The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Last Harvest, by John Burroughs This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Last Harvest Author: John Burroughs Release Date: July 25, 2006 [EBook #18903] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LAST HARVEST *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Sankar Viswanathan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Wordsworth

Most of the papers garnered here were written after fourscore years—after the heat and urge of the day—and are the fruit of a long life of observation and meditation.

The author's abiding interest in Emerson is shown in his close and eager study of the Journals during these later years. He hungered for everything that concerned the Concord Sage, who had been one of the most potent influences in his life. Although he could discern flies in the Emersonian amber, he could not brook slight or indifference toward Emerson in the youth of to-day. Whatever flaws he himself detected, he well knew that Emerson would always rest secure on the pedestal where long ago he placed him. Likewise with Thoreau: If shortcomings were to be pointed out in this favorite, he wished to be the one to do it. And so, before taking Thoreau to task for certain inaccuracies, he takes Lowell to task for criticizing Thoreau. He then proceeds, not without evident satisfaction, to call attention to Thoreau's "slips" as an observer and reporter of nature; yet in no carping spirit, but, as he himself has said: "Not that I love Thoreau less, but that I love truth more."

The "Short Studies in Contrasts," the "Day by [viii]Day" notes, "Gleanings," and the "Sundown Papers" which comprise the latter part of this, the last, posthumous volume by John Burroughs, were written during the closing months of his life. Contrary to his custom, he wrote these usually in the evening, or, less frequently, in the early morning hours, when, homesick and far from well, with the ceaseless pounding of the Pacific in his ears, and though incapable of the sustained attention necessary for his best work, he was nevertheless impelled by an unwonted mental activity to seek expression.

If the reader misses here some of the charm and power of his usual writing, still may he welcome this glimpse into what John Burroughs was doing and thinking during those last weeks before the illness came which forced him to lay aside his pen.

Clara Barrus

Woodchuck Lodge

Roxbury-in-the-Catskills

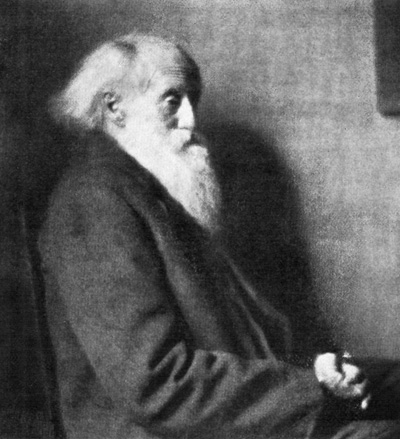

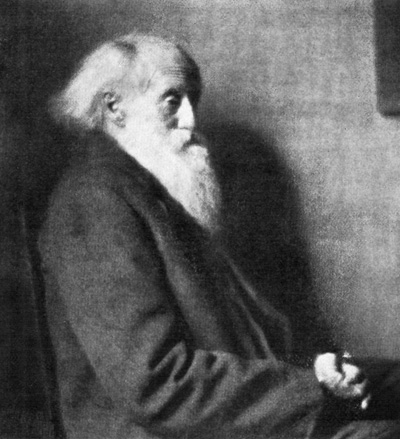

The frontispiece portrait is from a photograph by Miss Mabel Watson taken at Pasadena, California, shortly before Mr. Burroughs's death.

Emerson's fame as a writer and thinker was firmly established during his lifetime by the books he gave to the world. His Journals, published over a quarter of a century after his death, nearly or quite double the bulk of his writing, and while they do not rank in literary worth with his earlier works, they yet throw much light upon his life and character and it is a pleasure to me, in these dark and troublesome times,[1] and near the sun-down of my life, to go over them and point out in some detail their value and significance.

[1] Written during the World War.—C.B.

Emerson was such an important figure in our literary history, and in the moral and religious development of our people, that attention cannot be directed to him too often. He could be entirely reconstructed from the unpublished matter which he left. Moreover, just to come in contact with him in times like ours is stimulating and refreshing. The younger generation will find that he [2]can do them good if they will pause long enough in their mad skirting over the surface of things to study him.

For my own part, a lover of Emerson from early manhood, I come back to him in my old age with a sad but genuine interest. I do not hope to find the Emerson of my youth—the man of daring and inspiring affirmation, the great solvent of a world of encrusted forms and traditions, which is so welcome to a young man—because I am no longer a young man. Emerson is the spokesman and prophet of youth and of a formative, idealistic age. His is a voice from the heights which are ever bathed in the sunshine of the spirit. I find that something one gets from Emerson in early life does not leave him when he grows old. It is a habit of mind, a test of values, a strengthening of one's faith in the essential soundness and goodness of creation. He helps to make you feel at home in nature, and in your own land and generation. He permanently exalts your idea of the mission of the poet, of the spiritual value of the external world, of the universality of the moral law, and of our kinship with the whole of nature.

There is never any despondency or infirmity of faith in Emerson. He is always hopeful and courageous, and is an antidote to the pessimism and materialism which existing times tend to foster. Open anywhere in the Journals or in the Essays[3] and we find the manly and heroic note. He is an unconquerable optimist, and says boldly, "Nothing but God can root out God," and he thinks that in time our culture will absorb the hells also. He counts "the dear old Devil" among the good things which the dear old world holds for him. He saw so clearly how good comes out of evil and is in the end always triumphant. Were he living in our day, he would doubtless find something helpful and encouraging to say about the terrific outburst of scientific barbarism in Europe.

It is always stimulating to hear a man ask such a question as this, even though he essay no answer to it: "Is the world (according to the old doubt) to be criticized otherwise than as the best possible in the existing system, and the population of the world the best that soils, climate, and animals permit?"

I note that in 1837 Emerson wrote this about the Germans; "I do not draw from them great influence. The heroic, the holy, I lack. They are contemptuous. They fail in sympathy with humanity. The voice of nature they bring me to hear is not divine, but ghastly, hard, and ironical. They do not illuminate me: they do not edify me." Is not this the German of to-day? If Emerson were with us now he would see, as we all see, how the age of idealism and spiritual power in Germany that gave the world the great composers[4] and the great poets and philosophers—Bach, Beethoven, Wagner, Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Kant, Hegel, and others—has passed and been succeeded by the hard, cruel, and sterile age of materialism, and the domination of an aggressive and conscienceless military spirit. Emerson was the poet and prophet of man's moral nature, and it is this nature—our finest and highest human sensibilities and aspirations toward justice and truth—that has been so raided and trampled upon by the chief malefactor and world outlaw in the present war.

Men who write Journals are usually men of certain marked traits—they are idealists, they love solitude rather than society, they are self-conscious, and they love to write. At least this seems to be true of the men of the past century who left Journals of permanent literary worth—Amiel, Emerson, and Thoreau. Amiel's Journal has more the character of a diary than has Emerson's or Thoreau's, though it is also a record of thoughts as well as of days. Emerson left more unprinted matter than he chose to publish during his lifetime.

The Journals of Emerson and Thoreau are largely made up of left-overs from their published works, and hence as literary material, when compared with their other volumes, are of secondary im[5]portance. You could not make another "Walden" out of Thoreau's Journals, nor build up another chapter on "Self-Reliance," or on "Character," or on the "Over-Soul," from Emerson's, though there are fragments here and there in both that are on a level with their best work.

Emerson records in 1835 that his brother Charles wondered that he did not become sick at the stomach over his poor Journal: "Yet is obdurate habit callous even to contempt. I must scribble on...." Charles evidently was not a born scribbler like his brother. He was clearly more fond of real life and of the society of his fellows. He was an orator and could not do himself justice with the pen. Men who write Journals, as I have said, are usually men of solitary habits, and their Journal largely takes the place of social converse. Amiel, Emerson, and Thoreau were lonely souls, lacking in social gifts, and seeking relief in the society of their own thoughts. Such men go to their Journals as other men go to their clubs. They love to be alone with themselves, and dread to be benumbed or drained of their mental force by uncongenial persons. To such a man his Journal becomes his duplicate self and he says to it what he could not say to his nearest friend. It becomes both an altar and a confessional. Especially is this true of deeply religious souls such as the men I have named. They commune, through their[6] Journals, with the demons that attend them. Amiel begins his Journal with the sentence, "There is but one thing needful—to possess God," and Emerson's Journal in its most characteristic pages is always a search after God, or the highest truth.

