The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slave Narratives Vol. XIV. South Carolina,

Part 2, by Works Projects Administration

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Slave Narratives Vol. XIV. South Carolina, Part 2

A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From

Interveiws with Former Slaves.

Author: Works Projects Administration

Release Date: May 18, 2007 [EBook #21508]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES VOL. XIV. ***

Produced by Janet Blenkinship and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by the

Library of Congress, Manuscript Division)

| Eddington, Harriet | 1 |

| Edwards, Mary | 2 |

| Elliott, Rev. John B. | 3 |

| Elmore, Emanuel | 10 |

| Emmanuel, Ryer | 11, 17, 22 |

| Eubanks, Pen | 27 |

| Evans, Lewis | 30 |

| Evans, Phillip | 34 |

| Fair, Eugenia | 38 |

| Farrow, Caroline | 39, 42 |

| Feaster, Gus | 43, 48, 54 |

| Ferguson, Ann | 72 |

| Ford, Aaron | 74 |

| Foster, Charlotte | 80 |

| Franklin, John | 84 |

| Fraser, Emma | 87 |

| Frost, Adele | 88 |

| Gadsden, Amos | 91 |

| Gallman, Janie | 97 |

| Gallman, Lucy | 100 |

| Gallman, Simon | 103, 104 |

| Gary, Laurence | 106 |

| Gause, Louisa | 107 |

| Gibson, Gracie | 113 |

| Giles, Charlie | 115 |

| Gillison, Willis | 117 |

| Gilmore, Brawley | 120 |

| Gladdeny, Pick | 124 |

| Gladney, Henry | 129 |

| Glasgow, Emoline | 134 |

| Glenn, Silas | 136 |

| Glover, John | 138 |

| Godbold, Hector | 143 |

| Goddard, Daniel | 149 |

| Godfrey, Ellen | 153, 159, 161, 164 |

| Goodwater, Thomas | 166 |

| Grant, Charlie | 171 |

| Grant, Rebecca Jane | 177, 183 |

| Graves, John (Uncle Brack) | 187 |

| Greely, Sim | 190 |

| Green, Elijah | 195 |

| Green, W. M. | 200 |

| Grey, Adeline | 203 |

| Griffin, Fannie | 209 |

| Griffin, Madison | 212 |

| Grigsby, Peggy | 215 |

| Guntharpe, Violet | 216 |

| Hamilton, John | 221 |

| Hamlin, (Hamilton) Susan | 223, 226, 233 |

| Harp, Anson | 237 |

| Harper, Thomas | 240 |

| Harris, Abe | 242 |

| Harrison, Eli | 244 |

| Harvey, Charlie Jeff | 247 |

| Hasty, Eliza | 252 |

| Haynes, Dolly | 258 |

| Henderson, Liney | 261 |

| Henry, Jim | 266 |

| Herndon, Zack | 271 |

| Heyward, Lavinia | 276 |

| Heyward, Lucretia | 279 |

| Heywood, Mariah | 282 |

| Hill, Jerry | 289 |

| Hollins, Jane | 291 |

| Holmes, Cornelius | 294 |

| Horry, Ben | 298, 308, 316, 323 |

| Hughes, Margaret | 327 |

| Hunter, Hester | 331, 335, 341 |

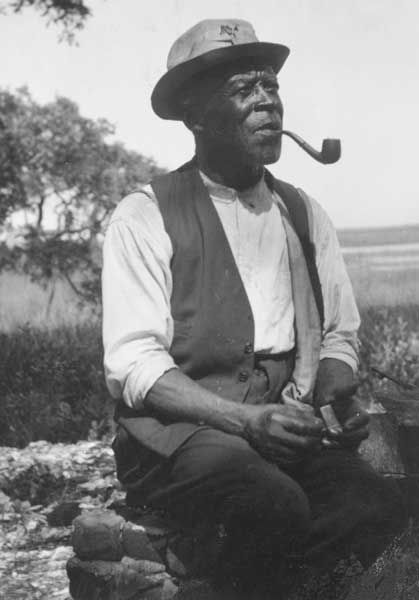

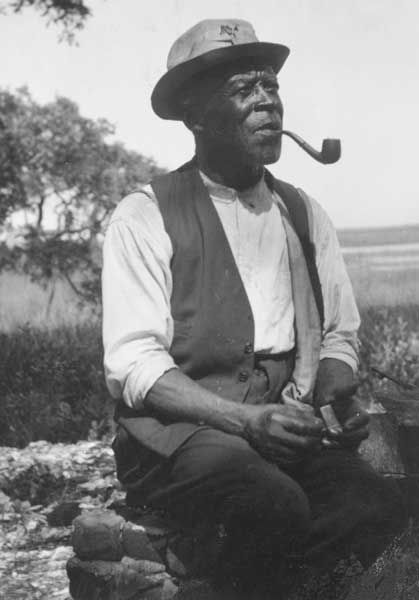

| Facing Page | |

| Ben Horry | 298 |

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

May 25, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES OF EX-SLAVES

"I was born in the town of Newberry, and was a servant of Major John P. Kinard. I married Sam Eddington. I was a Baker, daughter of Mike and Patience Baker. My mother was a free woman. She had her freedom before the war started; so I was not a slave. I worked on the farm with my mother when she moved back from town. Mama worked in town at hotels; then went back to the country and died. In war time and slavery time, we didn't go to school, 'cause there was no schools for the negroes. After the war was over and everything was settled, negro schools was started. We had a church after the war. I used to go to the white folks' Lutheran church and set in the gallery. On Saturday afternoons we was off, and could do anything we wanted to do, but some of the negroes had to work on Saturdays. In the country, my mother would card, spin, and weave, and I learned it. I could do lots of it."

Source: Harriet Eddington (86), Newberry, S.C.

Interviewer: G.L. Summer, Newberry, S.C. May 20, 1937.

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

June 16, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I was born in the section of Greenwood County called 'the promised land'. My parents were Henry and Julis Watkins. I married Frank Edwards when I was young. Our master, Marshall Jordon, was not so mean. He had lots o' slaves and he give 'em good quarters and plenty to eat. He had big gardens, lots of hogs and cattle and a big farm. My master had two children.

"Sometimes dey hunted rabbits, squirrels, possums and doves.

"De master had two overseers, but we never worked at night. We made our own clothes which we done sometimes late in evening.

"We had no school, and didn't learn to read and write, not 'till freedom come when a school started there by a Yankee named Backinstore. Later, our church and Sunday school was in de yard.

"We had cotton pickings, cornshuckings and big suppers. We didn't have to work on Christmas.

"One of de old-time cures was boiling fever-grass and drinking de tea. Pokeberry salad was cooked, too. A cure for rheumatism was to carry a raw potato in the pocket until it dried up.

"I had 11 children and 8 grandchildren.

"I think Abe Lincoln was a great man. Don't know much about Jeff Davis. Booker Washington is all right.

"I joined church in Flordia, the Methodist church. I was 50 years old. I joined because they had meetings and my daughter had already joined. I think all ought to join de church."

Source: Mary Edwards (79), Greenwood, S.C.

Interviewed by: G.L. Summer, Newberry, S.C. (6/10/37)

Project #1655

Stiles M. Scruggs

Columbia, S.C.

A SON OF SLAVES CLIMBS UP.

The Rev. John B. Elliott, A.B.A. A.M., D.D., 1315 Liberty Hill Avenue, Columbia, S.C., is the son of slaves. He was born at Mount Olive, N.C., in 1869, and missed being a slave by only four years. His college degrees were won at Shaw University, Raleigh, N.C., and the degree of Doctor of Divinity was conferred on him by Allen University of Columbia, S.C.

Sitting on the parsonage piazza recently, the Rector of St. Anna's Episcopal Church talked about his struggle for education, and his labors up from slavery.

"I was born at Mount Olive, N.C., the son of Soloman Elliott and Alice (Roberts) Elliott. They were slaves when they married, and I escaped bondage by only four years, since slaves were not freed in the South, until 1865.

"My father was owned by Robert W. Williams, of Mount Olive, and he was the most highly prized Negro in the vicinity. He was a natural carpenter and builder. Often he would go to the woods and pick out trees for the job in hand. Some of the houses he built there are standing today. Mother was equally trained and well equipped to make a home and keep it neat and clean. When they were free in 1865, half the community was eager to employ them and pay them well for their services. And, when I came along, they were living in their own house and prospering.

"I chose a religious career when quite a boy, and, when I was ready for college, I was much pleased. I finished at Shaw University at Raleigh, took a year's study at Columbia University in New York and then finished a religious course at the Bishop Payne Divinity School at Petersburg, Virginia, where most[Pg 4] of the colored clergymen of the Episcopal Church are finished. After I felt that I was fairly well fitted to begin my clerical work, I chose South Carolina as my field.

"My first assignment was at Waccamaw Neck, a little below Georgetown, S.C., and a big industrial center. There the Negro population is keen for wine and whiskey. One of the men whom I was interested in, was pretty tipsy when I called, and, as I sat and talked with him, he said: 'You're drunk, too.' This surprised me, and I asked him why he thought so. 'Well, you got your vest and collar on backwards, so you must be drunk!'

