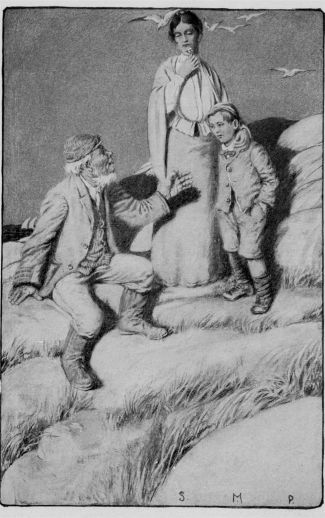

“I've a bad son, the day, Skipper Tommy,” said my Mother.—Page 23

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Doctor Luke of the Labrador, by Norman Duncan This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Doctor Luke of the Labrador Author: Norman Duncan Release Date: November 30, 2006 [EBook #19981] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DOCTOR LUKE OF THE LABRADOR *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

DOCTOR LUKE of THE LABRADOR BY NORMAN DUNCAN

GROSSET & DUNLAP Publishers – New York |

Copyright, 1904, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

|

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue Chicago: 63 Washington Street Toronto: 27 Richmond Street, W London: 21 Paternoster Square Edinburgh: 30 St. Mary Street |

To

My Own Mother

and to

her granddaughter

Elspeth

my niece

However bleak the Labrador—however naked and desolate that shore—flowers bloom upon it. However bitter the despoiling sea—however cold and rude and merciless—the gentler virtues flourish in the hearts of the folk.... And the glory of the coast—and the glory of the whole world—is mother-love: which began in the beginning and has continued unchanged to this present time—the conspicuous beauty of the fabric of life: the great constant of the problem.

N. D.

College Campus,

Washington, Pennsylvania,

October 15, 1904.

| I. | Our Harbour | 13 |

| II. | The World from the Watchman | 17 |

| III. | In the Haven of Her Arms | 29 |

| IV. | The Shadow | 35 |

| V. | Mary | 48 |

| VI. | The Man on the Mail-Boat | 57 |

| VII. | The Woman from Wolf Cove | 70 |

| VIII. | The Blind and the Blind | 79 |

| IX. | A Wreck on the Thirty Devils | 89 |

| X. | The Flight | 102 |

| XI. | The Women at the Gate | 110 |

| XII. | Doctor and I | 115 |

| XIII. | A Smiling Face | 125 |

| XIV. | In The Watches of the Night | 133 |

| XV. | The Wolf | 138 |

| XVI. | A Malady of the Heart | 150 |

| XVII. | Hard Practice | 167 |

| XVIII. | Skipper Tommy Gets a Letter | 182 |

| XIX. | The Fate of the Mail-Boat Doctor | 191 |

| XX. | Christmas Eve at Topmast Tickle | 202 |

| XXI. | Down North | 219 |

| XXII. | The Way from Heart’s Delight | 222 |

| XXIII. | The Course of True Love | 239 |

| XXIV. | The Beginning of the End | 258 |

| XXV. | A Capital Crime | 265 |

| XXVI. | Decoyed | 287 |

| XXVII. | The Day of the Dog | 305 |

| XXVIII. | In Harbour | 320 |

A cluster of islands, lying off the cape, made the shelter of our harbour. They were but great rocks, gray, ragged, wet with fog and surf, rising bleak and barren out of a sea that forever fretted a thousand miles of rocky coast as barren and as sombre and as desolate as they; but they broke wave and wind unfailingly and with vast unconcern—they were of old time, mighty, steadfast, remote from the rage of weather and the changing mood of the sea, surely providing safe shelter for us folk of the coast—and we loved them, as true men, everywhere, love home.

“’Tis the cleverest harbour on the Labrador!” said we.

When the wind was in the northeast—when it broke, swift and vicious, from the sullen waste of water beyond, whipping up the grey sea, driving in14 the vagrant ice, spreading clammy mist over the reefs and rocky headlands of the long coast—our harbour lay unruffled in the lee of God’s Warning. Skull Island and a shoulder of God’s Warning broke the winds from the north: the froth of the breakers, to be sure, came creeping through the north tickle, when the sea was high; but no great wave from the open ever disturbed the quiet water within. We were fended from the southerly gales by the massive, beetling front of the Isle of Good Promise, which, grandly unmoved by their fuming rage, turned them up into the black sky, where they went screaming northward, high over the heads of the white houses huddled in the calm below; and the seas they brought—gigantic, breaking seas—went to waste on Raven Rock and the Reef of the Thirty Black Devils, ere, their strength spent, they growled over the jagged rocks at the base of the great cliffs of Good Promise and came softly swelling through the broad south tickle to the basin. The west wind came out of the wilderness, fragrant of the far-off forest, lying unknown and dread in the inland, from which the mountains, bold and blue and forbidding, lifted high their heads; and the mist was then driven back into the gloomy seas of the east, and the sun was out, shining warm and yellow, and the sea, lying in the lee of the land, was all aripple and aflash.15

When the spring gales blew—the sea being yet white with drift-ice—the schooners of the Newfoundland fleet, bound north to the fishing, often came scurrying into our harbour for shelter. And when the skippers, still dripping the spray of the gale from beard and sou’wester, came ashore for a yarn and an hospitable glass with my father, the trader, many a tale of wind and wreck and far-away harbours I heard, while we sat by the roaring stove in my father’s little shop: such as those which began, “Well, ’twas the wonderfullest gale o’ wind you ever seed—snowin’ an’ blowin’, with the sea in mountains, an’ it as black as a wolf’s throat—an’ we was somewheres off Cape Mugford. She were drivin’ with a nor’east gale, with the shore somewheres handy t’ le’ward. But, look! nar a one of us knowed where she were to, ’less ’twas in the thick o’ the Black Heart Reefs....” Stout, hearty fellows they were who told yarns like these—thick and broad about the chest and lanky below, long-armed, hammer-fisted, with frowsy beards, bushy brows, and clear blue eyes, which were fearless and quick to look.

“’Tis a fine harbour you got here, Skipper David Roth,” they would say to my father, when it came time to go aboard, “an’ here, zur,” raising the last glass, “is t’ the rocks that make it!”16

“T’ the schooners they shelter!” my father would respond.

When the weather turned civil, I would away to the summit of the Watchman—a scamper and a mad climb—to watch the doughty little schooners on their way. And it made my heart swell and flutter to see them dig their noses into the swelling seas—to watch them heel and leap and make the white dust fly—to feel the rush of the wet wind that drove them—to know that the grey path of a thousand miles was every league of the way beset with peril. Brave craft! Stout hearts to sail them! It thrilled me to watch them beating up the suddy coast, lying low and black in the north, and through the leaden, ice-strewn seas, with the murky night creeping in from the open. I, too, would be the skipper of a schooner, and sail with the best of them!

“A schooner an’ a wet deck for me!” thought I.

And I loved our harbour all the more for that.

Thus, our harbour lay, a still, deep basin, in the shelter of three islands and a cape of the mainland: and we loved it, drear as it was, because we were born there and knew no kinder land; and we boasted it, in all the harbours of the Labrador, because it was a safe place, whatever the gale that blew.

The Watchman was the outermost headland of our coast and a landmark from afar—a great gray hill on the point of Good Promise by the Gate; our craft, running in from the Hook-an’-Line grounds off Raven Rock, rounded the Watchman and sped thence through the Gate and past Frothy Point into harbour. It was bold and bare—scoured by the weather—and dripping wet on days when the fog hung thick and low. It fell sharply to the sea by way of a weather-beaten cliff, in whose high fissures the gulls, wary of the hands of the lads of the place, wisely nested; and within the harbour it rose from Trader’s Cove, where, snug under a broken cliff, stood our house and the little shop and storehouse and the broad drying-flakes and the wharf and fish-stages of my father’s business. From the top there was a far, wide outlook—all sea and rock: along the ragged, treeless coast, north and south, to the haze wherewith, in distances beyond the ken of lads, it melted; and upon the thirty wee white houses of our folk, scattered haphazard about the harbour water,18 each in its own little cove and each with its own little stage and great flake; and over the barren, swelling rock beyond, to the blue wilderness, lying infinitely far away.

I shuddered when from the Watchman I looked upon the wilderness.

“’Tis a dreadful place,” I had heard my father say. “Men starves in there.”

This I knew to be true, for, once, I had seen the face of a man who came crawling out.

“The sea is kinder,” I thought.

Whether so or not, I was to prove, at least, that the wilderness was cruel.

One blue day, when the furthest places on sea and land lay in a thin, still haze, my mother and I went to the Watchman to romp. There was place there for a merry gambol, place, even, led by a wiser hand, for roaming and childish adventure—and there were silence and sunlit space and sea and distant mists for the weaving of dreams—ay, and, upon rare days, the smoke of the great ships, bound down the Straits—and when dreams had worn the patience there were huge loose rocks handy for rolling over the brow of the cliff—and there was gray moss in the hollows, thick and dry and soft, to sprawl on and rest from the delights of19 the day. So the Watchman was a playground for my mother and me—my sister, my elder by seven years, was all the day long tunefully busy about my father’s comfort and the little duties of the house—and, on that blue day, we climbed the broken cliff behind our house and toiled up the slope beyond in high spirits, and we were very happy together; for my mother was a Boston maid, and, though she turned to right heartily when there was work to do, she was not like the Labrador born, but thought it no sin to wander and laugh in the sunlight of the heads when came the blessed opportunity.

