The Project Gutenberg EBook of The International Magazine, Volume 2, No. 2, January, 1851, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The International Magazine, Volume 2, No. 2, January, 1851 Author: Various Release Date: September 21, 2007 [EBook #22694] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE *** Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by Cornell University Digital Collections).

Transcriber's note: Minor typos have been corrected and footnotes moved to the end of the article. Table of Contents has been created for the HTML version.

EDMUND BURKE.

POEMS BY S. G. GOODRICH

RICHARD B. KIMBALL.

THE BISHOP OF JAMAICA.

ENCOURAGEMENT OF LITERATURE.

CLASSICAL NOVELS.

SLIDING SCALE OF THE INCONSOLABLES.

A NEW SERIES OF TALES BY MISS MARTINEAU.

ON THE ATTEMPTS TO DISCOVER THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE.

RECOLLECTIONS OF PAGANINI.

A PEASANT DUCHESS.

ORIGINAL CORRESPONDENCE.

AUTHORS AND BOOKS.

THE FINE ARTS.

RECENT DEATHS.

SPIRIT OF THE ENGLISH ANNUALS.

A STORY WITHOUT A NAME.

CYPRUS AND THE LIFE LED THERE.

THE COUNT MONTE-LEONE,

BALLAD OF JESSIE CAROL.

A STORY OF CALAIS.

LIFE AT A WATERING-PLACE.

THE MYSTIC VIAL:

MAZZINI ON ITALY.

THE MOTHER'S LAST SONG.

A DRIVE ABOUT MY NEIGHBORHOOD IN 1850.

STANZAS.

MY NOVEL:

GLEANINGS FROM THE JOURNALS.

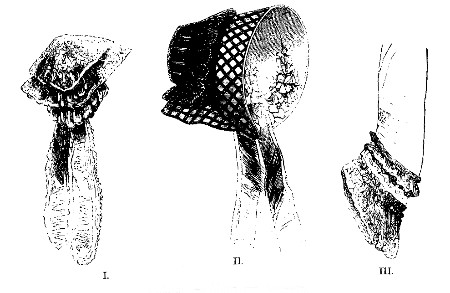

LADIES' FASHIONS FOR JANUARY.

Edmund Burke is the most illustrious name in the political history of England. The exploits of Marlborough are forgotten, as Wellington's will be, while the wisdom and genius of Burke live in the memory, and form a portion of the virtue and intelligence of the British nation and the British race. The reflection of this superior power and permanence of moral grandeur over that which, at best, is but a vulgar renown, justifies the most sanguine expectations of humanity.

It may be said of Burke, as it was said by him of another, that "his mind was generous, open, sincere; his manners plain, simple, and noble; rejecting all sorts of duplicity and disguise, as useless to his designs, and odious to his nature. His understanding was comprehensive, steady, and vigorous, made for the practical business of the state.... His knowledge, in all things which concerned his duty was profound.... He was not more respectable on the public scene, than amiable in private life.... A husband and a father, the kindest, gentlest, most indulgent, he was every thing in his family, except what he gave up to his country.... An ornament and blessing to the age in which he lived, his memory will continue to be beneficial to mankind, by holding forth an example of pure and unaffected virtue, most worthy of imitation, to the latest posterity."

In the last of a series of articles by Mrs. S. C. Hall, entitled "Pilgrimages to English Shrines," and published in the London Art Journal, we have an account of a visit to the residences and to the [Pg 146]grave of Burke, which we reproduce in the following pages, with its interesting illustrations.

It has been said that we are inclined to over-value great men when their graves have been long green, or their monuments gray above them, but we believe it is only then we estimate them as they deserve. Prejudice and falsehood have no enduring vitality, and posterity is generally anxious to render justice to the mighty dead; we dwell upon their actions,—we quote their sentiments and opinions,—we class them amongst our household gods—and keep their memories green within the sanctuary of our homes; we read to our children and friends the written treasures bequeathed to us by the genius and independence of the great statesmen and orators—the men of literature and science—who "have been." We adorn our minds with the poetry of the past, and value it, as well we may, as far superior to that of the present: we sometimes, by the aid of imagination—one of the highest of God's gifts—bring great men before us: we hear the deep-toned voices and see the flashing eyes of some, who, it may be, taught kings their duty, or quelled the tumults of a factious people: we listen to the lay of the minstrel, or the orator's addresses to the assembly, and our pulses throb and our eyes moisten as the eloquence flows—first, as a gentle river, until gaining strength in its progress, it sweeps onwards like a torrent, overcoming all that sought to impede its progress. What a happy power this is!—what a glorious triumph over time!—recalling or creating at will!—peopling our small chamber with the demigods of history; viewing them enshrined in their perfections, untainted by the world; hearing their exalted sentiments; knowing them as we know a noble statue or a beautiful picture, without the taint of age or feebleness, or the mildew of decay.

If these sweet wakening dreams were more frequent, we should be happier; yes, and better than we are; we should be shamed out of much baseness—for nothing so purifies and exalts the soul as the actual or imaginary companionship of the pure and exalted; no man who purposed to create a noble picture would choose an imperfect model; no one who seeks virtue and cherishes honor and honorable things, will endure the degradation of ignoble persons or ignoble thoughts; no one ever achieved a great purpose who did not plant his standard on high ground.

A little before the commencement of the present century, England was rich in orators, and poets, and men of letters; the times were favorable to such—events called them forth—and there was still a lingering chivalric feeling in our island which the utilitarian principles or tastes of the present period would now treat with neglect, if not contempt.

The progress of the French Revolution agitated Europe; and men wondered if the young Corsican would ever dare to wield the sceptre wrenched from the grasp of a murdered king; people were continually on the watch for fresh events; great stakes were played for all over Europe, and those who desired change were full of hope. It was an age to create great men.

Let us then indulge in visions of those, who, in more recent times than we have yet touched upon,—save in one or two Pilgrimages,—illumed the later days of the last century; and, brightest and purest of the galaxy was the orator, Edmund Burke. Ireland, which gave him birth, may well be proud of the high-souled and high-gifted man, who united in himself all the great qualities which command attention in the senate and the world, and all the domestic virtues that sanctify home; grasping a knowledge of all things, and yet having that sweet sympathy with the small things of life, which at once bestows and secures happiness, and, in the end, popularity.

Edmund Burke was born on Arran Quay, Dublin, January the 1st, 1730; his father was an attorney: the name, we believe, was originally spelt Bourke.

The great grandfather of Edmund inherited some property in that county which has produced so many men of talent—the county of Cork; the family resided in the neighborhood of Castletown Roche, four or five miles from Doneraile, five or six miles from Mallow—now a railroad station—and nearly the same distance from the ruins of Kilcolman Castle, whose every mouldering stone is hallowed by the memory of the poet Spenser and his dear friend, "the Shepherd of the Ocean," Sir Walter Raleigh. There can be little doubt that Edmund—a portion of whose young life was passed in this beautiful locality—imbibed much thought, as well as much poetry, from the sacred memories which here accompanied him during his wanderings.

Nothing so thoroughly awakens the sympathy of the young as the imaginary presence of the good and great amid the scenes where their most glorious works were accomplished; the associations connected with Kilcolman are so mingled, that their contemplation produces a variety of emotions—admiration for the poem which was created within its walls—contemplation of the "glorious two" who there spent so much time together in harmony and sweet companionship, despite the storms which ravaged the country; then the awful catastrophe, the burning of the castle, and the loss of Spenser's child in the flames, still talked of in the neighborhood, were certain to make a deep impression on the imagination of a boy whose delicate health prevented his rushing into the amusements and society of children of his own age. There are plenty of crones in every village, and one at least in every gentleman's house to watch "the master's children" and pour legendary lore into their willing ears, accompanied by snatches of song and fairy tale. All these were certain to seize upon such an imagination as that of Burke, and lay the foundation of much of that high-souled mental poetry—one of his great characteristics; indeed, the circumstances of his youth were highly favorable to his peculiar temperament—his delicate constitution rendered him naturally susceptible of the beautiful; and the locality of the Blackwater, and the time-honored ruins of Kilcolman, with its history and traditions, nursed, as they were, by the holy quiet of a country life, had ample time to sink into his soul and germinate the fruitage which, in after years, attained such rich perfection.