"After a day of humiliation and stripes," he writes, "if I can write it down, I am straightway relieved and can sleep well. After a day of joy, the beating heart is calmed again by the diary. If grace is given me by all angels and I pray, if then I can catch one ejaculation of humility or hope and set it down in syllables, devotion is at an end." "I write my journal, I deliver my lecture with joy," but "at the name of society all my repulsions play, all my quills rise and sharpen."

He clearly had no genius for social intercourse. At the age of thirty he said he had "no skill to live with men; that is, such men as the world is made of; and such as I delight in I seldom find." Again he says, aged thirty-two, "I study the art of solitude; I yield me as gracefully as I can to destiny," and adds that it is "from eternity a settled thing" that he and society shall be "nothing to each other." He takes to his Journal instead. It is his house of refuge.

Yet he constantly laments how isolated he is, mainly by reason of the poverty of his nature, his want of social talent, of animal heat, and of sympathy with the commonplace and the humdrum.[7] "I have no animal spirits, therefore when surprised by company and kept in a chair for many hours, my heart sinks, my brow is clouded, and I think I will run for Acton woods and live with the squirrels henceforth." But he does not run away; he often takes it out in hoeing in his garden: "My good hoe as it bites the ground revenges my wrongs, and I have less lust to bite my enemies." "In smoothing the rough hillocks I smooth my temper. In a short time I can hear the bobolinks sing and see the blessed deluge of light and color that rolls around me." Somewhere he has said that the writer should not dig, and yet again and again we find him resorting to hoe or spade to help him sleep, as well as to smooth his temper: "Yesterday afternoon, I stirred the earth about my shrubs and trees and quarrelled with the pipergrass, and now I have slept, and no longer am morose nor feel twitchings in the muscles of my face when a visitor is by." We welcome these and many another bit of self-analysis: "I was born with a seeing eye and not a helping hand. I can only comfort my friends by thought, and not by love or aid." "I was made a hermit and am content with my lot. I pluck golden fruit from rare meetings with wise men." Margaret Fuller told him he seemed always on stilts: "It is even so. Most of the persons whom I see in my own house I see across a gulf. I cannot go to them nor they come to me.[8] Nothing can exceed the frigidity and labor of my speech with such. You might turn a yoke of oxen between every pair of words; and the behavior is as awkward and proud."

"I would have my book read as I have read my favorite books, not with explosion and astonishment, a marvel and a rocket, but a friendly and agreeable influence stealing like a scent of a flower, or the sight of a new landscape on a traveller. I neither wish to be hated and defied by such as I startle, nor to be kissed and hugged by the young whose thoughts I stimulate."

Here Emerson did center in himself and never apologized. His gospel of self-reliance came natural to him. He was emphatically self, without a trace of selfishness. He went abroad to study himself more than other people—to note the effect of Europe on himself. He says, "I believe it's sound philosophy that wherever we go, whatever we do, self is the sole object we study and learn. Montaigne said himself was all he knew. Myself is much more than I know, and yet I know nothing else." In Paris he wrote to his brother William, "A lecture at the Sorbonne is far less useful to me than a lecture that I write myself"; and as for the literary society in Paris, though he thought longingly of it, yet he said, "Probably in years it would avail me nothing."[9]

The Journals are mainly a record of his thoughts and not of his days, except so far as the days brought him ideas. Here and there the personal element creeps in—some journey, some bit of experience, some visitor, or walks with Channing, Hawthorne, Thoreau, Jones Very, and others; some lecturing experience, his class meetings, his travels abroad and chance meetings with distinguished men. But all the more purely personal element makes up but a small portion of the ten thick volumes of his Journal. Most readers, I fancy, will wish that the proportion of these things were greater. We all have thoughts and speculations of our own, but we can never hear too much about a man's real life.

Emerson stands apart from the other poets and essayists of New England, and of English literature generally, as of another order. He is a reversion to an earlier type, the type of the bard, the skald, the poet-seer. He is the poet and prophet of the moral ideal. His main significance is religious, though nothing could be farther from him than creeds and doctrines, and the whole ecclesiastical formalism. There is an atmosphere of sanctity about him that we do not feel about any other poet and essayist of his time. His poems are the fruit of Oriental mysticism and bardic fervor grafted upon the shrewd, parsimonious, New England puritanic stock. The stress and wild, uncertain[10] melody of his poetry is like that of the wind-harp. No writing surpasses his in the extent to which it takes hold of the concrete, the real, the familiar, and none surpasses his in its elusive, mystical suggestiveness, and its cryptic character. It is Yankee wit and shrewdness on one side, and Oriental devoutness, pantheism, and symbolism on the other. Its cheerful and sunny light of the common day enhances instead of obscures the light that falls from the highest heaven of the spirit. Saadi or Hafiz or Omar might have fathered him, but only a New England mother could have borne him. Probably more than half his poetry escapes the average reader; his longer poems, like "Initial, Dæmonic, and Celestial Love," "Monadnoc," "Merlin," "The Sphinx," "The World-Soul," set the mind groping for the invisible rays of the spectrum of human thought and knowledge, but many of the shorter poems, such as "The Problem," "Each and All," "Sea-Shore," "The Snow-Storm," "Musketaquid," "Days," "Song of Nature," "My Garden," "Boston Hymn," "Concord Hymn," and others, are among the most precious things in our literature.

As Emerson was a bard among poets, a seer among philosophers, a prophet among essayists, an oracle among ethical teachers, so, as I have said, was he a solitary among men. He walked alone. He somewhere refers to his "porcupine impossi[11]bility of contact with men." His very thoughts are not social among themselves, they separate. Each stands alone; often they hardly have a bowing acquaintance; over and over their juxtaposition is mechanical and not vital. The redeeming feature is that they can afford to stand alone, like shafts of marble or granite.

The force and worth of his page is not in its logical texture, but in the beauty and truth of its isolated sentences and paragraphs. There is little inductive or deductive reasoning in his books, but a series of affirmations whose premises and logical connection the reader does not always see.

He records that his hearers found his lectures fine and poetical but a little puzzling. "One thought them as good as a kaleidoscope." The solid men of business said that they did not understand them but their daughters did.

The lecture committee in Illinois in 1856 told him that the people wanted a hearty laugh. "The stout Illinoian," not finding the laugh, "after a short trial walks out of the hall." I think even his best Eastern audiences were always a good deal puzzled. The lecturer never tried to meet them halfway. He says himself of one of his lectures, "I found when I had finished my new lecture that it was a very good house, only the architect had unfortunately omitted the stairs." The absence of the stairs in his house—of an easy entrance[12] into the heart of the subject, and of a few consecutive and leading ideas—will, in a measure, account for the bewilderment of his hearers. When I heard Emerson in 1871 before audiences in Baltimore and Washington, I could see and feel this uncertainty and bewilderment in his auditors.

His lectures could not be briefly summarized. They had no central thought. You could give a sample sentence, but not the one sentence that commanded all the others. Whatever he called it, his theme, as he himself confesses, was always fundamentally the same: "In all my lectures I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man. This the people accept readily enough and even with loud commendations as long as I call the lecture Art or Politics, or Literature, or the Household, but the moment I call it Religion they are shocked, though it be only the application of the same truth which they receive everywhere else to a new class of facts."

Emerson's supreme test of a man, after all other points had been considered, was the religious test: Was he truly religious? Was his pole star the moral law? Was the sense of the Infinite ever with him? But few contemporary authors met his requirements in this respect. After his first visit abroad, when he saw Carlyle, Landor, Coleridge, Wordsworth, and others, he said they were all second-or third-rate men because of their want[13] of the religious sense. They all looked backward to a religion of other ages, and had no faith in a present revelation.

