The Project Gutenberg eBook, Letters of Edward FitzGerald, by Edward

FitzGerald, Edited by William Aldis Wright

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Letters of Edward FitzGerald

in two volumes, Vol. 1

Author: Edward FitzGerald

Editor: William Aldis Wright

Release Date: January 27, 2007 [eBook #20452]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII)

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LETTERS OF EDWARD FITZGERALD***

Transcribed from the 1901 Macmillan and Co. edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

new york: the

macmillan and company

1901

All rights reserved

p. ivFirst Edition 1894. Reprinted 1901

In compliance with a very generally expressed wish that the Letters of Edward FitzGerald should be separated from his Literary Remains, they are now issued with some additions to their number which have not before appeared. It was no part of my plan to form a complete collection of his letters, but rather to let the story of his life be told in such of them as gave an indication of his character and pursuits. It would have been easy to increase the number considerably had I printed all that I possess, but it seemed better to create the desire for more than to incur the reproach of having given more than enough.

Since these volumes were completed a large number of letters, addressed by FitzGerald to his life-long friend Mrs. Kemble, have come into the possession of Messrs. Richard Bentley and Son, and p. viwill shortly make their appearance. By the desire of Mr. George Bentley I have undertaken to see them through the press.

William Aldis Wright.

Trinity College, Cambridge.

31 March, 1894.

In vol. ii. p. 181 the date 1875, which was conjectural, has been changed to 1878, in which year September 22—the day on which the letter was written—was a Sunday. There was a Musical Festival at Norwich in both years, and the same Oratorios were performed, and this led me to put the letter out of its place.

W. A. W.

After Mr. FitzGerald’s death in June 1883 a small tin box addressed to me was found by his executors, containing among other things corrected copies of his printed works, and the following letter, which must have been written shortly after my last visit to him at Easter that year:

Woodbridge: May 1/83.

My dear Wright,

I do not suppose it likely that any of my works should be reprinted after my Death. Possibly the three Plays from the Greek, and Calderon’s Mágico: which have a certain merit in the Form they are cast into, and also in the Versification.

However this may be, I venture to commit to you this Box containing Copies of all that I have corrected in the way that I would have them appear, if any of them ever should be resuscitated.

The C. Lamb papers are only materials for you, or any one else, to use at pleasure.

p. viiiThe Crabbe volume would, I think, serve for an almost sufficient Selection from him; and some such Selection will have to be made, I believe, if he is to be resuscitated. Two of the Poems—‘The Happy Day’ and ‘The Family of Love’—seem to me to have needed some such abridgement as the ‘Tales of the Hall,’ for which I have done little more than hastily to sketch the Plan. For all the other Poems, simple Extracts from them will suffice: with a short notice concerning their Dates of Composition, etc., at the Beginning.

My poor old Lowestoft Sea-slang may amuse yourself to look over perhaps.

And so, asking your pardon for inflicting this Box upon you I am ever sincerely yours

E. F. G.

In endeavouring to carry out these last wishes of my friend I thought that of the many who know him only as a translator some would be glad to have a picture of him as he appeared to the small circle of his intimate acquaintances. The mere narrative of the life of a man of leisure and literary tastes would have contained too few incidents to be of general interest, and it appeared to me best to let him be his own biographer, telling his own story and revealing his own character in his letters. Fortunately there are many of these, and I have endeavoured to give p. ixsuch a selection from them as would serve this purpose, adding a few words here and there to connect them and explain what was not sufficiently evident. As the letters begin from the time that he left College and continue with shorter or longer intervals till the day before his death, it was only necessary to introduce them by a short sketch of his early life in order to make the narrative complete.

FitzGerald’s letters, like his conversation, were perfectly unaffected and full of quiet humour. In his lonely life they were the chief means he had of talking with his friends, and they were always welcome. In reply to one of them Carlyle wrote: ‘Thanks for your friendly human letter; which gave us much entertainment in the reading (at breakfast time the other day), and is still pleasant to think of. One gets so many inhuman letters, ovine, bovine, porcine, etc., etc.: I wish you would write a little oftener; when the beneficent Daimon suggests, fail not to lend ear to him.’ Another, who has since followed him ‘from sunshine to the sunless land,’ and to whom he wrote of domestic affairs, said, ‘The striking feature in his correspondence with me is the exquisite tenderness of feeling which it exhibits in regard to all family matters; the letters might have been written by a mother or a sister.’ He said of himself that his friendships were more like loves, and p. xas he was constant in affectionate loyalty to others, he might also say with Brutus,

In all my life

I found no man but he was true to me.

The Poet-Laureate, on hearing of his death, wrote to the late Sir Frederic Pollock: ‘I had no truer friend: he was one of the kindliest of men, and I have never known one of so fine and delicate a wit. I had written a poem to him the last week, a dedication, which he will never see.’

When Thackeray, not long before he died, was asked by his daughter which of his old friends he had loved most, he replied, ‘Why, dear old Fitz, to be sure; and Brookfield.’

And Carlyle, quick of eye to discern the faults and weaknesses of others, had nothing but kindliness, with perhaps a touch of condescension, ‘for the peaceable, affectionate, and ultra-modest man, and his innocent far niente life.’

It was something to have been intimate with three such friends, and one can only regret that more of his letters addressed to them have not been preserved. Of those written to the earliest and dearest friend of all, James Spedding, not one is left.

One of his few surviving contemporaries, speaking from a lifelong experience, described him with perfect p. xitruth as an eccentric man of genius, who took more pains to avoid fame than others do to seek it.

His love of music was one of his earliest passions, and remained with him to the last. I cannot refrain from quoting some recollections of the late Archdeacon Groome, a friend of his College days, and so near a neighbour in later life that few letters passed between them. ‘He was a true musician; not that he was a great performer on any instrument, but that he so truly appreciated all that was good and beautiful in music. He was a good performer on the piano, and could get such full harmonies out of the organ that stood in one corner of his entrance room at Little Grange as did good to the listener. Sometimes it would be a bit from one of Mozart’s Masses, or from one of the finales of some one of his or Beethoven’s Operas. And then at times he would fill up the harmonies with his voice, true and resonant almost to the last. I have heard him say, “Did you never observe how an Italian organ-grinder will sometimes put in a few notes of his own in such perfect keeping with the air which he was grinding?” He was not a great, but he was a good composer. Some of his songs have been printed, and many still remain in manuscript. Then what pleasant talk I have had with him about the singers of our early years; never forgetting to speak of Mrs. Frere of p. xiiDowning, as the most perfect private singer we had ever heard. And so indeed she was. Who that had ever heard her sing Handel’s songs can ever forget the purity of her phrasing and the pathos of her voice? She had no particle of vanity in her, and yet she would say, “Of course, I can sing Handel. I was a pupil of John Sale, and he was a pupil of Handel.” To her old age she still retained the charm of musical expression, though her voice was but a thread. And so we spoke of her; two old men with all the enthusiastic admiration of fifty years ago. Pleasant was it also to hear him speak of the public singers of those early days. Braham, so great, spite of his vulgarity; Miss Stephens, so sweet to listen to, though she had no voice of power; and poor Vaughan, who had so feeble a voice, and yet was always called “such a chaste singer.” How he would roar with laughter, when I would imitate Vaughan singing

His hiddeus (sic) love provokes my rage,

Weak as I am, I must engage,

from Acis and Galatea. Then too his reminiscences of the said Acis and Galatea as given at the Concerts for Ancient Music. “I can see them now, the dear old creeters with the gold eye-glasses and their turbans, noddling their heads as they sang

O the pleasures of the plains!”

p. xiii‘These old creeters being, as he said, the sopranos who had sung first as girls, when George the Third was king.

‘He was a great lover of our old English composers, specially of Shield. Handel, he said, has a scroll in his marble hand in the Abbey on which are written the first bars of

I know that my Redeemer liveth;

and Shield should hold a like scroll, only on it should be written the first bars of

A flaxen-headed ploughboy.

