very ill indeed, and I think I heard her groan once."

Zoë.—"Groan, did you? then she must be very bad. I don't wish her to groan much, but I don't mind if she is sick always from ten until two. You know mother[15] promised we should do no lessons after two. Here is Jenny. Why, Jenny, what is the matter with you?"

Jenny.—"Indeed, Miss, I don't know; but just as I was fastening Miss Sybil's dress, I felt so queer, and I was so ashamed, I was obliged to sit down before all the young ladies."

All the little girls at once exclaimed, "Ah, Jenny, Jenny, you know you are sea-sick." "No, indeed, young ladies," exclaimed Jenny, vehemently, "I am sure it is no such thing; but Master Felix would have some cold beef with Worcester sauce for his breakfast, and that gave me a turn, it has such a strong smell." But ere Jenny had well got the words out of her mouth, nature asserted her rights, and after an undeniable fit, she reeled off to bed, and was a victim for three days. Hargrave, my maid, being of a stolid, determined, sort of stoical character, announced her intention of not giving way; and though a victim, or rather martyr, she never suffered a sign to appear, or neglected one thing that she was asked to do, or showed the smallest feeling on the occasion beyond a general sense of dissatisfaction at all things connected with the sea. But of all our sufferers none equalled my poor cousin. Not a word was to be got out of her, but short pithy anathemas against everybody that came near her, everybody that spoke to her, every lurch the ship made, every noise overhead; an expression of pity caused an explosion of wrath, a hope that she was better a wish that she was dead, and an offer of assistance a command to be gone out of her sight. Neither of the boys suffered[16] in the least. And now the increased motion of the vessel, the noise overhead, and various other signs told us that the lovely smooth ocean, on whose bosom we had trusted ourselves, for some cause unknown to us was considerably disturbed, internally or externally. It was impossible for any land-lubbers to stand; it was equally impossible to eat in the form prescribed by the rules of polite society, food being snatched at a venture, and not always arriving at the mouth for which it was originally intended. One or two were pitched out of their cots, and a murmuring of fear that this should be a tempest, and that we were going to be wrecked, caused a message to be sent to Captain MacNab to know whereabouts we were, for no one liked to be first to acknowledge fear or expose our ignorance to the Captain, who had good-humouredly rallied some on what they would do and say in case of bad weather. Therefore the question of whereabouts are we seemed a very safe one, likely to obtain the real news we wanted without exposing our fears to the captain. In answer, we received a message to say we were near the Bay of Biscay and as there was a very pretty sea, we should do well to come up and look at it. "Come up and look at it?" that showed at once that no shipwreck was in contemplation. But how to get up? that was the question. The message, however, was dispatched round to the different berths, with the additional one, "that the mother was going immediately," that being my title amongst the young ones, and the little mother being the title of my cousin.[17]

On deck we were received by the captain, who welcomed us with much pleasure, an undisguised twinkle in his eyes betraying a little inkling into the purport of our message. To our amazement, he and the sailors seemed quite at their ease, walking as steadily as if the vessel was a rock, and as immoveable as the pyramids. But what a sea! I looked up and saw high grey mountains on all sides, and ere I could decide whether they were moveable or my sight deceptive, they had disappeared, and, from a height that seemed awful, we looked down upon a troubled, rolling, restless mass of waters, each wave seeming to buffet its neighbour with an angry determination to put it down. In the midst of all this chaos, one monster wave rose superior to all the rest, and rolling forward with giant strength and resistless impetuosity, threatened instant destruction to the vessel. A cry, a terrific roll, a shudder through the vessel, and again we were in the valley of waters; and during the comparative lull the captain roared in my ear, "Is it not a pretty sea, Madam?"

We can now laugh at our fears, and the awe-struck faces we all presented, but it was many hours ere some of us recovered ourselves, and for this show of timidity Gatty scolded Sybil.

Gatty.—"How can you be such a goose, Sybil? Why, you are trembling now."

Sybil.—"No, I am only a little cold; but you know, Gatty, that was such an awful wave, if we had stretched our necks ever so high we could not see to the top."[18]

Gatty.—"Well, and what did that matter? It was a glorious wave, a magnificent fellow, I dare say a tenth wave. If we had been walking on the sea shore we should have counted and known."

Sybil.—"But I could not tell how we were ever to get to the top. I thought we must certainly go through it, or it would go over us."

Gatty (laughing).—"Serena, do come here, Sybil is talking such splendid stuff, and, moreover, she is frightened out of her wits, and I do believe wishes herself at home."

Serena.—"Oh dear! I am so ill; going on deck has quite upset me, and I am worse than I was."

Gatty.—"Now, whatever you do, don't go and be so foolish, Serena. I shall have no pleasure at all if Sybil is frightened and you are ill. Get up, and eat a lot of roast beef with heaps of mustard and you will be quite well."

A little small voice called to Gatty, and also asked for beef and mustard. "I am sure, quite sure, Gatty," said the little speaker, Winny, "it will do me a great deal of good." "Ah," said Lilly, "I wish I was out of this place. Do, mother, ask the captain to stop and put me down somewhere." This little idea caused infinite amusement. Time, however, went on, and cured us all. We had lovely weather, and began to keep regular hours, and have allotted times of the day for different things. All attending, whatever might be our occupations, to the captain's summons; for when anything new was to be seen, any wonders of the ocean,[19] any curious bird resting its weary wings on the only haven in sight—our little vessel, any furling of sails, or any change, so did the good-natured captain send for us, and we joyfully obeyed the summons, listening to all his wondrous tales, watching the rolling of the porpoises, and the wondrous colours of the sea. As we approached a hotter climate, everything became, in our eyes, objects of new and strange interest. In this manner we reached Gibraltar, and landed for the first time, having been thirteen days at sea.

May 16.—Gibraltar.—I, for one, was very glad to land, for somehow on board ship one never seemed to be able to finish one's toilette with the degree of niceness necessary, a lurch of the ship very often caused an utter derangement, a rolling sea made it a matter of great difficulty even to wash one's face, and as for tidying the hair that had been given up, and those who did not wear caps enclosed their rough curls in nets. We therefore migrated to the principal hotel, leaving the two boys, at their own request, on board, under the care of Jenny and Smart. The three elder girls were to wait on each other, and each take a little girl in their charge, while Hargrave waited on the three elderly ladies. We were objects of great curiosity, and many people supposed our party to consist of a school. They were more surprised at hearing that La Luna belonged to the school. The visitors on board of her became innumerable, causing the good-natured captain a world of trouble. Every day he came and reported himself, as he called it, to his commanding officer, meaning myself and brought an account of the boys, or one with him; and it was most curious to see this great rough captain take each little girl up in his arms and kiss her quite gently, always expressing a hope to each that they[21] were not getting too fond of the land, but would soon return to their ocean home, as he was quite dull without them. Whatever misgivings he might have had on starting, they had all given way to an interest and affection for us all, that made it quite a pleasure to us to communicate with him.