An old schoolmaster, of the name of O'Halloran, was his first teacher; he "played at learning" at the school, long since in ruins; and the Dominie used to boast that "no matter how great Master Edmund (God bless him) was, he was the first who ever put a Latin grammar into his hands."

Edmund was one of a numerous family; his[Pg 147] mother, who had been a Miss Nagle,[1] having had fourteen or fifteen children, all of whom died young, except four,—one sister and three brothers: the sister, Mrs. French, was brought up in the faith of her mother, who was a rigid Roman Catholic, while the sons were trained in the father's belief. This, happily, created no unkindness between them, for not only were they an affectionate and a united family, but perfectly charitable in their opinions, each of the other's creed. As the future statesman grew older, it was considered wise to remove him to Dublin for better instruction, and he was placed at a school in Smithfield kept by a Mr. James Fitzgerald; but, fortunately for his strength of body and mind, the reputation of an academy in the lovely valley of Ballitore, founded in the midst of a colony of Quakers, by a member of that most benevolent and intelligent society—the well-known Abraham Shackleton—was spreading far and wide; and there the three young Burkes were sent in 1741, Edmund being then twelve years old.

He was considered not so much brilliant, as of steady application. Here, too, he was remarkable for quick comprehension, and great strength of memory; indications which drew forth at first the commendation, and as his powers unfolded, the warm regard of his master; under whose paternal care the improvement of his health kept pace with that of his intellect, and the grateful pupil never forgot his obligations: a truly noble mind is prone to exaggerate kindnesses received, and never detracts from their value; it is only the low and the narrow-minded who underrate the benefits they have been blessed with at any period of their lives.

In 1743 he entered Trinity College, Dublin, as a pensioner. He gained fair honors during his residence there, but, like Johnson, Swift, Goldsmith, and other eminent men, he did not distinguish himself so as to lead to any speculation as to his after greatness, although his elders said he was more anxious to acquire knowledge than to display it;—a valuable testimony. His domestic life was so pure, his friendships were so firm, his habits so completely those of a well-bred, well-born Irish Gentleman—mingling, as only Irish gentlemen can do, the suavity of the French with the dignity of English manners—that there is little to write about, or speculate upon, beyond his public words and deeds.

Like most young men of his time, his first oratory was exercised at a club, and his first efforts as a politician were made in 1749, previous to his quitting the Dublin University, in some letters against Mr. Henry Brooke, the author of "Gustavus Vasa." His determination was the bar, and his entry at the Middle Temple bears date April 23, 1747. His youthful impressions of England and its capital are recorded in graceful language in his letters to those friends whom he never lost, but by death; one passage is as applicable to the present as to the past. "I don't find that genius, the 'rath primrose which forsaken dies,' is patronized by any of the nobility, so that writers of the first talents are left to the capricious patronage of the public."

It was the taste of his time to desire, if not solicit patronage. In our opinion literature is degraded by patronage, while it is honored by the friendship of the good and great. Nothing is so loathsome in the history of letters as the debased dedications which men of mind some years ago laid at the feet of the so-styled "patron!" Literature in our days has only to assert its own dignity, to be true and faithful to the right, to avoid ribaldry, and preserve a noble and brave independence; and then its importance to the state, as the minister of good, must be acknowledged. It is only when forgetful of great purposes and great power, that literature is open to be forgotten or sneered at. Still the indifference an Englishman feels towards genius, even while enjoying its fruits, was likely enough to check and chill the enthusiasm of Burke, and drive him to much mystery as to his early literary engagements. One of his observations made during his first visit to Westminster Abbey, while hopes and ambitions quickened his throbbing pulse, and he might have been pardoned for wishing for a resting-place in the grand mausoleum of England, is remarkable, as showing how little he changed, and how completely the youth

"Yet after all, do you know that I would rather sleep in the southern corner of a country church-yard than in the tomb of the Capulets? I should like, however, that my dust should mingle with kindred dust; the good old expression, 'family burying-grounds,' has something pleasant in it, at least to me."

This was his last, as it seems to have been his first desire; and it has found an echo in many a richly dowered heart.

"Lay me," said Allan Cunningham, "where the daisies can grow on my grave;" and it is well known that Moore—

and, as a poor Irishman once rendered it—

has frequently expressed a desire to be buried at Sloperton beside his children.

The future orator found the law, as a profession, alien to his habits and feelings, for at the expiration of the usual term he was not even called to the bar. Some say he desired the professorship of logic at the University of Glasgow, and even stood the contest; but this has been disputed, and if he was rejected, it is matter of congratulation, that his talents and time were not confined to so narrow a sphere. At that period his mind was occupied by his theories on the Sublime and Beautiful, which were finally condensed and published in the shape of that essay which roused the world to admiration.

Mr. Prior says, and with every show of reason, "that Mr. Burke's ambition of being distinguished in literature, seems to have been one of his earliest, as it was one of his latest, passions." His first avowed work was "The Vindication of Natural Society;" but he wrote a great deal anonymously; and the essay on "The Sublime and Beautiful," triumphant as it was, must have caused him great anxiety; he began it before he was nineteen, and kept it by him for seven years before it was published—a valuable lesson to those who rush into print and mistake the desire for celebrity, for the power which bestows immortality.

The literature which is pursued chiefly in solitude,[Pg 148] is always the best sort: society, which cheers and animates men in most employments, is an impediment to an author if really warmed by true genius, and impelled by a sacred love of truth not to fritter away his thoughts or be tempted to insincerity.

The genius and noble mind of Burke constituted him a high priest of literature; the lighter, and it might be the more pleasurable enjoyments of existence, could not be tasted without interfering with his pursuits; but he knew his duty to his God, to the world, and to himself, and the responsibility alone was sufficiently weighty to bend a delicate frame, even when there was no necessity for laboring to live—but where an object is to be attained, principles put forth or combated, God or man to be served, the necessity for exertion always exists, and the great soul must go forth on its mission.

That sooner or later this strife, or love, or duty—pursued bravely—must tell upon all who even covet and enjoy their labor, the experience of the past has recorded; and Edmund Burke, even at that early period of life, was ordered to try the effects of a visit to Bath and Bristol, then the principal resort of the invalids of the United Kingdom.

At Bath he exchanged one malady for another, for he became attached to Miss Nugent, the daughter of his physician, and in a very little time formed what, in a worldly point of view, would be considered an imprudent marriage, but which secured the happiness of his future life; she was a Roman Catholic; but, however unfortunate dissenting creeds are in many instances, in this it never disturbed the harmony of their affection.

She was a woman exactly calculated to create happiness; possessing accomplishments, goodness of heart, sweetness of disposition and manners, veneration for talent, a hopeful spirit to allay her husband's anxieties, wisdom and love to meet his ruffled temper, and tenderness to subdue it—qualities which made him frequently declare "that every care vanished the moment he sheltered beneath his own roof."