"Since, I have had pastorates at Aiken, Peak, Rock Hill, and Walterboro. From Walterboro I came to Columbia as pastor of St. Anna's Episcopal Church and the missions of Ann's at New Brookland and St. Thomas at Eastover. I presume I have done pretty well in this field, since the Rt. Rev. Bishop Kirkman G. Finlay, D.D., appointed me arch-deacon for Negro work in upper South Carolina.

"As I was coming away from the Bishop's office, I was accompanied by another colored rector, who had very short legs. I am six feet, four inches in height, and he looked up at me as we walked along and asked quizzically: 'How long should a man's legs be?' I smiled and told him I thought, perhaps, every man should have legs long enough to reach to the ground. Yes, of course, we laughed at each other, but my argument won, because Bishop Finlay is about six feet, three inches, and I told my short friend: 'When Bishop Finlay and I talk, we are able to look each other in the eye on the level.'

"I married Susan McMahan, a colored school teacher, and the Lord has blessed us with a son, John B. Jr., a fine wood-worker, like his grandfather was, and two sweet daughters. Alice, the older one, is a teacher in the public schools of Columbia and Annie is a student. Our home life has always been[Pg 5] pleasant and unusually sunny.

"I had one very humorous experience three years ago when I was invited to deliver an address near Mount Olive, N.C., to a convention of young people. Arriving about 10 o'clock that day, I was met by a citizen who told me he was assigned to introduce me that evening. As we rode along, I cautioned him not to boost me too highly. He said little.

"When the big, and, I may say, expectant audience was seated that night, he arose and seemed much embarrassed, ultimately saying: 'Ladies and gentlemen, I have an unpleasant duty to perform this evening.' Then, pointing at me, he went on: 'I don't know this man, much. Fact is, I only know two things about him. One is, he has never been in jail; and the other is, I never could figure why.'

"No, I am not related to the late Robert Bruce Elliott by ties of consanguinity. He was successively twice a member of Congress from South Carolina, and a member and Speaker of the South Carolina House of Representatives in 1876. Perhaps these honors came to him because he had a good education before he met the opportunity for service.

"When I think of the '60's-'70's period, I am surprised that recent slaves, suddenly placed in administrative positions of honor and trust, did as well as they did.

"In the seventy-two years since slavery, I have noted much improvement along the road, and I am sure that our nation has far less discord now, than it had when I was a small lad. And, when one can note progress in our march toward the light, I guess that ought to be sufficient for my optimism."

Project 1885-1

Folklore

Spartanburg, Dist. 4

Dec. 23, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

EX-SLAVE STORIES

EMANUEL ELMORE.

"I was born on June 20th and I remember when the war broke out, for I was about five years old. We lived in Spartanburg County not far from old Cherokee ford. My father was Emanuel Elmore, and he lived to be about 90 years old.

"My marster was called by everybody, Col. Elmore, and that is all that I can remember about his name. When he went to the war I wanted to go with him, but I was too little. He joined the Spartanburg Sharp Shooters. They had a drill ground near the Falls. My pa took me to see them drill, and they were calling him Col. Elmore then. When I got home I tried to do like him and everybody laughed at me. That is about all that I remember about the war. In those days, children did not know things like thay do now, and grown folks did not know as much either.

"I used to go and watch my father work. He was a moulder in the Cherokee Iron Works, way back there when everything was done by hand. He moulded everything from knives and forks to skillets and wash pots. If you could have seen pa's hammer, you would have seen something worth looking at. It was so big that it jarred the whole earth when it struck a lick. Of course it was a forge hammer, driven by water power. They called the hammer 'Big Henry'. The butt end was as big as an ordinary telephone pole.

"The water wheel had fifteen or twenty spokes in it, but when it was running it looked like it was solid. I used to like to sit and watch that old wheel. The water ran over it and the more water came over, the more power the wheel gave out.[Pg 7]

"At the Iron Works they made everything by hand that was used in a hardware store, like nails, horse shoes and rims for all kinds of wheels, like wagon and buggy wheels. There were moulds for everything no matter how large or small the thing to be made was. Pa could almost pick up the right mould in the dark, he was so used to doing it. The patterns for the pots and kettles of different sizes were all in rows, each row being a different size. In my mind I can still see them.

"Hot molten iron from the vats was dipped with spoons which were handled by two men. Both spoons had long handles, with a man at each handle. The spoons would hold from four to five gallons of hot iron that poured just like water does. As quick as the men poured the hot iron in the mould, another man came along behind them and closed the mould. The large moulds had doors and the small moulds had lids. They had small pans and small spoons for little things, like nails, knives and forks, When the mould had set until cold, the piece was prized out.

"Pa had a turn for making covered skillets and fire dogs. He made them so pretty that white ladies would come and give an order for a 'pair of dogs', and tell him how they wanted them to look. He would take his hammer and beat them to look just that way.

"Rollers pressed out the hot iron for machines and for special lengths and things that had to be flat. Railroad ties were pressed out in these rollers. Once the man that handled the hot iron to be pressed through these rollers got fastened in them himself. He was a big man. The blood flew out of him as his bones were crushed, and he was rolled into a mass about the thickness and width of my hand. Each roller weighed about 2,000 pounds.[Pg 8]

"The man who got killed was named Alex Golightly. He taught the boys my age how to swim, fish and hunt. His death was the worst thing that had happened in the community. The man who worked at the foundry, made Alex a coffin. It had to be made long and thin because he was mashed up so bad. In those days coffins were nothing but boxes anyway, but Alex's coffin was the most terrible thing that I have ever seen. I reckon if they had had pretty coffins then like they do now, folks would have bought them to sleep in.

"Hundreds went to Alex's funeral, white and black, to see that long narrow coffin and the grave which was dug to fit it. On the way to the graveyard, negroes sang songs, for Alex was a good man. They carried him to the Cherokee graveyard on the old Smith Ford Road, and there they buried him. My father helped to build the coffin and he helped haul him to the graveyard. Pa worked at the Iron Foundry until he was very old. He worked there before I was ever born.

"My father was sold four times during slavery. When he was brought to Virginia he was put on the block and auctioned off for $4,000. He said that the last time he was sold he only brought $1,500. He was born in Alabama. When he was bought he was carried from Alabama to Virginia. It was Col. Elmore who took him. He wanted to go to Alabama again, so Col. Elmore let a speculator take him back and sell him. He stayed there for several years and got homesick for South Carolina. He couldn't get his marster to sell him back here, so he just refugeed back to Col. Elmore's plantation. Col. Elmore took him back and wouldn't let anybody have him.

"Pa married twice, about the same time. He married Dorcas[Pg 9] Cooper, who belonged to the Coopers at Staunton Military Academy. I was the first child born in Camden. She had sixteen children. I was brought to Spartanburg County when I was little. Both ma and pa were sold together in Alabama. The first time pa came to South Carolina he married a girl called Jenny. She never had any children. When he went to Alabama, Dorcas went with him, but Jenny stayed with Col. Elmore. Of course, pa just jumped the broom for both of them.

"When pa left Alabama to refugee back, he had to leave Dorcas. They did not love their marster anyway. He put Dorcas up on the block with a red handkerchief around her head and gave her a red apple to eat. She was sold to a man whose name I have forgotten. When they herded them she got away and was months making her way back to South Carolina. Those Africans sure were strong. She said that she stayed in the woods at night. Negroes along the way would give her bread and she would kill rabbits and squirrels and cook and eat in the woods. She would get drunk and beat any one that tried to stop her from coming back. When she did get back to Col. Elmore's place, she was lanky, ragged and poor, but Col. Elmore was glad to see her and told her he was not going to let anybody take her off. Jenny had cared so well for her children while she was off, that she liked her. They lived in the same house with pa till my mother died.

"Col. Elmore said that negroes who were from Virginia and had African blood could stand anything. He was kind to ma. He fed her extra and she soon got fat again. She worked hard for Col. Elmore, and she and pa sure did love him. One time a lot of the negroes in the quarter got drunk and ma got to fighting all of them.[Pg 10] When she got sobered up she was afraid that Col Elmore was going to send her back to Alabama; so she went and hid in the woods. Pa took food to her. In about a month Col. Elmore asked where she was, and pa just looked sheepish and grinned. Col. Elmore told pa to go and bring her back, for he said he was tired of having his rations carried to the woods; so ma came home. She had stayed off three months. She never felt well anymore, and she died in about three more months. Pa and Jenny kept us till we got big and went off to ourselves.

"Jenny was born and raised in South Carolina, and she was good to everybody and never fought and went on like ma did. Ma liked her and would not let anybody say anything against her. She was good to pa till he died, a real old man. Jenny never had any children. She was not old when she died, but just a settled woman. We felt worse over her death than we did over ma's, because she was so good to us and had cared for us while ma and pa were in Alabama; then she was good to us after Dorcas died and when she hid in the woods.

"It seems that folks are too tender now. They can't stand much. My ma could stand more than I can. My children can't stand what I can right now."

Source: Emanuel Elmore (77). Sycamore St., Gaffney, S.C.