We took advantage of our first landing to write letters home, which, having been preserved with sorrowful care, have now become agreeable memorials of our adventures, and may be interesting, as their own letters will best explain the individual character of each of those who were now on their way towards adventures strange as unexpected. The letters of the elder portion of our party contained but a description of Gibraltar, which is well known to most people. Sybil's letter was as follows:—

"Gibraltar, May 16, 18—

"My dearest Mamma and Sisters,

"Here we are safe on dry land again, and who would have believed a fortnight ago that we should have been so glad to get out of our dear La Luna. But we don't make half such good sailors as we expected; and how Em would have laughed could she have seen all the queer looks and sad faces which possessed the merry party she had so lately seen. But here we are really on dry land, and at Gibraltar, at the summit of all our present hopes, and charmed enough to make us forget all the horrors of the sea, and[22] even think we could undergo them twenty times for such a sight. We came into the harbour last night, and landed as soon as we could collect our wits, and mother collect us; Madame has been at Gibraltar before, and so ought to have had the use of hers, but knowing her propensity to lose her way, we made Hargrave look after her, while we three elder girls each took a little child. Both the mothers looked after our things. The boys and Jenny were left behind. So we landed just before gun fire, passing through the long rows of houses, which looked so strange to our wondering eyes, piled one above the other, and as we were passed and stared at by numbers of odd queer-looking people, we quite fancied ourselves in a dream, or realizing the Arabian Nights. At last we halted at our hotel. Our sailors deposited our boxes, and seemed to wish us good night with sorrow. We had a famous tea, if I may so call such an odd mixture of eatables, and went to bed, hardly believing we could be in Gibraltar. This morning we were awoke by some little voices round our beds—'Oh, auntie, dear auntie, do get up; this is such a lovely place, and so odd. There are such rocks, and oh, auntie, such queer people. I saw a man in a turban, and there is a black man in the house, and——' 'Hush, little nieces, how are aunties to get up, if you chatter so? rather help us to dress, that we may see the wonderful things too.' We found our two mothers in the pretty drawing room. Three large windows looked out upon the busy town and blue sea below. The little mother was out in the balcony, in a perfect[23] ecstasy of delight. A call to breakfast was obeyed, though we could hardly eat, the chicks jumping up every minute to look at something new and strange going on below, and the aunties quite wishing that they might commit such a breach of decorum. We were startled out of all propriety at last by a well-known voice sounding under the windows, and a remonstrance which drew us all there. Looking down, we beheld Felix seated on the top of a most extraordinary vehicle, the driver of which he had superseded, and was trying to persuade the lumbering old horse to get on. Smart was behind vainly endeavouring to persuade his young master to come down. A glance at the drawing-room windows effected what Smart's entreaties had failed to do, and the young pickle was soon at high breakfast, and had demolished a pretty considerable quantity ere his steady elder brother appeared.

"We have just returned from our first expedition so charmed, even our excited imaginations came not up to the beautiful reality. The town is a very curious one. A long street composes the principal part. Almost all the houses are painted black, with flat roofs. The shops open to the street. But the rock itself! My dearest sisters, you cannot imagine anything so exquisite as the tiers upon tiers, the masses of granite or marble rising one above another until one's eyes ached in counting them. I think if our party are always as wild as the fresh air, the beautiful scenery, and the new sensations caused to day, our mother will[24] repent her responsibility. Even the quiet Zoë was roused, and her exclamations were as rapturous as Winny's. Felix's feats of climbing were frightful; we were never quite sure where to look for him. If Smart had not kept his eye on him, and threatened him with sundry punishments, I don't know in what mischief he would not have been. He is much more afraid of Smart than he is of his mother. Lilly's head was full of some classic stories which she had picked up somewhere, the scene of which she was quite sure was in Gibraltar, and each auntie in turn came in for a bit of the story, which might have created a sensation at any other time or in any other scene but this. So you may imagine us now, all so happy, so weary, so enchanted, so sleepy, but wide-awake enough to be able to send the dear party at home a bit of our pleasure, and the wish that they were all with us to delight also in such scenes. I don't think the mother will ever get us all away. We have quite forgotten our pretty La Luna; indeed she is at present as little thought of as her great prototype in broad daylight. So I will now say good-bye, hoping you will set down all deficiencies and incoherences in this long dispatch to the new and delightful feelings such a place and such a new pleasure have produced in our wondering heads. But in Gibraltar as at home, you must believe me ever, dearest mamma, your dutiful and affectionate daughter, and dearest sisters, your loving and affectionate sister,

My eldest son's letter to his grandpapa was as follows:

"Dear Grandpapa,

"I like the sea quite as well as I expected; but I would rather go out shooting at home. I hope mamma, however, will allow us to go to the Cape or Canada. Smart says he should like to shoot a bear, and I wish to kill an elephant. In the Bay of Biscay we had a rolling sea. The captain told us the waves were 30 feet high; the wind was very great, and blew from the South-West; but the captain did not seem afraid, he laughed and liked it, so I thought it better not to be afraid either. But Smart was very ill, and said, whenever we spoke to him, 'Oh! I wish I was at home with my old woman.' Felix told him he was a coward and afraid; but he said, 'I ain't afeard, but I be going to die, I be sure.' The dogs are very happy and so is the cow; we feed her every day, and she knows us quite well; she has not been sea-sick, or the dogs, or Felix and I, or the captain and sailors, but I think everybody else has. Pray give my love to grandmamma and my aunts. I am tired of this long letter, and I think you will be also. I remain, your dutiful and affectionate grandson,

Gatty's letter was to her sister:—

"My Dearest Liffy,

"This is such glorious fun; but I am so hot. I declare if I stay here much longer[26] I shall flow away, and nothing be left of me but a rivulet. I eat oranges all day long. We have a basket full put by our bedsides at night, and I never leave one by breakfast time if I can help it. It is a horrid nuisance being so sick at sea. I really thought in the Bay of Biscay that I should make a fool of myself and wish I was at home again. I don't like this place much, one is so stewed; there is not a shadow, all seems baked hard as pie-crust twice done. I like being on the sea better now I have got over being ill; there is a breeze to cool one, besides it is so jolly having nothing to do but watch the waves and the wind and learn to mind the helm. I have made great friends with all the sailors, and they are very nice fellows, all but one crabbed old Scotchman, who says, when he sees us on deck, 'ladies should always stay down stairs.' I crawled up stairs in the Bay of Biscay, because they said it was such a glorious sea, and, at first, I thought we were in a vast quarry of bright blue marble, all the broken edges being crested with brilliant white spar. Suddenly we seemed to go over all, all my quarry disappeared, and I was as near as possible going headlong down the companion ladder, and if I had how they would have laughed. The captain said the ship was on an angle of twenty degrees, what that means I cannot precisely say, but leave you to find out. I can only tell you I thought we were topsy-turvy very often, and I hope we shall not experience any more angles of that kind again. Sybil was awfully frightened, and as white as a sheet. Serena was too ill to care whether the ship was in angles or[27] out. Felix is such a jolly boy, and likes the winds roaring and the waves foaming, and he struts and blusters about as if he was six feet two, and stout in proportion, instead of being a shrimp of the smallest dimensions. He is getting a colour though, and his mother looks at him quite happy. Winny is such an innocent little donkey, so quaint and matter-of-factish.

