The Project Gutenberg EBook of Stories of Animal Sagacity, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Stories of Animal Sagacity

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: Harrison Weir

Release Date: October 17, 2007 [EBook #23067]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STORIES OF ANIMAL SAGACITY ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

WHG Kingston

"Stories of Animal Sagacity"

Chapter One.

Cats.

I have undertaken, my young friends, to give you a number of anecdotes, which will, I think, prove that animals possess not only instinct, which guides them in obtaining food, and enables them to enjoy their existence according to their several natures, but also that many of them are capable of exercising a kind of reason, which comes into play under circumstances to which they are not naturally exposed.

Those animals more peculiarly fitted to be the companions of man, and to assist him in his occupations, appear to possess generally a larger amount of this power; at all events, we have better opportunities of noticing it, although, probably, it exists also in a certain degree among wild animals.

I will commence with some anecdotes of the sagacity shown by animals with which you are all well acquainted—Cats and Dogs; and if you have been accustomed to watch the proceedings of your dumb companions you will be able to say, “Why, that is just like what Tabby once did;” or, “Our Ponto acted nearly as cleverly as that the other day.”

The Cat and the Knocker.

When you see Pussy seated by the fireside, blinking her eyes, and looking very wise, you may often ask, “I wonder what she can be thinking about.” Just then, probably, she is thinking about nothing at all; but if you were to turn her out of doors into the cold, and shut the door in her face, she would instantly begin to think, “How can I best get in again?” And she would run round and round the house, trying to find a door or window open by which she might re-enter it.

I once heard of a cat which exerted a considerable amount of reason under these very circumstances. I am not quite certain of this Pussy’s name, but it may possibly have been Deborah. The house where Deborah was born and bred is situated in the country, and there is a door with a small porch opening on a flower-garden. Very often when this door was shut, Deborah, or little Deb, as she may have been called, was left outside; and on such occasions she used to mew as loudly as she could to beg for admittance. Occasionally she was not heard; but instead of running away, and trying to find some other home, she used—wise little creature that she was!—patiently to ensconce herself in a corner of the window-sill, and wait till some person came to the house, who, on knocking at the door, found immediate attention. Many a day, no doubt, little Deb sat there on the window-sill and watched this proceeding, gazing at the  knocker, and wondering what it had to do with getting the door open.

knocker, and wondering what it had to do with getting the door open.

A month passed away, and little Deb grew from a kitten into a full-sized cat. Many a weary hour was passed in her corner. At length Deb arrived at the conclusion that if she could manage to make the knocker sound a rap-a-tap-tap on the door, the noise would summon the servant, and she would gain admittance as well as the guests who came to the house.

One day Deb had been shut out, when Mary, the maidservant, who was sitting industriously stitching away, heard a rap-a-tap at the front door, announcing the arrival, as she supposed, of a visitor. Putting down her work, she hurried to the door and lifted the latch; but no one was there except Deb, who at that moment leaped off the window-sill and entered the house. Mary looked along the road, up and down on either side, thinking that some person must have knocked and gone away; but no one was in sight.

The following day the same thing happened, but it occurred several times before any one suspected that Deb could possibly have lifted the knocker. At length Mary told her mistress what she suspected, and one of the family hid in the shrubbery to watch Deb’s proceedings. Deb was allowed to ran out in the garden, and the door was closed. After a time the little creature was seen to climb up on the window-sill, and then to rear herself on her hind-feet, in an oblique position at the full stretch of her body, when, steadying herself with one front paw, with the other she raised the knocker; and Mary, who was on the watch, instantly ran to the door and let her in.

Miss Deb’s knock now became as well-known to the servant as that of any other member of the family, and, no doubt to her great satisfaction, it usually met with prompt attention.

Could the celebrated cat of the renowned Marquis of Carrabas have done more, or better? Not only must Deb have exercised reason and reflection, as well as imitation, but a considerable amount of perseverance; for probably she made many vain attempts before she was rewarded with success.

Some Scotch ladies told me of a cat they had when young, brought by their grandfather from Archangel, which, under the same circumstances, used to reach up to the latch of the front door of a house in the country, and to rattle away on it till admitted. I have seen a cat which the same ladies now possess make a similar attempt.

Does it not occur to you that you may take a useful lesson from little Pussy, and when you have an object to gain, a task to perform, think over the matter, and exert yourself to the utmost till you have accomplished it?

The Cat and the Rabbit-trap.

An instance of the sagacity of a cat came under my own notice. I was living, a few years ago, in a country place in Dorsetshire, when one day a small tortoise-shell cat met my children on the road, and followed them home. They, of course, petted and stroked her, and showed their wish to make her their friend. She was one of the smallest, and yet the most active of full-grown cats I ever saw. From the first she gave evidence of being of a wild and predatory disposition, and made sad havoc among the rabbits, squirrels, and birds. I have several times seen her carry along a rabbit half as big as herself. Many would exclaim that for so nefarious a deed she ought to have been shot; but as she had tasted of my salt, taken refuge under my roof, besides being the pet of my children, I could not bring myself to order her destruction.

We had, about the time of her arrival, obtained a dog to act as a watchman over the premises. She and he were at first on fair terms—a sort of armed neutrality. In process of time, however, she became the mother of a litter of kittens. With the exception of one, they shared the fate of other kittens. When she discovered the loss of her hopeful family, she wandered about in a melancholy way, evidently searching for them, till, encountering Carlo, it seemed suddenly to strike her that he had been the cause of her loss. With back up, she approached, and flying at him with the greatest fury, attacked him till blood dropped from his nose, when, though ten times her size, he fairly turned tail and fled. Pussy and Carlo, after this, became friends; at least, they never interfered with each other.

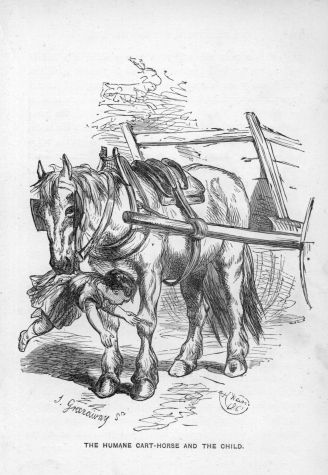

Pussy, however, to her cost, still continued her hunting expeditions. The rabbits had committed great depredations in the garden, and the gardener had procured two rabbit-traps. One had been set at a considerable distance from the house, and fixed securely in the ground. One morning the nurse heard a plaintive mewing at the window of the day-nursery on the ground-floor. She opened it, and in crawled poor Pussy, dragging the heavy iron rabbit-trap, in the teeth of which her fore-foot was caught. I was called in, and assisted to release her. Her paw swelled, and for some time she could not move out of the basket in which she was placed before the fire. Though suffering intense pain, she must have perceived that the only way to release herself was to dig up the trap, and then drag it, up many steep paths, to the room where her kindest friends—nurse and the children—were to be found.

Carlo had been caught before in the same trap, and he bit at it, and at everything around, and severely injured the gardener, who went to release him. Thus Pussy, under precisely the same circumstances, showed by far the greatest amount of sagacity and cool courage. She, however, not many weeks after her recovery, came in one day with her foot sadly lacerated, having again been caught in a trap; so, although she could reason, she did not appear to have learned wisdom from experience. This last misfortune, however, taught her prudence, as she was never again caught in a trap.

You will agree with me that Pussy was wise in going to her best friends for help when in distress; and foolish, having once suffered, again to run into the same danger.

You, my young reader, will be often entrapped, if you lack strength to resist temptation. Your kind friends at home will, I am sure, help you as far as they have the power; but, that they may do so, you must on all occasions trust them.

Affection exhibited by a Cat.