Interviewer: Caldwell Sims, Union, S.C. 11/16/37

Code No.

Project, 1885-(1)

Prepared by Annie Ruth Davis

Place, Marion, S.C.

Date, December 16, 1937

MOM RYER EMMANUEL

Ex-Slave, Age 78

"Oh, my Lord, child, I ain' know nothin bout slavery time no more den we was just little kids livin dere on de white people plantation. I was just a little yearlin child den, I say. Been bout six years old in slavery time. Well, I'll say dat I bout 80 some odds, but I can' never seem to get dem odds together. I was a big little girl stayin in old Massa yard in dem days, but I wasn' big enough to do nothin in de house no time. My old Massa been Anthony Ross en he had set my age down in de Bible, but my old Missus, she dead en I know dem chillun wouldn' never know whe' to say dat Bible at dese days. Old Miss, she been name Matt Ross. I wish somebody could call up how long de slaves been freed cause den dey could call up my age fast as I could bat my eyes. Say, when de emancipation was, I been six years old, so my mammy tell me. Don' know what to say dat is, but I reckon it been since freedom."

"I been born en bred right over yonder to dat big patch of oak trees bout dat house what you see after you pass de white people church cross de creek dere. De old man Anthony Ross, he been have a good mind to his colored people all de time. Yes, mam, my white folks was proud of dey niggers. Um, yes'um, when dey used to have company to de big house, Miss Ross would bring dem to de door to show dem us chillun. En[Pg 12] my blessed, de yard would be black wid us chillun all string up dere next de door step lookin up in dey eyes. Old Missus would say, 'Ain' I got a pretty crop of little niggers comin on?' De lady, she look so please like. Den Miss Ross say, 'Do my little niggers want some bread to gnaw on?' En us chillun say, 'Yes'um, yes'um, we do.' Den she would go in de pantry en see could she find some cook bread to hand us. She had a heap of fine little niggers, too, cause de yard would be black wid all different sizes. Won' none of dem big enough to do nothin. No, mam, dey had to be over 16 year old fore old Massa would allow dem to work cause he never want to see his niggers noways stunt up while dey was havin de growin pains. Den when dey was first grow up, dey would give some of dem a house job en would send de others in de field to mind de cows en de sheep en bring dem up. Wouldn' make dem do no heavy work right to start wid. But dem what was older, dey had to work in de field. I reckon dey would be workin just bout like dey is now from sunrise in de mornin till sunset in de evenin."

"Yes, honey, I been come here under a blessin cause my white folks never didn' let dey colored people suffer no time. Always when a woman would get in de house, old Massa would let her leave off work en stay dere to de house a month till she get mended in de body way. Den she would have to carry de child to de big house en get back in de field to work. Oh, dey had a[Pg 13] old woman in de yard to de house to stay dere en mind all de plantation chillun till night come, while dey parents was workin. Dey would let de chillun go home wid dey mammy to spend de night en den she would have to march dem right back to de yard de next mornin. We didn' do nothin, but play bout de yard dere en eat what de woman feed us. Yes'um, dey would carry us dere when de women would be gwine to work. Be dere fore sunrise. Would give us three meals a day cause de old woman always give us supper fore us mammy come out de field dat evenin. Dem bigger ones, dey would give dem clabber en boil peas en collards sometimes. Would give de little babies boil pea soup en gruel en suck bottle. Yes, mam, de old woman had to mind all de yearlin chillun en de babies, too. Dat all her business was. I recollects her name, it been Lettie. Would string us little wooden bowls on de floor in a long row en us would get down dere en drink just like us was pigs. Oh, she would give us a iron spoon to taste wid, but us wouldn' never want it. Oh, my Lord, I remember just as good, when we would see dem bowls of hot ration, dis one en dat one would holler, 'dat mine, dat mine.' Us would just squat dere en blow en blow cause we wouldn' have no mind to drink it while it was hot. Den we would want it to last a long time, too. My happy, I can see myself settin dere now coolin dem vitals (victuals)."[Pg 14]

"Like I speak to you, my white folks was blessed wid a heap of black chillun, but den dere been a odd one in de crowd what wasn' noways like dem others. All de other chillun was black skin wid dis here kinky hair en she was yellow skin wid right straight hair. My Lord, old Missus been mighty proud of her black chillun, but she sho been touches bout dat yellow one. I remember, all us chillun was playin round bout de step one day whe' Miss Ross was settin en she ax dat yellow child, say, 'Who your papa?' De child never know no better en she tell her right out exactly de one her mammy had tell her was her papa. Lord, Miss Ross, she say, 'Well, get off my step. Get off en stay off dere cause you don' noways belong to me.' De poor child, she cry en she cry so hard till her mammy never know what to do. She take en grease her en black her all over wid smut, but she couldn' never trouble dat straight hair off her noway. Dat how-come dere so much different classes today, I say. Yes, mam, dat whe' dat old stain come from."

"My mammy, she was de housewoman to de big house en she say dat she would always try to mind her business en she never didn' get no whippin much. Yes, mam, dey was mighty good to my mother, but dem other what never do right, dey would carry dem to de cow pen en make dem strip off dey frock bodies clean to de waist. Den dey would tie dem down to a log en paddle dem wid a board. When dey would whip de men, de boards would often times have nails in dem. Hear[Pg 15] talk dey would wash dem wid dey blood. Dat first hide dey had, white folks would whip it off dem en den turn round en grease dem wid tallow en make dem work right on. Always would inflict de punishment at sunrise in de mornin fore dey would go to work. Den de women, dey would force dem to drop dey body frock cross de shoulders so dey could get to de naked skin en would have a strap to whip dem wid. Wouldn' never use no board on de women. Oh, dey would have de lot scatter bout full of dem what was to get whip on a mornin."

"You see, de colored people couldn' never go nowhe' off de place widout dey would get a walkin ticket from dey Massa. Yes, mam, white folks would have dese pataroller walkin round all bout de country to catch dem colored people dat never had no walkin paper to show dem. En if dey would catch any of dem widout dat paper, dey back would sho catch scissors de next mornin."

"Well, I don' know as de white folks would be meanin to kill any of dey niggers, but I hear talk dey would whip dem till dey would die some of de time en would bury dem in de night. Couldn' bury dem in de day cause dey wouldn' have time. When dey would be gwine to bury dem, I used to see de lights many a time en hear de people gwine along singin out yonder in dem woods just like dey was buryin buzzards. Us would set down en watch dem gwine along many a night wid dese great big torches of fire. Oh, dey would have fat lightwood torches. Dese here big hand splinters. Had to[Pg 16] carry dem along to see how to walk en drive de wagon to haul de body. Yes, child, I been here long enough to see all dat in slavery time. All bout in dese woods, you can find plenty of dem slavery graves dis day en time. I can tell bout whe' dere one now. Yes, mam, dere one right over yonder to de brow of de hill gwine next to Mr. Claussens. Can tell dem by de head boards dere. Den some of de time, dey would just drop dem anywhe' in a hole along side de woods somewhe' cause de people dig up a skull right out dere in de woods one day en it had slavery mark on it, dey say. Right over dere cross de creek in dem big cedars, dere another slavery graveyard. People gwine by dere could often hear talk en couldn' never see nothin, so dey tell me. Hear, um—um—um, en would hear babies cryin all bout dere, too. No'um, can' hear dem much now cause dey bout to be wearin out. I tell you, I is scared every time I go along dere. Some of dem die wicked, I say."

Source: Ryer Emmanuel, colored, age 78, Claussens, S.C.

Personal interview by Annie Ruth Davis, Dec., 1937.

Project 1885-(1)

Prepared by Annie Ruth Davis

Place, Marion, S.C.

Date, December 26, 1937

MOM RYER EMMANUEL

Ex-Slave, Age 78

"Well, how you feelin dis mornin, honey? I had tell Miss Sue dat I would be keepin a eye out dat door dere en when I is see a car stop up to de house, I would try en make it up dere dis mornin. Yes, mam, Miss Sue tell me you was comin today en I promise her I would be up dere, but I ain' been feelin so much to speak bout dis mornin. Den you see, I know I gwine be obliged to run down to de woods en fetch me up some wood en kindlin fore night fall. I been 'spect to make Koota break me up some splinters, but he ain' no count worth nothin. Yes, mam, he my grandson. Cose I tries to knock bout somewhe' en let me get out in de cotton patch, I can put in a good sturdy job any day. You see, my eyes does be pretty good cause dey got on dey second glove, I say. Can see good to my age. But oh, my Lord, right in my chest here, it does thump sometimes just like a drum beatin in dere en I can' never stand to hurry en walk hard no more dese days."