"I suppose you don't care to hear about Gibraltar, you will get a much better account in some Gazetteer than I can give you; I hate descriptions. However, I'll look in our Gazetteer, and tell you if it is true. All right, very good account. So now I will finish. I hope we shall go across the Atlantic. The little mother is as cross as a bear; but, as she cannot be so always, we are looking out for a change of weather. You know I never can make civil speeches, so please say everything proper for me, including my best of loves to papa and mamma. Ever, old girl, believe me your most affectionate sister,

I think the three letters I have given you will sufficiently explain the feelings of our party. We now retraced our steps, though I should have much liked to stop at Lisbon to see the celebrated Cintra.

We, to fulfil the promises made to our gentlemen, were now obliged to make the best of our way to Madeira. This we accomplished within two days of the time we had promised to meet them. But alas! instead of having to welcome them, we received letters, stating that their joining our party must be again postponed, from circumstances needless to mention, and that we must either cruise about for another month or fix some spot where they could meet us at the expiration of that time. Having now become a nautical character, I may be excused saying "that I was quite taken aback." What to do, where to go, or how to manage, I knew not. But to proceed. After a variety of consultations, a vast quantity of advice from all sides, we, backed by our captain's wishes, and rendered rampant by the stretch we had given our hitherto home-clipped wings, decided that we would cross the Atlantic. So great a change had taken place in the captain's mind regarding ourselves that I am not quite sure he mourned at[29] all for the defalcation of our male escort. He had us all to himself now; and, in recommending us the trip across the Atlantic, he reminded me that my brother was stationed at Rio Janeiro, being captain in H.M.S. C——, and that we might cruise up towards North America, and pick up the gentlemen, who, coming from England in the fast-sailing packet boats, would not be more than a fortnight or three weeks at most on the voyage. Of course all the children were wild to go. Remaining in the Mediterranean was voted dull and stupid. How charming to go to America, to see things much more uncommon, much more curious. Everybody could and did see the Mediterranean; it was quite a common yacht excursion. Besides, as I overheard Gatty say to her companions, "Just think, Girls, what a bore it would have been, if, in a month or two's time, our mother should have got tired of the sea, or the little mother continued, every time we have a gale, to get sea sick, they would have ordered us homewards, without consulting our wishes, and at the end of three months we should have been in stupid England again."

Sybil.—"Stupid England!"

Gatty.—"Stupid England. I did not say stupid England, did I?"

Sybil (much shocked).—"Yes, Gertrude, you did."

Gatty.—"Then, Sybil, I am very sorry. England is anything but stupid. It's a glorious place. It's a delectable place. It's a place that if any one dared to say a word against it, I really think I should feel very much inclined to——"[30]

Sybil.—"Well! What?"

Gatty (softly).—"Why, I should like to knock them down; only don't mention my ideas. Madame will bother me, and say it is unladylike; and perhaps she will give me Theresa Tidy's maxims to do into French as a punishment."

Serena.—"Then we won't tell on any account; such a fate would be so horrible. But I agree with you that it would be dreadfully stupid to go home in three months. Now, if once we get to America, we shall have so much to see and do that the winter would come on, and mother would never trust all us precious people across the Atlantic in bad weather, so we shall have to winter in New York perhaps."

Gatty.—"How jolly! won't I 'guess' and 'reckon' every minute; and won't I fire up if I hear anyone abuse our monarchical and loyal constitution."

Sybil.—"What grand words, Gatty. Where did you pick them up?"

Serena.—"Oh, Gatty is so loyal, that I think she will be quite ready to do that which we promised not to mention a little while ago, if——"

Gatty.—"Hush, hush, Serena, you will get me into a scrape. Don't you know everything is heard in this horrid—no, no, not horrid—sweet, charming, dear, darling La Luna. You know what I mean, so hold your tongue."

Therefore, across the Atlantic, accordingly, we pursued our merry course, previously writing letters to detail[31] our plans, to describe our pleasures of all kinds, and to appoint a place of meeting.

What can express the delicious pleasure of the sea in a tropical climate. The soft trade wind blowing us gently but swiftly through the water, fanning every limb, and filling every vein with the very meat, drink, and clothing of air; everything around, above, below bathed in brightest purest sunshine; the still life, consequent upon the heat, which pervaded the vessel, each person enjoying the unwonted luxury of enforced idleness in their own way; the very barque herself seeming to sleep on her silent course through the parting water; and as I raised myself from the couch where I had lain down to read, I could not help being struck with the pretty picture the vessel presented. My cousin was reclining not far from me; her book had fallen from her listless hand, her bright searching eyes, so restless in their intelligent activity when open, were closed, her flushed face shewed she slept. Madame was quietly pacing up and down, shaded from the sun by a great parasol; to her the heat was soothing and agreeable, for she had lived much in India, and it agreed with her better than cold winds and chilling frosts. The three girls were not far off; the two elder ones making pretence to read, but looking more inclined to snooze, while the restless Gatty utterly prevented their pursuing either occupation. From them came the only sounds in the vessel, and they consisted of peevish expostulation, requests to be left alone, now and then a[32] more energetic appeal, a threat to complain to the higher powers, promises to be quiet and still, and this scene at last resolved itself into a promise from Sybil to tell a story, if the restless individual would only be quiet. Immediately a reinforcement offered itself to the party in the shape of Zoë and Winny. A pretty little group of four eager listeners and one inspired narrator soon disposed themselves in the unstudied grace of childhood, and the soft voice was heard in regular cadence, now lively, now solemn, now pathetic, and again elevated according to the interest and pathos of her story. Oscar, in his sailor's dress, with his fair bright curls, his animated blue eyes, added to their picture. But in the distance lay the prettiest group; tired and heated with the noisy play of childhood, the mischievous and excited Felix lay fast asleep with his arms round the neck of one of the dogs, as if he was determined the dog should not play if he could not; but the watchful eye of Bernard shewed that he was merely still for his little master's sake, and that he even looked with a distrustful eye at the measured pacing of Madame, fearing that her slight movement would disturb the profound repose into which his charge had fallen. With her long curls sweeping half over the other dog, and half over herself, lay the tired little Lilly, so mixed with the other two that Cwmro did not seem to think it necessary to keep guard while his companion watched so faithfully, and nothing could exceed the depth of repose and stillness into which they seemed plunged; and in finishing this picture I will end my chapter, for[33] our days glided quietly and deliciously, a time often looked back upon by us as the sweetest and calmest we ever passed, and was only too short in its duration.

