The Project Gutenberg EBook of Deeds that Won the Empire, by W. H. Fitchett

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Deeds that Won the Empire

Historic Battle Scenes

Author: W. H. Fitchett

Release Date: September 12, 2006 [EBook #19255]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEEDS THAT WON THE EMPIRE ***

Produced by Al Haines

FIRST EDITION (Smith, Elder & Co.) . . . November 1897

Twenty-ninth Impression . . . . . . . . . . . . . . October 1914

Reprinted (John Murray) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . September 1917

Reprinted . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . February 1921

The tales here told are written, not to glorify war, but to nourish patriotism. They represent an effort to renew in popular memory the great traditions of the Imperial race to which we belong.

The history of the Empire of which we are subjects—the story of the struggles and sufferings by which it has been built up—is the best legacy which the past has bequeathed to us. But it is a treasure strangely neglected. The State makes primary education its anxious care, yet it does not make its own history a vital part of that education. There is real danger that for the average youth the great names of British story may become meaningless sounds, that his imagination will take no colour from the rich and deep tints of history. And what a pallid, cold-blooded citizenship this must produce!

War belongs, no doubt, to an imperfect stage of society; it has a side of pure brutality. But it is not all brutal. Wordsworth's daring line about "God's most perfect instrument" has a great truth behind it. What examples are to be found in the tales here retold, not merely of heroic daring, but of even finer qualities—of heroic fortitude; of loyalty to duty stronger than the love of life; of the temper which dreads dishonour more than it fears death; of the patriotism which makes love of the Fatherland a passion. These are the elements of robust citizenship. They represent some, at least, of the qualities by which the Empire, in a sterner time than ours, was won, and by which, in even these ease-loving days, it must be maintained.

These sketches appeared originally in the Melbourne Argus, and are republished by the kind consent of its proprietors. Each sketch is complete in itself; and though no formal quotation of authorities is given, yet all the available literature on each event described has been laid under contribution. The sketches will be found to be historically accurate.

THE FIGHT OFF CAPE ST. VINCENT

THE FIRE-SHIPS IN THE BASQUE ROADS

THE MAN WHO SPOILED NAPOLEON'S "DESTINY"

THE BLOOD-STAINED HILL OF BUSACO

THE "SHANNON" AND THE "CHESAPEAKE"

THE GREAT BREACH OF CIUDAD RODRIGO

HOW THE "HERMIONE" WAS RECAPTURED

FRENCH AND ENGLISH IN THE PASSES

FAMOUS CUTTING-OUT EXPEDITIONS

THE BLOODIEST FIGHT IN THE PENINSULA

II. Hougoumont

III. Picton and D'Erlon

VII. The Old Guard

VIII. The Great Defeat

TRAFALGAR—

I. The Strategy

THE SCEPTRE OF THE SEA.

"Old England's sons are English yet,

Old England's hearts are strong;

And still she wears her coronet

Aflame with sword and song.

As in their pride our fathers died,

If need be, so die we;

So wield we still, gainsay who will,

The sceptre of the sea.

We've Raleighs still for Raleigh's part,

We've Nelsons yet unknown;

The pulses of the Lion-Heart

Beat on through Wellington.

Hold, Britain, hold thy creed of old,

Strong foe and steadfast friend,

And still unto thy motto true,

'Defy not, but defend.'

Men whisper that our arm is weak,

Men say our blood is cold,

And that our hearts no longer speak

That clarion note of old;

But let the spear and sword draw near

The sleeping lion's den,

Our island shore shall start once more

To life, with armèd men."

—HERMAN CHARLES MERIVALE.

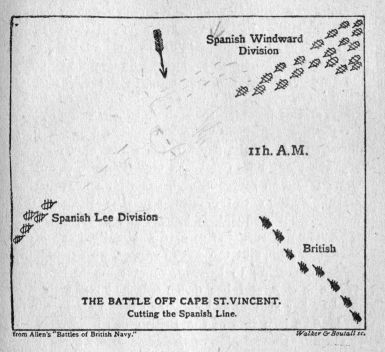

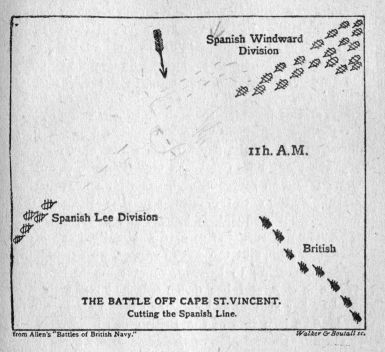

On the night of February 13, 1797, an English fleet of fifteen ships of the line, in close order and in readiness for instant battle, was under easy sail off Cape St. Vincent. It was a moonless night, black with haze, and the great ships moved in silence like gigantic spectres over the sea. Every now and again there came floating from the south-east the dull sound of a far-off gun. It was the grand fleet of Spain, consisting of twenty-seven ships of line, under Admiral Don Josef de Cordova; one great ship calling to another through the night, little dreaming that the sound of their guns was so keenly noted by the eager but silent fleet of their enemies to leeward. The morning of the 14th—a day famous in the naval history of the empire—broke dim and hazy; grey sea, grey fog, grey dawn, making all things strangely obscure. At half-past six, however, the keen-sighted British outlooks caught a glimpse of the huge straggling line of Spaniards, stretching apparently through miles of sea haze. "They are thumpers!" as the signal lieutenant of the Barfleur reported with emphasis to his captain; "they loom like Beachy Head in a fog!" The Spanish fleet was, indeed, the mightiest ever sent from Spanish ports since "that great fleet invincible" of 1588 carried into the English waters—but not out of them!—

"The richest spoils of Mexico, the stoutest hearts of Spain."

The Admiral's flag was borne by the Santissima Trinidad, a floating mountain, the largest ship at that time on the sea, and carrying on her four decks 130 guns. Next came six three-deckers carrying 112 guns each, two ships of the line of 80 guns each, and seventeen carrying 74 guns, with no less than twelve 34-gun frigates to act as a flying cordon of skirmishers. Spain had joined France against England on September 12, 1796, and Don Cordova, at the head of this immense fleet, had sailed from Cadiz to execute a daring and splendid strategy. He was to pick up the Toulon fleet, brush away the English squadron blockading Brest, add the great French fleet lying imprisoned there to his forces, and enter the British Channel with above a hundred sail of the line under his flag, and sweep in triumph to the mouth of the Thames! If the plan succeeded, Portugal would fall, a descent was to be made on Ireland; the British flag, it was reckoned, would be swept from the seas.

Sir John Jervis was lying in the track of the Spaniards to defeat this ingenious plan. Five ships of the line had been withdrawn from the squadron blockading Brest to strengthen him; still he had only fifteen ships against the twenty-seven huge Spaniards in front of him; whilst, if the French Toulon fleet behind him broke out, he ran the risk of being crushed, so to speak, betwixt the upper and the nether millstone. Never, perhaps, was the naval supremacy of England challenged so boldly and with such a prospect of success as at this moment. The northern powers had coalesced under Russia, and only a few weeks later the English guns were thundering over the roofs of Copenhagen, while the united flags of France and Spain were preparing to sweep through the narrow seas. The "splendid isolation" of to-day is no novelty. In 1796, as it threatened to be in 1896, Great Britain stood singly against a world in arms, and it is scarcely too much to say that her fate hung on the fortunes of the fleet that, in the grey dawn of St. Valentine's Day, a hundred years ago, was searching the skyline for the topmasts of Don Cordova's huge three-deckers.

Fifteen to twenty-seven is enormous odds, but, on the testimony of Nelson himself, a better fleet never carried the fortunes of a great country than that under Sir John Jervis. The mere names of the ships or of their commanders awaken more sonorous echoes than the famous catalogue of the ships in the "Iliad." Trowbridge, in the Culloden, led the van; the line was formed of such ships as the Victory, the flagship, the Barfleur, the Blenheim, the Captain, with Nelson as commodore, the Excellent, under Collingwood, the Colossus, under Murray, the Orion, under Sir James Saumarez, &c. Finer sailors and more daring leaders never bore down upon an enemy's fleet. The picture offered by the two fleets in the cold haze of that fateful morning, as a matter of fact, reflected the difference in their fighting and sea-going qualities. The Spanish fleet, a line of monsters, straggled, formless and shapeless, over miles of sea space, distracted with signals, fluttering with many-coloured flags. The English fleet, grim and silent, bore down upon the enemy in two compact and firm-drawn columns, ship following ship so closely and so exactly that bowsprit and stern almost touched, while an air-line drawn from the foremast of the leading ship to the mizzenmast of the last ship in each column would have touched almost every mast betwixt. Stately, measured, threatening, in perfect fighting order, the compact line of the British bore down on the Spaniards.