I was one day calling in Dorsetshire on a clever, kind old lady, who showed me a beautiful tabby cat, coiled up before the fire. “Seventeen years ago,” said she, “that cat’s mother had a litter. They were all ordered to be drowned with the exception of one. The servant brought me one. It was a tortoise-shell. ‘No,’ I said; ‘that will always be looking dirty. I will choose another.’ So I put my hand into the basket, and drew forth this tabby. The tabby has loved me ever since. When she came to have a family, she disappeared; but the rain did not, for it came pouring down through the ceiling: and it was discovered that Dame Tabby had made a lying-in hospital for herself in the thatched roof of the house. The damage she did cost several pounds; so we asked a friend who had a good cook, fond of cats, to take care of Tabby the next time she gave signs of having a family, as we knew she would be well fed. We sent her in a basket completely covered up; and she was shut into a room, where she soon exhibited a progeny of young mewlings. More than the usual number were allowed to survive, and it was thought that she would remain quietly where she was. Not so. On the first opportunity she made her escape, and down she came all the length of the village, and early in the morning I heard her mewing at my bed-room door to be let in. When I had stroked her back and spoken kindly to her, off she went to look after her nurslings. From that day, every morning she came regularly to see me, and would not go away till she had been spoken to and caressed. Having satisfied herself that I was alive and well, back she would go. She never failed to pay me that one visit in the morning, and never came twice in the day, till she had weaned her kittens; and that very day she came back, and nothing would induce her to go away again. I had not the heart to force her back. From that day to this she has always slept at the door of my room.”

Surely you will not be less grateful to those who brought you up than was my old friend’s cat to her. Acts, not mere words, show the sincerity of our feelings. Consider how you are acting towards them each hour and day of your life. Are you doing your best to act well, whether at home, at school, or at play?

The Cat and her young Mistresses.

My friend Mrs F— gave me a very touching anecdote.

A lady she knew, residing in Essex, once had two young daughters. They had a pet cat which they had reared from a kitten, and which was their constant companion. The sisters, however, were both seized with scarlet fever, and died. The cat seemed perfectly to understand what had taken place, and, refusing to leave the room, seated herself on the bed where they lay, in most evident sorrow. When the bodies of the young girls were placed in their small coffins, she continued to move backwards and forwards from one to the other, uttering low and melancholy sounds. Nothing could induce her all the time to take food, and soon after the interment of her fond playmates she lay down and passed away from life.

This account, given by the mother of the children, makes me quite ready to believe in the truth of similar anecdotes.

Tender affection is like a beautiful flower: it needs cultivation. As cold winds and pelting showers injure the fair blossoms, so passionate temper, sullen behaviour, or misconduct, will destroy the love which should exist between brothers and sisters, and those whose lot is cast together. Cherish affectionate feelings in your hearts. Be kind and gentle to all around, and your friends will love you more even than the cat I have told you about loved her mistresses.

The Cat which died of Grief.

A lady in France possessed a cat which exhibited great affection for her. She accompanied her everywhere, and when she sat down always lay at her feet. From no other hands than those of her mistress would she take food, nor would she allow any one else to fondle her.

The lady kept a number of tame birds; but the cat, though she would willingly have caught and eaten strange birds, never injured one of them.

At last the lady fell ill, when nothing could induce the cat to leave her chamber; and on her death, the attendants had to carry away the poor animal by force. The next morning, however, she was found in the room of death,  creeping slowly about, and mewing piteously. After the funeral, the faithful cat made her escape from the house, and was at length discovered stretched out lifeless above the grave of her mistress, having evidently died of a broken heart.

creeping slowly about, and mewing piteously. After the funeral, the faithful cat made her escape from the house, and was at length discovered stretched out lifeless above the grave of her mistress, having evidently died of a broken heart.

The instances I have given—and I might give many more—prove the strong affection of which cats are capable, and show that they are well deserving of kind treatment. When we see them catch birds and mice, we must remember that it is their nature to do so, as in their wild state they have no other means of obtaining food.

The Cat and the Canary.

Animals of a very different character often form curious friendships. What do you think of the cat which of her own accord became the protector of a pet canary, instead of eating it up?

The cat and the bird belonged to the mother-in-law of Mrs Lee, who has given us many delightful anecdotes of animals. The canary was allowed to fly about the room when the cat was shut out; but one day their mistress, lifting her head from her work, saw that the cat had by some means got in; and, to her amazement, there was the canary perched fearlessly on the back of Pussy, who seemed highly pleased with the confidence placed in her. By the silent language with which animals communicate their ideas to each other, she had been able to make the canary understand that she would not hurt it.

After this, the two were allowed to be constantly together, to their mutual satisfaction. One morning, however, as they were in the bed-room of their mistress, what was her dismay to see the trustworthy cat, as she had supposed her, after uttering a feline growl, seize the canary in her mouth, and leap with her into the bed. There she stood, her tail stiffened out, her hair bristling, and her eyes glaring fiercely. The fate of the poor canary appeared sealed; but just then the lady caught sight of a strange cat creeping cautiously through the open doorway. The intruder was quickly driven away, when faithful Puss deposited her feathered friend on the bed, in no way injured—she having thus seized it to save it from the fangs of the stranger.

Confidence begets confidence; but be very sure that the person on whom you bestow yours is worthy of it. If not, you will not be as fortunate as the canary was with its feline friend.

Your truest confidants, in most cases, are your own parents.

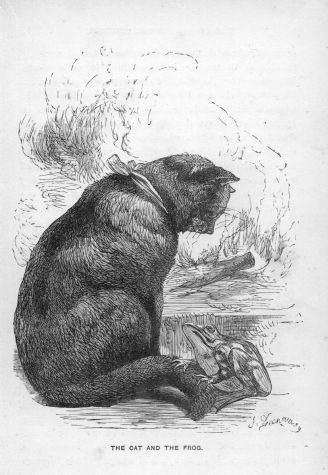

The Cat and the Frog.

I have an instance of a still stranger friendship to mention. The servants of a country-house—and I am sure that they were kind people—had enticed a frog from its hole by giving it food. As winter drew on, Froggy every evening made its way to the kitchen hearth before a blazing fire, which it found much more comfortable than its own dark abode out in the yard. Another occupant of the hearth was a favourite old cat, which at first, I daresay, looked down on the odd little creature with some contempt, but was too well bred to disturb an invited guest. At length, however, the two came to a mutual understanding; the kind heart of Pussy warming towards poor chilly little Froggy, whom she now invited to come and nestle under her cozy fur. From that time forward, as soon as Froggy came out of its hole, it hopped fearlessly towards the old cat, who constituted herself its protector, and would allow no one to disturb it.

Imitate the kind cat, and be kind to the most humble, however odd their looks. Sometimes at school and elsewhere you may find some friendless little fellow. Prove his protector. Be not less benevolent than a cat.

The Cat and her dead Kitten.

That cats expect those to whom they are attached to sympathise with them in their sorrow, is shown by an affecting story told by Dr Good, the author of the “Book of Nature.”

He had a cat which used to sit at his elbow hour after hour while he was writing, watching his hand moving over the paper. At length Pussy had a kitten to take care of, when she became less constant in her attendance on her master. One morning, however, she entered the room, and leaping on the table, began to rub her furry side against his hand and pen, to attract his attention. He, supposing that she wished to be let out, opened the door; but instead  of running forward, she turned round and looked earnestly at him, as though she had something to communicate. Being very busy, he shut the door upon her, and resumed his writing. In less than an hour, the door having been opened again, he felt her rubbing against his feet; when, on looking down, he saw that she had placed close to them the dead body of her kitten, which had been accidentally killed, and which she had brought evidently that her kind master might mourn with her at her loss. She seemed satisfied when she saw him with the dead kitten in his hand, making inquiries as to how it had been killed; and when it was buried, believing that her master shared her sorrow, she gradually took comfort, and resumed her station at his side. Observe how, in her sorrow, Pussy went to her best friend for sympathy. Your best earthly friends are your parents. Do not hesitate to tell them your griefs; and you will realise that it is their joy and comfort to sympathise with you in all your troubles, little or great, and to try to relieve them.

of running forward, she turned round and looked earnestly at him, as though she had something to communicate. Being very busy, he shut the door upon her, and resumed his writing. In less than an hour, the door having been opened again, he felt her rubbing against his feet; when, on looking down, he saw that she had placed close to them the dead body of her kitten, which had been accidentally killed, and which she had brought evidently that her kind master might mourn with her at her loss. She seemed satisfied when she saw him with the dead kitten in his hand, making inquiries as to how it had been killed; and when it was buried, believing that her master shared her sorrow, she gradually took comfort, and resumed her station at his side. Observe how, in her sorrow, Pussy went to her best friend for sympathy. Your best earthly friends are your parents. Do not hesitate to tell them your griefs; and you will realise that it is their joy and comfort to sympathise with you in all your troubles, little or great, and to try to relieve them.