There fell upon us a dead calm. The heat was insufferable; the sky was too blue to be looked at; the sea too dazzling to be gazed on; the sun too scorching to be endured. We turned night into day, without mending matters much. Gatty ran about, hot and panting, searching for a cool hole, while she declared that the ship was a great pie, which the sun had undertaken to bake, and that we were all the unfortunate pigeons destined to be stewed therein. "Then," said the matter-of-fact little Winny, "we must put all our feet together, and stick them up in the middle." One day, when we happened to be in that indescribable state—a sort of half consciousness of what was passing around—scarcely knowing whether we were dreaming or waking, we heard a knock at the door, and the hot but smiling face of our captain shewed itself. He was immediately assailed with innumerable questions. Was the heat going? Was the wind rising? When were we to go on? Why did he not whistle for a breeze? Where could we get out of the way of the sun? Was it possible to get into a shade? Could he give us anything to cool us? What would happen if we all went on being baked in this manner? In fact, the purport of his visit to the saloon at such an unusual hour was[35] all but lost sight of in the midst of these queries when I asked him if anything was the matter. "I only wish to look at your barometer; something has happened to mine," was his reply. So amidst an uproar of young voices, with pullings, tuggings, and caresses, for he was a prodigious favourite, he accomplished his object. I was surprised to see such an expression of concern cross his countenance as he gazed at it, and questioning him thereon, he answered, "Why, Madam, I find both the barometers tell the same tale; therefore, what I imagined was owing to a fault in mine, I must now impute to some extraordinary change in the weather."

Gatty.—"I hope then it will be hard frost."

Felix.—"Or a storm, Gatty. I want the wind to blow, and the waves to be mountains high."

Lilly (yawning).—"I wish something would blow, and I wish I had two little slave girls to fan me as they do in India."

Zoë.—"I don't think I should; they would be so hot themselves, poor things, I should be quite sorry all the time."

Oscar.—"I vote for a hard frost, like Gatty, then we should have such splendid skating on the sea."

Serena.—"But, supposing (which I believe is no supposition, but a fact) that the sea freezes in waves, we could not then skate."

Gatty.—"Oh, don't talk any more of ice and frost, it makes one hotter still to think of the contrast."

I proceeded to enquire of the captain what change he expected.[36]

Capt.—"Madam, it must be a storm of some kind; I have been becalmed very often, but I never endured such profound stillness and heat as there have been now for some days past. Dear little souls, I quite feel for the young people, Madam."

Mother.—"But, captain, is it likely to be a bad storm, or will there be any danger?"

Capt.—"You are all such good sailors that I am not at all afraid of telling you the truth. Indeed," looking smilingly on the surrounding faces, "I am thinking some of you will be glad to hear we are likely to have a hurricane!"

The babble on this announcement was tremendous. Gatty and Felix shook hands on the spot, and congratulated each other on the probable fulfilment of their secret wishes. Madame turned deadly pale, and sunk into a seat. My cousin tossed up her head, and said "anything is better than this confounded heat." I trembled; the two little girls clasped each other's hands half in fear, half in excitement; Sybil and Serena both looked pleased; and Oscar besought me to allow him to be on deck the whole time, that he might see the hurricane.

Capt. (seeing my alarm).—"You may be sure, Madam, I would not joke if I thought there was any danger. I have been in Chinese typhoons, hurricanes in the Tropics, and storms in the Atlantic, where one would imagine heaven and earth were coming together, and under the blessing of God" (here our captain bowed his head) "I apprehend nothing, Madam, but what care and skill can overcome."[37]

Mother.—"But your face expressed great concern when you looked at the barometer; and, besides, you mentioned the heat and calm as greater than you ever before experienced."

Capt. (half hesitating).—"That is true, Madam, but I am such an ass, I cannot hide the impulse of the moment."

Mother.—"But, tell me, is this the impulse of the moment? Do you not fear a more than ordinary severe hurricane? Remember, you have praised us so much for being such good sailors, and so obedient to orders, that you must put us to the proof; and the more you take us into your confidence, the more well-behaved you will find us."

A number of voices, "Yes do, dear captain, tell us everything. Are we going to have a grand storm? Will there be ice and snow? Shall we have thunder and lightning? Will the waves be one hundred feet high? Do you think the masts will be blown away? Tell us that it will be a magnificent storm, whatever you do," said Gatty, winding up the noise.

Capt. (very much perplexed and anxiously).—"Dear little souls. Ma'am, it does my heart good to hear them. They ought all to have been born sailors, and bred to the sea into the bargain. Yes, my darlings, you shall have a grand storm, no doubt you shall have all your wish, whatever I can do for you, my little angels," and the good captain looked quite benignly at them all, giving great energetic kisses back for all the light rosy ones imprinted on his great Scotch face.[38]

My cousin laughed as she turned to me and said, "Good as the captain is, I hope he is not really going to spoil those children and conjure up a prodigious storm for their amusement. Now brats, get out of the way, and let us have a little common sense. You think we shall have a storm, captain?"

Capt.—"I fear so, Madam; that is, I don't fear," apologetically turning to the young ones, "but I have no doubt we shall have a storm."

Schillie.—"Then you would advise my betaking myself to bed, I suppose, immediately."

Capt.—"No, Ma'am, no, for I cannot judge when we shall have it, not these twenty-four hours yet."

Schillie.—"But, pray, have you any advice to give us against the storm does come. When a horse kicks, I am well aware that the rider has solely to think of sticking on; but, I confess, storms and their consequences are quite out of my way."

Capt.—"Indeed, Madam, I should be greatly obliged if you would undertake to keep everybody quiet below, the children especially: if they come running up after me, dear little souls. I shall be thinking too much of them to mind my ship."

Schillie.—"Then I will take particular good care they are kept out of your way. I have no mind to lose my life for a parcel of spoilt animals. But, otherwise, you think there is no danger?"

Capt.—"Why she is a good boat, a very good boat; I fear nothing as long as we have room."

