The Project Gutenberg EBook of For Treasure Bound, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: For Treasure Bound

Author: Harry Collingwood

Release Date: April 13, 2007 [EBook #21069]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOR TREASURE BOUND ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"For Treasure Bound"

Chapter One.

The Wreck.

It was the last week in the month of November, 18—.

The weather, for some days previous, had been unusually boisterous for the time of year, and had culminated, on the morning on which my story opens, in a “November gale” from the south-west, exceeding in violence any previous gale within the memory of “the oldest inhabitant” of the locality. This is saying a great deal, for I was at the time living in Weymouth, a most delightful summer resort, where, however, the feelings are likely to be more or less harrowed every winter by fearful wrecks on the far-famed and much-dreaded Chesil Beach, which connects the mis-named island of Portland with the mainland.

We had dined, as usual, at the primitive hour of one o’clock; and with Bob Trunnion—about whom I shall have more to say anon—I had turned out under the verandah to enjoy our post-prandial smoke, according to invariable usage. My sister Ada would not permit us the indulgence of that luxury indoors, and no conceivable disturbance of the elements could compel us to forego it altogether.

We were pacing the verandah side by side, quarter-deck fashion, with our hands behind our backs and our weeds between our teeth, making an occasional remark about the weather as the sheeted rain swept past us, and the trees in the distance and the leaf-denuded shrubs in the garden bowed before the fury of the blast, when a coastguard-man, whom I had occasionally encountered and spoken to in my rambles, came running past, enveloped in oilskins and topped by a sou’-wester.

As he went by, seeing us, he shouted, “Ship coming ashore in the West Bay, sir!” and was the next minute at the bottom of the hill, en route, as fast as his legs could carry him, for the town.

Our house was situated in a pleasant suburb called Rodwell; the high-road which passed our door led direct to the Smallmouth Sands, at the farther extremity of which was the Chesil Beach; and we conjectured that the coastguard-man had come from the beach along this road to give notice to the chief officer stationed in the town.

To run indoors, don our foul-weather rigging, and notify my sister that we were off to the scene of the anticipated wreck, was the work of a moment. The next we were in the road, inclined forward at an angle of forty-five degrees against the wind, and staggering slowly ahead in the direction of the sands. The coastguard-man had a fair wind of it, and was going a good eight knots when he passed us; but just at the top of the hill, as we were exposed to the full strength of the gale, we did not forge ahead at more than about one knot. However, matters mended soon after, for we surmounted the brow of the hill, and began the descent on the opposite side; here the road took a slight bend, which brought the wind well abeam; so keeping close under the hedge to windward of us, we rattled away as fast as we could go.

After nearly an hour’s severe exertion we reached the beach. The vessel which was expected to come on shore was a full-rigged ship, apparently of about eight hundred or a thousand tons, and evidently a foreigner, by her build and rig. Some conjectured her to be French, some Spanish, and others avowed their belief that she was a German; but she was still too far off, and the weather too thick, to enable any one to form a clear judgment as to her nationality.

“Whoever she is,” said the chief boatman, “the skipper of her is a downright good seaman, and doesn’t intend to lose his ship whilst he can do anything to save her. He drove into the bay about two hours ago, sir,” said he, turning to me, “and this is the second time that he’s tried to fetch out again; but, Lord! he don’t know this place so well as I do, or he’d be as sartain as I be that she’ll never go outside o’ the Bill o’ Portland again. The ship don’t float that, with her sails alone, could get out of the bay, once she got into it, with the wind and tide the way it is now; and afore the tide turns he’ll be knocked into match-wood, or my name’s not Joe Grummet. There he comes round again,” continued the man, who had kept his eye on the vessel all the time he was speaking; “but it’s no good; he’s more ’n a mile to leeward of where he fetched last time, and he’d better give it up and run her ashore whilst ’tis light enough to get the hands out of her, if so be as it please God to let any on ’em come ashore alive.”

The vessel had, as Grummet remarked, altered her course; running off rapidly before the wind, and consequently towards the land; and those who knew nothing about nautical matters would have supposed that her commander had at length given up the contest, and was about to run her on shore.

But we knew better. The vessel had merely been kept away in order to wear her; staying in such a tremendous gale and sea being utterly out of the question. And as we watched we saw her come slowly to the wind on the opposite tack; her yards were braced sharp up, her sheets flattened in, and once more the battle for life was resumed against the hostile elements.

But it was evident that the noble ship’s career was ended. The operation of wearing had brought her into fearful proximity with the land; and though she carried reefed mainsail and foresail under close-reefed topsails, and fore and main topmast staysails, it was evident that she was driving to leeward at a frightful rate, and that the period of her existence must now be measured in minutes.

“Now, lads! bear a hand!” shouted Grummet, “and let’s signal her to run in here. The beach is steeper here than anywhere within the next three or four mile; and if he happens to come in on the back of a sea, he’ll run up pretty near high and dry; and we may get some of the poor souls ashore alive, and cheat Davy Jones out of the best part of his bargain this bout, anyway.”

A large red bandana handkerchief was produced and seized to the end of a boat-hook; this extempore flag and staff Grummet took in his hand, and, proceeding to the summit of the beach, commenced waving it to and fro, to attract the attention of the people on board the doomed ship. She was now so close that we could see the two men at her wheel, and a man, whom we supposed to be the master, standing by the mizen rigging.

Just abaft the mainmast, and huddled together under the shelter of the weather bulwarks, we could see some seven or eight more of her crew, and others were doubtless cowering elsewhere out of sight.

Grummet waved his flag energetically from the crest of the beach, and the coastguardmen busied themselves in making such slight preparations as were in their power to assist the crew in escaping from the wreck. Several coils of line had been brought down to the beach; one man, who announced himself to be a good swimmer, had secured an end of the smallest of these to his waist; he now stood prepared to divest himself of all his superfluous clothing at a moment’s notice, and to attempt the hazardous experiment of rushing into the boiling surf, to drag out any poor unfortunate whom he might be able to reach. Others were engaged in various ways in preparing themselves to render what assistance was in their power, when a cry from Grummet announced that the crisis had arrived; on looking up we saw that the stranger’s fore-topmast had gone in the cap; and now hung to leeward, with the topsail and topmast staysail thrashing to ribbons; the latter threatening at every jerk to take the bowsprit out of the ship. The foresail was also split from head to foot; and, even as we looked, the overstrained canvas gave way, and, fluttering for a moment in the furious gale, parted from the bolt-ropes, and came flying like a shred of cloud to leeward.

The ship, thus deprived of her head-sail, luffed into the wind; and the moment that the rest of her canvas shook, away it came also, leaving her helpless and unmanageable, with the sea sweeping her deck fore and aft.

“Now stand by, men,” shouted Grummet, “and each one do his best for the poor souls; for they were never nearer to death’s door than they will be in another two minutes. If he had run her stem on to the beach they might have stood a chance; but I fear it is all over with them now, for she’ll come ashore broadside-on, and all on us knows what that means.”

Fortunately, the catastrophe had happened immediately to windward of that part of the beach on which we stood; a spot, as Grummet had observed, where the shipwrecked crew would have a better chance of reaching the shore alive than they would have had if stranded on any other part of it for some miles on either side; but the loss of their sails had rendered the prospect of their escape considerably less than it would have been had they been able to watch their chance, sail the ship in on the crest of a wave, and so beach her.

The next half-minute or so was one of most intense and painful excitement to us spectators on shore. Each man moved nearer to the water, and cast off some article of clothing, or gave a last look to the line, or a final adjustment to the life-buoy round his waist. For myself, I had stripped off my jacket and waistcoat, and placed them, together with my hat, in the hands of my friend Bob; and I now stood with the end of a line, knotted into a bowline, in my hand, ready to do anything which the emergency of the moment might require.

The master of the vessel appeared to be aware of our intention, and the meaning of the signal which Grummet had shown; and as it was now impossible to run the ship stem on upon the beach, he did the next best thing; and waving his hand to the men who, like true seamen, still stuck to the wheel, they put the helm hard up, that she might come in stern on.