"No, mam, it don' bother me noways to leave dat door open. I keeps it dat way bout all de time, so as I can look out en see what gwine along de road dere. What de matter, honey, you don' loves to smell dem chitlin I got boilin dere on de stove? I hear some people say dey can' stand no chitlin scent nowhe' bout dem, but I loves dem so much dat it does make my mouth[Pg 18] run water to think bout how me en Koota gwine enjoy dem dis evenin. No, mam, us don' never eat us heavy meal till dat sun start gwine down behind dem trees cross de creek yonder. You see, I does keep some 'tatoes roastin dere in de coals on de hearth en if us belly sets up a growlin twixt meals, us just rakes a 'tatoe out de ashes en breaks it open en makes out on dat. My God, child, I think bout how I been bless dat I ain' never been noways scornful bout eatin chitlins. Yes, mam, when I helps up dere to de house wid hog killin, Mr. Moses, he does always say for me to carry de chitlin home to make me en Koota a nice pot of stew."

"I tellin you, when us been chillun comin up, people sho never live like dey do dis day en time. Oh, I can remember just as good when I used to go dat Hopewell Presbyterian Church cross de creek dere. Yes, mam, dat been de white people slavery church en dat dey slavery graveyard what settin right dere in front de church, too. Dat sho a old, old slavery time church, I say. Massa Anthony Ross would make us go dere to preachin every Sunday en dey was mighty strict bout us gwine to prayer service, too. Us would go up dem steps in dat little room, what been open out on de front piazza to de church, en set up in de gallery overhead en de white folks let down dere below us. Yes, mam, dat whe' de colored people went to church in dem days en some of dem go dere till dey die cause dat whe' dey been join de church. Some of dem does go dere often times dese days,[Pg 19] too, when de white people axes dem to sing to dey church. I remember, when I been baptize dere, I was just a little small child. Oh, de white preacher baptized all us little niggers dere. Old Massa, he tell all his hands to carry dey chillun up dere en get dem baptized. Oh, my happy, dey been fix us up dat day. Put on us clean homespuns en long drawers, dat been hang down round us ankles like boots, en all us get a new bonnet dat day. I recollects, dey would march us right up to de front of de church en de preacher would come down to whe' we was standin wid a basin of water in one hand en a towel in de other hand. He would take one of us chillun en lay he wet hand on dey head en say, 'I baptize dee in de name of, etc.' Den dat one would have to get back en another one would step up for dey turn. De preacher, he would have a big towel to wipe his hands wid en every child's mammy would be standin right behind hind dem wid a rag to wipe de (drain) dren water out dey eyes."

"Oh, my Lord, when de Yankees come through dere, I hear dem say it was de Republicans. Mr. Ross had done say dat he hear talk dat dey was comin through en he tell his niggers to hurry en hide all de plantation rations. Yes, mam, dey dig cellars under de colored people houses en bury what meat en barrels of flour dey could en dat what dey couldn' get under dere, dey hide it up in de loft. Mr. Ross say, 'Won' none of[Pg 20] dem damn Yankees get no chance to stick dey rotten tooth in my rations.' We say, 'Ma, you got all dese rations here en we hungry.' She say, 'No, dem ration belong to boss en you chillun better never bother dem neither.' Den when Mr. Ross had see to it dat dey had fix everything safe, he take to de swamp. Dat what my mammy say cause he know dey wasn' gwine bother de womens. Lord, when dem Yankees ride up to de big house, Miss Ross been scared to open her mouth cause de man was in de swamp. No, child, dey didn' bother nothin much, but some of de rations dey get hold of. Often times, dey would come through en kill chickens en butcher a cow up en cook it right dere. Would eat all dey wanted en den when dey would go to leave, dey been call all de little plantation niggers to come dere en would give dem what was left. Oh, Lord, us was glad to get dem vitals, too. Yes, mam, all dey had left, dey would give it to de poor colored people. Us been so glad, us say dat us wish dey would come back again. Den after dey had left us plantation, dey would go some other place where dere was another crowd of little niggers en would left dem a pile of stuff, too. Old Massa, he been stay in de swamp till he hear dem Yankees been leave dere en den he come home en would keep sendin to de colored people houses to get a little bit of his rations to a time. Uncle Solomon en Sipp en Leve, dey been eat much of boss' rations dey wanted cause[Pg 21] dey been know de Yankees was comin back through to free dem. But my mammy, she was a widow woman en old man Anthony Ross never left nothin to her house."

"I tell you, honey, some of de colored people sho been speak praise to dem Yankees. I don' know how-come, but dey never know no better, I say. Dey know en dey never know. One old man been ridin one of dese stick horses en he been so glad, he say, 'Thank God! Thank God!"

Source: Ryer Emmanuel colored, age 78, Claussens, S.C.

Personal interview by Annie Ruth Davis, Marion, S.C.

December, 1937.

Code No.

Project, 1885-(1)

Prepared by Annie Ruth Davis

Place, Marion, S.C.

Date, January 7, 1938

MOM RYER EMMANUEL

Ex-Slave, 78 Years

"Good evenin, child. How you is? How Miss Sue gettin along over dere to Marion? I hope she satisfied, but dere ain' nowhe' can come up to restin in your own home, I say. No, Lord, people own home don' never stop to cuss dem no time. Dere Koota's mamma all de time does say, 'Ma, ain' no need in you en Booker stayin over dere by yourself. Come en live wid us.' I say, 'No, child. Father may have, sister may have, brother may have, en chillun may have, but blessed be he dat have he own.' I tell all my chillun I rather stay here under my own roof cause when I takes a notion, I can go in en bake me a little hoecake en draw me a pot of coffee en set down to eat it in satisfaction."

"After you was gone de other day, I thought bout right smart to speak to you, but when I gets tired, I just get all fray up somehow. My sister, she come to see me Sunday en I had dem all laughin bout what I say dat I had tell you. My sister, she make out like she don' know nothin bout dem olden times. Her husband, he done gone en die en she out lookin round for another one. Reckon dat what ails her. I tell her, I ain' see none nowhe' dat I would be pleased to take in. But I don' care what she say, us sho been here in slavery time cause my mother didn' have but one free born child en dat one come here a corpse."[Pg 23]

"I remember, Ma used to tell we chillun bout how dey couldn' never do nothin in slavery time, but what de white folks say dey could do. I say, 'If I been big enough in dem days, I would sho a let out a fight for you.' You see, I was a little small child den en I never know no better den to speak dat way."

"My mother, she was de house woman to de big house in slavery time, but she never didn' get no money for what she been do. No, mam, white folks never didn' pay de poor colored people no money in dat day en time. See, old boss would give dem everything dey had en provide a plenty somethin to eat for dem all de time. Yes'um, all de niggers used to wear dem old Dutch shoes wid de brass in de toes en de women, dey never didn' have nothin 'cept dem old coarse shoes widout no linin. Couldn' never wear dem out. Yes'um, dey always give us a changin of homespuns, so as to strip on wash day en put on a fresh one."

"Den I recollects we chillun used to ax us mammy whe' us come from en she say, 'I got you out de hollow log.' Well, just like I tell you, slavery chillun had dey daddy somewhe' on de plantation. Cose dey had a daddy, but dey didn' have no daddy stayin in de house wid dem. White folks would make you take dat man whe' if you want him or no. Us chillun never didn' know who us daddy been till us mammy point him out cause all us went in Massa Anthony Ross' name. Yes, mam, all us had a different daddy, so my mammy say."[Pg 24]

"Who dat come here wid you? Lord, dat don' look like no wife. How long you is been married, honey? You ain' say so. Look like you is just bloomin, I say."

"Oh, I tell you, I see a heap of things in dem days, but I ain' got my studyin cap on right now en I can' call up nothin right sharp. Us never know nothin bout us was gwine get free in dat day en time. Us was same as brutes en cows back dere cause us been force to go by what white man say all de time. Oh, dey would beat de colored people so worser till dey would run away en stay in de swamp to save dey hide. But Lord a mercy, it never do no good to run cause time dey been find you was gone, dey been set de nigger dog on you. Yes, mam, dey had some of dese high dogs dat dey call hounds en dey could sho find you out, too. Oh, dem hounds would sho get you. Don' care whe' you was hidin, dem dogs would smell you. If you been climb up a tree, de dog would trail you right to de foot of dat tree en just stand up en howl at you. Dey would stand right dere en hold you up de tree till some of de white folks been get dere en tell you to come down out de tree. Den if you never do like dey say, dey would chop de tree down en let you fall right in de dog's mouth. Would let de dog bite you en taste your blood, so dey could find de one dey was lookin for better de next time. Yes, mam, white people would let de dog gnaw you up en den dey would grease you en carry you home to de horse[Pg 25] lot whe' dey would have a lash en a paddle to whip you wid. Oh, dey would have a swarm of black people up to de lot at sunrise on a mornin to get whip. Would make dem drop dey body frock en would band dem down to a log en would put de licks to dem. Ma was whip twice en she say dat she stay to her place after dat. I hear talk dey give some of dem 50 lashes to a whippin. Dat how it was in slavery time. Poor colored people couldn' never go bout en talk wid dey neighbors no time widout dey Massa say so. I say, 'Ma, if dey been try to beat me, I would a jump up en bite dem.' She say, 'You would get double portion den.' Just on account of dat, ain' many of dem slavery people knockin bout here now neither, I tell you. Dat first hide dey had, white folks just took it off dem. I would a rather been dead, I say. I remember, we chillun used to set down en ax Ma all bout dis en dat. Say, 'Ma, yunnah couldn' do nothin?' She say, 'No, white people had us in slavery time.'