Gatty.—"Room, captain, what sort of room?"[39]

Capt.—"Sea room, begging your pardon, Miss. I quite forgot you would not understand me."

Gatty now pouted in mortification that her intended laugh at the captain should be construed into ignorance on her part of what he meant, and the colloquy was broken up by the captain being sent for. We crawled on deck, as a matter of duty, panting and exhausted with doing nothing. Though we had bright blue sky above us, and the glittering sea around us, I never shall forget the brazen, hard, heated look that everything appeared to possess. The sky seemed to be gradually turning into brass, the ship looking like brass, we feeling like brass. It was horrible; and it was with no slight pleasure I heard a moaning wind rise slowly in the night, freshening into a gale by morning. Ere twenty-four hours had passed, with bare poles we were driven through the water just as a child's walnut shell might be tossed on a rough ocean. Here, there, and everywhere the sea rose, each wave with a crest to it madly buffeting and fighting with the others, yet each apparently bent on attacking the vessel, freighted with such precious lives. The wind whistled and roared until every other sound was lost. We could hear it gathering in the distance, then collecting, as it were, strength, rage, and speed as it advanced, it poured all its wrath and fury upon what appeared to us, the only victim with which it had to deal. The noble vessel bent, as it were, her graceful head in deprecation of such furious rage and turmoil, and shivering from bow to stern, would again rise lightly and proudly, as if[40] appalled, but yet indignant at the rough usage she was receiving; yet far above the rattling wind the pealing thunder rolled with majestic sound, while the incessant lightning showed us the mad waves in all their forms. From time to time the captain sent us kind messages. We got used to the noise, uproar, and shocks; but, nevertheless, we could perceive the gale increased instead of abating. We bore it well for twelve hours, not a murmur, not a fear was expressed; but, after a shock, so tremendous that the vessel trembled to her inmost timber, a faint shriek was heard from Madame, this was echoed from the deck, it seemed to strike the ship motionless. As our breath returned to us, slowly and labouringly did she rise, heavy and waterlogged; how unlike the buoyant creature she had been a few moments before. Alas! that fatal cry was not without its signification; a sea had struck her, and in sweeping off seven men, had filled the ship with water, and carried away rudder, deck-house, and everything. Then, indeed, fear took possession of our minds. Amidst the roaring of the wind, the earnest and solemn prayers of Madame might be heard, as she sat in the gloom of the cabin, with ashen face and clasped hands, while the wailing sobs of the little girls came mingled with subdued cries from the elder ones. The two boys sat with faces uplifted, and their large eyes distended in fear and awe, as if their wild wishes had caused this awful tempest. The servants, unable to bear their fears alone, were seated in a distant part of the saloon, the wringing hands of the one and the deep groans of the other testifying[41] the anguish and terror of their minds. Unawed by the dreadful turmoil above and the painful scene around her, Schillie alone seemed fearless and unmoved; steadying herself by the cabin door, she stood erect, and, as she looked at each of us, the calm undaunted expression of her countenance seemed to impart to us the courage her words would have given could we have heard them.

The heavy rolling of the ship became each moment more apparent; the timbers creaked and groaned; as if satisfied with the mischief it had done, the wind ceased its wild uproar, and, during the temporary calm that succeeded, we learned the loss of the seven men, hurled at once into eternity, the wreck of all on deck, and the fatal consequences still more likely to ensue from the sea we had shipped. The pumps were manned immediately, and a temporary rudder made from one of the spars. So little did the captain hide our danger from us that he accepted the offer for those that could to help at the pumps; this enabled him to spare two men for the rudder and other work he thought necessary.

Madame remained below with the children, beseeching for that aid which is equally necessary on sea or shore, and Hargrave, being helpless from fear and despair, remained with her. Wrapping ourselves up in warm close garments, we took our places, two at one and two at another pump, to help the men; and we had the exquisite gratification of finding that our labours were[42] successful, for once more La Luna rode lightly on the waters, and our captain, in the broadest Scotch, which he always used when agitated, expressed his heartfelt happiness, while he let out, in broken exclamations of thankfulness, the fear he had entertained that her waterlogged condition might have proceeded from the starting of some of her timbers; and, indeed, the shocks and buffets she had received from the angry waves, with the straining and pitching, made us, inexperienced mariners as were, wonder, more than once, that she was not riven into a thousand pieces. Many were the fond words and endearing epithets bestowed on the brave La Luna by the good captain while he apostrophized her, as if endued with life and consciousness, beseeching her to hold on yet awhile, by all the good angels in heaven, by the mighty powers of the deep, by the love she bore to those within her, by the affection they bore to her, by the value of their lives, by the preciousness of the little innocent children, by the hopes she had given them of her strength and goodness; while he promised her in return every good thing on sea or in sky, fair breezes, bright sun, and ever-flowing sheet, with the devoted love and affection of all on board.

Towards evening, the moaning wind again rose in furious gusts, and we were recalled from the calm into which we had been sunk by the sudden and awful death that had befallen so many of our companions (a feeling only to be felt at sea) to a repetition of all we had undergone before, save in that one instance. In the language of[43] scripture, "we strake sail, and so were driven." The sky was as pitch, the waves furious, the wind awful. Night and day passed without thought or heed. Working at the pumps had done us all good, diverting our minds from the loss we had sustained, and preventing us from dwelling on the perils surrounding us. But now we had nothing to do, and we experienced, in its full force, that heart-sickness consequent upon hope deferred. Hours sped on, yet still the ship was driven like a mad thing through the water. Bruised and sore, from the various falls and shocks we hourly received, hungry and faint from inability to get the food so necessary for our exhausted frames, death seemed our inevitable doom.

At the end of the seventh day, we were startled by the cry "Land ho! Land, Land." We exclaimed, "we are saved, we are saved!" and, for a moment, there was deep silence, an instructive feeling of gratitude prompted in each breast, young and old, a spontaneous prayer of thanksgiving to the mighty Being in whose hands we were, who was at once our Father and our God. The first powerful impulse obeyed, we had leisure to think of each other. I kissed the little ones, but said nothing. Madame was loud in her rejoicings and thanksgivings, the servants outrageous in their frantic joy, but the dread fear of the past days, the fury of the still existing storm, kept the elder girls yet in a state of subdued feeling. Dashing the tears from her eyes, and assuming an indifferent manner, Schillie said, "Madame, spare your rejoicings until we land; and you howlers," turning to the maids, "keep your noise for a fitting occasion. I imagine," looking at the rest of the party, "our condition is rendered more dangerous by the probability of being driven on shore; when, instead of going to the bottom, like Christians, with whole skins, we shall be dashed to pieces on the rocks, and washed up in little bits."[45]

Felix.—"I hope some of my little bits will get near mama's little bits, and then I shall not care."