Nothing is more striking in the battle of St. Vincent than the swift and resolute fashion in which Sir John Jervis leaped, so to speak, at his enemy's throat, with the silent but deadly leap of a bulldog. As the fog lifted, about nine o'clock, with the suddenness and dramatic effect of the lifting of a curtain in a great theatre, it revealed to the British admiral a great opportunity. The weather division of the Spanish fleet, twenty-one gigantic ships, resembled nothing so much as a confused and swaying forest of masts; the leeward division—six ships in a cluster, almost as confused—was parted by an interval of nearly three miles from the main body of the fleet, and into that fatal gap, as with the swift and deadly thrust of a rapier, Jervis drove his fleet in one unswerving line, the two columns melting into one, ship following hard on ship. The Spaniards strove furiously to close their line, the twenty-one huge ships bearing down from the windward, the smaller squadron clawing desperately up from the leeward. But the British fleet—a long line of gliding pyramids of sails, leaning over to the pressure of the wind, with "the meteor flag" flying from the peak of each vessel, and the curving lines of guns awaiting grim and silent beneath—was too swift. As it swept through the gap, the Spanish vice-admiral, in the Principe de Asturias, a great three-decker of 112 guns, tried the daring feat of breaking through the British line to join the severed squadron. He struck the English fleet almost exactly at the flagship, the Victory. The Victory was thrown into stays to meet her, the Spaniard swung round in response, and, exactly as her quarter was exposed to the broadside of the Victory, the thunder of a tremendous broadside rolled from that ship. The unfortunate Spaniard was smitten as with a tempest of iron, and the next moment, with sails torn, topmasts hanging to leeward, ropes hanging loose in every direction, and her decks splashed red with the blood of her slaughtered crew, she broke off to windward. The iron line of the British was unpierceable! The leading three-decker of the Spanish lee division in like manner bore up, as though to break through the British line to join her admiral; but the grim succession of three-deckers, following swift on each other like the links of a moving iron chain, was too disquieting a prospect to be faced. It was not in Spanish seamanship, or, for the matter of that, in Spanish flesh and blood, to beat up in the teeth of such threatening lines of iron lips. The Spanish ships swung sullenly back to leeward, and the fleet of Don Cordova was cloven in twain, as though by the stroke of some gigantic sword-blade.

As soon as Sir John Jervis saw the steady line of his fleet drawn fair across the gap in the Spanish line, he flung his leading ships up to windward on the mass of the Spanish fleet, by this time beating up to windward. The Culloden led, thrust itself betwixt the hindmost Spanish three-deckers, and broke into flame and thunder on either side. Six minutes after her came the Blenheim; then, in quick succession, the Prince George, the Orion, the Colossus. It was a crash of swaying masts and bellying sails, while below rose the shouting of the crews, and, like the thrusts of fiery swords, the flames shot out from the sides of the great three-deckers against each other, and over all rolled the thunder and the smoke of a Titanic sea-fight. Nothing more murderous than close fighting betwixt the huge wooden ships of those days can well be imagined. The Victory, the largest British ship present in the action, was only 186 feet long and 52 feet broad; yet in that little area 1000 men fought, 100 great guns thundered. A Spanish ship like the San Josef was 194 feet in length and 54 feet in breadth; but in that area 112 guns were mounted, while the three decks were thronged with some 1300 men. When floating batteries like these swept each other with the flame of swiftly repeated broadsides at a distance of a few score yards, the destruction may be better imagined than described. The Spanish had an advantage in the number of guns and men, but the British established an instant mastery by their silent discipline, their perfect seamanship, and the speed with which their guns were worked. They fired at least three broadsides to every two the Spaniards discharged, and their fire had a deadly precision compared with which that of the Spaniards was mere distracted spluttering.

Meanwhile the dramatic crisis of the battle came swiftly on. The Spanish admiral was resolute to join the severed fragments of his fleet. The Culloden, the Blenheim, the Prince George, and the Orion were thundering amongst his rearmost ships, and as the British line swept up, each ship tacked as it crossed the gap in the Spanish line, bore up to windward and added the thunder of its guns to the storm of battle raging amongst the hindmost Spaniards. But naturally the section of the British line that had not yet passed the gap shortened with every minute, and the leading Spanish ships at last saw the sea to their leeward clear of the enemy, and the track open to their own lee squadron. Instantly they swung round to leeward, the great four-decker, the flagship, with a company of sister giants, the San Josef and the Salvador del Mundo, of 112 guns each, the San Nicolas, and three other great ships of 80 guns. It was a bold and clever stroke. This great squadron, with the breeze behind it, had but to sweep past the rear of the British line, join the lee squadron, and bear up, and the Spanish fleet in one unbroken mass would confront the enemy. The rear of the British line was held by Collingwood in the Excellent; next to him came the Diadem; the third ship was the Captain, under Nelson. We may imagine how Nelson's solitary eye was fixed on the great Spanish three-deckers that formed the Spanish van as they suddenly swung round and came sweeping down to cross his stern. Not Napoleon himself had a vision more swift and keen for the changing physiognomy of a great battle than Nelson, and he met the Spanish admiral with a counter-stroke as brilliant and daring as can be found in the whole history of naval warfare. The British fleet saw the Captain suddenly swing out of line to leeward—in the direction from the Spanish line, that is—but with swift curve the Captain doubled back, shot between the two English ships that formed the rear of the line, and bore up straight in the path of the Spanish flagship, with its four decks, and the huge battleships on either side of it.

The Captain, it should be remembered, was the smallest 74 in the British fleet, and as the great Spanish ships closed round her and broke into flame it seemed as if each one of them was big enough to hoist the Captain on board like a jolly-boat. Nelson's act was like that of a single stockman who undertakes to "head off" a drove of angry bulls as they break away from the herd; but the "bulls" in this case were a group of the mightiest battleships then afloat. Nelson's sudden movement was a breach of orders; it left a gap in the British line; to dash unsupported into the Spanish van seemed mere madness, and the spectacle, as the Captain opened fire on the huge Santissima Trinidad, was simply amazing. Nelson was in action at once with the flagship of 130 guns, two ships of 112 guns, one of 80 guns, and two of 74 guns! To the spectators who watched the sight the sides of the Captain seemed to throb with quick-following pulses of flame as its crew poured their shot into the huge hulks on every side of them. The Spaniards formed a mass so tangled that they could scarcely fire at the little Captain without injuring each other; yet the English ship seemed to shrivel beneath even the imperfect fire that did reach her. Her foremast was shot away, her wheel-post shattered, her rigging torn, some of her guns dismantled, and the ship was practically incapable of further service either in the line or in chase. But Nelson had accomplished his purpose: he had stopped the rush of the Spanish van.

At this moment the Excellent, under Collingwood, swept into the storm of battle that raged round the Captain, and poured three tremendous broadsides into the Spanish three-decker the Salvador del Mundo that practically disabled her. "We were not further from her," the domestic but hard-fighting Collingwood wrote to his wife, "than the length of our garden." Then, with a fine feat of seamanship, the Excellent passed between the Captain and the San Nicolas, scourging that unfortunate ship with flame at a distance of ten yards, and then passed on to bestow its favours on the Santissima Trinidad—"such a ship," Collingwood afterwards confided to his wife, "as I never saw before!" Collingwood tormented that monster with his fire so vehemently that she actually struck, though possession of her was not taken before the other Spanish ships, coming up, rescued her, and she survived to carry the Spanish flag in the great fight of Trafalgar.

Meanwhile the crippled Captain, though actually disabled, had performed one of the most dramatic and brilliant feats in the history of naval warfare. Nelson put his helm to starboard, and ran, or rather drifted, on the quarter-gallery of the San Nicolas, and at once boarded that leviathan. Nelson himself crept through the quarter-gallery window in the stern of the Spaniard, and found himself in the officers' cabins. The officers tried to show fight, but there was no denying the boarders who followed Nelson, and with shout and oath, with flash of pistol and ring of steel, the party swept through on to the main deck. But the San Nicolas had been boarded also at other points. "The first man who jumped into the enemy's mizzen-chains," says Nelson, "was the first lieutenant of the ship, afterwards Captain Berry." The English sailors dropped from their spritsail yard on to the Spaniard's deck, and by the time Nelson reached the poop of the San Nicolas he found his lieutenant in the act of hauling down the Spanish flag. Nelson proceeded to collect the swords of the Spanish officers, when a fire was opened upon them from the stern gallery of the admiral's ship, the San Josef, of 112 guns, whose sides were grinding against those of the San Nicolas. What could Nelson do? To keep his prize he must assault a still bigger ship. Of course he never hesitated! He flung his boarders up the side of the huge San Josef, but he himself had to be assisted to climb the main chains of that vessel, his lieutenant this time dutifully assisting his commodore up instead of indecorously going ahead of him. "At this moment," as Nelson records the incident, "a Spanish officer looked over the quarterdeck rail and said they surrendered. It was not long before I was on the quarter-deck, where the Spanish captain, with a bow, presented me his sword, and said the admiral was dying of his wounds. I asked him, on his honour, if the ship was surrendered. He declared she was; on which I gave him my hand, and desired him to call on his officers and ship's company and tell them of it, which he did; and on the quarterdeck of a Spanish first-rate—extravagant as the story may seem—did I receive the swords of vanquished Spaniards, which, as I received, I gave to William Fearney, one of my bargemen, who put them with the greatest sang-froid under his arm," a circle of "old Agamemnons," with smoke-blackened faces, looking on in grim approval.

