Project Gutenberg's The Cruise of the Nonsuch Buccaneer, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Cruise of the Nonsuch Buccaneer

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: John Williamson

Release Date: April 13, 2007 [EBook #21062]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CRUISE OF THE NONSUCH ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"The Cruise of the Nonsuch Buccaneer"

Chapter One.

How George Saint Leger returned from foreign parts.

The time was mid-afternoon, the date was January the 9th, in the year of our Lord 1569; and the good town of Plymouth was basking in the hazy sunlight and mild temperature of one of those delightful days that occasionally visit the metropolis of the West Country, even in mid-winter, under the beneficent influence of the Gulf Stream combined with a soft but enduring breeze from the south-south-east charged with warm air from the Saharan desert and the Mediterranean.

So mild and genial was the weather that certain lads, imbued with that spirit of lawlessness and adventure which seems inherent in the nature of the young Briton, had conspired together to defy the authority of their schoolmaster by playing truant from afternoon school and going to bathe in Firestone Bay. And it was while these lads were dressing, after revelling in their stolen enjoyment, that their attention was attracted by the appearance of a tall ship gliding up the Sound before the soft breathing of the languid breeze.

That she was a foreign-going ship was evident at a glance, first from her size, and, secondly, from the whiteness of her canvas, bleached by long exposure to a southern sun; and as she drew nearer, the display of flags and pennons which she made, and the sounds of trumpet, fife, hautboy, and drum which floated down the wind from her seemed to indicate that her captain regarded his safe arrival in English waters as something in the nature of a triumph.

By the time that she had arrived abreast of Picklecombe Point the bathers had completely resumed their clothing and, having climbed to the highest point within easy reach, now stood interestedly watching the slow approach of the ship, her progress under the impulse of the gentle breeze being greatly retarded by the ebb tide. Speculation was rife among the little group of boys upon the question of the ship’s identity, some maintaining that she must necessarily be a Plymouther, otherwise what was she doing there, while others, for no very clearly denned reason, expressed the contrary opinion.

At length one of the party who had been intently regarding the craft for several minutes, suddenly flung his cap into the air, caught it as it fell, and exclaimed excitedly as he replaced it on his head:

“I know her, I du; ’tis my Uncle Marshall’s Bonaventure, whoam from the Mediterranean and Spain; I’m off to tell my uncle. ’Twas only yesterday that I heard him say he’d give a noble to know that the Bonaventure had escaped the Spaniards; and a noble will pay me well for the flogging that I shall get from old Sir John, if Uncle Richard tells him that I played truant to go bathing. But I don’t believe he will; he’ll be so mighty pleased to hear about the Bonaventure that he’ll forget to ask how I come to be to Firestone Bay instead of to schule.”

And the exultant lad dashed away toward Stonehouse, accompanied by his companions, each of whom was instantly ready to help with suggestions as to the spending of the prospective noble.

The historian of the period has omitted to record whether that worthy, Mr Richard Marshall, one of the most thriving merchants of Plymouth, was as good as his word in the matter of the promised noble; but probably he was, for shortly after the arrival of his nephew with the momentous news, the good man emerged from his house, smiling and rubbing his hands with satisfaction, and made the best of his way to the wharf in Stonehouse Pool, alongside which he knew that the Bonaventure would moor, and was there speedily joined by quite a little crowd of other people who were all more or less intimately interested in the ship and her crew, and who had been brought to the spot by the rapid spread of the news that the Bonaventure was approaching.

To the impatient watchers it seemed an age before the ship hove in sight at the mouth of the Pool. At length, however, as the sun dipped behind the wooded slopes across the water toward Millbrook, a ship’s spritsail and sprit topsail, with a long pennon streaming from the head of the mast which supported the latter, crept slowly into view beyond Devil’s Point, to the accompaniment of a general shout of “There a be!” from the waiting crowd, and a minute later the entire ship stood revealed, heading up the Pool under all sail, to the impulse of the dying breeze which was by this time so faint that the white canvas of the approaching craft scarcely strained at all upon its sheets and yards.

For the period, the Bonaventure was a ship of considerable size, her registered measurement being one hundred and twenty-seven tons. She was practically new, the voyage which she was now completing being only her second. Like other ships of her size and time, she was very beamy, with rounded sides that tumbled home to a degree that in these days would be regarded as preposterous. She carried the usual fore and after castles, the latter surmounting the after extremity of her lofty poop. She was rigged with three masts in addition to the short spar which reared itself from the outer extremity of her bowsprit, and upon which the sprit topsail was set, the fore and main masts spreading courses, topsails, and—what was then quite an innovation—topgallant sails, while the mizen spread a lateen-shaped sail stretched along a sloping yard suspended just beneath the top, in the position occupied in these days by the cross-jack. She was armed with twenty-two cannon of various sizes and descriptions, and she mustered a crew of fifty-six men and boys, all told. Her hull was painted a rich orange-brown colour down to a little above the water-line, beneath which ran a narrow black stripe right round her hull, dividing the brown colour of her topsides from her white-painted bottom which, by the way, was now almost hidden by a rank growth of green weed. She carried one large poop lantern, and displayed from her flagstaff the red cross of Saint George, while from her fore and main topgallant-mastheads, from the peak of her mizen, and from the head of her sprit-topmast lazily waved other flags and pennons. As she swung into view round Devil’s Point the blare of trumpets and the roll of drums reached the ears of the crowd which awaited her arrival; but these sounds presently ceased as her crew proceeded to brail up and furl sail after sail; and some ten minutes later, scarcely stemming the outgoing tide, she drifted slowly in toward her berth alongside the wharf. Ropes were thrown, great hawsers were hauled ashore and made fast to sturdy bollards, fenders were dropped overside, and the Bonaventure was very smartly secured abreast the warehouse which was destined to receive her cargo.

Then, when the ship had been securely moored, fore and aft, her gangway was thrown open, a gang-plank was run out from the deck to the wharf, and Mr Richard Marshall, her owner, stepped on board and advanced with outstretched hand toward a short, stout, grey-haired man who had hitherto occupied a conspicuous position on the poop, but who now descended the poop ladder with some difficulty and hobbled towards the gangway.

The contrast between the two men was great in every way, except perhaps in the matter of age, for both were on the shady side of fifty; but while one of them, Mr Richard Marshall, merchant and shipowner, to wit, was still hale and hearty, carrying himself as straight and upright as though he were still in the prime of early manhood, the other, who was none other than John Burroughs, the captain of the Bonaventure, moved stiffly and limped painfully as a result of many wounds received during his forty years of seafaring life, coupled with a rapidly increasing tendency to suffer from severe attacks of rheumatism. And they differed in dress as greatly as in their personal appearance; for while the merchant was soberly if not somewhat sombrely garbed in dark brown broadcloth, with a soft, broad-brimmed felt hat to match, the captain (in rank defiance of the sumptuary laws then existing) sported trunk hosen of pale pink satin, a richly embroidered and padded satin doublet of the same hue, confined at the waist by a belt of green satin heavily broidered with gold thread, from which depended on one side a long rapier and on the other a wicked-looking Venetian dagger with jewelled hilt and sheath, while, surmounting his grizzled and rather scanty locks, he wore, jauntily set on one side, a Venetian cap of green velvet adorned with a large gold and cameo brooch which secured a long green feather drooping gracefully over the wearer’s left shoulder. But let not the unsophisticated reader imagine, in the innocence of his heart, that the garb above described was that usually affected by mariners of the Elizabethan period, while at sea. It was not. But they frequently displayed a weakness for showy dress while in port, and especially when about to go ashore for the first time after the termination of a voyage.

“Welcome home again, Cap’n John,” exclaimed Marshall, grasping the hand of the sailor and wringing it so heartily that poor Burroughs winced at the pain of his rheumatism-racked wrist and shoulder. “I am glad to see you safely back, for I was beginning to feel a bit uneasy lest the King of Spain had caught you in his embargo.”

