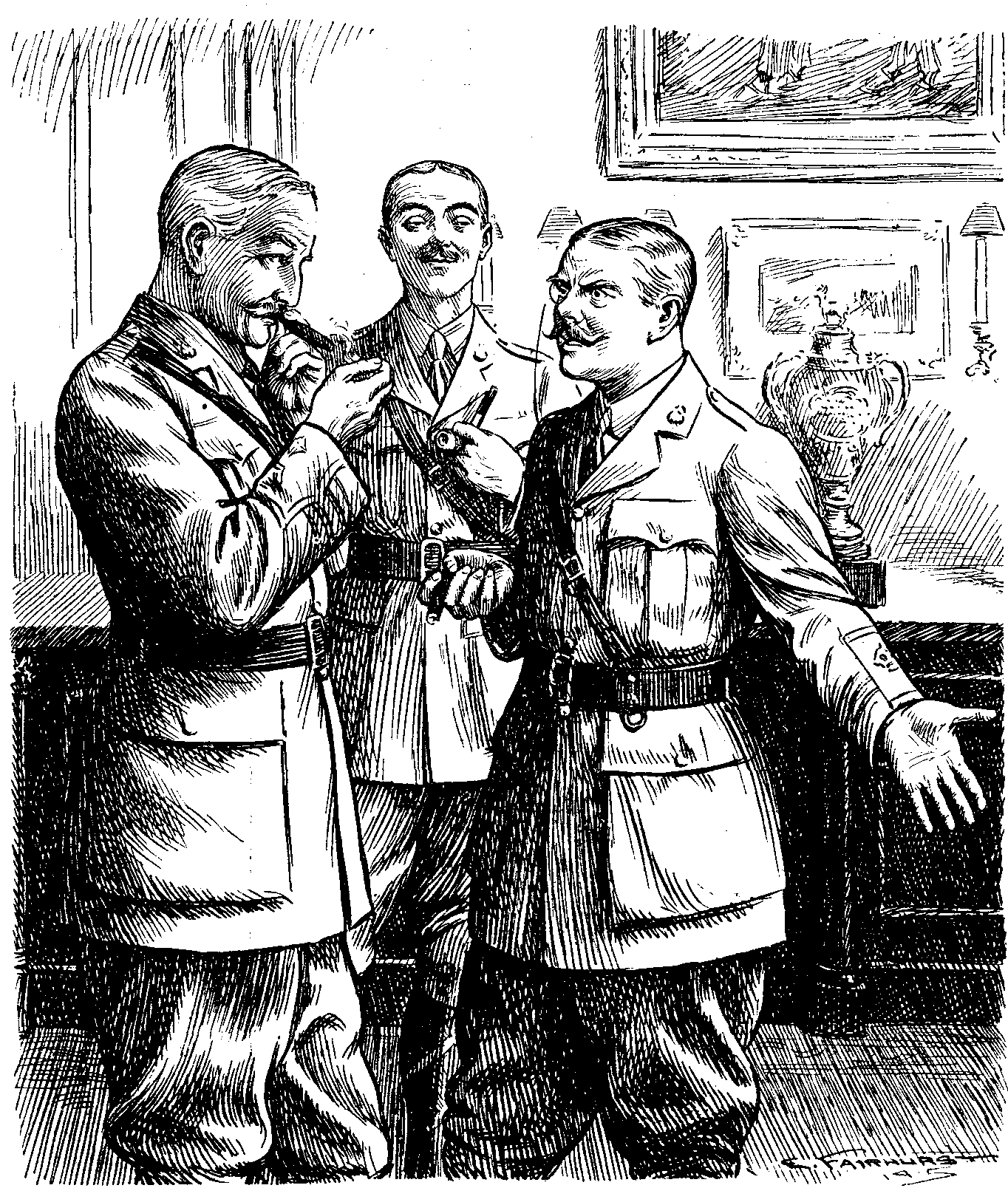

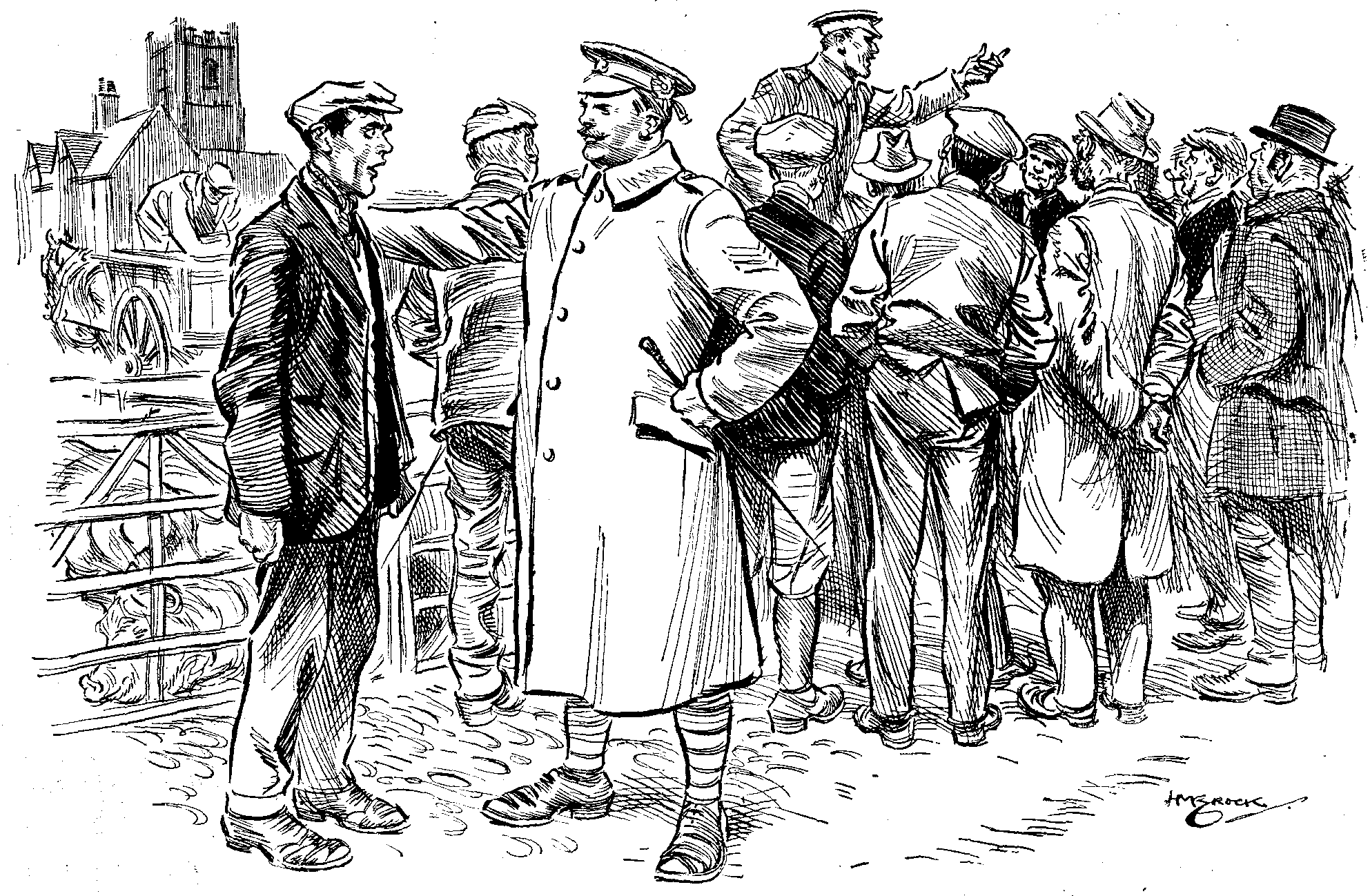

Fiery Major (discussing delinquent Subaltern). "But there—what can you expect? He's only one of those temporary blighters!"

Colonel (sweetly). "But isn't that better than being a permanent blighter?"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 150, January 12, 1916, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 150, January 12, 1916 Author: Various Editor: Owen Seaman Release Date: September 19, 2007 [EBook #22672] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David King, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

There is much satisfaction in the German Army at the announcement that iron coins to the value of ten million marks are to be substituted for nickel and copper. It is now hoped that those Crosses may yet prove to be worth something.

A resident of Honor Oak writes to the papers to say that such was the patriotic anxiety of people in his neighbourhood to pay their taxes at the earliest possible moment that he found a long queue before the collector's door on January 3rd and had to wait an hour before his turn came. On reading his letter several West-end theatres patriotically offered the collector the loan of their "House Full" boards.

Prince William of Wied, the ex-ruler of Albania, is at present in Serbia, feverishly awaiting restoration to his former dignity. The situation is not very favourable, however, and his German advisers have warned him to curb his Mpretuosity.

An American barque with a cargo of beans for Germany has been seized and unloaded by the Swedish authorities. A cruel fate seems to overtake every effort of the United States to give Germany these necessary commodities.

Among the suspicious articles discovered at the Bulgarian Consulate in Salonika was a large stock of red brassards. But the inference that they belonged to members of the British V.T.C., who were determined to fight for the enemy rather than not fight at all, is certainly premature.

Several inmates of the Swansea workhouse, having been told that margarine was to be served out instead of butter, returned their portions, only to discover that it was butter after all. As similar incidents have occurred in many other establishments it is suggested that margarine should in future be dyed scarlet or blue in order to prevent a repetition of these embarrassing contretemps.

Sir John Simon, in the debate on the Compulsion Bill, said that the alleged 650,000 slackers were arrived at "by subtracting two figures from one another." Everyone must agree with him that if that was the method employed the result would be "negligible."

In a tram-car in a Northern city, as the girl-conductor went round for fares, a "nut" tried to take a rise out of her by asking for a ticket to "Gallipoli." She charged him for the full length of the tram journey, and as soon as the tram arrived at a recruiting office she rang the bell and said, "You change here, Sir, for Gallipoli."

The Kaiser thinks it very mean of the British Government to turn his Corfu palace into a hospital. His submarine commanders are now wondering how to shell the inmates without damaging their master's property.

The Militant Suffragette who some years ago damaged the Velasquez Venus with an axe has just published a novel, of which the hero is a plumber who thought he was a poet. It ought to be called "The Burst Pipe," but isn't.

Women are now employed on some of the railways in the North. A traveller recently had two Tommies for fellow-passengers. They related that they had every week to take a long slow duty journey which was "the limit"; but lately it had taken on a different aspect, for "now," said Tommy, "when you get too bored you just hop out and kiss the porter."