The Kitten and the Chickens.

Kittens, especially if deprived of their natural protectors, seem to long for the friendship of other beings, and will often roam about till they find a person in whom they think they may confide. Sometimes they make a curious choice. A kitten born on the roof of an out-house was by an accident deprived of its mother and brethren. It evaded all attempts to catch it, though food was put within its reach. Just below where it lived, a brood of chickens were constantly running about; and at length, growing weary of solitude, it thought that it would like to have such lively little playmates. So down it scrambled, and timidly crept towards them. Finding that they were not likely to do it harm, it lay down among them. The chickens seemed to know that it was too young to hurt them.

It now followed them wherever they moved to pick up their food. In a short time a perfect understanding was established between the kitten and the fowls, who appeared especially proud of their new friend. The kitten, discovering this, assumed the post of leader, and used to conduct them about the grounds, amusing itself at their expense. Sometimes it would catch hold of their feet, as if going to bite them, when they would peck at it in return. At others it would hide behind a bush, and then springing out into their midst, purr and rub itself against their sides. One pullet was its especial favourite; it accompanied her every day to her nest under the boards of an out-house, and would then lie down outside, as if to watch over her. When she returned to the other fowls, it would follow, setting up its tail, and purring at her.

When other chickens were born, it transferred its interest to them, taking each fresh brood under its protection—the parent hen appearing in no way alarmed at having so unusual a nurse for her young ones.

Be as sensible as the little kitten. Don’t stand on your dignity, or keep upon the roof, in a fit of the sulks; but jump down, and shake such feelings off with a game of good-natured play.

The Cat and the Pigeon.

Similar affection for one of the feathered race was shown by a cat which was rearing several kittens.

In another part of the loft a pigeon had built her nest; but her eggs and young having been frequently destroyed by rats, it seemed to occur to her that she should be in safer quarters near the cat. Pussy, pleased with the confidence placed in her, invited the pigeon to remain near her, and a strong friendship was established between the two. They fed out of the same dish; and when Pussy was absent, the pigeon, in return for the protection afforded her against the rats, constituted herself the defender of the kittens—and on any person approaching nearer than she liked, she would fly out and attack them with beak and wings, in the hope of driving them away from her young charges. Frequently, too, after this, when neither the kittens nor her own brood required her care, and the cat went out about the garden or fields, the pigeon might be seen fluttering close by her, for the sake of her society.

Help and protect one another in all right things, as did the cat and the pigeon, whatever your respective ages or stations in life. The big boy or girl may be able to assist and protect the little ones, who may render many a service in return.

The Cat and the Leveret.

Cats exhibit their affectionate nature in a variety of ways. If deprived of their kittens, they have a yearning for the care of some other young creatures, which they will gratify when possible.

A cat had been cruelly deprived of all her kittens. She was seen going about mewing disconsolately for her young ones. Her owner received about the same time a leveret, which he hoped to tame by feeding it with a spoon. One morning, however, the leveret was missing, and as it could nowhere be discovered, it was supposed to have been carried off and killed by some strange cat or dog. A fortnight had elapsed, when, as the gentleman was seated in his garden, in the dusk of the evening, he observed his cat, with tail erect, trotting towards him, purring and calling in the way cats do to their kittens. Behind her came, gambolling merrily, and with perfect confidence, a little leveret,—the very one, it was now seen, which had disappeared. Pussy, deprived of her kittens, had carried it off and brought it up instead, bestowing on it the affection of her maternal heart.

It is your blessed privilege to have hearts to feel the greatest enjoyment in tender love for others. See that you keep that love in constant exercise, or, like others of our best gifts, it may grow dull by disuse or abuse. The time may come when, deprived of your parents or brothers and sisters, you will bitterly mourn the sorrow you have caused by your evil temper or neglect.

The Cat and the Puppies.

I have a longer story than the last to tell, of a cat which undertook the nursing of some puppies while she already had some kittens of her own. It happened that her mistress possessed a valuable little black spaniel, which had a litter of five puppies. As these were too many for the spaniel to bring up, and the mistress was anxious to have them all preserved, it was proposed that they should be brought up by hand. The cook, to whom the proposal was made, suggested that this would be a difficult undertaking; but as the cat had lately kittened, some of the puppies might be given to her to bring up. Two of the kittens were accordingly taken away, and the same number of puppies substituted. What Puss thought of the matter has not transpired, or whether even she discovered the trick that had been played her; but be that as it may, she immediately began to bestow the same care on the little changelings that she had done on her own offspring, and in a fortnight they were as forward and playful as kittens would have been, gambolling about, and barking lustily—while the three puppies nursed by their own mother were whining and rolling about in the most helpless fashion.

Puss had proved a better nurse than the little spaniel. She gave them her tail to play with, and kept them always in motion and amused, so that they ate meat, and were strong enough to be removed and to take care of themselves, long before their brothers and sisters.

On their being taken away from her, their poor nurse showed her sorrow, and went prowling about the house, looking for them in every direction. At length she caught sight of the spaniel and the three remaining puppies. Instantly up went her back; her bristles stood erect, and her eyes glared fiercely at the little dog, which she supposed had carried off her young charges.

“Ho, ho! you vile thief, who have ventured to rob me of my young ones; I have found you at last!” she exclaimed—at least, she thought as much, if she did not say it. The spaniel barked defiance, answering—“They are my own puppies; you know they are as unlike as possible to your little, tiresome, frisky mewlings.”

“I tell you I know them to be mine,” cried Puss, spitting and hissing; “I mean to recover my own.” And before the spaniel knew what was going to happen, Puss sprang forward, seized one of the puppies, and carried it off to her own bed in another part of the premises.

Not content with this success, as soon as she had safely deposited the puppy in her home, she returned to the abode of the spaniel. This time she simply dashed forward, as if she had made up her mind what to do, knocked over the spaniel with her paw, seized another puppy in her mouth, and carrying it off, placed it alongside the first she had captured. She was now content. Two puppies she had lost, two she had obtained. Whether or not she thought them the same which had been taken from her, it is difficult to say. At all events, she nursed the two latter with the same tender care as the first.

Copy playful Pussy, when you have charge of little children. They enjoy games of romps as much as young  puppies do, and will be far happier, and thrive better, than when compelled to loll about by themselves, while you sit at your book or work in silent dignity and indifference to their requirements, however fond you may be of them—as was, I daresay, the mother spaniel of her pups.

puppies do, and will be far happier, and thrive better, than when compelled to loll about by themselves, while you sit at your book or work in silent dignity and indifference to their requirements, however fond you may be of them—as was, I daresay, the mother spaniel of her pups.

The Cat and the Burglars.

No stronger evidence of the sagacity of the cat is to be found than an instance narrated to me by my friend, Mrs F—, and for which I can vouch.

A lady, Miss P—, who was a governess in her family, had previously held the same position in that of Lord —, in Ireland. While there a cat became very strongly attached to her. Though allowed to enter the school-room and dining-room, where she was fed and petted, the animal never came into the lady’s bed-room; nor was she, indeed, accustomed to go into that part of the house at any time.

One night, however, after retiring to rest, Miss P— was disturbed by the gentle but incessant mewing of the cat at her bed-room door. At first she was not inclined to pay attention to the cat’s behaviour, but the perseverance of the animal, and a peculiarity in the tones of her voice, at length induced her to open the door. The cat, on this, bounded forward, and circled round her rapidly, looking up in her face, mewing expressively. Miss P—, thinking that the cat had only taken a fancy to pay her a visit, refastened the door, intending to let her remain in the room; but this did not appear to please Pussy at all. She sprang back to the door, mewing more loudly than before; then she came again to the lady, and then went to the door, as if asking her to follow.

“What is it you want?” exclaimed Miss P—. “Well, go away, if you do not wish to stay!” and she opened the door; but the cat, instead of going, recommenced running to and fro between the door and her friend, continuing to mew as she looked up into her face.

Miss P—’s attention was now attracted by a peculiar noise, as if proceeding from the outside of one of the windows on the ground-floor. A few moments more convinced her that some persons were attempting to force an entrance.

Instantly throwing a shawl around her, she hurried along the passage, the cat gliding by her side, purring now in evident contentment, to Lord —’s bed-room door, where her knock was quickly answered, and an explanation given.