This is the story of how a British fleet of fifteen vessels defeated a Spanish fleet of twenty-seven, and captured four of their finest ships. It is the story, too, of how a single English ship, the smallest 74 in the fleet—but made unconquerable by the presence of Nelson—stayed the advance of a whole squadron of Spanish three-deckers, and took two ships, each bigger than itself, by boarding. Was there ever a finer deed wrought under "the meteor flag"! Nelson disobeyed orders by leaving the English line and flinging himself on the van of the Spaniards, but he saved the battle. Calder, Jervis's captain, complained to the admiral that Nelson had "disobeyed orders." "He certainly did," answered Jervis; "and if ever you commit such a breach of your orders I will forgive you also."

"Sound, sound the clarion, fill the fife!

To all the sensual world proclaim,

One crowded hour of glorious life

Is worth an age without a name."

—SIR WALTER SCOTT.

The year 1759 is a golden one in British history. A great French army that threatened Hanover was overthrown at Minden, chiefly by the heroic stupidity of six British regiments, who, mistaking their orders, charged the entire French cavalry in line, and destroyed them. "I have seen," said the astonished French general, "what I never thought to be possible—a single line of infantry break through three lines of cavalry ranked in order of battle, and tumble them into ruin!" Contades omitted to add that this astonishing infantry, charging cavalry in open formation, was scourged during their entire advance by powerful batteries on their flank. At Quiberon, in the same year, Hawke, amid a tempest, destroyed a mighty fleet that threatened England with invasion; and on the heights of Abraham, Wolfe broke the French power in America. "We are forced," said Horace Walpole, the wit of his day, "to ask every morning what new victory there is, for fear of missing one." Yet, of all the great deeds of that annus mirabilis, the victory which overthrew Montcalm and gave Quebec to England—a victory achieved by the genius of Pitt and the daring of Wolfe—was, if not the most shining in quality, the most far-reaching in its results. "With the triumph of Wolfe on the heights of Abraham," says Green, "began the history of the United States."

The hero of that historic fight wore a singularly unheroic aspect. Wolfe's face, in the famous picture by West, resembles that of a nervous and sentimental boy—he was an adjutant at sixteen, and only thirty-three when he fell, mortally wounded, under the walls of Quebec. His forehead and chin receded; his nose, tip-tilted heavenwards, formed with his other features the point of an obtuse triangle. His hair was fiery red, his shoulders narrow, his legs a pair of attenuated spindle-shanks; he was a chronic invalid. But between his fiery poll and his plebeian and upturned nose flashed a pair of eyes—keen, piercing, and steady—worthy of Caesar or of Napoleon. In warlike genius he was on land as Nelson was on sea, chivalrous, fiery, intense. A "magnetic" man, with a strange gift of impressing himself on the imagination of his soldiers, and of so penetrating the whole force he commanded with his own spirit that in his hands it became a terrible and almost resistless instrument of war. The gift for choosing fit agents is one of the highest qualities of genius; and it is a sign of Pitt's piercing insight into character that, for the great task of overthrowing the French power in Canada, he chose what seemed to commonplace vision a rickety, hypochondriacal, and very youthful colonel like Wolfe.

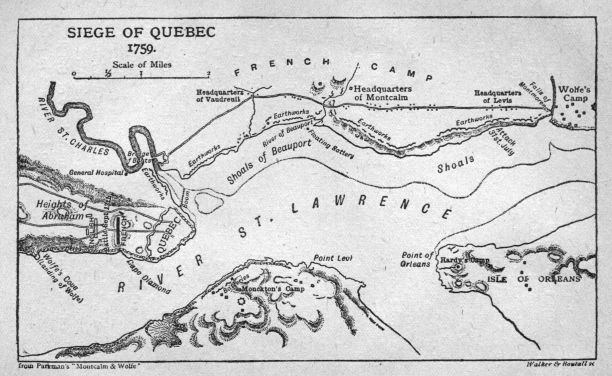

Pitt's strategy for the American campaign was spacious, not to say grandiose. A line of strong French posts, ranging from Duquesne, on the Ohio, to Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain, held the English settlements on the coast girdled, as in an iron band, from all extension westward; while Quebec, perched in almost impregnable strength on the frowning cliffs which look down on the St. Lawrence, was the centre of the French power in Canada. Pitt's plan was that Amherst, with 12,000 men, should capture Ticonderoga; Prideaux, with another powerful force, should carry Montreal; and Wolfe, with 7000 men, should invest Quebec, where Amherst and Prideaux were to join him. Two-thirds of this great plan broke down. Amherst and Prideaux, indeed, succeeded in their local operations, but neither was able to join Wolfe, who had to carry out with one army the task for which three were designed.

On June 21, 1759, the advanced squadron of the fleet conveying Wolfe came working up the St. Lawrence. To deceive the enemy they flew the white flag, and, as the eight great ships came abreast of the Island of Orleans, the good people of Quebec persuaded themselves it was a French fleet bringing supplies and reinforcements. The bells rang a welcome; flags waved. Boats put eagerly off to greet the approaching ships. But as these swung round at their anchorage the white flag of France disappeared, and the red ensign of Great Britain flew in its place. The crowds, struck suddenly dumb, watched the gleam of the hostile flag with chap-fallen faces. A priest, who was staring at the ships through a telescope, actually dropped dead with the excitement and passion created by the sight of the British fleet. On June 26 the main body of the fleet bringing Wolfe himself with 7000 troops, was in sight of the lofty cliffs on which Quebec stands; Cook, afterwards the famous navigator, master of the Mercury, sounding ahead of the fleet. Wolfe at once seized the Isle of Orleans, which shelters the basin of Quebec to the east, and divides the St. Lawrence into two branches, and, with a few officers, quickly stood on the western point of the isle. At a glance the desperate nature of the task committed to him was apparent.

Quebec stands on the rocky nose of a promontory, shaped roughly like a bull's-head, looking eastward. The St. Lawrence flows eastward under the chin of the head; the St. Charles runs, so to speak, down its nose from the north to meet the St. Lawrence. The city itself stands on lofty cliffs, and as Wolfe looked upon it on that June evening far away, it was girt and crowned with batteries. The banks of the St. Lawrence, that define what we have called the throat of the bull, are precipitous and lofty, and seem by mere natural strength to defy attack, though it was just here, by an ant-like track up 250 feet of almost perpendicular cliff, Wolfe actually climbed to the plains of Abraham. To the east of Quebec is a curve of lofty shore, seven miles long, between the St. Charles and the Montmorenci. When Wolfe's eye followed those seven miles of curving shore, he saw the tents of a French army double his own in strength, and commanded by the most brilliant French soldier of his generation, Montcalm. Quebec, in a word, was a great natural fortress, attacked by 9000 troops and defended by 16,000; and if a daring military genius urged the English attack, a soldier as daring and well-nigh as able as Wolfe directed the French defence.

Montcalm gave a proof of his fine quality as a soldier within twenty-four hours of the appearance of the British fleet. The very afternoon the British ships dropped anchor a terrific tempest swept over the harbour, drove the transports from their moorings, dashed the great ships of war against each other, and wrought immense mischief. The tempest dropped as quickly as it had arisen. The night fell black and moonless. Towards midnight the British sentinels on the point of the Isle of Orleans saw drifting silently through the gloom the outlines of a cluster of ships. They were eight huge fire-ships, floating mines packed with explosives. The nerve of the French sailors, fortunately for the British, failed them, and they fired the ships too soon. But the spectacle of these flaming monsters as they drifted towards the British fleet was appalling. The river showed ebony-black under the white flames. The glare lit up the river cliffs, the roofs of the city, the tents of Montcalm, the slopes of the distant hills, the black hulls of the British ships. It was one of the most stupendous exhibitions of fireworks ever witnessed! But it was almost as harmless as a display of fireworks. The boats from the British fleet were by this time in the water, and pulling with steady daring to meet these drifting volcanoes. They were grappled, towed to the banks, and stranded, and there they spluttered and smoked and flamed till the white light of the dawn broke over them. The only mischief achieved by these fire-ships was to burn alive one of their own captains and five or six of his men, who failed to escape in their boats.