Extract from a letter written to a loved one from the Front:—

"I received your dear little note in a sandbag. You say that you hope the sandbag stops a bullet. Well, to tell the truth, I hope it don't, as I have been patching my trousers with it."

Prince von Buelow, who has been for some time in Switzerland, has obtained an increase in the number of his secretaries, of whom he now has a round dozen. Several of the poor fellows are suffering from writer's cramp through having to pen so many letters explaining that the Prince is at Lucerne purely for the sake of his health.

Fiery Major (discussing delinquent Subaltern). "But there—what can you expect? He's only one of those temporary blighters!"

Colonel (sweetly). "But isn't that better than being a permanent blighter?"

["This Bill was 'selling the pass.'"—Sir William Byles, in the House, on The Military Service Bill.]

"What though against our sacred front

They muster, miles on miles,

I am resolved to stick the brunt,"

Said bold Horatius Byles;

"For Liberty I'll take my stand,

Just like a stout Berserk,

And still defend with bloody brand

Our glorious Right to Shirk.

"We've Simon, worth four columns' length;

We've Redmond, doughty dog;

Thomas and those twin towers of strength,

Pringle and whole-souled Hogge;

And Outhwaite—not our dearest foe,

Bulgar or Bosch or Turk,

Could wish to plant a ruder blow

For Britain's Right to Shirk.

"And, lastly, should the Tyrant storm

The pass for which we fight,

It must be o'er the riddled form

Of Me, the Champion Knight;

Meanwhile, on caitiffs who would keep

The pledge we bade them burke,

My lusty battle-cry shall leap:—

'God and our Right to Shirk!'"

The scrap was over. There he lay

Prone on the reeking grass;

"Simon," his faint lips strove to say,

"Somebody's sold the pass!"

"True," said the other; "I descry

The Northcliffe's hand at work."

"Farewell!" said Byles; "'tis sweet to die

For Britain's Right to Shirk!"

O.S.

What it has done in 1915.

(With acknowledgments to Mr. Archibald Hurd in "The Daily Telegraph.")

Superiority, and again Superiority! In this one word lies the secret of our success at sea. Yet it would be hard to say how many careless civilians there are, taking all things for granted, who fail to recognise that fact even now. Not numbers nor organisation, nor men nor guns nor ships—though these have counted for something—have been responsible for our victory. It has been due above all to superiority—sheer superiority.

Think what would have happened if there had been any strategic fumbling at the opening of the War! It is not pleasant to reflect upon what might have occurred (had not superiority stepped in) at the very outset if, for instance, we had sent several Dreadnoughts to catch the Emden. It was strongly suspected, mind you, that there were German armed vessels on the trade routes. As one merchantman after another was sunk there could no longer be any doubt about it. What if, in panic, we had suddenly dispersed our naval force to every part of the globe? What then? But we didn't. What again if it had been determined, in accordance with some fanciful scheme, to concentrate our main striking force in the Mersey? Germany well might have captured the initiative. But authority was not distracted from its primary purpose. Was its policy a success? Come, now, was it?

The old year has gone. On January 4th the British Fleet had been at war seventeen months—roughly seventy-four weeks (anyone can count them up; there is nothing abstruse about my statistics). In a word, it might almost be said, with some approach to accuracy, that it has been in the throes of the struggle for a year and a half. Very well.

The German Flag has been banished from the ocean. Not since the War began has a German battleship steamed down the Channel—nor a battle cruiser, nor yet an armoured cruiser, nor even a light cruiser, nor a monitor, nor a destroyer. None of them—not one. Why is that? Because (vide supra) the German Fleet has been banished from the ocean. It still exists, but it is safely locked up behind explosive agents (mines) and protected by submersive factors (submarines). The German Fleet is in a zareba.

Let us recall the striking words of one of Germany's leading naval strategists, written, mark you, before the War: "England's strength is mainly in her Fleet." I wonder now if that is generally known.

He goes on to define the duties of a fleet in the following words:—

Has the British Fleet succeeded?

The German Flag is banished from the seas. In January 1916 the German Fleet is still lurking in that zareba. The Dreadnought embodied an offensive in excelsis, even as the expansion of the Dreadnought policy embodies an offensive in extenso and imposes upon the enemy a defensive in extremis.

It is perhaps hardly realised that the performance of the British Navy in this War has no parallel in history. In the past, enemy frigates always succeeded in getting out of ports, however close the blockade. But none has broken through this time—not a single frigate. On the other hand enemy submarines may be said to have been more formidable than in the Napoleonic wars.

But the German Fleet is strong. I am not one of the sort of humourists who hold it up to contempt in its inactivity. For that matter I am not any sort of humourist. Perhaps you have found that out. But the German High Seas Fleet is no fit subject for joke. That it has proved harmless is due to one thing alone—superiority.

And so the War wags. All over the high seas our merchantmen continue to inscribe their indelible furrows.

And where is the German Fleet? I think I have answered that.

Here then I conclude my synopsis of the work of the Fleet in 1915. And if it be said that it might well have stood almost word for word as the record of the work of the Fleet in 1914, I may reply that I sometimes wistfully wonder if I shall have to make any alterations in the text before it goes to press again this time next year.

Bis.

"Handsomely carved early Victorian sideboard, been in one family for a century."—Advt. in "Horncastle News."

From Mr. Bonar Law's speech as reported by a morning paper:—

"We were quite ready to carry on the principle of keeping a united nation by keeping in opposition and not facetiously opposing the Government."

Unlike those eminent humourists, Messrs. Hogge, Pringle, and King.

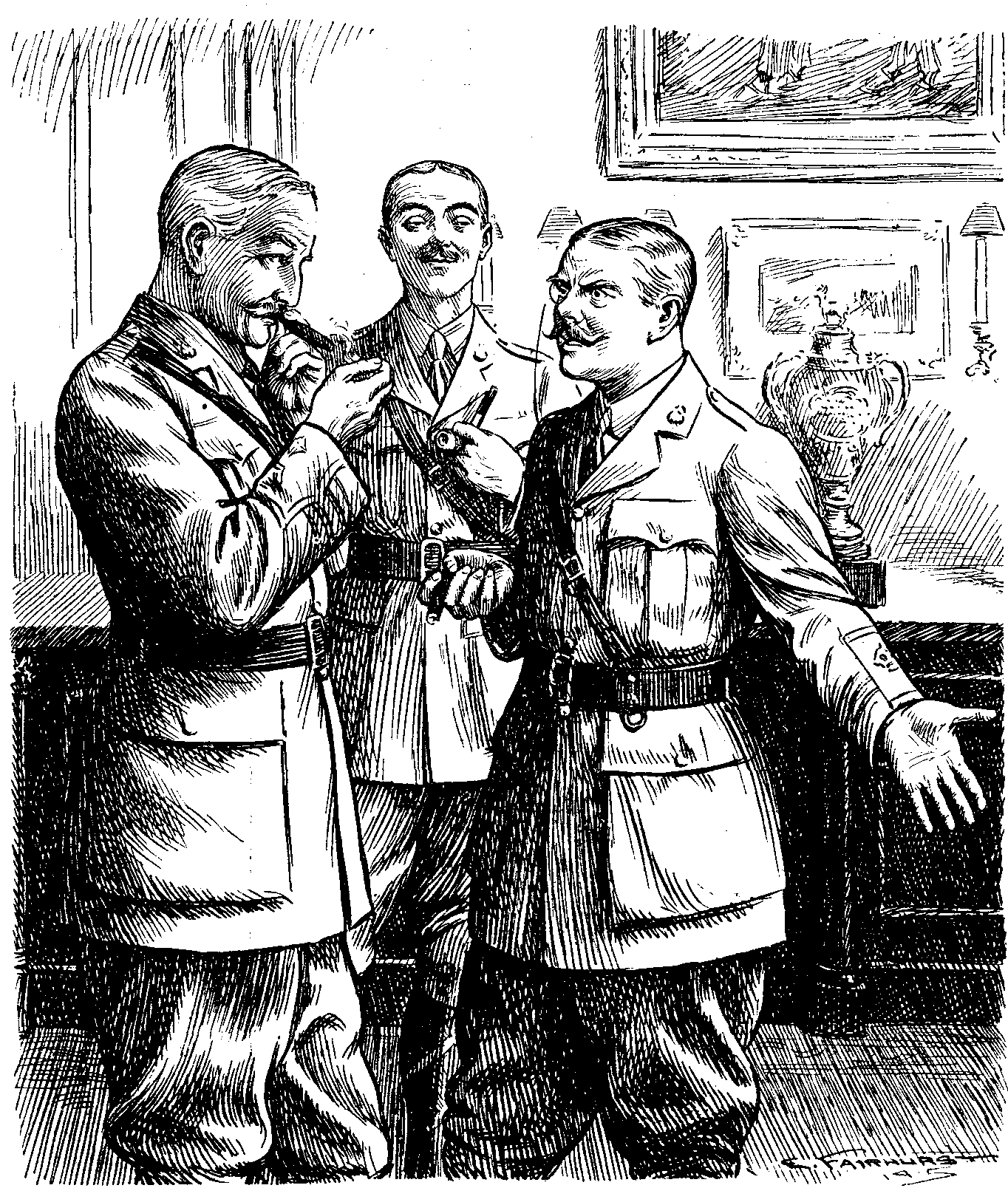

Bosch (with visions of the conquest of Egypt). "I SUPPOSE HE KNOWS THE WAY THERE." Camel (overhearing). "AND BACK!"