"My God a mercy, I think now de best time to live in cause I ain' gettin no beatin dese days. If I had been big enough to get whip in slavery time, I know I would been dead cause I would been obliged to fight dem back en dey would kill folks for dat in dem days. If anybody hurt me, dey got to hurt back again, I say. Cose us had us task to do in dem days, but us never didn' have to bother bout huntin no rations en clothes[Pg 26] no time den like de people be burdened wid dese days. I tell you, what you get in dese times, you got to paw for it en paw hard, but ain' nobody else business whe' you do it or no."

"Oh, de young people, dey ain' nothin dis day en time. Ain' worth a shuck no time. De old ones can beat dem out a hollow anywhe'. Ain' no chillun raise in dese days, I say. After freedom come here, I know I been hired out to white folks bout all de time en, honey, I sho been put through de crack. Lord, I had a rough time. Didn' never feel no rest. Dat how-come I ain' get all my growth, I say."

Source: Mom Ryer Emmanuel, colored, 78 years, Claussens, S.C.

Personal interview by Annie Ruth Davis, Marion, S.C.

[HW: See ES XVII, MS. #14.]

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg—Dist. 4

May 18, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"White folks. I sho nuff did ride wid de 'Red Shirts' fer Marse Hampton. Dar was two other darkies what rid wid us. Dey is bof daed now. One was Jack Jones, and de t'othern I does not recollect his name. Him and Jack is both daed. Dat leave me de onliest living one what rid in de company.

"I rid in de company wid Marse Jimmie Young and he was de Cap'un. He live out yonder at Sardis Church. Ev'ybody know Marse Jimmie. He ain't quite as aged yet as I bees. Mr. J.T. Sexton, he rid from up around Cross Keys, he got de 'hole in de wall' and I calls on him yit, and us talks over de olden days. Miss Bobo's husband, he rid in Marse Jimmie's company. (Mr. Preston B. Bobo) Our company camped at de ole Brick church out whar de mansion set now. It has allus been called de Lower Fairforest Baptist Church, whar de white folks still goes, 'cept de done move de church down on de new road, further from de mansion and de ole graveyard. I lows dat you knows I is speaking o' de new mansion—Mr. Emslie Nicholson's house on de forest at de Shoals. I is got memory, but I ain't got no larning; dat I is proud of, kaise I is seed folks wid larning dat never knowed nothing worth speaking about. All de way 'fru', I is done tuck and stuck to my white folks—de Democratic white folks, dat I is.

"Sho was a pretty sight to see 'bout a hun'ded mens up on fine horses wid red shirts on. I still sees dem in my mind clear as day. Our red shirts fastened wid a strong band 'round de waist. Dar wasn't nar'y speck o' white to be seed no whars on 'em.[Pg 28] Dey was raal heavy and strong. Fact, dey was made from red flannel, and I means it was sho 'nough flannel, too. I had done kept one o' mine here till times got hard and den I tuck and tore it up fer me a undershirt, here past it been two winters when it got so cold.

"One night us sot up all night and kept a big fire. Next morning it was de biggest frost all over de ground; but us never got one mite cold. De good white ladies of de community made our red shirts fer us. I 'spects Marse Jimmie ken name some fer you.

"I got eve'y registration ticket in my house, and I still votes allus de democratic ticket. I has longed to de Democratic club ever since de red shirt days and I has voted dat way all de time. I was jes' turn't seventeen when I jined de Red Shirts and got into de Democratic Club, and I has been in it ever since. It ain't gwine out neither.

"I sho seed Hampton speak from Dr. Culp's porch. I voted fer him. At dat time, I lived on de Keenan place. Marse Jimmie Young, he de overseer fer Mr. Keenan. Mr. Charles Ray owns and lives on it now. Dat brick church straight up de road from de Keenan place; straight as a bee line. Dat whar us met most o' de time fer de Red Shirt gatherings. Our Red Shirt Club was called de 'Fairforest' club atter de Lower Fairforest white folks Baptist church. De church has allus sot on de banks o' Fairforest Creek. Atter us got organized, I used to tote our flag. I was de onliest darky dat toted it.

"I is done handed you a few names: dey is all Democratic names. Lots of dem 'scapes my knowledge, it has all been so long ago. Dar was Mr. Gilmer Greer. Miss Gilmer Blankenship what lives out dar, she his niece. Mr. John Sims 'nother white man I members.[Pg 29] Dar was lots o' companies in dis county, but I does not recall how many.

"Captain Jimmie Young would allus notify when dar was to be a meeting. Us darkies dat 'longed 'ud go and tell de white mens to come to de church. Us met sometime right 'fo de 'lection and all de companies come together at de ole courthouse dat stood right whar de new one is now.

"Robinson's Circus come to Union. De circus folks gib everbody a free ticket to de circus dat 'longed to de Democratic Club. Dey let all de scalawag niggers in fer registration tickets dat de Republicans had done give dem to vote fer Chamberlain. Dem niggers wanted to go to de circus wu'se dan dey wanted to do anything else. Dey never dre'mt dat dey was not a going to git to vote like de carpetbaggers, and de scalawags had done tole dem to do. Fact is, dey never much cared jes' since de got in de circus. Dem dat wanted de registration tickets back when de come out, never seed nobody to git 'em from nohows. Robinson's Circus was so big dat dey never showed it all in Union, but what dey had was out on McClure's field. It wasn't no houses dar den, and, o' course, dar wasn't no mill no whar about Union in dem days. All de tents dat was staked was staked in McClure's ole field over on 'Tosch' Branch. In dem days, dat field was de biggest territory in de clear around Union. Atter dat, all de Red Shirts met on de facade in front o' de courthouse. Mos' all de mens made a speech. Another darky sung a song like dis: 'Marse Hampton was a honest man; Mr. Chamberlain was a rogue'—Den I sung a song like dis: 'Marse Hampton et de watermelon, Mr. Chamberlain knawed de rine.' Us jest having fun den, kaise us had done 'lected Marse Hampton as de new governor of South Ca'linia."

Source: "Uncle Pen" Eubanks, Hampton Ave. Union, S.C. (age 83)

Interviewer: Caldwell Sims, Union, S.C. (5/4/37)

Project #1655.

W. W. Dixon,

Winnsboro, S. C.

LEWIS EVANS

EX-SLAVE 96 YEARS

Lewis Evans lives on the lands of the estate of the late C.L. Smith, about ten miles southwest of Winnsboro, S.C. The house is a two-room frame structure, with a chimney in the center. He has the house and garden lot, free of rent, for the rest of his life, by the expressed wish of Mr. Smith before his demise. The only other occupant is his wife, Nancy, who is his third wife and much younger than Lewis. She does all the work about the home. They exist from the produce of the garden, output of fowls, and the small pension Lewis receives. They raise a pig each year. This gives them their meat for the succeeding year.

"Who I b'long to? Where was I born? White folks tell me I born after de stars fell, (1833), but maybe I too little to 'member de day. Just have to go by what I hear them say. Think it was 'bout 1841. All accounts is, I was born a slave of Marster John Martin, near Jenkinsville. Old Mistress, his wife, named Miss Margaret. All I can 'member 'bout them is dis: They had 'bout fifteen slaves, me 'mongst them. His daughter married a doctor, Doctor Harrison. I was sold to Maj. William Bell, who lived 'bout ten or twelve miles from old Marster. I's a good size boy then. Maj. Bell had ten families when I got dere. Put me to hoein' in de field and dat fall I picked cotton. Next year us didn't have cotton planters. I was took for one of de ones to plant de cotton seed by drappin' de seed in de drill. I had a bag 'round my neck, full of seeds, from which I'd take handfuls and sow them 'long in de row. Us had a horse-gin and screwpit, to git de cotton fit for de market in Charleston. Used four mules to gin de cotton and one mule to pack it[Pg 31] in a bale. Had rope ties and all kinds of bagging. Seems to me I 'members seein' old flour sacks doubled for to put de cotton bales in, in de screw-press.

"Us raised many cows, hogs, sheep, and goats on de Bell place. Us worked hard. Us all had one place to eat. Had two women cooks and plenty to eat, cooked in big pots and ovens. Dere was iron pegs in and up de kitchen chimneys, chain and hooks to hold pots 'bove de fire. Dat's de way to boil things, meats and things out de garden.

"Whippin's? Yes sir, I got 'most skinned alive once, when I didn't bring up de cows one Sunday. Got in a fight wid one of Miss Betsie Aiken's hands and let de cows git away, was de cause of de whippin'. I was 'shamed to tell him 'bout de fight. Maj. Bell, dis time, whipped me hisself.

"My white folks was psalm singers. I done drove them to de old brick church on Little River every Sabbath, as they call Sunday. Dere was Miss Margaret, his wife, Miss Sallie and Miss Maggie and de two young marsters, Tom and Hugh. De two boys and me in front and my mistress and de two girls behind. Maj. Bell, when he went, rode his saddle horse.