Wolfe, in addition to the Isle of Orleans, seized Point Levi, opposite the city, and this gave him complete command of the basin of Quebec; from his batteries on Point Levi, too, he could fire directly on the city, and destroy it if he could not capture it. He himself landed the main body of his troops on the east bank of the Montmorenci, Montcalm's position, strongly entrenched, being between him and the city. Between the two armies, however, ran the deep gorge through which the swift current of the Montmorenci rushes down to join the St. Lawrence. The gorge is barely a gunshot in width, but of stupendous depth. The Montmorenci tumbles over its rocky bed with a speed that turns the flashing waters almost to the whiteness of snow. Was there ever a more curious military position adopted by a great general in the face of superior forces! Wolfe's tiny army was distributed into three camps: his right wing on the Montmorenci was six miles distant from his left wing at Point Levi, and between the centre, on the Isle of Orleans, and the two wings, ran the two branches of the St. Lawrence. That Wolfe deliberately made such a distribution of his forces under the very eyes of Montcalm showed his amazing daring. And yet beyond firing across the Montmorenci on Montcalm's left wing, and bombarding the city from Point Levi, the British general could accomplish nothing. Montcalm knew that winter must compel Wolfe to retreat, and he remained stubbornly but warily on the defensive.

On July 18 the British performed a daring feat. In the darkness of the night two of the men-of-war and several sloops ran past the Quebec batteries and reached the river above the town; they destroyed some fireships they found there, and cut off Montcalm's communication by water with Montreal. This rendered it necessary for the French to establish guards on the line of precipices between Quebec and Cap-Rouge. On July 28 the French repeated the experiment of fire-ships on a still more gigantic scale. A vast fire-raft was constructed, composed of some seventy schooners, boats, and rafts, chained together, and loaded with combustibles and explosives. The fire-raft is described as being 100 fathoms in length, and its appearance, as it came drifting on the current, a mass of roaring fire, discharging every instant a shower of missiles, was terrifying. But the British sailors dashed down upon it, broke the huge raft into fragments, and towed them easily ashore. "Hang it, Jack," one sailor was heard to say to his mate as he tugged at the oar, "didst thee ever take hell in tow before?"

Time was on Montcalm's side, and unless Wolfe could draw him from his impregnable entrenchments and compel him to fight, the game was lost. When the tide fell, a stretch of shoal a few score yards wide was left bare on the French side of the Montmorenci. The slope that covered this was steep, slippery with grass, crowned by a great battery, and swept by the cross-fire of entrenchments on either flank. Montcalm, too, holding the interior lines, could bring to the defence of this point twice the force with which Wolfe could attack it. Yet to Wolfe's keen eyes this seemed the one vulnerable point in Montcalm's front, and on July 31 he made a desperate leap upon it.

The attack was planned with great art. The British batteries thundered across the Montmorenci, and a feint was made of fording that river higher up, so as to distract the attention of the French, whilst the boats of the fleet threatened a landing near Quebec itself. At half-past five the tide was at its lowest, and the boat-flotilla, swinging round at a signal, pulled at speed for the patch of muddy foreshore already selected. The Grenadiers and Royal Americans leaped ashore in the mud, and—waiting neither for orders, nor leaders, nor supports—dashed up the hill to storm the redoubt. They reached the first redoubt, tumbled over it and through it, only to find themselves breathless in a semi-circle of fire. The men fell fast, but yet struggled fiercely upwards. A furious storm of rain broke over the combatants at that moment, and made the steep grass-covered slope as slippery as mere glass. "We could not see half-way down the hill," writes the French officer in command of the battery on the summit. But through the smoke and the driving rain they could still see the Grenadiers and Royal Americans in ragged clusters, scarce able to stand, yet striving desperately to climb upwards. The reckless ardour of the Grenadiers had spoiled Wolfe's attack, the sudden storm helped to save the French, and Wolfe withdrew his broken but furious battalions, having lost some 500 of his best men and officers.

The exultant French regarded the siege as practically over; but Wolfe was a man of heroic and quenchless tenacity, and never so dangerous as when he seemed to be in the last straits. He held doggedly on, in spite of cold and tempest and disease. His own frail body broke down, and for the first time the shadow of depression fell on the British camps when they no longer saw the red head and lean and scraggy body of their general moving amongst them. For a week, between August 22 and August 29, he lay apparently a dying man, his face, with its curious angles, white with pain and haggard with disease. But he struggled out again, and framed yet new plans of attack. On September 10 the captains of the men-of-war held a council on board the flagship, and resolved that the approach of winter required the fleet to leave Quebec without delay. By this time, too, Wolfe's scanty force was diminished one-seventh by disease or losses in battle. Wolfe, however had now formed the plan which ultimately gave him success, though at the cost of his own life.

From a tiny little cove, now known as Wolfe's Cove, five miles to the west of Quebec, a path, scarcely accessible to a goat, climbs up the face of the great cliff, nearly 250 feet high. The place was so inaccessible that only a post of 100 men kept guard over it. Up that track, in the blackness of the night, Wolfe resolved to lead his army to the attack on Quebec! It needed the most exquisite combinations to bring the attacking force to that point from three separate quarters, in the gloom of night, at a given moment, and without a sound that could alarm the enemy. Wolfe withdrew his force from the Montmorenci, embarked them on board his ships, and made every sign of departure. Montcalm mistrusted these signs, and suspected Wolfe would make at least one more leap on Quebec before withdrawing. Yet he did not in the least suspect Wolfe's real designs. He discussed, in fact, the very plan Wolfe adopted, but dismissed it by saying, "We need not suppose that the enemy have wings." The British ships were kept moving up and down the river front for several days, so as to distract and perplex the enemy. On September 12 Wolfe's plans were complete, and he issued his final orders. One sentence in them curiously anticipates Nelson's famous signal at Trafalgar. "Officers and men," wrote Wolfe, "will remember what their country expects of them." A feint on Beauport, five miles to the east of Quebec, as evening fell, made Montcalm mass his troops there; but it was at a point five miles west of Quebec the real attack was directed.

At two o'clock at night two lanterns appeared for a minute in the maintop shrouds of the Sunderland. It was the signal, and from the fleet, from the Isle of Orleans, and from Point Levi, the English boats stole silently out, freighted with some 1700 troops, and converged towards the point in the black wall of cliffs agreed upon. Wolfe himself was in the leading boat of the flotilla. As the boats drifted silently through the darkness on that desperate adventure, Wolfe, to the officers about him, commenced to recite Gray's "Elegy":—

"The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,

And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave,

Await alike the inevitable hour.

The paths of glory lead but to the grave."

"Now, gentlemen," he added, "I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec." Wolfe, in fact, was half poet, half soldier. Suddenly from the great wall of rock and forest to their left broke the challenge of a French sentinel—"Qui vive?" A Highland officer of Fraser's regiment, who spoke French fluently, answered the challenge. "France." "A quel regiment?" "De la Reine," answered the Highlander. As it happened the French expected a flotilla of provision boats, and after a little further dialogue, in which the cool Highlander completely deceived the French sentries, the British were allowed to slip past in the darkness. The tiny cove was safely reached, the boats stole silently up without a blunder, twenty-four volunteers from the Light Infantry leaped from their boat and led the way in single file up the path, that ran like a thread along the face of the cliff. Wolfe sat eagerly listening in his boat below. Suddenly from the summit he saw the flash of the muskets and heard the stern shout which told him his men were up. A clear, firm order, and the troops sitting silent in the boats leaped ashore, and the long file of soldiers, like a chain of ants, went up the face of the cliff, Wolfe amongst the foremost, and formed in order on the plateau, the boats meanwhile rowing back at speed to bring up the remainder of the troops. Wolfe was at last within Montcalm's guard!

When the morning of the 13th dawned, the British army, in line of battle, stood looking down on Quebec. Montcalm quickly heard the news, and came riding furiously across the St. Charles and past the city to the scene of danger. He rode, as those who saw him tell, with a fixed look, and uttering not a word. The vigilance of months was rendered worthless by that amazing night escalade. When he reached the slopes Montcalm saw before him the silent red wall of British infantry, the Highlanders with waving tartans and wind-blown plumes—all in battle array. It was not a detachment, but an army!