The household was soon aroused; bells were rung, lights flitted about, servants hurried here and there; and persons watching from the windows distinctly saw several men making off with all speed, and scrambling over an adjacent wall.

It was undoubtedly owing to the sagacity of the cat that the mansion was preserved from midnight robbery, and the inmates probably from some fearful outrage. She must have reasoned that the intruders had no business there; whilst her reason and affection combined induced her to warn her best friend of the threatened danger. She may have feared, also, that any one else in the house would have driven her heedlessly away.

My dear reader, may we not believe that this reasoning power was given to the dumb animal for the protection of the family against evil-doers? I might give you many instances of beneficent purposes being carried out by equally simple and apparently humble agencies.

Let us, then, learn always to treat dumb animals with kindness and consideration, since they are so often given to us as companions for our benefit. Like the cat, you may by vigilance be of essential service to others more powerful than yourself. For the same reason, never despise the good-will or warnings of even the most humble.

The Cat which rang the Bell.

I have heard of another cat, who, had she lived in Lord —’s house when attacked by robbers, might very speedily have aroused the family.

This cat, however, lived in a nunnery in France. She had observed that when a certain bell was rung, all the inmates assembled for their meals, when she also received her food.

One day she was shut up in a room by herself when she heard the bell ring. In vain she attempted to get out; she could not open the door, the window was too high to reach. At length, after some hours’ imprisonment, the door was opened. Off she hurried to the place where she expected to find her dinner, but none was there. She was very hungry, and hunger is said to sharpen the wits. She knew where the rope hung which pulled the bell in the  belfry. “Now, when that bell rings I generally get my supper,” she thought, as she ran towards the rope. It hung down temptingly within her reach—a good thick rope. She sprang upon it. It gave a pleasant tinkle. She jerked harder and harder, and the bell rang louder and louder. “Now I shall get my supper, though I have lost my dinner,” she thought as she pulled away.

belfry. “Now, when that bell rings I generally get my supper,” she thought, as she ran towards the rope. It hung down temptingly within her reach—a good thick rope. She sprang upon it. It gave a pleasant tinkle. She jerked harder and harder, and the bell rang louder and louder. “Now I shall get my supper, though I have lost my dinner,” she thought as she pulled away.

The nuns hearing the bell ring at so unusual an hour, came hurrying into the belfry, wondering what was the matter, when what was their surprise to see the cat turned bell-ringer! They puzzled their heads for some time, till the lay sister who generally gave the cat her meals recollected that she had not been present at dinner-time; and thus the mystery was solved, and Pussy rewarded for her exertions by having her supper brought to her without delay.

Instead of sitting down and crying when in a difficulty, think, like sensible Pussy, of the best way to get out of it. In lieu of wringing your hands, ring the bell.

The affectionate Cat that could measure time.

The last story reminds me of Mrs F—’s account of the cat and the knocker. That same intelligent little cat was also one of the most affectionate of her race. Her young mistress used to go to school for a few hours daily in the neighbouring town. Pussy would every morning sally forth with her, and bound along beside her pony as far as the gate, then going quietly back to the house. Regularly, however, at the time the little girl was expected to return, the faithful pet might be seen watching about the door; and if Missy were delayed longer than usual, would extend her walk to the gate, there awaiting her approach, and evincing her delight by joyful gambols as soon as she descried her coming along the road. Pussy would then hurry back to the house-door, that she might give notice of her young mistress’s return, and the moment she alighted would welcome her with happy purrings and caresses.

Endeavour to be as regular in all your ways as my friend’s cat. Never keep your friends waiting for you, but rather wait for them. Show your affection and wish to please in this as in other ways. Thank Pussy for the excellent example she has set you.

The Cat and the Prisoner.

While speaking of the affection of cats, I must not forget to mention a notable example of it shown by the favourite cat of a young nobleman in the days of Queen Elizabeth.

For some political offence he had been shut up in prison, and had long pined in solitude, when he was startled by hearing a slight noise in the chimney. On looking up, great was his surprise and delight to see his favourite cat bound over the hearth towards him, purring joyfully at the meeting. She had probably been shut up for some time before she had made her escape, and then she must have sought her master, traversing miles of steep and slippery roofs, along dangerous parapets, and through forests of chimney-stacks, urged on by the strength of her attachment, and guided by a mysterious instinct, till she discovered the funnel which led into his prison chamber.

Certainly it was not by chance she made the discovery, nor was it exactly reason that conducted her to the spot. By whatever means she found it, we must regard the affectionate little creature as the very “Blondel of cats.”

Never spare trouble or exertion to serve a friend, or to please those you are bound to please. Remember the prisoner’s cat.

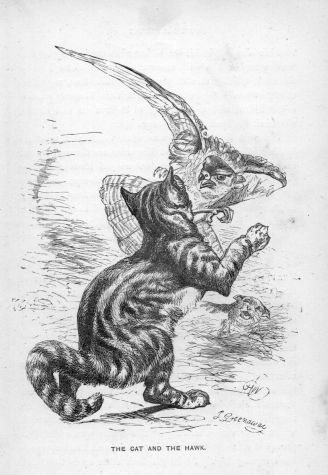

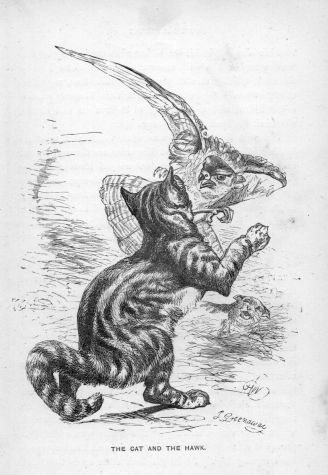

The Cat and the Hawk.

Cats often show great courage, especially in defence of their young.

A cat had led her kittens out into the sunshine, and while they were frisking around her they were espied by a hawk soaring overhead. Down pounced the bird of prey and seized one in his talons. Encumbered by the weight of the fat little creature, he was unable to rise again before the mother cat had discovered what had occurred. With a bound she fiercely attacked the marauder, and compelled him to drop her kitten in order to defend himself. A regular combat now commenced, the hawk fighting with beak and talons, and rising occasionally on his wings. It seemed likely that he would thus gain the victory; still more when he struck his sharp beak into one of Pussy’s eyes, while he tore her ears into shreds with his talons. At length, however, she managed what had been from the  first her aim—to break one of her adversary’s wings. She now sprang on him with renewed fury, and seizing him by the neck, quickly tore off his head. This done, regardless of her own sufferings, she began to lick the bleeding wounds of her kitten, and then, calling to its brothers and sisters, she carried it back to their secure home.

first her aim—to break one of her adversary’s wings. She now sprang on him with renewed fury, and seizing him by the neck, quickly tore off his head. This done, regardless of her own sufferings, she began to lick the bleeding wounds of her kitten, and then, calling to its brothers and sisters, she carried it back to their secure home.

You will find many hawks with which you must do battle. The fiercest and most dangerous are those you must encounter every day. Huge dark-winged birds of prey—passionate temper, hatred, discontent, jealousy;—an ugly list, I will not go on with it. Fight against them as bravely as Pussy fought with the hawk which tried to carry off her kitten.

The benevolent Cat.

That we must attribute to cats the estimable virtue of benevolence, Mrs F— gives me two anecdotes to prove.

A lady in the south of Ireland having lost a pet cat, and searched for it in vain, after four days was delighted to hear that it had returned. Hastening to welcome the truant with a wassail-bowl of warm milk in the kitchen, she observed another cat skulking with the timidity of an uninvited guest in an obscure corner. The pet cat received the caresses of its mistress with its usual pleasure, but, though it circled round the bowl of milk with grateful purrings, it declined to drink, going up to the stranger instead, whom, with varied mewings, “like man’s own speech,” it prevailed on to quit the shadowy background and approach the tempting food. At length both came up to the bowl, when the thirsty stranger feasted to its full satisfaction, while the cat of the house stood by in evident satisfaction watching its guest; and not until it would take no more could the host be persuaded to wet its whiskers in the tempting beverage.

Ever think of others before yourself. Attend first to their wants. Do not be outdone in true courtesy by a cat.

The Cat and her many Guests.

Mrs F— vouches for the following account, showing the hospitable disposition of cats. It was given to her by a clergyman, who had it direct from a friend.

A gentleman in Australia had a pet cat to which he daily gave a plate of viands with his own hands. The allowance was liberal, and there was always a remainder; but after some time the gentleman perceived that another cat came to share the repast. Finding that this occurred for several consecutive days, he increased the allowance. It was then found to be too much for two; there was again a residue for several days, when a third cat was brought in to share the feast. Amused at this proceeding, the gentleman now began to experiment, and again increased the daily dole of food. A fourth guest now appeared; and he continued adding gradually to the allowance of viands, and found that the number of feline guests also progressively increased, until about thirty were assembled; after which no further additions took place, so that he concluded that all those who lived within visiting distance were included: indeed, the wonder was that so many could assemble, as the district he lived in was far from populous.

The stranger cats always decorously departed after dinner was over, leaving their hospitable entertainer, no doubt, with such grateful demonstrations as might be dictated by the feline code of etiquette.

Ask yourselves if you are always as anxious as was the Australian cat to invite your companions to enjoy with you the good things you have given you by kind friends. Ah! what an important lesson we may learn from this anecdote: always to think of others before ourselves. When young friends visit you, do you try your utmost to entertain them, thinking of their comfort before your own? Such is the lesson taught us by this cat, which gathered others of her kind to share the bounties provided by her kind master.

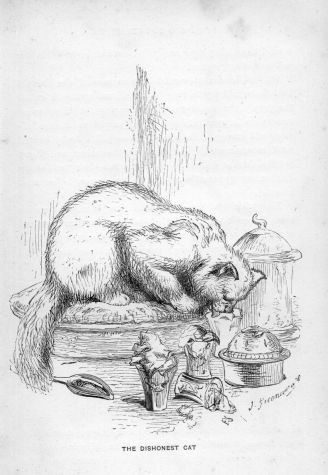

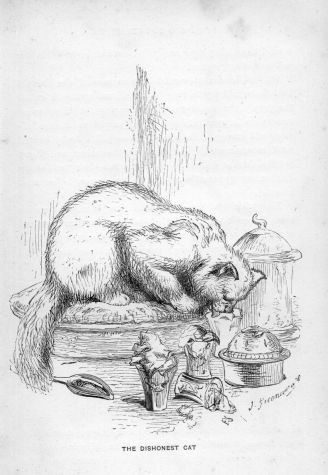

The Dishonest Cat.

I am sorry to say that cats are not always so amiable as those I have described, but will occasionally play all sorts of tricks, like some dishonest boys and girls, to obtain what they want.

An Angora cat, which lived in a large establishment in France, had discovered that when a certain bell rang the cook always left the kitchen. Numerous niceties were scattered about, some on the tables and dressers, others before the fire. Pussy crept towards them, and tasted them; they exactly suited her palate. When she heard the cook’s step returning, off she ran to a corner and  pretended to be sleeping soundly. How she longed that the bell would ring again!

pretended to be sleeping soundly. How she longed that the bell would ring again!

At last, like another cat I have mentioned, she thought that she would try to ring it herself, and get cook out of the way; she could resist her longing for those sweet creams no longer. Off she crept, jumped up at the bell-rope, and succeeded in sounding the bell. Away hurried cook to answer it. The coast was now clear, and Pussy revelled in the delicacies left unguarded—being out of the kitchen, or apparently asleep in her corner, before cook returned.

This trick continued to answer Pussy’s object for some time, the cook wondering what had become of her tarts and creams, till a watch was wisely set to discover the thief, when the dishonest though sagacious cat was seen to pull the bell, and then, when cook went out, to steal into the kitchen and feast at her leisure.

There is a proverb—which pray condemn as a bad one, because the motive offered is wrong—that “honesty is the best policy.” Rather say, “Be honest because it is right.” Pussy, with her manoeuvres to steal the creams, thought herself very clever, but she was found out.

Pussy and the Cream-jug.

I must now tell you of another cat which was a sad thief, and showed a considerable amount of sagacity in obtaining what she wanted. One day she found a cream-jug on the  breakfast-table, full of cream. It was tall, and had a narrow mouth. She longed for the nice rich contents, but could not reach the cream even with her tongue; if she upset the jug, her theft would be discovered. At last she thought to herself, “I may put in my paw, though I cannot get in my head, and some of that nice stuff will stick to it.”

breakfast-table, full of cream. It was tall, and had a narrow mouth. She longed for the nice rich contents, but could not reach the cream even with her tongue; if she upset the jug, her theft would be discovered. At last she thought to herself, “I may put in my paw, though I cannot get in my head, and some of that nice stuff will stick to it.”

She made the experiment, and found it answer. Licking her paw as often as she drew it out, she soon emptied the jug, so that when the family came down they had no cream for breakfast. A few drops on the table-cloth, however, showed how it had been stolen—Pussy, like human beings who commit dishonest actions, not being quite so clever as she probably thought herself.

The revengeful Cat.

Cats often show that they possess some of the vices as well as some of the virtues of human beings. The tom-cat is frequently fierce, treacherous, and vindictive, and at no time can his humour be crossed with impunity. Mrs F— mentions several instances of this.

A person she knew in the south of Ireland had severely chastised his cat for some misdemeanour, when the creature immediately ran off and could not be found. Some days afterwards, as this person was going from home, what should he see in the centre of a narrow path between walls but his cat, with its back up, its eyeballs glaring, and a wicked expression in its countenance. Expecting to frighten off the creature, he slashed at it with his handkerchief, when it sprang at him with a fierce hiss, and, seizing his hand in its mouth, held on so tightly that he was unable to beat it off. He hastened home, nearly fainting with the agony he endured, and not till the creature’s body was cut from the head could the mangled hand be extricated.

An Irish gentleman had an only son, quite a little boy, who, being without playmates, was allowed to have a number of cats sleeping in his room. One day the boy beat the father of the family for some offence, and when he was asleep at night the revengeful beast seized him by the throat, and might have killed him had not instant help been at hand. The cat sprang from the window and was no more seen.

If you are always gentle and kind, you will never arouse anger or revenge. It may be aroused in the breast of the most harmless-looking creatures and the most contemptible. Your motive, however, for acting gently and lovingly should be, not fear of the consequences of a contrary behaviour, but that the former is right.

Chapter Two.

Dogs.

We now come to the noble Dog, indued by the Creator with qualities which especially fit him to be the companion of man. Such he is in all parts of the world; and although wild dogs exist, they appear, like savage human beings, to have retrograded from a state of civilisation. The mongrels and curs, too, have evidently deteriorated, and lost the characteristic traits of their nobler ancestors.

What staunch fidelity, what affection, what courage, what devotion and generosity does the dog exhibit! Judged by the anecdotes I am about to narrate of him—a few only of the numberless instances recorded of his wonderful powers of mind—he must, I think, be considered the most sagacious of all animals, the mighty elephant not excepted.

The Dog Rosswell.

I will begin with some anecdotes which I am myself able to authenticate.

Foremost must stand the noble Rosswell, who belonged to some connections of mine. He was of great size—a giant of the canine race—of a brown and white colour, one of his parents having seen the light in the frozen regions of Greenland, among the Esquimaux.

Rosswell, though a great favourite, being too large to be fed in the house, had his breakfast, consisting of porridge, in a large wooden bowl with a handle, sent out to him every morning, and placed close to a circular shrubbery before the house. Directly it arrived, he would cautiously put his nose to the bowl, and if, as was generally the case, the contents were too hot for his taste, he would take it up by the handle and walk with it round the shrubbery at a dignified pace, putting it down again at the same spot. He would then try the porridge once more, and if it were still too hot he would again take up the bowl and walk round and round as before, till he was satisfied that the superabundant caloric had been dissipated, when, putting it down, he would leisurely partake of his meal.

Everything he did was in the same methodical, civilised fashion. One of the ladies of the family had dropped a valuable bracelet during a walk. In the evening Rosswell entered the house and proceeded straight up to her with his mouth firmly closed. “What have you got there?” she asked, when he at once opened his huge mouth and revealed the missing bracelet.

The same lady was fond of birds, and had several young ones brought to her from time to time to tame. Rosswell must have observed this. One day he appeared again with his mouth closed, and came up to her. On opening his jaws, which he allowed her to do, what was her surprise to see within them a little bird, perfectly unhurt! After this he very frequently brought her birds in his mouth, which he had caught without in any way injuring them.

He had another strange fancy. It was to catch hedgehogs; but, instead of killing them, he invariably brought them into the house and placed them before the kitchen fire—supposing, apparently, that they enjoyed its warmth.

With two of the ladies of the family he was a great favourite, and used to romp with them to his heart’s content. The youngest, however, being of a timid disposition, could never get over a certain amount of terror with which his first appearance had inspired her.

At length Rosswell disappeared. Although inquiries were everywhere made for him he could not be found. It was suspected that he had been stolen, with the connivance of one of the domestics, who owed him a grudge. Weeks passed away, and all hope of recovering Rosswell had been abandoned, when one day he rushed into the house, looking lean and gaunt, with a broken piece of rope hanging to his neck, showing that he had been kept “in durance vile,” and had only just broken his bonds. The two elder sisters he greeted with the most exuberant marks of affection, leaping up and trying to lick their faces; but directly the youngest appeared he slowly crept forward, lay down at her feet, wagging his tail, and glancing up at her countenance with an unmistakably gentle look.

Rosswell, not without provocation, had taken a dislike to a little dog belonging to Captain —; and at last, having been annoyed beyond endurance, he gave the small cur a bite which sent it yelping away. Captain — was passing at the time, and, angry at the treatment his dog had received, declared that he would shoot Rosswell if it ever happened again. Knowing that Captain — would certainly fulfil his threat, the elder lady, who was of determined character, and instigated by regard for Rosswell, called the dog to her, and began belabouring him with a stout stick, pronouncing the name of the little dog all the time. Rosswell received the castigation with the utmost humility; and from that day forward avoided the little dog, never retaliating when annoyed, and hanging down his head when its name was mentioned.

Rosswell had a remarkable liking for sugar-plums, and would at all times prefer a handful to a piece of meat. If, however, a pile of them were placed between his paws, and he was told that they were for baby, he would not touch them, but watch with wagging tail while the little fellow picked them up. He might probably have objected had any one else attempted to take them away.

Gallant Rosswell!—he fell a victim at length to the wicked hatred of his old enemy the cook, who mixed poison with his food, which destroyed his life.

Rosswell’s mistresses mourned for him, as I daresay you will; but they did not seek to punish the wicked woman as she deserved.

What a noble fellow he was, how submissive under castigation, how gentle when he saw that his boisterous behaviour frightened his youngest mistress, how obedient to command, how strict in the performance of his duty! And what self-restraint did he exercise! Think of him with baby’s sugar-plums between his paws—not one would he touch.

My reader, let me ask you one question: Are you as firm in resisting temptation as was gallant Rosswell? He acted rightly through instinct; but you have the power to discern between good and evil, aided by the counsels of your kind friends. Do not shame the teaching of your parents by acting in any manner unworthy of yourself.

Tyrol, the Dog which rang the Bell.

I have told you of several cats which rang bells. Another connection of mine, living in the Highlands, had a dog called Tyrol. He had been taught to do all sorts of things. Among others, to fetch his master’s slippers at bed-time; and when told that fresh peat was required for the fire, away he would go to the peat-basket and bring piece after piece, till a sufficient quantity had been piled up.

He had also learned to pull the bell-rope to summon the servant. This he could easily accomplish at his own home, where the rope was sufficiently long for him to reach; but on one occasion he accompanied his master on a visit to a friend’s house, where he was desired to exhibit his various accomplishments. When told to ring the bell, he made several attempts in vain. The end of the rope was too high up for him to reach. At length, what was the surprise of all present to see him seize a chair by the leg, and pull it up to the wall, when, jumping up, he gave the rope a hearty tug, evidently very much to his own satisfaction.

You will generally find that, difficult as a task may seem, if you seek for the right means you may accomplish it. Drag the chair up to the bell-rope which you cannot otherwise reach.

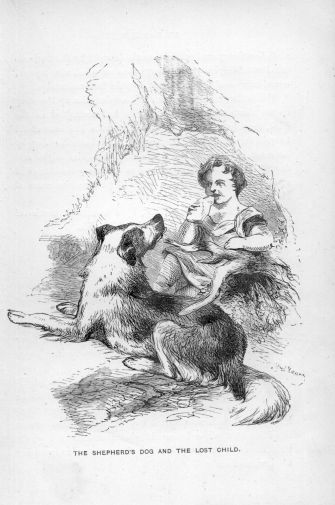

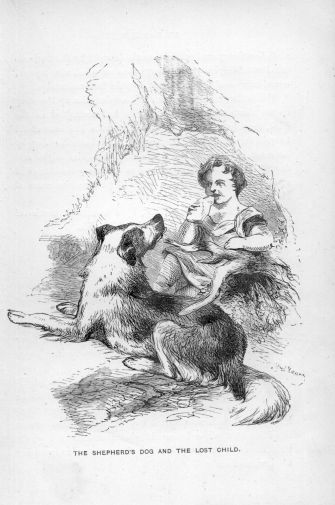

The Shepherd’s Dog and the lost Child.

I am sorry that I do not know the name of a certain shepherd’s dog, but which deserves to be recorded in letters of gold.

His master, who had charge of a flock which fed among the Grampian Hills, set out from home one day accompanied by his little boy, scarcely more than four years old. The children of Scottish shepherds begin learning their future duties at an early age. The day, bright at first, passed on, when a thick mist began to rise, shrouding the surrounding country. The shepherd, seeing this, hurried onward to collect his scattered flock, calling his dog to his assistance, and leaving his little boy at a spot where he believed that he should easily find him again. The fog grew thicker and thicker; and so far had the flock rambled, that some time passed before they could be collected together.

On his return to look for his child, the darkness had increased so much that he could not discover him. The anxious father wandered on, calling on his child—but no answer came; his dog, too, had disappeared. He had himself lost his way. At length the moon rose, when he discovered that he was not far from his own cottage. He hastened towards it, hoping that the child had reached it before him; but the little boy had not appeared, nor had the dog been seen. The agony of the parents can be better imagined than described. No torches were to be procured, and the shepherd had to wait till daylight ere he could set out with a companion or two to assist him in his search. All day he searched in vain. On his return, sick at heart, at nightfall, he heard that his dog had appeared during the day, received his accustomed meal of a bannock, and then scampered off at full speed across the moor, being out of sight before any one could follow him.

All night long the father waited, expecting the dog to return; but the animal not appearing, he again, as soon as it was daylight, set off on his search. During his absence, the dog hurried up to the cottage, as on the previous day, and went off again immediately he had received his bannock.

At last, after this had occurred on two more successive days, the shepherd resolved to remain at home till his dog should appear, and then to follow him.

The sagacious animal appearing as before, at once understood his master’s purpose, and instead of scampering off at full speed, kept in sight as he led the way across the moor. It was then seen that he held in his mouth the larger portion of the cake which had been given him. The dog conducted the shepherd to a cataract which fell roaring and foaming amid rocks into a ravine far down below. Descending an almost perpendicular cliff, the dog entered a cavern, close in front of which the seething torrent passed. The shepherd with great difficulty made his way to it, when, as he reached the entrance, he saw his child, unhurt,  seated on the ground eating the cake brought by the dog, who stood watching his young charge thus occupied, with a proud consciousness of the important duty he had undertaken.

seated on the ground eating the cake brought by the dog, who stood watching his young charge thus occupied, with a proud consciousness of the important duty he had undertaken.

The father, embracing his child, carried him up the steep ascent, down which it appeared he had scrambled in the dark, happily reaching the cave. This he had been afraid to quit on account of the torrent; and here the dog by his scent had traced him, remaining with him night and day, till, conscious that food was as necessary for the child as for himself, he had gone home to procure him some of his own allowance.

Thus the faithful animal had, by a wonderful exercise of his reasoning power, preserved the child’s life.

My Dog Alp.

A dear friend gave me, many years ago, a rough, white terrier puppy, which I called Alp. I fed him with my own hand from the first, and he consequently evinced the warmest attachment to me. No animal could be more obedient; and he seemed to watch my every look to ascertain what I wished him to do.

The expression of his countenance showed his intelligence; and whenever I talked to him he seemed to be making the most strenuous efforts to reply, twisting about his lips in a fashion which often made me burst into a fit of laughter, when he would give a curious bark of delight, as much as to say,—“Ay, I can utter as meaning a sound as that.”

I felt very sure that no burglar would venture into the house while he was on the watch.

I never beat him in his life; but once I pretended to do so, with a hollow reed which happened to be in the room, on his persisting, contrary to my orders, in lying down on the rug before the fire whenever my back was turned. As I was about to leave the room, I placed the reed on the rug, and admonished him to be careful. On my return, some time afterwards, I found the reed torn up into the most minute shreds. On looking round, I saw Alp in the furthest corner of the room, twisting his mouth, wriggling about, and wagging his tail, while every now and then he turned furtive glances towards the rug, telling me as plainly as if he could speak,—“I could not resist the temptation—I did it, I own—but don’t be angry with me. You see I have now got as far away from the rug as I could be.” Alp, seeing me laugh, rushed from his corner to lick my hand. He ever afterwards, however, avoided the rug.

For his size, he was the best swimmer and diver among dogs I ever saw. He would, without hesitation, plunge into water six or eight feet deep, and bring up a stone from the bottom almost as big as his head, or dash forth from the sea-beach and boldly breast the foaming billows of the Atlantic.

After seeing what Alp did do, and feeling sure of what he could have done had circumstances called forth his powers, I am ready to believe the accounts I have heard of the wonderful performances of others of his race.

A young Newfoundland dog, living in Glasgow a few years ago, acted, under similar circumstances, very much as Alp did. As he sometimes misbehaved himself, a whip was kept near him, which was occasionally applied to his back. He naturally took a dislike to this article, and more than once was found with it in his mouth, moving slyly towards the door.

Being shut up at night in the house to watch it, he in his rounds discovered the detested instrument of punishment. To get rid of it, he attempted to thrust it under the door. It stuck fast, however, by the thick end. A few nights afterwards he again got hold of the whip, and persevered till he shoved through the thick end, when some one passing by carried it off. On being questioned as to what had become of the whip, he betrayed his guilt by his looks, and slunk away with his tail between his legs.

The Dog and the Thief.

A gentleman who lived near Stirling, possessed a powerful mastiff. One evening, as he was going his rounds through the grounds, he observed a man with a sack on his back suspiciously proceeding towards the orchard. The dog followed, crouching down while the man filled his sack with apples. The dog waited till the thief had thrown the heavy sack over his shoulders, holding on to the mouth with both hands. When the man was thus unable to defend himself, the dog rushed forward and stood in front of him, barking loudly for assistance, and leaving him the option of dropping his plunder and fighting for life and liberty, or of being captured. Paralysed with fear, he stood still, till the servants coming from the house made him prisoner.

Be calm and cool in the face of a foe—remonstrate with a wrong-doer—fly from tempters; but you cannot be too eager and violent in attacking temptation immediately it presents itself.

The Cleanly Dog.

A friend told me of another dog, which had been taught habits of cleanliness that some young gentlemen, accustomed to enter the drawing-room with dirty shoes, might advantageously imitate. A shallow tub of water was placed in the hall, near the front door. Whenever this well-behaved dog came into the house, if the roads were muddy from rain, or dusty from dry weather, he used to run to the tub and wash his feet—drying them, it is to be presumed, on the door-mat—before venturing into any of the sitting-rooms to which he had admission.

Master Rough.

Having mentioned this cleanly dog, I must next introduce to you a canine friend, called Master Rough, belonging to my kind next-door neighbours; and I think you will acknowledge that he surpasses the other in the propriety of his behaviour.

Master Rough is very small, and his name describes his appearance. As I hear his voice, I might suppose him to be somewhat ill-natured, did I not know that his bark is worse than his bite. He is only indignant at being told by his mistress to do something he dislikes; but he does it notwithstanding, though he has, it must be confessed, a will of his own, like some young folks. He does not often soil his dainty feet by going out into the muddy road; but when he does, on his return he carefully wipes them on the door-mat.

At meal-times he goes to a cupboard, in which is kept a bowl and napkin for his especial use. The napkin he first spreads on the carpet, and then placing the bowl in the centre, barks to give notice that his table is ready. After this, he sits down and waits patiently till his dinner is put into the bowl, on which he falls to and gobbles it up,—the table-cloth preventing any of the bits which tumble over from soiling the carpet. It has been asserted that he wipes his mouth afterwards in the napkin; but I suspect that he is merely picking up the bits outside. I am sorry to say that he forgets to fold up his table-cloth neatly and to put it away, which he certainly should do; nor can he be persuaded to wash out his bowl, though he does not object to lick it clean. People and dogs, however, have different ways of doing things, and Master Rough chooses to follow his way, and is perfectly satisfied with himself—like some young folks, who may not, however, be right for all that.

His principal other accomplishment is to carry up the newspaper, after it has been read by the gentleman downstairs, to his mistress in the drawing-room, when he receives a cake as his reward. He also may be seen carrying a basket after his mistress, with a biscuit in it, which he knows will be his in due time; but that if he misbehaves himself by gobbling it greedily up—as he has sometimes done, I hear—he will have to carry the basket without the biscuit; so having learned wisdom from experience, he now patiently waits till it is given to him.

If Master Rough is not so clever as some dogs I have to tell you about, he does his best in most respects; and I am very sure that no thief would venture to break into the house in which he keeps watch: so that he makes himself—what all boys and girls should strive to be—very useful.

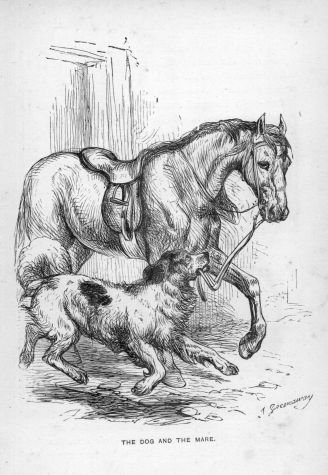

Byron, the Newfoundland Dog.

Next on my list of canine favourites stands a noble Newfoundland dog named Byron, which belonged to the father of my friend, Mrs F—. On one occasion he accompanied the family to Dawlish, on the coast of Devonshire. His kennel was at the back of the house. Whenever his master was going out, the servant loosened Byron, who immediately ran round, never entering the house, and joined him, accompanying him in his walk.

One day, after getting some way from home, his master found that he had forgotten his walking-stick. He showed the dog his empty hands, and pointed towards the house. Byron, instantly comprehending what was wanted, set off, and made his way into the house by the front door, through which he had never before passed. In the hall was a hatstand with several walking-sticks in it. Byron, in his eagerness, seized the first he could reach, and carried it joyfully to his master. It was not the right one, however. Mr — on this patted him on the head, gave him back the stick, and again pointed towards the house. The dog, apparently considering for a few moments what mistake he could have made, ran home again, and exchanged the stick for the one his master usually carried. After this, he had the walking-stick given him to carry, an office of which he seemed very proud.

One day while thus employed, following his master with stately gravity, he was annoyed during the whole time by a little yelping cur jumping up at his ears. Byron shook his head, and growled a little from time to time, but took no further notice, and never offered to lay down the stick to punish the offender.

On reaching the beach, Mr — threw the stick into the waves for the dog to bring it out. Then, to the amusement of a crowd of bystanders, Byron, seizing his troublesome and pertinacious tormentor by the back of the neck, plunged with him into the foaming water, where he ducked him well several times, and then allowed him to find his way out as best he could; while he himself, mindful of his duty, swam onward in search of the now somewhat distant walking-stick, which he brought to his master’s feet with his usual calm demeanour. The little cur never again troubled him.

Be not less magnanimous than Byron, when troublesome boys try to annoy you whilst you are performing your duties; but employ gentle words instead of duckings to silence them. Drown the yelping curs—bad thoughts, unamiable tempers, temptations, and such like—which assault you from within.

The Newfoundland Dog and the marked Shilling.

I must now tell you a story which many believe, but which others consider “too good to be true.”

A gentleman who owned a fine Newfoundland dog, of which he was very proud, was one warm summer’s evening riding out with a friend, when he asserted that his dog would find and bring to him any article he might leave behind him. Accordingly it was agreed that a shilling should be marked and placed under a stone, and that after they had proceeded three or four miles on their road, the dog should be sent back for it. This was done—the dog, which was with them, observing them place the coin under the stone, a somewhat heavy one. They then rode forward the distance proposed, when the dog was despatched by his master for the shilling. He seemed fully to understand what was required of him; and the two gentlemen reached home, expecting the dog to follow immediately. They waited, however, in vain. The dog did not make his appearance, and they began to fear that some accident had happened to the animal.