His conception of the divine will as the eternal tendency to the good of the whole, active in every atom, every moment, is one of the thoughts in which religion and science meet and join hands.

In Emerson's Journal one sees the Emersonian worlds in their making—the essays, the addresses, the poems. Here are the nebulæ and star-dust out of which most of them came, or in which their suggestion lies. Now and then there is quite as good stuff as is found in his printed volumes, pages and paragraphs from the same high heaven of æsthetic emotion. The poetic fragments and wholes are less promising, I think, than the prose; they are evidently more experimental, and show the 'prentice hand more.

The themes around which his mind revolved all his life—nature, God, the soul—and their endless variations and implications, recur again and again in each of the ten printed volumes of the Journals. He has new thoughts on Character, Self-Reliance, Heroism, Manners, Experience, Nature, Immortality, and scores of other related subjects every day, and he presents them in new connections and with new images. His mind had[14] marked centrality, and fundamental problems were always near at hand with him. He could not get away from them. He renounced the pulpit and the creeds, not because religion meant less to him, but because it meant more. The religious sentiment, the feeling of the Infinite, was as the sky over his head, and the earth under his feet.

The whole stream of Emerson's mental life apparently flowed through his Journals. They were the repository of all his thoughts, all his speculations, all his mental and spiritual experiences. What a mélange they are! Wise sayings from his wide reading, from intercourse with men, private and public, sayings from his farmer neighbors, anecdotes, accounts of his travels, or his walks, solitary or in the company of Channing, Hawthorne, or Thoreau, his gropings after spiritual truths, and a hundred other things, are always marked by what he says that Macaulay did not possess—elevation of mind—and an abiding love for the real values in life and letters.

Here is the prose origin of "Days": "The days come and go like muffled and veiled figures sent from a distant friendly party, but they say nothing, and if we do not use the gifts they bring, they carry them as silently away." In this brief May entry we probably see the inception of the "Humble-Bee" poem: "Yesterday in the woods I followed the fine humble bee with rhymes and fancies free."[15]

Now and then we come upon the germ of other poems in his prose. Here is a hint of "Each and All" in a page written at the age of thirty-one: "The shepherd or the beggar in his red cloak little knows what a charm he gives to the wide landscape that charms you on the mountain-top and whereof he makes the most agreeable feature, and I no more the part my individuality plays in the All." The poem, his reader will remember, begins in this wise:

In a prose sentence written in 1835 he says: "Nothing is beautiful alone. Nothing but is beautiful in the whole." In the poem above referred to this becomes:

In 1856 we find the first stanza of his 'beautiful "Two Rivers," written in prose form: "Thy voice is sweet, Musketaquid; repeats the music of the rain; but sweeter rivers silent flit through thee as those through Concord plain." The substance of the next four stanzas is in prose form also: "Thou art shut in thy banks; but the stream I love, flows in thy water, and flows through rocks and through the air, and through darkness, and through men, and women. I hear and see the inundation and eternal spending of the stream, in winter and[16] in summer, in men and animals, in passion and thought. Happy are they who can hear it"; and so on. In the poem these sentences become:

It is evident that Emerson was a severe critic of his own work. He knew when he had struck fire, and he knew when he had failed. He was as exacting with himself as with others. His conception of the character and function of the poet was so high that he found the greatest poets wanting. The poet is one of his three or four ever-recurring themes. He is the divine man. He is bard and prophet, seer and savior. He is the acme of human attainment. Verse devoid of insight into the method of nature, and devoid of religious emotion, was to him but as sounding brass and tinkling cymbal. He called Poe "the jingle man" because he was a mere conjurer with words. The intellectual content of Poe's works was negligible. He was a wizard with words and measures, but a pauper in ideas. He did not add to our knowledge, he did not add to our love of anything in nature or in life, he did not contribute to our con[17]tentment in the world—the bread of life was not in him. What was in him was mastery over the architectonics of verse. Emerson saw little in Shelley for the same reason, but much in Herbert and Donne. Religion, in his sense of the term,—the deep sea into which the streams of all human thought empty,—was his final test of any man. Unless there was something fundamental about him, something that savored of the primordial deep of the universal spirit, he remained unmoved. The elemental azure of the great bodies of water is suggestive of the tone and hue Emerson demanded in great poetry. He found but little of it in the men of his time: practically none in the contemporary poets of New England. It was probably something of this pristine quality that arrested Emerson's attention in Walt Whitman's "Leaves of Grass." He saw in it "the Appalachian enlargement of outline and treatment for service to American literature."

Emerson said of himself: "I am a natural reader, and only a writer in the absence of natural writers. In a true time I should never have written." We must set this statement down to one of those fits of dissatisfaction with himself, those negative moods that often came upon him. What he meant by a true time is very obscure. In an earlier age he would doubtless have remained a preacher, like his father and grandfather, but coming under the[18] influence of Goethe, Carlyle, and Wordsworth, and other liberating influences of the nineteenth century, he was bound to be a writer. When he was but twenty-one he speaks of his immoderate fondness for writing. Writing was the passion of his life, his supreme joy, and he went through the world with the writer's eye and ear and hand always on duty. And his contribution to the literature of man's higher moral and æsthetic nature is one of the most valuable of the age in which he lived.

Apart from the account of his travels and other personal experiences, the Journals are mainly made up of discussions of upwards of fifty subjects of general and fundamental interest, ranging from art to war, and looked at from many and diverse points of view. Of these subjects three are dominant, recurring again and again in each volume. These are nature, literature, and religion. Emerson's main interests centered in these themes. Using these terms in their broadest sense, this is true, I think, of all his published books. Emerson was an idealist, first, last, and all the time, and he was a literary artist, or aimed to be, first, last, and all the time, and in the same measure and to the same extent was he a devout religious soul, using the term religion as he sometimes uses it, as a feeling of the Infinite.[19]

There are one hundred and seventy-six paragraphs, long and short, given to literature and art, and one hundred and sixty given to religious subjects, and over thirty given to nature. It is interesting to note that he devotes more paragraphs to woman than to man; and more to society than to solitude, though only to express his dislike of the former and his love for the latter. There are more thoughts about science than about metaphysics, more about war than about love, more about poetry than about philosophy, more on beauty than on knowledge, more on walking than on books. There are three times as many paragraphs on nature (thirty-three) as on the Bible, all of which is significant of his attitude of mind.

Emerson was a preacher without a creed, a scholar devoted to super-literary ends, an essayist occupied with thoughts of God, the soul, nature, the moral law—always the literary artist looking for the right word, the right image, but always bending his art to the service of religious thought. He was one of the most religious souls of his country and time, or of any country and time, yet was disowned by all the sects and churches of his time. He made religion too pervasive, and too inclusive to suit them; the stream at once got out of its banks and inundated all their old landmarks. In the last analysis of his thought, his ultimate theme was God, and yet he never allowed himself to at[20]tempt any definite statement about God—refusing always to discuss God in terms of human personality. When Emerson wrote "Representative Men" he felt that Jesus was the Representative Man whom he ought to sketch, "but the task required great gifts—steadiest insight and perfect temper; else the consciousness of want of sympathy in the audience would make one petulant and sore in spite of himself."

There are few great men in history or philosophy or literature or poetry or divinity whose names do not appear more or less frequently in the Journals. For instance, in the Journal of 1864 the names or works of one hundred and seventeen men appear, ranging from Zeno to Jones Very. And this is a fair average. Of course the names of his friends and contemporaries appear the most frequently. The name that recurs the most often is that of his friend and neighbor Thoreau. There are ninety-seven paragraphs in which the Hermit of Walden is the main or the secondary figure. He discusses him and criticizes him, and quotes from him, always showing an abiding interest in, and affection for, him. Thoreau was in so many ways so characteristically Emersonian that one wonders what influence it was in the place or time that gave them both, with their disparity of ages, so nearly the same stamp. Emerson is by far the more imposing figure, the broader, the wiser, the more[21] tolerant, the more representative; he stood four-square to the world in a sense that Thoreau did not. Thoreau presented a pretty thin edge to the world. If he stood broadside to anything, it was to nature. He was undoubtedly deeply and permanently influenced by Emerson both in his mental habits and in his manner of life, yet the main part of him was original and unadulterated Thoreau. His literary style is in many respects better than that of Emerson; its logical texture is better; it has more continuity, more evolution, it is more flexible and adaptive; it is the medium of a lesser mind, but of a mind more thoroughly imbued with the influence of the classical standards of modern literature. I believe "Walden" will last as long as anything Emerson has written, if not longer. It is the fruit of a sweeter solitude and detachment from the world than Emerson ever knew, a private view of nature, and has a fireside and campside quality that essays fashioned for the lecture platform do not have. Emerson's pages are more like mosaics, richly inlaid with gems of thought and poetry and philosophy, while Thoreau's are more like a closely woven, many-colored textile.