The fight lasted fifteen minutes, and might be told in almost as many words. Montcalm brought on his men in three powerful columns, in number double that of Wolfe's force. The British troops stood grimly silent, though they were tormented by the fire of Indians and Canadians lying in the grass. The French advanced eagerly, with a tumult of shouts and a confused fire; the British moved forward a few rods, halted, dressed their lines, and when the French were within forty paces threw in one fierce volley, so sharply timed that the explosion of 4000 muskets sounded like the sudden blast of a cannon. Again, again, and yet again, the flame ran from end to end of the steadfast hue. When the smoke lifted, the French column were wrecked. The British instantly charged. The spirit of the clan awoke in Fraser's Highlanders: they flung aside their muskets, drew their broadswords, and with a fierce Celtic slogan rushed on the enemy. Never was a charge pressed more ruthlessly home. After the fight one of the British officers wrote: "There was not a bayonet in the three leading British regiments, nor a broadsword amongst the Highlanders, that was not crimson with the blood of a foeman." Wolfe himself charged at the head of the Grenadiers, his bright uniform making him conspicuous. He was shot in the wrist, wrapped a handkerchief round the wound, and still ran forward. Two other bullets struck him—one, it is said, fired by a British deserter, a sergeant broken by Wolfe for brutality to a private. "Don't let the soldiers see me drop," said Wolfe, as he fell, to an officer running beside him. An officer of the Grenadiers, a gentleman volunteer, and a private carried Wolfe to a redoubt near. He refused to allow a surgeon to be called. "There is no need," he said, "it is all over with me." Then one of the little group, casting a look at the smoke-covered battlefield, cried, "They run! See how they run!" "Who run?" said the dying Wolfe, like a man roused from sleep. "The enemy, sir," was the answer. A flash of life came back to Wolfe; the eager spirit thrust from it the swoon of death; he gave a clear, emphatic order for cutting off the enemy's retreat; then, turning on his side, he added, "Now God be praised; I die in peace."

That fight determined that the North American continent should be the heritage of the Anglo-Saxon race. And, somehow, the popular instinct, when the news reached England, realised the historic significance of the event. "When we first heard of Wolfe's glorious deed," writes Thackeray in "The Virginians"—"of that army marshalled in darkness and carried silently up the midnight river—of those rocks scaled by the intrepid leader and his troops—of the defeat of Montcalm on the open plain by the sheer valour of his conqueror—we were all intoxicated in England by the news." Not merely all London but half England flamed into illuminations. One spot alone was dark—Blackheath, where, solitary amidst a rejoicing nation, Wolfe's mother mourned for her heroic son—like Milton's Lycidas—"dead ere his prime."

THE ENGLISH FLAG

"What is the flag of England? Winds of the world, declare!

********

The lean white bear hath seen it in the long, long Arctic night,

The musk-ox knows the standard that flouts the Northern light.

********

Never was isle so little, never was sea so lone,

But over the scud and the palm-trees an English flag has flown.

I have wrenched it free from the halliard to hang for a wisp on the Horn;

I have chased it north to the Lizard—ribboned and rolled and torn;

I have spread its folds o'er the dying, adrift in a hopeless sea;

I have hurled it swift on the slaver, and seen the slave set free.

********

Never the lotos closes, never the wild-fowl wake,

But a soul goes out on the East Wind, that died for England's sake—

Man or woman or suckling, mother or bride or maid—

Because on the bones of the English, the English flag is stayed.

********

The dead dumb fog hath wrapped it—the frozen dews have kissed—

The naked stars have seen it, a fellow-star in the mist.

What is the flag of England? Ye have but my breath to dare;

Ye have but my waves to conquer. Go forth, for it is there!"

—KIPLING.

"The great Lord Hawke" is Burke's phrase, and is one of the best-earned epithets in literature. Yet what does the average Englishman to-day remember of the great sailor who, through the bitter November gales of 1759, kept dogged and tireless watch over the French fleet in Brest, destroyed that fleet with heroic daring amongst the sands of Quiberon, while the fury of a Bay of Biscay tempest almost drowned the roar of his guns, and so crushed a threatened invasion of England?

Hawke has been thrown by all-devouring Time into his wallet as mere "alms for oblivion"; yet amongst all the sea-dogs who ever sailed beneath "the blood-red flag" no one ever less deserved that fate. Campbell, in "Ye Mariners of England," groups "Blake and mighty Nelson" together as the two great typical English sailors. Hawke stands midway betwixt them, in point both of time and of achievements, though he had more in him of Blake than of Nelson. He lacked, no doubt, the dazzling electric strain that ran through the war-like genius of Nelson. Hawke's fighting quality was of the grim, dour home-spun character; but it was a true genius for battle, and as long as Great Britain is a sea-power the memory of the great sailor who crushed Gentians off Quiberon deserves to live.

Hawke, too, was a great man in the age of little men. The fame of the English navy had sunk to the lowest point. Its ships were rotten; its captains had lost the fighting tradition; its fleets were paralysed by a childish system of tactics which made a decisive battle almost impossible. Hawke describes the Portland, a ship of which he was in command, as "iron-sick"; the wood was too rotten, that is, to hold the iron bolts, so that "not a man in the ship had a dry place to sleep in." His men were "tumbling down with scurvy"; his mainmast was so pulverised by dry rot that a walking-stick could be thrust into it. Of another ship, the Ramilies—his favourite ship, too—he says, "It became water-logged whenever it blowed hard." The ships' bottoms grew a rank crop of grass, slime, shells, barnacles, &c., till the sluggish vessels needed almost a gale to move them. Marines were not yet invented; the navy had no uniform. The French ships of that day were better built, better armed, and sometimes better fought than British ships. A British 70-gun ship in armament and weight of fire was only equal to a French ship of 52 guns. Every considerable fight was promptly followed by a crop of court-martials, in which captains were tried for misconduct before the enemy, such as to-day is unthinkable. Admiral Matthews was broken by court-martial for having, with an excess of daring, pierced the French line off Toulon, and thus sacrificed pedantic tactics to victory. But the list of court-martials held during the second quarter of the eighteenth century on British captains for beginning to fight too late, or for leaving off too soon, would, if published, astonish this generation. After the fight off Toulon in 1744, two admirals and six post-captains were court-martialled. Admiral Byng was shot on his own deck, not exactly as Voltaire's mot describes it, pour encourager les autres, and not quite for cowardice, for Byng was no coward. But he had no gleam of unselfish patriotic fire, and nothing of the gallant fighting impulse we have learned to believe is characteristic of the British sailor. He lost Minorca, and disgraced the British flag because he was too dainty to face the stern discomforts of a fight. The corrupt and ignoble temper of English politics—the legacy of Walpole's evil régime—poisoned the blood of the navy. No one can have forgotten Macaulay's picture of Newcastle, at that moment Prime Minister of England; the sly, greedy, fawning politician, as corrupt as Walpole, without his genius; without honour, without truth, who loved office only less than he loved his own neck. A Prime Minister like Newcastle made possible an admiral like Byng. Horace Walpole tells the story of how, when the much-enduring British public broke into one of its rare but terrible fits of passion after the disgrace of Minorca, and Newcastle was trembling for his own head, a deputation from the city of London waited upon him, demanding that Byng should be put upon his trial. "Oh, indeed," replied Newcastle, with fawning gestures, "he shall be tried immediately. He shall be hanged directly!" It was an age of base men, and the navy—neglected, starved, dishonoured—had lost the great traditions of the past, and did not yet feel the thrill of the nobler spirit soon to sweep over it.

But in 1759 the dazzling intellect and masterful will of the first Pitt controlled the fortunes of England, and the spirit of the nation was beginning to awake. Burns and Wilberforce and the younger Pitt were born that year; Minden was fought; Wolfe saw with dying eyes the French battalions broken on the plains of Abraham and Canada won. But the great event of the year is Hawke's defeat of Conflans off Quiberon. Hawke was the son of a barrister; he entered the navy at fourteen years of age as a volunteer, obtained the rating of an able seaman at nineteen years of age, was a third lieutenant at twenty-four, and became captain at thirty. He knew the details of his profession as well as any sea-dog of the forecastle, was quite modern in the keen and humane interest he took in his men, had something of Wellington's high-minded allegiance to duty, while his fighting had a stern but sober thoroughness worthy of Cromwell's Ironsides. The British people came to realise that he was a sailor with the strain of a bulldog in him; an indomitable fighter, who, ordered to blockade a hostile port, would hang on, in spite of storms and scurvy, while he had a man left who could pull a rope or fire a gun; a fighter, too, of the type dear to the British imagination, who took the shortest course to the enemy's line, and would exchange broadsides at pistol-shot distance while his ship floated.