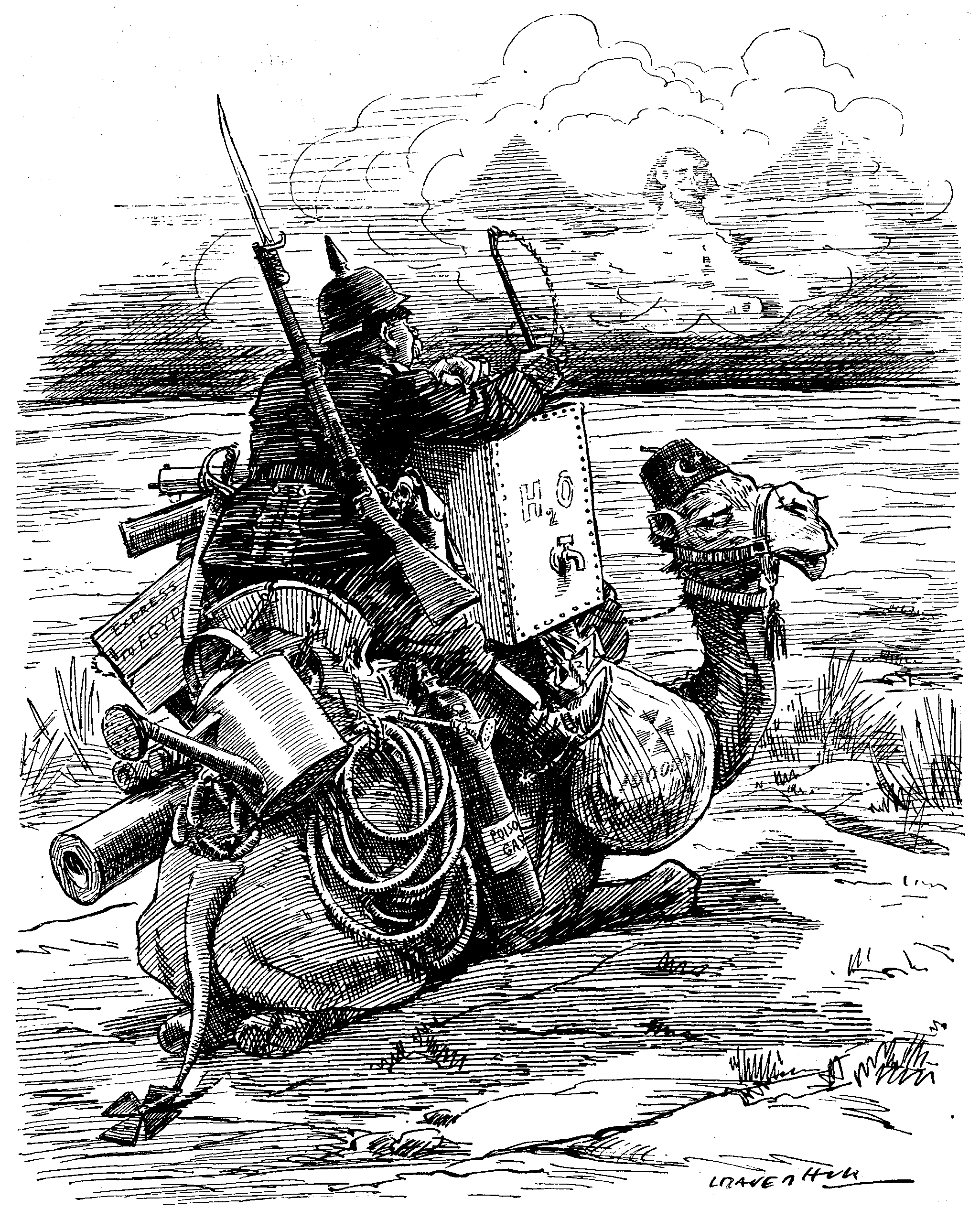

Harassed N.C.O. "Call that 'presenting arms'! If I was the King and you presented arms like that, I'd—I'd throw my hat at you!"

It is weary work being a pessimist these days, for the process of corrugating the brow and groaning at the War news must of necessity entail much energy. For some time past it has been patent to sympathetic observers that what the pessimist to-day really needs is a machine to do the work for him.

To meet this want the Electrophobia Syndicate have invented the Pessiphone—a mixture of gramophone and pessimist—believing that he who to-day can make two whimpers grow where one grew before deserves well of his country in war time. With the Pessiphone there is now absolutely no excuse for cheerfulness. It is the marvel of the age, and has very fittingly been described as worth a guinea a groan. With one pint of petrol the Pessiphone will disseminate more depression throughout the household in ten minutes than could be accomplished in a day by thirty human pessimists.

As soon as people commence to be cheerful all you have to do is to press the button and hold on to something. A child can start it but nobody can stop it. Ten minutes is all that is sufficient to give a whole family melancholia or creeping dyspepsia. It has been known to be fatal at 200 yards' range. Messrs. Wilkie Bard and George Graves have already offered a heavy reward for the body dead or alive of the inventor—a fact which speaks highly for the machine and its maker.

When the instrument was first tried on a select party of confirmed optimists two of them rushed out of the office and have not been heard of since, while the others clawed savagely at the office mat.

No burglar will go near it. It will drive away rate-collectors and poor relations. One client has already used it on his mother-in-law with favourable results.

The Pessiphone is fitted with a little oil-bath, all black fittings, self-starting lever, Stormy Arthur two-speed gear, thus rendering it easy of change from "Mildly Miserable" to "Devastating," and the whole is packed complete with accessories and delivered carriage free to your back garden, where it may be let loose.

The following letters from grateful pessimists—all involuntary contributions—speak for themselves:—

Gentlemen,—For years I have been troubled with ginger hair, but since using the Pessiphone I have had the beastly stuff turn grey.

Dear Sirs,—I used to read The Moaning Herald aloud each morning, but I now use the Pessiphone with more deadly effect.

Householder writes: Please turn the Pessiphone off at the main. None of my family has been able to get near the house for five days.

Golder's Green says: The other day the butcher's boy, cheerful as usual, was coming up the garden path whistling, and though it may hardly seem credible this so affected the Pessiphone that it actually jumped off the table and bit the boy.

"The Infectious Diseases Hospital at Colchester has been appointed to the vicarage of Hurst Green, Etchingham, Sussex."

Essex and Halstead Times.

"In the early part of the last century the sale of leeches was one of the most important. Doctors bled their patients for every imaginable ailment. To-day all that we can say of leeches is that we just keep them."—Observer.

As pets, we suppose.

The following notice appears daily in the Wilhelmshavener Tageblatt.

The statue to which it refers, known as "The Trusty Look-Out," represents a seaman in oilskins looking out over the North Sea. The face is that of von Tirpitz.

The Trusty Look-out.

Nails may be driven into the statue on week-days between 11 and 1, and on Sundays between 10 and 5. The sale of tickets for Nails and Shields takes place at the Treasury of the Town Hall during office hours, and also at the time for driving in Nails on the spot.

Further, tickets for iron Nails may be bought in the following shops: (here follows a list of three booksellers, one general store and six tobacco shops).

The prices are fixed at:—

0.50 m. for an iron Nail.

5.00 m. for a silver Nail.

10.00 m. for a small gold Nail.

20.00 m. for a larger gold Nail.

Anyone who buys 100, 200, 300 or 400 marks' worth of iron Nails receives a silver Shield with a corresponding inscription; similarly, a gold Shield for iron Nails to the value of 500 and more marks. Whoever changes a 10 mark gold piece receives an iron Nail free.

For the purpose of preparing inscriptions on Shields the date on which it is proposed to drive in the Nails must be notified at the Treasury three days in advance.

If clubs, societies, or other collections of people wish to drive in their Nails in private parties they are requested to get into touch with the Municipal Architect, Mr. Zopff, with a view to fixing the day and hour, in order that no delay may be caused by overcrowding.

Wilhelmshaven, 12th December, 1915.

For the Municipal Council.

(Signed) Bartelt.

Not in a spirit of carping criticism, but as earnest admirers of German forethought and thoroughness (Gründlichkeit), we feel it our duty to point out that there are a few contingencies for which these otherwise admirable regulations fail to provide, and we beg leave to suggest to the Municipal Council of Wilhelmshaven the following additions:—

(1) It is unpatriotic and un-German to spend more time than necessary in driving in nails, as standing-room, the number of hammers and the patience of the officials are all limited.

(2) The limit of time allowed for driving in one nail is one minute, for a silver nail two minutes, for a small gold nail two and a-half minutes and for a large gold nail three minutes.

(3) If in any case the time-limit is exceeded the Municipal nail-driver will displace the person whose lack of skill is responsible for the delay and will drive home the offending nail himself.

(4) If any person offers resistance to this procedure he or she will be nailed to the statue by the Municipal nail-driver as a warning to others. A large iron nail will be used for this purpose, the charge for which will be added to the death-duties.

(5) It is unpatriotic and un-German to use bad language when driving in nails. However, in view of the well-known tenderness of the human heart and the high state of nervous tension in which many persons of an ardent patriotic disposition may be expected to perform this supreme act of symbolic devotion, those who drive in iron nails will be allowed to swear once for each nail, or seven times for half-a-dozen nails, whilst a higher proportion of swear words will be allowed for silver and gold nails, on the progressive lines laid down in (2).

(6) Anyone exceeding the patriotic limit of bad language will be dealt with by the Municipal nail-driver as in (4).

(7) Classes of instruction in nail-driving will be held in the Town-hall daily between 10 and 11 A.M. (Sundays excepted).

(8) Persons who wish to be photographed in the act of nail-driving must give notice to the Municipal photographer two days in advance. The cost of the photograph will naturally be in inverse proportion to the value of the nail which is driven in.

"Hon. John Fellowes Wallop, of Barton House, Morchard Bishop, brother and heir-presumptive of the Earl of Portsmouth, entered his 57th pear on Monday."

Western Times.

We congratulate him on his digestion.

"Storm or no storm," said Charles, "as a medical man I can't stick this fug any longer."

He disappeared behind the heavy anti-Zepp curtains and opened the window. A piercing draught caught the back of Bill's neck and he sat up.

"Look here," he said crossly, "this is no night for a poor Special to go out in. Can't I send a medical certificate instead?"

"You cannot," replied Charles. "I will not be a party to such evasions."

"It's pouring with rain and blowing a gale. No Zepp ever hatched would come over to-night."

"That's not the point, Bill." Kit unexpectedly opened one eye. "How are Charles and I to sleep soundly in our warm beds unless we know you're outside, guarding us?"

"That's right," growled Bill. "Hub it in. Your turn to-morrow, anyway."

The other two sang the praises of bed in fervent antistrophe till at last Bill rose with a groan and assumed his overcoat, badge and truncheon. He stopped at the door.

"Charles," said he, "if after this night's work I die of bronchial catarrh, unzepp'd, unhonoured and unsung——"

"Good night, dear old thing," interposed Charles sweetly. "Run away and play, there's a good child; Uncle's tired."

He disappeared to bed.

An hour later he was awakened by a tremendous knocking at the front-door. Resolutely turning on to his other side, he tried to ignore it, but the fusillade continued and swelled. Only when it appeared likely to do permanent and irreparable damage to the building did he rush out on to the landing. There he met Kit, half awake, with his eyelids tightly gummed together.