Edmund Burke became a husband, and also continued a lover—and once presented to his ladylove, on the anniversary of their marriage, his idea of "a perfect wife."[2]

For a considerable time after his marriage Burke toiled as a literary man, living at Battersea or in town, now writing, it is believed, jointly with his brother Richard and his cousin William a work on the "European Settlements in America," in two volumes, which, according to tradition, brought him, or them, only fifty pounds! then planning and commencing an abridgment of the "History of England."

Struggling, it may be with difficulties brought on by his generous nature, and which his father's allowance of two hundred a year, and his own industry and perseverance could hardly overcome, the birth of a son was an additional stimulant to exertion, and, in conjunction with Dodsley, he established the Annual Register. This work he never acknowledged, but his best biographers have no doubt of his having brought forth and nurtured this useful publication. A hundred pounds a volume seems to have been the sum paid for this labor; and Burke's receipts for the money were at one time in the possession of Mr. Upcott.

Long before he obtained a seat in Parliament he won the esteem of Doctor Johnson, who bore noble testimony to his virtue and talent, and what he especially admired, and called, his "affluence of conversation."

For a time he went to Ireland as private secretary to Mr. Hamilton, distinguished from all others of his name as "single-speech Hamilton;" but disagreeing with this person, he nobly threw up a pension of three hundred a year, because of the unreasonable and derogatory claims made upon his gratitude by Hamilton, who had procured it for him.

While in Dublin he made acquaintance with the genius of the painter Barry, and though his own means were limited, he persuaded him to come to England, and received him in his house in Queen Anne-street, where he soon procured him employment; he already numbered Mr., afterwards Sir Joshua, Reynolds amongst his friends; and his correspondence with Barry might almost be considered a young painter's manual, so full is it of the better parts of taste, wisdom, and knowledge.

Mr. Burke was then on the threshold of Parliament, Lord Verney arranging for his début as member for Wendover, in Buckinghamshire, under the Rockingham administration; another star was added to the galaxy of that brilliant assembly, and if we had space it could not be devoted to a better purpose than to trace his glorious career in the senate; but that is before all who read the history of the period, and we prefer to follow his footsteps in the under current of private life.

He was too successful to escape the poisoned arrows of envy, or the misrepresentations of the disappointed. Certain persons exclaimed against his want of consistency, and gave as a reason that[Pg 149] at one period he commanded the spirit of liberty with which the French Revolution commenced, and after a time turned away in horror and disgust from a people who made murder a pastime, and converted Paris into a shambles for human flesh.

But nothing could permanently obscure the fame of the eloquent Irishman, he continued to act with such worthiness, that, despite his schism with Charles James Fox, "the people" did him the justice to believe, that in his public conduct, he had no one view but the public good.

He outlived calumny, uniting unto genius diligence, and unto diligence patience, and unto patience enthusiasm, and to these, deep-hearted enthusiasm, with a knowledge, not only, it would seem, of all things, but of such ready application, that in illustration or argument his resources were boundless; the wisdom of the Ancients was as familiar to him as the improved state of modern politics, science, and laws; the metaphysics and logic of the Schools were to him as household words, and his memory was gemmed with whatever was most valuable in poetry, history, and the arts.

GREGORIES.

GREGORIES.

After much toil, and the lapse of some time, he purchased a domain in Buckinghamshire, called "Gregories;" there, whenever his public duties gave him leisure, he enjoyed the repose so necessary to an overtaxed brain; and from Gregories some of his most interesting letters are dated.[3] Those addressed to the painter Barry, whom his liberality sent to and supported in Rome, are, as we have said, replete with art and wisdom; and the delicacy of both him and his excellent brother Richard, while entreating the rough-hewn genius to prosecute his studies and give them pleasure by his improvement, are additional proofs of the beautiful union of the brothers, and of their oneness of purpose and determination that Barry should never be cramped by want of means.[4]

After the purchase of Gregories[5] Mr. Burke had no settled town-house, merely occupying one for the season. In one of his letters to Barry, he tells him to direct to Charles-street, St. James's Square; he writes also from Fludyer-street, Westminster, and from Gerrard-street, Soho; but traces of his "whereabouts" are next to impossible to find. Barry was not the only artist who profited by Edmund Burke's liberality. Barret, the landscape-painter, had fallen into difficulties, and the fact coming to the orator's ears during his short tenure in power, he bestowed upon him a place in Chelsea Hospital, which he enjoyed during the remainder of his life.

Indeed, this great man's noble love of Art was part and parcel of himself; it was no affectation, and it led to genuine sympathy with, not only the artist's triumphs, but his difficulties. He found time, amid all his occupations, to write letters to the irritable Barry, and if the painter had followed their counsel, he would have secured his peace and prosperity; but it was far otherwise: his conduct, both in Rome and after his return to England, gave his friend just cause of offence; though, like all others who offended the magnanimous Burke, he was soon forgiven.

He never forgot his Irish friends, or the necessities of those who lived on the family estate; the expansive generosity of his nature did not prevent his attending to the minor comforts of his dependants, and his letters "home" frequently breathe a most loving and careful spirit, that the sorrows of the poor might be ameliorated, and their wants relieved.

We ought to have mentioned before that Mr. and Mrs. Burke's marriage was only blessed by two sons; one died in childhood, the eldest grew up a young man of the warmest affections, and blessed with a considerable share of talent; to his parents he was every thing they could desire; towards his mother he exhibited the tenderness and devotion of a daughter, and his demeanor to his father was that of an obedient son, and most faithful friend; at intervals he enjoyed with them the pleasure they experienced in receiving guests of the highest consideration; amongst them the eccentric Madame de Genlis, who put their politeness to the test by the exercise of her peculiarities,[Pg 150] and horrified the meek and amiable Sir Joshua Reynolds by the assumption of talents she did not possess.

The publication of his reflections on the French Revolution, which, perhaps, never would have seen the light but for the rupture with Mr. Sheridan, which caused his opinions to be misunderstood, brought down the applause of Europe on a head then wearying of public life.

But, perhaps, a tribute Burke valued more than any, remembering the adage—an adage which, unhappily, especially applies to Ireland—"no man is a prophet in his own country," was, that on a motion of the provost of Trinity College, Dublin, in 1790, the honorary degree of LL.D. was conferred upon him in full convocation, and an address afterwards presented in a gold box, to express the University's sense of his services. When he replied to this distinguished compliment, his town residence was in "Duke-street, St. James."

His term of life—over-tasked as it was—might have been extended to a much longer period, but that his deeply affectionate nature, as time passed on, experienced several of those shocks inseparable from even moderate length of days; many of his friends died; among others, his sister and his brother; but still the wife of his bosom and his son were with him—that son whose talents he rated as superior to his own, whom he had consulted for some years on almost every subject, whether of a public or a private nature, that occurred, and very frequently preferred his judgment to his own. This beloved son had attained the age of thirty-four, when he was seized with rapid consumption. When the malady was recognized and acknowledged, his father took him to Brompton, then, as now, considered the best air for those affected with this cruel malady. "Cromwell House," chosen as their temporary residence, is standing still, though there is little doubt the rage for extending London through this once sequestered and rural suburb, will soon raze it to the ground, as it has done others of equal interest.

CROMWELL HOUSE.

CROMWELL HOUSE.