"Who-ee! Don't talk to dis nigger 'bout patrollers. They run me many a time. You had to have a pass wid your name on it, who you b'long to, where gwine to, and de date you expected back. If they find your pass was to Mr. James' and they ketch you at Mr. Rabb's, then you got a floggin', sure and plenty. Maj. Bell was a kind master and would give us Saturday. Us would go fishin' or rabbit huntin' sometime.

"Us had two doctors, Doctor Furman and Doctor Davis. White folks care for you when you sick. I didn't have no money in slavery time, didn't have no use for none. Us had no quarters, houses just here and dere on de place, 'round de spring where us got water.[Pg 32]

"My Marster went to de old war and was a major. He had brass buttons, butterflies on his shoulders, and all dat, when he come back.

"De Yankees come. Fust thing they look for was money. They put a pistol right in my forehead and say: 'I got to have your money, where is it?' Dere was a gal, Caroline, who had some money; they took it away from her. They took de geese, de chickens and all dat was worth takin' off de place, stripped it. Took all de meat out de smoke-house, corn out de crib, cattle out de pasture, burnt de gin-house and cotton. When they left, they shot some cows and hogs and left them lying right dere. Dere was a awful smell round dere for weeks after.

"Somethin' d'rected me, when I was free, to go work where I was born, on de Martin place. I married Mary Douglas, a good-lookin' wench. A Yankee took a fancy to her and she went off wid de Yankee. She stayed a long time, then come back, but I'd done got Preacher Rice to marry me to Louvinia then. Dis second wife was a good gal. I raised ten chillun by her, but I's outlived them all but Manuel, Clara and John. When Louvinia passed out, I got Magistrate Smith to jine me and Nancy. She's still livin'. Home sick now, can't do nothin'.

"White people been good to me. I've been livin' in dis home, free of rent, given me for life by Mr. Jim Smith, 'cause I was his faithful servant twenty years.

"Many times I's set up in de gallery of de old brick church on Little River. They had a special catechism for de slaves, dat asked us who made you, what He made you out of, and what He made you for? I ain't forgot de answers to dis day.

"Marster Major give us Chris'mas day and a pass to visit 'bout but we sho' had to be back and repo't befo' nine o'clock dat same day.[Pg 33]

"I got my name after freedom. My pappy b'long to Mr. David R. Evans. His name was Steve; wasn't married reg'lar to my mammy. So when I went to take a name in Reconstruction, white folks give me Lewis Evans.

"I b'longs to de Baptist church. Am trustin' in de Lord. He gives me a conscience and I knows when I's doin' right and when de devil is ridin' me and I's doin' wrong. I never worry over why He made one child white and one child black. He make both for His glory. I sings 'Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Jesus Gwine Carry Me Home.' Ain't got many more days to stay. I knows I'm gwine Home."

Project #1655

W. W. Dixon,

Winnsboro, S.C.

PHILLIP EVANS

EX-SLAVE 85 YEARS OLD.

Phillip Evans, his wife, Janie, and their crippled son live together in a two-room frame house with one fireplace. The old woman has been a wet nurse for many white families in Winnsboro. Neither Phillip nor his boy can work. The wife nurses occasionally.

"I was born at de General Bratton Canaan place 'bout six miles, sort of up a little, on de sunrise side of Winnsboro. I hopes you're not contrary like, to think it too much against dis old slave when I tells you de day. Well sir, dat day was de fust day of April but pray sir, don't write me down a fool 'cause I born on dat p'ticular April Fool Day, 1852. When I gits through wid you, I wants you to say if dat birthday have any 'fect on dis old man's sensibility.

"My pappy was name Dick. Him was bought by General Bratton from de sale of de Evans estate. My pappy often tell mammy and us chillun, dat his pappy was ketched in Africa and fetched to America on a big ship in a iron cage, 'long wid a whole heap of other black folks, and dat he was powerful sick at de stomach de time he was on de ship.

"My mammy was name Charlotte. Her say her know nothin' 'bout her daddy or where he come from. One of my brothers is de Reverend Jackson C. Evans, age 72. Richard, another brother, is 65 years old. All of us born on de Canaan Bratton place. General Bratton love dat place; so him named it proud, like de Land of Canaan.[Pg 35]

"I help to bring my brother Richard, us calls him Dick, into de world. Dat is, when mammy got in de pains, I run for de old granny on de place to come right away. Us both run all de way back. Good us did, for dat boy come right away. I 'members, to dis hour and minute, dat as soon as dat boy got here, he set de house full of noise, a-cryin' like a cat squallin'. All chillun does dat though, as soon as they come into de world. I got one sister older than me; her name Jenny Watson. Her live in a house on de Canaan place, callin' distance from where I live. Us is Methodists. A proud family, brought low by Mr. Hoover and his crowd. Had to sell our land. 'Spect us would have starved, as us too proud to beg. Thank God, Mr. Roosevelt come 'long. Him never ask whether us democrat or 'publican nor was us black or white; him just clothe our nakedness and ease de pains of hunger, and goin' further, us goin' to be took care of in our old age. Oh, how I love dat man; though they do say him got enemies.

"My brother, de preacher, says dat occasioned by de fact dat de President got a big stick and a big foot, dat sometime he tromp on de gout foots of some of them rich people. Howsomever, he say dat as long as de Lord, de Son, and de Holy Ghost is wid de President, it'll be all right for us colored folks. It makes no difference 'bout who is against de President. He says us niggers down South can do nothin' but be Methodist, pray to de Lord, and shout for de President. I's goin' to try to do some of de prayin' but dis voice too feeble to do much shoutin'.

"What kind of house us live in at slavery time? Nice plank house. All de houses in de quarters made dat way. Our beds was good. Us had a good marster. Our livin' houses and vittles was better and healthier than they is now. Big quarters had many families wid a big drove of chillun. Fed them from big long[Pg 36] trays set on planks. They eat wid iron spoons, made at de blacksmith's shop. What they eat? Peas, beans, okra, Irish 'tators, mush, shorts, bread, and milk. Dere was 'bout five or six acres to de garden. Us kept fat and happy.

"Who was de overseers? Mr. Wade Rawls was one and Mr. Osborne was another. There was another one but 'spect I won't name him, 'cause him had some trouble wid my Uncle Dennis. 'Pears like he insult my aunt and beat her. Uncle Dennis took it up, beat de overseer, and run off to de woods. Then when he git hungry, him come home at night for to eat sumpin'. Dis kept up 'til one day my pappy drive a wagon to town and Dennis jined him. Him was a settin' on de back of de wagon in de town and somebody point him out to a officer. They clamp him and put him in jail. After de 'vestigation they take him to de whippin' post of de town, tie his foots, make him put his hands in de stocks, pulled off his shirt, pull down his britches and whip him terrible.

"No sir, Marster General Bratton didn't 'low his slaves' chillun to work. I just played 'round, help feed de stock and pigs, bring in de fruit from de orchard and sich like.

"Yes sir, marster give me small coins. What I do wid de money? I buy a pretty cap, one time. Just don't 'members what I did wid it all.

"Us went fishin' in de Melton Branch, wid hooks. Ketch rock rollers, perch and catfish. They eat mighty good. I like de shortnin' bread and sugar cane 'lasses best and de fust time I ever do wrong was 'bout de watermelons.

"Our shoes was made on de place. They had wooden bottoms. My daddy, being de foreman, was de only slave dat was give de honor to wear boots.

"Dere was just two mulattoes on de place. One was a daughter of my aunt. All de niggers was crazy 'bout her and wid de consent of my aunt, marster give her to some kinfolks in Arkansas. De other was name, Rufus. My marster was[Pg 37] not his daddy. No use to put down dere in writing just who his pappy was.

"Stealing was de main crime. De whippin's was put on de backs, and if you scowled, dat would git you a whippin' right dere and then.

"Yes sir, dere is haunts, plenty of them. De devil is de daddy and they is hatched out in de swamps. My brother say they is demons of hell and has de witches of de earth for their hosses.

"De neighbors 'bout was de Neils, de Rawls, de Smiths, and de Mobleys. Marse Ed Mobley was great for huntin'. Marse General Bratton was a great sheep raiser. In spite of dat, they got along; though de dogs pestered de sheep and de shotguns peppered de dogs sometimes.

"My marster was a general in de Secession War. After dat, him a controller of de State. Him run old 'Buttermilk' Wallace out of Congress. Then he was a Congressman.

"My mistress was Miss Bettie. Her was a DuBose. Her child, Miss Isabella, marry some big man up North and their son, Theodore, is de bishop of de high 'Piscopal Church of Mississippi.

"Now I repeats de question: Does you think I's a fool just 'cause I's born on dat fust day of April, 1852?

"You made me feel religious askin' all them questions. Seem like a voice of all de days dat am gone turn over me and press on de heart, and dis room 'fect me like I was in a church. If you ever pass de Canaan place I'd be mighty happy to see you again."

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

June 16, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I was born in old Abbeville County, S.C. about 1861; was reared in what is now Greenwood County. My father was Winston Arnold and my mother, Sophronia Lomax Arnold. They belonged to the Arnold family during slavery time. I was just a small child during the Confederate War, and don't remember anything about it. I heard my mother tell about some things though. The slaves earned no money and were just given quarters to live in and something to eat. My father was a blacksmith on master's place, and after the war, he was blacksmith for himself. I heard him tell about the patrollers. They had lots of cornshuckings and cotton pickings, but they never worked at night.