Oscar.—"Mother, may I creep up and ask Smart what the captain thinks about the land?"

All.—"Yes, do, do, dear boy."

"Mind you are careful, my darling boy," said the anxious Mother.

The captain came down himself with the boy, and corroborated Schillie's idea, that land was dangerous if the gale continued. "But, thank God," said he, bowing his head, "the gale is breaking; may I see you all down before my eyes, if I am deceived in thinking we shall have fine weather in a few hours; but," continued he, looking round with concern, "what pale faces, what suffering and misery you have undergone. I am a'most done myself," the large tears rolling down his pale shrunken cheeks, "and, but for the lives under my care, I must have given way long ere this. Ye have need to pray yet for succour; we are aye in a mickle mess, shortened in our hands, with work for twenty men, it is not to be expected as nature 'll stand it out. The men are fairly done, and, but for that likely Smart, I ken we should be in a far worse state. I am thinking, leddies, a spell at the pump will no harm you, and gie us a better chance of our lives, while the men get a bit snack. Another six hours will make or mar us; but it's no me as will disguise from any one that she's sprung a leak. All the straining and strammashing she has gone through would have foundered some score of fine boats, but she is a good one, aye, a grand one. So weel ye just come?"[46]

We were awfully startled at the announcement of a leak, but followed him as well as we were able. Lashed to the pumps, we again worked hard, but not as before to reap a reward of our labours in seeing the pumps become dry. At the end of two hours, when we had worked turn and turn about, the captain told us that the water did not gain on us, yet the pumps must be kept going night and day to keep her afloat. How grieved we were to see our kind-hearted merry Smart, who had always looked such a fine handsome specimen of an English gamekeeper, worn down to a shadow, his fine fresh colour gone, his cheeks shrunk and withered, his bright eyes and frank smile vanished, and a care-worn, haggard, gaunt man in his stead. The two dogs were near him, looking famished and subdued. But throughout the whole time, during our greatest danger, he had never forgotten the cow; he remembered how necessary the milk was to the health of his little master, and he had fenced and guarded her stall with sails and straw-bands to prevent her being knocked about; nevertheless, with all his care, she looked pitiable, and was galled and bruised in many places.

Gradually the leaden darkness over our heads seemed to be stealing away, a low moaning sound succeeded to the hollow blasts and whistling hurricane that had been making us their sport. Instead of the violent pitching and tossing that had been our fate for so many days, with the fearful careening over of the labouring ship, we were now going slowly up and down with the swelling[47] rolling waves. Gradually and distinctly the land, that had been viewed some hours before, became more visible, and we beheld what seemed to us a small irregular island, rising very abruptly to the right, and of great height, but shelving off to the left; and, as we approached nearer, we could perceive long breakers dashing for a great distance over the lower part, leading us to imagine that it extended some miles into the sea. Our captain edged off as well as he could, with his crippled rudder and the troubled sea with which he had to contend, because night was coming on. Though the wind was quite subdued, and the sea becoming each hour more calm, the night was an anxious one, and weary enough to some of us, for the pumps could not be left a moment.

The harassing time the young ones had passed made me anxious that they should obtain that rest so long desired, while the age and delicate health of Madame rendered her almost as necessary an object of care; but the maids with my cousin and myself did our duty with the rest in our endeavours to keep the ship afloat.

We were rewarded in the morning by, oh! joyful and beauteous sight, the unclouded and glorious rising of the sun. Months seemed to have passed since we had seen his beautiful face, and the genial warmth and bright beams imparted a glow to every eye and every heart. The cock, so long silent and almost dead with salt water, faintly crowed, the dogs barked, and the[48] cow lowed. When dumb animals thus endeavoured to express their joy and thankfulness, could we be silent? Oh no, words were not wanting to add to nature's hymn, happy and joyful sounds were heard on all sides, and those who could not help it wept the happiness they found themselves unable to express in words.

In us was exemplified the old adage, "that man is but the creature of circumstances." Who could have foretold that in two short weeks we should think so differently, and yet in that fortnight of dark anxiety, undefined dread and forebodings, more distressing than reality itself, we had seemed to live years of misery. The bodily sufferings we had endured from the heat and burning fever of the scorching sun seemed as nothing in comparison with the horrors we afterwards underwent, and it was almost impossible to imagine that we had ever deprecated the bright beams or complained of the genial warmth now so grateful to our feelings.

What happiness it was to hear the joyous voices of the young ones, as each, in their different manner, expressed their delight at the beautiful change. The gentle Zoë clasped her hands with excited joy; Felix flew into his dear Smart's arms, exclaiming "that the sun was shining most stunningly;" Oscar came softly behind me, and with one arm round my neck, whispered "Dear mama, surely we are saved now;" Lilly and Winny ran from one end of the vessel to the other, singing, in clear ringing voices, the morning hymn;[50] while each and all gazed on the surrounding scene with happiness and delight, worn out as we were with aching arms, blistered hands, and utter weariness, we could not be insensible to the beauty of the little island we were now approaching.