"That ass Bill," he said peevishly. "Forgotten his latchkey most likely. Serve him right if we left him there!"

"My good man, one must sleep."

Charles ran downstairs, opened the door and indignantly confronted the glistening figure on the steps.

"It is my duty to warn you, Sir," said William's voice in an official but triumphant tone, "that one of your downstairs windows has been left open. Most dangerous. Also," he added quickly, "that I am authorised to use my truncheon in self-defence, and that anything you say may be used as evidence against you."

Dear Mr. Punch,—I see that Canon Masterman, in his Presidential Address to the Members of the Teachers' Guild of Great Britain and Ireland, delivered yesterday week, observed that the German teacher had been the servant of the State; his function had been to foster love for the Fatherland. But, he continued, "that love was degraded by jealousy, distrust and arrogance. The spirit that breathed through our 'Rule, Britannia!' was corrected in our national life by our sense of humour and self-criticism." How true and how necessary! It is indeed surprising to me that no one has said it before. Why should we dwell on the greatness of our sea-power and proclaim our resolve not to be slaves? I have always understood, in spite of the view of Sir Henry Newbolt, that Drake was nothing more than a buccaneer. The public utterance of such sentiments is surely prejudicial to "moral uplift," and, in the memorable words of Mr. Pecksniff, is "Pagan, I regret to say."

It seems to me that the time has now come when, in the interests of reticence and humanity, a serious attempt should be made to revise our so-called patriotic songs, and, though fully conscious of my own literary shortcomings, I cannot refrain from suggesting, by the following examples, the lines on which such revision might be profitably carried out. For instance, the refrain of "Rule, Britannia!" would be shorn of its thrasonical quality and rendered suitable for use in elementary schools if it took the following form:—

"Curb, Britannia, Britannia curb thy pride;

True Britons never, never, never put on side."

Another song which clamours for drastic revision is "The British Grenadiers." I cannot help thinking that it would be greatly improved if it were remodelled thus:—

"Some talk of Alexander, and some of Hercules,

Of Hector and Lysander, and warriors such as these;

But infinitely greater than the stroke of any sword

Is the pow-wow-wow-wow-wow-wow-wow of Wilson and of Ford."

There are many other standard songs and poems which could be dealt with in similar salutary fashion, but I am content to leave the task to others, and will content myself with the following original lines, which, whatever may be said of their form, have, at any rate, the root of the matter in them:—

"The men who made our Empire great

Have long ago received their meed;

Then why the tale reiterate?

Self-criticism now we need.

Then, O my brethren, lest you stumble

Look carefully before you leap;

Be modest, moderate and 'umble—

Like the immortal Mr. Heep."

Once more and in conclusion:—

"Let us be humorous, but never swankful—

Swank mars the finer fibres of the soul—

For what we have achieved devoutly thankful,

But disinclined our prowess to extol;

And, when our foemen bang the drum and bump it,

In silence be our disapproval shown;

'Tis nobler far to blow another's trumpet

Than to perform fantasias on your own."

I am, dear Mr. Punch,

Yours earnestly,

Chadley Bandman.

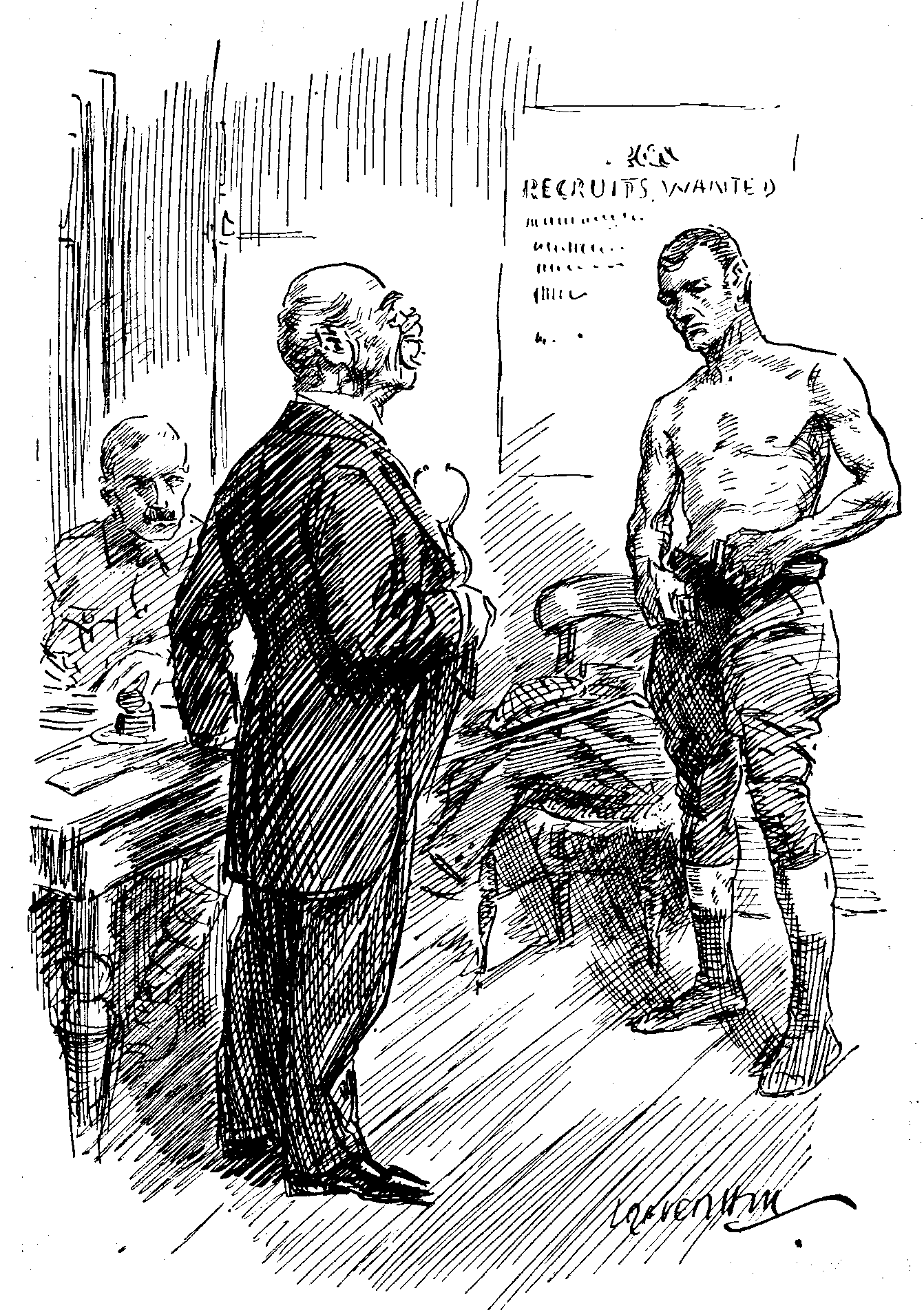

Doctor (to would-be recruit, whipper-in to the Blankshires). "Sorry I can't pass you, my man. You've got an enlarged heart."

Recruit. "Squire always says as you couldn't have too big an 'eart to ride over a country on war-time 'osses."

"There are still three gaps in the trunk line through Asia Minor to Baghdad, but these will be filled in during the course of next year, and unless we can reach the city before the Germans, they will certainly reach it before us."

Truth.

"One of Mr. Copeland's ancestors, Sir John Copeland, who captured David, King of Scotland, with 40,000 troops at the battle of Neville's Cross, after lodging the latter in Carlisle Castle, proceeded to France, to report the event to the King, who knighted him at Calais and conferred on him the Barony of Kendal."—Carlisle Journal.

In these days he would have been fined for overcrowding.

Once upon a time a rash man, wishing who knows for what?—possibly a peerage, possibly to be relieved of superfluous cash and so no longer have to pay super-tax, possibly for the mere joy of pulling wires—decided to start a newspaper.

After much consultation the plans were complete in every particular save one. The premises were taken, the staff appointed, the paper, ink and so forth contracted for, the office girls and lift girls were engaged, the usual gifted and briefless barrister was installed as editor, and the necessary Cabinet Minister willing to reveal secrets was obtained. Everything, in short, that a successful newspaper at the present time could possibly require was ready, when it was suddenly remembered that no provision had been made for a daily supply of pictures. A popular paper without pictures being such a crazy anomaly, a pictorial editor was instantly advertised for.

"Well," said the editor to the applicant for the post, "give me an idea of your originality and resource in the choice of topical photographs."

"I think you can rely on me to be original," said the young man, "and not only original but revolutionary. I have thought about it all a lot, and I have made some discoveries. My notion is that the public wants to be 'in' all that is happening. Nothing's beneath their notice; their eyes want food to feast on all the time."

"Go on," said the editor; "you interest me strangely."

"The function of the camera, as I conceive it," the young man explained, "is to serve as the handmaid of the fountain-pen. Together they are terrific—a combination beyond resistance. That perhaps is the chief of the inspirations which much pondering has brought me. One must always be fortifying the other. People not only want to read of a thing, they come to see it, and very rightly. Here is an example. We are gradually getting shorter and shorter of messengers, so much so that many shopkeepers no longer are able to send purchases home. That means that people must carry them themselves. Now what more interesting, valuable or timely picture could you have than a photograph of a customer carrying, say, a loaf of bread—a picture of the unfortunate victim of the Kaiser in the very act of having to do something for himself? How that brings it home to us!"

"By Jove, yes," said the editor, deeply impressed.

"I could arrange for someone to be taken just leaving the shop," the applicant went on; "and I would put underneath something about the straits to which the War has brought shoppers."

"Capital!" said the editor. "Go on."

"Then I have noticed," said the youth, "that people are interested in photographs of musical-comedy and revue actresses."

"I believe you may be right," the editor remarked pensively.

"So I would arrange for a steady series of these ladies, which not only would delight the public but might be profitable to the advertisement revenue of the paper if properly managed; for I should state what plays they were in, and where."

"A great idea," said the editor.

"But I should not," the young man continued, "merely give that information beneath. I should add something topical, such as 'who has just received an admiring letter from a stranger at the Front'; 'who spends her spare time knitting for our brave lads'; 'whose latest song is whistled in trench and camp'; 'who confesses to a great admiration for Khaki,' and so on. In this way you get a War interest, and every one is the better for looking at some pictures. Nothing is so elevating as the constant spectacle of young women with insufficient noses."

"Marvellous!" exclaimed the editor. "But what of the War itself?"