The manoeuvre was partially successful; but unfortunately she came ashore between two seas; and the undertow of the one taking her stern, whilst the succeeding sea struck her bow, she fell broadside-to in an instant, her three masts went by the board, and the sea made a clean breach over her.

One poor fellow was seen to leap overboard at the moment that the ship struck; and half-a-dozen of the men on the beach rushed down into the water, making frantic efforts to get at him. But he could not swim; and those who tried to reach him were flung back, bruised and senseless, upon the beach, only to be dragged away again as the sea receded; and had it not been for the ropes and life-buoys round their waists, by which their comrades hauled them on shore, they must have lost their lives. As it was, one of them, in some way or other, got out of the life-buoy, and we saw him swept away almost from our very feet.

I was an expert swimmer; and as soon as I saw the poor fellow being swept away, I slipped my head and shoulders through the bowline knot I held in my hand, dashed into the surf, and, resorting to my usual tactics of diving through the breakers, managed to get hold of the man with one hand, while I raised the other above my head, as a signal to those on shore to haul away upon their end of the line.

As soon as I felt the line tighten round me, I grasped the man round the body, and in another moment we were both on the beach, in the arms of those who had run down to meet us. By these we were dragged up out of reach of the sea, and, on staggering to my feet, I had the satisfaction of seeing the man who had jumped overboard from the wreck being hauled on board again.

Loud were the thanks and praises I received for my conduct in bringing the other on shore; but without waiting to listen to them, I hastily explained that I would try to take a line on board the wreck, as, if I could succeed in this, there might possibly be some chance of saving the major portion, if not the whole of the crew. Accordingly I dashed into the surf once more; and at length, after the most superhuman efforts, though the distance was barely thirty yards, I reached the ship’s side, and was drawn on board by a line which her crew threw to me. The men crowded round me, rapidly talking in some language which I could not understand, and looking as much relieved as though I had the power of taking them all on my back at once, and swimming on shore with them. I stood for a moment to recover my breath; and at the same time looked about to see what resources might be at my command. I noticed a towing hawser coiled away upon what had originally been the deckhouse forward, but which was now stove in and battered almost out of recognition. An eye was spliced in one end of this hawser; and taking it up, I signed to the men to pass it over the stump of the foremast. They understood me, and, seeing my object in wishing it done, they had it over in a twinkling; in another moment, they had the heavy coil capsized, the other end bent on to the line which I had brought on board with me, and were paying it rapidly over the side.

As I turned to address the master of the vessel, who, I noticed as I was hauled up the side, was then standing at the break of the poop, issuing instructions to his crew, I saw him in the act of descending the poop-ladder, and I stepped towards him. At this moment the ship was lifted up by a perfect mountain of a sea, and hove over on her beam-ends; all hands of us were flung violently to leeward; and before apparently any of us had time to recover our feet, another sea swept down upon us; there was a terrific—an ear-splitting crash, a wild, agonised cry, and I found myself clear of the wreck, struggling wildly for life, with the body of the master within arm’s length of me.

He was apparently dead, and floating face downwards; but I grasped him by the hair, turned him on his back, and struck out for the beach. Twice were we flung like corks upon the pebbles of the strand, and twice dragged off into deep water again by the merciless undertow. The first time I dug my fingers, knees, and the toes of my boots into the pebbles, in the hope of bringing myself and my senseless charge to an anchor; but I might as well have attempted to grasp the air. The whole of that portion of the beach which was exposed to the action of the sea was a vast moving mass, the shingle being alternately thrown up and sucked back again in tons, as the water hurled itself high upon the beach and then rushed back into the foaming abyss.

The second time we were thrown up with such violence that I was stunned; but the third time the brave fellows on the beach, who had been making the most frantic efforts to get at us, would take no denial. They watched their chance, and as they saw us again drifting in, two, with ropes round their waists, rushed into the sea, grasped us, one each, firmly round the body; and, though they were lifted off their feet and dragged away to seaward like feathers by the retiring breaker, never let go their hold until we were hauled up high and dry, clear beyond the reach of the heaviest wave.

The efforts made to restore me to consciousness were soon successful, but my fellow-sufferer, the master of the vessel, appeared to be seriously injured. It was nearly half an hour before the faintest signs of returning animation were perceived; and when at length consciousness returned, the poor fellow appeared to be suffering the most excruciating agony.

As soon as I was once more able to look about me, I found that the wave which had washed the master and me overboard, had broken the wreck in two just abaft the mainmast, flinging the stern portion much nearer the shore, whilst it had turned the other half fairly bottom up, precipitating, of course, all the poor fellows, who were so busy paying out the hawser, into the sea. The people on the beach watched eagerly for their reappearance above water, but not one of them was ever seen again. It afterwards transpired that there was not a swimmer amongst the entire crew, which, all told, amounted to fifteen hands.

The intelligence of a wreck had attracted a large concourse of people to the spot, notwithstanding the discomfort attendant on being abroad in so violent a gale; and one gentleman had taken upon himself to despatch omnibuses from the town, well supplied with blankets, etcetera, for the relief and benefit of any poor sufferers who might reach the shore alive. Into one of these vehicles the unfortunate master of the ship was now placed with the utmost care, a couch being extemporised for him in the bottom of the ’bus by piling together all the blankets which had been sent. In spite, however, of the utmost care in driving, the jolts were frequent, and sometimes rather heavy, and the poor fellow’s groans indicated such intensity of suffering, that by the time we were half-way to town I decided I would take him to my own house, whereby he would be spared nearly half an hour of anguish.

It fortunately happened that, just as I had come to this resolution, a gentleman rode up, and learning who we had inside, volunteered his services. I immediately accepted them, desiring him to ride back to the town, and despatch to my house the ablest physician he could find. When the ’bus drew up at our door, the doctor was there in readiness for his patient, whom we lifted out, apparently in the last stage of exhaustion, and carried carefully into the house and upstairs into my own room, where my sister (advertised by Bob, who had made the best of his way home on foot) had a cheerful fire blazing in the grate, hot water in abundance, and everything else ready that her womanly sympathy could suggest.

Chapter Two.

The Secret.

The doctor remained with the sick man more than half an hour; and when I heard his footstep descending the staircase I went out and met him.

“The poor fellow is sinking rapidly,” said he, in reply to my inquiries; “he has received severe internal injuries, and is bleeding to death inwardly. I can do nothing, absolutely nothing for him. Keep him quiet, and humour him as much as you can; excitement of any kind will only hasten his dissolution.” I cheerfully promised to do all I could for the dying man; and the doctor took his leave, promising to call again the last thing in the evening.

As soon as the doctor was out of the house I went upstairs and into the sick-room, where I found the patient in bed, and Bob, with his boots off, gliding as quietly about the room as a trained hospital nurse, doing all he could to contribute to the comfort of his charge.

The opening of the door attracted the sick man’s attention, and he feebly turned his head in my direction. As soon as he recognised me, he beckoned me to approach; and I drew a chair to the side of the bed, asking him how he felt.

“Like one whose moments are numbered,” replied he in perfectly pure English, but with a sonorous ring in the articulation of the words, which betrayed the fact that he was not speaking in his mother tongue. “Señor,” he continued, “I am dying; the doctor has candidly told me so, though I needed no such assurance from him. The dreadful pangs which shoot through my tortured frame are such as no man could long endure and live. I am a true Catholic, señor, and I would fain see a priest, or some good man of my own creed, that I may confess, and clear my guilty soul from the stains which a life of sinful indulgence and contempt of Heaven’s laws has polluted it with. I know there are many of my faith in England; it may be that there are some in this place. Know you of any such?”

I replied that there certainly was a Catholic church in the town, but it was situated at some distance from the house in which he now lay; consequently it would perhaps be an hour before the priest could be found and brought to him; “but,” added I, “I will send for him forthwith, and until he arrive I will sit here and keep you company.”