‘He was fond of telling a story of Handel, which I, at least, have never seen in print. When Handel was blind he composed his “Samson,” in which there is that most touching of all songs, specially to any one whose powers of sight are waning—“Total Eclipse.” Mr. Beard was the great tenor singer of the day, who was to sing this song. Handel sent for him, “Mr. Beard,” he said, “I cannot sing it as it should be sung, but I can tell you how it ought to be sung.” And then he sang it, with what strange pathos need not be told. Beard stood listening, and when it was finished said, with tears in his eyes, “But Mr. Handel, I can never sing it like that.” And so he would tell the story with tears in his voice, such as p. xivthose best remember, who ever heard him read some piece of his dear old Crabbe, and break down in the reading.’

With this I will conclude, and I have only now to express my sincere thanks to all who have entrusted me with letters addressed to themselves or to those whom they represent. It has been my endeavour to justify their confidence by discretion. To Messrs. Richard Bentley and Son I am indebted for permission to reprint Virgil’s Garden from the Temple Bar Magazine. [0a]

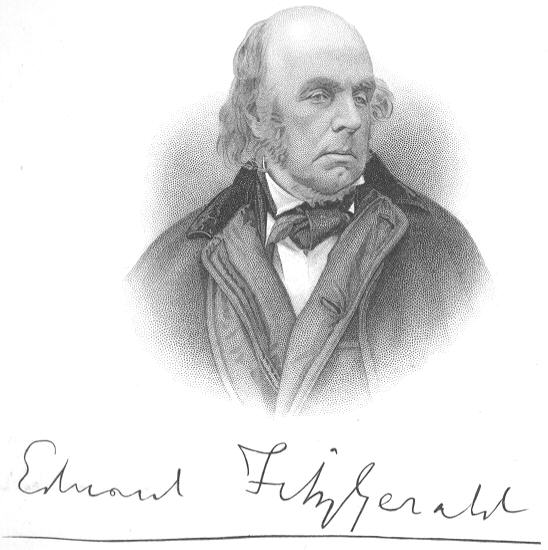

The portrait is from a photograph by Cade and White of Ipswich taken in 1873.

William Aldis Wright.

Trinity College, Cambridge.

20 May, 1889.

Edward FitzGerald was born at Bredfield House in Suffolk, an old Jacobean mansion about two miles from Woodbridge, on the 31st of March, 1809. He was the third son of John Purcell, who married his cousin Mary Frances FitzGerald, and upon the death of her father in 1818 took the name and arms of FitzGerald. In 1816 Mr. Purcell went to France, and for a time settled with his family at St. Germains. FitzGerald in later life would often speak of the royal hunting parties which he remembered seeing in the forest. They afterwards removed to Paris, occupying the house in which Robespierre had once lived, and here FitzGerald had for his drillmaster one of Napoleon’s Old Guard. Even at this early period the vivacious humour which afterwards characterized him appears to have shewn itself, for his father writing to some friends in England speaks of little p. 2Edward keeping the whole family in good spirits by his unfailing fun and droll speeches. The dramatic circumstances of the assassination of M. Fualdès, a magistrate at Rodez, in 1817, and the remarkable trial which followed, fastened themselves on FitzGerald’s memory, and he was familiar with all the details which he had heard spoken of when quite a child in Paris. In 1821 he was sent to King Edward the Sixth’s School at Bury St. Edmunds, where his two elder brothers were already under the charge of Dr. Malkin, who, like himself in after life, was a great admirer of Crabbe. Among his schoolfellows were James Spedding and his elder brother, W. B. Donne, J. M. Kemble, and William Airy the brother of Sir George Airy, formerly Astronomer-Royal. I have often heard him say that the best piece of declamation he had ever listened to was Kemble’s recitation of Hotspur’s speech, beginning ‘My liege, I did deny no prisoners,’ on a prize day at Bury. When he left for Cambridge in 1826 the Speddings were at the head of the School. He was entered at Trinity on 6th February 1826 under Mr. (afterwards Dean) Peacock and went into residence in due course in the following October, living in lodgings at Mrs. Perry’s (now Oakley’s), No. 19 King’s Parade. James Spedding did not come up till the year following, and his greatest friends in later life, John Allen, afterwards Archdeacon of Salop, W. M. Thackeray, and W. H. Thompson, afterwards Master of Trinity, were his juniors at the University p. 3by two years. The three Tennysons were also his contemporaries, but it does not appear that he knew them till after he had left Cambridge. Indeed, in a letter to Mrs. Richmond Ritchie (Miss Thackeray), written in 1882, he says of the Laureate, ‘I can tell you nothing of his College days; for I did not know him till they were over, though I had seen him two or three times before. I remember him well—a sort of Hyperion.’

FitzGerald was unambitious of University distinctions and was not in the technical sense a reading man, but he passed through his course in a leisurely manner, amusing himself with music and drawing and poetry, and modestly went out in the Poll in January 1830, after a period of suspense during which he was apprehensive of not passing at all. Immediately after taking his degree he went to stay with his brother-in-law, Mr. Kerrich, at Geldestone Hall, near Beccles, where he afterwards spent much of his time. While there, and still undecided as to his future movements, he writes to his friend John Allen that his father had to some extent decided for him by reducing his allowance, a measure which would compel him to go and live in France. It was apparently not in consequence of this, for the difficulty with his father was satisfactorily arranged, that he went in the spring of 1830 to Paris, where his aunt, Miss Purcell, was living. Thackeray joined him for a short time in April, but left suddenly, and was the bearer of a hurried letter written by FitzGerald at the Palais p. 4Royal to the friend who was at this time his chief correspondent.

‘If you see Roe (the Engraver, not the Haberdasher) give him my remembrance and tell him I often wish for him in the Louvre: as I do for you, my dear Allen: for I think you would like it very much. There are delightful portraits (which you love most), and statues so beautiful that you would for ever prefer statues to pictures. There are as fine pictures in England: but not one statue so fine as any here. There is a lovely and very modest Venus: and the Gladiator: and a very majestic Demosthenes, sitting in a chair, with a roll of writing in his hands, and seemingly meditating before rising to speak. It is quite awful.’

FitzGerald remained in France till about the end of May, and before leaving wrote again to Allen, not perhaps altogether seriously, yet with more truth than he imagined, of his future mode of life.

‘I start for England in a week, as I purpose now: I shall go by Havre de Grace and Southampton, and stay for a month or two perhaps at Dartmouth, a place on the Devonshire coast. Tell Thackeray that he is never to invite me to his house, as I intend never to go: not that I would not go out there rather than any place perhaps, but I cannot stand seeing new faces in the polite circles. You must know I am going to become a great bear: and have got all sorts of Utopian ideas into my head about society: these may all be very absurd, but I try the experiment on p. 5myself, so I can do no great hurt. Where I shall go in the summer I know not.’

In the end he made Southampton his headquarters and spent several weeks there, going on short excursions to visit some college acquaintances. In November he was at Naseby, where his father had a considerable estate, including the famous battlefield, of which we shall hear more in his later correspondence. ‘This place is solitary enough,’ he writes to John Allen, ‘but I am well off in a nice farm-house. I wish you could come and see the primitive inhabitants, and the fine field of Naseby. There are grand views on every side: and all is interesting. . . . Do you know, Allen, that this is a very curious place with odd fossils: and mixed with bones and bullets of the fight at Naseby; and the identical spot where King Charles stood to see the battle. . . . I do wish you and Sansum were here to see the curiosities. Can’t you come? I am quite the King here I promise you. . . . I am going to-day to dine with the Carpenter, a Mr. Ringrose, and to hear his daughter play on the pianoforte. Fact.

‘My blue surtout daily does wonders. At Church its effect is truly delightful.’

It was at Naseby, in the spring of the following year (1831), that he made his earliest attempt in verse, the earliest at any rate which has yet been discovered. Charles Lamb, writing to Moxon in August, tells him, ‘The Athenæum has been hoaxed p. 6with some exquisite poetry, that was, two or three months ago, in Hone’s Book. . . . The poem I mean is in Hone’s Book as far back as April. I do not know who wrote it; but ’tis a poem I envy—that and Montgomery’s “Last Man”: I envy the writers, because I feel I could have done something like them.’ It first appeared in Hone’s Year Book for April 30, 1831, with the title ‘The Meadows in Spring,’ and the following letter to the Editor. ‘These verses are in the old style; rather homely in expression; but I honestly profess to stick more to the simplicity of the old poets than the moderns, and to love the philosophical good humor of our old writers more than the sickly melancholy of the Byronian wits. If my verses be not good, they are good humored, and that is something.’ With a few verbal changes they were sent to the Athenæum, and appeared in that paper on July 9, 1831, accompanied by a note of the Editor’s, from which it is evident that he supposed them to have been written by Lamb.