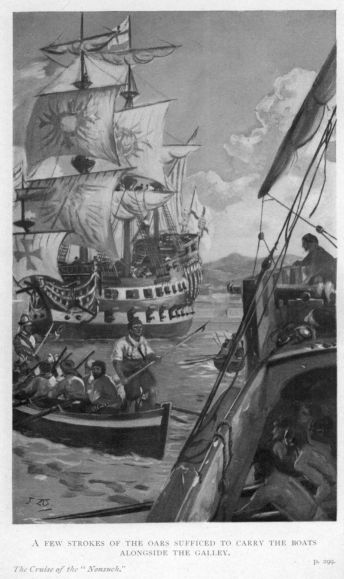

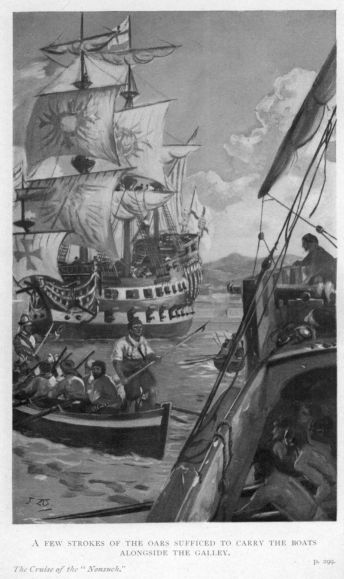

“Iss, fegs; and so mun very nearly did,” answered the captain; “indeed, if it hadn’t ha’ been for young Garge Saint Leger—who, bein’ out of his time, I’ve made pilot in place of poor Matthews, who was killed in a bout wi’ the Barbary rovers on our outward voyage—he’d ha’ had us, sure as pigs baint nightingales. But Garge have got the fiend’s own gift for tongues and languages, and the night avore we sailed he happened to be ashore lookin’ round Santander, and while he were standin’ on one side of a pillar in a church he heard two Spanishers on t’other side of that there same pillar talkin’ about the embargo that King Philip was goin’ to declare again’ the English at midnight that very night as ever was. Like a good boy, Garge waited until the two Spanishers had left the church, and then comed straight down aboard and told me what he’d heard. At first I didn’t put very much faith in the yarn, I’ll own to’t, but that there Garge so pestered and worrited me that at last I let mun have mun’s way; and ten minutes afore midnight the Bonaventure was under way and standin’ out o’ the harbour. We managed to get out without bein’ fired upon by the batteries. But if you’ll believe me, sir, they sent a galley out a’ter us, and if it hadn’t ha’ happened that the wind was blowin’ fresh from about west, and a nasty lump of a beam sea runnin’, dang my ugly buttons if that galley wouldn’t ha’ had us! But the galley rolled so heavy that they couldn’t use their oars to advantage, while the Bonaventure is so fast as any dolphin with a beam wind and enough of it to make us furl our topgallants; so we got away.”

“And a very smart piece of work, too, apparently,” said Mr Marshall. “I must not forget to thank George Saint Leger for his share in it. Has your voyage been a success, Captain?”

“So, so; I don’t think you’ll find much to complain about when we comes to go into the figures,” answered Burroughs. “We had a bit of a brush wi’ the rovers, who comed out against us in three ships, during our outward voyage, but we beat ’em off wi’ the loss of only one man—poor Matthews, as I mentioned just now—since when we’ve had no call to fire a single shot.”

“Excellent, excellent!” commented the merchant, rubbing his hands. “Of course I am very sorry to learn that Matthews was slain; but these things will happen at sea from time to time. Well, to-morrow we will have the hatches off and begin discharging. While that is proceeding I must consider what next to do with the ship; for it will be useless to think of further trade with the Mediterranean while the Spanish embargo lasts, and Heaven only knows how long that will be.”

“Ay,” assented Burroughs. “’Tis a pity that her Grace up to Whitehall can’t make up her mind one way or t’other about this here Spanish business; whether she’ll be friends wi’ Philip, or will fight mun. For all this here shilly-shallyin’, first one way and then t’other, be terrible upsettin’ to folks like we. But there, what be I grumblin’ about? ’Twont make a mort o’ difference to me, because I’ve made up my mind as it’s time for me to knock off the sea and settle down snug and comfortable ashore for the rest of my days. I be that bad wi’ the rheumatics that I’ve got to get the cabin boy to help me put on my clothes, and when there be a sea runnin’ and the ship do roll a bit I can’t sleep for the pain in my j’ints. So, Mr Marshall, I may ’s well give ’e notice, here and now, so’s you’ll ha’ plenty of time to look about ’e for another cap’n.”

“Dear me, dear me! I am very sorry to hear that, Cap’n,” exclaimed Mr Marshall. “But,” he continued, “ever since the declaration of the embargo I have been thinking what I would do with the Bonaventure in the event of her escaping from the Spaniards, and I had almost decided to lay her up until the dispute is settled one way or the other. Now if you stay ashore until that time arrives, and take care of yourself, perhaps you will find yourself quite able to take command of her again when she next goes to sea.”

“No,” asserted Burroughs decisively; “I ha’ made up my mind, and I’ll stick to it. The sea’s no place for a man afflicted as I be. Besides, I ha’ done very well in the matter o’ they private ventures that you’ve allowed me to engage in; there’s a very tidy sum o’ money standin’ to my credit in Exeter Bank, and there’s neither chick nor child to use it a’ter I be gone, so I might so well enjoy it and be comfortable for the rest o’ my days, and at the same time make way for a younger man. Now, there be Garge,” he continued, lowering his tone. “’Tis true that he be but a lad; but he’m a sailor to the tips of his fingers; he’m so good a seaman and navigator as I be; he’ve a-got coolness and courage when they be most needed; he knoweth how to handle a crew; he’ve got the gift of tongues; and—he’m a gentleman, which is a danged sight more than I be. You might do a mort worse, Mr Marshall, than give he the Bonaventure when next you sends her to sea.”

“H’m! do you really think so?” returned the merchant. “He is very young, you know, Captain; too young, I think, to bear the responsibility attending the command of such a ship as the Bonaventure. But—well, I will think it over. Your recommendation of course will carry very great weight with me.”

“Ay, and so’t ought to,” retorted the blunt-spoken old skipper. “I’ve served you now a matter of over thirty years, and you’ve never yet had to find fault wi’ my judgment. And you won’t find it wrong either in that there matter o’ Garge.”

After which the subject was dropped, and the pair proceeded to the discussion of various matters which have no bearing upon the present history.

Meanwhile, during the progress of the above-recorded conversation, the crew, having completed the mooring of the ship, proceeded to furl the sails which had been merely hauled down or clewed up as the craft approached the wharf; and when this job had been performed to the satisfaction of a tall, strapping young fellow who stood upon the poop supervising operations, the mariners laid down from aloft and, the business of the ship being over for the day, were dismissed from duty. As every man aboard the Bonaventure happened to call Plymouth “home,” this meant on their part a general swarming ashore to join the relatives and friends who patiently awaited them on the wharf; whereupon the little crowd quickly melted away.

Then, and not until then, the tall, strapping young fellow upon the poop—familiarly referred to by Captain Burroughs as “Garge,” and henceforth to be known to us as George Saint Leger and the hero of the moving story which the writer proposes to set forth in the following pages—descended to the main deck, uttered a word or two of greeting and caution to the two sturdy ship-keepers who had already come on board to take care of ship and cargo during the absence of the crew, and with quick, springy step, strode to the gang-plank, and so to the wharf, whither the captain, in Mr Marshall’s company, had preceded him.

As he strode along the wharf, with that slight suggestion of a roll in his gait which marks the man whose feet have been long accustomed to the feel of a heaving deck, he cast a quick, eager, recognising glance at the varied features of the scene around him, his somewhat striking countenance lighting up as he noted the familiar details of the long line of quaint warehouses which bordered the wharf, the coasters which were moored ahead and astern of the Bonaventure, the fishing craft grounded upon the mud higher up the creek, the well remembered houses of various friends dotted about here and there, the heights of Mount Edgcumbe shadowy and mysterious in the deepening twilight, and the slopes of Mount Wise across the water; and a joyous smile irradiated his features as his gaze settled upon a small but elegant cottage, of the kind now known as a bungalow, standing in the midst of a large, beautifully kept garden, situated upon the very extremity of the Mount and commanding an uninterrupted view of the Sound. For in that cottage, from three windows of which beamed welcoming lights, he knew that his mother, and perchance his elder brother Hubert, awaited his coming. For a moment he paused, gazing lovingly at the lights, then, striding on again, he quickly reached the end of the wharf and, hurrying down the ferry steps, sprang into a boat which he found lying alongside.

“So you’m back again all safe, Mr Garge, sir,” exclaimed the occupant of the boat as he threw out an oar to bear the craft off from the wharf wall, while young Saint Leger seated himself in the stern sheets. “I been here waitin’ for ’e for the last hour or more. The mistress seed the ship a comin’ in, and knowed her, and her says to me—‘Tom, the Bonaventure be whoam again. Now, you go down and take the boat and go across to the wharf, for Master Garge ’ll be in a hurry to come over, and maybe the wherry won’t be there just when he’s ready to come; so you go over and wait for un.’ And here I be. Welcome home again, sir.”

“Thanks, Tom,” answered Saint Leger, “I did not recognise you for the moment. And how is my mother?”