So saying, I called Bob on one side, and directed him to proceed, as quickly as possible, into town, and bring the Reverend Father without a moment’s delay to the house.

As soon as Bob had departed, I resumed my seat by the bedside. Extending his burning hand towards me, he clasped mine, and endeavoured to raise it to his lips. “Señor,” said he, “since it is the will of God that I am to die, I can but bow to that will in submission; but I would I could have been spared for a few years to testify my gratitude to you for your brave and noble efforts in behalf of my crew and myself—my poor people, my poor people,” he sobbed—“all, all lost!”

He was silent for nearly five minutes; and I took advantage of the opportunity to explain to him that what I had done was no more than any other Englishman would do if he had the power, under similar circumstances; that such conduct was thought nothing of among our nation; being regarded as simply a duty which each man owed to every other, in like circumstances of distress with his own.

“I know—I know,” replied he, “the English are as generous as they are brave; but still I would I had it in my power to express my thanks otherwise than in words. But I am alone in the world which I am so soon to leave. Not one have I of my own name or blood to whom I can bequeath my debt of gratitude; and when my ship went to pieces to-day (she was my own property, señor), I became a beggar. I have not so much property left as will pay the expenses of my burial; and here I lie, indebted to a stranger, and that stranger a foreigner, for the shelter which covers my dying head, as I soon shall be for the coffin and the grave which await my lifeless clay.”

I was beginning to say something, with the intention of diverting his mind from so painful a train of thought, when he interrupted me eagerly.

“And yet,” continued he, “poor as I am, it is in my power to make you rich—ay, beyond the utmost scope of your imagination. And I will, I will! Why should I take this secret to the grave with me? In a few hours I shall be beyond the want of earthly riches, but you, señor, are young, and look forward to a long life; doubtless, like other men, you have already indulged in many a bright day-dream which the possession of wealth would go far to realise. Listen, gentil señor; I must be brief, for I feel that I have no time to lose. I have been shipwrecked once before. It is now nearly three years ago since I sailed from Valparaiso for Canton, whence we were to proceed to Bombay, and so home round the Cape of Good Hope. I was then chief-mate. We met with nothing but calms for the first three weeks of our passage, after which the weather changed, and we had a succession of adverse gales until we were within fifteen degrees of the line. Here we were worse off than ever, for at one moment we were lying in a glassy calm, and perhaps in five minutes afterwards were under close-reefed canvas, or possibly bare poles. At length a furious squall threw the ship on her beam-ends, and we were compelled to cut away all three of her masts to save her from foundering. And then the squall settled down into a perfect hurricane, and we could do nothing but suffer the ship to drive dead before it. Near midnight we were flung violently to the deck by a tremendous shock. The ship was on shore, dashing her bottom out upon the rocks. And it was so dark, señor, that we were unable to see each other. Oh! the horror of that night; it is as fresh upon me now as it was at the moment that it happened.”

The poor fellow’s face was streaming with perspiration. I begged he would not distress himself by recalling such painful recollections, but in spite of my remonstrance he continued his story.

“The ship broke up beneath our feet, and I found myself swimming, I knew not where, in the midst of a quantity of floating wreck, to a piece of which I clung. I was surrounded on every side by breakers; but not far from me I could perceive, by the absence of the phosphorescence, that the water was smooth. I urged myself, and the plank to which I clung, in that direction, and soon reached the smooth water; after which I suffered myself to drift. The water was quite warm, and I experienced no inconvenience whatever from my immersion. After the lapse of perhaps an hour, possibly more, I felt the ground beneath my feet, and staggering out of the water, I flung myself upon the dry land, and, notwithstanding the howling of the wind and the roar of the breakers, I fell into a deep and dreamless sleep.

“When I awoke the sun was beating fiercely down upon my uncovered head; the sky was cloudless; and a calm had succeeded to the gale of the night before. I rose to my feet, and on looking about me, discovered that I had been cast upon one of those coral islands which so thickly stud some portions of the Pacific. I was—as I am now—the only one who escaped the wreck alive. The bodies of my shipmates lay scattered along the shore; and a long and arduous day was spent in burying them where they lay, in such shallow graves as I could scoop in the sand with the aid of a piece of splintered plank. The beach was strewed with wreckage which had been washed over the reef and into the smooth water; and I was overjoyed to find amongst this the long-boat, perfectly uninjured. In her I visited the scene of the wreck; and there, after diligent search, I found the means and a sufficiency of appropriate materials to enable me to fit her for a lengthened voyage.

“I was more than two months on the island before my preparations were complete, for life was very enjoyable in that delightful spot, and I felt in no hurry to get away. At length, whilst walking along the beach one evening, my attention was attracted to three or four pieces of old, worm-eaten, weather-worn timber, which I had often noticed before, projecting above the sand; and curiosity now impelled me to walk up to and examine them. A careful scrutiny revealed to me that they formed part of the framework of a ship; and I resolved that I would return the next day and ascertain whether what I saw was merely a detached piece of wreck, or whether the entire hull lay there embedded in the sand.

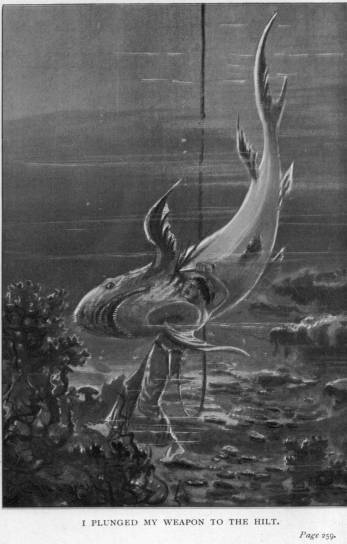

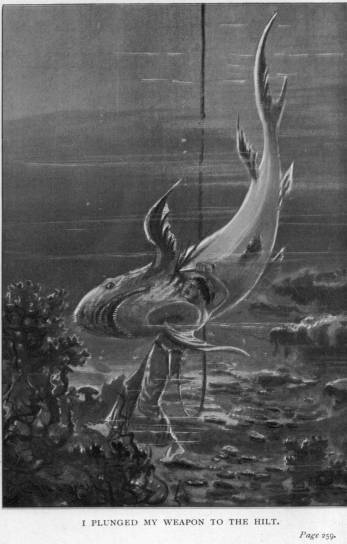

“The next morning I repaired to the spot, armed with a primitive substitute for a shovel, which I had contrived to manufacture, and an iron bolt, to serve the purpose of a crow-bar, which I had procured the previous night by burning it out of a piece of wreck. I had worked for perhaps an hour, when I reached some planking, which I immediately recognised as the deck of the ship. This I proceeded to clear of sand, uncovering the deck in an extending circle from the spot where I had first encountered it, until I had an area of about fifteen or sixteen feet laid bare. And now I met with a breach in the deck; so instead of clearing away further, I began to dig down again. I toiled thus for four days, señor; by which time I had discovered that the wreck was that of a small vessel, of perhaps one hundred and thirty tons (though, small as she was, she had been built with a full poop); that she was a very ancient craft indeed; and that her cargo consisted of nothing but gold, señor, that is, with the solitary exception of a strong wooden box (which, even after so long an interment, offered considerable resistance to my efforts to open it), containing an assortment of what I took to be pebbles of different kinds, but which I afterwards found were unpolished gems. Yes, señor; there lay the gold in ingots, each wrapped in matting, and each ingot as much in weight as I could well lift. The matting was decayed in the first three or four tiers, and the metal discoloured almost to blackness; but towards the centre of the cargo (which is, probably, not more than twelve tiers deep altogether), the matting, though so rotten that it crumbled to dust as I touched it, had preserved the colour of the metal; and there it lay, bar after bar, gleaming with the dull yellow lustre peculiar to virgin gold.

“I ballasted my boat entirely with ingots; selecting the most discoloured I could reach, so that they might be less easily recognisable as gold, and the risk I ran of being ultimately robbed of them reduced in the same proportion. I also took a few of the pebbles (as I thought them) out of the box; after which I set to work to cover in the whole once more. I completed my task by burning down the timbers which had at first attracted my attention (and which I found were a portion of her stern frame), so that nothing remained above the surface of the sand to betray the whereabouts of my treasure. I then carefully marked the spot in such a manner that I could find it again; and completed my preparations for departure with all speed.