“I’m fair done out,” said I, at last, returning, flushed, from a race to Beacon Rock.

“Lie here, Davy—ay, but closer yet—and rest,” said she.

I flung myself at full length beside her, spreading abroad my sturdy little arms and legs; and I caught her glance, glowing warm and proud, as it ran over me, from toe to crown, and, flashing prouder yet through a gathering mist of tears, returned again.

“I knows why you’re lookin’ at me that way,” said I.

“And why?” said she.

“’Tis for sheer love o’ me!”

She was strangely moved by this. Her hands, passionately clasped of a sudden, she laid upon20 her heart; and she drew a sharp, quivering breath.

“You’re getting so—so—strong and—and—so big!” she cried.

“Hut!” said I. “’Tis nothin’ t’ cry about!”

“Oh,” she sobbed, “I’m proud t’ be the mother of a son!”

I started up.

“I’m that proud,” she went on, hovering now between great joy and pain, “that it—it—fair hurts me!”

“I’ll not have you cry!” I protested.

She caught me in her arms and we broke into merry laughter. Then to please her I said that I would gather flowers for her hair—and she would be the stranded mermaid and I the fisherman whom she besought to put her back in the sea and rewarded with three wishes—and I sought flowers everywhere in the hollows and crevices of the bald old Watchman, where, through years, some soil had gathered, but found only whisps of wiry grass and one wretched blossom; whereupon I returned to her very wroth.

“God made a botch o’ the world!” I declared.

She looked up in dismay.

“Ay,” I repeated, with a stamp of the foot, “a wonderful botch o’ the world He’s gone an’ made. Why, they’s but one flower on the Watchman!”21

She looked over the barren land—the great gray waste of naked rock—and sighed.

“But one?” she asked, softly.

“An I was God,” I said, indignantly, “I’d have made more flowers an’ made un bigger.”

She smiled in the way of one dreaming.

“Hut!” I went on, giving daring wing to my imagination. “I’d have made a hundred kinds an’ soil enough t’ grow un all—every one o’ the whole hundred! I’d have——”

She laid a soft hand on my lips. “’Tis a land,” she whispered, with shining eyes, “that grows rosy lads, and I’m well content!”

“’Tis a poor way,” I continued, disregarding her caress, “t’ gather soil in buckets. I’d have made enough t’ gather it in barrows! I’d have made lots of it—heaps of it. Why,” I boasted, growing yet more recklessly prodigal, “I’d have made a hill of it somewheres handy t’ every harbour in the world—as big as the Watchman—ay, an’ handy t’ the harbours, so the folk could take so much as they wanted—t’ make potato-gardens—an’—an’ t’ make the grave-yards deep enough. ’Tis a wonderful poor way,” I concluded with contempt, “t’ have t’ gather it in buckets from the rocks!”

My mother was laughing heartily now.

“’Twould not be a better world, thinks you?”22 said I. “Ay, but I could do better than that! Hut!” I cried, at last utterly abandoned to my imagination, “I’d have more things than potatoes grow in the ground an’ more things than berries grow on bushes. What would I have grow in the ground, says you? Is you thinkin’ I don’t know? Oh, ay, mum,” I protested, somewhat at a loss, but very knowingly, “I knows!” I was now getting rapidly beyond my depth; but I plunged bravely on, wondering like lightning, the while, what else could grow in the ground and on bushes. “I’d have flour grow in the ground, mum,” I cried, triumphantly, “an’ I’d have sea-boots an’ sou’westers grow on the bushes. An’, ecod!” I continued, inspired, “I’d have fishes grow on bushes, already split an’ cleaned!”

What other improvements I would have made on the good Lord’s handiwork I do not know. Skipper Tommy Lovejoy, being on the road to Trader’s Cove from the Rat Hole, where he lived alone with his twin lads, had spied us from Needle Rock, and now came puffing up the hill to wish my mother good-day: which, indeed, all true men of the harbour never failed to do, whenever they came near. He was a short, marvellously broad, bow-legged old man—but yet straight and full of strength and fine hope—all the while dressed in tight white moleskin23 (much soiled by the slime of the day’s work), long skin boots, tied below the knees, and a ragged cloth cap, which he kept pulled tight over his bushy grey hair. There was a mild twinkle forever lying in the depths of his blue eyes, and thence, at times, overflowing upon his broad brown face, which then rippled with wrinkles, from the roots of his hair to the fringe of white beard under his chin, in a way at once to make one laugh with him, though one could not quite tell why. We lads of the harbour loved him very much, for his good-humour and for his tenderness—never more so, however, than when, by night, in the glow of the fire, he told us long tales of the fairies and wicked elves he had dealt with in his time, twinkling with every word, so that we were sorely puzzled to know whether to take him in jest or earnest.

“I’ve a very bad son, the day, Skipper Tommy,” said my mother, laying a fond hand on my head.

“Have you, now, mum!” cried the skipper, with a wink. “’Tis hard t’ believe. He’ve been huntin’ gulls’ nests in parlous places on the cliff o’ the Watchman, I’m thinkin’.”

“’Tis worse than that.”

“Dear man! Worse than that, says you? Then he’ve took the punt beyond the Gate all by hisself.”24

“’Tis even worse than that. He’s not pleased with the dear Lord’s world.”

Skipper Tommy stopped dead and stared me in the eye—but not coldly, you must know; just in mild wonder, in which, it may be, was mixed some admiration, as though he, too, deep in his guileless old heart, had had some doubt which he dared not entertain.

“Ay,” said I, loftily, “He’ve not made flowers enough t’ suit my taste.”

Skipper Tommy rubbed his nose in a meditative way. “Well,” he drawled, “He haven’t made many, true enough. I’m not sayin’ He mightn’t have made more. But He’ve done very well. They’s enough—oh, ay, they’s enough t’ get along with. For, look you! lad, they’s no real need o’ any more. ’Twas wonderful kind of Un,” he went on, swept away by a flood of good feeling, as often happened, “t’ make even one little flower. Sure, He didn’t have t’ do it. He just went an’ done it for love of us. Ay,” he repeated, delighting himself with this new thought of his Lord’s goodness, “’twas wonderful kind o’ the Lard t’ take so much trouble as that!”

My mother was looking deep into Skipper Tommy’s eyes as though she saw some lovely thing therein.

“Ay,” said I, “’twas fair kind; but I’m wishin’ He’d been a bit more free.”25

My mother smiled at that. Then, “And my son,” she said, in the way of one poking fun, “would have flour grow out of the ground!”

“An’ did he say that!” cried Skipper Tommy.

My mother laughed, and Skipper Tommy laughed uproariously, and loudly slapped his thick thigh; and I felt woefully foolish, and wondered much what depth of ignorance I had betrayed, but I laughed, too, because Skipper Tommy laughed so heartily and opened his great mouth so wide; and we were all very merry for a time. At last, while I wondered, I thought that, perhaps, flour did grow, after all—though, for the life of me, I could not tell how—and that my mother and Skipper Tommy knew it well enough; whereupon I laughed the merrier.

“Come, look you!” then said Skipper Tommy, gently taking the lobe of my ear between his thick, hard thumb and forefinger. “Don’t you go thinkin’ you could make better worlds than the Lard. Why, lad, ’tis but play for Him! He’ve no trouble makin’ a world! I’m thinkin’ He’ve made more than one,” he added, his voice changing to a knowing whisper. “’Tis my own idea, but,” now sagely, “I’m thinkin’ He did. ’Tis like that this was the first, an’ He done better when He got His hand in. Oh, ay, nar a doubt He done better with the rest! But He done wonderful well with this one. When you’re so old26 as me, lad, you’ll know that though the Lard made few flowers He put a deal o’ time an’ labour on the harbours; an’ when you’re beatin’ up t’ the Gate, lad, in a gale o’ wind—an’ when you thinks o’ the quiet place t’other side o’ Frothy Point—you’ll know the Lard done well by all the folk o’ this world when He made safe harbours instead o’ wastin’ His time on flowers. Ay, lad, ’tis a wonderful well built world; an’ you’ll know it—then!”

We turned homeward—down the long road over the shoulder of the Watchman; for the evening was drawing near.