"Ah, yes, I was coming to that," the young man went on. "I have a strong conviction—I may be wrong, but I think not—that war-pictures are popular, and I have noticed that one soldier astonishingly resembles another. This is a priceless discovery, as I will show. I would therefore get all the groups of soldiers that I could take in open country wherever it was most convenient to my operator, and I would label them according to recent events. For example, I would call one group—and understand that they would all have non-committal backgrounds—'A wayside chat near Salonica'; another, 'A Tommy narrating the story of his escape from a Jack Johnson'; a third, 'A hurried lunch somewhere in France'; a fourth, 'How the new group of Lord Derby's men will look after a few weeks'; a fifth, 'Our brave lads leaving Flanders on short leave'; and so on."

"But you are a genius!" exclaimed the editor, surprised into enthusiasm.

"As for the rest of the pictures," said the applicant, "I have perhaps peculiar views, but I hold that they ought to be photographs of Members of Parliament walking to or from the House of Commons, a profoundly interesting phase of modern life too little touched upon; photographs of the fiancées of soldiers, of whom it does not matter if no one had ever heard before, engagements being of the highest importance, especially at a time when marriage is a state duty. So much for the staple of the picture-page, which I trust you do not consider too daring."

"Daring, perhaps," said the editor, "but not excessively so, and one must be both nowadays. One must innovate."

"And then," pursued the youth, "for padding—though padding of course only to the experts, not to the great hungry asinine public—anything can be rendered serviceable provided that the words beneath are adroit enough. Thus, a view of Westminster Abbey would be 'The architectural jewel of England which the Zeppelins have in vain tried to bomb'; a view of Victoria Station, 'The terminus at which every day and night, thousands of homing Tommies are welcomed'; any picture of a dog or cat or canary or parrot would bear a legend to the effect that all our brave lads love pets and are never so happy as when accompanied by a favourite animal; while any maritime scene would be certainly related to a recent submarine outrage, the Almighty in His infinite wisdom and prevision having made all expanses of ocean look alike."

"You are certainly," said the editor, "a very original and enterprising young man and I have great pleasure in engaging you to enrich our sheet."

But when the paper came out the picture page was found to differ in no single respect from the other picture pages in the other dailies.

Nearly three years ago Mr. E. C. Bentley wrote an excellent detective story called Trent's Last Case. We now see amongst the latest literary announcements, Bentley's Conscience, by Paul Trent.

This retaliation prepares us for a whole series of recriminatory works of fiction. Among those shortly to be expected are the following:—

The Delusions of Doyle, by Anthony Hope, and Hope's Hallucinations, by Conan Doyle.

Hewlett's Downfall, by G. K. Chesterton, and Chesterton's Catastrophe, by Maurice Hewlett.

The Curse of Cain, by Marie Corelli, and Marie the Malevolent, by Hall Caine.

Dexter Street, by Compton MacKenzie, and The Meanderings of MacKenzie, by G. S. Street.

First Clubwoman. "I noticed you talking to that old bore. Did she get on to her ailments?"

Second Clubwoman. "Yes. You might almost call it an organ recital."

After nine o'clock parade on that memorable morning the Sergeant-Major spoke to this effect: Though he, the Sergeant-Major, was new to the unit, he could and would make it plain that It Would Not Do. Had he taken up his duties in a dashed glee club or in a blanked choral society, he wanted to know? Though he had tried hard not to, he had been forced to admit that It was d——d disgraceful. He had never, he reflected aloud, seen anything like it during an active army existence that had provided many shocking sights. And he opined that there would be fatigues and C.B.s and court-martials and shootings-at-dawn if It continued. He was good, even for a Sergeant-Major.

The trouble was the hairs of the heads of the unit. And though he had rightly got the unit by the hairs which should have been short we felt it to be exceeding the limit on his part to refer to us as blanked musicians. Moreover, the band were most annoyed about it.

The Sergeant-Major paused to reflect, and to arrange matters with what he imagined was a sense of justice.

Though, he continued bitterly, we were more like a Spillikins Circle than an Army unit, he would, from sheer native kindness of heart, save us the imminent gibbet or the burial by a trench-digging party which awaited us. He would merely illustrate our manifold faults by taking the case of No. 3 in the rear rank.

"Please, Sir——" This from the outraged No. 3.

Silence must be observed. There was no excuse for the state of No. 3's hair. Here in camp (coldly), though we were five miles from a town, we had a barber, and by all report, though he had been there but two days, an excellent barber. No. 3, rear rank, did not appear to know this.

"Sir——"

Silence in the ranks. Not only was the living presence of a most valuable functionary stultified by No. 3, but he, like all his slack kind, must babble on parade. He, the S.-M., would do all the talking necessary. But even if No. 3 thought he was back in his local Debating Society even then he need not wear his hair long. The others might look at him to see what an unclipped man could come to, and afterwards show him the Barber's Tent.

A ripple went along the ranks, and No. 3's arms shot up despairingly.

There need be no demonstration, and No. 3 should remember that he was on parade and furthermore was standing at attention. He had had no orders to practise semaphore signalling.

Well, perhaps (grudgingly) he had now given the unit some faint inkling of his feelings on the matter. If at any time in the future a long hair was found on a man in his unit, etc., etc. (eleven minutes).

He would now condescend to hear any excuse that No. 3, rear rank, had to offer, so that he would be able to remark upon its utter worthlessness. Now, No. 3.

"Please, Sir," viciously, "I'm the barber."

"For fifteen years, he [Sir William Osler] said, the slowly evolving, sprightly race of boys should dwell in a Garden of Eden, such as that depicted by the poet.

During this decisive period a boy was an irresponsible, yet responsible creature, a mental and moral comedian taking the colour of his environment."—Daily Mirror.

We fancy that Sir William really said "chameleon," but most schoolmasters will think that the other word is just as good.

(Extracted from the Diary of Toby, M.P.)

Paddy. "I'll not have conscription.

Premier. "That's all right. You're left out of it."

Paddy. "Is it lave me out of it? Another injustice to th' ould Counthry!"

House of Commons, Tuesday, January 4th.—This is the Pertinacious Pringle's day. True it is also, to a certain extent, the Empire's. A Session opening in 1914 has entered upon a third year. After briefest Christmas recess Members called back to work. They come in numbers that crowd benches on both sides. Atmosphere electrical with that sense of great happenings that upon occasion possesses it. Understood that Cabinet have resolved to recommend adoption of principle of compulsory military service. Rumours abroad of consequent resignations from Cabinet. To-morrow Prime Minister will deal with these matters. Sufficient for to-day is urgent business of amending Munitions of War Bill in order to meet Labour objections.

In such grave circumstances reasonable to expect that private Members, howsoever fussy by nature, would restrain themselves and permit public business to go forward. Member for North-West Lanarkshire does not take that view of his duty. Here is a day on which eyes of nation are with exceptional intensity and anxiety fixed on House of Commons. What an opportunity for Pringle-prangling! So at it he went, kept it up not only, through Question Hour but, by interruptions of Minister of Munitions when speaking during successive stages of Amending Bill, by questions in Committee, by acrimonious speeches on Report Stage and Third Reading, he hushed Hogge, snowed-up Snowden, ousted Outhwaite, and dammed the flow of Dalziel's discourse.

In spite of this, which, in addition to major objections, wasted something like two hours, work got through a little before ten o'clock.

Business done.—Munitions Amendment Bill, recommitted for insertion of now clause, passed through remaining stages. Read a third time amidst general cheers.

Wednesday.—When shortly after three o'clock this afternoon the Prime Minister asked leave to introduce Bill delicately described as designed "to make provision with respect to military service in connection with the present War" he was greeted by hearty cheer from audience that packed the Chamber from floor to topmost row of benches in Strangers' Gallery. Members who had not reserved a seat filled the side Galleries and overflowed in a group thronging the Bar.

Since the War began we have from time to time had crowded Houses awaiting momentous announcement from Premier. A distinction of to-day's gathering is the considerable proportion of Members in khaki. The whip summoning attendance had sounded as far as the trenches in Flanders, bringing home numbers more than sufficient to "make a House" of themselves. Among them was General Seely, who contributed to debate one of its most effective speeches. He met [pg 34] with friendly reception even from that part of the House not similarly disposed when he was accustomed to address it from Treasury Bench.

The ex-Home Secretary, rising to state the conscientious reasons that compelled the sacrifice of high Ministerial office, also had warm reception from all the Benches. General regret that he will, for the present at least, resume the status of private Member after a Ministerial career as brilliant as it was brief.

Business done.—Bill requiring military service for unattested single men and childless widowers of military age introduced by Prime Minister. Blandly explained that it is not necessarily compulsory. If this class of citizen who has hitherto held back now likes to come forward and enlist he may do so under the Group system, which will be reopened for that purpose. What could be more thoughtful—or obliging?

Thursday.—By comparison with yesterday's crowded attendance and buzzing excitement, through greater part of to-day's sitting Benches only moderately full, and general conditions otherwise normal. Members who objected to carrying debate over second day felt themselves justified. Two speeches made it worth while to extend debate—one delivered from below Gangway by Long John Ward of Stoke-on-Trent, now a full-blown Colonel. Hurried over from the Front to defend and vote for Compulsion Bill, although heretofore a strong opponent of conscription. Animated manly speech, much cheered from all quarters.

Prince Arthur, who, moving from modest place habitually occupied towards lower end of Treasury Bench, seated himself next the Premier, thence shortly after ten o'clock rose and delivered a speech which recalled his greatest triumphs achieved in former days when in different circumstances he stood by same historic brass-bound box which Dizzy in his day clutched and Gladstone thumped.

As he resumed his seat amidst storm of cheering, Speaker put the Question for leave to introduce the Bill. A mighty shout of "Ay!" responded, answered by futile cry of "No!"

"Agreed! agreed!" cried the peace-makers. But the minority were out for a division and insisted on taking it. Resulted in leave being given by majority of four to one, a conclusion hailed with renewed outburst of cheering.

Business done.—Leave given by 403 votes against 105. Prime Minister brought in Military Service Bill.