“I had been at sea ten days, when I was taken ill. Whether it was the effect of excitement or exposure I know not; but I fell into a raging fever, which left me almost at the point of death. I was so weak that I had not strength to crawl to the water-cask; and the feeble efforts I made to reach it so exhausted me that at length I fell in a swoon to the bottom of the boat. In this condition I was discovered by a passing ship, the crew of which took me on board; but, as a smart breeze happened to be blowing at the time, they would not wait to hoist in my boat; and she was set adrift with enough gold on board her to have purchased a principality.

“Regrets were useless, and the loss, heavy as it was, troubled me little; I knew where to find sufficient to satisfy my utmost needs. At length I reached home, and, by the merest accident, bethought myself one day of my pebbles. I suspected they were valuable, or they would not have been found where they were. Judge of my surprise when I learned that the four I had left (for I lost the rest somewhere) were worth a sufficient sum to enable me to do exactly what I wished; viz., buy a ship of my own. I did so; and was on my way in her to my treasure-island, when the gale sprung up which has reduced me to my present condition.

“And now, señor, I am about to put you in possession of such information as will enable you to find my island. It is in latitude about — South, and in longitude about — West, as nearly as I had the means of ascertaining; and is uninhabited, and, I should say, unknown; for during my entire stay there, I never observed one solitary sign of man’s foot having ever pressed the soil. You will readily recognise the island from the fact that it has a remarkable isolated group of seven cocoa-nut trees growing closely together on the extreme northernmost point of the island. The central tree of this group, and one of the others, bears a mark (made by the removal of a piece of bark) as large as a man’s two hands. When you have identified these trees, walk away from them, keeping them in one, until you open, clear of the trees on the southern end of the island, a portion of the reef which you will observe just rising above the water’s edge. When you have done this, you will be standing, as nearly as possible, immediately above the hole in the deck of the wreck, through which I burrowed to her golden cargo.”

The Spaniard (for such I found him to be) then went on to describe the manner in which I should find the passage through the reef into the lagoon, giving me as much information as he could from memory of the various dangers to be avoided. He had carefully prepared a chart of the channel before leaving the island; but this was on board the vessel he had just lost.

I could see that the excitement produced by so much talking was fearfully reducing his strength, and I more than once endeavoured to persuade him to postpone the completion of his narrative; but he was sensible that he had but a short time to live, and so anxious was he to give me all the information necessary to enable me to discover this strangely buried treasure, that my endeavour to stop him did more harm even than the talking, so I was compelled perforce to suffer him to proceed. And though I felt it my duty to urge him not to excite himself, I must confess that I was deeply interested to learn how I might become possessed of the wealth to which he had referred in such glowing terms; for since it was manifest that he could not live to enjoy it himself, and as he had declared he had no relative in the world, I thought I might as well become his heir.

He continued to talk for some time longer, until he had explained to me everything he could think of which would facilitate my efforts to reach the buried treasure; and then, with a sigh of mingled exhaustion and relief, he closed his eyes, and seemed to sink into a half sleep, from which he roused himself at frequent intervals, to crave the refreshment of a draught of lemonade.

At length the sound of carriage wheels was heard; and almost immediately afterwards Bob returned, accompanied by the Catholic priest. The sick man opened his eyes, and feebly welcomed the good old man who had so readily answered his appeal for spiritual consolation. I then retired, leaving them alone to engage in the most solemn rite appertaining to their religion.

After we had reverently laid the Spaniard to rest in his alien grave, I gave my friend Bob a full and accurate account of all that had passed, showing him at the same time the copious notes I had, at the earliest opportunity, jotted down to assist and refresh my memory in case I should ever find myself in a position to seek the hidden treasure.

Chapter Three.

Bob’s Proposition.

I was at this time just turned twenty-one, and had received my education at the Royal Naval School at Greenwich, with the understanding that I was to join my father on its completion, when he would continue and finish what is there so well begun, thus making me “every inch a sailor.”

On leaving school I joined my father (who was master and part owner of a fine dashing clipper), in the capacity of midshipman, and went some six or seven voyages with him: on the last of which, or rather, a few days after its termination, I was seized with a violent attack of rheumatic fever, from which I had not recovered sufficiently to rejoin the ship by the time that she was once more ready for sea. I was consequently left at home under Ada’s care (my dear mother had been dead some years), to recover at leisure, and amuse myself as well as I could until another voyage should be accomplished, and an opportunity once more offered for me to repossess myself of my quarters in the old familiar berth. That opportunity never arrived, for at the time my story opens, my father had been two years “missing.” He sailed from Canton with the first cargo of the new season’s teas, and from the moment that the good ship disappeared seaward she had never been heard of; not the faintest trace of a clue to the mystery of her fate having, so far, been discovered.

Bob Trunnion was a middle-aged man, of medium stature, great personal strength, and no very marked pretensions to beauty; but he was as thorough an old sea-dog as ever looked upon salt water. His visage was burnt to a deep brick-red by years of exposure to all sorts of weather; and his hair and beard, which had once been brown, were now changed to the hue of old oakum by the same process, except where, here and there, a slight sprinkling of grey discovered itself. He had been a sailor almost all his life, having “crept in through the hawse-pipe” when he was only twelve years old; since when, by close application and perseverance, he had gradually worked his way aft to the quarter-deck. He joined my father’s ship as second mate, on the same voyage as I did, and on the following voyage took the chief-mate’s berth, in place of a man whom my father was compelled to discharge for confirmed drunkenness.

The last time that my poor father passed down Channel, outward-bound, Bob had the misfortune (as we thought it then), to fall off the poop and break his arm. It was what the surgeons call a compound fracture, and certainly looked to be a very ugly one; so, as the ship happened at the time to be off Saint Alban’s Head, my father ran into Weymouth roads, and sent Bob ashore to our house to be cured, and to bear me company; shipping in his stead the second mate, and picking up a new second mate somewhere about the town.

Thus it happened that Bob and I, old shipmates as we were, happened to be both away from our ship when her mysterious fate overtook her. As soon as we were both recovered, we sought and obtained berths, always in the same ship, for short voyages; returning home about once in every six weeks or two months, with the hope of hearing either that my father had returned, or that some news had arrived of him. For the last twelve months we had abandoned the former hope, but the latter would probably be many years before it finally took its flight.

Ada Collingwood, my only sister, was just seventeen.

This introduction and explanation are necessary to the understanding of what is to follow; and now, having fairly weathered them both, we may take up the thread of the story, and follow it out to the end without further interruption.

I have already said that I took an early opportunity to give Bob a detailed account of the Spaniard’s revelation to me. This was on the evening of the day on which we laid the poor fellow in his grave; and I told my story while we and my sister were seated comfortably round the fire after tea, with the curtains drawn close, and everything made snug for the night.

Bob listened with the utmost attention to my story (as did also my sister), occasionally requesting me to “say that ag’in,” as some point in the narrative was reached which he wished to bear particularly in mind; and when I had finished he sat for some time staring meditatively between the bars of the grate.

At length, “Well, Harry, my lad, what do you intend to do?” said he.

“That,” replied I, “is just the point upon which I want your advice. If this story be true—”

“No fear about that,” said Bob. “It’s true enough. The thing’s as plain and circumstantial as the ship’s course when it’s pricked off upon the chart. There ain’t a kink in the yarn from end to end; it’s all coiled down as neat and snug as a new hawser in the ropemaker’s yard; and besides, dyin’ men don’t spin yarns with no truth in ’em, just for divarsion’s sake, like.”

“Well,” said I, “I have not the means of purchasing a ship of my own; and if I had, do you think it would be safe to trust so much treasure with a crew, picked up though ever so carefully?”