“They’s times,” said Skipper Tommy, giving his nose a puzzled tweak, “when I wonders how He done it. ’Tis fair beyond me! I wonders a deal, now, mum,” turning to my mother, his face lighting with interest, “about they stars. Now, mum,” smiling wistfully, “I wonders ... I wonders ... how He stuck un up there in the sky. Ah,” with a long sigh, “I’d sure like t’ know that! An’ wouldn’t you, mum? Ecod! but I would like t’ know that! ’Twould be worth while, I’m thinkin’. I’m wishin’ I could find out. But, hut!” he cried, with a laugh which yet rang strangely sad in my ears, “’tis none o’ my business. ’Twould be a queer thing, indeed, if men went pryin’ into the Lard’s secrets. He’d fix un, I ’low—He’d snarl un all up—He’d let un think theirselves27 wise an’ guess theirselves mad! That’s what He’d do. But, now,” falling again into a wistful, dreaming whisper, “I wonders ... wonders ... how He does stick them stars up there. I’m thinkin’ I’ll try t’ think that out—some day—so people could know, an’ wouldn’t have t’ wonder no more. I—wonders—if I could!”

We walked on in silence—down the last slope, and along the rocky path to Trader’s Cove; and never a word was spoken. When we came to the turn to our house we bade the skipper good-evening.

“Don’t you be forgettin’,” he said, tipping up my face with a finger under my chin, “that you’ll soon be thinkin’ more o’ harbours than o’ flowers.”

I laughed.

“But, ecod!” he broke out, violently rubbing his nose, until I was fairly concerned for it, so red did it turn, “that was a wonderful good idea about the flour!”

My mother looked at him sharply; then her eyes twinkled, and she hid a smile behind her hand.

“’Twould be a good thing t’ have it grow,” the old man continued. “’Twould be far better than—than—well, now—makin’ it the way they does. Ecod!” he concluded, letting his glance fall in bewilderment on the ground, “I wonders how they does make flour. I wonders ... wonders ...28 where they gets the stuff an’—an’—how they makes it!”

He went off, wondering still; and my mother and I went slowly home, and sat in the broad window of our house, which overlooked the harbour and fronted the flaring western sky; and then first she told me of the kind green world beyond.

There was a day not far distant—my father had told my mother with a touch of impatience that it must come for all sons—when Skipper Tommy took me with one of the twin lads in the punt to the Hook-an’-Line grounds to jig, for the traps were doing poorly with the fish, the summer was wasting and there was nothing for it but to take to hook and line: which my father’s dealers heartily did, being anxious to add what fish they could to the catch, though in this slower way. And it was my first time beyond the Gate—and the sea seemed very vast and strange and sullen when we put out at dawn—and when the long day was near done the wind blew gray and angry from the north and spread a thickening mist over the far-off Watchman—and before night closed, all that Skipper Tommy had said of harbours and flowers came true in my heart.

“We’ll be havin’ t’ beat up t’ the Gate,” said he, as he hauled in the grapnel.

“With all the wind she can carry,” added little Jacky, bending to lift the mast into the socket.30

In truth, yes—as it seemed to my unknowing mind: she had all the wind she could carry. The wind fretted the black sea until it broke all roundabout; and the punt heeled to the gusts and endlessly flung her bows up to the big waves; and the spray swept over us like driving rain, and was bitter cold; and the mist fell thick and swift upon the coast beyond. Jacky, forward with the jib-sheet in his capable little fist and the bail bucket handy, scowled darkly at the gale, being alert as a cat, the while; and the skipper, his mild smile unchanged by all the tumult, kept a hand on the mainsheet and tiller, and a keen, quiet eye on the canvas and on the vanishing rocks whither we were bound. And forth and back she went, back and forth, again and again, without end—beating up to harbour.

“Dear man!” said Skipper Tommy, with a glance at the vague black outline of the Watchman, “but ’tis a fine harbour!”

“’Tis that,” sighed Jacky, wistfully, as a screaming little gust heeled the punt over; “an’—an’—I wisht we was there!”

Skipper Tommy laughed at his son.

“I does!” Jacky declared.

“I—I—I’m not so sure,” I stammered, taking a tighter grip on the gunwale, “but I wisht we was—there—too.”31

“You’ll be wishin’ that often,” said Skipper Tommy, pointedly, “if you lives t’ be so old as me.”

We wished it often, indeed, that day—while the wind blustered yet more wildly out of the north and the waves tumbled aboard our staggering little craft and the night came apace over the sea—and we have wished it often since that old time, have Jacky and I, God knows! I had the curious sensation of fear, I fancy—though I am loath to call it that—for the first time in my life; and I was very much relieved when, at dusk, we rounded the looming Watchman, ran through the white waters and thunderous confusion of the Gate, with the breakers leaping high on either hand, sharply turned Frothy Point and came at last into the ripples of Trader’s Cove. Glad I was, you may be sure, to find my mother waiting on my father’s wharf, and to be taken by the hand, and to be led up the path to the house, where there was spread a grand supper of fish and bread, which my sister had long kept waiting; and, after all, to be rocked in the broad window, safe in the haven of my mother’s arms, while the last of the sullen light of day fled into the wilderness and all the world turned black.

“You’ll be singin’ for me, mum, will you not?” I whispered.

“And what shall I sing, lad?” said she.32

“You knows, mum.”

“I’m not so sure,” said she. “Come, tell me!”

What should she sing? I knew well, at that moment, the assurance my heart wanted: we are a God-fearing people, and I was a child of that coast; and I had then first come in from a stormy sea. There is a song——

“’Tis, ‘Jesus Saviour Pilot Me,’” I answered.

“I knew it all the time,” said she; and,

“‘Jesus, Saviour, pilot me,

Over life’s tempestuous sea,’”

she sang, very softly—and for me alone—like a sweet whisper in my ear.

“‘Unknown waves before me roll,

Hiding rock and treacherous shoal;

Chart and compass came from Thee:

Jesus, Saviour, pilot me!’”

“I was thinkin’ o’ that, mum, when we come through the Gate,” said I. “Sure, I thought Skipper Tommy might miss the Way, an’ get t’other side o’ the Tooth, an’ get in the Trap, an’ go t’ wreck on the Murderers, an’——”

“Hush, dear!” she whispered. “Sure, you’ve no cause to fear when the pilot knows the way.”

The feeling of harbour—of escape and of shelter and brooding peace—was strong upon me while we33 sat rocking in the failing light. I have never since made harbour—never since come of a sudden from the toil and the frothy rage of the sea by night or day, but my heart has felt again the peace of that quiet hour—never once but blessed memory has given me once again the vision of myself, a little child, lying on my mother’s dear breast, gathered close in her arms, while she rocked and softly sang of the tempestuous sea and a Pilot for the sons of men, still rocking, rocking, in the broad window of my father’s house. I protest that I love my land, and have from that hour, barren as it is and as bitter the sea that breaks upon it; for I then learned—and still know—that it is as though the dear God Himself made harbours with wise, kind hands for such as have business in the wild waters of that coast. And I love my life—and go glad to the day’s work—for I have learned, in the course of it and by the life of the man who came to us, that whatever the stress and fear of the work to be done there is yet for us all a refuge, which, by way of the heart, they find who seek.

And I fell asleep in my mother’s arms, and by and by my big father came in and laughed tenderly to find me lying there; and then, as I have been told, laughing softly still they carried me up and flung me34 on my bed, flushed and wet and limp with sound slumber, where I lay like a small sack of flour, while together they pulled off my shoes and stockings and jacket and trousers and little shirt, and bundled me into my night-dress, and rolled me under the blanket, and tucked me in, and kissed me good-night.

When my mother’s lips touched my cheek I awoke. “Is it you, mama?” I asked.

“Ay,” said she; “’tis your mother, lad.”

Her hand went swiftly to my brow, and smoothed back the tousled, wet hair.

“Is you kissed me yet?”

“Oh, ay!” said she.

“Kiss me again, please, mum,” said I, “for I wants—t’ make sure—you done it.”

She kissed me again, very tenderly; and I sighed and fell asleep, content.

When the mail-boat left our coast to the long isolation of that winter my mother was even more tender with the scrawny plants in the five red pots on the window-shelf. On gray days, when our house and all the world lay in the soggy shadow of the fog, she fretted sadly for their health; and she kept feverish watch for a rift in the low, sad sky, and sighed and wished for sunlight. It mystified me to perceive the wistful regard she bestowed upon the stalks and leaves that thrived the illest—the soft touches for the yellowing leaves, and, at last, the tear that fell, when, withered beyond hope, they were plucked and cast away—and I asked her why she loved the sick leaves so; and she answered that she knew but would not tell me why. Many a time, too, at twilight, I surprised her sitting downcast by the window, staring out—and far—not upon the rock and sea of our harbour, but as though through the thickening shadows into some other place.

“What you lookin’ at, mum?” I asked her, once.36

“A glory,” she answered.

“Glory!” said I. “They’s no glory out there. The night falls. ’Tis all black an’ cold on the hills. Sure, I sees no glory.”

“’Tis not a glory, but a shadow,” she whispered, “for you!”

Nor was I now ever permitted to see her in disarray, but always, as it seemed to me, fresh from my sister’s clever hands, her hair laid smooth and shining, her simple gown starched crisp and sweetly smelling of the ironing board; and when I asked her why she was never but thus lovely, she answered, with a smile, that surely it pleased her son to find her always so: which, indeed, it did. I felt, hence, in some puzzled way, that this display was a design upon me, but to what end I could not tell. And there was an air of sad unquiet in the house: it occurred to my childish fancy that my mother was like one bound alone upon a long journey; and once, deep in the night, when I had long lain ill at ease in the shadow of this fear, I crept to her door to listen, lest she be already fled, and I heard her sigh and faintly complain; and then I went back to bed, very sad that my mother should be ailing, but now sure that she would not leave me.