To the Editor of the Athenæum.

Sir,

These verses are something in the old style, but not the worse for that: not that I mean to call them good: but I am sure they would not have been better, if dressed up in the newest Montgomery fashion, for which I cannot say I have much love. If they are fitted for your paper, you are welcome p. 7to them. I send them to you, because I find only in your paper a love of our old literature, which is almost monstrous in the eyes of modern ladies and gentlemen. My verses are certainly not in the present fashion; but, I must own, though there may not be the same merit in the thoughts, I think the style much better: and this with no credit to myself, but to the merry old writers of more manly times.

Your humble servant,

Epsilon.

’Tis a dull sight

To see the year dying,

When winter winds

Set the yellow wood sighing:

Sighing, oh! sighing.When such a time cometh,

I do retire

Into an old room

Beside a bright fire:

Oh, pile a bright fire!And there I sit

Reading old things,

Of knights and lorn damsels,

While the wind sings—

Oh, drearily sings!I never look out

Nor attend to the blast;

For all to be seen

Is the leaves falling fast:

Falling, falling!p. 8But close at the hearth,

Like a cricket, sit I,

Reading of summer

And chivalry—

Gallant chivalry!Then with an old friend

I talk of our youth—

How ’twas gladsome, but often

Foolish, forsooth:

But gladsome, gladsome!Or to get merry

We sing some old rhyme,

That made the wood ring again

In summer time—

Sweet summer time!Then go we to smoking,

Silent and snug:

Nought passes between us,

Save a brown jug—

Sometimes!And sometimes a tear

Will rise in each eye,

Seeing the two old friends

So merrily—

So merrily!And ere to bed

Go we, go we,

Down on the ashes

We kneel on the knee,

Praying together!Thus, then, live I,

Till, ’mid all the gloom,

By heaven! the bold sun

Is with me in the room.

Shining, shining!p. 9Then the clouds part,

Swallows soaring between;

The spring is alive,

And the meadows are green!I jump up, like mad,

Break the old pipe in twain,

And away to the meadows,

The meadows again!

I had very little hesitation, from internal evidence alone, in identifying these verses with those which FitzGerald had written, as he said, when a lad, or little more than a lad, and sent to the Athenæum, but all question has been set at rest by the discovery of a copy in a common-place book belonging to the late Archdeacon Allen, with the heading ‘E. F. G.,’ and the date ‘Naseby, Spring, 1831.’ This copy differs slightly from those in the Year Book and in the Athenæum, and in place of the tenth stanza it has,

So winter passeth

Like a long sleep

From falling autumn

To primrose-peep.

But although at this time he appears to have written nothing more himself he was not unmindful of what was done by others, for in May 1831 he writes to Allen, ‘I have bought A. Tennyson’s poems. How good Mariana is!’ And again a year later, after a night-ride on the coach to London, ‘I forgot to tell you that when I came up in the mail, and fell a dozing in the morning, p. 10the sights of the pages in crimson and the funerals which the Lady of Shalott saw and wove, floated before me: really, the poem has taken lodging in my poor head.’

The correspondence will now for the most part tell its own story, and with it all that is to be told of FitzGerald’s life.

In October and November 1831 he was for three weeks in town with Thackeray, and in the following summer was thinking of joining him at Havre when he wrote to his friend Allen.

[Southampton]

July 31, Tuesday [1832.]

My dear Allen,

. . . And now I will tell you of a pilgrimage I made that put me in mind of you much. I went to Salisbury to see the Cathedral, but more to walk to Bemerton, George Herbert’s village. It is about a mile and half from Salisbury alongside a pleasant stream with old-fashioned watermills beside: through fields very fertile. When I got to Bemerton I scarcely knew what to do with myself. It is a very pretty village with the Church and Parsonage much as Herbert must have left it. But there is no memorial of him either in or outside the walls of the church: though there have been Bishops and Deans and I know not what all so close at hand at Salisbury. This is a great shame indeed. I would gladly put up a plain stone if I could get the Rector’s leave. I was very p. 11sorry to see no tablet of any kind. The people in the Cottages had heard of a very pious man named Herbert, and had read his books—but they don’t know where he lies. I have drawn the church and village: the little woodcut of it in Walton’s Lives is very like. I thought I must have passed along the spot in the road where he assisted the man with the fallen horse: and to shew the benefit of good examples, I was serviceable that very evening in the town to some people coming in a cart: for the driver was drunk and driving furiously home from the races, and I believe would have fallen out, but that some folks, amongst whom I was one, stopped the cart. This long history is now at an end. I wanted John Allen much to be with me. I noticed the little window into which Herbert’s friend looked, and saw him kneeling so long before the altar, when he was first ordained.

* * * * *

In the summer and autumn of this year FitzGerald spent some weeks at Tenby and was a good deal with Allen to whom he wrote on his return to London.

London, Nov. 21, 1832.

My dear Allen,

I suppose it must seem strange to you that I should like writing letters: and indeed I don’t know that I do like it in general. However, here I see no companions, so I am pleased to talk to my old friend John Allen: which indeed keeps alive my p. 12humanity very much. . . . I have been about to divers Bookshops and have bought several books—a Bacon’s Essays, Evelyn’s Sylva, Browne’s Religio Medici, Hazlitt’s Poets, etc. The latter I bought to add to my Paradise, which however has stood still of late. I mean to write out Carew’s verses in this letter for you, and your Paradise. As to the Religio, I have read it again: and keep my opinion of it: except admiring the eloquence, and beauty of the notions, more. But the arguments are not more convincing. Nevertheless, it is a very fine piece of English: which is, I believe, all that you contend for. Hazlitt’s Poets is the best selection I have ever seen. I have read some Chaucer too, which I like. In short I have been reading a good deal since I have been here: but not much in the way of knowledge.

. . . As I lay in bed this morning, half dozing, I walked in imagination all the way from Tenby to Freestone by the road I know so well: by the water-mill, by Gumfreston, Ivy tower, and through the gates, and the long road that leads to Carew.

Now for the poet Carew:

1.

Ask me no more where Jove bestows,

When June is past, the fading rose:

For in your beauty’s orient deep,

The flowers, as in their causes, sleep.2.

Ask me no more whither do stray

The golden atoms of the day:

p. 13For in pure love did Heav’n prepare

Those powders to enrich your hair.3.

Ask me no more whither doth haste

The nightingale when June is past:

For in your sweet dividing throat

She winters, and keeps warm her note.4.

Ask me no more where those stars light

That downward fall at dead of night:

For in your eyes they sit, and there

Fixed become, as in their sphere.5.

Ask me no more if east or west

The phœnix builds her spicy nest:

For unto you at last she flies,

And in your fragrant bosom dies.

These lines are exaggerated, as all in Charles’s time, but very beautiful. . . .

Yours most affectionately, E.

London, Nov. [27, 1832.]

My dear Allen,

The first thing I do in answering your letter is to tell you that I am angry at your saying that your conscience pricks you for not having written to me before. I am of that superior race of men, that are quite content to hear themselves talk, and read their own writing. But, in seriousness, I have such love of you, and of myself, that once every week, at least, I feel spurred on by a sort of gathering up of feelings p. 14to vent myself in a letter upon you: but if once I hear you say that it makes your conscience thus uneasy till you answer, I shall give it up. Upon my word I tell you, that I do not in the least require it. You, who do not love writing, cannot think that any one else does: but I am sorry to say that I have a very young-lady-like partiality to writing to those that I love. . . . I have been reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets: and I believe I am unprejudiced when I say, I had but half an idea of him, Demigod as he seemed before, till I read them carefully. How can Hazlitt call Warton’s the finest sonnets? There is the air of pedantry and labour in his. But Shakespeare’s are perfectly simple, and have the very essence of tenderness that is only to be found in the best parts of his Romeo and Juliet besides. I have truly been lapped in these Sonnets for some time: they seem all stuck about my heart, like the ballads that used to be on the walls of London. I have put a great many into my Paradise, giving each a fair white sheet for himself: there being nothing worthy to be in the same page. I could talk for an hour about them: but it is not fit in a letter. . . .