“Ah! now you ’pawls me,” replied Bob, rubbing the back of his head reflectively. “I’ve sailed with crews as you might ha’ trusted with untold gold, at least, I’ve thowt so at the time I was with ’em; but mayhap, if temptation was throwed in their way, they mightn’t be able to stand out agin it; there’s no gettin’ to the bottom o’ the heart o’ man. As to the ship, that’s easy enough. If you ain’t got the cash to buy, you can always charter.”

“True,” said I, “and if I could make sure of finding a sufficient number of thorough good men, that is the course I should be inclined to pursue. Do you think, Bob, that by diligent search we could find some six or eight really reliable men? The craft need not be a large one, you know—”

“There you’ve hit the solution of the enigmy, as the schoolmaster said,” replied Bob, bringing his clenched fist down upon my knee with an emphasis which impressed me for the remainder of the evening: “How much of that gold now do you reckon would make your fortune, lad? you’re pretty good at figures; just cipher it up and let’s hear?”

“How much!” exclaimed I; “oh, a very small portion of the whole cargo would satisfy me if I had it here at this moment.”

“How much?” persisted Bob. “Would a ton of it be enough for you, boy?”

“Yes, indeed,” laughed I; “a ton of pure gold - why, what do you suppose that would be worth, Bob?”

“Hain’t much of a ’idee,” replied he.

“A ton of pure gold,” said I, “is worth over one hundred thousand pounds, Bob; I believe one hundred and twenty-five thousand pounds is nearer its value; though I cannot say for certain.”

“Then,” said Bob, “if we can manage to get, say, a couple of tons of it home, you will be satisfied—eh?”

“Perfectly,” I replied; “but how do you propose to accomplish this?” for I saw he had a scheme to bring forward.

“Nothing easier,” replied Bob. “Build a little craft big enough to accommodate the two of us; with room to stow away our grub and water, and the two tons of gold; and up anchor and away.”

“But,” said I, “you forget that this island is somewhere in the Pacific. Such a craft as you speak of would be totally unfit for the voyage we contemplate.”

“Why?” inquired Bob.

“Why?” repeated I, astonished at the question. “Simply because we should never get across the Bay of Biscay in her, to say nothing of the remainder of the voyage.”

“Why not?” demanded Bob, rather pugnaciously.

“Do you mean to say,” I retorted, “that you can sit there and propose in cold blood such a hair-brained scheme as that we two should undertake a voyage to the Pacific in a mere boat?”

“I do,” replied Bob emphatically. “That’s a simple way out of all your difficulties. The craft will be your own; there will be no risk of the crew rising upon us for the sake of our cargo; and nobody to say ‘What are we doing here?’ or ‘What do you want there?’ Why, it will be a mere pleasure trip from end to end, all play and no work, leastways none to speak on!”

“But, my dear fellow, do be serious,” protested I. “You know, as well as I do, that we should be swamped the first time we fell in with a capful of wind.”

“Maybe we should, if we went to work like a couple of know-nothing land-lubbers,” retorted Bob; “but if we went to work like seamen, as we are, I should like to know what’s to purvent our sailing round the world if we like! Answer me that.”

“Come, Bob, old man, let us hear the full extent of your proposition,” said I. “I know that, whatever it may be, it will be the proposal of a thorough seaman, for if any one could carry out the wild scheme you have suggested, you are the man.”

“’Tain’t such a very wild scheme neither,” replied Bob. “Answer me this. How many people was saved from the London when she foundered in the Bay of Biscay?”

“Nineteen, if I remember rightly,” replied I.

“Very well; now if a small boat of about twenty-five feet long or thereabouts, open, mind you, from stem to starn, could live twenty hours with nineteen people in her, as the London’s pinnace did, in weather that the old ship herself couldn’t stand up agin, how long will a full-decked boat of, say, thirty to thirty-five feet long, carefully constructed, and in good trim, live with only two men in her? And warn’t I,” continued he, “nineteen days alone in an open boat in the South Atlantic; and didn’t I make a v’y’ge of a thousand miles in her afore I struck soundings at Saint Helena?”

This last question referred to an adventure which had befallen Bob in his younger days, on an occasion when he had been cruelly deserted in a sinking ship by the rest of the crew, and had made his escape, as described by himself, after enduring unheard-of suffering.

“Then,” questioned I, “you seriously entertain the belief that the scheme you have suggested is practicable?”

“With ease and comfort,” replied Bob. “Now look here, Harry. You can afford to build a craft such as I have described, and fit her out for the v’y’ge, and still leave money enough at home to keep sauce-box here,” (indicating Ada, who was to him as the apple of his eye) “comfortable and happy like till we come back. You’ve a rare eye for a sea-boat, and mine ain’t bad, for that matter; let’s draught her out ourselves, since it’s our own lives as we are going to trust in her; and if we don’t turn out, between us, as pretty a sea-boat as ever floated, why, turn to and lay me up in ordinary for the rest of my days for a useless old hulk, that’s all. A boat thirty feet long, decked all over, and carefully designed, can’t sink, boy, because we can easily arrange matters so as to keep her dry inside; she’ll ride as light as a gull and as dry as a bone when big ships is making bad weather of it, and as for the matter of capsizing, bein’ run down, or cast away, why they’re dangers as we are liable to in any ship, and must be guarded against in every craft, large or small; and our little barkie would carry comfortable all we should want for the v’y’ge, for we could touch here and there out and home to make good deficiencies, and we two are men enough to handle her in all weathers. Rig her as a cutter, boy. I was once’t aboard a cutter yacht in a trip up the Mediterranean, and you’ve no idea what a handy rig it is, once you’re used to it. And the way them cutters ’ll hug the wind—why ’t would make a difference of nigh on a couple of thousand miles, out and home, in the length of the passage.”

I began to be infected with Bob’s enthusiasm. The scheme, which had at first appeared to me as the very acme of fool-hardiness, now, under the influence of Bob’s eloquence, gradually assumed an appearance of reasonableness, and a promising prospect of success, which was very fascinating. Nevertheless, I could not but remember that the proposed voyage would take us into latitudes subject to the most frightful and sudden tempests, and I could not help thinking (as I pointed out to Bob) that our cockle-shell would stand but a poor chance in a cyclone or a black squall.

“Look here, Harry, my boy,” remarked Bob gravely, “as I propose to ship on this here v’y’ge as chief-mate, I ain’t likely to forget that there’s such dangers as them you’ve just mentioned; But suppose you was to cork up a bottle, or clap the lid on an empty biscuit-tin, and heave ’em overboard, do you think they’d live through one or t’other? In course they would, because salt water can’t get inside of ’em, and as long as they keep dry holds they’ll float, let the weather be what it will, and so ’ll our craft, for the same reason. And when the weather’s too bad to sail the barkie, we can heave her to, and when it’s too bad for that we can anchor her, my boy, go below, slide on the top of the companion, and turn in until the weather clears.”

“But,” said I, “we cannot anchor in the middle of the Atlantic. Suppose we should be caught in a cyclone there, for instance?”

“We can anchor there, lad, with a floating anchor, which will keep her head to wind; and with everything snug aloft and on deck, and a floating-anchor ahead with about sixty fathoms of cable veered out, she would ride out in safety any gale that ever blew out of the heavens.”

This last remark closed the case, and secured a verdict for the defendant. I knew that every word Bob spoke was literally true, and the audacity of the enterprise so fascinated me that I resolved on the spot to undertake it, if it should be found, on going into details, that a craft, capable of being handled by our two selves, could stow away, without being overloaded, such provisions; etcetera, as we should need for the voyage.

The following morning, immediately after breakfast, I got out my drawing board, strained a sheet of paper upon it, and, with Bob at my side to give me the benefit of his opinion upon every line I traced upon the paper, set to in earnest to design the little craft in which we proposed to embark on our adventurous voyage.