Thoreau's "Maine Woods" I look upon as one of the best books of the kind in English literature. It has just the right tone and quality, like Dana's "Two Years Before the Mast"—a tone and quality that sometimes come to a man when he makes[22] less effort to write than to see and feel truly. He does not aim to exploit the woods, but to live with them and possess himself of their spirit. The Cape Cod book also has a similar merit; it almost leaves a taste of the salt sea spray upon your lips. Emerson criticizes Thoreau freely, and justly, I think. As a person he lacked sweetness and winsomeness; as a writer he was at times given to a meaningless exaggeration.

Henry Thoreau sends me a paper with the old fault of unlimited contradiction. The trick of his rhetoric is soon learned: it consists in substituting for the obvious word and thought its diametrical antagonist. He praises wild mountains and winter forests for their domestic air; snow and ice for their warmth; villagers and wood-choppers for their urbanity, and the wilderness for resembling Rome and Paris. With the constant inclination to dispraise cities and civilization, he yet can find no way to know woods and woodmen except by paralleling them with towns and townsmen. Channing declared the piece is excellent: but it makes me nervous and wretched to read it, with all its merits.

I told Henry Thoreau that his freedom is in the form, but he does not disclose new matter. I am very familiar with all his thoughts,—they are my own quite originally drest. But if the question be, what new ideas has he thrown into circulation, he has not yet told what that is which he was created to say. I said to him what I often feel, I only know three persons who seem to me fully to see this law of reciprocity or compensation—himself, Alcott, and myself: and 't is odd that we should all be neighbors, for in the wide land or the wide earth I do not know another who[23] seems to have it as deeply and originally as these three Gothamites.

A remark of Emerson's upon Thoreau calls up the image of John Muir to me: "If I knew only Thoreau, I should think coöperation of good men impossible. Must we always talk for victory, and never once for truth, for comfort, and joy?" Then, after crediting Thoreau with some admirable gifts,—centrality, penetration, strong understanding,—he proceeds to say, "all his resources of wit and invention are lost to me, in every experiment, year after year, that I make to hold intercourse with his mind. Always some weary captious paradox to fight you with, and the time and temper wasted."

Emerson met John Muir in the Yosemite in 1871 and was evidently impressed with him. Somewhere he gives a list of his men which begins with Carlyle and ends with Muir. Here was another man with more character than intellect, as Emerson said of Carlyle, and with the flavor of the wild about him. Muir was not too compliant and deferential. He belonged to the sayers of No. Contradiction was the breath of his nostrils. He had the Scottish chariness of bestowing praise or approval, and could surely give Emerson the sense of being met which he demanded. Writing was irksome to Muir as it was to Carlyle, but in monologue, in an attentive company, he shone;[24] not a great thinker, but a mind strongly characteristic. His philosophy rarely rose above that of the Sunday school, but his moral fiber was very strong, and his wit ready and keen. In conversation and in daily intercourse he was a man not easily put aside. Emerson found him deeply read in nature lore and with some suggestion about his look and manner of the wild and rugged solitude in which he lived so much.

Emerson was alive to everything around him; every object touched some spring in his mind; the church spire, the shadows on the windows at night, the little girl with her pail of whortleberries, the passing bee, bird, butterfly, the clouds, the streams, the trees—all found his mind open to any suggestion they might make. He is intent on the now and the here. He listens to every newcomer with an expectant air. He is full of the present. I once saw him at West Point during the June examinations. How alert and eager he was! The bored and perfunctory air of his fellow members on the Board of Visitors contrasted sharply with his active, expectant interest.

He lived absolutely in his own day and generation, and no contemporary writer of real worth escaped his notice. He is never lavish in his praise, but is for the most part just and discrimi[25]nating. Walt Whitman is mentioned only thrice in the Journals, Lowell only twice, Longfellow once or twice, Matthew Arnold three times, but Jones Very is quoted and discussed sixteen times. Very was a poet who had no fast colors; he has quite faded out in our day.

Of Matthew Arnold Emerson says: "I should like to call attention to the critical superiority of Arnold, his excellent ear for style, and the singular poverty of his poetry, that in fact he has written but one poem, 'Thyrsis,' and that on an inspiration borrowed from Milton." Few good readers, I think, will agree with Emerson about the poverty of Arnold's poetry. His "Dover Beach" is one of the first-rate poems in English literature. Emerson has words of praise for Lowell—thinks the production of such a man "a certificate of good elements in the soil, climate, and institutions of America," but in 1868 he declares that his new poems show an advance "in talent rather than in poetic tone"; that the advance "rather expresses his wish, his ambition, than the uncontrollable interior impulse which is the authentic mark of a new poem, and which is unanalysable, and makes the merit of an ode of Collins, or Gray, or Wordsworth, or Herbert, or Byron." He evidently thought little of Lowell's severe arraignment of him in a college poem which he wrote soon after the delivery of the famous "Divinity School[26] Address." The current of religious feeling in Cambridge set so strongly against Emerson for several years that Lowell doubtless merely reflected it. Why did he not try to deflect it, or to check it? And yet, when Emerson's friends did try to defend him, it was against his will. He hated to be defended in a newspaper: "As long as all that is said is against me I feel a certain austere assurance of success, but as soon as honeyed words of praise are spoken for me I feel as one that lies unprotected before his enemies."

Next to Thoreau, Emerson devotes to Alcott more space in his Journals than to any other man. It is all telling interpretation, description, and criticism. Truly, Alcott must have had some extraordinary power to have made such a lasting impression upon Emerson. When my friend Myron Benton and I first met Emerson in 1863 at West Point, Emerson spoke of Alcott very pointedly, and said we should never miss a chance to hear his conversation, but that when he put pen to paper all his inspiration left him. His thoughts faded as soon as he tried to set them down. There must have been some curious illusion about it all on the part of Emerson, as no fragment of Alcott's wonderful talk worth preserving has come down to us. The waters of the sea are blue, but not in the pailful. There must have been something analogous in Alcott's conversations, some total effect[27] which the details do not justify, or something in the atmosphere which he created, that gave certain of his hearers the conviction that they were voyaging with him through the celestial depths.

It was a curious fact that Alcott "could not recall one word or part of his own conversation, or of any one's, let the expression be never so happy." And he seems to have hypnotized Emerson in the same way. "He made here some majestic utterances, but so inspired me that even I forgot the words often." "Olympian dreams," Emerson calls his talk—moonshine, it appears at this distance.

"His discourse soars to a wonderful height," says Emerson, "so regular, so lucid, so playful, so new and disdainful of all boundaries of tradition and experience, that the hearers seem no longer to have bodies or material gravity, but almost they can mount into the air at pleasure, or leap at one bound out of this poor solar system. I say this of his speech exclusively, for when he attempts to write, he loses, in my judgment, all his power, and I derive more pain than pleasure from the perusal." Some illusion surely that made the effort to report him like an attempt to capture the rainbow, only to find it common water.

In 1842 Emerson devotes eight pages in his Journal to an analysis of Alcott, and very masterly they are. He ends with these sentences: "This[28] noble genius discredits genius to me. I do not want any more such persons to exist."