Next morning my father leaned over our breakfast table and laid his broad hand upon my mother’s37 shoulder; whereupon she looked up smiling, as ever she did when that big man caressed her.

“I’ll be havin’ the doctor for you,” he said.

She gave him a swift glance of warning—then turned her wide eyes upon me.

“Oh,” said my father, “the lad knows you is sick. ’Tis no use tryin’ t’ keep it from un any more.”

“Ay,” I sobbed, pushing my plate away, for I was of a sudden no longer hungry, “I heared you cryin’ las’ night.”

My sister came quickly to my side, and wound a soft arm about my neck, and drew my head close to her heart, and kissed me many times; and when she had soothed me I looked up and found my mother gloriously glad that I had cried.

“’Tis nothing,” then she said, with a rush of tenderness for my grief. “’Tis not hard to bear. ’Tis——”

“Ay, but,” said my father, “I’ll be havin’ the doctor t’ see you.”

My mother pooh-poohed it all. The doctor? For her? Not she! She was not sick enough for that!

“I’m bent,” said my father, doggedly, “on havin’ that man.”

“David,” cried my mother, “I’ll not have you do it!”

“I’ll have my way of it,” said my father. “I’m38 bent on it, an’ I’ll be put off no longer. ’Tis no use, m’am—nar a bit! The doctor’s comin’ t’ see you.”

“Ah, well!” sighed my mother.

“Ay,” said my father, “I’ll have that man ashore when the mail-boat comes in the spring. ’Tis well on t’ December now,” he went on, “an’ it may be we’ll have an early break-up. Sure, if they’s westerly winds in the spring, an’ the ice clears away in good season, we’ll be havin’ the mail-boat north in May. Come, now! ’twill not be later than June, I ’low. An’ I’ll have that doctor ashore in a hurry, mark my words, when the anchor’s down. That I will!”

“’Tis a long time,” said my mother.

Every morning, thereafter, she said that she was better—always better—much, much better. ’Twas wonderful, she said, ’twas fair past making out, indeed, that she should so soon grow into a fine, hearty woman again; and ’twould be an easy matter, said she, for the mail-boat doctor to cure her—when he came. And she was now more discreet with her moods; not once did I catch her brooding alone, though more than once I lay in wait in dark corners or peered through the crack in the door; and she went smiling about the house, as of old—but yet not as of old; and I puzzled over the difference, but could not discover it. More often, now, at twilight, she lured me to her lap, where I was never loath to39 go, great lad of nine years though I was; and she sat silent with me, rocking, rocking, while the deeper night came down—and she kissed me so often that I wondered she did not tire of it—and she stroked my brow and cheeks, and touched my eyes, and ran her finger-tips over my eyebrows and nose and lips, ay, and softly played with my lips—and at times she strained me so hard to her breast that I near complained of the embrace—and I was no more driven off to bed when my eyes grew heavy, but let lie in her arms, while we sat silent, rocking, rocking, until long, long after I had fallen asleep. And once, at the end of a sweet, strange hour, making believe to play, she gently pried my eyes wide open and looked far into their depths—so deep, so long, so searchingly, so strangely, that I waxed uneasy under the glance.

“Wh-wh-what—what you——” I began, inarticulately.

“What am I looking for?” she interrupted, speaking quickly.

“Ay,” I whimpered, for I was deeply agitated; “what you lookin’ for?”

“For your heart,” said she.

I did not know what she meant; and I wondered concerning the fancy she had, but did not ask, for there was that in her voice and eyes that made me very solemn.40

“’Tis but a child’s heart,” she sighed, turning away. “’Tis but like the hearts,” she whispered, “of all children. I cannot tell—I cannot tell,” she sobbed, “and I want—oh, I want so much—to know!”

“Don’t cry!” I pleaded, thrown into an agony by her tears, in the way of all children.

She sat me back in her lap. “Look in your mother’s eyes, lad,” said she, “and say after me this: ‘My mother——’”

“‘My mother——’” I repeated, very soberly.

“‘Looked upon my heart——’”

“‘Looked upon my heart——’” said I.

“‘And found it brave——’”

“‘An’ found it brave——’”

“‘And sweet——’”

“‘An’ sweet——’”

“‘Willing for the day’s work——’” said she.

“‘Willing for the day’s work——’” I repeated.

“‘And harbouring no shameful hope.’”

“‘An’ harbouring—no shameful—hope.’”

Again and again she had me say it—until I knew it every word by heart.

“Ah,” said she, at last, “but you’ll forget!”

“No, no!” I cried. “I’ll not forget. ‘My mother looked upon my heart,’” I rattled, “‘an’ found it brave an’ sweet, willing for the day’s work41 an’ harbouring no shameful hope.’ I’ve not forgot! I’ve not forgot!”

“He’ll forget,” she whispered, but not to me, “like all children.”

But I have not forgotten—I have not forgotten—I have never forgotten—that when I was a child my mother looked upon my heart and found it brave and sweet, willing for the day’s work and harbouring no shameful hope.

The winter fell early and with ominous severity. Our bleak coast was soon too bitter with wind and frost and snow for the folk to continue in their poor habitations. They were driven in haste to the snugger inland tilts, which lay in a huddle at the Lodge, far up Twisted Arm, in the blessed proximity of fire-wood—there to trap and sleep in hardly mitigated misery until the kindlier spring days should once again invite them to the coast. My father, the only trader on forty miles of our coast, as always dealt them salt beef and flour and tea with a free hand, until, at last, the storehouses were swept clean of food, save sufficient for our own wants: his great heart hopeful that the catch of next season, and the honest hearts of the folk, and the mysterious favor of the Lord, would all conspire to repay him. And so they departed, bag and baggage, youngsters42 and dogs; and the waste of our harbour and of the infinite roundabout was left white and silent, as of death itself. But we dwelt on in our house under the sheltering Watchman; for my father, being a small trader, was better off than they—though I would not have you think him of consequence elsewhere—and had builded a stout house, double-windowed, lined with felt and wainscotted with canvas, so that but little frost formed on the walls of the living rooms, and that only in the coldest weather.

“’Tis cozy enough,” said my father, chucking my mother under the chin, “even for a maid a man might cotch up Boston way!”

Presently came Skipper Tommy Lovejoy by rollicking dog-team from the Lodge to inquire after my mother’s health—to cheer us, it may be, I’m thinking, with his hearty way, his vast hope, his odd fancies, his ruddy, twinkling face. Most we laughed when he described his plan (how seriously conceived there was no knowing) for training whales to serve as tugboats in calms and adverse winds. It appeared, too, that a similar recital had been trying to the composure of old Tom Tot, of our harbour, who had searched the Bible for seven years to discover therein a good man of whom it was said that he laughed, and, failing utterly, had thereupon vowed never again to commit the sin of levity.43

“Sure, I near fetched un,” said Skipper Tommy, gleefully, “with me whales. I come near makin’ Tom Tot break that scandalous vow, zur, indeed I did! He got wonderful purple in the face, an’ choked in a fearsome way, when I showed un my steerin’ gear for the beast’s tail, but, as I’m sad t’ say, zur, he managed t’ keep it in without bustin’. But I’ll get un yet, zur—oh, ay, zur—just leave un t’ me! Ecod! zur, I’m thinkin’ he’ll capsize with all hands when I tells un I’m t’ have a wheel-house on the forward deck o’ that wha-a-ale!”

But the old man soon forgot all about his whales, as he had forgotten to make out the strange way the Lord had discovered to fasten His stars to the sky; moved by a long contemplation of my mother’s frailty, he had a nobler inspiration.

“’Tis sad, lass,” he said, his face aquiver with sympathy, “t’ think that we’ve but one doctor t’ cure the sick, an’ him on the mail-boat. ’Tis wonderful sad t’ think o’ that! ’Tis a hard case,” he went on, “but if a man only thunk hard enough he’d find a way t’ mend it. Sure, what ought t’ be mended can be mended. ’Tis the way o’ the world. If a man only thinks hard an’ thinks sensible, he’ll find a way, zur, every time. ’Tis easy t’ think hard, but ’tis sometimes hard,” he added, “t’ think t’ the point.”44

We were silent while he continued lost in deep and puzzled thought.

“Ecod!” he burst out. “I got it!”

“Have you, now?” cried my father, half amused, half amazed.

“Just this minute, zur,” said the skipper, in a glow of delighted astonishment. “It come t’ me all t’ oncet.”

“An’ what is it?”

“’Tis a sort o’ book, zur!”

“A book?”