In 1759 a great French army threatened the shores of England. At Havre and Dunkirk huge flotillas of flat-bottomed boats lay at their moorings; 18,000 French veterans were ready to embark. A great fleet under the command of Conflans—one of the ablest seamen France has ever produced—was gathered at Brest. A French squadron was to break out of Toulon, join Conflans, sweep the narrow seas, and convoy the French expedition to English shores. The strategy, if it had succeeded, might have changed the fate of the world.

To Hawke was entrusted the task of blockading Conflans in Brest, and a greater feat of seamanship is not to be found in British records. The French fleet consisted of 25 ships, manned by 15,200 men, and carrying 1598 guns. The British fleet numbered 23 ships, with 13,295 men, and carrying 1596 guns. The two fleets, that is, were nearly equal, the advantage, on the whole, being on the side of the French. Hawke therefore had to blockade a fleet equal to his own, the French ships lying snugly in harbour, the English ships scourged by November gales and rolling in the huge seas of the Bay of Biscay. Sir Cloudesley Shovel, himself a seaman of the highest quality, said that "an admiral would deserve to be broke who kept great ships out after the end of September, and to be shot if after October." Hawke maintained his blockade of Brest for six months. His captains broke down in health, his men were dying from scurvy, the bottoms of his ships grew foul; it was a stormy season in the stormiest of seas. Again and again the wild north-west gales blew the British admiral off his cruising ground. But he fought his way back, sent his ships, singly or in couples, to Torbay or Plymouth for a moment's breathing space, but himself held on, with a grim courage and an unslumbering vigilance which have never been surpassed. On November 6, a tremendous westerly gale swept over the English cruising-ground. Hawke battled with it for three days, and then ran, storm-driven and half-dismantled, to Torbay for shelter on the 10th. He put to sea again on the 12th. The gale had veered round to the south-west, but blew as furiously as ever, and Hawke was once more driven back on the 13th to Torbay. He struggled out again on the 14th, to find that the French had escaped! The gale that blew Hawke from his post brought a French squadron down the Channel, which ran into Brest and joined Conflans there; and on the 14th, when Hawke was desperately fighting his way back to his post, Conflans put to sea, and, with the gale behind him, ran on his course to Quiberon. There he hoped to brush aside the squadron keeping guard over the French transports, embark the powerful French force assembled there, and swoop down on the English coast. The wild weather, Conflans reckoned, would keep Hawke storm-bound in Torbay till this scheme was carried out.

But Hawke with his whole fleet, fighting his way in the teeth of the gale, reached Ushant on the very day Conflans broke out of Brest, and, fast as the French fleet ran before the gale, the white sails of Hawke's ships, showing over the stormy rim of the horizon, came on the Frenchman's track. Hawke's frigates, outrunning those heavy sea-waggons, his line-of-battle ships, hung on Conflans' rear. The main body of the British fleet followed, staggering under their pyramids of sails, with wet decks and the wild north-west gale on their quarter. Hawke's best sailers gained steadily on the laggards of Conflans' fleet. Had Hawke obeyed the puerile tactics of his day he would have dressed his line and refused to attack at all unless he could bring his entire fleet into action. But, as Hawke himself said afterwards, he "had determined to attack them in the old way and make downright work of them," and he signalled his leading ships to attack the moment they brought an enemy's ship within fire. Conflans could not abandon his slower ships, and he reluctantly swung round his van and formed line to meet the attack.

As the main body of the English came up, the French admiral suddenly adopted a strategy which might well have baffled a less daring adversary than Hawke. He ran boldly in shore towards the mouth of the Vilaine. It was a wild stretch of most dangerous coast; the granite Breton hills above; splinters of rocky islets, on which the huge sea rollers tore themselves into white foam, below; and more dangerous still, and stretching far out to sea, wide reaches of shoal and quicksand. From the north-west the gale blew more wildly than ever; the sky was black with flying clouds; on the Breton hills the spectators clustered in thousands. The roar of the furious breakers and the shrill note of the gale filled the very air with tumult. Conflans had pilots familiar with the coast, yet it was bold seamanship on his part to run down to a lee shore on such a day of tempest. Hawke had no pilots and no charts; but he saw before him, half hidden in mist and spray, the great hulls of the ships over which he had kept watch so long in Brest harbour, and he anticipated Nelson's strategy forty years afterwards. "Where there is room for the enemy to swing," said Nelson, "there is room for me to anchor." "Where there's a passage for the enemy," argued Hawke, "there is a passage for me! Where a Frenchman can sail, an Englishman can follow! Their pilots shall be ours. If they go to pieces in the shoals, they will serve as beacons for us."

And so, on the wild November afternoon, with the great billows that the Bay of Biscay hurls on that stretch of iron-bound coast riding shoreward in league-long rollers, Hawke flung himself into the boiling caldron of rocks and shoals and quicksands. No more daring deed was ever done at sea. Measured by mere fighting courage, there were thousands of men in the British fleet as brave as Hawke. But the iron nerve that, without an instant's pause, in a scene so wild, on a shore so perilous, and a sea sown so thick with unknown dangers, flung a whole fleet into battle, was probably possessed by no other man than Hawke amongst the 30,000 gallant sailors who fought at Quiberon.

The fight, taking all its incidents into account, is perhaps as dramatic as anything known in the history of war. The British ships came rolling on, grim and silent, throwing huge sheets of spray from their bluff bows. An 80-gun French ship, Le Formidable, lay in their track, and each huge British liner, as it swept past to attack the main body of the French, vomited on the unfortunate Le Formidable a dreadful broadside. And upon each British ship, in turn, as it rolled past in spray and flame, the gallant Frenchman flung an answering broadside. Soon the thunder of the guns deepened as ship after ship found its antagonist. The short November day was already darkening; the thunder of surf and of tempest answered in yet wilder notes the deep-throated guns; the wildly rolling fleets offered one of the strangest sights the sea has ever witnessed.

Soon Hawke himself, in the Royal George, of 100 guns, came on, stern and majestic, seeking some fitting antagonist. This was the great ship that afterwards sank ignobly at its anchorage at Spithead, with "twice four hundred men," a tale which, for every English boy, is made famous in Cowper's immortal ballad. But what an image of terror and of battle the Royal George seemed as in the bitter November storm she bore down on the French fleet! Hawke disdained meaner foes, and bade his pilot lay him alongside Conflans' flagship, Le Soleil Royal. Shoals were foaming on every side, and the pilot warned Hawke he could not carry the Royal George farther in without risking the ship. "You have done your duty," said Hawke, "in pointing out the risk; and now lay me alongside of Le Soleil Royal."

A French 70-gun ship, La Superbe, threw itself betwixt Hawke and Conflans. Slowly the huge mass of the Royal George bore up, so as to bring its broadside to bear on La Superbe, and then the English guns broke into a tempest of flame. Through spray and mist the masts of the unfortunate Frenchman seemed to tumble; a tempest of cries was heard; the British sailors ran back their guns to reload. A sudden gust cleared the atmosphere, and La Superbe had vanished. Her top-masts gleamed wet, for a moment, through the green seas, but with her crew of 650 men she had sunk, as though crushed by a thunderbolt, beneath a single broadside from the Royal George. Then from the nearer hills the crowds of French spectators saw Hawke's blue flag and Conflans' white pennon approach each other, and the two great ships, with slanting decks and fluttering canvas, and rigging blown to leeward, began their fierce duel. Other French ships crowded to their admiral's aid, and at one time no less than seven French line-of-battle ships were pouring their fire into the mighty and shot-torn bulk of the Royal George.

Howe, in the Magnanime, was engaged in fierce conflict, meanwhile, with the Thesée, when a sister English ship, the Montague, was flung by a huge sea on the quarter of Howe's ship, and practically disabled it. The Torbay, under Captain Keppel, took Howe's place with the Thesée, and both ships had their lower-deck ports open, so as to fight with their heaviest guns. The unfortunate Frenchman rolled to a great sea; the wide-open ports dipped, the green water rushed through, quenched the fire of the guns, and swept the sailors from their quarters. The great ship shivered, rolled over still more wildly, and then, with 700 men, went down like a stone. The British ship, with better luck and better seamanship, got its ports closed and was saved. Several French ships by this time had struck, but the sea was too wild to allow them to be taken possession of. Night was falling fast, the roar of the tempest still deepened, and no less than seven huge French liners, throwing their guns overboard, ran for shelter across the bar of the Vilaine, the pursuing English following them almost within reach of the spray flung from the rocks. Hawke then, by signals, brought his fleet to anchor for the night under the lee of the island of Dumet.