I shall tell you of myself, that I have been better since I wrote to you. Mazzinghi [14] tells me that November weather breeds Blue Devils—so that there is a French proverb, ‘In October, de Englishman p. 15shoot de pheasant: in November he shoot himself.’ This I suppose is the case with me: so away with November, as soon as may be. ‘Canst thou my Clora’ is being put in proper musical trim: and I will write it out for you when all is right. I am sorry you are getting so musical: and if I take your advice about so big a thing as Christianity, take you mine about music. I am sure that this pleasure of music grows so on people, that many of the hours that you would have devoted to Jeremy Taylor, etc. will be melted down into tunes, and the idle train of thought that music puts us into. I fancy I have discovered the true philosophy of this: but I think you must have heard me enlarge. Therefore ‘satis.’

I have gabbled on so long that there is scarce room for my quotation. But it shall come though in a shapeless manner, for the sake of room. Have you got in your Christian Poet, a poem by Sir H. Wotton—‘How happy is he born or taught, that serveth not another’s will’? It is very beautiful, and fit for a Paradise of any kind. Here are some lines from old Lily, which your ear will put in the proper metre. It gives a fine description of a fellow walking in Spring, and looking here and there, and pricking up his ears, as different birds sing. ‘What bird so sings, but doth so wail? Oh! ’tis the ravished nightingale: “Jug, jug, jug, jug, terue,” she cries, and still her woes at midnight rise. Brave prick-song! who is’t now we hear? It is the lark so shrill and clear: against heaven’s gate he claps his wings, the morn not waking p. 16till he sings. Hark, too, with what a pretty note poor Robin Redbreast tunes his throat: Hark how the jolly cuckoos sing “Cuckoo” to welcome in the Spring: “Cuckoo” to welcome in the Spring.’ This is very English, and pleasant, I think: and so I hope you will. I could have sent you many a more sentimental thing, but nothing better. I admit nothing into my Paradise, but such as breathe content, and virtue: I count ‘Back and syde’ to breathe both of these, with a little good drink over.

Wednesday [28 Nov. 1832].

P.S. I sealed up my letter yesterday, forgetting to finish. I write thus soon ‘becase I gets a frank.’ You shall benefit by another bit of poetry. I do not admit it into my Paradise, being too gloomy: but it will please both of us. It is the prototype of the Pensieroso.

Hence all you vain delights!

As short as are the nights

Wherein you spend your folly!

There’s nought in this life sweet,

If man were wise to see ’t,

But only melancholy;

Oh sweetest melancholy!

Welcome folded arms, and fixed eyes,

A sigh, that piercing mortifies,

A look that’s fastened to the ground,

A tongue chain’d up without a sound!Fountain heads, and pathless gloves,

Places which pale passion loves!

p. 17Moonlight walks, when all the fowls

Are warmly hous’d, save bats and owls!

A midnight dell, a passing groan!

These are the sounds we feed upon;

Then stretch our bones in a still gloomy valley;

Nothing’s so dainty sweet as [lovely] melancholy.

(From the Nice Valour, or the Passionate Madman, by Fletcher.)

I think these lines are quite of the finest order, and have a more headlong melancholy than Milton’s, which are distinctly copied from these, as you must confess. And now this is a very long letter, and the best thing you can do when you get to the end, is to Da Capo, and read what I ordered you about answering. My dear fellow, it is a great pleasure to me to write to you; and to write out these dear poems. . . . Believe me that I am your very loving friend,

E. F. G.

[Dec. 7, 1832.]

My dear Allen,

You can hardly have got through my last letter by this time. I hope you liked the verses I sent you. The news of this week is that Thackeray has come to London, but is going to leave it again for Devonshire directly. He came very opportunely to divert my Blue Devils: notwithstanding, we do not see very much of each other: and he has now so many friends (especially the Bullers) that he has no such wish for my society. He is as full of good humour and kindness as ever. The next news is that a new volume of Tennyson is out: containing nothing more p. 18than you have in MS. except one or two things not worth having. . . .

When you write back (of which there is no hurry) send me an account that you and your Brother were once telling me at Bosherston, of three Generals condemned to die after the siege of Pembroke in Cromwell’s time: and of the lot being brought by a little child. Give me their names, etc. (if you can) pretty circumstantially: or else, tell me where I can find some notice of it. . . .

I have been poring over Wordsworth lately: which has had much effect in bettering my Blue Devils: for his philosophy does not abjure melancholy, but puts a pleasant countenance upon it, and connects it with humanity. It is very well, if the sensibility that makes us fearful of ourselves is diverted to become a cause of sympathy and interest with Nature and mankind: and this I think Wordsworth tends to do. I think I told you of Shakespeare’s sonnets before: I cannot tell you what sweetness I find in them.

So by Shakespeare’s Sonnets roasted, and Wordsworth’s poems basted,

My heart will be well toasted, and excellently tasted.

This beautiful couplet must delight you, I think. I will also give you the two last verses about Clora: though it is more complete and better without them: strange to say. You must have the goodness to repeat those you know over first, and then fall upon these: for there is a sort of reasoning in them, which p. 19requires proper order, as much as a proposition of Euclid. The first of them is not to my liking, but it is too much trouble about a little thing to work it into a better. You have the two first stanzas [19]—“ergo”

3.

Nothing can utterly die:

Music aloft upspringing

Turns to pure atoms of sky

Each golden note of thy singing:

And that to which morning did listen

At eve in a rainbow may glisten.4.

Beauty, when laid in the grave,

Feedeth the lily beside her:

Therefore the soul cannot have

Station or honour denied her:

She will not better her essence,

But wear a crown in God’s presence.Q.E.D.

p. 20And I think there is quite enough of Clora and her music. I am hunting about the town for an ancient drinking cup, which I may use when I am in my house, in quality of housekeeper. Have the goodness to make my remembrances to all at that most pleasant house Freestone: I am quite serious in telling you how it is by far the pleasantest family I ever was among.

My sister is far better. We walk very much and see such sights as the town affords. To-day I have bought a little terrier to keep me company. You will think this is from my reading of Wordsworth: but if that were my cue, I should go no further than keeping a primrose in a pot for society. Farewell, dear Allen. I am astonished to find myself writing a very long letter once a week to you: but it is next to talking to you: and after having seen you so much this summer, I cannot break off suddenly.

I am your most affectionate friend,

E. F. G.

Have you got this beginning to your MS. of the Dream of Fair Women? It is very splendid.

1.

As when a man that sails in a balloon

Down looking sees the solid shining ground

Stream from beneath him in the broad blue noon,—

Tilth, hamlet, mead and mound:2.

And takes his flags, and waves them to the mob

That shout below, all faces turn’d to where

Glows rubylike the far-up crimson globe

Filled with a finer air:So, lifted high, the Poet at his will

Lets the great world flit from him, seeing all,

Higher through secret splendours mounting still

Self-poised, nor fears to fall,4. Hearing apart the echoes of his fame—

This is in his best style: no fretful epithet, nor a word too much.

[Castle

Irwell]

Manchester, February 24,

1833.

Dear Allen,

. . . I am fearful to boast, lest I should lose what I boast of: but I think I have achieved a victory over my evil spirits here: for they have full opportunity to come, and I often observe their approaches, but hitherto I have managed to keep them off. Lord Bacon’s Essay on Friendship is wonderful for its truth: and I often feel its truth. He says that with a Friend ‘a man tosseth his thoughts,’ an admirable saying, which one can understand, but not express otherwise. But I feel that, being alone, one’s thoughts and feelings, from want of communication, become heaped up and clotted together, as it were: and so lie like undigested food heavy upon the mind: but with a friend one tosseth them about, so that the air gets between them, and keeps them fresh and sweet. I know not from what metaphor Bacon took his ‘tosseth,’ but it seems to me as if it was from the way p. 22haymakers toss hay, so that it does not press into a heavy lump, but is tossed about in the air, and separated, and thus kept sweet. . . .

Your most affectionate friend,

E. FitzGerald.

To W. B. Donne. [22]

Geldestone, Sept. 27, [1833].