"When Alcott wrote from England that he was bringing home Wright and Lane, I wrote him a letter which I required him to show them, saying that they might safely trust his theories, but that they should put no trust whatever in his statement of facts. When they all arrived here—he and his victims—I asked them if he showed them the letter; they answered that he did; so I was clear."

Another neighbor who greatly impressed Emerson, and of whom he has much to say, was Father Taylor, the sailor preacher of Boston. There is nothing better in the Journals than the pages devoted to description and analysis of this remarkable man. To Emerson he suggested the wealth of Nature. He calls him a "godly poet, the Shakespear of the sailor and the poor." "I delight in his great personality, the way and sweep of the man which, like a frigate's way, takes up for the time the centre of the ocean, paves it with a white street, and all the lesser craft 'do curtsey to him, do him reverence.'" A man all emotion, all love, all inspiration, but, like Alcott, impossible to justify your high estimate of by any quotation. His power was all personal living power, and could not be transferred to print. The livid embers of his discourse became dead charcoal when reported by another, or, as Emerson more happily puts it,[29] "A creature of instinct, his colors are all opaline and dove's-neck-lustre and can only be seen at a distance. Examine them, and they disappear." More exactly they are visible only at a certain angle. Of course this is in a measure true of all great oratory—it is not so much the words as the man.

Speaking of Father Taylor in connection with Alcott, Emerson says that one was the fool of his ideas, and the other of his fancy.

An intellectual child of Emerson's was Ellery Channing, but he seems to have inherited in an exaggerated form only the faults of his father. Channing appears to have been a crotchety, disgruntled person, always aiming at walking on his head instead of on his heels. Emerson quotes many of his sayings, not one of them worth preserving, all marked by a kind of violence and disjointedness. They had many walks together.

Emerson was so fond of paradoxes and extreme statements that both Channing and Thoreau seem to have vied with each other in uttering hard or capricious sayings when in his presence. Emerson catches at a vivid and picturesque statement, if it has even a fraction of truth in it, like a fly-catcher at a fly.

A fair sample of Channing's philosophy is the following: "He persists in his bad opinion of orchards and farming, declares that the only success he ever[30] had with a farmer was that he once paid a cent for a russet apple; and farming, he thinks, is an attempt to outwit God with a hoe; that they plant a great many potatoes with much ado, but it is doubtful if they ever get the seed back." Channing seems to have dropped such pearls of wisdom as that all along the road in their walks! Another sample of Channing's philosophy which Emerson thinks worthy of quoting. They were walking over the fields in November. Channing complained of the poverty of invention on the part of Nature: "'Why, they had frozen water last year; why should they do it again? Therefore it was so easy to be an artist, because they do the same thing always,' and therefore he only wants time to make him perfect in the imitation."

Emerson was occupied entirely with the future, as Carlyle was occupied entirely with the past. Emerson shared the open expectation of the new world, Carlyle struggled under the gloom and pessimism of the old—a greater character, but a far less lambent and helpful spirit. Emerson seems to have been obsessed with the idea that a new and greater man was to appear. He looked into the face of every newcomer with an earnest, expectant air, as if he might prove to be the new man: this thought inspires the last stanzas of his "Song of Nature":[31]

Emerson was under no illusion as to the effect of distance. He knew the past was once the present, and that if it seemed to be transformed and to rise into cloud-land behind us, it was only the enchantment of distance—an enchantment which men have been under in all ages. The everyday, the near-at-hand, become prosaic; there is no room for the alchemy of time and space to work in. It has been said that all martyrdoms looked mean in the suffering. Holy ground is not holy when we walk upon it. The now and the here seem cheap and commonplace. Emerson knew that "a score of airy miles will smooth rough Monadnoc to a gem," but he knew also that it would not change the character of Monadnoc. He knew that the past and the present, the near and the far, were made of one stuff. He united the courage of science with the sensibility of poetry. He would not be defrauded of the value of the present hour, or of the thoughts which he and other men think, or of the lives which they live to-day. "I will tell you how you can enrich me—if you will recommend to-day to me." His doctrine of self-reliance,[32] which he preached in season and out of season, was based upon the conviction that Nature and the soul do not become old and outworn, that the great characters and great thoughts of the past were the achievements of men who trusted themselves before custom or law. The sun shines to-day; the constellations hang there in the heavens the same as of old. God is as near us as ever He was—why should we take our revelations at second hand? No other writer who has used the English language has ever preached such a heroic doctrine of self-trust, or set the present moment so high in the circle of the years, in the diadem of the days.

It is an old charge against Emerson that he was deficient in human sympathy. He makes it against himself; the ties of association which most persons find so binding seemed to hold him very lightly. There was always a previous question with him—the moral value of one's associations. Unless you sicken and die to some purpose, why such an ado about it? Unless the old ruin of a house harbored great men and great women, or was the scene of heroic deeds, why linger around it? The purely human did not appeal to him; history interested him only as it threw light upon to-day. History is a record of the universal mind; hence of your mind, of my mind—"all the facts of history preëxist in the mind as laws." "What Plato thought, every man may think. What a[33] saint has felt, he may feel; what at any time has befallen any man, he can understand." "All that Shakespear says of the king, yonder slip of a boy that reads in the corner feels to be true of himself"; and so on, seeing in history only biography, and interested in the past only as he can link it with the present. Always an intellectual interest, never a human or an emotional one. His Journal does not reveal him going back to the old places, or lingering fondly over the memories of his youth. He speaks of his "unpleasing boyhood," of his unhappy recollections, etc., not because of unkindness or hardships experienced, but because of certain shortcomings or deficiencies of character and purpose, of which he is conscious—"some meanness," or "unfounded pride" which may lower him in the opinion of others. Pride, surely, but not ignoble pride.

Emerson's expectation of the great poet, the great man, is voiced in his "Representative Men": "If the companions of our childhood should turn out to be heroes, and their condition regal, it would not surprise us." On the contrary, I think it would surprise most of us very much. It is from the remote, the unfamiliar, that we expect great things. We have no illusions about the near-at-hand. But with Emerson the contrary seems to have been the case. He met the new person or took up the new volume with a thrill of expectancy, a condition[34] of mind which often led him to exaggerate the fact, and to give an undue bias in favor of the novel, the audacious, the revolutionary. His optimism carried him to great lengths. Many of the new stars in his literary firmament have quite faded out—all of them, I think, but Walt Whitman. It was mainly because he was so full of faith in the coming man that he gave, offhand, such a tremendous welcome to "Leaves of Grass"—a welcome that cooled somewhat later, when he found he had got so much more of the unconventional and the self-reliant than he had bargained for. I remember that when I spoke of Walt Whitman to him in Washington in 1871 or '72, he said he wished Whitman's friends would "quarrel" with him more about his poems, as some years earlier he himself had done, on the occasion when he and Whitman walked for hours on Boston Common, he remonstrating with Whitman about certain passages in "Leaves of Grass" which he tried in vain to persuade him to omit in the next edition. Whitman would persist in being Whitman. Now, counseling such a course to a man in an essay on "Self-Reliance" is quite a different thing from entirely approving of it in a concrete example.

In 1840 Emerson writes: "A notice of modern literature ought to include (ought it not?) a notice of Carlyle, of Tennyson, of Landor, of Bettina, of Sampson Reed." The first three names surely, but[35] who is Bettina, the girl correspondent of Goethe, that she should go in such a list? Reed, we learn, was a Boston bank clerk, and a Swedenborgian, who wrote a book on the growth of the mind, from which Emerson quotes, and to which he often alludes, a book that has long been forgotten; and is not Bettina forgotten also?

Emerson found more in Jones Very than has any one else; the poems of Very that he included in "Parnassus" have little worth. A comparatively unknown and now forgotten English writer also moved Emerson unduly. Listen to this: "In England, Landor, De Quincey, Carlyle, three men of original literary genius; but the scholar, the catholic, cosmic intellect, Bacon's own son, the Lord Chief Justice on the Muse's Bench is"—who do you think, in 1847?—"Wilkinson"! Garth Wilkinson, who wrote a book on the human body. Emerson says of him in "English Traits": "There is in the action of his mind a long Atlantic roll, not known except in deepest waters, and only lacking what ought to accompany such powers, a manifest centrality." To bid a man's stock up like that may not, in the long run, be good for the man, but it shows what a generous, optimistic critic Emerson was.