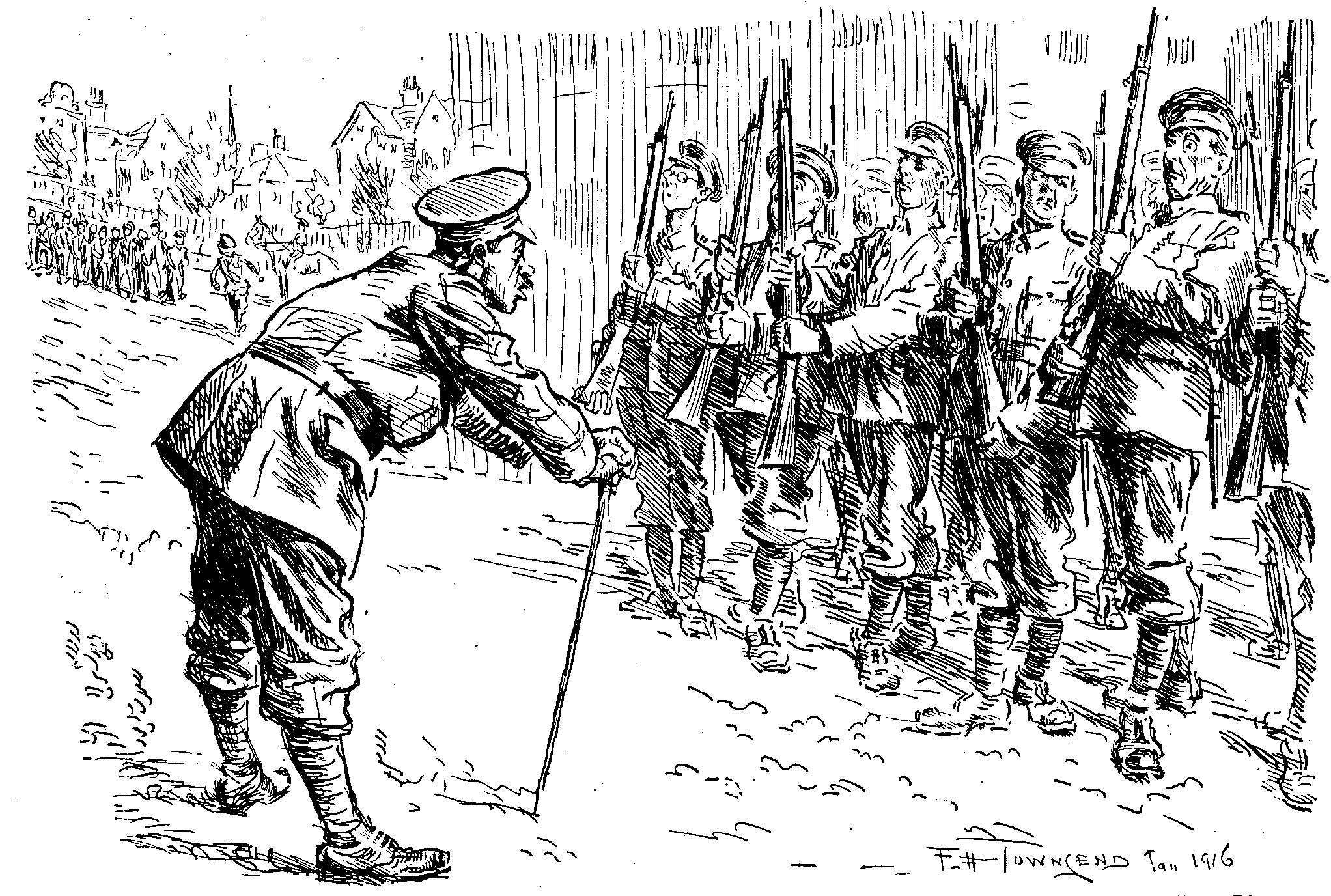

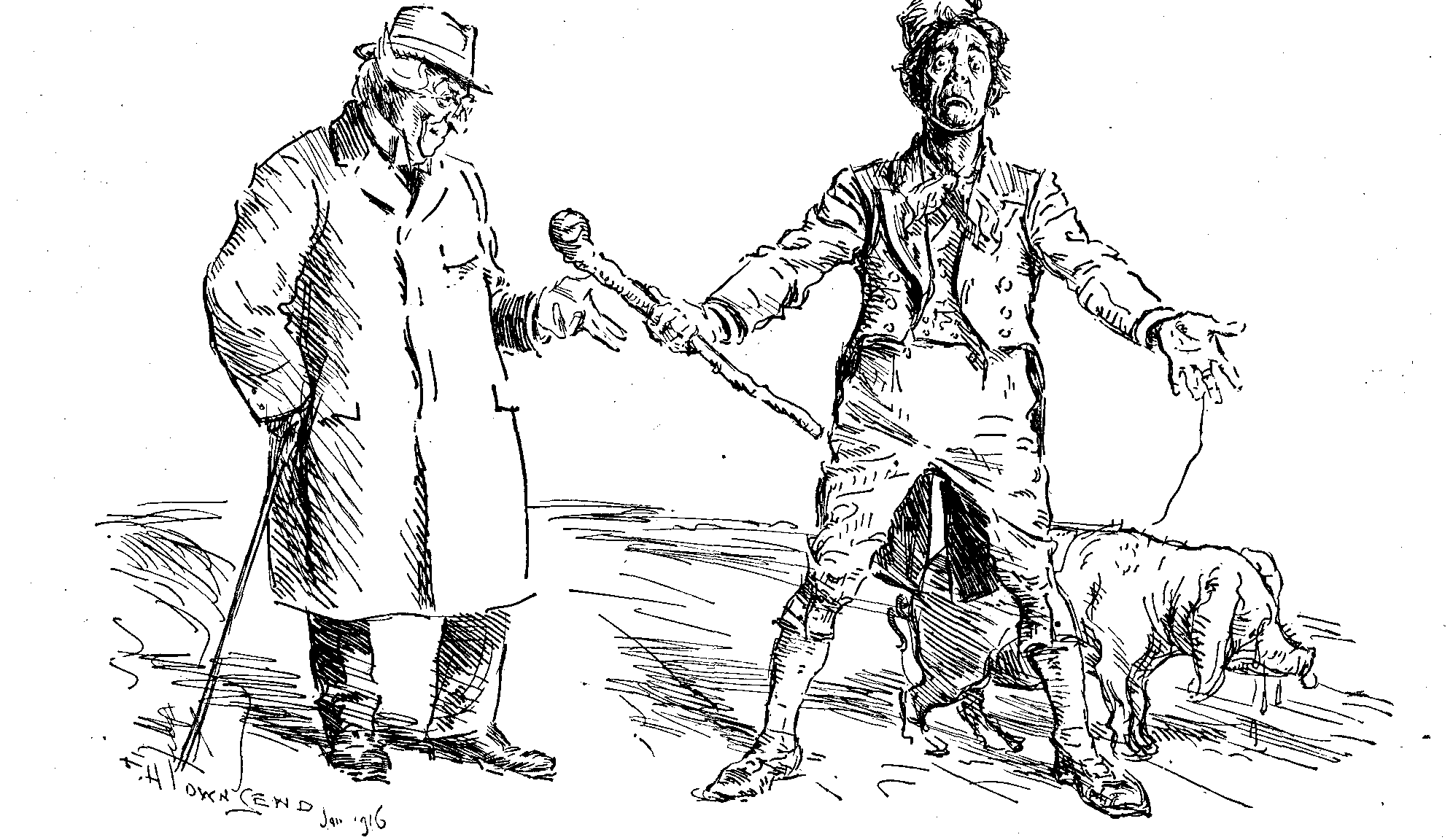

"Want to do your bit, my lad?"

"Of c-c-c-c-c-c-c-course I d-d-d-d-d-d-d-d-do."

"Then take my advice and join the machine-gun section."

"The holder of an Exchequer Bond for £100 will receive £100 on December 1st, 1910, and will in the meantime receive £5 per annum in interest."—Evening Paper.

The new security seems to have a brilliant future behind it.

"The bride, who was given away by her father, wore a dress of pale bridegroom. She was attended by the hat, and carried a bouquet, the gift of the pink taffeta silk and a large dark blue bridegroom's two little nieces."

Kentish Mercury.

What colour was the bridegroom?

"The last paragraph in Mr. A. F. Dunnett's letter, appearing in our issue of the 14th inst., contained an obvious error. 'Nathan's vineyard' should, of course, have been 'Nabob's vineyard.'"

Daily Gleaner (Kingston, Jamaica).

Of course—where the pickles grow.

"Sergeant Capes saw the fowls in a crater on Castle-hill. On the crater being opened two of them were almost dead, and others were exhausted, and could scarcely stand."

Nottingham Evening Post.

No doubt overcome by the gas.

Tradesman. "Are you insuring against Zeppelins for the New Year?"

Householder. "Well, I'm thinking of it, as I remember reading in the last raid how they dropped seventeen bombs in one area. I wonder they don't get hit, standing still all that time in the air."

I'm un'appy, so I am. Don't enjoy me beef nor jam,

An' I'm grumpy an' as 'umpy as a camel.

Bin an' stopped my leave? Oh no! That was fixed up long ago;

But the trouble is, I've got it, an' I feel afeared to go,

An' it's all alonger tin o' green enamel.

Fancy spendin' New Year's Eve, when you oughter be on leave,

In a dugout where the damp is slowly tricklin',

All alonger tin o' green an' a sniper lank an' lean

'Oo was swearin' an' a-strafin' an' a-snipin' in between,

Till the Sergeant told me off to stop 'is ticklin'.

So I trimmed meself with straw, an' a grass an' hay coffyure,

An' I clothed meself with faggots that a pal 'ad;

Then the Sergeant got a brush an' some green an' sticky slush,

An' 'e plastered me all over till I couldn't raise a blush,

And I looked jest like a vegetable salad.

Then I crept out in the night, an' I waited for the light,

But the sniper saw me fust an' scored an inner.

I could 'ear the twigs divide, but I signalled 'im a "wide,"

Then I squinted down me barrel, an' I let me finger glide,

An' I pipped 'im where 'e uster put 'is dinner.

Yus, I busted up the Bosch, but I found out, at the wash,

That enamel was a fast an' lastin' colour,

An' the soap I used to clean made me shine a brighter green;

I'm a cabbage, I'm a lettuce, I'm a walkin' kidney bean,

An' I ain't a-leavin' Flanders till it's duller.

"Income-tax can be paid in the case of individuals and firms who are liable to direct assessment in respect of trade, profession, or husbandry, in two halfpenny instalments—the first on January 1, and the second on July 1."—Glasgow Evening Times.

Lucky Scots, to get off with twa bawbees!

From an advertisement;—

"——'s Mustard Digests the Dish."

And so saves washing-up.