Dear Donne,

. . . As to my history since I have seen you, there is little to tell. Divinity is not outraged by your not addressing me as a Reverend—I not being one. I am a very lazy fellow, who do nothing: and this I have been doing in different places ever since I saw you last. I have not been well for the last week: for I am at present rather liable to be overset by any weariness (and where can any be found that can match the effect of two Oratorios?), since for the last three months I have lived on vegetables—that is, I have given up meat. When I was talking of this to Vipan, he told me that you had once tried it, and given it up. I shall hear your account of its effect p. 23on you. The truth is, that mine is the wrong time of life to begin a change of that kind: it is either too early, or too late. But I have no doubt at all of the advantage of giving up meat: I find already much good from it, in lightness and airiness of head, whereas I was always before clouded and more or less morbid after meat. The loss of strength is to be expected: I shall keep on and see if that also will turn, and change into strength. I have almost Utopian notions about vegetable diet, begging pardon for making use of such a vile, Cheltenhamic, phrase. Why do you not bring up your children to it? To be sure, the chances are, that, after guarding their vegetable morals for years, they would be seduced by some roast partridge with bread sauce, and become ungodly. This actually happened to the son of a Dr. Newton who wrote a book [23] about it and bred up his children to it—but all such things I will tell you when I meet you. Gods! it is a pleasant notion that one is about to meet an old acquaintance in a day or two.

Believe me then your most sincere friend,

E. FitzGerald.

Pipes—are their names ever heard with you? I have given them up, except at Cambridge. But the word has something sweet in it—Do you ever smoke?

p. 247 Southampton Row, Bloomsbury,

[Oct. 25, 1833.]

Dear Donne,

. . . As to myself, and my diet, about which you give such excellent advice: I am still determined to give the diet I have proposed a good trial: a year’s trial. I agree with you about vegetables, and soups: but my diet is chiefly bread: which is only a little less nourishing than flesh: and, being compact, and baked, and dry, has none of the washy, diluent effects of green vegetables. I scarcely ever touch the latter: but only pears, apples, etc. I have found no benefit yet; except, as I think, in more lightness of spirits: which is a great good. But I shall see in time.

I am living in London in the quarter of the town which I have noticed above: in a very happy bachelor-like way. Would you would come up here for a few days. I can give you bed, board, etc. Do have some business in town, please. Spedding is here: taking lessons of drawing, before he goes for good into Cumberland: whither, for my sake and that of all his friends, I wish he never would go: for there are few such men, as far [as] I know. He and I have been theatricalizing lately. We saw an awful Hamlet the other night—a Mr. Serle—and a very good Wolsey, in Macready: and a very bad Queen Catherine, in Mrs. Sloman, whom you must remember. I am going to-night to see Macready in p. 25Macbeth: I have seen him before in it: and I go for the sake of his two last acts, which are amazingly fine, I think. . . . I am close to the British Museum, in which I take great pleasure in reading in my rambling way. I hear of Kemble lately that he has been making some discoveries in Anglo-Saxon MSS. at Cambridge that, they say, are important to the interests of the church: and there is talk of publishing them, I believe. He is a strange fellow for that fiery industry of his: and, I am sure, deserves some steady recompense.

Tennyson has been in town for some time: he has been making fresh poems, which are finer, they say, than any he has done. But I believe he is chiefly meditating on the purging and subliming of what he has already done: and repents that he has published at all yet. It is fine to see how in each succeeding poem the smaller ornaments and fancies drop away, and leave the grand ideas single. . . .

I have lately bought a little pamphlet which is very difficult to be got, called The Songs of Innocence, written and adorned with drawings by W. Blake (if you know his name) who was quite mad, but of a madness that was really the elements of great genius ill-sorted: in fact, a genius with a screw loose, as we used to say. I shall shew you this book when I see you: to me there is particular interest in this man’s writing and drawing, from the strangeness of the constitution of his mind. He was a man that used to see visions: and make drawings and paintings p. 26of Alexander the Great, Cæsar, etc., who, he declared, stood before him while he drew. . .

Your very affectionate friend,

E. FitzGerald.

7 Southampton

Row,

Nov. 19, 1833.

Dear Donne,

Your book I got, and read through all that seemed to concern me the first day. I have doubted whether it would be most considerate to return you thanks for it, making you pay for a letter: or to leave you thankless, with a shilling more in your pocket. You see I have taken the latter [? former], and God forgive me for it. The book is a good one, I think, as any book is, that notes down facts alone, especially about health. I wish we had diaries of the lives of half the unknown men that have lived. Like all other men who have got a theory into their heads, I can only see things in the light of that theory; and whatever is brought to me to convince me to the contrary is only wrought and tortured to my view of the question. This lasts till a reaction is brought about by some of the usual means: as time, and love of novelty, etc. I am still very obstinate and persist in my practices. I do not think Stark is an instance of vegetable diet: consider how many things he tried grossly animal: lard, and butter, and fat: besides thwarting Nature in every way by eating when he wanted not to eat, and the contrary. Besides the p. 27editor says in the preface that he thinks his death was brought about as much by vexation as by the course of his diet: but I suppose the truth is that vexation could not have had so strong hold except upon a weakened body. However, altogether I do not at all admit Stark to be any instance: to be set up like a scarecrow to frighten us from the corn, etc. Last night I went to hear a man lecture at Owen of Lanark’s establishment (where I had never been before), and the subject happened to be about Vegetable Diet: but it was only the termination of a former lecture, so that I suppose all the good arguments (if there were any) were gone before. Do you know anything of a book by a Doctor Lamb upon this subject? I do not feel it to be disgusting to talk of myself upon this subject, because I think there is great interest in the subject itself. So I shall say that I am just now very well: in fine spirits. I have only eaten meat once for many weeks: and that was at a party where I did not like to be singled out. Neither have I tasted wine, except two or three times. If I fail at last I shall think it a very great bore: but assuredly the first cut of a leg of mutton will be some consolation for my wounded judgement: that first cut is a fine thing. So much for this. . . . Have you heard that Arthur Malkin is to be married? to a Miss Carr, with what Addison might call a pleasing fortune: or perhaps Nicholas Rowe. ‘Sweet, pleasing friendship, etc. etc.’ Mrs. Malkin is in high spirits about it, I hear: and I am very glad indeed. God send that p. 28you have not heard this before: for a man likes to be the first teller of a pretty piece of news. Spedding and I went to see Macready in Hamlet the other night: with which he was pretty well content, but not wholly. For my part, I have given up deciding on how Hamlet should be played: or rather have decided it shouldn’t be played at all. I take pleasure in reading things I don’t wholly understand; just as the old women like sermons: I think it is of a piece with an admiration of all Nature around us. I think there is a greater charm in the half meanings and glimpses of meaning that come in through Blake’s wilder visions: though his difficulties arose from a very different source from Shakespeare’s. But somewhat too much of this. I suspect I have found out this as an useful solution, when I am asked the meaning of any thing that I am admiring, and don’t know it.

Believe me, dear Donne, to be ever your affectionate friend,

E. FitzGerald.

* * * * *

FitzGerald spent the May term of 1834 at Cambridge ‘rejoicing in the sunshine of James Spedding’s presence.’

To John Allen.

Wherstead

Lodge, Ipswich. [28]

June 31 (so) 1834.

Dear My Johnny,

I have been reading the Spectator since I have been here: and I like it very much. Don’t you think p. 29it would make a nice book to publish all the papers about Sir Roger de Coverley alone, with illustrations by Thackeray? It is a thing that is wanted: to bring that standard of the old English Gentleman forward out of the mass of little topics, and fashions, that occupy the greater part of the Spectator. Thackeray has illustrated my Undine in about fourteen little coloured drawings—very nicely. . . .

I am here in the country in brave health: rising at six withal: and pruning of rose trees in the garden. Why don’t you get up early? in the summer at least. The next time we meet in town I mean to get an artist to make me your portrait: for I often wish for it. It must be looking at me. Now write very soon: else I shall be gone: and know that I am your very true friend,

E. F. G.

Geldestone Hall, Sept. 9, [1834].