“Ay, ’tis just a book. Find out all the cures in the world an’ put un in a book. Get the doctor-women’s, an’ the healers’, an’ the real doctor’s, an’ put un right in a book. Has you got the dip-theria? Ask the book what t’ do. ‘Dip-theria?’ says the book t’ you. ‘Well, that’s sad. Tie a split herring round your neck.’ S’pose you got the salt-water sores. What do you do, then? Why, turn t’ the book. ‘Oh, ’tis nothin’ t’ cure that,’ says the book. ‘Wear a brass chain on your wrist, lad, an’ you’ll be troubled no more.’ Take it, now, when you got blood-poison in the hand. What is you t’ do, you wants t’ know? ‘Blood-poison in the hand?’ says the book. ‘Good gracious, that’s awful! Cut off your hand.’ ’Twould be a wonderful good work,” the skipper concluded, “t’ make a book like that!”45 It appeared to me that it would.

“I wonder,” the skipper went on, staring at the fire, a little smile playing upon his face, “if I couldn’t do that! ’Twould surely be a thing worth doin’. I wonder—I wonder—if I couldn’t manage—somehow—t’ do it!”

We said nothing; for he was not thinking of us, any more, as we knew—but only dreaming of the new and beneficent work which had of a sudden appeared to him.

“But I isn’t able t’ write,” he muttered, at last. “I—I—wisht I could!”

“’Twould be a wonderful fine work for a man t’ do,” said my father.

“’Tis a wonder, now,” said Skipper Tommy, looking up with a bright face, “that no one ever thought o’ doin’ that afore. T’ my mind,” he added, much puzzled, “’tis very queer, indeed, that they’s nar a man in all the world t’ think o’ that—but me!”

My mother smiled.

“I’m thinkin’ I’ll just have t’ try,” Skipper Tommy went on, frowning anxiously. “But, ecod!” he cried, “maybe the Lard wouldn’t like it. Now, maybe, He wants us men t’ mind our business. Maybe, He’d say, ‘You keep your finger out o’ My pie. Don’t you go makin’ no books about cures.’ But, oh, no!” with the overflow of fine feeling which46 so often came upon him. “Why, He wouldn’t mind a little thing like that. Sure, I wouldn’t mind it, meself! ‘You go right ahead, lad,’ He’d say, ‘an’ try t’ work your cures. Don’t you be afeared o’ Me. I’ll not mind. But, lad,’ He’d say, ‘when I wants my way I just got t’ have it. Don’t you forget that. Don’t you go thinkin’ you can have your way afore I has Mine. You just trust Me t’ do what’s right. I know My business. I’m used t’ running worlds. I’m wonderful sorry,’ He’d say, ‘t’ have t’ make you feel bad; but they’s times, b‘y,’ He’d say, ‘when I really got t’ have My way.’ Oh, no,” Skipper Tommy concluded, “the Lard wouldn’t mind a poor man’s tryin’ t’ make a book like that! An’ I thinks I’ll just have t’ try.”

“Sure, Skipper Tommy,” said I, “I’ll help you.”

Skipper Tommy stared at me in great amaze.

“Ay,” said my mother, “Davy has learned to write.”

“That I have,” I boasted; “an’ I’ll help you make that book.”

“’Tis the same,” cried Skipper Tommy, slapping his thigh “as if ’twas writ already!”

After a long time, my mother spoke. “You’re always wanting to do some good thing, Skipper Tommy, are you not?” said she.47

“Well,” he admitted, his face falling, “I thinks and wonders a deal, ’tis true, but somehow I don’t seem t’——”

“Ay?” my father asked.

“Get—nowhere—much!”

Very true: but, even then, there was a man on the way to help him.

In the dead of winter, great storms of wind and snow raged for days together, so that it was unsafe to venture ten fathoms from the door, and the glass fell to fifty degrees (and more) below zero, where the liquid behaved in a fashion so sluggish that ’twould not have surprised us had it withdrawn into the bulb altogether, never to reappear in a sphere of agreeable activity. By night and day we kept the fires roaring (my father and Skipper Tommy standing watch and watch in the night) and might have gone at ease, cold as it was, had we not been haunted by the fear that a conflagration, despite our watchfulness, would of a sudden put us at the mercy of the weather, which would have made an end of us, every one, in a night. But when the skipper had wrought us into a cheerful mood, the wild, white days sped swift enough—so fast, indeed, that it was quite beyond me to keep count of them: for he was marvellous at devising adventures out-of-doors and pastimes within. At length, however, he said that he must be off to the Lodge, else Jacky and Timmie,49 the twins, who had been left to fend for themselves, would expire of longing for his return.

“An’ I’ll be takin’ Davy back with me, mum,” said he to my mother, not daring, however, to meet her eye to eye with the proposal, “for the twins is wantin’ him sore.”

“Davy!” cried my mother. “Surely, Skipper Tommy, you’re not thinking to have Davy back with you!”

Skipper Tommy ventured to maintain that I would be the better of a run in the woods, which would (as he ingeniously intimated) restore the blood to my cheeks: whereupon my mother came at once to his way of thinking, and would hear of no delay, but said—and that in a fever of anxiety—that I must be off in the morning, for she would not rest until I was put in the way of having healthful sport with lads of my age. So, that night, my sister made up three weeks’ rations for me from our store (with something extra in the way of tinned beef and a pot of jam as a gift from me to the twins); also, she mended my sleeping-bag, in which my sprouting legs had kicked a hole, and got out the big black wolfskin, for bed covering in case of need. And by the first light of the next day we loaded the komatik, harnessed the joyful dogs and set out with a rush, the skipper’s long whip cracking a jolly farewell as50 we went swinging over the frozen harbour to the Arm.

“Hi, hi, b’y!” the skipper shouted to the dogs.

Crack! went the whip, high over the heads of the pack. The dogs yelped. “Hi, hi!” screamed I. And on we sped, raising a dust of crisp snow in our wake. It was a famous pack. Fox, the new leader, was a mighty, indomitable fellow, and old Wolf, in the rear, had a sharp eye for lagging heels, which he snapped, in a flash, whenever a trace was let slack. What with Fox and Wolf and the skipper’s long whip and my cries of encouragement there was no let up. On we went, coursing over the level stretches, bumping over rough places, swerving ’round the turns. It was a glorious ride. The day was clear, the air frosty, the pace exhilarating. The blood tingled in every part of me. I was sorry when we rounded Pipestem Point, and the huddled tilts of the Lodge, half buried in snow, came into view. But, half an hour later, in Skipper Tommy’s tilt, I was glad that the distance had been no greater, for then the twins were helping me thaw out my cheeks and the tip of my nose, which had been frozen on the way.

That night the twins and I slept together in the cock-loft like a litter of puppies.

“Beef!” sighed Jacky, the last thing before falling asleep. “Think o’ that, Timmie!”51

“An’ jam!” said Timmie.

They gave me a nudge to waken me. “Thanks, Davy,” said they both.

Then I fell asleep.

Our folk slept a great deal at the Lodge. They seemed to want to have the winter pass without knowing more than they could help of the various pangs of it—like the bears. But, when the weather permitted them to stir without, they trapped for fox and lynx, and hunted (to small purpose) with antiquated guns, and cut wood, if they were in the humour; and whatever necessity compelled them to do, and whatever they had to eat (since there was at least enough of it), they managed to have a rollicking time of it, as you would not suppose, without being told. The tilts were built of slim logs, caulked with moss; and there was but one room—and that a bare one—with bunks at one end for the women and a cock-loft above for the men. The stove was kept at red heat, day and night, but, notwithstanding, there was half an inch of frost on the walls and great icicles under the bunks: extremes of temperature were thus to be found within a very narrow compass. In the evening, when we were all gathered close about the stove, we passed the jolliest hours; for it was then that the folk came in, and tales were told, and (what52 was even more to our taste) the “spurts at religion” occurred.

When the argument concerned the pains of hell, Mary, Tom Tot’s daughter, who was already bound out to service to the new manager of the store at Wayfarer’s Tickle (expected by the first mail-boat), would slip softly in to listen.

“What you thinkin’ about?” I whispered, once.

She sat remote from the company, biting her finger nails, staring, meanwhile, from speaker to speaker, with eyes that were pitifully eager.

“Hell,” she answered.

I was taken aback by that. “Hell, Mary?” I exclaimed.

“Ay, Davy,” she said, with a shudder, “I’m thinkin’ about hell.”

“What for?” said I. “Sure, ’twill do you no good to think about hell.”

“I got to,” said she. “I’m goin’ there!”

Skipper Tommy explained, when the folk had gone, that Mary, being once in a south port of our coast, had chanced to hear a travelling parson preach a sermon. “An’,” said he, “’tis too bad that young man preached about damnation, for ’tis the only sermon she ever heared, an’ she isn’t seemin’ t’ get over it.” After that I tried to persuade Mary that she would not go to hell, but quite dismally failed—and53 not only failed, but was soon thinking that I, too, was bound that way. When I expressed this fear, Mary took a great fancy to me, and set me to getting from Skipper Tommy a description of the particular tortures, as he conceived they were to be inflicted; for, said she, he was a holy man, and could tell what she so much wished to know. Skipper Tommy took me on his knee, and spoke long and tenderly to me, so that I have never since feared death or hell; but his words, being repeated, had no effect upon Mary, who continued still to believe that the unhappy fate awaited her, because of some sin she was predestined to commit, or, if not that, because of her weight of original sin.