"Strive to acquire now ideas. Vary the hour of rising. If you take luncheon out never go always to the same place."—Daily Mail.

We seldom go always to the "Blue Lion," and usually never by the same way every time, for fear of hardly ever being unable to get out of the habit of it.

"The Westminster Gazette," writes a correspondent from Venice, "has always been regarded by the Italian Press as the most insular of English newspapers." Still we think that La Difesa, of which he encloses an extract, goes too far in referring to our esteemed contemporary as La West-Monstergazette.

"The Basker."

I imagine The Basker to be designed by "Clifford Mills" as a Tract against Dukes. And certainly her Duke of Cheviot is a miracle of obtuseness, who, if he had not been made a hero by his valet (an original and happy creation), would have grievously belied the proud old family motto, "Je me sauvegarde." George de Lacorfe, fashionable, fainéant and forty, reader of The Pink 'Un, ardent bachelor, Basker in short, suddenly finds the dukedom of Cheviot thrust upon him. Quite unlike his egregious ancestors, who went out and biffed their enemies in the gate, especially the Gorndykes, who were an unpleasant shifty kind of raiders, George proposes to resign all the Cheviot places, emoluments and responsibilities to his cousin and heir, Richard de Lacorfe, on the day the said Richard shall marry. Now Richard is a de Lacorfe with the hereditary Gorndyke blood and nose acquired on the distaff side. This conspicuous organ inflames the anger of George's grandmother, the dowager, steeped as she is in the history and prejudices of the family, while other members of the august circle harbour unkind thoughts about their kinsman.

And well they might. If anyone had "wrong 'un" written all over him it was Richard. Indeed his Roman nose was the straightest part of him. The guileless George who, though (or because) his grandmother presented him every birthday after his majority with a copy of The History of the de Lacorfes, knew and cared nothing about their glorious and stormy past, didn't suspect the Gorndyke rat in the de Lacorfe granary. Spendthrift Richard, who is always getting urgent blue envelopes from Samuel & Samuel, is bent on marrying for money the very Diana that George loves for her blue hyacinth eyes. There is a misunderstanding between George and Diana (of such a childlike ingenuousness as to suggest that really this too easy spot-stroke should be barred to playwrights), and the idiotic girl promptly engages herself to Richard, who is of course in love with a patently naughty married woman. The most reckless of lovers from the moment when in his ardour he (apparently) bites this lady's hand in the First Act, in full view of the family, till he plans a flirtation by the Cheviot postern gate on the very eve of his marriage to Diana, he is an obviously doomed villain. The lady is surprised by George in the act of knocking thrice on the said postern within. When three knocks are heard without together with the voice of Richard, the Duke really begins to suspect something. Virtuous imbecility prevails over villainous stupidity. The final blow is dealt upon the Gorndyke nose. Diana is retrieved by this last of the safe-guarders, and we are left to a melancholy calculation as to what the mental capacity of their issue is likely to be.

THE SOUL'S AWAKENING.

Nalet, the valet (Mr. Leon Quartermaine), having been dismissed for not calling George de Lacorfe (Sir George Alexander) in the morning, makes good by waking his master's soul up at one o'clock at night.

A good deal of spontaneous and honest laughter, the best of testimonials, greeted this rather ingenuous extravaganza. I think Mrs. Clifford Mills would do well not to prolong her mystifications beyond the point when they are quite clear to her audience. May I without boastfulness record that I guessed all about what Richard was going to do with the tiara quite three minutes before a well-known editor in front of me gave away the secret in a hoarse whisper to his neighbour? And that was some time before the author had finished the "preparation" of the business. And may I ask why Richard was forced to so fatuous a contrivance as the pawning of the tiara to make the exigent Samuels stay their hands for a week? True he couldn't tell them about the Cheviot deal, which was a secret between himself and George; but he could surely have used the fact of his coming marriage with Diana's money? And why didn't Diana write to her mother and ask her what was the solemn warning about Richard that she had on the tip of her tongue when she was interrupted just before going abroad? There is a mail to Singapore, isn't there? And does a George, succeeding to a dukedom, become "Cheviot" to his sister?

Sir George Alexander was at his excellent best in the lighter moods of the Basker. But I did not like to see him in pain (especially as it all seemed so unnecessary). Mr. Leon Quartermaine, in the really engaging part of the Duke's valet, who learned to think for himself and read to such excellent effect the history so carelessly neglected by his master, was quite admirable. But then he always is. Mr. Norman Forbes had little to exercise his powers in a churchwarden version of the stage-parson with a tiresome wife. Miss Hilda Moore looked charmingly wicked and acted with intelligence. The too serious rôle tossed lightly by the author into the broadest farce presents an impossible problem. Miss Ellen O'Malley never mishandles a part. Sometimes, as here, a part is not too kind to her. As George's sister she could be no more than a competent peg. Miss Marie Hemingway had merely to look perplexed and pretty, which she did with complete success. Everyone was frankly delighted to welcome back to the stage that great artist Miss Genevieve Ward as the Dowager Duchess. [pg 37] She had the sort of reception that is only accorded to favourites of much more than common merit. And she played with decision, humour and resource. Sir George made a happy and generous little speech about her. The author was called to receive the felicitations of a gratified house.

T.

A Grand Concert is to be given at the Kingsway Hall by the Independent Music Club, on January 18th, at 2.30, in aid of Mr. C. Arthur Pearson's Fund for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors. The Independent Music Club, which has been of invaluable assistance to musicians suffering from the War, proposes to entertain at least five hundred Wounded Soldiers at this Concert.

Five shillings will provide ticket, transport and tea for one Wounded Soldier. Gifts for this purpose and for the object of helping our Blinded Soldiers and Sailors will be very gratefully acknowledged by the Treasurer, Independent Music Club, 13, Pembroke Gardens, Kensington, W.

The net proceeds of a "Special Night" at the National Sporting Club on Monday, January 17th, commencing at 8 P.M., are to be given to the Wounded Allies Relief Fund.

(Inspired by the sight, anywhere in France, of the notice: "Taisez-vous! Méfiez-vous! Les ennemies oreilles vous ecoutent!")

There is something in the air,

Dinna doot!

We shall shortly see some guerre

Hereaboot.

Yes, we're going to make a rush,

Starting Tuesday next at—Hush!

Pourquoi?

Les ennemies oreilles nous écoutent!

We have got some special guns

For to shoot,

And to make the fleshy Huns

Up and scoot.

Would you care to hear the list?

There's a grandmamma at—Hist!

Silence!

Les ennemies oreilles nous écoutent!

It is more than patent to

The astute

That a very big to-do

Is en route.

There's a million men, I'm told,

Sailing round to land at—Hold!

Doucement!

Les ennemies oreilles nous écoutent!

Tho' to you, my simple friend,

It is moot

When the War is going to end

(Dat vas goot!)

I could say exactly when

Peace will be declared. But then,

Hélas!

Les ennemies oreilles nous écoutent!

I should be the very last

To dispute

That remarks, too freely passed,

Come as loot

To those wicked people, spies;

Yet what lots and lots of lies

(Mon Dieu!)

Les ennemies oreilles en écoutent!

Henry (Watch Dog).

Fickle Young Thing (revisiting Tattooist.) "Er—do you think you could possibly alter this badge on my arm? You see, I've—er—exchanged into another regiment."

From a report of King Ferdinand's address to the Sobranje:—

"The speech then exalts over victories won, and generally is couched in a rather orid strain."—Cork Constitution.

Like everything else that Ferdy does.

New Ideas for War Weddings.

"The bride looked extremely well in a gown of ivory crepe-de-chene, trimmed with filet lace and ivory aeroplane. Her hat was of gathered aeroplane, adorned with real ospreys."

Times of Ceylon.

"The ceremony and congratulations being of smilax and pom pom'mums."

Wiarton Echo (Canada).

"The public simply hand in the order and cash to any tobacconist, with the name of the man to whom the cigarettes are to be sent, and the welcome gift will reach Tommy in time for Christmas."

Advt. in Morning Paper, Dec. 31st, 1915.

Unless, as we all hope, Tommy is at home again before that.

Another Crisis Averted.

"Our London Correspondent says that he has offered to resign, but the Prime Minister refused to accept his resignation."

Cork Examiner.

"My birthday," I said, "is setting in with its usual severity."

"What," said Francesca, "has driven you to this terrible conclusion?"

"Little signs; straws showing how the wind blows."

"I wonder," she said, "how that came to be a proverb. Personally I don't keep packets of straws to test the wind by, and I never met anybody else who did. Handkerchiefs are much more certain, and men's hats are best of all."

"Yes," I said, "when I see my hat starting full tilt on an excursion I always know which way the wind is blowing right enough. Tell me, Francesca, why does a man's hat, when it's blown off, always bring up in a puddle?"

"And get run over by a butcher's cart?"

"And why does everybody laugh at the hat's owner?"

"And why does the boy who brings it back to you expect payment for the miserable and useless object?"

"And where," I said, "does the owner disappear to afterwards? You never see a man with a hat on his head that's been run over—no, I mean, with a hat that's been run over on his head—no, no, I mean, with a hat that's been run over off his head—Francesca, I give it up; I shall never get that sentence right, but you know what I mean. Anyhow I will put the dreadful vision by. What was I talking about when this hat calamity broke in?"

"You had made," said Francesca, "a cold and distant allusion to your birthday. It's coming to-morrow."

"Well," I said, "it can come if it likes, but I shall refuse to receive it. I don't want it. I'm quite old enough without it. At my age people don't have birthdays. They just go on living, and other people say how wonderful they are for their years, and they must be sixty if they're a day, but nobody would think so, and——"

"And that it's all due to early rising and regular habits."

"And smoking and partial abstemiousness."

"And general good conduct. But you can have all that sort of praise and yet celebrate your birthday."

"But I tell you I won't have my birthday celebrated. Those are my orders."

"Orders?" she said. "People don't give orders about absurdities like that."

"Yes," I said, "they do; but their orders are not obeyed. There's Frederick, for instance. He's only eight, I know, but he's got something up his sleeve. He asked me yesterday if I could lend him threepence, and did I think that a small notebook with a pencil would be a nice present for a sort of uncle on his birthday—not a father, mind you, but an uncle. There's a Machiavelli for you."

"And what did you say?"

"I told him I had never met an uncle who didn't adore notebooks, but that few fathers really appreciated them; and then he countered me. He said he had noticed that many fathers were uncles too."