We have always regarded "Cromwell House," as it is called, with veneration. In our earliest acquaintance with a neighborhood, in which we lived so long and still love so well, this giant dwelling, staring with its whited walls and balconied roof over the tangled gardens which seemed to cut it off from all communication with the world, was associated with our "Hero Worship" of Oliver Cromwell. We were told he had lived there (what neighborhood has not its "Cromwell House?")—that the ghastly old place had private staircases and subterranean passages—some underground communication with Kensington—that there were doors in the walls, and out of the walls; and, that if not careful you might be precipitated through trap-doors into some unfathomable abyss, and encounter the ghost of old Oliver himself. These tales operated upon our imagination in the usual way; and many and many a moonlight evening, while wandering in those green lanes—now obliterated by Onslow and Thurloe Squares—and listening to the nightingales, have we watched the huge shadows cast by that solitary and melancholy-looking house, and, as we have said, associated it with the stern and grand Protector of England. Upon closer investigation, how grieved we have often been to discover the truth, for it destroyed not only our castles in the air, but their inhabitants; we found that Oliver never resided there, but that his son, Richard, had, and was a rate payer to the parish of Kensington for some time. To this lonely sombre house Mr. and Mrs. Burke and their son removed, in the hope that the soft mild air of this salubrious neighborhood might restore his failing strength; the consciousness of his being in danger was something too terrible for them to think of. He had just received a new appointment—an appointment suited to his tastes and expectations; he must take possession of it in a little time. He was their child, their friend, their treasure, their all! Surely God would spare him to close their eyes. How could death and he meet together? They entreated him of God, by prayer, and supplication, and tears that flowed until their eyes were dry and their eyelids[Pg 151] parched—but all in vain. The man, in his prime of manhood, was stricken down; we transcribe, from an article in the Quarterly Review, on "Fontenelle's Signs of Death," the brief account of his last moments:

"Burke's son, upon whom his father has conferred something of his own celebrity, heard his parents sobbing in another room at the prospect of an event they knew to be inevitable. He rose from his bed, joined his illustrious father, and endeavored to engage him in a cheerful conversation. Burke continued silent, choked with grief. His son again made an effort to console him. 'I am under no terror,' he said; 'I feel myself better and in spirits, and yet my heart flutters, I know not why. Pray, talk to me, sir! talk of religion; talk of morality; talk, if you will, of indifferent subjects.' Here a noise attracted his notice, and he exclaimed, 'Does it rain?—No; it is the rustling of the wind through the trees.' The whistling of the wind and the waving of the trees brought Milton's majestic lines to his mind, and he repeated them with uncommon grace and effect:

A second time he took up the sublime and melodious strain, and, accompanying the action to the word, waved his own hand in token of worship, and sank into the arms of his father—a corpse. Not a sensation told him that in an instant he would stand in the presence of the Creator to whom his body was bent in homage, and whose praises still resounded from his lips."

The account which all the biographies of Burke give of the effect this bereavement produced upon his parents is most fearful even to read; what must it have been to witness? His mother seems to have regained her self-possession sooner than his father. In one of his letters to the late Baron Smith, he writes—"So heavy a calamity has fallen upon me as to disable me from business, and disqualifies me for repose. The existence I have—I do not know that I can call life. * * Good nights to you—I never have any." And again—"The life which has been so embittered cannot long endure. The grave will soon close over me, and my dejections." To Lord Auckland he writes—"For myself, or for my family (alas! I have none), I have nothing to hope or to fear in this world." And again in another letter—"The storm has gone over me, and I lie like one of those old oaks which the late hurricane has scattered about me. I am stripped of all my honors, I lie prostrate on the earth; I am alone, I have none to meet my enemies in the gate. I greatly deceive myself, if in this hard season of life, I would give a peck of refuse wheat for all that is called fame and honor in the world."

There is some thing in the "wail" and character of these laments that recalls the mournful Psalms of David; like the Psalmist he endeavored to be comforted, but it was by an effort. His political career was shrouded for ever—the motive to his great exertions was destroyed—but his mind, wrecked as it had been, could not remain inactive. In 1795 his private reply to Mr. Smith's letter, requesting his opinion of the expediency of and necessity for Catholic Emancipation, got into public circulation; and in that singular document, though he did not enter into the details of the question with as much minuteness as he would previously have done, he pleaded for the removal of the whole of the disabilities of the Roman Catholic body. From time to time he put forth a small work on some popular question. He originated several plans for benefiting the poor in his own neighborhood. He had a windmill in his park for the purpose of supplying the poor with cheap bread, which bread was served at his own table; and, as if clinging to the memory of the youth of his son, he formed a plan for the establishment of an emigrant school at Penn, where the children of those who had perished by the guillotine or the sword amid the French convulsions, could be received, supported, and educated. He made a generous appeal to government for the benefit of these children, which was as generously responded to. The house appropriated to this humane purpose had been inhabited by Burke's old friend, General Haviland; and after his death several emigré French priests sheltered within its walls. Until his last fatal illness Mr. Burke watched over the establishment with the solicitude of a friend and the tenderness of a father. The Lords of the Treasury allowed fifty pounds per month for its sustenance: the Marquis of Buckingham made them a present of a brass cannon and a stand of colors. When the Bourbons were restored in 1814 they relieved the government from this charge, and the institution was dissolved in 1820; in 1822 "Tyler's Green House," as it was called, was sold in lots, pulled down, and carried away; thus, Burke's own dwelling being destroyed by fire, and this building, sanctified by his sympathy and goodness, razed to the ground, little remains to mark the locality of places where all the distinguished men of the age congregated around "the Burkes," and where Edmund, almost to the last, extended hospitalities, coveted and appreciated by all who had any pretensions to be considered as distinguished either by talent or fortune.

It has frequently struck us as strange, the morbid avidity with which the world seizes upon the slightest evidence of abstraction in great men, to declare that their minds are fading, or impoverished: the public gapes for every trifle calculated to prove that the palsied fingers can no longer grasp the intellectual sceptre, and that the well-worn and hard-earned bays are as a crown of thorns to the pulseless brow. It was, in those days whispered in London that the great orator had become imbecile immediately after the publication of his "Letter to a Noble Lord;" and that he wandered about his park kissing his cows and horses.

A noble friend went immediately to Beaconsfield to ascertain the truth, and was delighted to find Mr. Burke anxious to read him passages from "A Regicide Peace," which he was then writing; after a little delicate manœuvring on his part, to ascertain the truth, Mr. Burke told him a touching incident which proved the origin of this calumny on his intellectual powers.

An old horse, a great favorite of his son's, and his constant companion, when both were full of life and health, had been turned out at the death of his master, to take his run of the park for the remainder of his life, at ease, with strict injunctions to the servants that he should neither be ridden, nor molested by any one. While musing one day, loitering along, Mr. Burke perceived this worn-out old servant come close up to him, and at length, after some moments spent in viewing his[Pg 152] person, followed by seeming recollection and confidence, he deliberately rested his head upon his bosom. The singularity of the action itself, the remembrance of his dead son, its late master, who occupied so much of his thoughts at all times, and the apparent attachment, tenderness and intelligence of the creature towards him—as if it could sympathize with his inward sorrow—rushing at once into his mind, totally overpowered his firmness, and throwing his arms over its neck, he wept long and loudly.

But though his lucid and beautiful mind, however agonized, remained unclouded to the last, and his affections glowed towards his old friends as warmly as ever, his bodily health was failing fast; one of the last letters he ever dictated was to Mary Leadbeater, the daughter of his old friend and master, Shackleton; this lady was subsequently well known in Ireland as the author of "Cottage Dialogues." The first literary attempt, we believe, made towards the improvement of the lower order of Irish, was by her faithful and earnest pen; to this letter, congratulating her on the birth of a son, is a PS. where the invalid says:—"I have been at Bath these four months to no purpose, and am therefore to be removed to my own house at Beaconsfield to-morrow, to be nearer to a habitation more permanent, humbly and fearfully hoping that my better part may find a better mansion!"

It would seem as if he anticipated the hour of his passing away. He sent sweet messages of loving-kindness to all his friends, entreating and exchanging pardons; recapitulated his motives of action on various political emergencies; gave directions as to his funeral, and then listened with attention to some serious papers of Addison on religious subjects and on the immortality of the soul. His attendants after this were in the act of removing him to his bed, when indistinctly invoking a blessing on all around him, he sunk down and expired on the 9th of July, 1797, in the sixty-eighth year of his age.