In his published works Emerson is chary of the personal element; he says: "We can hardly speak[36] of our own experiences and the names of our friends sparingly enough." In his books he would be only an impersonal voice; the man Emerson, as such, he hesitated to intrude. But in the Journals we get much more of the personal element, as would be expected. We get welcome glimpses of the man, of his moods, of his diversions, of his home occupations, of his self-criticism. We see him as a host, as a lecturer, as a gardener, as a member of a rural community. We see him in his walks and talks with friends and neighbors—with Alcott, Thoreau, Channing, Jones Very, Hawthorne, and others—and get snatches of the conversations. We see the growth of his mind, his gradual emancipation from the bondage of the orthodox traditions.

Very welcome is the growth of Emerson's appreciation of Wordsworth. As a divinity student he was severe in his criticism of Wordsworth, but as his own genius unfolded more and more he saw the greatness of Wordsworth, till in middle life he pronounced his famous Ode the high-water mark of English literature. Yet after that his fondness for a telling, picturesque figure allows him to inquire if Wordsworth is not like a bell with a wooden tongue. All this is an admirable illustration of his familiar dictum: "Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict everything you say to-day."[37]

In the Journals we see Emerson going up and down the country in his walks, on his lecture tours in the West, among his neighbors, wherever and whenever he goes as alert and watchful as a sportsman. He was a sportsman of a new kind; his game was ideas. He was always looking for hints and images to aid him in his writings. He was like a bird perpetually building a nest; every moment he wanted new material, and everything that diverted him from his quest was an unwelcome interruption. He had no great argument to build, no system of philosophy to organize and formulate, no plot, like a novelist, to work out, no controversy on hand—he wanted pertinent, concrete, and striking facts and incidents to weave in his essay on Fate, or Circles, or Character, or Farming, or Worship, or Wealth—something that his intuitive and disjointed habit of thought could seize upon and make instant use of.

We see him walking in free converse with his friends and neighbors, receiving them in his own house, friendly and expectant, but always standing aloof, never giving himself heartily to them, exchanging ideas with them across a gulf, prizing their wit and their wisdom, but cold and reserved toward them personally, destitute of all feeling of comradeship, an eye, an ear, a voice, an intellect, but rarely, or in a minor degree, a heart, or a feeling of fellowship—a giving and a taking quite above[38] and beyond the reach of articulate speech. When they had had their say, he was done with them. When you have found a man's limitations, he says, it is all up with him. After your friend has fired his shot, good-by. The pearl in the oyster is what is wanted, and not the oyster. "If I love you, what is that to you?" is a saying that could have been coined only in Concord. It seems to me that the basis of all wholesome human attachment is character, not intellect. Admiration and love are quite different things. Transcendental friendships seem to be cold, bloodless affairs.

One feels as if he wanted to squeeze or shake Emerson to see if he cannot get some normal human love out of him, a love that looks for nothing beyond love, a love which is its own excuse for being, a love that is not a bargain—simple, common, disinterested human love. But Emerson said, "I like man but not men."

"You would have me love you," he writes in his Journal. "What shall I love? Your body? The supposition disgusts you. What you have thought and said? Well, whilst you were thinking and saying them, but not now. I see no possibility of loving anything but what now is, and is becoming; your courage, your enterprise, your budding affection, your opening thought, your prayer, I can love—but what else?"

Can you not love your friend for himself alone,[39] for his kinship with you, without taking an inventory of his moral and intellectual qualities; for something in him that makes you happy in his presence? The personal attraction which Whitman felt between himself and certain types of men, and which is the basis of most manly friendships, Emerson probably never felt. One cannot conceive of him as caring deeply for any person who could not teach him something. He says, "I speculate on virtue, not burn with love." Again, "A rush of thoughts is the only conceivable prosperity that can come to me." Pure intellectual values seem alone to have counted with Emerson and his followers. With men his question was, "What can you teach me?" With Nature, "What new image or suggestion have you got for me to-day?" With science, "What ethical value do your facts hold?" With natural history, "Can I translate your facts and laws into my supernatural history?" With civil history, "Will your record help me to understand my own day and land?" The quintessence of things was what he always sought.

"We cannot forgive another for not being ourselves," Emerson wrote in 1842, and then added, "We lose time in trying to be like others." One is reminded of passages in the Emerson-Carlyle correspondence, wherein each tried to persuade the other to be like himself. Carlyle would have Emerson "become concrete and write in prose the[40] straightest way," would have him come down from his "perilous altitude," "soliloquizing on the eternal mountain-tops only, in vast solitude, where men and their affairs lie all hushed in a very dim remoteness and only the man and the stars and the earth are visible—come down into your own poor Nineteenth Century, its follies, its maladies, its blind, or half-blind but gigantic toilings, its laughter and its tears, and try to evolve in some measure the hidden God-like that lies in it." "I wish you would take an American hero, one whom you really love, and give us a History of him—make an artistic bronze statue (in good words) of his Life and him!" Emerson's reply in effect is, Cremate your heroes and give me their ashes—give me "the culled results, the quintessence of private conviction, a liber veritatis, a few sentences, hints of the final moral you draw from so much penetrating inquest into past and present men."

In reply to Carlyle's criticism of the remote and abstract character of his work, Emerson says, "What you say now and heretofore respecting the remoteness of my writing and thinking from real life, though I hear substantially the same criticism made by my countrymen, I do not know what it means. If I can at any time express the law and the ideal right, that should satisfy me without measuring the divergence from it of the last act of Congress."[41]

Emerson's love of nature was one of his ruling passions. It took him to the country to live, it led him to purchase Walden Pond and the Walden woods; it led him forth upon his almost daily walks, winter and summer, to the fields and the woods. His was the love of the poet and the idealist, of the man who communes with Nature, and finds a moral and an intellectual tonic in her works. The major part of his poetry is inspired by Nature. He complains of Tennyson's poetry that it has few or no wood notes. His first book, "Nature," is steeped in religious and poetic emotion. He said in his Journal in 1841: "All my thoughts are foresters. I have scarce a day-dream on which the breath of the pines has not blown, and their shadows waved. Shall I not then call my little book Forest Essays?" He finally called it "Nature." He loves the "hermit birds that harbor in the woods. I can do well for weeks with no other society than the partridge and the jay, my daily company."

"I have known myself entertained by a single dew-drop, or an icicle, by a liatris, or a fungus, and seen God revealed in the shadow of a leaf." He says that going to Nature is more than a medicine, it is health. "As I walked in the woods I felt what I often feel, that nothing can befall me in life, no calamity, no disgrace (leaving me my[42] eyes) to which Nature will not offer a sweet consolation. Standing on the bare ground with my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into the infinite space, I became happy in my universal relations." This sentiment of his also recalls his lines:

If life were long enough, among my thousand and one works should be a book of Nature whereof Howitt's Seasons should not be so much the model as the parody. It should contain the natural history of the woods around my shifting camp for every month in the year. It should tie their astronomy, botany, physiology, meteorology, picturesque, and poetry together. No bird, no bug, no bud, should be forgotten on his day and hour. To-day the chickadees, the robins, bluebirds and song-sparrows sang to me. I dissected the buds of the birch and the oak; in every one of the last is a star. The crow sat above as idle as I below. The river flowed brimful, and I philosophised upon this composite, collective beauty which refuses to be analysed. Nothing is beautiful alone. Nothing but is beautiful in the whole. Learn the history of a craneberry. Mark the day when the pine cones and acorns fall.

I go out daily and nightly to feed my eyes on the horizon and the sky, and come to feel the want of this scope as I do of water for my washing.

What learned I this morning in the woods, the oracular woods? Wise are they, the ancient nymphs; pleasing, sober, melancholy truth say those untameable savages, the pines.