Before putting a line upon paper, however, we settled the plan of her internal arrangements. It was our intention to make her lines as fine as her respective dimensions would permit; she was to be, in fact, a small yacht. We knew that every vessel with sharp lines must necessarily be wet, unless the weights she would have to carry were all concentrated about her midship section, or broadest part, so we decided that as far as was practicable such should be the arrangement with us; and we knew that, if we could succeed in this, our barkie might be as sharp as we could make her, and still be dry and comfortable. We accordingly prepared a list of our requirements, as far as we could think of them, calculated the space they and the ballast would occupy, and then roughly sketched out the proposed lines. These were altered, rearranged, and improved upon time after time, until at length we felt we had got them as near perfection as the dimensions of the boat and our own knowledge would carry us. And I may as well say at once that throughout the entire voyage we never had the slightest reason to think our little vessel could be in any way improved upon by alteration.

It is not probable that so long a voyage as ours will be often undertaken again in such a very small craft as we accomplished it in; but there are many men, I have no doubt, who would gladly receive a hint as to the most advantageous form for a small boat in which they might safely adventure, alone, or with a friend, a cruise, say round the British Isles, or across the Channel and along the French coast; and therefore, as this story is written for the amusement only of such people as love boats, I think I may venture to trespass so far on my readers’ patience as to give such a hint in the shape of a brief description of the Water Lily, as Ada christened her.

She was, then, thirty-six feet long, and twelve feet beam on the water-line; but, in designing her midship section, we caused her sides to swell out boldly above water, so that her greatest beam was fourteen feet, at a point one foot six inches above the water-line. At this point her side tumbled home two inches as it was carried upwards to her deck, and from the same point the side curved quickly inwards and downwards until it met the water-line, when it swept under water with an almost imperceptible curve for some distance, and then took a moderately quick bend downwards to meet her keel. This gave us a vessel in shape very much like the centre-board model of boat, but with a deep keel, and consequently great lateral resistance, and space low down in the hull for the stowage of ballast. We thus secured a very small displacement, a light buoyant hull, extraordinary stability, and a fair amount of power.

The hull was divided into three compartments by bulkheads with wide doors which, if necessary, we could close water-tight. In the fore compartment we decided to place nothing except the smallest and lightest cooking-stove we could find. In the midship compartment it was intended to stow our ballast, water-tank, provisions, the chain-cables, and in fact everything which we could possibly place there, leaving only a narrow passage amidships to pass to and fro. The after compartment we intended to make our cabin, and there we arranged also to sling our hammocks. It will easily be understood that there was not an inch of spare room anywhere; but as our lives would be spent almost entirely on deck, we did not mind that very much.

Having designed our craft, the next question was, who should build her? Bob was strongly in favour of having her built in the town, so that we might oversee the laying of every plank, and the driving of every nail; but I knew there were firms who could safely be trusted to honestly put the best of work and material into the little vessel without being watched; and I determined to put her into the hands of a very celebrated firm of London boat builders.

Accordingly, Bob and I ran up to town, taking my sister with us for a holiday, and on the morning after our arrival, having seen Ada safely disposed of for the day with some friends of ours, we two men set out for the building-yard.

I placed our design in the hands of the principal, telling him at the same time that we wanted a boat of those dimensions, and, if possible, built on those lines, and that she was intended to keep at sea in all weathers.

He looked rather surprised at the last stipulation; but after carefully examining the drawing, and asking us our reasons for certain little peculiarities of shape, he confessed that, as far as his experience went, he could frankly say he had never seen a model better adapted for the purpose.

“And yet, gentlemen,” said he, “she will be wonderfully fast, for, in the first place, her hull is of such a shape that it will offer but a trifling resistance to forward motion; and, in the next place, these overhanging top-sides will, give her such extraordinary stability, as soon as she begins to heel over, that you will be able to carry enormous sails.”

We were very glad to hear our own judgment thus confirmed by a man, part of whose business it was to form a correct opinion with respect to the points upon which he had touched, and we said as much.

He took a great deal of interest in what must, after all, have been a very trifling matter to him; and both Bob and I had reason often afterwards to congratulate ourselves that we had confided the building of our boat to such good hands.

He proposed that she should be composite built; that is, that for the sake of lightness and strength combined, her frame should be of steel, with an inner skin of thin steel plate, and an outer planking of two thicknesses of mahogany. The ribs were to be arranged diagonally crossing the keel at an angle of forty-five degrees, and intersecting each other at right angles, thus converting her entire frame into a sort of lattice-work girder.

It was arranged that all the fastenings of the inner thickness of planking should be of iron, whilst the outside planks should be secured with copper fastenings. The utmost care was exercised (and, as experience proved, with complete success) to prevent the slightest approach to galvanic action, and one of the precautions taken was, I remember well, the painting of the inner planking with melted india-rubber, which was laid on coat after coat until there was about one-sixteenth of an inch of the rubber between the outer and inner planks.

As we did not intend to sail until the following summer, the builder had about eight months in which to put our little ship together, a circumstance at which he expressed great satisfaction, as he said it would enable him to pick and choose his materials, and put careful work into her.

We arranged, at the same time, for the construction of a boat to take with us, as we felt that in the event of any untoward accident happening, we ought to have something to take to for the saving of our lives, and we knew also that there would be many occasions when we should require something to answer the purposes which a boat answers with regard to a ship.

The designing of this boat was beset by difficulties, all originating in one, viz., want of space in which to stow her. To think of carrying her on deck was out of the question, as the deck was not spacious enough, in the first place, to receive such a boat as we wanted; and even had it been, there was no chance of its remaining there; it would have been carried away by the first sea which swept over us. We required something large enough to carry us both, and a stock of provisions in addition, so that should it be necessary to abandon the Water Lily, we might hope to reach land, or fall in with a ship. We also wanted something that should be essentially a life-boat, whilst she should also be very fast. How to obtain all these desiderata, and at the same time overcome the difficulty in respect to room, we knew not. But, resolved not to be baffled, we set our wits to work, and at length schemed out a design of an exceedingly novel character, which proved in all respects a most brilliant success.

Two hollow steel cylinders, of very thin metal, twenty-six feet long and one foot diameter in the centre, tapering gradually away to nothing at each end, were constructed in thirteen lengths of two feet each. These lengths, being of different diameters, stowed one within the other, thus taking up very little room indeed. In either end of each length was inserted a narrow band of metal thick enough to allow of a worm and screw, so that all the lengths of each cylinder could be screwed together perfectly water-tight. A light steel framework of simple arrangement connected the two cylinders together, at a distance of six feet apart, with their centre lines parallel, and supported, at a height of two feet above the top of the cylinders, a light stage ten feet long and six feet wide. On the top of the stage, and connected with the framework, was a step for a mast, and a gammon-iron for a bowsprit, and underneath the stage was a centre-board which we could lower or raise at pleasure. A broad rudder, fixed to the after-part of the stage, completed the design.

We spent a fortnight in London, and, having witnessed the laying of the Water Lily’s keel, and inspected some of the timber which the builder proposed to use in her construction, I saw Ada safe home again, leaving Bob in London to look out for a ship, which, when I rejoined him a couple of days afterwards, he had found.

We shipped in her for a voyage to Constantinople and Trebizond, which occupied us for eight months, and when we returned to London, on the termination of this voyage, we found the Water Lily completed, with the exception of a few finishing touches, which the workmen were then giving her.

Chapter Four.

Our Trial Trip.

Mr Wood, the shipbuilder, took us into his office, and there laid before us a sail draught, which he had carefully prepared for the guidance of the sailmaker, in making the Water Lily’s sails.

“You have never told me, gentlemen,” said he, “why you are having this little craft built; but the great pains which you have taken in the preparation of her design, and the whole tenour of your remarks when giving us the order to build her, impressed me at the time with a conviction that her destiny is to be something beyond that of most vessels of her size. As we proceeded with our work, I could not fail to be struck (as you will perhaps remember I was at my first glance at your drawing) with the fact, that whilst she is eminently calculated to prove a wonderfully fine little sea-boat, she is equally certain to develop most extraordinary sailing powers; and so great is the interest I take in her, that I could not be satisfied with intrusting the preparation of her sail draught to any other than myself; for I foresee that she will, in all probability, become a ‘public character,’ so to speak, and in that capacity she will undoubtedly reflect great credit on her builders. I have therefore calculated, with the utmost nicety, the proportion of her various sails, so that they may take effect to the greatest advantage; and this is the result of my labours,” producing at the same time the drawing to which I have referred.