It was a wild night, filled with the thunder of the surf and the shriek of the gale, and all through it, as the English ships rode, madly straining at their anchors, they could hear the sounds of distress guns. One of the ships that perished that night was a fine English seventy-four, the Resolution. The morning broke as wild as the night. To leeward two great line-of-battle ships could be seen on the rocks; but in the very middle of the English fleet, its masts gone, its hull battered with shot, was the flagship of Conflans, Le Soleil Royal. In the darkness and tempest of the night the unfortunate Frenchman, all unwitting, had anchored in the very midst of his foes. As soon as, through the grey and misty light of the November dawn, the English ships were discovered, Conflans cut his cables and drifted ashore. The Essex, 64 guns, was ordered to pursue her, and her captain, an impetuous Irishman, obeyed his orders so literally that he too ran ashore, and the Essex became a total wreck.

"When I consider," Hawke wrote to the Admiralty, "the season of the year, the hard gales on the day of action, a flying enemy, the shortness of the day, and the coast they were on, I can boldly affirm that all that could possibly be done has been done." History confirms that judgment. There is no other record of a great sea-fight fought under conditions so wild, and scarcely any other sea-battle has achieved results more decisive. Trafalgar itself scarcely exceeds it in the quality of effectiveness. Quiberon saved England from invasion. It destroyed for the moment the naval power of France. Its political results in France cannot be described here, but they were of the first importance. The victory gave a new complexion to English naval warfare. Rodney and Howe were Hawke's pupils, Nelson himself, who was a post-captain when Hawke died, learned his tactics in Hawke's school. No sailor ever served England better than Hawke. And yet, such is the irony of human affairs, that on the very day when Hawke was adding the thunder of his guns to the diapason of surf and tempest off Quiberon, and crushing the fleet that threatened England with invasion, a London mob was burning his effigy for having allowed the French to escape his blockade.

"Hand to hand, and foot to foot;

Nothing there, save death, was mute:

Stroke, and thrust, and flash, and cry

For quarter or for victory,

Mingle there with the volleying thunder,

Which makes the distant cities wonder

How the sounding battle goes,

If with them, or for their foes;

If they must mourn, or must rejoice

In that annihilating voice,

Which pierces the deep hills through and through

With an echo dread and new.

******

From the point of encountering blades to the hilt,

Sabres and swords with blood were gilt;

But the rampart is won, and the spoil begun,

And all but the after carnage done."

—BYRON.

It would be difficult to find in the whole history of war a more thrilling and heroic chapter than that which tells the story of the six great campaigns of the Peninsular war. This was, perhaps, the least selfish war of which history tells. It was not a war of aggrandisement or of conquest: it was waged to deliver not merely Spain, but the whole of Europe, from that military despotism with which the genius and ambition of Napoleon threatened to overwhelm the civilised world. And on what a scale Great Britain, when aroused, can fight, let the Peninsular war tell. At its close the fleets of Great Britain rode triumphant on every sea; and in the Peninsula between 1808-14 her land forces fought and won nineteen pitched battles, made or sustained ten fierce and bloody sieges, took four great fortresses, twice expelled the French from Portugal and once from Spain. Great Britain expended in these campaigns more than 100,000,000 pounds sterling on her own troops, besides subsidising the forces of Spain and Portugal. This "nation of shopkeepers" proved that when kindled to action it could wage war on a scale and in a fashion that might have moved the wonder of Alexander or of Caesar, and from motives, it may be added, too lofty for either Caesar or Alexander so much as to comprehend. It is worth while to tell afresh the story of some of the more picturesque incidents in that great strife.

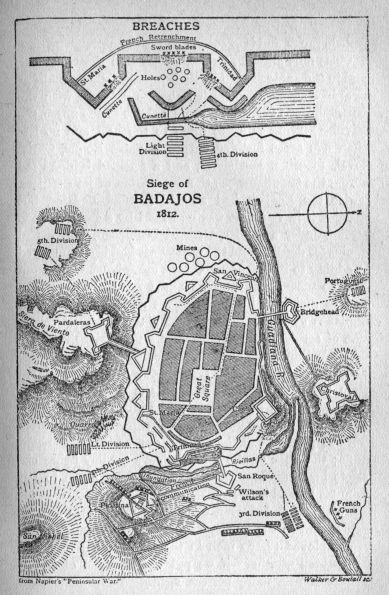

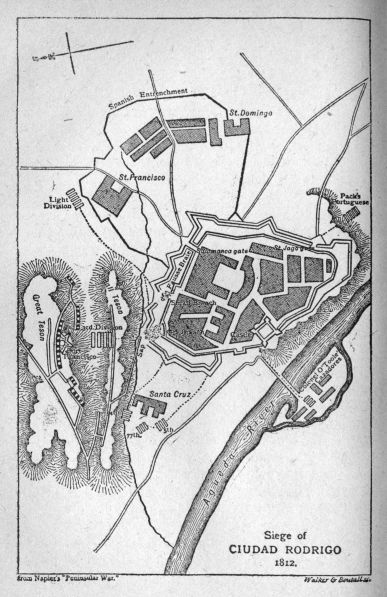

On April 6, 1812, Badajos was stormed by Wellington; and the story forms one of the most tragical and splendid incidents in the military history of the world. Of "the night of horrors at Badajos," Napier says, "posterity can scarcely be expected to credit the tale." No tale, however, is better authenticated, or, as an example of what disciplined human valour is capable of achieving, better deserves to be told. Wellington was preparing for his great forward movement into Spain, the campaign which led to Salamanca, the battle in which "40,000 Frenchmen were beaten in forty minutes." As a preliminary he had to capture, under the vigilant eyes of Soult and Marmont, the two great border fortresses, Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos. He had, to use Napier's phrase, "jumped with both feet" on the first-named fortress, and captured it in twelve days with a loss of 1200 men and 90 officers.

But Badajos was a still harder task. The city stands on a rocky ridge which forms the last spur of the Toledo range, and is of extraordinary strength. The river Rivillas falls almost at right angles into the Guadiana, and in the angle formed by their junction stands Badajos, oval in shape, girdled with elaborate defences, with the Guadiana 500 yards wide as its defence to the north, the Rivillas serving as a wet ditch to the east, and no less than five great fortified outposts—Saint Roque, Christoval, Picurina, Pardaleras, and a fortified bridge-head across the Guadiana—as the outer zone of its defences. Twice the English had already assailed Badajos, but assailed it in vain. It was now held by a garrison 5000 strong, under a soldier, General Phillipson, with a real genius for defence, and the utmost art had been employed in adding to its defences. On the other hand Wellington had no means of transport and no battery train, and had to make all his preparations under the keen-eyed vigilance of the French. Perhaps the strangest collection of artillery ever employed in a great siege was that which Wellington collected from every available quarter and used at Badajos. Of the fifty-two pieces, some dated from the days of Philip II. and the Spanish Armada, some were cast in the reign of Philip III., others in that of John IV. of Portugal, who reigned in 1640; there were 24-pounders of George II.'s day, and Russian naval guns; the bulk of the extraordinary medley being obsolete brass engines which required from seven to ten minutes to cool between each discharge.

Wellington, however, was strong in his own warlike genius and in the quality of the troops he commanded. He employed 18,000 men in the siege, and it may well be doubted whether—if we put the question of equipment aside—a more perfect fighting instrument than the force under his orders ever existed. The men were veterans, but the officers on the whole were young, so there was steadiness in the ranks and fire in the leading. Hill and Graham covered the siege, Picton and Barnard, Kempt and Colville led the assaults. The trenches were held by the third, fourth, and fifth divisions, and by the famous light division. Of the latter it has been said that the Macedonian phalanx of Alexander the Great, the Tenth Legion of Caesar, the famous Spanish infantry of Alva, or the iron soldiers who followed Cortes to Mexico, did not exceed it in warlike quality. Wellington's troops, too, had a personal grudge against Badajos, and had two defeats to avenge. Perhaps no siege in history, as a matter of fact, ever witnessed either more furious valour in the assault, or more of cool and skilled courage in the defence. The siege lasted exactly twenty days, and cost the besiegers 5000 men, or an average loss of 250 per day. It was waged throughout in stormy weather, with the rivers steadily rising, and the tempests perpetually blowing; yet the thunder of the attack never paused for an instant.