Dear Allen,

I have really nothing to say, and I am ashamed to be sending this third letter all the way from here to Pembrokeshire for no earthly purpose: but I have just received yours: and you will know how very welcome all your letters are to me when you see how the perusal of this one has excited me to such an instant reply. It has indeed been a long time coming: but it is all the more delicious. Perhaps you can’t imagine how wistfully I have looked for it: how, p. 30after a walk, my eyes have turned to the table, on coming into the room, to see it. Sometimes I have been tempted to be angry with you: but then I thought that I was sure you would come a hundred miles to serve me, though you were too lazy to sit down to a letter. I suppose that people who are engaged in serious ways of life, and are of well filled minds, don’t think much about the interchange of letters with any anxiety: but I am an idle fellow, of a very ladylike turn of sentiment: and my friendships are more like loves, I think. Your letter found me reading the Merry Wives of Windsor too: I had been laughing aloud to myself: think of what another coat of happiness came over my former good mood. You are a dear good fellow, and I love you with all my heart and soul. The truth is I was anxious about this letter, as I really didn’t know whether you were married or not—or ill—I fancied you might be anything, or anywhere. . . .

As to reading I have not done much. I am going through the Spectator: which people nowadays think a poor book: but I honour it much. What a noble kind of Journal it was! There is certaintly a good deal of what may be called ‘pill,’ but there is a great deal of wisdom, I believe, only it is couched so simply that people can’t believe it to be real absolute wisdom. The little book you speak of I will order and buy. I heard from Thackeray, who is just upon the point of going to France; indeed he may be there by this time. I shall miss him much. . . .

p. 31Farewell my dearest fellow: you have made me very happy to hear from you: and to know that all is so well with you. Believe me to be your ever affectionate friend,

E. FitzGerald.

To W. B. Donne.

[London,

17 Gloucester Street, Queen Square].

1834.

Dear Donne,

. . . I have been buying two Shakespeares, a second and third Folio—the second Folio pleases me much: and I can read him with a greater zest now. One had need of a big book to remember him by: for he is lost to the theatre: I saw Mr. Vandenhoff play Macbeth in a sad way a few nights ago: and such a set of dirty ragamuffins as the rest were could not disgrace any country barn. Manfred I have missed by some chance: and I believe ‘it was all for the best’ as pious people say. The Theatre is bare beyond anything I ever saw: and one begins to hope that it has touched the bottom of its badness, and will rise again. I was looking the other day at Sir W. Davenant’s alteration of Macbeth: who dies, saying, ‘Farewell, vain world: and that which is vainest in’t, Ambition!’

Edgeworth, whom I think you remember at Cambridge, is come to live in town: and I see him often at the Museum. The want of books chiefly drove him from Italy: besides that he tells me he likes a p. 32constant change of scenes and ideas, and would be always about if he could. He is a very original man I think, and throws out much to be chewed and digested: but he is deficient in some elements that must combine to govern my love and admiration. He has much imagination of head, but none of heart: perhaps these are absurd distinctions: but I am no hand at these definitions. His great study is metaphysics: and Kant is his idol. He is rather without company in London, and I wish much to introduce him to such men as I know: but most of your Apostolic party who could best exchange ideas with him are not in town. He is full of his subjects, and only wants opponents to tilt at. . . .

The life of Coleridge [32] is indeed an unsatisfactory thing: I believe that everybody thinks so. You seem to think that it is purposely unsatisfactory, or rather dissatisfactory: but it seems to me to proceed from a kind of enervation in De Quincey. However, I don’t know how he supports himself in other writings. . . .

To fill up my letter I send you a sonnet of C. Lamb’s, out of his Album Verses—please to like it—‘Leisure.’

To John Allen.

Manchester, May 23, 1835.

Dear Allen,

I think that the fatal two months have elapsed, by which a letter shall become due to me from p. 33you. Ask Mrs. Allen if this is not so. Mind, I don’t speak this upbraidingly, because I know that you didn’t know where I was. I will tell you all about this by degrees. In the first place, I staid at Mirehouse till the beginning of May, and then, going homeward, spent a week at Ambleside, which, perhaps you don’t know, is on the shores of Winandermere. It was very pleasant there: though it was to be wished that the weather had been a little better. I have scarce done anything since I saw you but abuse the weather: but these four last days have made amends for all: and are, I hope, the beginning of summer at last. Alfred Tennyson staid with me at Ambleside: Spedding was forced to go home, till the last two days of my stay there. I will say no more of Tennyson than that the more I have seen of him, the more cause I have to think him great. His little humours and grumpinesses were so droll, that I was always laughing: and was often put in mind (strange to say) of my little unknown friend, Undine—I must however say, further, that I felt what Charles Lamb describes, a sense of depression at times from the overshadowing of a so much more lofty intellect than my own: this (though it may seem vain to say so) I never experienced before, though I have often been with much greater intellects: but I could not be mistaken in the universality of his mind; and perhaps I have received some benefit in the now more distinct consciousness of my dwarfishness. I think that you should keep all this to yourself, my dear Allen: I p. 34mean, that it is only to you that I would write so freely about myself. You know most of my secrets, and I am not afraid of entrusting even my vanities to so true a man. . . .

Pray, do not forget to say how the Freestone party are. My heart jumped to them, when I read in a guide book at Ambleside, that from Scawfell (a mountain in Westmoreland) you could see Snowdon. Perhaps you will not see the chain of ideas: but I suppose there was one, else I don’t know how it was that I tumbled, as it were, from the very summit of Scawfell, upon the threshold of Freestone. The mind soon traverses Wales. I have not been reading very much—(as if you ever expected that I did!)—but I mean, not very much for me—some Dante, by the aid of a Dictionary: and some Milton—and some Wordsworth—and some Selections from Jeremy Taylor, Barrow, etc., compiled by Basil Montagu—of course you know the book: it is published by Pickering. I do not think that it is very well done: but it has served to delight, and, I think, to instruct me much. Do you know South? He must be very great, I think. It seems to me that our old Divines will hereafter be considered our Classics—(in Prose, I mean)—I am not aware that any other nations have such books. A single selection from Jeremy Taylor is fine: but it requires a skilful hand to put many detached bits from him together: for a common editor only picks out the flowery, metaphorical, morsels: and so rather cloys: and gives quite a p. 35wrong estimate of the Author, to those who had no previous acquaintance with him: for, rich as Taylor’s illustrations, and grotesque as his images, are, no one keeps a grander proportion: he never huddles illustration upon the matter so as to overlay it, nor crowds images too thick together: which these Selections might make one unacquainted with him to suppose. This is always the fault of Selections: but Taylor is particularly liable to injury on this score. What a man he is! He has such a knowledge of the nature of man, and such powers of expressing its properties, that I sometimes feel as if he had had some exact counterpart of my own individual character under his eye, when he lays open the depths of the heart, or traces some sin to its root. The eye of his portrait expresses this keen intuition: and I think I should less like to have stood with a lie on my tongue before him, than before any other I know of. . . .

I beg you to give my best remembrances to your lady, who may be always sure that in all I wish of well for you, she is included: so that I take less care to make mention of her separately. . . .

Wherstead, July 4, 1835.

Dear Allen,

. . . My brother John’s wife, always delicate, has had an attack this year, which she can never get over: and while we are all living in this house cheerfully, she lives in separate rooms, can scarcely speak to us, p. 36or see us: and bears upon her cheek the marks of death. She has shewn great Christian dignity all through her sickness: was the only cheerful person when they supposed she could not live: and is now very composed and happy. You say sometimes how like things are to dreams: or, as I think, to the shifting scenes of a play. So does this place seem to me. All our family, except my mother, are collected here: all my brothers and sisters, with their wives, husbands, and children: sitting at different occupations, or wandering about the grounds and gardens, discoursing each their separate concerns, but all united into one whole. The weather is delightful: and when I see them passing to and fro, and hear their voices, it is like scenes of a play. I came here only yesterday. I have much to tell you of: I mean, much in my small way: I will keep all till I see you, for I don’t know with what to begin in a letter. . . .

Edgeworth introduced me to his wife and sister-in-law, who are very handsome Spanish ladies, seemingly of excellent sense. The wife is the gentler, and more feminine: and the sister more regularly handsome, and vivacious. I think that he is a very remarkable man: and I like him more the more I see of him.