“She’s just about as well as can be reasonably expected, sir, considerin’ the way that she’s been worritin’ about you and Mr Hubert—’specially ’bout you, sir, since the news of the King of Spain’s embargo have been made known,” answered the man Tom, who was in fact the gardener and general handy man at The Nest, as Mrs Saint Leger’s cottage was named.

“Poor dear soul,” murmured George; “she will fret herself to death over Hu and me, before all’s done, I am afraid. So Captain Hawkins has not yet returned, Tom?”

“Not yet a bain’t, sir. But he’ve only been gone a matter o’ fifteen months; and ’tis only a year since mun sailed from the Guinea coast for the Indies, so ’tis a bit early yet to be expectin’ mun back. When he and Franky Drake du get over there a spoilin’ the Egyptians, as one might say, there be no knowin’ how long they’ll stay there. I don’t look to see ’em back till they’m able to come wi’ their ships loaded wi’ Spanish gould; and it’ll take a mort o’ time to vind six shiploads o’ gould,” returned Tom.

“And has no news of the expedition been received since its arrival on the Spanish Main?” asked George.

“Not as I’ve heard of, sir,” answered Tom. “The last news of ’em was that they’d sailed from the Guinea coast some time about the end of January; and how that comed I don’t know. But I expect ’tis true, because Madam got it from Madam Hawkins, who comed over expressly to tell her.”

“Ah, well, I suppose we shall hear in God’s good time,” commented George. “Back water with your starboard oar, Tom, and pull larboard, or you’ll smash in the bows of the boat against the steps. So! way enough. Haul her to and let me get out. If I am not mistaken there is my mother waiting for me under the verandah. Thanks! Good night, Tom, and put that in your pocket for luck.”

So saying the young man handed Tom a ducat, and sprang out of the boat, up the landing steps, and made his way rapidly up the steep garden path toward the house, beneath the verandah of which a female figure could be dimly seen by the sheen of the lighted windows. As George Saint Leger neared the brow of the slope upon which The Nest was built, this same female figure ran down the verandah steps to meet him, and a moment later he and his mother were locked in each other’s arms.

“My boy, my boy!” crooned Mrs Saint Leger as she nestled in her son’s embrace and tiptoed up to kiss the lips that sought her own—“welcome home again, a thousand welcomes! I saw the ship while she was yet outside Saint Nicholas Island and, with the help of the perspective glass that you brought me from Genoa, was able to recognise her as the Bonaventure. And later, when she rounded the point and entered the Pool, I saw you standing beside Captain Burroughs on the poop, and so knew that all was well with you. Come in, my dear, and let me look at you. Supper is all ready and waiting, and there is a fine big coal fire blazing in the dining-room, for I knew you would feel the air chilly after that of the Mediterranean.”

A moment later the pair entered the warm, cosy dining-room, and stood intently regarding each other by the light of a candelabrum which occupied the centre of the handsomely appointed table. And while they stand thus, with their hands upon each other’s shoulders, each scrutinising the face of the other, we may seize the opportunity to make the acquaintance of both; for with one of them at least we purpose to participate in many a strange scene and stirring adventure in those western Indies, the wonders and fabulous wealth of which were just beginning to be made known to Englishmen through that redoubtable rover and slaver, Captain John Hawkins.

Mrs Saint Leger was a small, somewhat delicate and fragile-looking woman, just turned forty-six years of age, yet, although people seemed to age a great deal more quickly in those days than in these, and although, as the widow of one sailor and the mother of two others, she had known much anxiety and mental stress, she retained her youthful appearance to a degree that was a constant source of wonder to her many friends. Her form was still as girlish as when Hugh Saint Leger proudly led her to the altar twenty-eight years before we make her acquaintance. Her cheeks were still smooth and round, her violet eyes, deep and tender, were still bright despite the many tears which anxiety for her husband and sons had caused her to shed, and which her bitter grief had evoked when, some seven years earlier, the news had been brought to her of her husband’s death while gallantly defending his ship against an attack by Salee pirates. Her golden-brown hair was still richly luxuriant, and only the most rigorous search would have revealed the presence of a silver thread here and there. And lastly, she stood just five feet four inches in her high-heeled shoes, and—in honour of her younger son’s safe arrival home—was garbed, in the height of the prevailing mode, in a gown of brown velvet that exactly matched the colour of her hair, with long pointed bodice heavily embroidered with gold thread, voluminous farthingale, long puffed sleeves, ruffed lace collar, lace stomacher, and lace ruffles at her dainty wrists.

George Saint Leger, aged twenty, stood five feet ten inches in his stockings, though he did not look anything like that height, so broad were his shoulders and so robustly built was his frame. He had not yet nearly attained to his full growth, and promised, if he went on as he was going, to become a veritable giant some five or six years hence. He had his mother’s eyes and hair—the latter growing in short soft ringlets all over his head—and he inherited a fair share also of his mother’s beauty, although in his case it was tempered and made manly by a very square chin, firm, close-set lips, and a certain suggestion of sternness and even fierceness in the steady intent gaze of the eyes. He was garbed, like his captain, in doublet, trunk hose, and cap, but in George’s case the garments were made of good serviceable cloth, dyed a deep indigo blue colour, and his cap—which he now held in his hand—was unadorned with either feather or brooch. Also, he wore no weapons of any kind save those with which nature had provided him.

“Egad! it is good to feel your arms round me, little mother, and to find myself in this dear old room again,” exclaimed the lad as he gazed down into his mother’s loving eyes. “And you—surely you must have discovered the whereabout of the fount of perpetual youth, for you do not look a day older than when I went away.”

“Nonsense, silly boy,” returned the delighted little lady as she freed herself from her stalwart son’s embrace, “art going to celebrate thy return home by beginning to pay compliments to thy old mother? But, indeed,” she continued more seriously, “’tis a wonder that I am not grey-headed, for the anxiety that I have suffered on thy account, George, and that of thy brother Hubert, has scarcely suffered me to know a moment’s peace.”

“Dear soul alive, I’ll warrant that’s true,” agreed George. “But, mother, you need never be anxious about me, for there’s not a better or stauncher ship afloat than the Bonaventure, nor one that carries a finer captain and crew. We’ve held our own in many a stiff bout with weather and the enemy, and can do it again, please God. And as for Hu, I think you need fear as little for him as for me, for with Hawkins as admiral, and Frankie Drake as second in command, with six good ships to back them up, they should be able to sweep the Spanish Main from end to end. It cannot now be very long before one gets news of them, and indeed, I confidently look forward to seeing them come sailing into Plymouth Sound ere long, loaded down with treasure.”

“God grant that it may be so,” responded Mrs Saint Leger. “Yet how can I help being fearful and anxious when I think of those daring men thousands of miles away from home and kindred, surrounded as it were by enemies, and with nought to keep them but their courage and the strength of their own right arm? And where there is fighting—as fighting there must be when English and Spaniards come face to face—some must be slain, and why not our Hubert among them? For the boy is hot-headed, and brave even to recklessness.”

“Ay,” assented George, “that’s true. But ’tis the brave and reckless ones that stand the best chance in a fight, for their very courage doth but inspire the enemy with terror, so that he turns and flees from them. Besides, our lads are fighting God’s battle against bigotry, idolatry, and fiendish cruelty as exemplified in the tortures inflicted upon poor souls in the hellish Inquisition, and ’twould be sinful and a questioning of God’s goodness to doubt that He will watch over them who are waging war upon His enemies.”

“Yea, indeed, that is true,” agreed Mrs Saint Leger. “And yet, so weak is our poor human faith that there are times when my heart is sick with fear as to what may be happening to my dear ones. But here is Lucy with the supper. Draw up and sit down, my son. I’ll warrant that the enjoyment of a good roast capon and ale of thy mother’s own brewing will be none the less for the sea fare upon which thou hast lived of late.”

So mother and son sat down to table again for the first time in many months. And while they ate George regaled his mother with a recital of some of the most moving happenings of the voyage just ended, including, naturally, a detailed account of the brush with Barbary pirates, the death of Matthews, the pilot, and George’s own promotion to the post thus rendered vacant; to all of which Mrs Saint Leger listened eagerly, devouring her son with her eyes as he made play with capon and pasty and good nut-brown ale, talking betwixt mouthfuls and eliciting from his absorbed audience of one, now a little exclamation of horror at the tale of some tragic occurrence or narrow escape, and anon a hearty laugh at the recounting of some boyish frolic and escapade in one or another of the foreign cities visited in the course of the voyage. Supper over, they drew their chairs up before the fire and continued their talk, asking and answering questions in that delightfully inconsequent fashion which is possible only between near and dear relatives after a long separation. So the time passed quickly until the hour-glass in the hall marked ten and the maid brought in candles; whereupon, before separating for the night, mother and son knelt down together and rendered heartfelt thanks to God for the safe return of the one wanderer and offered up equally heartfelt petitions for the preservation of the other, as folk were not ashamed to do in those grand old days when belief in God’s interest in the welfare of His creatures was a living, virile thing, and when a man’s religion was as intimate a part of his daily life as were his meat and drink.