I must confess that, for my own part, I was staggered at the enormous spread of canvas Mr Wood proposed to pile upon our little boat; but he declared that she would carry it with the greatest ease. “In fact,” said he, “I have kept rather within the limit of her powers, bearing in mind a remark you made to the effect that she would have to keep to sea in all weathers; and so confident am I that she is not over-sailed, that if you find I am wrong, I undertake to bear all the expense of a new outfit of sails, and the necessary reduction of spars. With regard to your ‘boat’ (though to my mind she looks much more like an ingeniously designed raft), the idea is so new that I cannot take it upon myself to utter an opinion about her, though I can see no reason why she should not be as fast as she undoubtedly is safe.”

We sent off the sail-drawing to Lapthorn of Gosport (determined to have the best made suit of sails it was possible to procure), with instructions to prepare them without delay, and then started off, by the first train, to Weymouth.

I found my dear sister safe and well, and more lovely than ever; but her spirits were subdued by contemplation of the dangers attending the voyage upon which we were now so soon to embark. The poor girl had been thinking of little else, it seemed, during our absence, until the liveliest alarm had taken the place of that confidence with which she had viewed the expedition when it was first broached.

But Bob and I had talked matters over together in many a quiet night-watch, canvassing the various emergencies which might arise, and the best mode of meeting them; and we were now confident that, with only the ordinary perils of the ocean to contend with, our adventure was not only feasible, but that it would certainly be crowned with success. And so we were well prepared to do battle with Ada’s apprehensions, which we did so vigorously that we at length succeeded in restoring, in a great measure, the confidence she had lost.

We arranged, after a considerable amount of discussion, that our own house should be let, furnished as it was, during my absence, and that my sister should take up her quarters with an aunt who resided on the Esplanade, Mrs Moseley accompanying her, with unlimited leave of absence from time to time to visit her own relatives.

These arrangements completed, Bob and I set out for London again, to superintend the rigging of our boat and to bring her round to Weymouth, from whence we intended to take our final departure.

On our arrival we found the little craft already in the water, with her mast stepped and her ballast (which was of lead, cast to fit the shape of her bottom) in. A portion of her ballast, consisting of a piece of lead weighing five hundredweight, was let into her keel about the midship section, and this, with two tons of lead inside, we thought would prove sufficient, after our “cargo” was stowed. Part of this cargo we intended to take from London with us, viz., the water-tank, filled, second suit of sails and flying-kites in the shape of spinnaker, jib-topsail, square-headed gaff-topsail, etcetera, also a four-pound rifle gun, with a stock of powder and shot, and a few percussion shells.

These we decided to take in case of our being obliged to assume a warlike attitude towards any savages we might come in contact with, as we had heard that the natives of some of the Pacific islands are particularly ferocious, and require to be dealt with promptly. We also provided ourselves with a couple of air-guns of improved construction and decidedly formidable character, four six-chambered revolving rifles, and the same number of revolver pistols, also a small but excellent chest of carpenter’s tools, a medicine-chest, etcetera.

But when these and our boat were all stowed away, there still remained more room than I expected in our midship compartment, and the little craft floated with her load-line nearly a foot above the water’s edge. I proposed ballasting her down to her proper depth with sand-bags, but Bob seemed anxious to test her sail-carrying powers light as she was, urging that though we should start well down in the water, she would lift as our provisions grew short; and it was desirable to know by experiment beforehand how far we could lighten her with safety.

Our sails had arrived, and we proceeded to bend these forthwith, and set them; as the weather being fine, with light air, a very favourable opportunity offered for stretching them gently and uniformly. We were as pleased with these sails as we were with the hull of our little craft. They were perfect masterpieces of the sailmaker’s art, the jibs being angulated, and the mainsail, square-headed gaff-topsail, and trysail being made with gored cloths.

This latter arrangement was an extravagant one as to the amount of cloth used in the making of each sail, but we were more than repaid for it by the perfection of set in the sails, which stood as flat as boards. Our storm-sails were made of stout canvas, and the fine-weather ones of American cotton canvas, a most beautiful material, extremely light, yet so close woven that not a breath of the faintest breeze was lost, and they were white as snow.

Our standing rigging was of wire, this being lighter, and offering less windage than hemp-rigging of the same strength; but, in order to counteract its rigidity and give play to the spars, we adopted the expedient of connecting the deadeyes to the chain-plates by a bolt and shackle arrangement, interposing a thick india-rubber washer between the shackle and the bolt-head. This plan answered most admirably, and I would strongly recommend it to all users of wire-rigging. I am confident that, in a fresh breeze and a chopping sea, we gained fully a knot per hour in speed by it.

Whilst our sails were stretching, Bob and I occupied our time in looking about us for a few things which we thought we could better obtain in London than anywhere else. Amongst these were a couple of air mattresses for our hammocks, which, when fully inflated, were capable of sustaining the weight of three men each in the water. Another article was a cooking-stove, the smallest, lightest, and most compact thing of the kind I ever saw.

It had a boiler capable of heating a quart of water, and an oven large enough to bake a fowl, with kettle, saucepan, etcetera, for the top. The grate proper was filled with fragments of some substance, the name of which I have forgotten, and underneath the grate was a sliding tray which held a six-wicked lamp. The lamp being lighted and placed in position, speedily raised the substance in the grate to a state of incandescence, and there was our fire, which gave out a tremendous heat for the size of the grate. As an aid to this stove, and an economiser of fuel, we purchased also a most extraordinary invention, which was named the “Norwegian cooking-stove” if I remember rightly.

This was not a stove at all, though it performed the functions of one. It was simply a box, so constructed that it retained all the heat your dish might happen to contain when placed in it. The mode of operation was to place your fowl or pie, or what not, in the oven until it was thoroughly hot through, then take it out, place it in the “Norwegian,” shut it up for two or three hours, take it out, and lo! your dinner was cooked to perfection. The fuel which this affair saved us during the voyage would have bought a dozen of them. We spent a week looking about for such things as these, and I am confident that, but for the economy of space which we were able to secure through the aid of these contrivances, our voyage must have come to a sudden and ignominious conclusion.

At length we were all ataunto; sails stretched to perfection and properly bent, our impedimenta all carefully and snugly stowed, and everything ready for a start. At the instigation and through the kindness of some yachting friends of mine, I had been introduced to and was elected a member of the Royal — Yacht Club; so one fine morning towards the latter end of July we loosed our sails, set them, ran our Club burgee up to the mast-head and the ensign up to the peak, and made a start for Weymouth. At the last moment Mr Wood, the builder of our little craft, came on board, saying that as he had nothing very pressing for the day, and was curious to see something of the way in which the Water Lily behaved, he would take a passage with us as far as Gravesend, if we had no objection.

We were only too pleased to have his company, and of course gave him a cordial welcome. The moment he came on board we cast off our moorings, ran up the jib and foresail, and slid rapidly away from the shore. The wind was moderately fresh from the northward, so we started under mainsail, foresail, and jib, but with the topmast lowered, as, being in very light trim, I did not think it advisable to run any risks by crowding sail upon the barkie.

We found, as I had expected, that on an even keel she was crank, though not to the extent I had anticipated; but as she began to heel over her overhanging topside supported her; so that, as the breeze freshened (which it did gradually), the more she lay down to it the stiffer she became.

As our confidence in her stability and sail-carrying powers thus became established, we grew anxious to try her paces, and forthwith got her topmast on end, the rigging set up, and put the square-headed gaff-topsail upon her. This was a very large sail for the size of the vessel, though, like the mainsail, it was not particularly high in the hoist; but both sails were very much peaked, the gaff-topsail so much so that the yard was almost straight up and down.