“Oh, Davy, I got t’ go!” she moaned, tearing one of her nails to the quick.

“No, no!” I cried. “The Lard ’ll never be so mean t’ you.”

“You don’t know Him,” she said, mysteriously. “You don’t know what He’s up to.”

“Bother Him!” I exclaimed, angered that mortals should thus be made miserable by interference. “I wisht He’d leave us be!”

“Hush!” she said, horrified.

“What’s He gone an’ done, now?” I demanded.

“He’ve not elected me,” she whispered, solemnly. “He’ve left me with the goats.”54

And so, happily, I accumulated another grudge against this misconception of the dear Lord, which Skipper Tommy’s sweet philosophy and the jolly companionship of the twins could not eliminate for many days. But eventually the fresh air and laughter and tenderness restored my complacency. I forgot all about hell; ’twas more interesting to don my racquets and make the round of the fox traps with the twins, or to play pranks on the neighbours, or to fashion curious masques and go mummering from tilt to tilt. In the end, I emerged from the unfortunate mood with one firm conviction, founded largely, I fear, upon a picture which hung by my bed at home: that portraying a rising from the dead, the grave below, a golden, cloudy heaven above, wherefrom a winged angel had descended to take the hand of the free, enraptured soul. And my conviction was this, that, come what might to the souls of the wicked, the souls of the good were upon death robed in white and borne aloft to some great bliss, yet lingered, by the way, to throw back a tender glance.

I had never seen death come.

In three weeks my rations were exhausted, and, since it would have been ungenerous in me to consume Skipper Tommy’s food, I had the old man harness the dogs and take me home. My only regret55 was that my food did not last until Skipper Tommy had managed to make Tom Tot laugh. Many a night the old man had tried to no purpose, for Tom Tot would stare him stolidly in the eye, however preposterous the tale to be told. The twins and I had waited in vain—ready to explode at the right moment: but never having the opportunity. The last assault on Tom Tot’s composure had been disastrous to the skipper. When, with highly elaborate detail, he had once more described his plan for training whales, disclosing, at last, his intention of having a wheel-house on what he called the forward deck——

“What about the fo’c’s’le?” Tom Tot solemnly asked.

“Eh?” gasped the skipper. “Fo‘c’s’le?”

“Ay,” said Tom Tot, in a melancholy drawl. “Isn’t you give a thought t’ the crew?”

Skipper Tommy was nonplussed.

“Well,” sighed Tom, “I s’pose you’ll be havin’ t’ fit up Jonah’s quarters for them poor men!”

At home, in the evening, while my mother and father and sister and I were together in the glow of the fire, we delighted to plan the entertainment of the doctor who was coming to cure my mother. He must have the armchair from the best room below,56 my mother said, that he might sit in comfort, as all doctors should, while he felt her pulse; he must have a refreshing nip from the famous bottle of Jamaica rum, which had lain in untroubled seclusion since before I was born, waiting some occasion of vast importance; and he must surely not take her unaware in a slatternly moment, but must find her lying on the pillows, wearing her prettiest nightgown, which was thereupon newly washed and ironed and stowed away in the bottom drawer of the bureau against his unexpected coming. But while the snow melted from the hills, and the folk returned to the coast for the seal fishing, and the west winds carried the ice to sea, and we waited day by day for the mail-boat, our spirits fell, for my mother was then fast failing. And I discovered this strange circumstance: that while her strength withered, her hope grew large, and she loved to dwell upon the things she would do when the doctor had made her well; and I wondered why that was, but puzzled to no purpose.

It was in the dusk of a wet night of early June, with the sea in a tumble and the wind blowing fretfully from the west of north, that the mail-boat made our harbour. For three weeks we had kept watch for her, but in the end we were caught unready—the lookouts in from the Watchman, my father’s crew gone home, ourselves at evening prayer in the room where my mother lay abed. My father stopped dead in his petition when the first hoarse, muffled blast of the whistle came uncertain from the sea, and my own heart fluttered and stood still, until, rising above the rush of the wind and the noise of the rain upon the panes, the second blast broke the silence within. Then with a shaking cry of “Lord God, ’tis she!” my father leaped from his knees, ran for his sea-boots and oilskins, and shouted from below for my sister to make ready his lantern. But, indeed, he had to get his lantern for himself; for my mother, who was now in a flush of excitement, speaking high and incoherently, would have my sister stay with her to make ready for the coming of the doctor—to58 dress her hair, and tidy the room, and lay out the best coverlet, and help on with the dainty nightgown.

“Ay, mother,” my sister said, laughing, to quiet her, “I’ll not leave you. Sure, my father’s old enough t’ get his own lantern ready.”

“The doctor’s come!” I shouted, contributing a lad’s share to the excitement. “He’ve come! Hooray! He’ve come!”

“Quick, Bessie!” cried my mother. “He’ll be here before we know it. And my hair is in a fearful tangle. The looking-glass, lassie——”

I left them in the thick of this housewifely agitation. Donning my small oilskins, as best as I could without my kind sister’s help—and I shed impatient tears over the stiff button-holes, which my fingers would not manage—I stumbled down the path to the wharf, my exuberant joy escaping, the while, in loud halloos. There I learned that the mail-boat lay at anchor off the Gate, and, as it appeared, would not come in from the sea, but would presently be off to Wayfarer’s Tickle, to the north, where she would harbour for the night. The lanterns were shining cheerily in the dark of the wharf; and my father was speeding the men who were to take the great skiff out for the spring freight—barrels of flour and pork and the like—and roundly berating them, every one,59 in a way which surprised them into unwonted activity. Perceiving that my father’s temper and this mad bustle were to be kept clear of by wise lads, I slipped into my father’s punt, which lay waiting by the wharf-stairs; and there, when the skiff was at last got underway, I was found by my father and Skipper Tommy Lovejoy.

“Ashore with you, Davy, lad!” said my father. “There’ll be no room for the doctor. He’ll be wantin’ the stern seat for hisself.”

“Leave the boy bide where he is,” Skipper Tommy put in. “Sure, he’ll do no harm, an’—an’—why, zur,” as if that were sufficient, “he’s wantin’ t’ go!”

I kept silent—knowing well enough that Skipper Tommy was the man to help a lad to his desire.

“Ay,” said my father, “but I’m wantin’ the doctor t’ be comfortable when he comes ashore.”

“He’ll be comfortable enough, zur. The lad’ll sit in the bow an’ trim the boat. Pass the lantern t’ Davy, zur, an’ come aboard.”

My father continued to grumble his concern for the doctor’s comfort; but he leaned over to pat my shoulder while Skipper Tommy pushed off: for he loved his little son, did my big father—oh, ay, indeed, he did! We were soon past the lumbering skiff—and beyond Frothy Point—and out of the60 Gate—and in the open sea, where the wind was blowing smartly and the rain was flying in gusts. My father hailed the steamer’s small-boat, inbound with the mail, to know if the doctor was in verity aboard; and the answer, though but half caught, was such that they bent heartily to the oars, and the punt gave a great leap and went staggering through the big waves in a way to delight one’s very soul. Thus, in haste, we drew near the steamer, which lay tossing ponderously in the ground-swell, her engines panting, her lamps bright, her many lights shining from port-hole and deck—all so cozy and secure in the dirty night: so strange to our bleak coast!

At the head of the ladder the purser stood waiting to know about landing the freight.

“Is you goin’ on?” my father asked.

“Ay—t’ Wayfarer’s Tickle, when we load your skiff.”

“’Twill be alongside in a trice. But my wife’s sick. I’m wantin’ t’ take the doctor ashore.”

“He’s aft in the smokin’-room. You’d best speak t’ the captain first. Hold her? Oh, sure, he’ll hold her all night, for sickness!”

They moved off forward. Then Skipper Tommy took my hand—or, rather, I took his; for I was made ill at ease by the great, wet sweep of the deck, glistening with reflections of bright lights, and by the61 throng of strange men, and by the hiss of steam and the clank of iron coming from the mysterious depths below. He would show me the cabin, said he, where there was unexampled splendour to delight in; but when we came to a little house on the after deck, where men were lounging in a thick fog of tobacco smoke, I would go no further (though Skipper Tommy said that words were spoken not meet for the ears of lads to hear); for my interest was caught by a giant pup, which was not like the pups of our harbour but a lean, long-limbed, short-haired dog, with heavy jaws and sagging, blood-red eyelids. At a round table, whereon there lay a short dog-whip, his master sat at cards with a stout little man in a pea-jacket—a loose-lipped, blear-eyed, flabby little fellow, but, withal, hearty in his own way—and himself cut a curious figure, being grotesquely ill-featured and ill-fashioned, so that one rebelled against the sight of him.

A gust of rain beat viciously upon the windows and the wind ran swishing past.

“’Tis a dirty night,” said the dog’s master, shuffling nervously in his seat.

At this the dog lifted his head with a sharp snarl: whereupon, in a flash, the man struck him on the snout with the butt of the whip.