Chapter Two.

How Robert Dyer brought news of disaster.

The following morning found George Saint Leger early astir; for the unloading of the Bonaventure’s rich cargo was now to begin, and he must be there to superintend and do his share of the work. And be sure that Mr Richard Marshall and his head clerk were also there to take note of each bale and cask and package as it was hoisted out of the hold and carried across the wharf into the yawning doorway of the warehouse; for while the worthy merchant fully trusted those of his servants who had proved themselves to be trustworthy, he held that there was no method of keeping trustworthy servants faithful so efficacious as personal oversight; he maintained that the man who tempted another to dishonesty by throwing opportunities for dishonesty in his way, was as guilty and as much to blame as the one who succumbed to temptation; therefore he kept his own soul and the souls of his employés clean by affording the latter as little occasion as might be for stumbling. Captain Burroughs—his rheumatism more troublesome than ever—was also present, with his hands full of invoices and bills of lading to which he referred from time to time for information in reply to some question from Mr Marshall; and soon the winches began to creak and the main hatch to disgorge its contents, while a crowd of those curious and idle loafers who, like the poor, are always with us, quickly gathered upon the wharf to gapingly watch the process of unloading the cargo.

That process was much more deliberately carried out then than it is in the present day of hurry and rush, steam and electricity; therefore it was not until nearly a fortnight had elapsed that the last bale had been hoisted out of the Bonaventure’s hold and safely stored in Mr Marshall’s warehouse. Mr Marshall had definitely announced his intention to lay up the ship until the Spanish embargo should be raised. And it was on that same night that, as George and his mother sat chatting by the fire after supper, the maid Lucy entered the room with the intimation that a strange, foreign-looking man, apparently a sailor, stood without, craving speech with Mistress Saint Leger.

Mrs Saint Leger’s apprehensions with regard to the safety of Hubert, her elder son, temporarily allayed by George’s optimism, were quick to respond to the slightest hint or suggestion of disaster; the mere mention, therefore, of a man, foreign-looking and of sailorly aspect, seeking speech with her, and especially at such an untimely hour, was sufficient to re-awaken all her unformed fears into full activity. Her lips blanched and a look of terror leapt into her eyes as she sprang to her feet, regarding the somewhat stolid Lucy as though the latter were some apparition of ill omen.

“A sailor, say you, strange, and foreign-looking?” she gasped. “What for mercy’s sake can such a man want with me at this time of night? Did you ask the man his name?”

“No, ma’am, I—I—didn’t,” stammered the maid, astonished at her mistress’s unusual agitation, and afraid that in omitting to make the enquiry she had been guilty of some terrible oversight; “he said—he—”

But at this point George intervened. To him, as to his mother, the circumstance had at once conveyed a suggestion of ominousness, a hint of possible evil tidings. Like his mother, he had risen to his feet as the thought of what this visit might mean dawned upon him. But, unlike Mrs Saint Leger, he was accustomed to act quickly in the presence of sudden alarms, and now he laid his hand reassuringly upon his mother’s shoulder, as he said soothingly:

“There, there, sit you down, mother; there’s nought to be frightened about, I’ll warrant. Sit you down, again; and I’ll go out and speak to the fellow. Maybe ’tis but some sneaking, snivelling beggar-man who, believing you to be alone here, hopes to terrify you into giving him a substantial alms.”

So saying, with another reassuring pat upon his mother’s shoulder, the lad stalked out of the room, pushing the bewildered maid before him, and made his way to the front door, where Mrs Saint Leger, acutely listening, presently heard him in low converse with the stranger. The conversation continued for a full ten minutes, and then Mrs Saint Leger’s apprehensions were sharpened by hearing footsteps—her son’s and another’s—approaching the room in which she sat. A moment later the door was flung open, and George, pale beneath his tan, re-appeared, ushering in a thick-set, broadly-built man of medium height, whose long, unkempt hair and beard, famine-sharpened features, and ragged clothing told an unmistakable tale of privation and suffering.

“Mother,” said George—and as he spoke his lips quivered slightly in spite of his utmost efforts to keep them steady—“this man is Robert Dyer of Cawsand, one of the crew of the Judith, Captain Drake’s ship, just arrived from the Indies, and he brings us bad news—not the worst, thank God,” he interjected hurriedly as he noted Mrs Saint Leger’s sudden access of pallor—“but bad enough for all that, and it is necessary that you should hear it. The expedition has been a failure, thanks to Spanish treachery; the loss to the English has been terribly heavy, and several of the men are missing.”

For a few moments the poor distracted mother strove vainly to speak; then, clutching George’s arm tightly, she moaned: “Well, why do you pause, George? Tell me the worst, I pray you. I can bear it. Do not keep me in suspense. Do you wish me to understand that Hubert is killed—or is he among the missing? He must be one or the other, I know, or he would be here now to tell his own story.”

“He is a prisoner in the hands of the Spaniards, mother,” answered George. “But be of good cheer,” he continued, as Mrs Saint Leger staggered like one struck and he sprang to her assistance—“sit you down, mother, and let Dyer here tell us his story. I have only just heard the barest outline of it. Perhaps when we have heard it all it may not seem so bad. And don’t you fear for Hubert, dearie; ’tis true that the Spaniards have got him, but they won’t dare to hurt him, be you assured of that; and likely enough he will have escaped by this time. Now, Dyer, come to an anchor, man, and tell us all that befell. And while you’re talking we’ll have some supper prepared for you.”

“Well, madam, and Mr Garge, there ain’t so very much to tell,” answered Dyer, seating himself in the chair which Saint Leger had indicated. “Of course you do both know—all Plymouth knows—that we sailed away from this very port a year ago come the second o’ last October. Six ships strong, we was, well manned, and an abundance o’ munitions o’ war of every kind, even to shore-artillery. And we had Cap’n John Hawkins for our admiral and Frank Drake for our pilot, so what more could a body want?

“We made a very good passage to the Canary Islands, which was our first rondyvoo; and from there, a’ter we’d wooded and watered afresh, and set up our rigging, we sailed for the Guinea coast. On our way there, avore ever we got so far south as Cape Blanc, we captured a Portingal caravel; pickin’ up another of ’em a little way to the nor’ard of Cape Verde. This here last one was called the Grace a Dios, she were a very fine new ship of a hunderd and fifty ton—and we kept ’em both because, bein’ light-draught ships, the admiral knowed they’d be useful for goin’ in over bar on the Coast, where the mouths of the rivers be always shallow.

“Well, in due time—I forget the exact date, now—we arrived on the Coast, and there we stayed for a matter o’ three months, huntin’ blacks and Portingals; goin’ into the rivers in the caravels, landin’ parties, attackin’ native villages, and makin’ prisoners o’ all the strongest and most likely-lookin’ men and women—with a good sprinklin’ o’ childer, too—and cuttin’ out the Portingal caravels wherever we found ’em. Ah! that work o’ boardin’ and cuttin’ out the Portingals! It was fine and excitin’, and suited Cap’n Drake and Mr Saint Leger a sight better than nagur huntin’. They was always the first to come forward for such work, and never was two men so happy as they was when news was brought of a caravel bein’ near at hand.

“Three months we stayed on that there terrible Guinea coast, and durin’ that time we got together over five hunderd nagurs, besides takin’, plunderin’, and burnin’ more than a dozen caravels. Then, wi’ pretty nigh half of our company down wi’ fevers and calentures taken on the Coast and in the rivers, we all sailed for the Spanish Main. A matter o’ seven weeks it took us to cross to t’other side o’ the world, although we had fair winds and fine weather all the way, as is usual on the voyage from Africa to the Indies. Then we arrived at a lovely island called Margarita, one o’ the Spaniards’ Indian possessions, where I was told they find pearls. Here we found several storehouses crammed with food of all sorts and great casks o’ wine intended for distribution among the ports of the Spanish Main; and here our admiral decided to re-victual the fleet. And mun did, too, in spite of the objections o’ the Spaniards, who vowed that they had no food to spare. We took from ’em all that we wanted, but we paid for it in good Portingal goold, seein’ that we was no pirates, but good honest traders.

“Then we sailed westward again, past La Guaira and the great wall of mountains that tower aloft behind it far into the deep blue sky. On the third day after leavin’ Margarita we sailed into as snug a little harbour as you’d wish to see. And there we stayed for a matter o’ two months, landin’ our sick and our blacks, clearin’ out our ships’ holds, cleanin’, careenin’, scrapin’, paintin’, overhaulin’, and refittin’ generally, the blacks helpin’ us willin’ly enough when we made ’em understand what we wanted done.