With the setting of our big topsail an immediate and very marked improvement in speed became manifest. Before this we had been darting along at a very respectable speed, passing some smart-looking schooners as though they had been at anchor; but now the little craft fairly rushed through the water, making it hiss and smoke under her sharp bows, and leaving a long wake of bubbles behind her. She heeled over still more, of course, but it was with a steady kind of resistance to the force of the wind which did finally away with any lurking fears we might have had that we were over-sparred or over-sailed.

We hove our patent log, and found that we were spinning along a good eight knots through the water; and indeed we came up with, and passed with ease, several vessels which were being towed down the river. Bob and I were enchanted, and Mr Wood scarcely less so; and when, shortly after luncheon, he stepped into the boat which he had hailed to put him on shore at Gravesend, he said, “I am sure the little craft will come with credit out of the ordeal through which you are going to put her, whatever it may be; so, gentlemen, I hope you will favour me on your return with a full account of your and her adventures.”

We took leave of him with a hearty shake of the hand, and a faithful promise that we would do so (a promise which I intend to fulfil by sending him a handsomely-bound copy of this “log” as soon as printed); let draw the fore-sheet, and resumed our course down the river.

We met with no adventure worthy of record on our passage down, unless I except the amusement we derived from the chagrin of the crew of a French steamer bound to Havre, who, to their amazement, found that the little English yacht, by cutting off corners, skimming across shoals, and similar manoeuvres, was slowly drawing ahead of them; and though, after passing Sheerness, she gradually crept ahead of us at first, yet as the wind freshened, and we continued to “carry on” until the water was over our deck on the lee-side half-way up to the companion, we actually overtook and passed her, until, to escape an ignominious defeat, she set her own sails and so drew away from us.

By eight o’clock that night we were off the North Foreland, bowling along at a slashing pace, with our mainsail boomed out to starboard, and our spinnaker set on the port side, jib and foresail stowed.

It was a glorious summer evening, and there was every prospect of its being a fine night; the aneroid evinced, if anything, a tendency to rise, and there was a good slice of the moon left, though she would be rather late in rising, so we determined to keep going all night.

By ten o’clock we were flying through the Downs; and very ticklish work it was to thread in and out between the ships at anchor there and those beating up, without experiencing a jibe, but by dint of a sharp look-out we did it. By midnight we were off Dover, and here we took in the spinnaker, jibbed the boom over to port, and set our jib and foresail. Bob wanted the spinnaker set again on the starboard side; but I would not agree to this, as, though we had both been on deck hitherto, he insisted on taking the middle watch alone, while I went below for a four hours’ sleep, and I did not think it prudent to leave him alone with so large and unmanageable a sail.

I wanted to take in the gaff-topsail also, but Bob would not hear of such a thing. He insisted that she was under easy and manageable canvas, and that there was nothing like making a passage while we had the opportunity. In this sentiment I fully agreed with him; but still I thought it better to err on the safe side, at least for the present, until we had become better acquainted with the capabilities of the craft. But Bob was obdurate, and at last I had to give in and rest content with the assurance that he would give me timely warning if it should become necessary to shorten sail.

When I came on deck at four o’clock I found we were just off Dungeness, and in the midst of an outward-bound fleet of ships of all sizes and almost all nations. The wind appeared to have freshened somewhat during Bob’s watch; but the morning was beautifully clear and fine; and, as our spars seemed to bear with the utmost ease the sail we were carrying, I thought we might venture to try the effect of a little extra “muslin.”

Accordingly, before relieving Bob at the tiller, I roused out our spinnaker again; and as we had hauled up a couple of points for Beachy Head just as I came on deck, I got it to the bowsprit-end and set it, with its sheet led aft to the main-boom-end, in place of the jib, which, with the foresail, I stowed. Bob then went below and turned in, first giving me strict injunctions to call him at “seven-bells,” that he might turn out and prepare breakfast, for it now appeared that he intended to unite the functions of chief-mate and cook and steward, on the voyage we had just started upon so auspiciously.

The substitution of the spinnaker for the jib and foresail made a very great difference in our rate of sailing. When I first came on deck I noticed some distance astern a splendid clipper-ship, bowling along with every stitch of canvas set that would draw, up to skysails and royal studding-sails. By the time I had got my spinnaker set she was abreast of us, about half a mile outside and consequently to leeward. But now she was unable to draw away from us an inch, so great was our speed through the smooth water; and when Bob came on deck at “seven-bells,” she still lay as nearly as possible in the same position with regard to us as when he went below.

“Phew!” whistled he, as his eye fell on her, “so the big chap has found his match, has he, in a craft the size of his own long-boat. My eyes! Harry, but this here is a little flyer, and no mistake. Why, the post-office people ’ll be wanting us to carry their mails for ’em, if so be as they gets to hear on us, eh, lad?”

Closing this remark with a chuckle of intense satisfaction and a leer at our big neighbour, Bob dived below again; and shortly afterwards a frizzling sound from forward, and an odour strongly suggestive of bacon and eggs, which was wafted upwards from the companion, informed me that he had entered upon the duties of the less dignified but equally important part of his combined self-appointment.

We made a hearty breakfast off the aforesaid bacon and eggs, with soft tack laid in the day before, and washed all down with some most excellent coffee, in the concoction of which beverage Bob was an adept, and then, as soon as he had washed up, and put matters to rights in his pantry, and made arrangements for dinner, I went below and turned in until noon.

When I went upon deck again, I found that the breeze had softened down very considerably, and we were slipping along barely five knots through the water. Our big neighbour, the ship, could do nothing with us in such light airs, and he was now a good six miles astern.

During the afternoon, the wind dropped still more, and by eight o’clock in the evening we had little more than steerage-way.

The water was absolutely without a ripple; our sails flapped, the main-boom swung inboard with every heave of the little craft over the long, gentle undulations of the ground-swell; and the different vessels in sight were heading to all points of the compass.

It was, to all appearance, stark calm; yet there must have been a light though imperceptible air, for on looking over the bows there was a smooth unbroken ripple stretching away on each side, showing that we were moving through the water still, though very gently; and the fact that the little craft answered her helm was additional testimony to the same effect.

During the night a little air came out from off the land, and we mended our pace somewhat; but it was not until the following noon that we got fairly abreast of Saint Catherine’s Point.

About eight o’clock the same evening, the wind still being light, we were abreast of the Needles; about a couple of miles to the westward of them, and apparently steering pretty nearly the same course as ourselves, we saw a cutter yacht about our own size.

By midnight we were abreast of Durlstone Head, and had gained so much upon the other cutter that we could make out that she had a large and apparently a very merry party on board. Hearty peals of laughter came frequently across the water towards us from her, and occasionally a song, generally with a good rattling chorus.

We continued to creep up to her, and at length got abreast of and so near her that, with the advantage of a good run, an active man might have leaped from one vessel to the other.

As we ranged up alongside, a most aristocratic-looking man stepped to leeward, and, grasping lightly with one hand the aftermost shroud, while with the other he slightly lifted his straw hat in salute, he inquired:

“What cutter is that?”

“The Water Lily, Royal — Yacht Club,” replied I. “What cutter is that?”

“The Emerald, Royal Victoria,” answered our new acquaintance. “You have a singularly fast vessel under you,” continued he; “I believe I may say she is the first that ever passed me in such weather as this. I have hitherto thought that, in light winds, the Emerald has not her match afloat; yet you are stealing through my lee as if we were at anchor. I presume, by the course you are steering, that you are, like ourselves, bound to Weymouth. If so, I should like to step on board you when we arrive, if you will allow me. I am curious to see a little more of the craft that is able to slip away from us as you are doing, in our own weather. I am Lord —,” he explained, thinking, I suppose, that we should like to know who it was who thus invited himself on board a perfect stranger.

I shouted back (for we were by this time some distance ahead of the Emerald) that I should be happy to see his lordship on board whenever he pleased to come; and then the conversation ceased, the distance between the two vessels having become too great to permit of its being continued with comfort.