“That’s for you!” he growled.62

The dog regarded him sullenly—his upper lip still lifted from his teeth.

“Eh?” the man taunted. “Will you have another?”

The dog’s head subsided upon his paws; but his eyes never once left his master’s face—and the eyes were alert, steady, hard as steel.

“You’re l’arnin’,” the man drawled.

But the dog had learned no submission, but, if anything, only craft, as even I, a child, could perceive; and I marvelled that the man could conceive himself to be winning the mastery of that splendid brute. ’Twas no way to treat a dog of that disposition. It had been a wanton blow—taken with not so much as a whimper. Mastery? Hut! The beast was but biding his time. And I wished him well in the issue. “Ecod!” thought I, with heat. “I hopes he gets a good grip o’ the throat!” Whether or not, at the last, it was the throat, I do not know; but I do know the brutal tragedy of that man’s end, for, soon, he came rough-shod into our quiet life, and there came a time when I was hot on his trail, and rejoiced, deep in the wilderness, to see the snow all trampled and gory. But the telling of that is for a later page; the man had small part in the scene immediately approaching: it was another. When the wind and rain again beat angrily upon the ship,63 his look of triumph at once gave place to cowardly concern; and he repeated:

“’Tis a dirty night.”

“Ay,” said the other, and, frowning, spread his cards before him. “What do you make, Jagger?”

My father came in—and with him a breath of wet, cool air, which I caught with delight.

“Ha!” he cried, heartily, advancing upon the flabby little man, “we been waitin’ a long time for you, doctor. Thank God, you’ve come, at last!”

“Fifteen, two——” said the doctor.

My father started. “I’m wantin’ you t’ take a look at my poor wife,” he went on, renewing his heartiness with an effort. “She’ve been wonderful sick all winter, an’ we been waitin’——”

“Fifteen, four,” said the doctor; “fifteen, six——”

“Doctor,” my father said, touching the man on the shoulder, while Jagger smiled some faint amusement, “does you hear?”

It was suddenly very quiet in the cabin.

“Fifteen, eight——” said the doctor.

My father’s voice changed ominously. “Is you listenin’, zur?” he asked.

“Sick, is she?” said the doctor. “Fifteen, ten. I’ve got you, Jagger, sure ... ’Tis no fit night for a man to go ashore ... Fifteen, ten, did I say? and one for his nibs ... Go64 fetch her aboard, man ... And two for his heels——”

My father laid his hand over the doctor’s cards. “Was you sayin’,” he asked, “t’ fetch her aboard?”

“The doctor struck the hand away.

“Was you sayin’,” my father quietly persisted, “t’ fetch her aboard?”

I knew my father for a man of temper; and, now, I wondered that his patience lasted.

“Damme!” the doctor burst out. “Think I’m going ashore in this weather? If you want me to see her now, go fetch her aboard.”

My father coughed—then fingered the neck-band of his shirt.

“I wants t’ get this here clear in my mind,” he said, slowly. “Is you askin’ me t’ fetch that sick woman aboard this here ship?”

The doctor leaned over the table to spit.

“Has I got it right, zur?”

In the pause the spectators softly withdrew to the further end of the cabin.

“If he won’t fetch her aboard, Jagger,” said the doctor, turning to the dog’s master, “she’ll do very well, I’ll be bound, till we get back from the north. Eh, Jagger? If he cared very much, he’d fetch her aboard, wouldn’t he?”

Jagger laughed.65

“Ay, she’ll do very well,” the doctor repeated, now addressing my father, “till we get back. I’ll take a look at her then.”

I saw the color rush into my father’s face. Skipper Tommy laid a restraining hand on his shoulder.

“Easy, now, Skipper David!” he muttered.

“Is I right,” said my father, bending close to the doctor’s face, “in thinkin’ you says you won’t come ashore?”

The doctor shrugged his shoulders.

“Is I right,” pursued my father, his voice rising, “in thinkin’ the gov’ment pays you t’ tend the sick o’ this coast?”

“That’s my business,” flashed the doctor. “That’s my business, sir!”

Jagger looked upon my father’s angry face and smiled.

“Is we right, doctor,” said Skipper Tommy, “in thinkin’ you knows she lies desperate sick?”

“Damme!” cried the doctor. “I’ve heard that tale before. You’re a pretty set, you are, to try to play on a man’s feelings like that. But you can’t take me in. No, you can’t,” he repeated, his loose under-lip trembling. “You’re a pretty set, you are. But you can’t come it over me. Don’t you go blustering, now! You can’t come your bluster on me. Understand? You try any bluster on me, and,66 by heaven! I’ll let every man of your harbour die in his tracks. I’m the doctor, here, I want you to know. And I’ll not go ashore in weather like this.”

My father deliberately turned to wave Skipper Tommy and me out of the way: then laid a heavy hand on the doctor’s shoulder.

“You’ll not come?”

“Damned if I will!”

“By God!” roared my father. “I’ll take you!”

At once, the doctor sought to evade my father’s grasp, but could not, and, being unwise, struck him on the breast. My father felled him. The man lay in a flabby heap under the table, roaring lustily that he was being murdered; but so little sympathy did his plight extract, that, on the contrary, every man within happy reach, save Jagger and Skipper Tommy, gave him a hearty kick, taking no pains, it appeared, to choose the spot with mercy. As for Jagger, he had snatched up his whip, and was now raining blows on the muzzle of the dog, which had taken advantage of the uproar to fly at his legs. In this confusion, the Captain flung open the door and strode in. He was in a fuming rage; but, being no man to take sides in a quarrel, sought no explanation, but took my father by the arm and hurried him without, promising him redress, the while, at another67 time. Thus presently we found ourselves once more in my father’s punt, pushing out from the side of the steamer, which was already underway, chugging noisily.

“Hush, zur!” said Skipper Tommy to my father. “Curse him no more, zur. The good Lard, who made us, made him, also.”

My father cursed the harder.

“Stop,” cried the skipper, “or I’ll be cursin’ him, too, zur. God made that man, I tells you. He must have gone an’ made that man.”

“I hopes He’ll damn him, then,” said I.

“God knowed what He was doin’ when he made that man,” the skipper persisted, continuing in faith against his will. “I tells you I’ll not doubt His wisdom. He made that man ... He made that man ... He made that man....”

To this refrain we rowed into harbour.

We found my mother’s room made very neat, and very grand, too, I thought, with the shaded lamp and the great armchair from the best-room below; and my mother, now composed, but yet flushed with expectation, was raised on many snow-white pillows, lovely in the fine gown, with one thin hand, wherein she held a red geranium, lying placid on the coverlet.

“I am ready, David,” she said to my father.68

There was the sound of footsteps in the hall below. It was Skipper Tommy, as I knew.

“Is that he?” asked my mother. “Bring him up, David. I am quite ready.”

My father still stood silent and awkward by the door of the room.

“David,” said my poor mother, her voice breaking with sudden alarm, “have you been talking much with him? What has he told you, David? I’m not so very sick, am I?”

“Well, lass,” said my father, “’tis a great season for all sorts o’ sickness—an’ the doctor is sick abed hisself—an’ he—couldn’t—come.”

“Poor man!” sighed my mother. “But he’ll come ashore on the south’ard trip.”

“No, lass—no; I fear he’ll not.”

“Poor man!”

My mother turned her face from us. She trembled, once, and sighed, and then lay very quiet. I knew in my childish way that her hope had fled with ours—that, now, remote from our love and comfort-alone—all alone—she had been brought face to face with the last dread prospect. There was the noise of rain on the panes and wind without, and the heavy tread of Skipper Tommy’s feet, coming up the stair, but no other sound. But Skipper Tommy, entering now, moved a chair to my mother’s bedside, and laid69 a hand on hers, his old face illumined by his unfailing faith in the glory and wisdom of his God.

“Hush!” he said. “Don’t you go gettin’ scared lass. Don’t you go gettin’ scared at—the thing that’s comin’—t’ you. ’Tis nothin’ t’ fear,” he went on, gloriously confident. “’Tis not hard, I’m sure—the Lard’s too kind for that. He just lets us think it is, so He can give us a lovely surprise, when the time comes. Oh, no, ’tis not hard! ’Tis but like wakin’ up from a troubled dream. ’Tis like wakin’ t’ the sunlight of a new, clear day. Ah, ’tis a pity us all can’t wake with you t’ the beauty o’ the morning! But the dear Lard is kind. There comes an end t’ all the dreamin’. He takes our hand. ‘The day is broke,’ says He. ‘Dream no more, but rise, child o’ Mine, an’ come into the sunshine with Me.’ ’Tis only that that’s comin’ t’ you—only His gentle touch—an’ the waking. Hush! Don’t you go gettin’ scared. ’Tis a lovely thing—that’s comin’ t’ you!”

“I’m not afraid,” my mother whispered, turning. “I’m not afraid, Skipper Tommy. But I’m sad—oh I’m sad—to have to leave——”

She looked tenderly upon me.