He frequently went to Walden Pond of an afternoon and read Goethe or some other great author.

There was an element of mysticism in Emerson's love of nature as there is in that of all true nature-lovers. None knew better than he that nature is not all birds and flowers. His love of nature was that of the poet and artist, and not that of the scientist or naturalist.

"I tell you I love the peeping of the Hyla in a pond in April, or the evening cry of the whippoorwill, better than all the bellowing of all the Bulls of Bashan, or all the turtles of all Palestine."

Any personal details about his life which Emerson gives us are always welcome. We learn that his different winter courses of lectures in Boston, usually ten of them, were attended on an average by about five hundred persons, and netted him about five hundred dollars.

When he published a new volume, he was very liberal with presentation copies. Of his first volume of poems, published in 1846, he sent eighty copies to his friends. When "May-Day" was published in 1867, he sent fifty copies to friends; one of them went to Walt Whitman. I saw it the day it came. It was in a white dress (silk, I think); very beautiful. He sent a copy of his first volume of "Nature" to Landor. One would like to know what Landor said in reply. The copy he sent to Carlyle I saw in the Scot's library, in Cheyne Row, in 1871.[44]

Emerson was so drawn to the racy and original that it seems as if original sin had a certain fascination for him. The austere, the Puritanical Emerson, the heir of eight generations of clergy-men, the man who did not like to have Frederika Bremer play the piano in his house on Sunday, seems at times to covet the "swear-words" of the common people. They itch at his ears, they have flavor and reality. He sometimes records them in his Journal; for example, this remark of the Canadian wood-chopper who cut wood for his neighbor—he preferred to work by the job rather than by the day—the days were "so damned long!"

The mob, Emerson says, is always interesting: "A blacksmith, a truckman, a farmer, we follow into the bar-room and watch with eagerness what they shall say." "Cannot the stinging dialect of the sailor be domesticated?" "My page about Consistency would be better written, 'Damn Consistency.'" But try to fancy Emerson swearing like the men on the street! Once only he swore a sacred oath, and that he himself records: it was called out by the famous, and infamous, Fugitive Slave Law which made every Northern man hound and huntsman for the Southern slave-driver. "This filthy enactment," he says, "was made in the Nineteenth Century by men who could read and write. I will not obey it, by God!"[45]

Evidently the best thing the laboring people had to offer Emerson was their racy and characteristic speech. When one of his former neighbors said of an eclipse of the sun that it looked as if a "nigger" was poking his head into the sun, Emerson recorded it in his Journal. His son reports that Emerson enjoyed the talk of the stable-men and used to tell their anecdotes and boasts of their horses when he came home; for example, "In the stable you'd take him for a slouch, but lead him to the door, and when he lifts up his eyes, and looks abroad,—by thunder! you'd think the sky was all horse." Such surprises and exaggerations always attracted him, unless they took a turn that made him laugh. He loved wit with the laugh taken out of it. The genial smile and not uproarious laughter suited his mood best.

He was a lover of quiet, twinkling humor. Such humor gleams out often in his Journal. It gleams in this passage about Dr. Ripley: "Dr. Ripley prays for rain with great explicitness on Sunday, and on Monday the showers fell. When I spoke of the speed with which his prayers were answered, the good man looked modest." There is another prayer-for-rain story that he enjoys telling: "Dr. Allyne, of Duxbury, prayed for rain, at church. In the afternoon the boys carried umbrellas. 'Why?' 'Because you prayed for rain.' 'Pooh! boys! we always pray for rain: it's customary.'"[46]

At West Point he asked a lieutenant if they had morning prayers at college. "We have reveillé beat, which is the same thing."

He tells with relish the story of a German who went to hire a horse and chaise at a stable in Cambridge. "Shall I put in a buffalo?" inquired the livery-man. "My God! no," cried the astonished German, "put in a horse."

Emerson, I am sure, takes pleasure in relating a characteristic story of Dr. Ripley and a thunder-shower: "One August afternoon, when I was in the hayfield helping him with his man to rake up his hay, I well remember his pleading, almost reproachful looks at the sky when the thunder gust was coming up to spoil the hay. He raked very fast, then looked at the clouds and said, 'We are in the Lord's hands, mind your rake, George! we are in the Lord's hands,' and seemed to say, 'You know me, the field is mine—Dr. Ripley's—thine own servant.'"

The stories Emerson delighted in were all rich in this quiet humor. I heard of one he used to tell about a man who, when he went to his club at night, often lingered too long over his cups, and came home befuddled in the small hours, and was frequently hauled over the coals by his wife. One night he again came home late, and was greeted with the usual upbraiding in the morning. "It was not late," he said, "it was only one o'clock."[47] "It was much later than that," said the wife. "It was one o'clock," repeated the man; "I heard it strike one three or four times!"

Another good Emersonian story, though I do not know that he ever heard it, is that of an old woman who had a farm in Indiana near the Michigan line. The line was resurveyed, and the authorities set her farm in Michigan. The old lady protested—she said it was all she could do to stand the winters of Indiana, she could never stand those of Michigan!

Cannot one see a twinkle in Emerson's eye when he quotes his wife as saying that "it is wicked to go to church on Sunday"? Emerson's son records that his father hated to be made to laugh, as he could not command his face well. Hence he evidently notes with approval another remark of his wife's: "A human being should beware how he laughs, for then he shows all his faults." What he thought of the loud, surprising laugh with which Carlyle often ended his bitter sentences, I do not know that he records. Its meaning to Carlyle was evidently, "Oh! what does it all matter?" If Emerson himself did not smile when he wrote the sentence about "a maiden so pure that she exchanged glances only with the stars," his reader, I am sure, will.

Emerson evidently enjoyed such a story as this which was told him by a bishop: There was a dis[48]pute in a vestry at Providence between two hot church-members. One said at last, "I should like to know who you are"—

"Who I am?" cried the other,—"who I am! I am a humble Christian, you damned old heathen, you!"

The minister whom he heard say that "nobody enjoyed religion less than ministers, as none enjoyed food so little as cooks," must have provoked the broadest kind of a smile.

Although one of Emerson's central themes in his Journals was his thought about God, or his feeling for the Infinite, he never succeeded in formulating his ideas on the subject and could not say what God is or is not. At the age of twenty-one he wrote in his Journal, "I know that I know next to nothing." A very unusual, but a very promising frame of mind for a young man. "It is not certain that God exists, but that He does not is a most bewildering and improbable Chimera."

A little later he wrote: "The government of God is not a plan—that would be Destiny, [or we may say Calvinism,] it is extempore."

He quotes this from Plotinus: "Of the Unity of God, nothing can be predicated, neither being, nor essence, nor life, for it is above all these."

It was a bold saying of his that "God builds his temple in the heart on the ruins of churches and religion."[49]

"A great deal of God in the universe," he says, "but not available to us until we can make it up into a man."

But if asked, what makes it up into a man? why does it take this form? he would have been hard put to it for an answer.

Persons who assume to know all about God, as if He lived just around the corner, as Matthew Arnold said, will not find much comfort in Emerson's uncertainty and blind groping for adequate expression concerning Him. How can we put the All, the Eternal, in words? How can we define the Infinite without self-contradiction? Our minds are cast in the mould of the finite; our language is fashioned from our dealings with a world of boundaries and limitations and concrete objects and forces. How much can it serve us in dealing with a world of opposite kind—with the Whole, the Immeasurable, the Omnipresent, and Omnipotent? Of what use are our sounding-lines in a bottomless sea? How are we to apply our conceptions of personality to the all-life, to that which transcends all limitations, to that which is everywhere and yet nowhere? Shall we assign a local habitation and a name to the universal energy? As the sunlight puts out our lamp or candle, so our mental lights grow pale in the presence of the Infinite Light. We can deal with the solid bodies on the surface of the earth, but the earth as[50] a sphere in the heavens baffles us. All our terms of over and under, up and down, east and west, and the like, fail us. You may go westward around the world and return to your own door coming from the east. The circle is a perpetual contradiction, the sphere a surface without boundaries, a mass without weight. When we ascribe weight to the earth, we are trying it by the standards of bodies on its surface—the pull of the earth is the measure of their weight; but the earth itself—what pulls that? Only some larger body can pull that, and the adjustment of the system is such that the centripetal and centrifugal forces balance each other, and the globes float as lightly as any feather.