“By the time that we’d a done everything that we wanted to, our sick had got well again—all except four what died in spite of us—and then we put to sea again, coastin’ along the Main and callin’ in here and there to trade our blacks for goold and pearls. But at first the trade weren’t at all good; and bimeby the admiral lost patience wi’ the silly fules and vowed he’d make ’em trade wi’ us, whether they wanted to or no; so we in the Judith and another ship were sent round to a place called La Hacha. When we arrived and made to enter, the forts opened fire upon us! So we and t’other ship blockaded the place for five days, sufferin’ nothin’ to go in or come out; and then along come the admiral wi’ the rest o’ the ships, and we got to work in earnest. The shore-artillery and two hunderd soldiers was landed, the batteries was stormed, and we took the town, drivin’ all the Spaniards out of it; and be sure that Cap’n Drake and Mr Saint Leger was among the first to get inside. That was enough for they Spanishers; a’ter that they was ready enough to trade wi’ us; and indeed that same night some of ’em comed back, bringin’ their goold and their pearls with ’em; and avore we left the place we’d parted wi’ no less than two hunderd blacks.

“And so things went on until we’d a sold every black that remained; and by that time we’d got so much goold and so many pearls that the admiral was afeard that if we tried to get more we mid lose all, and accordin’ly, a’ter holdin’ a council o’ war, it was decided to make for whoam, and we bore away up north to get into the Gulf Stream to help us to beat up again’ the easterly winds that do blow always in them parts. But, as it turned out, we couldn’t ha’ done a worse thing. For we’d no sooner weathered Cape Yucatan than there fell upon us two o’ the most awful gales that mortal man can pictur’, pretty nigh all our canvas was blowed clean out of the bolt-ropes, some o’ the ships was dismasted, the sea—well, I don’t know what I can compare it to, unless ’tis to mountains, it runned so high; and as for the poor little Judith, ’twas only by the mercy o’ God and Cap’n Drake’s fine seamanship that she didn’t go straight to the bottom. By the time that them there hurricanes was over the ships was not much better nor wrecks, and ’twas useless to think o’ makin’ the v’yage home in ’em in that condition, so our admiral made the signal to bear up and run for San Juan de Ulua. And when we arrived there, if you’ll believe me, madam and Mr Garge, we found no less than twelve big galleons, loaded wi’ goold an’ silver, waitin’ for the rest o’ the Plate fleet and its convoy to sail for Old Spain! And the very next day the ships as was expected arrived off the port and found us English in possession!

“Then there was a pretty to-do, you may take my word for ’t. Some o’ the cap’ns—Mr Saint Leger and Cap’n Drake among ’em, I believe—was for attackin’ the convoy and takin’ the whole o’ the Plate fleet; and, as things turned out, ’twould ha’ been better if we’d done it, for, disabled though our ships were, we could ha’ fought at our anchors and kept the convoy from enterin’ the port. But the admiral wouldn’t hear o’ it; he kept on declarin’ that we was honest traders, and that to capture the Spanish ships ’d be a hact of piracy which would get us into no end o’ trouble to home, and perhaps bring about war betwixt England and Spain; and at last t’others give in to mun and let mun have mun’s own way. Then there was goin’s to an’ fro between our ships and the shore, and I heard say as that the admiral were negotiatin’ wi’ the Viceroy for permission for our ships to stay where they was, and refit; and at last ’twas agreed that we was to be allowed to so do, provided that we didn’t interfere wi’ the Spanish ships.

“That bein’ arranged, the rest of the Plate fleet and the convoy sailed into the harbour and anchored, while we English got to work clearin’ away our wrecked spars, sendin’ down yards, and what not. The Judith bein’ a small ship, Cap’n Drake took her in and moored her alongside a wharf upon which we stowed part of our stores and water casks, so ’s to have more room for movin’ about on deck; but as for the rest, they’d to do the best they could while lyin’ off to their anchors. And one of the first things that we did was to transfer all the goold and pearls that we’d collected to the Jesus. Three days we laboured hard at the work of refittin’, and then, when most o’ our biggest ships was so completely dismantled that they hadn’t a spar aloft upon which to set a sail, them treacherous Spaniards, carin’ nothin’ for their solemn word and promises, must needs attack us, openin’ fire upon us both from the ships and the forts, while a party o’ soldiers came marchin’ down to the wharf especially to attack us of the Judith’s crew. When Cap’n Drake see’d mun comin’ he at once ordered all hands ashore; and while he and Mr Saint Leger and a few more did their best to keep off the soldiers, the rest of us went to work to put the provisions and water back aboard the Judith. But we’d only about half done our work when a lot more soldiers comed swarmin’ down, and Cap’n Drake sings out for everybody to get aboard and to cast off the hawsers—for by this time there was nigh upon five hunderd Spaniards attackin’ us, and we could do nothin’ again so many. Seein’ so many soldiers comin’ again us, some of our chaps got a bit frighted and took the cap’n at his word by castin’ off our shore fasts at once, without waitin’ for everybody to get aboard first. The consequence was that when all the hawsers had been let go exceptin’ the quarter rope—which I was tendin’ to—the Cap’n, Mr Saint Leger, and about half a dozen more was still on the wharf while—an off-shore wind happenin’ to be blowin’ at the  time—the ship’s head had paid off until ’twas pointing out to sea, while there was about a couple o’ fathoms of space atween the ship’s quarter and the wharf. I s’pose that seein’ this, and that there was only a matter o’ seven or eight men to oppose ’em, gived the Spaniards courage to make a rush at the Cap’n and his party; anyway, that’s what they did, and for about a couple o’ minutes there was a terrible fight on that wharf, in which three or four men went down.

time—the ship’s head had paid off until ’twas pointing out to sea, while there was about a couple o’ fathoms of space atween the ship’s quarter and the wharf. I s’pose that seein’ this, and that there was only a matter o’ seven or eight men to oppose ’em, gived the Spaniards courage to make a rush at the Cap’n and his party; anyway, that’s what they did, and for about a couple o’ minutes there was a terrible fight on that wharf, in which three or four men went down.

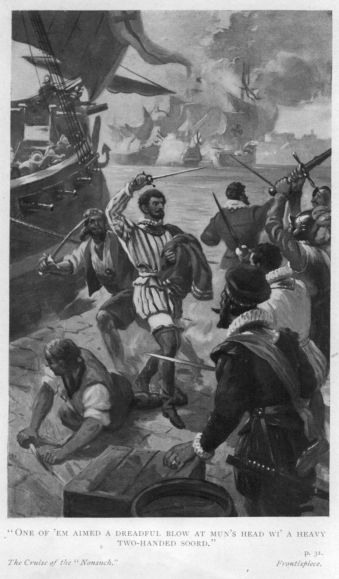

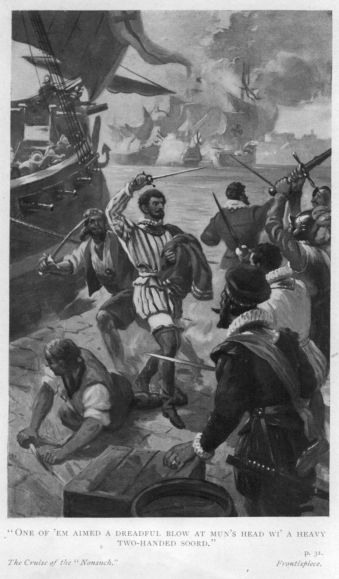

“The next thing I noticed, Mr Garge, were your brother layin’ about mun like a very Paladin, fightin’ three big Spanish cavaliers single-handed, and, while I watched, one of ’em aimed a dreadful blow at mun’s head wi’ a heavy two-handed soord. Mr Hubert see’d the blow comin’ and put up his soord to guard the head of mun, but the soord broke off clean, close to the hilt, and there were Mr Hubert disarmed. Then the three Spaniards that was fightin’ mun rushed in afore Mr Hubert could draw his dagger, seized mun by the arms, and dragged mun away out o’ the fight. And while this were happenin’ our Cap’n were so busy that I don’t believe he ever see’d that Mr Hubert were took prisoner. Then I sang out to mun—‘Cap’n Drake,’ says I, ‘if you don’t come aboard this very minute,’ says I, ‘the ship’ll break adrift and go off and leave ye behind.’ The Cap’n took a look round, see’d that evrybody else but hisself was either cut down or took prisoner, and, flinging his soord in the face of a man that tried to stop mun, leaped clean off quay, seized the hawser in ’s hands as mun jumped, and come aboard that way, hand over hand. Then I let go the hawser and jumped to the helm, and we runned off among t’other ships, where we let go our anchor.