What you say of Tennyson and Wordsworth is not, I think, wholly just. I don’t think that a man can turn himself so directly to the service of morality, unless naturally inclined: I think Wordsworth’s is a natural bias that way. Besides, one must have labourers of different kinds in the vineyard of p. 37morality, which I certainly look up to as the chief object of our cultivation: Wordsworth is first in the craft: but Tennyson does no little by raising and filling the brain with noble images and thoughts, which, if they do not direct us to our duty, purify and cleanse us from mean and vicious objects, and so prepare and fit us for the reception of the higher philosophy. A man might forsake a drunken party to read Byron’s Corsair: and Byron’s Corsair for Shelley’s Alastor: and the Alastor for the Dream of Fair Women or the Palace of Art: and then I won’t say that he would forsake these two last for anything of Wordsworth’s, but his mind would be sufficiently refined and spiritualised to admit Wordsworth, and profit by him: and he might keep all the former imaginations as so many pictures, or pieces of music, in his mind. But I think that you will see Tennyson acquire all that at present you miss: when he has felt life, he will not die fruitless of instruction to man as he is. But I dislike this kind of criticism, especially in a letter. I don’t know any one who has thought out any thing so little as I have. I don’t see to any end, and should keep silent till I have got a little more, and that little better arranged.

I am sorry that all this page is filled with this botheration, when I have a thousand truer and better things that I want to talk to you about. I will write to you again soon. If you please to write (but consider it no call upon you, for the letter I have just got from you is a stock that will last me in comfort this p. 38long while) I shall be at Wherstead all July—after that I know not where, but probably in Suffolk. Farewell, my best of fellows: there is no use saying how much I wish that all your sorrow will be turned to hope, and all your hope to joy. As far as we men can judge, you are worthy of all earthly happiness.

* * * * *

At the end of July, 1835, FitzGerald writes from Wherstead to Thackeray, who was then in Paris studying art:

‘My Father is determined to inhabit an empty house of his about fourteen miles off: [38] and we are very sorry to leave this really beautiful place. The other house has no great merit. So there is nothing now but packing up sofas, and pictures, and so on. I rather think that I shall be hanging about this part of the world all the winter: for my two sisters are about to inhabit this new house alone, and I cannot but wish to add my company to them now and then. . . .

‘My dear boy, God bless thee a thousand times over! When are we to see thee? How long are you going to be at Paris? What have you been doing? The drawing you sent me was very pretty. So you don’t like Raphael! Well, I am his inveterate admirer: and say, with as little affectation as I can, that his worst scrap fills my head more than all Rubens and Paul Veronese together—“the mind, the mind, Master Shallow!” You think this cant, I dare p. 39say: but I say it truly, indeed. Raphael’s are the only pictures that cannot be described: no one can get words to describe their perfection. Next to him, I retreat to the Gothic imagination, and love the mysteries of old chairs, Sir Rogers, etc. in which thou, my dear boy, art and shalt be a Raphael. To depict the true old English gentleman, is as great a work as to depict a Saint John, and I think in my heart I would rather have the former than the latter. There are plenty of pictures in London—some good Water-colours by Lewis—Spanish things. Two or three very vulgar portraits by Wilkie, at the Exhibition: and a big one of Columbus, half good, and half bad. There is always a spice of vulgarity about Wilkie. There is an Eastlake, but I missed it. Etty has boats full of naked backs as usual: but what they mean, I didn’t stop to enquire. He has one picture, however, of the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, which is sublime: though I believe nobody saw it, or thought about it but myself.’

About the same time that FitzGerald went to Boulge, George Crabbe, the Poet’s eldest son and biographer, was appointed to the Vicarage of the adjoining parish of Bredfield, and a friendship sprang up between them which was only terminated by Mr. Crabbe’s death in 1857.

Boulge

Hall, Woodbridge,

October 31, 1835.

Dear Allen,

I don’t know what has come over me of late, that I have not written to you, nor any body else for several months. I am sure it is not from any decrease of affection towards you. I now begin a letter merely on the score of wanting one from you: to let me know how you are; and Mrs. Allen too, especially. I hope to hear good news of her. Many things may have happened to you since I saw you: you may be a Bishop, for anything I know. I have been in Suffolk ever since I saw you. We are come to settle at this place: and I have been enjoying capital health in my old native air. I meant to have come to London for the winter: but my sisters are here, and I do not like to leave them. This parish is a very small one: it scarce contains fifty people: but that next to it, Bredfield, has more than four hundred: and some very poor indeed. We hope to be of some use: but the new Poor Laws have begun to be set afoot, and we don’t know who is to stop in his cottage, or who is to go to the Workhouse. How much depends upon the issue of this measure! I am no politician: but I fear that no political measure will ever adjust matters well between rich and poor. . . .

I have just read Southey’s Life of Cowper; that is p. 41to say, the first Volume. It is not a book to be read by every man at the fall of the leaf. It is a fearful book. Have you read it? Southey hits hard at Newton in the dark; which will give offence to many people: but I perfectly agree with him. At the same time, I think that Newton was a man of great power. Did you ever read his life by himself? Pray do, if you have not. His journal to his wife, written at sea, contains some of the most beautiful things I ever read: fine feeling in very fine English. . . .

Pray do write to me: a few lines soon are better than a three-decker a month hence: for I really want to know where and how you are: and so be a good boy for once in your life. Ever yours lovingly,

E. F. G.

To W. B. Donne.

London, March [21], 1836.

Dear Donne,

. . . As to the sponsorship, I was sure that you and Mrs. Donne would receive my apology as I meant it. Indeed I wish with you that people would speak their minds more sincerely than it is the custom to do; and recoin some of the every day compliments into a simpler form: but this is voted a stale subject, I believe. Anyhow, I will not preach to you who do not err: not to mention that I cannot by any means set up myself as any model of this virtue: whatever you may say to the contrary.

p. 42I have consulted my friend John Allen concerning your ancestor’s sermons: he says that the book is scarce. . . . I think that you should be possessed of him by all means, considering that you are his descendant. Allen read much of him at the Museum, and has always spoken very highly of him. As to doctrine, I believe Jeremy Taylor has never been quite blameless; but then he wrote many folios instead of Donne’s one: and I cannot help agreeing with Bayle that one of the disadvantages of much writing is, that a man is likely to contradict himself. If he does not positively do so, he may seem to do so, by using different expressions for the same thing, which expressions many readers may construe diversely: and this is especially likely to be the case with so copious and metaphorical a writer as Jeremy.

According to the principles contained in page 1 of this letter I will tell you that I thought the second volume of Southey [42] rather dull. But then I have only read it once; and I think that one is naturally impatient of all matter that does not absolutely touch Cowper: I mean, at the first reading; when one wants to know all about him. I dare say that afterwards I shall relish all the other relative matter, and contemporary history, which seems indeed well done. I am glad that you are so content with the book. We were all talking the other night of Basil Montagu’s new Life of Bacon—have you read it? It is said to be very elaborate and tedious. A good life of Bacon p. 43is much wanted. But perhaps it is as difficult to find a proper historian for him as for anyone that ever lived. But enough of grave matters. I have been very little to the Play: Vandenhoff’s Iago I did not see: for indeed what I saw of him in other characters did not constrain me to the theatre to see his Iago. . .

Spedding is just now furnishing chambers in Lincoln’s Inn Fields: so that we may look on him as a fixture in London. He and I went to dine with Tennant at Blackheath last Thursday: there we met Edgeworth, who has got a large house at Eltham, and is lying in wait for pupils: I am afraid he will not find many. We passed a very delightful evening. Tennant is making interest for a school at Cambridge: [43a] but I do not know if he is likely to succeed. And now I have told all the news I know, except that I hear that Sterling [43b] is very ill with an attack on his chest, which keeps him from preaching: and that Trench has been in London. Neither of these men do I know, but I hear of them.

To John Allen.

[Geldestone

Hall],

January 1, 1837.

Dear Allen,

A merry new year to you and yours. How have you been since I saw you? . . .

p. 44If you can find an old copy of Taylor’s Holy Living and Dying cheap and clean at the same time, pray buy it for me. It is for my old friend Mrs. Schutz: and she would not allow me to give it her: so that I give you her directions. . . .

I am very deep in my Aristophanes, and find the Edition I bought quite sufficient for my wants. One requires a translation of him less than of any of the Greeks I have read, because his construction is so clear and beautiful. Only his long words, and local allusions, make him difficult, so far as I have seen. He has made me laugh heartily, and wonder: but as to your calling him greater than Aeschylus or Sophocles, I do not agree with you. I have read nothing else. What a nice quiet speech Charles Kemble made on quitting the stage: almost the best I can remember on such an occasion. Did Spedding hear him? My dear Allen, I should often wish to see you and him of an evening as heretofore at this season in London: but I don’t see any likelihood of my coming till February at nearest. We live here the usual quiet country life: and now that the snow is so deep we are rather at a loss for exercise. It is very hard work toiling along the roads, and besides so blinding to the eyes. I take a spade, and scuppet [44] away the snow from the footpaths. . . .