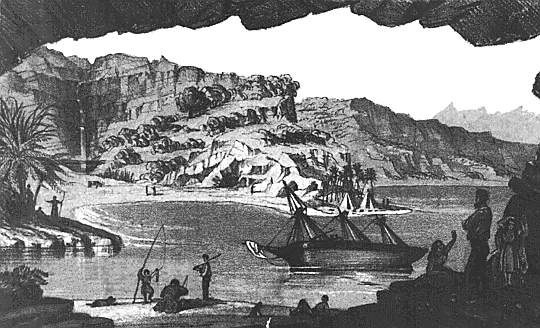

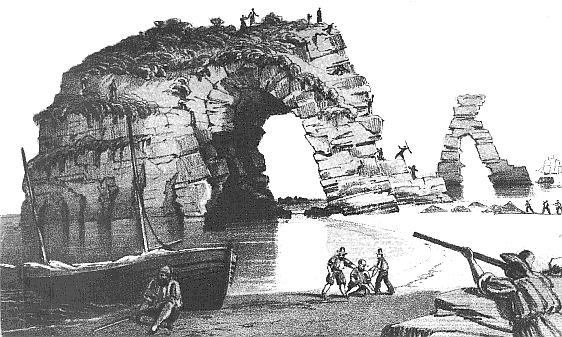

It was seemingly so long since we had seen land that even if it had been a barren rock, we should have hailed it with delight. Yet, with all our love for La Luna, with all our experience of her goodness, beauty, strength, and worth, not a heart beat on board of her, I fear, that did not pant to be on shore. It seemed as if this little island had risen out of the sea for the sole purpose of affording us the rest and peace our shattered condition and worn-out frames demanded. And yet it was curious and half alarming to see this little spot of earth rising so lonely and yet so beautiful in the middle of the sea: like an emerald gem on the vast extent of water it lay calm and alone, no other land in sight, no other object to divide our attention with it. The nearer we approached, the more we became absorbed in our inspection. It grew larger, it appeared higher, we distinguished cliffs or rocks, we noticed ravines, and beheld small bays. The roaring of the breakers was distinctly heard, and the rolling billows, collecting foam as they advanced, seemed to spend their force against the reef of rocks, while they lightly and gently swept on towards the little island, breaking so softly on the sanded shore that they seemed to regard it as a favoured child, whose solitary condition demanded protection[51] and indulgence. Slowly and heavily the laden ship advanced; suddenly we seemed, as it were, to pass a corner of the island, and came upon a view so lovely in its quiet beauty, so unexpected in its richness and colour, so delightful in its homelike appearance, that one cry of admiration burst from all. How exquisite! How lovely! What rocks! What trees! Look, look, a gushing stream, a lovely waterfall! I see birds, bright birds, and beauteous flowers, I am sure! What colours! What a lovely bay! What blue water! What golden sands! Was ever such a scene beheld before by mortal eyes! Such and many more were the exclamations heard on all sides. There hung, in vast variety, gigantic trees, stretching their huge limbs in every direction on the face of the cliff, as if clinging for support. Every here and there verdant spots appeared, like mossy resting places for the weary climber, from whence hung creeping plants, wonderful to us for their size and beauty. In the right side of the bay, the cliffs seemed suddenly rent asunder, and through the opening gleamed a silvery thread, which, advancing to the edge, fell in a rich stream of water from rock to rock, dispersing into a thousand sparkling dancing rills, sometimes lost, then again bursting forth, now shadowed by a huge old tree, then deepening into a quiet smiling pool, until at last tossed, tumbled, and thrown from a descent of a hundred feet, it reunited its troubled waters on the sand, and flowed in tranquil beauty to the sea. The cliffs shelved up higher almost immediately beyond the waterfall, and rounding abruptly on either side towards[52] the sea, they formed a bay or harbour, scarcely half a mile from point to point, though it must have been some miles round it. High on the right hand, which in fact was the sort of corner we had passed, rose abruptly from the sea a gigantic rock separated from the mainland; it had an archway, apparently hollowed by the sea, quite through it, and was curiously picturesque and strange to view. On the left, the bay was also sheltered by rocks, filled with caves and hollow places, but none separated from the mainland. Our captain had been occupied taking soundings ever since we had neared the land, and amidst all our exclamations arose regularly the man's deep voice, proclaiming the depth of the line, with a melodious cadence peculiar to the cry.

But not even that sound or the nearness of our approach to land prepared us for a sudden grating noise, a shock, a succession of bumps that finally left nearly everybody on their faces and the ship perfectly motionless and fast on a sand bank. Those who soonest recovered themselves were greeted by the captain with cheering voice and hearty shakes of the hand. Wiping the numerous drops of anxiety from his brow, he congratulated us on what seemed the climax of our misfortunes.

"All right, all right," he exclaimed, "capitally done; I hardly hoped we should manage it so well. Cheer up, cheer up, my darling," picking up poor little Winny, whose bleeding nose shewed how suddenly the shock had upset her, "we are all safe now. There is the bonny island ready to receive us, and the pratty ship has borne us safe and sound, as far as she weel could, and now she is safe on a soft sand bank, and no harm to speak on. Another few hours, and we wadna hae had hands to shake or mou's to praise God for all his mercies." In answer to my appealing look, he continued, "She could not have floated long, Madam, the pumps are clogged and useless. Every hour was[54] increasing the weight of water. With all my wisdom and knowledge, I could not have saved you had not a merciful providence raised up this picture of 'the fair havens,' like as is mentioned in the holy scriptures, and I bid ye welcome with my auld heart singing for joy. Never mind your bit knock my hinny. Here's a pratty home and a lovely garden come up from the ocean depths to shield and shelter ye; and ye shall have bonny fruits and flowers to pleasure ye, after the strife and turmoil you have been undergoing. But, aye, leddies, what a grand boat this is. I'd wager my mither's silver tea-urn none could have done so weel; she has borne and sheltered us to the last minute, and now she lays us gently and saftly on a nice sand bank, and we may step ashore with the ease and pleasure of grand folk. Oh, she's a darling."

Oscar.—"But she did not lay us so softly, I came down with such force that I am quite sore now."

Capt.—"But, my darling, you would not expect a ship to be so gentle in her manners as your own lady mother. Na, na, she did as weel as she could, and that's better than the best, I'll engage."

Winny (half angry).—"But she made my nose bleed with her great bumps."

Capt.—"And did she not do it on purpose, my precious lamb? How could she have settled herself so fast and high without making a bed for herself in the sand; she's as knowledgeable as a Christian, and there's no denying of it. Most lumbering vessels would have bumped a hole in their bottoms, but I'll be bound she[55] has not rasped an inch of her keel. Here she lays us, and bids us, while she lies doon to rest, to take a snack ashore, and be thankful for a' the mercies showered on our unworthy heads. Good Mr. Austin is gone fra us, Madam, but surely there remains some amongst us to lift the song of praise and glory."

Every heart responded to the good captain's words, and the crippled crew, more alive than we were to the danger we had escaped, flocked from each part of the vessel to join us. The startled birds, unused to human sounds, rose in clouds as the energetic and outpouring spirit of praise rose in the air, fervent in its expression, heartfelt in its depth and feeling.