“Now by this time the fight were ragin’ most furious everywhere, some of the Spanish havin’ got under way and runned our ships aboard. But they didn’t gain much by that move, for though they sank three of our ships, we sank four of them and reduced their flag-ship to a mere wreck, while their losses in men must ha’ been something fearful. But although we gived ’em such a punishin’, we, bein’ the weakest, was gettin’ the worst o’ it; and bimeby, when they took to sendin’ fireships down to attack us, the admiral thought ’twas time to make a move, so he signalled that such ships as could get to sea was to do so. Accordin’ly, all that was left of us cut our cables, and made sail as best we could, the Jesus leadin’ the way, we in the Judith goin’ next, and the Minion comin’ last and coverin’ our retreat.

“But that didn’t end our troubles by any manner o’ means, for we’d scarcely got clear of the land when the Jesus was found to be so riddled and torn wi’ shot that we only just had time to take her crew off of her when down she went, takin’ with her all the treasure that we’d gathered together durin’ the voyage. Then we parted company wi’ the Minion, and whether she’s afloat, or whether she’s gone to the bottom, God only knows, for I hear that she haven’t arrived home up to now.”

“And when did the Judith arrive?” demanded George, when it became evident that Dyer had brought his story to an end.

“Not above two hours agone,” answered the man. “We got in a’ter dark, and come to an anchor in the Hamoaze; and so anxious were the cap’n to report that he wouldn’t wait till to-morrer, but must needs have a boat lowered and come ashore to see Cap’n William Hawkins to-night. And he bade me walk over here to see madam, give her the news, and say, wi’ his dutiful respec’s, that if time do permit he will call upon her some time to-morrer, to answer any questions as she may wish to ast him.”

“One question which I shall certainly want to ask him will be how it came about that he was so careful to provide for his own safety without making any effort to rescue my son,” remarked Mrs Saint Leger, in a low, strained voice.

“Nay, madam, by your leave, you must not ask mun that,” answered Dyer. “I, who saw everything, saw that the cap’n could not ha’ rescued Mr Hubert, had he tried ever so. He could not ha’ saved Mr Hubert, and if he’d been mad enough to try he’d only ha’ been took hisself. Moreover, from what he’ve a said since ’tis clear to me that he thought Mr Hubert had got safe aboard, or he’d never ha’ left mun behind. I knowed that by the grief o’ mun when he was first told that Mr Hubert had been took.”

“What do you suppose the Spaniards will do with my brother?” impulsively asked George, and could have bitten his tongue out the next moment for his imprudence in asking such a question in his mother’s presence. For Dyer was a blunt, plain-spoken, ignorant fellow, without a particle of tact, as young Saint Leger had already seen, and he knew enough of Spanish methods to pretty shrewdly guess what the reply to his question would be. And before he could think of a plan to avert that reply, it came.

“Well, Mr Garge,” answered Dyer, “you and I do both know how the Spaniards do usually treat their prisoners. I do reckon they must ha’ took a good twenty or thirty o’ our men, and I don’t doubt but what they’ll clap the lot into th’ Inquisition first of all. Then they’ll burn some of ’em at an auto-da-fé; and the rest they’ll send to the galleys for life.”

“What sayest thou?” screamed Mrs Saint Leger, starting to her feet and wringing her hands as she stared at Dyer in horror, as though he were some dreadful monster. “The Inquisition, the auto-da-fé, the galleys for my son? George! I conjure you, on your honour as an Englishman, tell me, is it possible that these awful things can be true?”

For a second or two George hesitated, considering what answer he should return to his mother’s frenzied question. He knew that the horrors suggested by Dyer were true, and the knowledge that his brother was exposed to such frightful perils—might even at that precise instant be the victim of them—held him tongue-tied, for how could he confirm this blunt-spoken sailor’s statement, knowing that if he did so he would be condemning his dearly-loved mother to an indefinite period of heart-racking anguish and anxiety that might well end in destroying her reason if indeed it did not slay her outright? He was as strictly conscientious as most of his contemporaries, but he could not bring himself to condemn his mother to the dreadful fate he foresaw for her if he told her the bald, unvarnished truth. He knew, by what he was himself suffering at that moment, what his mother’s mental agony would be if he strictly obeyed her, therefore he temporised somewhat by replying:

“Calm yourself, mother dear, calm yourself, I beg you. There is no need for us to be unduly anxious about Hubert. I will not attempt to conceal from you that he is in evil case, poor dear fellow—all Englishmen are who fall into the hands of the Spaniards, especially if they happen to be Protestants—and I greatly fear me that some of those who were taken with Hu may be in grave peril of those dangers of which Dyer has spoken. But not Hubert. Hubert was an officer, and it is very rare for even Spaniards to treat captive officers with anything short of courtesy. I fear that our dear lad may have to endure a long term of perhaps rigorous imprisonment; he may be condemned to solitary confinement, and be obliged to put up with coarse food; but they will scarcely dare to torture him, still less to condemn him to the auto-da-fé. Oh, no, they will not do that! But while Dyer has been talking, I have been thinking, and my mind is already made up. Hubert must not be permitted to languish a day longer in prison than we can help. Therefore I shall at once set to work to organise an expedition for his rescue, and trust me, if he does not contrive to escape meanwhile—as he is like enough to do—I will have him out of the Spaniards’ hands in six months from the time of my departure from Plymouth.”

At the outset Dyer had listened to George’s speech in open-mouthed amazement, and some little contempt for what he regarded as the young man’s ignorance; but even his dense intellect could not at last fail to grasp the inward meaning and intention of the speaker; a lightning flash of intelligence revealed to him that it was not ignorance but a desire to spare his mother the anguish of long-drawn-out anxiety and the agony resulting from the mental pictures drawn by a woman’s too vivid imagination; and forthwith he rose nobly to the exigencies of the occasion by chiming in with:

“Ay, ay, Mr Garge, you’m right, sir. Trust your brother to get away from they bloody-minded Spaniards if they gives him half a chance. For all that we knows he may ha’ done it a’ready. And if he haven’t, and you makes up your mind to fit out an expedition to go in search of mun, take me with ye, sir. I’ll sarve ye well as pilot, Mr Garge, none better, sir. I’ve been twice to the Indies wi’ Cap’n Drake, once under Cap’n Lovell and now again under Cap’n Hawkins. And I’ve a grudge to pay off again’ the Spaniards; for at La Hacha they played pretty much the same trick upon Cap’n Lovell as they did this time upon Cap’n Hawkins.”

“Aha! is that the case?” said George. “Then of course you know the Indies well?”

“Ay, that do I, sir,” answered Dyer, “every inch of ’em; from Barbadoes and Margarita, all along the coast of the Main right up to San Juan de Ulua there ain’t a port or a harbour that I haven’t been into. I do believe as I knows more about that coast than the Spaniards theirselves.”

“Very well, Dyer,” returned George. “In that case you will no doubt be a very useful man to have, and you may rest assured that, should I succeed in organising an expedition, I will afford you the opportunity to go with me. Ah! here comes your supper at last—” as the maid Lucy appeared with a well-stocked tray—“Draw up, man, and fall to. You must stay with us to-night—is not that so mother?” And upon receiving an affirmative nod from his mother the young man continued—“and to-morrow I will send you over to Cawsand in our own boat.”

Whereupon, Dyer, pious seaman that he was, having first given God thanks for the good food so bountifully set before him, fell upon the viands with the appetite of a man who has been two months at sea upon less than half rations, and made such a meal as caused Mrs Saint Leger to open her eyes wide with astonishment, despite the terrible anxiety on behalf of her first-born that was tugging at her heart-strings and setting every nerve in her delicate, sensitive frame a-jangle. And, between mouthfuls, the seaman did his best to reply to the questions with which George Saint Leger plied him; for it may as well be set down here at once that no sooner did the youngster learn the fact of his capture by the Spaniards than he came to the resolution to rescue Hubert, if rescue were possible; and, if not, to make the Spaniards pay very dearly for his death. But to resolve was one thing, and to carry out that resolution quite another, as George Saint Leger discovered immediately that he took the first steps toward the realisation of his plan—which was on the following morning. For he was confronted at the very outset with the difficulty of finance. He was a lad of rapid ideas, and his knowledge of seafaring matters, and the Spaniards, had enabled him to formulate the outlines of a scheme, even while listening to Dyer’s relation of the incidents of Hawkins’ and Drake’s disastrous voyage. But he fully recognised, even while planning his scheme, that to translate it into action would necessitate an expenditure far beyond his own unaided resources. True, his mother was very comfortably off, possessing an income amply sufficient for all her needs derived from the well-invested proceeds of her late husband’s earnings, but George was quite determined not to draw upon that if he could possibly help it, although he was well aware that Mrs Saint Leger would be more than willing to spend her last penny in order to provide the means of rescuing her elder son from a fate that might well prove to be worse than death itself. Therefore the younger Saint Leger began operations by calling upon Mr Marshall, the merchant and owner of the Bonaventure, and, having first ascertained that that gentleman had definitely, though reluctantly, decided not to risk his ship in another Mediterranean voyage so long as the relations of England and Spain continued in their then strained condition, unfolded a project for an adventure to the Indies, which, if successful, must certainly result in a golden return that would amply reimburse all concerned for the risks involved. But Mr Marshall had not grown from an errand boy into a prosperous merchant without acquiring a certain amount of wisdom with his wealth, and he at once put his finger on the weak spot in George’s proposal by inquiring what guarantee the latter could offer that his scheme would be successful when a very similar one conducted by such experienced adventurers as Hawkins and Drake had just disastrously failed. He frankly admitted that the young man’s scheme was promising enough, on the face of it, and he also intimated that, as a merchant, he was always ready to take a certain amount of risk where the prospects of success seemed promising enough to justify it, but he no less frankly declared that, while he had the utmost confidence in George’s ability as a seaman, he regarded him as altogether too young and inexperienced to be the head and leader of such an adventure as the one proposed; and he terminated the interview by flatly refusing to have anything to do with it.

Bitterly disappointed at his failure to enlist Marshall’s active sympathy, George called upon some half a dozen other Plymouth merchants. But everywhere the result was the same. The adventure itself met with a certain qualified approval, but the opinion was unanimous that George was altogether too young and inexperienced to be entrusted with its leadership. In despair, George at last called upon Mr William Hawkins, the father of Captain John Hawkins, to obtain his opinion upon the project. Captain John had arrived home a day or two previously, and young Saint Leger was so far fortunate that he was thus able to obtain the opinion of both father and son upon it. As might have been expected, although these two seamen were friends of the Saint Legers, they were so embittered by disappointment at the failure of the recent expedition that they could not find words strong enough to denounce the scheme and to discourage its would-be leader, and so well did they succeed in the latter that for an hour or two George was almost inclined to abandon the idea altogether. Yet how could he reconcile himself to the leaving of his brother to a fate far worse than death itself—for though he had sought to make the best of the matter to his mother, he himself had no illusions as to what that fate would be—and how could he face his mother with such a suggestion? The lad had infinite faith in himself, He knew, better than anybody else, that he had never yet had an opportunity to show of what stuff he was made, he candidly admitted the damaging fact of his extreme youth, but he would not admit to himself that it was a disability, although others regarded it as such; he had been a sailor for seven years and during that time he had mastered the whole of the knowledge that then went to make the complete seaman; moreover, he was also old for his years, a thinker, and he carried at the back of his brain many an idea that was destined to be of inestimable value to him in the near future; therefore, after a long walk to and fro upon the Hoe, he returned home, disappointed it is true, but with his resolution as strong and his courage as high as ever.

And here he found balm and encouragement awaiting him in the person of one Simon Radlett, a shipbuilder, owning an extensive yard at Millbay.

“Old Si Radlett,” as he was generally called, was something of a character in Millbay and its immediate neighbourhood, for, in addition to being admittedly the best builder of ships in all Devon, he was a bit of an eccentric, a man with bold and original ideas upon many subjects, a man of violent likes and dislikes, a bachelor, an exceedingly shrewd man of business, and—some said—a miser. He was turned sixty years of age, and of course had seen many and great changes in Plymouth during his time, yet, although well advanced in the “sere and yellow,” was still a hale and hearty man, able to do a hard day’s work against the best individual in his yard; and although he had the reputation of being wealthy he lived alone in a little four-roomed cottage occupying one corner of his yard, and did everything—cooking, washing-up, bed-making, etcetera, etcetera, for himself, with the assistance of a woman who came, for one day a week, to clean house, and wash and mend for him. He had known George Saint Leger from the latter’s earliest childhood, and had loved the boy with a love that was almost womanly in its passionate devotion, nothing delighting him more than to have the sturdy little fellow trotting after him all over the yard, asking questions about ships and all things pertaining thereto.

He it was who had presented George with the toy ship that still occupied a conspicuous position in the latter’s bedroom at The Nest, and which was such a gorgeous affair, with real brass guns, properly made sails, and splendid banners and pennons of painted silk, that the child had never cared to have another. And the affection which the old man had manifested for the child had endured all through the years, and was as strong to-day as it ever had been, yet such was Radlett’s reputation for close-fistedness that it had never once occurred to George that he might possibly be willing to help him, consequently he had not sought him. No sooner, however, did the youngster enter the house and discover the old tarry-breeks in close and animated conversation with Mrs Saint Leger than his spirits rose; for it had been years since Radlett had so far presumed as to actually call upon madam, and George somehow felt intuitively that such an unwonted and extraordinary circumstance was in some way connected with the realisation of what had now become his most ardent desire.

Chapter Three.

How old Simon Radlett made a certain proposition to George.

“Well, Garge, my son, so you’m safe whoam again,” exclaimed the old shipbuilder, rising to his feet with outstretched hand, as young Saint Leger entered the room. “My word!” he continued, allowing his gaze to rove over the lad’s stalwart frame, “but you’m growed into a reg’lar strapper, and no mistake; a reg’lar young Goliath of Gath a be, no less. And you’ve been a slayin’ of a Philistine or two, here and there, so I do hear” (Mr Radlett was a little mixed in the matter of his Bible imagery, you will perceive, but he meant well). “Ay, ay; I’ve been havin’ a crack wi’ old Cap’n Burroughs, since mun comed whoam, and he’ve a been tellin’ me all about ye. Garge, I’m proud of ’e, boy—and so be madam here, too, I’ll be boun’—for ’twas I that made a sailor of ’e by givin’ of ’e thicky toy bwoat, a matter o’ twelve or vourteen year agone ’tis now. My goodness me! how time du vly, to be sure. It du seem to me only like a vew months ago that I took spokeshave and chisel in hand to make thicky bwoat, and here you be, a’most a man in years, and quite a man in experience as I du hear.

“Wi’ madam your mother’s good leave, I’ll ask ’e to sit down, Garge, for I be comed over expressly to have a talk with ’e. And, first, let me say to ’e—as I’ve already said to madam, here—how sorry I be to hear of what ha’ happened to your brother, Mr Hubert. But—as I was sayin’ to madam when you comed in—you’ll soon have mun out o’ Spanish prison again, for I do hear as you’m arrangin’ an adventure expressly for that purpose.”

“I certainly want to arrange such an adventure, if the thing can be managed,” replied George; “but I have got no farther than wanting, as yet. I have called upon Mr Marshall, the owner of the Bonaventure, and some half-dozen other merchants, and tried to interest them in my scheme, but all to no purpose. They say that I am much too young to be entrusted with the responsibility of heading such an adventure.”

“Too young be danged!” exclaimed Radlett with energy.

“They don’t know ’e as well as I do, Garge, or they wouldn’t talk like thicky. Why, old Cap’n Burroughs told me hisself that if it hadn’t ha’ been for you the Bonaventure ’d ha’ been in the Spaniards’ hands to-day, and all hands o’ her crew, too. Too young? Rubbidge! Now, just you tell thicky plan o’ yours to me, and I’ll soon tell ’e whether I do think you’m too young, or not. And I be an old man; I’ve seed a good many strange happenin’s in my time, and I’ve drawed my own conclusions from ’em; I’m just so well able to form a sound opinion as Alderman Marshall or any other man to Plymouth. Now, Garge, you just go ahead, and when you’ve a done I’ll tell ’e what I do think of your plan, and you too.”

“Well,” replied George, “it is simple enough. My brother was taken prisoner in the course of a treacherous attack made by the Spaniards upon a party of peaceful English traders; therefore I take the ground that his relatives are entitled to demand his release, together with compensation for any suffering or inconvenience that may have resulted from the treacherous action of the Spaniards. I learned, only to-day, that the Queen has already demanded satisfaction for the outrage from the Spanish Ambassador. But we all know what that means. The negotiations may go on for years, and the demand may be withdrawn in the end if by so doing the interests of diplomacy may be served. Therefore I do not propose to wait for that—for who trows what may happen to my brother in the interval? My plan is this: I intend to go on trying until I can find somebody sufficiently interested in my scheme either to advance me the money, or to entrust me with a ship. Then I will get together a crew who will be willing to go with me, taking a certain share of the proceeds of the expedition in lieu of wages—and I believe I shall be able to raise such a crew without difficulty—and I shall sail direct to San Juan de Ulua. Arrived there, I shall make a formal demand for my brother’s immediate release. And if the Spaniards refuse, or attempt to put me off by saying that they do not know what has become of Hubert, I will at once attack the town, take it, and hold it for heavy ransom. And if ransom is refused, I will sack the place, taking every piece of gold or silver and every jewel that I can lay hands upon. And from there I will traverse the entire coast of the Spanish Main, attacking every town that promises to be worth while, until I have succeeded in persuading the Spaniards that it will be to their advantage to free my brother and deliver him over to me.”

“And, supposin’ that they should deliver up your brother at the first town you call at—San Juan de Ulua, I think you named the place—what’ll you do then, boy?” demanded Radlett.

“I shall still require compensation for my brother’s seizure,” replied George. “And,” he added, “that compensation will have to be amply sufficient not only to recompense Hu for his imprisonment, but also to pay handsomely all connected with the expedition. It is my intention, sir, not to return home until I can replace every pig of iron ballast in my ship with gold and silver.”

“Hear to him! hear to him! Gold and silver, quotha!” exclaimed Radlett, delightedly. “And how big’s thy ship to be, then, eh, Garge?”

“The biggest that I can get,” answered George; “the bigger the better, because she will carry the more men, the more guns—and the more gold. I should have liked the Bonaventure, if I could have got her, for I’m used to her, and she is just the right size. But Mr Marshall will have nothing to do with me and my scheme.”

“Ay, the Bonaventure,” remarked the shipwright, meditatively. “Iss, her be a very purty ship, very purty indeed. What be her exact tonnage, Garge?”

“One hundred and twenty-seven,” answered George. “Yes,” he agreed, “she is a pretty ship in every way, and as good as she is pretty. And fast! There’s nothing sailing out of Plymouth that can beat her—although perhaps I ought not to say as much to you, Mr Radlett, seeing that ’twas Mr Mason, your rival, who built her.”

“Never mind vor that, boy, never mind vor that,” answered Radlett, heartily. “’Tis true what you do say of the ship, every word of it; and she be a credit to the man who built her, although he do set up to be my rival. But ’twont be true very much longer, Garge, for I’ve a-got a ship upon my stocks now as’ll beat the Bonaventure every way and in all weathers. I’ve a called her the Nonsuch, because there’s never been nothin’ like her avore. I drawed out the plans of her shortly a’ter the Bonaventure was launched, because I couldn’t abear to be beaten by Mason nor nobody else. And I altered they plans, and altered ’em, and altered ’em until I couldn’t vind no more ways of improvin’ of ’em, and then I started to build. And now the Nonsuch be just ready for launchin’, and I’d like you to come over and look at her avore I puts her into the water.”

“Certainly; I will do so with very great pleasure,” answered George, delightedly, for he had a very shrewd suspicion that this invitation meant more than appeared upon the surface, that indeed—who knew?—it might mean that the eccentric old fellow was rather taken with his (George’s) scheme, and might be induced to take a very important hand in it. “When shall I come?”

“Come just so soon as ever you can, the sooner the better; to-morrow if you do like,” answered Radlett. “And now,” he continued, rising, “I must be gettin’ along, for ’tis growin’ late and I be keepin’ of you from your supper. No, thank’e, madam, I won’t stay. My supper be waitin’ vor me to whoam, and a’ter I’ve had it I’ve a lot o’ things to do that won’t wait for time or tide. So good-bye to ’e both. And you, madam, keep up your spirits about Mr Hubert; for I’ll warrant that Garge, here, ’ll have mun out o’ Spanish prison in next to no time.”

George was up and stirring betimes on the following morning, and, after an early breakfast, set out for Mr Radlett’s shipyard at Millbay. He found the old man busily engaged upon certain papers in the little room which he dignified with the name of “office”; but upon George’s appearance the old fellow hastily swept the documents pell-mell into a drawer, which he locked. Then, pocketing the key, he led the way to the back door of the house, which gave upon the shipyard, upon passing through which young Saint Leger immediately found himself in the midst of surroundings that were as familiar to him as the walls of his own home. But he had no time just then to gaze about him reminiscently, for immediately upon entering the shipyard his gaze became riveted upon the hull of a tall ship, apparently quite ready for launching, and from that moment he had eyes for nothing else. As he came abruptly to a halt, staring at the great bows that towered high above him, resplendent in all the glory of fresh paint and surmounted by a finely carved figure of an unknown animal with the head of a lion, the horns of a bull, the body of a fish, four legs shaped like those of an eagle, and the wings of a dragon, old Radlett nudged him in the ribs and, beaming happily upon him, remarked: “There a be, Garge; that’s the Nonsuch. What do ’e think of her?”

“Upon my word I hardly know,” answered George. “Let me look her over a bit, Mr Radlett, before you ask my opinion of her. Is she finished?”

“Finished?” reiterated the old man. “Iss, sure; quite finished, and all ready for launching. Why? Do ’e miss anything?”

“Why, yes,” said George; “I see neither fore nor after castles. How is that?”

“Swept ’em both away, lad,” was the answer. “What good be they? I allow that they be only so much useless top hamper, makin’ a ship crank and leewardly. ’Tis the fashion to build ’em, I know; but I’ve thought the matter out, and I say that they do more harm than they be worth. Therefore I’ve left ’em out in the Nonsuch, and you’ll see she’ll be all the better for it. But although she have neither fore nor after castles, she’ve a poop, and a raised deck for’ard where guns can be mounted and where, sheltered behind good stout bulwarks, the crew’ll be so safe as in any castle. Do ’e see any other differences in her?”

“Yes, I do,” answered George, as he walked round the hull and viewed it from different standpoints; “indeed I see nothing but differences. The under-water shape of her is different, her topsides have scarcely any tumble-home, and she has not nearly so much sheer as usual. Also I see that you have given her a very much deeper keel than usual. That ought to be of service in helping her to hang to windward.”

“So ’twill, boy; so ’twill,” agreed Radlett. “You’ll find that ’twill make a most amazin’ lot o’ difference when it comes to havin’ to claw off a lee shore, all the difference, perhaps, between losin’ the ship and savin’ of her. Then, about the tumble-home, I don’t see the use o’ it. True, it do help to keep the sea from comin’ over side in heavy weather, and keeps the decks dry. But then it do make the deck space terrible cramped up, so that wi’ guns, and boats, and spare spars and what not, the crew haven’t got room to move. But you’ll see presently, when you goes aboard, that this here Nonsuch have got decks so roomy as a ship o’ double her size. And I do hold that they almost vertical sides o’ hern’ll make mun ever so much finer a sea boat. And I’ve a-worked out the lines o’ mun upon a new principle that, unless I be greatly mistaken, will make this here Nonsuch such a fast sailor that nothin’ afloat’ll be able to escape from mun—or catch mun, if so be that her have got to run away from a very superior force. And I be havin’ the sails cut differently, too. I’ve thought it all out, and I’ve made up my mind that the way sails be cut up to now, they be very much too baggy, so that a ship can’t go to windward. But I be havin’ all the Nonsuch’s sails cut to set so flat as ever they can be made, and—well, I do expect ’twill make a lot of difference. And now, Garge, havin’ looked at her from outside, perhaps you’d like to go aboard and see what she do look like on deck and below.”

George having agreed that this was the case, the old man led his visitor up a ladder reaching from the ground to the entry port. After the spacious deck had been duly admired and commented upon the pair entered the cabins in the poop and below, where again everything proved so admirable that young Saint Leger found himself quite at a loss for words in which to adequately express his approval, to the great delight of the proud designer of the ship.

At length, after a thoroughly exhaustive inspection of the ship, both inside and out, during which Radlett drew attention to and expatiated upon the various new ideas embodied in the design, the curiously contrasted pair retired to the little room which the shipwright called his office, and there sat down for a chat.

“Well, Garge,” exclaimed the old man, as he seated himself comfortably in a great arm-chair, “now that you’ve had a good look at the Nonsuch, what do ’e think of her?”

“She is a splendid craft, and a perfect wonder, well worthy of her name,” pronounced George with enthusiasm. “I should not be surprised to learn that she inaugurates an entirely new system of shipbuilding. She would be the very ship, of all others, for such an adventure as mine; but I suppose you have built her with an especial view to some particular kind of service. Even if you have not, I very much doubt whether I could raise the money in a reasonable time to buy her. What price are you asking for her?”

“She is not for sale, boy,” answered the old man with an inscrutable smile. “I built her in order to put to the test certain theories o’ my own, and now, before ever she touches the water, I be sure, from the look of her, that my theories be right. So I be going to keep her and use her for my own purposes. And one o’ they purposes be to make money so fast as ever I can. I’ve got neither chick nor child to think about and take care of, so my only pleasure in life be to build good ships and make good money with ’em.