"I remember the night-riders, but don't remember that they did any harm much except they got after a man once.

"When any of us got sick we sent for a doctor, but old-time folks I heard about, would use herbs, tree barks, and the like of that to make teas to drink.

"I married in a negro church when I was young. I married Frank Fair who came from Newberry County, S.C. After the ceremony, the neighbors gave me a nice dinner at the church.

"I don't remember anything about Lincoln or Jeff Davis, but I think Booker Washington is a leading colored man and has done good.

"I joined the church when I was nine years old, because my father and mother belonged, and so many young people were joining. I think everybody ought to join a church."

Source: Eugenia Fair (76). Greenwood, S.C.

Interviewed By: G.L. Summer, Newberry, S.C. (6/10/37)

Project 1885-1

Folklore

Spartanburg, Dist. 4

Oct. 14, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I lives in Newberry in a small three-room house which belongs to my son. He helps me some 'cause I can't work except jest a little 'round de house.

"I don't know much 'bout de war times. All I know is what I told you befo'. I 'member when de war quit and freedom come. Most of de slaves had to find work where dey could. Some had to work as share-croppers, some fer wages, and later on, some rented small plots of land. Many niggers since de war moved to town and worked as day hands, such as carpenters, janitors, dray drivers and de like.

"De old time folks had blacksmith shops on de farm and made most of de tools dey used. Dey had plenty to eat. We never wanted fer nothing and always lived good. I had it better den dan I does now.

"In slavery when de patrollers rode up and down de roads, once a nigger boy stole out to see his gal, all dressed up to kill. De patrollers found him at his gal's house and started to take off his coat so dey could whip him; but he said, 'Please don't let my gal see under my coat, 'cause I got on a bosom and no shirt'. (The custom was to wear stiff, white bosoms held up around the neck when no shirt was on. This gave the appearance of a shirt.)

"My sister-in-law and mother-in-law both come from Virginia but I don't 'member anything dey said 'bout dat country. My sister-in-law went back dere atter freedom come, but her mama died here.

"Us slaves went to de white folks' church at Cross Roads, and our mistress made us go. She often would teach us to read and[Pg 40] write at home when we would try to learn. Mistress had a nigger driver fer her carriage, and when he drove he wore a high beaver hat and a long coat. Our white folks had a big kitchen way off from de house. Dey had a big wide fireplace where dey cooked over de fire in skillets. My mistress had me to work in de house, kind of a house-girl, and she made me keep clean and put large ear rings in my ears so I would look good. When Christmas come, Marse and Mistress always give de slaves good things to eat. Dey had lots of cows, and dey give us good butter and milk, molasses, meats and other good things to eat. We always worked on week days except Saturdays, and sometimes on dat day until 12 o'clock. We always had Christmas and Easter holidays.

"We had corn-shuckings and cotton-pickings. De niggers would sing: 'Job, Job, farm in a row; Job, Job, farm in a row'. Sometimes on moonlight nights we had pender pullings and when we got through we had big suppers, always wid good potatoes or pumpkin pies, de best eating ever. We made corn bread wid plenty of milk, eggs and lard, and sometimes wid sweet potatoes, de best corn bread in de world. 'Simmon bread was made wid sifted 'simmon juice cooked wid flour.

"I married first time to Joe Todd, and had a big wedding what my mistress give me in her back yard. She had a big shoat killed fer de wedding dinner. My mistress den was Miss Cornelia Ervin. When I married de second time, I married in town to West Farrow, in de colored people's Baptist church, by Rev. West Rutherford, a nigger preacher, de pastor. My second husband died, too, a few years ago.

"I can't 'member much 'bout old songs, but a Baptist song was: 'Down to de water, River of Jordon; Down to de water, River of Jordon; Dere my Savior was baptized.'[Pg 41]

Another version went thus:

"Come along, come along, my dear loving brother,

Come along and let's go home;

Down into de River where my Savior was baptized.'

"De present generation of niggers ain't like de ones when I come along. Dey don't work like I did.

"I don't know much about 'Abramham' Lincoln, Jefferson Davis or Booker Washington. I just hear about Booker Washington, reckon he is all right.

"I think slavery helped me. I did better den dan I do now. When I joined de church I was grown and married, and had two chilluns. I joined de church because I thought I ought to settle down and do better fer my family, and quit dancing and frolicing."

Source: Caroline Farrow (N. 80), Newberry, S.C.

Interviewer: G.L. Summer, Newberry, S.C. (9/16/37)

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

May 24, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I was born in Newberry County. Near Chappells depot. My master, in slavery time, was John Boazman. He was a good man to his slaves. I was raised in the big-house, and helped as a servant-girl. My mistress smoked a pipe, and sometimes she would have me to get a red coal from de fire and put it in her pipe. I did dat wid tongs. I lived there a long time. I come to Newberry over 40 years ago and worked wid de white people in town.

"I married twice. My first husband was Joe Todd, and after he died, I married West Farrow. He was a dray-man in town for many years.

"The folks back home had fine farms, good gardens, and took pride in raising all kinds of things in the garden. They allus planted Irish potatoes the second time in one season.

"They cooked in big open fireplaces, in kitchens that set away off from the house. A big spider was always used for cooking over the fireplace.

"After de war, we stayed on awhile. My mistress took me to de white folks' church and made me sit in the gallery; then brought me home."

Source: Caroline Farrow (80), Newberry, S.C.

Interviewer: G.L. Summer, Newberry, S.C. (5/18/37)

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

June 28, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I do not knows when er whar I was born. My father was Price Feaster; mother was Lucy Richards Feaster. She belonged to Mr. Berry Richards dat lived 'tween Maybinton and Goshen Hill Township, on de 'Richards Quarter'. My sister name Harriet; brothers was Albert and Billy, and dats all de chilluns dere was in de family. My furs' recollection dat I knows was when we went to de Carlisles. I was so young dat I can't recall nothing much 'bout de Feaster plantation. Our beds was home-made and had ropes pulled tight frum one side to de other fer de slats. No sir, I doesn't know nothing 'bout no grandmaw and grandpaw.

"De furs' work dat I done was drapping peas. Albert was plow-hand when I come into de world. Harriet was up big enough to plant corn and peas, too. Billy looked atter de stock and de feeding of all de animals on de farm. My furs' money was made by gathering blackberries to sell at Goshen Hill to a lady dat made wine frum dem. I bought candy wit de money; people was crazy 'bout candy den. Dat's de reason I ain't got no toofies now.

"Ole lady Abbie looked out fer our rations. De mens eat on one side and de gals on t'other side de trough. We eat breakfast when de birds furs' commence singing off'n de roost. Jay birds 'ud allus call de slaves. Dey lowed: 'it's day, it's day,' and you had to git up. Dere wasn't no waiting 'bout it.[Pg 44] De whipperwill say, 'cut de chip out de whiteoak,' you better git up to keep frum gitting a whipping. Doves say, 'who you is, who you is.' Dat's a great sign in a dove. Once people wouldn't kill doves, ole marse sho would whip you if you did. Dove was furs' thing dat bring something back to Noah when de flood done gone frum over de land. When Freedom come, birds change song. One say, 'don't know what you gwine to do now.' 'n other one low, 'take a lien, take a lien.' Niggers live fat den wid bacon sides.

"Mr. Billy Thompson and Mr. Bill Harris' daddy give liens in dem days; dese big mens den. Captain Foster clothed de niggers atter Freedom.

"Ole lady Abbie give us mush and milk fer breakfast. Shorts and seconds was mixed wid de mush; no grease in de morning a-tall. Twelve o'clock brung plenty cow-peas, meat, bread and water. At night us drunk milk and et bread, black bread made frum de shorts. Jes' had meat at twelve o'clock, 'course 'sharpers' 'ud eat meat when marster didn't know. Dey go out and git 'em a hog frum a drove of seventy-five er a hund'ed; dat one never be missed.

"I is awful to hunt; come to Union to sell my rabbits and 'possums. Mr. Cohen dat run a brick yard, he buy some. Ole man Dunbar run'ed a market. He was ole man den. He's de beef market man; he take all de rabbits and sell 'em when I couldn't git a thing fer 'em. Ole lady living den, and when I git home she low is I got any 'loady' (something to eat). I come in wid beef and cow heads. Cow foots was de best meat. Dey throws all[Pg 45] sech as dat away now. Dere was allus a fuss in de house iffen I never had no 'loady'. Somehow er another I was allus a family man and was lucky to git in wid mens dat help me on. Never suffered wid help frum dese kind men. Dat's de way I got along as well as I has. Ole Missus and Marse learn't me to never tell a lie, and she teached me dat's de way to git along well. I still follows dat.

"Up in age, I got in wid cap'n Perram (Mr. George Perrin). He was de banker. He say 'bout me, 'what I likes 'bout Gus, he never tell a lie'.