Write to me at Boulge Hall, Woodbridge; for I think that the snows will be passable, and my sisters arrived there, before you write. There’s an insinuation p. 45for you. Make my remembrances to Mrs. Allen: and believe me

Yours ever most affectionately,

E. FitzGerald.

[Boulge

Hall],

Tuesday, January 10, 1837.

My dear Allen,

Another letter in so short a time will surprise you. My old Lady will be glad of a new edition of Jeremy Taylor, beside the old one. I remember you once gave me a very nice large duodecimo one: are these to be had, and cheap? It must have a good type, to suit old eyes. When you are possessed of these and the other books I begged you to ask for (except the Bacon which is for myself) do me one favour more: which is to book them per Coach at the White Horse, Piccadilly, directed to Mrs. Schutz, Gillingham Hall, Beccles. I should not have troubled you again, but that she, poor lady, is anxious to possess the books soon, as she never looks forward to living through a year: and she finds that Jeremy Taylor sounds a good note of preparation for that last hour which she looks upon as drawing nigh. I myself think she will live much longer: as she is wonderfully healthy for her time of life—seventy-six. [45] Sometimes I talk to her about you: and she loves you by report. You never grudge any trouble for your friends: but as this is a little act of kindness for an old and noble lady, I p. 46shall apologize no more for it. I will pay you all you disburse when I come to London.

I was made glad and sad last night in looking over some of your letters to me, ever since my stay at Tenby. I wonder within myself if we are changed since then. Do you remember that day when we sat upon that rock that runs out into the sea, and looked down into the clear water below? I must go to Tenby one of these days, and walk that old walk to Freestone. How well I remember what a quiet delight it was to walk out and meet you, when you were coming to stay a week with me once at my lodgings. . . .

And now, Sir, when you next go to the British Museum, look for a Poet named Vaughan. Do you know him? I read some fine sacred poems of his in a Collection of John Mitford’s: he selects them from a book of Vaughan’s called ‘Silex Scintillans,’ 1621. He seems to have great fancy and fervour and some deep thought. Yet many of the things are in the tricksy spirit of that time: but there is a little Poem beginning ‘They are all gone into a World of Light,’ etc., which shews him to be capable of much. Again farewell, my dear Allen: give my best remembrances to Mrs. Allen, who must think that I write to you as if you were still a Bachelor. Indeed, I think you had best burn this letter suddenly, after you have read my commissions. Βρεκεκεκεξ κοαξ κοαξ. There—I believe I can construe that passage as well as Porson.

p. 47Boulge Hall, Woodbridge.

[1837.]

My dear Allen,

Another commission in so short a time is rather too bad: but I know not to whom I can apply but to yourself: for our bookseller here could not get me what I want, seeing that I don’t exactly know myself. The book I want is an Athenæus, but the edition I know not: and therefore I apply to you who know my taste. . . .

There is a small Cottage of my Father’s close to the Lawn gates, where I shall fit up a room most probably. The garden I have already begun to work in. . . . Sometimes when I have sat dreaming about my own comforts I have thought to myself ‘If Allen ever would come and stay with me some days at my Cottage if I live there’—but I think you would not: ‘could not’ you will say, and perhaps truly. . . .

I am reading Plutarch’s Lives, which is one of the most delightful books I ever read. He must have been a Gentleman. My Aristophanes is nearly drained: that is, for the present first reading: for he will never be dry, apply as often as I may. My sisters are reading to me Lyell’s Geology of an Evening: there is an admirable chapter illustrative of human error and prejudice retarding the truth, which will apply to all sciences, I believe: and, if people would consider it, would be more valuable than the geological knowledge, though that is very valuable, I p. 48am sure. You see my reading is so small that I can soon enumerate all my books: and here you have them. . . .

[Boulge

Hall, Woodbridge,

21 April, 1837.]

Dear Allen,

Have you done with my Doctor? If you have, will you send him to me here: Boulge Hall, Woodbridge, per Shannon Coach? You may book it at the Boar and Castle, Oxford Street, close by Hanway Passage. This is not far out of your beat. Perhaps I should not have sent for this book (it is Bernard Barton the Quaker who asks to read it) but that it gives me an excuse also to talk a little to you. Ah! I wish you were here to walk with me now that the warm weather is come at last. Things have been delayed but to be more welcome, and to burst forth twice as thick and beautiful. This is boasting however, and counting of the chickens before they are hatched: the East winds may again plunge us back into winter: but the sunshine of this morning fills one’s pores with jollity, as if one had taken laughing gas. Then my house is getting on: the books are up in the bookshelves and do my heart good: then Stothard’s Canterbury Pilgrims are over the fireplace: Shakespeare in a recess: how I wish you were here for a day or two! My sister is very well and cheerful and we have kept house very pleasantly together. My brother John’s wife is, I fear, declining very fast: p. 49it is very probable that I shall have to go and see her before long: though this is a visit I should gladly be spared. They say that her mind is in a very beautiful state of peacefulness. She may rally in the summer: but the odds are much against her. We shall lose a perfect Lady, in the complete sense of the word, when she dies.

I have been doing very little since I have been here: having accomplished only a few Idylls of Theocritus, which harmonize with this opening of the fine weather. Is all this poor occupation for a man who has a soul to account for? You think so certainly. My dear Allen, you, with your accustomed humility, asked me if I did not think you changed when I was last in London: never did I see man less so: indeed you stand on too sure a footing to change, I am persuaded. But you will not thank me for telling you these things: but I wish you to believe that I rejoice as much as ever in the thought of you, and feel confident that you will ever be to me the same best of friends that you ever have been. I owe more to you than to all others put together. I am sure, for myself, that the main difference in our opinions (considered so destructive to friendship by so many pious men) is a difference in the Understanding, not in the Heart: and though you may not agree entirely in this, I am confident that it will never separate you from me.

Mrs. Schutz is much delighted with the books you got for her: and still enquires if you hurt your p. 50health in searching. This she does in all simplicity and kindness. She has been very ill all the winter: but I see by a letter I have just had from her that her mind is still cheerful and the same. The mens sana in corpore sano of old age is most to be wondered at.

To Bernard Barton. [50a]

London, April, 1838.

Dear Sir,

John, [50b] who is going down into Suffolk, will I hope take this letter and despatch it to you properly. I write more on account of this opportunity than of anything I have to say: for I am very heavy indeed with a kind of Influenza, which has blocked up most of my senses, and put a wet blanket over my brains. This state of head has not been improved by trying to get through a new book much in fashion—Carlyle’s French Revolution—written in a German style. An Englishman writes of French Revolutions in a German style. People say the book is very deep: but it appears to me that the meaning seems deep from lying under mystical language. There is no repose, nor equable movement in it: all cut up into short sentences half reflective, half narrative; so that one labours through it as vessels do through what is called a short sea—small, contrary going waves caused p. 51by shallows, and straits, and meeting tides, etc. I like to sail before the wind over the surface of an even-rolling eloquence, like that of Bacon or the Opium Eater. There is also pleasant fresh water sailing with such writers as Addison; is there any pond-sailing in literature? that is, drowsy, slow, and of small compass? Perhaps we may say, some Sermons. But this is only conjecture. Certainly Jeremy Taylor rolls along as majestically as any of them. We have had Alfred Tennyson here; very droll, and very wayward: and much sitting up of nights till two and three in the morning with pipes in our mouths: at which good hour we would get Alfred to give us some of his magic music, which he does between growling and smoking; and so to bed. All this has not cured my Influenza as you may imagine: but these hours shall be remembered long after the Influenza is forgotten.

I have bought scarce any new books or prints: and am not sorry to see that I want so little more. One large purchase I have made however, the Biographie Universelle, 53 Octavo Volumes. It contains everything, and is the very best thing of its kind, and so referred to by all historians, etc. Surely nothing is more pleasant than, when some name crosses one, to go and get acquainted with the owner of the name: and this Biographie really has found places for people whom one would have thought almost too small for so comprehensive a work—which sounds like a solecism, or Bull, does it not?