"That child," said Francesca, "will be a Lord Chancellor. He'd look splendid on a woolsack."

"Yes, later on. At present his legs would dangle a bit, wouldn't they?"

"They're very-well-shaped legs, anyhow. Any Lord Chancellor would be proud to possess them."

"To resume," I said, "about the birthday. There's Alice too. She's engaged on some nefarious scheme with a paint-box and a sheet of paper. It's directed at me, I know, because, whenever I approach her, things have to be hustled away or covered up. However, it's all useless. My mind's made up. I will not have a birthday."

"You can't prevent it, you know."

"Yes, I can," I said. "It's mine, and if I decide not to have it nobody can make me."

"But isn't that rather selfish?"

"It can't be selfish of me to deprive myself of a birthday."

"But you're depriving the children of it, and that's worse than selfish. It's positively heartless."

"Very well, then, I'm heartless. At any rate my orders are that there shall be no birthday; and don't you forget it, or, rather, forget it as hard as ever you can."

"I can't hold out the least prospect that your suggestion will meet with favourable consideration."

The birthday duly arrived, and I went down to breakfast. As I entered the room a shout of applause broke from the already assembled family. "Look at your place," said Frederick. I did, and beheld on the table a collection of unaccustomed articles. There was a box of chocolates from Muriel and Nina; there was a note-book with an appropriate pencil. "That," said Frederick, "is for Cousin Herbert's uncle. Ha, ha!" And there was, from Alice, a painted Calendar fit to hang on any wall. It represents a Tartar nobleman haughtily walking in a green meadow, with a background of snow-capped mountains. He has a long pig-tail and a black velvet cap with a puce knob. His trousers are blue striped with purple. He has a long blue cloak decorated with red figures, and his carmine train is borne by a juvenile page dressed in a short orange-coloured robe. It is a very magnificent design, and on the back of it is written:—

"This is but a Birthday rhyme

Written in this dark War-time.

We can't afford to waste our ink,

And so I'll quickly stop, I think."

Thus I was compelled to have a birthday after all.

R. C. L.

Perusing the epistles I devotedly indite

You long, I know, Lucasta dear, to see me as I write;

Your fancy paints my portrait framed in hectic scenes of war—

I'll try to show you briefly what my circumstances are.

Your swain is now a troglodyte; as in a dungeon deep

He who so worshipped stars and you must write and eat and sleep;

Like some swart djinnee of the mine your sunshine-loving slave

Builds airy castles, meet for two, 'neath candles in a cave.

Above, the sky is very grey, the world is very damp,

His light the sun denies by day, the moon by night her lamp;

Across the landscape soaked and sad the dull guns answer back,

And through the twilight's futile hush spasmodic rifles crack.

The papers haven't come to-day to show how England feels;

The hours go lame and languidly between our Spartan meals;

We've written letters till we're tired, with not a thing to tell

Except that nothing's doing, weather beastly, writer well.

So when you feel for us out here—as well I know you will—

Then sympathise with thousands for their country sitting still;

Don't picture battle-pieces by the lurid Press adored,

But miles and miles of Britishers, in burrows, badly bored!

Mistress (to chauffeur, who is crawling down-hill). "Why are you driving so slowly?"

Chauffeur (ex-coachman). "Well, Ma'am, you told me to be as economical as possible these times, so I was puttin' the brake on to make the down-'ill last as long as possible."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

Narcissus (Secker), by Miss Viola Meynell, is one of those books for which I cannot help feeling that my appreciation would have been keener two years ago than is possible to-day. It is the story of the growth to manhood of two brothers, Victor and Jimmy, who live with their widowed mother in an outer suburb of London. That there is art, very subtle and delicate art, in the telling of it goes without saying. The characters of the brothers are realized with exquisite care. Victor, the elder, uncertain, violently sensitive and emotional, seeking always from life what he is never destined (at least so far as the present story carries him) to attain; Jimmy, placid, shallow, avoiding all emotion, attracting happiness like a magnet. Nothing, I repeat, could be better done in its kind than the pictures of these two, and of the not very interesting crowd of young persons among whom they move. But, for all its real beauty of style, I have to confess that the book left me cold, and even a little irritated. Perhaps we demand something more from our heroes these days than susceptibility, or indifference, to emotion. Was the purpose of life, one wonders, ever as delicately elusive as these bewildered young men seem to find it? I kept longing for Lord Derby. Perhaps, again, this is but part of the cleverness of the writer, and Miss Meynell, like the child in the poem, only does it to annoy. But I hardly think so. Her tenderness and sympathy for Victor especially are obvious. He, I take it, is Narcissus (though Narcissi would have been a truer title for the book, as each of the brothers is more in love with his own reflection than with anything else), and, since he is left unmarried at the close of the volume, I derived some quiet satisfaction from the thought that modified conscription might yet make a man of him.

Why will the heroes of historical fiction persist in that dangerous practice of leaving an angry and overmastered villain bound to a tree to await death or rescue? The result is rescue every time, and one way and another a mort of trouble for the good characters. Still it may be argued that if the protagonist of The Fortunes of Garin (Constable) had not followed this risky precedent those fortunes would not have led him where they eventually did, and we should have missed one of the best costume novels of the year. Miss Mary Johnston is among the very few waiters whom I can follow without weariness through the mazes of mediævalism. This tale of the adventures of a knight and a lady in the days when Henry II. sat on the throne of England, and his son Richard princed it in Angoulême, is told with an air that lifts it out of tushery into romance. She wields a picturesque and courtly style, sometimes indeed a trifle too charged with metaphor to be altogether manageable (as for example when she speaks of "pouring oil upon the red embers of a score unpaid"), but for the most part admirably pleasing to the ear. Her antique figures are alive; and the whole tale goes forward with a various and [pg 40] high-stepping movement and a glow of colour that reminded me of nothing more than that splendid pageant one follows round the walls of the Riccardi Palace in Florence. Of course the journey ends in lovers' meeting and the teaching of his place to the evil-minded. The fact that this latter was called Jaufre, a name that I would wish kindlier entreated, is almost my only complaint against a lively and entertaining story which more than once rises to real beauty.

Given a plot of the conventional order I dare say it is best to make very little fuss or mystery about it. So, at any rate, "Katharine Tynan" seems to think, for after about page 32 of her latest book, Since First I Saw Your Face (Hutchinson), there is really almost no guessing left to do, the authoress seeming principally concerned to ensure a smooth passage for one's prophecies. Thus, while the unknown son of a secret marriage, happening by good luck to thrash the ostensible claimant to the title and heroine, gets that successful start in the early pages that is so necessary to his happiness in the last, and the lady never really looks like straying far into disconcerting opinions of her own, even the rival himself obliges us by throwing up the sponge just when the game should really begin. All this is soothing enough, but it is also very thin stuff; and the addition of a ghostly ancestress, who lures her descendants to midnight assignations by smiling at them out of a Lely painting, does not stiffen things much. The fact is that away from such a purely Irish subject as, say, "Countrymen All," Mrs. Hinkson really has not much to tell. Sweeney's New York Stores do not harmonise at all well with her atmosphere of wistful tragedy. The effect suggests a soap-bubble trying to cake-walk.

When cattle-ships put forth to sea

From Montreal across the Atlantic,

The life on board would not suit me,

Nor you, I think. The cattle frantic,

The tough steel plates beneath the might

Of crashing waters well-nigh riven—

Ugh! Here it is in black and white,

Clearly described by Frederick Niven.

Published by Heinemann (six bob),

The book relates the ceaseless battle

Which they must wage whose steady job

Is valeting a mob of cattle;

And yet they pant to get a ship,

For jobs the owners they importune

At—mark you this!—one pound the trip!

I wouldn't do it for a fortune.

It's just a tale of common men,

Who never went to school or college,

Writ by a skilled and practised pen

Most certainly from first-hand knowledge;

It has no very obvious plan,

No movement, no connected story;

And yet I don't see how you can

Fail to enjoy The S.S. Glory.

You'll meet some men you're sure to like—

Men who would greet you as a brother;

One is that honest fellow, Mike,

And Cockney, possibly, another;

Unpolished, quick to wrath and slow,

When roused, to lay aside their cholor,

Yet are they types you ought to know

As well as did the hero, Scholar.

THE UNINTERNED PERIL IN OUR MIDST.

Portrait of Herr Pfunk ("Sister Susie"), who edits "Our Mites' Corner" in the well-known weekly, Mum's Pets, and also conducts a column of "Hints to Mothers," which is having an alarming effect on infant mortality.

In an eloquent foreword to The Queen's Gift Book, (Hodder and Stoughton), we are told by Mr. Galsworthy that it is "in the nature of a hat passed round, into which, God send, many hundred thousand coins may be poured." The coin that we are asked to put into what I hope will be a very widely circulating hat is half-a-crown, and whatever you may or may not think of Gift Books I can promise you that in this instance to pay your money is to get its worth. It is true that some of the contributors have given us work that we have already had an opportunity to know; but even here I am not grumbling, for among the stories that have already been published is Mr. Leonard Merrick's "The Fairy Poodle," a tale so full of sparkle that the oftener I see it the better I shall be pleased. All tastes, however, are catered for. You can read tales by Sir J. M. Barrie or Mr. Joseph Hocking, verses by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Mr. John Oxenham or Mrs. Henry de la Pasture, sketches by Mr. Conrad or "Sapper." But I advise you to read the lot. An especial word of praise is, I feel, due to Mr. John Buchan for a tale humorous enough in its dry way to squeeze a smile from a mummy, and to the artists who have helped to make this Gift the success that it is. In short, the book is good, nearly as good as the object for which it has been published. "In aid," we read on the cover, "of Queen Mary's Convalescent Auxiliary Hospitals. For Soldiers and Sailors who have lost their limbs in the War." Here then, by helping to provide our maimed heroes with the best mechanical substitutes for the limbs which they have lost, is a chance for us to pay a little of the unpayable debt we owe to them. Mr. Galsworthy may rest assured that his appeal to "our honour in this matter" will not be made in vain.

An extract from the Master of the Temple's sermon on "Muddling Through":—

"When we rejoiced at the efficiency of our Navy we too seldom recollected that it was primarily due to a superbly effective system of education built up by the efforts of a few great men loyally supported by enthusiastic insubordinates."—Morning Paper.

Nelson's "blind eye" is not forgotten.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

150, January 12, 1916, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 22672-h.htm or 22672-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/2/6/7/22672/

Produced by Jonathan Ingram, David King, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael