This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

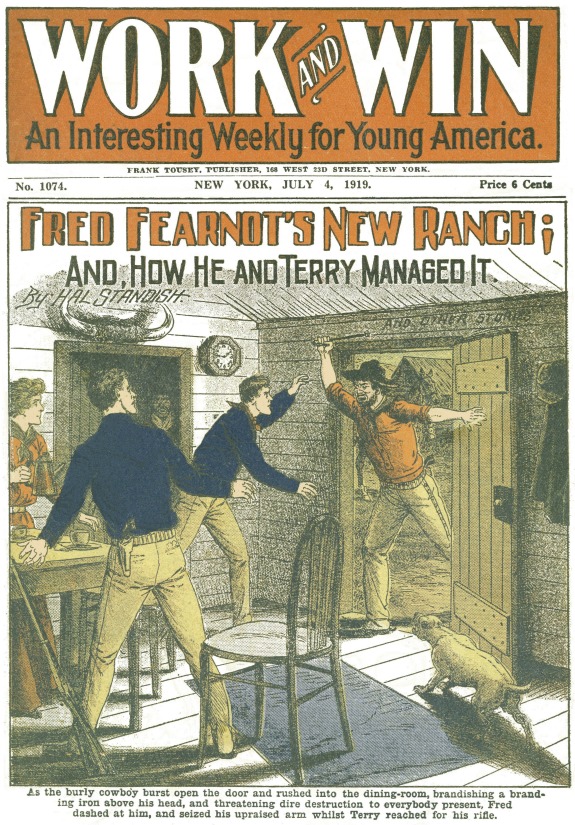

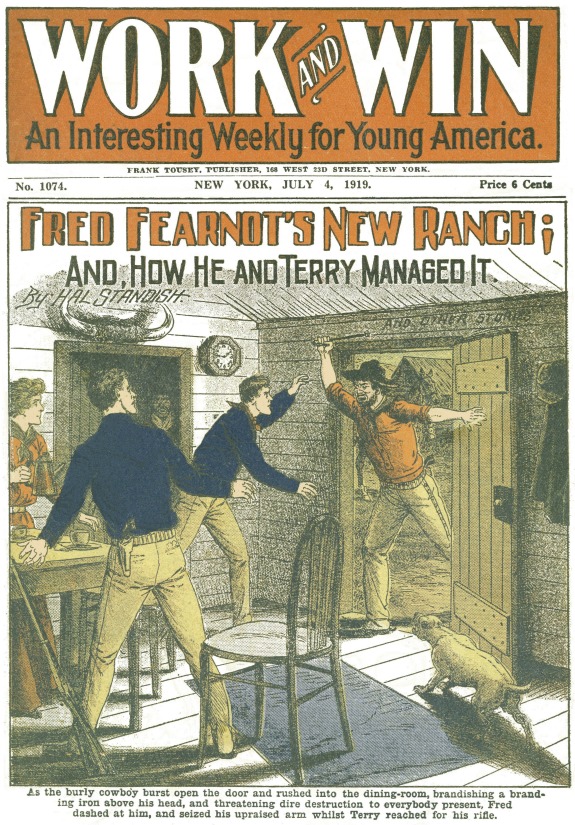

Title: Fred Fearnot's New Ranch

and How He and Terry Managed It

Author: Hal Standish

Release Date: June 10, 2007 [eBook #21795]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRED FEARNOT'S NEW RANCH***

Fearnot and Olcott remained in Wall Street after the great excitement occasioned, by Fred's sudden change of front, when he turned from a bull to a bear in the market, quietly waiting for another chance to make a deal.

All the brokers in the Street had nothing else to talk about for the time being but that singular event, and it became well known that the brokers who had been attempting to crush him the second time narrowly escaped being themselves completely ruined.

Although Fred and Terry didn't reap the benefit of the change as much as they expected, they made a neat little sum, and Broker Bellamy, who had been Fred's most persistent enemy, was so badly crippled that many brokers thought he was completely ruined.

His two nephews, thinking that Fred had been too harsh with their uncle, hired a couple of thugs to give him a good beating, but the news of their intention having reached Fred's ears, Terry kept inside the typewriter's room an hour after the close of business for some time.

One afternoon the thugs entered the room and the leader fell into Fred's terrible grip, and he squeezed his ribs so fiercely that several of them were broken. The wounded slugger's pal was roundly thrashed, too, by Terry, who couldn't resist the temptation to take a hand in it, but he was permitted to take his friend out to the hospital.

The building was so nearly deserted at the time that the news did not get out.

The two young nephews of Broker Bellamy on learning of the failure of their hired assassins, immediately sailed from New York for parts unknown, and all Wall Street became interested in the question of what had become of them, where they had gone and why they had left the city between sunset and sunrise.

Fred and Terry believed that they knew just why they had gone away, but, of course, had no idea where they had gone.

Broker Bellamy, who was very fond of his two stalwart nephews, intimated that he believed that Fred and Terry knew what had become of them, and, from that, the gossips began saying that the old broker had charged Fred and Terry with making way with his two nephews. At first Fred and Terry laughed at it, and so did all Wall Street. Nobody believed it except their enemies, who were willing to believe anything to their discredit.

Terry finally called up Broker Bellamy and took him to task for starting such a report that they had had some hand in making way with his nephews, but the old man, of course, denied the charge, whereupon Terry told him of the hired sluggers who had attacked Fred in his office, and how their attack had proved an absolute failure.

One of the sluggers had died from being shot by a crook after making confession to one of the surgeons that he had been hired by the two Bellamy boys, and that therefore he ought to understand why his nephews had absconded from the city.

The old fellow was dumfounded, and it was probably true when he denied that he knew anything about the attack on Fearnot, and so he refused to make any retraction whatever.

Then Terry wrote an account of the whole incident and had it published in one of the big dailies. This was a shock to the entire city.

Terry obtained an affidavit from one of the surgeons who had treated the wounded man in the hospital and one also from the other thug who had witnessed and taken part in the attack corroborating the charge that Terry had made.

It came very near ruining the old broker, who already had many enemies in the Street, and it gradually forced him to retire.

After that Fred and Terry took part in several more little deals, some of which panned out pretty well, while others profited them little or nothing; but in the aggregate they had gathered in a pretty good sum during the season, and they decided that they were pretty well paid for their return to Wall Street; so they finally decided to go back down into Texas to look after their new ranch and try to add another thousand head of cattle to their herd.

They wrote Jack that they were going to return south, and as soon as Jack received their letter he promptly wired back to them to stay there until he joined them, as he intended to come up after his mother and to marry Katy Malone, who was still working in the office with Louise Crane.

"Great Scott, Terry!" said Fred. "Jack has finished his house by this time, and now he is in a hurry to get his mother and sweetheart down there with him."

"Well, I don't blame him, Fred. Katy is a sweet girl and dead in love with him, while his mother wants her along as a companion."

"Very true; but, Terry, I fear that he is making a mistake."

"Don't say anything about that, Fred," advised Terry, "for it would hurt both his and her feelings, and probably his mother's. I don't see how it is possible that his house can be finished ready for occupancy in such a short time."

"Neither do I, and I'm going to wire to him and ask him if the house is finished, and if it isn't I'll just advise him to postpone his trip North until it is." So he wired to Crabtree, and the dispatch was sent down the road by the operator to him.

Jack promptly answered the question by saying that the house was not yet finished, and would not be for several months yet, but that his mother and Katy could find comfortable quarters in one of the other houses.

Fred immediately wired back:

"Take my advice, Jack, and wait until the house is finished and furnished."

The next morning he received a reply from Jack, saying:

"All right, sir, I'll wait."

"Terry, that boy is no fool," Fred remarked, as he showed him the dispatch.

"Now, Terry," said Fred, "let's see if we can't persuade Evelyn and Mary to go back with us down there. We can keep them at the hotel in Crabtree, supply them with a carriage and a pair of horses, and you know it is not absolutely necessary for us to live out on the ranch entirely yet. Then, too, we are well enough supplied with money now to entertain them in good style, as well as to add another thousand head of cattle to our herd."

"Fred, that would suit you all right, for I have no doubt but that Evelyn would be glad to go, but I am afraid that Mrs. Hamilton will refuse to give her consent to Mary's going out there, and I am sure, too, that she will never consent to our marriage if I intend to bring her down here to live. She seems to have a holy horror of Texas; for that state has the name, you know, all over this part of the country as being a place for which all law-breakers leave when the sheriff gets after them. We had that idea, too, until we stayed down there among them for a few months; but there are no better people in the world, on an average, than we have found the citizens of Texas to be."

"Well, Terry, let's take a run up to Fredonia and have a talk with the girls and their mothers. We may be able to persuade Mrs. Hamilton to our way of thinking." So a few days later they took the train up to Fredonia, without having notified the girls of their intention of doing so.

It so happened that on that very day Evelyn and Mary took a ride over on Main street, and when they had finished their little shopping Evelyn suggested that they drive up to the depot and see the train pass.

They did so, and were never more surprised in their lives than when they saw Fred and Terry emerge from the cars.

"Oh, Mary!" exclaimed Evelyn, "there are Fred and brother!"

"Where? Where?" Mary questioned.

"Why, don't you see them coming there with their valises in their hands?" and the two girls threw their arms around each other's necks and kissed each other in their great joy at seeing their sweethearts.

Fred and Terry saw the carriage and at once left the station platform and started toward it.

Evelyn sprang out of the carriage, ran to Terry, threw her arms around his neck and kissed him only as a loving sister can.

Fred dropped his valise, and, catching her in his arms, kissed her on both cheeks, while probably a score of spectators stood looking on; but then neither of them cared for that, for every man, woman and child in Fredonia knew of their engagement.

"Dear," said Fred, "how did you know that we were coming up?"

"Fred, I really can't say. Mary and I were down on Main street shopping. Suddenly the thought of you and brother came into my head and my heart suggested that we come up here, although both of us were ignorant that you boys were coming up on that train."

"Well, bless that dear heart," said Fred, as he assisted her into the carriage.

Of course, the Olcott and Hamilton families were greatly surprised.

Fred explained to Evelyn that he and Terry had succeeded in their deals down in Wall Street and had almost recovered from their losses caused by failure of the Texas bank, and that they were thinking of going back down to Texas to look after their new ranch and to try to add another thousand head of cattle to their herd.

"And you came up to tell us good-by, eh?"

"Well, we came up to see you girls, but about that I'll tell you later."

Neither of the boys went over into town during that day. They were satisfied to remain with their sweethearts, and their sweethearts were more than pleased to have them do so. Both the girls were highly pleased with the report they made as to their financial success in Wall Street.

"Fred," said Evelyn, "why not defer your return to Texas until cold weather, when I would be glad to go down with you and brother and spend the winter there, for I enjoyed myself splendidly last winter. The people were kind and sociable."

"Yes, indeed, we have found them so. When we left there, as I told you when we first came up, we were loaded down with loving messages for you from the best society people there at Crabtree, but I never saw Wall Street so dull in my life. I've had my revenge over the worst enemy I ever had there; but you know all about that, for you were down at the office at the time I changed front and got the best of Broker Bellamy and his syndicate."

"Yes, and I actually felt sorry for the old rascal. I don't enjoy other people's distress, Fred."

"No I know that; but I tell you that sometimes revenge is sweet. We didn't make as much out of that deal as we expected to, but still we have no right to complain. We have not only saved ourselves from financial embarrassment, but have money enough left to add another thousand head of cattle to the ranch and to build any kind of a house that would suit you."

"Suit me!" said she. "Are you expecting to make that your future home, Fred?"

"I'll leave that with you, dear. If you insist upon it we can live elsewhere and do as we did on the Colorado ranch, leaving faithful men to manage it for us."

"Fred, I could live contentedly anywhere in the world where you are satisfied and can make money.

"Mrs. Hamilton, however," she continued, "is horrified at the idea of Mary living so far from her. She has a great fear of the climate of Texas, and she thinks the people, too, down there are nearly half savages."

"Well, can't you tell her better than that?"

"I have told her all about how I found the people down there at Crabtree, but she says I was there at a hotel where only people of refinement live, and that I know nothing about the people out in the country. I laughed at her and asked her if she knew anything about them herself, and she retorted that everybody who read newspapers knew what sort of people lived down there."

"Well, dear, Terry and I have come up to see if we could persuade you and Mary to go down there with us and spend the fall and winter."

"Fred, I am perfectly willing to go anywhere that brother goes along with us, and I will do my best to get Mrs. Hamilton's consent for Mary to go, for she has never been down in that section of the country."

"Well, you go, anyhow," suggested Fred. "I want you to see the new ranch. I wouldn't think of making a home at the ranch we looked at when we went down to Crabtree. The one that we afterwards bought as an investment is the one I mean. I believe that we can, eventually, build up a little place of resort about that big, bold mineral spring just a mile from the railroad track, and I intend to have the water analyzed. The physicians claim down there that it has been partially analyzed and is said to be the finest water in the South, but I am going to send a bottle of the water to a chemist in New York or Philadelphia who has an established reputation and have him analyze it.

"I do hope, though," he added, "that you will plead with Mrs. Hamilton for her consent to let Mary go down and see the country."

That evening the two boys spent with their sweethearts at their respective homes.

Terry then told Mary what he wanted her to do, saying that Evelyn was going down with him and Fred to see their Texas ranch, and he wanted her to go, too.

"Mary," said he, "it is the richest ranch I ever saw in my life. We thought the one in Colorado was a grand one, and so it was, but the grass there was never so abundant or so nutritious as at our new ranch. It grows much taller, keeps fresh and green longer, and the soil itself is several degrees richer than the Colorado ranch. You never so many quail in your life as you can see there every day in the week all the year round. There are prairie chickens, and there are ten jack-rabbits there to one in Colorado."

"But, Terry, last winter you wrote me about some bad Mexican and American cowboys who had made trouble for you."

"Yes, but didn't we have the same trouble out in Colorado? Didn't I point out to you several times in Colorado the graves of horse thieves and cattle thieves whom our cowboys had shot to prevent them from plundering our ranch? Are not murders committed right here in New York City often, and don't you read of them in the papers? Why, there is no place in the country where bad men don't live, and bad women, too, for that matter; and by this time those cowboys have found out that Fred and I, as well as Jack, are deadshots and not afraid to pull a trigger on a bad character, so you can't say anything against that locality any more than you can any other in the West."

"Terry, is Evelyn going back with you?" she asked.

"Yes she has said that she would, but she wants you to go, too."

"Terry, I'm afraid that mother will never consent."

"By George, Mary, she must consent," said Terry. "I'm not going to let her destroy my happiness."

"Well, Terry, you will have to talk with her yourself."

"That's just what Fred and I came up to do, dear. Of course, we couldn't take you against her consent until after you and I are married, and if she won't consent to your accompanying Evelyn down there, why I'll hurry back as soon as I can get the home ready for you, marry you and away we'll go to just where we darn please!"

The next day Fred and Terry made a combined attack on Mrs. Hamilton trying to gain her consent for Mary to go down and spend the fall and winter in Texas with Evelyn, but she was firm in her refusal, saying that Mary had spent "nearly half her time for several years away from home, and that she was opposed to her going so far south, anyway."

Both Fred and Terry had to finally give it up in despair. Evelyn said that she would go down with them, as she had never enjoyed herself more, even up at New Era, than she had at Crabtree.

She said, too, that she had never met up with more refined people than she had there. Mary, of course, cried herself sick and begged piteously for permission to accompany Evelyn. Mrs. Hamilton, though, put up all sorts of excuses. When she mentioned the matter of expense Evelyn said that Mary could go as her guest, and that she need not spend one nickel for anything.

"Besides, mother," pleaded Mary, "I have money of my own, you know, and surely, as I am of age, I should be permitted to spend some of it just as I please."

Finding all their pleadings with Mrs. Hamilton in vain, Fred and Terry began making preparations for the long trip down to Texas, accompanied only by Evelyn.

While regretting to see her leave, her mother never objected to her going anywhere with her brother; so, after a few days' preparations, they were all ready to start.

Mary accompanied them down to New York City, where she was to spend a week with Mrs. Middleton.

They finally decided to take a steamer from New York to New Orleans, and quite a party of friends accompanied them down to the wharf. The very best staterooms in the steamer had been reserved for them. Evelyn's cabin was a bank of flowers, which loving friends and admirers had sent down for her.

Evelyn was a pretty good sailor, and had once crossed the Atlantic without the least bit of seasickness. Among the passengers was a family of New Orleans people, a father and mother and two beautiful daughters. The father was a rich New Orleans merchant whom Fred and Terry knew well by reputation, and, of course, the merchant and his family knew them in the same way Evelyn made their acquaintance before the vessel had actually passed through the Narrows. The two sisters fell in love with her at once. The elder sister was about twenty years of age and of exquisite Creole beauty. She was very much surprised when she found out that Evelyn could speak French as fluently as she could.

"Oh," said Evelyn, "I spent a most agreeable time in Paris once. My brother and Mr. Fearnot are both quite good linguists, Mr. Fearnot particularly. He can learn a foreign language more easily and rapidly than any one I ever knew. Brother can learn it easily, too; but not as much so as Mr. Fearnot."

Just as the steamer was passing out of the Narrows both Fred and Terry came up to where Evelyn was talking with the two French girls, and she introduced them to the boys.

Both the New Orleans girls looked at them as though somewhat surprised. "Why, Mr. Fearnot," said one of them, "I've heard a great deal about you, but you are much younger than I expected to find you."

"Oh, I'm a kid yet," he laughed, and Terry proceeded to amuse them with some funny stories.

The elder of the two Creoles remarked that she was very fond of the sea.

"Do you ever get seasick?" Terry asked.

"No; do you?"

"Yes, every time I get out on blue water I have to pay tribute to old King Neptune. I've done my best to make friends with him, but I always fail. He will have his joke with me."

"Ladies," remarked Fred, "if you want something to laugh at until you reach New Orleans just manage to see Olcott when he is seasick."

"Why, what is funny about it?"

"I can't tell you. He makes funny remarks and queer noises."

Evelyn laughed and said:

"Yes, he expresses opinions about old Father Neptune that I think he really ought to be ashamed of."

"Don't you get seasick?"

"Not unless the water is rough and the waves come rolling high, and then I have to retire to my stateroom for at least twenty-four hours; then I'm all right for the rest of the voyage, even if it extends all around the world."

As they were rounding Sandy Hook a great many of the passengers sought the seclusion of their staterooms and cabins, for the waves were rolling very actively.

Evelyn and the two Creole girls, whose name was Elon, remained on deck longer than any of the lady passengers on board.

By and by Evelyn and the younger of the two Elon sisters retired to their rooms.

The elder one laughed and said to Fred:

"Mr. Fearnot, we two seem to be on quite good terms with the old man of the sea."

"Yes," returned Fred. "When I made up my mind to go South by water I began to make preparations to remain on good terms with Father Neptune.

"Why, how in the world did you manage to do that?"

"Why, don't you know a remedy for seasickness, or a pallative, at least?"

"Why, no, indeed. What is it? I have never heard of any except lemons."

"Well, lemons are very good, and will be effective if you tackle them twenty-four hours or more before beginning the voyage. I have a bottle of acid phosphate in my room, and a teaspoonful in half a glass of water soon equips one in such a manner that he can resist the effects of the motion of the ship."

"Oh, my! will you give me a drink of it? I'm not at all seasick, but if the water gets any rougher I will be."

"Certainly," and Fred went to his room and soon returned with a glass with about two teaspoonfuls of acid phosphate in it. He went to the water cooler, filled the glass with cold water and presented it to the young lady.

"Drink about half of it," said he, "and in twenty or thirty minutes drink the other half."

She took the glass, tipped it up and drained every drop of its contents.

"By George," said he, "you took a good dose."

"Oh, I'm used to drinking phosphates; but never heard of it as an antidote for seasickness before. Have you had a drink of it?"

"Oh, yes; I've had two drinks since I left the wharf."

He took the glass to his room, and when he came out he tendered his arms to the girl and went promenading up and down the deck.

Her father went to her and asked her if she felt any seasickness.

"No, father," said she, "not the least bit. This gentleman is Mr. Fearnot, the famous athlete."

"Well, well, well! I'm glad to meet you, Mr. Fearnot. I heard of you several times when you were in New Orleans. What's become of your friend Olcott?"

"Oh, he's on board, and so is his sister Evelyn."

"Well, I'd like to meet him and his sister," said the old gentleman.

"Father," said his daughter, "she is just the sweetest and prettiest girl you ever saw in your life. I met her when we first came on board, but as the sea was a little too rough for her she had to retire to her room, and I hardly think that we will have the pleasure of seeing her again before tomorrow. Mr. Olcott, her brother, Mr. Fearnot tells me, is an awful victim to seasickness, and that he says and does funny things while old Neptune has a grip on him."

Then she suddenly asked her father how her mother was.

"Oh, she is in her room actually groaning and making believe that she is going to die."

"Oh, she does that every time she sails," and the girl laughed merrily.

Mr. Elon remained with her and Fred for at least a half hour. Then he drew a package of cigars from his pocket said tendered one to Fred.

"Thank you, sir; but I never smoke."

"Well you will excuse me, then, if I indulge."

"Certainly, sir; certainly." So he retired to the further side of the deck and lit a cigar by using a match made in Sweden which the fiercest wind cannot extinguish.

Then he began puffing furiously.

The girl squeezed Fred's arm and said:

"Just watch him. You'll see him slipping back to his room pretty soon. He's no sailor."

"Well," said Fred, "you seem to be a pretty good mariner."

"Yes; if you have any suspicions that I will retreat, just stick to me."

"All right, I'll keep an eye on you, for you are beautiful to look at, if you will pardon the liberty of expression."

"Mr. Fearnot, did you ever see a girl who didn't like such expressions?"

"Yes, I saw one once when she was struggling with an attack of mal de mer, and she had to yield to its effect in the presence of all the crowd, for there was no place for retreat for her. We were returning from Coney Island. The young man who was acting as her escort thought that he would compliment her by mentioning that she was the most beautiful girl on the ship. She thought it was spoken sarcastically, for she couldn't conceive how a seasick girl could be beautiful, and then just at that time she was disgorging the dinner which she had eaten an hour or two before, so she turned on him and gave him a pretty sharp rebuke."

Miss Elon laughed heartily at the story, and said:

"Well, I don't blame her, for a girl thinks at such a time as that she looks as ugly as she feels, even if she don't. Now, Mr. Fearnot," she continued, "will you please go back and bring me another dose of that acid phosphate?"

"Certainly, certainly!" and he hurried back to his cabin and returned with the glass with the phosphate in it. Filling the glass with water, he presented it to her and suggested that she take only half the dose.

"All or nothing," she laughed, and swallowed the contents of the glass.

She returned the glass to Fred with thanks, and he took it back to his cabin and took a dose himself.

To his astonishment the girl kept her feet admirably, and even when supper was announced she looked up at him and said:

"Mr. Fearnot, father and mother and sister have all retired. Will you take me down to supper?"

"With the greatest of pleasure," he replied, with a smile. "You are a strong, brave girl, and you must pardon me if I give utterance to my admiration."

"Thank you. Thank you very much, Mr. Fearnot," and, taking his arm, she accompanied him down into the dining-room, where she was the only lady passenger present.

She ate rather a light supper, and so did Fred. The meal over, they went back up on deck, for all people when seasick want to be out in the fresh air, and if the wind blows strong and cold they are all the better for it.

Of course, the air wasn't cold at that season of the year, but the wind blew fresh and strong from over the sea.

They walked about on the deck until ten o'clock, and then she said:

"Mr. Fearnot, you will excuse me if I retire."

"All right," said he, "but tell me, do you feel the least bit seasick?"

"No, indeed. I did expect to be, but that acid phosphate seemed to have been the very thing for me, and I thank you heartily for suggesting it to me."

"Perhaps you had better take another dose before retiring. You may need some, too, through the night; so you may take the bottle to the cabin with you," and he got it and placed it in her hand.

The next morning the passengers came straggling into the breakfast-room, some looking very pale and wearied; but the elder Miss Elon came tripping down the stairs like a sparrow.

While she and Fred were at the table her sister and Evelyn came in together.

Fred sprang up to accompany them to seats.

"How are you feeling, dear?" Fred inquired.

"Fred, I confess I haven't gotten over old Neptune's slap yet. Did he worry you any?"

"Not the least," and then he told her about Miss Elon's sister.

The younger Miss Elon was sitting alongside of Evelyn and remarked:

"Oh, Josephine never gets seasick."

"So I found out last night," replied Fred, "for we promenaded the deck until ten o'clock. She drank pretty freely of acid phosphate, and that removed the feeling entirely."

"Oh, my, Fred! Why didn't you offer me some of it?"

"I did for two days before we came aboard, but you refused to take it."

"Yes, but I didn't need it then."

"Well, that is the time when you should have taken it. I see you are looking a little pale yet, and it isn't too late to brace up with a dose of it now, but Miss Josephine has the bottle in her cabin."

"Yes," said her sister; "she gave me a dose of it, too, and, Mr. Fearnot, I wish you could have heard the many kind things she said about you. It's a wonder your ears didn't tingle."

"Well, well, well! Now I know why my ears did tingle so last night. I am glad I know what caused it."

Evelyn laughed with Miss Elon and remarked:

"He is good at that sort of thing."

The breakfast set the girls all right, and they went up on deck and promenaded until many other ladies appeared, some of them still showing the effects of seasickness, but by noon they were all out, for the sea was by no means very rough, and the further south the ship plowed the more quiet the waters became.

Terry didn't eat any breakfast that morning at all, unless sucking two or three whole lemons might be called by that name.

He came out on deck about ten o'clock, still entertaining very bad opinions of old Father Neptune.

He could have abused the old fellow better without indulging in profanity than any man living, but along in the middle of the afternoon he recovered entirely.

He took charge of Grace Elon, the younger of the two Elon sisters, and kept her laughing heartily as they walked to and fro upon the deck.

When they struck Cape Hatteras, where the water is always rough, it was quite late in the night, and some of the passengers felt the effect of it, which spoiled the pleasure of the evening.

The water is nearly always rough at that point on the Atlantic coast.

The next morning, though, the bosom of the ocean seemed to be like a vast mirror, so smooth was it. Seagulls were flying around, following the ship to pick up such bits of food as the cooks and waiters cast overboard. Some four or five gentlemen got out on the stern deck and with revolvers were shooting at the birds.

Nearly a dozen shots were fired without a single seagull being hit.

All sailors object to passengers shooting at Mother Carey's chickens, as they call the seagull, but the average passenger has no such superstition.

"It's a pity," said Josie Elon, "to kill such beautiful birds. How white and clean they seem to be, and what beautiful white wings they have. Every feather seems to have been made of snow."

"They are very hard to hit," remarked Terry, "and only a good marksman can hit one of them on the wing."

"Mr. Olcott, I have read in the papers about you and Mr. Fearnot being the best marksmen in the country. Couldn't you kill one of them?"

"Yes, easily, and if you want a wing to place in your hat I will procure it for you."

"I would like to have one so that I could examine the feathers."

"Wait, then, until I can get my revolver and I'll bring one down on deck here so that you can examine it to your satisfaction." So he went to his room and soon returned with his revolver.

"Now, let's get out on the middle of the deck and wait until one of the gulls flies over us, then he will drop down on the deck and he can be your prize."

He waited for about fifteen minutes before a gull flew directly overhead, and then he quickly raised his revolver and fired. The bullet actually cut the bird's head off and it fell fluttering to the deck.

Of course, the marksmanship created quite a sensation among the passengers every one of whom exclaimed that it was an accident, and that the gentleman might fire one hundred times again without bringing down another bird, but not one of them thought to ask the name of the gentleman who had fired the shot, for the ladies gathered around to examine the beautiful plumage of the gull.

There were two or three ladies on board who had wing feathers of the same kind in their hats, and some of them insisted on comparing the wings of the dead gull with some found on the hats of the ladies.

Naturally a dispute arose among them as to whether or not those on the hat were the same kind as those of the dead bird. Some, of course, were larger than others.

Terry suggested that he bring down another one that the comparison might be made as to the size and exact color to settle the question as to whether they were all of the same kind.

"See here, my friend," said one of the gentlemen on the deck, "I'll lay fifty dollars down here which says that you can't bring down another one in fifty shots."

"What!" Terry exclaimed, "do you mean to say that I can't bring down another with fifty shots?"

"That's just what I do, sir."

"Well, you are a very foolish man, if you will excuse the expression."

"Oh, I'll excuse that," said the man, "but I mean just what I say. If you had a shotgun I wouldn't make the bet, but with your revolver you couldn't hit another bird on the wing in fifty shots, and if you want to cover the bet I'll double it with pleasure."

"Do you mind my asking you another question?" Terry inquired.

"No; ask as many as you please."

"Well, I would like to know how much money you have with you."

"Oh, I've got enough to pay all I lose betting on your marksmanship. If you want to make the bet a hundred, or two hundred, or five hundred, show your money and I'll cover it."

"My friend, I really don't want your money, but I will make it five hundred dollars just to show you how foolish you are to make a bet of that kind with a stranger. Probably if you knew me you wouldn't make such an offer."

"Never mind who you are, I'm betting on the marksmanship," and the fellow drew a big roll of money from his pocket and began to count it to the amount of five hundred dollars.

"All right," and Terry proceeded to count out five hundred dollars which he asked the young lady from New Orleans to hold for him, saying that she would be his stake holder.

"Oh, my! What if I run away with it?"

"Oh, I'll take the chances of it," laughed Terry.

The other passenger also handed his roll of bills to Miss Elon, and, looking at Terry, said:

"Now, go ahead."

"Wait a few moments," said Terry, "until one flies over the deck, so that he will drop down in order that the ladies may examine his wings."

"All right; take your time," and, while he was standing around waiting he asked the young lady who was holding the money who the young man was.

"Why, he is Mr. Olcott. Haven't you heard of him?"

"No, I never did. At least not that I can remember."

The young lady seemed to be quite surprised, and asked him if he had ever heard of Fred Fearnot.

"Oh, yes, I've heard of him in the public press many a time."

"Well, Mr. Olcott is Mr. Fearnot's partner, and they are both said to be the best shots in the United States."

The fellow looked straight at Terry as if trying to size him up. He hadn't really ever heard of Olcott to his recollection but shooting a gull on the wing with a revolver was such an extraordinary feat that he was willing to take the chances. He had seen him bring down one gull and like the majority of men who take chances, decided that it was impossible for it to be done very often.

By and by he looked up and saw a gull sailing over the deck and sung out:

"There's a good shot. Try him."

Terry raised his gun and fired so quickly that none of the spectators thought that he had even taken aim. The bullet struck the gull squarely in the breast, and, of course, the bird came tumbling down right into the group of passengers.

Exclamations of surprise burst from nearly every man on the deck.

The loser didn't seem to care anything about his loss, so Fred end Terry sized him as a professional gambler.

"Would you like to try another shot?" Terry asked.

"Well, no; not at that price."

"Well, I'll give you odds of two to one."

"No, I've got enough," was the reply, and Terry laughed rather sarcastically.

"I'll give you odds of a hundred to one," Terry said.

"Great Scott!" exclaimed another passenger. "Will you give me such odds, mister?"

"Yes if this gentleman refuses."

"All right, I refuse," said the gentleman who had lost.

"Then I'll take it and put up a hundred dollars," said the second man.

"Well, that calls for ten thousand from me," replied Terry, and again he waited for a good shot.

Finally another gull came flying over, about twice as high as the first two.

Terry was going to wait for another chance, when the bettor angrily exclaimed that he must want a bird to alight on the muzzle of his revolver.

"Why, surely you don't expect to have me shoot at a bird that is really out of range, do you?"

"No, but that wasn't out of range."

"My friend, you don't know anything about distance on either land or water. That gull is at least a hundred yards above us," and nearly every man on the deck agreed with Terry, but the bettor became rather sarcastic and asked if he expected the bird to knock his hat off with one of its wings.

"Here comes another one," sung out somebody, and, looking up, they saw another gull about the same height from the deck. The bettor remarked:

"Oh, he's too high."

Everybody recognized the sneer in his tone. Terry, however, raised his revolver and fired, and the gull came fluttering, down with one of its wings actually cut off.

The bettor's friends at once began sympathizing with him, but he looked at Terry and asked if he considered that a good shot.

"Yes, I consider that pretty good," said Terry. "I brought him down, and the bet was that I couldn't hit him. I consider it a good shot because he was up so high that he could scarcely have been brought down even with a shotgun."

Neither side had put up any money in that last bet, but the gambler insisted that it wasn't a fair shot, and that he thought Terry ought to make another trial.

"No, sir," said Terry, "not for ten thousand dollars. I never play with a man of your stripe."

"Oh, you don't like my stripe, eh?"

"No, I don't. All marksmen will agree that I brought the bird down fairly. I didn't agree to shoot his head off as I did the first one, but simply to bring him down. Now, if you will take the vote of the passengers and they don't agree with me ten to one it is no bet."

The gambler tried to argue about it rather than take the vote, but Terry walked away and refused to talk with him. He was a big six-footer, weighing pretty nearly two hundred pounds.

When Terry turned his back on him and refused to talk with him he placed his hand on Terry's shoulder and turned him square around so as to face him telling him that if he meant to insult him he would throw him overboard.

Quick as a flash Terry said:

"To be frank with you, sir, I do mean to insult you. I denounce you as a dishonorable man, who won't play fair if it costs you a few hundred dollars."

With that the man aimed a blow at Terry's face with his big fist, but Terry easily parried it and gave him three or four blows in rapid succession on his chest in return, causing him to stagger back against another man, who kindly held him up.

"That's right," said Terry. "Hold him up," and in the next few seconds Terry put in three or four more blows on his solar plexus, and down he sank on the deck scarcely able to breathe.

Some friends of the man took him up and carried him into the main saloon, where others assisted him to his cabin. The captain heard of the trouble and came out on the deck to make inquiries as to whom was to blame.

He soon got the straight story of it, and at once went to the fellow's cabin and told him that if he made any more trouble on board his ship he would have him put in irons until they reached the end of the voyage.

Quite a number of gentlemen then asked Fearnot if his friend was a professional fighter.

"No," Fred replied. "He is a Wall Street broker, and is also my partner in a ranch down in Texas."

Both the Elon girls expressed their amazement at his fighting qualities.

"Oh, that's nothing," said Evelyn. "He hasn't been whipped since he was fifteen years old. I knew that that big fellow would be severely punished if he struck brother. Now, if he had struck Mr. Fearnot, he would have fared even worse; for Fred is probably one of the strongest men of his size in the United States, so far as physical abilities are concerned."

Of course, there was no more shooting that day. The ship's surgeon said that the man who had tackled Olcott would not be able to appear on deck that day.

That evening, as Evelyn and the elder Elon girl were standing out on the forward deck, gazing at the stars, Terry came up and joined them.

"Mr. Olcott," said the New Orleans beauty, "you are just the kind of a man that I have been looking for for three or four years. Please tell me how I can induce you to come courting."

"Too late," laughed Terry, "I'm already mortgaged."

"Oh, my! Just my luck."

"Don't despair," laughed Terry. "You have perhaps heard the old saying that there are just as many fish in the sea as were ever caught."

"Oh, yes. There are plenty of good men; but no more like you. I don't believe in fighting, but when I marry I want my husband to be able to whip any other man."

"All right," he laughed, "if you want me to lick a man for your husband just to please you I will do it if you will send for me."

"Oh, that wouldn't do. If my husband had to have another man to do his fighting for him, I would soon get so disgusted that I would sue for a divorce."

"Well, that shows that every man ought to learn how to defend himself. If you ever fall in love with a fellow and he wants you to marry him, insist upon his taking boxing lessons. But let me tell you the majority of boxing men are generally rough fighters, who like to get into trouble just to show their skill as pugilists. Avoid all such."

"Say, Olcott," a passenger asked Terry, "are you going to let Connolly euchre you out of the hundred dollars you won?"

"Oh, if he wants to keep it in the face of the passengers on board who heard the bet, he is welcome to it as far as I am concerned. He is no gentleman, and as such I dismiss him from my thoughts altogether. I've been up against such men before. It's a debt of honor, and can't be collected by law, and dishonorable men never pay such debts."

The big fellow remained in his cabin to the end of the voyage, not caring to come out where he would be likely to face Terry or some of his friends, who thought he was acting disgracefully. The fact is, he didn't have the half of one hundred dollars with him.

During the remainder of the voyage Fred, Terry and Evelyn, with the two Elon sisters, had splendid concerts every evening in the main saloon, to the great enjoyment of the other passengers.

The captain said that he had never heard such music, even when he had had an opera troupe on board and the New Orleans ladies requested all three of them to visit them at their residence.

They thanked them for their invitation, of course, but, stated that they would not spend more than twenty-four hours in the city, as they were anxious to reach Texas; and that they would be very busy all the rest of the season looking after their ranch.

Some of the ladies did not believe it possible that such refined young men could be ranchmen, so when the ship entered the mouth of the river all the passengers crowded out on the deck to view the scenery as they passed up the great "Father of Waters."

Fred and Terry had fished and hunted down in the country, and they explained to Evelyn all about the mode of life in the lagoon region.

Evelyn had fallen in love with the two Elon sisters, and their father became such an admirer of Fred and Terry that he insisted that they should not go to any hotel, but during the twenty-four hours that they spent in the city they should be his guests; so when the steamer landed at the wharf in New Orleans, he divided the party so that his wife and one of his daughters should drive home in the family carriage with Evelyn and Terry, while he and Fred and his other daughter should remain on board the steamer until the carriage returned for them.

When they reached his residence they found that it was one of the finest and most beautiful homes in the city, and that everything about it told of great wealth.

The next day Fred and Terry accompanied Mr. Elon downtown to visit certain friends, and the Creole gentleman soon learned that his guests had many other friends there, too.

But for the fact that they were in a hurry to reach Crabtree, they would have remained in the city as their guests for at least a week.

As it was, they spent another day there, and had a royal good time.

Then they took leave of their newfound friends, boarded the train for Texas, and were soon whirling westward. It was a long ride from the Crescent City to Crabtree, for that place was way down on the western side of the State, and it was late in the night when they reached there; in fact, long past midnight.

Fred had wired to the clerk of the hotel for him to reserve comfortable quarters for them, and when he arrived he found that the best rooms in the house had been assigned to them.

When they appeared in the breakfast room the next morning at quite a late hour for that meal, all the ladies stopping at the hotel were on the lookout for them. Those of them who knew Evelyn rushed into her arms.

"Great Scott, Fred!" said Terry. "Here we are with our arms ready to receive them, and not one will even put up a pucker at us."

"Well, what show can we expect to get with such a rival as Evelyn?"

Many of the ladies had already had their breakfast, but they went in and sat with Evelyn, and their tongues rattled like those of so many magpies.

Of course, they all shook hands with Fred and Terry, and talked freely with them. They wanted to know when Miss Hamilton was going to come down.

"Oh, she'll come down some time," laughed Evelyn, "probably on her bridal tour."

"Oh, she wouldn't come down as you did, eh?"

"No, we begged hard for her to do so, but she wouldn't. Brother will have to go up some time and bring her down. Then, too, we will have two brides down at the ranch, for young Mr. Cameron has a sweetheart up in New York, and she is waiting for him to build and furnish a big house, for her."

"Well," said one of the ladies, "work on that house is going on fast; but, look here, Miss Olcott, are you going to stay down there on that ranch, or are you going to stop here at the hotel?"

"Oh, she'll do both," put in Fred. "She is very fond of the actual life of a ranch. She often came down to our ranch in Colorado with four or five other girls, and she delighted in nothing so much as dashing over the prairie on horseback, chasing coyotes and jack-rabbits, or else feeding the pigs, chickens, and the milch-cows, all of which we had in abundance around us there. We have some fine milch-cows on the ranch now, and I expect to see her out every morning with her sleeves rolled up and a big apron on, milking them and looking after the pigs and chickens. She pets every animal on the place."

Whereupon Evelyn invited several of the ladies to come down and visit her on the ranch and help her feed the pigs and chickens and milk the cows.

"But I'll have to ask you to wait until I see what sort of quarters brother and Mr. Fearnot have for me."

"We have nothing but a plain ranch house, but there are plenty of them, for we haven't put in the improvements we intend to. Men, you know, can rough it; but sister will have a neat room fixed up for her. We will get the best furniture that can be found in this place, carpets and everything necessary for a lady's comfort."

"No, brother," said Evelyn, "I want to rough it, and you promised that I could do so."

"Oh, yes; but I know you girls, and you get tired of roughing it very quickly."

"Well, let me rough it until I do get tired, and when I feel that I have had enough I'll let you know."

"All right; that's a bargain."

The next morning, after their arrival at Crabtree, Fred, Terry and Evelyn were kept busy shaking hands with their friends. As the news spread through the city fully a score of young ladies called at the hotel to see Evelyn, for she had the happy faculty of making and retaining friends wherever she went.

Fred and Terry, though, at noon, took leave of her and told her to enjoy herself until they came back, as they were going down to the ranch and begin at once to fix up things so that she could he comfortable.

Jack happened to be at the water tank when the engine of the freight train stopped there to take a drink, and he gave a regular Indian war-whoop when he saw the boys alight. He hugged both of them as they climbed down from the engine, and fairly danced a jig in his delight at seeing them.

Terry looked around for the big house that Jack had been building for his mother and sweetheart. When he saw it, he exclaimed:

"Great Scott, Jack! What is that you are building out there? A hotel?"

"Well, I call it my bachelor quarters, for the present," he replied; "but when mother comes it will be our home."

"Well, what in thunder do you want with such a big house? It's big enough for all the cowboys on both ranches to live in."

"Well, there is no hotel down here, you know, and there is not likely to be one for several years to come; so, when any friends come down to visit us, we'll have a place to take care of them."

"Jack," said Terry, "Evelyn came down with us."

"Great Scott! Ain't I glad! But why didn't you bring your girl with you?"

"She wouldn't come, Jack; but sister came down with us, as she wanted to help us build up a home out here. So, until your mother and Katy comedown, we'll let her be boss."

"Yes, and what a boss she will be. I've been telling these fellows around here that she is the most beautiful young lady in the whole country. But when is she coming down?"

"Just as soon as we can fix up one of the four-room houses for her, for we will live there until we can build a larger house."

"What do you want to build a house for when my house is large enough for forty people?"

"Oh we want to get into our own home. We want to build a residence down at the mineral spring."

"Oh, that's a mile off."

"Yes, so it is. The depot here, though, is a general resort for every rough character who comes along; but we'll have some of our lady friends down here both from Crabtree and from the North. We'll fence in the spring to keep the cattle from crowding around it, make beautiful flower gardens, raise all sorts of vegetables and fruits, and try to make our home here as lovely as our home up at New Era was."

Jack and Terry led the way up to the house in which Jack had been living, each carrying a valise.

Before they reached there, at least half a dozen cowboys rushed up and wanted to carry the valises for them, and made every demonstration of pleasure at the return of the "Bosses."

When the boys reached the house they found that one of bed-rooms furnished and still another which had not been furnished up.

"Jack, my boy," said Fred, "I see you have been keeping quite comfortable since we left."

"Yes, and at the same time quite busy."

"Well, have you had any trouble with the cowboys?"

"No, only in one instance, when one of the men got drunk and I promptly discharged him. He was one of your men, too. He refused to be discharged, and wouldn't leave, but went on working with the others. I then told him that I wouldn't pay him a cent at the end of the month for his work, as he was doing it of his own accord, and needn't expect any pay for it. After a week he signed the pledge, came around to see me, and said that he wished to apologize, and that he would never touch another drop of whisky. I told him that on those conditions he could keep his place, but that I would keep his written pledge to show to you, so that if he ever broke it you would know what to do."

"That's right, my boy, that's right. It don't pay to be too harsh. Always give a man a chance. You were fortunate in not having any more trouble than that."

"Well, I did have several other little difficulties which did not amount to much of anything; but at least a score of big, rough fellows are waiting for you two to return home in order to get a chance to enter your employ."

"Well, we'll need a few more men, Jack, for we are going to buy another thousand head of cattle and rush them down to the ranch as soon as possible. How has the store been getting along?"

"It's been doing fine. I've done a good business, and the trade is growing fast."

"Any cattle thieves been getting in their work?"

"Well, I haven't heard of any, and I have had the cattle rounded up three or four times and counted them; but I haven't much faith in the accuracy of the count. I am beginning to suspect that both ranches have lost a few, for I fear that the cowboys haven't kept as strict a watch as they should have done. One day three big, rough follows came into the store and wanted to raise a rough house, and I requested one of my cowboys to go in there with me and help me to preserve the peace. Do you remember that fellow whose name was Nick Henderson?"

"Yes, I know him," said Terry. "Did he stand by you all right?"

"You can bet he did. I wouldn't swap him for any of the cowboys I've seen since I landed here. He doesn't understand the science of boxing, but he does know how to use his muscles and no mistake, for he fanned out two of those fellows with bare fists. One of them wanted to use his gun, but I drew mine, and said that I would shoot first; so Nick just cleaned out both of them, and I believe he is like you and Mr. Fearnot–not afraid of anything. He is now said to be the best man on either ranch, and he feels proud of the name."

Jack pointed out the house which he assigned to the carpenters, saying that they had built bunks, brought down their own blankets and cooking utensils, and that they were all satisfied with their work and their way of living.

"I furnish them meat and bread," he said, "and they do their own cooking, and I've been cooking my own meals, too."

"What sort of a cook are you, Jack."

"Well, I guess I weigh at least ten pounds more than I did when you left here. Whether it is good cooking or not, I don't know; but it is good, wholesome fare. I made coffee just as you taught me. I'm not good at making biscuit, but I can make a good hoe-cake."

They went into Jack's kitchen, and looking at his utensils, saw that he had a place for everything, and everything in its place.

"Jack; how did you learn to cook so well?" Terry asked.

"Why, I used to help mother a good deal, and I have the timber brought up and cut and piled away, so it is easy to build a fire. I had a well driven down in the yard out there, and a pump attached to it. It is not as good water as that down at the spring, but it is better than the average well around through this State, and I didn't have to drive down but thirty feet, either."

"Good! If you were wrecked on a lone island, you would get along all right, my boy. What is the bill of fare at your hotel now?

"Just anything you want that the market affords. When I want fish I go but to the lake and get it. When I want quail or prairie chicken they come right up to the house to be shot."

"All right, Jack. We'll help you cook, and if anything more is needed than the market here affords, we will get it from Crabtree."

On further inspection they found that he didn't have a carpet in the house, but that he had good sheets and blankets and pillows and first-class mattresses.

"Fred," said Terry, "we'll have to live in this house until Jack gets his home finished. We'll measure the size of those two rooms back there, and one of us must go back to town to-morrow, buy carpets, have them made, and lay in all other necessaries for Evelyn's comfort, and let her invite some of the ladies up there to come down and rough it with us as long as they are willing to do so. Evelyn, of course, will go with us and assist us in making the purchases."

They went out into the stable lot, saw the horses kept there. Then they visited the cow lot and their barns, and saw that the milch-cows were looking well, and, of course, fat and yielding an abundant supply of milk, which Jack sent up to Crabtree every day, besides having plenty of butter and milk for all the cowboys in their employ.

Jack, too, had a good flock of chickens in his barn-yard, so he had plenty of eggs; but he stated that he had not killed a single chicken since Fred and Terry had gone North, as he preferred quail and prairie chicken. He also stated that he had been compelled to clip their wings very close, as his cowboys told him that if they got out they would find such abundant feed in grass seed and other products of the plain that they wouldn't come back home again.

"Don't you believe that, Jack. If a hen raises a flock of chickens and she and they are fed regularly, they will never leave the place; but chickens who are allowed to run everywhere, as most ranchmen let their chickens, will, of course, become wild like any other fowl."

There were about a score of little pigs on the lot that were as fat as butter and gentle as kittens.

"By George, Terry," said Fred, "won't Evelyn be delighted with these little fellows? But we will have to have ducks and turkeys."

"Yes, wye can keep the ducks in bounds all right; but it will be a little difficult to keep the turkeys in, unless we have a wire fence enclosure reaching up about fifteen feet high."

"Oh, we can do that. Turkeys are very fond of wandering over a wide range; but I think we can keep them in bounds."

That night, they had a good supper of broiled beefsteak, good hoe-cake, milk and butter, and coffee in abundance. The two boys praised Jack highly for his skill in managing things, and, of course, he felt very proud.

They told him that Broker Middleton had used some money belonging to his mother, and had made about twenty thousand dollars for her, which she had sent by them in a draft which she had purchased in the bank.

Jack fairly whooped with joy.

"It's just in time," said he, "for I haven't been able to sell any cattle at this season of the year."

"Jack," said Terry, "don't you worry about the future. You just take good care of that money and don't use it except for necessities. How are the cattle on your place?"

"Mr. Olcott, they are the finest cattle I ever saw in my life. You would he astounded to see how they have picked up flesh. The ranchman that we bought them from must have had very poor ranges for them to feed on."

"Oh, well, the grass out here has never been fed on before, except by stray cattle, so I don't wonder at their being fat. When cold weather comes we'll have many thousands of pounds more than the ranches above here."

After supper some of the cowboys from both ranches came in to have a talk with their employers. Every one of them was smoking a pipe, as they could always buy tobacco at the store. The stock in the little store had about doubled since Fred and Terry went north, showing that a good business had been done.

"Jack, does the storekeeper keep his accounts straight?"

"Oh, yes. I watch him very closely. I think he is an honest man too, and he doesn't sell anything on a credit except to the cowboys on your ranch and mine. Other cowboys come in and want credit, but I told him not to credit anybody off of our two ranches, as we can then always know how much they owe before paying them off. The storekeeper says that cowboys are generally careless about paying debts, except in bar-rooms."

Before going to bed, Fred and Terry measured the size of the two rooms that they wanted to fit up for Evelyn, and Fred boarded the first freight train engine that went up the next morning and so reached Crabtree before Evelyn had finished her breakfast. She was very much surprised at seeing him.

"Fred," said she, "where is brother?"

"He is down at the ranch, just the happiest boy you ever saw in your life. He had milked two of the cows by sunrise this morning."

"I never knew brother to do such a thing before in his life," she laughed. "How many cows are there?'

"Oh, about a dozen, and their milk is as rich as butter, and as yellow as gold. It would tickle you to death to see Jack feed the little pigs buttermilk. Each little pig tries to get more of it than his neighbor, and then just to think, too, we have a good flock of chickens, those we bought before we went up North; and Jack has never killed one. On the contrary, he has bought upwards of a dozen hens, and the barn lot is just overrun with little ones."

"Why, hasn't he killed any of them. Fred? Doesn't he like chicken?"

"Yes, he is very fond of them; but the quails and prairie chickens actually come up and beg to be shot, and he has never had a chance at an unlimited supply of game before in his life."

"Oh, Fred, when are you going back down there?"

"I'm going to-night."

"Well, can I go back with you?"

"Not just yet. I want you to go with me, though, and help me select two carpets, which will be on the floor of your home."

So she ran upstairs and got her hat and gloves, and went out with him.

She wanted to select coarse ingrain carpets, saying that fine carpets were not needed on a ranch.

"Evelyn, you must select the very best velvet carpets that can be found in this city."

"Fred, that is reckless extravagance."

"No, it isn't. A good velvet carpet will last just twice as long as an ingrain one. I'm not going to buy anything cheap. The best is always the cheapest. I want sofas, chairs, rockers, and tables, and then such other dainties as your good taste may suggest. It is to be the home of my sweetheart and Terry's sister, and we expect you to have quite a number of young ladies from Crabtree to go down there and spend as long a time as they choose, to be company for you. Then I'll buy a bookcase and have plenty of books and magazines; for both Terry and you, as well as I, are fond of good reading. Then we must have some good strong oilcloth to put on the kitchen and dining room floors," and she followed Fred's instructions, and made her choice of the carpets, and Fred, in paying for them, offered them to the dealer to have them made up at once. Then they selected chairs, tables, bureaus, a bookcase, and everything else that was conductive to comfort.

Evelyn was a little bit surprised when she saw what the total amount came to, but Fred told her that she must not put in any objections, whatever. He said that if she wanted to rough it she could go out of doors into the barn lot, the cow lot, and the lot in which the pigs and chickens were kept and amuse herself to her heart's content.

The greater part of the day was taken up in making their purchases. Then, about sunset, Fred returned to the ranch on the engine of a freight, leaving Evelyn in the hotel.

The lady guests of the house were quite disappointed, as they thought they would hear him sing and play during the evening, but she told them that he was preparing a house down on the ranch for her and a number of their friends there in Crabtree, whom they were calculating on being able to persuade to go down and spend some time with them.

Of course, quite a number of them were quite eager to go.

All that night Evelyn was dreaming of feeding a big flock of little chickens and little pigs, and looking after and petting the mild-eyed milch-cows, and awoke fully convinced that she was going to have the happiest time of her life with her brother and her sweetheart as her daily companions.

Many a time had she milked her mother's cows in Fredonia, and she enjoyed the exercise as well as making butter.

Butter-making was a passion with her, and she understood it to perfection.

The next day she talked quite a while with several married ladies, particularly those who understood housekeeping and milking and butter-making. The ladies seemed to be surprised at her enthusiasm, and asked her if she had ever milked a cow, or churned butter, and her replies actually staggered some of them.

She said that if she were worth a million dollars, that there was no amusement she would rather indulge in than to milk cows, feed chickens, gather eggs, and do all sorts of domestic work.

The idea of a society girl indulging in such amusements seemed incredible to the ladies at the hotel.

Three days passed, which Fred and Terry improved by cleaning up around the house. When the carpets came down, with men to lay them, the furniture was moved in, and shades and lace curtains put up, until really the plain little ranch house was more elegantly furnished than many of the homes of the richest citizens in Crabtree.

Then, Terry went up to Crabtree after Evelyn. He went on a freight train engine, and Evelyn wanted to come back on the same; but he insisted upon hiring a carriage at the livery stable and driving her through.

Two young ladies at Crabtree offered to go down to the ranch with Evelyn, but she suggested to them to wait until she first found out whether the new home was one to which she would like to invite them.

"If the place is such that I can offer you comfort, I will notify you, without delay," so they remained behind at the hotel.

The driver then started off down the road at a clipping pace. Terry had hired a splendid team, and the driver understood well how to manage the beautiful horses.

The dirt road ran all the way down in sight of the railroad. They passed many beautiful suburban residences during the first three or four miles, after which they passed farmhouses and then the road stretched white and straight over the wide prairies.

Terry had directed that Evelyn's two trunks be sent down by freight. Evelyn enjoyed the ride very much.

"Brother," said she, "the grass seems to be greener and richer down through this country than up in Colorado."

"Yes, and so it is, else we wouldn't have bought down here. We have some advantages here that we didn't have up there. There we had to drive our cattle and receive our freight twenty miles away; but now the railroad runs right along beside us, and the depot is on our side of the track. Jack's ranch borders the road on the other side. The company has laid side tracks for each ranch, and built a good depot. I think, in the course of time, we'll have a far more beautiful home down here than we had up in Colorado. Of course, though, Fred has told you all about the magnificent mineral spring a mile from the railroad and on the ranch."

"Yes, both of you have told me all about it."

"Well, Fred thinks it best to build a residence right down there near the spring in order that we may have the use of the water and some large shade trees in the yard."

"Terry, isn't there any building there now?"

"No, the only buildings we have now are merely four-room frame buildings for the men on the place, and we have fixed up one of them for our home until we build a larger and better house down near the spring. There isn't a particle of swamp about it; but there is plenty of good solid earth all around it. Of course, we can cut a splendid road from the depot down to it. We will build stables and all the necessary out-houses down there, too, and will fence it in, so that the cattle cannot annoy the residents of the place. There isn't a passenger depot built yet, and passenger trains don't even stop there, unless they are flagged by the freight agent."

The road passed through several patches of timber and wide stretches of prairie land presenting scenery that Evelyn loved and admired very much. The splendid team made the trip in a little over two hours, a distance of twenty miles.

"You see that big building going up out there?" said Terry, pointing to Jack's new home.

"Yes."

"Well, that is the new house that Jack is building for his mother and his wife. It has a dozen large rooms in it."

"Well, what in the world does he want with such a big house away out here?" Evelyn asked.

"Well, it is the first house he ever owned, and he says he wants it roomy enough for his wife's and mother's friends to come down and stay as long as they please, as it will cost him nothing to board them. I guess that Fred and I will build a house just as big as that."

"Terry, you and Fred must not indulge in any such extravagance."

"Sister, don't you know that comfort is not extravagance?" The driver had never been out there before, so he turned and asked Terry where he must stop.

"Right in front of that house out there," and he pointed to the house which he and Fred had furnished for their home until a big house could be put up.

Both Fred and Jack were on the lookout for them. Evelyn saw them waving their hats and she waved her parasol in return. They reached the house about the time that the carriage did, and of course, as Fred lifted her out of the carriage he caught Evelyn in his arms and kissed her several times. Jack seized her hand and kissed it, saying:

"Heavens, Miss Evelyn, but I am glad to see you way down here."

"Thank you, Jack," said Evelyn.

Then she turned and glanced around at the wild prairies on either side of the railroad track.

"Evelyn," said Fred, "come in and see the little home we have fixed up for you," and he led her up on the little piazza and into the two rooms that had been furnished up for her.

Of course, she recognized the carpet, because she had chosen it herself up in Crabtree, and also every piece of furniture.

"Oh, my, how beautiful!" she exclaimed. "But how out of place such furniture in a ranch house! I dare say there is not another so beautifully furnished as this is in the State of Texas."

"No," said Fred, "nor is there another house in all Texas with such a beautiful mistress to reign over it."

She laughed and seemed pleased with the compliment.

As soon as she could throw off her hat and light coat she said:

"Now, Fred, let me see the kitchen and the dining-room."

"All right. This leads into the dining-room," so she went in there and seemed equally pleased with its furnishings and then she looked into the china closet and found two complete sets of china dishes.

Then she went into the kitchen, where Fred and Terry had set up a first-class range to take the place of the wide-open fireplace which Jack had been using. The carpenters had built a splendid closet for all the cooking utensils. There were all the necessary tables and chairs there in the kitchen. She went to the sink and, turning the faucet, saw a splendid flow of water.

"Why, where in the world does this water come from?" she asked, very much surprised.

"Oh, that is one of Jack's ideas," replied Fred. "While we were away he got permission from the superintendent of the railroad to run a pipe from the railroad company's tank, some three hundred yards away, and thus provided for a supply of water for household purposes as well as a bathroom. Those are New York ideas which he brought out here with him, and people who have visited the premises wondered what the Yankee boy was up to. Of course the water isn't for drinking purposes, for he has a driven well out in the yard, and the water is very good; but still it is not like that down at the spring."

She turned around and patting Jack on the shoulder said:

"Jack, were you thinking of your mother or of Katy when you were fixing up all these comforts?"

"Of both, Miss Evelyn," he answered, "for mother is as fond of comforts as any other woman. She does her own cooking, and I am having water pipes run from the same source into our house."

"By and by," he continued, "I'm going to see if I can't find artesian water somewhere on the premises, and have it running through the house all the time."

"Good boy! Good boy!" laughed Evelyn. "Now, brother tells me that you have pigs and chickens and milch-cows on the place, and I want to see them at once."

Terry and Fred and Jack went out with her. They first went to the big stable, saw the saddle and carriage horses that they had bought, and she was pleased with their appearance.

"Evelyn, here are a pair of grays," said Fred, "which Terry and I say belong to you and Mary, and we hope you will love them as much and train them as you did those up at Fredonia."

"Oh, my. That is work for me, but I am glad of it. Have they good dispositions?"

"Yes, the stable-man says that they are kind and gentle and very susceptible to kind treatment."

From the big stable they emerged into the big barn lot, passed through a gate in a division fence, and saw a big flock of chickens. There were about one hundred of the little things, all like little balls of down, following clucking mother hens all over the place.

Evelyn went into such expressions of delight at seeing a splendid flock that made the boys smile.

"Haven't you any turkeys?" she asked.

"Not one," said Jack. "All the cowboys told me that the turkeys would go off and find such an abundant supply of things to eat that they can't be kept at home. But we have ducks and geese, which are kept over in another lot."

"Then they passed through another gate, where Evelyn saw a row of cow-sheds, and a half dozen splendid looking Jersey cows.

"Oh, my," she cried. "I never saw such fat, beautiful milch-cows in my life."

Jack ran up to two of the cows and put his arms around their necks, patted their faces and noses, and the mild-eyed beauties seemed to enjoy the petting.

"Fred, where in the world did you and brother find Jersey cows way down this way?"

"Oh, we found them on some ranches on the line of the railroad further back east. We paid a pretty good price for them, too. Down here the ranchmen don't seem to understand the value of the Jersey cow; so when we offered them a price that seemed the least bit extravagant, they readily parted with them. We are going to get more of them, for milk and butter sell readily all along the line of the road; but we don't sell any buttermilk, though, for we let the little pigs have that, and the little chickens, too. Jack had an experienced man to build a dairy house in the latest approved style.

"Jack, is there any buttermilk in the dairy house now?" he asked.

"I don't know, sir; but I'll go and inquire." So he went to the dairyman who had charge of the cows and the dairy house and found out that he had about half a barrel of buttermilk, just a little bit sour.

"Then have him bring several bucketfuls out to the little pigs."

The dairyman brought two big pails full of the buttermilk and poured it into a big sheet-iron receptacle, circular in form and about four inches deep. The little pigs came running up to the gate, crying like little pigs do when they smell food, and the gate was opened to let them get at it, and every one, of course, stuck his nose into the buttermilk clear up to his eyes, and they drank and pushed against each other until their stomachs actually looked swollen.

Evelyn stood and looked on, her eyes fairly sparkling with delight. She picked up several of the little fellows, who seemed to be used to being handled. They behaved, of course, like all little pet pigs.

"Oh, what a sight!" she exclaimed. "How I do wish mother could see it."

"And Mary, too," added Terry.

"Yes, for she, too, is very fond of pigs and chickens, and milch cows."

When the little pigs couldn't drink any more buttermilk they were driven back into the lot where the sows were, and then the big pans were shoved in so that the sows could drink the balance. Then they showed Evelyn where the ducks and geese were kept.

"Why in the world don't you let them run out and graze? Don't you know that ducks and geese live on grass just like cows and horses?"

"Yes, but we haven't arranged for that yet. These ducks and geese were bought by Jack, while we were up in New York and there is such a wide range that he has been afraid, to turn them out to go where they please. Then, the coyotes, too, are very fond of ducks and geese. A chicken can rise on the wing and get away, but fat ducks and geese can be caught before they can flap their wings three times. We will gradually build a wire mesh fence and turn them out so they will be protected from the coyotes and foxes."

After that Evelyn took a look at the dairy house. It had been built in first-class style by an experienced dairyman, and was large enough to manage the products of fifty cows if necessary, and Fred made the remark that he hoped to some day have that many Jersey cows on hand.

"Sister," put in Terry, "it won't cost a dollar a month more out here to keep a dozen milch cows than it would cost to keep a half dozen, for they can feed on the grass all day long, and at the present season the grass is very full of milk, and there are two of these cows whose yield of milk is so abundant that it is necessary to milk them at noon."

"Brother," she asked, "how is the grass in the winter? Does it dry up and turn brown like the grass in Colorado?"

"Yes, I believe it does; but the winters down here are at least two months shorter then they are up in Colorado. We expect to cut several hundred tons of hay while it is yet young and fresh and full of milk, and feed that to the milch cows during the winter. The beef cattle on the range can keep fat on the dry grass like those on all ranches do."

"Well, I'm glad to hear that," replied Evelyn, "for by that means you will have the abundant supply of milk that you are now getting."

She inspected every part of the dairy, particularly the arrangement for keeping all of the utensils perfectly clean.

Then she returned to the house, when Fred invited her to come out to the store.

"Why, goodness gracious!" she exclaimed. "Have you a store out here?"

"Yes; that building out there fronting on the wagon road is the store, and it does a particularly good business with the ranchmen who drive along the road."

"Well, well, well! What do you keep on sale there?"

"Oh, we've got an experienced salesman, who was raised in the business. He sells everything in the dry goods line and groceries and patent medicines. Of course, the dry goods are only such as ranchmen and farmers' wives need. If you want silks and fancy ribbons you would have to drive to Crabtree. Drummers come along nearly every day with samples of goods their employers have for sale, so if you want anything different from what we have in the store, you can order it through them."

"Well, I want to go in there and see the stock," so she went over with the boys, and Terry introduced her to the storekeeper as his sister. He was a single man, so he stared at her in open-eyed wonder, as she was perhaps the most beautiful woman he had ever seen in his life. She found that there was a little of almost everything that was kept in a country store. There was very little fancy goods, however, to be had there.