"Befo' dat, I work fer Lawyer Monroe. He had a brother named Jim and one named George, his name Bill. His sister named Miss Sally. Dar I farm fer dem and work on half'uns. De Yankees camped on his place whar Mr. Gordon Godshall now got a house. N'used to go dar mi'night ev'y night and ev'y day. Dey had a pay day de furs' and de fifteenth of de month. Dey's terrible fer 'engans' (onions) and eggs. Dey git five marbles and put dem in a ring; put up fifty cents. Furs' man knocks out de middle-man (marble) got de game. Dey's jes' sporty to dat. Never had nothing but greenbacks den. Fifteen cents and ten cents pieces and twenty-five and as high as fifty cents pieces was paper in dem times.

"Dey larn't us a song: 'If I had ole Abe Lincoln all over dis world, but I know I can't whip him; but I fight him 'till I dies'. Dey low'd, 'we freeded you alls'.

"Another song was: 'Salvation free fer all mankind; Salvation free fer all mankind'. I was glad er all salvation.[Pg 46] 'Salvation free fer me'; got up dat song furs' on a moonlight night, and us sing it all night long, going from house to house.

"'Motherless chilluns sees hard times; just ain't got no whar to go; goes from do' to do',' dat's de song dey got up. I doesn't know whar it come from. 'Nother one was: 'When de sun refuse to shine; Lord I wants to be in de number, when de sun refuse to shine. If I had a po' mother she gone on befo', Lord I promise her I would meet her when de saints go marching in.' Dat's what lots people is still trying to do.

"We sot mud baskets fer cat fish; tie grapevines on dem and put dem in de river. We cotch some wid hooks. I went seining many times and I set nets; bought seins and made de nets. Pull up sein after a rain and have seventy-five or eighty fish; sometimes have none. Peter Mills made our cat fish stew and cooked ash-cake bread fer us to eat it wid. Water come to our necks while we seining and we git de fish while we drifting down stream.

"We wear cotton clothes in hot weather, dyed wid red dirt or mulberries, or stained wid green wa'nuts—dat is de hulls. Never had much exchanging of clothes in cold weather. In dat day us haul wood eight or ten feet long. De log houses was daubed wid mud and dey was warm. Fire last all night from dat big wood and de house didn't git cold. We had heavy shoes wid wood soles; heavy cotton socks which was wore de whole year through de cold weather, but we allus go barefeeted in hot weather. Young boys thirteen to fifteen years old had de foots measured. When tracks be seed in de wa'melon patch, dey was called up, and if de measurements of dere tracks fitted de ones in de[Pg 47] wa'melon patch, dat was de guilty nigger. I 'clar, you had to talk purty den. When I go in de wa'melon patch, I git de old missus to say fer me to go; den I could eat and nothing was said 'bout it.

"Sunday clothes was died red fer de gals; boys wore de same. We made de gals' hoops out'n grape vines. Dey give us a dime, if dey had one, fer a set of hoops.

"Twan't no dressing up fer marring in slavery times; just say, 'gwine to be a marriage tonight' and you see 'bout 40 or 50 folks dar to see it. If it be in wa'melon time, dey had a big feast atter de wedding. Old man preacher Tony would marry you fer nothing. De keep de wedding cake fer three weeks befo' it was eat."

Source: Gus Feaster (97), 20, Stutz Ave., Union, S.C.

Interviewer: Caldwell Sims, Union, S.C.

Project 1885-1

FOLKLORE

Spartanburg Dist. 4

July 7, 1937

Edited by:

Elmer Turnage

STORIES FROM EX-SLAVES

"I ain't never give you dis information. Miss Susie and Miss Tommie Carlisle, Marse Tom's onliest daughters, died befo' de surrender. Miss Susie slipped one day wid de scissors in her hand, and when she did dem scissors tuck and stuck in one her eyes and put it plum' smack out and she never did see out'n it no mo'. Dat made it so sad, and everybody cried wid her but it never done her narry bit of good.

"When dem young ladies died, I left out and run off from my ma and come to Union. Mr. Eller kept a big sto' jest as you come into town. It was jest about whar Mr. Mobley Jeter's is now. Dat's in de middle of town, but in de fur off days I is speaking about, it was de very outskirts of dis town. I is seed dis town grow, dat is what I is. Mr. Eller tuck me to be his driving boy, and dat sto' sot jest exactly whar de Chevet Charage (Chevrolet Garage) sets now.

"When I been dar six years, my ma come to Union and she found me dar. Us was dat glad to lay eyes on one another dat we jest shouted fur joy and my Ma tuck and smacked me wid her lips right in de mouth. She told me dat my pa had done got shot a fixing dem old breastworks down in Charleston and dat called fur a big cry from me and her both. Mr. Eller, he went out'n de back of his sto' 'till us quit. He let me go back home to de Carlisle place wid my ma. Everything done changed and I brung my ma back to Union and kept her, kaise I was a man in full den.[Pg 49]

"Lawyer Shand tuck my ma to work fur him and I started being his coachman. He ole and he live in Columbia now. When he done dat, me and ma lived in one of his houses. He lived on what you knows as Douglas Heights and he had de biggest house dar. Dat was way befo' Captain Douglas moved from Goshen Hill. Den Captain Douglas tuck de day and built dat house you sees now aheading what dey calls Douglas Heights atter Lawyer Shand's house was to' (torn) down. De house sot right on top de hill in de middle of de street you sees. His driveway was flanked wid water oaks and it retched down to Main street. De grounds was on each side dat drive and dey retched to whar de white folks is got a school (high school) now. On de other side of dat drive his grounds hit Miss Fant's (Mrs. John Fant's property).

"You could clam up Cap Douglas' stairs and git in a run-around (cupola) and see de whole town through dem glass winders. (This cupola is still on the house.) Never had none of dem things in Union afo' dat. Some years atter dat, when Col. Duncan had his house run over (remodeled) he had one of dem run-arounds put on his'n. To dis day wid all de fine fixings folks has in Union, dar ain't narry one got none of dem things and dey sho' is purty.

"Let me drap back, kaise I is gone too fer along; you wants olden times. On our plantation Marse Tom had a nigger driver. He 'hoop and holler and wake us up at break of day. But befo' freedom come 'long, Marse got a bell; den dat nigger driver rung dat bell at break of day. He was a sorry nigger dat never had no quality in him a'tall, no sir-ee.[Pg 50]

"Us had to feed de mules in de dark of mornings and de black of night when craps needed working bad. Seed many as a dozen hoe-womens in de field at one time. Dey come when dey finished breakfast and de plows had got a start.

"Dey used mulberry skins from fresh mulberry saplins to tie around dere waists fer belts. If your singletree chain broke, you fixed it wid mulberry skins; same wid your galluses. Mulberry is mighty strong and easy to tie anything dat break.

"Marse Tom never whipped 'bout nothing much but stealing. He never let his overseer do no whipping if he knowed it. He burnt you up 'bout stealing, dat he would.

"Dey never wanted us to git no larning. Edmund Carlisle, smartest nigger I is ever seed. He cut out blocks from pine bark on de pine tree and smooth it. Git white oak or hickory stick. Git a ink ball from de oak trees, and on Sadday and Sunday slip off whar de white folks wouldn't know 'bout it. He use stick fer pen and drap oak ball in water and dat be his ink atter it done stood all night. He larnt to write his name and how to make figures. Marse Jule and Bill, two of Marse Tom's boys, found out dat Edmund could write and dey wanted to whip him, but Marse Tom wouldn't let 'em.

"One morning Edmund was making a big fire 'round all de pots, kaise we was butchering forty hogs. Edmund had his head under de pot a blowing up de fire dat had done tuck and died to embers. Jule and Bill seed him and dey broke and run and pushed Edmund plum' under dem pots. De embers burnt his face and de hair off'n his head. Marse Tom wo' (wore) Bill and Jule out fer it. Missus 'lowed den dat Edmund de smartest nigger on dat plantation.[Pg 51]

"We had Sadday afternoons to do our work and to wash. We had all de hollidays off and a big time Christmas and July Fourth.

"Going to funerals we used all Marse's wagons. Quick as de funeral start, de preacher give out a funeral hymn. All in de procession tuck up de tune and as de wagons move along wid de mules at a slow walk, everybody sing dat hymn. When it done, another was lined out, and dat kept up 'till we reach de graveyard. Den de preacher pray and we sing some mo'. In dem days funerals was slow fer both de white and de black folks. Now dey is so fast, you is home again befo' you gits dar good.

"On de way home from de funeral, de mules would perk up a little in dey walk and a faster hymn was sung on de way home. When we got home, we was in a good mood from singing de faster hymns and de funeral soon be forgot.

"As a child everybody in dem days played marbles.

"Ma sung some of de oldest hymns dat I is ever heard: (He sang) 'O Zion, O Zion, O Zion, wanta git home at last'. (Another) 'Is you over, Is you over, Is you over' and the bass come back, 'Yes thank God, Yes thank God, Yes thank God, I is over. How did you cross? At de ferry, at de ferry, at de ferry, Yes, thank God I is over.' If I sing dem now folks laughs at me, but ma sho' teached dem to her chilluns.