My mother lay thus abandoned for seven days. It was very still and solemn in the room—and there was a hush in all the house; and there was a mystery, which even the break of day could not dissolve, and a shadow, which the streaming sunlight could not drive away. Beyond the broad window of her room, the hills of Skull Island and God’s Warning stood yellow in the spring sunshine, rivulets dripping from the ragged patches of snow which yet lingered in the hollows; and the harbour water rippled under balmy, fragrant winds from the wilderness; and workaday voices, strangely unchanged by the solemn change upon our days, came drifting up the hill from my father’s wharves; and, ay, indeed, all the world of sea and land was warm and wakeful and light of heart, just as it used to be. But within, where were the shadow and the mystery, we walked on tiptoe and spoke in whispers, lest we offend the spirit which had entered in.

By day my father was occupied with the men of71 the place, who were then anxiously fitting out for the fishing season, which had come of a sudden with the news of a fine sign at Battle Harbour. But my mother did not mind, but, rather, smiled, and was content to know that he was about his business—as men must be, whatever may come to pass in the house—and that he was useful to the folk of our harbour, whom she loved. And my dear sister—whose heart and hands God fashioned with kind purpose—gave full measure of tenderness for both; and my mother was grateful for that, as she ever was for my sister’s loving kindness to her and to me and to us all.

One night, being overwrought by sorrow, it may be, my father said that he would have the doctor-woman from Wolf Cove to help my mother.

“For,” said he, “I been thinkin’ a deal about she, o’ late, an’ they’s no tellin’ that she wouldn’t do you good.”

My mother raised her eyebrows. “The doctor-woman!” cried she. “Why, David!”

“Ay,” said my father, looking away, “I s’pose ’tis great folly in me t’ think it. But they isn’t no one else t’ turn to.”

And that was unanswerable.

“There seems to be no one else,” my mother admitted. “But, David—the doctor-woman?”

“They does work cures,” my father pursued. “I’m72 not knowin’ how they does; but they does, an’ that’s all I’m sayin’. Tim Budderly o’ the Arm told me—an’ ’twas but an hour ago—that she charmed un free o’ fits.”

“I have heard,” my mother mused, “that they work cures. And if——”

“They’s no knowin’ what she can do,” my father broke in, my mother now listening eagerly. “An’ I just wish you’d leave me go fetch her. Won’t you, lass? Come, now!”

“’Tis no use, David,” said my mother. “She couldn’t do anything—for me.”

“Ay, but,” my father persisted, “you’re forgettin’ that she’ve worked cures afore this. I’m fair believin’,” he added with conviction, “that they’s virtue in some o’ they charms. Not in many, maybe, but in some. An’ she might work a cure on you. I’m not sayin’ she will. I’m only sayin’ she might.”

My mother stared long at the white washed rafters overhead. “Oh,” she sighed, plucking at the coverlet, “if only she could!”

“She might,” said my father. “They’s no tellin’ till you’ve tried.”

“’Tis true, David,” my mother whispered, still fingering the coverlet. “God works in strange ways—and we’ve no one else in this land to help us—and, perhaps, He might——”73

My father was quick to press his advantage. “Ay,” he cried, “’tis very likely she’ll cure you.”

“David,” said my mother, tearing at the coverlet, “let us have her over to see me. She might do me good,” she ran on, eagerly. “She might at least tell me what I’m ailing of. She might stop the pain. She might even——”

“Hush!” my father interrupted, softly. “Don’t build on it, dear,” said he, who had himself, but a moment gone, been so eager and confident. “But we’ll try what she can do.”

“Ay, dear,” my mother whispered, in a voice grown very weak, “we’ll try.”

Skipper Tommy Lovejoy would have my father leave him fetch the woman from Wolf Cove, nor, to my father’s impatient surprise, would hear of any other; and he tipped me a happy wink—which had also a glint of mystery in it—when my father said that he might: whereby I knew that the old fellow was about the business of the book. And three days later, being on the lookout at the window of my mother’s room, I beheld the punt come back by way of North Tickle, Skipper Tommy labouring heavily at the oars, and the woman, squatted in the stern, serenely managing the sail to make the best of a capful of wind. I marvelled that the punt should74 make headway so poor in the quiet water—and that she should be so much by the stern—and that Skipper Tommy should be bent near double—until, by and by, the doctor-woman came waddling up the path, the skipper at her heels: whereupon I marvelled no more, for the reason was quite plain.

“Ecod! lad,” the skipper whispered, taking me aside, the while wiping the sweat from his red face with his hand; “but she’ll weigh five quintal if a pound! She’s e-nar-mous! ’Twould break your heart t’ pull that cargo from Wolf Cove. But I managed it, lad,” with a solemn wink, “for the good o’ the cause. Hist! now; but I found out a wonderful lot—about cures!”

Indeed, she was of a bulk most extraordinary; and she was rolling in fat, above and below, though it was springtime! ’Twas a wonder to me, with our folk not yet fattened by the more generous diet of the season, that she had managed to preserve her great double chin through the winter. It may be that this unfathomable circumstance first put me in awe of her; but I am inclined to think, after all, that it was her eyes, which were not like the eyes of our folk, but were brown—dog’s eyes, we call them on our coast, for we are a blue-eyed race—and upon occasion flashed like lightning. So much weight did she carry forward, too, that I fancied (and still75 believe) she would have toppled over had she not long ago learned to outwit nature in the matter of maintaining a balance. And an odd figure she cut, as you may be sure! For she was dressed somewhat in the fashion of men, with a cloth cap, rusty pea-jacket and sea-boots (the last, for some mysterious reason, being slit up the sides, as a brief skirt disclosed); and her grizzled hair was cut short, in the manner of men, but yet with some of the coquetry of women. In truth, as we soon found it was her boast that she was the equal of men, her complaint that the foolish way of the world (which she said had gone all askew) would not let her skipper a schooner, which, as she maintained in a deep bass voice, she was more capable of doing than most men.

“I make no doubt o’ that, mum,” said Skipper Tommy Lovejoy, to whom, in the kitchen, that night, she propounded her strange philosophy; “but you see, mum, ’tis the way o’ the world, an’ folks just will stick t’ their idees, an’, mum,” he went on, with a propitiating smile, “as you is only a woman, why——”

“Only a woman!” she roared, sitting up with a jerk. “Does you say——”

“Why, ay, mum!” Skipper Tommy put in, mildly. “You isn’t a man, is you?”76

She sat dumb and transfixed.

“Well, then,” said Skipper Tommy, in a mildly argumentative way, “’tis as I says. You must do as the women does, an’ not as a man might want to——”

“Mm-a-an!” she mocked, in a way that withered the poor skipper. “No, I isn’t a man! Was you hearin’ me say I was? Oh, you wasn’t, wasn’t you? An’ is you thinkin’ I’d be a man an I could? What!” she roared. “You isn’t sure about that, isn’t you? Oh, my! Isn’t you! Well, well! He isn’t sure,” appealing to me, with a shaking under lip. “Oh, my! There’s a man—he’s a man for you—there’s a man—puttin’ a poor woman t’ scorn! Oh, my!” she wailed, bursting into tears, as all women will, when put to the need of it. “Oh, dear!”

Skipper Tommy was vastly concerned for her. “My poor woman,” he began, “don’t you be cryin’, now. Come, now——”

“Oh, his poor woman,” she interrupted, bitingly. “His poor woman! Oh, my! An’ I s’pose you thinks ’tis the poor woman’s place t’ work in the splittin’ stage an’ not on the deck of a fore-an’-after. You does, does you? Ay, ’tis what I s’posed!” she said, with scorn. “An’ if you married me,” she continued, transfixing the terrified skipper with a fat forefinger, “I s’pose you’d be wantin’ me t’ split the fish77 you cotched. Oh, you would, would you? Oh, my! But I’ll have you t’ know, Skipper Thomas Lovejoy,” with a sudden and alarming change of voice, “that I’ve the makin’s of a better ship’s-master than you. An’ by the Lord Harry! I’m a better man,” saying which, she leaped from her chair with surprising agility, and began to roll up her sleeves, “an’ I’ll prove it on your wisage! Come on with you!” she cried, striking a belligerent attitude, her fists waving in a fashion most terrifying. “Come on an you dare!”

Skipper Tommy dodged behind the table in great haste and horror.

“Oh, dear!” cried she. “He won’t! Oh, my! There’s a man for you. An’ I’m but a woman, is I. His poor woman. Oh, his woman! Look you here, Skipper Thomas Lovejoy, you been stickin’ wonderful close alongside o’ me since you come t’ Wolf Cove, an’ I’m not quite knowin’ what tricks you’ve in mind. But I’m thinkin’ you’re like all the men, an’ I’ll have you t’ know this, that if ’tis marriage with me you’re thinkin’ on——”

But Skipper Tommy gasped and wildly fled.

“Ha!” she snorted, triumphantly. “I was thinkin’ I was a better man than he!”

“’Tis a shame,” said I, “t’ scare un so!”

Whereat, without uttering a sound, she laughed78 until the china clinked and rattled on the shelves, and I thought the pots and pans would come clattering from their places. And then she strutted the floor for all the world like a rooster once I saw in the South.