"His end," said his friend Doctor Lawrence, "was suited to the simple greatness of mind which he displayed through life; every way unaffected, without levity, without ostentation, full of natural grace and dignity, he appeared neither to wish nor to dread, but patiently and placidly to await the appointed hour of his dissolution."

THE TOMB OF EDMUND BURKE.

THE TOMB OF EDMUND BURKE.

It was almost impossible to people, in fancy, the tattered and neglected churchyard of Beaconsfield as it now is—with those who swelled the funeral pomp of the greatest ornament of the British senate; to imagine the titled pall-bearers, where the swine were tumbling over graves, and rooting at headstones. Seldom, perhaps never, in England, had we seen a churchyard so little cared for as that, where the tomb of Waller[6] renders the surrounding disorder "in a sacred place" more conspicuous by its lofty pretension, and where the church is regarded as the mausoleum of Edmund Burke.[7] Surely the "decency of churchyards" ought to be enforced, if those to whom they should be sacred trusts, neglect or forget their duty. That the churchyard of Beaconsfield, which has long been considered "a shrine," should be suffered to remain in the state in which we saw it, is a disgrace not only to the town, but to England; it was differently cared for during Burke's lifetime, and though, like that of the revered Queen Dowager,[Pg 153] his Will expressed a disinclination to posthumous honors, and unnecessary expense, never were mourners more sincere—never did there arise to the blue vault of heaven the incense of greater, and more deep-felt sorrow, than from the multitude who assembled in and around the church, while the mortal remains of Edmund Burke were placed in the same vault with his son and brother.

The tablet to his memory, placed on the wall of the south aisle of the church, records his last resting-place with the relatives just named; as well as the fact of the same grave containing the body of his "entirely beloved and incomparable wife," who died in 1812, at the age of 76.

Deeply do we deplore that the dwelling where he enjoyed so much that renders life happy, and suffered what sanctifies and prepares us for a better world, exists no longer; but his name is incorporated with our history, and adds another to the list of the great men who have been called into life and received their first and best impressions in Ireland; and if Ireland had given nothing to her more prosperous sister than the extraordinary men of the past and present century, she merits her gratitude for the gifts which bestow so much honor and glory on the United Kingdoms.

Mrs. Burke, previous to her death, sold the mansion to her neighbor, Mr. John Du Pré, of Wilton Park. Mrs. Haviland, Mr. Burke's niece, lived with her to the last, though she did not receive the portion of her fortune to which she was considered entitled. Her son, Thomas Haviland Burke, grand-nephew of Edmund, became the lineal representative of the family; but the library, and all the tokens of respect and admiration which he received from the good, and from the whole world, went with the property to Mrs. Burke's nephew, Mr. Nugent. Some of the sculpture which ornamented the house now graces the British Museum.

The mansion was burnt on the 23d of April, 1813. The ground where it stood is unequal; and some of the park wall remains, and fine old trees still flourish, beneath whose shade we picture the meeting between the mourning father and the favorite horse of his lost son.

There is a full-length portrait of Edmund Burke in the Examination Hall of the Dublin University. All such portraits should be copied, and preserved in our own Houses of Parliament, a meet honor to the dead, and a stimulant to the living to "go and do likewise." It hardly realizes, however, the ideal of Burke; perhaps no portrait could. What Miss Edgeworth called the "ground-plan of the face" is there; but we must imagine the varying expression, the light of the bright quick eyes, the eloquence of the unclosed lips, the storm which could gather thunder-clouds on the well-formed brow; but we have far exceeded our limits without exhausting our subject, and, with Dr. Parr, still would speak of Burke:

"Of Burke, by whose sweetness Athens herself would have been soothed, with whose amplitude and exuberance she would have been enraptured and on whose lips that prolific mother of genius and science would have adored, confessed—the Goddess of Persuasion."

Alas! we have lingered long at his shrine, and yet our praise is not half spoken.

—[The notes and drawings for this paper were contributed by F. W. Fairhold, of the Society of Antiquaries.]

[1] Sylvanus Spenser, the eldest son of the Poet Spenser, married Ellen Nagle, eldest daughter of David Nagle, Esq., ancestor of the lady, who was mother to Edmund Burke.

[2] This as a picture is outlined with so delicate a pencil, and colored with such mingled purity and richness of tone, that we transcribe a few passages, as much in honor of the man who could write, as the woman who could inspire such praise:—

"The character of ——

"She is handsome, but it is beauty not arising from features, from complexion, or from shape. She has all three in a high degree, but it is not by these she touches a heart; it is all that sweetness of temper, benevolence, innocence, and sensibility, which a face can express, that forms her beauty. She has a face that just raises your attention at first sight; it grows on you every moment, and you wonder it did no more than raise your attention at first.

"Her eyes have a mild light, but they awe when she pleases; they command like a good man out of office, not by authority, but by virtue.

"Her stature is not tall, she is not made to be the admiration of every body, but the happiness of one.

"She has all the firmness that does not exclude delicacy—she has all the softness that does not imply weakness. * *

"Her voice is a soft, low, music, not formed to rule in public assemblies, but to charm those who can distinguish a company from a crowd: it has this advantage—you must come close to her to hear it.

"To describe her body, describes her mind; one is the transcript of the other; her understanding is not shown in the variety of matters it exerts itself on, but in the goodness of the choice she makes.

"She does not display it so much in saying or doing striking things, as in avoiding such as she ought not to say or do."

"No persons of so few years can know the world better; no person was ever less corrupted by the knowledge.

"Her politeness flows rather from a natural disposition to oblige, than from any rules on that subject, and therefore never fails to strike those who understand good breeding, and those who do not."

"She has a steady and firm mind, which takes no more from the solidity of the female character, than the solidity of marble does from its polish and lustre. She has such virtues as make us value the truly great of our own sex. She has all the winning graces that make us love even the faults we see in the weak and beautiful in hers."

[3] Our cut exhibits all that now remains of Gregories—a few walls and a portion of the old stables. Mrs. Burke, before her death, sold the mansion to her neighbor, Mr. John Du Pré, of Wilton Park. It was destroyed by fire soon afterwards.

[4] During Barry's five years' residence abroad he earned nothing for himself, and received no supplies save from Edmund and Richard Burke.

[5] Mr. Prior says in his admirable Life of Burke—"How the money to effect this purchase was procured has given rise to many surmises and reports; a considerable portion was his own, the bequest of his father and elder brother. The Marquis of Rockingham offered the loan of the amount required to complete the purchase; the Marquis was under obligations to him publicly, and privately for some attention paid to the business of his large estates in Ireland. Less disinterested men would have settled the matter otherwise—the one by quartering his friend, the other, by being quartered, on the public purse. To the honor of both, a different course was pursued."

[6] Waller was a resident in this vicinity, in which his landed property chiefly lay. He lived in the family mansion named Well's Court, a property still in the possession of his descendants. His tomb is a table monument of white marble, upon which rises a pyramid, resting on skulls with bat's wings; it is a peculiar but picturesque addition to the churchyard, and, from its situation close to the walk, attracts much attention.

[7] Our engraving exhibits his simple tablet, as seen from the central aisle of the church, immediately in front of the pew in which Burke and his family always sat.

For the last twenty years the name of Mr. Goodrich has been very constantly associated with American literature. He commenced as a publisher, in Boston, and was among the first to encourage by liberal copyrights, and to make attractive by elegant editions, the works of American authors. One of his earliest undertakings was a collection of the novels of Charles Brockden Brown, with a memoir of that author, by his widow, with whom he shared the profits. In 1828 he began "The Token," an annual literary souvenir, which he edited and published fourteen years. In this appeared the first fruits of the genius of Cheney, who has long been acknowledged the master of American engravers; and the first poems and prose writings of Longfellow, Willis, Mellen, Mrs. Osgood, Mrs. Child, Mrs. Sigourney, and other eminent authors. In "The Token" also were printed his own earlier lyrical pieces. The work was of the first rank in its class, and in England as well as in this country it was uniformly praised.

In 1831 an anonymous romance was published by Marsh & Capen, of Boston. It was attributed by some to Willis, and by others to Mrs. Child, then Miss Francis. It illustrated a fine and peculiar genius, but was soon forgotten. Mr. Goodrich appreciated its merits, and applied to the publishers for the name of the author, that he might engage him as a contributor to "The Token." They declined to disclose his secret, but offered to forward a letter to him. Mr. Goodrich wrote one, and received an answer signed by Nathaniel Hawthorne, many of whose best productions, as "Sights from a Steeple," "Sketches under an Umbrella," "The Prophetic Pictures," "Canterbury Pilgrims," &c., appeared in this annual. In 1839, Mr. Goodrich suggested to Mr. Hawthorne the publication of a collection of his tales, surrendering his copyrights to several of them for this purpose; but so little were the extraordinary qualities of this admirable author then understood, that the publishers would not venture upon such an experiment without an assurance against loss, which Mr. Goodrich, as his friend, therefore gave. The public judgment will be entitled to little respect, if the copyright of the works of Hawthorne be not hereafter a most ample fortune.

Mr. Goodrich soon abandoned the business of publishing, and, though still editing "The Token," devoted his attention chiefly to the writing of that series of educational works, known as Peter Parley's, which has spread his fame over the world. The whole number of these volumes is about sixty. Among them are treatises upon a great variety of subjects, and they are remarkable for simplicity of style and felicity of illustration. Mr. Goodrich has accomplished a complete and important revolution in juvenile reading, substituting truth and nature for grotesque fiction in the materials[Pg 154] and processes of instruction, and his method has been largely imitated, at home and abroad. In England many authors and publishers have disgraced the literary profession by works under the name of "Parley," with which he has had nothing to do, and which have none of his wise and genial spirit.

Besides his writings under this pseudonym, Mr. Goodrich has produced several works of a more ambitious character, which have been eminently popular. Among them is a series entitled "The Cabinet Library," embracing histories, biographies, and essays in science; "Universal Geography," in an octavo volume of one thousand pages; and a "History of all Nations," in two large octavos, in which he has displayed such research, analysis, and generalization, as should insure for him an honorable rank among historians. We cannot better illustrate his popularity than by stating the fact, that more than four hundred thousand volumes of his various productions are now annually sold in this country and Europe. No living writer is, therefore, as much read, and in the United States hardly a citizen now makes his first appearance at the polls, or a bride at the altar, to whose education he has not in a large degree contributed. For twenty years he has preserved the confidence of parents and teachers of every variety of condition and opinion, by the indefectible morality and strong practical sense, which are universally understood and approved.

Like many other eminent persons, Mr. Goodrich lets sought occasional relaxation from the main pursuits of his life in poetry, and the volume before us contains some forty illustrations of his abilities, as a worshipper of the muse whose temples are most thronged, but who is most coy and most chary of her inspiration. They have for the most part been previously printed in "The Token," or in literary journals, but a few are now published the first time. In typographical and pictorial elegance the book is unique. It is an exhibition of the success of the first attempt to rival the London and Paris publishers in woodcut embellishment and general beauty of execution.

That Mr. Goodrich possesses the poetical faculty in an eminent degree, no one has doubted who has read his fine lines "To Lake Superior:"

The "Birth Night of the Humming Birds" has been declared by the London Athenæum equal to Dr. Drake's "Culprit Fay," and it may be regarded as in its way the best specimen of Mr. Goodrich's talents. It is too long to be quoted in these paragraphs. In descriptions of nature he is uniformly successful, presenting his picture with force and distractness.[Pg 155]

There are many examples of this in one of his longest poems, "The Mississippi," in which the traditions that cluster around the Father of Waters, and the advances of civility along his borders, are graphically presented. The river is described as rising.

The bard laments that

Yet trusts that in a future time,

In the volume are several allegorical pieces of much merit, of which the most noticeable are the "Two Windmills," "The Bubble Chase," and "The Rainbow Bridge." Several smaller poems are distinguished for a quaint simplicity, reminding us of the old masters of English verse; and others, for refined sentiment, as the "Old Oak," of which the key-note is in the lines,

The longest of Mr. Goodrich's poems is "The Outcast." It was first published many years ago, and it appears now with the improvements suggested by reflection and criticism. Its fault is, a certain intensity, but it has noble passages, betraying a careful study and profound appreciation of the subtler operations of the mind, particularly, when, in its most excited action, it is influenced by the observation of nature.

The volume will take its place in the cabinets of our choice literature, and will be prized the more for the fact that by selecting American themes for his most elaborate compositions, Mr. Goodrich has made literature subservient to the purposes of patriotism.

[8] Poems: by S. G. Goodrich. New York, G. P. Putnam. [The designs—about forty—are by Mr. Billings, the engravings by Bobbett & Edmonds, Lossing & Barrett, Hartwell, and others, and the printing by Mr. John F. Trow.]

The author of "St. Leger" was by that admirable work placed in the leading rank of the new generation of American writers. The appearance in the Knickerbocker for the present month, of the commencement of a sequel to "St. Leger," makes it a fit occasion for some notice of his life and genius.

Mr. Kimball is by inheritance of the first class of New-England men, numbering in his family a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a President of the Continental Congress, and several other persons honorably distinguished in affairs. He is a native of Lebanon, in New Hampshire, where his father is still living—the centre of a circle bound to him by their respect for every public and private virtue. Though he had completed his preparatory studies before he was eleven years of age, he did not enter college until he was nearly thirteen. Four years after, in 1834, he graduated at Dartmouth, and upon devoting one year to the study of the law, he went abroad; travelled in England, Scotland, and Germany; and resided some time in Paris, where he attended the lectures of Majendie, Broussais, and Louis, in medicine, and those of the elder Dupin, and Coulanges, in law. Returning, he entered upon the practice of the law, at Waterford, in this state, but soon removed to New-York, where a year's devotion to his profession made him familiar with its routine. In 1842 he went a second time to Europe, renewing the associations of his travel and student-life in Great Britain and on the continent. Since, for seven years, he has been an industrious and successful lawyer in New-York.

Although but few works are known to be from the pen of Mr. Kimball, he has been a voluminous author. The vigorous and polished style of his avowed compositions, is never attained but by long practice. He has been, we believe, a contributor to every volume of the Knickerbocker published since 1842. He printed in that excellent magazine his "Reminiscences of an Old Man," "The Young Englishman," and the successive chapters of "St. Leger, or the Threads of Life." This last work was published by Putnam, and by Bentley in London, about one year ago, and it passed rapidly through two English and three American editions. It was not raised into an ephemeral popularity, as so many works of fiction easily are, for their lightness, by careless applauses; it arrested the attention of the wisest critics; commanded their study, and received their verdict of approval as a book of learning and reflection in the anatomy of human life.

Mr. Kimball had been eminent in his class at college for a love of Greek literature, and he studied the Roman also with reverent attention. It was his distinction that he had thoroughly acquainted himself with the philosophy of the ancients. At a later day he was attracted by the speculation of the Germans, and a mastery of their language enabled him to enter fully into the spirit of Spinosa, Kant,[Pg 157] and Fichte, as he did into that of the finer intelligences, Göethe and Richter, and pervading he found the passion to know Whence are we? What are we? Whither do we go? In "St. Leger," a mind predisposed to superstition by some vague prophecies respecting the destiny of his family—a mind inquisitive, quick, and earnest, but subject to occasional melancholy, as the inherited spell obtains a mastery of the reason—is exposed to the influences of a various study, and startling experiences, all conceived with a profound knowledge of human nature, and displayed with consummate art; having a metaphysical if not a strictly dramatic unity; and conducting by the subtlest processes, to the determination of these questions, and the flowering of a high and genial character; as Professor Tayler Lewis expresses it, "at rest, deriving substantial enjoyment from the present, because satisfied with respect to the ultimate, and perfect, and absolute."[9]

Aside from its qualities as a delineation of a deep inner experience, "St. Leger" has very great merits as a specimen of popular romantic fiction. The varied characters are admirably drawn, and are individual, distinct, and effectively contrasted. The incidents are all shaped and combined with remarkable skill; and, as the Athenaeum observes, "Here, there, everywhere, the author gives evidence of passionate and romantic power." In some of the episodes, as in that of Wolfgang Hegewisch, for example, in which are illustrated the tendency of a desperate philosophy and hopeless skepticism, we have that sort of mastery of the feelings, that chaining of the intensest interest, which distinguishes the most wonderful compositions of Poe, or the German Hoffman, or Zschokke in his "Walpurgis Night;" and every incident in the book tends with directest certainty to the fulfilment of its main design.

The only other work of which Mr. Kimball is the acknowledged author, is "Cuba and the Cubans;" a volume illustrative of the history, and social, political, and economical condition of the island of Cuba, written during the excitement occasioned by its invasion from the United States, in 1849, and exhibiting a degree of research, and a judicial fairness of statement and argument, which characterizes no other production upon this subject. As it was generally admitted to be the most reliable, complete, and altogether important work, upon points commanding the attention of several nations, its circulation was very large; but it was produced for a temporary purpose, and it will be recalled to popularity only by a renewal of the inevitable controversies which await the political relations of the Antilles.

"A Story of Calais," in the following pages, is an example of Mr. Kimball's success as a tale writer. Though less remarkable than passages in "St. Leger," it will vindicate his right to a place among the chief creators of such literature among us.

[9] The Inner-Life, a Review of St. Leger, by Professor Tayler Lewis, LL. D., &c.

Among the distinguished strangers who visited the United States during the last season, no one has left a more favorable impression upon American society than the thoroughly accomplished scholar and highbred gentleman, the Bishop of Jamaica. We propose a brief sketch of his history:

Aubrey George Spencer, D.D. and D.C.L., was born in London on the 12th of February, 1795, and is the eldest son of the late Hon. William Spencer, the poet, whose father, Lord Charles Spencer, was a son of Charles the second Duke of Marlborough, and grandson of John Churchill, the illustrious hero of Ramillies and Blenheim. His Christian names were given by the Dukes of St. Albans and Marlborough, who were his great uncles and godfathers. His mother was Susan Jennison, a countess of the Holy Roman Empire, and a lady of singular beauty and accomplishments, to whom Mr. William Spencer was married at the court of Hesse Darmstadt, in 1791. Aubrey Spencer and his younger brother George (subsequently Bishop of Madras,) received the rudiments of learning at the Abbey School of St. Albans, whence the former was soon removed to the seminary of the celebrated Grecian, D. Burme, of Greenwich, and the latter to the Charter house. For some time previous to his matriculation at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, Mr. Aubrey Spencer was the private pupil of Mr. Mitchell, the very learned translator of Aristophanes. At the house of his father in Curzon street, at Melbourne House in Chiswick, Blenheim, and Woolbeednig, Hallowell Hill, (the seat of the Countess Dowager Spencer,) he was in frequent and familiar intercourse with many of the most distinguished contemporary statesmen, philosophers, and other men of letters; and in this society his own literary and conversational talents obtained an early celebrity, and commended him to the regard and friendship of Mr. Rogers, Mr. Campbell, Lord Byron, Mr. Hallam, Lord Dudley, Mr. Coutts, Mr. Wordsworth, Mr. Francis, Mr. Homer, Thomas Moore, Mr. Southey, Lady Caroline Lamb, Mr. Crabb, and many other authors, with some of whom he still maintains a correspondence, while some have fallen asleep.

With the society of the county of Oxford, and with that of the University, he was equally popular. In the early part of the year 1818, he took leave of his College, on being ordained deacon, and entered on a charge of the parish of Great Oakering, in the diocese of London. From this, which is a very unhealthy part of Essex, he removed at the end of the year to Bannam, Norfolk, where he became the neighbor and frequent guest of the Earl of Albemarle and the Bishop of Norwich. In March, 1819, he was admitted a priest, and soon after gave up the brilliant society in which he had hitherto lived, and devoted himself to the Church in the Colonies, where, for a quarter of a century, he has filled a distinguished part as archdeacon and bishop.[Pg 158]

His first visit to the Bermudas was undertaken for the recovery of his health, to which a colder climate has always been hostile; and when, in the year 1825, these islands were attached to the diocese of Nova Scotia, he was, at the instance of the late Primate, appointed to them as Archdeacon and Ecclesiastical Commissary to the Bishop of the see. Here he may be said to have created the Ecclesiastical Establishment which, under his conciliatory influence, has so rapidly and largely increased; and with it he soon associated the revival of Bishop Berkeley's Classical Academy, and a system of general instruction, of which a chain of schoolhouses, from either extremity of the island, are the abiding monuments.

From his connection with the Bishop of Nova Scotia, the visits of Archdeacon Spencer to that colony were frequent, and many of the inhabitants both of that province and of New Brunswick retain a lively impression of his abilities, as they were illustrated in his preaching and in the practice of the other duties of his profession and position.

In July, 1839, Dr. Spencer was consecrated by the venerable Archbishop of Canterbury, on the nomination of the crown, to the new see of Newfoundland, retaining still episcopal jurisdiction over the isles of Bermuda, under the extension of the Colonial Episcopate, which relieved the indefatigable Bishop of Nova Scotia of a large portion of his cares. The new Bishop was enabled, by the aid of the Society for the Promotion of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, to quadruple the number of his clergy within four years, and to consecrate more than twenty additional churches within the same period. A very grateful sense of the Bishop's exertions, and of the prosperous results of his unceasing labor, was manifested in the several addresses presented to his lordship on his subsequent translation to the diocese of Jamaica, by the clergy and laity of Newfoundland and Bermuda.

In a paper which only purports to be a biographical notice of one who is still living, it is not desirable to do more than briefly advert to the principal topics and dates of a history which may hereafter be advantageously amplified and filled up. The real progress of the established church in Newfoundland at this period, would be best gathered from the Bishop's letters to the government and the religious societies, and to the clergy under his jurisdiction, but to these documents it is not likely that any biographer will have unreserved access during the life of his lordship.

On the decease of Bishop Lipscombe, in April, 1843, Bishop Spencer was translated, under circumstances peculiarly indicative of the high opinion which was had of his ability by the Queen's ministers and the heads of the English church, to the see of Jamaica, one of the most important connected with the crown. He quitted his old diocese, as the papers of the day amply testify, with the respect of all denominations of Christians. A national ship, the Hermes, was appointed to convey him and his family and suite to Jamaica, where he arrived in the first week of November, having made the land on the auspicious festival of All Saints.

The sermon delivered by him at his installation, in the cathedral at Spanish Town, was published at the request of the Speaker of the House of Assembly, while the Earl of Elgin, the Governor-General, in his speech to the Legislature, "congratulated the inhabitants of Jamaica on the appointment of a prelate of such approved talents and piety to that see." At every point of the Bishop's visitation, which he commenced by a convention of eighty clergymen, at Spanish Town, he was met by congratulatory addresses from the vestries, and other corporate bodies, declaratory of their confidence in his projected measures, and of their desire to aid him in the extension of the church. In consonance with his views the local Legislature passed an act increasing the number of island curates, and providing higher salaries for their support, while at the same time, they granted three thousand pounds as a first instalment to the Church Society, which had been organized by him, and to which the Governor-General contributed the annual sum of one hundred pounds.

On his visit to England in 1845 and in the beginning of 1846, he was continually employed in preaching in aid of various charities, and in assisting at public meetings which had for their object the promotion of Christianity by the servants of the church. At the weekly meetings of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, in London, he was a constant attendant; and the increase of the funds of that association, and the conciliation to it of many powerful supporters, are result of measures which may be traced to his projection and tact. In his reply to an address from the clergy, on his return from a recent visitation, published at length in the last annual report of the parent Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, will be found the clearest exposition of the existing state and future prospects of the church in Jamaica; and a charge addressed by his lordship to the clergy of the Bahamas, on the subject of a difficult and embarrassing question, for the adjustment of which the Bishop received the thanks of the Queen's government and of the local Executive, is full of valuable information on the condition, principles and progress of the colonial establishment. In closing the last session of the Bahamas Legislature, Governor Gregory declared in his speech, with reference to this matter, that he considered the arrival of the Bishop in the island, at that juncture, as a convincing proof of the interposition of a special Providence in the conduct of human affairs.

In 1822, the Bishop was married to Eliza, the daughter of John Musson, Esq., and the sister of a former friend at the University. He has had one son, now deceased, and has three daughters.[Pg 159]

As a man of letters, Bishop Spencer is entitled to a very honorable position. As a scholar and as a critic, he has evinced such abilities as, fitly devoted, would have secured fame; as a poet and essayist, he has unusual grace and elegance; and a collection of the various compositions with which he has relieved the monotony and arduous labors of his professional and official career, would vindicate his title to be classed with those prelates who have been most eminent in the literary world.

The following poems, from autographs of Bishop Spencer, we believe are first given to the public in the International.

In the concluding volume of the Life of Southey, just published by the Harpers, is a letter from the poet in answer to one by Lord Brougham, on the subject of the encouragement of literature by government. "Your first question," writes Southey, "is, whether Letters would gain by the more avowed and active encouragement of the Government?

"There are literary works of national importance which can only be performed by co-operative labor, and will never be undertaken by that spirit of trade which at present preponderates in literature. The formation of an English Etymological Dictionary is one of those works; others might be mentioned; and in this way literature might gain much by receiving national encouragement; but Government would gain a great deal more by bestowing it. Revolutionary governments understand this: I should be glad if I could believe that our legitimate one would learn it before it is too late. I am addressing one who is a statesman as well as a man of letters, and who is well aware that the time is come in which governments can no more stand without pens to support them than without bayonets. They must soon know, if they do not already know it, that the volunteers as well as the mercenaries of both professions, who are not already enlisted in this service, will enlist themselves against it; and I am afraid they have a better hold upon the soldier than upon the penman; because the former has, in the spirit of his profession and in the sense of military honor, something which not unfrequently supplies the want of any higher principle; and I know not that any substitute is to be found among the gentlemen of the press.

"But neediness, my Lord, makes men dangerous members of society, quite as often as affluence makes them worthless ones. I am of opinion that many persons who become bad subjects because they are necessitous, because 'the world is not their friend, nor the world's law,' might be kept virtuous (or, at least, withheld from mischief) by being made happy, by early encouragement, by holding out to them a reasonable hope of obtaining, in good time, an honorable station and a competent income, as the reward of literary pursuits, when followed with ability and diligence, and recommended by good conduct.

"My Lord, you are now on the Conservative side. Minor differences of opinion are infinitely insignificant at this time, when in truth there are but two parties in this kingdom—the Revolutionists and the Loyalists; those who would destroy the constitution, and those who would defend it, I can have no predilections for the present administration; they have raised the devil who is now raging through the land: but, in their present position, it is their business to lay him if they can; and so far as their measures may be directed to that end, I heartily say, God speed them! If schemes like yours for the encouragement of letters, have never entered into their wishes, there can be no place for them at present in their intentions. Government can have no leisure now for attending to any thing but its own and our preservation; and the time seems not far distant when the cares of war and expenditure will come upon it once more with their all-engrossing importance. But when better times shall arrive (whoever may live to see them), it will be worthy the consideration of any government whether the institution of an Academy, with salaries for its members (in the nature of literary or lay benefices), might not be the means of retaining in its interests, as connected with their own, a certain number of influential men of letters, who should hold those benefices, and a much greater number of aspirants who would look to them in their turn. A yearly grant of ten thousand pounds would endow ten such appointments of five hundred pounds each for the elder class, and twenty-five of two hundred pounds each for younger men; the latter eligible, of course, and preferably, but not necessarily, to be elected to the higher benefices, as those fell vacant, and as they should have improved themselves.

"The good proposed by this, as a political measure, is not that of retaining such persons to act as pamphleteers and journalists, but that of preventing them from becoming such, in hostility to the established order of things; and of giving men of letters, as a class, something to look for beyond the precarious gains of literature; thereby inducing in them a desire to support the existing institutions of their country, on the stability of which their own welfare would depend.

"Your Lordship's second question,—in what way the encouragement of Government could most safely and beneficially be given,—is, in the main, answered by what has been said upon the first. I do not enter into any details of the proposed institution, for that would be to think of fitting up a castle in the air. Nor is it worth while to examine how far such an institution might be perverted. Abuses there would be, as in the disposal of all preferments, civil, military, or ecclesiastical; but there would be a more obvious check upon them; and where they occurred they would be less injurious in their consequences than they are in the state, the army and navy, or the church.

"With regard to prizes, methinks they are better left to schools and colleges. Honors are worth something to scientific men, because they are conferred upon such men in other countries; at home there are precedents for them in Newton and Davy, and the physicians and surgeons have them. In my judgment, men of letters are better without them, unless they are rich enough to bequeath to their family a good estate with the bloody hand, and sufficiently men of the world to think such distinctions appropriate. For myself, if we had a Guelphic order, I should choose to remain a Ghibelline.[Pg 161]

"I have written thus fully and frankly, not dreaming that your proposal is likely to be matured and carried into effect, but in the spirit of good will, and as addressing one by whom there is no danger that I can be misunderstood. One thing alone I ask from the legislature, and in the name of justice,—that the injurious law of copyright should be repealed, and that the family of an author should not be deprived of their just and natural rights in his works when his permanent reputation is established. This I ask with the earnestness of a man who is conscious that he has labored for posterity."

The publication of this letter, and of the correspondence between Southey and Sir Robert Peel, in which the poet declines being knighted, on account of his poverty—a correspondence eminently honorable to the late Prime Minister, has occasioned an eloquent letter from Walter Savage Landor to Lord Brougham on the same subject.

The Edinburgh Review rebukes the daring of those uneducated story-tellers who profane by their intrusion the holy lands, the sacred names, and golden ages of art. We have acceptable specimens of the "classical novel" by Dr. Croly, Lockhart, Bulwer, and Collins (the author of "Antonini"), and in this country by Mrs. Child and William Ware; but nineteen of every twenty who have attempted such compositions have failed entirely. The Edinburgh Reviewer, after showing that the writers whom he arraigns have merely parodied the exterior life of our own time, proceeds—