Wellington's engineers attacked the city at the eastern end of the oval, where the Rivillas served it as a gigantic wet ditch; and the Picurina, a fortified hill, ringed by a ditch fourteen feet deep, a rampart sixteen feet high, and a zone of mines, acted as an outwork. Wellington, curiously enough, believed in night attacks, a sure proof of his faith in the quality of the men he commanded; and on the eighth night of the siege, at nine o'clock, 500 men of the third division were suddenly flung on the Picurina. The fort broke into a ring of flame, by the light of which the dark figures of the stormers were seen leaping with fierce hardihood into the ditch and struggling madly up the ramparts, or tearing furiously at the palisades. But the defences were strong, and the assailants fell literally in scores. Napier tells how "the axemen of the light division, compassing the fort like prowling wolves," discovered the gate at the rear, and so broke into the fort. The engineer officer who led the attack declares that "the place would never have been taken had it not been for the coolness of these men" in absolutely walking round the fort to its rear, discovering the gate, and hewing it down under a tempest of bullets. The assault lasted an hour, and in that period, out of the 500 men who attacked, no less than 300, with 19 officers, were killed or wounded! Three men out of every five in the attacking force, that is, were disabled, and yet they won!

There followed twelve days of furious industry, of trenches pushed tirelessly forward through mud and wet, and of cannonading that only ceased when the guns grew too hot to be used. Captain MacCarthy, of the 50th Regiment, has left a curious little monograph on the siege, full of incidents, half tragic and half amusing, but which show the temper of Wellington's troops. Thus he tells how an engineer officer, when marking out the ground for a breaching-battery very near the wall, which was always lined with French soldiers in eager search of human targets, "used to challenge them to prove the perfection of their shooting by lifting up the skirts of his coat in defiance several times in the course of his survey; driving in his stakes and measuring his distances with great deliberation, and concluding by an extra shake of his coat-tails and an ironical bow before he stepped under shelter!"

On the night of April 6, Wellington determined to assault. No less than seven attacks were to be delivered. Two of them—on the bridge-head across the Guadiana and on the Pardaleras—were mere feints. But on the extreme right Picton with the third division was to cross the Rivillas and escalade the castle, whose walls rose time-stained and grim, from eighteen to twenty-four feet high. Leith with the fifth division was to attack the opposite or western extremity of the town, the bastion of St. Vincente, where the glacis was mined, the ditch deep, and the scarp thirty feet high. Against the actual breaches Colville and Andrew Barnard were to lead the light division and the fourth division, the former attacking the bastion of Santa Maria and the latter the Trinidad. The hour was fixed for ten o'clock, and the story of that night attack, as told in Napier's immortal prose, is one of the great battle-pictures of literature; and any one who tries to tell the tale will find himself slipping insensibly into Napier's cadences.

The night was black; a strange silence lay on rampart and trench, broken from time to time by the deep voices of the sentinels that proclaimed all was well in Badajos. "Sentinelle garde à vous," the cry of the sentinels, was translated by the British private as "All's well in Badahoo!" A lighted carcass thrown from the castle discovered Picton's men standing in ordered array, and compelled them to attack at once. MacCarthy, who acted as guide across the tangle of wet trenches and the narrow bridge that spanned the Rivillas, has left an amusing account of the scene. At one time Picton declared MacCarthy was leading them wrong, and, drawing his sword, swore he would cut him down. The column reached the trench, however, at the foot of the castle walls, and was instantly overwhelmed with the fire of the besieged. MacCarthy says we can only picture the scene by "supposing that all the stars, planets, and meteors of the firmament, with innumerable moons emitting smaller ones in their course, were descending on the heads of the besiegers." MacCarthy himself, a typical and gallant Irishman, addressed his general with the exultant remark, "Tis a glorious night, sir—a glorious night!" and, rushing forward to the head of the stormers, shouted, "Up with the ladders!" The five ladders were raised, the troops swarmed up, an officer leading, but the first files were at once crushed by cannon fire, and the ladders slipped into the angle of the abutments. "Dreadful their fall," records MacCarthy of the slaughtered stormers, "and appalling their appearance at daylight." One ladder remained, and, a private soldier leading, the eager red-coated crowd swarmed up it. The brave fellow leading was shot as soon as his head appeared above the parapet; but the next man to him—again a private—leaped over the parapet, and was followed quickly by others, and this thin stream of desperate men climbed singly, and in the teeth of the flashing musketry, up that solitary ladder, and carried the castle.

In the meanwhile the fourth and light divisions had flung themselves with cool and silent speed on the breaches. The storming party of each division leaped into the ditch. It was mined, the fuse was kindled, and the ditch, crowded with eager soldiery, became in a moment a sort of flaming crater, and the storming parties, 500 strong, were in one fierce explosion dashed to pieces. In the light of that dreadful flame the whole scene became visible—the black ramparts, crowded with dark figures and glittering arms, on the one side; on the other the red columns of the British, broad and deep, moving steadily forward like a stream of human lava. The light division stood at the brink of the smoking ditch for an instant, amazed at the sight. "Then," says Napier, "with a shout that matched even the sound of the explosion," they leaped into it and swarmed up to the breach. The fourth division came running up and descended with equal fury, but the ditch opposite the Trinidad was filled with water; the head of the division leaped into it, and, as Napier puts it, "about 100 of the fusiliers, the men of Albuera, perished there." The breaches were impassable. Across the top of the great slope of broken wall glittered a fringe of sword-blades, sharp-pointed, keen-edged on both sides, fixed in ponderous beams chained together and set deep in the ruins. For ten feet in front the ascent was covered with loose planks, studded with sharp iron points. Behind the glittering edge of sword-blades stood the solid ranks of the French, each man supplied with three muskets, and their fire scourged the British ranks like a tempest.

Hundreds had fallen, hundreds were still falling; but the British clung doggedly to the lower slopes, and every few minutes an officer would leap forward with a shout, a swarm of men would instantly follow him, and, like leaves blown by a whirlwind, they swept up the ascent. But under the incessant fire of the French the assailants melted away. One private reached the sword-blades, and actually thrust his head beneath them till his brains were beaten out, so desperate was his resolve to get into Badajos. The breach, as Napier describes it, "yawning and glittering with steel, resembled the mouth of a huge dragon belching forth smoke and flame." But for two hours, and until 2000 men had fallen, the stubborn British persisted in their attacks. Currie, of the 52nd, a cool and most daring soldier, found a narrow ramp beyond the Santa Maria breach only half-ruined; he forced his way back through the tumult and carnage to where Wellington stood watching the scene, obtained an unbroken battalion from the reserve, and led it towards the broken ramp. But his men were caught in the whirling madness of the ditch and swallowed up in the tumult. Nicholas, of the engineers, and Shaw, of the 43rd, with some fifty soldiers, actually climbed into the Santa Maria bastion, and from thence tried to force their way into the breach. Every man was shot down except Shaw, who stood alone on the bastion. "With inexpressible coolness he looked at his watch, said it was too late to carry the breaches," and then leaped down! The British could not penetrate the breach; but they would not retreat. They could only die where they stood. The buglers of the reserve were sent to the crest of the glacis to sound the retreat; the troops in the ditch would not believe the signal to be genuine, and struck their own buglers who attempted to repeat it. "Gathering in dark groups, and leaning on their muskets," says Napier, "they looked up in sullen desperation at Trinidad, while the enemy, stepping out on the ramparts, and aiming their shots by the light of fireballs, which they threw over, asked as their victims fell, 'Why they did not come into Badajos.'"

All this while, curiously enough, Picton was actually in Badajos, and held the castle securely, but made no attempt to clear the breach. On the extreme west of the town, however, at the bastion of San Vincente, the fifth division made an attack as desperate as that which was failing at the breaches. When the stormers actually reached the bastion, the Portuguese battalions, who formed part of the attack, dismayed by the tremendous fire which broke out on them, flung down their ladders and fled. The British, however, snatched the ladders up, forced the barrier, jumped into the ditch, and tried to climb the walls. These were thirty feet high, and the ladders were too short. A mine was sprung in the ditch under the soldiers' feet; beams of wood, stones, broken waggons, and live shells were poured upon their heads from above. Showers of grape from the flank swept the ditch.

The stubborn soldiers, however, discovered a low spot in the rampart, placed three ladders against it, and climbed with reckless valour. The first man was pushed up by his comrades; he, in turn, dragged others up, and the unconquerable British at length broke through and swept the bastion. The tumult still stormed and raged at the eastern breaches, where the men of the light and fourth division were dying sullenly, and the men of the fifth division marched at speed across the town to take the great eastern breach in the rear. The streets were empty, but the silent houses were bright with lamps. The men of the fifth pressed on; they captured mules carrying ammunition to the breaches, and the French, startled by the tramp of the fast-approaching column, and finding themselves taken in the rear, fled. The light and fourth divisions broke through the gap hitherto barred by flame and steel, and Badajos was won!