Emerson said he denied personality to God because it is too little, not too much. If you ascribe personality to God, it is perfectly fair to pester you with questions about Him. Where is He? How long has He been there? What does He do? Personality without place, or form, or substance, or limitation is a contradiction of terms. We are the victims of words. We get a name for a thing and then invent the thing that fits it. All our names for the human faculties, as the will, the reason, the understanding, the imagination, conscience, instincts, and so on, are arbitrary divisions of a whole, to suit our own convenience, like the days of the week, or the seasons of the year. Out[51] of unity we make diversity for purposes of our practical needs. Thought tends to the one, action to the many. We must have small change for everything in the universe, because our lives are made up of small things. We must break wholes up into fractions, and then seek their common multiple. Only thus can we deal with them. We deal with God by limiting Him and breaking Him up into his attributes, or by conceiving Him under the figure of the Trinity. He is thus less baffling to us. We can handle Him the better. We make a huge man of Him and then try to dodge the consequences of our own limitations.

All these baffling questions pressed hard upon Emerson. He could not do without God in nature, and yet, like most of us, he could not justify himself until he had trimmed and cut away a part of nature. God is the All, but the All is a hard mass to digest. It means hell as well as heaven, demon as well as seraph, geology as well as biology, devolution as well as evolution, earthquake as well as earth tranquillity, cyclones as well as summer breezes, the jungle as well as the household, pain as well as pleasure, death as well as life. How are you to reconcile all these contradictions?

Emerson said that nature was a swamp with flowers and birds on the borders, and terrible things in the interior. Shall we have one God for the fair things, and another God for the terrible things?[52]

"Nature is saturated with deity," he says, the terrific things as the beatific, I suppose. "A great deal of God in the universe," he again says, "but not valuable to us till we can make it up into a man." And when we make it up into a man we have got a true compendium of nature; all the terrific and unholy elements—fangs and poisons and eruptions, sharks and serpents—have each and all contributed something to the make-up. Man is nature incarnated, no better, no worse.

But the majority of mankind who take any interest in the God-question at all will probably always think of the Eternal in terms of man, and endow Him with personality.

One feels like combating some of Emerson's conclusions, or, at least, like discounting them. His refusal to see any value in natural science as such, I think, shows his limitations. "Natural history," he says, "by itself has no value; it is like a single sex; but marry it to human history and it is poetry. Whole Floras, all Linnæus', and Buffon's volumes contain not one line of poetry." Of course he speaks for himself. Natural facts, scientific truth, as such, had no interest to him. One almost feels as if this were idealism gone to seed.

"Shall I say that the use of Natural Science seems merely 'ancillary' to Morals? I would learn the law of the defraction of a ray because[53] when I understand it, it will illustrate, perhaps suggest, a new truth in ethics." Is the ethical and poetic value of the natural sciences, then, their main or only value to the lay mind? Their technical details, their tables and formulæ and measurements, we may pass by, but the natural truths they disclose are of interest to the healthy mind for their own sake. It is not the ethics of chemical reactions and combinations—if there be ethics in them—that arrests our attention, but the light they throw on the problem of how the world was made, and how our own lives go on. The method of Nature in the physical world no doubt affords clues to the method of Nature in the non-physical, or supersensuous world. But apart from that, it is incredible that a mind like Emerson's took no interest in natural knowledge for its own sake. The fact that two visible and inodorous gases like hydrogen and oxygen—one combustible and the other the supporter of combustion—when chemically combined produce water, which extinguishes fire, is intensely interesting as affording us a glimpse of the contradictions and paradoxes that abound everywhere in Nature's methods. If there is any ethics or any poetry in it, let him have it who can extract it. The great facts of nature, such as the sphericity of the cosmic bodies, their circular motions, their mutual interdependence, the unprovable ether in which[54] they float, the blue dome of the sky, the master currents of the ocean, the primary and the secondary rocks, have an intellectual value, but how they in any way illustrate the moral law is hard to see. The ethics, or right and wrong, of attraction and repulsion, of positive and negative, have no validity outside the human sphere. Might is right in Nature, or, rather, we are outside the standards of right and wrong in her sphere. Scientific knowledge certainly has a poetic side to it, but we do not go to chemistry or to geology or to botany for rules for the conduct of life. We go to these things mainly for the satisfaction which the knowledge of Nature's ways gives us.

So with natural history. For my own part I find the life-histories of the wild creatures about me, their ways of getting on in the world, their joys, their fears, their successes, their failures, their instincts, their intelligence, intensely interesting without any ulterior considerations. I am not looking for ethical or poetic values. I am looking for natural truths. I am less interested in the sermons in stones than I am in the life under the stones. The significance of the metamorphosis of the grub into the butterfly does not escape me, but I am more occupied with the way the caterpillar weaves her cocoon and hangs herself up for the winter than I am in this lesson. I had rather see a worm cast its skin than see a king crowned.[55] I had rather see Phœbe building her mud nest than the preacher writing his sermon. I had rather see the big moth emerge from her cocoon—fresh and untouched as a coin that moment from the die—than the most fashionable "coming out" that society ever knew. The first song sparrow or bluebird or robin in spring, or the first hepatica or arbutus or violet, or the first clover or pond-lily in summer—must we demand some mystic password of them? Must we not love them for their own sake, ere they will seem worthy of our love?

To convert natural facts into metaphysical values, or into moral or poetic values—in short, to make literature out of science—is a high achievement, and is worthy of Emerson at his best, but to claim that this is their sole or main use is to push idealism to the extreme. The poet, the artist, the nature writer not only mixes his colors with his brains, he mixes them with his heart's blood. Hence his pictures attract us without doing violence to nature.

We will not deny Emerson his right to make poetry out of nature; we bless him for the inspiration he has drawn from this source, for his "Wood-notes," his "Humble-Bee," his "Titmouse," his "May-Day," his "Sea-Shore," his "Snow-Storm," and many other poems. But we must "quarrel" with him a little, to use one of his fa[56]vorite words, for seeming to undervalue the facts of natural science, as such, and to belittle the works of the natural historian because he does not give us poetry and lessons in morals instead of botany and geology and ornithology, pure and simple. "Everything," he says, "should be treated poetically—law, politics, housekeeping, money. A judge and a banker must drive their craft poetically, as well as a dancer or a scribe. That is, they must exert that higher vision which causes the object to become fluid and plastic." "If you would write a code, or logarithms, or a cook-book, you cannot spare the poetic impulse." "No one will doubt that battles can be fought poetically who reads Plutarch or Las Casas."

We are interested in the wild life around us because the lives of the wild creatures in a measure parallel our own; because they are the partakers of the same bounty of nature that we are; they are fruit of the same biological tree. We are interested in knowing how they get on in the world. Bird and bee, fish and man, are all made of one stuff, are all akin. The evolutionary impulse that brought man, brought his dog and horse. Did Emerson, indeed, only go to nature as he went to the bank, to make a draft upon it? Was his walk barren that brought him no image, no new idea? Was the day wasted that did not add a new line to his verse? He appears to have gone up and down[57] the land seeking images. He was so firmly persuaded that there is not a passage in the human soul, perhaps not a shade of thought, but has its emblem in nature, that he was ever on the alert to discover these relations of his own mind to the external world. "I see the law of Nature equally exemplified in bar-room and in a saloon of the philosopher. I get instruction and the opportunities of my genius indifferently in all places, companies, and pursuits, so only there be antagonisms."

Emerson thought that science as such bereaved Nature of her charm. To the man of little or no imagination or sensibility to beauty, Nature has no charm anyhow, but if he have these gifts, they will certainly survive scientific knowledge, and be quickened and heightened by it.