The faithful dog was, however, obedient to his master’s orders. On reaching the stone he found it too heavy to lift, and while scraping and working away, barking every now and then in his eagerness, two horsemen came by. Observing the dog thus employed, one of them dismounted and turned over the stone, fancying that some creature had taken refuge beneath it. As he did so, his eye fell on the coin, which—not suspecting that it was the object sought for—he put into his breeches pocket before the animal could get hold of it. Still wondering what the dog wanted, he remounted his steed, and with his companion rode rapidly on to an inn nearly twenty miles off, where they purposed passing the night.

The dog, which had caught sight of the shilling as it was transferred to the stranger’s pocket, followed them closely, and watched the sleeping-room into which they were shown. He must have observed them take off their clothes, and seen the man who had taken possession of the shilling hang his breeches over the back of a chair. Waiting till the travellers were wrapped in slumber, he seized the garment in his mouth—being unable to abstract the shilling—and bounded out of the window, nor stopped till he reached his home. His master was awakened early in the morning by hearing the dog barking and scratching at his door. He was greatly surprised to find what he had brought, and more so to discover not only the marked shilling, but a watch and purse besides. As he had no wish that his dog should act the thief, or that he himself should become the receiver of stolen goods, he advertised the articles which had been carried off; and after some time the owner appeared, when all that had occurred was explained.

The only way to account for the dog not at first seizing the shilling is, that grateful for the assistance afforded him in removing the stone, he supposed that the stranger was about to give him the coin, and that he only discovered his  mistake when it was too late. His natural gentleness and generosity may have prevented him from attacking the man and trying to obtain it by force.

mistake when it was too late. His natural gentleness and generosity may have prevented him from attacking the man and trying to obtain it by force.

Patiently and perseveringly follow up the line of duty which has been set you. When I see a boy studying hard at his lessons, or doing his duty in any other way, I can say, “Ah, he is searching for the marked shilling; and I am sure he will find it.”

The lost Keys.

Many species of dogs appear, like the last mentioned, to be especially indued with the faculty of distinguishing their master’s property, and to possess the desire of restoring it to them when lost.

Mrs F— told me of an instance of this with which she was acquainted. A gentleman residing in the county of Cork, finding his out-houses infested by rats, sent for four small terriers to extirpate them. He amused himself with teaching the dogs a variety of canine accomplishments,—among others, to fetch and carry whatever he sent them for.

Returning one day from his daily walk, he discovered that a bunch of keys which he supposed was in his pocket was not there. Hoping that he might have left them at home, he made diligent search everywhere, but in vain. One of the little terriers had observed his master thus searching about, and there can be no doubt that, after pondering the matter in his mind, he came to the conclusion that something was lost. Be that as it may, off he set by himself from the house, and after the lapse of some hours up he came running with eager delight, the lost keys dangling from his mouth, and jingling loudly as he gambolled about in his happiness. He then dropped them at his master’s feet.

We may be sure that the dog was well caressed, and became from thenceforward the prime favourite.

That terrier was a little dog, but still he was of much use, not only by killing rats, which was his regular duty, but by trying to find out what his master wanted to have done, and doing it.

Little boys and girls may be of still greater use, if they will both perform their regular duties, and try to find out what there is to be done, and then, like the terrier, do it.

The Dog which acted as Constable.

Mrs F— told me another anecdote, which illustrates the fidelity and reasoning power so frequently exhibited by the shepherd’s dog.

About the year 1827, her father sold some lambs to a butcher in Melrose, who took them away in his cart. Their shepherd had a young dog in training at the time. Shortly after the sale of the lambs he missed this dog, and hastened in search of him.

On reaching the chain bridge which is thrown over the river for the use of foot-passengers, he was told that the dog had been seen standing on it watching the butcher’s cart containing the lambs, which was crossing the ford beneath. As soon as it had gained the other bank the dog followed it to Melrose. The shepherd pursued the supposed truant till he reached the town, where in front of the butcher’s shop stood the cart with the lambs still in it, and the dog standing like a constable by it, threatening every one who approached to unload it.

He had evidently considered that the animals were stolen, and that it was his duty to keep watch over them. When, however, his master appeared, and called him away, he seemed at once to understand that all was right, and followed him willingly.

Be watchful over whatever is committed to your charge, and be equally watchful over yourself.

The lost Child recovered.

In the backwoods of North America lived a settler and his family, far away from towns and villages. The children of such families at an early age learn to take care of themselves, and fearlessly wander to a distance from home to gather wild fruits, to fish in the streams, or to search for maple-trees from which to extract sugar in the autumn.

One evening the rest of the boys and girls had come in from their various occupations, except the youngest, a little fellow of four or five years old. One of his brothers thought he had gone with Silas, and Silas fancied that he was with James and Mary, but neither of them till then  had missed him. The whole family, thrown into a state of consternation, hurried out with torches, for it was now getting dark, and shouted for him, and searched round and round the clearing far and wide, but he was nowhere to be found. I need not describe their feelings. The next morning they set forth again, searching still further. All day they were so employed, but in vain. They began to fear that poor little Marcus had been killed by a rattlesnake, or that a bear had come and carried him off.

had missed him. The whole family, thrown into a state of consternation, hurried out with torches, for it was now getting dark, and shouted for him, and searched round and round the clearing far and wide, but he was nowhere to be found. I need not describe their feelings. The next morning they set forth again, searching still further. All day they were so employed, but in vain. They began to fear that poor little Marcus had been killed by a rattlesnake, or that a bear had come and carried him off.

The next night was a sorrowful one for all the family. Once more they were preparing to set out, when a tall, copper-coloured Indian, habited in a dress of skins, was seen coming through the forest, followed by a magnificent blood-hound. He approached the settlers and inquired what was the matter. They told him, when he desired to see the socks and shoes last worn by the child. They were eagerly produced by the mother. The Indian showed them to his dog, at the same time patting him on the head. The animal evidently comprehended what his master required, and scenting about for a short time, began to bay loudly, then set off, without turning to the right or to the left, through the forest, followed by the Indian and the child’s father and elder brothers. He was soon out of sight, but the Indian knew by the marks on the ground the way he had taken.

A long, long chase the hound led them, till he was seen bounding back with animation in his eye and a look which told that he had been successful in his search. The father and his sons hurried after the Indian, who closely followed his dog, and to their joy discovered little Marcus, pale and exhausted, but unhurt, with the dog standing over him.

He soon recovered, and told them how he had lost his way, and lived upon berries and other wild fruits till he had sunk down unable to go further. His life had undoubtedly been preserved by means of the sagacious blood-hound.

Dog waking up Servants.

I have told you of Tyrol, who used to ring the bell; I will now describe another dog named Dash, who was still more clever. When any of the servants of the family had to sit up for their master or mistress, and fell asleep in their chair, scarcely would they have settled themselves when the parlour bell would be heard to ring. They were greatly puzzled to account for this, and in vain attempted to solve the mystery.

Dash was a black and white spaniel, who was generally considered a fairly clever dog, but not suspected of possessing any unusual amount of knowingness. He never failed, when his master told him to get anything, to find it and lay it at his feet. If one glove was missing, and the other shown to him, he was sure to hunt about till he discovered it.

One morning a person arrived with a letter before breakfast, to be delivered into the hands of Dash’s master. The man was shown into the parlour, where he was about to sit down, when his ears were saluted by a growl, and there was Dash, seated in a chair near the fireplace. The dog was within reach of the ring of the bell-pull, and whenever the man attempted to sit down, Dash put up his paw on the ring and growled again. At length the stranger, curious to see what the dog would do if he persevered, sat down in a chair. Dash, on this, instead of flying at the man, as some stupid dogs would have done, pulled the bell-rope, and a servant coming in on the summons, was greatly astonished when the man told him that the dog had rung the bell.

Thus the mystery which had long puzzled him and his fellow-servants was explained. On comparing notes, they recollected that whenever the bell sounded, Dash was not to be seen; and there could now be no doubt that immediately he observed them closing their eyes, he had hastened off to the parlour, the bell-rope of which he could easily reach, in order to rouse them to watchfulness.