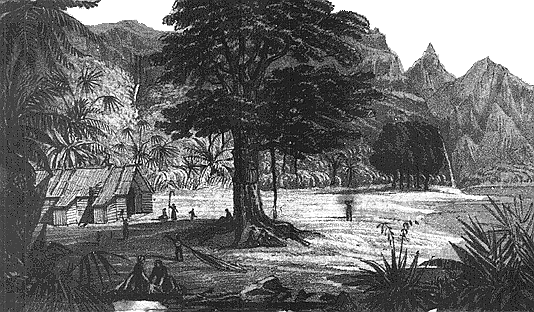

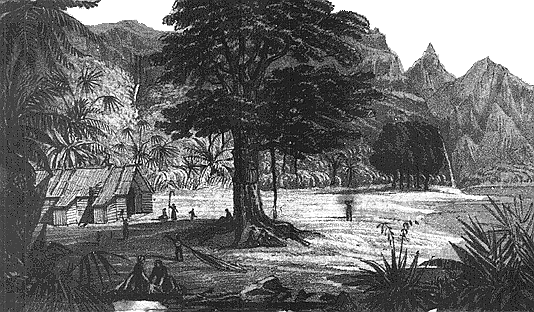

And then our good captain manned the only boat left us, and calling upon me to choose any three other companions I liked, bid me come and take possession of the fair island in the name of the Queen. Calling Schillie, Serena, and Oscar, with the two poor dogs, we got into the boat; in a few minutes we approached, we landed, and seeing the showers of tears that rushed to our eyes, the captain considerately shoved off, and ere we had well dried them, clinging arms and soft voices hung round us, and welcomed us to this land of loveliness and beauty. A very short time elapsed ere we were all on shore, and would have wandered from tree to tree and rock to rock in pleasure too delicious to be described, had not the considerate kindness and untiring exertions of our good captain made us anxious to assist him as well as we could. Everybody was called into[56] requisition, even the volatile Felix and the indolent Lilly were chidden into useful activity, and bestirred themselves to the best of their little powers, on being promised the reward of sleeping on shore. It was nearly noon when we landed, but, in spite of the heat, we worked untiringly, having, first of all, fixed on a dry and sheltered corner on which to have a tent pitched. Under the captain's judicious management, the sailors soon erected a large and commodious apartment, into which we put couches and cushions to serve as beds; a smaller tent, a few feet below us, was prepared for the captain, the boys, and Smart. A large fire was kindled ere night approached to keep off wild beasts, or scare any other unknown enemies. On a shelving rock, against which the waves gently broke, we had our first meal, one never to be forgotten by me, for the many mixed feelings with which it was partaken. All hearts were too full to say much. The overwrought mind of the captain showed itself in his profound silence, while slowly and at intervals a single large tear rolled down his cheeks. Madame swallowed as many tears as tea. Schillie gulped down her food in convulsive starts while she spoke only in short sentences to the dogs, sharply reproving them for nothing. Sybil and Serena both wept quietly, and ever and anon cast fond and anxious but furtive glances at their two mothers. Gatty shewed the workings of her mind by the innumerable holes she was tearing in her poor handkerchief, while she earnestly begged the little girls to eat more, and called them stupid little apes when they did not. They,[57] poor children, would have been joyful and happy, for the feelings of childhood chase each other like clouds on an April day, but the unwonted sight of the kind captain's tears, the uncontrollable feelings that possessed the elder party, gave an awe to the whole proceeding. Oscar and Felix ate and drank to their heart's content, relieving their feelings by occasional visits to Smart, who sat at a little distance with some of the sailors. Such a state of feeling could not last. Our meal ended abruptly, and ere the lingering glory of the sun had wholly left the sky, all the worn frames and overtaxed hearts sought the repose so necessary for them, and, save two faithful watches by the fire, deep sleep fell on all the party.

I awoke in the morning, hardly at first comprehending where I was. On rising, I found myself alone, no sound broke the stillness, no sight met my eyes to assist me in restoring my still dreaming thoughts. After passing some moments in endeavouring to recollect myself, I opened the door of the tent. High and dry on a sanded bank lay La Luna, almost on her beam ends, while active figures were busily employed in her. The little boat had just left her laden with a heavy cargo. Smart and the two maids were apparently waiting to receive what she brought, and assist in unloading her. Scattered in numerous and pretty groups along the shore were all my loved companions. I slowly and mechanically counted them, as if I feared from the unwonted stillness some were missing; but they were all there; I thanked God, and sat down to recover myself. One of the dogs barked, and I saw my cousin run forward to silence him. The little girls were feeding the ducks and chickens, at least two were, while the third was wandering close to the waves at some distance. The boys were one rubbing the cow down, the other feeding her with fresh grass, for which she eagerly pursued him. Schillie walked slowly to the water's edge, and began to make ducks and drakes, as it is called,[59] with a stone, apparently trying to hit a dark object that was moving in the water. The dogs were going in after the stones, when a shout from the vessel roused her. Pointing to the black object, of which now there appeared many, vehement signs were made to her to forbear. The noise reached the ears of all, and they came each from their separate occupations to know what was the matter, and I also walked from the tent for the same purpose. The moment I was perceived they all uttered joyful cries, and ran towards me, expressing their pleasure that I was at last awake; and I then learnt that the cause of their great silence was a wish to leave my repose as undisturbed as possible. I thanked them all, and was greatly relieved; and now there was no end to the gabble, which nearly made us forget the cause which had first broken the stillness.

But Smart came, sent by the captain's orders, to tell us not to throw more stones, or allow the dogs to go into the water, as the odd black things we saw were sharks. Some of the party were aghast, and some delighted at the notion of being on such familiar terms with creatures of whom we had only before read. We sent a message back to the captain to come to breakfast, which had been prepared under a vast plane tree, whose huge branches afforded us delightful shelter. He soon arrived, and greeted us all, in famous spirits. He shook our hands until they ached, he kissed the children a dozen times, and he talked broader Scotch than we had ever heard him do yet; also, he drank about fifteen[60] cups of tea. We all did ample justice to our breakfast; and I was glad to see poor Madame quite merry, roused by the mirth and noise of the children.

Gatty.—"What a jolly island this is."

Oscar.—"Yes. Should you like to live here?"

Gatty.—"I'll be Robinson Crusoe, and you shall be my Man Friday."

Winny.—"You must be Mrs. Robinson Crusoe, Gatty, because you are a woman."

Mother.—"Then I suppose we had better go away, and leave you two here."

Oscar.—"Oh no! don't do that, but we will go and live at the top of that rock, and make believe to be Crusoe and Friday; only, Gatty, if I let you be Crusoe, you must let me have a gun, and I must not sit at your feet, and have to read, because I can do that already quite well. The best thing will be for us both to be Crusoe, and have no Friday at all, because I shall have to black myself."

Sybil.—"And I know that won't please you at all, you little Eton dandy, with your smart waistcoat, white tie, and shining boots."

Oscar.—"Why you know, aunt Sib, we are no longer sailors now. We must dress as shore-going folks. Besides, we don't know if there may not be company here."

Madame (turning quite pale).—"Oh dear! Do you think there are any savages likely to be near us. I have such a dread of them."

Capt. (laughing).—"Why, Ma'am, from all I could[61] see of this island, there isn't much room for them and us, and there cannot be many of them at any rate. If there are, they will show themselves soon."

Schillie.—"I would advise an exploring excursion, that we may see who has possession of this island besides ourselves. It would be as well to know if we have foes, either man or beasts. I know one person," with a slight glance at me, "who will be as fidgety as she is high if her mind's not at rest. She'll see a savage in every bush, a tiger behind every stone, and sharks walking on the sand swallowing brats like pills. It did not seem very large, captain, though we can hardly tell now, walled in as we are by these great cliffs."